1. Introduction

Appelquist, Cohen, and Schmaltz [

1] proposed a novel constraint on strongly coupled field theories, relating the number of infrared (IR) degrees of freedom to those in the ultraviolet (UV). Their work exemplifies a broader effort to understand gauge dynamics beyond the perturbative regime. The commonly accepted perspective is that the fundamental interactions of nature arise from gauge principles, whose corresponding theories—describing electromagnetic, weak, and strong forces—have achieved remarkable empirical success. When the gauge coupling is weak, perturbative techniques provide a powerful computational framework, as demonstrated by Quantum Electrodynamics (QED). However, in the strong-coupling regime—such as the low-energy sector of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD)—perturbation theory breaks down, rendering analytic approaches intractable [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The commonly accepted perspective is that the theories describing nature’s fundamental forces arise as consequences of gauge principles. These gauge theories have proven immensely successful in describing electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions. When the gauge coupling is weak, perturbative techniques offer a powerful computational framework, as exemplified by Quantum Electrodynamics (QED). However, in the strong coupling regime—such as the low-energy sector of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD)—perturbative methods break down, rendering the theory analytically intractable [

2,

3,

4,

5].

To tackle strong coupling, nonperturbative techniques like instanton calculus and lattice gauge theory are employed. Instantons provide semi-classical tunneling solutions that give insight into nonperturbative effects, but their utility is limited since they are often uncontrolled in realistic scenarios [

2]. The lattice approach, by contrast, is numerical and has been successful in many cases, yet it struggles with problems like chiral fermions and real-time dynamics [

3]. Consequently, an alternative conceptual framework is desirable.

One such principle that has garnered much attention is Seiberg duality [

6], a remarkable example of electric–magnetic duality in four-dimensional

supersymmetric gauge theories. Seiberg duality equates the correlation functions of a strongly coupled theory to those of a weakly coupled “dual” theory with a different gauge group and additional matter fields, enabling indirect analysis of nonperturbative dynamics through symmetries and general properties of supersymmetry [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In 1999, Appelquist, Cohen, and Schmaltz (ACS) proposed a new constraint on strongly coupled gauge theories, positing an inequality on the number of effective degrees of freedom, measured via the free energy at different energy scales [

1]. This was part of a broader effort to understand renormalization group (RG) flows and their irreversibility, reminiscent of the well-known Zamolodchikov c-theorem in two-dimensional quantum field theories [

13]. The search for a four-dimensional analog of the c-theorem culminated in the conjecture of the a-theorem by Cardy [

14], which was later on proven by Komargodski and Schwimmer [

15,

16]. While the a-theorem constrains the behavior of the central charge

a along RG flows, the ACS conjecture imposes a related but distinct inequality on the free energy, aiming to capture the monotonic decrease of degrees of freedom from ultraviolet (UV) to infrared (IR) fixed points.

The ACS conjecture states that for quantum field theories where the free energy

is well-defined and finite after appropriate regularization, the effective number of degrees of freedom measured by the normalized free energy satisfies

This inequality suggests that the effective degrees of freedom decrease under RG flow, consistent with the physical intuition that high-energy theories have more active degrees of freedom than their low-energy counterparts [

1].

The ACS conjecture has yet to be proven in full generality, and no counterexamples are known. However, it has been tested in numerous nontrivial examples including perturbative fixed points such as the Banks–Zaks fixed point [

17], and supersymmetric gauge theories [

18,

19]. In reference [

1], the consistency of the ACS conjecture with Seiberg duality predictions for the conformal window of SQCD was demonstrated.

To examine the ACS conjecture concretely, we focus on the Banks–Zaks fixed point for

SQCD with gauge groups

and

, extending the analysis similar to that in [

1,

18]. This approach leverages the small parameter in the gauge beta function that allows perturbative control near the fixed point [

17].

Beyond direct computations of the free energy, another powerful tool in supersymmetric theories is the study of superconformal

R-charges and the central charge

a via a-maximization [

20,

21]. Kutasov, Parnachev, and Sahakyan provided a procedure to correct the central charge in cases where unitarity bounds are violated due to free fields emerging in the IR, by iteratively subtracting contributions of decoupled fields [

22]. This method can be used to estimate effective degrees of freedom in the IR, even in complicated theories with superpotential deformations and multiple gauge groups [

23,

24,

25].

We analyze non-chiral

gauge theories with one or two adjoint chiral superfields, classified under the ADE scheme [

26], along with more general chiral theories and semi-simple gauge groups [

27,

28]. The inclusion of superpotentials affects the conformal data and can drive the theory to novel fixed points, whose central charges must be carefully computed to test the ACS conjecture [

8,

12]. Our analysis consistently finds no violation of the ACS inequality, reinforcing its potential universality.

Historically, these investigations connect to a broader context of conformal field theory (CFT) and RG flow studies. The positivity constraints on anomalies and exact nonperturbative central functions in supersymmetric theories have been elucidated in [

29,

30]. The constraints on RG flows and conformal dimensions have also been explored via the conformal bootstrap program [

31,

32], which complements the study of strong coupling dynamics. The role of the superconformal index and chiral algebras in constraining 4D CFT data further ties these diverse approaches together [

33,

34,

35].

In addition to the theoretical interest, understanding these constraints has practical consequences for phenomenology and string theory dualities, as many gauge theories of interest arise as low-energy limits of string compactifications or are related via the AdS/CFT correspondence [

25]. The rich structure of baryonic charges and dualities was first studied in detail by Witten and others [

36,

37].

In summary, the landscape of strongly coupled supersymmetric gauge theories is constrained by a variety of inequalities and dualities. The ACS conjecture represents a compelling, yet unproven, principle consistent with these constraints and with the behavior of known examples. Our work, through detailed checks at perturbative fixed points and with a-maximization methods, supports the conjecture’s validity and encourages further efforts to establish a rigorous proof or to find novel counterexamples.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In

Section 2, we discuss the case of superconformal QCD with an interacting IR fixed point.

Section 3 presents the a-maximization approach, while

Section 4 summarizes the conclusions of our work. Finally,

Appendix A reproduces results previously obtained in the original paper [

1].

2. SQCD with an Interacting IR Fixed Point

Following [

1], the appendix contains three examples in which the theory is both UV-free and admits a free magnetic dual. The ACS inequality ceases to hold in these cases precisely when the IR dual is no longer free and our underlying assumption fails. In order to test the inequality also in the interacting regime, we use the perturbative expansion for the free energy of high-temperature gauge theory [

3,

4,

5]:

where

(with

the structure constants of the group

G) is the quadratic Casimir of the adjoint representation, and

with

the generators of the gauge group, is the trace normalization factor. Lastly,

denotes the number of gauge bosons.

The free energy in the interacting IR regime can be determined using Seiberg duality and adding the contribution from the Yukawa sector. While the UV theory remains UV-free, the IR dual now flows to non-zero values of the couplings (fixed points). The expression for the fixed-point values of the couplings is given in [

18]:

where the couplings

are the coefficients of the cubic part of the superpotential:

and the RG equation for the Yukawa couplings at the fixed point [

18] is

with

In general, Equations (

3) and (

5) are not sufficient to determine the fixed point, since higher-order contributions in

g also appear. To make the perturbative expansion reliable, we take

N to be very large, which suppresses higher-order terms [

17,

36]. Such fixed points are known as Banks–Zaks fixed points. Substituting the parameters into the above formulas, we obtain the following fixed point values for the

group with

flavors:

while, for the

group with

flavors, we find

where

Thus, for the perturbative expansion to be valid, we must take

. With these results in hand, we are now ready to test the ACS inequality.

2.1. Group with Flavors

In the case we are interested expression (

2) becomes

and the Seiberg dual is found by making the transformation

and adding

mesons:

On the Banks–Zaks fixed point (

8), the last expressions become

Clearly, we can see that

.

2.2. Group with Flavors

The expressions for the free energy in the

is

while the

free energy expression is found by applying the Seiberg prescription

and adding

mesons, we find

Inserting the Banks–Zaks fixed point (

9), we find again that

.

3. The a-Maximization Approach

The properties of the conformal superalgebra have been studied extensively (see, for example, [

38,

39]). In four-dimensional spacetime, the unitary irreducible representations of an operator

can be classified using a real number

, the exact scaling dimension, defined for a spinless field by

and two additional indices

, which denote the irreducible representation of the Lorentz group

.

Of particular interest are conformal primary operators, which transform under conformal transformations as

where

is the Jacobian of the coordinate transformation.

Unitarity imposes bounds on representations: all states in a representation must have positive norm. States that violate unitarity correspond to representations with null states, which can be removed, leaving a shortened representation. Using the

Lorentz representation, the unitarity bound for a primary operator

reads

A scalar operator

saturates the second bound if and only if it satisfies the Klein–Gordon equation:

Similarly, a spin-

operator

saturates the bound if and only if it satisfies the Dirac equation:

and an antisymmetric tensor

saturates the bound if and only if it satisfies Maxwell’s equation:

Whether or not the theory is conformal, the unitarity bound can also be expressed in terms of the

charge of

[

20]:

The saturation of the last inequality occurs for primary chiral operators (as defined in [

21]),

where

is the anomalous dimension of the field.

For spin-zero operators, the unitarity bound

together with the last inequality implies

with equality if and only if

is a free decoupled field satisfying

.

As explained in [

20], this unitarity condition does not constrain the R-charge assignment of the fields inside the Lagrangian. Indeed, it may happen that the R-charge of a field appears to violate the bound. The resolution is that any gauge-invariant chiral operator

X that apparently violates the unitarity bound is actually a free decoupled field with an accidental

symmetry that restores its superconformal R-charge to

, leaving the R-charges of other operators unchanged. To determine the “true” R-charge, one writes the most general R-symmetry as

where

are all non-R flavor

generators consistent with the global symmetry group

. The central charge, expressed in terms of ’t Hooft anomalies, is

The maximization of

with respect to

yields

or equivalently,

The local maximum is ensured if the matrix of second derivatives

is negative-definite. As shown in [

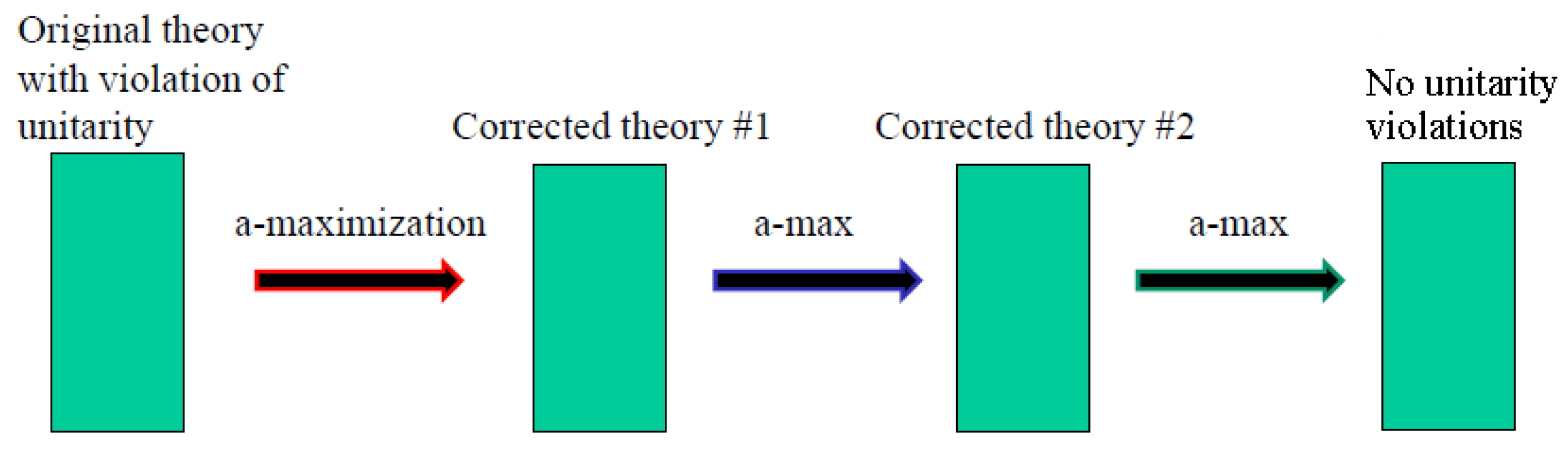

20], these conditions hold in any unitary superconformal field theory. In the following sections, we apply this procedure to SQCD with one or two adjoint fields. Each time the unitarity bound is violated, the central charge is corrected, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Following [

20], the corrected central charge is

where

M is the set of gauge-invariant chiral superfields with

. Identifying

M allows one to estimate the decoupled fields in the IR and provide a lower bound for

. While interactions may increase the true

, these estimates remain nontrivial, as shown in the following sections.

The use of a-maximization in this section serves as a practical tool to identify operators that violate the unitarity bound and therefore decouple as free fields in the infrared. We emphasize that the corresponding estimate for

includes only the contribution of these decoupled fields. Since the interacting conformal sector is not computed explicitly, our results represent

lower bounds on

, not exact values. Unlike the perturbative analysis in

Section 2, the theories examined here do not admit full quantitative control, but the method still provides nontrivial consistency checks. In particular, any potential violation of the ACS inequality would be visible even at the level of these lower bounds. We now make this logical structure explicit to clarify the interpretation of our findings.

We begin our analysis with theories with

gauge group and one adjoint

X, and then extend to two adjoints

X and

Y, the maximal number compatible with asymptotic freedom [

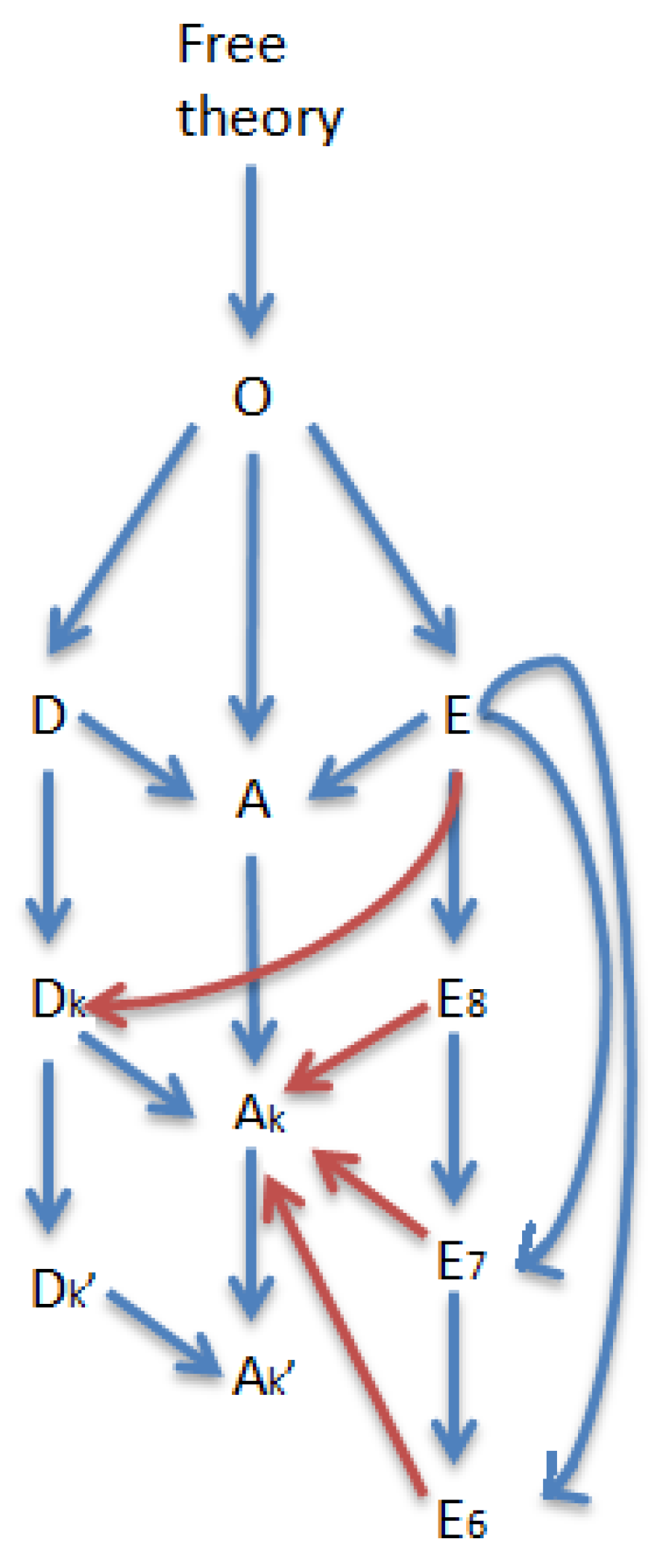

6]. The possible RG fixed points and corresponding superpotential deformations can be classified as follows:

These fixed points correspond to the

classification of Arnold’s singularities. Starting from the

type with

, relevant deformations of the form

satisfy

, independent of

and

, and are relevant only if

. The resulting RG flows and superpotential structures are summarized in

Figure 2.

3.1. SQCD with One Adjoint

In adjoint SQCD, three types of gauge-invariant chiral superfields are central to the analysis.

Baryons:

Here, color indices are contracted using an

tensor, and

. Anti-baryons

are obtained by replacing

. Denoting

, we have

and

Mesons:

with

R-charge

Adjoint traces:

To determine the central charge, we introduce a trial central charge

, assuming the first

m baryons,

n mesons, and

p traces are free:

We want to determine which chiral superfields have dimension

. For simplicity, we focus on

and

, though the method generalizes. The iterative procedure works as follows:

Start with and find the maximizing y.

Check which operators violate the unitarity bound.

Update the trial central charge accordingly (e.g., , , or ).

Repeat until no more operators decouple.

Using

Mathematica, we find

and

Case : After the first iteration, only becomes free (). Maximizing gives , and all operators now satisfy .

Cases : No operator violates the unitarity bound; all remain confined.

The results for the UV and IR degrees of freedom are

confirming that the ACS conjecture is satisfied.

The Limit

For large

with

, assuming

remains finite, the trial central charge becomes

Operators violating unitarity are treated by replacing sums over

j with integrals using

. Only mesons contribute:

Hence,

with maximum at

The number of decoupled fields

p satisfies

Finally,

confirming ACS:

3.2. SQCD with Two Adjoints

The cases studied in the previous sections can be generalized by considering a larger set of adjoint fields. Unfortunately, only a small subset of these theories is asymptotically free, as is the maximal number of adjoints compatible with asymptotic freedom. We begin by describing the chiral ring of operators and then analyze SQCD with two adjoints X and Y for and .

3.2.1. Chiral Ring of Operators

There are three types of operators, generalizing the previous case.

- a.

- b.

- c.

Baryons:

where

,

, and the dressed quarks

are fully contracted with an epsilon tensor.

The anomaly-free trial R-symmetry is

To avoid cumbersome general expressions, we explicitly write only the case of two adjoint fields. Denote

such that

and

, and define

, where

I denotes any set of

elements. Then,

3.2.2. The RG Fixed Points ()

The trial central charge is

The R-charges maximizing

are approximately

All chiral operators in the IR respect unitarity, so no further corrections are needed. Since no fields decouple in the IR, the ACS check is straightforward, similar to the previous analysis.

3.2.3. The RG Fixed Points ()

We assign the

R-charges as

The trial central charge is

The R-charges at the maximum of

are approximately

3.2.4. The RG Fixed Points ()

The

R-charges are assigned as

The trial central charge reads

The R-charges at the maximum of

are approximately

Only in the

case is there a violation of unitarity. The first operators to decouple are the meson

and

. Maximizing

gives

and maximizing

yields

The next operators to decouple would be

or

, but both have

R-charge above

, so no further corrections to the central charge are needed. The UV and IR degrees of freedom are

so the ACS condition is still satisfied.

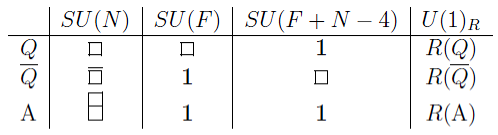

3.3. Analysis of Chiral Theories

3.3.1. Deconfinement and Mixed Phase

Up to this point, our checks involved gauge theories with one or two adjoints and various superpotential deformations, all of which are vector-like. However, some of the most interesting SUSY gauge theories are chiral, as these can exhibit dynamical supersymmetry breaking. The simplest models of supersymmetry breaking typically involve an antisymmetric tensor and some number of flavors. The dynamics of these theories is well understood for small , but the low-energy phase of such theories is generally unknown for arbitrary .

We now follow [

23] and test ACS on an

gauge theory with a two-index antisymmetric tensor

A,

fundamentals

Q,

antifundamentals

, and no tree-level superpotential. The matter content is summarized below:

The

R-charges required for vanishing of the NSVZ

-function are

Defining

and

, the trial central charge is

The chiral ring consists of two types of operators:

Mesons: and .

Baryons: for k and N both even or odd with , and .

We test the cases

and

. The

R-charges that maximize the central charge are

Note that

even in a chiral theory, due to the absence of a superpotential; gauge interactions alone cannot distinguish between the two fields. This equality may change when corrections to the central charge are introduced. The initial unitarity violation occurs for

, where the meson

becomes free. The first correction to the central charge is

with

. Maximizing

gives

and since

, no further operators become free.

The UV-free energy is

and for

the IR-free energy is

, compared to

. ACS is thus vindicated.

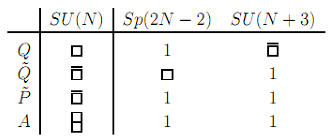

3.3.2. Self-Dual Chiral Theory

Following [

27], consider the theory with matter content:

and superpotential

which is the most general renormalizable form compatible with the symmetries. We denote

N as the gauge group rank.

The chiral ring contains:

Mesons: .

Baryons: for .

The

R-charges of

A and

are related to

and

by the superpotential and ABJ anomaly cancellation:

Maximizing with respect to

and

yields

and an explicit

as a function of

N:

For

no invariants become free. For

, the meson

becomes free. Its contribution to the central charge is

and the second iteration gives

The IR-free energy is , which is less than , so ACS is satisfied.

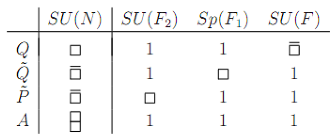

3.3.3. Chiral Theory with Three Types of Flavors

Following [

28], the matter content is

with superpotential . The chiral ring includes

Mesons: .

Baryons: ; for odd N, ;

for even N, with .

The

R-charges satisfy

and

. The central charge is

We test ACS for

. After eliminating

and

and maximizing

a, the

R-charges are

The first operator to become free is

, and after correcting the central charge, the

R-charges become

No further operators violate unitarity. The free energies are

and ACS is satisfied in all cases:

4. Conclusions

Throughout this paper, we have conducted eleven distinct tests of the ACS conjecture, each of which consistently supports its validity. In every scenario considered, the conjecture has withstood scrutiny, and our findings collectively point in a single direction: the ACS conjecture remains robust across a broad range of theoretical contexts. Central to our analysis were two powerful tools. Seiberg duality allowed us to reinterpret strongly coupled dynamics through weakly coupled duals, providing access to the IR structure in regimes that are otherwise analytically intractable. Additionally, a-maximization enabled the extraction of exact conformal dimensions in the infrared, offering precision unattainable through perturbative methods alone. Together, these techniques have allowed us to explore both infrared-free and strongly coupled settings, significantly broadening the range of evidence in support of the conjecture.

Our results contribute to a growing body of nonperturbative checks that reinforce the conjecture’s plausibility. Within the broader context of supersymmetric gauge theories and the study of conformal fixed points [

35,

40], the ACS conjecture plays a key role in constraining the dynamics of the IR and guiding expectations for dualities and operator dimensions. As such, our work not only strengthens the case for the conjecture itself but also informs the broader effort to classify and understand the space of consistent quantum field theories [

31,

32]. While a complete proof of the ACS conjecture remains an open challenge, the convergence of evidence from diverse approaches suggests that a deeper theoretical understanding may be within reach. Future progress might come from uncovering an underlying principle or symmetry that mandates the conjecture’s validity, or from developing new analytic or geometric tools that go beyond current methods [

33,

34]. We hope that our results will motivate further efforts—both computational and conceptual—toward a general and rigorous proof, and that they will serve as a foundation for continued exploration in this rich and evolving field.