Abstract

This article reviews recent progress in computational quantum gravity caused by the framework that efficiently computes Feynman’s rules. The framework is implemented in the FeynGrav package, which extends the functionality of the widely used FeynCalc package. FeynGrav provides all the tools to study quantum gravitational effects within the standard model. We review the framework, provide the theoretical background for the efficient computation of Feynman rules, and present the proof of its completeness. We review the derivation of Feynman rules for general relativity, Horndeski gravity, Dirac fermions, Proca field, electromagnetic field, and Yang–Mills model. We conclude with a discussion of the current state of the FeynGrav package and discuss its further development.

1. Introduction

Perturbative quantum gravity is one of several approaches to quantum gravity. It exists in the effective field theory paradigm, and describes gravitational phenomena at energies below the Planck scale [1,2,3]. To a certain extent, the theory associates gravity with small metric perturbations propagating about the flat spacetime. The Planck scale arises naturally as the characteristic scale of small perturbations. Consequently, the theory can perturbatively treat perturbations with small amplitudes. However, the structure of the theory is more sophisticated and extends beyond this simple setup, as we discuss below.

Perturbation theory operates with propagating degrees of freedom, polarisation operators, and interaction operators describing the interaction between different degrees of freedom. On the practical ground, defining a theory means explicitly providing these components. The graviton propagator and the polarisation operators were derived and studied in classical papers [4,5,6]. The derivation of the interaction rules was the most challenging part of the theory. Because of the effective nature of the theory, it generates an infinite set of interaction operators suppressed by different powers of the same gravitational coupling. For a given level of the perturbation theory, only a finite number of operators contribute to a given matrix element. However, the number of operators grows with each perturbation order. Consequently, calculations become incredibly challenging without an algorithm describing how to obtain the interaction rules at any given order of perturbation theory.

The interaction rules for the first two orders of perturbation theory are published in the literature [7,8,9,10]. These rules were sufficient for one-loop calculations and allowed for significant advancement in perturbative quantum gravity [2,7,8,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Nonetheless, the general algorithm producing the interaction rules at a given order remained unknown. Several research directions were focused on creating such an algorithm. The most well-known ones proposed to use Ward–Takahashi identities [7,8,9] and to bootstrap gravity [19,20,21,22,23]. However, to our knowledge, they never resulted in a practical tool. An additional problem was the complexity of the interaction rules. The paper [9] derived interaction rules for three and four graviton vertices (see also [10], as the mentioned paper contained a misprint). In that particular parameterisation, the three graviton vertex contains 171 terms, while the four graviton vertex contains 2850. While it is exceptionally challenging to manually operate with interaction terms having hundreds and thousands of terms, the contemporary computational packages can (relatively) easily manipulate such expressions.

The recent publications [24,25] created the desirable algorithm. It was implemented in a computational package “FeynGrav”, created at the base of the widely used “FeynCalc” [26,27,28]. This article reviews the constructed theoretical framework, touching upon its application and perspective for further development. For the discussion of the theoretical framework, we focus on the original papers [24,25]. We briefly discuss how FeynGrav can significantly simplify the derivation of the well-known results [2,13,29,30,31] and is used to obtain new results [32,33,34,35]. We conclude with a discussion of the future development of the package.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 discusses the theoretical background behind the perturbative quantum gravity. Namely, we discuss the role of the perturbative quantum gravity together with the limits of its applicability. We discuss the theory in the context of renormalisation and argue, supporting the growing consensus, that its effective nature leaves no room for any “renormalisation issues”. Section 3 discusses the practical tools to develop the theoretical and computational framework. We discuss how to factorise an action describing gravity or a model coupled to gravity in a way most suitable for optimal computations. We separate some fundamental structures defining perturbative expansions and derive recursive relations that significantly improve their computation. Section 4 devoted to the derivation of the Feynman rules for general relativity, scalar field, Horndeski theory, Dirac fermions, Proca field, electromagnetic field, and Yang–Mills model. Section 5 discusses the FeynGrav package, its structure, and rules implemented in the existing version. We present a few explicit examples of perturbative calculations made with FeynGrav. Section 6 summarises the material presented in this paper and highlights perspective further development.

2. Perturbative Quantum Gravity

We divide the discussion of perturbative quantum gravity into two parts. The first part explores the theory’s mathematical and technical aspects, while the second focuses on its physical content. We start with the technical aspects, as they help to explain the premises behind its physical interpretation.

Perturbative quantum gravity is a quantum theory of small perturbation of metric existing about the flat spacetime with the Minkowski metric . To preserve the canonical mass dimension of the field variable, one must introduce the gravitational coupling with mass dimension . One defines the spacetime metric as a combination of the background metric and perturbations:

The gravitational coupling is associated with the Newton constant :

It is important to highlight that the perturbative expansion (1) is finite in , and should not be interpreted as a truncation of an infinite series. Despite (1) being finite, it spawns an infinite series in for the inverse metric:

Consequently, all quantities involving the inverse metric are infinite series in .

Let us look at the two most important examples. The first example is the Christoffel symbol. If the symbol has all lower indices, then it is a finite expression linear in :

On the contrary, the standard Christoffel symbol with a single upper index is an infinite series, since it involves the inverse metric:

The second example is the volume factor . The metric determinant itself is a finite expression in (see [17]), but the volume factor is an infinite series because of the square root:

The action of any gravity model is an infinite series in , since it includes the volume factor for the coordinate invariance. Moreover, a typical action of a gravity model includes invariants constructed from the Riemann tensor. Christoffel symbols constitute the Riemann tensor, introducing additional infinite series to the theory. From the technical point of view, this is the reason why the action of any gravity model contains an infinite number of interaction operators.

The path integral formalism provides a way to construct a perturbative quantum theory. The generating functional provides a way to calculate matrix elements:

Here, is the microscopic action of the model. Within the perturbative approach, one uses (1) in the path integral, expanding it in an infinite series. Metric (1) performs a simple shift of integration variables by a constant value:

The first term of this expansion is irrelevant. The multiplier does not depend on the integration variables and factorises out of the path integral. In turn, while calculating a matrix element, the multiplier will be cancelled entirely because of the normalisation.

It is safe to assume that the second term shall also vanish. The term disappears if the flat spacetime makes the microscopic action stationary, which occurs when the classical field equations derived from the microscopic action have flat spacetime as a solution. Consequently, the discussed approach only applies to some gravity models with further modifications. One can always extend it to the case of an arbitrary background spacetime [36,37]. Further, we will discuss the physical content of the theory and argue that it may not be necessary. Let us postpone the discussion, assume that the term vanishes, and proceed with the technical discussion.

The other terms of the expansion do not vanish, but describe the propagation of perturbations and their interactions. It is helpful to present in the following form, making its structure explicit. The action naturally contains factor, similar to the Einstein–Hilbert action. Therefore, the generating functional takes the following form:

Here, is the differential operator defining the structure of the graviton propagator well-established in the literature [4,38]. Operator is the differential operator defining the structure of interaction between three perturbations. The term includes all other interaction terms, each suppressed by a different power of the gravitational coupling.

The standard prescription provides a way to calculate a given matrix element. One shall introduce a formal external current linearly coupled to the metric perturbation:

The path integral reduces to the Gaussian integral, which can be solved explicitly:

Finally, each matrix element links to a variational derivative of the functional:

The following comments are due. First and foremost, gravity is a gauge theory, so operator does not exist. In analogy with other gauge theories, one uses the Faddeev–Popov ghosts [39,40] or the BRST technique [41,42,43,44] to obtain the propagator. We discuss this issue in detail in another section, since it is irrelevant to the principal discussion. Secondly, the discussed scheme is the standard scheme used within the conventional quantum field theory. In that sense, perturbative quantum gravity is the most general attempt to study quantum gravitational effects while remaining within the standard quantum field theory without any modifications. Lastly, the discussed calculations pose no principal difficulty but a severe computational challenge. The issue is not specific to quantum gravity itself. Even within renormalisable quantum field theories, for instance, within quantum chromodynamics, with each order of perturbation theory, calculations become increasingly complicated and involve more and more contributions [45]. In that sense, perturbative quantum gravity is not an exception to this rule, but rather presents a limiting case with the faster-growing complexity.

Let us turn to a discussion of the physical content of the theory. Three physical premises behind the perturbative approach within the quantum field theory are crucial for the perturbative quantum gravity. Firstly, the perturbation theory only requires propagators, interaction operators, and polarisation operators to generate perturbative expansions. Secondly, propagating and external states are not necessarily free states of a theory. Thirdly, the Poincare group is necessary for the perturbative theory within the conventional quantum field theory. Below, we elaborate on these points.

Firstly, the core of a perturbative theory is propagating degrees of freedom, their interactions, and polarisation operators. Indeed, when given these objects, one can use the standard Feynman graphs technique to generate any perturbative expansion up to any desired order. From the physical point of view, these objects provide all the information about the content of the theory. The polarisation operators describe the states of quantum fields in the initial and final states. Propagators describe how perturbations propagate in the spacetime, while the interaction operators describe their interactions. The perturbative expansion approximates a matrix element as a series of consecutive interactions. These series allow one to define the S matrix, the evolution operator of the theory, describing it in the most general way possible. Therefore, one requires no other objects to create and implement the perturbation theory.

Secondly, one shall distinguish propagating, external and free states. Propagating states are those states described by propagators of the theory. External states are those states described by polarisation operators. Free states are those states which can be separated and captured or measured in a (conceivable) physical experiment. The following considerations show the need to make such a distinguishment.

It is well-established that propagating states differ from those present in initial and final states. The Faddeev–Popov ghosts provide the best example [40]. These ghosts are non-physical, since they enter a theory due to the mathematical redefinition of the path integral integration volume. Consequently, these ghosts do not enter initial or final states, and cannot be separated or detected in any physical experiment. Nevertheless, they must be presented in a perturbation theory to ensure the gauge invariance and unitarity of the theory. This example alone shows the need to distinguish between states that propagate and states that can exist in the initial and final states.

The neutrino mixing mechanism [46,47] explicitly shows the difference between propagating states and states that can be registered. The mechanism explicitly states that there are three neutrino states , , and , which are eigenstates of the mass operator. At the same time, exist three neutrino states , , and , which are eigenstates of the interaction operators. These states are not the same but are linearly related via the Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata matrix. Neutrino propagators correspond to the eigenstates of the mass operator. However, these states cannot be registered by any physical apparatus, since the eigenstates of the interaction operator are coupled to the matter states. Therefore, this model provides an explicit example of a difference between propagating states and states that can be registered.

Quantum chromodynamics provides the most vivid justification for the need for such a distinction [48,49,50]. Within the theory, quarks experience mixing [51,52], so the same logic is applicable. Quark propagators correspond to the mass operator eigenstates, which differ from the interaction operator eigenstates. The Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix linearly connects these eigenstates. Further, the confinement makes it impossible to observe quark states directly. The spectrum of observed states is colourless, and does not match the spectrum of propagating states. One uses the distribution functions technique to relate calculations within quantum chromodynamics with observational quantities [53,54,55]. A distribution function describes an external probe’s probability of interacting with a quark or a gluon composing a non-perturbative state, such as atomic nuclei. In other words, one operates with matrix elements having interaction operator eigenstates in the initial or finite states. In this way, quantum chromodynamics not only points to the necessity to distinguish between these states, but actively requires such a distinguishment for all computational purposes.

Lastly, the Poincare group is essential for quantum field theory. The group admits two Casimir operators. A Casimir operator is an operator that commutates with all other operators of the group algebra. Consequently, the eigenstates of a Casimir operator remain invariant under the Poincare group transformations. Two Casimir operators of the Poincare group define the notions of mass and spin, which is the basis for constructing and classifying all quantum fields [56,57,58]. Therefore, without the Poincare group, one shall construct a new field theory significantly different from the standard one. This reasoning does not imply that such theories do not exist, shall not be constructed, or are irrelevant to quantum gravity. On the contrary, such theories are widely developed, with the conformal field theory being (perhaps) the most well-known [59,60,61,62,63]. However, the discussion of their possible implementations for quantum gravity lies far beyond the scope of this paper.

The crucial role of the Poincare group found an implementation within the rapidly developing scattering amplitude techniques [64,65,66,67]. In contrast with the conventional quantum field theory, the scattering amplitude technique does not appeal to the notion of a quantum field. One classifies the initial and final states of the theory as eigenstates of the Poincare group Casimir operators without any references to quantum fields. Transformation features of a matrix element with respect to the Lorentz transformation provide a way to fix the matrix element’s general structure uniquely. The optical theorem shows that a given matrix element has multiple contributions. The consecutive application of the theorem recovers the perturbative expansion as the unavoidable consequence of the unitarity. In this way, the scattering amplitude description allows one to recover the perturbative approach to quantum field theory without directly referencing quantum fields but using only the Poincare group.

These premises point to the following features in understanding perturbative quantum gravity. Firstly, choosing a flat background is necessary to construct a perturbative quantum theory of gravity within the standard quantum field theory framework. Secondly, the theory applies to a scattering of separated gravitational perturbations and matter states, but its applicability may extend beyond this setup.

The existence of the flat background is crucial due to the role of the Poincare group. Let us highlight one more time that it is possible to work within a theory with a different background, both from fundamental and technical points of view. However, such theories will bring us outside the standard quantum field theory formalism. The flat background allows one to use the Poincare group and to define eigenstates of mass and spin operators. In turn, one can define the scattering problem in the standard way described in many textbooks [36,37]. One associates initial and final states with past and future spatial infinity while assuming that interaction occurs in the flat spatial region between these states.

The formalism of perturbative quantum gravity extends beyond the standard scattering problem. Firstly, propagating graviton states may not be associated with the states registered by physical apparatus. Gravitons are propagating states because they are associated with eigenstates of mass and chirality operators. As was pointed out above, this does not imply that these exact states are registered by physical apparatus. The graviton propagator receives highly non-trivial quantum corrections altering its structure [68,69], further indicating that propagating graviton states shall not be associated with states registered by physical apparatus. Finally, there is an ongoing discussion concerning the mere possibility of detecting graviton states directly [70]. Although the main point of this article is related to the subject of our discussion, it will bring us far away from our main aim, so we will not discuss this claim further. Still, even without a discussion about graviton’s detectability, there are enough reasons to believe that graviton states shall be viewed only as propagating states.

These arguments allow one to use perturbative quantum gravity beyond the narrow scope of the scattering problem. There are many branches of research where such an extension of perturbative quantum gravity is assumed implicitly. Perhaps the most recognised one is the calculation of the effective action. Although the detailed discussion of effective action in quantum gravity lies far beyond the scope of this paper (and was done in many publications, for instance [71]), we will touch upon its two most important features.

The effective action technique provides a tool to calculate the classical value (the expectation value) of a quantum field. In other words, one expects to recover the classical dynamics of a system driven by its quantum behaviour. From the technical point of view, to calculate the (n-loop) effective action, one sums (n-loop) one-particle irreducible diagrams. It is well-recognised that even one-loop effective action for a gauge theory (including gravity) is gauge-dependent. In response to this finding, the unique effective action technique was developed [72,73]. It treats the gauge-fixing parameter of a theory as a generalised coordinate and constructs a description of internal field space with curved geometry. In turn, it is possible to define a generalisation of the variational derivative similar to the standard covariant derivative. The unique effective action is defined in terms of such derivatives, which makes it gauge-independent. At the same time, such generalisation of the variational derivative introduces new terms to the effective action. These terms cannot be obtained from one-particle irreducible diagrams, which seems to contradict the original setup. One shall only consider the on-shell effective action to resolve this apparent contradiction. The situation is similar to the calculation of scattering cross sections. Although it is possible to calculate an off-shell scattering cross section, physical apparatus can produce and register only on-shell states. Similarly, the classical value of a quantum field can only be associated with an on-shell object. In this way, the unique effective action removes the gauge dependence from calculations while the fixation of the effective action on the mass shell recovers the classical dynamic of quantum fields.

Lastly, we shall comment on the renormalisation of perturbative quantum gravity. The term “renormalisation” is commonly used in the literature, although it may not be the most suitable for this discussion. For the sake of consistency, we will continue to use this term. However, it is worth noting that the discussion below goes far beyond renormalisation as it is understood in conventional renormalisable models such as quantum electrodynamics, Yang–Mills theory, and the standard model.

The growing consensus is that perturbative quantum gravity does not experience any problems with renormalisation. This point of view does not imply that the theory is well-renormalisable. On the contrary, it is believed that extending the perturbative quantum gravity to a conventionally renormalisable theory is impossible. Consequently, all “problems” of the theory shall be viewed as features, while the complete theory of quantum gravity development shall be performed separately.

The main feature of the perturbative quantum gravity defining its renormalisation behaviour is that it generates a new set of higher dimensional operators at each loop order. This feature was first observed in the classic paper [74], where the one-loop divergences of perturbative quantum gravity were studied. At the one-loop level, the theory generates divergences proportional to operators , , and . The divergence of the Riemann tensor squared term is irrelevant, since the term can always be brought to the Gauss–Bonnet term, which is the complete derivative in .

These divergences vanish for pure general relativity without matter for on-shell amplitudes. On shall states satisfy the vacuum Einstein equations , so all the divergent contributions are cancelled. This feature is accidental, since it requires the theory to exist in , has no matter degrees of freedom, and works only for on-shell amplitudes. Many other results later confirmed this general theory feature (see, for instance, [12,29,75,76]).

The fact that the theory generates new operators at each level of perturbation theory can be negated from the technical point of view, but the theory loses its predictability. Indeed, let us assume that we calculated a gravitational scattering cross section at the tree level and compared it with empirical data. At the tree level, the theory has a single coupling, the gravitational coupling, and we shall recover its value from the experiment. When we go at the one-loop level, the value of the gravitational coupling is not affected by quantum effects [68,69]. However, the theory develops divergences proportional to and operators. From the technical point of view, these divergences can be subtracted and replaced by two new couplings. In turn, the values of these new couplings shall once again be recovered from the experiment. Consequently, by increasing the level of perturbation theory (the number of loop corrections), we do not increase the precision of calculations. On the contrary, we require more data to match experimental results with each iteration.

These arguments show that perturbative quantum gravity cannot be treated like the conventionally renormalisable theory. From the physical point of view, the root of the problem lies in the fact that the theory is effective. Since it admits a separated energy scale, the Planck scale, it marks the natural limit of its applicability. In full agreement with the standard effective field theory logic [1,2,77], the theory shall include the term terms suppressed by the gravitational coupling the closer to the Planck energy it approaches.

We shall summarise this section to conclude the discussion of the perturbative quantum gravity. Perturbative quantum gravity is a perturbatively constructed quantum field theory with the following distinctive features:

- Gravitons are propagating massless degrees of freedom with chirality .

- There are no reasons to believe that gravitons shall be associated with degrees of freedom measured by physical apparatus.

- The theory is equivalent to a quantum theory of small metric perturbations.

- The theory has infinite interaction operators, but the same gravitational coupling parametrises them.

- The theory is effective. It develops new operators at each new order of perturbation theory.

- The theory does not experience problems with renormalisation, since it shall not be renormalised due to its effective nature.

Although the discussion can be extended further, especially considering the ongoing study of its quantum features, this section describes the core of the theory relevant to the main aim of the article. With the given background, we can meaningfully address the problem of generating Feynman rules within perturbative quantum gravity.

3. Computational Tools

This section discusses technical tools that make an efficient calculation of the interaction rules for perturbative quantum gravity possible. The main feature of the theory is the factorisation that allows one to separate a quantum gravity action into factors of two types. Factors of the first type contain derivatives and a finite number of terms. The others are free from derivatives, but are infinite series. We discuss this factorisation in the following subsection. Factors of the first type are easy to calculate and require no sophisticated techniques, so we will not discuss them in detail. Factors of the second type present a more significant challenge. Nonetheless, it is possible to establish certain recursive relations, which highly improve the efficiency of their calculations. The second subsection discusses such relations.

We will present results in a series of definitions and theorems. Detailed proofs for many theorems are omitted, as they are not this paper’s primary focus and can be found in other publications.

3.1. Factorisation

We begin with the formal definition of the perturbative metric.

Definition 1.

The perturbative metric is defined as follows:

Here, is the small metric perturbations, is the Minkowski metric used to raise and lower indices, and κ is the gravity coupling related with the Newton’s constant

This formula is not a truncation of an infinite series, but a finite expression with no omitted terms. The metric still introduces infinite series in the theory.

Theorem 1.

Here, is the vierbein, is the binomial coefficients defined via the Γ function, and the following notations are used:

Proof.

The proof of the first expression is trivial. One should use the given expression to calculate and verify its correctness. The papers [17,24,25] provide a more detailed discussion of the proof.

Proof of the second expression is much more complicated. Firstly, one shall use the relation between the determinant and trace of a matrix:

Secondly, one shall factorise one flat spacetime metric and reduce the expression to a single exponent:

Lastly, one expands both exp and ln functions as Taylor series. The resulting expression is an infinite power series, with each term also being a power series. Nonetheless, it is possible to rearrange the terms of this series to obtain the desired expression. The publication [24] provides a detailed explanation of the derivation.

Lastly, the expression for vierbein was first obtained in [17]. One assumes the vierbein admits a power series expansion with unknown coefficients. The values of coefficients are fixed uniquely, so the expansion fits well-known relations for the vierbein. □

Only these objects and their combinations generate all infinite expansions that may enter a quantum gravity action within Riemann geometry. However, these are not all the objects present in the theory. We still have to discuss the Christoffel symbols and the Riemann tensor. The following theorem gives their structure.

Theorem 2.

Proof.

Proof of the first two expressions is trivial, and relies only on the definition of the Christoffel symbols

The last expression is proved as follows. Firstly, one shall use the definition of the spin connection:

The spin connection is antisymmetric for indices a and b. For the perturbative metric, the last term is constituted only by symmetric matrices, so it is symmetric with respect to a and b. Therefore, the last term does not contribute to the spin connection. For the first term, one shall use the explicit expression for the Christoffel symbol and make it antisymmetric. Similarly, paper [24] discusses the derivation in more detail. □

The obtained expressions allow us to describe the structure of the Riemann tensor with the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

Proof.

Expressions for the Ricci tensor and the scalar curvature can be derived directly from the expressions for the Riemann tensor, making their derivation purely technical. The derivation of the first two formulas is technically straightforward, but requires lengthy computations. To obtain the desired result, one shall use a single relation for the inverse metric derivative:

The remaining part of the proof relies on the manipulation of indices. □

These theorems constitute the factorisation theorem crucial for the perturbative quantum gravity.

Theorem 4.

In Riemann geometry, a gravity action evaluated with the perturbative metric can always take a form where all terms that begin infinite series are free from derivatives and expressed via , , and .

In other words, as long as we operate within Riemann geometry, we can always split a gravity action into two different parts. The part that involves derivatives is finite, and can be calculated explicitly. The other part is an infinite series, but it is always expressed in terms of elementary series for the volume factors , the inverse metric , and the vierbein .

3.2. Recursive Relations

The previous section provides a way to factorise a gravity action, but we must still address calculational challenges. Namely, we shall elaborate on the method to describe the structure of perturbative expansions for the inverse metric, volume factor, and vierbein. We address this challenge in this section.

Definition 2.

We define the plain I-tensor of the n-th order as follows:

The tensor has no additional symmetries. We introduce an additional tensor to account for the essential symmetries of the interaction rules.

Definition 3.

We define the -tensor of the n-th order as follows:

Permutations account for all terms that make the -tensor symmetric with respect to permutations of indices within each index pair , and with respect to permutations of any two index pairs .

The tensor of the n-th order has terms. In other words, the number of terms grows faster than the factorial. This feature holds for tensors discussed below. Although this feature presents a computational challenge, it is an essential part of the standard perturbative approach. The final expression for a gravity interaction vertex shall be symmetric with respect to graviton permutations, so it is necessary to operate with tensor structures respecting this symmetry.

The plain I-tensor provides a way to operate with powers of and its traces given by the following theorem. The theorem is trivial, so we omit the proof.

Theorem 5.

The plain I-tensor defines the structure of powers of and its traces.

Using this theorem, one can demonstrate how the plain I-tensor describes the perturbative structure of the inverse metric. The following theorem, which describes this relation, is a direct corollary of previous theorems, so we omit its proof.

Theorem 6.

The inverse metric perturbative expansion in terms of the plain I tensor reads:

This theorem provides an easy way to study the features of the I-tensor, such as the following easily proven contraction feature.

Theorem 7.

The I-tensor admits the following contraction feature:

Proof.

We shall start with the following general relation:

This relation can be expanded:

The desired relation holds as each term in the infinite sums is cancelled. □

We uncover the perturbative structure of the volume factor in a similar way. Initially, we give a non-constructive definition of the plain C-tensor. Further, we demonstrate a specific recursive relation between C-tensors of different orders. This relation allows one to calculate a given order’s plain C-tensor.

Definition 4.

We define the plain C-tensor of n-th order in such a way to describe the perturbative structure of the volume factor:

Similarly to the previous case, the definition does not require specific symmetries among the indices. The next definition of the -tensor introduces a tensor with suitable symmetries.

Definition 5.

We defined the -tensor of the n-th order as follows:

Permutations ensure -tensor is symmetric with respect to index pair and pair permutations.

The definition is not constructive, since it does not show a way to compute the tensor explicitly; instead, it only describes its function. However, obtaining a recursive relation that facilitates an uncomplicated method to construct C-tensors is possible.

Theorem 8.

The following recursive relation holds.

Proof.

Firstly, we introduce an auxiliary metric:

Here, z is an arbitrary positive real number. This metric has no physical or mathematical meaning except to obtain the discussed relation. It matches the original metric when .

Secondly, we compute the following derivative:

We applied Jacobi’s formula for a non-degenerate matrix X:

Let us calculate the same derivative using the perturbative expansion:

Comparing these expressions, we obtain a relationship that does involve :

The left-hand side of this expression can be calculated perturbatively:

After comparing these expressions, we can derive the required recursive relation.

□

Equation (33) defines a plain C-tensor of n-th order recursively using plain C-tensors of lower orders. One would desire to express using alone, but unfortunately, it appears to be impossible. The reason is that formula (33) involves all low orders that must contribute to the plain C-tensor. Since the volume factor is the simple object, we conjecture that no simpler recursive formula exists.

The same logic shall be used to construct more complicated structures generated by the volume factor and the inverse metric. Firstly, we give a non-constructive definition of a tensor. Secondly, we find a recursive relation that defines the required tensor iteratively.

Definition 6.

We define the family of plain -tensors as follows:

These tensors do not have any additional symmetry. The corresponding symmetric tensors are defined as follows.

Definition 7.

Permutations ensure symmetric -tensor with respect to index pair and pair permutation. It is important to note that symmetrisation accounts only for indices contracted with the perturbation indices.

Theorem 9.

The following recursive relation holds for plain -tensors.

Proof.

The proof relies on the possibility of factorising a single metric from the perturbative expression. We can use this fact to define the tensors.

At the same time, we can perform the perturbative expansion of separately.

One can decouple the summation indices by redefining them, resulting in the following formula:

The proof is concluded by making a direct comparison with the definition of the original tensor . □

Finally, we treat vierbein similarly. We define the plain E-tensor and plain -tensor to encapsulate the structure of the following factors.

Theorem 10.

These tensors do not possess any additional symmetry. In practice, we never use the plain E-tensor, so we do not discuss it further. Moreover, the plain E-tensor match the plain I-tensor up to a constant. On the contrary, the plain -tensor is relevant for Dirac fermions, so we define its symmetric generalisation.

Definition 8.

Permutations account for all terms that make the -tensor symmetric with respect to permutations of indices within each index pair , and with respect to permutations of any two index pairs .

The recursive relation for the tensor holds similarly to the tensor. The proof for -tensor is constructed the same way as the proof for -tensor and is omitted.

Theorem 11.

The main result of this section is Theorems 8, 9 and 11. They are essential from the computational point of view, since their implementation significantly improves the code performance. We believe no simpler formula can be found based on the perturbative expansion structure. All the factors discussed above contain , which makes it impossible to construct recursive relations for them without a recursive relation for . Theorem 8 shows that the n-th perturbative order incorporates all lower orders, making it impossible to establish a relation between the n-th and -th orders alone. Therefore, we believe it is impossible to construct truly recursive relations for all other factors.

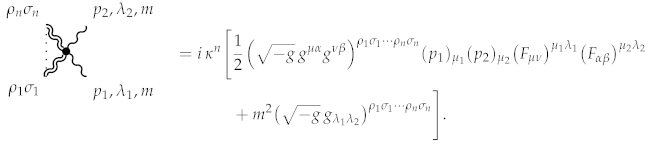

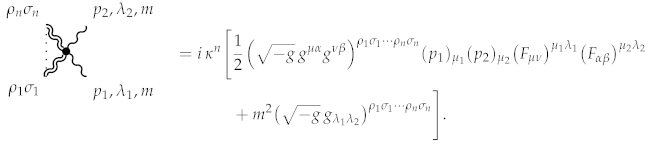

4. Feynman Rules

The computational tools discussed in the previous section provide a comprehensive framework for deriving Feynman’s rules for perturbative quantum gravity. This section covers the derivation of interaction rules for simple scalars, Horndeski gravity, Dirac fermions, massive and massless vector fields, Yang–Mills model, and general relativity. This collection of models is sufficient to account for quantum effects within the standard model.

We handle all interaction rules as follows. We use the factorisation theorem to separate terms that are infinite series from terms that are finite but contain derivatives. The finite part is calculated explicitly, while the infinite part is expanded in the infinite perturbative series. The discussed recursive relations provide a way to evaluate each term in such a perturbative expansion. Therefore, pointing to the structure contributing to a given perturbative order is sufficient.

We will not discuss the derivation of the Feynman rules from the action via the path integral formalism. The procedure is discussed in multiple sources, including classical textbooks [78,79,80,81]. The procedure also uses Fourier transformation to generate rules in the momentum representation. We also do not discuss the Fourier transformation for the same reason.

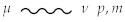

Lastly, we shall introduce new notations for the practical sake. In perturbative expansions considered below, using , , and other previously defined tensors is not optimal. These tensors play a crucial role in the technical side of the calculation, but they do not provide the most practical description.

If the quantity X admits a perturbative expansion in small metric perturbations, then we shall use the following notations:

Here, is the contribution to the n-th order of the expansion. One can define via derivatives:

Let us present the following expressions to illustrate these notations. The components of the inverse metric are noted as follows:

The explicit values of the first few of these components are:

Implementation of these notations for the volume factor produces the following:

4.1. Scalar Field with a Potential

The action for a single free scalar field with mass m with the minimal coupling to gravity reads:

Following the factorisation theorem, the action takes the following form:

The following theorem describes its structure in the Fourier representation.

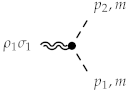

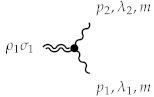

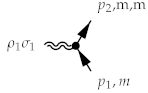

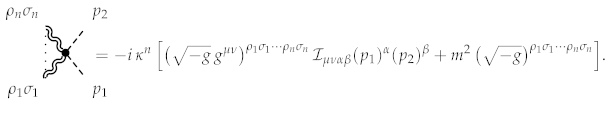

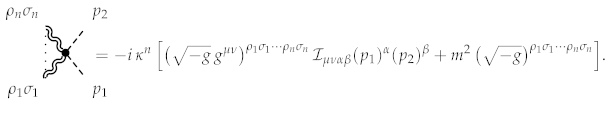

Theorem 12.

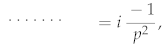

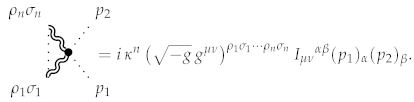

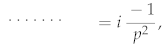

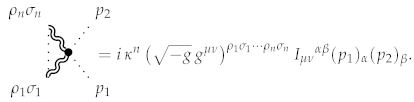

Here, are momenta of gravitons, and are momenta of scalars, and the same definition of tensor is used:

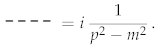

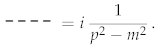

The contribution of order describes the standard scalar propagator:

The other terms define the coupling of scalar field kinetic energy to gravity:

The dotted line on the left side of the diagram notes the presence of graviton lines.

We can derive the equation for the scalar field potential similarly. The potential is a Taylor series in the scalar field . Each term in this expansion represents a scalar field self-interaction coupled with gravity. Thus, deriving the interaction rule for a single power-law potential is sufficient.

We consider a power-law potential with being a whole number and being a coupling with the mass dimension :

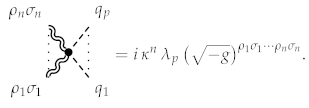

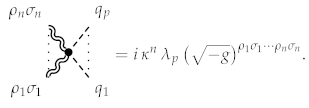

The following theorem describes the action in Fourier representation.

Theorem 13.

This results in the following interaction rule:

This expression fully describes the gravitational coupling of scalar field potentials for any whole .

4.2. Horndeski’s Gravity

The Horndeski theory is the most general scalar–tensor theory of gravity that admits second-order field equations and minimal coupling to matter. It was discovered in [82], and independently rediscovered in [83]. Because of the second-order field equations, the theory is free from the Ostrogradsky instability [84,85,86].

A combination of the following Lagrangians gives the theory:

Here, are functions of the scalar field and its kinetic term , while and note derivatives with respect to the kinetic term. Lagrangians and describe scalar field self-interaction with the minimal coupling to gravity. In turn, and describe healthy non-minimal coupling to gravity. Terms containing and are relevant only when and depend on the scalar field kinetic term. In that case, they cancel out higher derivative contributions to the field equations.

4.2.1. Horndeski Class

The class of Horndeski theory describes a minimal coupling between the scalar field and gravity. This coupling is minimal because it does not involve graviton momenta.

The function shall be smooth enough to admit a Taylor expansion:

Here, is the dimensional coupling with the mass dimension . Without the loss of generality, one can consider a single term of this expansion and consider the following action:

The perturbative expansion is given by the following theorem.

Theorem 14.

Lastly, the Feynman rule corresponding to that action reads

The permutation terms account for all possible permutations of the scalar field momenta. Let us also note that for the case, the interaction reduces the scalar field potential.

4.2.2. Horndeski Class

The interactions of the class of Horndeski theory represent the simplest non-minimal coupling between the scalar field and gravity. The final expression of this interaction contains a single Christoffel symbol, which allows for the explicit inclusion of a single graviton momentum in the corresponding Feynman rule.

We shall first simplify the expression and make the Christoffel symbol explicit.

Theorem 15.

Secondly, should be expanded in a Taylor series:

We can study a single term of the expansion without the loss of generality:

The following theorem gives the perturbative structure of this interaction.

Theorem 16.

It should be noted that the second part of the expression does not contribute at the level, since the Christoffel symbol vanishes on the background.

The corresponding interaction rule is given by the following:

The permutation terms account for all possible permutations of the scalar field and graviton momenta.

4.2.3. Horndeski Class

Interactions of the class describe more sophisticated coupling of the scalar field to gravity. Similarly to the previous case, it involves Christoffel symbols. In contrast with the previous case, Christoffel symbols are present implicitly in the scalar curvature. Moreover, the interaction is described by two related terms, with the second term cancelling higher derivative contributions to the classical equations of motion.

We assume is smooth enough to admit a Taylor expansion. To ensure that the theory admits general relativity in the corresponding limit, one shall assume that the expansion takes the following form:

The first term corresponds to pure general relativity, while the other terms describe the interaction between gravity and the scalar field. We discuss the part corresponding to general relativity in another section, so we do not discuss it here. Without loss of generality, we will use a single term from this expansion:

The following theorems give the structure of this action.

Theorem 17.

The expression consists of two parts. The first part contributes at the level and describes the interaction between a few scalars and a single graviton. The second part does not contribute to , and describes the interaction between two or more gravitons with a few scalars.

The following theorem describes the structure of the term containing .

Theorem 18.

In turn, the Fourier structure of this contribution is given by the following:

Theorem 19.

The first part of the expression contributes to the background at order . The second part contributes to and describes the interaction of a single graviton with a few scalars. The last part contributes to order , and its leading contribution represents the interaction of two gravitons with a few scalars.

The following sophisticated expression gives the resulting expression for the interaction rule.

Let us note that the second and last terms in the square brackets contribute only to vertices with two or more gravitons.

4.2.4. Horndeski Class

The final class of Horndeski interaction also describes a non-minimal coupling between the scalar field and gravity. This interaction involves the most derivatives, which still do not result in the higher-order classical field equations. We study this term similar to the others and make its structure explicit.

The following theorem describes the structure of the non-minimal coupling. It does not involve any integration by parts and relies purely on calculating derivatives.

Theorem 20.

The coupling function shall be smooth enough to admit a power series expansion

Similarly to the previous cases, we can study the following coupling function without the loss of generality:

This results in the following theorem describing the Fourier structure of the first part of the interaction.

Theorem 21.

First, we describe the structure involving scalar field derivatives to proceed with the second part of the interaction.

Theorem 22.

The following theorem gives the perturbative structure of the second part of the interaction.

Theorem 23.

The theorems explain the entire structure of the interaction class. However, we will not explicitly express the corresponding interaction vertex. Because the expression is exceptionally long, it would not be constructive.

4.3. Dirac Spinors

The standard way to describe fermions in curved spacetime uses vierbein and matrices [87]. Firstly, matrices are introduced to construct a representation of the Lorentz algebra. Dirac matrices satisfy the following relations:

They form the following representation of the Lorentz algebra:

The standard vector representation of the Lorentz algebra is given by matrices:

The following relation connects these representations:

One can define Dirac spinors and subject to Lorentz group action

and to construct the well-known Lorentz invariant action in a flat spacetime

The action is generalised for curved spacetime via vierbein . In a curved spacetime, one relates an arbitrary frame with a local inertial frame via vierbein . Its Latin indices are subjected to the Lorentz transformation; Greek indices are subjected to the general coordinate transformations. In turn, vierbein satisfies the following normalisation condition:

They define an anti-symmetric spin-connection that is related to the Christoffel symbols.

Since the vierbein connects Lorentz transformations and general coordinate transformations, one uses it to manipulate indices. This construction forms a set of matrices that are subject to the general coordinate transformation group:

Spinor transformations (93) are generalized as follows:

This generalisation promotes transformation (93) to gauge transformations.

Regular derivatives are replaced with covariant derivatives defined as follows:

Covariant derivatives defined in such a way satisfy the following relations:

This construction produces the following generalisation of the Dirac action

Here, m is the fermion mass, is the vierbein, and ∇ is the fermionic covariant derivative. We shall note that we omit a few steps in deriving this action. Namely, the action does not contain either Christoffel or spin connection. The reason for this is discussed in detail in [24].

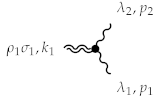

The following theorem describes the perturbative structure of the Dirac action.

Theorem 24.

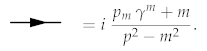

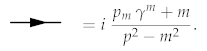

The background contribution describes the standard fermion propagator:

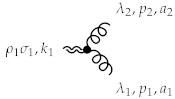

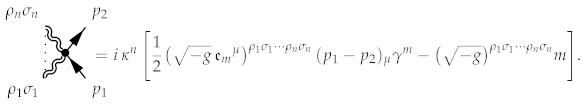

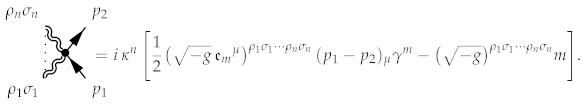

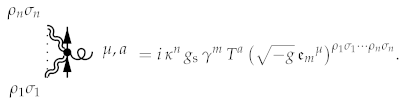

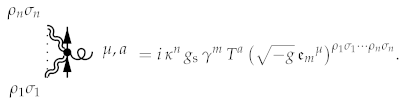

The other terms describe the following interaction rules:

This expression also holds in the Yang–Mills model considered below.

4.4. Proca Field

For quantum field theory, the existence of a vector field mass is crucial. A vector field with zero mass admits a gauge symmetry, which means gauge fixing must be performed. On the other hand, a vector field with a non-vanishing mass, the Proca field, has no gauge symmetry, and the gauge fixing is not an issue. We begin the discussion with the Proca case for the sake of simplicity.

The action describing a Proca field reads:

Here, is the field tensor, m is the vector field mass. The action admits the following factorisation:

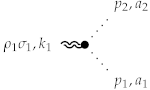

The following theorem describes the Fourier structure of the action.

Theorem 25.

Here, we introduced the following notations:

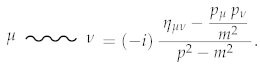

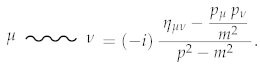

This expression generates the Proca propagator:

The expression describing the interaction rules between gravitons and the Proca field kinetic energy is as follows:

4.5. Vector Field

Before discussing the massless case, we shall recall the Faddeev–Popov prescription [39]. The following generating functional describes a quantum massless vector field:

The integration space includes all conceivable configurations of the vector field. Firstly, we shall add a new term to the microscopic action:

Here, is an arbitrary scalar, and is a free gauge fixing parameter. The new contribution is a Gauss-like integral, so its introduction merely changes the omitted normalisation factor.

Secondly, we split the integration volume:

In this expression, is the gauge fixing condition, is the gauge transformation parameter, and the new field variable and the field variable A are related as follows:

The integration over is performed over all conceivable fields. Because of the function, only a single representative from each class of physically equivalent potentials contributes to the integral. Lastly, the Faddeev–Popov determinant preserves the invariance of the integration measure. The corresponding differential operator is defined as follows:

Finally, we perform integrations and obtain the following expression for the generating functional:

Here, and c are scalar anticommuting Faddeev–Popov ghosts introduced to account for the Faddeev–Popov determinant. We omit the integration over the gauge parameter , as it is irrelevant due to the normalisation.

This prescription generates a functional suitable for treating gauge models. We chose the standard Lorentz gauge fixing condition for simplicity. In a curved spacetime, it reads:

The following theorem describes the perturbative structure of the gauge invariant part of the action.

Theorem 26.

This expression matches the expression for the Proca field with .

The structure of the gauge fixing term is more sophisticated.

Theorem 27.

The following theorem gives the Fourier structure of the gauge fixing term.

Theorem 28.

The following notations for the Christoffel symbols were used.

The background part of this expression corresponds to the standard propagator:

The corresponding interaction rule reads:

The dots in this expression represent terms that create symmetry with respect to graviton momenta. The final term only affects vertices with two or more gravitons.

We treat the ghost sector of the theory as follows. The Faddeev–Popov differential operator reduces to the D’Alamber operator in curved spacetime:

The ghost part of the functional describes a single massless scalar ghost coupled to gravity:

The following theorem gives the corresponding perturbative expansion.

Theorem 29.

We recover the standard ghost propagator:

and in the following interaction rule:

and in the following interaction rule:

Let us note again that the discussed ghosts are the standard Faddeev–Popov ones. In the context of gravity, there is one additional reason to account for them. The vertex in a diagram represents the interaction between gravitons and vectors, including physical and non-physical vector field polarisations. The coupling of Faddeev–Popov ghosts to gravity cancels out the energy contribution from non-physical polarisations.

4.6. SU(N) Yang–Mills

Let us turn to the gravitational interaction of the Yang–Mills model. In the flat spacetime, the Yang–Mills model is given by the following action:

The fermion covariant derivative is defined in the standard way:

Field tensor reads

The gauge field takes value in algebra:

where are generators. In turn, field tensor components are given by the following:

Here are the structure constants of the algebra:

Action (129) is generalised for the curved spacetime case as follows. One replaces all derivatives with covariant derivatives and makes explicit the invariant volume factor. Such a generalisation results in the following action:

Here, is a vierbein. The covariant derivative for fermions now reads

with begin the part accounting for the spacetime curvature via the spin connection. The field tensor is defined via covariant derivatives. However, it does not involve Christoffel symbols due to its structure:

This results in the following Yang–Mills action in curved spacetime:

The perturbative quantisation of kinetic parts of the action is discussed above. The following theorem gives the perturbative expansion for the coupling of fermions to a gauge vector.

Theorem 30.

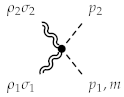

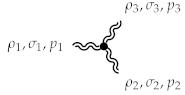

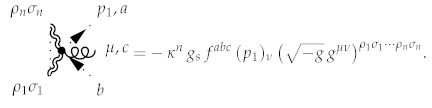

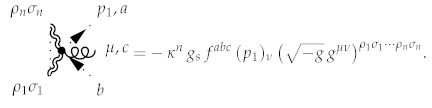

This expression produces the following Feynman rule:

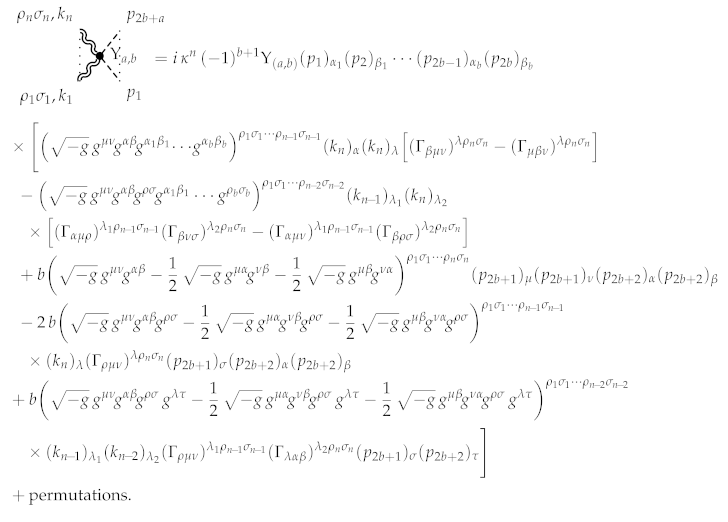

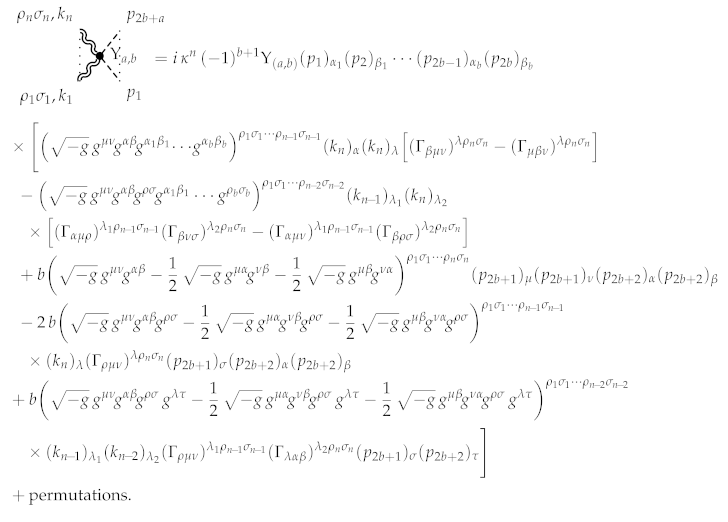

The perturbative expansion for the cubic term in gauge vectors takes a similar form.

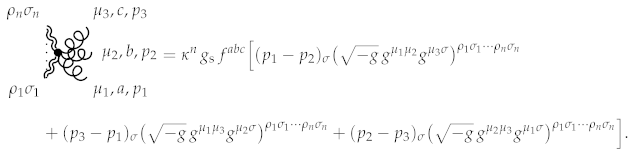

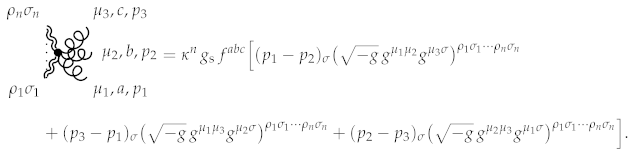

Theorem 31.

This expression produces the following rule:

Lastly, the four-vector coupling term has the following perturbative structure.

Theorem 32.

This results in the following interaction rule:

Finally, we are going to discuss gauge fixing. The Yang–Mills action respects the following gauge transformations:

Here, are the gauge parameters. The standard Lorentz gauge fixing conditions simplify calculations in a flat spacetime.

For the case of curved spacetime, the covariant derivative replaces the standard derivative, which produces the new form of the Lorentz gauge fixing conditions:

Introducing this gauge fixing term will bring the kinetic part of the vector field to the same form discussed in the previous section.

The ghost action is defined by the Faddeev–Popov determinant obtained from the gauge fixing condition:

It results in the following action:

The action’s kinetic part is similar to a massless vector field. The section describing the interaction between ghosts, vectors, and gravitons allows for a perturbative expansion.

Theorem 33.

This expression produced the following rule:

4.7. General Relativity

General relativity is invariant with respect to local transformations spawned by coordinate transformations, so a gauge fixing procedure shall be performed. The perturbative approach describes gravity as small metric perturbations over a flat background. Therefore, it may seem that the theory is reduced to a gauge theory of rank-2 symmetric tensor, but this is not the case.

One shall distinguish a geometric theory from a theory of a rank-2 symmetric tensor. The difference dictates how to treat the gauge fixing condition. First, let us consider the case of a symmetric tensor theory that admits the following gauge symmetry:

The tensor is fundamental to this theory, and a gauge fixing condition can be expressed solely in terms of it. For example, one can use the following gauge fixing condition:

This condition, along with others, determines the composition of the Faddeev–Popov ghosts. Because is the fundamental object of the theory, the structure of divergences can only be expressed in terms of alone. All geometric quantities, such as the Riemann tensor, Ricci tensor, scalar curvature, and others, are expressed via small metric perturbations, but the opposite is not true. Operators given in terms of alone may not represent any geometric quantities. Therefore, in a gauge theory of a rank-2 symmetric tensor, one can expect to find divergences that cannot be described by geometric quantities, which makes it a non-geometric theory.

On the contrary, gauge transformations are generated by coordinate frame transformations within the geometric approach. This has two immediate implications. Firstly, within a geometrical theory, gauge transformations are given by the so-called Lie derivatives:

Here, is the Lie derivative with respect to an arbitrary vector field , which contains the gauge transformation parameters. Secondly, the gauge fixing condition must be expressed in geometrical quantities. Thus, gauge fixing conditions (153) are inconsistent with the geometrical approach and cannot be implemented. Instead, we use the following gauge fixing conditions:

Combined with the perturbative expansion given by Equation (1), the gauge fixing conditions represented by Equation (155) produce an infinite series.

The infinite expansion defines the ghost sector, and the leading term reproduces naive gauge fixing (153).

The difference between geometrical theories of gravity and a gauge theory of tensor is marked by the need to use gauge fixing condition (155), and not conditions (153). Proceeding with The Faddeev–Popov prescription, firstly, we shall note that the gauge fixing condition defined by (155) is a vector with mass dimension . Thus, one shall introduce an additional dimensional parameter in the gauge fixing term:

Secondly, the Faddeev–Popov ghosts are also vectors. The structure of their action is defined by the variation in the gauge fixing term given by Equation (155):

with begin the Ricci tensor. Consequently, the ghost action reads:

In all other respects, the handling of the Faddeev–Popov ghosts is unchanged.

The standard perturbative expansion generates the interaction rules. The structure of graviton interactions is given by action (157):

It admits the following perturbative expansion:

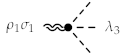

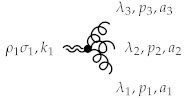

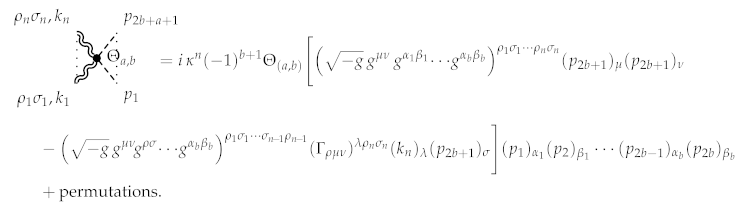

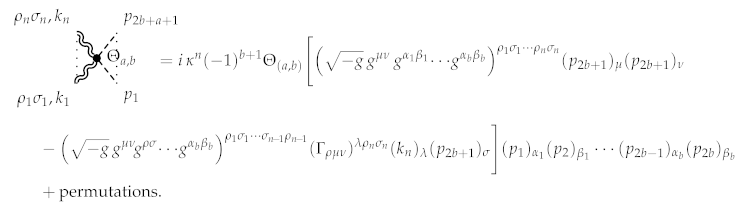

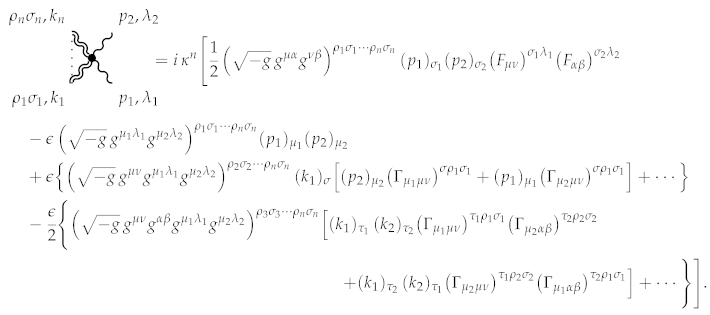

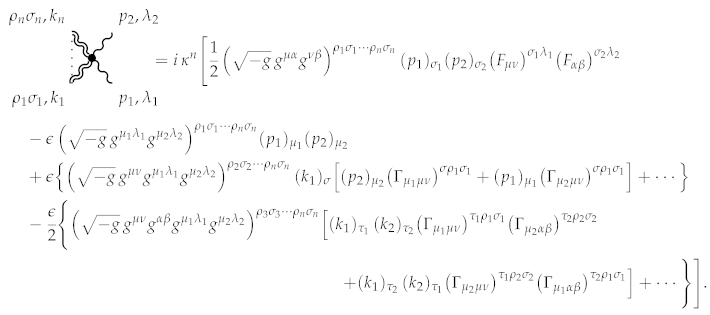

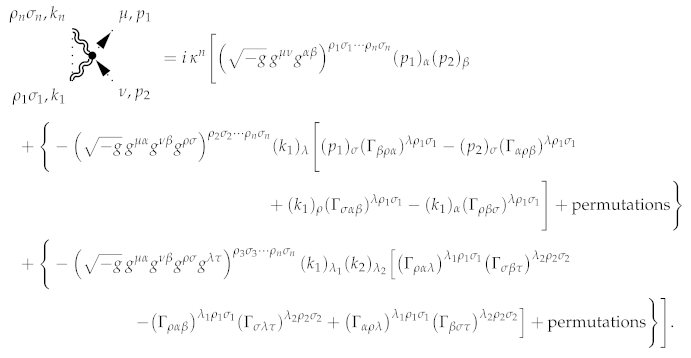

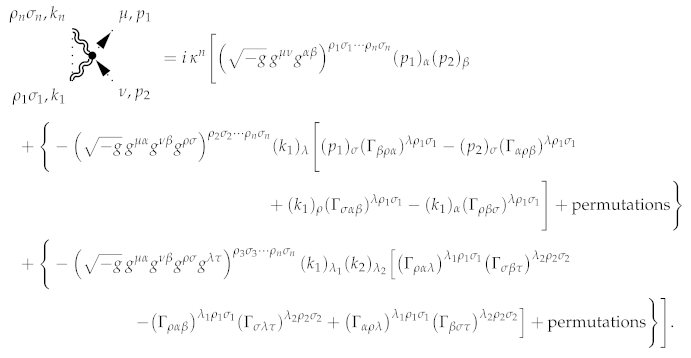

Theorem 34.

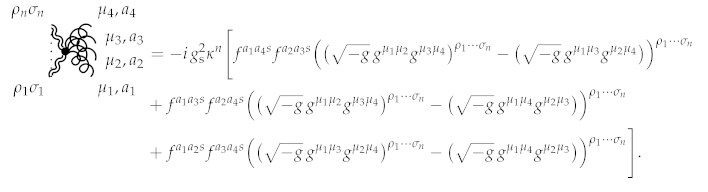

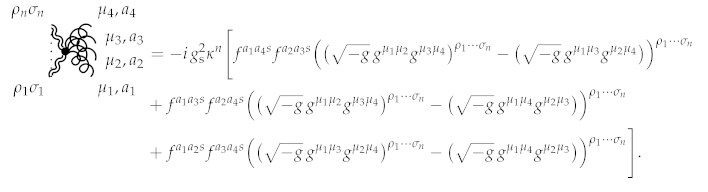

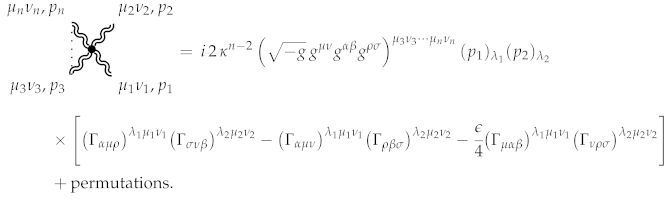

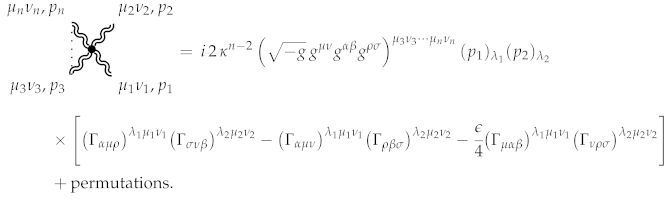

The following formula gives the complete expression for the graviton vertex:

The sum goes over all possible permutations of graviton parameters .

The ghost action is treated similarly.

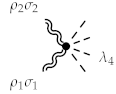

It has the following perturbative expansion:

Theorem 35.

The complete expression describing graviton-ghost vertices reads:

The standard procedure derives propagators for ghosts and gravitons. The following expression gives the ghost propagator.

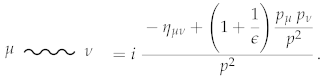

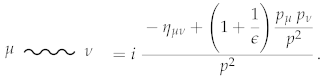

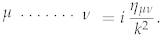

The graviton propagator contains the gauge fixing parameter . The propagator corresponds to the part of the microscopic action quadratic in perturbations:

The Nieuwenhuizen operators provide a good mean to express the operator in the momentum representation [38,88]

Operators and are gauge invariant, making the operator non-invertible unless . The inverse operator reads:

The given formula expresses the graviton propagator in any arbitrary gauge.

We can discuss the general case, but using in practical applications is easier. With this value, the operator becomes much simpler in form:

5. FeynGrav

FeynGrav is a package for Wolfram Mathematica extending FeynCalc functionality [27,28]. FeynCalc provides tools to study both tree and loop-level amplitudes. At the same time, there are many packages further extending its functionality [87,89,90], which makes it a platform for different computational tools of high energy physics. Because of these reasons, FeynCalc was chosen to implement the perturbative quantum gravity framework described above.

This subsection is split into two parts to discuss two different aspects of FeynGrav. The first subsection discussed the general features of the package and its published versions. The second subsection discussed the commands implemented in the latest available version.

5.1. Implementation

We shall begin with a discussion of the existing versions of FeynGrav. There are a few published versions of the package, each extending its functionality and improving performance. The package is constantly developing, and the latest version is publicly available at [91]. We shall briefly discuss the features of all these versions for completeness.

The original version 1.0 of FeynGrav was published in [24]. This version only considered matter with massless spin 0, 1, 2, and , and did not include the Yang–Mills model. The recursive relations discussed in this paper were yet to be discovered during the development of this version. Consequently, the package used a less effective algorithm to generate all perturbative expansions. The package’s applicability was also limited, since the gauge-fixing algorithm was not considered in detail.

The second version published in [25] presented a significant update. This version added interaction rules for massive matter with spins 0, 1, , and implemented rules for the Yang–Mills. The gauge-fixing procedure was fully addressed, so the implemented interaction rules became applicable at any perturbation theory level. However, the recursive algorithm still needed to be discovered, so the package used the same algorithm for perturbative expansions.

The recursive relations were discovered after the publication [25], and were implemented in the latest FeynGrav version 2.1. The discovery of the recursive algorithm allowed expressions for the interaction rules to be generated more efficiently, so the corresponding libraries were updated. This version also implemented the polarisation tensors for gravity, discussed below. Lastly, minor misprints were corrected, and the sample file was significantly updated and improved.

The interaction rules for the Horndeski theory still need to be implemented in any existing version of FeynGrav. Because of their shared length and complexity, their implementation takes time and is expected to be published soon.

Let us discuss the package structure that remains similar in all the versions. The package addressed a few different challenges, consisting of a few semi-independent modules. The main computational challenge is the generation of the perturbative expansion terms. The package’s core addresses this problem, but operates separately from the main file. In turn, the main file of the package only imports the interaction rules in the FeynCalc environment, allowing a user to operate with them.

The above recursive relations are implemented in a series of sub-packages in a separate folder. Each package provides a tool to calculate a separate family of tensors, and can be used independently within FeynCalc. As discussed above, it is essential to introduce tensors with particular symmetry for the Lorentz indices. With this symmetry imposed, a typical tensor with pair of Lorentz indices will have approximately terms. Because of this large number of terms, a computation of an interaction rule involving many particles can take significant time. To soften this issue, the interaction rules are calculated separately.

The interaction rules discussed above are implemented in a single separate sub-package. Because such rules only require information about perturbative expansions, this sub-package depends on sub-packages describing perturbative expansions. It shall be run independently from FeynGrav to generate libraries containing the final expressions for the interaction rules.

The main package file is directly independent of these sub-packages, since it only imports the existing libraries and places them in the FeynCalc environment. Because of this package structure, the final user does not have to perform computationally heavy calculations of the interaction rules, significantly improving the package performance. When FeynGrav imports the rules, FeynCalc performs index contractions and other operations that constrain FeynGrav’s performance.

5.2. Interaction Rules

The scalar field kinetic and potential energy interaction rules are implemented with commands “GravitonScalarVertex” and “GravitonScalarPotentialVertex”. The first command takes four arguments: the array of graviton indices, two momenta of scalar fields, and the scalar field mass. The second command takes two arguments: the array of graviton indices and the scalar field coupling coupling. FeynGrav also contains a command realising the scalar field propagator. The command is “ScalarPropagator”, and takes two arguments: the scalar field momentum and mass. Table 1 presents examples of these commands’ usage.

Table 1.

Examples of interaction rules for the scalar, Proca, and massless vector fields.

Interaction rules for the Proca field are implemented with a single command “GravitonMassiveVectorVertex”. The name is chosen for the sake of naming consistency. The command takes six arguments: the array of graviton indices, the Lorentz index and momentum of the first vector particle, the Lorentz index and momentum of the second vector particle, and the Proca field mass. The package also has the Proca propagator implementation. The command “ProcaPropagator” implements the propagator, and takes four arguments: two Lorentz indices, and the momentum and mass of the Proca field. Table 1 presents examples of these commands’ usage.

The interaction rules for a single massless vector field are implemented with two commands, “GravitonVectorVertex” and “GravitonVectorGhostVertex”. The command “GravitonVectorVertex” takes five arguments: the array of Lorentz indices and momenta of gravitons, the Lorentz index and momentum of the first vector particle, the Lorentz index and momentum of the second particle. The command “GravitonVectorGhostVertex” takes three arguments: the array of Lorentz indices and momenta of gravitons, and the momenta of the Faddeev–Popov ghost. Table 1 presents examples of these commands. Let us also note that FeynCalc already provides the propagators required to treat a massless scalar field.

The interaction rules for Dirac fermions are implemented with a single command “GravitonFermionVertex”. The command takes four arguments: the array of graviton Lorentz indices, the momentum of the in-going fermion line, the momentum of the out-going fermion line, and the fermion mass. The fermion propagator has already been implemented in FeynCalc. Table 2 provides an example of this interaction rule.

Table 2.

Examples of interaction rules for the scalar, Proca, and massless vector fields.

The Yang–Mills model implementation is sophisticated and involves several commands. The command “GravitonGluonVertex implements a coupling of a few gluons to gravity. The command’s first argument is an array of Lorentz indices and momenta. The other arguments describe gluons Lorentz indices, momenta, and indices. The command can describe a coupling of two, three, and four gluons to gravity. Gravitational coupling of quarks kinetic energy matches the expression for the coupling of a Dirac fermion. The coupling of the quark–gluon interaction energy is described by the “GravitonQuarkGluonVertex” command. It takes only three arguments: the array of graviton Lorentz indices, the quark–gluon vertex Lorentz index, and the colour index. Lastly, two commands are responsible for gravitational coupling to the Faddeev–Popov ghosts of the Yang–Mills theory. The command “GravitonYMGhostVertex” describes the coupling to the ghost itself. The command takes five arguments: the array of graviton Lorentz indices, the momentum and colour index of the first ghost, and the momentum and colour index of the second ghost. The command “GravitonGluonGhostVertex” corresponds to the gravitational coupling of a vertex describing the interaction between two ghosts and one gluon. The command’s arguments are the array of graviton Lorentz indices, the Lorentz indices, momenta, and colour indices of other particles. Table 2 lists examples of these commands.

Lastly, the following commands describe the gravitational sector. The command “GravitonPropagator” implements the graviton propagator with “FeynAmpDenominator” functions from FeynCalc. This command shall be used for loop calculations. The command “GravitonPropagatorAlternative” implements the graviton propagator with the simple scalar products in the denominators. This command shall only be used in three-level calculations. Two more commands, “GravitonPropagatorTop” and “GravitonPropagatorTopFAD”, generate the numerator of the graviton propagator alone. The first one uses simple scalar products, while the second one uses “FeynAmpDenominator”. All these commands take five arguments: four Lorentz indices and the momenta of a graviton. The command “GravitonVertex” corresponds to the n-graviton vertex and takes arguments: two Lorentz indices and the momentum of each graviton. The Faddeev–Popov ghosts are vectors, so their propagator receives an additional Minkowski metric in the numerator. One can use the command for the Yang–Mills ghost propagator and manually multiply it on the flat metric. Because of this, no new command corresponding to this propagator is present in FeynGrav. Lastly, the rules for graviton coupling to the corresponding Faddeev–Popov ghosts are implemented with “GravitonGhostVertex”. It takes five arguments: the array of Lorentz indices and momenta of the gravitons, and Lorenz indices and momenta of ghosts. Table 3 presents these rules.

Table 3.

Examples of interaction rules for gravitons.

FeynGrav also implements a few additional tools. Firstly, the package provides a realisation of the standard gauge projectors:

They are realised with commands “GaugeProjector”, “GaugeProjectorBar”, “GaugeProjectorFAD”, and “GaugeProjectorBarFAD”. The first two commands realise these projectors with the simple scalar products, while the former two commands use “FeynAmpDenominator”.

Secondly, the package provides a realisation of the Nieuwenhuizen operators [38,88,92]. These operators , , , , generalise the standard projectors for the spin-2 systems. Their features were discussed in detail in a previous publication [24]. Commands “NieuwenhuizenOperator0”, “NieuwenhuizenOperator1”, “NieuwenhuizenOperator2”, “NieuwenhuizenOperator0Bar”, and “NieuwenhuizenOperator0BarBar” implement these operators using only the simple scalar product. The set of command “NieuwenhuizenOperator0FAD”, ⋯, “NieuwenhuizenOperator0BarBarFAD” implements them with “FeynAmpDenominator”.

Lastly, the package implements the polarisation tensors for gravitons. Following the standard procedure, the polarisation tensor for gravitons is defined through the polarisation vector for the standard vector field:

The command “PolarizationTensor” implements this definition. The command takes three arguments: two Lorentz indices and one four-momentum. The command directly multiplies polarisation vectors implemented in FeynCalc. Due to the definitions used in FeynCalc, the implemented polarisation tensor is neither traceless nor transverse—the command “SetPolarizationTensor” the tensors traceless and transverse.

5.3. Examples

Several publications have used FeynGrav [24,25,32,33,35]. These publications discuss the problems in detail, so we will only provide a brief discussion. We also focus on two vivid examples.

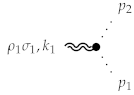

The first illustrative example of FeynGrav usage is the calculation of graviton scattering cross sections at the leading order of perturbation theory. The on-shell cross section was calculated long ago without using any contemporary computational tools [10], which makes such calculations notoriously complicated. To be exact, in the original article [10], the author operated with expressions symmetries in a certain way to make the calculation more compact. Nonetheless, even the basic description of the calculations takes a few pages in the original publication.

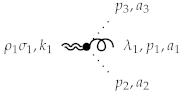

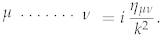

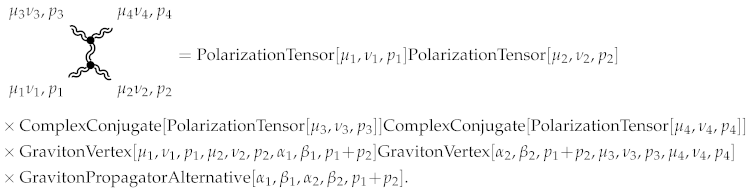

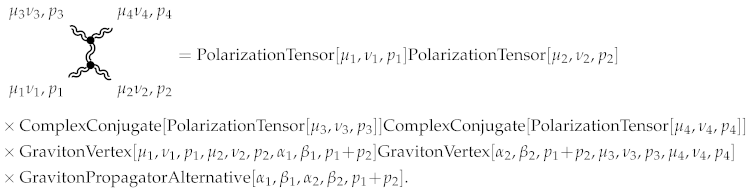

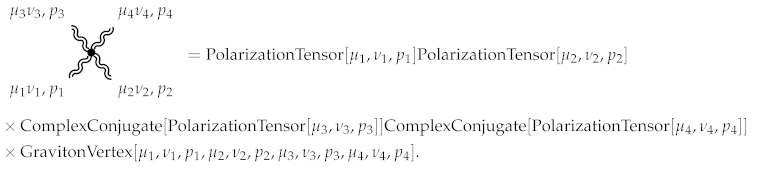

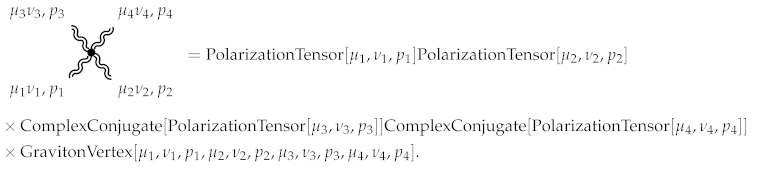

FeynGrav extremely simplifies such calculations. Firstly, one shall fix all the momenta on the mass shell and define all relations for scalar products of polarisation tensors and momenta, since FeynCalc does not do this automatically. Secondly, one calculates the matrix element for the s-channel amplitude:

An average computer not designed for intensive computational tasks can complete this element in less than five minutes. One obtains the expressions for t and u-channels similarly. The following expression gives the contact four-graviton interaction:

This expression takes less than one minute to be computed.

Lastly, one constructs the complete scattering amplitude accounting for all contributions. It recovers the well-known expressions for chiral amplitudes in :

This example vividly shows that such complicated yet essential calculations are significant with FeynGrav. Moreover, paper [24] presents an explicit expression for the scattering amplitude expressed in terms of graviton chiralities.

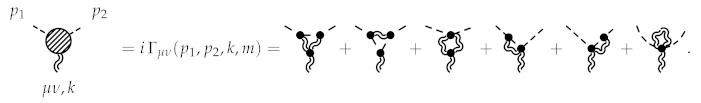

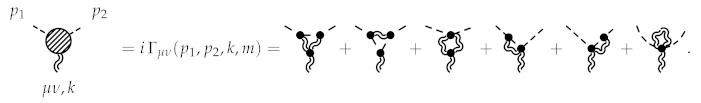

The second example is the calculation of the one-loop graviton-scalar vertex operator. Since a scalar field interacts with gravity, the interaction vertex receives correction at the loop level. The one-loop vertex operator describes these corrections:

In contrast to the previous example, this expression was only calculated with FeynGrav because it involved hundreds of terms. The expression itself is too long to be presented in printed form. It is published in an open-access repository [93]. The obtained expression allows one to study the low energy limit of a gravitational scattering of two scalars [33]:

In this expression for the differential cross section, p is the centre of mass scattering momentum, is the scattering angle, and are masses of the scattered particles, and is the reduced mass.

6. Summary and Further Development

This paper reviews a recently developed theoretical framework for efficient computation of Feynman rules for perturbative quantum gravity. The perturbative approach to quantum gravity allows one to study quantum gravitational effects within the standard quantum field theory framework. The resulting theory is effective, so it cannot be indefinitely extended in the ultraviolet region and treated similarly to other renormalisable theories. Due to its effective nature, the theory admits infinite interaction terms, all parametrised with a single gravitational coupling. The discussed theoretical framework provides a universal way to compute such interaction rules at any order of perturbation theory.

Perturbative quantum gravity admits the factorisation theorem applicable to any gravity model within Riemann geometry. The theorem states that the action splits into two parts in a broad class of gravity models. One part does not involve derivatives, and is constituted of three independent factors that are infinite series. The other part involves derivatives, but it is a finite expression that can be calculated explicitly.

Certain recursive relations exist for the factors generating infinite series. They provide a way to efficiently calculate their contribution at any order of perturbation theory. However, the number of terms in each contribution grows faster than the factorial number of particles involved in the interaction. This feature makes manual calculations of such factors challenging.

FeynGrav provides a tool to operate with the theory at the practical level. It implements the discussed theoretical framework within FeynCalc, which possesses a broad spectrum of tools to operate with expressions within the quantum field theory.

The latest version implements the interaction rules for massless and massive scalars, for scalar field potential interaction, for massive and massless Dirac fermions, for Proca field, for massless vector field, for Yang–Mills model, and general relativity. The package also implements auxiliary tools such as graviton polarisation tensors, gauge projectors, and their generalisation for the spin-2 case.