1. Introduction

Mathematical modeling has gained much attention in the scientific community as it helps describe real problems and enables a better understanding of the system in consideration. It has been used to model problems in various fields including, but not limited to, physics, biology, chemistry, and economy [

1,

2,

3]. More specifically, mathematical models have been used to model infectious diseases and help public health decision-makers obtain more insights into the dynamical spread and controllability of various infectious diseases [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Among these diseases is pertussis, which is highly contagious, fatal, re-emergent, and circulates worldwide. Its bacteria can easily spread directly from person to person through droplets produced during coughing, sneezing, or even talking. Generally, an infected individual can spread the disease when being in close contact with others within up to approximately one meter. Pertussis is highly incidental during winter and spring seasons among children below 5 years of age because children in this age group are not yet fully vaccinated.

Pertussis is endemic in the United States and most common among young children in developing countries, while it is highly incident among unvaccinated babies and increases again among teens in the developed world. Moreover, it is controllable with strategies based on vaccination [

12]. However, it is evident that pertussis vaccines do not confer permanent immunity, yet the immunity acquired due to either vaccination or naturally experiencing pertussis infection declines/wanes with time [

13,

14,

15].

The literature shows differences in the period of immunity acquired by vaccination and natural infection. More specifically, for a number of infectious diseases (e.g., measles, influenza A, COVID-19, and pertussis), the duration of immunity acquired by vaccination is shorter than that acquired by infection, as it is shown that naturally infected patients have higher antibody titer than vaccine recipients [

16,

17]. For the case of pertussis, definitely, these differences are evident, where in a study on the Senegal population for example, Broutin et al. [

18] showed that the gap between two pertussis episodes is 7.1 years in unvaccinated children and 5.1 years in previously vaccinated children. However, Wendelboe et al. [

15] showed that vaccine-acquired immunity lasts 4–12 years in children, while infection-acquired immunity wanes after 7–20 years.

The waned immunity is believed to be subsequently boosted by asymptomatic encounters with the infection [

19,

20]. The interplay between waning and boosting pertussis immunity by exposure to Bordetella pertussis and vaccination affects its transmission dynamics and needs a mathematical model for a true understanding. Various models that take these considerations into account have been developed and analyzed. For example, Carlsson et al. [

21] introduced and studied a partial differential equation SIS model of waning and boosting (by repeated vaccination) with discrete immunity classes, but continuous age and time. However, Ehrhardt et al. [

22] derived an SIR model to describe vaccination and the waning of immunity. The authors derived some qualitative results and introduced a finite difference scheme to solve the system. Moreover, Elbasha et al. [

23] extended the basic SIRS model by including a compartment for imperfect vaccination to study the waning of immunity acquired either naturally or by immunization. In their model, the authors did not differentiate between primary susceptible, secondary susceptible, and waned-immunity individuals, but allowed for vaccinated individuals to either progress directly to the susceptible state or acquire the infection due to successful contact with infected ones. However, very recently, Opoku-Sarkodie et al. [

24] extended the basic SIRS model to incorporate the waning and boosting of immunity due to repeated exposure to the infection in the absence of any vaccination scheme. The authors have mathematically analyzed how the different partitioning of the immune period into recovered and waned and varying boosting rates affect the dynamics of the model. In this paper, the last two-mentioned works have been extended by including routine vaccination (whose immunity wanes and has a shorter immunity period than that acquired by natural infection), including an independent compartment of waned individuals, and considering differences in susceptibility between primary and secondary susceptible individuals. Therefore, an SIVRWS (where W stands for waning) model is introduced and thoroughly analyzed. We are especially interested in investigating the effects of the interplay between waning and boosting immunity (by repeated exposure to the infection) on the overall dynamics. Other works include those by Barbarossa et al. [

25] and Lavine et al. [

20].

Our work is organized as follows. The model is formulated and proved to be well-posed in

Section 2. Its equilibrium and stability analyses are shown in

Section 3. Uniform persistence is shown in

Section 4, while the controllability of pertussis infection is studied in

Section 5.

Section 6 shows the impact of waning and natural boosting of immunity on disease outcomes. Finally, the work is closed with a summary, conclusion, and future work in

Section 7.

2. Model Formulation

The population of interest is assumed to be closed and demographically stationary. According to their epidemiological states, the individuals are categorized into six mutually independent groups. These are primary susceptible individuals (i.e., individuals who have never experienced the infection and whose proportion in the total population at time

t is denoted by

), vaccinated individuals (i.e., newborns who got vaccinated immediately after birth and whose proportion in the population at time

t is denoted by

), infected individuals (i.e., individuals who are infected and capable of transmitting the infection and whose proportion at time

t is denoted by

), recovered or boosted highly immune individuals (i.e., individuals who recently recovered from the infection or whose immunity have been naturally boosted due to re-exposure to the infection, and whose time-dependent proportion in the total population is denoted by

), waned immunity individuals (i.e., individuals whose immunity acquired by vaccination or due to recovery after experiencing the infection, declined but are still protected from acquiring the infection and of proportion in the total population at time

t is denoted by

), and secondary susceptible individuals (i.e., individuals who partially lost their acquired immunity and whose proportion at time

t is denoted by

). The individuals in these compartments are asymmetric in their epidemiological status, but symmetric in their mixing behavior in the sense that they mix homogeneously. A brief description of the model variables is shown in

Table 1.

It is worth mentioning that the compartment of vaccinated individuals is recruited by newborns who got primarily immunized following the schedule of doses recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). I.e., it is the routine pertussis vaccination recommended for infants. However, waned immunity individuals are those who lost some of their protective antibodies but still have at least a minimum level of antibodies that protects them against the causative antigen or the disease. The progressive loss of the protective antibodies moves an individual from the compartment of waned to that of secondary susceptible who are assumed to be partially protected against the disease.

It is assumed that individuals are born primarily susceptible and die naturally at the same rate

, where a proportion

p of the newborns gets vaccinated at birth. Due to successful contacts with infected individuals, primary susceptible ones acquire the infection at an infection rate

, where

is the successful contact rate between

and

I individuals. Infected individuals recover from the infection at rate

, but their naturally-acquired immunity declines, and they become waned at rate

. The vaccine-acquired immunity for vaccinated individuals is assumed to decline at a rate

and they become waned, where

b is a rescaling parameter accounting for the relative loss in the vaccine-acquired with respect to the naturally-acquired immunity. The immunity of waned individuals either rises due to their contacts with infected individuals (at the rate

) or it continues to decline (at rate

), where they become secondary susceptible, who may acquire the infection at a force of infection

, where

is the relative susceptibility of secondary susceptible with respect to primary susceptible individuals. A schematic diagram for the transition between the model states is shown in

Figure 1 and a detailed description of the model parameters’ physical meaning is presented in

Table 2. The parameter values have been chosen to represent (to a high extent) the case of pertussis, see

Table 3. Therefore, the population dynamics is described by the following differential equation system

with initial conditions

where all parameters are assumed to be positive, while the model states are defined on the set

The mathematical analysis of the basic properties of model (

1) shows that

is positively invariant and model (

1) has a unique time-dependent solution, see

Appendix A for more details. This result is briefly stated in the following proposition.

Proposition 1. Model (1) has a unique time-dependent solution and any solution starting with non-negative initial conditions remains non-negative and ultimately bounded for all . Moreover, the set Ω is positively invariant and attracts all solutions in . 4. Uniform Persistence

Before going into detail on the persistence of the infection, we present a result on the global stability of the infection-free equilibrium. The global stability of the infection-free equilibrium

is discussed by following the approach presented in Castillo-Chavez et al. [

33]. Accordingly, model (

1) could be rewritten as

where

denotes the components of uninfected individuals and

denotes the components of infected individuals. Let

denote the IFE of the model (

18), which is equivalent to the IFE of model (

1). Thus, the global stability of the infection-free equilibrium depends on the following two conditions.

For , is globally asymptotically stable.

, where for ,

where the Jacobian matrix

has all non-negative off-diagonal elements, and

is the region where the model makes biological sense. Then, we present the following proposition, whose proof is deferred to

Appendix C.

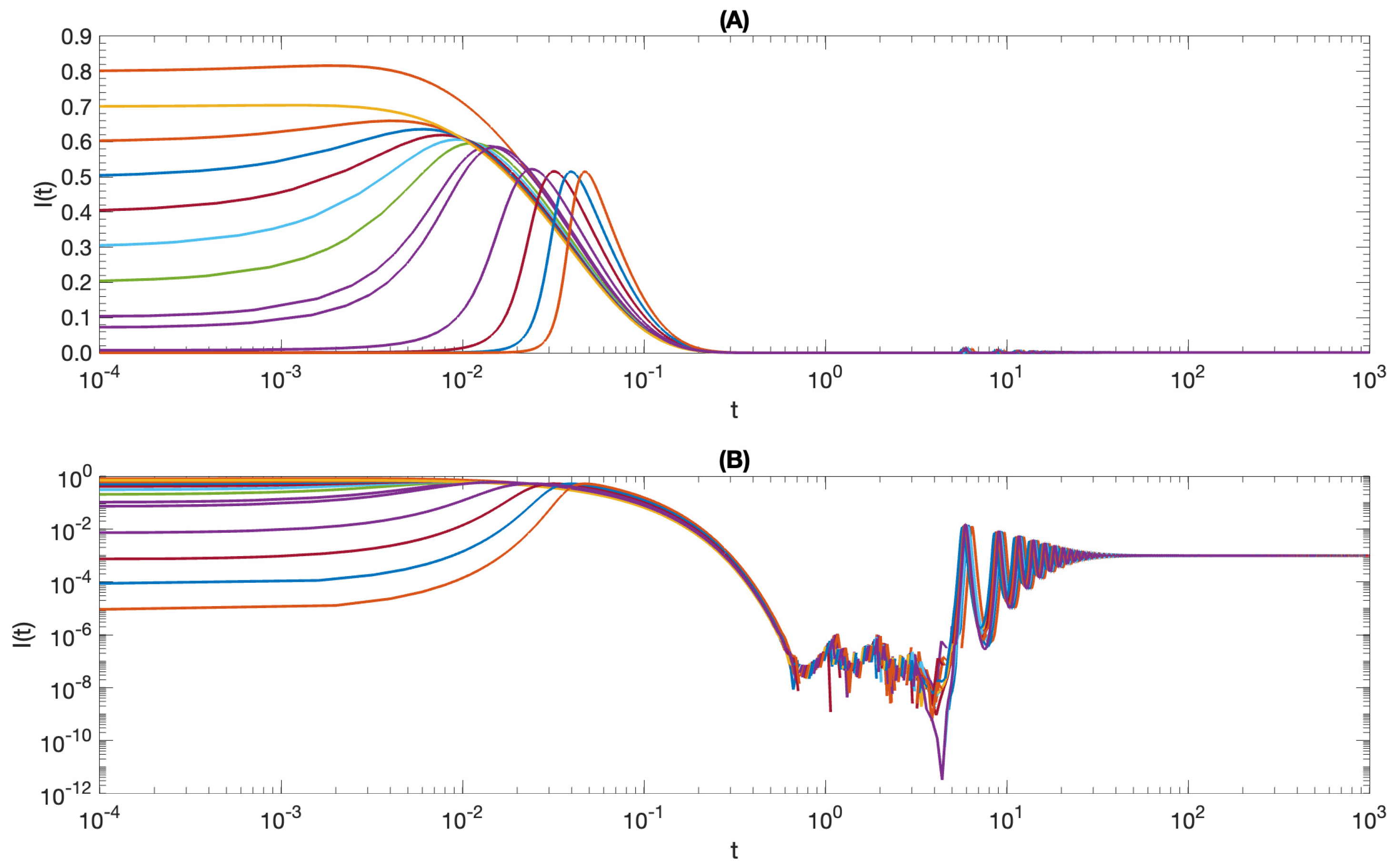

Proposition 5. Infection-free equilibrium of model (1) is globally asymptotically stable in Ω if and above conditions are satisfied. Based on the use of the Rung–Kutta method of order four, extensive simulations for model (

1) have been performed and some of them are shown in

Figure 3. The simulations show that all time-dependent solutions starting in the region

(with parameter values such that

, while keeping the other parameters as in

Table 3) are attracted by the infection-free equilibrium

.

Now, we study the uniform persistence of the model (

1). This model is said to be uniformly persistent [

34,

35] if there exists some

such that its time-dependent solution, with positive initial conditions, satisfies

We first show that the compartments of non-negative sub-populations

,

and

are always uniformly persistent, regardless of the value of the control reproduction number

. Then, we prove the uniform persistence of the disease’s compartment

(when

), by using persistence results from Smith and Thieme [

36].

Our proof is based on the use of the fluctuation lemma (see Appendix A of [

36]). To this end, we let

be a real-valued function, and the limit superior and the limit inferior of

f as

be defined as

To prove the persistence of the primary susceptible sub-population

, we let

. On applying the fluctuation lemma, there exists a sequence

such that

and

as

, where the over-dot indicates the derivative with respect to time

t. If we apply this to the

-equation in model (

1), we obtain

From Proposition 1, we have

. Hence,

. Using this and letting

, we obtain

Hence,

is always uniformly persistent.

Similarly, we apply the fluctuation lemma to the

and

equations in (

1) and use the fact that

. There exists a sequence

such that

and

as

. Hence,

Moreover, there can exist a different sequence

such that

and

as

. Hence,

Finally, there can also exist another sequence

such that

and

as

. Hence,

Thus, the non-infected compartments

and

are also uniformly persistent. Therefore, we state the following proposition.

Proposition 6. The time-dependent solutions of the non-infected sub-population compartments and are always uniformly persistent.

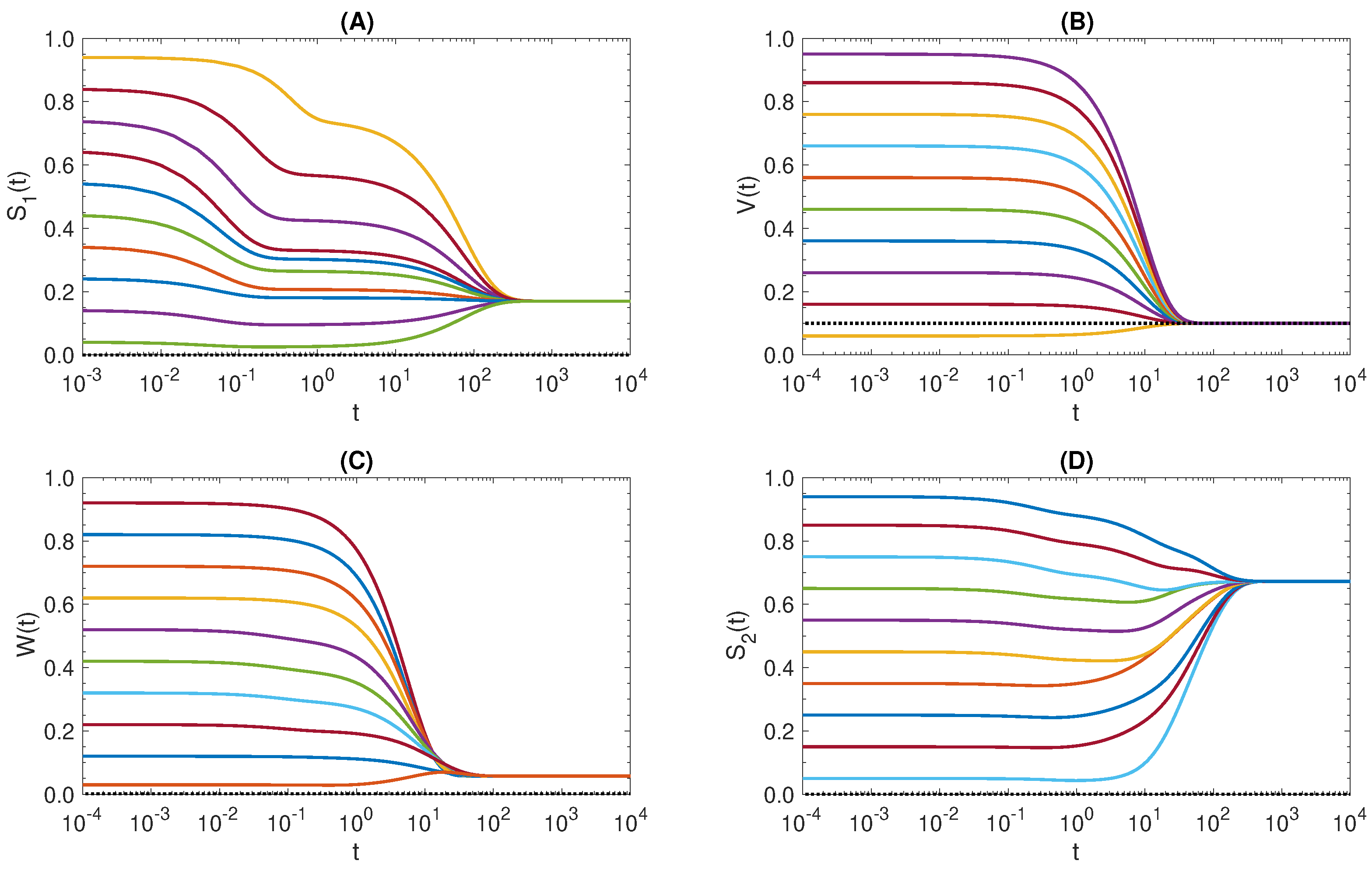

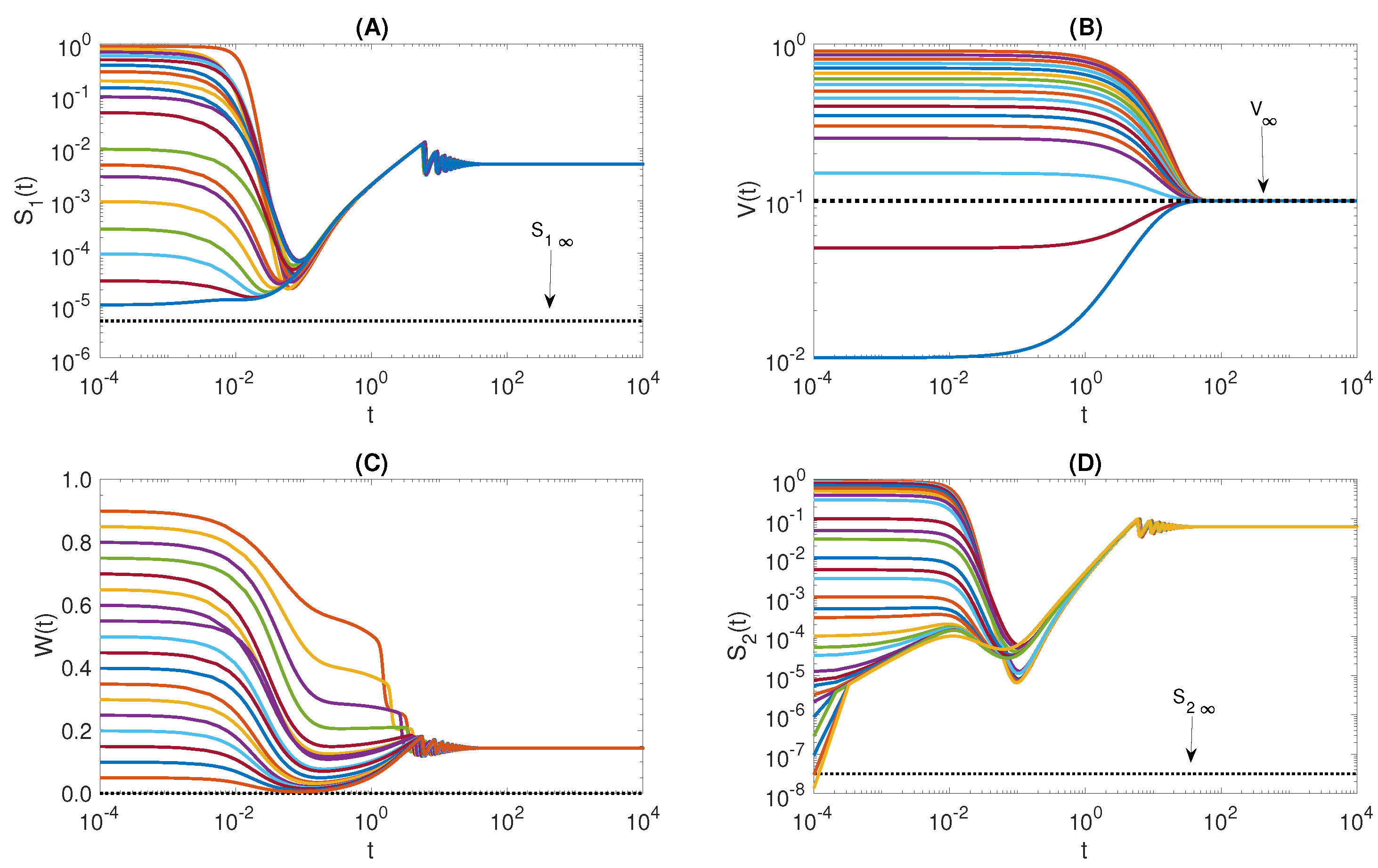

Figure 4 shows the time-dependent solution for the non-infected components

and

with various positive initial conditions and with values of parameters as in

Table 3 except

that has been chosen to restrict the reproduction number

. The simulations show that

and

. Similar results have been obtained by solving with the same parameter values except for

which is chosen such that

, see

Figure 5.

Now, we examine the uniform persistence of the disease when

using the theory of uniform persistence [

36]. To this end, we let

be a continuous semiflow corresponding system (

1) defined on the feasible state space

. We define the persistence function

Now, we choose

and define the sets

where

is the invariant extinction space of

corresponding to

(i.e.,

is the collection of states in the absence of the disease). From proposition 1, the set

is positively invariant which implies that

and

are positively invariant and

is relatively closed under the semiflow

. Now, we let

denote the

-limit set of a point in

, where

and use the results shown in [

36] (Chapter 8) to examine the set

. Clearly, all solutions starting in the extinction space

converge to the infection-free equilibrium. Therefore,

.

In the following, we prove the weak

-persistence using Theorem 8.17 in [

36]. Using the terminology shown in [

36], we let

. Therefore,

where

is isolated (due to unstability of

when

, Proposition 2), compact, invariant and acyclic. We still have to prove that

is weakly

-repelling. Then, by results from Chapter 8 of [

36], we obtain the weak persistence.

Assume, by contradiction, that

is not weakly

-repelling, i.e., there exists a solution of model (

1) which converges to

and

. Therefore, for any

, and for sufficiently large

t, we obtain

Thus, for sufficiently large

t, we can estimate

as follows:

which is positive if

is sufficiently small as follows from

. This contradicts

. Hence,

is weakly

-repelling and from Theorem 8.17 in [

36], our flow

is uniformly weakly

-persistent.

Proposition 1 implies that the solutions of model (

1) are ultimately bounded. Then,

is point-dissipative and compact on

[

37]. In view of Theorem 3.4.8 given by [

38],

has a compact global attractor in

.

To prove the uniform (strong) persistence, we apply Theorem 4.5 shown in [

36]. Clearly, model (

1) generates a continuous flow on

and the subspaces

,

and

are invariant. Moreover, the existence of a compact attractor in

is proved. Therefore, all conditions of Theorem 4.5 in [

36] are satisfied from which we conclude that

is uniformly

-persistent (i.e., the disease

is uniformly persistent). Hence, we summarize the above results in the following proposition.

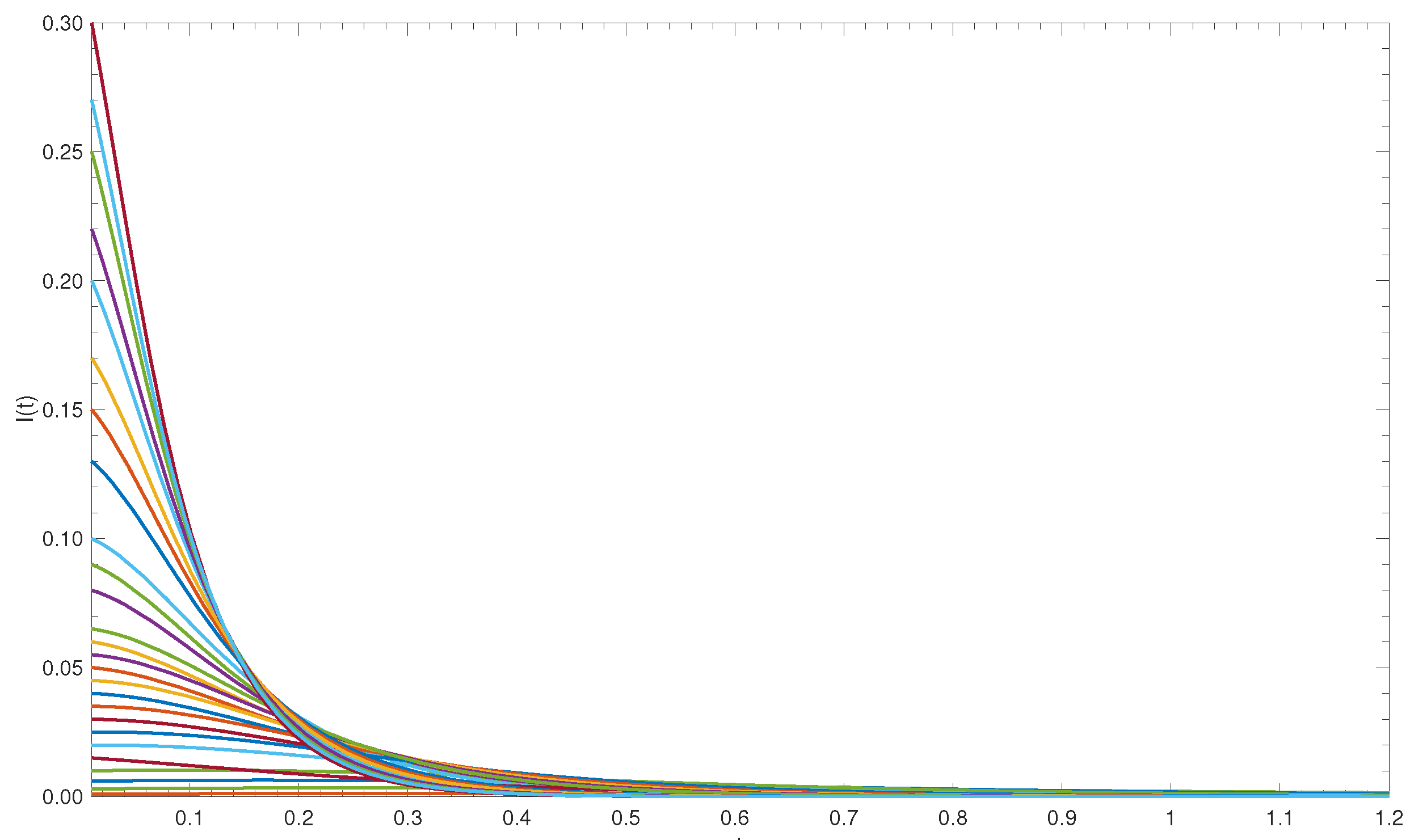

Proposition 7. If , then the semiflow Φ is uniformly ρ-persistent, i.e., the disease is uniformly persistent in the population. More precisely, there exists an such that for any positive solution of model (1), . Time-series analysis for the proportion of infected individuals, with parameter values as in

Table 3, is shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6A shows the solution with the Y-axis being in a linear scale, while

Figure 6B shows the same trajectories in the logarithmic scale to better present the behavior of the solutions. It is clear that when

, the value of

is bigger than some

.

5. Controllability of the Infection

The above analysis showed that model (

1) exhibits only forward bifurcation and that no endemic equilibrium exists for values of

. Therefore, the controllability of the infection is guaranteed by applying control measures aiming to reduce the value of

to slightly below one. This is equivalent to having

, where

is the critical contact rate separating the regions of disappearance and persistence of pertussis infection and the proportion

is the proportion of life spent in the waning immunity state, while the proportion

is the proportion of life spent in the vaccinated state.

Routine vaccination is considered one of the most important strategies applied to protect populations from the negative impact of infectious diseases and is represented here by the dimensionless parameter

. A value of

means that none of the new births receive the vaccine, while

represents that all newborns get the shots. However, the

represents here the critical contact rate (in the presence of vaccination) that separates between non-existence and existence of infection and is a function of

p and some other model parameters. Of great interest is the dependence of

on

p. If

as

, then the infection is always controllable with strategies based on routine vaccination only [

8,

12]. However, if

approaches a finite asymptote (say,

) as

, then the infection is controllable only if control strategies (other than vaccination) are applied to reduce

to slightly below

, in addition to vaccinating a proportion

, where

is the critical vaccination coverage required to eliminate pertussis infection. In fact, the value of

is

and represents the reinfection contact rate [

8,

12]. It is noteworthy that the critical vaccination coverage

decreases with the increase in either or both of

and

and increases with the increase in the rescaling parameter

r. This means that ignoring the difference between susceptibilities of primary and secondary susceptible individuals overestimates the value of

. However, the reinfection contact rate

increases with the increase in either of the proportions

and

and with the decline in

r. The critical contact rate

is depicted as a function of the vaccination coverage

p for different values of the proportions

and the scaling parameter

r in

Figure 7A–C, respectively. The figure shows that the region of infection’s controllability enlarges with the increase in the proportions

and

and the decrease in the relative susceptibility parameter

r. In summary, we state the following proposition.

Proposition 8. If the successful contact rate β is less than the reinfection contact rate , then the infection is eliminated by vaccinating a proportion of the newborns, while if , then the infection cannot be eliminated with a strategy based on vaccination solely, but other control strategies aiming at reducing β to slightly below should be applied, in addition to vaccinating a proportion . Moreover, the possibility to control the infection enlarges with the increase in the proportion of life spent in the immunization and waning states and the decrease in the relative susceptibility of secondary (with respect to primary) susceptible individuals.

6. Impact of Waning and Natural Immune Boosting on Disease Outcomes

As explained in

Section 2, the immunity acquired either due to vaccination or due to experiencing the infection declines and the individual’s status becomes waned. In model (

1), the two parameters

and

determine the duration of acquired immunity and progression to become secondary susceptible, respectively. However, the natural immunity boosting is represented by the rescaling parameter

(times the force of infection

), where a value of

means that the natural boosting immunity is completely ignored. The parameter

g does not appear explicitly in the formula of the reproduction number

. However, it appears in the coefficients of the characteristic epidemiological Equation (

15) and, therefore, affects the endemic prevalence of the infection.

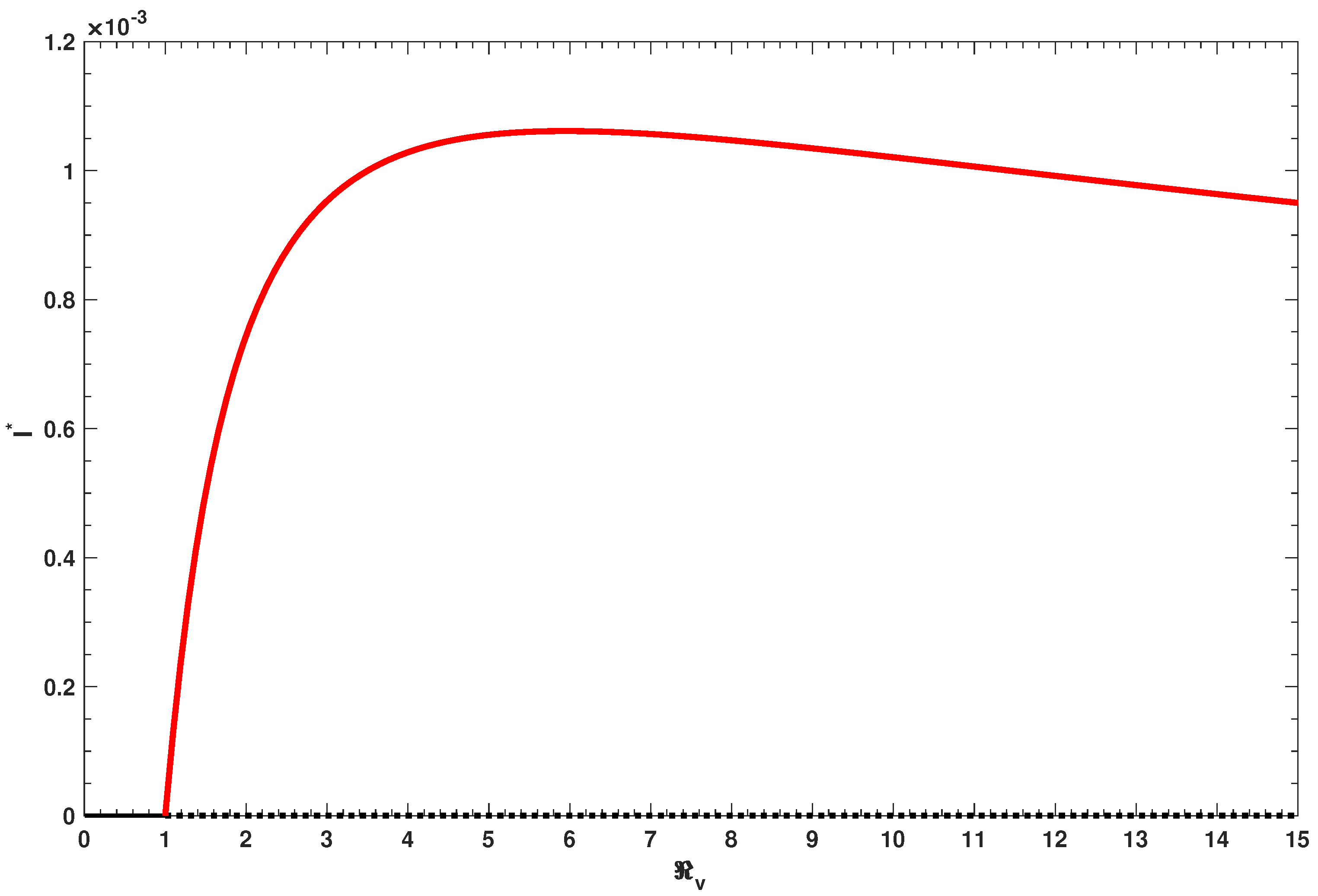

In the absence of natural booster immunity (i.e.,

), the Equation (

15) reduces from cubic to quadratic equation with simpler coefficients than in (16). In this case, the proportion of the infected population in the endemic situation reads

where

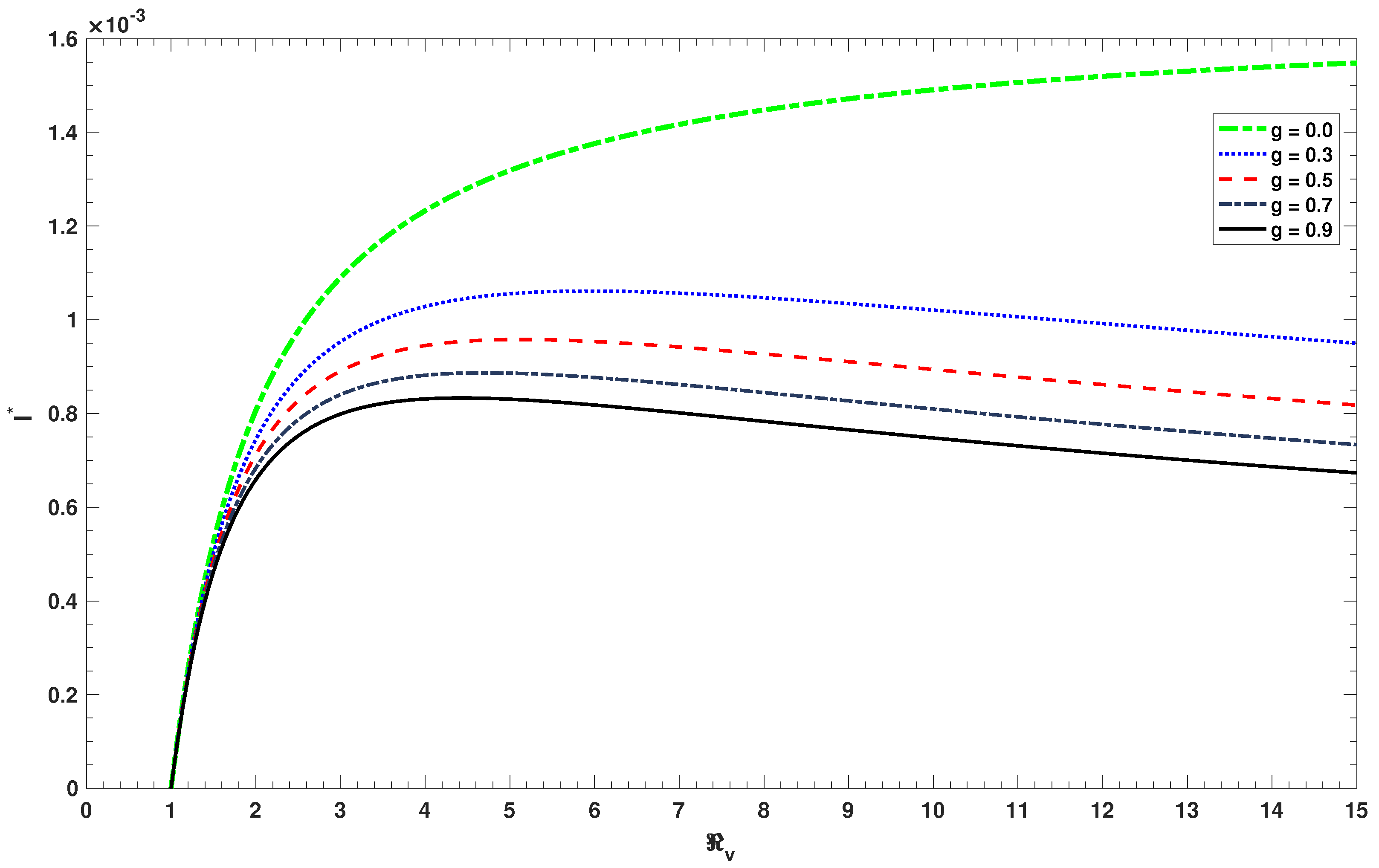

The endemic prevalence of the infection

is depicted as a function of the control reproduction number

for different values of the natural booster immunity parameter

g and is presented in

Figure 8. The figure shows that the proportion

increases monotonically with the increase in

, in the absence of natural booster immunity (i.e., if

). However, in the presence of natural booster immunity (i.e., if

), the endemic prevalence

increases monotonically in

till reaching a maximum at some value of

and then starts to decrease with the increase in

. This result could be read in a reverse way as follows. In the presence of natural booster immunity, reducing the control reproduction number

increases the endemic prevalence of infection

till reaching a maximum level, and a further reduction in the value of

to one (or slightly below one) forces a reduction in the endemic prevalence of infection

to zero. The figure also shows that the endemic prevalence of the infection

decreases with the increase in the natural booster immunity parameter

g. Therefore, ignoring the natural booster immunity overestimates the endemic prevalence of infection and, in consequence, overestimates the effort needed to eliminate the infection.

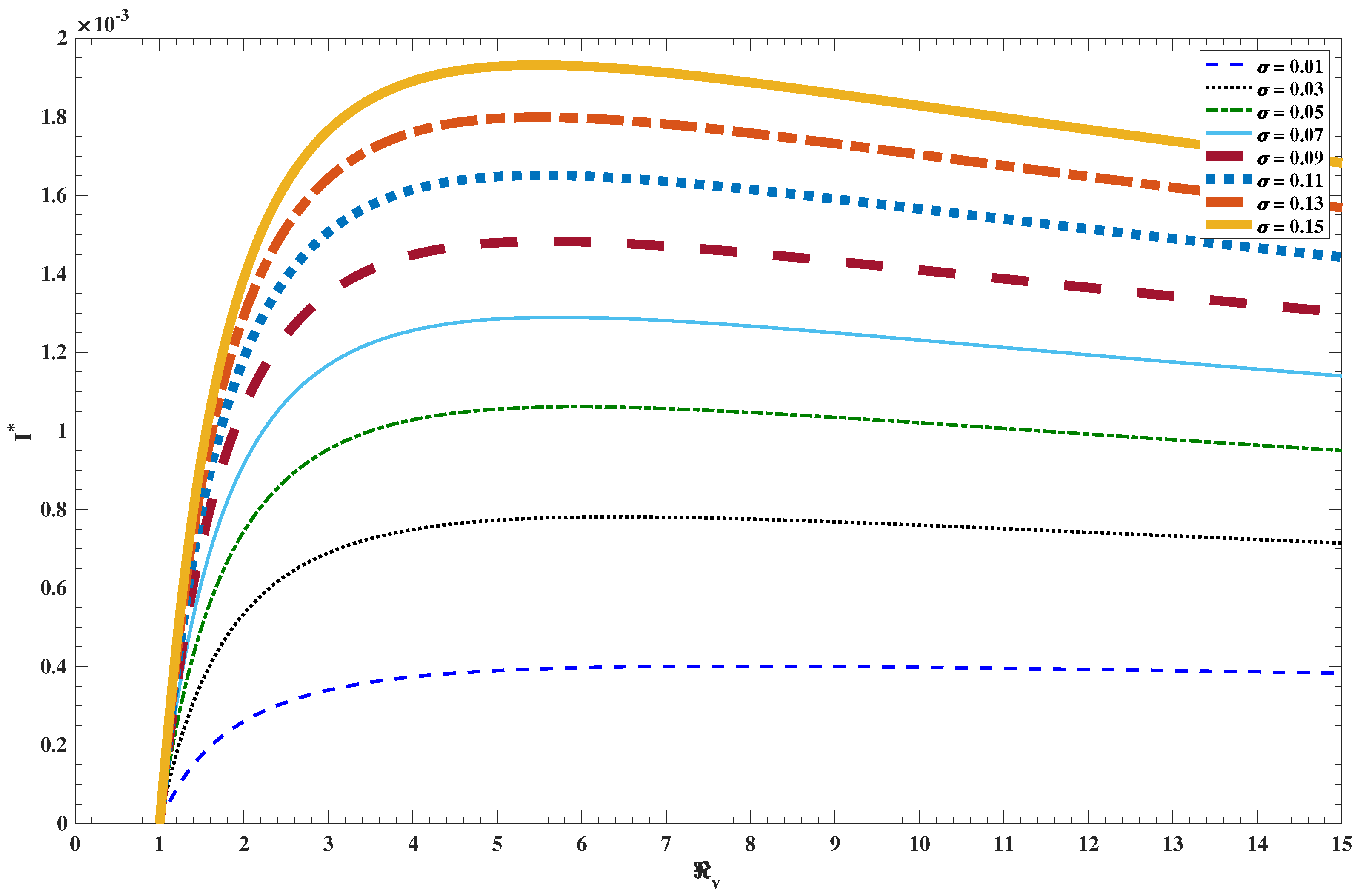

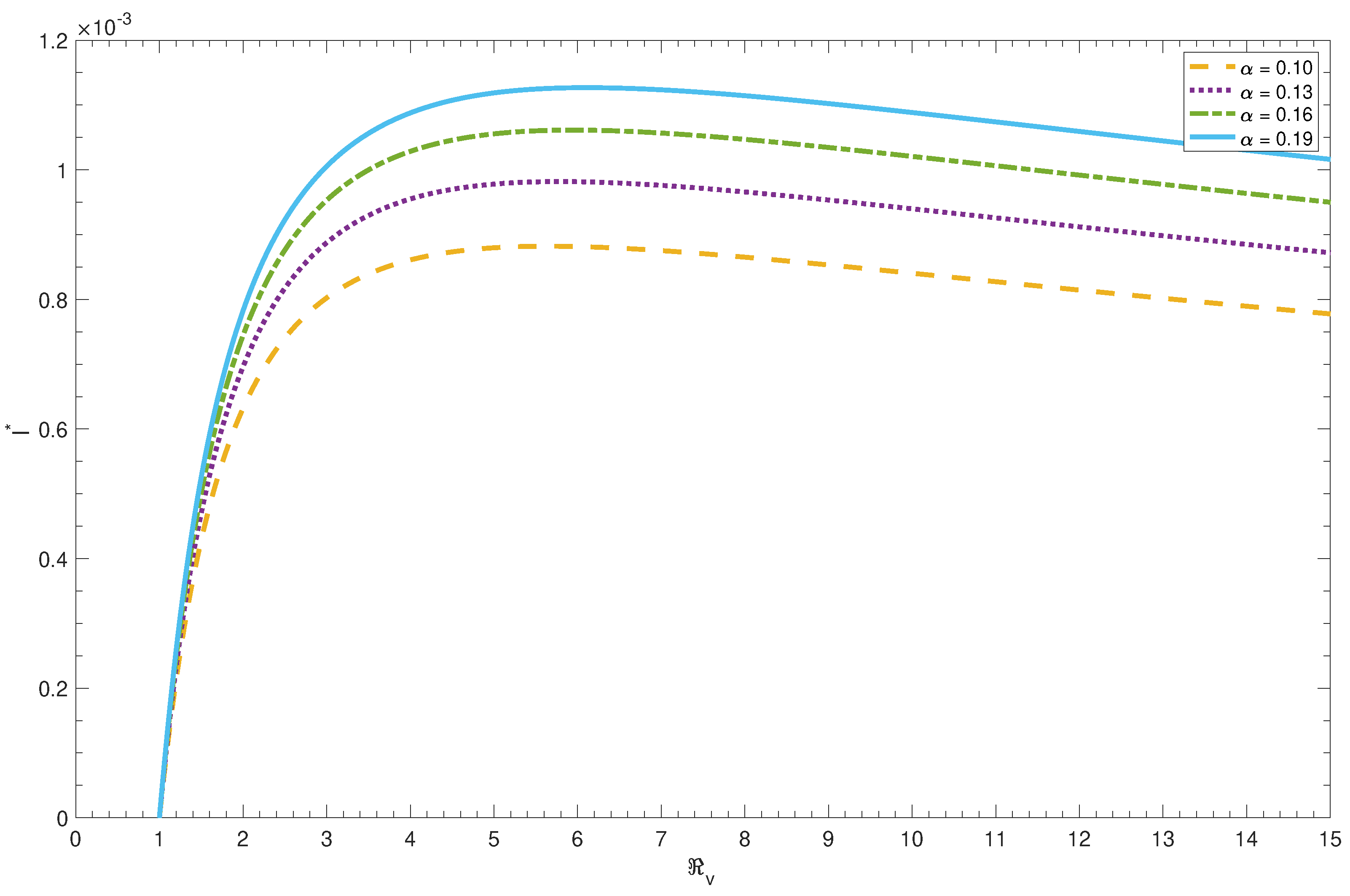

The waning of immunity and progression of secondary susceptible parameters

and

appear in both disease outcomes (i.e.,

and

). It is worth noting that

increases with the increase in

and/or

. Moreover, numerical simulations show that

increases with the increase in either

or both, see

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. In other words, any decline in the period of immunity acquired by either vaccination or naturally experiencing pertussis infection increases the reproduction number and the endemic prevalence of infection, and therefore, increases the effort needed to eliminate pertussis infection. Moreover, the endemic prevalence of pertussis infection rises with the increase in the progression rate of secondary susceptible individuals.

It is clear from (

21) and (

23) that increasing either or both of

and

decreases the reinfection contact rate

and increases the critical vaccination coverage required to eliminate the infection

, which in turn increases the effort needed to eliminate the infection.

7. Summary, Conclusions and Future Work

Mathematical models have gained the attention of the scientific community as they help to understand the dynamic behavior of the phenomenon in concern [

1,

2]. The last few decades showed much interest in modeling infectious diseases and, in particular, the attempt to predict the most effective factors in containing an infectious disease [

4,

5,

39]. Routine vaccination is one of the main strategies used to protect a population from infectious diseases. However, the immunity acquired either due to receiving the vaccine shots or due to naturally experiencing the infection wanes with time [

14,

15,

40]. It is evident that re-exposure to Bordetella pertussis (after waning immunity) may trigger an immune response to protect against the infection while also boosting one’s immunity [

20,

41,

42]. The effect of the interplay between waning and boosting of the infection on the overall dynamics is less understood. Therefore, a mathematical model of type SIRS (susceptible-infected-recovered-susceptible), with imperfect vaccination V and waning of immunity W, for pertussis infection that is spread in a homogeneously and symmetrically fully mixed population has been introduced and analyzed. The model differentiates between the susceptibility of individuals who acquire the infection for the first time and that of individuals who experienced it at least once before. Moreover, it considers the booster of immunity due to natural re-exposure to the infection after the waning of the acquired immunity.

The model has been mathematically analyzed, where the equilibrium and stability analyses have been studied. The model has a pertussis-free equilibrium that is shown to be locally and globally asymptotically stable if and only if the control reproduction number is less than one. Moreover, the model has an endemic equilibrium that is proved to be unique and to exist if and only if . Moreover, the uniform persistence of all solutions has been proven.

The possibility to eliminate pertussis infection with a strategy based on vaccinating a proportion p of the newborns has been studied. The analysis shows that a reinfection contact rate level (above which pertussis cannot be eliminated with active vaccination) does exist and control strategies other than vaccination should be applied to reduce the successful contact rate to slightly below so that vaccinating a proportion of the newborns ensures effective control of pertussis infection. The analysis shows further that any decrease in the relative susceptibility r of secondary (with respect to primary) susceptible individuals and/or increase in either or both of the proportion of life spent in the vaccination state and in the waned-immunity state enlarges the region of infection’s controllability, which in turn increases the possibility to eliminate the infection and reduces the effort required to eliminate it (through reducing the critical vaccination coverage level ). The results show that the reinfection contact rate increases with the decrease in r. Thus, ignoring the differential susceptibility between primary and secondary susceptible individuals underestimates the reinfection contact rate threshold and overestimates the minimum vaccination coverage required to eliminate the infection.

The effect of waning immunity and natural immune boosting on disease outcomes has been studied. The analysis shows that:

The higher the natural boosting immunity is, the lower the endemic prevalence of infection is. In other words, ignoring the natural boosting of immunity overestimates the endemic prevalence of infection;

The faster the progression of secondary susceptible individuals is, the higher the endemic prevalence of infection is;

The shorter the period of immunity acquired by either vaccination or experiencing natural infection, the higher the reproduction number and the endemic prevalence of infection, and therefore, the higher the effort needed to eliminate the infection is.

The dynamical behavior and the current results could be affected by taking further extensions, that are considered in forthcoming work, to include the differential infectivity and transmissibility of infected individuals who caught the infection for the first time and those who experienced it at least once before and are capable of transmitting it, taking into account real data.