1. Introduction

For notation and graph theory terminology we, in general, follow [

1]. Specifically, let

be a graph with vertex set

and edge set

. If

A and

B are disjoint sets of vertices of

G, then we denote by

the set of edges in

G joining a vertex in

A with a vertex in

B. For a vertex

v of

G, its

neighborhood, denoted by

, is the set of all vertices adjacent to

v, and the cardinality of

, denoted by

, is called the

degree of

v. The

closed neighborhood of

v, denoted by

, is the set

. In general, for a subset

of vertices, the

neighborhood of

X, denoted by

, is defined to be

, and the

closed neighborhood of

X, denoted by

, is the set

. A vertex of degree 0 is said to be

isolated in

G, while a vertex of degree one in

G is called a

leaf of

G. The set of all leaves of

G is denoted by

. We define a

pendant edge of a graph to be an edge incident with a leaf. The

corona of graphs

H and

F is a graph

resulting from the disjoint union of

H and

copies of

F in which each vertex

v of

H is adjacent to all vertices of the copy of

F corresponding to

v. The

corona, in particular, is the graph obtained from

H by adding exactly one pendant edge to each vertex of

H. A graph

G is said to be a

corona if

G is the corona

of some graph

H. It is obvious that a corona is a graph in which each vertex is a leaf or it is adjacent to exactly one leaf.

We denote the path, cycle, and complete graph on n vertices by , , and , respectively. The complete bipartite graph with one partite set of size n and the other of size m is denoted by . A star is the tree for some . For , a double star is the tree with exactly two vertices that are not leaves, one of which has k leaf neighbors and the other l leaf neighbors.

A vertex v is called a simplicial vertex of G if is a complete graph, while it is a cut vertex if is disconnected. A block of a graph G is a maximal connected subgraph of G without its own cut vertices. We say that G is a block graph if every block of G is a complete graph (equivalently, every vertex of G is a simplicial or a cut vertex). A block of a block graph G is called a simplex if it contains at least one simplicial vertex of G, while it is an end block if it contains at most one cut vertex of G.

A subset

D of

is called a

dominating set of

G if every vertex belonging to

is adjacent to at least one vertex in

D. A subset

I of

is said to be

independent if no two vertices belonging to

I are adjacent in

G. The cardinality of a largest (i.e., maximum) independent set of

G, denoted by

, is called the

independence number of

G. Every largest independent set of a graph is called an

-set of the graph. The

independent domination number of

G, denoted by

, is the cardinality of a smallest independent dominating set of

G (or equivalently, the cardinality of a minimum maximal independent set of vertices in

G). The study of independent sets in graphs was begun by Berge [

2,

3] and Ore [

4]. In 2013 Goddard and Henning published an article [

5] that summarized results on independence domination in graphs. It is obvious that

for any graph

G. A graph

G is a

well-covered graph if

. Equivalently,

G is well-covered if every maximal independent set of

G is a maximum independent set of

G. The concept of well-covered graphs was introduced by Plummer [

6] and extensively studied in many papers. We refer the reader to the excellent (but already old) survey on well-covered graphs by Plummer [

7].

Now, between the integers

and

, we insert another integer concerning the existence and cardinality of independent sets in

G. Formally, we introduce the concept of the

common independence number of a graph

G, denoted by

, as the greatest integer

r such that every vertex of

G belongs to some independent subset

X of

with

. Thus, the common independence number of a graph

G refers to numbers of mutually independent vertices of

G, and it emphasizes the notion of the individual independence of a vertex of

G from other vertices of

G. The common independence number

of

G is the limit of symmetry in

G with respect to the fact that each vertex of

G belongs to an independent set of cardinality

in

G, and there are vertices in

G that do not belong to any larger independent set in G. For possible applications of the three parameters

,

, and

we refer the reader to the newest survey by Majeed and Rauf [

8] on different applications of graph theory in computer science and social networks. It follows immediately from the above definitions (see also Proposition 1) that

for any graph

G. In the following section, we present the first properties of the common independence number. Then, in the next two sections, we characterize the family of trees

T for which

, and the family of block graphs

G such that

, respectively. (We remark that the family of well-covered graphs is a proper subfamily of each of the previously mentioned families.)

2. Preliminaries

For our studies of the common independence number of a graph, we begin from straightforward propositions and simple examples.

Proposition 1. For every graph G we have .

Proof. Certainly, we have , since, as it follows from the definition of , every independent set of vertices of G has at most vertices. On the other hand, for every , let be any maximal independent subset of that contains v. The maximality of implies that . Consequently, . □

Proposition 2. If G is a graph, then if and only if .

Proof. If , then G has a vertex v that is adjacent to every other vertex of G. This implies that is the only independent set in G that contains v. Hence . On the other hand, if , then by Proposition 1. □

Proposition 3. If G is a non-empty graph, then and , assuming that if H is an empty graph, that is, a graph without vertices.

Proof. Both equalities are obvious if G has a vertex v such that (in this case is an empty graph). Assume now is non-empty for every . Let be a largest independent set in . Then is a largest independent set in G that contains v. From this and from the definition of the common independence number it follows that . Now let be a minimum independent dominating set in . Then is a maximal independent set in G, which implies . Assume now D is a minimum independent dominating set in G and let . Then is a minimum independent dominating set in and . Hence, . □

To better recognize connections between the independent domination number

, the common independence number

, and the independence number

, we begin with simple examples. It is obvious that

for every positive integer

n. Similarly, if

m and

n are positive integers and

, then

. It is no problem to observe that

,

, and

. Consequently,

if

and

. On the other hand we have

if

. Let

be a graph obtained from the corona

by inserting a new vertex into each non-pendant edge of

, see

Figure 1. Now it is easy to see that

,

,

, and

if

. Similarly, if

denotes a graph obtained from the double star

by inserting a new vertex into its only non-pendant edge, then it is obvious that

,

, and

. From these examples it follows that the differences between numbers

,

, and

can be arbitrarily large.

The aim of the next theorem is to show for which positive integers m, n, and p satisfying the inequalities there exists a graph G such that , , and . This theorem again shows that the difference between the independence number and the common independence number as well as the difference between the common independence number and the independent domination number of a graph can be arbitrarily large.

Theorem 1. For integers m, n, and p there exists a graph G with , , and if and only if or .

Proof. Since the necessity is obvious from Propositions 1 and 2, we need only provide constructions to establish sufficiency.

If , then for we have and . Thus assume that , and let , . Let , , , and be disjoint totally disconnected graphs of order s, , , and t, respectively. Now, let G be a new graph constructed from the union by adding all possible edges between the vertices of and , . It is easy to observe that the sets , , and of cardinality m, n, and p, respectively, are the only maximal independent sets of G. Consequently, and . In addition, because every vertex of G belongs to an independent set of cardinality at least n and no vertex in belongs to an independent set of cardinality greater than n, we have . This completes the proof. □

3. Graphs with

In this section we consider graphs

G for which

; in particular we provide a constructive characterization of block graphs

G for which

. It follows from the next proposition that such graphs form the class of the

-

excellent graphs, that is, the class of graphs

G in which every vertex belongs to some largest independent set of

G. Thus, we are interested in characterizations of the

-excellent graphs. The

-excellent trees were already studied in [

9,

10]. We extend their characterizations to the

-excellent block graphs, and we present some additional properties of the

-excellent trees.

Proposition 4. For a graph G is if and only if G is an α-excellent graph.

Proof. Assume that G is an -excellent graph. Then, by definition, every vertex of G belongs to an independent set of cardinality in G, and, therefore, . From this and from Proposition 1 it follows that .

On the other hand, by definition, every vertex of G belongs to an independent set of cardinality (at least) . Thus, if , then every vertex of G belongs to an independent set of cardinality , and G is -excellent. □

In order to state and prove our characterization of the -excellent block graphs, we present additional definitions and some preliminary results that we will need while proving the next two theorems. Let be a complete graph of order with vertex set . If are positive integers, then by we denote a graph obtained from the disjoint union of the complete graphs by joining each vertex of with each vertex of for . The graph is said to be a general corona of and the subgraph of induced by the vertices is called the body of . It is obvious that has the property stated in the next observation.

Observation 1. A general corona is a well-covered graph, and . In addition, is a tree if and only if either or and .

Let

be the family of graphs that: (1) contains every complete graph of order at least 2; and (2) is closed under attaching general coronas, that is, if a graph

belongs to

and

is a general corona, then to

belongs every graph obtained from the disjoint union

by adding

n edges that join one vertex of

with the vertices forming the body of

H. By

we denote the family (defined in [

9]) of all trees belonging to

. Thus,

belongs to

, and, if a graph

belongs to

and

K is a complete graph of order 2, then to

belongs every graph obtained from the disjoint union

by adding exactly one edge that joins a vertex of

with a vertex of

K.

It is clear from the above definition that every graph belonging to the family

is a block graph.

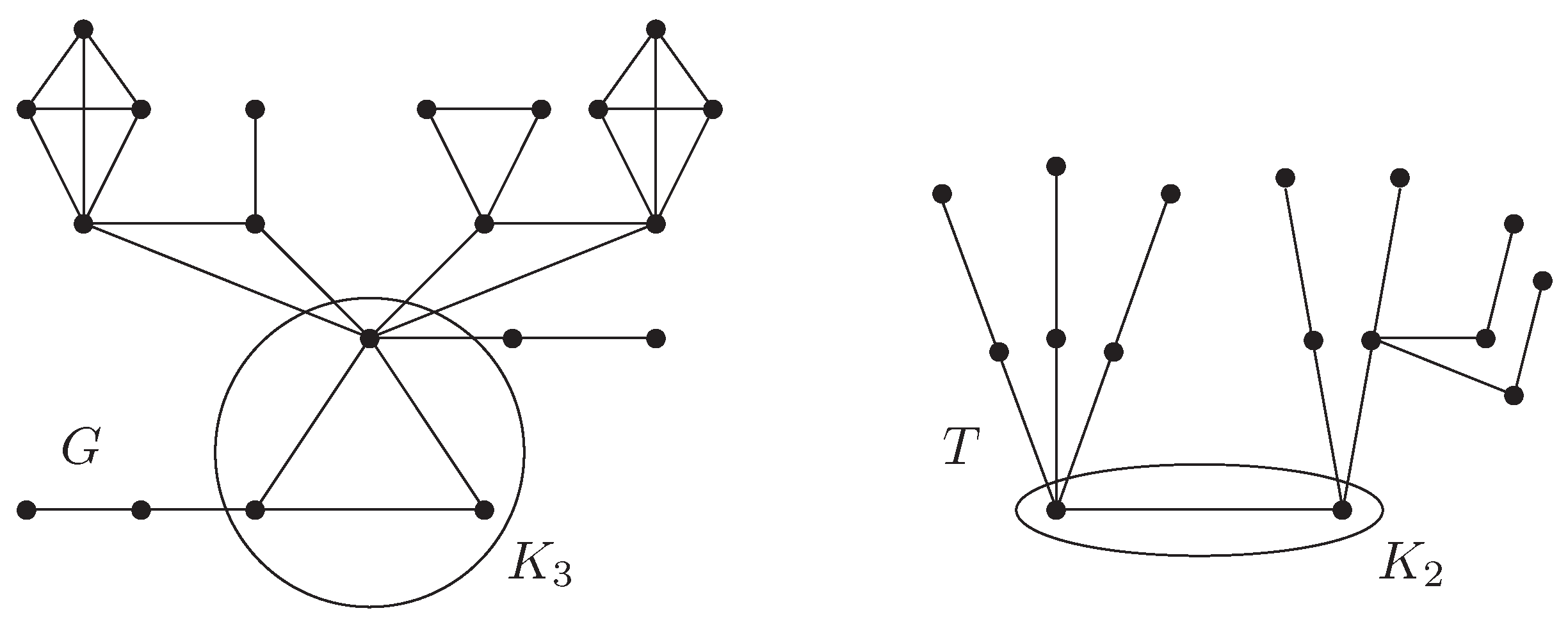

Figure 2 shows a block graph

G belonging to

and a tree

T that belongs to the subfamily

of

.

Proposition 5. Let be a connected graph of order at least 2. If G is a graph obtained from by attaching a general corona to a single vertex of , then . In addition, G is an α-excellent graph if and only if is an α-excellent graph.

Proof. Assume that is the vertex set of the body of , and assume that H is attached to a vertex v of . Let be a set of simplicial vertices of H, where each is adjacent to (). It is apparent that if I is an -set of , then is an independent set of G, and therefore . Thus assume that J is an -set of G. Then and are independent sets of and H, respectively. In addition it follows from Observation 1 that is an -set of H. Hence , and so .

It remains to prove that G is -excellent if and only if is -excellent. Assume first that G is -excellent. Let x be a vertex of , and let be an -set of G that contains x. Since has at most n vertices in H (by Observation 1), and has at least vertices in and . This implies that is an -excellent graph.

Now assume that is -excellent. Let y be a vertex of G. If y belongs to , and if is an -set of containing y, then is an -set of G containing y. Thus assume that . If y is a simplicial vertex of G belonging to H, then without loss of generality we may assume that . Then is an -set of G containing y, where I is any -set of . If y is in a body of H, say (for some ), then is an -set of G containing y, where u is any neighbor of v in and an -set of containing u. □

We are now in position to prove the main result of this section, a constructive characterization of the -excellent block graphs.

Theorem 2. Let G be a block graph of order . Then the following statements are equivalent:

- (a)

.

- (b)

G is α-excellent graph.

- (c)

.

Proof. The implication is obvious from Proposition 5. The statements (b) and (c) are equivalent by Proposition 4. Thus it suffices to prove the implication .

Assume that G is a block graph of order at least 2 with blocks and . We use induction on n to show that . If , then G is a complete graph, say (), and certainly . Let G be a block graph with blocks and assume that every block graph belongs to if and has blocks, where . We first establish the following claim. □

Claim 1.

All simplices of G are pairwise vertex-disjoint.

Proof. Suppose that and are two distinct simplices of G containing a common vertex v. Let be a largest independent set of G that contains v. Then . On the other hand, let x and y be two simplicial vertices belonging to and , respectively. Then, since x is not adjacent to y and neither x nor y is adjacent to any vertex in , the set is an independent set of G and , a contradiction which completes the proof of our claim. □

Claim 1 implies that the diameter d of G is greater than 2. Let be a longest path without chords in G. Let be that block of G which contains and , . The choice of P and Claim 1 imply that the blocks are distinct, are cut vertices, while and are simplicial vertices belonging to the end blocks and , respectively. Without loss of generality we assume that . (We remark that possibly .) Since is a simplex and the blocks and share a vertex, is not a simplex (by Claim 1), and therefore each of the vertices is a cut vertex. Let be blocks distinct from containing the vertices , respectively. The choice of P implies that are end blocks in G and they are unique (by Claim 1). Let H denote the subgraph of G induced by the vertices belonging to the blocks . It is obvious that H is a general corona , where , . Let denote the subgraph of G. Since G can be obtained from by (re)attaching the general corona H to the vertex in , it follows from the second part of Proposition 5 that . Thus, since has blocks, where , belongs to by the inductive hypothesis. Consequently, G belongs to (since G can be obtained from by attaching a general corona to a vertex in ).

In the following theorem (which partially follows from Theorem 2) we prove the equivalent properties that characterize the trees T with , that is, the -excellent trees.

Theorem 3. Let T be a tree of order . Then the following statements are equivalent:

- (a)

.

- (b)

.

- (c)

T has a perfect matching.

- (d)

T has a spanning forest in which every component is the corona of a tree.

- (e)

T is an α-excellent tree.

- (f)

.

Proof. The equivalence of (a) and (b) was proved in [

9]. The statements (b), (e), and (f) are equivalent by Theorem 2. In [

10] it was proved that (c) and (e) are equivalent. The statements (c) and (d) are equivalent: If

M is a perfect matching in

T, then the subgraphs of

T generated by single edges belonging to

M form the desired forest (with the smallest number of edges). On the other hand if

T has a spanning forest

F in which every component is the corona of a tree, then the set of all pendant edges of

F forms a perfect matching of

T. This completes the proof. □

4. Graphs with

In this section we are interested in recognizing the structure of trees in which the independence number

i and the common independence number

are equal. In order to do this, we recall that a graph

G is a well-covered graph if every maximal independent set of vertices of

G is a largest independent set of

G. Equivalently,

G is well-covered if and only if

. We begin with some basic observations on well-covered graphs. The first one follows directly from the definition of a well-covered graph. The second one—the characterization of well-covered trees—was proved by Ravindra [

11].

Remark 1. A graph G is well-covered if and only if every set of independent vertices of G is a subset of a largest independent set of G.

Lemma 1 ([

11]).

A tree T is well-covered if and only if it is or it is a corona of a tree. In the next lemma we present a general property of the graphs G for which .

Lemma 2. If G is a graph in which , then either or there is a vertex z in G such that is a well-covered graph and .

Proof. Assume that and suppose that is a non-well-covered graph for every . Then for every , and consequently by Proposition 3 we have , a contradiction. From this contradiction and from the fact that for every it follows that for some vertex v of G, which in turn implies that is a well-covered graph. We now claim that there is a vertex z in G such that . To observe this, let z be a vertex such that . Then, since , we also have and this implies our claim. □

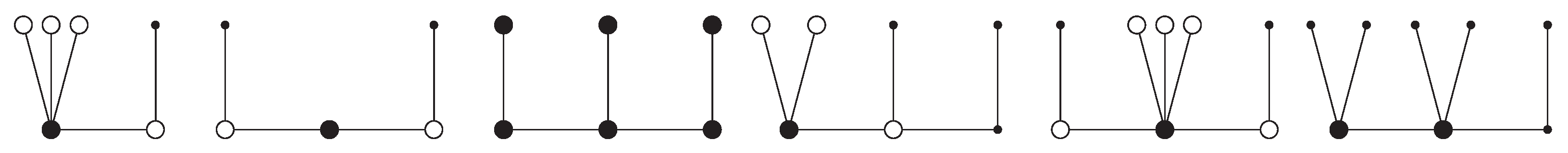

Remark 2. Graphs in Figure 3 illustrate that if G is a graph in which , then it follows from Lemma 2 that G has at least one vertex z (the white and solid black vertices) such that is a well-covered graph, but only for some of them (the solid black vertices) the equalities hold. We are now in position to present our characterization of trees for which the independence number i and the common independence number are equal.

Theorem 4. If T is a tree, then if and only if at least one of the following conditions is fulfilled:

- (1)

T is a star;

- (2)

T is the corona of a tree;

- (3)

T has a vertex z such that

- (a)

is a well-covered forest, and

- (b)

if , , where is the set of leaves of trees of order at least 4 in .

Proof. Assume that

T is a tree and

. It is obvious that if

, then

T is a star,

, where

n is a non-negative integer. Thus assume that

and

T is not a corona graph. Then it follows from Lemma 2 that

T has a vertex

z such that

is a well-covered graph and

. Certainly,

is a well-covered forest, and, consequently, each component of

is the corona of a tree (that is, its pendant edges form a perfect matching, see [

7,

11]) or an isolated vertex.

Let

U and

V denote the set

and

, respectively. We divide the set

V into two sets

and

, where

and

. Let

F denote the graph

, and let

be the set of all components of

F. Let

,

, and

be the subgraphs of

F, where

,

,

. By

,

, and

we denote the sets

,

, and

, respectively.

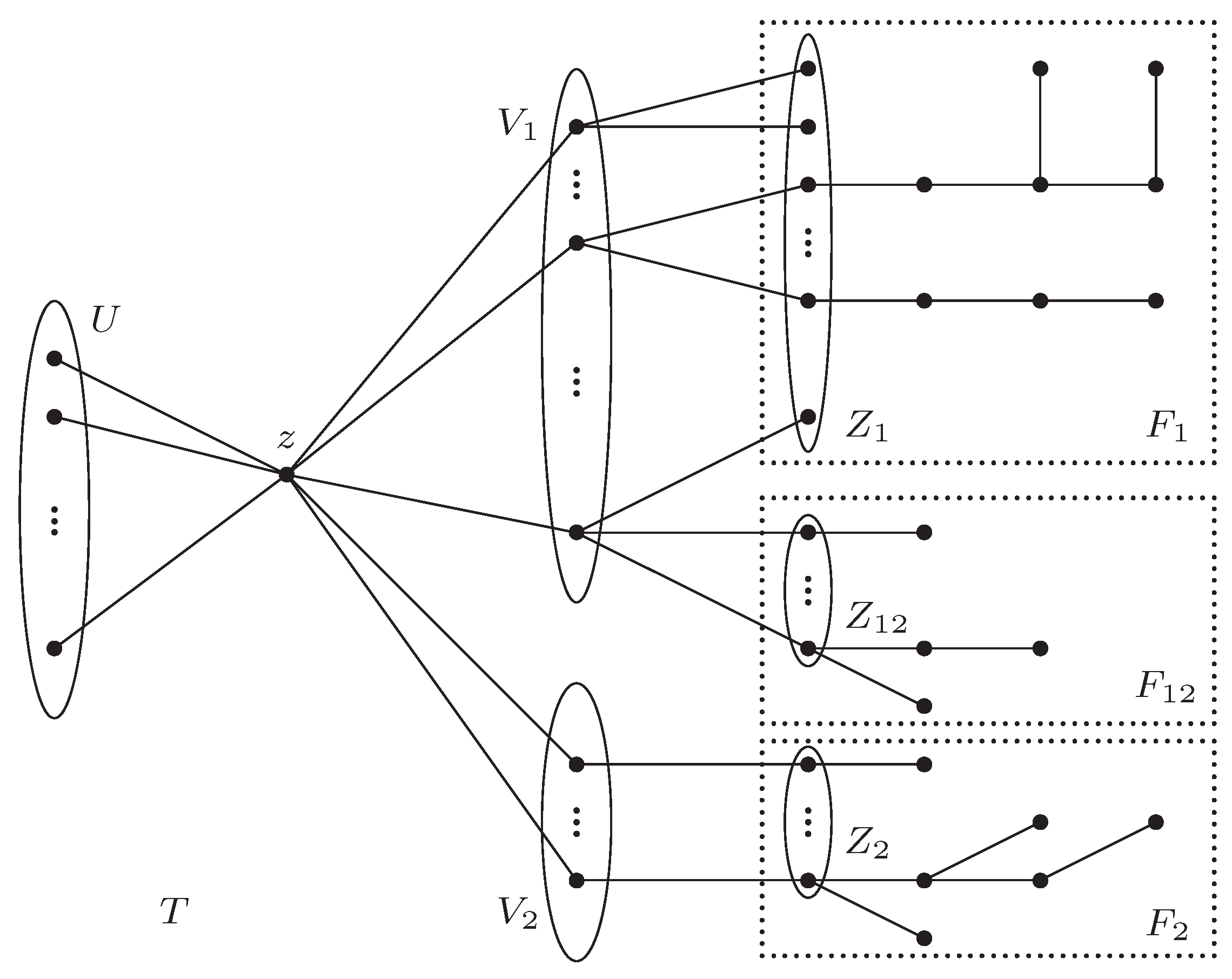

Figure 4 shows a tree

T, the subsets

U,

,

,

,

,

, and the subgraphs

,

, and

of the well-covered forest

.

Assume that . Then the set is non-empty. Now, since if and if , we have , and we shall prove that . Suppose to the contrary that . Let I be a maximal independent set of F. Then is a maximal independent set of T and therefore we have .

Now let , , and be sets such that is a maximal independent set of that contains , is a maximal independent set of that contains , and is a maximal independent set of that contains , respectively. The existence of such sets , , and follows from Remark 1. Certainly, the set is a largest independent set of F. From the choice of , , and it is easy to observe that the set is a maximal independent set of T. Thus, since , we have , a contradiction which proves the desired inequality .

Assume that T is a tree which has one of the properties (1), (2), and (3). It is evident that if T is a star or a corona graph, then . Thus assume that T is neither a star nor a corona graph, and T has a vertex z such that the subgraph is a well-covered forest. Assume that . We shall prove that .

It is obvious that if I is a maximal independent set of F, then is a maximal independent set of T and therefore . On the other hand, if we assume that every maximal independent set of T has at least vertices, then , and, consequently, . This implies that as . Hence, to prove that , it suffices to show that every maximal independent set of T has at least vertices. (In fact, it suffices to show that every smallest maximal independent set of T has at least vertices.) For this, let U, V, , , , , , F, , , and be the sets and graphs defined in the previous part of our proof.

Therefore assume that J is a maximal independent set of T. If , then the maximality of J implies that the sets and are non-empty, each of them is independent, and . In addition, the maximality of J in T implies that for every . We shall prove that is a maximal independent set in F, that is, we shall prove that for every . If , then and therefore and, consequently, . If , then and, thus, . This proves that is a maximal independent set in the well-covered graph F. Thus and finally . It remains to prove that if . Thus assume that J is a maximal independent set of T, where . In this case and . We distinguish two cases: , .

Case 1. Assume first that . In this case the sets , , and are empty, while and are non-empty (as T is not a star). From the maximality of J it follows that , where (by our assumption). Certainly, is an independent set in . We shall prove that is a maximal independent set of . The maximality of J implies that for every . It remains to prove that for every . If , then and therefore . It remains to prove that if . Assume that . Then either x is a non-leaf in or x belongs to a component of order 2 in , and, since is a well-covered forest, every component of is the corona of a tree, x is adjacent to exactly one leaf in T, say to . Now, the maximality of J in T implies that the closed neighborhood contains a vertex belonging to J in T. This immediately implies that the closed neighborhood contains a vertex belonging to in . This completes the verification of the maximality of in . Consequently, and .

Case 2. Now assume that and . This time the sets U, , and are non-empty. Let J be a smallest maximal independent set of T such that . Then and . We shall prove that . Let us first observe that . Suppose that . Similarly as in Case 1 we can observe that is a maximal independent set of the well-covered graph . The well-coveredness of implies that has a maximal independent set containing , say is such a set. Certainly, and, since , the set is a maximal independent set of T and , a contradiction. Consequently, , and, therefore, . We may assume that J contains as many vertices belonging to as possible. Then, in fact, we may assume that is a subset of J (for otherwise if were a maximal independent set of that contains , and if were a maximal independent set of chosen in such a way that (the existence of such sets follows from Remark 1), then the set , for which and (as ), would be a desired maximal independent set of T). Consequently, since and , we finally have . This completes the proof. □