1. Introduction

The first published study on bullying phenomena was written by Burk [

1]. However, this subject matter was not systematically studied until the 1970s by Olweus [

2]. Since then, numerous studies have examined bullying from different perspectives. Research on bullying has investigated settings such as schools and workplaces [

3,

4]. More recently, the term bullying has been expanded to include a new type known as cyberbullying, which is conducted via the Internet. Navarro et al. [

5] have defined cyberbullying and bullying as “aggressive conduct whose objective is to harm another person, which most certainly refers to violent social behavior.” Willard [

6] has suggested the term “digital aggression” [

7]. Hazelwood and Koon-Magnin [

8] and Moy [

9] have indicated that the National Conference of State Legislatures makes a distinction between the terms cyberbullying and cyberharassment. Their differences mainly pertain to the age of the cyberbullied individual. Bullying can be classified as an indirect act in which the bullied individual is not present or as a direct act involving face-to-face contact [

10]. Researchers have raised concerns regarding whether bullying is considered a form of aggression. Berger [

10] has highlighted that “not all aggression is bullying, but bullying is always aggression, comprising hurtful and hostile behavior” [

11]. Johnson [

12] has considered cyberbullying as “indirect or relational aggression” that damages social relationships. Some authors have added anonymity and publicity as features of cyberbullying [

13]. However, the term cyberbullying has frequently been used in the published literature [

3].

Anonymity on the Internet can facilitate cyberbullying attacks. The target for such attacks can be any individual (e.g., one who is popular, famous, physically weak, or strong) [

14,

15]. This action can be repetitive and can create a sense of fear in cyberbullying targets [

8]. A larger audience and unrestricted accessibility to victims makes cyberbullying more destructive than traditional bullying [

7,

10,

12,

16,

17].

Willard [

6] has defined eight common types of cyberbullying: Exclusion, harassment, flaming, cyberstalking, denigration, impersonation, outing, and trickery. Li [

18] has categorized cyberbullying into seven types: Flaming, masquerading, cyberstalking, denigration, online harassment, outing, and exclusion. According to Dooley et al. [

19], there are four types of cyberbullying attacks: (1) Social, (2) psychological, (3) physical, and (4) relational [

20]. Some of the cyberbullying attacks can take the form of making jokes about someone or a group, making mean or aggressive remarks, or spreading rumors and lies [

12]. Cyberbullying exerts negative physical and emotional effects on victims and has been found contribute to increasing rates of attempted suicide [

21]. Worry, fear, depression, terror, and nervousness are among the psychological problems that cyberbullied individuals might feel [

8]. Wang et al. [

22] has shown that cyberbullying indirectly affects depression in bullied individuals via social anxiety. Individuals who are bullied might feel negative psychological consequences, such as depression or lower self-esteem [

23]. Furthermore, Jawaid et al. [

24] have classified cyberbullying as a social vulnerability [

25]. This social vulnerability causes the exclusion of individuals who could otherwise be productive members of society [

24]. According to Ybarra and Mitchell [

26], acts of cyberbullying increase with age. Cyberbullying acts can be driven by revenge [

27] or many other reasons [

28].

Sticca and Perren [

17] have described publicity as the size of the audience communicating via social media, either privately or publicly. They have indicated that publicity attacks in cyberbullying can take a private form (e.g., email) or a public form (e.g., Twitter or Facebook). Dooley et al. [

29] considers publicity to be a factor in cyberbullying. Public cyberbullying has been found to be more harmful than private cyberbullying [

17,

30]. Slonje and Smith [

16] and colleagues have hypothesized that “as the number of people participating online increases, the severity of cyberbullying increases.” However, Menesini et al., [

13] have used a different experimental approach and found that publicity is irrelevant to cyberbullying. According to Vasquez and colleagues, public verbal harassment has a greater negative emotional impact than private bullying [

31]. Otten and colleagues have attributed this aspect to the “larger emotional processing in public encounters,” which produces an increase in brain activity [

32].

Another form of private bullying is a silent treatment, a “relational aggression” performed by a partner [

33,

34]. This is another version of private social exclusion, wherein a partner is intentionally ignored and rejected [

35]. For example, this process can occur when an individual sends many text messages to someone and does not receive any response [

35]. According to a survey by Faulkner et al. [

36], almost three in four Americans have encountered silent treatments. As reviewed by Alhujailli and Karwowski [

37], there have been relatively few studies comparing the effects of verbal harassment and social exclusion. Although, bullying acts across cultures are common, social exclusion form is a more common form in collectivist culture [

38].

Recent meta-analyses by Guo [

39] and Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder, and Lattanner [

20] have shown that few studies have used experimental settings. Guo [

39] has investigated bullying behaviors, such as harassment, threatening, and social exclusion. Another meta-analysis by [

40] has analyzed 120 studies using Cyberball games to study social exclusion. Those studies did not examine other types of cyberbullying, such as verbal harassment. We were unable to find studies indicating whether “verbal harassment” or “social exclusion” is more severe. Therefore, the aim of this study was to advance knowledge about cyberbullying and to provide an understanding of the immediate reactions toward verbal harassment and social exclusion. In terms of gender reactions, Romero-Canyas and Downey [

41] and Reijntjes et al. [

42] have found that females are more receptive than males to private rejection. However, Steele [

43] has found no significant difference in reactions toward bullying between male and female participants.

1.1. Theoretical Background

According to Social Information Processing theory, people engaging in computer-mediated communication might use a virtual communication system (e.g., social media) to engage in social interactions that are equivalent to face-to-face interactions [

44]. Thus, nonverbal cues in physically present interactions have a different form (e.g., unlimited time accessibility) from that of computer-mediated communication. Here, we examined the theoretical aspects relevant to cyberbullying, particularly in terms of affective and stress responses.

1.2. Emotional Responses

People recognize happiness, sadness, anger, and joy as emotions. However, the definition of emotion has been subject to debate. Kleinginna and Kleinginna [

45] have identified as many as 92 definitions of emotion in the literature. However, Brave and Nass [

46] have indicated that “researchers did agree on two aspects of emotion: (1) Emotion is a natural reaction to an event associated with the goals, needs, and concerns of an individual; and (2) emotion involves affective, behavioral, physiological, and cognitive components.” However, dimensional theories classify emotions on a multidimensional basis. For example, the Positive Affect–Negative Affect model (PANA) developed by Watson and Clark [

47] categorizes emotions in two independent dimensions, where the Y-axis represents positive affect (PA), and the X-axis represents negative affect (NA). Though the acronym PANA might mistakenly be understood as representing two opposite affective states, they are two independent dimensional metrics measured simultaneously. PA reflects “the degree to which an individual feels positively active and enthusiastic,” whereas NA reflects “the degree to which an individual feels aversive” [

47]. A high level of PA suggests an enjoyable interaction. NA is generally correlated with unpleasant engagement and distress, both of which reflect aversive feelings, such as disgust, anger, nervousness, or guilt. A low NA level causes a state of “serenity and calmness” [

47,

48]. According to Hinduja and Patchin [

49], cyberbullying promotes negative emotional impacts. These impacts vary not only between individuals but also between the type of cyberbullying experienced [

13]. In the present study, emotional responses were built on the basis of the dimensional basis of PA and NA. Thus, a low level of PA and a high level of NA were expected to be observed during negative social interactions (e.g., cyberbullying) [

50,

51].

1.3. Cyberbullying and Stress

The transactional model of stress and coping theory states that an individualistic appraisal of a stressful event is regulated by how people cope with the level of induced stress [

52]. Cyberbullying has been demonstrated to impose stress [

53]. However, much of cyberbullying research has used the Transactional model of stress and coping [

54]. Williams and Carter-Sowell [

55] have indicated that cyberbullying poses a threat to belonging, which is one of the basic human needs that may lead to stress.

Repetitive negative stressors over time can create emotional distress and degrade performance [

56,

57]. Contrarily, social support can decrease negative feelings about stressful situations [

58,

59]. Stress has been found to reduce performance [

60], and cyberbullying induces immediate emotional responses as well as subsequent stress reactions. Repetitive cyberbullying events cause instant emotional responses and chronic effects. Therefore, cyberbullying can exert both chronic (longer-lasting) and acute (short-term) effects. Matthews et al. [

61] have linked stress factors to Lazarus’ Transactional Model. Hobfoll [

62] has indicated that stress is a result of how situations are appraised.

1.4. Cyberbullying and Coping

Lazarus and Folkman [

52] have defined coping as the “behavioral and cognitive capabilities an individual deploys to tolerate and control stressful events”. Judgment and evaluation are two forms of cognitive appraisal that are correlated with coping demands, both of which are effective factors to predict coping strategy [

63,

64].

Individual differences play an important role in the coping strategy used by individuals faced with stressors [

65]. Individuals reported to use emotion-focused coping are inclined to be more affected by stressful events than those who use problem-focused coping [

66]. Völlink, Bolman Catherine, Dehue, and Jacobs Niels [

54] have claimed that a problem-solving strategy is better than an avoidance strategy. The group has also indicated that during cyberbullying, emotion-focused coping is correlated with health complaints [

54]. Lodge and Frydenberg [

67] have observed that female teenagers who use avoidance coping tend to have low self-esteem.

The self-perception of a cyberbullying threat and the evaluation of which coping strategy to use is called coping appraisal [

68]. Threat appraisals can have different reactions, including the threat of harm, the threat of loss and threat to the self [

64,

69]. Chan and Wong [

70] indicated that younger adolescent male are more likely to deploy an avoidance coping to deal with being cyberbullied. In summary, the coping style adopted is based on individualistic differences and how individuals appraise each threat differently.

1.5. Types of Cyberbullying

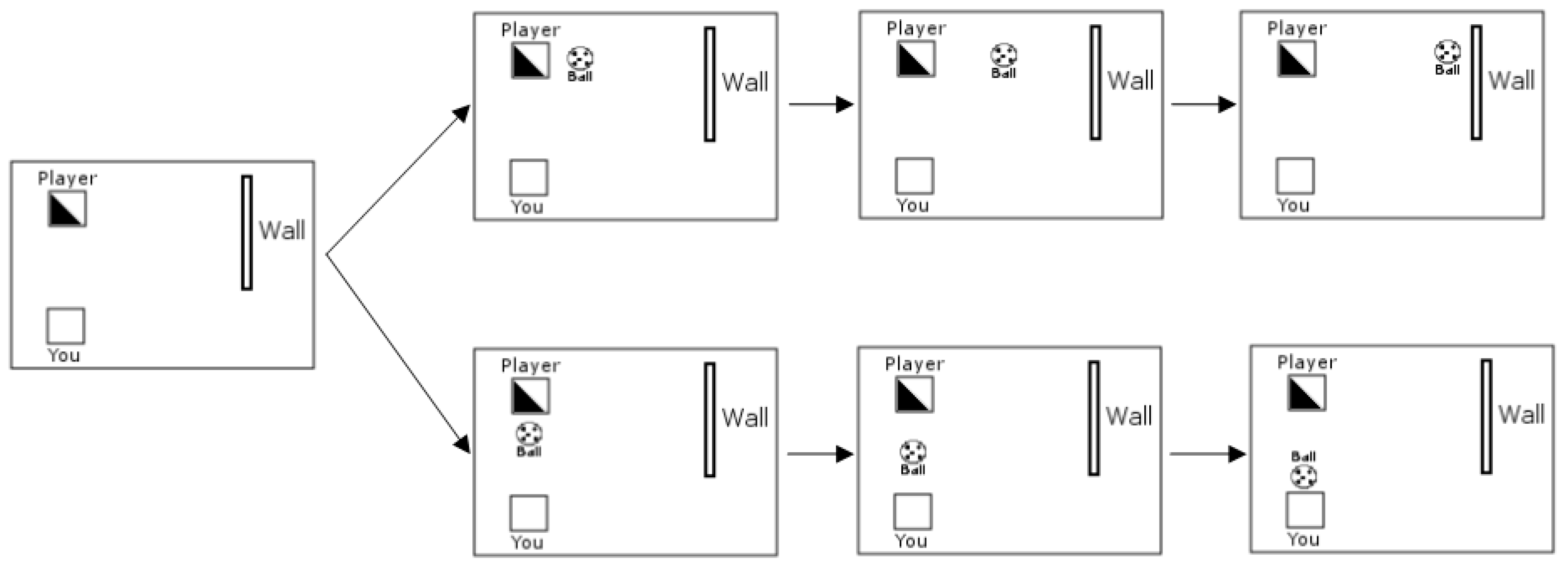

1.5.1. Social Exclusion

Social exclusion occurs in public or private (e.g., silent treatment). Social exclusion is common across cultures and age groups [

33] and has been reported to violate “the need-threat theory” [

71]. The four elements of basic human needs, (1) belonging, (2) self-esteem, (3) control, and (4) meaningful existence [

35,

36,

72,

73], are relevant in cyberbullying events. Cyberbullied individuals score lower than non-cyberbullied individuals in self-esteem after being socially excluded [

74]. Eisenberger [

75] has indicated that social inclusion is “pre-wired in our brain” and that an incident of social exclusion leads to “social pain.” When we sense exclusion, an alarm is triggered that is similar to physical pain, except that the reaction is acquired through experience [

73]. Williams et al. [

76] have conducted an experiment called “cyber-ostracism,” in which they developed a simulated chat room to perform social exclusion and found that cyber-ostracized participants reported negative emotional impacts.

1.5.2. Verbal Harassment

Verbal harassment, in the present context, is text-based bullying that occurs during electronic social interactions. It is the most common form of bullying [

77]. Individuals bullied via both texting and traditional bullying are more depressed than those subjected to only traditional bullying [

78]. Willard [

6] has indicated that “harassment” is equivalent to direct bullying. Deficits in executive functioning have been found to be correlated with bullying behavior in youth engaging in antisocial and aggressive behaviors [

79]. Otten, Mann, van Berkum, and Jonas [

32], using electroencephalography (EEG), have evaluated how the brain reacts to humiliation and investigated what happens when this humiliation is accompanied by public laughter. They have provided evidence that the brain reacts differently after reading humiliating scenarios than complimentary scenarios [

80]. However, Gendron and Barrett [

81] have argued that emotions cannot be justified by brain regions.

1.6. The Current Study

Previous studies have focused solely on social exclusion [

33,

40,

74,

76,

82] or verbal harassment. The main objective of the present study was to investigate the effects of cyberbullying on emotional, stress and coping responses. We also examined how cyberbullying via social interaction and publicity affect emotional and stress responses. We hypothesized that cyberbullying would elevate negative emotional reactions to a greater extent than socially positive interactions. Cyberbullying in public rather than in private was predicted to induce greater negative emotional reactions, as reflected by lower PA and higher NA. Cyberbullying in public was anticipated to generate higher negative stress responses than socially positive interactions, as indicated by at least one of the following attributes: A reduction in task engagement, an increase in distress, and/or an increase in worry. We also predicted that cyberbullying in public rather than in private would induce different levels of coping strategies, reflected by task-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and/or increased avoidance, as indicated by at least one of the following attributes: Decreased task focus, increased emotion focus, and/or increased avoidance.

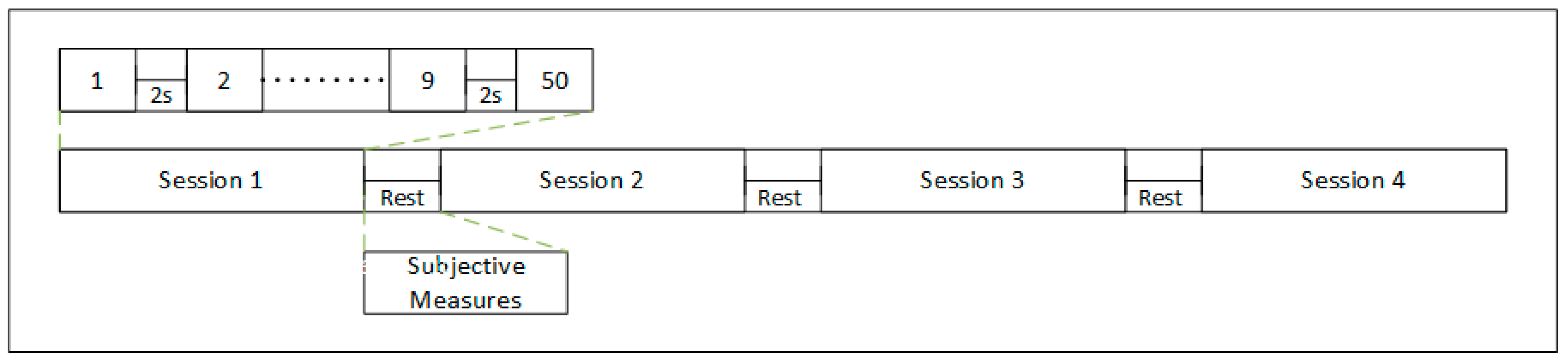

3. Discussion and Conclusions

The results of these two experiments contribute to research investigating the psychosocial effects of cyberbullying. Our findings specifically demonstrated the effects of cyberbullying through social exclusion and verbal harassment on emotional, stress, and coping responses. These effects were studied in terms of social interaction and cyberbullying publicity. Social interaction influenced subjective emotional, and stress responses. In general, cyberbullying studies remain in their infancy [

99,

100], but the preliminary findings of this research make a substantial contribution to the literature by answering the question of which type of cyberbullying has more significant effects in terms of emotional, stress, and coping responses. It also sheds light on the involvement of publicity as a factor.

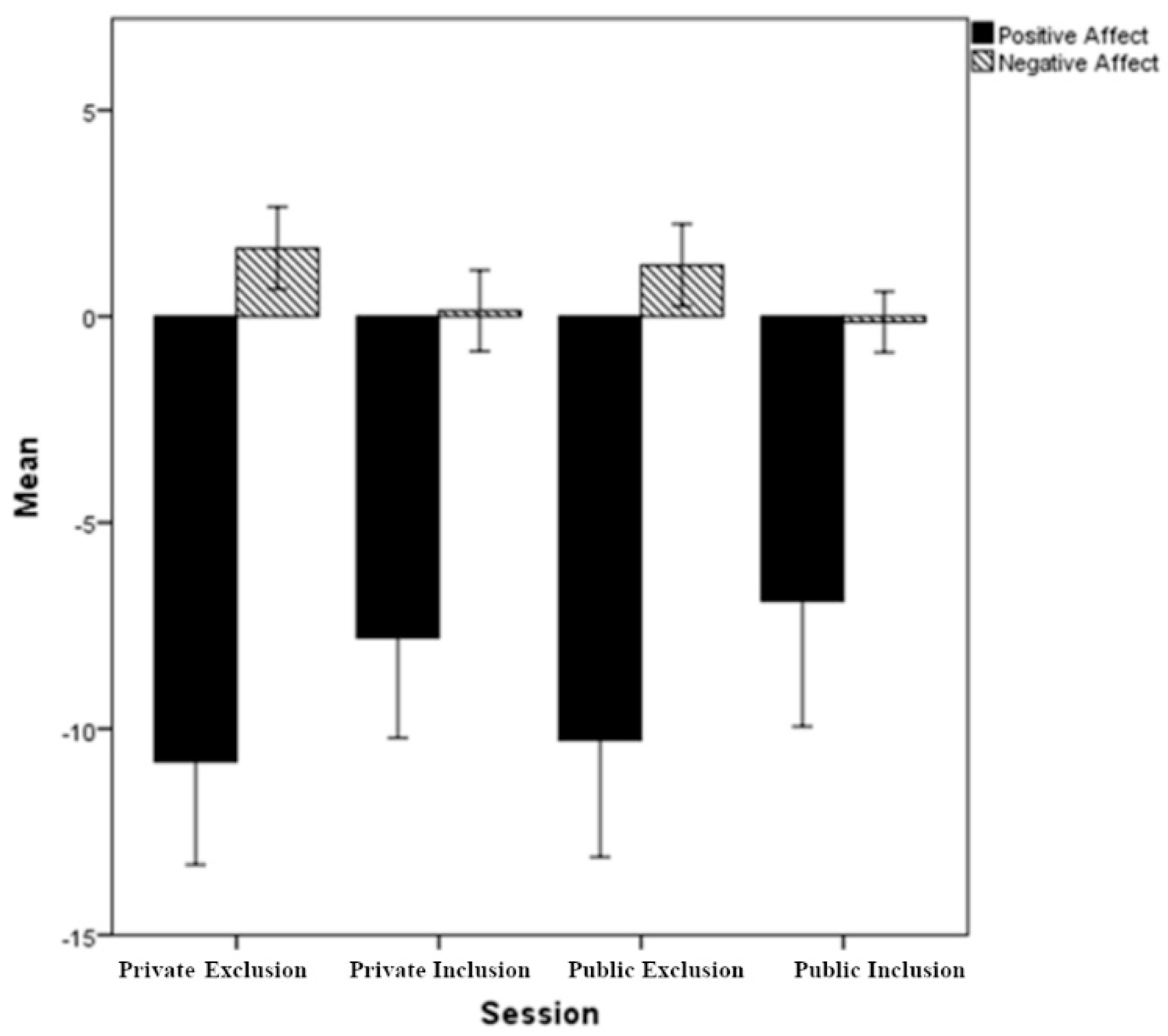

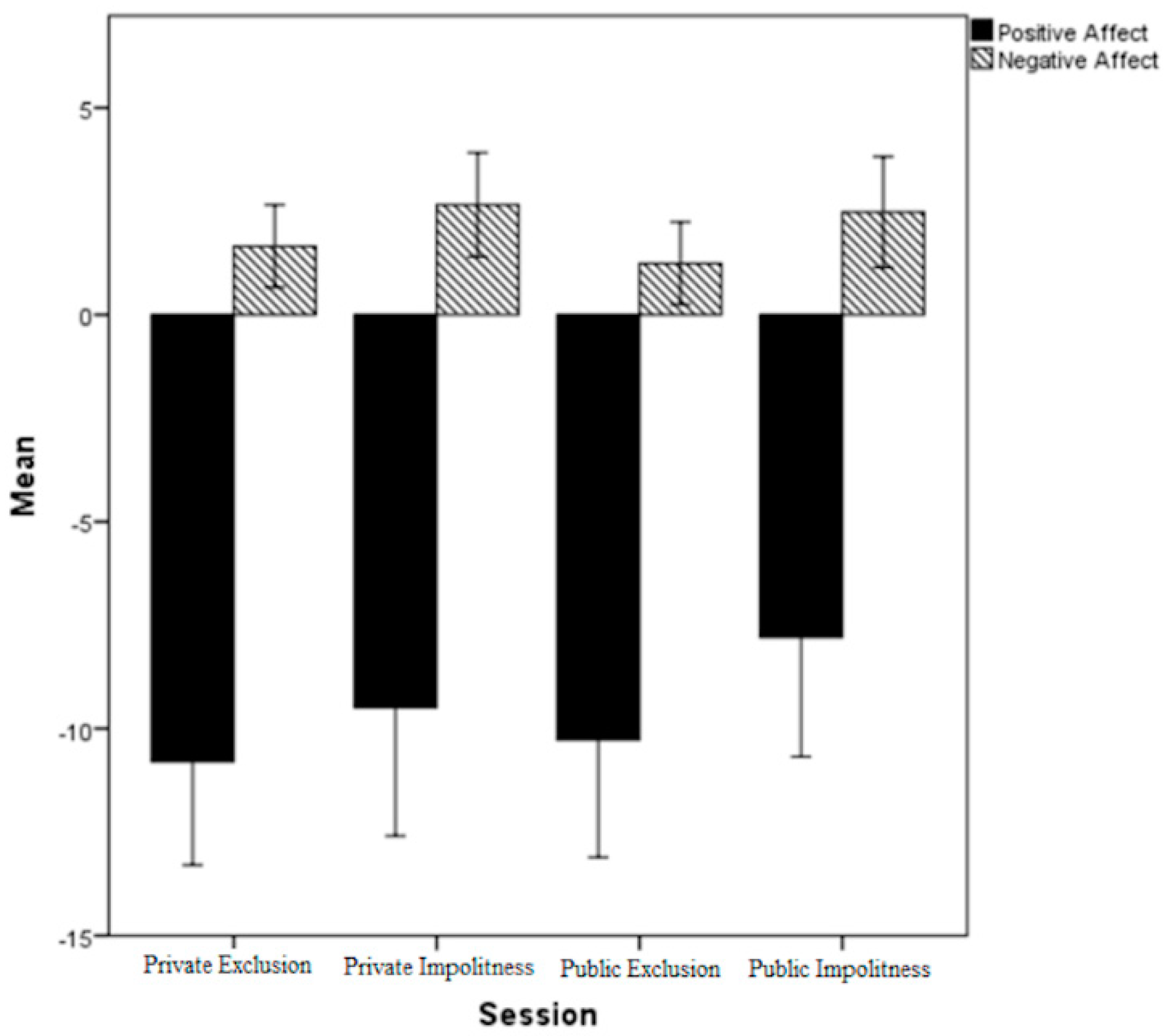

Emotional responses. Cyberbullying through social exclusion and verbal harassment was predicted to induce negative emotional reactions, as a function of two independent dimensions (PA and NA). This hypothesis was supported by both studies. Thus, if a person is being cyberbullied, a lower level of PA and greater NA would be expected. Our results also suggest that being a victim of cyberbullying might destroy the victim’s positive wellbeing. In line with previous studies conducted by Ruggieri, Bendixen, Gabriel, and Alsaker [

74], our results indicate that negative online interactions have negative emotional impacts. Cyberbullying victims might suffer general stress during the day to day activities. They are likely to have school stress and health problems like headaches or nausea [

101]. Worth noting that during social interaction in a computing environment, emotions are not easily perceived. Thus, cyberbullies might not observe the emotional impact on their victims [

28,

29]. This indicates that emotional impact needs to be explored in future studies.

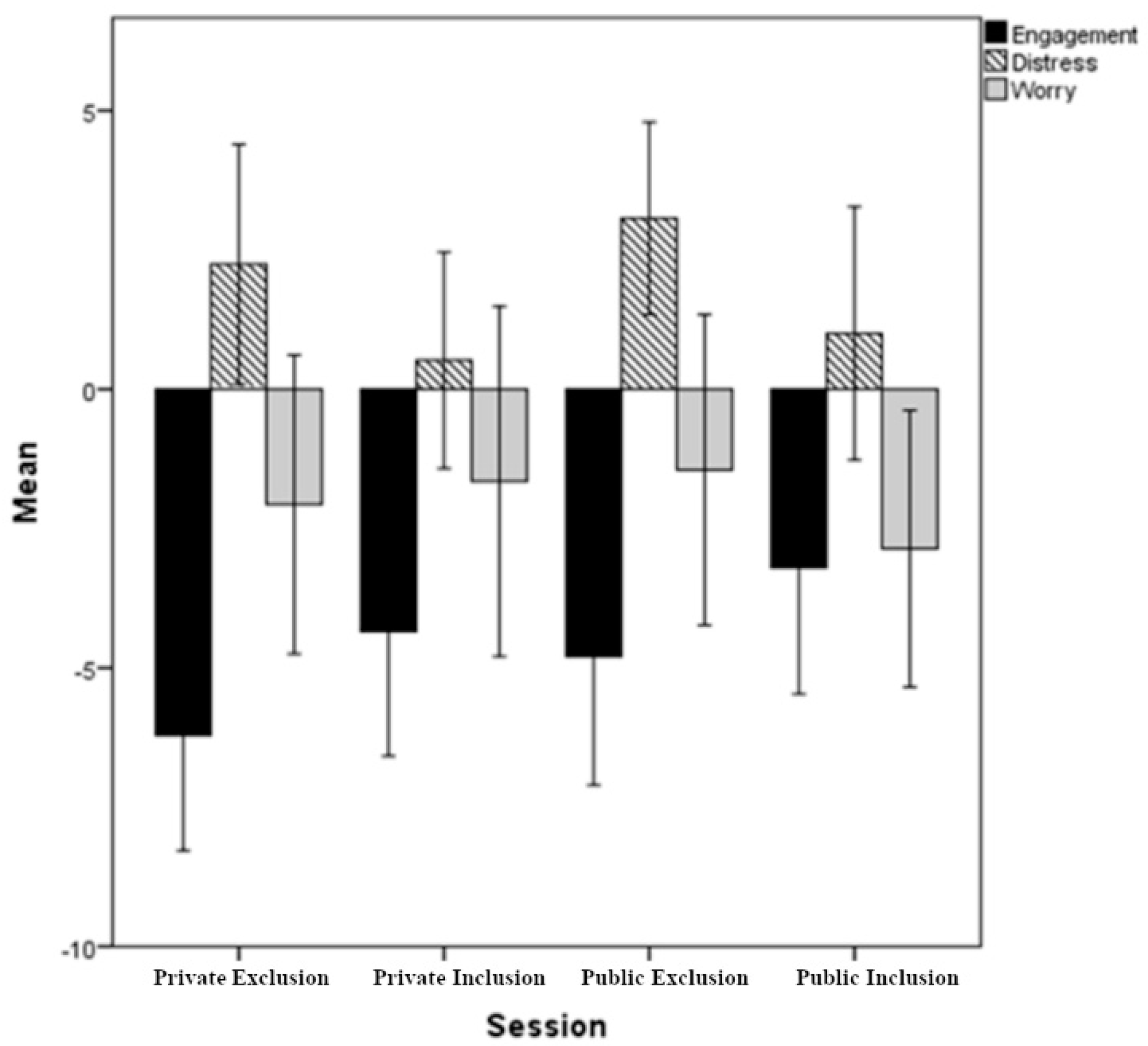

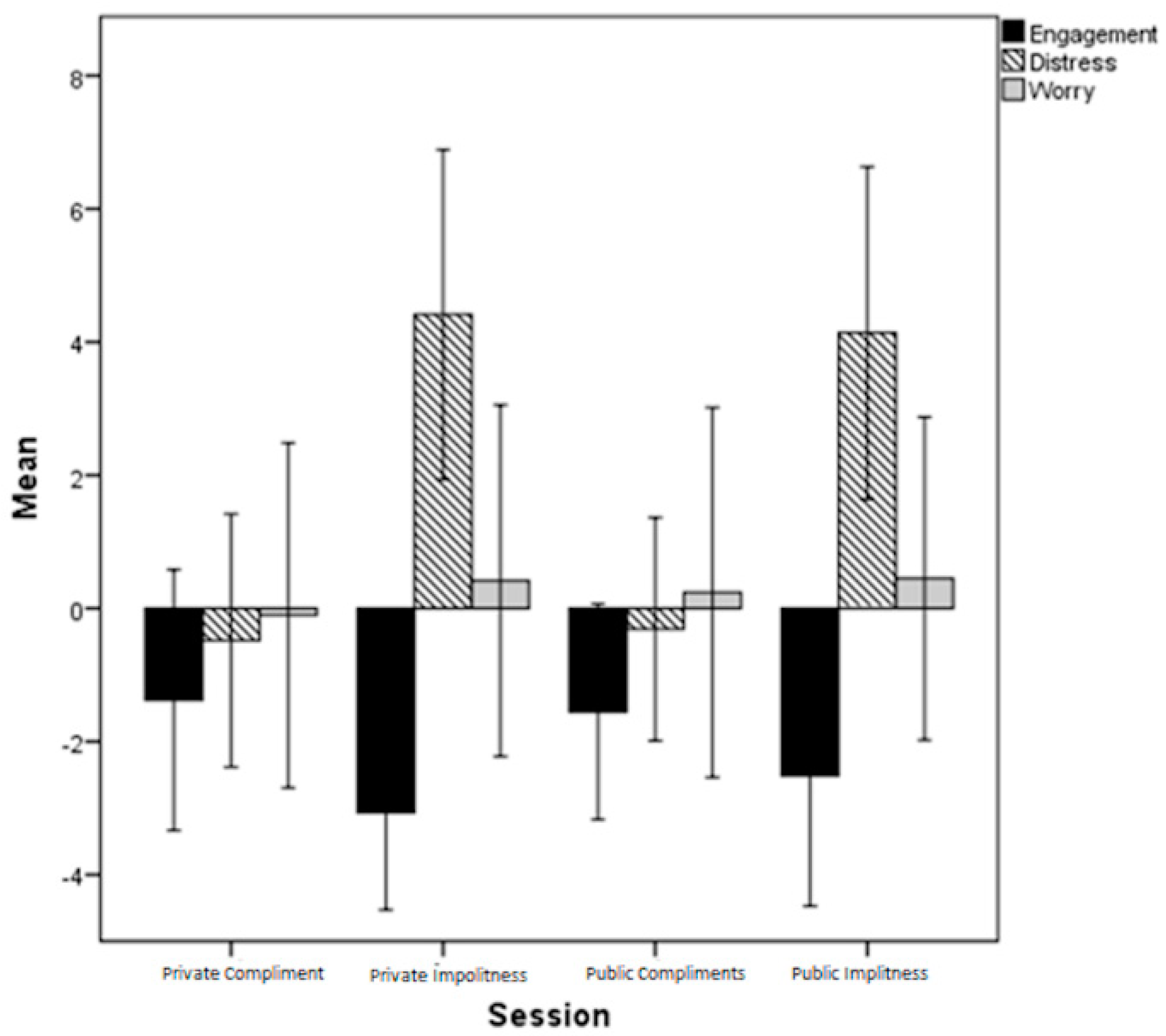

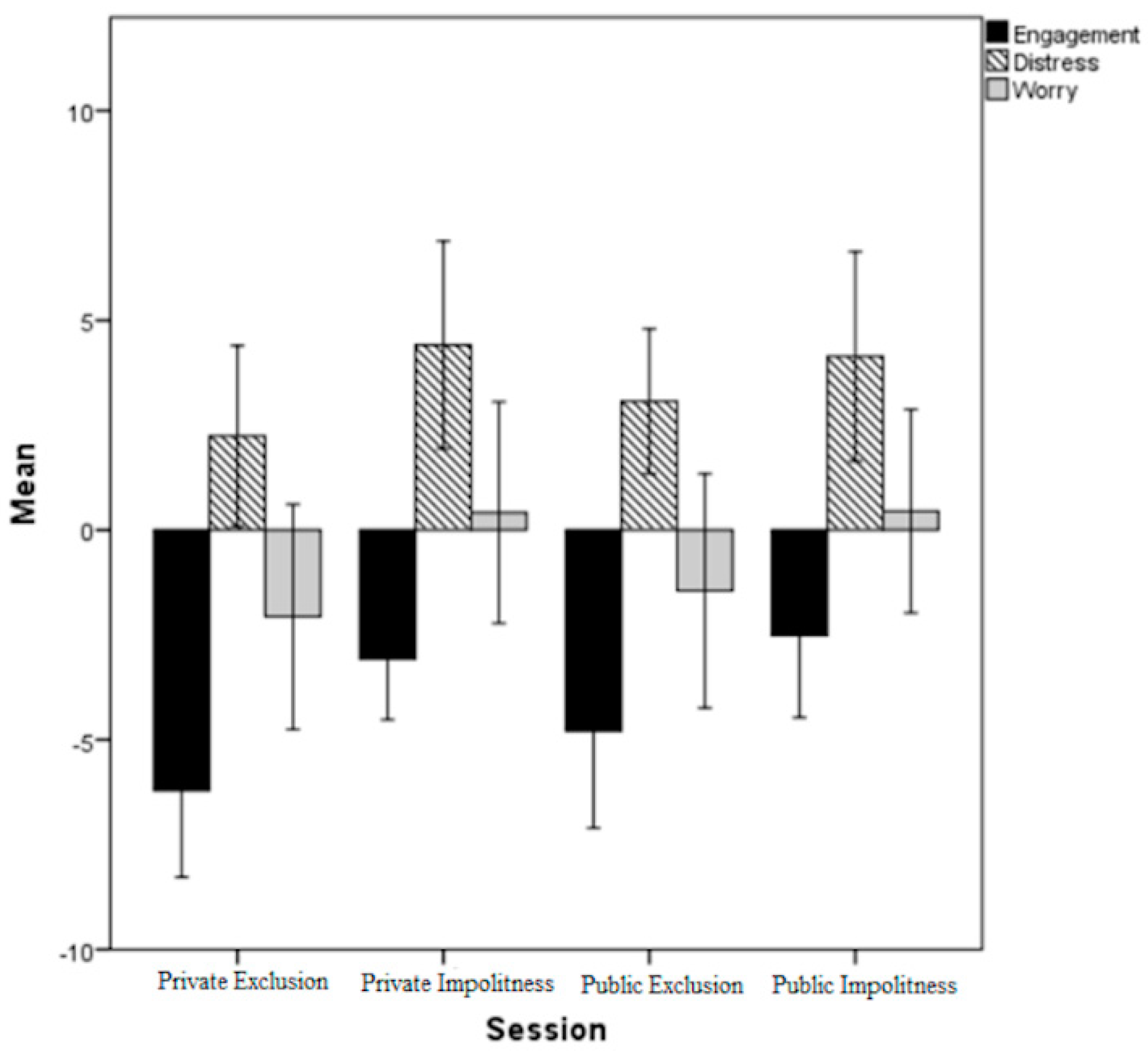

Stress responses. This study considered acute stress as a function of engagement, distress, and worry. A person being cyberbullied was predicted to have lower task engagement, higher distress, and higher worry than a person who was not bullied. Our research outcomes demonstrated stress due to social exclusion, as evidenced by a lower level of task engagement and an increase in distress only. The resulting analysis did not show any significant effect for worry. However, stress due to verbal harassment was observed, as explained by increases in distress. According to a study by Menesini, Nocentini, Palladino, Frisén, Berne, Ortega-Ruiz, Calmaestra, Scheithauer, Schultze-Krumbholz, Luik, Naruskov, Blaya, Berthaud, and Smith [

13], almost 25% of the participants were not worried if they were being cyberbullied. This finding links the failure to observe worry during social exclusion session to individual differences. On the other hand, impolite comments induced higher worry than social exclusion while impolite comments increases engagement. Up to our knowledge, No previous study compared between verbal harassment and social exclusion. However, observing stress in general terms is consistent with a study of acute stress by Veenstra et al. [

102], who have reported that being bullied increases the level of stress. Waisglass [

103] has reported that bullying can lead to chronic stress. However, being cyberbullied increases the level of distress [

17]. The findings of this study confirm the correlation between stress and cyberbullying.

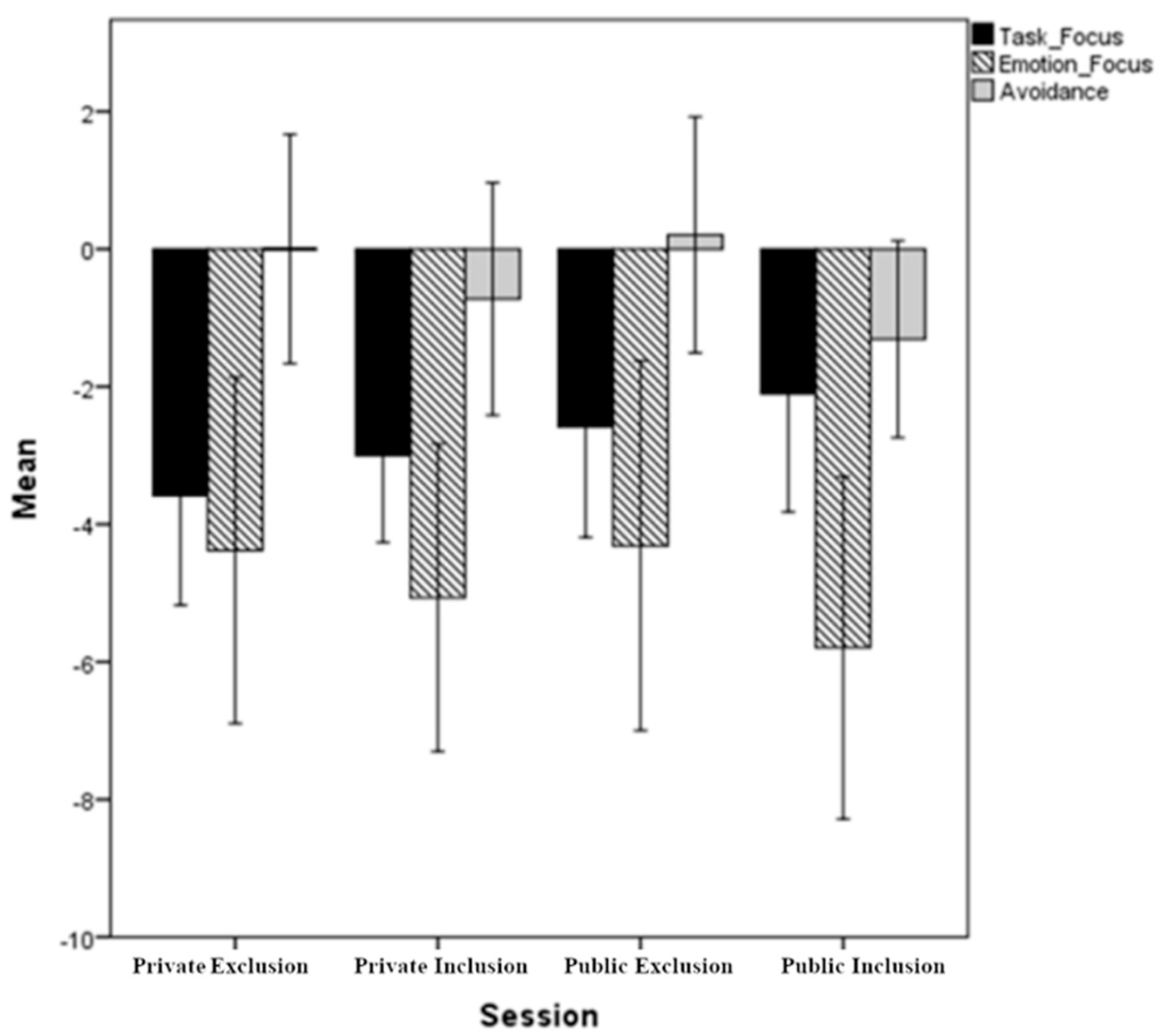

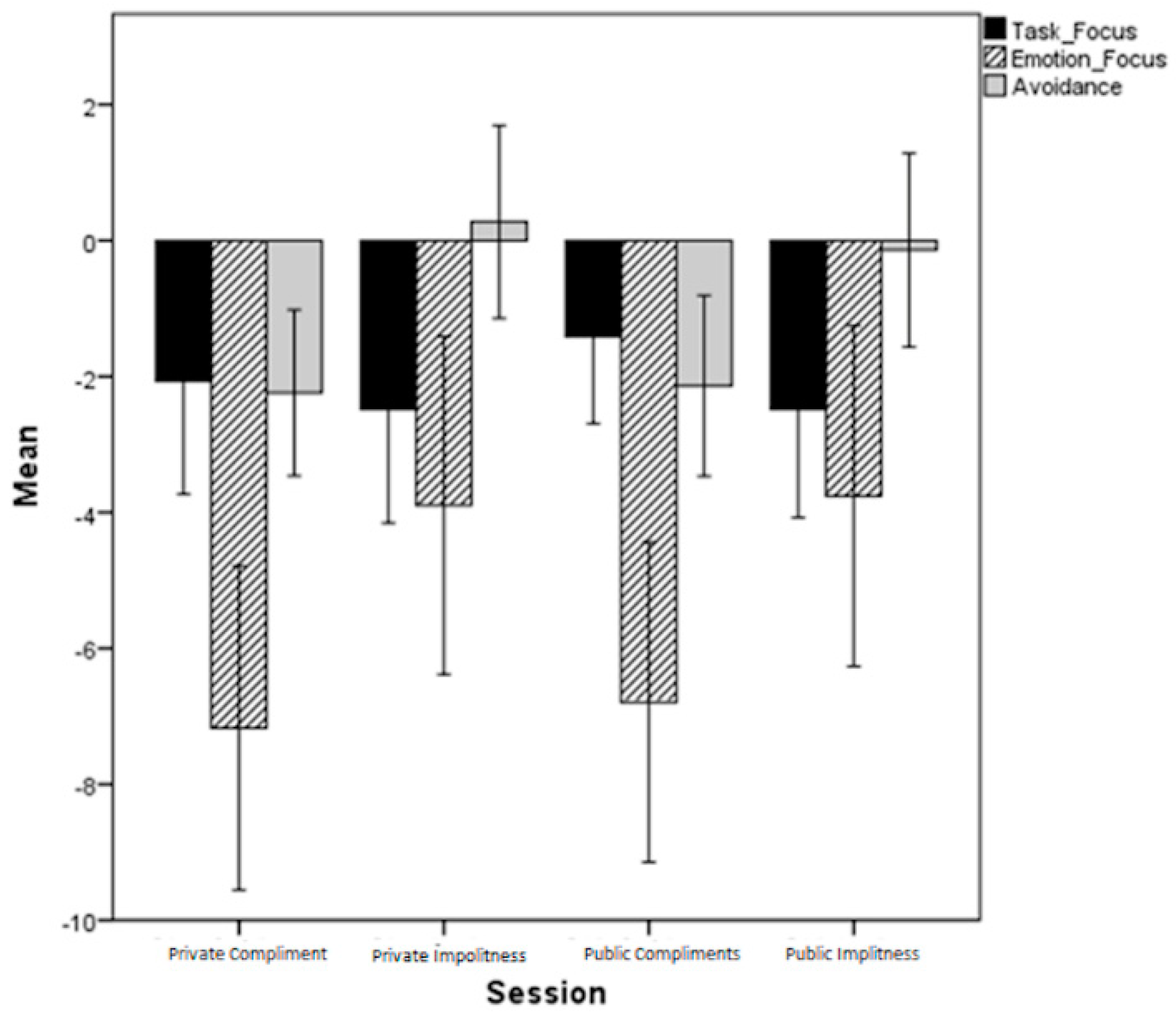

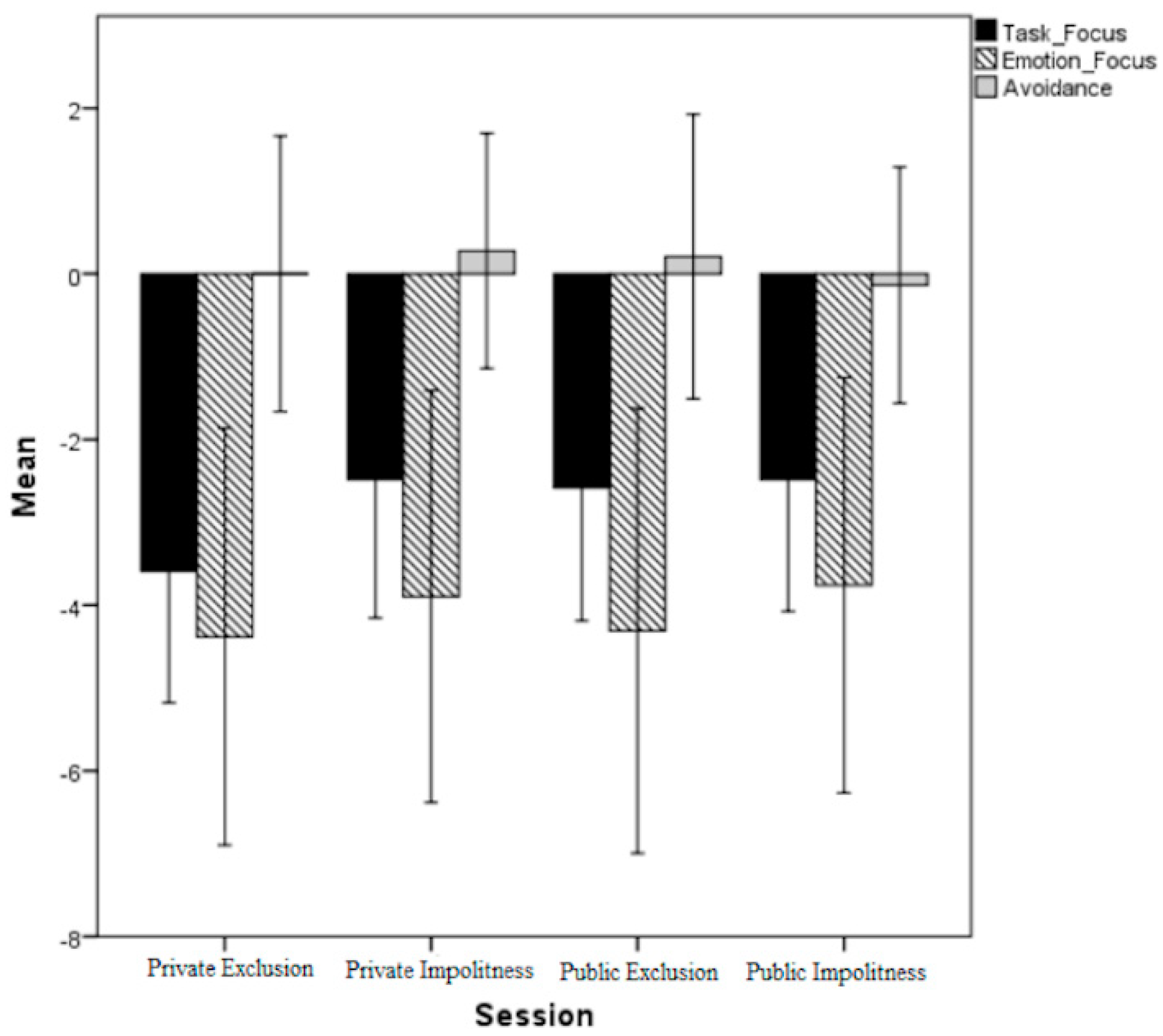

Coping responses. This exploratory hypothesis evaluated how individuals would cope with being cyberbullied. Being cyberbullied was expected to decrease task-focused coping, increase emotion-focused coping, and increase the level of avoidance. This hypothesis was partially supported. However, the literature indicates a mixed view of the coping strategy. Most cyberbullied individuals cope with cyberbullying by ignoring the situation [

54,

104]. However, Lazarus and Folkman [

66] have indicated that coping strategies used by children faced with many stressors depend mainly on which strategy is adopted. However, any coping strategy adopted depends on the victim’s personality but, in general, has been found to reduce the negative effect of stressors [

105]. There are differences between aggressive and passive cyberbullying victims in terms of the coping strategy used [

70]. Machackova et al. [

106] reported that cyberbullying victims use many problem-focused coping strategies except for avoidance strategies. Victims also tend to seek an active solution. The more prolonged ongoing harassment online, the more likely it is to cause more harm than infrequent online harassment [

107]. Technological coping strategies, such as blocking the aggressor, were generally effective popular and considered effective [

106]. Such coping strategies have been categorized under avoidance coping type. Some studies indicated that bullying activities in collectivist cultures like India and China might lead to intense emotional distress that induces toxic behaviors such as mistrust [

108]. However, such actions can be alleviated if appropriate psychological support like friendships is used. Some studies indicated that bullying is not always harmful, as it might sometimes lead to improvements in performance and creativity [

108,

109,

110,

111].

Verbal harassment through impolite comments vs. social exclusion. Verbal harassment through impolite comments, compared with social exclusion, increases NA, engagement, and worry. Distress showed significant differences, and verbal harassment was found to be more distressing than social exclusion. This result indicates that verbal harassment induces negative emotions and increases distress and worry. This finding is consistent with those of Pieschl, Kuhlmann, and Porsch [

30], who have observed that harassment is more distressing than social exclusion. Distress varies between bullying and cyberbullying [

112]. In line with the findings of Otten and Jonas [

81] verbal harassment has a more intense emotional impact. As indicated by Lazarus [

113], active coping is more prevalent during negative emotional encounters [

80]. This suggests that active coping is more likely to regulate emotional consequences. Self-evaluations capacity allows individuals to evaluate their behaviors and decide whether they hold or not hold responsibility for the action taken [

113]. Thus, experiencing verbal harassment might need to be assessed as a cognitive skill. Otten and Jonas [

81] suggest that cognitive resources required to regulate behavioral and emotional consequences are more likely during negative emotions.

Menesini, Nocentini, Palladino, Frisén, Berne, Ortega-Ruiz, Calmaestra, Scheithauer, Schultze-Krumbholz, Luik, Naruskov, Blaya, Berthaud, and Smith [

13], indicated that although publicity might not be a factor that influences cyberbullying through experimental studies, it cannot be ruled out. They have also indicated that publicity is indirectly relevant to the cyberbullying definition. Publicity has been considered to be one of the main cyberbullying factors [

29]. Slonje and Smith [

16] have stated that “as the number of people participating online increases, the severity of cyberbullying increases.” Pieschl et al. [

114] and Sticca and Perren [

17] have indicated that public cyberbullying is more stressful than private cyberbullying.

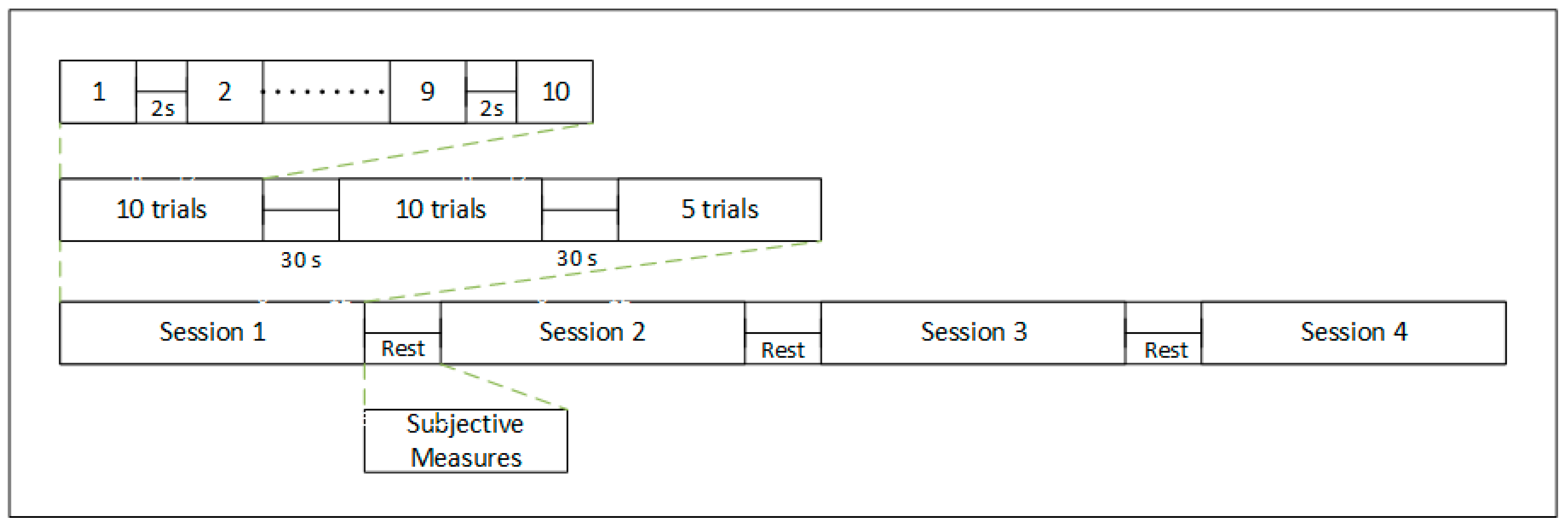

To our knowledge, no previous studies have used the DSSQ-3 or CITS instruments to study cyberbullying. The key strength of this approach is that both instruments can be used to study the stress and coping states, thus facilitating measurement of the self-reported stress responses and coping strategies after each experimental session. The findings of this experimental study must be interpreted with caution, owing to the small sample size. Other limitations preventing the generalization of the results are that the study was performed in a single institution, with psychology students in an introductory course (aged 18‒22 years). Some of the statistical findings in this study might be a result of limited statistical power because of the small sample size (

n N = 29). A second limitation is that the study relied on a mixture of hypothetical scenarios, thus potentially limiting the validity of our results. We used laboratory settings designed to stimulate cyberbullying. In real-life scenarios, cyberbullying acts are not subject to laboratory ethical restrictions. Previous studies using self-reporting have indicated sensitivity to cyberbullying publicity [

29]. This study also did not consider gender differences. Future cyberbullying research should investigate the effects of age and gender. Finally, this study evaluated only two types of cyberbullying. Future research should examine other types of cyberbullying (e.g., cyberstalking).

As government and state administrators are acting to combat cyberbullying. The possible implication of this study might help. It is essential to be aware of the serious impact of cyberbullying on victims and prepare the appropriate intervention mechanism. Young generations rely heavily on technology where it is common to encounter cyberbullying acts. Although intervention techniques and programs to prevent cyberbullying are in their infancy, it is not currently clear what technologies and programs will be effective in reducing cyberbullying. This study shows that cyberbullying can have serious negative emotional impacts. However, the degree of reacting toward the type of cyberbullying vary based on individualistic characteristics and culture. This study might also help to find mechanisms that may help detect exposure to cyberbullying. As cyberbullying incidents become more frequent, it is crucial to realize the negative impacts and intervene correctly. Effective coping mechanisms require education and training programs. Those training programs might provide coping skills and social support for cyberbullying victims to alleviate distress [

115].

In summary, this experimental study provides insight into the temporal reactions to cyberbullying in terms of being verbally abused or excluded. Experiencing cyberbullying affects victims’ wellbeing. Regarding the question of whether verbal harassment or social exclusion is more severe, participants rated verbal harassment as more critical. Given this finding, future research should further investigate and assess the effects of cyberbullying by using different experimental settings and different age groups. Hartgerink, van Beest, Wicherts, and Williams [

40], while studying school shootings, have found a link between ostracism and revenge. This study might be useful for anti-cyberbullying campaigns in educational and professional environments. However, Berne et al. [

116] have indicated that students are willing to support and participate in anti-cyberbullying campaigns. The mechanism provided herein might be used to educate younger people on the two critical types of cyberbullying.