Abstract

Nowadays, individual identification is a problem in many private companies, but also in governmental and public order entities. Currently, there are multiple biometric methods, each with different advantages. Finger vein recognition is a modern biometric technique, which has several advantages, especially in terms of security and accuracy. However, image deformations and time efficiency are two of the major limitations of state-of-the-art contributions. In spite of affine transformations produced during the acquisition process, the geometric structure of finger vein images remains invariant. This consideration of the symmetry phenomena presented in finger vein images is exploited in the present work. We combine an image enhancement procedure, the DAISY descriptor, and an optimized Coarse-to-fine PatchMatch (CPM) algorithm under a multicore parallel platform, to develop a fast finger vein recognition method for real-time individuals identification. Our proposal provides an effective and efficient technique to obtain the displacement between finger vein images and considering it as discriminatory information. Experimental results on two well-known databases, PolyU and SDUMLA, show that our proposed approach achieves results comparable to deformation-based techniques of the state-of-the-art, finding statistical differences respect to non-deformation-based approaches. Moreover, our method highly outperforms the baseline method in time efficiency.

1. Introduction

Currently, biometric systems are developed as a response to current increasing security demands. People identification and authentication through biometric procedures are basic tools in present-day society, as they can prevent frauds, impersonation, access control to human beings movement, and undesired access to office, without utilizing passwords, keys, ID, magnetic cards, or any other vulnerable means of identification [1]. They are very useful in e-commerce since they help the consumer to carry out safe transactions in an undisturbed way. In the current state of affairs in the world, in which digital mobility and e-commerce are on the rise, these benefits are increasingly important [2]. It should be mentioned that in the last six years 112 billion US dollars have been lost around the world due to identity supplantation, which is equivalent to a loss of 35,600 US dollars every minute [3].

Unar et al. [4] extensively review the biometric technology along their potentialities, market value, trends, and prospects. A biometric system aims to recognize the identity of a person based on its physiological characteristics or other behavioral traits [5,6]. Jain et al. [5] established the criteria that should be satisfied by any biometric trait, essentially: universality, distinctiveness, collectability, performance, acceptability, and circumvention. Thus, several types of biometric traits have been proposed, such as fingerprint [7,8], face [9,10], iris [11,12], palmprint [13,14], voice [15,16], finger and palm vein [17,18], gait [19,20], signature [21,22], DNA [23,24], among others.

Particularly, finger and palm vein patterns, also known as vascular biometrics, have focused the attention of the scientific community in recent years [25]. Finger and palm vein are internal structures in the human body, which present significant biometric attributes such as universality, distinctiveness, permanence, and acceptability. Besides, vascular biometrics have three distinct advantages [26]: (1) must be caught in a living body, avoiding fraud techniques with parts of deceased individuals; (2) are very difficult to duplicate or adulterate; and (3) do not present harms because of external components, contrarily to fingerprint, iris, or face. These advantages guarantee the high security the technique, which has multiple applications such as in banks, legality support, as well as countless applications with high-security requirements. Table 1 compares the main characteristics of the most used biometric techniques [17].

Table 1.

Comparison of the main characteristics of the most used biometric techniques, from the work by the authors of [17].

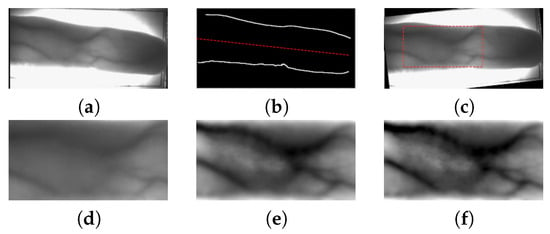

The performance and quality of the results in the recognition of finger vein patterns have been improved by several approaches in recent years [17,27,28]. During the image acquisition process, the captured images present deformation effects due to the contactless capturing procedure, as is shown in Figure 1. Commonly, most of the methods try to prevent the influence of these deformations in recognition performance. On the contrary, the approach proposed by Meng et al. [27] is highlighted because it proves that the displacement information between finger vein images can be used as discriminatory information, achieving a high recognition performance. The principles introduced in the work by the authors of [27] prove that the geometric structure of finger vein images remains invariant, despite the affine transformations produced during the acquisition process. These considerations are closely related to the most modern interpretation of symmetry phenomena introduced by Darvas [29]. Thus, the proposed approach applies the generalized symmetry concept [29] in order to establish the correspondences between genuine and imposter samples. However, the main disadvantage of their methodology is related to the high computation time of the matching process due to the dense correspondence between images.

Figure 1.

Effects of deformations on finger vein images due to the contactless capturing procedure. The first row corresponds to different samples of the same finger from PolyU database and the second one from SDU-MLA dataset.

Among the real applications of finger vein recognition are those that verify the identity of people. The biometric system compares the test sample and the previously stored template for the individual, performing only a 1:1 matching. There are multiple examples and reports about authentication applications in the field of physical security at banks, financial applications, hospitals, and others [30,31,32,33,34]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no real applications of individuals identification are known, where exhaustive comparisons are required within a database of millions of people. Thus, to identify individuals in a massive database, a finger vein recognition system requires performing a real-time-matching process. Hence, our work contributes to reduce the execution time of the matching process between finger vein images.

In the literature, some techniques that interpolate the optical flow from sparse correspondences [35,36,37,38], contrarily to dense correspondences proposed in Meng et al. [27]. These methods are known as sparse matching algorithms and they show great success in efficiency and accuracy. In the present work, we address the limitations of dense correspondences by using an efficient sparse matching algorithm. The proposed methodology achieves state-of-the-art accuracy and highly outperforms the baseline method in time efficiency. Our proposal aims to develop a new method for real-time individuals identification, able to use a large database. Thus, our method combines the efficiency and accuracy of a sparse-matching technique with the speed-up of a multicore parallel, platform for improving finger vein recognition for massive identification. Therefore, our approach has three major contributions:

- First, in contrast to other authors that use global normalization and histogram equalization to improve the image quality during the preprocessing step, we apply a block-local normalization and a sharpening filtering aiming to enhance the local details of vein images. Section 3.1 explains the preprocessing procedure implemented in our approach.

- Second, we propose to use the Coarse-to-fine PatchMatch (CPM) algorithm [38] as a sparse-matching technique to reduce the number of comparisons of dense correspondences during the matching process. This method achieves equivalent recognition performance in comparison to the baseline approach proposed by Meng et al. [27] and highly outperforms its results in terms of execution time, achieving a speed-up of 9×. Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 present the details of the feature extraction and matching processes.

- Third, to increase the number of queries per second and reduce the computation time of the matching process, we implement a master-worker scheme in a round-robin fashion to compute the similarity tests between finger vein images. To the best of our knowledge, our approach is the first that incorporate parallel techniques for finger vein recognition. Section 3.5 describes the implemented parallel scheme.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, in Section 2, we review the related works regarding finger vein recognition and image matching techniques based on optical flow. Section 3 describes the proposed methodology. Finally, we discuss the experimental results in Section 4, and conclusions are given in Section 5.

2. Related Works

2.1. Finger Vein Recognition

A finger vein recognition system includes four main processes: image acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, and recognition, as it is depicted in Figure 2. The image acquisition is performed by using a near-infrared (NIR) scanner device that captures the finger vein image. The preprocessing procedures obtain the region of interest (ROI) from the captured image and apply enhancement techniques to improve the details of vein patterns. The image representation is carried out during the feature extraction process and later the obtained descriptor is used for matching purposes. Feature extraction and matching processes are critical components for the performance of the system [39].

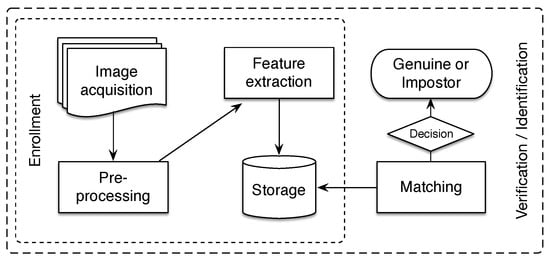

Figure 2.

Flowchart of a typical finger vein recognition system.

Several works propose multiple approaches for the extraction of traits and patterns from the finger veins [26,27,28,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Methods based on local patterns extract characteristics at the pixel level, including descriptors such as local binary patterns (LBP) [40,42] and their different variants [41,43,48,49]. The performance of these methods is affected by deformations because of the pixel-to-pixel processing. Network-based methods start by extracting features from segmented blood vessels, and the recognition is carried out according to the similarity of vein patterns. The work by the authors of [50] based on mean curvature (MeanC), the method proposed by Miura et al. [51] that uses maximum curvature points (MaxC), the work by the authors of [26] by using of repeated lines tracking (RLT), and the proposal by the authors of [47], which projects the curvature of the valley into Radon space, are in this category. However, the segmentation of blood vessels lacks precision, which is the major disadvantages of these approaches. Other proposals use minutiae as identification features [40,45,52,53], however, their extraction is limited in finger vein images, which reduces the accuracy of the results. On the other hand, there are methods based on machine learning, mainly in the analysis of principal components (PCA) [44,46,54,55], linear discriminant analysis (LDA) [56], and, recently, some authors [28,57,58,59] have proposed finger vein recognition methods based on deep learning approaches, which have been successfully applied and enhance finger vein recognition methods. In these cases, training images are not enough available for the configuration of the transformation matrix, so its operation is not satisfactory in this regard.

Despite the contributions made by the aforementioned works, the recognition results do not show significant improvements, mainly due to problems with image quality and deformations [60,61]. The image quality is usually solved using restoration techniques [62] or visual improvement [61,63]. Regarding deformations, the finger vein images are severely affected by them, because fingers are flexible and the capture is made without physical contact. In this regard, it should be highlighted the work of Meng et al. [27]. They propose a new perspective by using displacement between finger vein images as discriminatory information, contrarily to others that try to reduce the influence of deformations [40,45,50,63].

The methodology proposed by Meng et al. [27] is on the basis of two key ideas that allow distinguishing between genuine and imposter samples: (1) the displacement in a local region tends to be similar in a genuine matching because the pixel and its neighbors are similar in deformations, see Figure 3a, and (2) the displacement tends to be homogeneous in a genuine matching due to two similar images share the same vein structure. Thus, the dense correspondences of the SIFT descriptor [64] are used for obtaining the displacement matrices based on the proposal of Liu et al. [65]. From the displacement matrices, the feature of uniformity texture [66] is extracted, which is the final similarity degree. This approach uses deformations as discriminatory information and it is much more discriminative than traditional approaches.

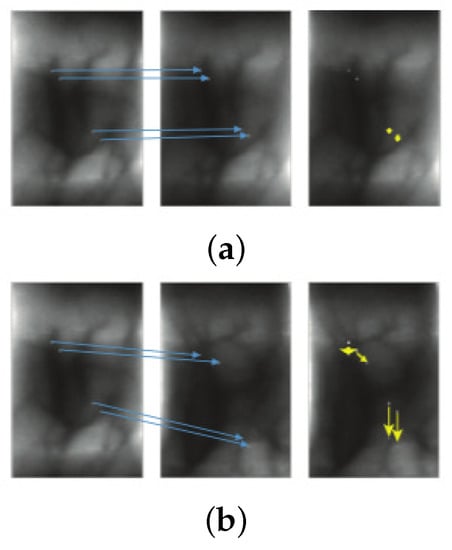

Figure 3.

Characteristics of displacements between finger vein images: (a) Genuine matching: displacements tend to be similar for matched pixels. (b) Imposter matching: there are variations on displacements for matched pixels. Images are from the work by the authors of [27].

As has been presented, the performance and quality of the results in the recognition of finger vein patterns have been improved by several approaches. However, in general, the problem presented by these techniques is their high complexity, which leads to temporary inefficiency, especially for massive civil applications (applications for banks, access control, assistance control, among others), in which the waiting time of the user is a very important factor. On the other hand, the reduction of the matching time is interesting in forensic applications when a database of millions of records is involved, where it is also critical to take into account the execution time.

Our proposed method aims the execution time of the matching process of finger vein recognition. To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first approach for real-time individuals identification based on finger vein patterns that is suitable for use in massive identification. The experimental results discussed in Section 4 show that our methodology achieves a very high speed-up and its recognition accuracy is comparable with the state-of-the-art techniques.

2.2. Image Matching Based on Optical Flow

Image correspondence or matching is an important problem in many computer vision applications. There are different approaches aim to match or align two images, ranging those applied to scene recognition to optical flow estimation [65]. The goal of image matching algorithms is to establish as many as possible precise pointwise correspondences or matches between two images, discovering shared visual content within them. Image matching techniques based on local features have been extensively studied in the literature during the past decade [36,38,65,67]. Besides, some image matching approaches are inspired by optical flow methods [35,36,37,38,65,68]. These techniques produce dense correspondences, such as an estimation of a 2D flow field, to obtain the correspondence between two images. Furthermore, some proposed biometric techniques estimate the similarity of images based on optical flow methods [27,65,69,70].

The image matching approaches can be divided into dense [65,68] and sparse [35,36,37,38] algorithms. The dense algorithms match densely sampled pixel-wise local features by using the information of every pixel of the image, contrary to sparse methods that take advantage of sparse feature points. Although dense matching techniques achieve excellent accuracy, they require high computation costs. On the other hand, sparse-matching approaches reduce the computation time of dense matching finding correspondences for local image patches. In the present work, we propose to use a sparse matching method to obtain the displacements between finger vein images. Our approach reduces the computation time of the baseline method proposed in [27], which is based on dense correspondences.

Among the sparse-matching approaches, we study three recent algorithms, which are summarized in the following. In the work by the authors of [35], the authors select correspondences between patch pairs of images, where each patch is a sparse match in both ways. Their method is known as SparseFlow. Revaud et al. [37] introduce the DeepMatching algorithm, which is inspired by deep convolutional approaches. This technique breaks down patches into a hierarchy of sub-patches by using a multi-layer architecture, handling nonrigid deformations and incorporating a multi-scale scoring of the matches. Besides, the Coarse-to-fine PatchMatch algorithm is proposed by Li et al [38]. It computes correspondences between images by combining an efficient random search strategy and a propagation procedure with constrained random search radius between adjacent levels on a hierarchical architecture. Their method captures displacements of the tiny structures by using a fast approximate structure for the matching process. It avoids finding instances of every pixel achieving a significant speed-up with controllable accuracy, which is its main advantage.

Based on the characteristics of the studied techniques, we propose to use the CPM algorithm [38] for the matching process of our approach. We think that the fast approximate structure proposed in [38] is useful to reduce the high computation costs required by the dense matching of the baseline method [27]. However, in Section 4.6, we compare the performance of our proposal and the other two sparse matching methods.

3. Methodology

In this section, we present the different processes of the proposed finger vein recognition method, which is depicted in Figure 4. In the following, we pay special attention to our main contributions highlighted in bold text in the above figure. As a typical finger vein system, the presented methodology is composed of four processes for enrollment and verification/identification stages. The flowchart starts by capturing finger vein image samples. For this purpose, a scanner device with NIR illumination (700–1000 nm) is often used. Later, a preprocessing step is required for segmentation of the ROI and to improve the quality of the image. From the final enhanced image, we compute the DAISY descriptor [71] for every pixel on all hierarchical levels, which represents stored finger vein samples in the database. During the verification/identification stage, the matching process is performed by CPM algorithm [38], resulting in the displacement matrices. Finally, the similarity score between finger vein samples is calculated on the basis of the uniformity degree of the displacements matrices, which is represented by the feature of the uniformity texture [66].

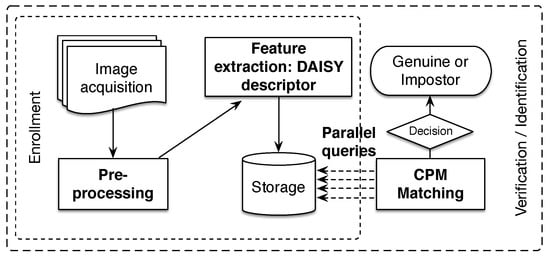

Figure 4.

General scheme of the proposed methodology for finger vein recognition. Our main contributions are highlighted in bold text.

3.1. Preprocessing of Finger Vein Images

Generally, the NIR illumination used during the image acquisition process causes low contrast and noise in the finger vein images. Therefore, the preprocessing step is very important to enhance the quality of the images. Thus, our first contribution aims to improve the image quality during the preprocessing step. After the ROI segmentation, we apply a block-local normalization and sharpening filtering, in contrast to other authors that use global normalization and histogram equalization. These procedures lead to enhance the local details of vein patterns while improving the accuracy results. Figure 5 shows examples of images obtained during the preprocessing procedures.

Figure 5.

The preprocessing procedure starts from the original image (a); finger edges and the middle line are determined for skew correction and correction of the ROI region (b) y (c); a local intensity normalization is performed over the ROI segmented image (d) y (e); and, finally, the normalized image is enhanced with a sharpening filtering (f).

ROI segmentation should find the same region of a finger vein image with sufficient finger vein patterns for feature extraction. Besides, a good accuracy of ROI extraction greatly improves the recognition performance of the system while reduces the computation complexity of subsequent processes. Further, we applied the ROI extraction algorithm proposed in the work by the authors of [72]. The method proposed by Yang et al. [72] is robust to finger displacement and rotation. First, we determine the boundaries of the finger by applying the Sobel edge detection algorithm [73]. We obtain the ROI candidate region by subtracting the binary finger edge image with the binarized image. Besides, the resulting finger edges are used to determine whether the finger is skewed or not, and the middle line between finger edges is used for skew correction of the image. Then, the interphalangeal area of the finger is detected by using a sliding window and it is employed to determine the height of ROI. Next, the left and right boundaries of the ROI are delimited by the internal tangents of finger edges. Finally, we standardize the size of the ROI segmented image in order to reduce the processing time during feature extraction and matching processes. For this purpose, we rescale the image to 64 × 96 pixels with bicubic interpolation.

Later, the intensity of the ROI segmented image is normalized because of another problem related to the illumination of the image acquisition procedure. The finger vein images present different intensity ranges as the thin fingers are more illuminated than the thick fingers; tissues and bones absorb a small amount of light, causing different intensity distributions. Most approaches use a global normalization technique to reduce the difference of intensities in the finger vein images [72,74,75]. Contrarily, we apply the block-local normalization proposed by Kočevar et al. [76]. This approach considers small local patches and not the entire image in order to average the intensities of pixels, which is more appropriate because of the varying of gray values in different areas of finger vein images.

Finally, the proposed preprocessing procedure focuses on highlighting or enhancing fine details of veins patterns due to the blurring effect is introduced in the image by the NIR acquisition process. In this regard, different approaches aim to enhance finger vein images by using complex techniques to avoid the influence of the noise that affects the above traditional methods [63,77,78]. However, typically most approaches use histogram equalization [74,79,80] or contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) [75,81,82]. HE-based methods increase the contrast of the finger vein region and highlight the vein texture details. Contrarily to other authors, we propose to apply a sharpening filter to increase the sharpness of finger vein images. Sharpening filtering increases the contrast between bright and dark regions to bring out features. Moreover, the image sharpening process is an edge-preserving filter that can remove noise completely and preserve the edge effectively.

In this paper, we use a kernel-based sharpening method,

where is the filtered image, I is the original image, and k is the kernel as a convolution matrix:

The sharpen kernel emphasizes differences in adjacent pixel values, thus blood vessel edges become more prominent. Besides, sharpening filtering is very suitable for corner feature extraction, and is also effective for block feature extraction. Furthermore, its major advantage is that can obtain similar results comparing to state-of-the-art techniques with lower computational complexity. This characteristic is very important in our proposal because we aim to develop an efficient finger vein technique.

In Section 4.4, we evaluate the impact of the preprocessing procedures introduced in our proposal, particularly block-local normalization and sharpening filtering.

3.2. Image Representation with DAISY Descriptor

In the work by the authors of [27], a SIFT descriptor is used to obtain dense correspondences based on the DenseSIFT algorithm [65], which is very time-consuming. Regarding this, Tola et al. [71] found that DAISY descriptor retains the robustness of SIFT while being more suitable for practical usage because it can be computed efficiently at the pixel level. Therefore, our proposed feature extraction process obtains an image representation with the DAISY descriptor.

The DAISY extraction process starts computing orientation maps, which each is convolved several times with Gaussian kernels of different sizes. As a result, each pixel location is represented by a vector of values from the convolved orientation maps for different sized regions. Formally, the DAISY descriptor as defined by the authors of [71], for each pixel location on a given image I, as the concatenation of vectors:

where is the normalized vector of the values at location in the convolved orientation maps by a Gaussian kernel of standard deviation ∑; is the location with distance R from in the direction given by j when the directions are quantized into T values; and Q represents the number of different circular layers.

It should be noted that the efficiency of DAISY is improved because convolutions operations are separable and can be implemented by using separate Gaussian filters. Thus, the descriptor avoids the computation of convolutions with a large Gaussian kernel by using several consecutive convolutions with smaller kernels. Furthermore, according to the authors of [71], the algorithm can be parallelized easily in both multicore and GPU parallel platforms.

Moreover, Tola et al. [71] studied the influence of the DAISY parameters on the performance and the computation time. Their analysis suggests the descriptor is relatively insensitive to parameters choice. Thus, the authors proposed the standard set of parameters in order to reduce the computation time while improving accuracy. In our approach, we use the DAISY implementation in OpenCV library [83] with the standard parameter settings fixed as Radius (R) = 15, Radius Quantization (Q) = 3, Angular Quantization (T) = 8, and Histogram Quantization (H) = 8.

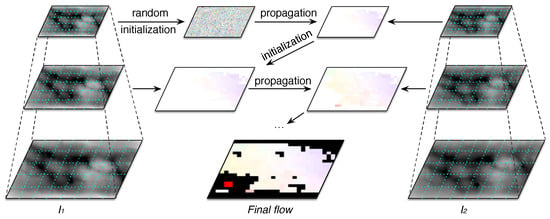

3.3. Matching Process Based on a Sparse Technique

The matching process of the proposed methodology is based on a sparse technique to obtain the displacement matrices between finger vein samples. We use the CPM algorithm [38] to compute sparse correspondences between patches of finger vein images to be compared. Contrary to the baseline method [27], which finds dense correspondences for each pixel of the image, the CPM algorithm [38] combines a random search strategy with a coarse-to-fine scheme for matching correspondences with larger patch size. Thus, the matching process implements a fast approximate structure in order to avoid finding correspondences of every pixel, which reaches a significant reduction of the computation time. An overview of the CPM matching is given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

General overview of the Coarse-to-fine PatchMatch (CPM) matching process for obtaining displacement flows.

Given two images, and , and a collection of seeds, , at position , the CPM matching process to compute the flow of each seed is defined as in the work by the authors of [38]:

where is the matching position for the seed of in .

The images are divided in nonoverlapping blocks and the seeds are the cross points of this regular grid, obtaining only one seed for each patch. Iteratively, the matching algorithm propagates the results from the neighborhood to the current seed in an interleaved manner. The propagation is performed in scan order on odd iterations and reversely on even iterations, only if the neighbor seeds have already been examined in the current iteration, as in the following equation,

where denotes the match cost between patch centered at in and the corresponding patch in with a displacement of , and is the set of neighbor seeds of . Next, a random search is performed by exponentially decreasing a maximum search radius . Thus, for the current seed , the algorithm tests candidate flows around the best flow .

CPM performs n iterations of the above matching process. Besides, in order to handle the ambiguity of small patches, the algorithm constructs a k-levels pyramid with a downsampling factor , for both and . This coarse-to-fine scheme is depicted in Figure 6, where the number of seeds is the same on each level and they preserve the same neighboring relation on each level. Thus, the algorithm finds the correspondences for each seed and it propagates the flow from top to bottom. The matching process randomly initializes the flow of the the top-level , and for each level, , the computed flow serves as initialization of the next level .

According to the evaluation by the authors of [36,38], the parameter set achieves the best accuracy performance while reduces the computation complexity. However, to find the optimized parameter settings of CPM for finger vein recognition, in Section 4.7, we analyze the impact of each parameter on the performance of the system.

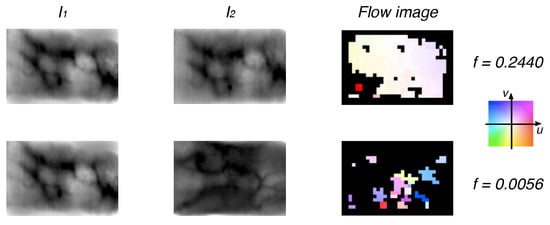

3.4. Decision Based on Displacement Uniformity

The final step of the proposed methodology is deciding whether the sample is genuine or impostor. Based on the key ideas proposed in the work by the authors of [27], this decision is determined by analyzing the uniformity of displacement matrices. Thereby, the flow previously obtained by the CPM matching process is represented as an image and the uniformity feature of the texture [66] is computed from the intensity histogram of the flow image.

Let h be the normalized histogram of the flow image, where indicates the number of pixels with a displacement i, the uniformity of the displacements is calculated as

This measure is maximum when all intensity levels are equal (maximally uniform) and decreases from there. Consequently, the final similarity degree between two finger vein samples to be compared lies between 0 and 1. Figure 7 shows two examples of genuine and impostor finger vein samples. Note that the number of matches is relatively large and uniform for genuine samples and, in contrast with the impostor samples, present a large number of no matches and a poorly uniformity. Thus, the function f is used as a similarity score to discriminate between genuine or impostor finger vein samples, which tends to be relatively high for genuine and has a tendency to zero for impostor matching.

Figure 7.

Examples of genuine (first row) and impostor (second row) finger vein samples with their respective flow images and the value of uniformity feature by using the CPM algorithm. The reference color pattern for displacement flow is shown; black color means no match.

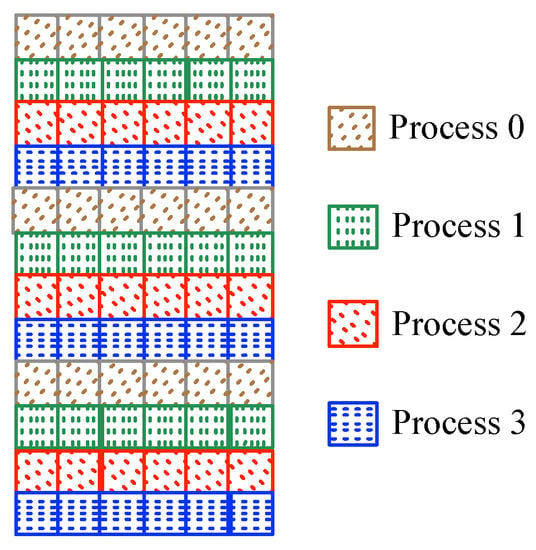

3.5. Matching Process under Multicore Platform

Our proposed methodology introduces some improvements concerning the baseline method [27], achieving a significant speed-up for the matching process, which is demonstrated in Section 4.5. Moreover, our proposal aims to accelerate the matching process of finger vein images in order to lead a real-time recognition. On this regard, we propose the implementation of a multithread parallel algorithm by using OpenMP [84] to compute the matching process under a multicore platform. Thus, in the proposed system, multiple similarity queries are executed by CPM under a multithread scheme, which is represented with multiple arrows between storage and the matching process in Figure 4.

In our approach, we use a master-worker scheme aiming to avoid synchronization problems between threads. As it is depicted in Figure 8, the proposed solution implements a task distribution scheme in a round-robin fashion for the allocation of similarity tests among the worker processes. Therefore, each worker process computes the similarity score between a tested sample and a subset of the stored templates. On the other hand, the master process manages the results given by workers and return the final result.

Figure 8.

Scheme of the implemented parallel task distribution in round-robin fashion, where each row represents a similarity test.

4. Performance Evaluation and Discussion

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the proposed methodology. For this purpose, we analyze the performance of our approach on two publicly available datasets, which are used in several works of the state-of-the-art. The details of both databases are described in the following.

The PolyU database [85] consists of finger vein images of 156 volunteers, both male and female. Approximately 93% of the subjects are under 30 years old. The images were captured over a period of eleven months in two sessions separated by an interval between one and six months. In each session, the volunteers gave 6 samples of images of the index finger and middle finger of the left hand. As in the baseline method [27], we only use finger vein images captured in the first session, consisting of 1872 images.

The SDUMLA-HMT database [86] contains a subset of finger vein images, which is used as the second database and we reference as SDU-MLA dataset. The dataset was captured from both hands of 106 subjects. Each individual contributes 6 samples from the index, middle, and ring finger, with 36 finger vein images per individual, for a total of 3816 images. This database is more challenging because it was obtained in an uncontrolled way, and the reported recognition performances are lower than those in the PolyU database.

In our experiments, we analyze the recognition performance of the proposed approach in verification and identification modes. Aiming to make an equivalent comparison, we use the same experimentation settings for interclass and intraclass matching reported in [27]. Besides, we use the decimal format to report all the experimentation results, both in charts and tables, except in Section 4.1, where equal error rates (EER) values are reported in percent in order to obtain a clear representation of the charts. Furthermore, we compare different sparse matching methods in order to analyze their performance for finger vein recognition.

All the experiments were executed on a dedicated server with the hardware characteristics reported in Table 2. We use the original source codes provided by authors for DenseSIFT [65], CPM [38], DeepMatching [37], and SparseFlow [35]. We implements sequential and multicore versions of the system by using C++ with OpenCV [87] and OpenMP [84] libraries.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the server used for the experiments.

4.1. Analysis of Parameter Settings of CPM

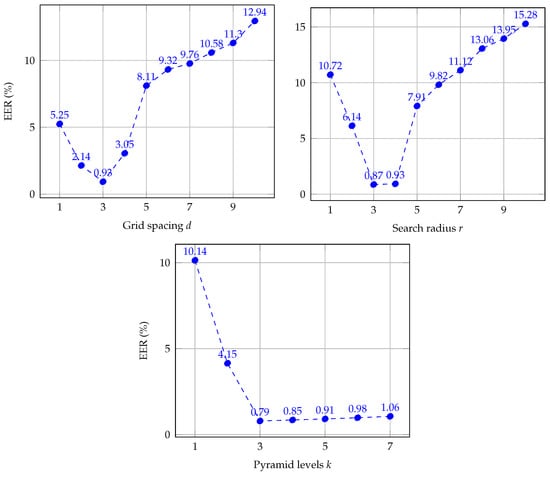

In the works by the authors of [36,38], the authors of CPM analyzed the parameter sensitivity of the algorithm. They found the parameter settings achieved the best accuracy results while also reducing computation complexity. However, to get better performance and to decrease the execution time of CPM for finger vein recognition, we optimize the parameter set for this task. For this purpose, we empirically vary the parameter setting each by one and maintaining the rest as proposed by the authors of [36,38]. Figure 9 summarizes the results for each parameter, we report the EER on a training set of finger vein images from both databases. The training set was randomly selected using 20% of each database. We did not use each dataset separately because both do not have a large number of subjects. Thus, the obtained parameter settings have been optimized for finger vein recognition tasks in general. Different from the rest of the experiments, EER (equal error rate) values are reported in percent (%), in order to obtain a clear representation of the charts.

Figure 9.

Results of the evaluation of the influence of different parameters setting of CPM for finger vein recognition.

As it is depicted in Figure 9, the results are equivalent to the evaluation made by the authors of [36,38]. The use of a small grid spacing improves the performance, resulting in the best. It should be noted that as r increases, the values of EER become progressively worse, whereas for small values of r, the results also lie to deteriorate. Thus, we find the best results for , which is smaller than proposed by authors of CPM due to finger vein images are also smaller. On the other hand, the effect of varying the number of hierarchical levels, k, increases the quality because the propagation is more discriminative on higher levels. In this sense, a value of obtains the smallest results of EER. Regarding the number of iterations n, a larger n leads to more accurate matching but a higher computation time. Hence, we set , which is equal to default parameter settings, because it is optimal for converging of the matching process. Concerning the influence in computation time, parameters d and n affect the complexity of the matching methods, for small and large values, respectively. However, the optimal values obtained in this experiment for both parameter present a balance between accuracy and time-consuming. As a result of the evaluation in this section, we found the optimal parameter set, , for both vascular databases, which is the parameter setting that we use in the following experiments.

4.2. Experimentation in Verification Mode

The accuracy results of our method are contrasted with the baseline algorithm [27] in verification mode. To evaluate the biometric performance of our system a considerable high number of genuine and impostor test were performed with the proposed method and all similarity scores were saved. Then, by varying a score threshold for the similarity scores, we calculated FAR (false acceptance rate) and FRR (false rejection rate) as the proportion of times the system grants access to an unauthorized person, and the proportion of times it denied access to an authorized person, respectively. Besides, EER is used to determine the threshold for its FAR and FRR are equal. These three metrics are widely used in the literature and they are very important when comparing two systems because the more accurate one would show lower FRR at the same level of FAR.

For this experiment, we compute a set of matching scores in order to establish the threshold for intraclass and interclass matching. For PolyU database, there are 4680 () intraclass and 3,493,152 () interclass matching pairs. For SDU-MLA dataset, there are 9540 () intraclass and 14,538,960 () interclass matching pairs.

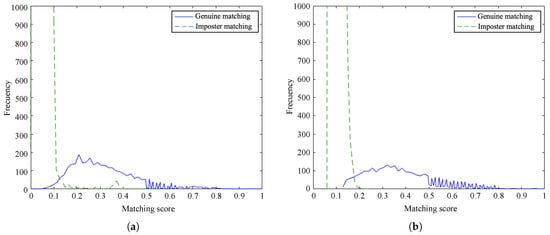

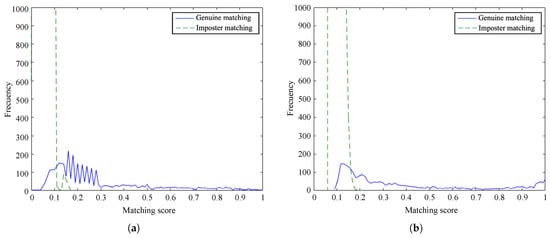

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the frequency of the obtained matching scores for genuine and imposter matching by the proposed method and the baseline algorithm for PolyU database and SDU-MLA dataset, respectively. It is noticeable that the overlap between genuine and imposter matching scores is larger for our method than the baseline on both databases. However, the matching scores of the proposed method are more dense, obtaining scores closer to 0 for imposter matching and being smaller than scores of the baseline. In spite of this, it is appreciable that there are not important differences between the distributions of scores of the methods. These results suggest that our approach accurately recognizes genuine finger vein samples while distinguishing impostor samples.

Figure 10.

Distribution of matching scores on the PolyU database: (a) proposed method and (b) baseline method.

Figure 11.

Distribution of matching scores on the SDU-MLA dataset: (a) proposed method and (b) baseline method.

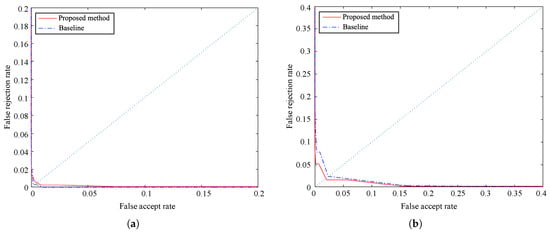

The accuracy results of our method are contrasted with the baseline algorithm [27]. Figure 12 depicts ROC curves obtained for FAR (false acceptance rate) and FRR (false rejection rate) results on both databases. Besides, Table 3 compares the results of EER (equal error rate), FRR at-zero-FAR, and FAR at-zero-FRR.

Figure 12.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves obtained from false acceptance rate (FAR) and false rejection rate (FRR) of both methods on (a) PolyU database and (b) SDU-MLA dataset.

Table 3.

Comparison of verification results on the databases.

The results of FAR and FRR show the high accuracy of the proposed method. The EERs of the proposed method are 0.0049 and 0.0185 on the PolyU database and SDU-MLA dataset, respectively. Although the previous values are not better than those of the baseline, they demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposal that even obtains a slightly lower EER on SDU-MLA dataset. Besides, the results of FRR at-zero-FAR and FAR at-zero-FRR of the proposed method are both slightly higher on both databases, with the FAR at-zero-FRR being very close to 1.

Even though the experimental results show that CPM achieves high accuracy for finger vein recognition, the discriminability of the baseline algorithm is not improved, but similar results are obtained. Thus, these results in verification mode task indicate that CPM is a good alternative to the time-consuming dense matching proposed by Meng et al. [27], which is our main motivation and contribution.

4.3. Experimentation in Identification Mode

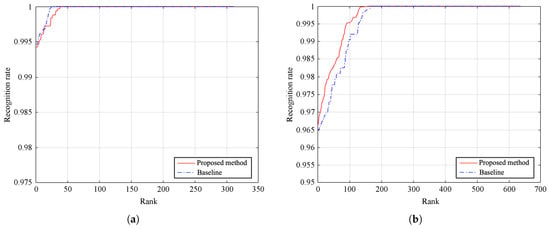

In this section, the recognition performance of our approach is evaluated in the identification mode. In the identification mode, a biometric system computes a similarity score for each pair of a testing sample and every known template in the database. For this purpose, we implement the same experimentation settings proposed in the work by the authors of [27]. The first three finger vein images of each person are used as testing samples and randomly selected one finger vein image from the remaining three images of each person as a template of the database. Therefore, there are 312 () templates and 292,032 () tests of similarity on the PolyU database, while on SDU-MLA dataset, there are 636 () templates and 1,213,488 () tests of similarity.

Figure 13 depicts the cumulative match curves of the method and the baseline. We compute the ranking of each testing sample by descending sorting of the similarity scores. Besides, we compare the identification accuracy of both methods in Table 4. As it can be seen, the proposed approach improves baseline results, achieving average recognition rates of 99.43% and 96.64% on PolyU database and SDU-MLA dataset, respectively. Besides, the performance comparison shows that modifying the baseline method, by using CPM instead of DenseSIFT, we can obtain similar values of accuracy for the recognition task. Moreover, taking into account the results reported in Section 4.5, we consider that the small differences of accuracy are almost negligible compared to the improvement in time efficiency. All reported results were obtained by averaging 10 repetitions of the experiments in order to obtain an unbiased result.

Figure 13.

Cumulative match curves obtained for identification task by both methods on (a) PolyU database and (b) SDU-MLA dataset.

Table 4.

Comparison of identification results on the databases.

As our main motivation is to develop a finger vein recognition method for real-time individual identification, it should be discussed the difficulties and limitations faced in the identification mode. In our humble opinion, there are different factors that limit more extensive use of this technology for massive individual identification, from simple to more technical reasons. These factors also preclude researchers to collect databases with high quality containing a high number of individuals in order to be used for identification tasks. Currently, the publicly available databases are only in the order of hundreds of subjects. Besides, there are not a robust synthetic generator of vein images contrarily to other traits such as fingerprint. Moreover, it should be mentioned that its major disadvantage regarding being widely used for individuals identification is because vein images must be caught in a living body. Although it avoids some fraud techniques, this issue does not allow identify a dead person for example in case of a disaster differently to fingerprint. All the aforementioned reasons make the wider use of vein-based biometrics for massive identification of people difficult.

In the identification mode, a biometric system requires to calculate a matching or similarity score for each 1:N pair (unknown sample:every stored sample) by performing an exhaustive search in the database. Then, the identity of the most similar template is used as the identity of the unknown sample. Therefore, the security and convenience of the system are important requiring high accuracy and fast response times. Regarding that, we compute a considerable number of similarity tests satisfying both requirements with a recognition rate above to 99% and an average processing time of 70.89 ms.

In our experimentation scheme, we used three finger vein images per person as testing samples and only one finger vein image per person as a template sample. In general, this is, practically, a rather challenging experimental environment, which simulates practical application configurations because, in many real applications, there are usually not many samples available per subject. However, the main difficulty in the evaluation was the number of subjects of the databases to evaluate the scalability of the system. Theoretically, on the basis of the algorithm implemented in our methodology, our approach should be suitable for GPU parallel programming. Then, we have proposed as future work in the conclusions, performing further studies in order to evaluate the scalability of our method for massive identification of people. Nevertheless, on the basis of obtained results, our work contributes to obtaining a fast and effective finger vein recognition technique for real-time individuals identification, able to use a large database.

4.4. Impact of Preprocessing Procedures on the Accuracy

The proposed preprocessing procedure in our methodology includes techniques as ROI segmentation, a block-local intensity normalization, and a sharpening filtering process. These techniques aim to enhance the quality of finger vein samples in order to improve the accuracy of the matching process. In this experiment, we evaluate the impact of the preprocessing procedures introduced in our proposal, particularly block-local normalization and sharpening filtering. Table 5 compares the accuracy results of the proposed method with and without each preprocessing procedures, but keeping the others. Also, we evaluate our method by varying normalization and enhancement processes by using global normalization and CLAHE equalization for each process, respectively, instead of the proposed techniques and leaving the others as default. The accuracy results are presented as EER on both databases with the same evaluation protocol of our verification experiment.

Table 5.

Comparison of the impact of preprocessing procedures on the accuracy of the proposed methodology. The second column (without any (ROI)) means that we use only the ROI images without any extra preprocessing technique.

The obtained results clearly show that preprocessing procedures are very important for improving recognition accuracy. Regarding the normalization step, it is noticeable that global normalization is worse than local normalization. It proves that considering the entire image with global normalization is less appropriate than taking a local variation of intensities values as in local normalization. Besides, although there are not large differences between sharpening filtering and CLAHE equalization, the sharpening procedure obtains better results preserving the fine details of finger vein patterns.

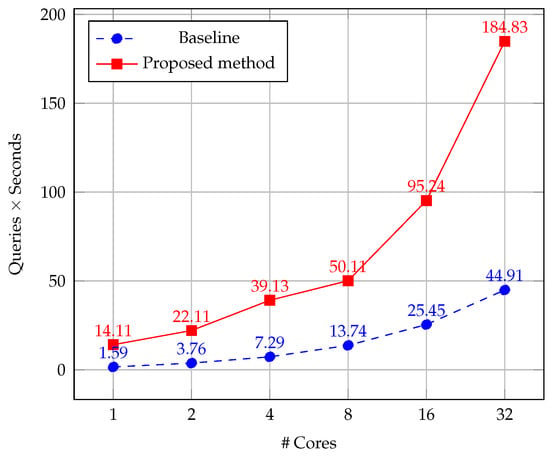

4.5. Evaluation of the Impact of the CPM Algorithm on the Time Efficiency

Our method uses CPM as a sparse matching algorithm, contrarily to the baseline [27] that uses DenseSIFT as a dense matching technique. In this section, we evaluate the impact of CPM on the time efficiency of the system pipeline. We examine how much faster is our approach than the baseline method in Table 6, comparing the execution time of each process. Besides, in Figure 14 we represent the effect of our multicore implementation on the computed queries per second by varying the number of processing cores. For this purpose, we average the results of 10 repetitions of the test on a set of 1296 images from PolyU database and SDU-MLA dataset.

Table 6.

Results of the execution time of each process of the system. All times are given in milliseconds (ms).

Figure 14.

Comparison of computed queries per seconds by varying the number of processing cores. Number 1 represents the sequential version.

From results, it is highlighted that our method reaches an overall speed-up of up to 9×. On this regard, it should be noticed that the execution time of our sparse matching process is equal to 0.08 ms, whereas the dense matching of the baseline method is 7237 times higher. However, the computation time of our feature extraction is slightly higher than the baseline. It can be explained due to we use the OpenCV [87] implementations for computing both descriptors, which are not the same used by Tola et al. [71], whose results found the DAISY descriptor can be computed faster than SIFT. Nevertheless, this aspect is not a matter because the impact on the total time is small. Besides, it should be noted the DAISY algorithm is suitable to be parallelized, which we will study in the future.

As it can be seen in Figure 14, the proposed parallel scheme linearly increases the computed queries per second computed with increasing of processing cores. On the contrary, the baseline algorithm presents a smaller improvement considering the increasing of processing cores. This behavior is explained by the fact that the algorithm enables very efficient memory access by combining CPM and DAISY descriptor. Besides, CPM implements a coarse-to-fine scheme with a random search on a sparse grid structure, instead of dense correspondences in the baseline method. The aforementioned advantages suggest that our proposal is also quite suitable for GPU parallel programming, which will be explored in future work to take advantage of the GPU computation for massive individuals identification.

4.6. Evaluation of Different Sparse Matching Methods

Following, we evaluate the performance results of our proposal by using CPM against two different sparse matching algorithms: DeepMatching [37] and SparseFlow [35]. For this purpose, we executed our proposed approach by modifying feature extraction and matching processes with these algorithms. Table 7 compares the results of each variation against our proposal, given by EER, Rank-one recognition rate, and the computation time of the matching process, which are measured as in the previous experiment.

Table 7.

Performance results of the proposed approach by modifying the sparse matching algorithm. The first column represents methods as: CPM [38], DeepMatching [37], and SparseFlow [35].

The comparison of results shows that CPM obtains the best performance on both databases. The main reason why CPM outperforms DeepMatching and SparseFlow is that it can produce more matches than them by default. Besides, it should be highlighted that computation times of sparse matching methods are lower than the dense matching used in the work by the authors of [27]. Furthermore, recognition accuracy of DeepMatching [37] and SparseFlow [35] are higher than some state-of-the-art approaches, see Table 7. The above results demonstrate that sparse matching methods are a good alternative for finger vein recognition based on displacement information, being the CPM algorithm the best of the studied methods.

4.7. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Approaches

In this section, we compare the recognition performance obtained by our approach against state-of-the-art approaches. Table 8 summarizes the results of EER and Rank-one recognition rate achieved by methods based on different techniques and with experimentation on the same databases. Five types of approaches for finger vein recognition are compared, and they are identified as follows.

Table 8.

Comparison of our approach against other methods of the state-of-the-art.

- LBP-based approaches as local binary pattern (LBP) [42] and local linear binary pattern (LLBP) [43];

- network-based methods such as mean curvature (MeanC) [50], maximum curvature (MaxC) [51], repeated lines tracking (RLT) [26], and Even Gabor filtering with morphological processing (EGM) [85];

- minutiae-based techniques include scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) [53] and minutiae matching based on singular value decomposition (SVDMM) [45];

- CNN-based approaches such as fully connected network (FCN) [57], CNN with Supervised Discrete Hashing (CNN+SDH) [58], two-stream CNN (two-CNN) [59], and the very deep CNN (deeper-CNN) proposed in the work by the authors of [28]; and

- deformation-based methods as the detection and correction method (DFVR) proposed by the authors of [61] and the baseline method [27].

From the results in Table 7, it can be seen that the recognition performance of deformation-based methods is significantly more accurate than the rest on both databases. The results of the proposed approach are only outperformed by the baseline on PolyU database, which as it has seen previously, the results are slightly similar while our method improves the time efficiency of the baseline with a speed-up of 9×. Besides, the EER of the two-CNN approach proposed in the work by the authors of [59] is better than our method on SDU-MLA dataset, but its average matching time is 171 ms. It should be noticed that deep learning approaches have been successfully applied and enhance finger vein recognition methods in recent years with remarkable results. Despite that, the performance of CNN-based finger vein recognition methods should be enhanced by employing large datasets. Also, these techniques require a time-consuming training process, which is not needed in the proposed methodology.

The proposed approach has two main advantages against state-of-the-art competitors, which improve their limitations regarding deformations and time efficiency. First, our proposal considers the displacement produced by deformations as discriminative information, and, contrary to other methods, their recognition performances are affected by deformations trying to reduce its influence. Secondly, our method uses an accurate and efficient matching process based on the CPM algorithm, which improves other image matching techniques in time efficiency with equivalent accuracy of the correspondences. CPM implements a fast approximate structure in order to avoid finding correspondences of every pixel, which reaches a significant reduction of the computation time. Besides, the foundation of CPM is closely related to the two key ideas that allow distinguishing between genuine and imposter samples based on the generalized symmetry concept [29] and the ideas proposed by Meng et al. [27]. Since the geometric structure of finger vein images remains invariant under the affine transformations produced during the acquisition process, particularly in the neighborhood of pixels, it is not required to find the correspondences of every pixel of the images. The aforementioned characteristics allow that the proposed approach outperforms other methods of the state-of-the-art.

Aiming to provide a statistical analysis of the results regarding the state-of-the-art, we followed the recommendations of Demšar [88] and the extensions presented in the work by the authors of [89] for the computations of adjusted p-values. Note that some works show their experimental results on self-generated datasets, which do not allow to make an equivalent comparison. Thus, for this purpose, we only consider those works with reported results on both studied databases. Unfortunately, this issue made impossible for us to consider CNN-based approaches in our statistical analysis. In spite of that our results are slightly similar to CNN-based approaches. Thus, there should not have significant differences between our method and them, while our approach outperforms them in time efficiency.

First, we used the Friedman test to prove the null hypothesis that all the methods obtained the same results on average. When the Friedman test rejected the null hypothesis, we used the Bonferroni–Dunn test to know if our method considerably outperforms the next ranked method. Finally, we use Holm’s step-down procedure to complement the above multicomparison statistical analysis.

Table 9 shows the ranking of each approach based on EER results for both databases. In this scenario, we analyze the results to observe and detect considerable differences among compared methods. The Friedman test rejected the null hypothesis with . After that, we applied the post hoc Bonferroni–Dunn test at to recognize which approach performed equivalently to our method, which is the best ranked. Taking account the work by the authors of [88], the performance of two approaches is considerable different if their corresponding ranks differ by at least the critical difference, calculated as

where is the critical value based on the Studentized range statistic, N is the number of studied datasets, and k is the number of algorithms to compare. Based on the criteria, the Bonferroni–Dunn test finds significant differences between our approach and SIFT method [53], whereas others, such as LLBP [43], LBP [42], and EGM [85], are near to the boundary of the critical difference. Aiming to contrast the above results, we report the results of the Holm’s step-down procedure in Table 10. The Holm’s procedure at rejects those hypotheses that have a p-value , finding significant differences with SIFT and LLBP. Also, it confirms that the proposed approach is slightly better than the other studied methods, but it is not statistically superior. It should be highlighted that the same tests based on recognition rate produced the same results.

Table 9.

Average rankings of analyzed methods based on equal error rates (EER) results for both databases.

Table 10.

Methods sorted by p-value and adjusting of coming from Holm algorithm at .

From the previous results, we can conclude that our methodology achieves better results regarding the state-of-the-art methods on the evaluated databases, finding statistical differences respect to non-deformation-based approaches, which is significant in some cases. Thus, the results provide evidence that the sparse-matching approach introduced in this paper is suitable for finger vein recognition. Moreover, it also improves the time efficiency of the baseline algorithm with a considerable speed-up of greater than 9×.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduce an optimized sparse matching algorithm as an effective and efficient alternative for finger vein recognition based on deformation information. Our methodology proposes preprocessing techniques that are used for robust ROI selection with a block-local intensity normalization and a sharpening filtering process, aiming to improve and preserve the local details in the vein patterns. For the feature extraction and matching processes, we combine the DAISY descriptor and the CPM algorithm (an optimized for a finger vein database) under a multicore platform, aiming to reduce the computation time and to increase the number of processed queries per second of the recognition pipeline. For this purpose, we implemented a master-worker parallel scheme based on a task distribution algorithm in a round-robin manner for the execution of similarity tests.

The main contribution of our proposal is reducing the execution time of the matching process on finger vein images keeping high efficiency. We present a fast finger vein recognition method for real-time individuals identification that can be used for individual massive identification using a large database. Experimental results on well-known databases show that our proposed approach achieves the state-of-the-art results of deformation-based techniques, finding statistical differences respect to non-deformation-based approaches. Moreover, the presented technique does not require a time-consuming training process with a large number of training images like CNN-based approaches. In terms of time efficiency, our method overcomes the limitations of the baseline method, achieving real-time recognition in only 70.89 ms with a significant speed-up of greater than 9×. Besides, the experiments show that our method is highly suitable for being executed under a multicore platform.

As future work, we propose to evaluate the scalability of our method under hybrid parallel platforms. Thus, we will explore different implementations of the DAISY descriptor and the CPM algorithm under a GPU parallel platform, in order to use multiples cores of a GPU on a real-world application for massive individuals identification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, R.H.-G. and M.M.; software and validation, C.R. and R.H.-G.; formal analysis, R.H.-G. and R.J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.-G. and W.E.S.-S.; writing—review and editing, R.H.-G., R.J.B., P.G., and F.E.F.; supervision, R.J.B. and M.M.; project administration, R.J.B.; funding acquisition, R.J.B. and M.M.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Project CONICYT FONDEF/ Cuarto Concurso IDeA en dos Etapas del Fondo de Fomento al Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico, Programa IDeA, FONDEF/CONICYT 2017 ID17i10254.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jain, A.K.; Ross, A.; Pankanti, S. Biometrics: A Tool for Information Security. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2006, 1, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode Intelligence. Biometrics—The Must-Have Tool for Payment Security. 2015. Available online: https://www.goodeintelligence.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Goode-Intelligence-White-Paper-Biometrics-the-must-have-tool-for-payment-security.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- IBM Security. Future of Identity Study. 2018. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/account/reg/usen/signup?formid=urx-30345 (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Unar, J.; Seng, W.C.; Abbasi, A. A review of biometric technology along with trends and prospects. Pattern Recognit. 2014, 47, 2673–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Ross, A.; Prabhakar, S. An introduction to biometric recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2004, 14, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Kumar, A. Biometric Recognition: An Overview. In Second Generation Biometrics: The Ethical, Legal and Social Context; Mordini, E., Tzovaras, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta, D.; Galar, M.; Triguero, I.; Paternain, D.; García, S.; Barrenechea, E.; Benítez, J.M.; Bustince, H.; Herrera, F. A survey on fingerprint minutiae-based local matching for verification and identification: Taxonomy and experimental evaluation. Inf. Sci. 2015, 315, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.S.; Devi, B.S.; Reddy, M.J.; Gunjan, V.K. A Survey of Fingerprint Recognition Systems and Their Applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communications and Cyber Physical Engineering 2018, Hyderabad, India, 24–25 January 2018; pp. 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Abate, A.F.; Nappi, M.; Riccio, D.; Sabatino, G. 2D and 3D face recognition: A survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2007, 28, 1885–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Z.; Muhammad, N.; Bibi, N.; Ali, T. A review on state-of-the-art face recognition approaches. Fractals 2017, 25, 1750025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugman, J. How iris recognition works. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2004, 14, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Gudasalamani, S.; Iyer, N.C. A Survey on Iris Recognition System. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT), Chennai, India, 3–5 March 2016; pp. 2207–2210. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, A.; Zhang, D.; Kamel, M. A survey of palmprint recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2009, 42, 1408–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Du, X.; Zhong, K. Decade progress of palmprint recognition: A brief survey. Neurocomputing 2019, 328, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.; Vabishchevich, P.; Huggins, M.; Ardis, P.; Battles, B.; Stauffer, A. Survey and Evaluation of Acoustic Features for Speaker Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 22–27 May 2011; pp. 5444–5447. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.H.; Hasan, T. Speaker recognition by machines and humans: A tutorial review. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2015, 32, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheed, K.; Liu, H.; Yang, G.; Qureshi, I.; Gou, J.; Yin, Y. A systematic review of finger vein recognition techniques. Information 2018, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, S.C.; Ibrahim, M.; Yakno, M. A Review: Personal Identification Based on Palm Vein Infrared Pattern. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. 2018, 10, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, C.; Wang, L.; Phoha, V.V. A survey on gait recognition. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, P.; Ross, A. Biometric recognition by gait: A survey of modalities and features. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2018, 167, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deore, M.R.; Handore, S.M. A Survey on Offline Signature Recognition and Verification Schemes. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Industrial Instrumentation and Control (ICIC), Pune, India, 28–30 May 2015; pp. 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kutzner, T.; Pazmiño-Zapatier, C.F.; Gebhard, M.; Bönninger, I.; Plath, W.D.; Travieso, C.M. Writer Identification Using Handwritten Cursive Texts and Single Character Words. Electronics 2019, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pungila, C.; Negru, V. Accelerating DNA Biometrics in Criminal Investigations Through GPU-Based Pattern Matching. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Soft Computing Models in Industrial and Environmental Applications, San Sebastián, Spain, 6–8 June 2018; pp. 459–468. [Google Scholar]

- Hashiyada, M. DNA biometrics. In Biometrics; Yang, J., Ed.; InTech: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kono, M.; Ueki, H.; Umemura, S. Near-infrared finger vein patterns for personal identification. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 7429–7436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, N.; Nagasaka, A.; Miyatake, T. Feature extraction of finger vein pattern based on repeated line tracking and its application to personal identification. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2004, 15, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xi, X.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y. Finger vein recognition based on deformation information. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2018, 61, 052103:1–052103:15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Piciucco, E.; Maiorana, E.; Campisi, P. Convolutional Neural Network for Finger Vein-Based Biometric Identification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 14, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvas, G. Interdisciplinary Application of Symmetry Phenomena. In Aesthetics of Interdisciplinarity: Art and Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hitachi LTD. Finger Vein Authentication Technology—Applications Report. 2014. Available online: http://www.hitachi.co.jp/products/it/veinid/global/index.html (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Nakamaru, Y.; Oshina, M.; Murakami, S.; Edgington, B.; Ahluwalia, R. Trends in Finger Vein Authentication and Deployment in Europe. Hitachi Rev. 2015, 64, 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, Y.; Sawada, A.; Kaneko, S.; Nakamaru, Y.; Ahluwalia, R.; Kumar, D. Global Deployment of Finger Vein Authentication. Hitachi Rev. 2012, 61, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hitachi LTD. Use of Finger Vein Authentication for Population-based Surveys in Developing Countries. Hitachi Rev. 2013, 62, 456–462. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Himaga, M.; Inoue, T. Finger Vein Authentication Applications in the Field of Physical Security. Hitachi Rev. 2018, 67, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. Sparse Flow: Sparse Matching for Small to Large Displacement Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–9 January 2015; pp. 1100–1106. Available online: http://www.vision.ee.ethz.ch/~timofter/ (accessed on 5 January 2019).

- Hu, Y.; Song, R.; Li, Y. Efficient Coarse-to-Fine Patchmatch for Large Displacement Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 5704–5712. [Google Scholar]

- Revaud, J.; Weinzaepfel, P.; Harchaoui, Z.; Schmid, C. Deepmatching: Hierarchical deformable dense matching. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2016, 120, 300–323. Available online: http://lear.inrialpes.fr/src/deepmatching/ (accessed on 5 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Song, R.; Rao, P.; Wang, Y. Coarse–to–Fine PatchMatch for Dense Correspondence. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2018, 28, 2233–2245. Available online: https://github.com/YinlinHu/CPM (accessed on 5 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- Ezhilmaran, D.; Joseph, P.R.B. A Study of Feature Extraction Techniques and Image Enhancement Algorithms for Finger Vein Recognition. Int. J. Pharmtech Res. 2015, 8, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.C.; Lee, H.C.; Park, K.R. Finger vein recognition using minutia–based alignment and local binary pattern-based feature extraction. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2009, 19, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Kang, B.J.; Lee, E.C.; Park, K.R. Finger vein recognition using weighted local binary pattern code based on a support vector machine. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2010, 11, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.C.; Jung, H.; Kim, D. New finger biometric method using near infrared imaging. Sensors 2011, 11, 2319–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosdi, B.A.; Shing, W.C.; Suandi, S.A. Finger vein recognition using local line binary pattern. Sensors 2011, 11, 11357–11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Xi, X.; Yin, Y. Finger vein recognition based on (2d)2pca and metric learning. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 324249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y.; Wang, S. Singular value decomposition based minutiae matching method for finger vein recognition. Neurocomputing 2014, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, J.; Nie, Y. Finger vein recognition based on dual-sliding window localization and pseudo-elliptical transformer. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 64, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; He, X.; Yao, X.; Li, H. Finger vein verification based on the curvature in Radon space. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 82, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y.; Xiao, R. Finger vein recognition based on local directional code. Sensors 2012, 12, 14937–14952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.C.; Xie, S.J.; Park, D.S. Finger vein recognition using optimal partitioning uniform rotation invariant LBP descriptor. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2016, 2016, 7965936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Kim, T.; Kim, H.C.; Choi, J.H.; Kong, H.J.; Lee, S.R. A finger vein verification system using mean curvature. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2011, 32, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, N.; Nagasaka, A.; Miyatake, T. Extraction of finger vein patterns using maximum curvature points in image profiles. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2007, 90, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Qin, H.; Cui, Y.; Hu, X. Finger vein image recognition combining modified hausdorff distance with minutiae feature matching. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2009, 1, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Yin, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, Y. Rotation Invariant Finger Vein Recognition. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Biometric Recognition, Shenzhen, China, 28–29 October 2012; pp. 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.D.; Liu, C.T. Finger vein pattern identification using principal component analysis and the neural network technique. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5423–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y.; Meng, X. Finger vein recognition with personalized feature selection. Sensors 2013, 13, 11243–11259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.D.; Liu, C.T. Finger vein pattern identification using svm and neural network technique. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 14284–14289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; El-Yacoubi, M.A. Deep representation-based feature extraction and recovering for finger vein verification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 1816–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Kumar, A. Finger vein identification using convolutional neural network and supervised discrete hashing. In Deep Learning for Biometrics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Kang, W. A novel finger vein verification system based on two-stream convolutional network learning. Neurocomputing 2018, 290, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y.; Zhou, L. A Survey of Finger Vein Recognition; Technical Report; School of Computer Science and Technology, Shandong University: Jinan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, L.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y. Geometric Shape Analysis based Finger Vein Deformation Detection and Correction. Neurocomputing 2018, 311, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.C.; Park, K.R. Image restoration of skin scattering and optical blurring for finger vein recognition. Opt. Laser Eng. 2011, 49, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shi, Y. Finger–vein ROI localization and vein ridge enhancement. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2012, 33, 1569–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yuen, J.; Torralba, A. SIFT Flow: Dense Correspondence across Scenes and Its Applications. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 33, 978–994. Available online: http://people.csail.mit.edu/celiu/SIFTflow/ (accessed on 5 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E.; Eddins, E.L. Digital Image Processing Using MATLAB; Pearson Education Inc.: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eilertsen, G.; Forssén, P.E.; Unger, J. BriefMatch: Dense Binary Feature Matching for Real-Time Optical Flow Estimation. In Proceedings of the Scandinavian Conference on Image Analysis, Tromsø, Norway, 12–14 June 2017; pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Leordeanu, M.; Zanfir, A.; Sminchisescu, C. Locally Affine Sparse-to-Dense Matching for Motion and Occlusion Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 1721–1728. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, C.; Hernández-García, R.; Barrientos, R.J. Individuals Identification Using Finger Veins under a Multi-core Platform. In Proceedings of the 2018 37th International Conference of the Chilean Computer Science Society (SCCC), Santiago, Chile, 5–9 November 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-García, R.; Barrientos, R.J.; Rojas, C.; Mora, M. Individuals Identification Based on Palm Vein Matching under a Parallel Environment. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tola, E.; Lepetit, V.; Fua, P. Daisy: An efficient dense descriptor applied to wide-baseline stereo. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 32, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Yang, G.; Yin, Y.; Xiao, R. Sliding window-based region of interest extraction for finger vein images. Sensors 2013, 13, 3799–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Gao, W.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z. An Improved Sobel Algorithm Based on Median Filter. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Mechanical and Electronics Engineering (ICMEE), Kyoto, Japan, 1–3 August 2010; Volume 1, p. V1-88. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.G.; Lee, E.J.; Yoon, G.J.; Yang, S.D.; Lee, E.C.; Yoon, S.M. Illumination Normalization for SIFT Based Finger Vein Authentication. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Visual Computing, Crete, Greece, 29–31 July 2012; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Basu, S.; Basu, S.; Nasipuri, M. ARTeM: A new system for human authentication using finger vein images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 5857–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kočevar, M.; Kotnik, B.; Chowdhury, A.; Kačič, Z. Real-time fingerprint image enhancement with a two–stage algorithm and block–local normalization. J.-Real-Time Image Process. 2017, 13, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shi, Y. Towards finger vein image restoration and enhancement for finger vein recognition. Inf. Sci. 2014, 268, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Jia, G.; Yang, J. Finger Vein Recognition Based on Weighted Graph Structural Feature Encoding. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Biometric Recognition, Urumchi, China, 28–29 October 2018; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Yue, X. Contact-free palm-vein recognition based on local invariant features. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Yang, L.; Yin, Y. Learning discriminative binary codes for finger vein recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 66, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauba, C.; Reissig, J.; Uhl, A. Preprocessing Cascades and Fusion in Finger Vein Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference of the Biometrics Special Interest Group (BIOSIG), Darmstadt, Germany, 10–12 September 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Lu, Y.; Yoon, S.; Yang, J.; Park, D. Intensity variation normalization for finger vein recognition using guided filter based singe scale retinex. Sensors 2015, 15, 17089–17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV. The OpenCV Reference Manual—cv::xfeatures2d::DAISY Class Reference. Itseez, 2014. Version 3.4.6. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/3.4.6/d9/d37/classcv_1_1xfeatures2d_1_1DAISY.html#details (accessed on 5 January 2019).