Updates on Antibody Drug Conjugates and Bispecific T-Cell Engagers in SCLC

Abstract

1. Introduction

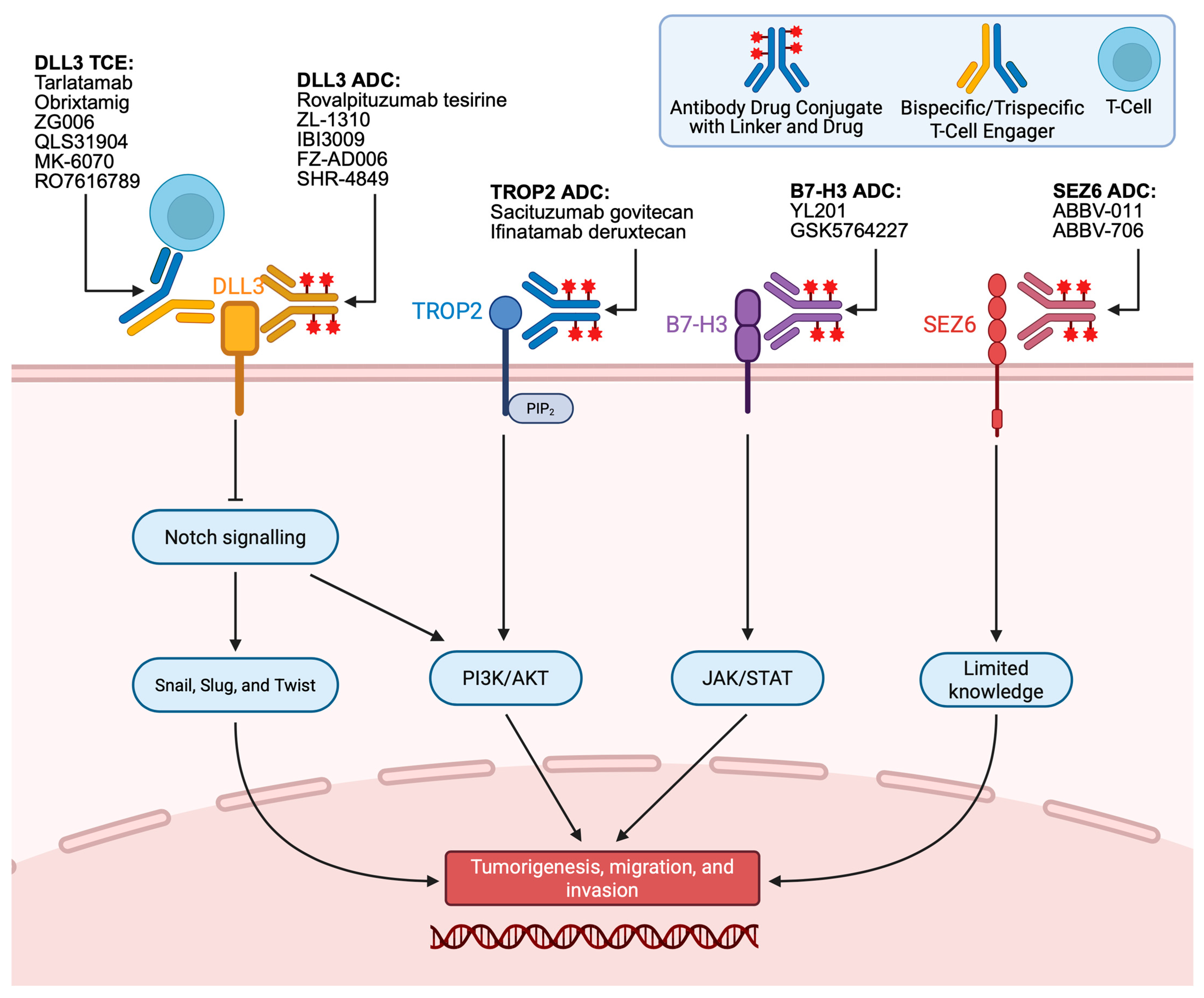

2. DLL3 T-Cell Engagers

3. DLL3 Antibody–Drug Conjugates

4. TROP2 Antibody–Drug Conjugates

5. B7-H3 Antibody–Drug Conjugates

6. SEZ6 Antibody–Drug Conjugates

7. Discussion

8. Limitations and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCLC | Small-cell lung cancer |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| LS-SCLC | Limited-stage small-cell lung cancer |

| ES-SCLC | Extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer |

| ADC | Antibody drug conjugate |

| TCE | T-Cell engager |

| ORR | Overall response rate |

| mDOR | Median duration of response |

| mPFS | Median progression-free survival |

| mOS | Medial overall survival |

| SOC | Standard of care |

| DLL3 | Delta-like ligand 3 |

| TROP2 | Trophoblast cell surface antigen-2 |

| SG | Sacituzumab Govitecan |

| I-DXd | Ifinatamab deruxtecan |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| SEZ6 | Seizure-related homolog protein 6 |

References

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, H.S.; Chiang, A.C. Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.; Mansfield, A.S.; Szczęsna, A.; Havel, L.; Krzakowski, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Huemer, F.; Losonczy, G.; Johnson, M.L.; Nishio, M.; et al. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2220–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Dvorkin, M.; Chen, Y.; Reinmuth, N.; Hotta, K.; Trukhin, D.; Statsenko, G.; Hochmair, M.J.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ji, J.H.; et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1929–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazdar, A.F.; Bunn, P.A.; Minna, J.D. Small-cell lung cancer: What we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Mohindroo, C.; Giaccone, G. Advancing therapeutics in small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, C.M.; Stewart, C.A.; Park, E.M.; Diao, L.; Groves, S.M.; Heeke, S.; Nabet, B.Y.; Fujimoto, J.; Solis, L.M.; Lu, W.; et al. Patterns of transcription factor programs and immune pathway activation define four major subtypes of SCLC with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 346–360.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, K.; Yoshida, T.; Motoi, N.; Shinno, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Okuma, Y.; Goto, Y.; Horinouchi, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Watanabe, S.; et al. Schlafen 11 Expression in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer and Its Association With Clinical Outcomes. Thoracic Cancer 2025, 16, e15529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, A.; Mistry, H.; Hatton, M.; Locke, I.; Monnet, I.; Blackhall, F.; Faivre-Finn, C. Association of Chemoradiotherapy With Outcomes Among Patients With Stage I to II vs Stage III Small Cell Lung Cancer: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, e185335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre-Finn, C.; Snee, M.; Ashcroft, L.; Appel, W.; Barlesi, F.; Bhatnagar, A.; Bezjak, A.; Cardenal, F.; Fournel, P.; Harden, S.; et al. Concurrent once-daily versus twice-daily chemoradiotherapy in patients with limited-stage small-cell lung cancer (CONVERT): An open-label, phase 3, randomised, superiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeam, E.; Acuna, S.A.; Leighl, N.B.; Giuliani, M.E.; Finlayson, S.R.G.; Varghese, T.K.; Darling, G.E. Surgery Versus Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy for Early and Locally Advanced Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Propensity-Matched Analysis of Survival. Lung Cancer 2017, 109, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Spigel, D.R.; Cho, B.C.; Laktionov, K.K.; Fang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zenke, Y.; Lee, K.H.; Wang, Q.; Navarro, A.; et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Limited-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1313–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, X.; Bao, W.; Ji, Y.; Sheng, L.; Cheng, L.; Chen, Y.; Du, X.; Qiu, G. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in resected small cell lung cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupérin, A.; Arriagada, R.; Pignon, J.P.; Le Péchoux, C.; Gregor, A.; Stephens, R.J.; Kristjansen, P.E.; Johnson, B.E.; Ueoka, H.; Wagner, H.; et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simone, C.B.; Bogart, J.A.; Cabrera, A.R.; Daly, M.E.; DeNunzio, N.J.; Detterbeck, F.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Gatschet, N.; Gore, E.; Jabbour, S.K.; et al. Radiation Therapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 10, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.L.; Zvirbule, Z.; Laktionov, K.; Helland, A.; Cho, B.C.; Gutierrez, V.; Colinet, B.; Lena, H.; Wolf, M.; Gottfried, M.; et al. Rovalpituzumab Tesirine as a Maintenance Therapy After First-Line Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Patients with Extensive-Stage–SCLC: Results from the Phase 3 MERU Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1570–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owonikoko, T.K.; Park, K.; Govindan, R.; Ready, N.; Reck, M.; Peters, S.; Dakhil, S.R.; Navarro, A.; Rodríguez-Cid, J.; Schenker, M.; et al. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab as Maintenance Therapy in Extensive-Disease Small-Cell Lung Cancer: CheckMate 451. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA Approves Lurbinectedin in Combination with Atezolizumab or Atezolizumab and Hyalu-ronidase-Tqjs for Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-lurbinectedin-combination-atezolizumab-or-atezolizumab-and-hyaluronidase-tqjs-extensive (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Paz-Ares, L.; Borghaei, H.; Liu, S.V.; Peters, S.; Herbst, R.S.; Stencel, K.; Majem, M.; Şendur, M.A.N.; Czyżewicz, G.; Caro, R.B.; et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line maintenance therapy with lurbinectedin plus atezolizumab in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (IMforte): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2025, 405, 2129–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.E.R.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Tsekov, H.; Shparyk, Y.; Čučeviá, B.; Juhasz, G.; Thatcher, N.; Ross, G.A.; Dane, G.C.; Crofts, T. Phase III Trial Comparing Supportive Care Alone with Supportive Care with Oral Topotecan in Patients with Relapsed Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5441–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.; Wu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Lu, Y. Tackling the current dilemma of immunotherapy in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: A promising strategy of combining with radiotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2023, 565, 216239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Schalper, K.A.; Chiang, A. Mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Balli, D.; Lai, W.V.; Richards, A.L.; Nguyen, E.; Egger, J.V.; Choudhury, N.J.; Sen, T.; Chow, A.; Poirier, J.T.; et al. Clinical Benefit from Immunotherapy in Patients with SCLC Is Associated with Tumor Capacity for Antigen Presentation. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterner, R.C.; Sterner, R.M. CAR-T cell therapy: Current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, T.; Xu, D.; Sun, C.; Huang, D.; Liu, X. Targeting DLL3: Innovative Strategies for Tumor Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.G.; Rocha, P.; Freitas Lima, C.; Stewart, A.; Zhang, B.; Diao, L.; Fujimoto, J.; Cardnell, R.J.; Lu, W.; Khan, K.; et al. Delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) landscape in pulmonary and extra-pulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms. npj Precis. Onc. 2024, 8, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yeong, C. Advances in DLL3-targeted therapies for small cell lung cancer: Challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1504139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddio, A.; Pietroluongo, E.; Lamia, M.R.; Luciano, A.; Caltavituro, A.; Buonaiuto, R.; Pecoraro, G.; De Placido, P.; Palmieri, G.; Bianco, R.; et al. DLL3 as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target in neuroendocrine neoplasms: A narrative review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 204, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ren, W.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Chi, K.; Zhuo, M.; Lin, D. Heterogeneity of molecular subtyping and therapy-related marker expression in primary tumors and paired lymph node metastases of small cell lung cancer. Virchows Arch. 2025, 486, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Huang, J.; Jin, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, C.; Lv, M.; Chen, S.; Du, X.; Feng, G. The predictive value of delta-like3 and serum NSE in evaluating chemotherapy response and prognosis in patients with advanced small cell lung carcinoma: An observational study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, M.-X.; Liu, Y.-M.; Kuang, B.-H. The Role of DLLs in Cancer: A Novel Therapeutic Target. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 3881–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cao, D.; Sha, J.; Zhu, X.; Han, S. DLL3 is regulated by LIN28B and miR-518d-5p and regulates cell proliferation, migration and chemotherapy response in advanced small cell lung cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 514, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, L. Knockdown of Delta-like 3 restricts lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation, migration and invasion of A2058 melanoma cells via blocking Twist1-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Life Sci. 2019, 226, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, M.; Kikuchi, H.; Shoji, T.; Takashima, Y.; Kikuchi, E.; Kikuchi, J.; Kinoshita, I.; Dosaka-Akita, H.; Sakakibara-Konishi, J. DLL3 regulates the migration and invasion of small cell lung cancer by modulating Snail. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffin, M.J.; Cooke, K.; Lobenhofer, E.K.; Estrada, J.; Zhan, J.; Deegen, P.; Thomas, M.; Murawsky, C.M.; Werner, J.; Liu, S.; et al. AMG 757, a Half-Life Extended, DLL3-Targeted Bispecific T-Cell Engager, Shows High Potency and Sensitivity in Preclinical Models of Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1526–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Champiat, S.; Lai, W.V.; Izumi, H.; Govindan, R.; Boyer, M.; Hummel, H.-D.; Borghaei, H.; Johnson, M.L.; Steeghs, N.; et al. Tarlatamab, a First-in-Class DLL3-Targeted Bispecific T-Cell Engager, in Recurrent Small-Cell Lung Cancer: An Open-Label, Phase I Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2893–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.-J.; Cho, B.C.; Felip, E.; Korantzis, I.; Ohashi, K.; Majem, M.; Juan-Vidal, O.; Handzhiev, S.; Izumi, H.; Lee, J.-S.; et al. Tarlatamab for Patients with Previously Treated Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2063–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA Grants Accelerated Approval to Tarlatamab-Dlle for Extensive Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-tarlatamab-dlle-extensive-stage-small-cell-lung-cancer?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Paz-Ares, L.G.; Felip, E.; Ahn, M.-J.; Blackhall, F.H.; Borghaei, H.; Cho, B.C.; Johnson, M.L.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Reck, M.; Zhang, A.; et al. Randomized phase 3 study of tarlatamab, a DLL3-targeting bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE), compared to standard of care in patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer (DeLLphi-304). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, TPS8611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA Grants Traditional Approval to Tarlatamab-Dlle for Extensive Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-traditional-approval-tarlatamab-dlle-extensive-stage-small-cell-lung-cancer (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Hummel, H.-D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Blackhall, F.; Chiang, A.C.; Dowlati, A.; Goldman, J.W.; Izumi, H.; Mok, T.S.K.; Sands, J.; Martinez, P.; et al. 214TiP Tarlatamab after chemoradiotherapy in limited-stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC): DeLLphi-306 (NCT06117774). ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perol, M.; Ahn, M.-J.; Cheng, Y.; Clarke, J.; Dingemans, A.-M.; Gay, C.; Navarro, A.; Schuler, M.; Yoshida, T.; Martinez, P.; et al. P1.13A.02 Tarlatamab Plus Durvalumab as First-Line Maintenance in Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer: DeLLphi-305 Phase 3 Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, S206–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, K.G.; Lau, S.C.M.; Ahn, M.-J.; Moskovitz, M.; Pogorzelski, M.; Häfliger, S.; Parkes, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hamidi, A.; Thompson, C.G.; et al. Safety and activity of tarlatamab in combination with a PD-L1 inhibitor as first-line maintenance therapy after chemo-immunotherapy in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (DeLLphi-303): A multicentre, non-randomised, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wermke, M.; Gambardella, V.; Kuboki, Y.; Felip, E.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Alese, O.B.; Sayehli, C.M.; Arriola, E.; Wolf, J.; Villaruz, L.C.; et al. Phase I Dose-Escalation Results for the Delta-Like Ligand 3/CD3 IgG-Like T-Cell Engager Obrixtamig (BI 764532) in Patients with Delta-Like Ligand 3+ Small Cell Lung Cancer or Neuroendocrine Carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 3021–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shi, J.; Chai, X.; Zheng, L.; Wu, L.; Mou, H.; Lin, R.; Qu, X.; Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; et al. A phase 1 dose escalation and expansion study of ZG006, a trispecific T cell engager targeting CD3/DLL3/DLL3, as monotherapy in patients with refractory small cell lung cancer or neuroendocrine carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Pietanza, M.C.; Bauer, T.M.; Ready, N.; Morgensztern, D.; Glisson, B.S.; Byers, L.A.; Johnson, M.L.; Burris, H.A.; Robert, F.; et al. Rovalpituzumab tesirine, a DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: A first-in-human, first-in-class, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgensztern, D.; Besse, B.; Greillier, L.; Santana-Davila, R.; Ready, N.; Hann, C.L.; Glisson, B.S.; Farago, A.F.; Dowlati, A.; Rudin, C.M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Rovalpituzumab Tesirine in Third-Line and Beyond Patients with DLL3-Expressing, Relapsed/Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results From the Phase II TRINITY Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6958–6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackhall, F.; Jao, K.; Greillier, L.; Cho, B.C.; Penkov, K.; Reguart, N.; Majem, M.; Nackaerts, K.; Syrigos, K.; Hansen, K.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Rovalpituzumab Tesirine Compared with Topotecan as Second-Line Therapy in DLL3-High SCLC: Results from the Phase 3 TAHOE Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.R.; Wu, Y.-L.L.C.; Wang, Z.; Rocha, P.; Wang, Q.; Du, Y.; Dy, G.K.; Dowlati, A.; Spira, A.; Dong, X.; et al. ZL-1310, a DLL3 ADC, in patients with extensive stage small cell lung cancer: Ph1 trial update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Big Moves by MNCs: Landmark Licensing Deal for SCLC-ADC!|ACROBiosystems. Available online: https://www.acrobiosystems.com/insights/2692?srsltid=AfmBOorFICgZcWMo_GR4X5HGRrmc8rtoobF8LgiB7IMG5GdDqvWuALxs (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Guo, Q.; Gao, B.; Song, R.; Li, W.; Zhu, S.; Xie, Q.; Lou, S.; Wang, L.; Shen, J.; Zhao, T.; et al. FZ-AD005, a Novel DLL3-Targeted Antibody–Drug Conjugate with Topoisomerase I Inhibitor, Shows Potent Antitumor Activity in Preclinical Models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, Q.; Fang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Song, Z.; Liu, B.; et al. OA06.01 A First-In-Human Phase 1 Study of SHR-4849 (IDE849), a DLL3-Directed Antibody-Drug Conjugate, in Relapsed SCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025, 20, S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvartsur, A.; Bonavida, B. Trop2 and its overexpression in cancers: Regulation and clinical/therapeutic implications. Genes. Cancer 2015, 6, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamura, K.; Yokouchi, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Ninomiya, H.; Sakakibara, R.; Subat, S.; Nagano, H.; Nomura, K.; Okumura, S.; Shibutani, T.; et al. Association of tumor TROP2 expression with prognosis varies among lung cancer subtypes. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28725–28735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trerotola, M.; Cantanelli, P.; Guerra, E.; Tripaldi, R.; Aloisi, A.L.; Bonasera, V.; Lattanzio, R.; Lange, R.D.; Weidle, U.H.; Piantelli, M.; et al. Upregulation of Trop-2 quantitatively stimulates human cancer growth. Oncogene 2013, 32, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA Grants Regular Approval to Sacituzumab Govitecan for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-regular-approval-sacituzumab-govitecan-triple-negative-breast-cancer (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA Approves Sacituzumab Govitecan-Hziy for HR-Positive Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-sacituzumab-govitecan-hziy-hr-positive-breast-cancer (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA Grants Accelerated Approval to Sacituzumab Govitecan for Advanced Urothelial Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-sacituzumab-govitecan-advanced-urothelial-cancer (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Zhang, B.; Gay, C.M. Sacituzumab govitecan: Another emerging treatment option for patients with relapsed small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2025, 14, 4165–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Johnson, M.L.; Paz-Ares, L.; Nishio, M.; Hann, C.L.; Girard, N.; Rocha, P.; Hayashi, H.; Sakai, T.; Kim, Y.J.; et al. Ifinatamab Deruxtecan in Patients with Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer: Primary Analysis of the Phase II IDeate-Lung01 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, JCO2502142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, R.M.; McBride, W.J.; Cardillo, T.M.; Govindan, S.V.; Wang, Y.; Rossi, E.A.; Chang, C.-H.; Goldenberg, D.M. Enhanced Delivery of SN-38 to Human Tumor Xenografts with an Anti-Trop-2-SN-38 Antibody Conjugate (Sacituzumab Govitecan). Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5131–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.H.; Jones, V.C.; Yu, W.; Bosserman, L.D.; Lavasani, S.M.; Patel, N.; Sedrak, M.S.; Stewart, D.B.; Waisman, J.R.; Yuan, Y.; et al. UGT1A1*28 polymorphism and the risk of toxicity and disease progression in patients with breast cancer receiving sacituzumab govitecan. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, F.P.; Muscarella, L.A.; Rossi, A. B7-H3/CD276 and small-cell lung cancer: What’s new? Transl. Oncol. 2024, 39, 101801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.H.; Ju, E.J.; Park, J.; Ko, E.J.; Kwon, M.R.; Lee, H.W.; Son, G.W.; Park, Y.-Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Song, S.Y.; et al. ITC-6102RO, a novel B7-H3 antibody-drug conjugate, exhibits potent therapeutic effects against B7-H3 expressing solid tumors. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, C.M.; Owonikoko, T.K.; Byers, L.A.; Choudhury, N.J.; Ahmed, S.; Cain, Z.; Qian, X.; Brentnall, M.; Heeke, S.; Poi, M.; et al. Multidimensional Analysis of B7 Homolog 3 RNA Expression in Small Cell Lung Cancer Molecular Subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 3476–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fang, W.; Xue, J.; Meng, X.; Fan, Y.; Fu, S.; Wu, L.; Zheng, Y.; et al. A B7H3-targeting antibody-drug conjugate in advanced solid tumors: A phase 1/1b trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1949–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckardt, J.R.; von Pawel, J.; Pujol, J.-L.; Papai, Z.; Quoix, E.; Ardizzoni, A.; Poulin, R.; Preston, A.J.; Dane, G.; Ross, G. Phase III study of oral compared with intravenous topotecan as second-line therapy in small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2086–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, J.; Subbiah, V.; Besse, B.; Moreno, V.; López, R.; Sala, M.A.; Peters, S.; Ponce, S.; Fernández, C.; Alfaro, V.; et al. Lurbinectedin as second-line treatment for patients with small-cell lung cancer: A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif, W. A Phase 1 Dose Escalation/Expansion Study of GSK5764227 (GSK’227), a B7-Homolog 3 (B7-H3) Protein Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC), in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors, Including Gastrointestinal (GI) Cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, TPS847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Drug Administration. GSK Receives US FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation for its B7-H3-Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugate in Relapsed or Refractory Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/gsk-receives-us-fda-breakthrough-therapy-designation/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Zhang, K. Bispecific Antibody Drug Conjugates (bsADCs) Targeting DLL3 and B7-H3 Demonstrated Potent Anti-Tumor Activity in Preclinical Models of Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC). Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/cancerres/article/85/8_Supplement_1/6081/758667/Abstract-6081-Bispecific-antibody-drug-conjugates (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Herbst, R.; Nicklin, M.J. SEZ-6: Promoter selectivity, genomic structure and localized expression in the brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1997, 44, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezelius, E.; Rekhtman, N.; Baine, M.K.; Rudin, C.M.; Drilon, A.; Cooper, A.J. Seizure-Related Homolog Protein 6 (SEZ6): Biology and Therapeutic Target in Neuroendocrine Carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 4419–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemeyer, W.R.; Gavrilyuk, J.; Schammel, A.; Zhao, X.; Sarvaiya, H.; Pysz, M.; Gu, C.; You, M.; Isse, K.; Sullivan, T.; et al. ABBV-011, A Novel, Calicheamicin-Based Antibody-Drug Conjugate, Targets SEZ6 to Eradicate Small Cell Lung Cancer Tumors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgensztern, D.; Ready, N.; Johnson, M.L.; Dowlati, A.; Choudhury, N.; Carbone, D.P.; Schaefer, E.; Arnold, S.M.; Puri, S.; Piotrowska, Z.; et al. A Phase I First-in-Human Study of ABBV-011, a Seizure-Related Homolog Protein 6-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate, in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 5042–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. Safety and Efficacy of ABBV-706, a Seizure-Related Homolog Protein 6 (SEZ6)–Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate, in High-Grade Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Y.; Liu, G.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.; E, M.; Wu, L.; Li, Y.; Rong, G.; Li, Y.; Wei, H.; et al. PTK7-Targeting CAR T-Cells for the Treatment of Lung Cancer and Other Malignancies. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 665970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W. Targeting CDH17 with Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Redirected T Cells in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Lung 2023, 201, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reppel, L.; Tsahouridis, O.; Akulian, J.; Davis, I.J.; Lee, H.; Fucà, G.; Weiss, J.; Dotti, G.; Pecot, C.V.; Savoldo, B. Targeting disialoganglioside GD2 with chimeric antigen receptor-redirected T cells in lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, J.; Chiappori, A.; Creelan, B.C.; Schwarzenberger, P.O.; Koneru, M.; Vahora, S.; Davis, C.; Xu, D.; Wang, C.; Munker, R.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy results of a phase 1 study of LB2102, a dnTGFβRII armored DLL3-targeted autologous CAR-T cell therapy, in patients with relapsed or refractory small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Poirier, J.T.; Byers, L.A.; Dive, C.; Dowlati, A.; George, J.; Heymach, J.V.; Johnson, J.E.; Lehman, J.M.; MacPherson, D.; et al. Molecular subtypes of small cell lung cancer: A synthesis of human and mouse model data. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baine, M.K.; Hsieh, M.-S.; Lai, W.V.; Egger, J.V.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Daneshbod, Y.; Beras, A.; Spencer, R.; Lopardo, J.; Bodd, F.; et al. SCLC Subtypes Defined by ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3, and YAP1: A Comprehensive Immunohistochemical and Histopathologic Characterization. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, A.S.; Micinski, A.M.; Kastner, D.W.; Guo, B.; Wait, S.J.; Spainhower, K.B.; Conley, C.C.; Chen, O.S.; Guthrie, M.R.; Soltero, D.; et al. MYC Drives Temporal Evolution of Small Cell Lung Cancer Subtypes by Reprogramming Neuroendocrine Fate. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 60–78.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Lim, J.S.; Jang, S.J.; Cun, Y.; Ozretić, L.; Kong, G.; Leenders, F.; Lu, X.; Fernández-Cuesta, L.; Bosco, G.; et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature 2015, 524, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target | Drug | Trial (Number, Phase) | Target Population | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLL3 | Tarlatamab (AMG 757) | DeLLphi-300 (NCT03319940, I) | Relapsed SCLC; dose exploration (n = 73) and expansion (100 mg, n = 34) | ORR 23.4% mDOR 12.3 mo mPFS 3.7 mo mOS 13.2 mo |

| DeLLphi-303 (NCT05361395, I) | Tarlatamab and atezolizumab (n = 48) vs. tarlatamab and durvalamab (n = 40) as first-line maintenance in ES-SCLC | mPFS 5.6 mo DCR 62.5% | ||

| NCT04885998, Ib | Tarlatamab + AMG 404 (n = 14) | ORR 20.0–66.7% | ||

| DeLLphi-301 (NCT05060016, II) | SCLC with median 2 previous lines of therapy (n = 110 on 10 mg, n = 110 on 100 mg) | 10 mg vs. 100 mg: ORR 55% vs. 57% mPFS 4.9 vs. 3.9 mo | ||

| DeLLphi-304 (NCT05740566, III) | Tarlatamab (n = 254) vs. SOC (n = 255) in progressed/relapsed SCLC | ORR 35% vs. 20% mOS 13.6 mo vs. 8.3 mo mPFS 4.2 mo vs. 3.7 mo | ||

| DeLLphi-305 (NCT06211036, III) | Tarlatamab and durvalamab vs. durvalumab as maintenance after 1 L in ES-SCLC (n = 563) | Not reported | ||

| DeLLphi-306 (NCT06117774, III) | Tarlatamab vs. placebo in LS-SCLC following chemoradiation (n = 400) | Not reported | ||

| DeLLphi-312 (NCT07005128, III) | Tarlatamab + SOC vs. SOC (durvalumab, carboplatin, etoposide) in untreated ES-SCLC (n = 330) | Not reported | ||

| Obrixtamig (BI764532) | NCT04429087, I | DLL3 positive ES-SCLC and neuroendocrine carcinoma (n = 300) | SCLC (n = 24): ORR 33% | |

| DAREON-7 (NCT06132113, I) | DLL3 positive neuroendocrine cancer (n = 55) | Not reported | ||

| DAREON-8 (NCT06077500, I) | BI 764532 + SOC in ES-SCLC (n = 46) | Not reported | ||

| DAREON-9 (NCT05990738, Ib) | BI 764532 + topotecan in relapsed ES-SCLC (n = 25) | Unconfirmed ORR 70% DCR 87% | ||

| NCT05879978, I | BI 764532 + ezabenlimab in DLL3-positive progressive ES-SCLC (n = 45) | Not reported | ||

| QLS31904 | NCT05461287, I | QLS31904 in advanced solid tumors (n = 290, SCLC-specific unknown) | Not reported | |

| MK-6070 (HPN 328, gocatamig) | NCT04471727, I/II | MK-6070 monotherapy, MK-6070 + atezolizumab, MK-6070 + I-DXd in DLL3-positive advanced cancers (n = 232, SCLC-specific unknown) | Not reported | |

| NCT06780137, I/II | Gocatamig monotherapy, gocatamig + I-DXd, gocatamig + durvalumab in unresponsive SCLC (n = 242) | Not reported | ||

| RO7616789 | NCT05619744, I | Relapsed ES-SCLC and Advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma (n = 41) | Not reported | |

| ZG006 | NCT05978284, I/II | Unresponsive ES-SCLC and Advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma (n = 54) | ES-SCLC (n = 23): ORR 60.9% DCR 78.3% | |

| Rova-T | NCT01901653, I | Previously treated ES-SCLC and neuroendocrine tumor (n = 82) | ORR 18% (High DLL3: 38%) | |

| TRINITY (NCT02674568, II) | Rova-T as third-line and beyond for ES-SCLC | ORR 12.4% mOS 5.6 mo | ||

| TAHOE (NCT03061812, III) | Rova-T (n = 296) vs. topotecan (n = 148) as second-line for DLL3-high ES-SCLC | mOS 6.3 vs. 8.6 mo | ||

| ZL-1310 | NCT06179069, I | ZL-1310 monotherapy, ZL-1310 + atezolizumab +/− carboplatin (n = 112) in progressed ES-SCLC | ZL-1310 (n = 28): ORR 68% | |

| IBI3009 | NCT06613009, I | Unresectable, Metastatic, or ES-SCLC | Not reported | |

| SHR-4849 | NCT06443489, I | Advanced solid tumor | Not reported | |

| FZ-AD005 | NCT06424665, I | Advanced solid tumor | Not reported | |

| TROP2 | Sacituzumab Govitecan (SG) | TROPiCS-03 (NCT03964727, II) | ES-SCLC with 1 previous line of platinum-based therapy and PD-L1 therapy (10 mg/kg, n = 43) | ORR 41.9% mDOR 4.73 mo mPFS 4.40 mo mOS 13.6 mo |

| Ifinatamab deruxtecan (I-DXd) | IDeate-Lung01 (NCT05280470, II) | ES-SCLC with 1 previous line of platinum-based therapy and ≤3 previous lines of systemic therapy (12 mg/kg, n = 137) | ORR 48.2% mDOR 5.3 mo mPFS 4.9 mo 9-mo OS rate 59.1% | |

| B7-H3 | YL201 | NCT05434234, I NCT06057922, I | ES-SCLC with median 1 previous line of therapy; dose-escalation and expansion (n = 72) | ORR 63.9% mPFS = 6.3 mo mDOR 5.7 mo |

| SEZ6 | ABBV-011 | NCT03639194, I | SCLC with ≤3 lines of prior therapy, including ≥1 prior platinum-containing chemotherapy (n = 99) | ORR 19% mDOR 4.2 mo mPFS 3.5 mo |

| ABBV-706 | NCT05599984, I | SCLC with ≥1 prior platinum-containing chemotherapy (n = 22) | ORR 73% (confirmed and unconfirmed) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, K.; Taing, K.; Hsu, R. Updates on Antibody Drug Conjugates and Bispecific T-Cell Engagers in SCLC. Antibodies 2026, 15, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib15010004

Wang K, Taing K, Hsu R. Updates on Antibody Drug Conjugates and Bispecific T-Cell Engagers in SCLC. Antibodies. 2026; 15(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib15010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Kinsley, Kyle Taing, and Robert Hsu. 2026. "Updates on Antibody Drug Conjugates and Bispecific T-Cell Engagers in SCLC" Antibodies 15, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib15010004

APA StyleWang, K., Taing, K., & Hsu, R. (2026). Updates on Antibody Drug Conjugates and Bispecific T-Cell Engagers in SCLC. Antibodies, 15(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/antib15010004