1. Introduction

With accelerating urbanization and rapid population aging, psychological well-being (PW) issues among older adults (such as depression and anxiety) are becoming increasingly prominent worldwide [

1]. Urban Green Space (UGS), which integrates natural contact, emotional restoration, and opportunities for social interaction, is widely regarded as a vital natural resource for enhancing public well-being and alleviating PW problems [

2]. Various international initiatives (e.g., the World Health Organization’s “Healthy Cities” campaign) and national strategies (e.g., China’s “Age-Friendly Cities” policy) emphasize the importance of high-quality UGS development to promote emotional restoration and social connection, thereby enhancing older adults’ subjective well-being and PW, and improving urban livability and inclusiveness [

3].

How UGS influences PW has become a focal point in healthy city research. In previous studies, UGS exposure was often quantified by objective physical indicators such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which measured the amount of greenness within a spatial area [

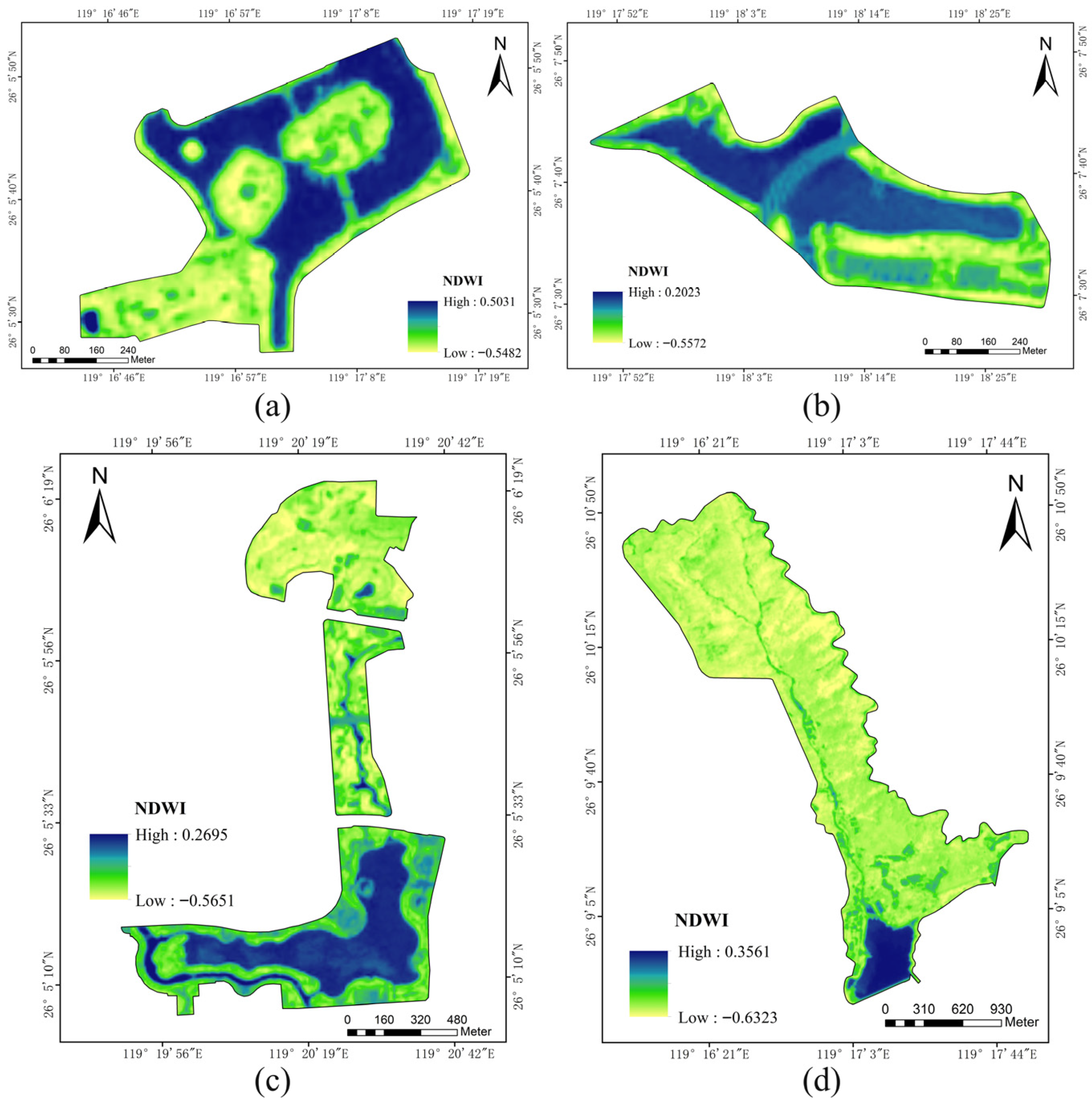

4]. The exposure of blue spaces (BS) is commonly measured using the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), which serves as a key indicator for quantifying the characteristics and information of water bodies [

5]. However, an increasing number of studies emphasize that “green space exposure” encompasses not only the physical presence of greenery but also individuals’ subjective experiences of contact and perception with the green environment [

6]. Due to limitations in physical condition and mobility, older adults tend to rely more on their psychological perception of nearby accessible green spaces than on spatial indicators alone [

7]. Relying solely on objective measures may lead to underestimation or overestimation of the effects of UGS on their PW [

8]. Integrating objective indicators with subjective perceptions has become a crucial means of examining the relationship between UGS exposure and PW in older adults. Scholars have pointed out that subjective perception is a psychological process in which individuals, through their sensory systems, receive external stimuli and actively integrate their personal experiences, such as prior memories, emotional tendencies, and cognitive preferences, to process and interpret these signals, ultimately forming personalized cognition and experiences of objects or environments [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The Perceived Sensory Dimensions (PSD) scale is primarily used to assess people’s subjective perceptions of UGS quality [

12]. It encompasses perceptual dimensions such as facilities, culture, social interaction, biodiversity, safety, and accessibility, which collectively capture older adults’ subjective evaluations of UGS quality.

Current studies have explored the mechanisms through which UGS affects health from two primary directions: one focuses on Perceived Restorativeness (PR). PR refers to an individual’s subjective perception of the psychological and attentional restorative potential of a given environment. It is commonly measured using the Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS), which assesses the restorative characteristics of environments, as explained by Kaplan’s Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and Ulrich’s Stress Reduction Theory (SRT). ART posited that natural environments help restore directed attention that was prone to fatigue, thereby enhancing cognitive functioning [

13]; SRT suggested that individuals’ proximity to green spaces or natural environments induced positive psychophysiological responses, which can rapidly alleviate feelings of tension, anxiety, and anger, promote a sense of calmness and relaxation, and thereby contribute to psychological well-being [

14]. The other emphasizes the positive role of Sense of Place (SOP) in promoting emotional well-being and life satisfaction. SOP primarily referred to the relationship between people and specific locations. The enhancement of SOP (or place attachment) can facilitate psychological restoration and strengthen the capacity for perceived well-being [

15]. Although both mechanisms have received extensive empirical support [

15,

16], studies that integrate the dual mediating roles of SOP and PR in influencing PW remain relatively scarce, and the existing literature predominantly focuses on younger or general populations, with limited attention to the elderly. In addition, issues such as inconsistent green space quality and significant disparities in accessibility for the elderly in second-tier Chinese cities exacerbate the vulnerability of older adults’ PW and reinforce social inequality [

17].

The current studies have several limitations. Firstly, due to age-related declines in physical functioning, sensory perception, and mobility, relying solely on objective exposure indicators fails to accurately capture older adults’ actual environmental experiences. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate subjective perception measures to more comprehensively assess their psychological health outcomes. Secondly, existing studies tended to conceptualize SOP and PR as parallel or independent mediators of UGS effects, without systematically examining their directional relationship or interactive mechanisms, and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) provides an optimal solution and is one of the most commonly used tools for analyzing complex relationships and pathways among multiple variables. These approaches often overlook individuals’ subjective perceptions of the environment and their deep emotional connections with SOP, which may serve as a prerequisite for perceived restoration [

16]. This is particularly true for older adults who have developed a stronger sense of belonging through long-term exposure to UGS. Thirdly, numerous studies have pointed out that Fuzhou City in Fujian Province is characterized by high-density land use and an aging population at greater health risk [

18,

19,

20]. The high-density urban environment further exacerbates the health burdens of vulnerable groups such as older adults, leading to problems such as insufficient physical activity, metabolic risks, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and coronary heart disease [

21,

22]. Researching UGS in Fuzhou can therefore help reduce health disparities, improve public health, and contribute to the development of a resilient and inclusive city, while also filling the existing research gap that focuses on older populations. Therefore, exploring the unique roles of SOP and PR in linking objective and subjective environmental perceptions with older adults’ PW through a multilevel SEM is of critical importance.

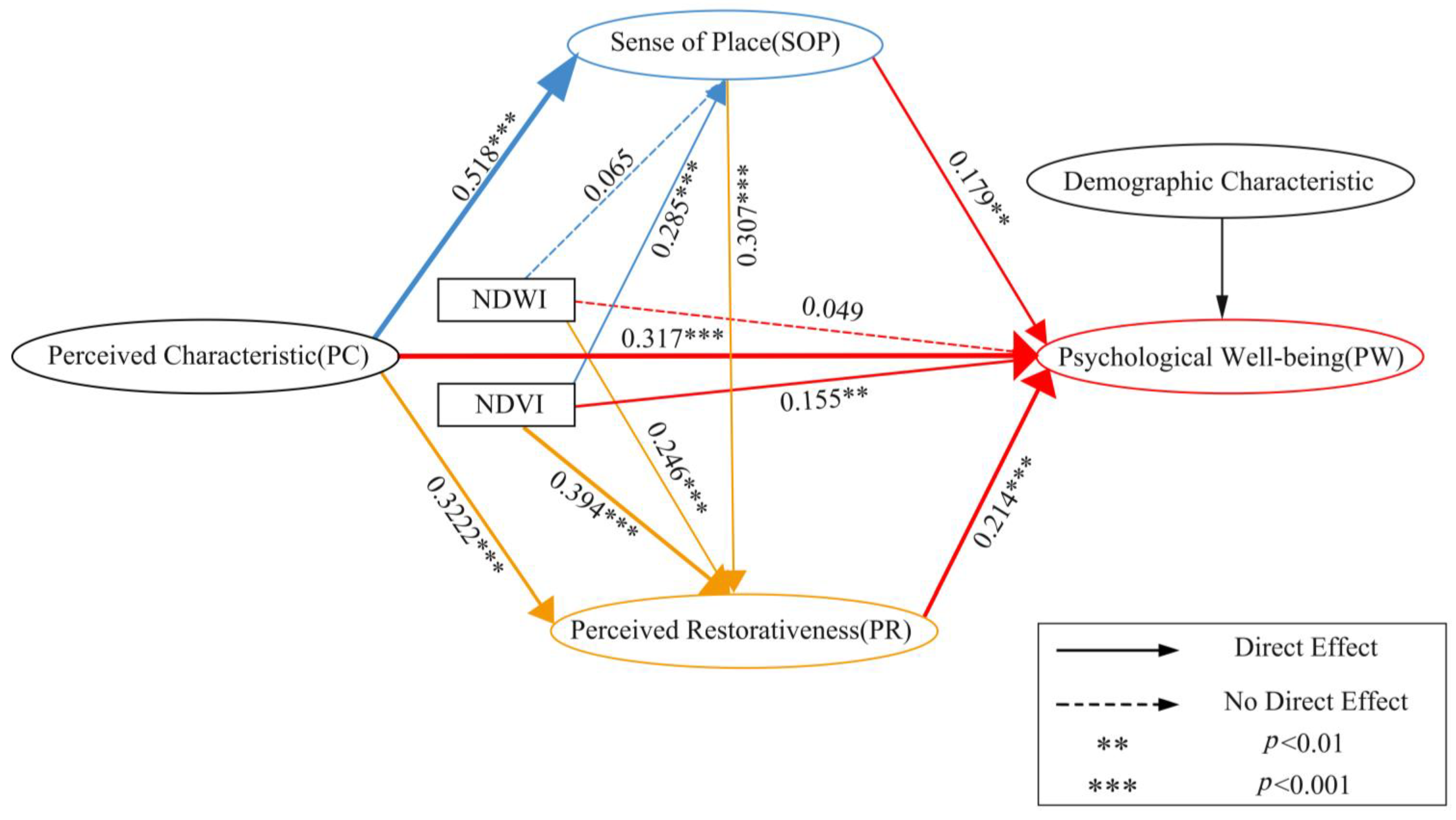

This study conducted a field survey among older adults in four urban parks in Fuzhou City. We established a theoretical framework linking “dependent on or related to UGS exposure characteristics (objective and subjective)—psychological mediators (SOP + PR)—health outcomes,” aiming to investigate the following key questions: (1) Do UGS quantity indicators (NDVI and NDWI) and subjective Perceived Characteristics (PC) exert differential impacts through the distinct mediating pathways of SOP and PR? (2) Is there a chained mediating relationship between SOP and PR? Our study not only expands and refines existing theoretical models but also clarifies how PW can be enhanced in aging and densely populated urban environments.

5. Discussions

This study systematically investigated the complex relationships between objective UGS exposure (NDVI and NDWI), subjective PC, and elderly PW, with a particular focus on the mediating roles of SOP and PR. The findings revealed the associations and path relationships among these variables, highlighting the importance of the proposed theoretical framework “UGS exposure characteristics (objective and subjective)—psychological mediators (SOP + PR)—health effects” in guiding age-friendly UGS development. Furthermore, demographic variables had no significant effect on PW in this study, which may be due to the long-term life experiences that foster stable emotional ties and identity with UGS, thereby reducing the interference of individual background factors.

In response to research question one, our findings reveal that among older adults, objective exposure to UGS (NDVI and NDWI) and subjective PC exert differentiated effects on PW through the mediating pathways of SOP and PR. We found that subjective perceptions were stronger predictors of PW in the older adults than objective exposure. This finding was consistent with the study by [

83], which emphasized that vulnerable groups were more influenced by the quality of GS than by other GS exposures. Across the pathways influencing SOP, PR, and PW, PC emerged as nearly the most explanatory factor. This may be attributed to the fact that environmental perception engages complex multisensory processes and involves cognitive-affective dimensions [

84]. Compared to passive exposure, active perception exerts a more substantial impact on mental well-being, particularly in emotionally resonant and restorative settings [

85]. Second, PC exerted a greater influence on SOP than on PR. While SOP captures long-term emotional ties emerging from sustained human–environment interactions, and is shaped by comprehensive perceived attributes (e.g., facilities, cultural value, sociability, safety, and accessibility), PR emphasizes immediate psychological restoration, relying more on environmental features such as tranquility, openness, and spatial extent, making its scope narrower. Therefore, UGS attributes are more effective in strengthening place attachment and place identity [

74,

86], rather than directly enhancing restorative potential. Lastly, PR exhibited a stronger impact on PW than SOP. Theoretically, PR addresses short-term, rapid attentional recovery in restorative environments, whereas SOP reflects long-term emotional ties, identity, and sense of belonging. Accordingly, PR may exert more direct and immediate effects on emotional and cognitive restoration in older adults. This finding was consistent with the ART [

68].

Interestingly, NDWI did not directly affect SOP or PW but exerted an indirect effect on PW through PR. This suggested that the pathway through which BS influences health tends to follow a “restorative-cognitive mechanism” rather than an “emotional attachment mechanism,” which aligns with the ART [

13]. Visual stimuli undergo a stimulus-organism-response process, where open water bodies influence environmental perception and psychological restoration. BS with expansive and continuous water features facilitates emotional and attentional recovery more effectively in older adults. However, the mere physical presence of water features is insufficient to foster deep emotional attachment and identity toward a place, as the sense of place is a complex construct developed over the long term. This also reveals the differentiated psychological mechanisms through which natural elements promote health among older adults.

Diverging from prior research, ref. [

48] highlighted fascination as the most powerful dimension of PR. In contrast, our findings indicate that “extent” and “coherence” are the most influential PR dimensions. While extent reflects the spatial expansiveness of the environment, coherence pertains to the organizational clarity and logical structure of environmental settings. Open environments provide visual comfort that strengthens orientation, promotes perceived safety, and facilitates psychological restoration [

12,

87]. Spaces that are well-organized, serene, and secure reduce environmental distractions and cognitive burden, offering opportunities for rest and contemplation, which in turn help to alleviate psychological stress [

12,

66,

68]. Accumulated evidence from landscape ecology similarly suggested that UGS with higher connectivity and continuity were more likely to enhance visual perception and facilitate restorative outcomes [

88]. Consistent with [

89], our results highlight that readability, coherence, and accessibility should be prioritized in the design and management of UGS.

For research question two, our study demonstrated that both subjective and objective features of UGS exposure influence older adults’ PW via a sequential mediation pathway involving SOP and PR, indicating a chained mediation mechanism. Several studies lend indirect support to our findings. Van Dinter et al. [

16] revealed that SOP mediates the association between park features and individuals’ subjective well-being, with park attributes directly linked to SOP and SOP exerting a positive and significant effect on subjective well-being. Parks are among the most preferred places for older adults to visit and relax. Familiar environmental cues in the local context can elicit place attachment, strengthen the continuity of SOP and place identity [

59], and contribute to enhanced restorative experiences [

90]. Even exposure to virtual representations of parks can foster place attachment and promote feelings of relaxation [

89]. Previous studies showed that place attachment positively contributed to individuals’ psychological restoration [

15,

90,

91]. When people stay in places with positive emotional attachment, those places have restorative potential [

74]. The addition of distinctive landscape features can enrich perceptual engagement and more effectively foster place attachment and restorative experiences [

15]. The integration of high-quality UGS characteristics with locally distinctive landscape features can maximize individuals’ restorative outcomes [

4,

15,

91]. Compared to other demographic groups, older adults are more readily evoked into positive emotional states through UGS exposure, which in turn fosters emotional bonding and environmental interaction, leading to increased restorative potential. Consistent with previous research, our results demonstrated that vegetation coverage, well-maintained facilities, and accessibility were among the most critical environmental characteristics in age-friendly parks.

In response to the final research question, this study provides three empirically grounded recommendations for the planning and design of age-friendly UG (

Table 6). First, we advocate for urban planning decisions that enhance the SOP by prioritizing design urban parameters [

92], distinctive urban landmarks, urban features [

93,

94], and city branding strategies [

95]. And actively shaping place-based qualities, spatial forms, landscape elements, and diversity [

15,

57]. Second, although our findings suggest that SOP contributes to older adults’ PW by fostering emotional bonds and identity, UGS environments with restorative attributes tend to deliver superior health benefits compared to SOP alone. This underscores the need to prioritize the inclusion of restorative green environments when constructing or retrofitting age-friendly urban areas, especially the green space with extent and coherence. Finally, to improve older adults’ PW and overall well-being, greater emphasis should be placed on perceptible green space qualities (e.g., good facilities, nearby accessibility) than on the amount of exposure. We recommend implementing these three strategies and formulating interventions that are informed by the empirical findings of this research.

While the contributions of this study are substantial, several limitations should be acknowledged, alongside directions for future research: First, the study was conducted only in Fuzhou, a subtropical coastal second-tier city in Fujian Province. Future research should include comparative studies across cities with differing geographic, climatic, and socio-economic contexts to test the generalizability of the proposed theoretical framework. Second, the present study did not differentiate elderly subgroups with chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory illnesses, or cognitive impairments. Given that these populations often exhibit distinct attitudes toward and needs for UGS [

96], their PC, SOP, and PR may vary accordingly. Future research should adopt a stratified approach to examine how diverse health profiles affect the applicability of this framework. Finally, as this study primarily relied on self-reported measures to assess SOP, PR, and PW, future research should consider incorporating wearable physiological sensing technologies, such as electroencephalography, heart rate variability, and skin conductance to more objectively and accurately capture the mental health benefits of green space exposure [

97].