Abstract

This article presents an analysis of the complexities implied by the implementation of the Colombian land restitution policy, as an example of the way in which the state works in its day-to-day practice. The document highlights the role played by the bureaucracy of “land” in the management of the so-called post-conflict setting. It is constructive in showing the multiscale nature of the state, whose operation cannot be understood outside the various levels and scales that compose it. This conception is very well exemplified by the typology of the bureaucracies to which it resorts in order to explain the different meanings of notions, such as “conflict,” “land” or “victim,” for the public officials according to the position they fill in the institutional architecture of restitution. By analyzing the research findings, the author reveals that it is emotional, rather than material, benefits that condense the state’s role in the Colombian post-conflict period.

1. Introduction

A year after the signing of the Havana agreements, in a public interview at Harvard Kennedy School, Juan Manuel Santos told the audience about his primary motivation behind peacebuilding. The anecdote took shape in New York, 18 years earlier, when Santos was the Minister of Foreign Trade in the government of Cesar Gaviria. An international businessman, paradoxically, sentenced his future, along with that of the entire country: “Other countries will invest in Colombia only when it attains peace.” And Santos did bring peace to Colombia. He did so despite being considered a traitor to his party, to his political sector (Uribismo) and to its doctrines. To be considered a traitor, Santos must have broken several implicit agreements on the nation’s governance. These would have been, first and foremost, that Colombia only had one enemy and that that enemy was called Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia- FARC; that the only way to defeat this enemy was through military victory; and that it was not true that there were basic redistributive problems that led to the conflict. However, there is another side to this story that is the exact opposite of the ideas put forth by Uribismo. This other version insists that “The basic problem in Colombia is land; its concentration.” This reading was shared by Iván Márquez, leader of the FARC (and one of its current dissidents, after abandoning political life following the founding of the recent party) and Gonzalo Sánchez, founder of the National Center of Historical Memory. Among these other sections, there is a long list of Colombian intellectuals and politicians who subscribe to this idea: “Colombia’s problem is land.”

As part of what was considered to be his disloyalty, Santos went from claiming that there was no such thing as an internal armed conflict in Colombia, to processing the law on victims and land restitution under his administration. He built the long-awaited first restitution bureaucracy (the Land Restitution Unit), and put the land issue at the top of the agenda of the Havana peace agreement.

By the time of Santos’ supposed betrayal, Colombia was caught up in another decades-long cycle of insurgent and counter-insurgent violence that had dissolved and restructured rural communities and entire rural landscapes across the country. This recent past had been immersed in extremely violent political armed conflict, which caused several hundred thousand deaths, the forced displacement—mostly rural–urban—of at least five million people according to the most conservative estimates (i.e., about 12% of the population), and the consequential generation of more inequality in both the countryside and the city.

At the time, estimates of the number of hectares of dispossessed land varied widely, from 1.2 million to 10 million depending on the source of the information. They were even reported as zero, if that source was an advisor to the Uribe government, with its insistence that such displacement was nothing more than the classic rural–urban migration of the 1970s. In any case, studies on the subject coincided in that the recent war had led to an accelerated increase in the already shameful rates of Colombia’s land concentration [1]. Several studies on the subject have shown that armed groups—paramilitaries in particular—combined raw violence with strategic use of private and agrarian law, especially in relation to the production of property titles through judicial and administrative channels [2]. They did so to destroy factual rights and tenure situations and constitute new ones on behalf of their combatants and allies. The war in Colombia used the law to its advantage in many ways.

For some experts on the armed conflict, failed agrarian reform was the structural cause of the conflict and the reason behind guerrilla mobilization, which involved mainly campesinos. Colombia’s unequal agrarian landscape had begun in the formation of the Republic and persisted through the 1980s. The reason for this was the ruling classes’ refusal to adequately resolve the agrarian question and implement a structural reform that would give the historically or circumstantially landless campesinos a plot of land on which to settle and create the much sought-after rural middle class. Instead, these same campesinos had become the labor force, the peons (bonded labor), of the armed classes—right-wing or left—of the following decades. Their descendants, under the same logic, are also labor force. Land concentration was thus considered not only to be one of the major consequences of the recent armed conflict but also one of its main causes.

The Uribe government had strongly rejected this version of the past, considering it erroneous and even going so far as to suggest that it was an invention of the insurgency in order to gain political ground. It maintained that whatever was happening in rural Colombia was not a political conflict. It was not based on the poor distribution of wealth or the excessive concentration of land and the exploitative relations that result from this. Rather, following the new global security paradigm that emerged after September 11, 2011, the government’s position was to maintain that the public disorder was caused by a collection of narco-terrorist organizations dedicated to pursuing dividends. Uribismo also denied forced displacement and countered that the security measures being deployed were sufficient to contain and reduce it (instead of provoking it, as claimed by the opponents of such claims).

Despite reaching presidency as an Uribista, once he had won the elections, Santos unexpectedly declared that one of the first points on his government agenda would be to give back to the campesinos the lands they had lost in the recent war. And then, as part of a policy shift that seemed inexplicable to most Colombian citizens, he announced that he was going to revive what in previous years had become known as the Victims Law. Within a few months, almost the same legislative majorities that had rejected the Victims Law in its first version discussed and approved similar legislation that, among other things, gave the dispossessed—a new legal category—the right to “transformative restitution.” However, despite the good momentum, the majorities decided that although land dispossession was a problem of the past, this legislation would only apply to dispossessions and abandonments that occurred after January 1991, aligning the provisions with Colombia’s constitutional change. It was also decided that tenedores or holders—a classic legal category that differs from that of owners, occupiers and possessors—would not be included. However, Santos’ law provided many legal benefits for the dispossessed. For example, Law 1448 mandated the application of an alternative system of evidence. Exceptionally, in the proceedings, the complainant was relieved of the burden of proof (which is unusual, as Colombian lawyers are taught that this is a serious breach of due process). This regime predicated the veracity of the claimants’ stories, giving them prerogative not only to know the truth with respect to the past but also, to some extent, to actively dictate it. This version of the bill was called the Victims and Land Restitution Law. Furthermore, a whole new judiciary apparatus and a new governmental agency called the Land Restitution Unit were set up in record time, with the sole purpose of vindicating the rights of the subjects deemed to have been part of the origin of war: the “dispossessed” (los despojados).

This is the story, in brief, that precedes the reflection of this article: the notion that this recent peace in Colombia was implemented to benefit investment, free trade and economic development, despite its content being dedicated to the restitution of land to the campesinos. My paper is devoted to examining some of the contradictions—at least from a personal perspective—of the peace project and its unforeseen bureaucratic construction.

The legal framework that fueled the so-called Colombian “transitional justice” evolved as intricate and contradictory. In this respect, my analysis focuses on the seminal moment of Law 1448 of 2011, as the beginning of the efforts of the Santos government to imagine the conflict and victims’ reparation with the particular design of a bureaucratic structure. Based within political anthropology, my analysis therefore seeks to uncover the twists and turns by which public policies find spaces for opportunity, divulge them, potentiate them, and develop them, with the correlates of such actions for public officials and citizens.

To analyze this moment, I will focus on the management of the land restitution bureaucracy of the conflict, as a rationality that imagines, simplifies, and measures the realities it creates. Law 1448 of 2011 led to the creation of the Registry of Dispossessed and Abandoned Land—a law that also created a follow-up and monitoring system for land restitution and a corresponding series of indicators. This implies that these indicators, together with the censuses, registers and populational surveys, constitute a particular means by which the state relates to subordinates, baptizing them, naming them, constructing their existence. However, it also conceals these techniques and the correct paths that need to be followed in order to finally obtain help, or to make the processes legible [3]. Unlike the specialized literature, this work offers an ethnographic view that speaks to us of the contradictions that are inscribed in the daily reality of land restitution processes and that, ultimately, serve only to generate bureaucratic products or performance factors. It is a story about how the land, as a material good and object of desire (and of dispute in contexts such as Colombia) is bureaucratized to annul its emancipatory, stabilizing and redistributing power.

As far as we know, the guarantee of victims’ rights depends on an intense bureaucratic scheme. Registration papers, recognition processes, the disbursement of aid, all require the remotest layers of public bureaucracies to be put at the service of solving humanitarian matters. The research conducted by Stahn [4], Nalepa [5], Ludi [6], Roll [7], and Slyomovics [8] applies the theses already developed by authors such as Michel Lipsky [9] to the context of armed conflict, in which social policies take on sense, meaning, and scope once they are implemented. In other words, it is the bureaucracies that interact with the victims that ultimately determine the dimension of the public assistance they receive. As such, analyzing such bureaucracies is fundamental to understanding the results of programs, plans, or projects that individual states have devised to deal with post-conflict processes or transitional justice. Both of these ultimately represent bureaucratic agreements that define the content of victims’ rights and guarantees. This paper focuses on the interaction between victims and state bureaucracies at various scales and critically observes them through the ethnographic lens1.

The operations of these administrative units insofar as the conflict, their variations and contingencies are a reflection of this type of domination are the case that I analyze. People, with their different stories, are subjected to burdensome bureaucratic procedures, in order for the competent public official to register their names in the correct database so that they can be identified with the correct label. “Owner,” “dispossessed,” “occupant” and “victim” are some of the identities at play in Law 1448 of 2011. However, this work analyzes how such paths become sinuous and intricate—even for the bureaucracies themselves—in the implementation of a law that sought to optimize the routes already mapped through which to tackle the problem of displacement and to juxtapose bureaucracies of restitution to them. An important finding of this work is that those conflict bureaucracies, even if dedicated to land restitution (with a centrally redistributive content), end up collapsing into human dramas in which they—as with the human bureaucrats—only have to empathize with the victims. Such personal and emotional treatment of claimant victims is ultimately a form of state governance in neoliberal transitional contexts that confronts bureaucracies and victims with the public impossibility of redistribution.

The hypothesis that I want to defend in this work is that, in the Colombian case at least, the bureaucratic existence of “land” as an object of dispute in the conflict and a bureaucratic object of reparation has been used to displace urgent discussions on social policy. Such discussions, although present in the distributive debate that implies the addressing of land tenure, are diluted in the very technicalities of finding, counting, understanding, and delivering “land.” That is, the bureaucracy created over territorial disputes has only served as a convenient mask to conceal larger distributive debates. That mask is, as was heralded by the classics of state anthropology, a bureaucratic interaction. The singularity of these interactions in transitional contexts—which seemed cold, impersonal, and indolent as the ideal types of bureaucracies reported since Weber—is that they are affective bureaucracies. It is the emotional repertoire of bureaucracies, and not the political effort for inclusion, that is making a transition in Colombia.

To support the analysis, I use ethnographic techniques to observe the reception of victims in Santiago de Cali, Valle de Cauca, and in Quibdó-Chocó. I also apply semi-structured interviews with officers that are part of Bogotá’s care and control schemes. The ethnographic work is pertinent when it comes to defending my hypothesis, as it denaturalizes practices that are hidden in the processes of the strangely normalized “peace bureaucracy.” Thus, the ethnography helped me to render alien something as familiar as linking land with the post-conflict, and it is precisely this alienness that encapsulates what this work is intended to reveal.

I mix ethnographic techniques with spatial analytical tools of legal geography, such as scalar analysis, to present the findings. A scalar analysis of legal geography will provide me with useful tools with which to organize the data I collected ethnographically: the logics of space will help me to give meaning and context to the narrative. Thus, the analysis that I hereby develop is made up of three scales and an ethnographic coda. My study of land restitution offices in Cali and Quibdó was based on this analytical angle. As Colombia’s second largest city, Cali is important within the statistical panorama of transitional justice. The city is home to approximately 2.5 million inhabitants and the highest violence index in the country, measured in numbers of homicides per year [10]. Quibdó, on the other hand, is the capital of Colombia’s poorest region, Chocó, which borders the Pacific Coast, and has been, according to reports by the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica- CNMH, one of the hardest-hit by the conflict in terms of victims and damage.

Bearing in mind the above, in the first part of the text, I explain the analytical approaches of legal geography and political anthropology, and how I plan to use them to construct my proposal. In the second, I describe the legal and bureaucratic map that emerged to implement the Victims Law, and which locates the concept of bureaucratic land as a phenomenon that describes the relationships between victims and government officials. In the third, I conduct a scaled and material analysis of three areas of bureaucratic organizations that manage the work of transitional justice. This part is based on the narrative of my experiences in two different places, documented through the use of ethnographic techniques. In the fourth part, I provide a theoretical analysis that explains the workings of the relationships and phenomena arising from ethnographic and geographic observations present in scalar analysis. I finally present my conclusions in the fifth section.

2. Analytical Approaches

2.1. The Ethnographies of the State: The Anthropology of Law

Anthropology underwent major changes at the beginning of the 20th century. After the appearance in 1977 of Phillip Abrams’ famous essay “Notes on the Difficulty of Studying the State,” the discipline lent its ethnographic methods to the analysis of the state as an apparatus: a bureaucracy. In that turn, questions about the state abandoned the ontological nuance and metaphysical framework, in order to document something for which ethnography was useful. The latter included describing processes, experiences, spaces, borders and emotions; recovering the perspectives of the actors; making the unfamiliar familiar and the familiar alien to the ethnographer, and focusing attention on the researcher’s reflectivity (which is their own) [9,10].

That the state is not an entity but an experience or a process—as conceived by contemporary political anthropology—has several implications, all of them related to the Weberian image established by lawyers in the public administration (hierarchical, closed, controlled). From ethnographic perspectives: (1) The state is not timeless. It is anchored in people, in rituals, in forms, and has precise temporalities from which it enters, leaves, remains or disappears, like a spectral existence. (2) The state exists not as a subject/object but as a process, a kind of statehood. It is something that is constructed, that is recognized, that is embedded in unforeseen political objects: the security of public buildings, the long queues for claims, the indolence of the bureaucrats, the tedium for citizens, the sensation of chaos and disorder, the illegibility of official processes and people’s impotence when they are at the counters, the crucifixes on the walls in courts, and the papers crammed into files. (3) Statehood is contingent and the law is only one of the elements that come into play in its complex construction. Contrary to Weber’s declarations, the law cannot predict the action of a bureaucrat, but the bureaucrat creates the law and the ways in which it is applied. Thus, it is possible to summarize the anthropological approach to the state quoting Sharma and Gupta, who suggested that this approach differs from other disciplines by according centrality to the meanings of everyday practices of bureaucracies and their relation to representations of the state [11].

In this particular study, I will use the term legal ethnography to refer to the process of inquiry into the legal field that uses ethnographic techniques of description and observation to account for how the legal constitutes, modifies and alters the scenarios it occupies. Speaking from its endings, from its physical presences, from its materiality, the ethnographic approach will help me to break the abstractions of administrative law to identify its singular meanings, its contradictions and tensions. The analysis of that materiality will then lead me to be especially sensitive about what kind of state exists for the victims, what exchanges they engage in with the law, and how this affects the bureaucrat or technocrat at different scales. Thus, following the caveats regarding multi-situ bureaucratic analyses, I will try to observe statehood as a continuum that begins with the story of a citizen with certain characteristics and connects with officials. These officials, in representation of the state, inscribe multiple subjective manifestations in the decision—a far cry from the “univocity” with which the state is portrayed from traditional approaches [12].

Having said that, to enrich this work with the contributions that can be obtained from legal ethnography, in April 2014, I began my daily visits to centers offering services to victims and the displaced. After five days of observing the operations of the three different offices that are part of the municipal ombudsman’s office, I began a plan of semi-structured interviews to use with people in the victims’ registry offices who wanted to share their stories. I was able to interview 15 victims, seven public officials at the municipal citizen attention offices, and three victims’ organization leaders with whom I occasionally worked on information requests and filing (fundamentally, sending rights of petition to public entities). I held three interviews in Bogotá, with people at the National Comptroller’s Office (CGN), and with the Special Administrative Unit for Land Restitution. Finally, I held one on-line interview, with an expert in Inter- American Court of Human Rights -ICHR. The fieldwork and information gathering culminated in Quibdó, on June 16, 2018.

2.2. Legal Geography: Scales and Space-Time

According to María Victoria Castro, when space is taken into account in legal analyses, it tends to be thought of as the backdrop or container in which legal phenomena occur or cease to occur. In other cases, the question of the spatial effects of law is not considered at all or is considered to be presumed, insignificant or irrelevant [13].

In this context, legal geography invites us to observe the premises or epistemological assumptions with which non-spatial categories operate and, within them, their territorialization strategies. One of its tools that I consider especially powerful for the law is the analysis of scales and space-time2. I will specifically use scalar analysis to account for the construction of the bureaucratic organization of the Victims Law as a complex assembly that is played out on several levels. The scalar analysis draws on the work of Mariana Valverde, especially “Chronotopes of Law: Jurisdiction, Scale and Governance” [14], in which the author focuses on the analysis of specific regulations. Ideas, discourses and rules are inscribed in a certain space-time, while creating their own spatialities and temporalities. The scalar analysis is a way to operate this sensitivity in space (topo and time (chrono)). Reality is constructed on different parallel, juxtaposed, opposite scales, which do not cancel each other out or deny each other, but rather show the complexity of the assemblages that some realities construct. For this case, I will reproduce three scales, which, like photographs, take images of singular experiences of land administration in Colombia.

I use legal geography and political anthropology to interpret the realities brought about by post-conflict norms at different scales. I propose a parallel interpretation of the spatial games involving the metaphors of measurement and reporting, within the state’s panorama of peace. The latter serves to offer some parallel readings of the issue of materiality in transitional justice. And these use alternative means to observe the articulations between the development model, the design of the social bureaucracy of attention to the victims and the benefits that these entail in our context. In this respect, the scalar analysis will allow me to show how legal geography and its concern for space-time can help us understand the complexities of the bureaucratic existence of the current conflict and how it impacts the land restitution actions that are involved. My analysis of the materialities will also demonstrate that understanding the state as a process—and not as an entity—throws light on the opacities of the current regulations, revealing in the end that it is redistribution (or social debate) that continues to be concealed behind public jargon.

Having said this, I will explain the three scales. The first describes the influence of international actors, such as NGOs, on the construction of the conflict as an expertise that is implemented in legal production, in political discourse, and in the bureaucratic activity surrounding the post-conflict context in Colombia. The second scale is built around a national scenario and on how specific programs and the system of indicators are designed to monitor and show a certain kind of progress in the post-conflict and land restitution processes. Finally, the third scale focuses on a local or municipal context. Here, I want to provide details of the relations that arise from the interaction between citizens and bureaucrats and that take place in and around the offices in charge of the post-conflict and land restitution programs across the country.

To achieve the articulation that I propose, I will first establish the social and institutional context in which the legal production related to peace and the post-conflict setting is developed. This will allow me to construct a map in which to situate the norms used to implement the Victims Law, and to analyze the subjects they regulate (bureaucrats and victims, among others) and the effects they produce on them.

3. The State of Peace

With the enactment of Law 1448, the national government did not create a system of attention to victims from scratch. It appended one to an existing system dealing with attention for the displaced population (Law 387 of 1997), for the victim population (Law 418 of 1997), and the strategy of individual reparation through administrative channels (Decree 1290 of 2008). This, in addition to the judicial channels of a criminal nature, foreseen in Law 975 of 2005, on demobilization and reincorporation and paramilitary groups, became known as the Justice and Peace Law. This was a dense institutional architecture, developed not least because of the intervention of the Constitutional Court in Ruling T-025 of 2004. The ruling declared the institutional state of affairs with regard to displacement and developed the first attempt at inter-institutional work based on rights and differential approaches to assist the vulnerable population [15].

Against this background, Law 1448 used the local and national infrastructure developed in the area of displacement, partially reflected in Law 387 of 1997. Specifically, the system of attention to victims was created based on the attention and orientation units (UAO)—traditionally located in the municipalities—and on the assistance programs for housing and credit lines embodied in Law 418 of 1997. All of this was supported by the broad lines of coverage provided by the Public Prosecutor’s Office through the municipal offices, responsible for providing primary care to the victims and for the collection of the first statements based on acts of victimization [16]. Since the 1991 Constitution, the municipal offices have been consolidated as the entities closest to the citizens in their work of guaranteeing fundamental rights [16].

There then was an institutional transmutation that has been little discussed: the social bureaucracy became the bureaucracy of displacement, and this, in turn, the bureaucracy of peace. This explains, in part, why most of the bureaucratic debates about conflict and transitional justice have used the language of reparation, memory and the guarantee of non-repetition to conceptualize social requirements (material benefits such as education, health, housing and even employment) [17]. This conceptualization—confusing, to say the least—which mixes the social with the transitional, was also criticized as suspicious by theoretical critics of transitional justice. These critics rightly questioned it as being distant from discussions about the material: transition schemes are usually dedicated to strengthening civil and political rights, the rule of law, and accountability mechanisms, but not to discussing structural problems of poverty and inequality [18]. However, exceptionally, compared to the models of transitional justice developed in the rest of the world, in Colombia we adopted an approach to transition with a focus on the victims and an institutional link between the transitional and the social. This is significant, given that since the inauguration of the transitional and post-conflict models of justice, little social policy has been discussed beyond memory, truth, and reparation (as transition mandates). This, in turn, actually has little to do with the redistribution historically seen as required to purge the conflict.

This change occurred, as I mentioned, both at the street level (the frontline bureaucracies such as the UAOs and the public prosecutors’ offices), and at the managerial level. The first management level, the Sistema Nacional de Atención Integral a la Población Desplazada por la Violencia (National System of Comprehensive Care for the Population Displaced by Violence) became the Sistema Nacional de Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas (National System of Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims). The Consejo Nacional de Atención Integral a la Población Desplazada (National Council for Comprehensive Care of the Displaced Population) became the Comité Ejecutivo para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas (Executive Committee for Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims). Another important aspect was the transformation of the registers, censuses and administration technologies that served as repositories for the existence of vulnerable populations: the Single Registry of Victims (RUV) incorporated the former Single Registry of Displaced Population (RUPD) and they are now linked to the same platform. Thus, the care systems for the displaced population migrated quickly in 2012, to attend to a new political subject: the claimant victims of the armed conflict3. This new legal and political status recognized by President Santos’ legislative process represents a truly significant change for people who have been dispossessed of their land. Demanding restitution is not like merely asking for assistance, as it used to be in the previous registers. By mandate of Law 1448 of 2011, the request for restitution is now a right that is created from the very beginning of the process as one’s own, and hence the position of the claimant is different from that of the landless victim.

However, this complex institutional design involved building a sophisticated managerial body. This is how the Special Administrative Unit for Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims (UARIV) was created to deal with the coordination of the approximately forty entities that make up the National System for Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims (SNARIV), responsible for executing and implementing public policy for comprehensive care, assistance and reparation for victims4. The UARIV, better known as the Victims Unit or simply La Unidad (The Unit) has played a leading role in the implementation of public policy on victims in Colombia. Its concerns and work have focused mainly on two areas: territorialization and financing strategies. Both were partly developed in the Conpes Document 3712 of 2011, in charge of elaborating the financial plan for the sustainability of Law 1448 of 2011. The document, along with other subsequent ones, clearly states something that would later be developed in the text of the Havana Accords: peace should be implemented in decentralized schemes, in terms of both management and budget. That was, therefore, the scheme for “territorial peace” [19].

People in the UARIV speak of the obsession with “territorialization” as a concern derived from the need to “have an articulated presence in the territory.” This was something that the UAOs and the municipal authorities were already doing; thus, what was implemented in 2012 was a great plan for the territorialization of services, bound to the land already obtained by these institutions. According to UARIV officials, it was thought that they would not have to do anything to focus attention on the victims because the bureaucratic structures in which they would operate already attracted them using another name: that of displaced persons. For UARIV, it was always clear that displaced persons and claimant victims are one and the same. In the words of one of the interviewees, “it is the displaced persons themselves that are in charge of understanding and presenting themselves as victims, and thus adapting to the new institutionality.”5 This reveals that the emphasis on land restitution was a contingent product of the Santos government’s will to improve (in the words of Tania Li). However, and this too is important, as I will illustrate later, this willingness to improve requires many political alignments to bear fruit—and the story I am telling here is precisely one of bureaucratic misalignment.

The Sub-Directorate of Nation–Territory Coordination was created within the Sub-Directorate General of UARIV, in order to rationalize this center–periphery link. This entity would be in charge of offering technical assistance to apply Law 1448 in the municipalities6 and of specifying the direct presence of the UARIV in several parts of the country, using the principle of the decentralization of functions. In developing this plan, twenty territorial directorates came into operation between 2012 and 2018, mainly located in regional capitals: Central (Bogotá), Magdalena Medio, Caquetá-Huila, Chocó, Magdalena, Putumayo, Atlántico, Bolívar and San Andrés, Valle de Cauca, Sucre, Córdoba, Norte de Santander, Llanos Orientales and Amazonia, Urabá, Cesar and Guajira, Eje Cafetero, Santander, Nariño, Cauca and Antioquia. This represents the country’s geography of peace [20]7.

From that moment on, attention to victims focused on the territorial sphere. The macro document that condenses the nation–territory link is the Territorial Attention Plan (PAT) prepared by each municipality. This should reproduce the ecosystem of institutional attention to victims, its main routes, channels of dissemination and emergency assistance plans, together with complementary measures of attention and integral reparation. These plans must also give an account of the mechanisms for the effective inclusion of victims’ organizations and guarantee that the proposals that arise from these spaces are considered in the Local Committee for Transitional Justice, as the deliberative body at the base of the victims’ processes in the territories. The UARIV evaluates each PAT to decide the level of intervention that each municipality should adopt regarding the implementation of the comprehensive victims policy or the structure of the implementation of plans from the center.

This “decentralized” operation of attention to the victims of the conflict, however, has several structural problems. The first is that, despite the regional focus of the 1991 Constitution, a strategy of budgetary recentralization was derived from Legislative Act No. 1 of 2001 and Law 715 of 2001. This led, in effect, to our not having a country of regions on the national administrative map. On the contrary, there is a clear hierarchy between the center (as manager) and the periphery (as executor) of all programs with development components. The second is that territorial leverage has an excess of vertical accountability that ends up saturating the territorial entities with control and surveillance mechanisms from the center, generating the importance–insignificance relationship referred to in legal geography. In this sense, UARIV creates, reviews and strictly monitors the guarantee of the rights of the victims claiming land, through several mechanisms. However, all of this bureaucracy comes with a high level of tension, and deciphering the system and its twists and turns is almost impossible for anyone. For the purposes of this article, it suffices to say that the relationship between UARIV (Victims’ Unit) and URT (Land Restitution Unit) is vertical. Although the former is the most important unit in the system of comprehensive care for victims under Law 1448, it is not the one that assigns land in the restitution process. The UARIV serves merely as a gateway of sorts, which captures the initial information relating to the individuals intending to access the restitution. However, ultimately, this is a fraught relationship, as the filling out of forms is the first such mechanism the claimants come across in the process that exercises power over their sector of the population. The national government’s latest guide, “Coordinación armónica entre entidades del sector público en materia de restitución de tierras despojadas“ (Harmonious coordination between the public sector entities in the area of the restitution of dispossessed land), shows that these relationships are not evident, even within a regulated state.

The above is without even mentioning the “micro-controls”—in other words, the UARIV’s reviews of the taking of statements from victims in the territory. Thus, the Single Declaration Form (FUD), which all victims must fill in at the UAOs or at the municipal offices, travels without fail to the UARIV’s Sub-directorate of Registration in Bogotá, where each declaration is assessed and a decision is made as to which victims enter the RUV and which do not. Once there, on the ninth floor of the Avianca building in the center of Bogotá, the UARIV issues the registration resolutions, which are sent to the territorial addresses for final notification. Attention to victims is then deployed indirectly from the center, which, in many ways, overshadows the powers and agencies of the regional directorates [21]. Despite this, the latter also resist, negotiate, process, and alter the flow of information and control towards the center, turning the “state of peace” into a confusing crucible for the victims, with more convolution than anyone would expect8.

As we can see, the picture is intricate, opaque, and almost unreadable. It is a perplexing maze, written in the register of traditional law. This map, however, provides several important clues: the attachment of the peace bureaucracy to the social bureaucracy within strategic and global plans to fight extreme poverty, and the center–region tensions in matters of budget or competition. This calls into play classic figures of administrative law, such as deconcentration and decentralization.

Another aspect that this process reveals is that the Unit and the specialized courts are immersed in what Jean and John Comaroff call the judicialization of the past. A judicialized past (even one constructed through an alternative regime of evidence) is constituted of a series of reductions, or simplifications. Indeed, claimants’ stories have to be framed within a series of legal categories that capture some of the narrative elements while excluding others. Thus, in the words of the Comaroffs, the judicialization of the past requires us to reduce complicated histories such as those of colonialism in South Africa—or of land dispossession in Colombia—to a language of rights and duties, damages, victims, and perpetrators. These are bureaucratic concealments that arise in restitution processes, and they arise precisely because they are conducted through law.

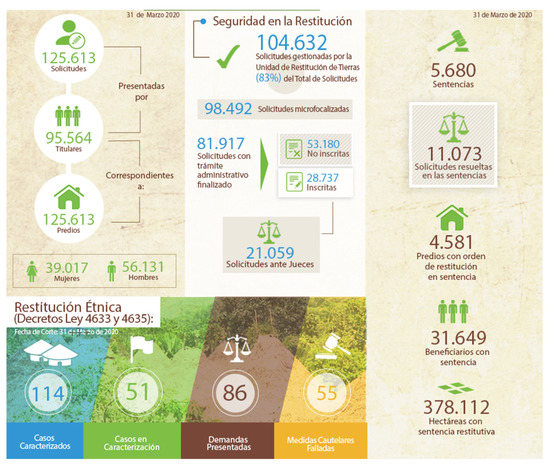

The bureaucracy of restitution makes us believe that restitution will exist, or that we are at least doing something about it. In other words, it operates on a symbolic level: we have the bureaucracy of restitution, not restitution itself. The numbers show this. In 2020, Colombia does not have a confined rural cadastral system. This prevents us from knowing exactly how the national rural landscape is made up and who its main owners are. This is why the bureaucratic process of the Restitution Unit is slower: it has to focus on the disputed properties. According to the Land Restitution Unit, as of March 31, 2020, 125,613 applications had been submitted by victims. However, only 5608 sentences and retitling cases were recorded. By the first major restitution assessment in Colombia, five years after the start of the Land Restitution Unit’s work in 2017, the Unit had received just over 100,000 restitution requests, of which approximately 42,000 had already been resolved (18,000 had been admitted for trial before specialized judges and 24,000 had been rejected). Of those admitted, the judges had ruled on 4800 cases, 98% of which were won by the Unit. This implies a stark truth: in Colombia, the re-constitution process has not generated a redistribution of land, because only 2% of the titles under discussion have changed hands. However, the legal and bureaucratic process has generated great gains as well as symbolic recognition for those who can position themselves as “claimants.”

Land as a benefit is a merely bureaucratic creation, which does not exist beyond the offices and procedures that process it, or the Excel lists that store the names of the applicants. Land then ceases to be a key resource for achieving structural reparation for victims of the conflict and becomes a merely bureaucratic manifestation, configured and measured by indicators. These indicators mask and replace true restitution and give the appearance of effective progress in redressing the problems that are addressed by post-conflict regulations. Bureaucratic land, as I call this phenomenon I have just described, is key to understanding the relationships that are woven between officials representing the government and the victims of the conflict. This is easily recognized in the way the restitution unit accounts for its work to show that it is “doing something.” The information shown in Figure 1 below was taken from the current statistics on land restitution in Colombia.

Figure 1.

The current statistics on land restitution in Colombia. Source: https://www.restituciondetierras.gov.co/estadisticas-de-restitucion-de-tierras. Accessed 3 May 2020.

A story of profound success, some would say. However, if we were to present the numbers differently, emphasizing the time that has passed and the few rulings that have brought about changes in the owners of the disputed land, the picture would be different. Precisely because the perception of the Unit’s initial officials was that dispossession had mainly affected the poorest rural communities, and had contributed to both their impoverishment and the increase in the rate of land concentration. Restitution was seen as a measure of retributive justice but with redistributive effects in the classic sense: restitution would lead to deconcentration of the land. However, another, more subtle and more profound type of redistribution was also at stake. With restitution, the means for the production of administrative and judicial truth were also redistributed. This policy has provided those who speak on behalf of the dispossessed with the power to mobilize the epistemic apparatus of the state, and to generate new official narratives that reorganize the use of symbolic and physical state violence. Here, according to Juana Dávila (2017), it is the officials who were mostly from the human rights community and the group of claimants that come to mind.

The analysis presented in the following sections shows that what I describe as bureaucratic land is what drives these relationships. There is no money, program or structural plan to make up for the unfulfilled promise of land redistribution. Some bureaucrats are concerned about the people; aware, in their own way, of the social conflict. These bureaucrats empathize with the victims and, at various levels, provide love, consideration and comfort. My analysis of the fieldwork thus shows how the state becomes an affective bureaucracy.

As I mentioned above, I devote the next section to integrating the tools of legal anthropology with legal geography so as to analyze the effects of bureaucratic restitution on people’s rights and on land restitution. I do so in order to construct scales of analysis, with live information, that unravel the relationships that arise from the implementation of the Victims Law and that produce effects on the conception of the state, on the identity of the victims, and on the actions of the bureaucrats involved.

4. Scalar Analysis

4.1. Scale I: “The Global Expertise of Transitional Justice”

To reestablish the victims’ equality, bring them to trust the state, and reincorporate their condition as full citizens are some of the fundamental elements of the framework of Colombian transitional justice. The penetration of international channels into the jargon of the model was central to that bureaucratic creation of transitional justice: as soon as the tasks that had to be carried out became a “system,” we would need a “legal framework” to organize the situation and a number of technical bureaucracies to develop it. This activated the creation of the technocracies for peace, the conflict as expertise, and its instruments, language, and tools as apolitical work tools [18]. The framework also provided the field of work with the necessary legitimacy:

The challenge is to turn this into a technique. We don’t need people to think, how does he do it? We don’t want them to think that because we work in transitional justice, we are necessarily philanthropists, gentle benefactors, or left-wing idealists, because all of those sitting here have been labeled many times, not just as left-wing, but as part of the guerrilla. People have to respect this. People have to recognize that this is something complex that they have to know about. So, for example, expertise in comparative politics is fundamental: people begin to respect me when I say that I’m an expert in the inter-American system but even more so when I can tell them the three last transition processes in the world off by heart9.

This is how the emphasis on the fulfillment of international standards triggered the arrival in Colombia of a humanitarian technocracy, which, with its expertise in public international law and compared methodologies, began to build a bureaucratic humanitarianism of sorts within our borders.

In this specialized language, the victims of the crimes committed during the internal armed conflicts have the right to receive appropriate reparation to the damage perceived, and re-establish the state of things to the situation prior to the victimizing act (even if it is meager). Reparation is the way in which the transitional justice model imagines dealing with the problems of economic inequality. The restorative logic in Colombian transitional justice is clear in all ICHR guidelines [22] and fulfills the principle of restitutio in integrum10. The reparation measures must therefore be effective, pertinent, professional, and non-discriminatory. The protectionism of these reparations, all of them “transformative and integral” as stated by the law, were such that they have turned into a new social policy in Colombia. However, coming from the Colombian discussion about land restitution as I have explained above, the transformative and integral reparations turn into a new social policy that, within the scheme, paradoxically do not recognize the problem of inequality as something structural to the conflict, but rather as a contingency, something that happens as an effect of the war and that must be repaired. In the voice of the international officers that I interviewed—all of them related with the Uribista perspective—the Colombian conflict is a problem of terrorism, not one of inequality.

Reparation is at the heart of all of this. And land is at the heart of reparation. It is at the heart, because it creates a re-establishment of the law and justice, with the state as referee, redistributing within the framework of social justice. Those that criticize peace have not understood this. Reparation does not create expensive outlays for the state. The state only referees these operations; it only reintegrates what’s been seized. And this is a great promise of justice for those who have lost everything11.

The expression of this official is thus replicating Uribe’s version of the land problem in Colombia. For example, that there has been displacement has only been an effect of the actions of terrorist groups. However, it was something that happened contiguously and that the state can repair without much effort. Reparation, therefore, brings social justice, despite the fact that the state does not design social benefits to respond to the problem of the conflict and acts as a “mere referee.” Various authors have already pointed out that the policy of reparations substituted the state articulation of social and economic demands using the jargon proper to the conflict, where other types of concepts such as “restitution,” “reparation,” and “guarantees of non-repetition” became the new state framework for social policy [17]. Surprisingly, in this new language, the reparation and guarantees of non-repetition end up being conceptualized as basic social and economic rights, without this being their goal, given that the state understands its intervention there as a mere intermediation that “regresses the effects of the conflict.”12 However, this emphasis on reparation as social justice would also exhaust any efforts to consider the problem of poverty and redistribution in Colombia, making them marginal and supplementary, and narrowing them to mere “reparation.” As such, the government would create work technologies and operational structures that turn social problems into mere accessories [23]. We will see how, while for the victims the care processes represent life alternatives, for the design of the conflict “social benefits” do not exist among its concerns. That is: while for land claimants the problem is that the dispossession plunged them into poverty, the bureaucratic reasoning that deals with these problems only sees it as an effect of the evil acts of the terrorist narco-guerrillas. This is the way in which states in late liberalism conceal neoliberal structures [24], and this, of course, has had much to do with designs offered by transitional justice to “generate development” [18].

However, in the specific case of the Colombian conflict, this transmutation (of the social merged into the transitional) comes about through land. As I mentioned earlier, land appears as an unkept promise. At the same time, the hope for structural change conceals opposing operations: the difficulty of change, the marginalization of debates on redistribution and the continuity of historical problems.

This is paradoxical. One of the peculiarities of the model of Colombian transitional justice is, as well as its focus on victims, its concern for issues of redistribution; in other words, land. This deals with one of the most significant critiques of the traditional transitional justice model; that is, its concentration on political and civil issues that focus transition on institutional strengthening (rule of law, accountability and guarantee of rights) before discussing social problems [25]. Surprisingly, the Colombian conflict deals with the social by redistributing land despite the fact that, as we saw earlier, it acts as a “mere referee.”

This “gain,” for some, comes from the victory of the diagnoses of the social sciences with respect to the domestic conflict. Since the 1990s, Colombian academia has been working on land concentration as one of the biggest fundamental problems in Colombia. This connection between land and structural Colombian problems comes full circle with the involvement of historians and anthropologists as the main researchers of the public agencies in charge of operating restitution, in what we could call academic bureaucracy [20]. This bureaucracy is concerned with historicizing the past and building complex trajectories of dispossession, turning it into the central and biggest problem of the conflict. This is fully described by the platitude Colombia’s problem is land, which I have referred to above.

The engines of the post-conflict setting moved. Land appeared to be mediating this drive for a pacification that seemed revolutionary, despite the fact that the actual effects of restitution as redistribution are marginal. The next section deals with the tensions of this supposed revolution.

4.2. Scale II: National Programming and the Promise of Land

Following the enactment of Law 1448 in October 2013, the Comptroller General of the Republic- (Contraloría General de la República- CGR) issued the “II Monitoring Report for the Land Restitution Process—CGR System of Indicators for the Follow-up and Monitoring of Land Restitution” [26]. For the CGR, in charge of supervising the transparency and good operations of the national treasury, the building of indicators was very important in providing a quantitative view of the advances of the public policy. It is not very difficult to deduce, therefore, that within the division of tasks of the national public powers, designed according to the neoliberal scheme in the New Public Management fashion, the government delegated the organism of fiscal control as the leading entity in charge of the evaluation of the implementation of the Victims Law. This, of course, means that the emphasis of this evaluation is marked by criteria of economic and technical efficiency, excluding other institutional arrangements that favor different evaluation logics.

The indicators formulated by the CGR are exclusively dedicated to quantifying the state of the land restitution processes. This has a very important impact on the everyday nature of the bureaucracy of the conflict. The Colombian government quickly created a battery of indicators that would reveal the state of the process. One that would show numbers, despite the fact that these numbers do not show great progress made in the redistributive transformation promised by the restitution. As shown in the Land Restitution Unit’s statistical report, only 2% of the land has changed hands. Despite this, the numbers look impressive but mean nothing. Indicators are always shown to have many numbers, numbers that are there to suggest that the government has “done something.” The management indicators are therefore related not only to the state of the process (advances in the bureaucratic procedure and indices for restituted or near-restituted lands: a success index) but also to the area in which the land was registered, where the claim was presented, where the land is located, and how long the claim has been in process (as context indicators).

Well... right, I know that for the government, what is important is the land. I understand it as a question of justice. They also want to know who took their land away because both the money and the guilty party are right there, or something like that. But what we see here, day in day out, is not a need for land. It is what people need to buy their food every day. What good is land? The people that come here are people who are uprooted already, and they don’t want to go back. But they need help here. That is the problem13.

Understood as an essential element of the law and its measurement factors, land is perceived with unease by the base-level public officials. Land synthesizes the desire held by others, an anxiety for alien justice. However, for the law, land itself does things. It is an agent. Public officials recognize that, in the letter of the law, the liberal spirit emerges to recognize that land brings dignity, freedom and autonomy. Land is therefore seen as a factor of development, of progress [27]. The naturalization of land as a dignifying agent at the center of the conflict is configured within the cultural production of the state, vis-à-vis the socialization of the law. Below are some of the images (Figure 2) in the frequently asked questions section of the Ministry of Agriculture’s leaflet on land restitution [28].

Figure 2.

The Ministry of Agriculture’s leaflet on land restitution.

In the images, land is turned into bodies. It merges with their heads, hearts, and chests, thus hiding the social relations that allow this value to be delivered, for this value to be linked to this type of accumulation and the inequalities that this belief hides. The legal discourse constructs these connections, linking the land with dignity and autonomy. From this liberal vision within which land produces development, as well as individual dignity, many already pivot around the subject of land as a human right [29]. For technocracy, as for early academic diagnoses, land encompasses a dignifying value with civilizing effects: it teaches us to be independent and economically valuable, it makes us responsible, and it makes us better citizens. Land turns us into “agents.”

Land also has great potential to generate results. One of the bureaucrats that were devising the control system for restitution management asserted this in the following terms:

The good thing about land is that you can measure it, quantify it. That’s why if you see the monitoring system indicators, they are given in terms of plots that are included, plots allocated through rulings, microfocused plots. The social programs are complex to measure, because it is difficult to see the capacities they generate in people. But not with land. Land is something you can count and say, look, this has advanced by x percent. This is very different14.

However, the fetish for land hides the social relations that construct these values. Works such as that of Sergio Latorre, for example, have been careful in showing the figure of formalization, in bureaucratic devices that are willing to reproduce hierarchies and exclusions. Land is an object that is “created” through public rituals, technologies of power, and dynamics of exclusion, that turn it into an object on a piece of paper (a deed), that gathers the pre-capitalist fiction of work, of agricultural production [30]. We set up the National System of Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims focusing on land. However, the ensuing scale of this work will bring to light the operational difficulties of this form of production of the meaning of the conflict in grassroots bureaucracies.

4.3. Scale III: Restitution and Street Level Bureaucrats

The robustness of the measurement tool designed in 2013 seems to rupture when we seek to monitor the lines of action or the execution processes: who measures these and when. The measurement imagines the state as a perfect Fordist production machine, in which everything is interlocked. Despite this, by 2014, the entities in charge of the restitution procedure had not reached capital cities like Cali, home to a greater flow of displaced people. In sum: there was no one to undertake the task. In Bogotá, they had already decided that the land had to be distributed but it was not clear how, where, and with what goal. Vis-à-vis this situation and provoked in part by the strong propaganda for the process launched from Bogotá, the bureaucracies in charge of the management and primary care for the victims and the displaced, the UAO, were suddenly in charge:

I was nervous. Imagine these people with these pamphlets, asking for a process. I remember that we called the Ministry of Agriculture in Bogotá several times and nothing happened. We’d say to the boss, look what’s going on; we’re getting this. You don’t know what to do. And nothing happened (…). This was before we got the thing from the Comptroller General, the measurement thing. But life is funny; we knew what to do (…). The person, who sits here, has to know that this work is not related to Law 1448. We are not here to take down declarations or to play a role. We are here to give these people life. This is social work. Look, at the very least, they need someone to listen to them. Ten minutes of concentrated listening, without typing, looking them in the eye. This gives them life and recognition. Poor people that come from god knows what, not from the countryside, like the government thinks. They are here and lost; they don’t know what to do here in their own city. For them, a minute in this chair is life. It is dignity. It is like when I go to the doctor to feel that I am important. It is believing that, for someone, they exist15.

Given all of its intricacies, the implementation of Law 1448 of 2011 suffered many setbacks and the restitution route did not happen naturally as an appendix of the victims’ one. Both became installed within the routes already traced by the little social bureaucracy existing at the time: that of the displaced. However, this contingency plan was not decided on, in the case of the Cali UAO, from Bogotá, or thought of as a more long-term articulation by the experts in the victims’ system. It was a solution that public officials of the UAO created to manage people’s expectations. This is what Vera calls bureaucratic experimentalism in the statehoods for peace [17].

Thus, in the text of the law, the UAO had no reason to be involved in the process to capture declarations in the restitution process, as, according to the norm, it is not obligatory for the victims of dispossession to be listed in the register for displaced persons. The latter is due to the fact that after 2012, it was no longer displaced persons that were counted but claimant victims (as the new political subjectivity created by Law 1448). This is only proof of dispossession or forced abandonment. For restitution to occur, the area of land has to be recorded in the Register for Presumably Forcibly Dispossessed or Abandoned Land, which is not managed by the UAO. Despite this, these bureaucracies anticipated the problems related to competencies:

Most of the time, people’s problem is poverty. Pain and suffering, of course. But this is not linked to a victimizing act, you see? Everyone comes here with this because they have to, but their tears roll out when they talk about not having anything to give their children to eat. They all come to tell this story, false sometimes, just so that they can get an application number. They have all been told that they have to leave here with a number in their hand, that they can then use to claim. But the problem is knowing what the number was for16.

The way in which the state interacts with people that seek to figure as beneficiaries of the victims’ protection framework is mediated by two actions: declaration and register. The victims declare their situation and the public officials include them in the right register. Here the state appears as a requesting body and administrator of information, whose organization has only one goal: to feed the centralized databases used to report the implementation of public policy17. In other words, the everyday work of the people that represent the state in the procedures dealing with victims is mediated by the indicators built to quantify their implementation. Currently, a person who seeks help within the framework of Law 1448 of 2011 is completely familiarized with the existence of three parallel registers: the Registry of Forcibly Dispossessed and Abandoned Land, managed by the Land Restitution Units; the Victims Registry, previously managed by Acción Social and currently by the Unit for Attention and Reparation of Victims; and the Single Registry of Displaced Populations.

The different registers appear the same. However, to figure in one or the other implies a different recognition with regards the public, a different negotiating power for the bureaucracy, and different possibilities to obtain aid and opportunities financed by the state. However, this information is not accessible to those that queue up at the UAO to wait their turn.

They told me I had to get a file number, that that was what I could use to find out how the case was going. My worry now is that I don’t have a telephone, and here everyone has been saying, since Wednesday when I first got here, that you have to give them a telephone number so that they can call you to tell you what happened. It seems they call when there is news. And the other thing is that it seems that if you are displaced because they take your home, it’s better... you get quicker results. I left my home, but no one took it from me, I left because I was afraid. So, I don’t know what I am going to do because it is better to say that they took it from you18.

As we can see in the CGR’s table of indicators, the story of the conflict established by the indicators is clear and derived from a systematization of the law that makes it easy to measure results. The conflict is a problem of lost lands, of people who had to leave because of the violence. These people are claiming restitution where they live now, because they want to go back to their land of origin. Thus, the indicators measure land, people going back to their land, and the time involved in the process. However, this approach to measuring the areas of land “included” and timescales is not that foolhardy. In terms of the former, the titling and identification of rural lands is subject to cadastral information that is not up to date [31]. Even if it were, there are various official reports that show that, over the last twenty years, land titling has been highly permeated by the conflict where the armed groups manage large waves of land formalization. With regards to the latter, the procedures and declarations collected in the regions have to be validated in Bogotá, thus producing a deceiving measurement of time, due to the many factors involved. Grassroots bureaucracies discuss the following:

Imagine. I have to fill in this table. It makes me laugh. I mean, if the success of the work has to do with the number of finished processes, we’re screwed, because this all goes to Bogotá and there, they compare things and there are tests, it doesn’t matter how long they take. So what? This is time (sic) against me (laughs). So, what I do is to deal with more people. Here the problem involves the people in the queues. So, what I say is, if you want us to be efficient, well—being efficient is to deal with more people, so here I have my daily limit. Ten, let’s say. Now, this has nothing to do with the result, because it depends on whether the people coming here are telling the truth and I don’t decide that. You see? This measures the process, it doesn’t measure me (…) they should do something that measures just me, what I do19.

By the end of 2017, the Unit had received a little over 100,000 restitution requests, of which approximately 42,000 had already been resolved: 18,000 had been admitted to trial before specialized judges and 24,000 had been rejected. Of those admitted, the judges had ruled on 4800 cases, 98% of which were won by the Unit, meaning that the results in terms of restitution are meager. However, grassroots bureaucracies spontaneously formulate the trouble spots of the policy.

While the baseline indicators are the same, they are specialized according to information focalization factors, or information search categories that the CGR detects as important. These focalization factors have to do with the victimizing act (rape, homicide of family members, massacres in places of origin, direct threats, demobilization of family members), victimizing actor (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia- FARC, Ejercito de Liberación Nacional- ELN, paramilitary groups), the generation and gender of the applicants and their region of origin. As described in the Land Restitution Units’ user manuals, such information selection factors are aligned to account for the implementation of the so-called differential approach, recognized as an “analytical and methodological tool that takes into account human needs and existing inequalities, allowing for the identification and visibility of specific vulnerabilities and infringements of populational groups and individuals that face particular situations of exclusion and/or discrimination” [28]. In fact, this focus develops Article 13 of Law 1448 of 2011, but there is profound disconnection between the public officials’ experience in their daily labor and that which the law “must measure.”

Well there are two worlds. They can’t say that this is designed to favor the vulnerable when they don’t even know what vulnerability is. On the contrary, this system excludes those who most need it. Sometimes, I feel like going to Bogotá and explaining this, because I will, no doubt, tell them how I fill this in. At the end of each month, when we have to send it in, I sit down and always put in the same numbers. I know that some of my colleagues here upload the number of victims served here, but that is not what they are asking for. So, you don’t have to put it in. So, what’s the indicator good for? An indicator of what? We don’t return land; we don’t do that. Look, I don’t understand these papers; don’t come here confusing me with these things about plots because that’s not what people’s problems are about. We listen to people. You can see, sometimes you have to spend the whole morning with one person. And do they measure that? No. They measure you if you let them (…). Anyway, these people don’t use the data for anything, the information that they need from us is the general number, those that have the total number of processes are the people in Bogotá. That’s why I’m saying it’s a waste of time20.

These bureaucracies therefore make tremendous efforts to make sense of the official processes, within operations that include registers, diagnoses and valuations. Despite having to deal with the contradictions and confusion of those that tell their stories, the bureaucracies are the main generators of figures and micro data in baselines that then serve to group results and justify social policies, programs and guidelines at different levels. However, this work has shown us that this last link of meaning within the bureaucratic mechanism has come loose. That the grassroots bureaucracies are invisible to the central scale technocracies (within the centers marked by the legal structure of the state) does not imply, however, that they are “marginal” to the citizenship. In fact, the opposite is true. What is contradictory about the way in which the state articulates itself is that, for the people, it is these grassroots bureaucracies that give meaning and coherence to the public, to the state and to the peace programs. In the visits, several victims spoke about the kind-hearted bureaucrats that “did them a favor,” that “defended them.” These bureaucrats narrate their work as follows.

These are our people. It’s them [the government] against us. This could have happened to me, to my family. I have experienced this close up. It’s all a lie. They want to make us believe that we are in the post-conflict, when the war is still apparent in every corner. So, what we have to do is make the best of it, you have to find the silver bullet, as they say. We have to help people. We are here to help21.

The bureaucracy holds this sense of “us” as a sort of militancy that fights to scratch out public resources for “its people” in spite of the too narrow focus on land restitution, it makes sense of the statehood that touches lives, that speaks of the public as an opportunity, and of the law as hope. At this scale, it is a supportive, protective statehood that is present for victims of all kinds, to open the labyrinths, uncover the holes and do its magic [32].

The affection that arises in the interaction between citizens and the state representatives could be seen even more clearly in scenarios where the state has a weak presence. In the absence of the state, bureaucrats see the need to help citizens in their claims for the restitution of their rights. And, in the impossibility of materializing these claims, the only alternative for the bureaucrats is to knit affective relations with the victims, while they wait to see whether the promise of restitution will ever be fulfilled. What occurs in Chocó is an example of this.

The Chocó Territorial Directorate operates in improvised spaces in people’s homes. The officials work at dining room tables along with three or four other colleagues, in rooms set up as offices, in studios and spaces that were once television rooms. The construction on the upper floors is not yet complete, and the grey work, is cluttered with papers and archive documents, framed within unpainted walls.

A few blocks away is the space provided by UARIV, using national resources, for assisting victims; a large glass box embedded in the center of the Pacífico region. The officials who work there usually arrive early to pray to God to support them in their daily work with victims. One of them expresses: “it is very painful to sit there and listen to people’s pain, so we ask God to give us the strength to go on.” There is no psychological support for the officials; it is only offered to the victims. However, they all have a computer ready to assist people who have been waiting their turn since dawn, to tell their stories, to verify that they are recognized in the RUV, to hear the good news that they will receive a subsidy.

In the Territorial Directorate office, I interviewed two territorial liaison officers who, on the basis of Excel tables, had long and precise explanations of the follow-up to local plans, which were conducted in scales and degrees of the “restoration of rights.”22 These officials also spoke of their work as being on a frontier: while their stories were full of vertical metaphors that reflected their perception of their insignificance in the face of a robust and powerful center (“the decision is made upstairs, by the people at the technical validation table in Bogotá,” “the big guys assume their commitment,” “I have to consult with the supervisor,” “the big heads are over there”), the reference to local interactions reflected anxiety with respect to the absence of power (“they come here and I can’t do anything”).

The “operation,” for the officials in the care cubicles, should last a maximum of fifteen minutes (or ten on peak days). It consists of taking the statement or referring the victim to the appropriate route. These same officials, in the afternoons, review the statements eagerly captured in the mornings and prepare the consignments for Bogotá. Everything is reviewed because “In Bogotá they are strict.” Many combine this direct work with the victims, often part-time, with evening activities on the other floors, which have occasional funding because they depend on different sources: empowerment workshops, training in relation to the care route, financial literacy workshops to learn how to handle money, and accompaniment in productive projects. Thus, while it is up to UARIV in Bogotá to maintain the exterior building and its first floor, the operation of the upper floors depends on the territorial entities (municipality and regional) and on the political agreements in force. This explains the irregularity of the programs and the feeling—at times—that the upper floors are simply not there.

Given the contingency of this financing, the first-floor employees themselves have taken on the task of finding a budget (or the financing itself) for one of the projects they consider essential. Thus, they collect money monthly to buy cardboard and markers to update the billboards, colored pencils to attend to the victims, and glue and glitter for the workshops. Handicrafts have become a popular reparation strategy that officials find very effective: “using your hands takes the pain out of your body and unloads your soul.” They say that they learned all of these techniques from expert Bogotá officials. The good thing is that, when the dynamic comes from Bogotá, there is money for refreshments and to give people “little treats.” These officials have designed a circuit for the children so that mothers or fathers who come to the office with their children do not have to make statements in their presence. “You have to look after the children,” says one of them.

In that logic, the walls of some of the floors are upholstered with bright billboards that recall the names of family members who died in one of the massacres that took place in the region, the land they should have left behind or the images and clippings for the “What I want for my life” exercise with their respective plan of action. This is how the last image of this journey consists of those glitter and glue posters, which are all signed by the victims of the conflict.

One of the unexpected findings of this research has to do with the penetration of urban militias of armed groups into the public offices providing care for the victims. Such spaces are already popular for “el tráfico de papas” or documents including threats made to the demobilized or the families that have already left the conflict zones or the neighborhoods where the urban militias operate. In Cali, many of the stories of those who queue up at these entities did not begin in the countryside but in the same comunas and city blocks, from which the members of the armed groups are expulsed for violating internal regulations, or for family related problems.

What is paradoxical about these findings is that they are not real “findings.” They are not something that the state does not know. Cali Town Hall recognized these phenomena [10] in last year’s “map of violence.” The monthly-reported security data account for the overflow of the violence in the cities and, for some years already, forensic medicine has been reporting more deaths caused by the conflict in cities than in combat in national territories23. There are enough data that support the limitation of the version of the conflict stabilized by the law and its indicators. Despite this, it seems that we all agree on having an idea of the conflict as being “far removed” from us.

Thus, this is how the law creates conflict and where indicators create reality. A fruit vendor on a mango stall also sells base testimonials. Everyone goes to him. These “base testimonials” are the key to “being recognized.” It does not matter if you are a real victim or pretending to be one to obtain state resources. What matters is that this testimonial serves to get you on a register.