Land Inequality Trends and Drivers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Why Land Inequality Matters

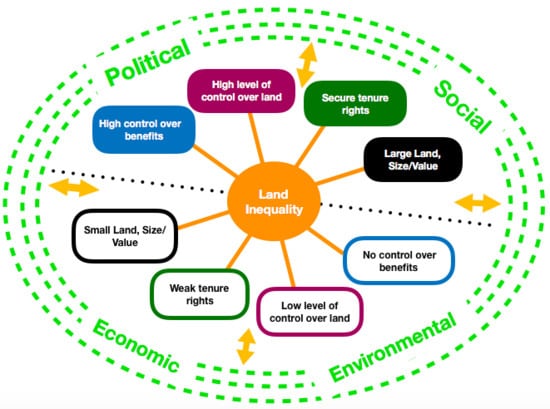

3. Understanding Land Inequality

Land Inequality, Further Considerations

4. The Data: What We Know and We Don’t Know

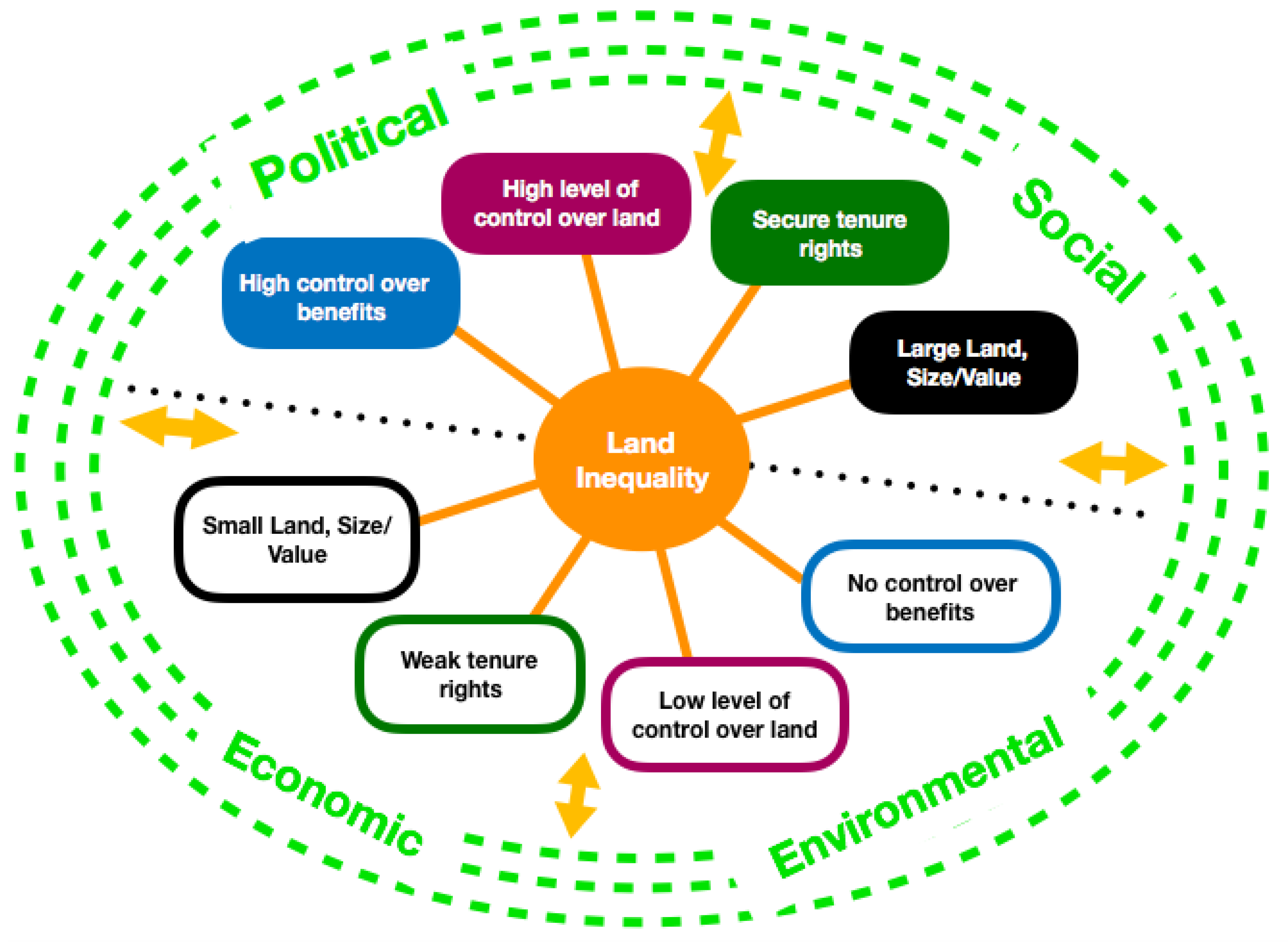

5. Trends and Drivers of Land Inequality

5.1. Historic Roots and the Extractivist Paradigm of Modernisation

5.2. A New Cycle of Accumulation by a Few

5.3. The Example of Tanzania

5.4. Less Visible Forms of Control over Land and the Value Produced

5.5. Elite and Corporate Policy Influence

5.6. Responses from Below

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture Statistical Pocketbook 2019; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Losch, B.; Fréguin-Gresh, S.; White, É.T. Structural dimensions of liberalization on agriculture and rural development: A cross-regional analysis on rural change. In Synthesis Report of the Ruralstruc Program; Cirad, World Bank, French Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Paris, France; Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture: Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A.; Doss, C.; Theis, S. Women’s land rights as a pathway to poverty reduction: Framework and review of available evidence. Agric. Syst. 2019, 172, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Hunger Index. Global Hunger Index 2019: The Challenge of Hunger and Climate Change; Helvetas: Dublin, Ireland; Bonn, Germany, 2019; Volume 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, M.; Saghai, Y. Food security, farmland access ethics, and land reform. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 12, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture: Leveraging Food Systems for Inclusive Rural Transformation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, J.W.; Malik, S.J. The Impact of Growth in Small Commercial Farm Productivity on Rural Poverty Reduction. World Dev. 2017, 91, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2010–2011: Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R. Property Rights for Poverty Reduction? In DESA Working Paper No. 91, December 2009; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.W. Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.R. Land Ownership Inequality and the Income Distribution Consequences of Economic Growth; UNU/WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- ECLAC. The Social Inequality Matrix in Latin America; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean: Santiago, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger-Mkhize, H.P.; Bourguignon, C.; van den Brink, R. Agricultural Land Redistribution: Towards Greater Consensus on the How; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Squire, L. New ways of looking at old issues: Inequality and growth. J. Dev. Econ. 1998, 57, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoloff, K.L.; Engerman, S.L. Institutions, factor endowments, and paths of development in the new world. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galor, O.; Moav, O.; Vollrath, D. Inequality in landownership, the emergence of human-capital promoting institutions, and the great divergence. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2009, 76, 143–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M. Land Reform in Developing Countries: Property Rights and Property Wrongs; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prosterman, R.L.; Riedinger, J.M. Land Reform and Democratic Development; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UN ESC. Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. In Statistical Commission Forty-Seventh Session; E/CN.3/2016/2/Rev.1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CEDAW. General recommendation No. 34 on the rights of rural women. In CEDAW/C/GC/34; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CFS. Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- African Union. Land Policy in Africa: A Framework to Strengthen Land Rights, Enhance Productivity and Secure Livelihoods; African Union and Economic Commission for Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- African Union. Declaration on land issues and challenges in Africa. In Assembly/AU/Decl.1(XIII) Rev.1; AU Commission: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Miranda, C. Critical reflections on the New Rurality and the rural territorial development approaches in Latin America. Agron. Colomb. 2014, 32, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S. The new rurality: Globalization, peasants and the paradoxes of landscapes. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebinck, P. De-/re-agrarianisation: Global perspectives. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 61, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C. Maturing Australia through Australian aboriginal narrative law. South Atl. Q. 2011, 110, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Andreucci, D.; García-Lamarca, M.; Wedekind, J.; Swyngedouw, E. Value grabbing: A political ecology of rent. Capital. Nat. Soc. 2017, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The New Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession. Soc. Regist. 2004, 40, 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, K.T. Feminism and Economic Inequality. Law Inequal. J. Theory Pract. 2017, 35, 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Leaving no one behind: The challenge of intersecting inequalities. In World Social Sciences Report, 2016, Challenging Inequalities: Pathways to a Just World; ISSC, IDS, UNESCO, Eds.; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, F. Horizontal Inequalities: A Neglected Dimension of Development; Working Paper Series; Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.T. Latin American Inequalities and Reparations. In The Social Life of Economic Inequalities in Contemporary Latin America; Ystanes, M., Strønen, I.Å., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- GRAIN. The Global Farmland Grab in 2016: How Big, How Bad? GRAIN: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R.; Adoko, J.; Siakor, A.; Salomao, A.; Auma, T.; Kaba, A.; Tankar, I. Protecting Community Lands and Resources: Evidence from Liberia, Mozambique and Uganda; Namati and International Development Law Organization (IDLO): Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anseeuw, W.; Wily, L.A.; Cotula, L.; Taylor, M. Land Rights and the Rush for Land: Findings from the Global Commercial Pressures on Land Research Project, 9789295093751; ILC: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif, M.C.A. An ethnographic exploration of food and the city. Anthropol. Today 2018, 34, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSM. Connecting Smallholders to Markets: An Analytical Guide. In International Civil Society Mechanism, Hands On the Land Alliance for Food Sovereignty; Civil Society Mechanism, World Committee on Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2016; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif, M.C.; Wiskerke, J.S. Exploring the Staple Foodscape of Dar es Salaam. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RRI. Who owns the World’s land? A Global Baseline of Formally Recognized Indigenous and Community Land Rights; Rights and Resources Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, F. Common Ground: Securing Land Rights and Safeguarding the Earth; Oxfam, International Land Coalition, Rights and Resources Initiative, Ed.; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giovarelli, R.; Richardson, A.; Scalise, E. Gender & Collectively Held Land: Good Practices & Lessons Learned from Six Global Case Studies; Landesa and Resource Equity: Seattle, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R.; Brinkhurst, M.; Vogelsang, J.; Namati’s Community Land Protection partner organizations. Community Land Protection Facilitators Guide; Namati Innovations in Legal Empowerment: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, A.M.; Springer, J. Recognition and respect for tenure rights. In NRGF Conceptual Paper; IUCN, CEESP and CIFOR: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cronkleton, P.; Larson, A. Formalization and collective appropriation of space on forest frontiers: Comparing communal and individual property systems in the Peruvian and Ecuadoran Amazon. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 28, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EGM on CSW 62. Report of the Expert Group Meeting on the CSW 62 Priority Theme: Challenges and Opportunities in Achieving Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Rural Women and Girls; UN Women: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, D.; Moussié, R. Making Care Visible: Women’s Unpaid Care Work in Nepal, Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya; ActionAid: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif, M.C. Feeding Dar es Salaam: A Symbiotic Food System Perspective; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guereña, A.; Wegerif, M.C.A. Framing Document on Land Inequality; ILC initiative International Land Coalition: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DRDLR. Land Audit Report: Phase Ii: Private Land Ownership By Race, Gender And Nationality. In November 2017, Version 2; Department of Rural Development and Land Reform: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lowder, S.K.; Skoet, J.; Raney, T. The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Dev. 2016, 87, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grain. Hungry for Land: Small Farmers Feed the World with Less than a Quarter of all Farmland; Grain: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Agricultural Land (sq. km). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.K2 (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Lowder, S.K.; Skoet, J.; Singh, S. What do we really know about the number and distribution of farms and family farms in the world? In Background Paper for the State of Food and Agriculture 2014; ESA Working Paper No. 14-02; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Farm Structures; European Union, DG Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, T.S.; Chamberlin, J.; Traub, L.; Sitko, N.; Muyanga, M.; Yeboah, F.K.; Anseeuw, W.; Chapoto, A.; Wineman, A.; Nkonde, C. Africa’s changing farm size distribution patterns: The rise of medium-scale farms. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Farm structure statistics. In Eurostat: Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S. Land grabbing and land concentration in Europe. Res. Brief. Amst. Transnatl. Inst. 2016. Available online: https://www.tni.org/en/publication/land-grabbing-and-land-concentration-in-europe (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- De Schutter, O. We Want Peasants; Land Portal: 2018. Available online: https://landportal.org/blog-post/2018/09/we-want-peasants (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Nolte, K.; Chamberlain, W.; Giger, M. International Land Deals for Agriculture: Fresh Insights from the Land Matrix: Analytical Report II; Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement (CIRAD), German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), University of Pretoria, Bern Open Publishing (BOP): Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guereña, A. A Snapshot of Inequality: What the Latest Agricultural Census Reveals about Land Distribution in Colombia; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Number and Area of Holdings, and Gini’s Index of Concentration: 1990 Round of Agricultural Censuses. Available online: http://www.fao.org/economic/the-statistics-division-ess/world-census-of-agriculture/additional-international-comparison-tables-including-gini-coefficients/table-1-number-and-area-of-holdings-and-ginis-index-of-concentration-1990-round-of-agricultural-censuses/en/ (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Guereña, A. Unearthed: Land, Power, and Inequality in Latin America; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Land Matrix. Available online: https://landmatrix.org (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Gebrekidan, S.; Apuzzo, M.; Novak, B. The Money Farmers: How Oligarchs and Populists Milk the E.U. for Millions. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/03/world/europe/eu-farm-subsidy-hungary.html (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Asiama, K.; Bennett, R.; Zevenbergen, J. Land consolidation on Ghana’s rural customary lands: Drawing from The Dutch, Lithuanian and Rwandan experiences. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 56, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, D.; Stillwell, J.; See, L. A new methodology for measuring land fragmentation. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2013, 39, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T. Dealing with Central European Land Fragmentation; Eburon: Delft, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C.R.; Kovarik, C.; Peterman, A.; Quisumbing, A.; van den Bold, M. Gender Inequalities in Ownership and Control of Land in Africa: Myths versus Reality; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Gender and Land Rights. In Economic and Social Perspectives; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; Volume 2015, p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.D.; León, M. The gender asset gap: Land in Latin America. World Dev. 2003, 31, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, J.-C.; Dick, L.; Bizoza, A. The Gendered Nature of Land and Property Rights in Post-Reform Rwanda; USAID|LAND Project: Kigali, Rwanda, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Progress of the World’s Women 2015–2016: Transforming Economies, Realizing Rights; United Nations Women: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Governing Land for Women and Men: A Technical Guide to Support the Achievement of Responsible Gender-Equitable Governance of Land Tenure; Food and Agriculture Organisation: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.D.; León, M. Género, Propiedad y Empoderamiento: Tierra, Estado y Mercado en América Latina; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Gender and Land Rights Database: Gender and Land Statistics. Available online: http://www.fao.org/gender-landrights-database/data-map/statistics/en/ (accessed on 19 January 2019).

- Ledger, T. An Empty Plate: Why We Are Losing the Battle for Our Food System, Why It Matters, and How We Can Win It Back; Jacana Media: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif, M.; Russell, B.; Grundling, I. Still Searching for Security: The Reality of Farm Dweller Evictions in South Africa; Nkuzi Development Association: Polokwane, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit, A. Forgotten by the highway: Globalisation, adverse incorporation and chronic poverty in a commercial farming district of South Africa. Chronic Poverty Dev. Policy 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jayne, T.S.; Yamano, T.; Weber, M.T.; Tschirley, D.; Benfica, R.; Chapoto, A.; Zulu, B. Smallholder income and land distribution in Africa: Implications for poverty reduction strategies. Food Policy 2003, 28, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; UN-Habitat. On Solid Ground: Addressing Land Tenure Issues after Natural Disasters; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Giridharadas, A. Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World; Alfred, A., Ed.; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, D.A.V.; Aymar, I.M.; Lawson, M. Reward Work, Not Wealth; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McKinley, D.T. South Africa’s Corporatised Liberation: A Critical Analysis of the ANC in Power; Jacana: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani, M. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996; p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- Rodney, W. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa; Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Frankema, E. The colonial roots of land inequality: Geography, factor endowments, or institutions? Econ. Hist. Rev. 2010, 63, 418–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockett, C.D. Measuring political violence and land inequality in Central America. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1992, 86, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P.; Garcia, A.; Garcia, A. Elite Transition-Revised and Expanded Edition: From Apartheid to Neoliberalism in South Africa; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, T. Indigenous peoples, land tenure and land policy in Latin America. In Land Reform, Land Settlement and Cooperatives; FAO, Ed.; Food and Agrciulture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- Global Witness. At What Cost? Irresponsible Business and the Murder of Land and Environmental Defenders in 2017; Global Witness: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Byerlee, D. Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can It Yield Sustainable and Equitable Benefits? The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandratos, N.; Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision; ESA Working Paper No. 12-03; Agricultural Development Economics Division, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Corley, R. How much palm oil do we need? Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, O. How not to think of land-grabbing: Three critiques of large-scale investments in farmland. J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlet, M. Agricultura y Alimentación en Cuestión: Las tierras cultivables no cultivadas en el mundo. In Las Notes de la C2A; AGTER: Nogent-sur-Marne, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L. Land Grab or Development Opportunity? Agricultural Investment and International Land Deals in Africa; Iied: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Franco, J.C.; Kay, C.; Spoor, M. Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean, viewed from a broader international perspective. In The Land Market in Latin America and the Caribbean: Concentration and Foreignization; Gómez, S., Ed.; Food and Agriculture Organzation of the United Nations: Santiago, Chile, 2014; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Land Matrix. Available online: https://landmatrix.org/global/ (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Nolte, K.; Chamberlain, W.; Giger, M. International Land Deals for Agriculture. Fresh insights from the Land Matrix: Analytical Report II; Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern, Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement; German Institute of Global and Area Studies, University of Pretoria, Bern Open Publishing: Bern, Switzerland; Montpelier, VT, USA; Hamburg, Germany; Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lowder, S.K.; Bertini, R.; Karfakis, P.; Croppenstedt, A. Transformation in the size and distribution of farmland operated by household and other farms in select countries of sub-Saharan Africa. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 23–26 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sulle, E.; Hall, R. Reframing the New Alliance Agenda: A Critical Assessment Based on Insights from Tanzania; Future Agricultures. 2013. Available online: https://www.future-agricultures.org/publications/policy-briefs-document/reframing-the-new-alliance-agenda-a-critical-assessment-based-on-insights-from-tanzania/ (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- SAGCOT. Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania: Investment Blue Print; AgDevCo, Prorustica, Eds.; SAGCOT: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif, M.C.A.; Martucci, R. Milk and the city: Raw milk challenging the value claims of value chains. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerif, M.C.A.; Hebinck, P. The Symbiotic Food System: An Alternative’Agri-Food System Already Working at Scale. Agriculture 2016, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.T.; Lewis, J. The Maize Value Chain in Tanzania: A Report from the Southern Highlands Food Systems Programme; Food and Agriculure Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chachage, C.; Baha, B. Accumulation by Land Dispossession and Labour Devaluation in Tanzania: The Case of Biofuel and Forestry Investments in Kilwa and Kilolo; Land Rights Research and Resources Institute (LARRRI/HAKIARDHI) and Oxfam: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- PINGO’s Forum. Eviction of Pastoralists from Kilombero and Rufiji Valleys, Tanzania; PINGO’s Forum: Arusha, Tanzania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, J.W. Pro-Poor Growth: The Relation between Growth in Agriculture and Poverty Reduction. Prepared for USAID/G/EGAD. 1999. Available online: http://agronor.org/Mellor1.htm (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Adamopoulos, T.; Restuccia, D. Land Reform and Productivity: A Quantitative Analysis with Micro Data; 0898-2937; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lannen, A.; Bieri, S.; Bader, C. Inequality: What’s in a word? In CDE Policy Brief, No. 14; CDE: Bern, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The enigma of capital and the crisis this time. In Proceedings of the American Sociological Association Meetings, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the 21st Century; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ducastel, A.; Anseeuw, W. Facing financialization: The divergent mutations of agricultural cooperatives in postapartheid South Africa. J. Agrar. Chang. 2018, 18, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.; Isakson, S.R. Speculative Harvests: Financialization, Food, and Agriculture; Practical Action: Rugby, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ducastel, A.; Anseeuw, W. Agriculture as an asset class: Reshaping the South African farming sector. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakson, S.R. Food and finance: The financial transformation of agro-food supply chains. J. Peasant. Stud. 2014, 41, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.; Helleiner, E. Troubled futures? The global food crisis and the politics of agricultural derivatives regulation. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2012, 19, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valoral Advisors. 2018 Global Food & Agriculture Investment Outlook: Investing Profitably Whilst Fostering a Better Agriculture; Valoral Advisors: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valoral Advisors. 2015 Global Food & Agriculture Investment Outlook: Institutional Investors Meet Farmers; Valoral Advisors: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GRAIN. The Global Farmland Grab by Pension Funds Needs to Stop; GRAIN. 2018. Available online: https://www.grain.org/en/article/6059-the-global-farmland-grab-by-pension-funds-needs-to-stop (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- BankTrack. About BankTrack. Available online: https://www.banktrack.org (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Kaplinsky, R. Introduction: Globalisation, value chains and development. IDS Bull. 2001, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seville, D.; Buxton, A.; Vorley, B. Under What Conditions are Value Chains Effective Tools for Pro-Poor Development. Available online: http://pubs.iied.org/16029IIED.html (accessed on 21 August 2011).

- Tapela, B.N. Livelihoods in the wake of agricultural commercialisation in South Africa’s poverty nodes: Insights from small-scale irrigation schemes in Limpopo Province. Dev. S. Afr. 2008, 25, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.; Navas-Alemán, L. Value Chains, Donor Interventions and Poverty Reduction: A Review of Donor Practice; 2040-0217; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2010; pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Minten, B.; Randrianarison, L.; Swinnen, J.F.M. Global retail chains and poor farmers: Evidence from Madagascar. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, W.; Anseeuw, W. Inclusive businesses and land Reform: Corporatization or transformation? Land 2018, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, S.; Guereña, A. Land inequality and power in Latin America. In Proceedings of the Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 20–24 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, S.; Du Toit, A. Adverse Incorporation, Social Exclusion, and Chronic Poverty. In Chronic Poverty: Concepts, Causes and Policy; Sheperd, A., Brunt, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 134–159. [Google Scholar]

- Amanor, K.S.; Chichava, S. South–south cooperation, agribusiness, and African agricultural development: Brazil and China in Ghana and Mozambique. World Dev. 2016, 81, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care. Sustainable Dairy Value Chains; Care: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing, A.; Roy, S.; Njuki, J.; Tanvin, K.; Waithanji, E. Can dairy value-chain projects change gender norms in rural Bangladesh? In Impacts on Assets, Gender Norms, and Time Use; IFPRI & ILRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos, S.; Knorringa, P.; Evers, B.; Visser, M.; Opondo, M. Shifting regional dynamics of global value chains: Implications for economic and social upgrading in African horticulture. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 1266–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Gereffi, G. Global value chains, rising power firms and economic and social upgrading. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2015, 11, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Kaplinsky, R.; Morris, M. Rents, power and governance in global value chains. J. World Syst. Res. 2018, 24, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochet, H. Capital–labour separation and unequal value-added distribution: Repositioning land grabbing in the general movement of contemporary agricultural transformations. J. Peasant. Stud. 2018, 45, 1410–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochet, H.; Merlet, M. Land grabbing and share of the value added in agricultural processes. A new look at the distribution of land revenues. In Proceedings of the International Academic Conference Global Land Grabbing, Brighton, UK, 6–8 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Agbiz. Legislation. Available online: https://agbiz.co.za/legislation/sa-s-legislation-process (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Oxfam Brasil. Terrenos da Desigualdade: Terra, Agricultura e Desigualdades no Brasil Rural; Oxfam Brasil: Sao Paulo, Brasil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kiai, M. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association; A/HRC/29/25; Human Rights Council, United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, R.; Bonacich, E.; Quan, K. The End of Apparel Quotas: A Faster Race to the Bottom? In Institute for Social, Behavioral, and Economic Research, Center for Global Studies; University of California: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau, F. The Highest Bidder Takes It All: The World Bank’s Scheme to Privatize the Commons; The Oakland Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Enabling the Business of Agriculture 2017; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Prével, A.; Mousseau, F. The Unholy Alliance: Five Western Donors Shape a Pro-Corporate Agenda for African Agriculture; The Oakland Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby, R. Moral Hazard? Mega Public-Private Partnerships in African Agriculture; Oxfam International: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Front Line Defenders. Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2018; Front Line, the International Foundation for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, K. Our Land, our Lives: Time out on the Global Land Rush; Oxfam International: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.J. Agricultural Investments for Development in Tanzania: Reconciling Actors, Strategies and Logics? Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Faculty of Landscape and Society: Akershus, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CCSI. Land Deal Dilemmas: Grievances, Human Rights, and Investor Protections; Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment: Bogota, Columbia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tauli-Corpuz, V. The impact of international investment and free trade on the human rights of indigenous peoples. In Report to the General Assembly A/70/301; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L. Land Rights and Investment Treaties: Exploring the interface London, UK; International Institute for Environment and Development and Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, J.; Gistelinck, M.; Karbala, D. Sleeping Lions: International investment treaties, state-investor disputes and access to food, land and water. In Oxfam Policy and Practice: Agriculture, Food and Land; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi-Osterwalder, N.; Smaller, C. Farmland Investments Are Finding their Way to International Arbitration. In International Institute for Sustainable Development; IISD: Winnipeg, ON, Canada, 2017; Volume 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.; Cordes, K. Not So Sweet: Tanzania Confronts Arbitration over Large-Scale Sugarcane and Ethanol Project. In Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment; Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ICSID. EcoDevelopment in Europe AB & Others v. United Republic of Tanzania (ICSID Case No. ARB/17/33). Available online: https://icsid.worldbank.org/en/Pages/cases/casedetail.aspx?caseno=ARB/17/33 (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Masih, N. India Orders Staggering Eviction of 1 Million Indigenous People. In Some Environmentalists are Cheering; Washington Post: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, J. The Tribes Paying the Brutal Price of Conservation. The Guardian, 28 August 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/aug/28/exiles-human-cost-of-conservation-indigenous-peoples-eco-tourism (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- RRI. Toward a Global Baseline of Carbon Storage in Collective Lands: An Updated Analysis of Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Contributions to Climate Change Mitigation; Rights and Resources Initiative, Woods Hole Research Center, World Resources Institute, Eds.; Rights and Resources Initiative: Washington DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fratkin, E.; Mearns, R. Sustainability and pastoral livelihoods: Lessons from East African Maasai and Mongolia. Hum. Organ. 2003, 62, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostindie, H. Unpacking Dutch multifunctional agrarian pathways as processes of peasantisation and agrarianisation. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 61, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; van der Ploeg, J.D.; Hebinck, P. Reconsidering the contribution of nested markets to rural development. In Rural Development and the Construction of New Markets; Hebinck, P., van der Ploeg, J.D., Schneider, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 190–205. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Jingzhong, Y.; Schneider, S. Rural development through the construction of new, nested, markets: Comparative perspectives from China, Brazil and the European Union. J. Peasant. Stud. 2012, 39, 133–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebinck, P.; Mtati, N.; Shackleton, C. More than just fields: Reframing deagrarianisation in landscapes and livelihoods. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 61, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satgar, V. The Solidarity Economy Alternative: The Crises of Global Capitalism and the Solidarity Economy Alternative; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Giménez, E.; Altieri, M.A. Agroecology, food sovereignty, and the new green revolution. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Campesina, L.V. Defending Food Sovereignty. Available online: http://www.viacampesina.org/en/index.php/organisation-mainmenu-44 (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Regenvanu, R. The traditional economy as source of resilience in Vanuatu. In Defence of Melanesian Customary Land; Anderson, T., Lee, G., Eds.; Aid/Watch: Sydney, Australia, 2010; pp. 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. The New Peasantries: Struggles for Autonomy and Sustainability in an Era of Empire and Globalization; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. World Programme for the Census of Agriculture 2020. Volume 2 Operational Guidelines; FAO Statistical Development Series; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. World Programme for the Census of Agriculture 2020. Volume 1 Programme, Concepts and Definitions; FAO Statistical Development Series; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017; p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- IAEG-SDG. SDG Indicator 1.4.2 Metadata Document 12th February 2018; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/files/Metadata-01-04-02.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- IAEG-SDG. SDG Indicator 5.a.2 Metadata Document 12th February 2018; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/files/Metadata-05-0A-02.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- IAEG-SDG. SDG Indicator 5.a.1 Metadata Document 16th October 2017; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/files/Metadata-05-0a-01.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2020).

| Land Sizes in Hectares (Ha) | Number of Households (HHs)/Owners | Area Operated (AO) Ha | Share of HHs | Share AO | Average Size Ha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 996,519 | 585,002 | 28.3% | 7.5% | 0.59 |

| 1–2 | 1,148,476 | 1,596,699 | 32.6% | 20.4% | 1.39 |

| 2–5 | 1,092,166 | 3,257,027 | 31.0% | 41.5% | 2.98 |

| 5–10 | 225,369 | 1,476,402 | 6.4% | 18.8% | 6.55 |

| 10–20 | 53,685 | 714,745 | 1.5% | 9.1% | 13.31 |

| 20–50 | 8,431 | 211,144 | 0.2% | 2.7% | 25.04 |

| 50–100 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 100–200 | 0 | 0 | |||

| >200 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Totals | 3,524,646 | 7,841,019 | 100.0% | 2.22 |

| Land Sizes in Hectares (Ha) | Number of Households (HHs)/Owners | Area Operated (AO) Ha | Share of HHs | Share AO | Average Size Ha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 2,451,115 | 1,270,104 | 37.2% | 7.7% | 0.52 |

| 1–2 | 1,730,862 | 2,380,369 | 26.3% | 14.4% | 1.38 |

| 2–5 | 1,880,628 | 5,848,818 | 28.5% | 35.3% | 3.11 |

| 5–10 | 368,973 | 2,503,873 | 5.6% | 15.1% | 6.79 |

| 10–20 | 105,913 | 1,442,112 | 1.6% | 8.7% | 13.62 |

| 20–50 | 46,584 | 1,260,933 | 0.7% | 7.6% | 27.07 |

| 50–100 | 3,995 | 293,497 | 0.1% | 1.8% | 73.47 |

| 100–200 | 3,781 | 491,928 | 0.1% | 3.0% | 130.11 |

| Sub-Totals | 6,591,851 | 15,491,634 | 2.35 | ||

| >200 (Land Matrix) | 108 | 1,068,540 | 0.0% | 6.5% | 9,893.89 |

| Totals with Land Matrix data | 6,591,959 | 16,560,174 | 100.0% | 2.51 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wegerif, M.C.A.; Guereña, A. Land Inequality Trends and Drivers. Land 2020, 9, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040101

Wegerif MCA, Guereña A. Land Inequality Trends and Drivers. Land. 2020; 9(4):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040101

Chicago/Turabian StyleWegerif, Marc C. A., and Arantxa Guereña. 2020. "Land Inequality Trends and Drivers" Land 9, no. 4: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040101

APA StyleWegerif, M. C. A., & Guereña, A. (2020). Land Inequality Trends and Drivers. Land, 9(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040101