Environmental Regulations, the Industrial Structure, and High-Quality Regional Economic Development: Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Mechanism

3.1. Classification of Environmental Regulations

3.1.1. Command-and-Control Environmental Regulation

3.1.2. Market Incentive Environmental Regulation

3.1.3. Voluntary Participation in Environmental Regulation

3.2. Analysis of the Mechanisms by Which Environmental Regulations Drive Industrial Upgrading

3.2.1. Crowding Out Mechanism

3.2.2. Green Barriers to Entry

3.2.3. Openness to Trade

4. Measurement Model Construction, Data Sources, and Variable Selection

4.1. Measurement Model Construction

4.2. Data Sources

4.3. Variable Selection and Processing

- (1)

- Level of economic development (le): The article uses the logarithm of per capita GDP to measure economic development, and per capita GDP is deflated to values for the year 2000.

- (2)

- Stability of economic development (st): The stability of economic development means that the speed of economic development fluctuates within a moderate range so that resources can be fully utilized. According to the AS-AD model, if the economy grows too quickly and aggregate demand is excessively high, it will usually lead to inflation; if the economy grows too slowly and aggregate demand is insufficient, it will usually lead to unemployment. Therefore, the more stable the economic development, the higher the quality of economic development. This article uses two secondary indicators to measure stability, the CPI and the urban-registered unemployment rate.

- (3)

- Sustainability of economic development (su): The sustainability of economic development is the main factor that distinguishes the quality of economic development from the pattern of economic growth. Economic development inevitably leads to environmental pollution. If economic development cannot be sustained, it will inevitably cause serious damage to the ecological environment, and these negative consequences will, in turn, hinder the quality of economic development. This article uses three secondary indicators to measure this, which are the green coverage of completed areas, per capita public area of green land, and pollution intensity. Pollution intensity is calculated by the entropy weighting method using three indicators: per capita volume of industrial waste water discharged (su1), per capita volume of sulfur dioxide emissions by the industry (su2), and per capita emission of industrial soot and dust (su3). The following describes the specific steps followed in the entropy weighting method to calculate pollution intensity.

5. Analysis of Results

5.1. HDI Partition Analysis and Characteristics

5.1.1. Comparison Based on the HDI Partition

5.1.2. Analysis of the Results for Provinces with HDI Values above the National Average

5.1.3. Analysis of the Results for Provinces with HDI Values below the National Average

5.2. Robustness Test

5.2.1. Full Sample Testing

5.2.2. Substitute Variable Test (GDP)

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- (1)

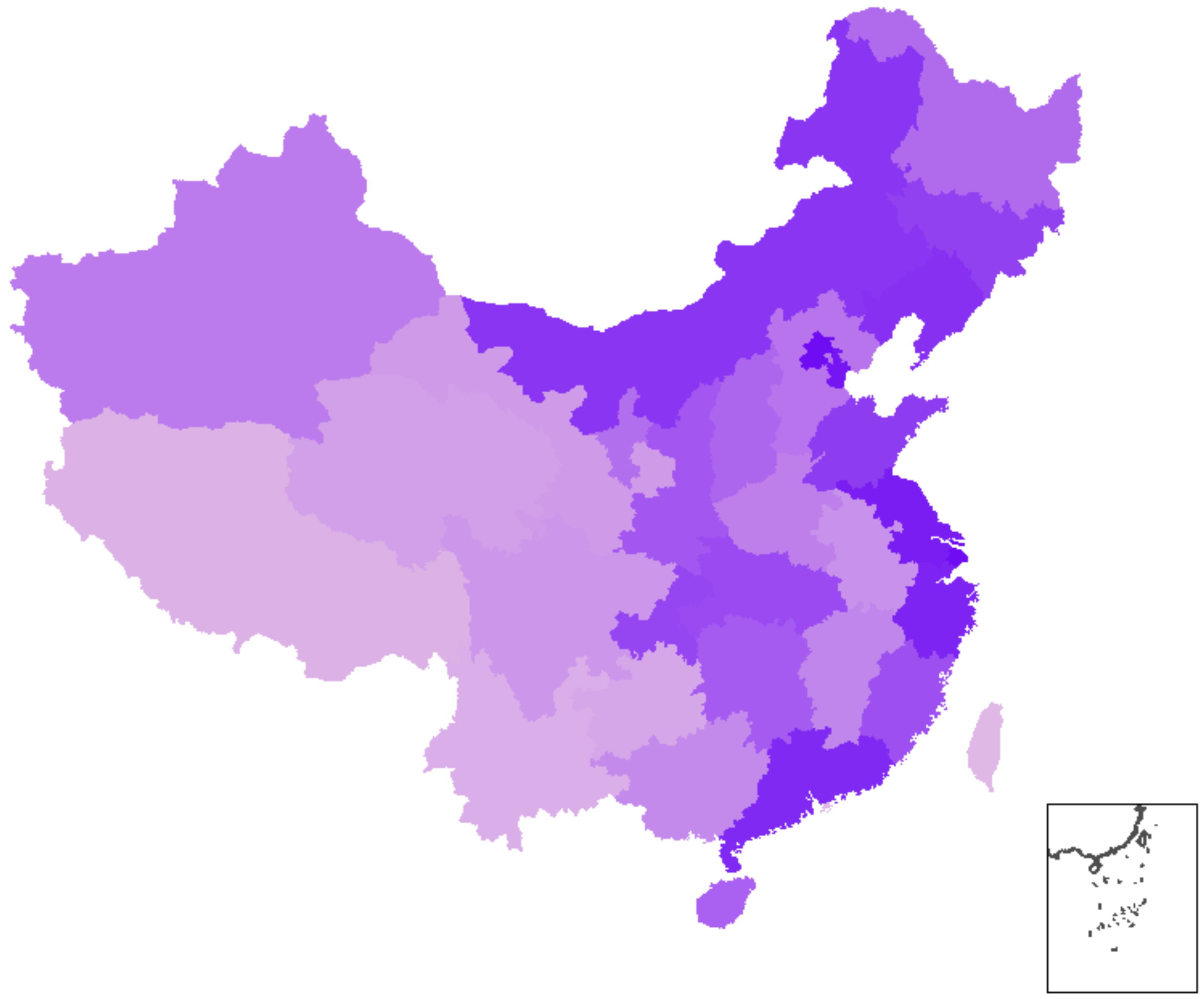

- The same intensity of environmental regulations in regions with different HDI levels has different effects on the quality of economic development. The development of different provinces in China is extremely imbalanced. Limited by the influence of natural endowments and strategic positions, the economic development of the central and western regions is not as high as that of the eastern region. However, environmental regulations in provinces with above average HDI values and below average HDI values show the same trend in the quality of economic development. Moreover, the mediating effect of the industrial structure on environmental regulations is greater in areas with below average HDI values.

- (2)

- Environmental regulations in provinces with above average HDI values have a negative impact on the quality of regional economic development. The cross-term between environmental regulations and the industrial structure has a significantly positive impact on the quality of regional economic development. The mechanism underlying the effect of environmental regulations on the quality of economic development is mainly the transformation and upgrading of the industrial structure. Reasonable environmental regulations can motivate enterprises to transform and upgrade. Highly polluting enterprises are eliminated through the survival of the fittest mechanism, and social resources are transferred to clean technology industries. This promotes the transfer of resources from the primary and secondary industries to the tertiary industry, optimizes the industrial structure, and promotes high-quality economic development.

- (3)

- Environmental regulations in provinces with below average HDI values have a positive impact on the quality of regional economic development, but the effect is not significant at the 10% level. This shows that environmental regulations play a minor role in determining economic development quality. After the introduction of the cross-terms, environmental regulations and industrial structure are found to have a negative impact on the quality of regional economic development. Cross-terms between environmental regulation and industrial structure have a significantly positive impact on the quality of regional economic development. Moreover, the mediating effect of the industrial structure on environmental regulations is greater in low HDI regions than in high HDI regions. This shows that the mechanism underlying the effect of environmental regulations on high-quality economic development is the industrial structure. In addition, the current intensity of environmental regulations is insufficient, and the intensity of environmental regulations should be increased.

- (1)

- Increase the intensity of environmental regulations by industry. The interaction between environmental regulation adjustment and industrial structure upgrading can promote high-quality economic development. However, the development of different industries is uneven, and the direction of industrial structure adjustment is also different. For example, the manufacturing industry needs to be adjusted from an extensive labor force development to a technology-intensive development. Therefore, policymakers are required to refine environmental regulations by industry and adopt environmental regulations that are most suitable for the development of the industry. In addition, some high-polluting industries should formulate more stringent environmental regulations and policies to help the industry cross the inflection point of the U-shaped curve as soon as possible to promote high-quality economic development by optimization and upgrading of the industrial structure.

- (2)

- Local governments need to grasp the positive effects of environmental regulations on the upgrading of industrial structure, and guide healthy competition in environmental regulations among regions. Regional development in China is uneven, especially the economic development between the eastern and western parts of the country. Local governments must take into account the actual local conditions when formulating environmental regulations and policies. Regions above the national average HDI should sum up their experience, and regions below the national average HDI should strengthen environmental regulations. The local government should adjust measures to local conditions, tilt resources to green development industries, vigorously introduce technical talents, and gradually adjust the structure of pollution-intensive industries.

- (3)

- Actively play the role of green technological innovation in promoting the upgrading of industrial structure. Talent is the foundation of innovation. The Chinese government should vigorously cultivate high-level green innovative talents, continuously invest in green innovative technologies, and accelerate the advancement and rationalization of the industrial structure.

- (4)

- Improve public awareness of environmental protection. Environmental protection is not an individual’s business. It requires the economic participation of all sectors of society, and ordinary people are also an important part of that. As consumers, we resolutely refuse to purchase goods produced by highly polluting technologies. This can fundamentally increase the enthusiasm of enterprises and enhance their environmental responsibility. At the same time, the government also encourages institutional and technological innovation and strengthens the role of enterprises as the main body and main force of technological innovation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tongbin, Z.; Qi, Z.; Qingquan, F. Research on Corporate Governance Motivation and Public Participation Externalities under Government Environmental Regulation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 36–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Burton, D.M.; Gomez, I.A.; Love, H.A. Environmental regulation cost and industry structure changes. Land Econ. 2011, 3, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.; Qin, C.; Ye, X. Environmental regulation, economic network and sustainable growth of urban agglomerations in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eiadat, Y.; Kelly, A.; Roche, F.; Eyadat, H. Green and competitive? An empirical test of the mediating role of environmental innovation strategy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.A.; Brem, A. Antecedents of corporate environmental commitments: Te role of customers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, W.B.; Shadbegian, R.J. Plant vintage, technology, and environmental regulation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2013, 46, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ling, L.I.; Feng, T.A.O. Selection of Optimal Environmental Regulation Intensity for Chinese Manufacturing Industry—Based on the Green TFP Perspective. China Ind. Econ. 2012, 5, 70–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Papalia, R.B.; Bertarelli, S. Nonlinearities in economic growth and club convergence. Empir. Econ. 2013, 44, 1171–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telle, K.; Larsson, J.D.O. Environmental regulations hamper productivity growth? How accounting for improvements of plants’ environmental performance can change the conclusion. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, R.; Withagen, C. Green growth, green paradox and the global economic crisis. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 6, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, S.; Fan, Z. Modeling the role of environmental regulations in regional green economy efficiency of China: Empirical evidence from super efficiency. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, T.; Li, J.; Sha, R.; Hao, X. Environmental regulations, financial constraints and export green-sophistication: Evidence from China’s enterprises. J. Clean. Product. 2020, 251, 119671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Managi, S.; Kumar, P. Inclusive Wealth Report 2018; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; McGahan, A.M.; Prabhu, J. Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellala, P.S.; Madala, M.K.; Chhattopadhyay, U. A theoretical model for inclusive economic growth in Indian context. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Oyinlola, M.A.; Adedeji, A.A.; Bolarinwa, M.O.; Olabisi, N. Governance, domestic resource mobilization, and inclusive growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Econ. Anal. Pol. 2020, 65, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalles, J.T.; Mello, L.D. Cross-country evidence on the determinants of inclusive growth episodes. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2019, 23, 1818–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajapaksa, D.; Islam, M.; Managi, S. Natural capital depletion: The impact of natural disasters on inclusive growth. Econ. Disasters Clim. Chang. 2017, 1, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Kreuger, A.B. Economic growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Bank. World Development Report 1992: Development and Environment; China Financial and Economic Press: Beijing, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, G.; Di Battista, T.; Gattone, S.A. A Micro-level Analysis of Regional Economic Activity through a PCA Approach. In Decision Economics: Complexity of Decisions and Decisions for Complexity. DECON 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 1009; Bucciarelli, E., Chen, S.H., Corchado, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Morone, P. A New Socio-economic Indicator to Measure the Performance of Bioeconomy Sectors in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 106724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, M.L. Prices vs. quantities. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1974, 41, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, J. Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on “green” productivity: Evidence from China. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.W. The political economy of environmental regulation: Towards a unifying framework. Public Choice 1990, 65, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietenberg, T.H.; Lewis, L. Environmental and Natural Resource Economics; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R.W. Market power and transferable property rights. Q. J. Econ. 1984, 99, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Guidelines for the Application of Environmental Economic Instruments; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 1994; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pigou, A.C. The Economics of Welfare; MacMillan: London, UK, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Stavins, R.N. Market-Based Environmental Policies. Public Policies Environ. Prot. 2007, 2, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, A. Environmental regulations and industry location: International and domestic evidence. Fair Trade Harmon. Prerequisites Free Trade 1996, 1, 429–457. [Google Scholar]

- Antweiler, W.; Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Is free trade good for the environment? American Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 877–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baoping, R.; Fengan, W. Judgment criteria, determinants and realization methods of China’s high-quality development in the new era. Reform 2018, 4, 5–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z. Research on the Quality Measurement of the Economic Development of the Yangtze River Economic Zone; China University of Geosciences: Wuhan, China, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiurui, X.; Gang, W.; Xiaoan, Z.; Jianguo, S.; Deyong, S. Research advances in assessment of green GDP indicator. Chinese J. Ecol. 2007, 26, 1107–1113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Taosheng, S.; Jinbin, W. On the integration between ecology and economics based on sustainable development. Econ. Surv. 2001, 18, 13–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, V. Alternative Economic Indicators; Rutledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Study Group on Sustainable Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences. 1999 Report on China’s Sustainable Development Strategy; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gorgij, A.D.; Kisi, O.; Moghaddam, A.A.; Taghipour, A. Groundwater quality ranking for drinking purposes, using the entropy method and the spatial autocorrelation index. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Wei, X.; Huang, Q. Comprehensive entropy weight observability-controllability risk analysis and its application to water resource decision-making. Water SA 2012, 38, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, G.; Shen, J.; Jia, Y.; Sun, F. Comprehensive evaluation of water resource security: Case study from Luoyang City, China. Water 2018, 10, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, J.; An, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. Using fuzzy theory and information entropy for water quality assessment in Three Gorges region, China. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 2517–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Rezaei, M.; Sohrabi, N. Groundwater quality assessment using entropy weighted water quality index (EWQI) in Lenjanat, Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 3479–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartzokas, A.; Yarime, M. Technology Trends in Pollution-Intensive Industries: A Review of Sectoral Trends; No 1997-06; UNU-INTECH Discussion Paper Series; United Nations University-INTECH, USE: Tokyo, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B.; Ren, B. Measurement and analysis of the high-quality development of China’s inter-provincial economy. Econ. Issues 2018, 4, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, A. Environmental regulation and manufacturers’ location choices: Evidence from the census of manufactures. J. Public Econ. 1996, 62, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiong, Y. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Quality of Regional Economic Development—Based on the Comparison of HDI Regions. Econ. Survey 2020, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. Environmental Regulation, Service Industry Development and the Industrial Structure Adjustment in China. Econ. Manag. 2013, 35, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Q.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J. The Impact of Environmental Regulation Tools on Environmental Quality from the Perspective of Industrial Structure. Econ. Survey 2018, 35, 94–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Chen, D. Haze pollution, government governance and high-quality economic development. Econ. Res. 2018, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

| Explained Variable | Level 1 Indicators | Level 2 Indicators | Unit | Indicator Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality development of regional economy (hqd) | Level of economic development (le) | Logarithm of GDP per capita (y1) | / | Positive index |

| Stability of economic development (st) | CPI (y2) | % | Reverse indicator | |

| Urban registered unemployment rate (y3) | % | Reverse indicator | ||

| Sustainability of economic development (su) | Green coverage rate of built-up area (y4) | % | Positive index | |

| Per capita public green area (y5) | % | Positive index | ||

| Pollution intensity (y6) | M2/person | Reverse indicator |

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Tianjin | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.44 |

| Hebei | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| Shanxi | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.49 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Liaoning | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.56 |

| Jilin | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.44 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.29 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| Shanghai | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.69 |

| Jiangsu | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 1.00 |

| Zhejiang | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Anhui | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.57 |

| Fujian | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.42 |

| Jiangxi | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.47 |

| Shandong | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.62 |

| Henan | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.53 |

| Hubei | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.53 |

| Hunan | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.46 |

| Guangdong | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 1.00 |

| Guangxi | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.58 |

| Hainan | 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 1.00 |

| Chongqing | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| Sichuan | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.53 |

| Guizhou | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.46 |

| Yunnan | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.44 |

| Shanxi | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| Gansu | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.41 |

| Qinghai | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| Ningxia | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.39 |

| Xinjiang | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.59 |

| Variables | Sample Size | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min. Value | Max. Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hqd | 360 | 0.3996 | 0.193 | 0.0759 | 1 |

| lner | 360 | 5.004 | 0.9609 | 1.808 | 7.258 |

| is | 360 | 0.4255 | 0.0916 | 0.286 | 0.806 |

| fa | 360 | 9.04 | 0.9555 | 5.966 | 10.919 |

| edu | 360 | 8.696 | 0.9039 | 6.6 | 11.6 |

| lnimex | 360 | 5.792 | 1.6135 | 1.504 | 9.458 |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable (hqd) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Cross Term Introduced | No Cross Term Introduced | Introduce Cross Terms | Introduce Cross Terms | |

| Provinces with Higher than the National Average HDI | Provinces with Lower than the National Average HDI | Provinces with Higher than the National Average HDI | Provinces with Lower than the National Average HDI | |

| lner | 0.0171 (0.89) | 0.0182 (0.39) | −0.1301 ** (−2.17) | −0.2125 ** (−2.56) |

| is | 1.112 *** (5.83) | 0.4583 *** (3.56) | −0.5109 (−0.88) | −2.393 * (−1.74) |

| fa | 0.328 ** (1.98) | −0.0413 (1.36) | 0.0594 ** (1.99) | 0.053 *** (2.68) |

| edu | 0.0267 (0.51) | −0.0345 (−0.77) | 0.0182 *** (3.33) | −0.0185 (−0.48) |

| lnimex | 0.0796 (1.32) | 0.0715 *** (4.16) | 0.0859 (1.37) | 0.0616 (0.8) |

| lner×is | - | - | 0.2798 *** (2.95) | 0.5647 ** (2.14) |

| Constant Term | −1.256 *** (−6.12) | −0.3697 (−1.03) | −0.622 ** (−2.21) | 0.6063 (0.87) |

| Sample Size | 108 | 252 | 108 | 252 |

| Province | 9 | 21 | 9 | 21 |

| Method | FE | FE | FE | FE |

| Adj R-sq | 0.8754 | 0.3501 | 0.8841 | 0.3671 |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable (hqd) | |

|---|---|---|

| No Cross-Term Introduced | Introduce Cross-Terms | |

| lner | 0.021 (0.72) | −0.1796 *** (−4.32) |

| is | 0.786 *** (5.57) | −1.594 ** (−2.52) |

| fa | 0.0164 (0.71) | 0.0546 *** (3.64) |

| edu | 0.0087 (0.26) | 0.0007 (0.02) |

| lnimex | 0.0738 *** (4.00) | 0.067 *** (3.98) |

| lner×is | - | 0.4356 *** (4.03) |

| Constant Term | −0.6911 *** (−2.74) | 0.1533 (0.4) |

| Sample Size | 360 | 360 |

| Province | 30 | 30 |

| Method | FE | FE |

| Independent Variables | Replace Dependent Variable (hqd) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Cross-Term Introduced | No Cross-Term Introduced | Introduce Cross-Terms | Introduce Cross-Terms | |

| Provinces with Higher than the National Average HDI | Provinces with Lower than the National Average HDI | Provinces with Higher than the National Average HDI | Provinces with Lower than the National Average HDI | |

| lner | −1.912 (−0.86) | 2.72.4 (0.22) | −2.3776 ** (−2.24) | −1.0116 ** (−2.24) |

| is | 8.5171 ** (3.30) | 2.2220 *** (2.67) | −1.55776 (−1.19) | −1.06194 ** (−1.97) |

| fa | 1.0911 ** (2.20) | 3.484 ** (2.00) | 1.4871 *** (3.77) | 4.008 *** (2.64) |

| edu | 6.565 (1.01) | −1.854 (−0.88) | 5.311 (0.98) | −1.133 (−0.54) |

| lnimex | 7.136 (1.05) | 5.953 *** (4.39) | 8.067 (1.60) | 5.510 *** (3.83) |

| lner×is | - | - | 4.1542 * (1.88) | 2.5427 ** (2.34) |

| Constant Term | −2.19494 *** (−4.47) | 1.3546 *** (−3.19) | −1.25338 ** (−2.42) | 7.88.1 (0.04) |

| Sample Size | 108 | 252 | 108 | 252 |

| Province | 9 | 21 | 9 | 21 |

| Method | FE | FE | FE | FE |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Ye, W.; Huo, C.; James, K. Environmental Regulations, the Industrial Structure, and High-Quality Regional Economic Development: Evidence from China. Land 2020, 9, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120517

Chen L, Ye W, Huo C, James K. Environmental Regulations, the Industrial Structure, and High-Quality Regional Economic Development: Evidence from China. Land. 2020; 9(12):517. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120517

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lingming, Wenzhong Ye, Congjia Huo, and Kieran James. 2020. "Environmental Regulations, the Industrial Structure, and High-Quality Regional Economic Development: Evidence from China" Land 9, no. 12: 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120517