Determining Indicators Related to Land Management Interventions to Measure Spatial Inequalities in an Urban (Re)Development Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Libertarians Do Not Consider Spatial Inequalities an Issue

2.2. Considering the Egalitarian Paradigm to Assess Socio-Spatial Inequalities

2.3. Evaluation of Spatial Justice Based on Egalitarian Paradigm

3. Research Methodology

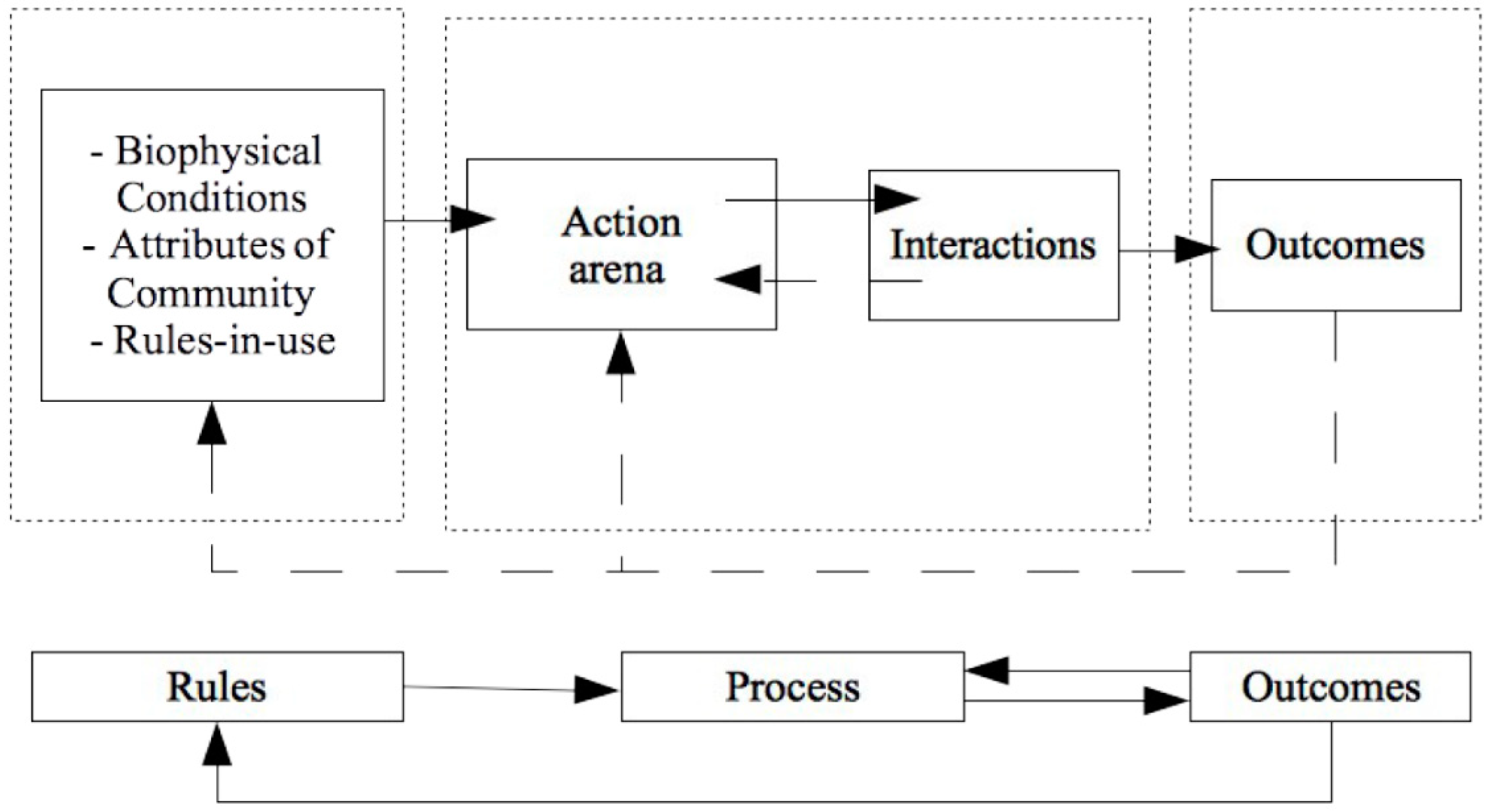

3.1. Approaching the IAD Framework by Three Dimensions: Rule, Process and Outcomes

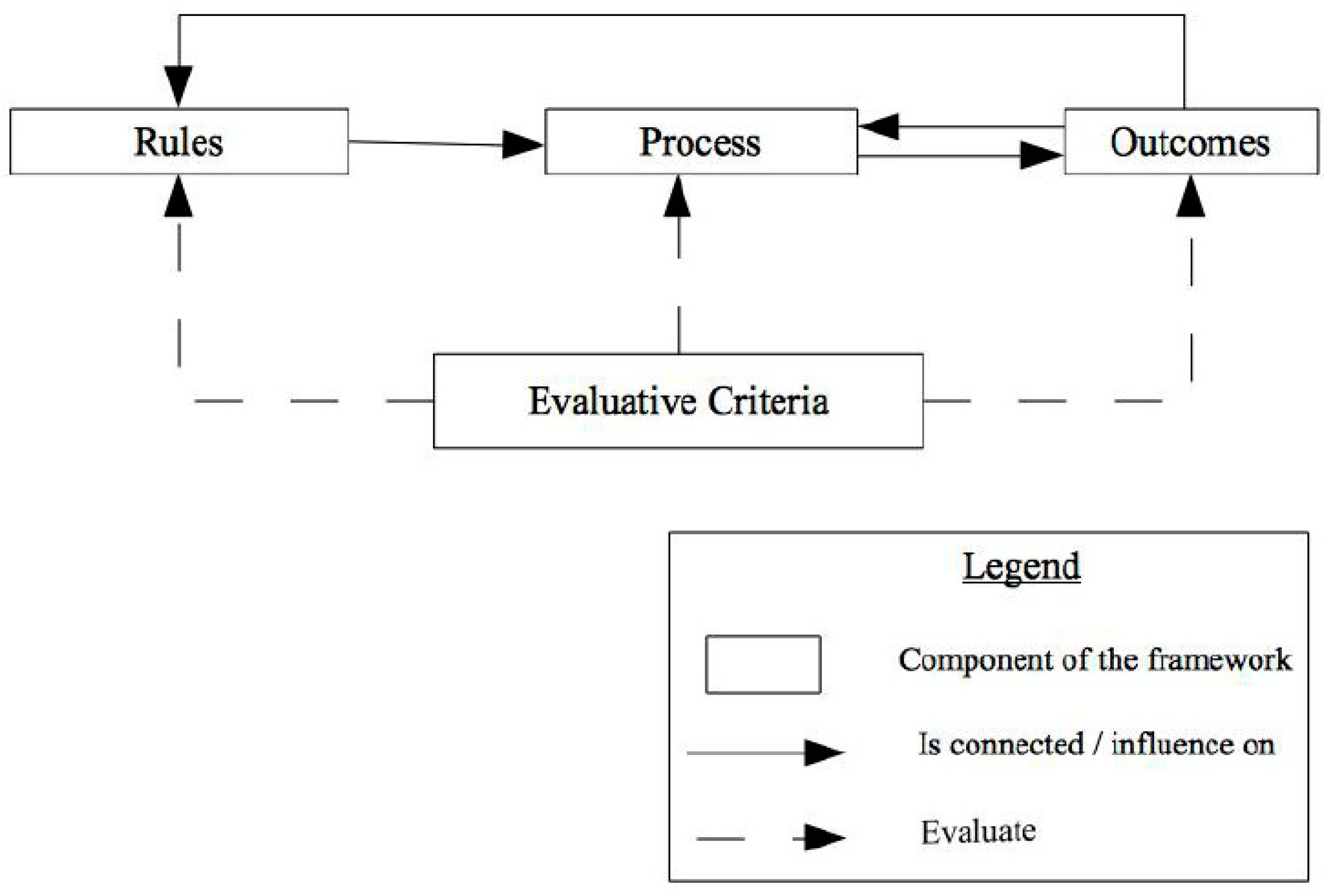

3.2. Defining an Institutional Framework for Spatial Justice

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Determining Indicators Related to the Use of Land

4.2. Determining Indicators Related to Access to Land

4.3. Determining Indicators Related to Redistribution of Land-Use

5. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aveline, N. Les Marchés Fonciers À L’épreuve De La Mondialisation, Nouveaux Enjeux Pour La Théorie Économique Et Pour Les Politiques Publiques. HDR Thesis, Université Lumière—Lyon II, Lyon, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boughaba, M. Social and Affordable Housing in the UK: Overcoming the Housing Shortage with Better-Quality Houses and Healthier Environments. Master’s Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, R.J. The Affordable Housing Shortage: Considering the Problem, Causes and Solutions; Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jargowsky, P.A. Sprawl, Concentration of Poverty, and Urban Inequality; Forthcoming in Gregory Squires: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Ortalo-Magne, F.; Prat, A. On the Political Economy of Urban Growth: Homeownership versus Affordability. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2014, 6, 154–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.H.D.; Tian, G. Urban Expansion, Sprawl and Inequality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goytia, C.; Dorna, G. What Is the Role of Urban Growth on Inequality, and Segregation? In The Case of Urban Argentina’s Urban Agglomerations; CAF development Bank of Latin America: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Renewable Resources and Conflict. In Toolkit and Guidance for Preventing and Managing Land and Natural Resources Conflict; UN-Habitat-New York: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. Spatial Justice and Planning. In Readings in Planning Theory; Fainstein, S.S., DeFilippis, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 258–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City; Cornell University Press: London, UK, 2010; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Le droit à la ville, 1st ed.; Anthropos: Paris, France, 1968; p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. Théorie de la justice, 1st ed.; Seuil: Paris, France, 1987; p. 666. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Land Tenure and Rural Development; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrath, S. La mise en Place du Régime Institutionnel de L’aménagement du Territoire en Suisse Entre 1960 et 1990. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, B. Planning, Law and Economics: An Investigation of the Rules We Make for Using Land, 1st ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Oxon, UK, 2006; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, C.; Ostrom, E. A Framework for Analyzing the Knowledge Commons. In Understanding Knowledge as a Commons; Hess, C., Ostrom, E., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 41–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Self-Governance and Forest Resources; Academic Foundation: Haryana, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1998, 92, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J.; Agrawal, A.; Blomquist, W.A.; Schlager, E. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; University of Michigan press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1993; p. 369. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M. Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2016, 39, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandburg, K.J.; Frischmann, B.M.; Madison, M.J. The Knowledge Commons Framework. In Governing Medical Knowledge Commons; Strandburg, K.J., Frischmann, B.M., Madison, M.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, C. Les impasses de la «ville néolibérale»: Entre «rééquilibrage territorial» et «rayonnement international», les paradoxes de deux grands projets de renouvellement urbain dans les agglomérations de Lille et de Hambourg. Métropoles 2018. Hors Série. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béal, V. Trendsetting cities: Les modèles à l’heure des politiques urbaines néolibérales. Métropolitiques. 2014. Available online: https://metropolitiques.eu/Trendsetting-cities-les-modeles-a-l-heure-des-politiques-urbaines-neoliberales.html (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Schaeffer, Y. Trois Essais sur les Relations Entre Disparités Socio-Spatiales et Inégalités Sociales. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Dijon, Dijon, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Viel, L. La légitimité des Parties Prenantes Dans L’aménagement des Villes: Éthique de la Conduite des Projets Urbains. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bihr, A.; Pfefferkorn, R.I. Le champ des inégalités. In Le système des inégalités, 1st ed.; Bihr, A., Pfefferkorn, R.I., Eds.; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Theodore, N. Cities and the Geographies of “Actually Existing Neoliberalism”. Antipode 2002, 34, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morange, M.; Fol, S. Ville, néolibéralisation et justice. Justice Spatiale|Spatial Justice 2014, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. Planning Theory and the City. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2005, 25, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, P. Whose Right(s) to What City? In Cities for People, Not for Profit Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City; Brenner, N., Marcuse, P., Mayer, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2012; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, C. Henri Lefebvre, the Right to the City, and the New Metropolitan Mainstream. In Cities for People, Not for Profit Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City; Brenner, N., Marcuse, P., Mayer, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2012; pp. 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 939–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Moulaert, F.; Rodriguez, A. Neoliberal Urbanization in Europe: Large–Scale Urban Development Projects and the New Urban Policy. Antipode 2002, 34, 542–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hamme, G.; Van Criekingen, M. Compétitivité économique et question sociale: Les illusions des politiques de développement à Bruxelles. Métropoles 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Recognition without Ethics? Theory Cult. Soc. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. Justice as Fairness: A Restatement; Harvard University Press: London, UK, 2001; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the politics of difference, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, C. Post–Democracy; Polity Press: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, M. Recapturing Democracy: Neoliberalization and the Struggle for Alternative Urban Futures; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. The Post-Political City. In Urban Politics Now. Re-Imagining Democracy in the Neoliberal City; Stavrakakis, Y., Boie, G., MacCannell, J.F., Matthias Pauwels, M., Eds.; BAVO: Rotterdam, NL, USA, 2007; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C. Representations of Space, Spatial Practices and Spaces of Representation: An Application of Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad. Cult. Organ. 2005, 11, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. Inclusion and Democracy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, C. Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism? Soc. Res. 1999, 66, 745–758. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, H.; Marshall, R. Towards justice in planning: A reappraisal. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning in Perspective. Plan. Theory 2003, 2, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Democracy and Expertise: Reorienting Policy Inquiry. In Democracy and Expertise; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 339. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, D. An IntroductIon to Indicators; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Assessing the Effects of ICT in Education: Indicators, Criteria and Benchmarks for International Comparisons; OECD—European Commission Joint Research Centre: Luxembourg, 2010; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Haie, N.; Keller, A.A. Macro, Meso, and Micro-Efficiencies in Water Resources Management: A New Framework Using Water Balance. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2012, 48, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Polillo, S. Power in Organizational Society: Macro, Meso and Micro. In Handbook of Contemporary Sociological Theory; Abrutyn, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Recognition or Redistribution? A Critical Reading of Iris Young’s Justice and the Politics of Difference. J. Political Philos. 1995, 3, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveson, K. Social or spatial justice? Marcuse and Soja on the right to the city. City 2011, 15, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. La Ville et la Justice Spatiale; Colloque, Université de Paris Ouest Nanterre: Paris, France, 2009; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Uwayezu, E.; de Vries, W.T. Indicators for Measuring Spatial Justice and Land Tenure Security for Poor and Low Income Urban Dwellers. Land 2018, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecroart, P.; Palisse, J.-P. Grands Projets Urbains En Europe: Quels Enseignements Pour l’Île-de-France. In Grands Projets Urbains En Europe: Conduire le changement dans les Métropoles; Huchon, J.P., Ed.; IAURIF: Paris, France, 2007; pp. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Charmes, E.; Bacqué, M.-H. Mixité Sociale, et Après? PUF: Paris, France, 2016; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, J.-M.D. Ingénierie Sociale Ou Art Des Mélanges? In Ville-École-Intégration Enjeux; CNDP: Paris, France, 2003; Number 135; pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- IAU-IdF. La Mixité Fonctionnelle au Regard du Commerce: Retour sur 4 Quartiers en Rénovation Urbaine; IAU Île-de-France: Paris, France, 2015; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- IAU-IdF. La Mixité Fonctionnelle Dans Les Quartiers En Rénovation Urbaine; IAU Île-de-France: Paris, France, 2009; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Walle, I.; Bouazza, H.; Dujin, A.; Robin, A. Etat, Collectivités Territoriales et Entreprises Face à La Mixité Fonctionnelle: L’exemple de l’agglomération Nantaise; IAU Île-De-France: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, Z.; McKee, K. Creating sustainable communities through tenure-mix: The responsibilisation of marginal homeowners in Scotland. GeoJournal 2012, 77, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontokosta, C.E. Mixed-Income Housing and Neighborhood Integration: Evidence from Inclusionary Zoning Programs. J. Urban Aff. 2014, 36, 716–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calavita, N.; Grimes, K. Inclusionary housing in California: The experience of two decades. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1998, 64, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calavita, N.; Grimes, K.; Mallach, A. Inclusionary zoning in California and New Jersey: A comparative analysis. Hous. Policy Debate 1997, 8, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, R.; Schuetz, J. What drives the diffusion of inclusionary zoning? J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2010, 29, 578–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, J.; Meltzer, R.; Been, V. Silver bullet or trojan horse: The effects of inclusionary zoning on local housing markets. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M. Developing, designing and managing mixed tenure estates: Implementing planning gain legislation in the Republic of Ireland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollens, S.A. Constituencies for limitation and regionalism: Approaches to growth management. Urban Aff. Q. 1990, 26, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, T.; Neiman, M. Community social status, suburban growth, and local government restrictions on residential development. Urban Aff. Q. 1992, 28, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlanfeldt, K.R. Exclusionary land-use regulations within suburban communities: A review of the evidence and policy prescriptions. UrbanStudies 2004, 41, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendall, R. Local land use regulation and the chain of exclusion. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.; Szilard, F.; Wehrmann, B. Towards Improved Land Governance; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.; Lowell, C. Land Taxation in Taiwan. In The Taxation of Urban Property in Less Developed Countries; Bahl, R.W., Ed.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1979; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Thierstein, A. Urban and Regional Dynamics; TUM: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, E.S.; Hamilton, B.W. Urban Economics, 1st ed.; Elsvier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989; p. 488. [Google Scholar]

- Smolka, M.O. Implementing Value Capture in Latin America: Policies and Tools for Urban Development; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan, S. Du processus de Métropolisation à celui de la Gentrification, L’exemple de Deux Villes Nord-méditerranéennes: Barcelone et Marseille. Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Aix Marseille, Aix Marseille, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baysse-Lainé, A. Terres Nourricières? La Gestion de l’accès Au Foncier Agricole En France Face Aux Demandes de Relocalisation Alimentaire: Enquêtes Dans l’Amiénois, Le Lyonnais et Le Sud-Est de l’Aveyron. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lyon, Lyon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Land Coalition. Tirana Declaration—Global; International Land Coalition: Tirana, Albania, 2011; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdin, A.; Lefeuvre, M.-P.; Melé, P. Les Règles du jeu Urbain: Entre droit et Confiance; Descartes & Cie: Paris, France, 2016; p. 316. [Google Scholar]

| Definition | Bibliographic References | |

|---|---|---|

| Rule | Rules provide all people with equal opportunities to access and/or use spatial resources. | [21,38,39] |

| Process | Consists of designing and implementing plans and activities that pertain to the management of space through active participation and collaboration among users of spatial resources, decision makers and planners. | [10,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] |

| Outcomes | The access to spatial resources, their uses, and their redistribution on the space. | [40,44,47] |

| Land Management Intervention | Indicator | Connection to Spatial Justice | Indicative References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule | Process | Outcomes | |||

| Use | Functional mix | Strategies and rules for improving functional mix;A zoning including different amenities | Insert the project in large scale and consider the needs in the neighbours; integration of revitalized areas and their inhabitants into the modern city | Promotion of good-quality facilities, services, and housing | [32,64,65,66,67] |

| Existence of public equipment and public services | Provision of basic services and infrastructure: public equipment and public services | ||||

| Social mix5 | Rules and strategies to improve and emphasise social mix | Inclusion into a zoning scheme of affordable units for poor and low-income groups | Promotion of access to houses for all people and elimination of inequalities in housing; integration of poor and low-income groups into the city | [10,62,63,68] | |

| Land Management Intervention | Indicator | Connection to Spatial Justice | Indicative References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule | Process | Outcomes | |||

| Access | Access to public amenities and public services | Rules promoting the access to the city | Participation of and collaboration with all categories of people in spatial planning; they permit the integration of their needs and rights into urban development programs | Promotion of access to land resources or other urban amenities for all people, including poor, vulnerable, and low-income groups | [10,11,33,34,35] |

| Housing | Inclusion into a zoning scheme of affordable units for poor and low-income groups | Integration of poor and low-income groups into the urban fabric | Promotion of access to houses for all people and elimination of inequalities in housing | [10,11,33,34] | |

| Land Management Intervention | Indicator | Connection to Spatial Justice | Indicative References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule | Process | Outcomes | |||

| Redistribution | Distribution of public amenities | Strategies and rules improving access to resources for a large number of users (residents and others) | Participation of and collaboration with all categories of people in spatial planning and adapt the redistribution of land use to their needs | Equitable redistribution of public amenities; promotion of access to good-quality facilities, services, and housing | [10,35] |

| Distribution of affordable housing | Rules and strategies to avoid segregation; inclusion into a zoning scheme of affordable units for poor and low-income groups | Equitable distribution of affordable housing; elimination of inequalities in housing | [67,68,82] | ||

| 1 | In fact, the relationship between social and spatial inequalities could be assessed in the definition of socio-spatial disparities [27]: the differences between geographic areas regarding the socio-economic characteristics of their inhabitants. |

| 2 | In the sense of non-equality, mainly in term of incomes. |

| 3 | “The extent to which the beneficiaries of a public good or service are expected to contribute towards its production” [22]. |

| 4 | It includes housing renewal, urban transformation, wastelands renewal, etc. Housing renewal consists of improving the physical, social, economic, and ecological aspects of old urban neighbourhoods. The process involves also the revitalisation of individual or community properties, including dwelling units. This gives the local community options to renovate their existing buildings or demolish them in order to develop new ones. |

| 5 | Or mix tenure, or inclusionary zoning, or mixed communities (McIntyre). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Achmani, Y.; Vries, W.T.d.; Serrano, J.; Bonnefond, M. Determining Indicators Related to Land Management Interventions to Measure Spatial Inequalities in an Urban (Re)Development Process. Land 2020, 9, 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110448

Achmani Y, Vries WTd, Serrano J, Bonnefond M. Determining Indicators Related to Land Management Interventions to Measure Spatial Inequalities in an Urban (Re)Development Process. Land. 2020; 9(11):448. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110448

Chicago/Turabian StyleAchmani, Youness, Walter T. de Vries, José Serrano, and Mathieu Bonnefond. 2020. "Determining Indicators Related to Land Management Interventions to Measure Spatial Inequalities in an Urban (Re)Development Process" Land 9, no. 11: 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110448

APA StyleAchmani, Y., Vries, W. T. d., Serrano, J., & Bonnefond, M. (2020). Determining Indicators Related to Land Management Interventions to Measure Spatial Inequalities in an Urban (Re)Development Process. Land, 9(11), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110448