1. Introduction

The Iñupiat of northwest Alaska have an intimate relationship with caribou going back millennia, as both a primary food and material resource, and as a feature of their collective identity. The 1980 Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) established National Parklands encompassing much of the range of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd (WACH). Kobuk Valley National Park (NP) and Cape Krusenstern National Monument (NM) are specifically directed at protecting the viability of subsistence resources and subsistence uses.

In carrying out ANILCA National Park Service (NPS), managers work alongside neighboring state and federal land management agencies, and rural subsistence users who depend on the parks. NPS managers for Kobuk Valley NP and Cape Krusenstern NM work in Kotzebue, located in northwest Alaska. The majority of subsistence users are of Iñupiaq heritage and rely on Indigenous Knowledge (IK) to steward resources for the next generation [

1,

2]. IK is the “cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment” [

3] (p. 1252). The use of the term Indigenous Knowledge recognizes that the Iñupiat have generations of knowledge related to the WACH, as well as adaptive relationship to the resource. The knowledge used to harvest and manage is evolving.

To integrate IK into the ANILCA framework of subsistence management, the Caribou Hunter Success Working Group (CHSWG) has formed to address specific concerns about the stewardship of caribou. This study will explore the IK shared through the CHSWG, as well as the challenges to and opportunities for mobilizing that knowledge in NPS management.

The WACH is the largest caribou herd in Alaska. The herd migrates across northwest Alaska, with a range estimated at 157,000 square miles, the route taken varying year to year. Generally, the fall migration takes them from Alaska’s North Slope southward through the Noatak, Kobuk, and Selawik river drainages, and along the coast of the Chukchi Sea. The range spans lands owned and managed by the State of Alaska, Native Corporations, and Federal Lands (Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, and NPS). With virtually no roads in the region, subsistence hunters’ best access to the fall season’s prime bull caribou is to intercept migration by boat along waterways near their communities. Roughly 40 villages harvest from the WACH for an estimated annual harvest of 10,000–15,000 caribou. This study focuses on two of those communities in the Northwest Arctic Borough: Kiana, on the Kobuk River, and Kotzebue, located on the coast of Kotzebue Sound [

4].

The size of the herd fluctuates following natural trends of abundance and decline. The past century included scarcity in the early 1900s, an increase in the 1930s–1950s, and another decline of the herd in 1975 when the population was estimated at the lowest on record, 75,000 caribou. The herd again increased until 2003, reaching a population of 490,000 caribou. Since 2003, the herd’s size has been reduced by half. The recent decline has charged regulatory discussion, as subsistence users and managers have heightened concerns about sustaining the herd [

4].

For the Iñupiat of northwest Alaska, caribou is a cultural keystone species [

5,

6,

7,

8]. That is, the WACH “play a unique role in shaping and characterizing the identity of the people who rely on them… that become embedded in a people’s cultural traditions and narratives, their ceremonies, dances, songs, and discourse” [

9] (p. 1). Traditionally, caribou were hunted through a community-wide effort to herd the caribou into locations that would make for easy harvest. This includes but is not limited to rivers, lakes, and constructed corrals and snares [

10]. The relationship to the herd was understood to be one of interdependence. The Iñupiat way of life, including seasonal settlement patterns, were determined by the caribou movements and hunter behavior could alter the migration of the herd. [

5].

In the modern management context, the caribou herd is the shared interest that brings both NPS staff and Iñupiaq subsistence hunters to the same table with other land management agencies. As the NPS aims to mobilize IK in subsistence management, they are working against the NPS legacy of erasing Indigenous people and use from the land [

11]. The erasure began with removal of Indigenous people from their homelands for the establishment of parks, as was the case for Yellowstone National Park, Yosemite National Park, and Grand Canyon National Park [

12]. For many tribes, the disruption of traditional use of plants, fish, and wildlife accompanied removal [

13].

In Alaska, ANILCA and the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) that preceded it in 1971, define almost all aspects of federal land management and federal relationships with native peoples. ANCSA was the settlement of land claims from the Alaskan natives, opening the gate for federal conservation units to be established through ANILCA. In ANCSA, legislators also promised to uphold Alaska Native subsistence land use on federal lands. In practice, ANILCA provides a subsistence priority for all rural residents, Alaska Natives among them, and establishes a framework for subsistence users to give input to federal managers on subsistence uses [

14,

15].

The enabling legislation for Cape Krusenstern NM and Kobuk Valley NP in ANILCA directs managers to “protect the viability of subsistence resources” as well as to work with Alaska Natives to preserve and interpret resources [

16] (Title II, Sec 201). Title VIII, setting the framework for subsistence management in national parks, establishes Subsistence Resource Commissions (SRCs) [

16] (Sec. 808). The commissions have a direct channel to the Secretary of the Interior and the Governor of Alaska, inform NPS management, and feed into the Federal Subsistence program. Also enabled by ANILCA, the Regional Advisory Councils (RACs) are formed of rural subsistence users and advise on subsistence management across federal lands [

16] (Sec. 805). In addition to the SRCs and RACs formed through ANILCA, NPS participates in the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group (WACHWG). Formed in 1997, this group evaluates herd status based on the most current herd demographics, then chooses a management level centered on population size, growth rate trend, and harvest rate. This management level comes with regulatory recommendations, and the management plan is used to inform regulatory proposal reviews [

4].

SRC and RAC meetings are typically held in Kotzebue twice a year. Subsistence users appointed to the commissions and councils who come from IK systems of knowing are motivated to volunteer by the desire to improve management through sharing their IK [

15]. They become skilled at working in two vastly different management systems and asserting IK, despite several obstacles presented by the SRC program. Because the meetings are held in Kotzebue, participation from outlying communities is not common, functionally limiting participation to the appointed representatives and removing the discussion of specific resources from the context of seasonal harvest. In a study that sought to understand the relationship between the Qikiqtaġruŋmiut, Kotzebue tribal members, and the NPS, the majority of respondents spoke of “restrictions in general” as a concern; and the number of tribal members who want to know more about regulations suggests the SRCs are falling short of broad public engagement [

17] (p. 30). The fact that the meeting follows a standard agenda and Roberts Rules of Order presents another barrier. These parameters can limit the conversation necessary to discuss the nuances of IK. In the end, the management integration of IK shared at these meetings is the responsibility of Park Service managers; however, vacant positions and staff turnover have made such integration difficult in the past and have caused frustration for Kotzebue tribal members [

17].

These SRC limitations affect the managers’ ability to understand and mobilize IK. Subsistence management is only as effective as the framework established by ANILCA allows it to be [

15]. In addressing effective management, this study builds on a 2003 report completed through a Cooperative Agreement with Cape Krusenstern NM and Kobuk Valley NP management titled “The Western Arctic Caribou Herd Barriers and Bridges to Cooperative Management” [

18]. In the report, co-management opportunities and levels of control were identified in different functions of management. The authors argued that co-management groups have proximate authority, meaning co-management groups are created by and bought into by the agencies, so there is a social expectation that they will be listened to [

18]. Risks involved in co-management, such as conflicting understandings among managers, can be mitigated by increasing the number of actors in the co-management network, such as by the formation of a working group [

19]. Mobilizing IK is identified as one of the central strategies and opportunities in the co-management of the WACH [

18]. The CHSWG, created by the SRCs and facilitated by NPS staff, has the potential to mitigate some of the risks involved with co-management by engaging more participants in management and increasing the understanding of IK for both managers and subsistence users for the more effective management of the WACH.

Effective management is the ability to respond to resource decline with measures that protect subsistence use and conserve the resource [

20]. The recent decline of the WACH has necessitated increased collaboration between the NPS, partner organizations, and subsistence users. In 2015 and 2016, biologists reported that hunting would soon impact the population if the decline continued. Regulatory boards and commissions responded with conservative regulation changes [

21]. At the same time, disagreement within subsistence hunting communities over the traditional stewardship of the herd climaxed.

The setting of this disagreement was the Kobuk River, as subsistence hunters, following traditional patterns of use, boated upriver to harvest fall caribou where their migration crosses reliably each year [

5]. One such reliable crossing, a small channel of the Kobuk River to the east of Kiana, attracts hunters from neighboring communities, including Kotzebue, the region’s population center. Because the fall caribou migration has taken place considerably later in recent years, subsistence hunters’ access to the prized bulls has become increasingly uncertain. Competition among subsistence hunters has increased. Issues with hunting on the Kobuk River have included overcrowding, the unsafe use of firearms, not sharing, non-traditional hunting practices, and waste [

22]. For the people of Kiana, the small channel of the Kobuk River that was the focal point of disagreements over use, has been identified by the Elders as their traditional hunting grounds. In 2015, the Kiana Elders Council addressed the hunter issues by putting out a list of guidelines based on traditions of their ancestors:

Always camp and hunt on the south side of the river;

When caribou start crossing the river, wait until they are half-way across, and approach from the north side to keep the migration moving south;

If you already have caribou, let the next boat in line have a chance;

Use smaller caliber rifles, for the safety of others;

Respect the cabins that you stop at and replace any source you borrowed, keep allotments clean;

Keep the land and the water clean of trash “we live on this land and drink from this river”.

They requested compliance from all hunters using the area [

22] but were presented with the challenge of communicating with hunters from the seven villages that harvest from the Kobuk River [

21].

At the fall 2016 meeting of the Kobuk Valley and Cape Krusenstern SRCs, members talked at length about hunting issues on the Kobuk River. Members agreed that hunter congestion in the river was putting others in danger and turning the herd back from their crossing. In discussion, members first suggested regulatory change to address the issues. However, SRC member and Kiana Elder Larry Westlake explained the IK behind hunting on the river: “that’s our traditional way of hunting ever since they start crossing, and we learned it from our Elders. It worked out for everybody, everybody got what they wanted. It’s common sense, you can’t get in front of a herd and chase it back and get your catch. You have to continue the migration. You can get your catch and the migration continues” [

21]. The Commission dropped the regulatory proposal in favor of an educational initiative and formed the CHSWG to support the Kiana Elders Council efforts.

The CHSWG formed in order for subsistence hunters to work with managers to utilize and develop educational materials based on IK. The IK-based conflict speaks to the complexity of managing subsistence use. The issue is not just maintaining the herd population needed for harvest, it is also about equitable access to the resource, the traditional and cultural practices surrounding harvest, and preserving the way of life for future generations. This study analyzed the records from the CHSWG to determine the effectiveness of identifying IK and opportunities to mobilize the knowledge. The outcome of this model has implications for co-management. With the recent decline of the WACH, the NPS is motivated to gain a better understanding of the use of resources and to integrate formal regulations and Indigenous Knowledge, for a greater likelihood of adherence. In the analysis we will look for new IK presented through the working group and for an increase in the number of people engaged in the management system as indicators of IK being mobilized. By deepening understanding of subsistence and engaging more users in the subsistence management systems, the mobilization of IK leads to more effective management.

2. Materials and Methods

The current effort to document caribou hunting IK began with the CHSWG meetings. The CHSWG formed to address “Hunter Success” issues from an IK perspective, with a focus on public outreach. “Hunter Success” comes from the “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat”, a program created by northwest Arctic leaders and Elders to define the values of the Iñupiat. Hunter Success is one of seventeen values aimed at passing on knowledge to the next generation. The definition of “Hunter Success” is getting meat for your family. It is tied to traditions and knowledge passed down from Elders [

23]. When addressing the subsistence hunting issues on the Kobuk River, the Kiana Elders Council chose to frame their IK as Hunter Success [

22].

At the direction of the SRCs, NPS staff facilitated the group made up of federal and state managers, along with subsistence users. Participants are self-selecting and because of the informal nature of the group, attendance varies. The contact list notified of CHSWG meetings is comprised of 24 participants. Of the 24, seven participants are Elders or hunters with IK about caribou hunting. Because these participants have or are currently serving on the SRCs, they can be described as key informants with established relationships of information sharing. The agencies, along with the NPS, involved in the working group include: the State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the Alaska State Wildlife Trooper, Selawik Fish and Wildlife Refuge, NANA Regional Corporation (the ANCSA Native Corporation for northwest Alaska), The Native Village of Kotzebue (Kotzebue’s tribal organization), northwest Arctic Borough, Maniilaq Association (the Native non-profit for the northwest Arctic), and Teck Alaska (a mining and development corporation). The agencies involved are also self-selecting. Participants include biologists, educators, and managers—all with interest in the management of the hunt from the WACH. Since 2017, seventeen working group meetings have been held. The meetings served as “analytical workshops”. Huntington described the benefit of this approach: “a workshop that brings together scientists and the holders of TEK can allow both groups to better understand the other’s perspective, and to offer fresh insights. By cooperating in the analysis of data, the two groups may also find common understanding and jointly develop priorities” [

24] (p. 1271).

The CHSWG was designed to be informal by not making decisions and providing a space to discuss IK and public outreach efforts. Each meeting is held at the NPS office and through teleconference. Rather than setting a formal agenda, the facilitator moves through discussion items, and the group is consensus-driven, with hunters and Elders holding the authority on IK, the main topic of discussion. Elders and hunters often ask managers for information on state and federal regulations and the WACH status. Outcomes of the working group are reported to the RACs and the SRCs at their biannual meetings.

The primary goal of the CHSWG is to support the transmission of IK. While the subsistence hunters in the group were primarily motivated by lax adherence to traditional hunting values, they also acknowledged a lack of awareness of current hunting regulations and the health of the herd, as this information changes from year to year. To increase communication in the villages, tribes hosted interagency informational meetings in the villages prior to the fall caribou hunting season. Since 2017, fifteen meetings were hosted in seven villages [

22]. The community hunter success meetings were “analytical workshops” considering localized IK; for example, the discussion in Kiana was focused on IK specific to the small channel of the Kobuk River, their traditional hunting grounds.

Community meetings were designed with several considerations for the cultural context of IK transmission. Firstly, meetings are held in the village right before the hunting season. This encourages the sharing of location-specific knowledge during the time of year when it is most relevant. The meetings are hosted in partnership with the local tribal government and are organized with local recommendations for a successful meeting. For example, a prayer is said at the beginning of the meeting if that is customary in the community. Secondly, participation in the community meetings is self-selecting. A raffle for all attendees may be offered as an incentive. Thirdly, as with the CHSWG meetings, Hunter Success community meetings are driven by consensus and Elders hold the authority on IK. Finally, agencies provide information in a question and answer style discussion. Village hunters who do not regularly meet with agency staff take the opportunity to ask questions about regulations that they do not understand.

For this study, the meeting records for subsistence meetings during the period 2016–2019 were analyzed using qualitative methods to determine if the CHSWG has created opportunities to mobilize IK. SRC and RAC meetings are recorded and transcribed. Working group meetings and community meetings are documented in a summary of discussion generated by the NPS. The records from the meetings were analyzed by the author to identify the “rules of thumb” in use for Iñupiaq caribou stewardship. The term “rules of thumb” is defined as “simple prescriptions based on a historical and cultural understanding of the environment”. They are often backed up by religious belief, ritual, taboos, and social conventions [

25] (p. 194). Rules of thumb can be expressed in a sentence, though the historical and cultural understanding of the environment make up a deep body of knowledge that the short form is meant to reference. In some settings, IK is transmitted in long form, for example, through an elder telling a story. Short-form rules of thumb are often engaged in co-management settings [

26].

Literature on IK has identified an issue with the way that it is mobilized in management in that IK is only partially understood by managers and removed from its context [

25]. IK is multifaceted, but the most commonly utilized part of IK is factual observations about the environment [

27]. The CHSWG aims to share IK in a holistic sense. The success can be measured, in part, by the analysis of materials for new facets of IK identified. Mobilizing IK in the existing structure of management will only serve to remove it from its context, however, mobilizing IK can affect management if it is integrated in a system that engages Indigenous people. One measure of integration is the number of people involved in the management structure. This method acknowledges IK as dynamic and responding to social context, rather than a static data source removed from the system of Indigenous management that it is derived from [

28].

3. Results

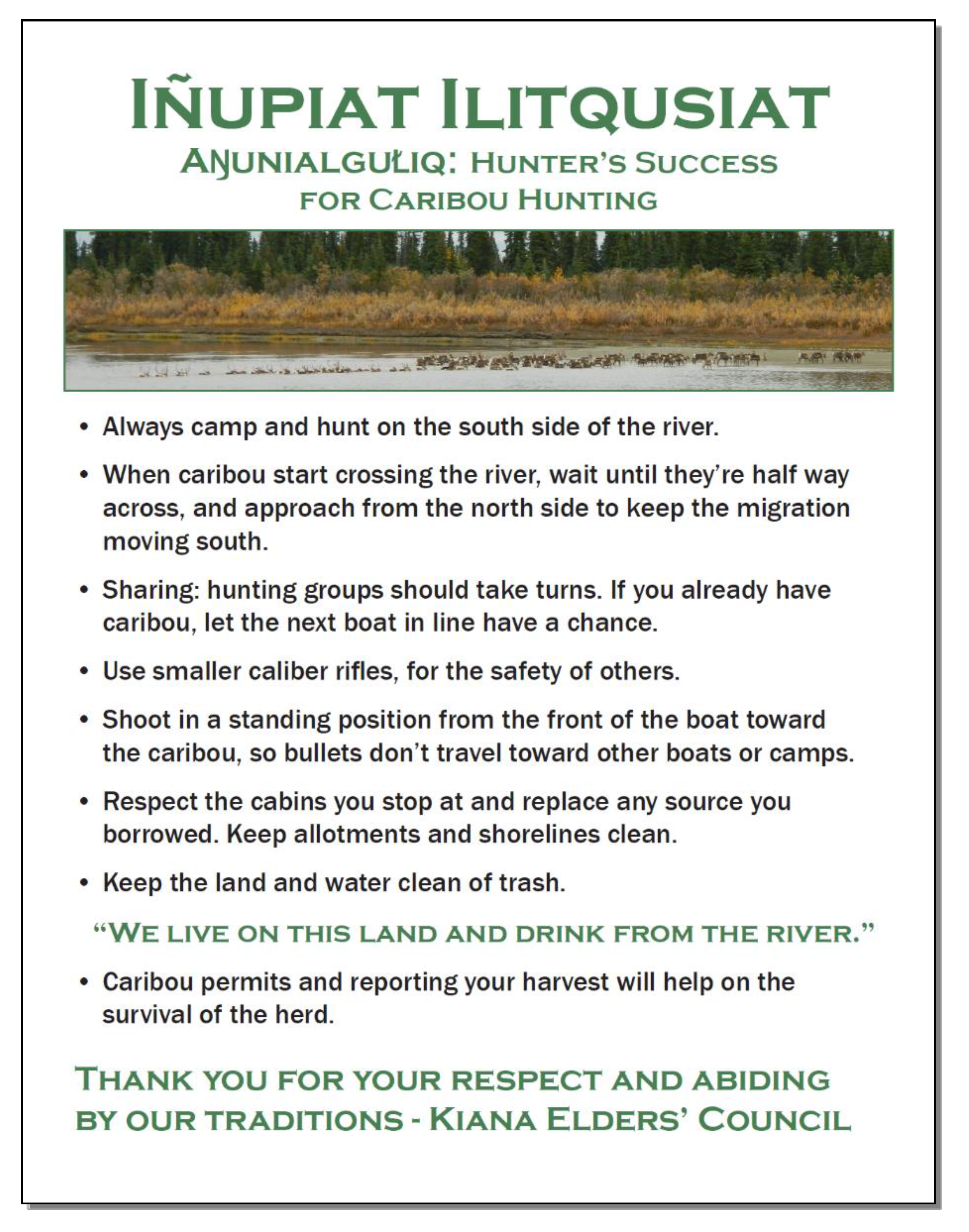

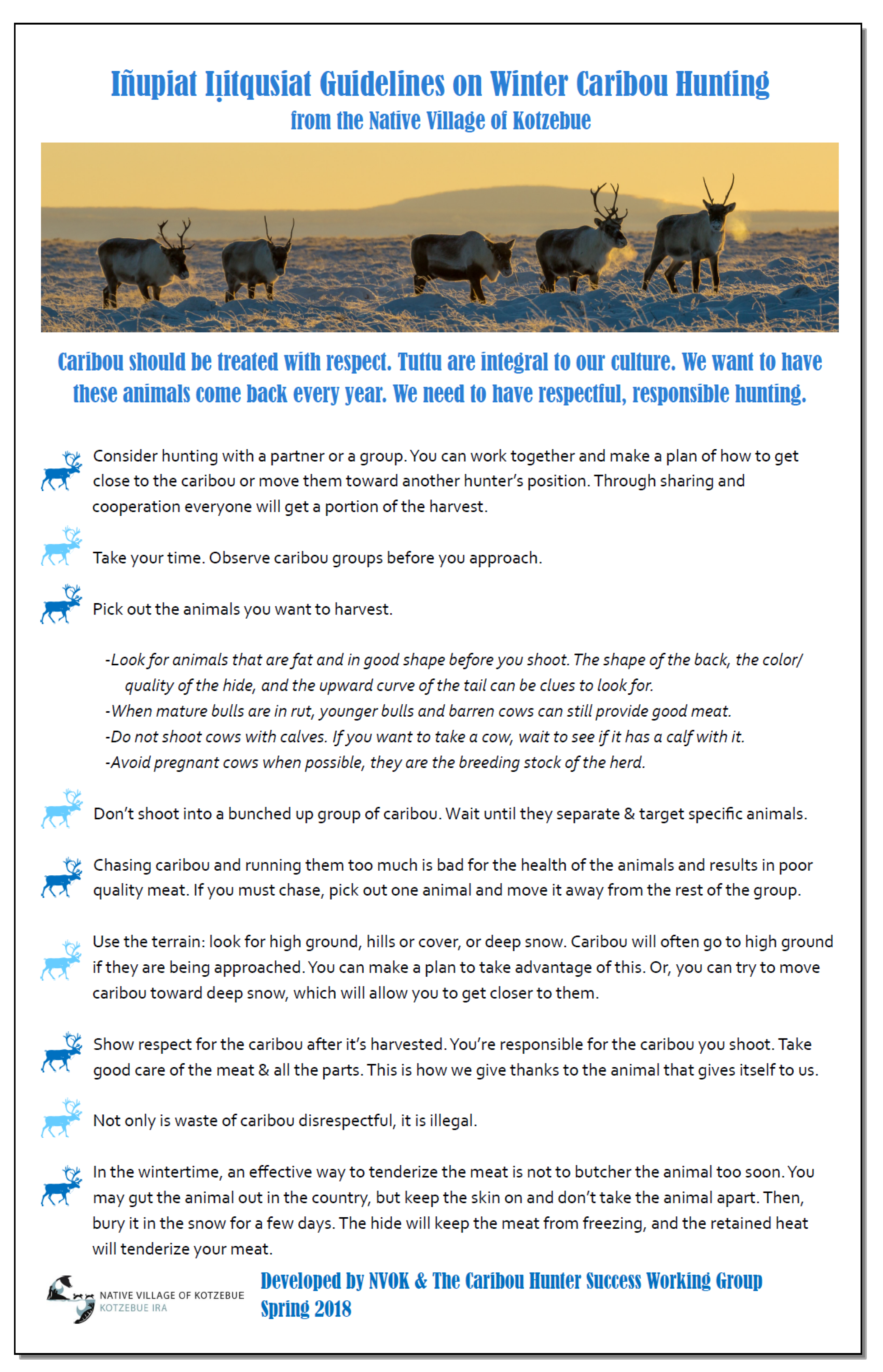

The CHSWG identified IK related to hunting issues brought up by Elders and hunters. The outcome of the CHSWG and the community meetings was the identification of IK rules of thumb. In two cases, the identification of IK happened through discussion at community meetings, semi-formal interviewing, and educational publications in the form of flyers, radio announcements, and social media campaigns. In each case, the CHSWG relied on publications that attempted to transmit IK in the form of rules of thumb. “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat Aŋunialgułik: Hunter Success for Caribou Hunting” (

Figure 1) was developed by the Kiana Elders Council and “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat Guidelines on Winter Caribou Hunting” (

Figure 2) was developed by the Native Village of Kotzebue with assistance from the CHSWG.

The CHSWG resulted in further definition of the Hunter Success issues on the Kobuk River. Larry Westlake, participating in the CHSWG to follow up on his work on the Kiana Elders Council and SRC, explained his motivation for educating his community:

“It is close to 60 years since caribou crossed near Kiana. When caribou came through the narrows, hunters in Kiana would wait two days after the caribou started crossing. After the first had crossed and established the migration, the Elders say, we would have caribou all our lifetime. Now-a-days there are more hunters and less caribou, all in a six-mile area on the Kobuk River. There are too many hunters. That’s why we brought Hunter Success back. They are not regulations but guidelines for a more successful hunt, for example, keep heads and horns out of the river side. Take care of the river”

In order to address the issues with hunting on the Kobuk River, community meetings were held in the villages that hunt from the Kobuk River. The first part of the community meetings was dedicated to discussing traditional Iñupiaq values around hunting. “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat Aŋunialgułik: Hunter Success for Caribou Hunting” (

Figure 1) was shared and used to start a discussion of differences and similarities between the values in neighboring communities. Then, agency staff provided information about the health of the herd and the changes in hunting regulations for the year. The information was presented in a two-way conversation with attendees; and throughout the communities, residents were consistent in questions about land ownership, jurisdiction, and enforcement [

22].

Table 1 shows the number of community meetings held during the period 2017–2019 and the attendance at the meetings relative to the population of the community. The attendance of community meetings shows the increase in the number of subsistence hunters participating in the co-management of the herd. This is in contrast to the representatives from those communities that serve on the SRCs, RACs, or WACHWG. There are four representatives from Kiana that serve on either the SRCs, RACs, or WACHWG, so it can be concluded that holding a meeting in Kiana increases the number of Kiana participants in the co-management of the WACH.

3.1. Caribou Hunting on the Kobuk River

In the case of the Kobuk River Hunter Success issues, community meetings provided space for IK rules of thumb to be further defined to address the issues identified. The community had defined the IK rules of thumb in their 2015 flyer “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat: Hunter Success for Caribou Hunting”. In 2017, the Kiana Elders Council along with the CHSWG revisited their 2015 document, and edits were made to the flyer to include a recent change in enforcement of caribou registration permits (

Figure 1). Following hunting regulations and Iñupiaq values were both considered a part of a successful hunt [

22]. In 2018 and 2019, the Kiana Hunter Success meeting started with the rules of thumb expressed in short form, then with Elders and hunters explaining the experience of hunting informed by IK, thus rules of thumb were thereby reshaped [

22].

This process included forming a committee of Kiana residents to shape the rules of thumb and to transmit the rules to their community [

22]. The Kiana committee worked to put together a call to hunters to wait twenty-four hours after the first migration of the herd before hunting, and to avoid the little channel of the Kobuk River. This guidance was based on the IK shared by the Kiana Elder Larry Westlake concerning how the caribou hunt was managed by his ancestors. The twenty-four hours after migration timeline falls under protecting the lead caribou rules of thumb. The request to avoid the little channel was directly tied to positioning of the hunter rules of thumb. The Hunter Success meeting gave space for the deep IK context of these rules of thumb to be explained, and for multiple Elders to explain their experiences with it. The flyer communicated IK in short form. Some members of the Kiana committee also hope to codify the rules of thumb in state hunting regulations [

22].

Before the hunting season, agency partners in the CHSWG shared the IK-based guidance created by the Kiana Committee. In the working group meetings that followed, Kiana community members reported less boats on the river, though effectiveness of their efforts was difficult to measure as the migration of the caribou did not include the crossing near Kiana in 2018. Boats were not there because the caribou were not there [

22].

3.2. Caribou Hunting by Snowmachine

The next case we will discuss was brought to the CHSWG after formation and the Kobuk River case served as a model to address the issue through the identification of IK. To give some background, we will first start by saying the migration pattern of the WACH is highly variable. However, a relatively new pattern of movement brings the herd along the coast of the Chukchi Sea and across Kotzebue Sound in November, after ice has formed, to surround Kotzebue while snow is on the ground [

29]. Subsistence hunters from Kotzebue and nearby areas hunt these migrating caribou from snowmachines. This method, combined with the herd’s proximity to the large community of Kotzebue, provides greater access than fall hunting by boat in the rivers. As Cyrus Harris, an Iñupiaq subsistence hunter from Kotzebue, Alaska, explained during a Working Group meeting: “The migration around Kotzebue after freeze-up is, for some people, their first time seeing caribou. People likely have the tools to harvest a caribou for the first time. All you need is a snowmachine and a gun. It is an educational wake-up call” [

22].

The needed education included more detailed IK rules of thumb on how and when to hunt caribou by snowmachine. The issue involved both formal regulation and the IK management system enforced by community standards [

22]. Snowmachines allow hunters to position themselves and the animals, herding caribou so they are easier to harvest. Snowmachines have been utilized since the mid-1960s when they replaced dog teams as the main form of winter transportation. In general, the use of the machines for hunting developed out of traditional methods of intercept hunting [

5]. On NPS and other federal lands in northwest Alaska, federal subsistence regulations set the parameters for hunters, such that: “a snowmachine may be used to position a hunter to select individual caribou for harvest provided that the animals are not shot from a moving snowmachine”. Under general statewide “Subsistence Restrictions” on federal lands, hunters are prohibited from using snowmachines to “drive, herd, or molest” caribou [

30] (p. 16–20).

Subsistence users maintain that the appropriate use of snowmachines to hunt and harvest can be negotiated through IK management systems. IK management systems allow hunters the most agency to apply IK to specific hunt situations [

26,

31]. The CHSWG, using the Kobuk River case as a model, set out to work with the Native Village of Kotzebue to identify IK rules of thumb in this case [

22]. The rules of thumb identified were approved by the Tribal Council and published in a document titled “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat Guidelines on Winter Caribou Hunting” (

Figure 2). However, in this case, it was determined by the CHSWG that community meetings would not be effective, given the low turn out of one community meeting held in Kotzebue (

Table 1).

Agency staff from the CHSWG used semi-formal interviewing to guide the discussion of IK. Questions were informed by the rules of thumb that surfaced each time the working group discussed traditional caribou harvest, including: protection of the lead caribou, rules positioning the hunter, rules for selecting and positioning the animal, salvage practices to use all parts of an animal, knowing the land/respecting the land, sharing, hunter safety, and following regulations [

22].

The resulting conversation covered knowledge passed down over generations focusing on the rules of thumb for hunter positioning and the positioning of animals. The following quote from Robert Schaeffer, an Iñupiaq hunter from Kotzebue, provides an example of a story used to transmit IK in long form.

“I remember when I first came back from school dad took us out and we needed to get a couple [of caribou], that we needed really bad, so we went over to the Noatak Flats toward the Hatchery area. It was colder than hell that day…and anyway we got there, we saw the herd down there, and he didn’t want to chase because he was more concerned about the health of the animals, he don’t want to chase in the cold because it will freeze their lungs and will affect them. So he said ‘what we’ll do is, I’ll sit up here, and you’ll go down and around them to the river. And you’ll come up at them slowly, and almost come to the top side. I’ll just wait here…all we need is four.’ And, sure enough, they headed to the top side. He picked out his four, got his four…Working together is really important. I think when we went out there with our younger folks afterwards, and ran into a caribou herd, we’d plan out what we are going to do before we even take off. We don’t just go out and go dashing into the herd, hoping like heck we can get something. Planning something like that is really important”

In the conversation surrounding this story, the hunters discussed landscape features that help in a hunt, such as the tendency of animals to run to high ground when they are threatened and the use of deep snow to slow a fleeing animal. Elders’ stories were transmitted through short-form assertions meant to be easily remembered, though they referenced a larger system of knowledge surrounding the assertions [

26].

The short form that was included in the hunter flyer reads, “Use the terrain: look for high ground, hills or cover, or deep snow. Caribou will often go to high ground if they are being approached. You can make a plan or take advantage of this. Or you can try to move caribou toward deep snow, which will allow you to get closer to them” (

Figure 2). The risk of sharing this information without the original conversation involves removing short-form information from a context of generational knowledge. Other methods of sharing information were suggested, such as school programs and hunter mentorships [

22]. While this was discussed at the working group, it would require the expansion of the program, including funding and possibly more staff.

It is challenging to measure the success of this educational initiative. Because community meetings were not used to spread the information, we do not have attendance numbers to gauge participation. The flyer was shared at the Native Village of Kotzebue Annual Meeting as well as at the 2018 RAC meeting. In early winter 2018, after a full year of circulating the “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat Guidelines on Winter Caribou Hunting” flyer (

Figure 2), parts of the caribou herd again migrated in November through the ice-covered Kotzebue Sound, bringing caribou right through town. Two young hunters killed a caribou by hitting it with their snowmachine. The Iñupiaq community was outraged at the lack of respect for nature [

33]. While the information shared by the CHSWG had not prevented the incident, the working group provided a space for hunters to communicate with the Alaska Wildlife Trooper on how the case was being handled, to discuss the disconnect between the traditional ways of hunting and the youth, and to recommend educational and service-oriented sentencing when the case went to court [

22].

4. Discussion

For managers of Kobuk Valley NP and Cape Krusenstern NM, mobilizing IK is the next step towards cooperative management. Subsistence hunters participating in formal subsistence management groups bring their IK perspective into NPS management, and the CHSWG has succeeded in creating opportunities to mobilize IK. In both Kiana and Kotzebue, IK rules of thumb were identified in order to address hunter success issues. In this work, there is the opportunity to make NPS management more effective through a deeper understanding of caribou harvest and by integrating IK into regulation, legitimizing NPS management [

18]. We can learn about similar challenges and inform our recommendations by looking at two studies on IK mobilized in the management of the Porcupine Caribou Herd on Alaska’s northern border with Canada [

26,

34]. Wray analyzed the Porcupine Caribou Management Board (PCMB) educational materials for rules of thumb and compared them to government regulations for caribou hunting [

26]. The PCMB also worked with government officials to establish formal regulations to protect the lead caribou migrating around the Dempster Highway in Canada’s Yukon and northwest territories [

34]. Finally, our discussion includes limitations of the current efforts to document IK through the CHSWG and recommendations for expanding the program.

The community meetings held by the Working Group in villages prior to the hunting season are an educational effort where IK rules of thumb are identified alongside Federal and State regulation. Spaeder et al. called the educational programs “the primary strategy in which resource agencies attempt to address resource conflicts and the gulf that exists between law and customary practice” [

18] (p. 88). At the 2018 Hunter Success Meeting in Kiana, community members discussed who has the power to make change in local hunting practices: the tribe, the federal government, or community members [

22]. This discussion of who holds the power of change is integral in landscapes split by jurisdiction and layered with multiple management systems. The hunter’s experience is shaped by the regulatory system as well as the management systems associated with the IK of the local people. Some Kiana community members called for change in the state regulations to reflect rules of thumb around the protection of the lead caribou [

22].

Kiana community members, over the course of three years of Hunter Success Community meetings, were able to identify and refine IK rules of thumb to address issues in the river channel east of town. Each meeting ended in consensus, but the consensus did not extend to the community members not in attendance [

22]. The study of the PCMB in Canada is helpful in the discussion of the challenges associated with reaching consensus on IK rules of thumb. Padilla and Kofinas found that “intercommunity conflict and intergenerational divide” in first nations groups created resistance to the formal regulations enforced by the Canadian government that were based on IK rules of thumb. The meaning of the “lead caribou”, when defined by the Indigenous Elders, is “highly context-dependent” [

34] (p. 212). The regulations to protect the lead caribou focused on closing portions of the road for weeks at a time. This method took the agency away from individual hunters to exercise IK as it fit the situation [

34]. In the case of the “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat Aŋunialgułik: Hunter Success for Caribou Hunting” (

Figure 1), consensus over IK rules of thumb is challenged by intercommunity conflict. The Kiana Elders Council wants to have hunters across the region comply with their values, but there is some variation in the IK shared in different traditional groups. In Noorvik, the community closest to Kiana, the IK was affirmed by a local Elder at a 2017 Hunter Success Meeting as he told stories based on his own experience of hunting on the Kobuk River. However, in Kotzebue, further from the hunting grounds where this IK was developed, hunters may be less educated in IK specific to the Kobuk River [

22].

In the case of caribou hunting by snowmachine near Kotzebue, there are similar aspects of intergenerational divide and the agency granted to the hunter to apply the guidance to specific hunting situations. When rules of thumb are shared through stories, such as the hunting story shared by the Iñupiaq hunter from Kotzebue, Robert Schaeffer [

32], the application of the rule of thumb to the specific hunting situation is communicated in ways hunters can learn and model. In Wray’s observation of the PCMB, shorthand versions of rules that are also communicated through stories and shared experiences serve an important function. “The use of such shorthand may be the only means of ensuring compliance with particular norms without the necessity of communicating all meaning in all instances” [

26] (p. 177).

However, sharing rules in shorthand assumes young hunters have the deeper understandings it is supposed to recall [

26]. In the Padilla and Kofinas case study, the interviewees expressed concern about youth in their community understanding traditional knowledge [

34]. In the case of caribou hunting by snowmachine around Kotzebue, the effectiveness of the educational efforts is limited by the youth’s lack of knowledge about the use of landscape, caribou physiology, and herding techniques. Because of gaps in the experiential learning required to be a successful hunter, all of the knowledge needed to have a successful hunt is not being communicated well through the short-hand IK rules of thumb that can be shared through a flyer.

Efforts to address subsistence issues surrounding Kotzebue winter caribou hunting will likely require a combination of hunting regulation enforcement and education through IK. In the development of the “Iñupiat Ilitqusiat Guidelines on Winter Caribou Hunting from the Native Village of Kotzebue” (

Figure 2), hunters were encouraged to develop IK rules of thumb to respond to the evolving hunting issue. Rules of thumb have the potential to hold hunters to values and ethics that will sustain the herd, while also allowing agency to the hunter [

26]. Some subsistence users have asked for agencies to enforce IK rules of thumb, and at times have gone through the regulatory process to codify the unwritten law of the land [

18]. The outcome for the PCMB is a caution that without consensus, the NPS enforcement of IK may be perceived as further infringement on the individual hunter’s subsistence rights and as a result, could delegitimize both systems of management [

34]. In the informal discussion around IK rules of thumb, the Kotzebue hunters flowed between regulatory changes and IK allowing all of the management tools to be explored—the alignment between hunter actions and IK ethics and values being the ultimate goal.

The CHSWG is expanding on the framework laid out in ANILCA. This follows recommendations, from Spaeder et al., to establish space for NPS and subsistence users to discuss issues outside the formal management structure and to facilitate collaborative efforts to solve issues [

18]. Looking at the way the conversation about Kobuk River hunting developed, we can see that when it was brought up at the 2016 SRC meetings, managers and subsistence users were unable to fully understand and address the issue. By forming this working group with a special focus on IK, federal and state managers and subsistence users worked together to identify IK rules of thumb. Participating in the working group meetings and community meetings as “Analytical Workshops” [

24] (p. 1271), the NPS has gained a deeper understanding of what is meant by “the lead caribou” and traditional methods of harvesting caribou by snowmachine [

22]. This knowledge can be mobilized in NPS interactions with subsistence users such as community meetings, subsistence commissions, and enforcement interactions. The informal setting allows Elders and hunters to discuss the intergenerational and intercommunity disconnect, and the agency staff are able to ask questions and generate solutions.

In the discussion of whether this working group approach leads to the effective management of the WACH, it is important to note that the impact on the WACH population and harvest numbers is outside of the scope of this study. Future research directions may include the impact of co-management initiatives on the WACH population and would need to be monitored over the course of decades. While a qualitative analysis of materials from the CHSWG shows that new information was gained, it is difficult to measure the reach of the educational materials used by the working group. Participation at the community meetings hosted by the working group give us some idea of the expansion of the co-management network, but it does not capture the reach of the message and does not directly correlate to the success of the educational effort. Because of the interpretive aspect of IK, it is also hard to measure success in terms of compliance. In both cases, the local conflicts around subsistence hunting continue. It is not the role of the NPS to fix this conflict, but it is clear that the NPS has an important role in management and that management of the herd should involve IK. This study shows that the collaborative relationships between the NPS and local entities is a step towards effective management.

Limitations to the organization and the reach of the CHSWG do exist. Because the aim is to bring subsistence users and agencies together to work informally, participants have loose obligations to attend. The working group reports back to the Kobuk Valley and Cape Krusenstern SRC; the decision-making power is with the NPS and other land management agencies. With an educational focus, the CHSWG operates within these limitations. Expansion of the efforts of the working group would require commitment from the NPS or other resource management agencies [

22].

This study has used three years of data gained through participation and observation. Further analysis could result in a better understanding of where IK originates and the outcomes of sharing that IK. Regardless of the limitations of the working group and research, this should be looked at as part of a broader management effort. The NPS is working to recognize, document, and mobilize IK through multiple efforts. IK is shared with the NPS at SRC meetings and through tribal consultation. Baseline documentation such as Traditional Use Studies are in progress in Noatak National Preserve and Kobuk Valley National Park [

7,

8]; and IK is integrated into Natural Resource and Cultural Resource projects.

The NPS managers for Cape Krusenstern NM and Kobuk Valley NP can further efforts to mobilize IK following several recommendations that come from our analysis of the CHSWG. First, intercommunity dialogue should be supported. As is customary in IK management systems, decision making is driven by consensus. It may take multiple conversations across different communities to reach a consensus. However, to mobilize IK based on just one source could result in the defiance of the guidelines and/or regulations by the hunters excluded from that by an incomplete consensus [

34]. Efforts to bolster IK must focus on long-term discussion, as IK is constantly forming and adapting to new situations. Rules of thumb should not be shared in short form without access to the deeper context [

26]. Mentorship programs have been suggested as a solution [

32]. Elders hold the authority on IK, and agency staff must be cautious to maintain that dynamic. IK-informed regulations enforced by government agencies threaten to delegitimize both the agency and IK. Lastly, the formation of a working group to focus on specific topics has proven to be a successful informal environment in which to discuss IK.