Unraveling Causes and Consequences of International Retirement Migration to Coastal and Rural Areas in Mediterranean Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Residential Mobility at Older Ages in Mediterranean Europe: A Brief Overview

3. Rural Landscapes and Economic Implications of IRM

4. Discussing the Spatial Implications of Residential Mobility at Older Ages

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bell, M. How often do australians move? Alternative measures of population mobility. J. Aust. Popul. Assoc. 1996, 13, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.; Barlow, J.; Leal, J.; Maloutas, T.; Padovani, L. Housing in Southern Europe; Blackwell: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandri, G.; Janoschka, M. Who Loses and Who Wins in a Housing Crisis? Lessons from Spain and Greece for a Nuanced Understanding of Dispossession. Hous. Policy Debate 2017, 28, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

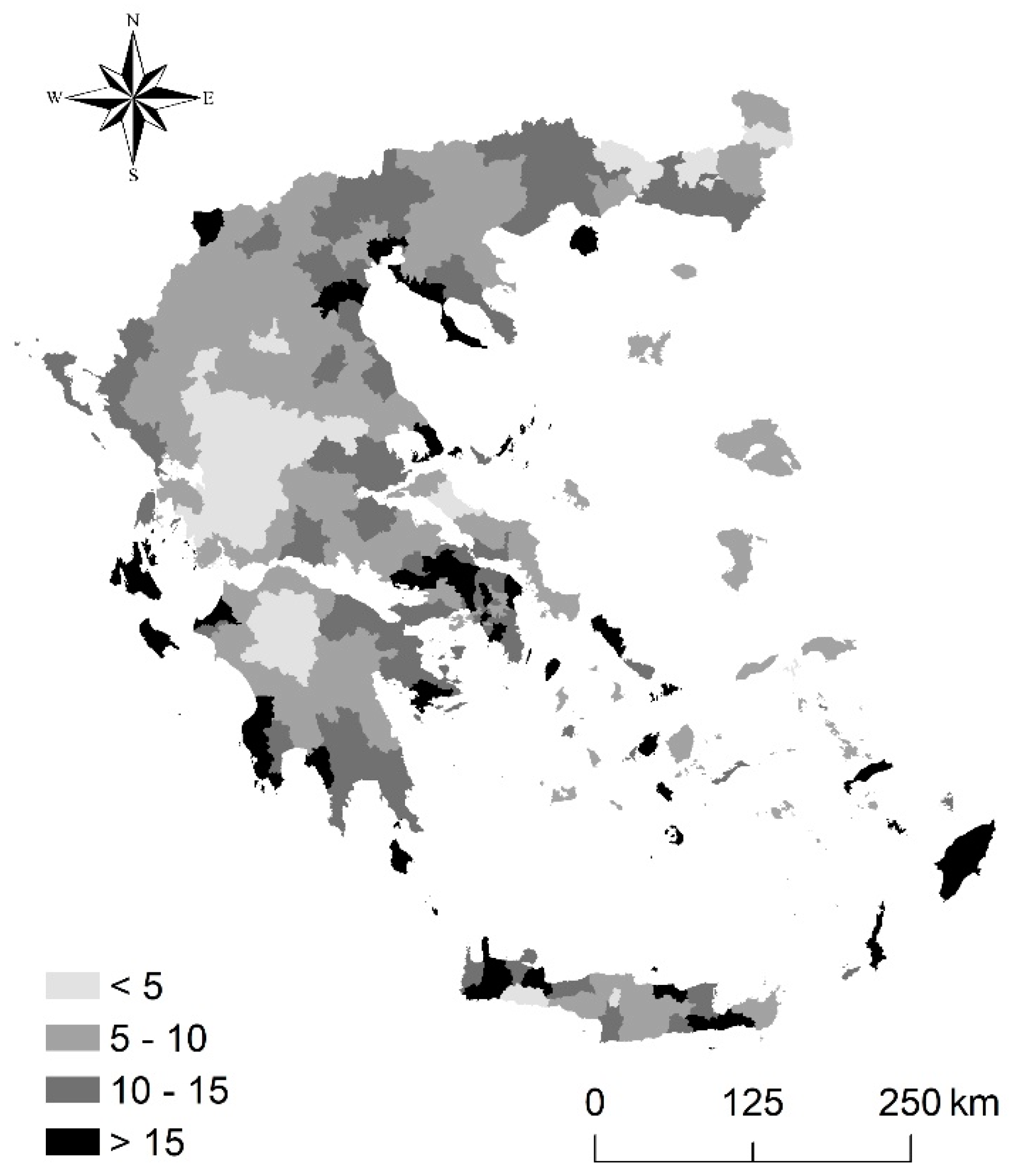

- Salvati, L.; Benassi, F. Rise (and Decline) of European Migrants in Greece: Exploring Spatial Determinants of Residential Mobility (1988–2017), with Special Focus on Older Ages. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.K. German Second Homeowners in the Swedish Countryside: On the Internationalization of the Leisure Space. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Social and Economic Geography, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, M.; O’Reilly, K. Lifestyle Migration: Expectations, Aspirations and Experiences; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, P. Your home in Spain: Residential Strategies in International Retirement Migration. In Lifestyle Migrations: Expectations, Aspirations and Experiences; Benson, M., O’Reilly, K., Eds.; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hannonen, O. Second homeowners as tourism trend-setters: A case of residential tourists in Gran Canaria. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2018, 6, 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Burholt, V. Transnationalism, economic transfers and families’ ties: Intercontinental contacts of older Gujaratis, Punjabis and Sylhetis in Birmingham with families abroad. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2004, 27, 800–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Vullnetari, J. Orphan pensioners and migrating grandparents: The impact of mass migration on older people in rural Albania. Ageing Soc. 2006, 26, 783–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramji, H. British Indians ‘Returning Home’: An Exploration of Transnational Belongings. Sociology 2006, 40, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; King, R.; Warnes, T. A place in the sun: International retirement migration from northern to southern Europe. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 1997, 4, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P. Migrant Populations Approaching Old Age: Prospects in Europe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2006, 32, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño-Castellano, J.; Domínguez-Mujica, J. Working and retiring in sunny Spain: Lifestyle migration further explored. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2017, 65, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort, J.G.; Hall, K.; Betty, C. Back to Brit: Retired British migrants returning from Spain. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2016, 42, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Peer-Led Care Practices and ‘Community’ Formation in British Retirement Migration. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 2017, 7, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, D.; Redrobán, V. Retirement here or there? Ageing-migrants’ transnational social protection strategies. In Boletín OEG de Investigación; European Observatory on Gerontomigration (OEG): Malaga, Spain, 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, K. Intra-European Migration and the Mobility—Enclosure Dialectic. Sociology 2007, 41, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldron, K.; Ackers, L. Using European Citizenship? EU Retired Migrants and the Exercise of Healthcare Rights. Maastricht J. Eur. Comp. Law 2007, 14, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K. Retirement migration and health: Growing old in Spain. In Handbook of Migration and Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; p. 402. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, K.; Hardill, I. Retirement migration, the ‘other’ story: Caring for frail elderly British citizens in Spain. Ageing Soc. 2014, 36, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Warnes, A.M.; Williams, A.M. Sunset Lives: British Retirement Migration to the Mediterranean; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ackers, L.; Dwyer, P. Senior Citizenship? Retirement, Migration and Welfare in the European Union; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, R.D. International retirees at the polls: Spanish local elections 2015. RIPS 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Transnationalism in retirement migration: The case of North European retirees in Spain. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2008, 31, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, K. The British on the Costa del Sol: Transnational Identities and Local Communities; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gavanas, A.; Calzada, I. Multiplex Migration and Aspects of Precarization: Swedish Retirement Migrants to Spain and their Service Providers. Crit. Sociol. 2016, 42, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo, F. European retirees on the Costa del Sol: A cross-national comparison. Int. J. Popul. Geogr. 1998, 4, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyurt, P.M.; Başaran, M.A.; Kantarcı, K. Residential Tourists’ Perceptions of Quality of Life: Case of Alanya, Turkey. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 6, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, V.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo-Pérez, F. International Retirement Migration: Retired Europeans Living on the Costa Del Sol, Spain. Popul. Rev. 2004, 43, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnes, A. Older migrants in Europe: Essays, Projects and Sources; Sheffield Institute for Studies on Ageing: Sheffield, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, J.B.; Gil-Alonso, F. Suburbanisation and international immigration: The case of the Barcelona Metropolitan Region (1998–2009). Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2011, 103, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Tourism and seasonal retirement migration. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 899–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Díaz, M.A.; Kaiser, C.; Warnes, A.M. Northern European retired residents in nine southern European areas: Characteristics, motivations and adjustment. Ageing Soc. 2004, 24, 353–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, T. Retirement Migration or rather Second-Home Tourism? German Senior Citizens on the Canary Islands. Die Erde 2005, 136, 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bolzman, C.; Kaeser, L.; Christe, E. Transnational mobilities as a way of life among older migrans from southern Europe. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.A. Retirement Migration in Spain: Two Cases Studies in Catalonian and Mallorca. MOJ Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 3, 00072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hall, C.M.; Müller, D.K. The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Incerti, G.; Feoli, E.; Salvati, L.; Brunetti, A.; Giovacchini, A. Analysis of bioclimatic time series and their neural network-based classification to characterise drought risk patterns in South Italy. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2006, 51, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Ciommi, M.T.; Serra, P.; Chelli, F.M. Exploring the spatial structure of housing prices under economic expansion and stagnation: The role of socio-demographic factors in metropolitan Rome, Italy. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Ciuraneta, S.; Durà-Guimerà, A.; Salvati, L. Not only tourism: Unravelling suburbanization, second-home expansion and “rural” sprawl in Catalonia, Spain. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piga, A.; Gambella, F.; Vacca, V.; Agabbio, M.C.S. Response of three Sardinian olive cultivars to Greek-style processing. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2001, 13, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bayona-I-Carrasco, J.; Gil-Alonso, F. Is Foreign Immigration the Solution to Rural Depopulation? The Case of Catalonia (1996–2009). Sociol. Rural. 2012, 53, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, C.; Heins, F. Long-term trends of internal migration in Italy. Int. J. Popul. Geogr. 2000, 6, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieleman, F.M. Modelling residential mobility; a review of recent trends in research. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2001, 16, 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. Retirement Migration: Paradoxes of Ageing; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hardill, I.; Spradbery, A.; Arnold-Boakes, J.; Marrugat, M.L. Severe health and social care issues among British migrants whore tire to Spain. Ageing Soc. 2005, 25, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morote, Á.F.; Sauri, D.; Hernández, M. Residential Tourism, Swimming Pools, and Water Demand in the Western Mediterranean. Prof. Geogr. 2016, 69, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnes, A.M.; Williams, A. Older Migrants in Europe: A New Focus for Migration Studies. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2006, 32, 1257–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.; O’Reilly, K. North-Europeans in Spain: Practices of community in the context of migration, mobility and transnationalism. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 2017, 7, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavanas, A. Swedish Retirement Migrant Communities in Spain: Privatization, informalization and moral economy filling transnational care gaps1. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 2017, 7, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernsten, A.; Mccollum, D.; Feng, Z.; Everington, D.; Huang, Z. Using linked administrative and census data for migration research. Popul. Stud. 2018, 72, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; King, R.; Warnes, A.; Patterson, G. Tourism and international retirement migration: New forms of an old relationship in southern Europe. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, H.; Hoggart, K. International Counterurbanization: British Migrants in Rural France; Aldershot: Avebury, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Montezuma, J.; McGarrigle, J. What motivates international homebuyers? Investor to lifestyle ‘migrants’ in a tourist city. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 21, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciommi, M.; Gigliarano, C.; Emili, A.; Taralli, S.; Chelli, F.M. A new class of composite indicators for measuring well-being at the local level: An application to the Equitable and Sustainable Well-being (BES) of the Italian Provinces. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 76, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassinari, P.; Torreggiani, D.; Benni, S. Dealing with agriculture, environment and landscape in spatial planning: A discussion about the Italian case study. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torreggiani, D.; Tassinari, P. Landscape quality of farm buildings: The evolution of the design approach in Italy. J. Cult. Heritage 2012, 13, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Tomaselli, G.; Pappalardo, G. Marginal periurban agricultural areas: A support method for landscape planning. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cánoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Priestley, G.K.; Blanco, A. Rural tourism in Spain: An analysis of recent evolution. Geoforum 2004, 35, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, I.; Ayuga, E.; Ayuga, F. A contribution to the assessment of scenic quality of landscapes based on preferences expressed by the public. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.; Gallego, E.; García, A.; Ayuga, F. New uses for old traditional farm buildings: The case of the underground wine cellars in Spain. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeterier, J. Dominant attributes in the perception and evaluation of the Dutch landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1996, 34, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranca, A.; Braduceanu, D.; Mihailescu, F.; Popescu, M. Wines routes in Dobrogea: Solution for a sustainable development of the local agrotouristic potential. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2007, 8, 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch, N.; Haase, D. Diversifying European agglomerations: Evidence of urban population trends for the 21st century. Popul. Space Place 2011, 17, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeson, N.; Quaranta, G.; Salvia, R.; Brandt, J. Long-term involvement of stakeholders in research projects on desertification and land degradation: How has their perception of the issues changed and what strategies have emerged for combating desertification? J. Arid. Environ. 2015, 114, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croucher, S. Privileged Mobility in an Age of Globality. Societies 2012, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazón, T. Inquiring into residential tourism: The Costa Blanca case. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2006, 3, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleran, M. Residential tourists and the half-life of European cosmopolitanism in post-crisis Spain. J. Sociol. 2016, 53, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Brochado, A.; Correia, A. Seniors in international residential tourism: Looking for quality of life. Anatolia 2017, 29, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.K. Reinventing the Countryside: German Second-home Owners in Southern Sweden. Curr. Issues Tour. 2002, 5, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Second Home Tourism: An International Review. Tour. Rev. Int. 2014, 18, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, A.M.; Mccollum, D.; Coulter, R.; Gayle, V. New Mobilities Across the Life Course: A Framework for Analysing Demographically Linked Drivers of Migration. Popul. Space Place 2015, 21, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkington, K. Place and Lifestyle Migration: The Discursive Construction of ‘Glocal’ Place-Identity. Mobilities 2012, 7, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Duncan, T.; Thulemark, M. Lifestyle Mobilities: The Crossroads of Travel, Leisure and Migration. Mobilities 2013, 10, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón, J. Residential tourism and depeasantisation in the Ecuadorian Andes. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 43, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zontini, E. Growing old in a transnational social field: Belonging, mobility and identity among Italian migrants. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2014, 38, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavalas, V.S.; Rontos, K.; Salvati, L. Who Becomes an Unwed Mother in Greece? Sociodemographic and Geographical Aspects of an Emerging Phenomenon. Popul. Space Place 2014, 20, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimis, C. Survival and expansion: Migrants in Greek rural regions. Popul. Space Place 2008, 14, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollet, D.; Callois, J.-M.; Roussel, V. Impact of retirees on rural development: Some observations from the South of France. J. Reg. Anal. Policy 2005, 35, 54–74. [Google Scholar]

- Longino, C.F.; Perzynski, A.T.; Stoller, E.P. Pandora’s Briefcase: Unpacking the Retirement Migration Decision. Res. Aging 2002, 24, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, W.; Meekes, H. Trends in European cultural landscape development: Perspectives for a sustainable future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 46, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P.J. Movements to some purpose? An exploration of international retirement migration in the European Union. Educ. Ageing 2000, 15, 353–377. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.-K.; Horner, M.W.; Marans, R.W. Life Cycle and Environmental Factors in Selecting Residential and Job Locations. Hous. Stud. 2005, 20, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater, A.; Graham, E.; Finney, N. The spatialities of ageing: Evidencing increasing spatial polarisation between older and younger adults in England and Wales. Demogr. Res. 2017, 36, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marois, G.; Lord, S.; Negron-Poblete, P. The Residential Mobility of Seniors Among Different Residential Forms: Analysis of Metropolitan and Rural Issues for Six Contrasted Regions in Québec, Canada. J. Hous. Elder. 2017, 32, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, W.H. Later-Life Migration in the United States: A Review of Recent Research. J. Plan. Lit. 2002, 17, 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeant, J.F.; Ekerdt, D.J. Motives for Residential Mobility in Later Life: Post-Move Perspectives of Elders and Family Members. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008, 66, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, A.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cagney, K.A. Racial Differences in the Effects of Neighborhood Disadvantage on Residential Mobility in Later Life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2016, 71, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilkey, M.; Perrons, D.; Plomien, A. Gender, Migration and Domestic Work. Masculinities, Male Labour and Fathering in the UK and USA; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.; Warnes, A.M.; Williams, A.M. International retirement migration in Europe. Int. J. Popul. Geogr. 1998, 4, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, P.D.; Caliandro, L.P. The role of historical agro-industrial buildings in the study of rural territory. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 96, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, S.M.C.; Leanza, P.M.; Cascone, G. Developing Interpretation Plans to Promote Traditional Rural Buildings as Built Heritage Attractions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 14, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.I.; Ayuga, F. Reuse of Abandoned Buildings and the Rural Landscape: The Situation in Spain. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Garzón, E.; Sánchez-Soto, P.J. Historic preservation, GIS, & rural development: The case of Almería province, Spain. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 42, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Barke, M.; Towner, J.; Newton, M.T. Tourism in Spain: Critical Issues; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barbero-Sierra, C.; Marques, M.J.; Ruiz-Perez, M. The case of urban sprawl in Spain as an active and irreversible driving force for desertification. J. Arid. Environ. 2013, 90, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, I.; Cecchini, M.; Egidi, G.; Saporito, M.G.; Colantoni, A. Revolution 4.0: Industry vs. Agriculture in a Future Development for SMEs. Processes 2019, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, I.; Cerdà, A.; Gambella, F.; Egidi, G.; Salvati, L. Industrial Sprawl and Residential Housing: Exploring the Interplay between Local Development and Land-Use Change in the Valencian Community, Spain. Land 2019, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.; Chelli, F.M.; Salvati, L. Toward a New Cycle: Short-Term Population Dynamics, Gentrification, and Re-Urbanization of Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciommi, M.; Chelli, F.M.; Carlucci, M.; Salvati, L. Urban Growth and Demographic Dynamics in Southern Europe: Toward a New Statistical Approach to Regional Science. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetti, M.; Phillipson, C.; Calasanti, T. Retirement Migration in Europe: A Choice for a Better Life? Sociol. Res. Online 2018, 23, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.K.; Abramsson, M. Changing residential mobility rates of older people in Sweden. Ageing Soc. 2011, 32, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelli, F.; Rosti, L. Age and gender differences in Italian workers’ mobility. Int. J. Manpow. 2002, 23, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnetti, C.; Chelli, F.; Rosti, L. Educational performance as signalling device: Evidence from Italy. Econ. Bull. 2005, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chelli, F.M.; Ciommi, M.; Emili, A.; Gigliarano, C.; Taralli, S. Assessing the Equitable and Sustainable Well-Being of the Italian Provinces. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 24, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigliarano, C.; Chelli, F.M. Measuring inter-temporal intragenerational mobility: An application to the Italian labour market. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V. Tourism as a recruiting post for retirement migration. Tour. Geogr. 2001, 3, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelli, F.; Gigliarano, C.; Mattioli, E. The Impact of Inflation on Heterogeneous Groups of Households: An application to Italy. Econ. Bull. 2009, 29, 1276–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Rosti, L.; Chelli, F. Higher education in non-standard wage contracts. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosti, L.; Chelli, F. Self-employment among Italian female graduates. Educ. Train. 2009, 51, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Colantoni, A.; Mosconi, E.M.; Poponi, S.; Fortunati, S.; Salvati, L.; Gambella, F. From Historical Narratives to Circular Economy: De-Complexifying the “Desertification” Debate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 8.166 | 8.363 | 9.623 | 11.282 | 12.682 |

| Germany | 4.913 | 5.405 | 5.188 | 5.463 | 5.471 |

| France | 4.638 | 4.368 | 4.910 | 4.167 | 4.580 |

| Poland | 3.364 | 2.055 | 1.763 | 3.023 | 2.180 |

| Switzerland | 1.920 | 1.710 | 1.492 | 1.211 | 1.169 |

| Italy | 1.770 | 1.836 | 1.958 | 2.159 | 2.424 |

| Hungary | 1.126 | 1.088 | 1.063 | 1.133 | 1.144 |

| Belgium | 1.068 | 1.078 | 1.159 | 1.135 | 1.124 |

| Luxembourg | 627 | 543 | 383 | 349 | 306 |

| Sweden | 572 | 609 | 594 | 572 | 532 |

| Portugal | 474 | 734 | 766 | 880 | 827 |

| Croatia | 366 | 345 | 339 | 350 | 415 |

| Netherlands | 356 | 421 | 391 | 512 | 518 |

| Czechia | 275 | 305 | 662 | 338 | 341 |

| Bulgaria | 221 | 225 | 197 | 93 | 178 |

| Norway | 210 | 134 | 152 | 121 | 141 |

| Denmark | 176 | 166 | 162 | 170 | 181 |

| Cyprus | 146 | 190 | 117 | 187 | 122 |

| Finland | 84 | 78 | 85 | 82 | 81 |

| Slovakia | 56 | 85 | 93 | 64 | 75 |

| Lithuania | 28 | 9 | 22 | 34 | 26 |

| Latvia | 20 | 28 | 26 | 37 | 43 |

| Iceland | 17 | 17 | 16 | 25 | 22 |

| Liechtenstein | 13 | 22 | 14 | 10 | 6 |

| Estonia | 5 | 127 | 110 | 149 | 142 |

| Year | Inflows from Abroad (Absolute Numbers) | Per Cent Share of >60 Years EU Incoming Residents in Total EU Incoming Residents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incoming Residents | With EU Citizenship | 60 Years and above | ||

| 2008 | 66.529 | 11.638 | 565 | 4.9 |

| 2009 | 58.613 | 12.205 | 718 | 5.9 |

| 2010 | 60.462 | 12.732 | 906 | 7.1 |

| 2011 | 60.089 | 12.945 | 953 | 7.4 |

| 2012 | 58.200 | 14.451 | 1.042 | 7.2 |

| 2013 | 57.946 | 15.056 | 1.084 | 7.2 |

| 2014 | 59.013 | 16.043 | 1.407 | 8.8 |

| 2015 | 64.446 | 16.572 | 1.454 | 8.8 |

| 2016 | 116.867 | 16.706 | 1.480 | 8.9 |

| 2017 | 112.247 | 17.261 | 1.523 | 8.9 |

| 2018 | 119.489 | 19.052 | 1.425 | 7.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Egidi, G.; Quaranta, G.; Salvati, L.; Gambella, F.; Mosconi, E.M.; Giménez Morera, A.; Colantoni, A. Unraveling Causes and Consequences of International Retirement Migration to Coastal and Rural Areas in Mediterranean Europe. Land 2020, 9, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110410

Egidi G, Quaranta G, Salvati L, Gambella F, Mosconi EM, Giménez Morera A, Colantoni A. Unraveling Causes and Consequences of International Retirement Migration to Coastal and Rural Areas in Mediterranean Europe. Land. 2020; 9(11):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110410

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgidi, Gianluca, Giovanni Quaranta, Luca Salvati, Filippo Gambella, Enrico Maria Mosconi, Antonio Giménez Morera, and Andrea Colantoni. 2020. "Unraveling Causes and Consequences of International Retirement Migration to Coastal and Rural Areas in Mediterranean Europe" Land 9, no. 11: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110410

APA StyleEgidi, G., Quaranta, G., Salvati, L., Gambella, F., Mosconi, E. M., Giménez Morera, A., & Colantoni, A. (2020). Unraveling Causes and Consequences of International Retirement Migration to Coastal and Rural Areas in Mediterranean Europe. Land, 9(11), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110410