The Value Assessment and Planning of Industrial Mining Heritage as a Tourism Attraction: The Case of Las Médulas Cultural Space

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Tourism Planning and Value Assessment of Industrial Mining Heritage as a Tourism Resource

3. Methodological Design

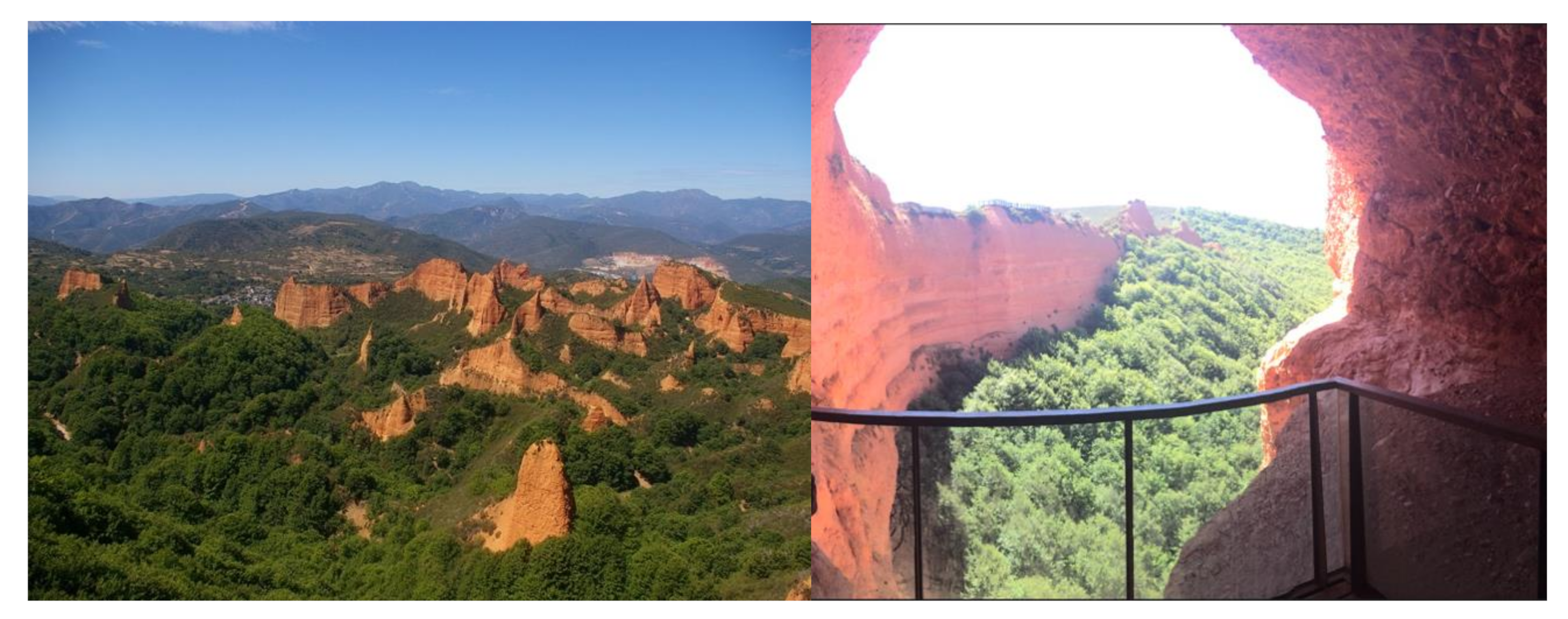

4. The Case of Las Médulas: From a Vast Roman Mine to a Historical and Natural Monument

4.1. Context Analysis

4.2. Evolution of Planning and Management in Las Médulas

5. Analysis and Discussion of Results

5.1. Residents’ Support for Tourism Development

5.2. Multidimensional Nature of the Tourism Impacts

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Llurdés i Coit, J.C. El turismo industrial y la estética de los paisajes en declive. Estud. Turísticos 1999, 121, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Benito del Pozo, P. Industria y patrimonialización del paisaje urbano: La reutilización de las viejas fábricas. In Ciudad, Territorio y Paisaje: Reflexiones Para un Debate Multidisciplinar; Cornejo Nieto, C., Morán Sáez, J., Prada Trigo, J., Eds.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 354–366. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Abad, J.C.; Fernández Álvarez, J. Landscape as digital content and a smart tourism resource in the mining area of Cartagena-La Unión (Spain). Land 2020, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benito del Pozo, P.; Calderón, B.; Ruiz-Valdepeñas, H.P. La gestión territorial del patrimonio industrial en Castilla y León (España): Fábricas y paisajes. Investig. Geográficas 2016, 90, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yashalova, N.N.; Akimova, M.A.; Ruban, D.A.; Boiko, S.V.; Usova, A.V.; Mustafaeva, E.R. Prospects for regional development of industrial tourism in view of the analysis of the main economic indicators of russian tourism industry. Econ. Soc. Chang. Facts Trends 2017, 10, 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hortelano Mínguez, L.A. Turismo minero en territorios en desventaja geográfica de Castilla y León: Recuperación del patrimonio industrial y opción de desarrollo local. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 27, 521–539. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela Rubio, M.; Palacios García, A.J.; Hidalgo Giralt, C. La valorización turística del patrimonio minero en entornos rurales desfavorecidos: Actores y experiencias. Cuad. Tur. 2008, 22, 231–260. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/48201 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Cañizares Ruiz, M.C. Protección y defensa del patrimonio minero en España. Scr. Nova 2011, 15. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-361.htm (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Edwards, J.A.; Llurdés, I.; Coit, C.L. Mines and quarries: Industrial heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.J. Industrial heritage tourism and regional restructuring in the European Union. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; López, T.; Millán, G. El turismo industrial minero como motor de desarrollo en áreas geográficas en declive. Un estudio de caso. Estud. Y Perspect. En Tur. 2010, 19, 382–393. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. El patrimonio industrial en España: Análisis turístico y significado territorial de algunos proyectos de recuperación. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2010, 53, 239–264. Available online: https://bage.age-geografia.es/ojs/index.php/bage/article/view/1200 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Cueto Alonso, G.J. Nuevos usos turísticos para el patrimonio minero en España. PASOS 2016, 14, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.M.; Rey, F.J.; Caridad, J.M. Dinamización del patrimonio industrial minero en el marco de la comarca cordobesa del valle del alto Guadiato. IJOSMT 2017, 1, 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- Conesa, H.M. The difficulties in the development of mining tourism projects: The case of La Unión Mining District. PASOS 2010, 8, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Herman, K. A Business Creation in Post-Industrial Tourism Objects: Case of the Industrial Monuments Route. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Llurdés i Coit, J.C.; Díaz Soria, I.; Romagosa, F. Patrimonio minero y turismo de Proximidad: Explorando sinergias. El caso de Cardona. Doc. De Análisis Geográfico 2016, 62, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandez-Posse, M.D.; Menendez, E.; Sánchez-Palencia, F.J. El paisaje cultural de las Medulas. Treb. D’arqueologia 2002, 8, 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Orduña, F.J. Turismo, patrimonio natural y medio ambiente. Rev. desarro. Rural Coop. Agrar. 2002, 4, 95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Otgaar, A. Towards a common agenda for the development of industrial tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukosav, S.; Garača, V.; Ćurčić, N.; Bradić, M. Industrial Heritage of Novi Sad in the Function of Industrial Tourism: The Creation of New Tourist Products. Int. Sci. Conf. Geobalcanica 2015, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Palomeque, F.L. Planificación territorial del turismo y sostenibilidad: Fundamentos, realidades y retos. Tur. Y Soc. 2007, 8, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge, D.; Jamal, T. Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baños Castiñeira, C.J. Modelos turísticos locales. Análisis comparado de dos destinos de la Costa Blanca. Investig. Geográficas 1999, 21, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merinero, R.; Zamora, E. La colaboración entre actores turísticos en ciudades patrimoniales. PASOS 2009, 3, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón, F. Sostenibilidad y planificación: Ejes del desarrollo turístico sostenible. DELOS 2010, 3, 1–11. Available online: www.eumed.net/rev/delos/08 (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Vera Rebollo, J.F. Planificación turística en España. De los paradigmas tradicionales a los nuevos enfoques: Planificación turística inteligente. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2019, 82, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; So, K.K.F. Residents’ support for tourism: Testing alternative structural models. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feifan Xie, P.; Younghee Lee, M.; Jweng-Chou, J. Assessing community attitudes toward industrial heritage tourism development. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 18, 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.P.; Cole, S.S.T.; Chancellor, C. Resident Support for Tourism Development in Rural Midwestern (USA) Communities: Perceived Tourism Impacts and Community Quality of Life Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Mang. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Mejia, M.D.L.Á.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.; Valentine, K.; Knopf, R.; Vogt, C. Residents´ perceptions on community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Song, H.; Chen, N.; Shang, W. Roles of tourism involvement and place attachment in determining residents’ attitudes toward industrial heritage tourism in a resource-exhausted city in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benito del Pozo, P. Patrimonio industrial y Cultura del Territorio. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2002, 1, 213–227. Available online: http://age.ieg.csic.es/boletin/34/3415.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Pardo Abad, C.J. La reutilización del patrimonio industrial como recurso turístico. Aproximación geográfica al turismo industrial. Treb. De La Scg. 2004, 57, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, M. Gestión turística del patrimonio cultural: Enfoques para un desarrollo sostenible del turismo cultural. Cuad. Tur. 2009, 23, 237–253. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/70121 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Miller, G.; Rathouse, K.; Scarles, C.; Holmes, K.; Tribe, J. Public understanding of sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res 2010, 37, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Concetta Perfetto, M.; Vargas-Sánchez, A. Towards a Smart Tourism Business Ecosystem based on Industrial Heritage: Research perspectives from the mining region of Rio Tinto, Spain. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V. Turismo industrial: Uma abordagem metodogólica para o territorio. Rev. Tur. Desenvolvimiento 2012, 1, 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán Ramos, A.; Fernández, G.; Ricci, S.; Valenzuela, S. Patrimonio minero-industrial y turismo: Propuesta de ecomuseo en una localidad de Argentina. Rev. Hosp. 2014, 11, 178–194. Available online: https://www.revhosp.org/hospitalidade/article/view/548/583 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Makua, A. Revisión del proceso de valorización de los recursos base del turismo industrial. ROTUR 2011, 4, 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Antón Clavé, S.; González Reverté, F. A Propósito del Turismo: La Construcción Social del Espacio Turístico; UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cueto Alonso, G.J. El patrimonio industrial como motor de desarrollo económico. Patrim. Cult. De España 2010, 3, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. The post-industrial landscapes of Riotinto and Almadén, Spain: Scenic value, heritage and sustainable tourism. J. Heritage Tour. 2017, 12, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat Forga, J.M.; Cánovas, G. El turismo cultural como oferta complementaria en los destinos de litoral: El caso de la Costa Brava (España). Investig. Geográficas 2012, 79, 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade Suárez, M.; Caamaño Franco, I. Theoretical and methodological model for the study of social perception of the impact of industrial tourism on local development. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cañizares Ruiz, M.C. Los límites del turismo industrial en áreas desfavorecidas. Cuad. Geogr. 2019, 58, 180–204. Available online: https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/cuadgeo/article/view/6746 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- García Delgado, F.J.; Delgado Domínguez, A.; Felicidades García, J. El turismo en la cuenca minera de Riotinto. Cuad. Tur. 2013, 31, 129–152. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/170791 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Díez Santo, D. La planificación estratégica en espacios turísticos de interior: Claves para el diseño y formulación de estrategias competitivas. Investig. Turísticas 2011, 1, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andriotis, K.; Vaughan, R. Urban residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: The case of Crete. JTR 2003, 42, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel Brida, J.G.; Daniel Monterubbianesi, P.; Zapata Aguirre, S. Impactos del turismo sobre el crecimiento económico y el desarrollo. El caso de los principales destinos turísticos de Colombia. PASOS 2011, 9, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Ferrando, M.; Alvira, F.; Enrique Alonso, L.; Escobar, M. El Análisis de la Realidad Social: Métodos y Técnicas de Investigación; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Monterrubio Cordero, J.C.; Mendoza Ontiveros, M.M.; Huitrón Tecotl, T.K. Percepciones de la comunidad local sobre los impactos sociales del "spring break" en Acapulco, México. Periplo Sutentable 2013, 24, 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Barbini, B.; Castellucci, D.I.; Corbo, Y.A.; Cruz, G.; Roldán, N.G.; Cacciutto, M. Comunidad residente y gobernanza turística en Mar del Plata. CONDET 2016, 16, 107–116. Available online: http://revele.uncoma.edu.ar/htdoc/revele/index.php/condet/article/view/1623/1659 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Cañizares Ruiz, M.C. El atractivo turístico de una de las minas de mercurio más importantes del mundo: El parque minero de Almadén (Ciudad Real). Cuad. Tur. 2008, 21, 9–31. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/24971 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Balado Insunza, F.M. Hacia la gestión unificada del espacio cultural y natural de las médulas: Anhelo teórico y necesidad urgente. REA 2018, 5, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monteserrín Abella, O. Espacios patrimoniales de intervención múltiple. Conflictos territoriales en torno al Plan de Dinamización Turística de las Médulas. PASOS 2019, 17, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Olivares, D. Los Recursos Turísticos. Evaluación, Ordenación y Planificación Turística. Estudio de Casos; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Sousa, A. The Problems of Tourist Sustainability in Cultural Cities: Socio-Political Perceptions and Interests Management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armis, S.; Kanegae, H. The attractiveness of a post-mining city as a tourist destination from the perspective of visitors: A study of Sawahlunto old coal mining town in Indonesia. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2020, 4, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Análisis Multivariante; Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. Environmental recovery of abandoned mining areas in Spain: Sustainability and new landscapes in some case studies. J. Sustain. Res. 2019, 1, e190003. [Google Scholar]

- Jakub, J. Mining heritage and mining tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2018, 7, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Rethinking the role of power and trust in tourism planning. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. Indicadores de sostenibilidad turística aplicados al patrimonio industrial y minero: Evaluación de resultados en algunos casos de estudio. Boletín De La Age 2014, 65, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz Hernández, A. Cierre de minas y patrimonialización. Microrresistencias reivindicativas institucionalizadas. Sociol. Del Trab. 2013, 77, 7–26. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/STRA/article/view/60572 (accessed on 25 May 2020).

| Objectives | Research Techniques |

|---|---|

| Study planning and management of industrial mining heritage as a tourist attraction in Las Médulas. | • In-depth review of bibliographical sources, technical documents and secondary data. • Informal interviews and conversation with actors and experts. |

| Identify the tourism impacts perceived by residents and the optimum predictors of support for this activity in the community. | • Bibliographical review. • Questionnaire to local population. |

| Offer Information Centers | Managing Entity |

|---|---|

| Archaeological hall of Las Médulas | Institute of Bercian Studies |

| Las Médulas Visitor Reception Center | Bierzo County Council |

| Canals Interpretation Center | Las Médulas Foundation |

| Orellán Gallery | Tourist Services Orellán |

| The Roman Domus | Council of El Bierzo |

| House of the “Parque de Las Médulas” | Jurbial Environmental Services |

| Complete Questionnaire (α = 0.87) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Economic impacts α = 0.32 | |

| Tourism is one of the main sources of income for the development of the local economy | 3.40 (1.21) |

| Tourism improves employment for the local population | 2.57 (1.06) |

| Tourism benefits only a limited number of residents | 3.57 (1.07) |

| Tourism attracts more investment to the area | 3.0 (1.16) |

| Total | 3.12 (0.67) |

| Cultural impacts α = 0.60 | |

| Tourism boosts the offer of cultural and recreational activities | 2.90 (1.09) |

| Tourism promotes greater cultural exchange | 3.44 (1.19) |

| Tourism offers an insight into the area’s history and culture | 4.11 (1.01) |

| Total | 3.19 (0.92) |

| Political-administrative impacts α = 0.68 | |

| The money invested by the institutions to attract more tourists has generated new facilities, infrastructures and events suitable for tourism | 2.84 (1.18) |

| Tourism development plans have improved the provision of infrastructure and public services | 3.02 (1.11) |

| Tourism contributes to promoting the maintenance and restoration of the historical and cultural heritage | 3.50 (1.18) |

| Total | 3.13 (0.95) |

| Social Impacts α = 0.47 | |

| Tourism contributes to increasing collaboration between local people, companies or institutions to carry out tourism activities | 2.52 (1.15) |

| Tourism causes problems of coexistence between tourists and residents | 1.80 (1.00) |

| Tourism contributes to improving and enhancing the destination’s value | 3.86 (1.10) |

| Total | 2.73 (0.76) |

| Environmental impacts α = 0.85 | |

| Tourism helps the destruction or deterioration of natural resources and the local ecosystem | 2.52 (1.42) |

| Tourism increases dirt, noise and pollution | 2.63 (1.42) |

| Tourism reduces the tranquility of the municipality and increases overcrowding in certain parts of the municipality | 2.70 (1.47) |

| Total | 2.62 (1.25) |

| Item | Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOT1 | MOT2 | MOT3 | MOT4 | MOT5 | |

| Tourism contributes to improving and enhancing the destination’s value | 0.908 | ||||

| Tourism contributes to promoting the maintenance and restoration of the historical and cultural heritage | 0.60 | ||||

| Tourism offers an insight into the area’s history and culture | 0.568 | ||||

| Tourism contributes to increasing collaboration between local people, companies or institutions to carry out tourism activities | 0.555 | ||||

| Tourism increases dirt, noise and pollution | 0.904 | ||||

| Tourism reduces the tranquility of the municipality and increases overcrowding in certain parts of the municipality | 0.843 | ||||

| Tourism helps the destruction or deterioration of natural resources and the local ecosystem | 0.679 | ||||

| Tourism causes problems of coexistence between tourists and residents | 0.435 | ||||

| Tourism boosts the offer of cultural and recreational activities | 0.910 | ||||

| Tourism promotes greater cultural exchange | 0.550 | ||||

| Tourism attracts more investment to the area | 0.431 | ||||

| Tourism development plans have improved the provision of infrastructure and public services | 0.626 | ||||

| The money invested by the institutions to attract more tourists has generated new facilities, infrastructures and events suitable for tourism | 0.510 | ||||

| Tourism benefits only a limited number of residents | 0.409 | ||||

| Tourism improves employment for the local population | 0.699 | ||||

| Tourism is one of the main sources of income for the development of the local economy | 0.610 | ||||

| Number of items | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| % of Variance | 26.837 | 15.697 | 8.777 | 8.390 | 6.810 |

| Cumulative % | 26.837 | 42.534 | 51.311 | 59.702 | 66.512 |

| Alfa de Cronbach | 0.32 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.85 |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity: = 419.825 (gl = 136; Sig < 0.001) Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) = 0.593 Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (16 Ítems) = 0.87 | |||||

| Residents′ Perceptions of Supporting Tourism Development | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| I support that the Las Médulas Cultural Park is the singular tourist attraction of the area | 3.82 (1.16) |

| I support tourism in Las Médulas because that way I can enjoy my town more | 3.05 (1.11) |

| In general, I support activities related to the recovery and revitalization of industrial heritage for tourist use. | 3.25 (1.18) |

| Total | 3.37 (0.85) |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.61 |

| Items | Component |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| In general, I support activities related to the recovery and revitalization of industrial heritage for tourist use. | 0.772 |

| I support that the Las Médulas Cultural Park is the singular tourist attraction of the area | 0.741 |

| I support tourism in Las Médulas because that way I can enjoy my town more | 0.718 |

| Number of items | 3 |

| % of Variance | 55.318 |

| Cumulative % | 55.318 |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity: = 17.909 (gl = 3; Sig < 0.001) Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) = 0.633 Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (3 Ítems) = 0.32 | |

| Components | Coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Beta Coefficients | T Value | Sig. | |

| Constant | 0.117 | 0.908 | |

| F1: Tourism value assessment of the image and historical and cultural heritage | 0.613 | 5.727 | <0.001 |

| F2: Social and environmental consequences | 0.190 | 1.752 | 0.087 |

| F3: Economic and cultural impact | 0.127 | 1.066 | 0.292 |

| F4: Tourism planning and policies | 0.027 | 0.230 | 0.819 |

| F5: Financial management of tourism | 0.285 | 2.595 | 0.013 |

| R Pearson: 0.710 R2: 0.504; R2 corrected: 0.447 Standard error of estimation: 0.51841 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caamaño-Franco, I.; Suárez, M.A. The Value Assessment and Planning of Industrial Mining Heritage as a Tourism Attraction: The Case of Las Médulas Cultural Space. Land 2020, 9, 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110404

Caamaño-Franco I, Suárez MA. The Value Assessment and Planning of Industrial Mining Heritage as a Tourism Attraction: The Case of Las Médulas Cultural Space. Land. 2020; 9(11):404. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110404

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaamaño-Franco, Iria, and María Andrade Suárez. 2020. "The Value Assessment and Planning of Industrial Mining Heritage as a Tourism Attraction: The Case of Las Médulas Cultural Space" Land 9, no. 11: 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110404