Abstract

At the 2018 meeting of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape (PECSRL), that took place in Clermont-Ferrand and Mende in France, the Institute for Research on European Agricultural Landscapes e.V. (EUCALAND) Network organized a session on traditional landscapes. Presentations included in the session discussed the concept of traditional, mostly agricultural, landscapes, their ambiguous nature and connections to contemporary landscape research and practice. Particular attention was given to the connection between traditional landscapes and regional identity, landscape transformation, landscape management, and heritage. A prominent position in the discussions was occupied by the question about the future of traditional or historical landscapes and their potential to trigger regional development. Traditional landscapes are often believed to be rather stable and slowly developing, of premodern origin, and showing unique examples of historical continuity of local landscape forms as well as practices. Although every country has its own traditional landscapes, globally seen, they are considered as being rare; at least in Europe, also as a consequence of uniforming CAP (Common Agricultural Policy) policies over the last five decades. Although such a notion of traditional landscapes may be criticized from different perspectives, the growing number of bottom-up led awareness-raising campaigns and the renaissance of traditional festivities and activities underline that the idea of traditional landscapes still contributes to the formation of present identities. The strongest argument of the growing sector of self-marketing and the increasing demand for high value, regional food is the connection to the land itself: while particular regions and communities are promoting their products and heritages. In this sense, traditional landscapes may be viewed as constructed or invented, their present recognition being a result of particular perceptions and interpretations of local environments and their pasts. Nevertheless, traditional landscapes thus also serve as a facilitator of particular social, cultural, economic, and political intentions and debates. Reflecting on the session content, four aspects should be emphasized. The need for: dynamic landscape histories; participatory approach to landscape management; socioeconomically and ecologically self-sustaining landscapes; planners as intermediaries between development and preservation.

1. Introduction

The “Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape” (PECSRL; http://www.pecsrl.org/) is a series of conferences as well as an international network of research on landscape. Since the first meeting in 1956, conferences are held every two years [1,2]. The researches do not only focus on the past, but also on the present and the future of European landscapes of all kinds. PECSRL also serves as an international platform for developing new initiatives, meetings, and publications. Participants and interested parties meet every two years in various European countries for oral presentations, scientific poster exhibitions, lectures, discussions, and work group meetings. Field trips are included in the main program, some post-conference tours are also proposed. PECSRL has several working groups that focus on discussing actual problems of diverse European landscapes and their possible solutions.

The 28th PECSRL conference was organized in Clermont-Ferrand and Mende (France) at the beginning of September 2018. As part of this conference, the Institute for Research on European Agricultural Landscapes e.V. (EUCALAND, http://www.eucaland.net/) organized a special session on ‘Traditional landscapes: Exploring the Connections between Landscape, Identity, Heritage, and Change’. It proved to be an important topic, with an overall of 17 contributions. In this conference report, we give a short summary of the presentations including the afterwards discussions because they, in the opinion of the authors, deserve a wider public attention. Many of the presentations themselves will be published in a series of proceedings in two journals—AUC Geographica (www.aucgeographica.cz) and Hungarian Journal of Landscape Ecology (Tájökológiai Lapok: http://tajokologiailapok.szie.hu) in 2019.

2. The Topic of Traditional Landscapes

The concept of traditional landscapes is quite popular in landscape management. It is a starting point to protect landscapes and landscape features against a number of modern processes, such as scale enlargement, the loss of landscape character, and biodiversity (see [3] as example for these trends).

The term traditional landscape is used unequally in various parts of Europe, depending on their cultural, historical, and language differences. However, despite variabilities in their perception, traditional landscapes (all different types: agricultural, forestry, mining, etc.) almost always represent environments in peripheral locations that are believed to be rather stable or slowly developing and showing examples of historical continuity in landscape forms and practices [4,5]. Given its connection to the concept of tradition [6], recognition of a certain landscape as traditional does not necessarily depend on its actual period of duration, as on its common acceptance as being often idealized representative of the past times and practices, and thus contributing to shared identity and heritage. The notion of traditional landscapes helps to deal with intensive and omnipresent modern landscape changes [7,8].

For example, during the Socialist period [9] (Figure 1), in a number of countries in Central and Eastern Europe, collectivization (as a social-political process), which was more or less always combined with land consolidation (as a landscape process), significantly contributed to the changes in field-patterns and transformations of the character of intensive agricultural landscapes. Only in marginal highland and mountain areas with extensive agriculture the impact of land consolidation on landscape structure was less drastic, and in some areas traces of former landscape structures were preserved [10] (Figure 2). Landscapes in those areas in which at least parts of their former structures survived, are often called traditional [7]. In these cases, today, landscape management most often aims at preserving these traces for various reasons, e.g., positive conditions for a high degree of biodiversity, but also inhabitants and tourists mostly prefer diversified environments, for visual aspects as well as for their personal well-being [11,12,13].

Figure 1.

The result of Hungarian collectivization: huge agricultural fields with very few other landscape elements (one tree-line in the background on the right), resulting in serious soil degradation (from water erosion—as on this photo—to salinization) and other environmental, nature conservation, and socioeconomic problems; Somogydöröcske, Somogy County, Hungary, 2010. Photo: Csaba Centeri.

Figure 2.

The village of Königswalde still shows a number of strip-fields that represent the medieval planned settlement. Within the former East Germany, it is exceptional and the village uses this landscape as one of its characteristics, although elsewhere, in Central and Eastern Europe, similar examples of such villages exist. Photograph: Rauenstein, 2007, under Wikimedia Commons license.

In many other parts of Europe, the landscape developed more gradually. Even when Western-European governments used land consolidation procedures to adapt landscapes to large-scale agriculture, such projects took place over a long period of time and significant variations occurred in the way the landscape was transformed (Figure 3).

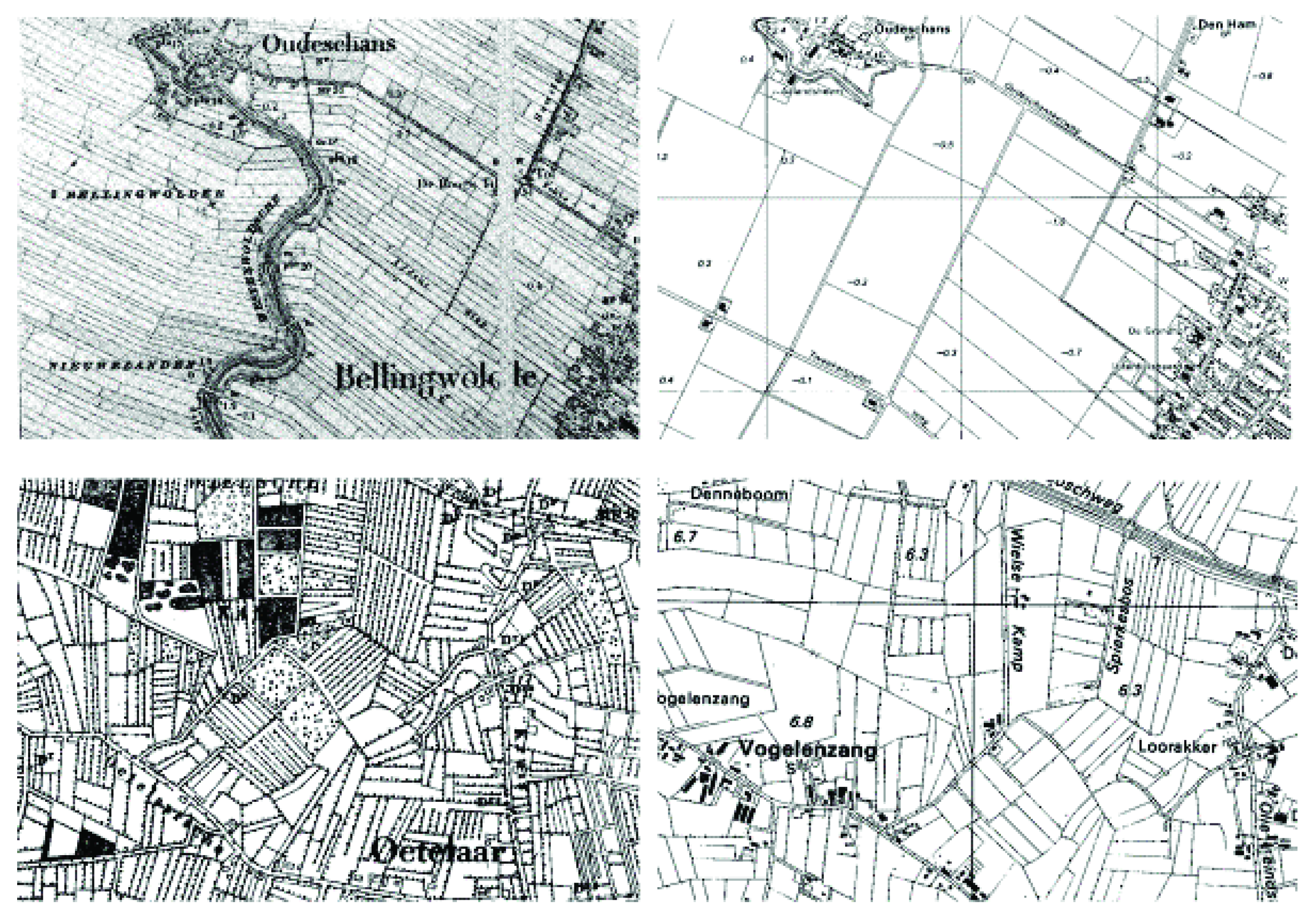

Figure 3.

Different degrees of change in Dutch agricultural regions, with fragments of topographical maps from c. 1900 and recent. The upper pictures show the extremely drastic changes by land consolidation. In fact, such changes are usually connected to state intervention and, in Western Europe, can only have been functional within the highly subsidized system of the early years of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The two fragments below show more gradual change, in which usually parts of the older landscape structures remain recognizable. Source: Kadaster, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands under Wikimedia Commons license.

Figure 3 shows two regions in which the landscape changed during the second half of the 20th century. Whereas the change in the upper part is not very different from that in a collectivized landscape in Eastern Europe (although done within democratic political systems), the lower part shows a landscape that still contains many relics and structures from the past. In such cases, it is much more difficult to make a systematic distinction between traditional and modern landscapes. In fact, there are almost no landscapes without any continuity with the past. Even in the landscape of collectivization, field patterns may have disappeared, but village structures and road patterns may have changed only to a small degree.

Consequently, it has to be stated that the term ‘traditional landscape’ is dangerous in its suggestion of a dichotomy of traditional versus modern landscapes [5], in which the idea of a millennia-long slow development stands against perception of a very fast modern transformation, especially with the recent introduction of renewable energy development [14,15,16,17], with some bad examples (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A bad example of renewable energy setting against a cultural heritage with valuable natural surroundings, Prónay-Patay Castle, Acsa-Újlak, Hungary, 2017. Photo: Csaba Centeri.

This contrast is often loaded with values, as the old landscape is described (not without reason, although also some ‘traditional landscapes’ were in fact rather uniform) as ecologically rich and as aesthetically attractive, but also (less justified) as stable and as the result of a long and gradual development. It is the landscape shown on 19th century topographical maps that is the single most important source of knowledge about the premodern landscape. These maps are often idealized and act as references for future plans, but they only show one phase in a long history that has known gradual change as well as rupture and sometimes catastrophe. Many landscapes that are nowadays cherished and are seen as markers of local and regional identities, are the result of processes of agrarian specialization that were in turn related to commercialization and globalization (e.g., World Heritage wine landscapes Bourgogne, Champagne (both in France), or Tokaj in Hungary). It is not often realized that even a number of medieval landscapes were highly influenced by towns. Regions in Flanders (Belgium) that are now seen as traditional agrarian landscapes in fact took shape in a semi-urban environment [18]. The same paper also showed that the history of rural landscapes, even in remote areas, is not only related to local circumstances. During the early 12th century, immigrants from Flanders were responsible for settlements and reclamations in south-west Wales; water engineers from The Netherlands conducted land reclamations in Germany, Poland, France, and other countries [19].

However, there is another problem. This value-laden concept of traditional landscapes usually leads to a negative judgment of the 20th century developments. The rich traditional landscape (from the past) is described in contrast with a poor modern landscape. Although it is difficult to deny that the 19th-century landscape was richer in landscape features and biodiversity than the present landscape, there are also other stories to tell. We could for example (and extremely simplifying) characterize the landscape around 1900 as an ecologically rich landscape with poor people, as against the present landscape of ecological paucity, but inhabited (at least in parts of Europe) by an affluent society.

Yet another point is that the landscapes that have changed relatively little during the last century are sometimes the result of remoteness, but in other cases are the result of long-time efforts by people and organizations to protect landscapes. In most cases, this protection involved not just a border and a label, but continuous management efforts. In landscapes under pressure, conservation is always a very active process, for which ‘management of change’ is a better term [20]. In addition to this, there are also protected landscapes with high environmental values that have in fact developed due to previous agricultural landscape abandonment. These new semi-natural landscapes are perceived as being more valuable than preceding traditional (?) cultural landscapes.

Last but not least, it has to be mentioned that a distinction between traditional and modern landscapes seems to offer only two possible futures for these traditional landscapes: protection or destruction [5]. Again, this is a useful concept for landscapes in which only a few structures still refer to their past. Such individual relics act as mnemonic devices for ways of life that have disappeared. The designation of more or less interrelated relics as ‘ecomusées’ in fact belongs to the same category. But for most landscapes, we have to see continuous change as a starting point. This has consequences for landscape research as well as for landscape management.

3. Research on Traditional Landscapes

Historical landscape research has a long tradition in a number of disciplines, such as geography [1], history [5], landscape archaeology, art history, landscape ecology, and landscape architecture. Recently, new research directions have developed, emphasizing aspects that have been neglected for a long time, such as the influence of individuals on formation of landscapes, the relation between societies and nature, and the long-term history of landscapes. A theme that has particularly gained popularity among archaeologists is the way societies coped with inherited landscape that was full of features created by descendants. The famous American geographer Donald Meinig already pointed out ‘… the powerful fact that life must be lived amidst that which was made before’ [21].

Some of these themes make clear that a simple chronological narrative is not always sufficient to show the complex development of landscapes [22]. A simple burial mound can have a long-term history of use and reuse, divided by periods of neglect or active disturbance as well as periods of active preservation. Concepts such as historical layers may provide tools to structure such histories (see for example [23]).

4. Protection and Management of Traditional Landscapes

Large differences exist in policies on traditional landscapes. On a European scale, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has for a long time stimulated large-scale mechanized agriculture that is difficult to combine with a landscape that is ecologically valuable and also functions as a space for living and recreation. Since the 1970s, an increasing number of measures are implemented to soften the effects of modern agriculture by stimulating organic farming or special products, although these activities do not automatically lead to different landscape management. One of the aims of the European scheme for Protected Designation of Origin is to preserve local economies and modes of production. Some authors thus assume that the mentioned European or similar schemes might be indirectly contributing to preservation of ‘traditional’ landscapes and strengthening the connections between local communities and their landscapes [24,25]. On the whole, the effects of the CAP on historic landscapes are mixed [26,27]. Whereas on the one hand the CAP has stimulated land abandonment in marginal areas, at the same time other measures aimed at continuation of farming in such areas. While some of the measures mentioned above help to preserve ‘traditional’ landscapes, the CAP as a whole still stimulates growing uniformity in landscapes and also has unwanted effects [28].

Most countries have taken measures to protect a number of agricultural landscapes by giving them the status of national or regional park or other designations. A latecomer in this type of scheme is Wallonia, that recently received its first protected landscape: the meander of the Ourthe in Neupré-Esneux, at the edge of Liege, is now a “Grand Site Paysager” [29]. It is still unclear what the consequences are. It seems to attract more visitors, but as yet this does not finance the management of this landscape.

5. PECSRL Session Contents: A Summary

Authors organized similar sessions at former PECSRL conferences, but the number of applications has never been so high; 25 applications were submitted. We can say that the topic of traditional landscapes is attracting big attention from European and also from non-European researchers. The 17 presentations accepted for the session dealt with traditional landscapes in eight countries, which face, have faced, or need to face transformations. The presentations provided lessons to learn, manifold. Interestingly, the 25 presentations that had been submitted to the session organizers have some obvious overlaps and can be clustered into groups according to the landscape type or the topic discussed:

- Hollerlandscapes that have been created in the past by water engineers from the Lowlands, mainly the Netherlands, present a very characteristic landscape, which can only be maintained by continuing the water regulation. Examples from the Altes Land in Northern Germany [30] and from the Vistula Delta in Poland [31] explained the chances which arise by the strong identification of the people with their land on the one hand, and on the cultural values which are to be maintained on the other. In both cases, it didn’t take long until locals, politics, and administration understood the meaning of this landscape heritage and that it might be something very valuable in order to create a sustainable living. The ”Programme for the Zulawy region-to 2030. Complex for Flood Protection” is actually implemented, taking into consideration many technical aspects of sustainable development. Local community activities aimed at the preservation of hydraulic systems as cultural heritage affect the continuation of culture in the modern period. Certainly, attempts to restore the region’s identity after many years of neglect are difficult and time-consuming. Nevertheless, processes that help to sustain the historic character of the landscape while allowing a sustainable economic development are accompanied by tourism activities and implementation of awareness in building construction measures.

- Italy: there were three presentations from Italy. Ferrario [32] reflected on the question “How a landscape becomes traditional?” Recalling the introduction of Jones and Stenseke [33], we all know how easily the term “traditional landscape” is used. More or less everybody has a meaning towards it. Starting with discussion of two processes, in which Ferrario herself has been involved (she wrote the candidacy of the first “historical rural landscape” and inspired the candidacy of the first agricultural “traditional practice” admitted to the Italian National Register), she examined what seems still an open question. How does the idea of traditional/historical landscape relate to landscape temporalities—social and multiple, but discordant? How should the consequences of institutional, social, and technical choices be dealt with? Attention was drawn to the recently established Italian “National Register of historical rural landscapes and traditional agricultural practices” and to the Italian debate on the subject, partly unknown abroad. This contribution was a perfect introduction to the next Italian presentation by Santoro et al. who spoke about rural Landscape and quality of life, lighting the Italian situation. In 2012, an observatory for rural landscapes was established in order to monitor landscape changes, develop a collaboration between landscape planning and rural development, define landscape quality objectives, and manage the National Register of Historical Rural Landscapes and Traditional Agricultural Practices. The National Register represents an alternative approach as compared with the system of parks and protected areas mostly aimed at nature conservation, as it is focusing on the dynamic conservation of agricultural landscapes representing examples of sustainable forms of agriculture and forestry that existed for some centuries in the same areas. Thanks to the collaboration established with the Observatory, in 2014 the National Statistical Agency recognized the role that rural landscapes play for the quality of life of the population and introduced the quality of rural landscapes in the national indicators of well-being of the population, including the conservation of historical landscapes among the indicators. The indicators developed for measuring the quality of rural landscapes consider abandonment and natural reforestation of previously cultivated areas as an indicator of degradation, reducing the quality of life, while other indicators consider the degree of conservation of the structure of the landscape mosaics as a measure of well-being. The third Italian presentation [34] called our attention on the importance of the multiple actors, whose conflicting interest might make the protection of the historical landscape difficult, especially with belonging to various authorities. This leads us to the next main cluster of issues connected with traditional landscapes, the problems of its management.

- Salpina already called our attention on the problem of management [34], especially if the background is different: a consortium of producers [35], a national park and a ‘dispersed governance’ requires a tremendously different approach. It is a good lesson and a message for future management on how to start approaching the tasks of heritage conservation. A similar case study called the management of a cultural and historical landscape paradoxical, as being a vine-producing region at the same time. The paradox background is based on the fact that it is a World Heritage Site and also a territory of priority development and a priority of touristic development. How can a traditional landscape be managed to keep its assets while we expect it to be a kind of economic development center [36]? Based on the present situation in a considerable part of Europe, authors of [26] questioned the management possibility of landscapes that were formed by farming, while farming is disappearing. The management of these areas, especially with low tourist activities raises numerous questions, e.g., about choosing the type of activities that they should host, formulating the guidelines, handling the diversity, etc. The introductory presentation of Renes [37] included the major conclusion regarding management. Traditional landscapes are often thought of as having a stable rural past, while most of them are the results of developments and many are younger than is often thought. Many ‘traditional landscapes’ are the result of historic specialization processes and, therefore, are a result of former stages in globalization rather than of strictly local developments [38]. To summarize the above said, the challenge, then, is to manage traditional cultural landscapes so that they remain in use, without losing their importance for landscape diversity, cultural heritage, and their particular regional identity.

- The final cluster includes presentations where the most exciting questions were raised about changes, transformations, transitions, re-emergencies, and challenges that traditional landscapes are facing. The very introduction of the whole session [37] already started with the statement that traditional landscapes themselves are the challenges for the future. That is due to the fact that specializations are subject to modernization, which often means that traditional landscapes lose many characteristics [39] and that part of the landscape diversity and biodiversity is lost. We can conclude that change is not always favorable, at least not with the speed of the present development, nor with the speed of the present change. We sometimes lose connection between landscape, tradition, and identity [40]. Traditional landscapes are often (re)created, (re)presented, transformed, (re)interpreted, and (re)invented to meet the needs, values, ideas, and identities of their present inhabitants [41] and sometimes, to be honest, to serve the needs of visitors for economic benefits [42]. The researches done at national borderlines [40,41] can lead us to the conclusion that there are specific approaches routing in different cultures, and that the culturally determined thinking is highly influenced by traditions and might result in formation of a different landscape character in the same geographical region. Last but not least, we can conclude that deep analyses of maps and literature might uncover differences between the perception of a present landscape and what it really is. Recent resurgence of a particular traditional landscape can often be linked to the willingness to increase tourism significance of a certain historical site situated in a traditional landscape which is perceived by people as an instance of the former landscape that is closest to their hearts [42].

6. Conclusion: The Future of Traditional Landscapes

For traditional landscapes to become part of not only the European past, but also of its future, systems of sustainable management that accept landscape change as an inherent part of its character should be developed [43,44]. We would emphasize four points:

- Since it cannot be desirable to create museum landscapes in which farmers cannot live off their own work, visions of landscape history are needed that are not only based on a description [45] of a static ‘traditional’ situation, but on more complex narratives. The concept of landscape as palimpsest [46] can be helpful, as it refers to the long-term development of landscapes and to significant inertia within material landscape structures [47]. Awareness of the long-term histories of landscapes is not just scientifically interesting, it also changes our perspective on their future planning, management, and protection. Processes of globalization, urbanization, and agricultural improvement that are changing our environment have done so for centuries or millennia. Only from such a dynamic vision, concepts for the future can be developed that go beyond a simple choice between conservation and transformation.

- For the sustainable management of landscapes, the involvement of experts and politicians is no longer enough; there has to be an involvement of the wider public [32]. Locals want the landscape to be used: a living, ongoing cultural landscape. Whereas the tourist business likes to present historic towns and countryside as places where ‘time stood still’, most locals despise the idea of freezing their environment: they want to develop it and improve it to meet their present needs, and to protect and maintain those parts and characteristics of local environment that are worth it. Thus, they also often obstruct change where it disrupts the notion of continuity, particularly when it is large scale and coming from outside. Many locals want an environment that reflects the heritage of their community and also their socioeconomic preferences. Landscape is an integrating concept and should be used as a basis for discussion. In that way, public participation could be a step towards dynamic landscape management.

- The landscape must keep functioning, socioeconomically and ecologically. Large-scale mechanized agriculture is difficult to combine with a landscape that is ecologically valuable and also functions as a space for living and recreation. Most fitting are types of agriculture in which farmers work is not too intensive and they have additional income from recreation or from special products. This last aspect means, for example, organic farming or special/traditional products, but also agri-kindergartens, social care on farms, or agri-tourism, although these activities do not automatically lead to different landscape management. Measures such as the European scheme for Protected Designation of Origin at least indirectly contribute to keeping a number of very specific landscapes alive. Again, preserving the continuity from the past and learning how to utilize remnants of past activities for present purposes can be relevant for the future. The present period, in which agriculture (and society as a whole) is dependent on fossil fuels may prove to be only an interlude in the long history of mankind. We may have to go back in time to take up and continue prefossil improvements in food supply. That is not necessarily the horror that the chemical industries predict, as many old agricultural practices could be remarkably productive. In 2010, the archaeologist Erika Guttman-Bond wrote on this topic an article ‘How archaeology can save the planet’ (a book with the same title will appear later this year) [48].

- The last keywords are planning and design. Planners can act as intermediaries between development and preservation. Moreover, they can add quality to plans, aesthetically, but also by giving isolated historical landscape features new contexts and meanings.

Author Contributions

H.R. developed the main text. Afterwards, the co-authors worked in equal parts in several rounds together with the main author on the article, which is why they are listed here in alphabetical order.

Funding

The Czech Science Foundation grant no. P410/12/G113 supported the organization of the “S10. Traditional Landscapes: Exploring the Connections between Landscape, Identity, Heritage, and Change” session at the 2018 PECSRL conference in France.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Baker, A.R.H. Historical geography and the study of the European rural landscape. Geogr. Annaler. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 1988, 70, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmfrid, S. The Permanent Conference and the study of the rural landscape: A retrospect. In European Rural Landscapes: Persistence and Change in a Globalising Environment; Palang, H., Sooväli, H., Antrop, M., Setten, G., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sluis, T. Europe: The Paradox of Landscape Change. A Case-Study Based Contribution to the Understanding of Landscape Transitions. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson, U. The Rural Landscapes of Europe: How Man Has Shaped European Nature; The Swedish Research Council Formas: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Renes, H. Historic Landscapes Without History? A Reconsideration of the Concept of Traditional Landscapes. Rural Landsc. Soc. Environ. Hist. 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobsbawm, E.; Ranger, T. (Eds.) The Invention of Tradition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. The concept of traditional landscapes as a base for landscape evaluation and planning. The example of Flanders Region. Landsc. Urb. Plan. 1997, 38, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Landscape change: Plan or chaos? Landsc. Urb. Plan. 1998, 41, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipský, Z. The changing face of the Czech rural landscape. Landsc. Urb. Plan. 1995, 31, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bičík, I.; Kupková, L.; Jeleček, L.; Kabrda, J.; Štych, P.; Janoušek, Z.; Winklerová, J. Land Use Changes in the Czech. Republic 1845–2010; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, M.; Hildebrandt, S.; Röhner, S.; Tilk, C.; Schwarz-von Raumer, H.-G.; Roser, F.; Borsdorff, M. Landscape as an Area as Perceived by People: Empirically-based Nationwide Modelling of Scenic Landscape Quality in Germany. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, L.; Buchecker, M.; Garcia, X.; Gottwald, S.; Müller, S.; Præstholm, S.; Stahl Olafsson, A. Integrating sense of place in planning and management of multifunctional river landscapes: Experiences from five European case studies. Sustain. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irngartinger, C.; Degenhardt, B.; Buchecker, M. Naherholungsverhalten und -ansprüche in Schweizer Agglomerationen. Ergebnisse einer Befragung der St. Galler Bevölkerung 2009; Eidg. Forschungsanstalt WSL: Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 2010; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Frantál, B.; Kunc, J. Wind turbines in tourism landscapes: Czech experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinát, S.; Navrátil, J.; Dvořák, P.; Van der Horst, D.; Klusáček, P.; Kunc, J.; Frantál, B. Where AD plants wildly grow: The spatio-temporal diffusion of agricultural biogas production in the Czech Republic. Renew. Energy 2016, 95, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Eiter, S.; Röhner, S.; Kruse, A.; Schmitz, S.; Frantál, B.; Centeri, C.; Frolova, M.; Buchecher, M.; Stober, D.; et al. (Eds.) Renewable Energy and Landscape Quality; Jovis Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018; 295p, ISBN 9783868595246. [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, M.; Centeri, C.; Ferrario, V.; Martinat, S.; Herrero-Luque, D. Adaptation to sustainable energy transition in Europe and its impact on landscape quality: Comparative study (Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Spain). In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugghe, G.; Van Eetvelde, V.; De Clercq, W. Cultural identity in the historic settlement landscapes of Flanders. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, A.; Paulowitz, B. Holler Colonies and the Altes Land: A Vivid Example of the Importance of European Intangible and Tangible Heritage. In Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage; 2019; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Purmer, M. The Geul Valley: A Traditional landscape in Transition, from a Farmers’ Arcadia to a Multifunctional Landscape. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- Meinig, D.W. The beholding eye: Ten versions of the same scene. In The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays; Meinig, D.W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Skowronek, E.; Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Tucki, A.; Stasiak, A. The role of local products in preserving traditional farming landscapes in the context of developing peripheral regions—The Lubelskie Voivodeship, Eastern Poland. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 182–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kolen, J.; Renes, J.; Hermans, R. (Eds.) Biographies of Landscape; Geographical, Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on the Production and Transmission of Landscapes; AUP: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vollet, D.; Candau, J.; Ginelli, L.; Michelin, Y.; Ménadier, L.; Rapey, H.; Dobremez, L. Landscape elements: Can they help in selling ‘protected designation of origin’ products? Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.; Plieninger, T. The potential of landscape labelling approaches for integrated landscape management in Europe. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 904–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, M.; Espinosa, M.; Gomez y Paloma, S. The Influence of the Common Agricultural Policy on Agricultural Landscapes; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2012; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahos, G.; Louloudis, L. Landscape and agriculture under the reformed Common Agricultural Policy in Greece: Constructing a typology of interventions. Geogr. Tidssk. Danish J. Geogr. 2011, 111, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penko Seidl, N.; Golobič, M. The effects of EU policies on preserving cultural landscape in the Alps. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, S.; Bruckmann, L. The management of cultural heritage landscapes as new challenge in Wallonia. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, A.; Paulowitz, B. The Hollerroute—Landscape Awareness as a Driving Factor in Regional Development, Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 183–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rubczak, A. Waterways as a factor in the transformation of the cultural landscape of the Vistula delta. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 87–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario, V. How does an agricultural landscape become traditional? Coming back to landscape temporality. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Stenseke, M. (Eds.) The European Landscape Convention: Challenges of Participation; Landscape Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Salpina, D. How to manage agricultural landscape as a heritage category? Insights from three historic agricultural landscapes in Italy (Soave, Cinque Terre and Amalfi). In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 135–136. [Google Scholar]

- Slámová, M.; Kruse, A. Strengthening the relationship between the farmer and the countryside. challenges of the Erasmus Ka2+ Project FEAL. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 184–185. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, K. Cultural, historical and vineyard landscape. Paradoxes? Case study: Tokaj Wine Region, Hungary. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Renes, H. Traditional landscapes as challenges for the future. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- Renes, J. Landscapes of agricultural specialization: A forgotten theme in historic landscape research and management. Hung. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2010, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sarlöv Herlin, I. Intangible benefits from grazing farm animals to landscape and quality of life. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kučera, Z. Changing connections between landscape, tradition and identity: The case of the Czech borderlands. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Konkolyné-Gyúró, É. Perception of landscape and its changes in a French-German trans-boundary area. In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; pp. 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, A.; Servain, S. The national estate of Chambord (France): Traditional landscapes or a political willingness to make re-emerge the past? In Permanent, European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape PECSRL 2018: European Landscapes for Quality of Life? Proceedings of the 28th Session of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape; PECSRL: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2018; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Le Dû-Blayo, L. How do we accommodate new land uses in traditional landscapes? Remanence of landscapes, resilience of areas, resistance of people. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slámová, M.; Beláček, B.; Jančura, P.; Prídavková, Z. Relevance of the historical catchwork system for sustainability of the traditional agricultural landscape in the Southern Podpolanie region. Agric. Agric. Sci. Proc. 2015, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, M.D.; Roth, M.; Buchecker, M. Conclusion: Criteria for describing the cultural dimension of agricultural landscapes. In European Culture expressed in Agricultural Landscapes; Pungetti, G., Kruse, A., Eds.; Palombi & Partner: Rome, Italy, 2010; pp. 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gojda, M. Archeologie Krajiny—Vývoj Archetypů Kulturní Krajiny; Academia: Praha, Czech Republic, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dodgshon, R.A. Society in Time and Space, A Geographical Perspective on Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann-Bond, E. Sustainability out of the past: How archaeology can save the planet. World Archaeol. 2010, 42, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).