Abstract

The political shift in Lebanon since the 1990s towards market-led development has encouraged the incremental appropriation of public spaces and state lands, and their conversion into gated, monitored enclaves that serve a privileged few. The process disregards the role of the urban public realm and undermines its potential as an inclusive space and enabling platform for urban governance. This article advocates a participatory approach to urban development, one that engages local stakeholders, institutions, and the public at large as active partners working towards sustainable urban futures. We draw on a case study in Saida, Lebanon, to illustrate participatory planning methods and demonstrate the role of landscape architects in enabling community-led development that is place responsive and sensitive to local narratives of heritage and identity. The project’s participatory methodology and landscape architecture’s expansive framing, the paper argues, democratizes the planning process and contributes to urban governance that empowers local authorities and local stakeholders in the face of privatization and market-led development.

Keywords:

participatory; governance; landscape; public realm; urban environment; local authority; Lebanon; Mediterranean 1. Introduction

1.1. Why Participatory Planning?

The gradual change in postwar Western democracies from the ‘traditional’, top-heavy conception of government, the ‘direct provider’ of welfare and services, towards a bottom-up, decentralized model reflects widespread belief that the ideal place for democratic training and debate is at the local level [1,2,3]. The latter is argued on the premise that the system of values and norms are more homogeneous at the urban, i.e., city, level than at the national one. By the early 1990s, elected local governments became an important facet of what came to be known as ‘local governance’. The political shift from “government to governance”1, favored process rather than institutions [4] (p. 5), making governance2 a priority in the discourse of democracy in cities.

A ‘participatory’ approach is directly associated with the political shift towards decentralization and the changing discourse on governance. Participatory methods, whether applied to governance, development, or democracy, aim to provide opportunities for the participation of individuals and institutions in processes that generate ideas and action for inclusive development and social change. Capacity-building is a key to ‘participatory governance’ and accountability is its central lever [7,8]. Accountability develops from three key lines of action [9]: to provide enabling spaces; to initiate bonding and bridging communication; and to strategize power-shifting, which, in many ways, is the outcome of the former two. Together, these strategies provide ways to engage communities and marginalized factions of society and empower them to influence local and central decision-making.

1.2. The Political Landscape of Lebanon

Lebanon is a small country of 4.5 million inhabitants in the Eastern Mediterranean. Mountains and sea account for an exceptionally picturesque and heterogeneous physical setting. Landscape heterogeneity is matched by the religious and political diversity of Lebanese society. A parliamentary democratic system set in place following independence from the French Mandate in 1943 ensures that government offices are distributed proportionately to represent the religious diversity. The Lebanese civil war (1975–1990) interrupted elections, undermined the prevailing quasi-democratic system, encouraged informal economies and laissez-faire development and the accelerated growth of towns and cities along Lebanon’s 225 km long Mediterranean coast, where the largest cities are located, including the capital city, Beirut.

At the same time, highly-centralized government institutions, another colonial legacy that continued to dominate postcolonial decades, results in weak local authorities in terms of decision-making and in responding to local needs. Apart from the National Physical Master Plan for the Lebanese Territories [10], city master plans that date to the 1960s and broad planning legislation, urban growth, indeed, territorial development, remain unregulated. Urban/regional infrastructure network is undertaken by the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) and the Ministry of Public Works with a minimum cooperation from local authorities, who lack financial and technical resources.

Since the 1990s, state politics have shifted gradually away from democratic rule towards neoliberal politics leading to serious repercussions. On the one hand, market-led development has meant excessive privatization by global corporations and realty developers that is changing the spatial morphology and undermining the urban ecology. Market-led development, it is argued, animates the national economy, a priority considering the political instability in Lebanon and the region. On the other hand, the role of the state, as the body upholding public rights and protecting the public realm, has been marginalized. As a result, the public realm is increasingly suffering, as state land is appropriated and transformed into exclusive development that privileges a handful at the expense of the urban majority [11]. Ecologically and spatially, too, the city has changed as open, soft landscapes are converted into artificial ones, river courses channelized and waterfronts are privatized and built-up. Spatially excluded, socially marginalized, their memories and traditional practices sidestepped, the political majority lose their voice in as a supposedly democratic government system fails. As a tool for collective decision-making and socially just development, participatory planning is one alternative to address failures of governance in Lebanese cities. Accepting participatory planning as the starting point, this article aims to explore this approach and whether landscape architects can play a role in participatory planning that can contribute to urban governance.

1.3. A Landscape Framing of a Participatory Approach

The evolving relationship between people and the environment they inhabit is at the heart of the idea of landscape and, equally, the complex relationship that embraces the tangible, physical setting, and intangibles, such as associated cultural values and social practices. A landscape framing spatializes and contextualizes abstract discourses and anchors them in a specific place and culture. It follows that landscape is increasingly applied to frame the discourse on human rights [12], address custom, law, and the body politic [13], and tackle governance and democracy [14]. Ecology and politics are similarly influences that impact the fast-evolving discourse on the landscape, bringing together modes of being, acting, and thinking that reflect the past to project into the future [15].

The landscape’s evolving epistemology, in turn, expands design practice and outlook spatially while sensitizing architects, landscape architects and urban designers to local ecologies, cultural practices, and local community needs and aspirations. Humanized and culture-invested landscapes then serve as a dynamic and enabling medium for socio-economic betterment and political empowerment [11]. In theory, therefore, a landscape design framing of the public realm can encourage “inclusive and democratic, long-term and integrated, multi-scalar and territorial” development, which are prerequisites for good governance [6]. In the following sections we outline the project methodology, the logistics of a landscape framing and, thereafter, discuss the applications and findings. We conclude with a discussion of participatory practices emerging from the project reviewing their impact on urban governance in Saida.

2. Materials and Methods: Saida Case Study

2.1. Case Study Method in Landscape Architecture

Case studies in research are gaining ground and credibility as a research method that can be applied across a range of disciplines (medicine, engineering, planning) as a method that utilizes real-life examples as a source for expanding knowledge and generating scientific discourse [16]. In a report commissioned by the Landscape Architecture Foundation, Francis concludes that “a case study method is a highly appropriate and valuable approach” [17] (p. 5). Considering that landscape architecture is a new profession, i.e., in comparison to architecture and city planning, and that the body of research is somewhat limited, the case study method can “answer big questions at the intersection of policy and design” and prove “useful in participatory planning, for culturally sensitive design and for studies trying to refine or test emerging concepts and ideas” [17] (p. 13). This is especially the case in the Middle East, where the meaning of the word landscape is limited to natural scenery and the professional scope similarly narrowed to beautification [18]. It follows that the use of case studies, whether in graduate research or in professional discourse, expands the prevailing understanding of the word and contributes to better understanding of the professional scope.

In this article, we draw on the case study of a project in Saida (Phoenician Sidon), Lebanon, to elaborate the project participatory planning methodology. The article focuses on the “Landscape, Environment, and Ecology” component of the project and explores a landscape framing of the public realm, i.e., state-owned lands, such as river corridors and the seafront, to test the efficacy of landscape architecture in contributing to urban governance.

2.2. Saida City Profile

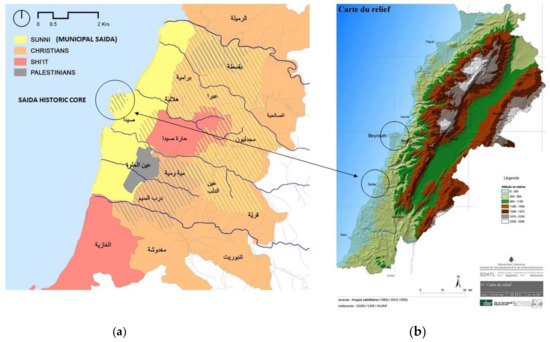

Forty kilometers south of the capital Beirut, the city of Saida3 is the third largest city in Lebanon (Figure 1). Saida’s natural rocky harbor is one of oldest harbors in the Levant, having served as the main port city for Damascus and the region up to the early twentieth century. Municipal Saida occupies a coastal plain, 1–1.5 km wide and 7 km long, delimited from the east by gentle foothills and punctuated with a series of watercourses. The Awali and Sayniq Rivers, respectively, define the northern and southern boundaries of the municipality. In between are smaller streams, seasonal watercourses, that form natural, ecological corridors and historic, cultural caravan routes connecting the desert to the Mediterranean Sea. Rivers and streams are alive in the collective memory of the city’s inhabitants, a source of life, irrigating the city orchards, structuring residential neighborhoods, and shaping the urban morphology. Saida’s urban footprint covers 62% of the municipal area, 7.50 km2; the remaining 28% is costal agriculture. Of the total estimated population, 149,600 inhabitants, 80,000 are Lebanese, while the rest are Palestinians, and Saida houses the largest Palestinian refugee camp in the Middle East. The religious diversity is typical to Lebanon, which includes a majority of Sunni Muslims, 79%, Shiite Muslims, 10%, and 7% Catholic and Maronite Christians.

Figure 1.

(a) Saida, religious composition (source: authors) and (b) the location south of the capital of Lebanon, Beirut [10].

Saida was designated as a ‘gate city’ to Southern Lebanon [10], implying that it serves as an administrative and service portal, a position it held prior to the Lebanese Civil War. Historically, Saida’s economy was maritime (commerce, fishing) and agricultural (citrus cultivation). Today both are under threat. Declining agriculture profitability has encouraged realty speculation targeting agricultural lands. Additionally, Saida’s harbor is the smallest commercial port in Lebanon today and no longer viable economically. Cultural tourism is proving a new economic resource, considering the relatively intact medieval city with its abundance of ancient archaeological, Byzantine, and Ottoman sites and buildings. The significance of Saida, however, lies as well in the services it provides and its proximity to the capital, which accounts for the rapid urban growth and expansion at the expense of quality living the city was known for.

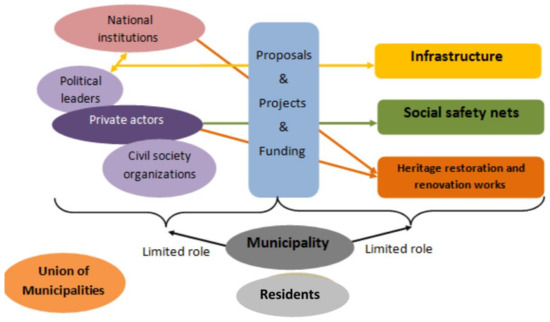

The Saida municipality, an elected body, plays a limited role in the highly-centralized development planning in Lebanon. Administrative, financial, and technical limitations restrict the municipal role in Lebanese cities, reducing local governance to nominal approval and support of projects assigned and funded by the central government. Moreover, project selection follows a political process of consensus decision-making, “a ‘political game’ that often reaches a complex equilibrium that distributes public spending across Lebanon” (Figure 2) [19].

Figure 2.

Schematic representing the current process of decision-making in the Saida municipality. Project proposals, their funding and implementation is highly centralized, controlled by national institutions and leadership [19].

Residents are not effectively involved in the decision-making process seeing that the municipality, itself, which is the only elected body in the city, plays a limited role in this process. Nor are decisions made with a regional development vision. The latter undermines collaboration of the municipalities that form the Saida and Zahrani Union of Municipalities (UoM) and does not allow for the UoM to address service and infrastructure projects that cross municipal boundaries and necessitate cooperation of municipalities in the union, for example, solid waste management and sewage. Sewage is dumped into rivers, watercourses and state land, causing a major environmental problem in the Saida municipality that receives the discharge downstream. The absence of a national institutional and legal framework that supports, enables, and empowers municipalities, and the prevalence of generic engineering solutions that continue to be planned with disregard to local context, have dire repercussions to environmental health and human health alike [19].

2.3. MedCities City Development Strategy

MedCities is an initiative created in Barcelona, in November 1991, aspiring to “strengthen decentralized actions” through technical assistance to promote awareness of urban environmental problems and use them as a platform for action that empowers municipalities in developing countries to manage urban environmental issues [20].

Members from the Saida Municipal Council applied and were considered, and eventually accepted, by MedCities for funding. The outcome is the Saida Urban Sustainable Development Strategy (USUDS) project that was launched in the fall of 2012 with funding secured from the European Council. MedCities’ participatory, bottom-up methodological approach was a key to “reinforce the role, competences and resources (institutional, financial and technical) of local administrations in the adoption and implementation of sustainable local development policies” and equally, to “develop citizens’ awareness and involvement in the sustainable development of their towns and cities” [20]. MedCities methodology views strategic planning as a continuous management process rather than a fixed plan, i.e., a master plan. It follows that social and economic agents, neighborhood communities, unions, entrepreneurs, and local authorities become active players in the urban vision and future development. Active involvement of all stakeholders in decision-making and the role of local authorities taking charge of financing and execution is seen by MedCities as the surest path to strengthen urban governance. In the Saida USUDS, the Saida municipality was the ‘client’ signing the MedCities contract, entrusted with follow-up and delivery of project final output.

3. Application of a Participatory Approach

The MedCities participatory approach was applied through all phases of the Saida USUSD4. Additionally, it is the broad scope of the MedCities methodology that is reflected in the interdisciplinary project tracks to which lead and supporting national expert are assigned to form the project team. The participatory approach in Saida was realized by identifying key actors whose participation was central to the analysis and formulation of a shared city vision and city development strategy. Key actors were stratified into three overlapping levels. The first embraced the local authority, realized through the “Municipal Steering Committee” composed of twelve members that represent the administrative, economic, and social sectors5. The second level for participation was achieved by forming working groups for each of the five disciplinary tracks6. The third level of participation, targeting the general public, was achieved through three town hall meetings, one at the launching of the project, the second halfway through the project7, and a third at the end of the project. Participants on all three levels worked with the project consulting team collectively and independently.

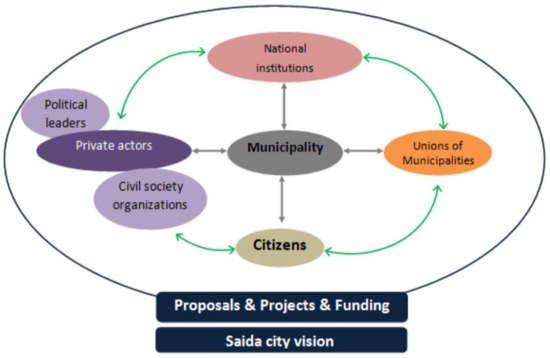

Working groups were key to brainstorming the collective vision for the city and also representative members of the municipal council that were present in most meetings. Participation of the municipality staff was intensified in the last three phases of the project for budgeting and technical feedback. At the same time, political endorsement of, and support for, the Saida USUDS project was given by the Hariri Foundation and Deputy Bahia Hariri, both based in Saida. Endorsement, a necessary dimension for the success of development projects in Lebanon, is also problematic because of the danger that it can overshadow and dominate, rather than enforce, local governance. The multi-disciplinary team of national consultants8, appointed by MedCities in consultation with the Saida municipality, was another cornerstone ensuring the success of the Saida USUDS project. The following excerpt outlines the team position and guiding vision that aims to expand the institutional base and decision-making process in the city (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

The decision-making process cycle that needs to be instituted to strengthen urban governance [19].

“The team adopted an institutional perspective in which participatory democracy plays an essential role. Participatory democracy is a process of deliberation based on effective cooperation between the various institutions in the city, via the creation of institutional networks that exchange information, knowledge, and experience between the municipality and the socio-economic actors in the city.”[19]

The Saida USUDS project vision, articulated at the end of Phase 3, prioritizes good governance as a foundation for quality living. The vision is supported by four overlapping, mutually-inclusive pillars: adequate health and social protection; a diversified economy; healthy environment; and protected urban heritage, both natural and cultural. The position of the project team confirms that urban governance in Saida can only proceed from accepting religious and cultural diversity and a democratic participatory approach that includes all the city’s residents, Lebanese and Palestinian. The vision and strategies proposed can and should enable the city to lobby for change in the laws and regulations to allow a semblance of independent decision-making. It is “only through an institutional approach for governance can such a decision of the city be implemented” [19].

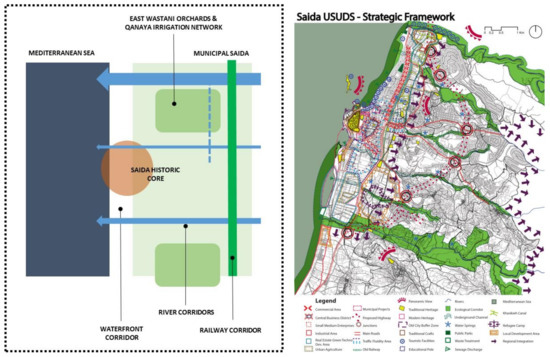

The “Landscape, Environment, and Ecology” component of the Saida USUDS was developed by applying a holistic ecological landscape design methodology [22] to take stock of existing conditions, identify environmental problems, locate natural resources, and assess their potential and limitations for sustainable urban development. The methodology enabled a landscape framing of the environment and natural resources that embraced rivers and seasonal watercourses, the Mediterranean seafront, and the abandoned railway corridor, reaffirming that they are state-owned lands, part of the ‘public realm’, that should be preserved from privatization and informal encroachment. The environmental health and ecological integrity of these features was a key to the landscape analysis. A holistic landscape framing as such spatializes the environmental challenge, by considering the limitations and potentials of these morphological, water-related features rather than focusing solutions to them as environmental ‘problems’. A holistic landscape framing is also multifunctional in accepting that these features are, at once, an environmental resource, an ecosystem and urban landscape heritage that is culturally meaningful and integral to the collective memory of the people of Saida. The landscape vision integrates rivers, the seafront and other components identified as forming a ‘Green-Blue Network’ that protects them as landscape heritage, environmental resource, ecological corridors and amenity spaces9 (Figure 4). A landscape framing of the ‘public realm’, as such, prioritizes environmental health and urban connectivity. Additionally, because the Green-Blue Network is spatially expansive, covering the entire municipal area, it is accessible to all the inhabitants of Saida and the neighboring municipalities, a public realm that is socially inclusive rather than being exclusive to privileged factions of the society [22]. Just as significantly, the proposed network draws on historically living cultural practices that use the rivers, coast, and railway tracks for social gathering, thus reaffirming the urban distinctiveness of Saida and countering the homogenizing approach of market-led development10.

Figure 4.

Saida USUDS landscape concept and consolidated structure plan embracing all five project disciplinary tracks [23].

4. Discussion

Revisiting the premise posed at the outset of this article: does an expansive landscape design framing contribute to urban governance? If yes, why and how is its contribution different from, and complementary to, the participatory approach of the Saida USUDS project? Drawing on the participatory and transdisciplinary approach of the MedCities as applied in Saida, we posit that the “Landscape, Environment, and Ecology” track was the most enduring of the five project tracks. This statement is based on the number of community initiatives inspired by the landscape framing during the course of the USUDS project (2012–2014) and those enabled by the project strategic vision after the project ended. Additionally, landscape strategies proposed by the project were the only USUDS strategies to receive technical support for development and more recently being considered for funding for implementation after the project ended.

Responding to the second question, ‘why was the landscape component more enduring’, is more difficult. The reasons lie partly in the landscape’s expansive framing of the city and its potential to integrate nature and people, environmental health, and heritage by contextualizing development strategies. The pace- and culture-responsive landscape strategies proposed were meaningful to the urban inhabitants at a time when ‘urban infrastructure’ projects required considerable technical and financial resources to implement and the ‘Heritage’ track was, for the most part, confined to the historic core. ‘Economic betterment’ and ‘Governance’ strategies, on the other hand, are long-term and not easily communicated to the public. In contrast, the Green-Blue Network served as the spatial embodiment of urban nature that is valued by all11. Similarly, the focus on rivers, streams and the coast resonate with the local discourse on Saida’s outstanding natural setting and are integral to the shared memory of the city inhabitants, poor and rich, Lebanese and Palestinian.

On a practical level, the discursive elasticity of the landscape, enabled the landscape consultant to engage local players, individuals, and institutions, who were asked to contribute in various ways to the Green-Blue Network. Contributions by three of these players is herein discussed. First, ‘Shajar w Bashar’ is an NGO founded in 2008 in Saida committed to socially-disadvantaged youth and women. Shajar w Bashar programs aim to build capacity through training in decision-making skills that enhance social responsibilities and help improve living conditions. The NGO was identified as a key actor, and was approached to work on the abandoned railway corridor seeing as it had already engaged youth in a clean-up campaign for parts of the railway corridor. The USUDS team connected ‘Shajar w Bashar’ with Saida Municipality, experts and NGOs12 that worked on similar projects to help build a strategy and portfolio for the project. The multifaceted framing of the abandoned railway corridor, and the fact that it was part of a city-wide strategic development, enabled Shajar w Bashar to secure funding for the project from PACE/USAID. The project “Mamar13 2013/2014” advocated and lobbied with local associations and youth from all religions, Palestinian and Lebanese, to claim the abandoned railway as a car-free, amenity space14 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

‘Shajar w Bashar’ initiative building on the landscape concept of the USUDS landscape proposal for reviving the abandoned railway corridor as a city-scale, inclusive public space.

Another offshoot from the initiative was by Lil Madina15, a group of young, professional civil activists. As with the previous example, a member of the Lil Madina group was commissioned by the lead author to research and document the agriculture heritage of Saida and the historic irrigation network16, ‘Qanat Al-Khaskiyeh’ or ‘Qanaya’, that dates to Roman times. The network includes cultural practices to ration water quantities from the Awali River equitably. Saida orchards are famed for the quality of their produce and valued by all as integral to the collective identity. Yet, the orchards and the historic Qanaya were threatened by market-led development targeting these lands for exclusive housing development. Incorporating the orchards and Qanaya network, rivers, and streams within the USUDS landscape concept, revived public interest and awareness of their historic and cultural value and with the forward-looking landscape strategy, their potential in a sustainable vision for future development of Saida. Lil Madina has taken up these sentiments and succeeded during, and after, the USUDS to mobilize public and local organizations to protect these valued landscapes as a natural and cultural heritage of Saida (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

‘Lil Madina’ website profiling the historic Qanaya and Saida orchards as a collective landscape heritage of Saida.

With the Saida USUDS City Development Plan formally approved, Lil Madina focused on two very important initiatives. The first, East Wastani Development, aimed to combat realty development destined to displace orchards and agricultural lands north of the city. The project has strong political backing and is favored by the municipality. From 2012, Lil Madina conducted workshops17 to find sustainable and community-inclusive alternatives to the corporate, generic development proposed. The outcome was promising as the political parties involved conceded and commissioned a master plan that followed the USUDS vision and guidelines18.

The second initiative, a direct offshoot from the Saida USUDS, aimed to revive the ecological integrity of the Qamli stream, another component of the Green-Blue Network. Lil Madina mobilized neighborhood residents, technical expertise, and secured funding to clean the river and conceptualize it as an amenity corridor. Accepting that river corridors bridge administrative boundaries and that cleaning the watercourse should necessarily involve other municipalities upstream from Saida, Lil Madina worked in close collaboration with adjoining municipalities, members of the Saida-Zahrani Union of Municipalities, securing funding to clean the Qamli by remapping the cadastral boundaries of the corridor, noting building encroachment, and repairing sewage discharge network [25].

The repercussions of the landscape strategies proposed by the Saida USUDS was not limited to enabling and empowering local communities, but was equally empowering of the Saida municipality. In less than a year after completion of the project, the Municipality of Metropolitan Barcelona proposed a series of workshops with the Saida municipality to develop detailed designs and cost estimates for components of the Blue-Green Network. The designs were completed in 2015, and the municipality proceeded to solicit funds for implementation. With a clear vision and development strategy secure, the Saida municipality was among the Lebanese cities and towns shortlisted in 2017–2018 by the French Development Agency (AFD) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) for potential funding of municipal projects. Once more, components of the Green-Blue Network attracted potential funding, seeing that they combined environmental health, social benefits, and quality living. Thus, for the first time, the Saida municipality was taking the initiative independently from the central government, backed by a collective vision for the future of Saida conceived by the city inhabitants. These small steps have come to dispel the prevailing perception in Lebanon that reduces the role of municipal authorities to paving streets and collecting solid waste. Empowering local authorities and changing their modus operandi, however, requires more than one project. Rather it should be seen as a process with successes and failures. There is a need to build competencies and technical skills to realize the shift towards empowered and visionary local governance.

The discourse emerging from the Saida project is also significant in that it reaffirms the claim made earlier of the usefulness of the case study research method in landscape architecture. Not only does the case study allow for the sharing of participatory tools, but it provides innovative problem-solving skills for planning the public realm in Lebanon as well, for example, the Green-Blue Network. Case studies are also an effective method for teaching by example. Incrementally, case studies can contribute to “a body of criticism and critical theory” and can “disseminate the effectiveness of landscape architecture outside the profession” [17] (p. 9).

5. Conclusions

Decentralization is redefining the relationship between citizens and the state towards stronger, democratic local and regional governance. The speed and trajectories of state decentralization, however, varies from one place to another, which is especially true when comparing governance in countries of the global north with those of the global south. The challenges of state decentralization in oppressive political systems and/or those lacking political accountability is immense [26,27]. Lebanon is one case in point. Accepting that participatory planning has the potential to ease the way to state decentralization and to address political struggles and power relations, as demonstrated by the Saida case study, the process is slow and the transformation, at best, long term. Nevertheless, enabling local authorities and empowering the public to voice and claim their right to the city, is one way to social justice and democratic societies [28].

The Saida case study was also an opportunity to demonstrate the expansive landscape design approach through participatory, contextualized, and multifunctional framing. The latter is especially significant in the absence of planning and integrative policies in Lebanon. Urban infrastructure, social welfare, and environmental health are compartmentalized in planning policies, the responsibility of different ministries, respectively, the Ministry of Public Works and Transportation, the Ministry of Work and Social Affairs, and the Ministry of Environment. There is often little coordination of the overlapping responsibilities of those ministries. The holistic landscape framing, as such, can provide a platform for the collaboration of the various state bodies and agencies through projects that are led by local authorities.

Author Contributions

Jala Makhzoumi was commissioned by Saida Municipality as national consultant for the “Landscape, Environment and Ecology”; Salwa al-Sabbagh contributed to the Saida USUDS data collection, field work and participated in meetings as part of her the Master of Urban Design thesis, American University of Beirut.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Oxhorn, P. Civil society without a State? Transnational civil society and the challenge of democracy in a globalizing world. World Future 2007, 63, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxhorn, P.; Tulchin, J.; Selee, A. Decentralization, Democratic Governance, and Civil Society in Comparative Perspective. Africa, Asia and Latin America; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Prachett, L.; Wilson, D. Local Government under Siege. In Local Democracy and Local Government; Prachett, L., Wilson, D., Eds.; Macmillan Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1996; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pierre, J. Public-Private Partnerships and Urban Governance: Introduction. In Decentralization, Democratic Governance, and Civil Society in Comparative Perspective Africa, Asia and Latin America; Oxhorn, P., Tulchin, J., Selee, A., Eds.; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker, G. Public-Private Partnerships and Urban Governance. In Urban Governance; Pierre, J., Ed.; Partnerships, Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1998; pp. 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- UNHabitat, Governance. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/governance/ (accessed on 27 September 2017).

- McEwan, C. Bringing government to the people: Women, local governance and community participation in South Africa. Geoforum 2003, 34, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. Evaluating participatory development: Tyranny, power and (re)politicization. Third World Q. 2004, 25, 557–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Participation Research Cluster. Participatory Methods. Available online: http://www.participatorymethods.org/ (accessed on 27 September 2017).

- Council for Development and Reconstruction, National Physical Master Plan of the Lebanese Territories. 2005. Available online: http://www.cdr.gov.lb/study/sdatl/sdatle.htm (accessed on 1 January 2018).

- Makhzoumi, J. The greening discourse: Ecological landscape design and city regions in the Mashreq. In Reconceptualizing Boundaries: Urban Design in the Arab World; Saliba, R., Ed.; Ashgate: London, UK, 2015; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Egoz, S.; Makhzoumi, J.; Pungetti, G. The Right to Landscape: Contesting Landscape and Human Rights; Ashgate: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Olwig, K. Landscape, Nature and the Body Politic; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Egoz, S.; Jorgensen, K.; Ruggeri, D. Defining Landscape Democracy; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, E.; Waterman, T. Landscape and Agency: Critical Essays; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gillham, B. Case Study Research Methods; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. A Case Study Method for Landscape Architecture; Landscape Architecture Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; Available online: https://lafoundation.org/myos/my-uploads/2010/08/19/casestudymethod.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Makhzoumi, J. Landscape in the Middle East: An inquiry. Landsc. Res. 2002, 27, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaban, J.; Srour, I.; Hamadeh, K. Saida USUDS Strategic Diagnosis: Institutional and Legal Framework. 2014. Available online: http://www.medcities.org/documents/22116/135803/5.+Saida_Diagnosis+_+Institutional+and+Legal++Framework.pdf/b62f3b3a-53aa-41d8-bdbf-4fccbe2d4114 (accessed on 2 January 2018).

- MedCities. Available online: http://www.medcities.org/ (accessed on 31 December 2017).

- MedCities Saida CDS. Available online: http://www.medcities.org/web/saida (accessed on 2 January 2018).

- Makhzoumi, J.; Pungetti, G. Ecological Design and Planning: The Mediterranean Context; E. & F. N. Spon, Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Makhzoumi, J.; Al-Sabbagh, S. Saida USUDS Strategic Diagnosis: Green Open Spaces. 2014. Available online: http://www.medcities.org/documents/22116/135803/2.+Saida_Diagnosis_Green-Open.pdf/4bbf1534-8be5-46b1-b2ea-1b30f477d27d (accessed on 2 January 2018).

- Al-Sabbagh, S. Rethinking Planning Tools through the Ecological Landscape Design Approach: Saida Case Study. Master’s Thesis, Urban Design, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon, February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lil, M. Qamleh River in Greater Saida: Its Disappearance and Efforts to Revive it; Creative Commons: Saida, Lebanon, 2017. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- De Soto, H. The Other Path, The Economic Answer to Terrorism; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Soto, H. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Makhzoumi, J. Landscape architecture and the discourse on democracy in the Middle East. In Defining Landscape Democracy; Egoz, S., Jorgensen, K., Ruggeri, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | While ‘government’ refers to “the formal institutional structure and location of authoritative decision-making in the modern state”, ‘governance’ signifies new processes of governing and new methods by which society is governed, and a focus on the interdependence of governmental and non-governmental organizations working together [5] (p. 34). |

| 2 | UN-Habitat defines ‘governance’ as the many ways that institutions (i.e., local authorities) and individuals “organize the day-to-day management of a city, and the processes used for effectively realizing the short-term and long-term agenda of a city’s development” [6]. |

| 3 | With a total population of 149,600, Saida is the third largest city in Lebanon; 80,000 of Saida inhabitants are Lebanese; the rest, Palestinians. |

| 4 | The six project phases include: (1) Preparation and Launching; (2) Diagnosis and Participatory Analysis; (3) Formulation of a Shared Vision; (4) Strategy Formulation to Translate Vision into Concrete Actions; (5) Preparation of Action Plans and Estimated Budget; and (6) Implementation, Monitoring and CDS Evaluation [21]. |

| 5 | The members include: the deputy mayor, four municipal council members, vice president for the Saida Traders Association, Said Welfare Society, Director of the Sea Mosque Organization, executive director from the Hariri Foundation, General Manager of the Saida Chamber of Commerce, and representative from the Lebanese University. |

| 6 | Working Group members include: 13 participants for the Urban Infrastructure track; eight for the Landscape, Environment and Ecology track; 16 for Cultural and Natural Heritage; 12 for the Employment in Traditional Industries and Trades; 14 participants for the Institutional and Legal Framework track; and 10 for the Local Economic Development. |

| 7 | The second Town Hall Meeting was cancelled because of armed confrontation between political parties on the day, which escalated to engulf the city for the following weeks. |

| 8 | Project disciplinary tracks and their respective national expert(s): “Local Economic Development”, “Social Structure and Urban Governance”, Jad Chaaban, IIina Srour and Kanj Hamade; “Cultural Heritage” and team leader, Howayda AI Hanthy; “Urban Infrastructure”, Omar Abdulaziz Hallaj and Giulia Guadagnoli; “Landscape Environment and Ecology”, Jala Makhzoumi and Salwa Al-Sabbagh. |

| 9 | For a detailed description of the Saida Green-Blue Network refer to Saida USUDS Green Open Spaces [23]. |

| 10 | Al-Sabbagh builds on the Saida USUDS to explore the potential of an ecological landscape planning methodology to propose context-responsive and culture-inclusive planning tools to counter market-led, homogenizing, and exclusive development [24]. |

| 11 | Saida USUDS working group meetings. |

| 12 | ‘Train/Train’, https://www.facebook.com/traintrainlebanon/ a group aiming to reclaim the railway network in Lebanon as a public realm. The extensive railway network in Lebanon was abandoned in the 1970s during the civil war. The corridors and stations are state-owned, allowing for temporary amenity use. Another group was ‘Dictaphone’, civil activists with the aim of reclaiming the public realm; see http://www.dictaphonegroup.com/both accessed (1 January 2018). |

| 13 | In Arabic ‘Mamar’ implies passage, which has spatial dimensions and non-spatial connotations of a process that addresses issues of governance for Saida youth. |

| 14 | The activities organized for the project by ‘Shajar w Bashar’ include: meetings for civic empowerment, 2013; meetings with political stakeholders; launching the project, 28 March 2014; petition signing; ‘Walk/Cycle the Railway’, 12 April 2014; closing ceremony 26 June 2014. See https://www.peaceinsight.org/conflicts/lebanon/peacebuilding-organisations/shajar-w-bashar/ and https://arab.org/directory/shajar-w-bashar/. |

| 15 | Arabic ‘Lil Madina’ translates ‘for the city’, founded in 2013 by residents of Saida, mainly architects and urban designers. Their collective agenda, modus operandi, and outreach differs considerably from ‘Shajar w Bashar’. See https://lilmadinainitiative.wordpress.com/ (1 February 2018). |

| 16 | This article’s author, Sabbagh, participated in data gathering and field survey for the Qanaya study and was an active partner in many of the Lil Madina initiatives. |

| 17 | Workshops co-organized by Lilmadina and Al-Sabbagh include: “Development of East Wastani”, February 2014; Public and focused talks, i.e., Makassed Talk, May 2015; ‘Towards Improving the Land-Pooling and Subdivision Tool Roundtable in collaboration with Issam Fares Institute, 19 December 2015 co-organized with Sabbagh; “Developing Al-Qamleh Valley” April 2015. |

| 18 | The Lebanese urban planning framework applied by corporate land developers includes a set of regulatory (e.g., master plans, building law) and operational tools (e.g., land pooling tool) that is top-heavy, ignoring the specificity of place and local community. For a detailed discussion of the land pooling corporate application in the East Wastani project versus ecological guidelines for planning see Salwa Sabbagh, 2015 [24]. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).