Navigating Trade–Offs and Synergies of Cultivated Land Values in China’s Poverty–Alleviated Area During Rural Transformation: A Case Study of the Liupan Mountain Area in Northwestern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

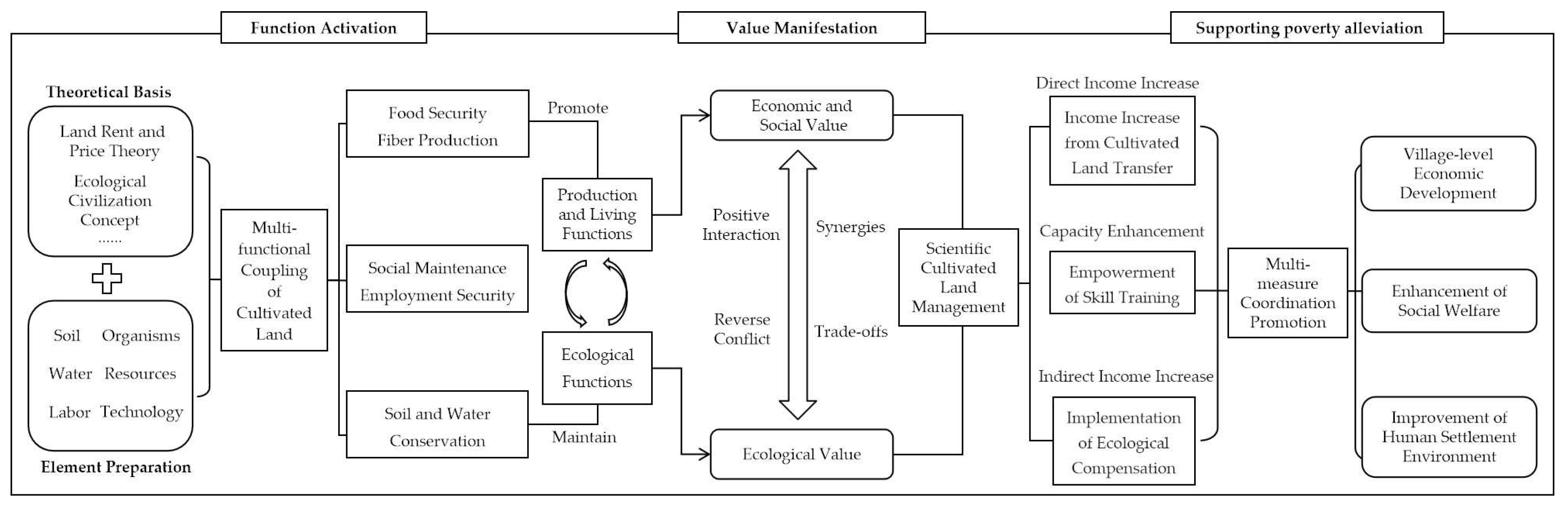

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Establishment of an Evaluation System for the Value of Cultivated Land Resources

2.4.2. Calculation of the Economic Value of Cultivated Land Resources

2.4.3. Calculation of the Ecological Value of Cultivated Land Resources

2.4.4. Trade–Off/Synergy Analysis of Cultivable Land Resource Value Based on the PPF

2.4.5. Identification of Trade–Off/Synergistic Zoning for Cultivated Land Resource Value Based on GIS Visualization Technology

3. Results

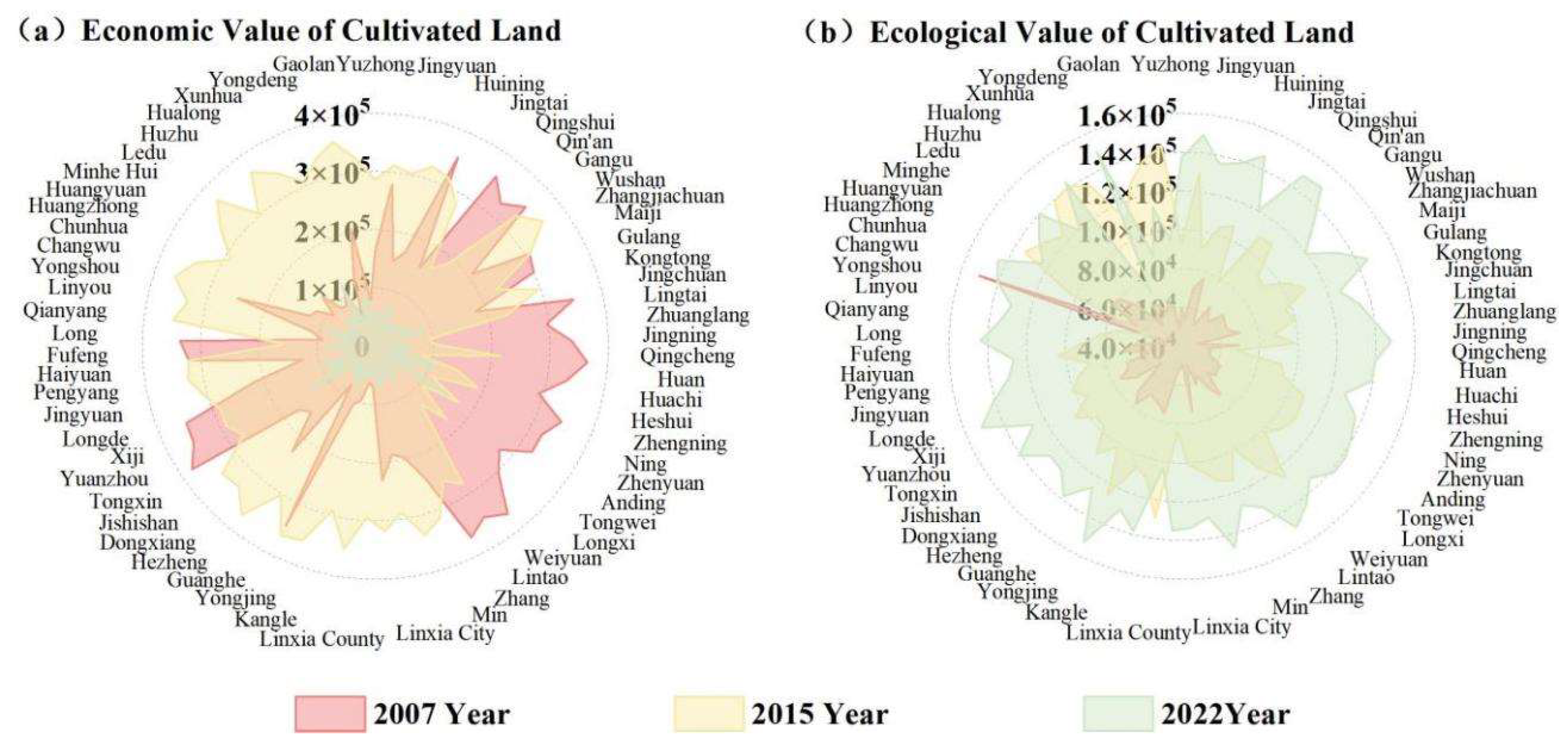

3.1. Characteristics of Spatiotemporal Evolution in the Values of Cultivated Land Resources

3.1.1. Temporal Evolution Characteristics of the Values of Cultivated Land Resources

3.1.2. Spatial Evolution Characteristics of Cultivated Land Resource Value

3.2. Spearman Correlation Analysis

3.3. Spatio–Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Regional Identification of Trade–Offs/Synergistic Relationships in the Value of Cultivated Land Resources

3.3.1. Temporal Characteristics of Trade–Offs/Synergistic Relationships in the Values of Cultivated Land Resources

3.3.2. Spatial Characteristics and Regional Identification of Trade–Offs/Synergistic Relationships in the Values of Cultivated Land Resources

4. Discussion

4.1. Value Reconstruction and Collaborative Mechanisms of Cultivated Land Resources in the Liupan Mountain Area Amid Rural Transformation and Development

4.2. Revelation for Cultivated Land Utilization Management in Poverty–Alleviated Area Based on the Values of Cultivated Land Resources and Their Trade–Offs/Synergistic Relationships

4.3. Limitations and Research Perspective

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPF | Production Possibility Frontier |

| SEEA | System of Environmental–Economic Accounting |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| CLVTS | Cultivated Land Value Trade–off and Synergy |

References

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, J.X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Yang, X.J. Poverty vulnerability measurement and its impact factors of farmers: Based on the empirical analysis in Qinba Mountains. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.S.; Lan, A.J.; Fan, Z.M.; Feng, B.C.; Xiao, K.S. Spatiotemporal evolution trends and topographic gradient effects of cultivated land transformation in river basins of karst mountainous areas in Guizhou Province. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 32, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.G.; Han, X.; Long, H.L.; Zhou, B.B.; Zang, Y.Z.; Wang, J.X.; Fan, Y.T. Research progress and prospects on supply and demand matching of farmland multifunctions. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 1351–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, Z.B.; Luo, R.S.; Hong, Y.Y.; Wang, S.J.; Ma, X.; Bao, Q. Balancing poverty alleviation and ecosystem vulnerability reduction: Implication from China’s targeted interventions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.L.; Huo, Y.Q. Reevaluating Cultivated Land in China: Method and Case Studies. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2006, 61, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. Development of the SEEA 2003 and its implementation. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inacio, M.; Baltranaite, E.; Valenca Pinto, L.M.; Akhtarieva, M.; Barcelo, D.; Pereira, P.A. Systematic literature review on the implementation of the system of environmental–economic accounting–ecosystem accounting in forests, Cities and Marine Areas. Ecosyst. Serv. 2025, 74, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Agra, R.; Zolyomi, A.; Keith, H.; Nicholson, E.; de Lamo, X.; Portela, R.; Obst, C.; Alam, M.; Honzák, M.; et al. Using the system of environmental–economic accounting ecosystem accounting for policy: A case study on forest ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 152, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardon, M.J.; Le, T.H.L.; Martinez–Lagunes, R.; Pule, O.B.; Schenau, S.; May, S.; Grafton, R.Q. Accounting for water: A global review and indicators of best practice for improved water governance. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 227, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.S.; Stewart, S.B.; Scheufele, G.; Evans, D.; Liu, N.; Pascoe, S.; Roxburgh, S.H.; Schmidt, R.K.; Vardon, M. Accounting for ecosystem services using extended supply and use tables: A case study of the Murray–darling basin, Australia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2025, 74, 101741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, Z.Q.; Zou, L.; Zou, L.L.; Zhang, H.W. Exploring the eco–efficiency of cultivated land utilization and its influencing factors in China’s Yangtze River Economic Belt, 2001–2018. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 112939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.S.; Wang, W.; Xue, Y.X.; Li, B.Y.; Jin, S.Z. Simulation of multi–scenario land use change and its impact on escosystem services in China based on PLUS–InVEST model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 9577–9593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.B.; Wu, B.; Wang, P.C.; Lu, R.C.; Jiang, K. The trade–off/synergy relationship between values of cultivated land resources assets: A case study of Guangxi, Southwestern China. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 1344–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wan, C.Y.; Xu, G.L.; Chen, L.T.; Yang, C. Exploring the relationship and influencing factors of cultivated land multifunction in China from the perspective of trade–off/synergy. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 149, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Guo, Q.X.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y. Tradeoffs/synergies analysis of “Production–Living–Ecological” functions in Shanxi province. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Dong, P.; Lu, Y.Q.; Ge, D.Z. Cropland ecosystem service trade–offs/synergies and threshold efferts: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta region. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 7836–7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Shi, X.Q.; Li, Y.H.; Li, Y.M.; Huang, P. Spatio–temporal pattern and functional zoning of ecosystem services in the karst mountainous areas of southeastern Yunnan. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 736–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.B.; Pan, Y.C.; Tang, L.N.; Tu, M.G. Spatial differentiation characteristics and trade–off/synergy relationships of rural multi–functions based on multi–source data. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 2036–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.R.; Jia, Y.L.; Wang, H.J.; Wang, Z. Analysis of trade–off and synergy effects of ecosystem services in Hebei province from the perspective of ecological function area. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 2833–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cademus, R.; Escobedo, F.J.; McLaughlin, D.; Abd–Elrahman, A. Analyzing trade–Offs, synergies, and drivers among timber production, carbon sequestration, and water yield in Pinus elliotii Forests in southeastern USA. Forests 2014, 5, 1409–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Zhu, W.B.; Zhu, L.Q.; LI, Y.H. Multi–scale analysis of trade–off/synergistic effects of forest ecosystem services in the Funiu Mountain Region, China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 32, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.M.; Dong, B.Y.; Li, S.N.; Lin, Y.; Shahtahmassebi, A.; You, S.X.; Zhang, J.; Gan, M.Y.; Yang, L.X.; Wang, K. Identifying the trade–offs and synergies among land use functions and their influencing factors from a geospatial perspective: A case study in Hangzhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.H.; Sun, X.; Huang, Q.X.; Qiao, J.M.; Fang, G.J.; Ren, Y.H.; Wang, C.R.; Sun, J.; Yang, P. Optimizing the landscape in grain production and identifying trade–offs between ecological benefits based on production possibility frontiers: A case study of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.T.; Wen, L.Y.; Li, K.Q.; Kong, X.B.; Zhang, X.L. Environmental risk and burden inequality intensified by changes in cultivated land patterns. Resources. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 225, 108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.L.; Zhou, K.C.; Sun, Z.X. Relationship among trade–offs, synergies, and driving factors of multifunctional farmland values in Hunan province. J. Green Sci. Technol. 2025, 27, 198–205+10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Liu, Z.S.; Sun, L.; Li, X.; Wang, W.Y. Study on multi–fuction evaluation and consolidation zoning of cultivated land in jiutai district. J. Northeast Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 55, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.M.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.M.; Hang, Y.H.; Gao, M.; Lu, X.; Yang, Y.J.; Meng, X.F.; Zhu, L.Q. Assessment of the cultivated land quality in the black soil region of northeast China based on the field scale. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.P.; Cao, Y.J.; Guo, H.M.; Mi, Y.S.; Xi, X.W.; Liu, Y.Z.; Yu, B.P. Multidimensional accounting of ecological value of cultivated land resources in Anhui province and its spatiotemporal heterogeneity effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 47, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.Q.; Huang, S.L. Evaluation of cultivated land ecosystem service value in the black soil region of northeast China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.S.; Liu, M.F.; Wan, Y.F.; Song, Z.J. Evolution and coordination of cultivated land multifunctionality in Poyang lake ecological economic zone. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.X.; Wang, J.H.; Han, H.B.; Niu, J.Q.; Chen, X.Y. Modeling of spatial pattern and influencing factors of cultivated land quality in Henan province based on spatial big data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Song, C.Q.; Ye, S.J.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, L.N.; Li, C. Estimate provincial–level effectiveness of the arable land requisition–compensation balance policy in mainland China in the last 20 years. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.J.; Guo, J.Y. Coupling coordination and obstacle factors of cultivated land system resilience and new urbanization. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1554797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.N.; Qu, L.L. Multifunctional rural development in China: Pattern, process and mechanism. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, R.Y. The relationship between livelihood capital, multi–functional value perception of cultivated land and farmers’ willingness to land transfer: A regional observations in the period of poverty alleviation and rural revitalization. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lu, J.; Liu, H.; Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S. A Study on Accounting for Suburban Agricultural Land Rent in a Chinese Context Based on Agricultural Ecological Value and Landscape Value. Land 2023, 12, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Liu, D.D. Does urbanization reduce the multi–functional value of cultivated land? Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 38; Carrasco, L.R.; Webb, E.L.; Symes, W.S.; Koh, L.P.; Sodhi, N.S. Global economic trade-offs between wild nature and tropical agriculture. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2001657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, K.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Cao, H. Adaptive Management of Cultivated Land Use Zoning Based on Land Types Classification: A Case Study of Henan Province. Land 2022, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Xie, B.P.; Tian, L.M.; Chen, Y.; Pei, T.T. Spatiotemporal coupling relationship between multifunctional land use and multidimensional relative poverty in the Gansu section of Liupanshan. Arid. Land Geogr. 2025, 48, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.D.; Zhen, L.; Lu, C.X.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, C. Expert knowledge–based valuation method of ecosystem services in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2008, 23, 911–919. [Google Scholar]

- Guang, H.J.; Ming, Z.W.; Yan, B.Q.; Ding, Y.Z.; Wen, Q.M. Towards cultivated land multifunction assessment in China: Applying the “influencing factors-functions-products-demands” integrated framewor. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Deng, L.; Chen, Y.; Wei, F. Research on the multidimensional valuation and spatial differentiation of cultivated land resources in the Pearl River–Xijiang Economic Belt, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, J.; Nan, L. Connotation and calculation methods for the cultivated land resources values—A case of Shanxi Province. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2010, 24, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.D.; Xiao, Y.; Zhen, L.; Lu, C.X. Study on ecosystem services value of food production in China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2005, 13, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.X.; Luo, X.F.; Liu, Z.Z.; Tang, L. Spatial–temporal variation and influencing factors of farmland ecological value in theYangtze River Economic Belt. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2024, 32, 505−517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Y.Z.; Hu, W.Y. exploring the scale effects of trade–offs and synergies of multifunctional cultivated land—Evidence from Wuhan metropolitan area. J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 13, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Hu, Y.N.; Hu, T.; Zhou, R.; Ma, Q.; Fang, X.N. Urbanization intensified the Trade–Off between food security and water quality security in the Yangtze river delta. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Xiao, P.N.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, Q. The Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of Cultivated Land Multifunction and Its Trade–Off/Synergy Relationship in the Two Lake Plains. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.Z.; Sun, T.S.; Li, W.W. Trade–offs and synergies of farmland ecosystem services in Loess Plateau: A case study of Longdon Region, Northwest China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.N.; Zhao, X.Q.; Pu, J.W.; Miao, P.P.; Wang, Q.; Tan, K. Optimize and control territorial spatial functional areas to improve the ecological stability and total environment in karst areas of southwest China. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Shi, L.N.; Wen, Q. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Obstacle Degree of Rural Resilience Coupling Coordination in Liupan Mountain Poverty Alleviation Area. J. Southwest Univ. 2025, 47, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Jin, X.R.; Feng, Z.; Chen, T.Q.; Wang, C.X.; Feng, D.; Lv, J. Relationship of ecosystem services in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region based on the production possibility frontier. Land 2021, 10, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Name | Data Content | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical data | Crop Yield and Planting Area | Statistical Yearbook, Rural Yearbook, Handbook of Key Economic Indicators, Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development, and government websites |

| Average price of crops, cash income per mu of agricultural products | National Agricultural Product Cost and Revenue Data Compilation | |

| Terrain data | 500 m DEM, terrain type | The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (https://www.gebco.net (accessed on 6 May 2024)) |

| Vector data | Provincial and county administrative boundaries | National Platform for Common GeoSpatial Information Services (https://www.tianditu.gov.cn (accessed on 17 June 2024)) |

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Cultivated Land | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaanxi | Gansu | Qinghai | Ningxia | ||

| Adjustment Services | Gas Regulation | 0.3672 | 0.3024 | 0.2880 | 0.4392 |

| Climate Regulation | 0.4947 | 0.4074 | 0.3880 | 0.5917 | |

| Hydrological Regulation | 0.3927 | 0.3234 | 0.3080 | 0.4697 | |

| Waste disposal | 0.7089 | 0.5838 | 0.5560 | 0.8479 | |

| Support Services Cultural Services | Soil Conservation | 0.7497 | 0.6174 | 0.5880 | 0.8967 |

| Biodiversity Conservation | 0.5202 | 0.4284 | 0.4080 | 0.6222 | |

| Provide esthetic landscapes | 0.0867 | 0.0714 | 0.0680 | 0.1037 | |

| Total | 3.3201 | 2.7342 | 2.6040 | 3.9711 | |

| Year | 2007 | 2015 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Value—Ecological Value | 0.319 * | 0.496 ** | 0.646 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shi, L.; Wang, C. Navigating Trade–Offs and Synergies of Cultivated Land Values in China’s Poverty–Alleviated Area During Rural Transformation: A Case Study of the Liupan Mountain Area in Northwestern China. Land 2026, 15, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010019

Shi L, Wang C. Navigating Trade–Offs and Synergies of Cultivated Land Values in China’s Poverty–Alleviated Area During Rural Transformation: A Case Study of the Liupan Mountain Area in Northwestern China. Land. 2026; 15(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Linna, and Chenyang Wang. 2026. "Navigating Trade–Offs and Synergies of Cultivated Land Values in China’s Poverty–Alleviated Area During Rural Transformation: A Case Study of the Liupan Mountain Area in Northwestern China" Land 15, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010019

APA StyleShi, L., & Wang, C. (2026). Navigating Trade–Offs and Synergies of Cultivated Land Values in China’s Poverty–Alleviated Area During Rural Transformation: A Case Study of the Liupan Mountain Area in Northwestern China. Land, 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010019