Abstract

Urban green spaces play a crucial role in mitigating the biodiversity loss caused by dense development and land-use transformation. This study explores the ecological and spatial potential of Fort Augustówka, a neglected military fortification in Warsaw, Poland, as a multifunctional green space that enhances local biodiversity. Through field surveys, vegetation assessments, SWOT analysis, and user profiling, we identified key ecological features and constraints of the site, located within a Vistula River riparian zone. This study employed phytosociological analysis (Braun–Blanquet method), spatial mapping (using AutoCAD and SketchUp), and stakeholder observations to assess the value of semi-natural habitats including ruderal vegetation, meadows, and aquatic zones, as well as urban tree stands and conventionally managed greenery. Our results show that semi-natural habitats, including meadows and reed beds, achieved higher ecological value scores than conventionally managed greenery, while invasive species significantly reduced biodiversity in several zones. Based on these findings, we propose a spatial revitalisation model grounded in native species restoration, ecological connectivity, and low-impact recreational design. This study highlights an innovative approach that integrates existing vegetation, historical structures, and human well-being, creating a design concept beneficial for residents and visitors alike. This work also demonstrates how post-military landscapes can support biodiversity in metropolitan areas and offers a transferable model for ecological urban design rooted in place-based analysis. The findings contribute to broader discussions on nature-based solutions and urban rewilding in post-socialist urban contexts.

1. Introduction

Urban areas, though often associated with biodiversity loss and ecological fragmentation, are increasingly recognised as potential reservoirs of species diversity and as critical components of global conservation strategies [1,2,3]. Post-industrial and post-military landscapes, in particular, present unique opportunities for urban biodiversity restoration due to their transitional character, historical land-use legacies, and often semi-natural habitats [4,5]. In the context of Central European cities, which have experienced rapid urbanisation and socio-economic transformations in the past decades, the adaptive reuse of such sites offers significant ecological and social benefits [6]. Recent studies highlight that different types of urban habitats provide complementary ecosystem services. Semi-natural areas, such as meadows and reed beds, are significant for supporting pollinators and maintaining habitat heterogeneity, while tree arrays contribute strongly to carbon storage and microclimate regulation [7,8,9]. Recognising this complementarity is essential for assessing the ecological potential of post-military landscapes.

Warsaw, Poland, exemplifies the challenges and opportunities in integrating biodiversity considerations into urban redevelopment. Riparian zones along the Vistula River host remnants of native floodplain forests (Ficario-Ulmetum minoris Knapp 1942 EM. J.Mat. 1976), meadows, and wetlands, which provide essential ecosystem services and act as biodiversity corridors within the urban matrix [10]. However, these habitats are increasingly threatened by invasive species, urban sprawl, and infrastructure expansion [11,12].

Most parts of the former Warsaw Fortress have been significantly transformed as a result of a lack of demand for the primary, military function and urban sprawl. Based on orthophotomaps [13], it was possible to identify the current functions of preserved components of the Warsaw Fortress and their dominant type of greenery (*—domination of intensively managed greenery; **—25–50% coverage of spontaneous vegetation; ***—over 50% coverage of spontaneous vegetation; ****—coverage of spontaneous vegetation close to 100%):

- Residential buildings with accompanying commercial services: Cze*, Śliwickiego*, and Służew**;

- Commercial services and industry: Okęcie**, Mokotów**, Wawrzyszew***, Blizne***, Zbarż***, and Służewiec***;

- Sports and cultural services with accompanying public greenery: Cytadela Warszawska*, Legionów*, Traugutta**, and Czerniaków**;

- Public green spaces: Bema*; Rakowiec*, Żeromskiego*, Włochy**, Bielany***, and Augustówka***;

- Allotment gardens: Radiowo***;

- No assigned function (abandoned): Chrzanów****, Szczęśliwice****, and Odolany****.

In most sites, leaving spontaneous vegetation from succession is not used as a purposeful method of establishing greenery. The intentional use of spontaneous dendroflora (understood as leaving scrub and semi-natural tree stands) as fully-fledged greenery is very rare, limited practically to areas with challenging terrain (e.g., Cytadela Warszawska; Fort Traugutta) or small fragments of larger sites (e.g., the private park in Fort Służew, not open to the public). Spontaneous herbaceous vegetation is used more often, for example, in a public park created in Fort Włochy.

A similar phenomenon can be observed in other Polish cities, for example, Poznań. The most important part of the old fortress, which now serves as a public green space, is the Cytadela Park, located on the site of Fort Winiary [14]. However, in this park (and other, smaller public green spaces in Poznań, created before WWII on land previously used by the military), the main role is played by intensively maintained greenery—ornamental plantings of trees, shrubs, perennials, and frequently mowed lawns. Some of the forts in Poznań have been adapted as museums (Forts VI and VII) [15], with the fort greenery being preserved and partially restored, but without making it useful for recreation. Few post-military objects of Poznań have also been abandoned [15] and consequently left to secondary vegetation succession.

Comparable initiatives in other European cities illustrate both the potential and limitations of integrating former military or brownfield areas into the urban ecological network. In Berlin, many parts of the former Tempelhof Airport [16] and military training grounds have been transformed into multifunctional public spaces, yet biodiversity management often prioritises recreational functions over ecological continuity [17]. In Prague, the adaptive reuse of brownfields has been integrated into the metropolitan green belt strategy, but challenges remain in securing long-term biodiversity monitoring and management [18]. Vienna has advanced ecological design principles in projects such as the Aspern Seestadt redevelopment, where blue–green infrastructure has been systematically embedded into planning [19]. By situating the Warsaw case within this broader context, our study highlights its uniqueness in systematically evaluating the current ecological state of a post-military landscape, which remains underexplored in post-socialist urban planning discourse.

Historical fortifications in urban areas, including Fort Augustówka in Warsaw, reflect a specific category of post-military landscapes. Once strategically significant, many such sites have become neglected spaces undergoing spontaneous ecological succession [20,21]. Recent trends in urban ecology highlight the potential of these sites to serve as biodiversity hotspots and multifunctional green infrastructure when appropriately managed and integrated into urban planning [22]. Despite these insights, systematic methodologies for assessing the ecological value and design potential of post-military landscapes remain scarce, particularly in post-socialist urban contexts [21]. This study aims to embed the case of Fort Augustówka within broader discussions on nature-based solutions and ecological urbanism. This research focuses on assessing the ecological value and spatial characteristics of Fort Augustówka as a multifunctional urban green space, while exploring the role of semi-natural habitats, such as ruderal vegetation, meadows, and aquatic zones, in supporting urban biodiversity. Furthermore, this study seeks to develop a methodological framework for integrating ecological connectivity and biodiversity conservation into urban design processes, particularly within post-military landscapes. To address these aims, the following research hypotheses have been formulated: (1) post-military landscapes, exemplified by Fort Augustówka, can support urban biodiversity (by representing various types of vegetation) when managed through ecological design approaches; (2) semi-natural habitats within urban fortifications have higher ecological values compared to conventionally (intensively) managed greenery, and their ecological contributions can be as significant as those of urban tree stands; and (3) integrating native plant species and ecological corridors into the design of post-military sites enhances both ecological connectivity and the recreational value of such areas. The aim of this study is not to trace the long-term transformations of flora, but to document and evaluate the current ecological state of Fort Augustówka as a representative post-military landscape within Warsaw. By combining vegetation surveys with an assessment of tree stands and ecological valuation of identified plant communities, we provide a comprehensive basis for understanding the site’s biodiversity potential and its possible integration into urban ecological planning. Assessments of tree stands and ecological valuations of identified plant communities, we provide a comprehensive basis for understanding the site’s biodiversity potential and its potential

This study intends to generate practical insights for urban ecological planning and the sustainable redevelopment of culturally and historically significant urban landscapes, contributing to contemporary strategies of biodiversity preservation and green infrastructure development in metropolitan areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Location

The 16.85-hectare study area is located in the eastern part of Warsaw’s Mokotów district (52°12′27″ N, 21°5′13″ E) and includes the area of Fort X, also known as Fort Augustówka, along with the surrounding ponds.

2.1.2. History

Fort X was built in 1883 as part of the outer ring of the Warsaw Fortress, during Russian rule. After the outbreak of World War II, Fort Augustówka was used as a defence site for the Polish resistance [23], and later by German occupation forces, during which it served as a training ground, according to Królikowski [24]. After World War II, the site was kept almost completely treeless; it was also removed from an orthophotomap prepared in 1987, which suggests that the site was used for military purposes. The current recreational development took place between 2001 and 2005 [13].

2.1.3. Function

Fort Augustówka currently has a partially park-like character thanks to the existing network of pedestrian and bicycle paths. There are also informal sports and recreation facilities, such as an obstacle course for cyclists and an outdoor shooting range, as well as fishing spots near the reservoirs. However, the area is neglected and deserted.

2.1.4. Formal and Legal Conditions

The ramparts and moat of Fort X are included in the municipal register of monuments of the capital city of Warsaw. However, they are not included in the register of monuments and do not have a registration card. The area is intended to serve as a park and recreation area.

2.1.5. Natural Conditions

The highest points are the tops of the fortification ramparts, reaching an average elevation of 94.0 m above sea level. The lowest points are the bottoms of the ponds and moats, measuring approximately 82.0 m above sea level. The ramparts constitute a significant local elevation point and serve as a dominant feature in the study area, dividing it into viewing areas. The average depth of the reservoirs in the study area is 2 m.

The soils in the study area are partly urban soils and, to a lesser extent, alluvial soils, characterised by a high degree of fertility. The area is also characterised by poor soil permeability [25]. A total of five reservoirs are located in the study area, one of which is artificial. The areas of the reservoirs, from largest to smallest, are as follows: 8544 m2, 643 m2, 423 m2, and 384 m2. The fifth reservoir is a fort moat in the eastern part of the study area, with an area of 2.16 ha. Surface waters cover a total area of approximately 3.16 ha, which constitutes nearly 19% of the total area of the study area. [26]. According to the classification by Okołowicz [27], the study area lies within the temperate warm transitional climate zone. Based on climate maps, the average annual temperature for 2019 was 10 °C, including 19 °C in July and 3 °C in January [28].

According to Matuszkiewicz’s [29] geobotanical regionalisation, the area is located in the Southern Masovian-Podlasie Region in the Łowicko-Warsaw District, in the Warsaw-Puławy Vistula Valley subdistrict. According to data from Matuszkiewicz’s [30] potential vegetation map, the study area is occupied by a community of typical ash-elm riverine forests (labelled as Ficario-Ulmetum typicum, an equivalent to ass. Ficario-Ulmetum minoris Knapp 1942 EM. J.Mat. 1976).

2.2. Methods

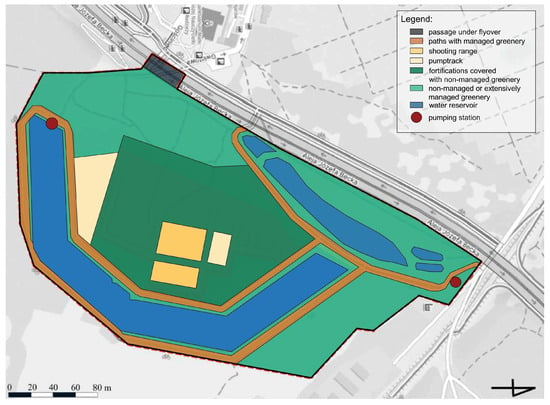

Identification of land use zones was crucial for conducting further analyses. Seven zones were distinguished: F—fortifications; N—non-managed or extensively managed greenery; P—paths with managed greenery; PF—passage under flyover; PT—pump track; S—shooting range; W—water reservoirs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forms of land use of Augustówka Fort.

2.2.1. Vegetation Characteristics

The field research (performed from March to August 2024), consisted of the tree stands and herbaceous vegetation inventory.

Plant species names were given according to Mirek et al. [31].

Field research was conducted during a single growing season, which is a standard and sufficient approach for identifying plant communities in Poland, adequate to the climate conditions of Central Europe (phenological changes of plant species) [32]. The methodological focus of this study is on documenting the present ecological condition rather than analysing temporal changes. Accordingly, our dataset integrates (i) phytosociological inventories of semi-natural habitats, (ii) structural and ecological assessment of urban tree stands, and (iii) an overall ecological valuation of the site. This integrated framework allows us to assess biodiversity potential and management needs, even without long-term monitoring.

During the inventory of the tree stands, the species occurring were identified and divided according to spatial form (solitary trees, small clumps, in-row plantings, medium groups, and big groups). The average height of each species was measured.

Phytosociological relevés were carried out using the Braun–Blanquet [33] method. Phytosociological relevés were taken to identify plant communities, named according to Matuszkiewicz [34].

During subsequent analyses, the tree canopy coverage was calculated, and specific parameters were assigned to individual species included in the tree stands: their status in the Polish flora [31,35] and the edibility of fruit and the suitability for pollinators.

2.2.2. Evaluation of Vegetation in Aspects of Ecological Values and Naturalness

The evaluation was conducted for each land use zone (F—fortifications; N—non-managed or extensively managed greenery; P—paths with managed greenery; PF—passage under flyover; PT—pump track; S—shooting range; W—water reservoirs). We propose our own method of evaluation, applicable to urban green areas [36,37]. This evaluation method helps to identify the most ecologically valuable areas within the assessed area (disclaimer: this method, unmodified, will work well only in areas without protected species and ecosystems; if protected species and ecosystems are present, parameters that include them should be added). It combines the ecological value of the tree stands (described below), the naturalness of the vegetation (point scale: 0—no vegetation; 1—cultivated and ruderal vegetation; 2—semi-natural vegetation; 3—natural vegetation), the presence or absence of water bodies (point scale: 0—no water bodies; 1—presence of water bodies), and the biologically active area (percentage of area allowing vegetation to the total area; point scale: 0—0–10%; 1—11–40%; 2—41–70%; 3—71–100%). This method also allows for the assessment of areas lacking tree stands, such as meadows or reed beds, reflecting their ecological significance.

The ecological value of the tree stands [38] was assessed using a point-based method originally proposed by Roeland et al. [39] and subsequently modified to suit the objectives of this study [40]. Each tree or group of trees was assigned a score based on a composite algorithm incorporating parameters such as tree size (1–5 points), native species status (0 or 2 points), presence of invasive species (−2 or 0 points), edibility of fruit (0 or 2 points), and usefulness for pollinators (0, 1, or 2 points). The total score was further multiplied by a weight corresponding to the composition form of the trees, including solitaire trees (weight = 1), small clumps (2), in-row plantings (2), medium groups (5), and big groups (10). For each study area, except for the water reservoir, the cumulative ecological value per hectare was calculated. Additionally, the structural composition of the tree stands, in terms of both size classes and types of grouping, was analysed. To ensure transparency of the scoring system, the criteria and weighting scheme are summarised in Table 1. The structure of the method follows the logic of previous ecosystem service valuation approaches [37,39,41].

Table 1.

Criteria and scoring thresholds applied in the ecological valuation method, integrating vegetation attributes and functional contributions.

The weighting scheme and scoring thresholds were calibrated to reflect the relative ecological contributions of different tree stand configurations and habitat attributes in urban settings. The higher multiplier assigned to big groups (weight = 10) follows the rationale that larger, structurally complex patches typically support greater habitat heterogeneity and species interactions than solitary trees or small clumps, thus contributing more strongly to ecosystem functioning at the patch scale [39,40,41]. This stepwise weighting logic approximates the increase in canopy volume, within-patch connectivity, and biotic resources observed in urban ecosystem service assessments. In the evaluation system, the origin of trees was considered important, rewarding native species and lowering the score for invasive ones [42]. Criteria such as ‘edibility of fruit’ and ‘usefulness for pollinators’ were included to capture trophic resource provision and floral/nectar support; these criteria were deliberately designed as binary/ordinal to remain conservative and transparent, while being straightforward to apply in management practice [7,39].

2.3. Pre-Design Analyses

Based on field observations (performed in August 2024), a user profile was created. Then, the positive and negative aspects of the study area, namely the opportunities and threats to potential land use, were identified (SWOT) to sum up the value of the site’s natural assets and assess the condition and functionality of the existing land use. On this basis, a concept design was prepared, which addresses emerging problems and benefits from the natural, historical, and recreational potential of the site.

2.4. Tools

AutoCAD 2026 [43] was used to create schemes, spatial measurements, and design plans. Visualisations were prepared using SketchUp 8 [44] and Lumion 2025 [45].

3. Results

3.1. Vegetation Characteristics

The tree canopies covered approximately 3.47 ha of the study area, representing almost 20% of the total area (16.85 ha). The trees’ and shrubs’ species composition is very diverse, suggesting a significant transformation of the community. The overall species composition is dominated by Populus alba L., Juglans regia L., and Acer negundo L. Species less common in the study area include the following: Acer platanoides L., Salix cinerea L., Quercus robur L., Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn., and Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. Some species occur singly: Fraxinus excelsior L., Prunus padus Mill., Cornus sanguinea L., Sambucus nigra L., and Tilia cordata Mill. Some of the observed species threaten local biodiversity: Juglans regia L., Acer negundo L., Reynoutria japonica Houtt, and Robinia pseudoacacia L.

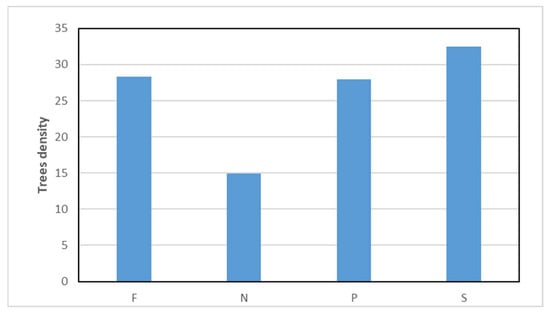

The mean number of trees per hectare varied strongly (Figure 2). The highest density of trees was observed at the shooting range; the density was slightly lower in the paths and fortification zones. The lowest non-zero density was represented by trees growing in the non-managed greenery zone. In the remaining zones there were no trees and shrubs; therefore, they were not depicted in the subsequent figures.

Figure 2.

Number of trees per hectare in each zone where trees and shrubs occurred (F—fortifications; N—non-managed or extensively managed greenery; P—paths with managed greenery; S—shooting range).

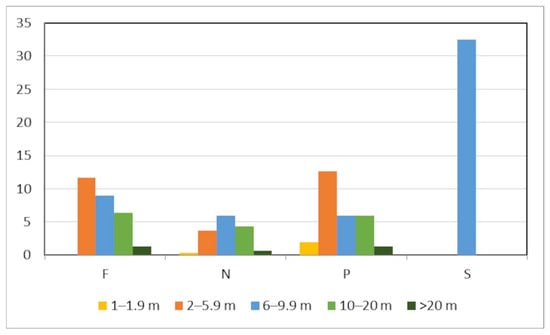

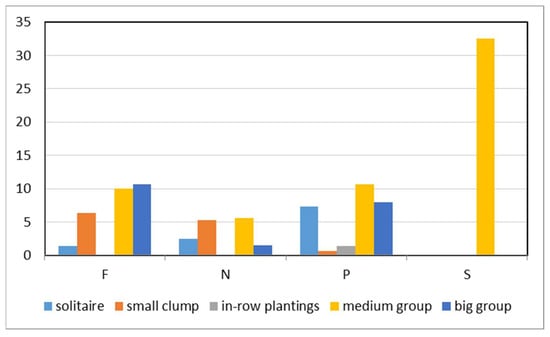

Regarding tree size distribution, fortifications, unorganised greenery, and path-adjacent areas exhibited a full range of size classes, encompassing trees from the smallest size class (1–1.9 m) to the largest individuals exceeding 20 m in height (Figure 3). Medium-sized trees (6–9.9 m) constituted the predominant size class across these zones. Interestingly, paths displayed a notably higher share of solitary trees compared to other land-use types, suggesting a distinct spatial organisation and possibly different management histories or design objectives (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Number of trees depending on size.

Figure 4.

Number of trees in each type of group.

Medium-sized trees (6–9.9 m) constituted the predominant size class across these zones. Interestingly, paths displayed a notably higher share of solitary trees compared to other land-use types, suggesting a distinct spatial organisation and possibly different management histories or design objectives (Figure 4).

In sharp contrast, the shooting range presented a highly uniform stand structure. Trees in this area were exclusively medium-sized, falling within the 6–9.9 m height category, and were arranged exclusively in medium-sized groups. The absence of smaller or larger trees and the lack of other compositional forms suggest either a homogeneous age structure or a specific planting strategy focused on creating medium-density tree groupings to fulfil ecological or functional requirements unique to the shooting range environment. The herbaceous layer under the trees and shrubs is not very diverse—mainly ruderal species and remnants of grasslands were observed. These results underscore significant spatial variability in the ecological value of urban tree stands, driven by both quantitative factors (such as tree density) and qualitative attributes, including species composition, tree size, and spatial organisation.

Due to past use and regular mowing, the rest of the study area has a rather monotonous vegetation cover, except for reed beds along water bodies, which maintain a more natural and ecologically valuable character. The remaining unwooded areas, except the reed beds above the water bodies, constitute a mosaic of herbaceous and synanthropic vegetation, covering nearly 8.08 hectares (approximately 47% of the total study area). A high degree of synanthropization of the communities was observed. There were no rare plant species observed.

The non-managed greenery (biologically active area: 100%) zone is dominated by fresh meadows formed on rich, mineral soils (Arrhenatheretalia Pawłowski 1928), with a large share of ruderal species. In these communities, grasses are dominating (Dactylis glomerata L., Lolium perenne L., and Poa pratensis L.). The most abundant synanthropic species included the following: Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop., Solidago canadensis L., Plantago major L., Tanacetum vulgare L., and Achillea millefolium L. A significant problem is the increasing expansion of Solidago canadensis L. in the study area, which reduces the species composition of other plant species.

In the shooting range, pump track, and fortifications (biologically active area: 100%), ruderal plant species begin to prevail, forming communities of Onopordetalia acanthii Br.-Bl. et R.Tx. 1943 em. Görs. 1966 and Agropyretalia intermedio-repentis Müller et Görs 1969, where a large share of Bromus inermis Leyss was observed.

The banks of the water bodies (biologically active area: 100%) are dominated by Phragmitetum communis Kaiser 1926, consisting of a monoculture of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud., with a small share of ruderal species growing in drier parts of the reeds.

Paths with managed greenery (biologically active area: 20%) are covered mainly by synanthropic vegetation mixed with cultivated grass species. The only zone without plant coverage is the passage under the flyover (biologically active area: 0%).

3.2. Evaluation of Vegetation in Aspects of Ecological Values and Naturalness

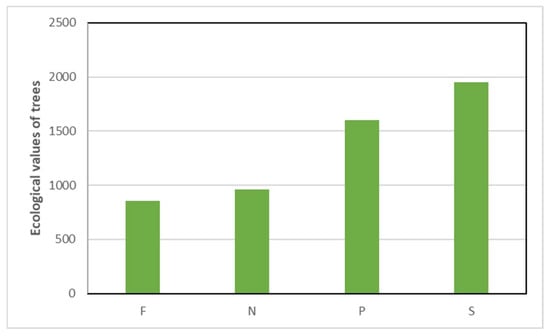

The application of the point-based ecological trees and shrubs valuation method revealed notable differences in the ecological quality of tree stands among the various land-use categories investigated (Figure 5). The highest ecological value was observed within the shooting range (S), where tree stands achieved the highest scores due to relatively high numbers of trees and favourable biocenotic characteristics. Areas along paths (P) ranked second in terms of ecological value, benefiting from both relatively dense tree cover and the presence of valuable native species contributing positively to ecosystem services.

Figure 5.

Ecological values of trees in different forms of land use. (F—fortifications; N—non-managed or extensively managed greenery; P—paths with managed greenery; S—shooting range).

In contrast, tree stands located within fortifications (F) and non-managed or extensively managed greenery (N) exhibited lower ecological value indices. The lower ecological scores in non-managed greenery were primarily attributed to a reduced density of trees, whereas in fortifications, although the number of trees was comparable to that in paths and the shooting range, the quality of the tree stand in terms of ecological attributes was diminished. These findings indicate that high tree density alone does not ensure high ecological value, highlighting the importance of species composition, size structure, and ecological functionality.

The evaluation showed that the most valuable areas are connected to the water reservoirs and the shooting range (Table 2), although their character is completely different. The reeds on the banks of the water bodies are the most natural type of vegetation in the studied area. They obtained high scores despite the lack of points for the ecological values of tree stands, highlighting the significant ecological role of semi-natural habitats alongside urban tree stands. The shooting range, however, received high scores precisely for the advantages provided by the trees and shrubs. The passage under the flyover, on the other hand, received 0 points for its ecological value. Second from the bottom of the list was the synanthropic pump track vegetation, with 4 points.

Table 2.

Evaluation of vegetation in aspects of ecological values and naturalness in each zone (F—fortifications; N—non-managed or extensively managed greenery; P—paths with managed greenery; PF—passage under flyover; PT—pump track; S—shooting range; W—water reservoirs).

3.3. User Profile

Observations indicate that the study area is only occasionally used. Nevertheless, several distinct user groups were identified. The most frequent are cyclists, who make use of the designated bike trails. Dog owners also visit regularly, using the open spaces to exercise or train their pets. Anglers are present around the ponds and moat, while archery enthusiasts frequently use the shooting range. By contrast, pedestrians, walkers, and runners were observed only sporadically. This pattern suggests that recreational use of the area is specialised and activity-specific, rather than general or widespread.

3.4. SWOT Results

The SWOT analysis revealed that the site is characterised by high potential. Mainly, recreational potential was recognised, while at the same time, threats from it were noticed. The results of the SWOT analysis are summarised in Table 3, which organises the identified strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for Fort Augustówka.

Table 3.

Summary of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) for the ecological and functional redevelopment of Fort Augustówka.

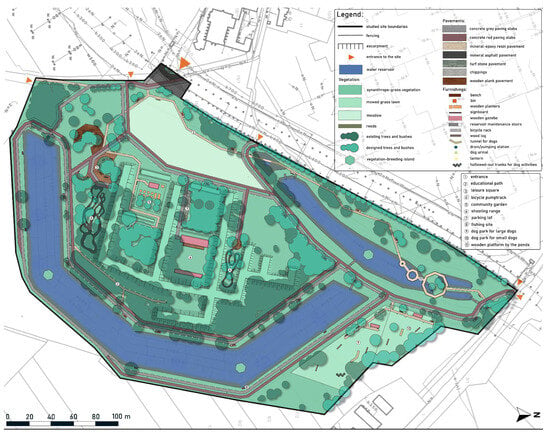

3.5. Concept Design of Fort Augustówka Park

The design concept (shown in Figure 6) was developed based on ecological and accessible design principles. The public space program was diversified in order to encourage visitors to use the space as effectively as possible. The functions of the zones were based on the area’s current user groups and their needs. The new diversified functional–spatial program aims to take advantage of the large, wastefully planned areas of the site and prevent its abandonment and pollution. Each area was assigned a clear main function, which prevents the continuation of the current bland character. At the same time, the design of the public space is intended to introduce visitors to the issue of urban biodiversity (its function and ways of protection). As a result, the area combines the aspects of leisure and recreation (pump tracks, resting areas with benches, and dog play areas), nature (being an important local part of the city’s ecological system), and education (didactic path integrating historical and environmental themes).

Figure 6.

Concept design of Fort Augustówka Park.

The composition of the park is the result of the current landscaping (demolition of elements in a good technical state would lead to unnecessary costs for the environment) and references to historical forms. The embankments, moats, and existing pedestrian/bicycle paths would be preserved. Preserving ecologically valuable solitary trees along the paths was also a priority. The composition is based on the shape of an octagon—the form of the moat (one of the main defining features of the space) is half of this geometric figure.

In order to improve visitors’ perception of the entrance space located under the flyover, a space dedicated to murals was planned. On the side of Becka Avenue, a row of Populus nigra ‘Italica’ was planned to suppress noise and visually separate recreational spaces from the street. The existing pedestrian and bicycle paths have been expanded with an entrance on the southwest boundary. Benches were added along the paths, allowing for a moment of rest.

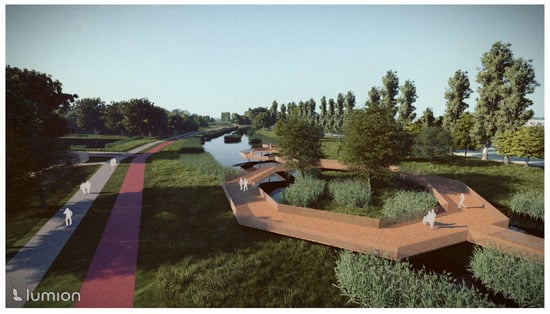

The spontaneous composition of the vegetation was preserved; however, it was planned to replace invasive species with native ones, especially on the fortifications, where the trees have low ecological value. It was decided to leave native tree stands, especially large groups, due to their phytoremediation and ecological values, as well as their positive impact on human well-being. Restoration of the fresh meadows (mowed 2 times per year) occurring in the study area was planned. The species were selected based on the existing and potential vegetation (riparian habitat) and from the dynamic circle of eutrophic or mesotrophic deciduous forests (they were chosen because the area was cut off from floodwaters responsible for the preservation of riparian forests). An additional didactic path (Figure 7) will lead through the site (with the permeable, mineral-resin surface; in some parts, the path will be routed on wooden bridges). This path allows observation of rushes enriched with plant species typical for those habitats: Alisma plantago-aquatica L., Butomus umbellatus L., Iris pseudacorus L., Mentha aquatica L., and Sparganium erectum L. emend. Rchb. Additionally, plantings of aquatic vegetation with floating leaves were planned: Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm., Nymphaea alba L., and Polygonum amphibium L. It was also chosen to implement some Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. trees on the edge of the reeds. The path was designed to explain aspects of the fort’s natural and historical values, shown on educational boards. This will allow users to learn about, among other things, the vegetation cover of the site, the importance of urban biodiversity, and the impact of invasive species on flora and fauna.

Figure 7.

Visualisation—aerial view of the wooden viewing platforms designed over the water reservoirs.

Besides the nature trail, four main features were planned: a shooting range, a community garden, pump tracks, and a dog play area. The first one is the western shooting range. It was planned to be upgraded (the eastern one needs to be removed due to its proximity to pedestrian space) to improve safety. A gazebo and a small parking lot (with a surface made from perforated concrete slabs) were planned. The entire area of the new shooting range will be fenced off, and the borders will be planted with trees to improve its isolation. The second one—the community garden (Figure 8)—was intended to integrate the local community using the fort area. It will also be equipped with a gazebo, allowing people to socialise. Elements necessary for plant cultivation were also planned: wooden growing containers and a composter. Fruit trees will be added, creating a small orchard. The third feature is modernised pump trucks. Renovation of the mineral surface was planned. In its vicinity, wooden relaxation areas will be provided with benches, sunbeds, trash cans, and bike racks. Native tree species (Acer platanoides L., Cerasus avium (L.) Moench, and Fraxinus excelsior L.) will be planted to create some shade. Finally, a large-scale grassy area to the north of the moat will be adapted into a dog play area, separately for small and larger dogs. The entrance to the site will be protected by a double gate for safety purposes (avoiding potential escape of the dogs). Both paddocks will be equipped with wooden vertical elements (allowing dogs to urinate) and some obstacle courses in the form of logs and hollow tree trunks. Benches under the trees and gazebos (used in unfavourable weather conditions) will be placed for the owners.

Figure 8.

Visualisation—aerial view of the community garden.

4. Discussion

Maintaining natural processes in cities requires skilled spatial management from the authorities, as it requires reconciling the interests of both human and non-human inhabitants of the city. The network created based on urban green areas not only ensures the proper course of biological processes but also gives residents easy access to green areas usually used for leisure and recreation [46]. Easy access for humans to green spaces is crucial in spreading knowledge about nature, and it also provides an opportunity to induce pro-ecological behaviours in users [47,48]. It helps to restore a sense of responsibility for the environment and being part of nature [47,49]. However, human activity leads to the transformation of the environment, including changes in vegetation. As a result of these transformations in cities, we can observe at the same time habitats with different levels of naturalness: natural ecosystems (forests, water bodies, and peat bogs), semi-natural ecosystems (meadows and grasslands), and synanthropic vegetation (ruderal and segetal communities) [50]. Sustainable development significantly contributes to the protection of biodiversity by ceasing the overexploitation of natural resources and by promoting the restoration of anthropogenically degraded environments [46]. The described Augustówka Fort is an area with a highly transformed vegetation cover (mainly semi-natural and synanthropic), but with easy access. Although our results indicate relatively low ecological values for tree stands within the fortification area, the site still offers considerable potential for ecological improvement, particularly through the conservation and enhancement of semi-natural vegetation. It is an ideal place to implement a design that will improve natural and social qualities, in accordance with the idea of sustainable development and ecological design.

Urban vegetation must contend with numerous problems, such as progressive urbanisation, which promotes the process of synanthropization [50]. However, this does not have to be a negative phenomenon in areas with strongly transformed vegetation. Some synanthropic plant species (apophytes) are native [51] and therefore do not pose an ecological threat in areas strongly affected by anthropopressure. In such areas, synanthropic vegetation (except for invasive species) can be used in design, as it does not threaten any valuable species or ecosystems. Synanthropic (spontaneous) species are already widely used in urban greenery [52]. Recent studies show that their presence can evoke nostalgia and make spaces appear more natural in people’s perception [53]. Those species are generally accepted in public spaces [54] contrary to superficial beliefs, and their functions may be more significant in the future [55]. They do not require intensive maintenance, while at the same time they are equally effective (or even more effective, depending on the type of plantings) in improving urban climate conditions as conventional plantings [50,56]. The use of synanthropic species is in line with the idea of sustainable development, which satisfies current human needs without negatively impacting the functioning of future generations [57]. The need for conducting extensive research to optimise land management and direct the program in line with the city’s green space development strategy is stated in the literature by, among others, Zinowiec-Cieplik [58].

A distinctive challenge in maintaining biodiversity in urban green spaces is the spread of invasive species; therefore, we decided to recommend their eradication or reduction, if the first proposed action is not possible. Invasive species should be removed using methods developed for specific species, with scientifically proven effectiveness. For example, invasive Solidago species can be controlled by mowing twice a year, with mulching using hay collected from meadows with high plant diversity, which would significantly reduce the area covered by Solidago sp. [59]. If the invaded areas are smaller, invasive species can also be removed mechanically. It is important to monitor flora by specialists (e.g., botanists; landscape architects) in order to quickly detect plant invasions and plan mitigation. As the example of Fort Augustówka shows, the absence of such management can lead to plant invasion. Plant invasions are particularly visible in cities, where human impact is much more significant than in non-urban areas [60]. Negative effects of plant invasions include the displacement of native species, a reduction in the number of pollinators, and even the destruction of infrastructure [60]. The proposed design tries to solve the issue of invasive plant species and to improve lost biodiversity by enriching impoverished areas with native plant species. As a result, the site serves as an ecological corridor, enhancing ecological connectivity. It also provides recreational opportunities in natural-like surroundings, confirming the third hypothesis.

The conducted evaluation of greenery showed that natural and semi-natural greenery, e.g., reeds and meadows, had higher ecological values than conventionally managed greenery (planted; mowed). According to our research, Fort Augustówka is covered by spontaneous greenery that is particularly diverse in forms (trees, shrubs, ruderal grasslands, meadows, and rushes). Such areas provide greater habitat diversity than areas with intensively managed greenery or monocultures of invasive species growing on abandoned sites, which confirms hypothesis 2. The result of the ecological evaluation of greenery was not always related to the characteristics of the tree stands.

The results of this study highlight substantial heterogeneity not only in the ecological value of tree stands but also across different types of urban vegetation, emphasising the complex interplay between tree stand composition, the presence of semi-natural habitats like reeds and meadows, spatial arrangement, and ecological functionality. While the highest tree stand ecological values were recorded in the shooting range and along paths, it is crucial to recognise that zones dominated by semi-natural vegetation, such as reed beds along water bodies, also achieved very high ecological scores in the overall assessment. This underscores that specific management practices, intentional planting schemes, and the conservation of natural or semi-natural habitats may significantly influence the ecological quality of urban green spaces [39]. In particular, although the uniform structure observed in the shooting range, dominated exclusively by medium-sized trees arranged in medium groups, could reflect deliberate design choices aimed at achieving certain ecological or functional objectives, it remains equally important to consider habitats like meadows or reeds, which, despite limited tree cover, provide high biodiversity value and ecosystem services. Recognising the ecological contributions of both tree stands and other vegetation types offers a more comprehensive perspective essential for sustainable urban green space planning.

Our findings align with broader ecosystem service research, which demonstrates that semi-natural habitats such as meadows and reed beds provide disproportionately high support for pollinators and invertebrate diversity compared to intensively managed greenery [7]. In contrast, urban tree arrays contribute strongly to carbon sequestration and microclimate regulation through shading and evapotranspiration [8]. Both habitat types therefore provide complementary ecological services: meadows and ruderal communities enhance pollination and habitat heterogeneity, while tree stands contribute to climate regulation and long-term carbon storage. Recognising this complementarity is crucial for urban planning that seeks to maximise the multifunctionality of green infrastructure [9].

Conversely, areas such as fortifications and non-managed greenery exhibited lower ecological value scores in terms of tree stands, despite sometimes comparable tree densities, as observed in the fortification zone. However, these zones can still possess significant ecological value through other vegetation types, such as meadows or spontaneous herbaceous communities, which contribute to biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in ways not directly reflected in tree stand metrics. This discrepancy underscores that assessing urban green spaces requires consideration of qualitative aspects of vegetation—including species composition, presence of invasive species, ecological services provided—as well as the broader mosaic of habitats, rather than focusing solely on tree density [40]. Such findings align with previous research indicating that urban green spaces can differ dramatically in ecosystem service provision, even when similar in structural characteristics [35].

The significantly higher share of solitary trees along paths is another noteworthy pattern, potentially linked to urban design principles that favour visual openness, safety, or aesthetic appeal in public corridors. While solitary trees can serve as valuable ecological assets, their isolated positioning may limit certain ecosystem services, such as habitat connectivity or microclimate regulation, compared to trees arranged in groups [39]. Moreover, their ecological value should be assessed alongside other green elements, such as herbaceous layers or semi-natural habitats, to ensure urban planning considers the full ecological potential and trade-offs between aesthetic and ecological objectives when designing green infrastructure, especially in highly frequented public spaces.

Furthermore, the absence of trees from both the smallest (<2 m) and largest (>20 m) size classes in the shooting range may indicate either relatively recent establishment or management practices aimed at maintaining a uniform stand structure. While such uniformity can simplify maintenance and meet specific functional requirements, it may reduce the overall biodiversity and long-term resilience of the tree stand. Heterogeneous stands, encompassing diverse species and size classes, are typically better equipped to provide a broad spectrum of ecosystem services and withstand environmental disturbances [40]. Nonetheless, this should be considered in tandem with other valuable vegetation types, such as meadows or reed beds, whose biodiversity roles can compensate for lower diversity in tree layers, ensuring a balanced ecological function of the entire urban green space.

Overall, these findings emphasise that urban green space management should not focus solely on tree density or aesthetic considerations but should incorporate comprehensive ecological assessments that capture the full diversity of urban vegetation, including semi-natural habitats like meadows and reeds. The modified valuation method applied in this study proved effective in distinguishing subtle differences in ecological value across various urban land-use contexts, demonstrating its potential utility as a decision-support tool for urban green space planning and management [39,40]. At the same time, this valuation method should be regarded as a pilot framework tailored to post-military urban landscapes. Its structure was informed by established approaches to ecosystem service assessment [7,36,39], but further calibration across multiple sites would strengthen its robustness and comparability. A key advantage of the approach is its transparency: by clearly summarising scoring criteria and weighting factors, the method offers a reproducible tool that can be applied not only in research but also in practical biodiversity management. Although piloted here for Fort Augustówka, the framework can be adapted for other post-socialist cities where military heritage landscapes represent a significant yet underutilised ecological resource. Future research could further refine this approach by integrating additional ecological indicators, such as habitat value of herbaceous communities, resilience to climate change, or contributions to urban ecosystem services, to enhance the precision and applicability of urban ecological assessments.

Fortification areas, such as Fort Augustówka, can be important elements of the city’s natural and recreational structure. Once they are abandoned, secondary succession begins to occur [61], which could be observed clearly on ramparts and shores of water bodies of Fort Augustówka. Although the ecological evaluation conducted in this study indicated that the fortification areas currently exhibit relatively low ecological values in tree stands, their high share of semi-natural vegetation, such as meadows or ruderal communities, reveals significant ecological potential. Such greenery of fortress areas is characterised by the capacity to support diverse plant and animal species [62,63,64]. These strengths can be fully utilised, especially if the development is carried out in accordance with the principles of ecological design, as we stated in the first hypothesis.

The existing vegetation of Fort Augustówka plays a complementary role in maintaining urban biodiversity. Its ecological value should be compared with other areas subject to similar shaping factors, particularly those exposed to strong anthropogenic pressure, such as conventionally managed greenery or spontaneous vegetation on brownfields. In such contexts, semi-natural habitats (e.g., meadows, ruderal communities, and reed beds) often provide higher plant diversity and habitat heterogeneity than intensively maintained lawns and plantings. Similar findings have been reported in studies on grasslands with different mowing regimes, where frequent mowing was associated with lower species diversity compared to less intensively managed areas [65,66]. These observations support our evaluation of Fort Augustówka, where semi-natural vegetation demonstrates significant ecological potential despite the generally low values of tree stands.

Although our results showed relatively low ecological values in tree stands within the fortification area, the site possesses significant potential for ecological improvement. Typical ecological design parks are often established on wastelands or post-industrial sites, revitalised according to the brownfields principle [67], but this approach can also be effectively applied to fortress landscapes. This strategy emphasises the so-called regenerative design aspect, aiming to create spaces capable of regenerating lost resources [58,68]. Achieving a degree of self-sufficiency is one of the main factors making ecological design so popular [69], and that is why we propose using the existing ecological assets, including spontaneous vegetation, so that less interference is needed to maintain the site. Nevertheless, it is important to address current limitations, such as the presence of invasive species and the relatively low ecological value of tree stands, to fully realise this potential. Although ideas for including fortifications in the natural system of Polish cities have appeared at various points in history [70,71], they were often not implemented. Nowadays, with a shortage of undeveloped land in cities for both construction and green space development, some former fortifications have finally been integrated into urban design. It is also a challenge to respect preserved historical structures, although this should remain a priority during new investments [72]. In our project, we decided to leave the remaining historic structures untouched, allowing further plant succession while enhancing ecological functionality. The remainings of previous development have been used in similar ways in various projects of restored brownfields and fortifications, for example in the Schanzengraben (former moat of the fortress incorporated into the city structure by giving it recreational functions and preserving the spontaneous vegetation on its banks) in Zurich [73] and Park am Gleisdreieck and Natur-Park Südgelände in Berlin (parks with spontaneous vegetation originating from succession on former railyard, with some old infrastructure preserved) [74,75].

The presented way of analysis and designing green areas in post-fortress facilities is a novelty in the development of former fortresses in Poland. This is particularly important in an era of strong urbanisation pressure on historic structures within city borders. This complex approach related to ecological design is not only economical (due to its low cost) but also improves residents’ quality of life and helps preserve biodiversity in the city [56]. The proposed fusion of the historical value of these sites with their practical and environmental value (mostly based on existing, spontaneous greenery) is an innovative approach to former military sites in Poland. Therefore, we recommend its application in projects involving former fortification sites, provided that ecological assessments guide interventions to maximise biodiversity benefits. The presented approach can become an inspiration for architects, urban planners, and local authorities.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated considerable variation in the ecological value of vegetation across different urban land-use types in former military landscape. We suggest that the following factors should be taken into account when assessing the ecological value of individual parts of urban green spaces: tree stand values, naturalness of vegetation, biologically active area, and the presence of water elements. In this research, the highest ecological values of tree stands were observed in the shooting range and along paths, where favourable tree composition and structure contributed positively to ecosystem services. In contrast, lower ecological values recorded in fortifications and non-managed greenery highlight that tree density alone is not sufficient to ensure high ecological quality, underscoring the importance of species composition, structural diversity, and spatial arrangement

Nevertheless, our findings suggest that fortification areas like Fort Augustówka hold significant ecological potential, particularly due to semi-natural vegetation such as meadows or reeds. Importantly, our results indicate that elements other than tree stands, such as reeds and meadows, can possess significant ecological value due to their contribution to biodiversity and ecosystem functions, even in the absence of substantial tree cover. Therefore, ecological assessments and urban green space planning should adopt a holistic perspective, considering the full mosaic of vegetation types rather than focusing solely on trees.

The modified point-based assessment method applied in this study proved effective in capturing both quantitative and qualitative differences in urban green areas, offering a practical tool for evaluating ecological value in urban planning and management contexts. These findings emphasise the need for urban green space strategies that balance aesthetic considerations with ecological functionality to enhance biodiversity, resilience, and ecosystem services in urban environments.

In response to rapid changes in the natural environment, cities are increasingly adopting sustainable development strategies. In such approaches, post-fort areas should be recognised as important elements of the ecological and recreational structure, protected through spatial planning mechanisms. The application of sustainable ecological design in such sites should be a priority. While our study showed that current ecological values in fortification areas may be relatively low, particularly in tree stands, these areas nonetheless possess significant ecological potential, especially through the presence of semi-natural vegetation formed by secondary succession.

Future efforts should prioritise preserving and enhancing natural and semi-natural spontaneous vegetation, which is often more ecologically valuable than conventional, intensively managed greenery. An important element of such strategies is to eliminate threats such as invasive plant species (conducted comprehensively by specialists—from flora monitoring to selection of invasive plant eradication methods), while also working to restore pre-invasion ecological conditions by introducing native plant species. Through these actions, post-military landscapes like Fort Augustówka can fulfil important ecological roles and additionally serve educational functions, raising public awareness about the urban ecological system and biodiversity conservation.

From a policy perspective, post-military landscapes such as Fort Augustówka should be explicitly integrated into municipal strategies for urban green infrastructure. Warsaw is currently exploring improved governance models for managing urban greenery to better preserve biodiversity. Our findings support the need for adaptive management policies that combine ecological restoration with low-cost, community-oriented interventions. Urban renewal practice should prioritise nature-based solutions and regenerative design principles, ensuring that sites with high potential for biodiversity supporting are preserved while providing accessible recreational opportunities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.D., B.F.-P., M.O., M.P., and F.K.; methodology, S.D., B.F.-P., M.O., F.K., and M.P.; software, M.O., F.K., and S.D.; validation, M.P., B.F.-P., S.D., M.O., and F.K.; formal analysis, M.O., B.F.-P., and F.K.; investigation, B.F.-P., S.D., M.P., M.O., and F.K.; resources, M.P., B.F.-P., S.D., and F.K.; data curation, F.K., M.O., and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D., B.F.-P., F.K., M.O., and M.P.; writing—review and editing, B.F.-P., F.K., M.P., and M.O.; visualisation, F.K., M.O., and S.D.; supervision, B.F.-P., M.P., F.K., and M.O.; project administration, M.P. and B.F.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Perplexity AI for literature searching. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aronson, M.F.J.; La Sorte, F.A.; Nilon, C.H.; Katti, M.; Goddard, M.A.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Warren, P.S.; Williams, N.S.G.; Cilliers, S.; Clarkson, B.; et al. A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20133330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beninde, J.; Veith, M.; Hochkirch, A. Biodiversity in cities needs space: A meta-analysis of factors determining intra-urban biodiversity variation. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Werner, P. Urban biodiversity and the case for implementing the convention on biological diversity in towns and cities. In Urban Biodiversity and Design, 1st ed.; Müller, N., Werner, P., Kelcey, J.G., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mathey, J.; Rößler, S.; Banse, J.; Lehmann, I.; Bräuer, A. Brownfields as an element of green infrastructure for implementing ecosystem services into urban areas. J. Urban Plan. Dev. Div. 2015, 141, A4015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, B.; Kovalcsik, T.; Kovács, Z. Regeneration of Military Brownfield Sites: A Possible Tool for Mitigating Urban Sprawl? Land 2025, 14, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.A.; Chadwick, M.A. Urban Ecosystems: Understanding the Human Environment, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldock, K.C.R.; Goddard, M.A.; Hicks, D.M.; Kunin, W.E.; Mitschunas, N.; Osgathorpe, L.M.; Potts, S.G.; Robertson, K.M.; Scott, A.V.; Stone, G.N.; et al. Where is the UK’s pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20142849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.J.; Greenfield, E.J.; Hoehn, R.E.; Lapoint, E. Carbon storage and sequestration by trees in urban and community areas of the United States. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Galera, H. Warsaw. In Plants and Habitats of European Cities, 1st ed.; Müller, N., Kelcey, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 499–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejda, M.; Pyšek, P.; Jarošík, V. Impact of invasive plants on the species richness, diversity and composition of invaded communities. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna-Antoszkiewicz, B.; Łukaszkiewicz, J.; Rosłon-Szeryńska, E.; Wysocki, C.; Wiśniewski, P. Invasive species and maintaining biodiversity in the natural areas–rural and urban–subject to strong anthropogenic pressure. J. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 19, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BGiK. Historical Maps of Warsaw; Office of Surveying and Cadastre (BGiK): Warsaw, Poland, 1976–2023; From Warsaw Map Services; Available online: https://mapa.um.warszawa.pl/mapaApp1/mapa?service=mapa_historyczna (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Wilkaniec, A.; Chojnacka, M. Krajobraz warowny–niewykorzystany walor turystyczny Poznania. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2010, 27, 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Figuła-Czech, J.; Gawlak, A.; Grabowski, W.; Kowalski, T.; Wojciechowski, M. Twierdza Poznań Przewodnik po Fortyfikacjach, 1st ed.; Grabowski, W., Kowalski, T., Eds.; SGK—Tomasz Kowalski: Grudziądz, Poland, 2024; pp. 325–391. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbrandt, H. Insurgent participation: Consensus and contestation in planning the redevelopment of Berlin-Tempelhof airport. Urban Geogr. 2016, 38, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Haase, D. Green justice or just green? Provision of urban green spaces in Berlin, Germany. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2014, 122, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vačkář, D.; Orlitová, E.; Beňová, A.; Klusáček, P. Developing ecosystem services assessment for policy support in Central Europe: Case study of urban brownfield regeneration in Prague. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 30, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, M.; Kaiser, D.; Barthelmes, A. Green infrastructure in Vienna: Case study Aspern Seestadt. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhu, H. A study on the evolution of original sites of fortifications from the perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: Cases of Paris, Beijing, and Moscow. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, J.; Metelski, D. Innovative Approaches to Urban Revitalization: Lessons from the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex Project in Warsaw. Buildings 2025, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, P.Y.; An, B.W.; Guo, Q.P. Urban green infrastructure: Bridging biodiversity conservation and sustainable urban development through adaptive management approach. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1440477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowacki, L. Obrona Warszawy i Modlina 1939, 1st ed.; Polish Ministry of National Defence: Warsaw, Poland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Królikowski, L. Twierdza Warszawa. Twierdze i Zamki Obronne w Polsce, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Bellona: Warsaw, Poland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, P.; Łaska, M.; Majchrzak, A.; Cichocki, M. Gleby. In Atlas Ekofizjograficzny Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy, 1st ed.; Fogel, P., Ed.; Biuro Architektury i Planowania Przestrzennego M. St. Warszawy: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Fic, M.; Kręgiel, J.; Grądziel, I. Budowa geologiczna. In Atlas Ekofizjograficzny Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy, 1st ed.; Fogel, P., Ed.; Biuro Architektury i Planowania Przestrzennego M. St. Warszawy: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Okołowicz, W. Strefy klimatyczne. In Atlas Geograficzny, 1st ed.; PPWK: Warsaw, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bednorz, E.; Tomczyk, A.M. Atlas Klimatu Polski (1991–2020), 1st ed.; Wyd. Naukowe Bogucki: Poznań, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszkiewicz, J.M. Geobotanical Regionalization of Poland, 1st ed.; IGSO PAS: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszkiewicz, J.M. Potential Natural Vegetation of Poland (Potencjalna Roślinność Naturalna Polski), 1st ed.; IGiPZ PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mirek, Z.; Piękoś-Mirkowa, H.; Zając, A.; Zając, M. Vascular Plants of Poland. An Annotated Checklist. Rośliny Naczyniowe Polski. Adnotowany Wykaz Gatunków, 1st ed.; W. Szafer Institute of Botany: Kraków, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki, C.; Sikorski, P. Fitosocjologia Stosowana w Ochronie i Kształtowaniu Krajobrazu, 3rd ed.; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie: Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde, 1st ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszkiewicz, W. Przewodnik do Oznaczania Zbiorowisk Roślinnych Polski, 3rd ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarska-Guzik, B.; Dajdok, Z.; Zając, M.; Zając, A.; Urbisz, A.; Danielewicz, W.; Hołdyński, C. Rośliny Obcego Pochodzenia w Polsce ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Gatunków Inwazyjnych, 1st ed.; Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Barton, D.N. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Larondelle, N.; Andersson, E.; Artmann, M.; Borgström, S.; Breuste, J.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Gren, Å.; Hamstead, Z.; Hansen, R.; et al. A quantitative review of urban ecosystem service assessments: Concepts, models, and implementation. Ambio 2014, 43, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amador-Cruz, F.; Figueroa-Rangel, B.L.; Olvera-Vargas, M.; Mendoza, M.E. A systematic review on the definition, criteria, indicators, methods and applications behind the Ecological Value term. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, S.; Moretti, M.; Amorim, J.H.; Branquinho, C.; Fares, S.; Morelli, F.; Niinemets, Ü.; Paoletti, E.; Pinho, P.; Sgrigna, G.; et al. Towards an integrative approach to evaluate the environmental ecosystem services provided by urban forest. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1981–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimkowska, L.; Wojtatowicz, J. The method of valorisation of trees according to their biocenotic values. Maz. Reg. Stud. 2021, 2021, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaciak, A. Inwentaryzacja i wycena wartości drzew w przestrzeni publicznej Kórnika w kontekście postulatów polityki ekologicznej Unii Europejskiej. Stud. I Pr. WNEiZ 2015, 42, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundu, G.; Richardson, D.M. Planted forests and invasive alien trees in Europe: A code for managing existing and future plantings to mitigate the risk of negative impacts from invasions. NeoBiota 2016, 30, 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk Inc. AutoCAD 2026, Autodesk Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025.

- Trimble Inc. SketchUp 8, Trimble Inc.: Westminster, CO, USA, 2025.

- Act-3D B.V. Lumion 2025, Act-3D B.V.: Sassenheim, The Netherlands, 2025.

- Dudkiewicz, M.; Kopacki, M.; Iwanek, M.; Hortyńska, P. Problems with the experience of biodiversity on the example of selected Polish cities. Agro. Sci. 2021, 76, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Arvai, V. Engaging urban nature: Improving our understanding of public perceptions of the role of biodiversity in cities. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.L.; Milfont, T.L. Exposure to urban nature and tree planting are related to pro-environmental behavior via connection to nature, the use of nature for psychological restoration and environmental attitudes. Environ. Behav. 2018, 51, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D.C.; Hobbs, R.J. Cultural ecosystem services: Characteristics, challenges and lessons for urban green space research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 25, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Mandziuk, A.; Kiraga, M. Wybrane Aspekty Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Zielonych Przestrzeni Miejskich, 1st ed.; Warsaw University of Life Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sukopp, H. Apophytes in the flora of Central Europe. Pol. Bot. Stud. 2006, 22, 473–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kamionowski, F.; Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Bihunova, M. Application of synanthropic plants in the design of green spaces in Warsaw (Poland). Acta Hort. Regiotec. 2023, 26, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lu, Y.; Jia, J.; Chen, Y.; Xue, J.; Liang, H. Urban spontaneous vegetation helps create unique landsenses. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.P.; Fernandes, C.O.; Ryan, R.; Ahern, J. Attitudes and preferences towards plants in urban green spaces: Implications for the design and management of Novel Urban Ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 314, 115103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Tredici, P. Spontaneous urban vegetation: Reflections of change in a globalized world. Nat. Cult. 2010, 5, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Fu, D.; Hou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, T.; Chen, H.; Yan, H.; Shao, F.; Zhang, Y. Diversity of Spontaneous Plants in Eco-Parks and Its Relationship with Environmental Characteristics of Parks. Forests 2023, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicharska, M.; Smithers, R.; Mikusiński, G.; Ronnback, P.; Harrison, P.; Nilsson, M.; Sutherland, W. Biodiversity’s contributions to sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinowiec-Cieplik, K. Zagadnienia projektowania regeneratywnego w mieście. Acta Sci. Pol. Archit. 2020, 19, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymura, M.; Świerszcz, S.; Szymura, T.H. Restoration of ecologically valuable grassland on sites degraded by invasive Solidago: Lessons from a 6-year experiment. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.A.; Chadwick, M.A. Urban invasions: Non-native and invasive species in cities. Geography 2015, 100, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardela, Ł.; Kowalczyk, T.; Bogacz, A.; Kasowska, D. Sustainable Green Roof Ecosystems: 100 Years of Functioning on Fortifications—A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunović, S.; Špehar, V.; Štefanić, E.; Haring, T.; Božić-Ostojić, L. The Brod Fortress-an oasis of biodiversity in the center of Slavonski Brod. In Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific/Professional Conference, Agriculture in Nature and Environment Protection, Vukovar, Croatia, 1–3 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mladenovic, E.; Ljevnaic-Masic, B.; Lakicevic, M.; Pavlovic, L.; Cukanovic, J. The urban flora of a spatial cultural-historical unit of great importance: A case study of the Petrovaradin Fortress (Novi Sad, Serbia). Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2021, 30, 12174–12190. [Google Scholar]

- Pałubska, K. The greenery and natural terrain obstacles from the Warsaw Fortress that shaped the city’s ecological system. Archit. Kraj. 2014, 2, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, S.; Brabant, C.; Tessier, S.; Jung, V. From urban lawns to urban meadows: Reduction of mowing frequency increases plant taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic diversity. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2018, 180, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Pasternak, G.; Sas, W.; Hurajová, E.; Koda, E.; Vaverková, M.D. Nature-Based Management of Lawns—Enhancing Biodiversity in Urban Green Infrastructure. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrycz, P. Wybrane londyńskie strategie przekształceń urbanistycznych na potrzeby mieszkalnictwa dostępnego. Hous. Environ. 2020, 32, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, P.; Reed, B. Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, K. Urban green space systems as a tool for sustainable urban development of a city. Nature-based design with an example of a case study of London Wetland Centre. Przestrz. I Forma 2013, 19, 249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Środulska-Wielgus, J.; Wielgus, K. Protection and shaping of the fortification’s greenery of the former Kraków fortress: Theory, standards, practice. Urban. Archit. Files Pol. Acad. Sci. Kraków Branch. 2022, 50, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkaniec, A.; Urbański, P. Twierdza Poznań w krajobrazie na przestrzeni XIX i XX wieku—Od krajobrazu rolniczego po zurbanizowany. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2010, 9, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Pardela, Ł. Współczesne znaczenie zieleni zabytkowych fortyfikacji z przełomu XIX/XX w. na przykładzie Wrocławia. In Dawne fortyfikacje. Dla turystyki, rekreacji i kultury, 1st ed.; Narębski, L., Ed.; Towarzystwo Opieki nad Zabytkami Oddział w Toruniu: Toruń, Poland, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Zaykova, E.Y. Postindustrial space: Integration of green infrastructure in the center, middle and periphery of the city. In Megacities 2050: Environmental Consequences of Urbanization. ICLASCSD 2016, 1st ed.; Vasenev, V., Dovletyarova, E., Chen, Z., Valentini, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; Langer, A. Natur-Park Südgelände: Linking Conservation and Recreation in an Abandoned Railyard in Berlin. In Wild Urban Woodlands, 1st ed.; Kowarik, I., Körner, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dooren, N. Park am Gleisdreieck, a dialectical narrative. J. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 14, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).