1. Introduction

Land serves as a fundamental input and core asset in agricultural production [

1], playing an irreplaceable strategic role in national food security and rural economic development. In rural communities, land is not only foundational to farmers’ livelihoods but also a critical vehicle for asset appreciation and participation in market-driven resource allocation [

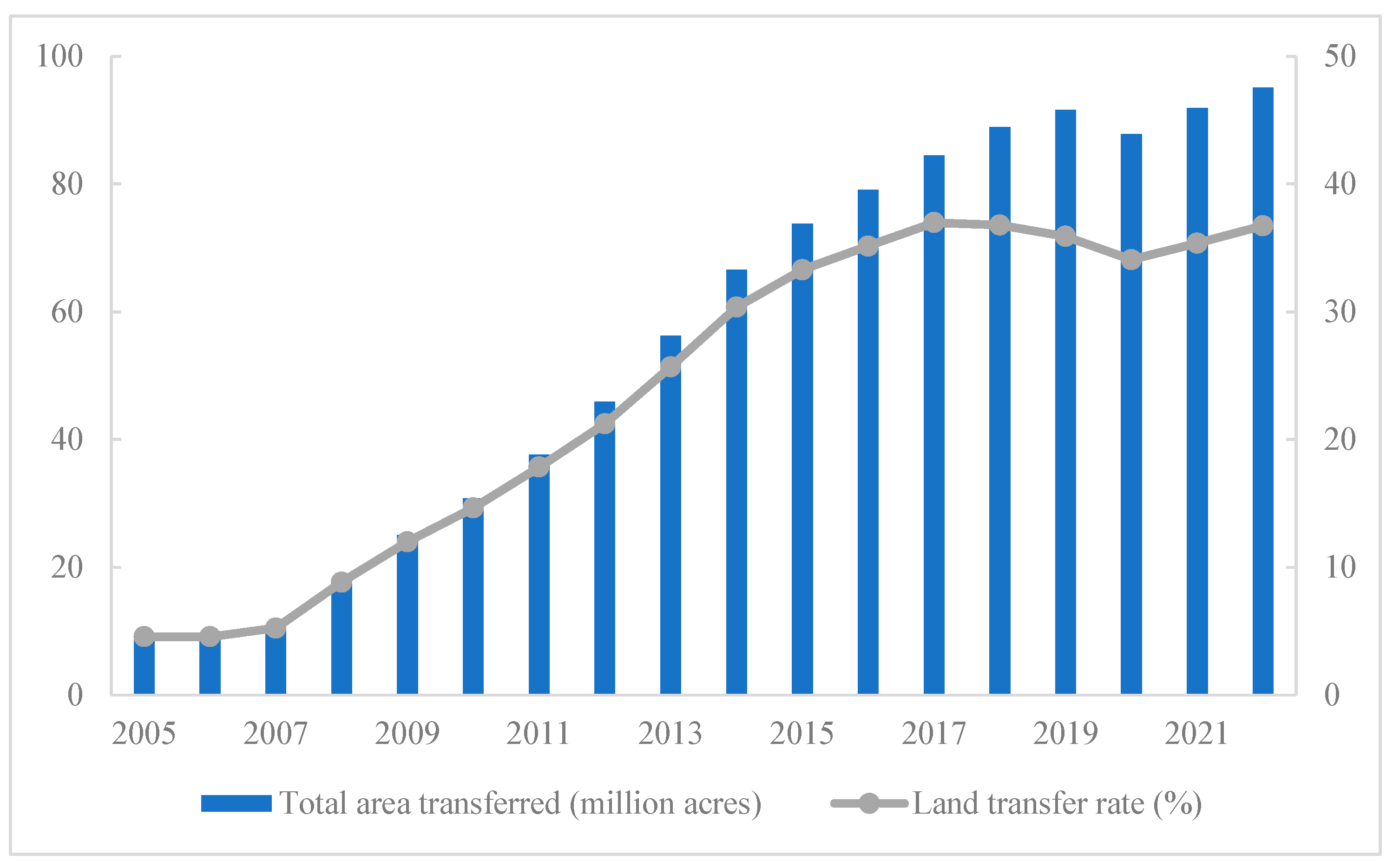

2]. Rural land transfer denotes the process wherein farm households maintain ownership and contractual rights, yet convey the management rights of their contracted cultivated land to new-type agricultural operation entities via market-oriented contractual agreements. International evidence consistently shows that rural land transfers—by reallocating resources to more productive operators [

3,

4]—significantly enhance agricultural productivity, mitigate the constraints of land fragmentation [

5], and create dual income streams for smallholders through lease payments and off-farm employment, with empirical studies confirming substantial household income gains [

6,

7]. More importantly, once farmers transfer their land management rights, they no longer need to cultivate their own small plots of land, thereby freeing themselves from agricultural production and gaining the time and energy to engage in local non-agricultural work or seek employment elsewhere. This releases labor and corrects misallocation of resources, driving the transformation of the rural economy from subsistence agriculture to commercialized operations [

8]. This process creates a three-dimensional value chain of efficiency improvements, income growth, and structural transformations [

9]. Consequently, by regulating and guiding the transfer of rural land use rights, scattered small plots of land can be consolidated and entrusted to more capable entities for management, thereby achieving a more reasonable and efficient farm scale. This has become the core approach to unlocking agricultural potential and optimizing resource allocation. Global experience shows that the consolidation of scattered plots of land through rural land transfers has generally promoted the scale and technological application of agricultural production, significantly improved resource utilization efficiency and output levels, and effectively supported the development of agricultural modernization [

5]. Diverse approaches demonstrate this, ranging from market-driven consolidation models in Europe and the U.S. to coordinated transfer mechanisms facilitated by organized entities, such as Japan’s JA (Japan Agricultural Cooperatives) and South Korea’s agricultural cooperatives, and China’s landmark “Three Rights Separation” reform. This Chinese reform upholds rural land collective ownership while separating ownership, contract, and management rights [

10,

11].

However, rural land transfers face severe constraints due to limited financial access. Remote areas, with their scarcity of financial institutions, experience chronic deficiencies in formal financial services. As financial inclusion is essential for rural revitalization and agricultural modernization, overcoming these barriers is imperative. Digital financial inclusion (DFI) leverages digital technologies to fundamentally restructure financial service models. By innovating products and optimizing processes, it overcomes traditional limitations, enhancing the reach and efficiency of financial services to mitigate imbalances and inadequacies in financial development. Its evolution constitutes a critical pathway for empowering rural development through finance [

12]. Its core strengths—extensive geographic reach, lower operational costs, and efficient service delivery—significantly expand financial coverage and accessibility. These strengths effectively reach previously excluded populations, demonstrating unparalleled inclusivity. Digital technology enhances information flow and transaction transparency [

13], substantially reducing providers’ operational and risk management costs and enabling farmers to access more affordable credit. Furthermore, integrated information services on DFI platforms help bridge the urban–rural information gap context-specific design features such as multilingual interfaces, voice-assisted navigation, and community-based “digital mentors” programs. For example, according to the World Bank’s 2025 report titled

Digital Financial Inclusion in India: Evidence from the PMJDY Program, combining DFI access with basic digital literacy courses increases platform utilization by 42% among rural women. There are significant cross-national variations in DFI implementation. Developed countries, leveraging mature digital infrastructure and robust agricultural financial systems, can effectively provide technological and financial support for the scaling of farm operations. Taking the United States as an example, digital tools such as agricultural insurance work together to address challenges like diseconomies of scale and risk concentration that inevitably arise after farm consolidation. This powerfully propels the scaling process of agricultural operations post-consolidation. Many developing nations, however, still primarily rely on basic services such as mobile payments to achieve financial inclusion. These services have limited application in deepening rural land transfer markets. Leveraging its massive internet user base and strong policy support, China has achieved rapid advancements in mobile payments and digital credit. These developments make China a compelling research setting for examining how DFI enables rural land transfer.

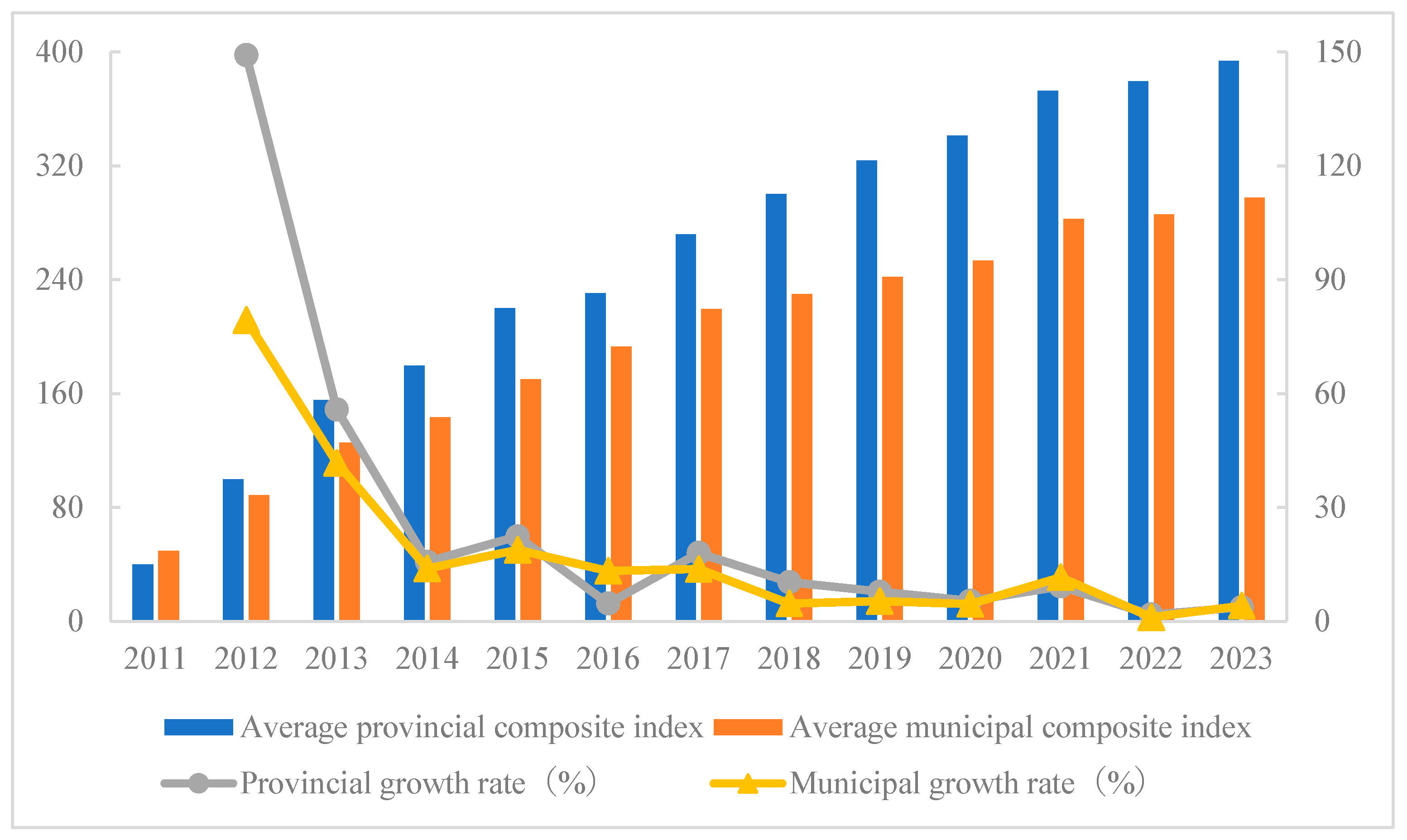

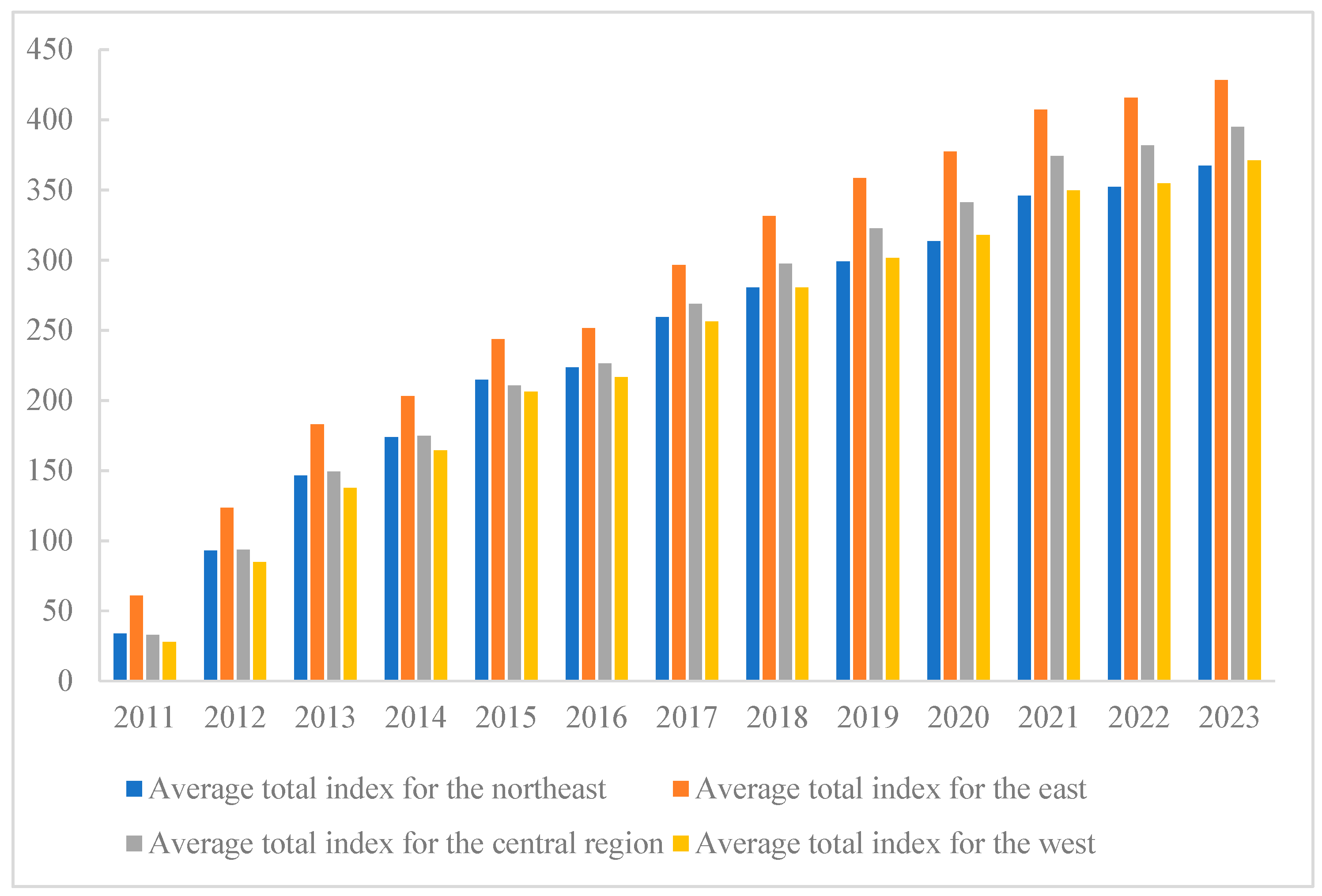

Grounded in the Chinese context and based on a systematic literature review, this study develops an integrated theoretical and empirical analytical framework. The study aims to deeply examine the impact of DFI on farmers’ land transfer decisions and its underlying mechanisms, thereby elucidating the theoretical linkage between the two. Theoretically, the research clarifies the core concepts of DFI and rural land transfer and employs visualization techniques to depict their current developmental status. Subsequently, it constructs a theoretical model that proposes a core hypothesis. DFI significantly positively affects farmers’ land transfer behavior, primarily mediated through two channels: promoting non-agricultural entrepreneurship and enhancing participation in commercial insurance. Empirically, the study integrates macro and micro data to create a combined panel dataset. Utilizing Linear Probability Models (LPMs) and Logit models for baseline regression analysis, the study rigorously tests the causal relationship between DFI and farmers’ land transfer decisions. Furthermore, mediation effect models empirically identify and confirm the significant mediating roles of non-agricultural entrepreneurship and commercial insurance participation in the pathway through which DFI influences rural land transfers. Furthermore, through subsample regression analyses at both the regional and household levels, the article examines the heterogeneity in the effects of digital inclusive finance on rural land transfer.

This study makes significant advances in theoretical depth, mechanism identification, and methodological application, with core contributions manifested in the following aspects:

First, although existing research has extensively examined either the drivers of DFI development or the determinants of rural land transfer, the literature systematically investigating the direct facilitative effect of DFI on farmers’ land transfer decisions and its underlying mechanisms remains scarce. Previous studies predominantly rely on macro-level regional data for correlational analysis, failing to capture individual behaviors at the micro level. Pioneering a micro-level household perspective, this research innovatively integrates large-scale household panel data (CFPS) with regional DFI indices to construct a hybrid panel dataset. This approach precisely identifies and quantifies DFI’s impact on individual farmers’ land-out decisions, effectively overcoming aggregation bias inherent in macro-level studies and addressing the critical gap in micro-level causal evidence.

Second, regarding mechanism revelation, this study transcends the limitations of the conventional literature, which often focuses narrowly on direct financial functions like “enhanced payment convenience” or “improved basic credit access.” Instead, it innovatively proposes and rigorously validates two deeper, transformative transmission pathways: “off-farm entrepreneurship incentives” and “increased commercial insurance participation.” This finding demonstrates that DFI not only improves immediate financial accessibility but, more importantly, fundamentally reshapes farmers’ livelihood strategies and reduces their dependence on land by enabling entrepreneurship and strengthening risk protection capabilities. Consequently, it provides a novel and more explanatory theoretical framework for understanding DFI’s pivotal role in activating land factor markets.

Finally, deeply rooted in China’s institutional context of rural financial system reform and the “separation of land ownership rights, contract rights, and management rights”, this study’s policy significance extends beyond empirically confirming DFI’s efficacy in activating land markets and supporting agricultural-scale operations. Leveraging precise insights from micro-level mechanisms and spatial effects, it proposes a systematic, actionable, and differentiated policy framework—offering a Chinese approach to overcoming current land transfer bottlenecks.

This study focuses on investigating the impact of DFI on rural land transfer and its underlying mechanisms. The specific arrangement is structured as follows: First, it establishes the strategic significance of land transfer for agricultural and rural modernization and rural revitalization, introduces the connection between DFI and rural land transfer practices, and outlines key research questions and potential innovative contributions. The

Section 2 systematically synthesizes and critiques existing research on both rural land transfer and DFI. It identifies gaps, revealing their potential theoretical linkages. The

Section 3 defines core concepts and employs detailed data analysis to depict the actual landscape of DFI development and rural land transfer in China. The

Section 4 integrates relevant theories to analyze the theoretical pathways and transmission mechanisms through which DFI influences rural land transfer and derives specific research hypotheses. The

Section 5 details data sources and processing procedures and constructs the econometric model for analysis. The

Section 6 presents baseline findings, comprehensively addresses endogeneity using instrumental variables, and analyzes robustness checks. The

Section 7 employs mediation effect models to validate the proposed causal pathways. The

Section 8 examines variations in effects across different regions and household types. The

Section 9 analyzes spillover effects of digital financial inclusion on land transfer. The

Section 10 summarizes key findings and derives actionable policy recommendations grounded in empirical evidence and real-world contexts.

4. Hypotheses Development

DFI represents a deep integration of fintech and inclusive finance principles, fundamentally transforming the logic of rural land resource allocation. This approach leverages mobile payments, internet banking, and blockchain technologies to overcome geographic barriers and credit assessment limitations inherent in traditional financial services [

12,

69]. By delivering cost-effective financial solutions to small-scale entities historically excluded from formal financial systems, this model enhances operational efficiency while exerting systemic influence on rural land transfer markets. Through agricultural big data integration, DFI precisely identifies farmers’ financing needs during transitions to non-farm employment and agricultural scaling operations. This targeting provides vital capital supporting rural land transfers, enabling market-driven reallocation of fragmented land resources.

Regarding financial inclusion, DFI addresses traditional institutions’ service gaps in rural areas. Physical branch scarcity and limited risk assessment methods have historically subjected farmers to severe credit constraints. Digital solutions counter this through remote identity verification, multidimensional credit profiling, and real-time transaction monitoring, significantly improving financial accessibility [

70]. This enhanced accessibility generates dual effects: First, it directly enables productivity-enhancing investments in transferred land parcels. Second, it strengthens farmers’ risk tolerance in rural land transfer markets by alleviating liquidity constraints [

71]. Importantly, improved financial accessibility interacts synergistically with information environment optimization. Rural land transfers constitute contractual processes where information asymmetry in decentralized smallholder economies has long impeded market development through high transaction costs [

72]. DFI platforms substantially reduce search and matching costs for both suppliers and demanders in rural land transfer through efficient information aggregation and dissemination mechanisms [

73], consequently increasing transaction probability. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

The development of DFI can promote rural land transfer.

As previously established, DFI’s core value lies in delivering cost-effective financial services to historically excluded farmers through digital technologies. This innovative model activates non-agricultural entrepreneurship through dual pathways [

74]: First, by integrating agricultural big data to build precision risk models, DFI significantly alleviates entrepreneurial credit constraints [

27]. Digital credit assessment mitigates traditional lenders’ collateral-based restrictions, enabling entrepreneurs to overcome initial capital barriers. Second, mobile-enabled information networks dismantle rural “information silos.” DFI is claimed to enhance financial literacy through its integration of accessible educational tools, real-time information dissemination, and behavioral reinforcement mechanisms. Digital platforms embed interactive resources like budgeting apps and investment simulators, enabling self-paced learning of financial concepts such as compound interest. Simultaneously, DFI reduces information asymmetry by delivering instant market updates and product comparisons, fostering informed decision-making aligned with behavioral economics principles. Additionally, features like transaction tracking, automated savings goals, and repayment reminders cultivate financially responsible habits, with empirical evidence linking frequent DFI engagement to improved credit management. By transforming passive knowledge into active skills, DFI bridges theoretical literacy and practical application. Entrepreneurial policies, market intelligence, and financial literacy now reach farmers efficiently via digital platforms, drastically reducing information search costs [

75,

76]. This optimized information environment cultivates commercial awareness while enhancing opportunity recognition capabilities [

77,

78], empowering farmers to transition from passive adaptation to proactive market engagement. Significantly, entrepreneurial activities require substantial labor reallocation to non-agricultural sectors, reducing agricultural labor input. The resulting income substitution effect diminishes survival dependency on landholdings. Moreover, DFI’s proliferation stimulates regional economic growth, generating non-farm employment that accelerates labor migration [

79]. These structural transformations reposition land as a tradable production factor.

Hypothesis 2.

The development of DFI can increase the probability of farmers engaging in non-agricultural entrepreneurship, thereby promoting rural land transfers.

The deep application of digital technologies has substantially reduced barriers to rural financial service access [

33,

69]. Specifically, mobile payment systems and online credit facilities enable farmers to conveniently secure land improvement financing. Concurrently, blockchain-powered rural land transfer platforms significantly enhance transactional transparency while mitigating trust deficiencies inherent in traditional models. This optimized financial ecosystem has catalyzed innovative products—including land mortgage loans and transfer performance insurance—while establishing institutional safeguards for large-scale land management. Crucially, advancing financial inclusion is simultaneously restructuring risk management frameworks [

30]. The Internet Plus model transcends physical branch limitations, enabling commercial insurance penetration into remote areas via mobile interfaces [

75]. Supported by big data analytics, insurers achieve operational cost reduction through precision risk assessment while developing customized products for differentiated protection needs.

Furthermore, widespread digital platform adoption is fundamentally transforming farmers’ risk perceptions. Continuous dissemination of financial literacy through user interaction mechanisms steadily enhances economic decision-making capabilities [

80]. Abundant product information and peer reviews dramatically lower information search costs, gradually correcting traditional insurance misconceptions. This cognitive evolution effectively alleviates information asymmetry-induced insurance participation reluctance [

81], encouraging proactive use of commercial insurance for livelihood risk management [

82]. Notably, land’s dual identity as both economic asset and social safety net has historically positioned it as a core buffer against unemployment, retirement insecurity, and livelihood risks. This protective characteristic frequently constrains rural land transfer decisions [

83]. Particularly when non-agricultural employment proves unstable, farmers preferentially retain land as a survival safeguard [

50]. As commercial insurance networks mature, their expanding coverage of pension, health, and unemployment risks progressively substitutes land’s protective functions. With pension pressures alleviated by retirement insurance and medical burdens shifted through health coverage, land’s social security utility continuously diminishes. This functional substitution profoundly reshapes risk calculus: insured farmers reduce land-dependent security reliance in favor of generating property income through rural land transfers. Thus, DFI effectively addresses core institutional constraints by establishing an endogenous mechanism where insurance supplants land as protection—creating essential preconditions for market-based agricultural land allocation.

Hypothesis 3.

The development of DFI can increase farmers’ participation in commercial insurance, thereby promoting rural land transfers.

5. Empirical Strategy

5.1. Data Sources

This study uses longitudinal data from six waves (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022) of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) database, which is administered by the Institute of Social Science Survey at Peking University. As a nationally representative household survey, the CFPS comprehensively tracks Chinese households across multiple dimensions including household composition, educational attainment, employment status, income-expenditure structures, asset ownership, agricultural/industrial operations, land use dynamics—with particular attention to rural land transfers—and social security participation. Using a stratified random sampling framework, the survey covers all 31 province-level administrative divisions in China to ensure robust representativeness at the national, provincial, and community levels.

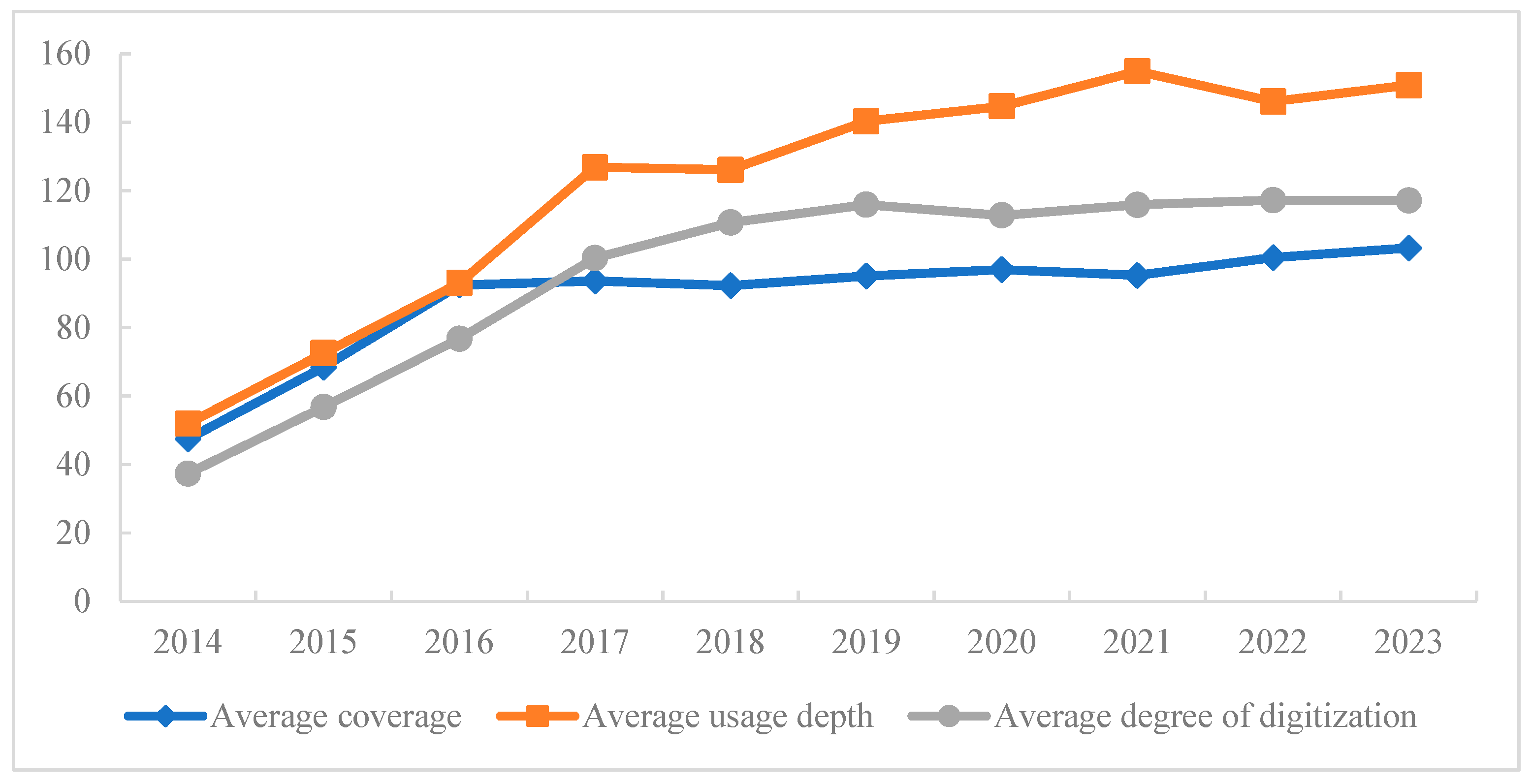

DFI development is measured using the authoritative Peking University Digital Financial Inclusion Index, co-developed by Peking University’s Digital Finance Research Center and Ant Group. The index evaluates DFI through three primary dimensions: coverage breadth, usage depth, and digitization level. These dimensions are further decomposed into 33 granular indicators that span account penetration, payment services, credit utilization, insurance adoption, and mobile service accessibility. Leveraging Ant Group’s real-time transactional data, the index establishes an objective evaluation framework distinguished by its extensive geographical coverage, methodological rigor, and comprehensive indicator selection. Widely recognized as the definitive metric for China’s digital financial inclusion landscape, it provides scientifically valid and empirically robust measurement for scholarly investigation.

We use stata18.0 to process and analyze the data. Data processing followed sequential procedures: First, we retained only households possessing farmland during surveyed years. Second, provincial-level DFI indices were matched to corresponding survey years. Third, observations with missing values or statistical outliers in core variables—particularly rural land transfers, the DFI index, and key covariates—were systematically excluded. Finally, cross-sectional datasets were longitudinally merged to construct an unbalanced panel. The resultant dataset includes 41,755 household-year observations spanning six survey waves: 2012 (The sample size is 7793), 2014 (The sample size is 7702), 2016 (The sample size is 8004), 2018 (The sample size is 7717), 2020 (The sample size is 5615), and 2022 (The sample size is 4924). The data cover households from all 31 province-level divisions across mainland China.

5.2. Empirical Model

To examine the impact of DFI on rural land transfers, this study constructs the following model and establishes a mediation effect model:

In this model, i denotes the household, j denotes the province where the household is located, and t denotes the survey year. Land_Transferijt represents the dependent variable, indicating the land transfer decision of the i-th household in province j in year t. lg_Indexjt represents the core explanatory variable, indicating the level of DFI development in province j in year t. Xijt are household-level control variables. Wjt are provincial-level control variables. νt is the year fixed effect. μi is the household fixed effect. θj is the provincial fixed effect. And εijt is the random disturbance term. Additionally, Mijt represents the two mediating variables of interest in this study, including non-agricultural entrepreneurship and participation in commercial insurance. The coefficient α1 in Equation (1) represents the total effect of DFI on rural land transfer, the coefficient β1 in Equation (2) represents the effect of DFI on the mediator variable Mijt, and the coefficient λ2 in Equation (3) represents the effect of the mediator variable on rural land transfer.

The specific definitions of the relevant variables are provided below.

Land_Transfer: Rural land transfer refers to the process where farm households retain ownership and contractual rights to their contracted cultivated land, yet transfer management rights to new-type agricultural operation entities through market-oriented contractual arrangements. This phenomenon is primarily measured by whether micro-level farm households have participated in land transfer activities. This binary dummy variable measures participation in rural land transfers at the household level. It is assigned a value of 1 if the household engaged in compensated rural land transfer activities during the survey year, as determined by affirmative responses to the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) Land Module questionnaire item “Have you leased your land to others?” This operational definition explicitly excludes informal rural land transfers among relatives and friends as well as non-agricultural land conversion activities. Cases without such market participation receive a value of 0.

lg_Index: Digital financial inclusion (DFI) utilizes digital technologies to fundamentally transform financial service delivery models. Through product innovation and process optimization, it transcends traditional constraints, expanding the accessibility and efficiency of financial services to address developmental imbalances and gaps. Its progression represents a pivotal mechanism for advancing rural development through financial empowerment. In this study, the Peking University Digital Financial Inclusion Index is employed to measure the developmental level of digital financial inclusion. The original index, developed by Peking University’s Digital Finance Research Center in collaboration with Ant Group, is the Peking University Digital Financial Inclusion Index. The index comprehensively measures regional DFI development across three key dimensions: coverage breadth, usage depth, and digitization degree, measured by mobility and affordability. To mitigate the effects of heteroskedasticity and skewed distribution, the original index values were transformed by adding one and then taking the natural logarithm. The resulting variable reflects the regional penetration level of digital financial services, where a higher value indicates a more advanced level of DFI development in the area.

nonagricultural_entrepreneur: The theoretical framework of this study postulates that nonagricultural entrepreneurship is a key channel through which DFI influences rural land transfers. Non-agricultural entrepreneurship refers to the creation, operation, and expansion of economic enterprises outside the agricultural sector, particularly in rural areas. It encompasses innovative and risk-bearing activities that leverage local resources (e.g., water, woodlands, skilled labor, and infrastructure) to engage in manufacturing, services, trade, tourism, and agro-processing. Farmer land transfer decisions are fundamentally shaped by the reallocation of household labor toward non-agricultural activities, representing a core aspect of joint household decision-making. Household laborers make these non-agricultural reallocation decisions by holistically evaluating their own endowments alongside those of other family members, ultimately aiming to maximize collective household welfare. Consequently, this study incorporates a household-level dummy variable for nonagricultural entrepreneurship. Households engaged in individual or private business ventures are designated as nonagricultural entrepreneurial households and coded as one, with all other households assigned a value of zero.

lg_commercial_ins: Commercial insurance refers to risk management products offered by private-sector insurance companies, distinct from government-mandated social insurance programs. It operates on a voluntary basis where policyholders pay premiums in exchange for financial compensation against specified risks. Purchasing commercial insurance can alleviate psychological constraints on farmers, such as their reliance on land as a primary retirement safeguard and their perception of land as an essential safety net against risks associated with non-agricultural employment. This study employs the continuous variable of commercial insurance expenditure to capture household participation in commercial insurance markets. This measure is derived from the household expenditure module of the CFPS survey. It utilizes the survey item that asks about the total amount spent on commercial insurance purchases during the previous year. To address concerns related to heteroskedasticity, skewed distribution, and the presence of zero expenditures, the original insurance expenditure value undergoes a transformation where one is added before applying the natural logarithm.

Control variables: This study’s analysis systematically integrates control variables at multiple levels to rigorously mitigate potential omitted variable bias. Previous research robustly demonstrates the significant influence of household characteristics on rural land transfer behaviors. Given the distinctive nature of agricultural production, where the household constitutes the fundamental production unit, household size directly reflects potential agricultural production capacity. Simultaneously, overall household income levels significantly impact decisions regarding continued engagement in agricultural activities. Furthermore, the household head usually makes decisions about agricultural operations and management. Their gender, age, and educational attainment play critical roles in shaping rural land transfer choices. To bolster the reliability of our findings, this study therefore incorporates key household-level controls: total household size, aggregate household income, and the gender, age, and educational level of the household head. Data for all household-level control variables originate directly from the CFPS questionnaire. Recognizing that rural land transfer decisions represent resource allocation behavior intrinsically embedded within specific institutional contexts, provincial economic scale fundamentally shapes the opportunity structure for non-agricultural employment and entrepreneurship. Concurrently, the intensity of fiscal resource allocation directly influences the quality of rural infrastructure provision, and natural disaster risks significantly constrain farmer land disposition strategies. To precisely isolate the net effect attributable to DFI, this study consequently introduces provincial-level control variables capturing regional gross domestic product, total fiscal budget expenditures, and monetary losses due to natural disasters. Data for all provincial-level controls are sourced exclusively from the officially published China Statistical Yearbook. Following standard practice to normalize distributions, these provincial variables are incorporated into the econometric model after logarithmic transformation. Descriptive statistics for all major variables in the article are shown in

Table 1.

8. Heterogeneity Analysis

Having established the robust promotional effect of DFI on rural land transfer and its underlying mechanisms, and considering the well-documented regional disparities in China’s development, this study further investigates the spatial heterogeneity and economic gradient characteristics of this effect. The heterogeneity analysis presented in

Table 7 reveals significant regional divergence in the impact of DFI on rural land transfer. Grouped regressions based on the Hu Line show that DFI development significantly and positively affects rural land transfer in provinces southeast of the line. In contrast, the coefficient for provinces northwest of the line is 0.021 and is not statistically significant. This pattern primarily stems from differences in regional foundational conditions. Provinces in the southeast benefit from dense digital infrastructure and mature rural land transfer markets, which systematically support the risk management functions and resource allocation efficiency of digital financial tools. Conversely, northwestern provinces are subject to dual constraints: a digital access gap and underdeveloped land transaction systems. These constraints offset the benefits of financial technology due to high transaction costs. Furthermore, the disparity in human capital endowment exacerbates this differentiation. Farmers in the southeast have a higher average level of education than their counterparts in the northwest, enabling them to leverage financial services more effectively to develop non-agricultural entrepreneurial capabilities. This enhanced capability, in turn, facilitates the reallocation of land resources.

Along the economic development dimension, DFI exhibits a strong positive impact on rural land transfer in high-GDP regions, whereas a statistically insignificant negative trend is observed in low-GDP regions. This divergence arises because developed regions possess robust industrial ecosystems and well-established property rights protection. These factors allow DFI to more easily increase land liquidity by empowering entrepreneurs and through the insurance substitution channel. In contrast, underdeveloped regions suffer from a scarcity of non-agricultural employment opportunities and inadequate rural land transfer mechanisms. In these contexts, the adoption of financial technology may inadvertently reinforce farmers’ reliance on land for its traditional security function.

This study further investigates the heterogeneous impact along the household income gradient. The results reveal that the promotional effect of DFI on rural land transfers exhibits a significant inverted U-shaped distribution pattern. As presented in

Table 8, the regression coefficient for the low-income group is 0.156 and statistically significant at the 10% level. The coefficient for the middle-income group climbs to 0.213 and achieves significance at the 5% level. In contrast, the coefficient for the high-income group retreats to 0.196, remaining significant at the 10% level. This divergent pattern originates from variations in structural constraint across income strata. Middle-income households, benefiting from moderate capital accumulation capacity and risk tolerance, demonstrate the highest effectiveness in transforming digital financial services into capital for non-agricultural entrepreneurship. This efficient conversion significantly facilitates the release of land resources. Low-income households, despite possessing strong entrepreneurial aspirations, confront dual barriers: deficient digital skills and inadequate social safety nets. These constraints prevent financial resources from surpassing the threshold for productive investment. Meanwhile, high-income households exhibit diminishing marginal sensitivity to inclusive finance. This reduced responsiveness stems from land assets constituting a smaller share of their overall portfolio and their established channels for non-agricultural income.

9. Further Analysis: Spatial Spillover Effects

The spatial spillover effects of digital financial inclusion on rural land transfer fundamentally stem from the spatial externality of financial technologies and cross-regional mobility of production factors. The network effects of digital financial infrastructure transcend administrative boundaries, enabling the digital financial capabilities of neighboring provinces to directly influence local markets through technological diffusion [

52]. The cross-regional compatibility of technologies such as mobile payments and blockchain-based notarization reduces connectivity costs for interprovincial land information platforms, fostering synergistic technological benefits. Simultaneously, digital credit platforms restructure capital flow pathways, attracting investments from adjacent provinces into local land transfer markets and triggering cross-jurisdictional reallocation of production factors. Crucially, provincial policies exhibit spatial interdependence, as regional digital finance initiatives generate multiplicative effects through institutional emulation. Consequently, digital financial inclusion development not only impacts land transfer behavior within a province but also radiates to neighboring regions, accelerating market integration. But traditional models neglecting this spatial linkage systematically underestimate digital finance’s policy efficacy. Research on this phenomenon reveals new mechanisms through which digital finance influences land resource allocation and provides critical policy insights for dismantling administrative barriers and establishing a unified national land market.

This study constructs the provincial land transfer rate (Land_T) based on six waves of panel data (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2022) covering 41,755 rural households across China’s 31 provinces. The computation involves aggregating micro-level land transfer decisions at the province-year level, specifically calculating the percentage of households engaged in land transfer relative to each province’s total surveyed households annually. This procedure ultimately yielded a balanced provincial panel dataset comprising 140 valid observations. This study adheres to the Queen contiguity criterion to construct the spatial weights matrix, enabling the derivation of the core explanatory variable—the spatially lagged digital inclusive finance index (W_lg_Index). The empirical framework employs the SDM that incorporates year fixed effects to control for macroeconomic cyclical shocks while introducing provincial control variables including per capita GDP and fiscal expenditure to effectively mitigate omitted variable bias.

Regression results from the SDM in

Table 9 demonstrate robust spatial spillover effects. After controlling for key covariates, the core explanatory variable W_lg_Index shows a statistically significant coefficient of 0.670 at the 1 percent level. The regression results from the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) provide compelling evidence of significant spatial spillover effects in the relationship between digital financial inclusion and rural land transfer. Therefore, the development of digital financial services in a province not only influences its own land transfer behavior but also exerts a notable impact on neighboring provinces. This spatial dimension must be integrated into policy frameworks to harness the full potential of financial technologies in promoting rural land market development.

10. Conclusions and Implications

10.1. Conclusions

This study examines the impact of DFI on rural land transfers using theoretical and empirical approaches. Building on a review of the relevant literature and the construction of a theoretical framework, we utilize pooled panel data formed by matching six waves (2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2022) of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) with corresponding provincial DFI indices. Using Linear Probability Models (LPMs), Logit models, and mediation effect models, we conduct empirical tests to thoroughly analyze the influence of DFI on farmers’ decisions to transfer out land and its underlying mechanisms. Additionally, this study examines the heterogeneous nature of this impact across regions, GDP levels, and household income tiers. The principal findings are as follows:

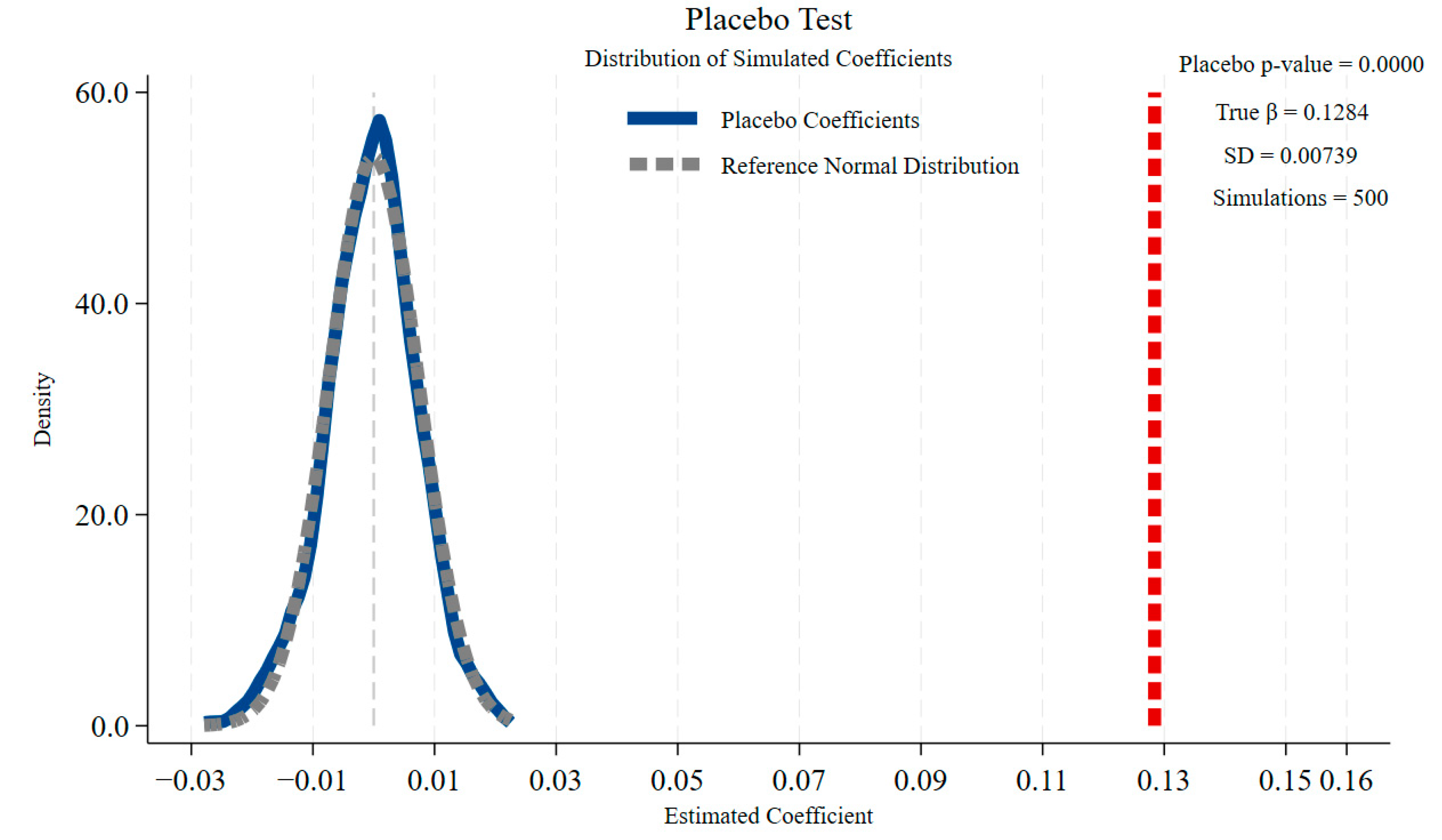

First, DFI significantly promotes rural land transfers. Benchmark regression results show that an increase of one unit in the DFI index raises the probability of rural land transfer by an average of 12.8 percentage points. This effect is statistically significant at the 1% level. Consistency across robustness checks and instrumental variable estimations confirms the reliability of this finding.

Second, non-agricultural entrepreneurship and commercial insurance participation act as significant mediating channels through which DFI influences rural land transfers. The development of DFI enhances farmers’ propensity for non-agricultural entrepreneurship and commercial insurance uptake. This effectively substitutes for the traditional role of land in providing economic security, employment, and old-age support, significantly incentivizing farmers to transfer out land.

Third, the impact of DFI on rural land transfers varies significantly across regional, economic development, and household income dimensions. Geographically, a positive effect is observed in areas southeast of the Hu Line, while the impact proves statistically insignificant in regions northwest of the line. Economically, DFI strongly promotes rural land transfers in regions with high GDP, whereas in regions with low GDP, its effect manifests as a non-significant negative trend. Regarding household income, although DFI significantly encourages rural land transfers across all income groups, the magnitude of this promotional effect varies considerably among low-income, middle-income, and high-income households. Middle-income households, characterized by balanced capital accumulation capacity and moderate risk tolerance, exhibit the greatest efficacy in converting digital financial services into capital for non-agricultural enterprises, thereby substantially accelerating land resource liberation. Low-income households, despite strong entrepreneurial motivation, face dual barriers of inadequate digital literacy and insufficient social protection, which impede financial resources from crossing the productive investment threshold. Meanwhile, high-income households demonstrate diminishing marginal responsiveness to inclusive finance, as land assets constitute a smaller proportion of their wealth portfolio and they possess established non-agricultural income channels.

Finally, digital inclusive finance demonstrates a significant positive spatial spillover effect on rural land transfer. After controlling for key covariates, a one-unit increase in the digital financial development level of neighboring provinces leads to a 0.67 percentage point rise in the local province’s land transfer rate. This suggests that traditional models underestimate policy effectiveness by overlooking inter-provincial linkages, underscoring the necessity of employing a spatial econometric framework.

10.2. Implications

Based on the research findings, this study makes the following recommendations:

First, institutional coordination between the DFI and rural land system reforms should be deepened to enhance the efficiency of land resource allocation through diversified financial innovations. Local governments can foster tripartite collaboration among government bodies, financial institutions, and farmers. This collaboration should encourage financial institutions to develop tailored credit and insurance products addressing farmers’ diverse needs, particularly addressing startup capital constraints and social security gaps following rural land transfers. Exploring pledge financing models using anticipated rural land transfer income rights could enable farmers to leverage digital land contracting certificates for entrepreneurial funding. Concurrently, developing protective insurance products covering multiple risks during the transition to non-agricultural employment is essential. At the national level, establishing a dedicated risk compensation mechanism to support county-level inclusive agricultural lending is recommended. This mechanism should incentivize financial institutions to integrate rural land transfer platform data into risk models to optimize credit strategies dynamically, ultimately creating a virtuous cycle where financial resources activate land assets and industrial upgrading fuels rural development.

Second, strengthen the targeted support capacity of DFI for non-agricultural employment and entrepreneurship to systematically supplant land’s traditional security functions. Provincial governments should integrate employment services with financial resources to establish integrated smart service platforms. These platforms should offer farmers transferring land comprehensive support, including skills training, job matching, and entrepreneurial financing. It is crucial to implement a tiered credit policy for entrepreneurs that offers preferential loan terms to farmers who complete rural land transfers and pass project evaluations. Developing mobile applications for migrant workers to facilitate precise job matching and streamlined access to microcredit is also necessary. Simultaneously, promoting insurance innovation for land income conversion pension products allows farmers to convert a portion of transfer income into long-term security benefits. Providing differentiated government subsidies for low-income participants is vital to fundamentally eroding farmers’ dependence on land-based security.

Third, implement tiered capacity-building initiatives and prioritize infrastructure development to overcome region-specific bottlenecks. To enhance human capital, local governments should partner with financial institutions to launch village-level financial literacy programs. Utilizing farmer-centric training systems and intelligent tutoring tools should prioritize financial risk education and digital skill development for less-educated groups. A complementary step is developing user-friendly inclusive finance terminals embedded with risk control modules. In terms of infrastructure, the deployment of next-generation communication networks in underdeveloped regions is a top priority. Promoting mobile service terminals addresses financial access issues in areas lacking reliable power and communication coverage. It is imperative to reduce digital access barriers through terminal subsidies and preferential tariffs, as well as to establish emergency communication safeguards for challenging terrains. Concurrently, advancing integrated land consolidation and linked development of specialized industrial parks in lagging counties promotes high-quality local employment for the transitioning workforce.