State-Led Tourism Infrastructure and Rural Regeneration: The Case of the Costa da Morte Parador (Galicia, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Tourist Motivations and Impacts of the Parador Costa da Morte

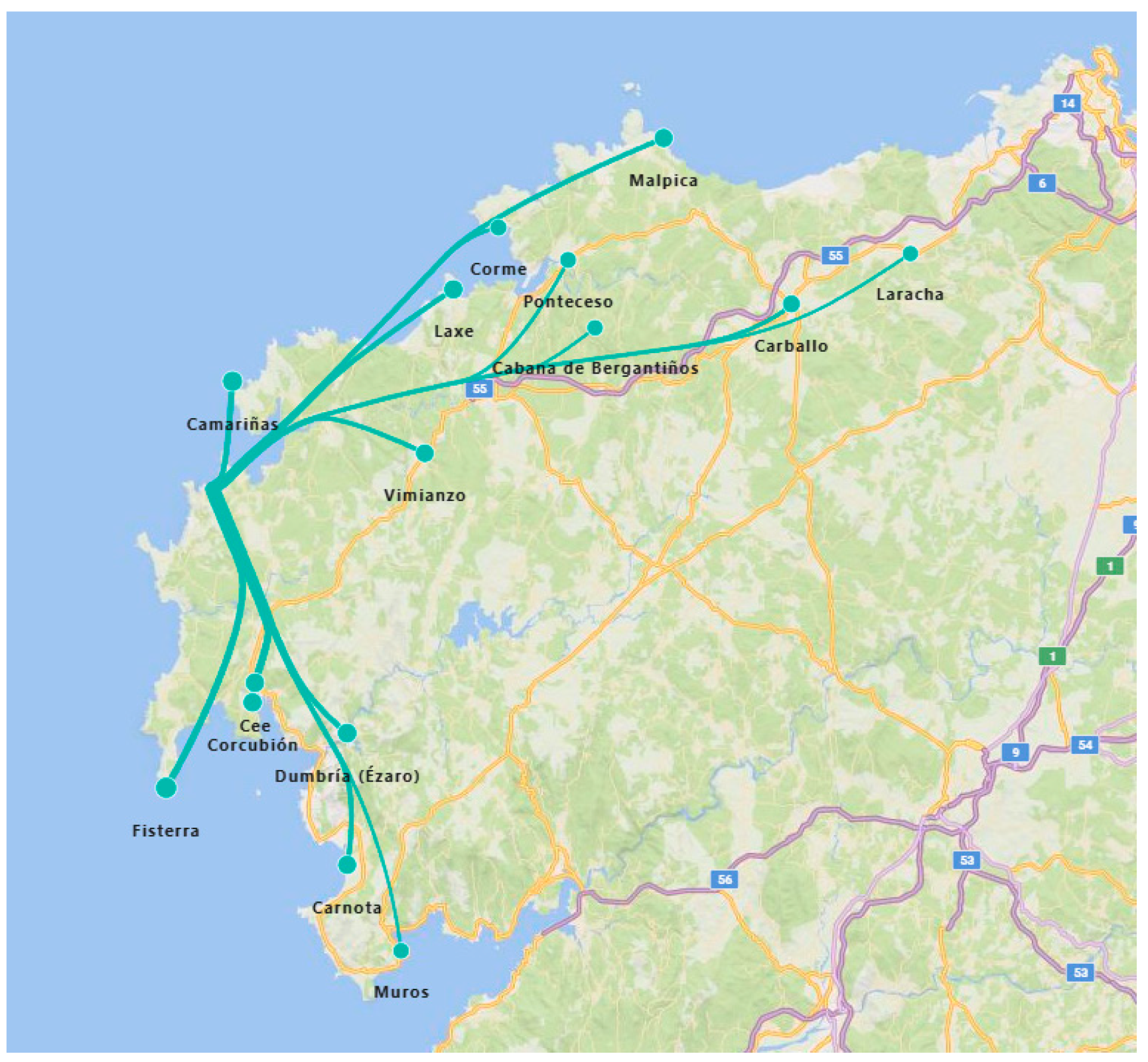

3.1. The Costa da Morte Parador

3.2. Tourist Motivations

3.3. The Multiplier Effect of the Parador Costa da Morte for the Region

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Del Pozo, P.B. Obstacles and stimuli to the integration of the regressive Atlantic regions. Investig. Geogr. 2001, 26, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M.; Blom, T. Finisterre: Being and becoming a myth-related tourist destination. Leisure Stud. 2018, 37, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, N. La atracción turística de un espacio mítico: Peregrinación al cabo de Finisterre. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2009, 7, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicero, J.H.; Berghaenel, R.P. Blog Post. Aemetblog. Available online: https://aemetblog.es/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Diz-Otero, I.; González, M.I. Reconstruction of civil society in Galicia: The “Prestige” catastrophe and the Nunca Máis movement. Rev. Estud. Políticos 2005, 129, 255–280. [Google Scholar]

- Sestayo, R.L.; Fernández, E.F.; Giménez, M.N.S. Impacto de la crisis económica en la estructura económico-financiera de Paradores SA. RICIT 2017, 11, 78–98. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-García, J.; Cortés-Domínguez, M.D.C.; Del Río-Rama, M.D.L.C.; Simonetti, B. Influence of brand equity on the behavioral attitudes of customers: Spanish Tourist Paradores. Qual. Quant. 2020, 54, 1401–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Fajardo, V.; Puig-Cabrera, M.; Miguel-Fernández, V.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, I. A Novel Methodology for Evaluating Authenticity Perceptions in Andalusian Paradores Through Machine Learning. Heritage 2024, 7, 7255–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.J.R. Paradores, Pousadas and Habaguanex. Restoration in the public hotel industry. Cuad. Tur. 2015, 35, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aspres, A.L. Monuments converted into hotels: The sacrifice of architectural heritage. The case of Santo Estevo de Ribas de Sil. Pasos Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2017, 15, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crecente, M. Paradores: Past, present and future of the heritage–tourism relationship: The case of the Ribeira Sacra. Estud. Turísticos 2019, 217–218, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Medina, M.L.; Hernández-Estárico, E.; Morini-Marrero, S. Study of the critical success factors of emblematic hotels through the analysis of content of online opinions: The case of the Spanish Tourist Paradors. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 27, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, L.C.; Sanz, J.Á.; Devesa, M.; Bedate, A.; Del Barrio, M.J. The economic impact of cultural events: A case-study of Salamanca 2002, European Capital of Culture. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2006, 13, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, S.; Tyler, B.D.; Kellett, P.; D’Elia, K. The Formula One Australian Grand Prix: Exploring the triple bottom line. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añó Sanz, V.; Calabuig Moreno, F.; Parra Camacho, D. Social impact of a major athletic event: The Formula 1 Grand Prix of Europe. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2012, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Roche, N.; Jones, C.; Munday, M. What is the value of a Premier League football club to a regional economy? Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, C.; Giaccio, V.; Mastronardi, L.; Giannelli, A.; Scardera, A. Exploring the features of agritourism and its contribution to rural development in Italy. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Abdelmoaty, M.A. Impact of rural tourism development on residents’ satisfaction with the local environment, socio-economy and quality of life in Al-Ahsa Region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Wornell, R.; Youell, R. Re-conceptualising rural resources as countryside capital: The case of rural tourism. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, O.D.; Hambira, W.L.; Gondo, R. Agrotourism as peripheral and ultraperipheral community livelihoods diversification strategy: Insights from the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J. Arid Environ. 2023, 212, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togaymurodov, E.; Roman, M.; Prus, P. Opportunities and directions of development of agritourism: Evidence from Samarkand Region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Acosta, E.; Marques-Perez, I.; Segura, B. Spatial-temporal identification of the incidence of tourism in rural population dynamics in the Valencia Region. Econ. Agrar. Recur. Nat. 2020, 19, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable development and rural tourism in depopulated areas. Land 2021, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmo Moriche, Á.; Nieto Masot, A.; Mora Aliseda, J. Economic sustainability of touristic offer funded by public initiatives in Spanish rural areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, A.I.P.; Jamilena, D.M.F.; Molina, M.Á.R.; Olmo, J.C. Rural lodging establishments: Effects of location and internal resources and characteristics on room rates. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson Järnberg, L.; Värja, E. The composition of local government expenditure and income growth: The case of Sweden. Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 1784–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F.; Donia, E.; Mineo, A.M. Agritourism and local development: A methodology for assessing the role of public contributions in the creation of competitive advantage. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Olmos, K.N.; Aguilar-Rivera, N. Agritourism and sustainable local development in Mexico: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 17180–17200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonte, E.; Chiran, A.; Miron, P. Implementing agritourism marketing strategy as tools for the efficiency and sustainable development of rural tourism. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampela, S.; Kizos, T. Agritourism and local development: Evidence from two case studies in Greece. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus; Hardjosoekarto, S.; Lawang, R.M.Z. The Role of Local Government on Rural Tourism Development: Case Study of Desa Wisata Pujonkidul, Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, K.; Singer, R.; Cui, R. Urban and rural tourism under COVID-19 in China: Research on the recovery measures and tourism development. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 718–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baipai, R.; Chikuta, O.; Gandiwa, E.; Mutanga, C.N. A framework for sustainable agritourism development in Zimbabwe. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2201025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Su, Y. New media environment, environmental regulation and corporate green technology innovation: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2023, 119, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Vujko, A.; Gajić, T.; Vuković, D.B.; Radovanović, M.; Jovanović, J.M.; Vuković, N. Tourism as an approach to sustainable rural development in post-socialist countries: A comparative study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability 2017, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husemann, K.C.; Eckhardt, G.M. Consumer deceleration. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 45, 1142–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Klaus, P.; Luong, V.H. Slow tourism: Conceptualization and interpretation—A travel vloggers’ perspective. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The condition of postmodernity. In The New Social Theory Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Sanada, J.; Zhang, W. Toward Sustainable Tourism: An Activity-Based Segmentation of the Rural Tourism Market in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.; Komppula, R.; Kronenberg, C.; Peters, M. Understanding the relationship between push and pull motivations in rural tourism. Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiz, J.A.; De Carlos, P.; Araújo, N. Disclosing homogeneity within heterogeneity: A segmentation of Spanish active tourism based on motivational pull factors. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 30, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.; Lumsdon, L. Slow Travel and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.; Assaf, A.G.; Baloglu, S. Motivations and goals of slow tourism. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F.; Moutela, J.A.; Rodriguez, X.A. Length of stay and sustainability: Evidence from the Schist Villages Network (SVN) in Portugal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F. Gastronomía y hospitalidad: Claves para la satisfacción turística en áreas rurales. Cuad. Tur. 2024, 54, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourist motivation: An appraisal. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowosafe, F.; Akinwotu, O.; Tunde-Ajayi, O.; Omosehin, O.; Osabuohien, E. Push and pull motivation factors: A panacea for tourism development challenges in Oluminrin Waterfalls, Nigeria. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leisure Events 2022, 14, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedmak, G.; Vodeb, K. Which resources should be developed into tourist attractions? The viewpoint of key stakeholders on the Slovenian coast. Dev. Policy Rev. 2025, 43, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J.; Kastenholz, E.; Figueiredo, E.; Da Silva, D.S. Who is consuming the countryside? An activity-based segmentation analysis of the domestic rural tourism market in Portugal. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesić, Ž.; Primorac, V.; Cerjak, M. Push travel motivations as a basis for segmentation of tourists in emerging rural tourism destinations: The case of Croatia. Ekon. Misao Praksa 2022, 31, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Antunes, A.; Henriques, C. A closer look at Santiago de Compostela’s pilgrims through the lens of motivations. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.J.A.; García, M.D.; Leiras, A. Researching links between pilgrimage tourism and rural development: The emergence of Fisterra as a “new end” of the way. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 119, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiriño, R.; Brea, J.A.F.; Vila, N.A.; López, E.R. Segmentación del mercado de un destino turístico de interior. El caso de A Ribeira Sacra (Ourense). PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2016, 14, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism of Galicia (Spain)—Xeodestinos. Available online: https://www.turismo.gal/que-visitar/xeodestinos?langId=es_ES (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Paradores de Turismo de España. Available online: https://paradores.es/es/paradores (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Prista, M. From displaying to becoming national heritage: The case of the Pousadas de Portugal. Natl. Identities 2015, 17, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, S. Pousadas de Portugal: Entre albergue de carretera y parador. Estud. Turísticos 2019, 217–218, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A.; Ledda, A.; Ganciu, A.; Serra, V.; De Montis, S. Recovery of rural centres and “albergo diffuso”: A case study in Sardinia, Italy. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versaci, A. The evolution of urban heritage concept in France, between conservation and rehabilitation programs. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 225, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galician Institute of Statistics–Municipal Data Bank. Available online: https://www.ige.gal/igebdt/esq.jsp?paxina=002001&ruta=index_bdtm.jsp (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- National Statistics Institute of Spain (INE). Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.S.; King, B. The sacred and the profane: Identifying pilgrim traveler value orientations using means-end theory. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists’ intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.H., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Money, A.; Page, M.; Samouel, P. Research Methods for Business; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism of Galicia (Spain)—Register of Tourism Businesses and Activities. Available online: https://aei.turismo.gal/es/rexistro-de-empresas-e-actividades-turisticas (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- National Statistics Institute of Spain (INE)—Experimental Statistics: Measuring Tourism Using Mobile Phones. Available online: https://www.ine.es/experimental/turismo_moviles/experimental_turismo_moviles.htm (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Almstedt, Å.; Lundmark, L.; Pettersson, Ö. Public spending on rural tourism in Sweden. Fennia 2016, 194, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado Ballesteros, J.G.; Hernández, M.H. Promoting tourism through the EU LEADER programme: Understanding Local Action Group governance. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funduk, M.; Biondić, I.; Simonić, A.L. Revitalizing rural tourism: A Croatian case study in sustainable practices. Sustainability 2023, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.R.; Rodriguez, G.R. Disaster tourism: An approach to tourist exploitation of the Prestige disaster in Costa da Morte. Rev. Galega Econ. 2009, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E. Analysing Determinants of Visitor Spending for the Rural Tourist Market in North Portugal. Tour. Econ. 2005, 11, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryglová, K.; Rašovská, I.; Šácha, J.; Maráková, V. Building Customer Loyalty in Rural Destinations as a Pre-Condition of Sustainable Competitiveness. Sustainability 2018, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-B.; Yoon, Y.-S. Segmentation by Motivation in Rural Tourism: A Korean Case Study. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rid, W.; Ezeuduji, I.O.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. Segmentation by Motivation for Rural Tourism Activities in The Gambia. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Institute of Spain (INE)—Tourism Satellite Account of Spain. 2021–2023 Series. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736169169&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735576863 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Romera, A.R.; Lama, A.V.; Ruiz, M.C.P.; Tabales, A.F. Making the city uninhabitable. The impacts of touristification on the commercial environment. Cities 2025, 165, 106080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyódi, K. The spatial patterns of Airbnb offers, hotels and attractions: Are professional hosts taking over cities? Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2757–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Population Density (pop./km2) | Median Age | Aging Index ** | GDP Per Capita (EUR) | Gross Disposable Income Per Capita (EUR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muxía (municipality) | 4380 | 36.1 | 53.3 | 321.8 | 16,475 | 13,820 |

| Costa da Morte (comarca) | 11,1508 | 83.5 | 52.1 | 286.6 | 15,373 | 14,864 |

| A Coruña (province) | 1,128,320 | 141.9 | 48.0 | 166.1 | 23,113 | 18,296 |

| Galicia (region) | 2,703,353 | 91.5 | 48.4 | 172.8 | 21,755 | 17,169 |

| España (country) | 49,077,984 | 95.0 | 44.4 | 112.0 | 23,851 | 23,677 |

| Difference Muxía/Spain | −163.2% | +20% | +187.3% | −30.9% | −41.6% | |

| Difference Costa da Morte/Spain | −12.1% | +17.4% | +155.9% | −35.5% | −37.2% |

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 91 | 44.4 |

| Female | 114 | 55.6 |

| Age | ||

| Under 40 | 63 | 30.7 |

| Between 40 and 60 | 83 | 40.5 |

| 60 and over | 59 | 28.8 |

| Civil status | ||

| Single | 22 | 10.7 |

| Married or partnered | 183 | 89.3 |

| Education | ||

| Junior and secondary | 38 | 18.5 |

| University studies | 96 | 46.8 |

| Master’s and PhD degrees | 71 | 34.6 |

| Current occupation | ||

| Salaried employee | 120 | 58.5 |

| Self-employed | 34 | 16.6 |

| Other circumstances | 51 | 24.9 |

| Monthly income | ||

| Less than EUR 1800 | 43 | 21.0 |

| Between EUR 1800 and EUR 3000 | 89 | 43.4 |

| More than EUR 3000 | 73 | 35.6 |

| Experience | ||

| Repeat | 141 | 68.8 |

| First time | 64 | 31.2 |

| Factors and Items | Mean | Factor Loading | % of Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1: Ethical Immersion | 5.4 | 22.5 | 0.92 | |

| Connecting with the local way of life | 0.87 | |||

| Willingness to consume local products | 0.86 | |||

| Experiencing local customs | 0.85 | |||

| Personal revitalization and self-enrichment | 0.77 | |||

| Peace and tranquility | 0.76 | |||

| Responsible transportation | 0.67 | |||

| F2: Inner Peace and Escape | 3.9 | 18.3 | 0.89 | |

| Enjoying solitude and inner peace | 0.86 | |||

| Spiritual and quiet journey | 0.82 | |||

| Getting away from home | 0.76 | |||

| Experiencing a simpler lifestyle | 0.71 | |||

| Getting a change from a busy job | 0.58 | |||

| F3: Rural Nature and Heritage | 4.5 | 17.9 | 0.90 | |

| Hiking in nature | 0.79 | |||

| Enjoying the local gastronomy | 0.71 | |||

| Visiting a rural environment | 0.67 | |||

| Outdoor experience and nature walks | 0.64 | |||

| Visiting a non-crowded destination | 0.63 | |||

| Traveling around Galicia | 0.58 | |||

| Discovering the region’s heritage culture | 0.55 | |||

| F4: New Experiences | 3.6 | 11.0 | 0.79 | |

| Experiencing something new and different | 0.76 | |||

| Breaking the monotony while spending little | 0.65 | |||

| Discovering as much as possible | 0.63 | |||

| Escaping the extreme heat of other places | 0.50 |

| 1 (n = 76) | 2 (n = 70) | 3 (n = 41) | 4 (n = 18) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation factors | |||||

| Ethical immersion | 6.06 | 5.75 | 3.02 | 6.35 | 0.00 |

| Inner peace and escape | 2.89 | 5.61 | 2.15 | 4.98 | 0.00 |

| Rural nature and heritage | 4.66 | 5.38 | 2.56 | 5.28 | 0.00 |

| New experiences | 3.49 | 4.75 | 2.21 | 2.58 | 0.00 |

| Satisfaction and loyalty | |||||

| Global satisfaction | 6.71 | 6.59 | 6.39 | 6.78 | 0.00 |

| Visiting the Costa da Morte was better than expected. | 5.67 | 5.80 | 3.39 | 6.00 | 0.00 |

| If I had to make this decision again, I would make the same choice. | 6.17 | 6.41 | 3.83 | 6.61 | 0.00 |

| I will recommend this visit to my family and friends. | 6.45 | 6.63 | 4.02 | 6.83 | 0.00 |

| I will visit the region again in the future. | 6.34 | 6.36 | 3.88 | 6.67 | 0.00 |

| I will recommend the parador to my family and friends. | 6.47 | 6.56 | 3.98 | 6.78 | 0.00 |

| Number of visits to other municipalities in the region during the stay | |||||

| 4.86 | 3.87 | 2.24 | 5.67 | 0.00 | |

| Average daily expenditure (EUR) | |||||

| 162.3 | 144.5 | 132.2 | 162.1 | 0.07 | |

| Share of spending in municipalities other than the primary destination (%) | |||||

| 36.6 | 32.5 | 24.6 | 39.7 | 0.00 | |

| Cluster 1 (Responsible Cultural Tourists) | Cluster 2 (Mindful Rural Escapists) | Cluster 3 (Low-Involvement Tourists) | Cluster 4 (Sustainable Rural Explorers) | Total | χ2 (α) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * Age | ||||||

| Under 40 years | 22.4 | 44.3 | 24.4 | 27.8 | 30.7 | 10.83 (0.03) |

| 40–60 years | 44.7 | 34.3 | 39.0 | 50.0 | 40.5 | |

| 60 or more years | 32.9 | 21.4 | 36.6 | 22.2 | 28.8 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 61.8 | 47.1 | 53.7 | 66.7 | 55.6 | 4.18 (0.24) |

| Male | 38.2 | 52.9 | 46.3 | 33.3 | 44.4 | |

| Education | ||||||

| Below university level | 19.7 | 21.4 | 17.1 | 5.6 | 18.5 | 3.23 (0.78) |

| University degree | 47.4 | 42.9 | 46.3 | 61.1 | 46.8 | |

| Postgraduate education | 32.9 | 35.7 | 36.6 | 33.3 | 34.6 | |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Self-employed | 48.7 | 64.3 | 61.0 | 72.2 | 58.5 | 8.45 (0.20) |

| Employee | 21.1 | 10.0 | 22.0 | 11.1 | 16.6 | |

| Other | 30.3 | 25.7 | 17.1 | 16.7 | 24.9 | |

| Income (EUR/month) | ||||||

| <1800 | 17.1 | 31.4 | 14.6 | 11.1 | 21.0 | 8.88 (0.06) |

| 1800–3000 | 40.8 | 41.4 | 48.8 | 50.0 | 43.4 | |

| >3000 | 42.1 | 27.2 | 36.6 | 38.9 | 35.6 | |

| Tourist trips per year | ||||||

| Once or twice | 15.8 | 28.6 | 26.8 | 22.2 | 22.9 | 5.03 (0.83) |

| Three times | 27.6 | 28.6 | 24.4 | 33.3 | 27.8 | |

| Four times | 22.4 | 17.1 | 22.0 | 16.7 | 20.0 | |

| Five times | 34.2 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 27.8 | 29.3 | |

| * Average daily expenditure (EUR) | ||||||

| <100 | 25.0 | 35.7 | 26.8 | 11.1 | 27.8 | 18.61 (0.02) |

| 100–149 | 21.1 | 15.7 | 41.5 | 33.3 | 24.4 | |

| 150–159 | 23.7 | 27.1 | 24.4 | 33.3 | 25.9 | |

| >200 | 30.3 | 21.4 | 7.3 | 22.2 | 22.0 | |

| Muxía | Costa da Morte | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Beds | No. | Beds | |

| 1-star hotels | 2 | 67 | 14 | 321 |

| 2-star hotels | 1 | 12 | 26 | 818 |

| 3-star hotel | 13 | 658 | ||

| 4-star hotels (Parador Costa da Morte) | 1 | 131 | 1 | 131 |

| TOTAL | 4 | 210 | 54 | 1928 |

| % Parador | 62.4% | 6.8% | ||

| Muxía | Province of A Coruña | Muxía/A Coruña Prov. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 8037 | 2,761,487 | 0.29 |

| 2020 | 5778 | 1,576,838 | 0.37 |

| 2021 | 12,623 | 2,190,561 | 0.58 |

| 2022 | 13,262 | 2,571,590 | 0.52 |

| 2023 | 20,712 | 3,148,696 | 0.66 |

| 2024 | 22,448 | 3,211,399 | 0.70 |

| Var. 2021/19 | 57.1 | −20.7 | |

| Var. 2022/19 | 65.0 | −6.9 | |

| Mean var. (2019–2024) | 22.8 | 3.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Roget, F.; Castro, B. State-Led Tourism Infrastructure and Rural Regeneration: The Case of the Costa da Morte Parador (Galicia, Spain). Land 2025, 14, 1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081636

Martínez-Roget F, Castro B. State-Led Tourism Infrastructure and Rural Regeneration: The Case of the Costa da Morte Parador (Galicia, Spain). Land. 2025; 14(8):1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081636

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Roget, Fidel, and Brais Castro. 2025. "State-Led Tourism Infrastructure and Rural Regeneration: The Case of the Costa da Morte Parador (Galicia, Spain)" Land 14, no. 8: 1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081636

APA StyleMartínez-Roget, F., & Castro, B. (2025). State-Led Tourism Infrastructure and Rural Regeneration: The Case of the Costa da Morte Parador (Galicia, Spain). Land, 14(8), 1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081636