1. Introduction

The safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) has become a major concern for the international community. This growing attention reflects increased awareness of the dual challenges posed by modernization and the critical role ICH plays in supporting cultural diversity and sustainable development. In response, UNESCO and national governments have implemented a range of legal and administrative measures to protect and transmit ICH, helping to preserve many endangered forms of traditional expression. As of October 2024, China has 43 elements inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, along with 1557 items on its National List of Representative ICH and an additional 3610 sub-elements. These span ten categories, including oral traditions, traditional music, theater, and folklore [

1]. These figures demonstrate China’s strong commitment to ICH safeguarding, a position widely recognized internationally. According to UNESCO’s Assistant Director-General for Culture, China currently holds the largest number of entries on UNESCO’s ICH lists [

2].

Many scholars argue that Chinese interventions in ICH policy have been shaped by the discourse established by UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (hereafter “the Convention”) [

3], with domestic policies drawing heavily on UNESCO’s conceptual and normative framework [

4]. Others note that before the Convention was introduced, various countries, including China, had already developed their own approaches to cultural safeguarding. From this perspective, the Convention’s influence should be understood in relation to China’s longer trajectory of cultural policy development [

5]. Although evaluating these debates is not the central task of this article, they raise an important question: to what extent are China’s ICH policy arrangements shaped by the international discourse on ICH safeguarding? Put differently, how deeply has the Convention influenced China’s domestic approach?

This study addresses that question by, first, tracing the evolution of China’s ICH policy arrangements, and second, assessing how these developments relate to the global ICH discourse, especially the Convention. The article proceeds as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical framework;

Section 3 explains the research methodology;

Section 4 offers a historical overview of China’s ICH policy since 1949, with attention to international influences;

Section 5 discusses the findings and situates China’s ICH governance within a broader policy context; and the conclusion summarizes the key insights. Existing studies on China’s ICH policy arrangements have predominantly examined institutional reforms and the influence of international conventions.

While existing studies often focus on institutional reforms and the influence of international conventions, they have paid less attention to how ICH policies are enacted, contested, and reinterpreted in specific local contexts. This study contributes by combining institutional and spatial perspectives. It examines how policy discourse, actor networks, and regulatory frameworks translate into changes in cultural practices and spatial arrangements. Through this place-based lens, the article offers a deeper understanding of how cultural governance is being reshaped in China.

2. Theoretical Review and Analytical Framework

Conventional analyses of policy change often rely on normative frameworks that seek to objectively evaluate shifts in institutional arrangements. Yet, in practice, policymaking is a dynamic and contested process shaped by subjective factors such as actors, discourses, and values [

6]. How problems are defined, goals are formulated, and instruments are chosen frequently depends on political processes and ideational influence [

7]. This perspective has gained traction in cultural policy studies [

8], where the development and implementation of ICH safeguarding policies involve discursive negotiations over objectives, stakeholders, and strategies. As the former Director of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage Section observed, cultural heritage has emerged not only as a field of preservation, but as a distinct policy discourse in its own right [

9]. Against this backdrop, a constructivist theoretical lens is particularly suitable for analyzing the evolution of ICH policy and its implications for heritage landscape governance.

This study adopts Discursive Institutionalism (DI) as its central theoretical approach to examining the development of China’s ICH policy framework. As a key strand within new institutionalism, DI emphasizes the role of ideas and discourse in shaping policy change [

10,

11]. It posits that policy ideas, when articulated through discourse and embedded in institutional settings, can catalyze collective action and transform existing arrangements [

10,

12]. According to Schmidt (2008) [

10], ideas operate at three levels: policy ideas (instrumental strategies), programmatic ideas (framing of problems and goals), and public philosophies (deep normative foundations). Discourse functions as both the medium through which these ideas circulate and the interface through which they interact with institutions [

10]. While DI provides a strong conceptual basis for understanding ideational change, it presents challenges for empirical application, particularly at the institutional level.

To operationalize this dimension, we draw on the Policy Arrangement Approach (PAA) developed by Arts et al. (2000) [

13,

14], which identifies four core dimensions of institutional configurations: policy discourse, actors, resources, and rules. We do not treat PAA as an independent theory but rather as a pragmatic tool for translating DI’s institutional layer into empirical analysis. Given the conceptual overlap between DI’s ideational level and PAA’s “policy discourse” dimension, DI’s policy and programmatic ideas are mapped onto this dimension. Public philosophies, due to their abstract and enduring nature, are excluded from the coding framework. The remaining three PAA dimensions—actors, resources, and rules—help trace how discourse is institutionalized through governance practices. Although not originating from DI, these dimensions provide a systematic means to examine how ideas are embedded within governance structures. Thus, PAA offers a mid-level analytical framework for tracing how discursive shifts correspond with institutional transformation. Though originally developed in the context of environmental policy research [

15], PAA has since been adapted to a range of policy fields including ecological management [

16], public health [

17], and agricultural regulation [

18]. Here, it is adapted to the field of cultural policy.

To examine how institutional change influences place-based heritage governance, we incorporate additional perspectives from spatial planning and landscape studies. Emerging research indicates that discourses, actor configurations, and institutional instruments not only reflect bureaucratic objectives but also shape the spatial logic, symbolic meanings, and governance structures of cultural landscapes [

19,

20]. Drawing on these insights, we reinterpret each PAA dimension through a spatial lens: First, “policy discourse” is analyzed as heritage discourse and landscape narrative [

21,

22,

23], illustrating how cultural policies construct spatial meaning and shape place identity. This includes strategic goals, programmatic frameworks, and normative assumptions. Second, “actors” encompass not only government officials and heritage professionals, but also expert networks and participatory coalitions [

24], underscoring the multi-actor foundations of heritage governance. Third, “resources” are defined as planning instruments, infrastructure, and cultural interventions [

25,

26], capturing how spatial-material assets—such as survey systems, funding schemes, and digital heritage platforms—are mobilized and redistributed. Fourth, “rules” refer to cultural zoning mechanisms and planning regulations [

20,

27], including both formal legislation (e.g., the ICH Law) and procedures or operational routines (see

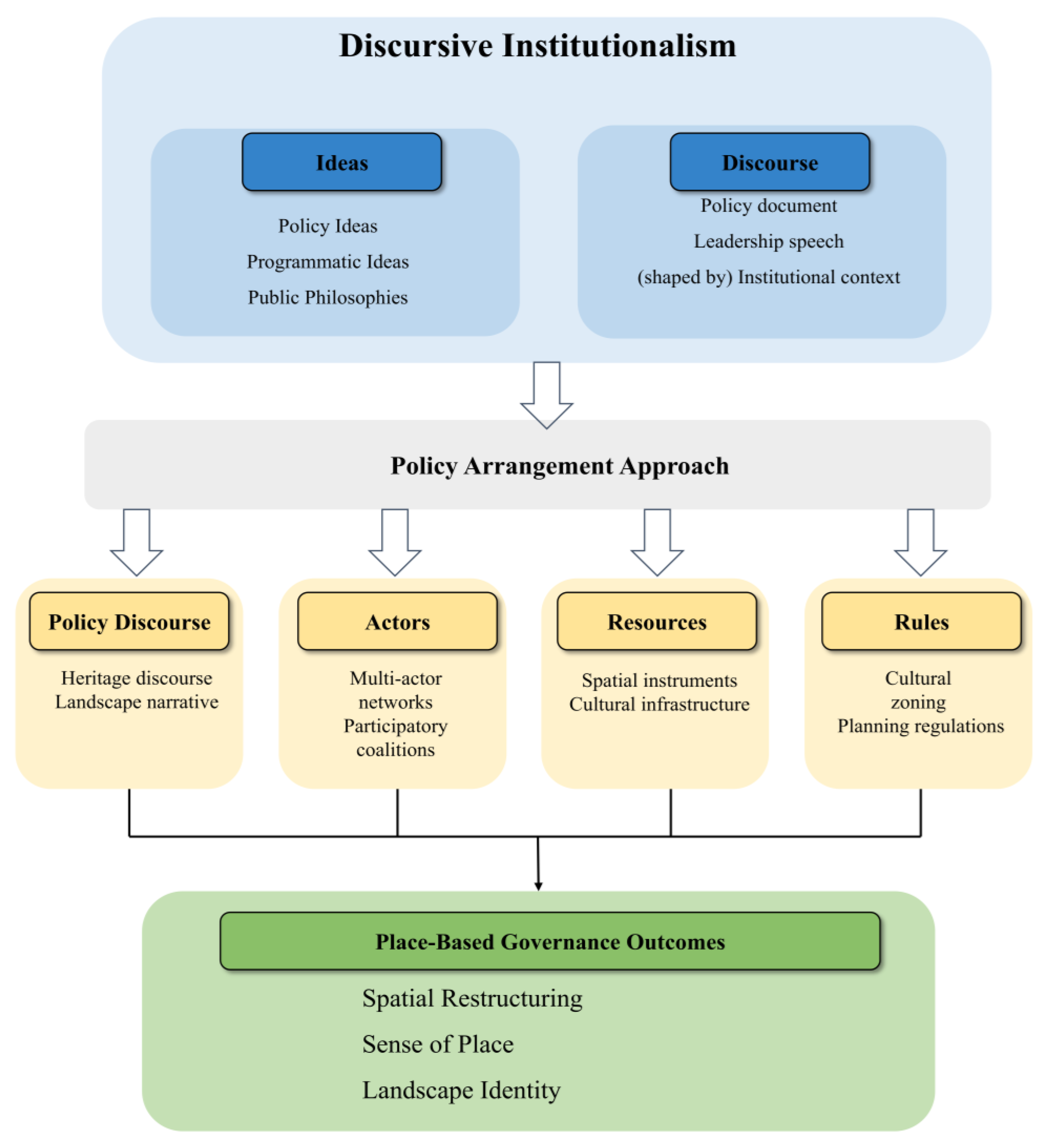

Figure 1), which together embed cultural safeguarding within broader spatial governance frameworks.

Taken together, this integrated framework moves beyond abstract institutional analysis, enabling a grounded examination of how ICH policies are materially and symbolically embedded in place. The sections that follow outline the methodological strategy adopted to trace the evolution of these four dimensions and assess their impact on the reconfiguration of heritage governance in China.

3. Research Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative methodological approach that integrates textual analysis and semi-structured interviews to investigate the institutional and spatial evolution of China’s ICH governance. Grounded in the analytical framework of policy arrangements—defined by four dimensions: policy discourse, actors, resources, and rules—it not only traces institutional change over time but also examines how these shifts take shape in the spatial configuration and governance of ICH-related landscapes. Particular attention is given to the influence of the UNESCO Convention in shaping both the discursive logic and spatial deployment of the ICH policy.

Textual analysis serves as the primary method for capturing changes across all four analytical dimensions. The study systematically reviews policy texts, legal documents, strategic plans, archival materials, and leadership speeches. Coding followed a combined deductive–inductive approach: initial codes were guided by the four dimensions of the policy arrangement framework and subcategories were iteratively refined based on emergent themes from the data. For the dimension of policy discourse, the analysis identifies recurring slogans, action agendas, policy strategies, and semantic framings that construct the meaning and legitimacy of ICH, while also revealing their spatial implications—such as the framing of landscapes, designation of heritage zones, and construction of territorial imaginaries. For the actor dimension, texts are used to map the evolving governance networks and identify emerging stakeholders. The resource dimension draws on official plans and project documents to examine patterns of funding, technical infrastructure, and spatial tools. The rules dimension is assessed through legislation and administrative procedures that shape the implementation and spatial governance of ICH initiatives. To ensure analytical rigor and transparency, the coding process involved independent review by two researchers, followed by consensus discussions to align interpretations. Coding saturation was reached when no new subthemes emerged in subsequent texts.

Unlike open coding approaches commonly used in grounded theory or NVivo-based thematic analysis, this study adopts an interpretive strategy centered on discursive reconstruction and institutional mapping. Rather than treating textual elements as isolated raw codes, recurring slogans, classificatory taxonomies, governance structures, and spatial planning instruments are analyzed as discursive and regulatory artifacts embedded within specific policy contexts. While the majority of documentary sources are drawn from national and provincial authorities, materials from civil society organizations—such as heritage associations and local community reports—were also included where available to supplement the official narrative.

To complement textual analysis, the study incorporates semi-structured interviews with five provincial-level stakeholders, including cultural officials, ICH administrators, and academic experts. The interview protocol was structured around the four analytical dimensions, with particular emphasis on the “actors” and “resources” dimensions. Respondents were asked to describe the evolving configuration of governance actors, their institutional roles, and the mechanisms of resource allocation—such as funding, technical support, and spatial instruments—within ICH projects. Additional questions explored how policy frameworks shape the use of spatial resources, how communities interact with designated ICH zones, and how governance actors perceive the Convention’s influence at the local level. Although the interview sample is small, thematic saturation was achieved due to the specificity and internal consistency of responses across this targeted expert group.

All interview responses were cross-referenced with policy texts to enhance internal validity through triangulation. The analytical findings are derived from converging patterns across documentary evidence and field perspectives. A consolidated list of policy documents and interviewees, organized by source and function, is presented in

Table 1. Full citations for all documentary sources are provided in the reference section, while interview data are directly cited within the main text where relevant.

Through this integrated methodology, the study enables a multi-scalar interpretation of policy discourse, governance configurations, resource mobilization, and spatial regulation—illuminating how ICH policy reform interacts with both institutional dynamics and the material-symbolic landscapes of contemporary China.

4. Evolution of China’s ICH Policy Arrangements

Before the term “intangible cultural heritage” (ICH) entered official usage in China, comparable cultural forms had long been categorized under labels such as “traditional folk culture”, “folklore”, or “ethnic and folk culture” [

28]. From the early years of the People’s Republic of China, these cultural expressions drew considerable attention from both the government and cultural authorities, prompting the implementation of a series of protective measures [

29]. This historical background suggests that the institutionalization of China’s ICH policies was shaped not only by international influences but also by deep-rooted domestic traditions of cultural safeguarding. Based on the distinct features of policy development, the evolution of ICH protection in China can be divided into three stages: first, the phase of traditional cultural protection and reform (1949–1977), corresponding to the founding of the PRC through the pre-reform era; second, the formative stage of folklore and folk culture protection (1978–2003), following the reform and opening-up; and third, the era of systematic ICH policy construction driven by the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2004 to present). This chronological framework provides a structured basis for analyzing the extent to which international ICH discourses have shaped the trajectory of China’s domestic policy arrangements.

4.1. Early Attempts at ICH Policy Arrangements (1949–1977)

4.1.1. Policy Discourse

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, the state adopted a socialist ideological framework that emphasized collective development, political centralization, and cultural reform. Cultural policies during this period were tightly linked to national goals of socialist modernization and ideological alignment. In the early years of the PRC, the main objective of managing traditional folk culture was to reform outdated elements and align cultural practices with the ideological and developmental imperatives of socialism [

30]. The dominant policy discourse centered on political imperatives, particularly the principles of “critical inheritance” and “creative adaptation” of traditional culture. In a 1950 report to the Seventh Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong (in power from 1949 to 1976) emphasized the importance of “carefully and systematically reforming the cultural activities of the old society”, cautioning against both reckless action and excessive delay [

31]. These views provided the ideological foundation for early folk culture protection. Within this framework, Mao’s inscription “Let a hundred flowers bloom, let the old be replaced by the new”, written in 1951 for the newly established Chinese Opera Research Institute, became a widely adopted slogan in cultural reform efforts [

32]. It served both as an ideological guideline and a directive for spatial-cultural restructuring. Traditional opera stages and performance venues were repurposed or newly constructed to embody socialist esthetics, contributing to a spatial reconfiguration of folk performance practices [

33].

In parallel, the state introduced concrete policy instruments to implement this vision. The 1951 Directive on Opera Reform issued by the Government Administration Council instructed local governments to “inherit and promote valuable traditions while eliminating outdated and reactionary elements”, and emphasized the importance of education and propaganda in fostering cultural awareness [

34]. In 1955, the Ministry of Culture launched a nationwide initiative to document and enhance traditional opera repertoires and local theatrical forms, establishing archives to preserve endangered genres. These documentation efforts were often conducted on-site, involving in situ recordings and the identification of culturally significant locations. A 1956 directive further emphasized cultural surveys, documentation, and publishing as essential tools for rescuing endangered cultural resources. Local cultural departments were instructed to establish cultural stations and community art centers [

35], which served as both administrative bases and physical venues for cultural engagement—precursors to the cultural infrastructure that would later support ICH governance.

Together, these discourses and associated initiatives formed an early protection framework aimed at advancing socialist modernization through cultural development. While this process was overwhelmingly state-driven, it laid a foundational institutional and spatial architecture for China’s later ICH governance system. Although early discourses promoted openness and cultural renewal, they simultaneously centralized interpretive authority, positioning the state as the principal arbiter of cultural value. This framing may have constrained space for local or unofficial interpretations of folk tradition.

4.1.2. Actors

During this period, the main actors involved in safeguarding traditional folk culture were state agencies and their affiliated cultural institutions, including the Ministry of Culture, the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles, and local cultural departments. These institutions constituted the central force behind preservation efforts, implementing specific tasks through dedicated bodies. For instance, in 1950, the Ministry of Culture supported the founding of the Chinese Folk Literature and Art Research Association, which focused on the documentation and study of folk literature and art [

36]. In 1956, local governments across China established mass art centers and cultural stations to collect folk art heritage and deliver public cultural services [

37].

Beyond their administrative roles, these institutions also served as spatial anchors of state-led cultural governance. Cultural stations and mass art centers were not only bureaucratic units but also functioned as key cultural nodes embedded within local spatial networks. They hosted exhibitions, performances, and educational activities, transforming everyday places into official cultural venues aligned with socialist ideology [

38].

Certain specialized organizations undertook more focused mandates. The reform of traditional opera, for example, was led by the Chinese Folk Art Research Association and local theater troupes, while traditional crafts were promoted by the Bureau of Arts and Crafts [

39]. Despite these distinctions, the composition of actors during this era remained relatively homogeneous, dominated by government-led public institutions. The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) further disrupted this structure: many cultural organizations were dismantled or merged, and cultural protection activities were suspended. Numerous cultural venues were closed or repurposed [

40]. In addition to institutional upheaval, the period witnessed the persecution of cultural workers and the destruction of traditional practices that would later be recognized as intangible cultural heritage. This rupture erased a portion of the cultural knowledge base critical to future safeguarding efforts.

Nevertheless, the spatial and institutional legacy of these early actors—particularly the embedding of cultural institutions within community life—laid the groundwork for subsequent place-based cultural governance. These actors were not only bureaucratic agents but also spatial agents, shaping the geography of cultural memory and community interaction.

4.1.3. Resources

Resource scarcity posed a significant challenge to cultural preservation during this period. In the early years of the PRC, the country’s fragile economic foundation meant that preservation efforts relied almost entirely on limited state funding. For example, in 1956, the Ministry of Finance allocated CNY 5 million (approximately USD 2 million at the time) for the protection of folk arts—a sum insufficient to support large-scale cultural initiatives across the country.

Despite financial constraints, early preservation efforts made strategic use of limited material and technical resources. Despite financial constraints, early preservation efforts relied on rudimentary technical tools and extensive human labor. Field surveys were conducted with handwritten notes, simple sketches, and limited use of photographic or audio equipment. Grassroots investigators, artists, and local cadres—often working in remote areas under harsh conditions—painstakingly documented traditional music, rituals, and crafts. These campaigns, though constrained by technical limitations, produced extensive cultural records that laid the groundwork for provincial “cultural resource maps” [

33]. Interview data further confirm that these early manual mapping efforts prefigured the digital spatial databases later used for ICH inventorying.

Crucially, these field campaigns temporarily transformed local spaces into zones of cultural documentation. Public halls, classrooms, and even family courtyards were repurposed as makeshift recording sites, laying the groundwork for early forms of spatialized cultural governance. Several interviewees recalled how communal venues—such as schoolrooms or ancestral halls—were adapted for fieldwork activities, symbolizing an emerging awareness of the connection between intangible heritage and its spatial contexts. Though unformalized, these practices symbolized a nascent recognition of the interconnection between intangible cultural practices and physical settings [

38].

Although technical limitations reduced the precision of these preservation efforts, the large volume of collected records became a foundational resource for future ICH safeguarding. More importantly, these practices fostered an ethos of site-based documentation, which later informed cultural zoning, heritage mapping, and community-oriented protection strategies.

4.1.4. Rules

During this period, cultural preservation rules were mainly articulated through ministerial directives and administrative guidelines, as a formal legal framework had not yet been established. For example, the Ministry of Culture’s 1949 directive on New Year’s paintings outlined prescribed themes and technical standards, promoting collaboration between professional artists and folk painters. Similarly, the 1951 directive on opera reform, issued by the Government Administration Council, required local authorities to oversee opera management and promoted mixed operational models such as public–private partnerships or subsidized troupes [

41].

Although not codified into law, these documents functioned as de facto planning rules. They influenced the use of cultural spaces and the regulation of traditional performances, serving as early instruments of “soft regulation” in cultural spatial governance [

20]. By defining acceptable formats and organizational responsibilities, these directives delineated the symbolic and operational boundaries of cultural activity.

As preservation efforts advanced, policies began to show signs of procedural formalization. The Ministry of Culture’s 1961 directive on safeguarding traditional opera and folk arts introduced more detailed mandates, specifying responsibilities for documentation, institutional roles, and evaluation standards [

29]. Though unevenly enforced, such measures acted as operational codes that shaped emerging norms of cultural work at both central and local levels. Some provinces also started issuing localized regulations, marking the early stage of territorially differentiated cultural governance. For instance, some provincial cultural authorities introduced guidelines for cataloging folk arts, anticipating the spatial logic later seen in heritage zoning and ecological cultural protection zones, as noted by one interviewee from a provincial heritage department.

However, the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) severely disrupted this trajectory. Many existing rules and administrative procedures were dismantled, cultural institutions were dissolved or repurposed, and policy attention shifted toward ideological campaigns. As a result, both formal and informal governance mechanisms were suspended or replaced. Despite this rupture, the period laid a procedural foundation for later developments. The use of administrative directives, early spatial planning logic, and rudimentary regulatory tools formed the initial layer of governance practices that would eventually be codified into formal ICH laws, zoning systems, and institutional hierarchies in the decades that followed.

4.2. The Formative Period of China’s ICH Policy Arrangements (1978–2003)

4.2.1. Policy Discourse

In the late 1970s, China entered the Reform and Opening-Up era under Deng Xiaoping (in power from 1978 to 1989), transitioning from a centrally planned to a socialist market economy. This ideological and economic realignment redefined national priorities around modernization, openness, and development, reshaping the orientation of cultural policy and laying the foundation for a new approach to intangible cultural heritage (ICH) safeguarding. Meanwhile, at the international level, the 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage sparked widespread debate over the concept of “cultural heritage”. The Convention’s emphasis on tangible forms—monuments, architecture, archeological sites—largely excluded living traditions such as music, dance, and folk customs [

42]. Critics also challenged the Convention’s reliance on “outstanding universal value”, arguing it privileged Eurocentric norms and sidelined non-Western cultural practices [

4]. These debates catalyzed the emergence of ICH as a distinct heritage category, culminating in UNESCO’s 2001 Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity [

43].

China’s post-1978 cultural policy discourse aligned closely with this international shift [

30]. Following the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee in 1978, Deng Xiaoping reaffirmed the “Double Hundred” policy at the 1979 National Congress of Literary and Art Workers. He emphasized principles such as “serving the people”, “letting a hundred flowers bloom and the old be replaced by the new”, and “integrating Chinese and foreign elements, as well as ancient and modern traditions” [

44]. These formulations preserved ideological continuity with Mao-era slogans while reframing them to support cultural modernization under market reform.

In 1979, the Ministry of Culture, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission, and the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles jointly launched the Collection of Chinese Ethnic and Folk Literature and Arts Project, widely known as the “Great Wall of China’s Ethnic Culture”. This initiative marked a turning point in state-led efforts to institutionalize cultural preservation [

45]. Importantly, the project’s discourse began to frame ethnic minority regions not merely as cultural subjects but as strategically significant heritage territories.

By the 1990s, under President Jiang Zemin (in power from 1989 to 2002), cultural policy was further elevated within the national modernization agenda. Jiang’s “Three Represents” theory explicitly positioned advanced socialist culture as a pillar of development [

34]. Within this framework, ICH was recast as both a symbolic and economic asset. National and provincial policy rhetoric increasingly invoked terms such as “regional cultural branding” and “cultural resource–based development”, linking heritage protection to spatial identity and economic revitalization [

33].

In 2003, the launch of the Chinese Ethnic and Folk Culture Protection Project by the Ministry of Culture and other agencies signaled deeper convergence with UNESCO’s ICH safeguarding paradigm. The project introduced a discursive shift from symbolic recognition to spatial integration, embedding ICH within broader strategies of regional planning and place-based identity construction [

24]. While this alignment reflected global governance norms, it also reinforced a state-centered model of cultural territorialization. By portraying ethnic regions as heritage-rich spaces, policy discourse served national objectives of cohesion and diplomacy—but at the potential cost of marginalizing local interpretations and participatory cultural agency.

4.2.2. Actors

During this period, the network of actors involved in folk culture protection became markedly more diverse. Alongside continued state leadership, semi-official academic institutions, civil society organizations, and grassroots cultural workers all played pivotal roles in safeguarding practices. In 1979, the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles reestablished the Chinese Folk Literature and Art Association (renamed the China Folk Literature and Art Association in 1987), which coordinated the nationwide Collection of Chinese Ethnic and Folk Literature and Arts project [

46]. Similarly, the Chinese Folklore Society, founded in 1983, brought together cultural workers from local art centers and museums to conduct surveys and document local traditions, producing valuable baseline data for preservation [

46]. Reopened mass art centers also actively participated in collecting and archiving ethnic and folk culture [

35].

Beyond their formal mandates, these actors increasingly engaged in what landscape scholars term collaborative governance—including the co-production of heritage knowledge, shared use of public cultural infrastructure, and localized policy mediation [

24]. This marked a shift toward multi-actor cultural planning, where scholars, artists, officials, and communities jointly negotiated the meaning and boundaries of cultural value. As one interviewee described, cultural station staff and art center workers facilitated on-the-ground data collection, while scholars assessed the significance and guided project frameworks. This interaction aligns with what Stephenson (2008) calls the cultural values model, wherein landscape meaning emerges from material, social, and symbolic interactions [

24].

Between 1984 and 1990, the folk literature survey mobilized over two million participants, gathering 1.84 million folktales, 3.02 million folk songs, and 7.48 million proverbs—totaling more than 4 billion words [

47]. This massive effort laid a durable foundation for later ICH safeguarding. Crucially, many of these surveys occurred in situ, via face-to-face interviews, village workshops, and region-based documentation activities, highlighting the embedded, place-based nature of actor engagement [

48].

With the 2003 launch of the Chinese Ethnic and Folk Culture Protection Project, new administrative units and expert bodies emerged, injecting fresh momentum into ICH governance [

49]. These included local evaluation panels and coordination offices responsible for reviewing nominations, conducting community outreach, and ensuring regional balance. Once centered on ministerial control, the actor network gradually evolved into a multi-scalar governance system, characterized by horizontal (cross-sector) and vertical (state–local) linkages that continue to shape China’s ICH landscape today.

4.2.3. Resources

This period marked a significant expansion of resource inputs for cultural preservation, particularly through increased state support. The launch of the Compendium of Ethnic and Folk Arts project in 1979 relied heavily on government funding, with dedicated allocations for equipment procurement, publication, and project implementation. Compared to the 1950s, the 1980s saw notable improvements in field survey tools, with tape recorders and video cameras becoming more common—although handwritten documentation remained dominant. According to expert interviews, these upgrades were considered transformative by field researchers, substantially enhancing data fidelity and operational efficiency.

Crucially, this technical improvement coincided with the emergence of a spatial logic in resource distribution. Funds and equipment were often prioritized for regions with high concentrations of ethnic minorities or abundant cultural assets [

33]. This spatially selective allocation effectively designated certain landscapes as cultural preservation zones, embedding heritage efforts within broader regional development strategies.

In parallel, cultural infrastructure—including cultural stations, art centers, and regional folklore institutes—was either renovated or newly established to support these preservation efforts. As several interviewees noted, these facilities improved county-level coordination and archival capabilities. More than storage sites, they became symbolic and functional anchors in an emerging cultural infrastructure network. This reflects what Friedmann (1993) [

50] termed spatial capital—where investments in place-based institutions enable sustained material and symbolic development.

The proliferation of printed cultural materials—such as local gazetteers, heritage inventories, and oral history compilations—further supported preservation by consolidating dispersed cultural knowledge. These publications physically embedded heritage discourse into local cultural imaginaries and administrative routines [

22].

While centrally initiated, resource distribution increasingly depended on institutional partnerships involving local governments, research institutes, and publishing entities. This shift was closely tied to China’s broader adoption of market-oriented economic reforms during the post-1978 era. Unlike the earlier model of exclusive state provision, these partnerships reflected a diversification of funding and institutional roles made possible by decentralization and economic liberalization, laying the groundwork for a more pluralistic and coordinated resource-sharing system in the post-Convention era.

4.2.4. Rules

Following the Reform and Opening-Up, China gradually reinstated and introduced various policies and regulatory measures to support the preservation and development of ethnic and folk culture. In 1979, the Ministry of Culture issued the Notice on Strengthening the Leadership and Management of Opera and Quyi Performances, calling for the revival of collection and reform work under the “Double Hundred” policy [

35]. That same year, the government launched a system for selecting master artisans in arts and crafts. In 1982, it promulgated the Provisional Regulations on the Management of Folk Artists to register and oversee practitioners in the field [

51]. In 1997, the State Council issued the Traditional Arts and Crafts Protection Regulations, marking the first piece of specialized legislation related to ICH safeguarding [

29].

During this period, regulatory efforts expanded from administrative directives to include initial normative frameworks that began to define responsibilities, rights, and evaluation standards in cultural preservation. These developments signaled a shift from project-based efforts toward the gradual institutionalization of legal mechanisms. Although still fragmented and exploratory, they reflected the emergence of a hybrid governance model that combined soft regulation—such as expert consultation and pilot initiatives—with formal rulemaking procedures [

24].

At the local level, provinces such as Yunnan and Guizhou pioneered regional ICH protection regulations. These efforts helped address gaps in national legislation and shaped early models of spatially differentiated governance based on regional cultural strengths [

20]. For example, Yunnan’s regulations classified cultural spaces by ethnic distribution and historical importance, foreshadowing the zoning logic later used in ecological cultural protection zones.

In 1998, the drafting of the Law on the Protection of Ethnic and Folk Traditional Culture, although never enacted, reflected an emerging institutional awareness of the need for a more coherent legal foundation for ICH governance. As noted in archival materials and reinforced by interview insights, this proposal signaled a turning point in regulatory discourse—articulating principles such as safeguarding responsibilities, classification standards, and bearer rights that would later be formalized in the 2011 ICH Law. While the draft did not result in immediate legislative change, it contributed to the discursive consolidation of fragmented policy efforts and marked a formative moment in the evolution of China’s legal approach to cultural heritage.

These regulatory developments laid the groundwork for the codified framework that would emerge after 2003. They also marked the early formation of a landscape-based governance model, in which legal measures not only conferred institutional legitimacy but also began to define the spatial organization and authorized uses of cultural heritage sites.

4.3. Policy Arrangements Driven by the International Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2004–Present)

4.3.1. Policy Discourse

Since the start of the 21st century, China has retained its socialist ideological foundation while increasingly aligning its cultural policy system with international norms and governance frameworks. In 2003, UNESCO adopted the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, which promoted a global discourse centered on “human rights” and “cultural diversity” [

43]. It introduced a structured safeguarding model encompassing inventories, legal frameworks, scientific research, and public awareness. This international framework offered both conceptual guidance and operational models for reforming China’s ICH governance.

China ratified the Convention in 2004, initiating a systematic transformation of its ICH policy. That same year, the General Office of the State Council issued the Opinion on Strengthening the Protection of China’s Intangible Cultural Heritage—the first national policy document to explicitly use the term “intangible cultural heritage”. It outlined a new foundational principle: “protection as the priority, rescue first, reasonable use, and transmission and development”.

This marked a shift away from symbolic or ideological language toward a more programmatic and technical discourse [

52]. As policies became more codified and classification systems formalized, ICH governance in China began to reflect what landscape theorists call “strategic framing”—a discourse that encodes both cultural meaning and spatial logic [

23]. The national ICH inventories classified items by domain (e.g., oral traditions, performing arts, traditional crafts), embedding both cultural identity and territorial reference into policy. Local governments incorporated these classifications into development strategies, treating ICH as both symbolic capital and a spatial resource.

Beginning in 2006, the introduction of a four-tiered inventory system (national, provincial, municipal, and county) further institutionalized the spatial encoding of heritage. ICH was no longer abstract; it was mapped, listed, and territorially anchored. This structure laid the foundation for cultural zoning practices that later informed tourism planning, rural revitalization, and urban development [

53].

The enactment of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Law in 2011 formalized these trends. The law established classification standards, residual protection clauses, and emphasized sustainable transmission strategies [

54]. It embedded ICH into the national legal framework, consolidating the transition from narrative-driven to legally codified governance.

This transformation reflects a deeper shift: policy discourse moved from reactive preservation to proactive spatial design. ICH became a strategic asset—both discursive and material—through which China negotiated local identity, projected soft power, and participated in global cultural governance. Yet this consolidation also introduced risks. As ICH becomes more codified and instrumentalized, state-defined narratives may crowd out community-based interpretations. As ICH becomes increasingly codified and instrumentalized, the space for local contestation, vernacular expressions, and alternative forms of heritage practice may be reduced under the pressure of national branding and global visibility. This tension is evident in Leishan County, Guizhou, where a museum-centered zoning strategy reshaped the landscape to align with official portrayals of Miao culture [

55]. Despite the area’s rich ritual diversity, implementation prioritized standardized architecture and scripted performances aimed at tourism. Local narratives were subsumed under a singular cultural brand, and spatial planning—driven by national policy—favored economic visibility over context-specific meaning [

56]. The resulting landscape is legible to the state but partially alien to residents, illustrating how discursive framing and spatial governance can marginalize bottom-up expressions of heritage.

4.3.2. Actors

Since 2004, China’s efforts to protect intangible cultural heritage (ICH) have been supported by an increasingly diversified and institutionalized network of actors [

3]. At the central level, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (formerly the Ministry of Culture) leads coordination through an inter-ministerial joint meeting mechanism that includes the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Finance, and the State Ethnic Affairs Commission. In parallel, local governments have established dedicated ICH offices to oversee regional implementation. This framework exemplifies a multi-scalar governance structure that links national policy agendas with local-level execution [

48].

Beyond government institutions, the actor landscape has expanded to include academic institutions, expert committees, NGOs, and community participants [

57]. The founding of the National Expert Committee for ICH Protection in 2006, along with the establishment of provincial-level protection centers, marked the consolidation of technical expertise into the governance process [

46]. These entities are responsible not only for reviewing applications and evaluating cultural value but also for developing consistent terminology, classification systems, and assessment criteria.

At the grassroots level, inheritors, cultural workers, and local associations have become essential to the practical implementation of ICH policies. Although typically positioned as policy recipients, these actors also play an active role in shaping heritage meaning. In cases such as the Hua’er folk song database and various county-level cultural mapping projects, local participants have engaged in the spatial codification of heritage through documentation, exhibition, and site-specific inscription practices [

58].

The expansion of this actor network signals a shift toward participatory institutionalization, where governance legitimacy is derived not only from administrative authority but also from specialized knowledge and locally embedded engagement. This hybrid model allows the ICH system to function both as a technocratic apparatus and a socially grounded infrastructure. Moreover, China’s involvement in cross-border heritage nominations—such as the Mongolian Naadam Festival and Maritime Silk Road rituals—demonstrates the extension of actor networks beyond national borders. These efforts reflect China’s strategy to frame ICH as a tool for international cultural diplomacy and soft power projection [

59].

In sum, China’s ICH governance has moved from centralized administration toward a complex, multi-level, and increasingly transnational network of actors that shapes the institutional geography of cultural heritage.

4.3.3. Resources

The large-scale expansion of ICH protection during this period was underpinned by sustained financial investment and technological innovation. Between 2005 and 2015, central government funding for ICH initiatives exceeded CNY 4.2 billion (approximately USD 677 million) [

60], with additional contributions from provincial governments [

52]. These funds supported field surveys, archival projects, transmission mechanisms, research programs, and promotional campaigns. This level of investment marked a key moment in the institutionalization of spatial-cultural infrastructure.

Importantly, resources were no longer confined to financial input alone. They increasingly included digital platforms, spatial databases, and multimedia technologies. The Survey Handbook for Intangible Cultural Heritage in China (2007) introduced standardized technical procedures for documentation and conservation. Digital archives, such as the Hua’er ICH database and other regional platforms, facilitated the material translation of cultural practices into structured, searchable digital formats [

61].

Digital technologies reshaped how heritage was recorded, stored, and disseminated. Tools such as geographic information systems (GIS), AI-assisted archival platforms, and VR/AR-based visualization enabled a new form of spatial-technological integration [

62]. Heritage was no longer only preserved—it was mapped, indexed, and embedded within digital cartographies. At the same time, physical infrastructure expanded. Cultural centers, ecological protection zones, and regional training bases became spatial anchors within this emerging ICH landscape. The designation of “National Cultural Ecological Protection Zones” since 2007 institutionalized these zones as targeted enclaves of cultural activity, resource investment, and regulatory coordination.

Resource governance also began to reflect a more networked model. Universities, digital humanities institutes, local authorities, and cultural NGOs jointly participated in project funding and implementation, creating complex chains of collaboration [

33]. These interlinked systems blurred the line between cultural planning and resource distribution, fostering a more integrated interface between policy, infrastructure, and territory.

Overall, this period marked a shift from fragmented, analog preservation models toward a digitally integrated, spatially organized resource regime. Culture, data, infrastructure, and geography were increasingly bound together in the architecture of ICH governance. However, the spatial effects of this regime exposed uneven development. In Jiangnan, a region with strong financial support, dense urban infrastructure, and established academic institutions, heritage protection aligned closely with national narratives and digital modernization goals. Cultural forms such as Kunqu Opera and silk craftsmanship were showcased through high-tech museums, immersive exhibitions, and online platforms [

63]. This convergence of funding, discourse, and infrastructure created curated cultural landscapes that fulfilled state priorities and attracted global attention. Yet, such concentration also revealed structural imbalances: while Jiangnan benefited from visibility and resources, other regions with rich but less strategically positioned heritage received comparatively limited support.

4.3.4. Rules

Since 2004, China’s ICH protection has evolved from fragmented administrative measures into a structured legal and institutional system. The State Council’s 2005 Opinions on Strengthening the Protection of China’s Intangible Cultural Heritage defined official responsibilities and introduced a multi-level safeguarding framework [

64]. This was followed by key regulatory instruments, including the 2008 Provisional Measures for the Identification and Management of National ICH Representative Project Inheritors and the 2011 Intangible Cultural Heritage Law.

These developments mark a shift toward the legal codification of cultural governance. The ICH Law mandates the integration of heritage protection into broader socio-economic plans, delineates responsibilities across different levels of government, and provides legal safeguards for cultural elements and their bearers [

65]. As Gailing and Leibenath (2015) suggest, this reflects a territorial regime of landscape governance, where legal instruments encode cultural value into spatial and administrative structures [

20].

At the provincial level, regions such as Ningxia, Jiangsu, and Xinjiang issued local ordinances that complemented national legislation with region-specific norms. This rise of subnational legal frameworks illustrates a polycentric governance structure, where local regulations and national laws intersect to shape permissible uses and institutional narratives of heritage spaces [

66]. In parallel, the formal designation of cultural ecological protection zones since 2007 introduced a spatialized mode of regulation. These zones function not only as conservation areas but also as planning units, complete with rules on land use, tourism development, and community involvement. The landscape thus becomes a legally structured domain shaped by both symbolic meaning and administrative logic [

53].

The expansion of dedicated funding channels, the issuance of detailed operational rules (for inventories, site management, and project execution), and the institutionalization of state-supervised recognition systems (e.g., for representative inheritors) all underscore the depth of this legal turn. ICH governance has shifted from a policy-based concern to a law-bound, territorial system where nearly every stage of heritage management is regulated.

Together, these trends highlight the convergence of cultural heritage policy and spatial planning. Rules are no longer abstract guidelines but active instruments of territorial control. ICH protection now operates through a framework that is simultaneously legal, cultural, and spatial.

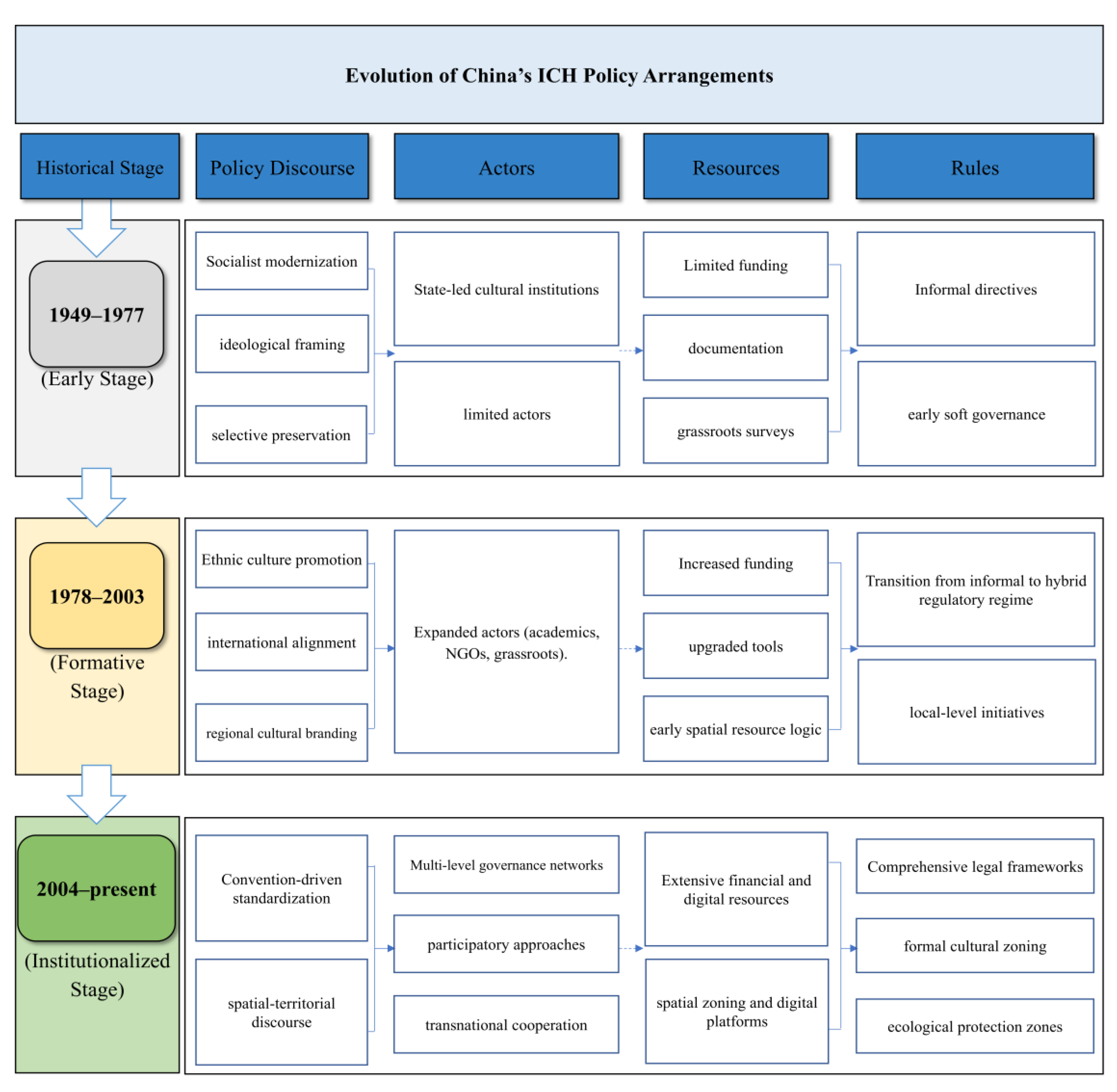

Figure 2 below summarizes the defining features of each policy arrangement phase, offering a timeline of the institutional evolution of China’s ICH governance. These evolving arrangements not only shaped institutional norms but also restructured the spatial organization of heritage practices—a transformation whose implications are further examined in the subsequent discussion.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Key Findings of the Study

Based on a three-stage historical analysis of China’s ICH policy arrangements across four institutional dimensions—discourse, actors, resources, and rules—this study identifies several key findings that trace the evolving logic of ICH governance.

First, policy discourse has shifted from ideological slogans and symbolic rhetoric to more technical and spatially structured language. In the early post-Mao period (1978–2003), narratives were shaped by the “Double Hundred” policy and national rejuvenation themes. After China ratified the UNESCO Convention in 2004, discourse became increasingly codified through legal language, classification systems, and development plans. Heritage, once treated as abstract cultural value, became framed as a tangible territorial asset

Second, the actor network evolved from centralized cultural authorities to a multi-level and increasingly transnational system. In the formative phase, heritage work was led by cultural workers, scholars, and state institutions through field-based projects. Since the Convention era, this network has expanded to include expert panels, NGOs, and grassroots practitioners, forming hybrid governance constellations that combine administrative authority with localized engagement. China’s involvement in cross-border nominations further demonstrates the international extension of its cultural governance system

Third, resource mobilization transitioned from state-funded field campaigns to a more diverse assemblage of financial, technological, and spatial inputs. During the 1980s and 1990s, resources were primarily concentrated in ethnic minority areas and depended on basic tools. Post-2004 efforts increasingly relied on digital platforms, GIS mapping, and multimedia archiving, enabling both documentation and spatial planning. The creation of Cultural Ecological Protection Zones institutionalized the idea of territorially bounded heritage spaces, linking infrastructure investment with cultural regulation.

Fourth, regulatory mechanisms moved from fragmented notices to a layered legal system. Initial regulations were local and experimental. Since the adoption of the 2011 ICH Law, a comprehensive legal framework has emerged, embedding cultural protection into broader spatial planning processes. These regulations do more than preserve heritage—they define its boundaries, regulate its use, and incorporate it into formal planning jurisdictions.

Together, these findings show that China’s ICH governance has undergone a systematic transformation marked by growing spatialization, legal formalization, and institutional consolidation. This process is not simply linear but cumulative, with each stage building on prior institutional logics while adapting to changing global norms and domestic policy goals. The resulting governance model is simultaneously spatially grounded, technically managed, and nationally strategic—yet it continues to grapple with tensions between top-down narratives and bottom-up cultural agency.

5.2. Policy Evolution as Discursive and Institutional Transformation

The evolution of China’s ICH policy is best understood as a process of discursive continuity coupled with institutional transformation. Rather than a sharp break between past and present, the trajectory reveals how earlier ideological frameworks were selectively preserved, adapted, and reorganized in response to shifting domestic and global conditions.

At the discursive level, Mao-era ideas such as “mass cultural participation” and “let a hundred flowers bloom” formed a durable foundation for post-reform cultural policy. These slogans were not discarded but reframed through the emerging language of modernization, national identity, and cultural revival [

19]. As China engaged with UNESCO’s global heritage system, policy discourse began incorporating terms like “safeguarding”, “sustainable transmission”, and “cultural diversity”. Yet these concepts were filtered through the lens of state planning, aligning global norms with national governance logic. Strategic discourse framing allowed heritage to be classified, spatialized, and integrated into land use and tourism planning frameworks.

This discursive shift paralleled a transformation in the structure of actors. In the early stage, the field was dominated by state institutions, cultural workers, and editorial committees based in mass art centers and research institutes. These actors defined what counted as heritage and how it should be represented. Over time, as governance formalized, the actor network diversified—bringing in expert panels, digital technicians, local inheritors, and even transnational collaborators. This marks a shift from centralized administration to hybrid governance, where authority is shared across bureaucracies, knowledge experts, and community participants. Notably, community involvement in spatial practices like digital mapping suggests a partial opening of heritage governance to bottom-up engagement [

67].

The convergence of these discursive and actor-based changes culminated in the institutionalization of ICH governance as a spatialized legal regime. Laws such as the 2011 ICH Law and its supporting regulations formalized not only preservation procedures but also mechanisms for territorial control. The development of multi-tiered inventories, cultural ecological zones, and digital archives transformed ICH from a symbolic category into a component of national planning. What began as cultural preservation gradually became a system of regulatory governance over cultural spaces

Thus, China’s ICH policy evolution is not merely shaped by modernization or international alignment—it is a layered institutional process. Earlier cultural logics persist within contemporary frameworks, even as new tools and discourses reshape the ways heritage is defined and governed. The result is a system where heritage functions simultaneously as memory, legal object, and spatial resource—managed through overlapping discursive, institutional, and territorial logics.

5.3. Spatial Outcomes of ICH Governance: Place-Based Contrasts

The institutionalization of ICH policy in China has not only transformed governance structures but also reconfigured the physical landscapes of heritage. Through zoning, branding, and spatial planning, ICH has shifted from lived cultural practice to a strategic asset embedded within territorial governance. Yet the spatial effects of this shift vary widely depending on how policies are implemented. The cases of Leishan and Jiangnan demonstrate contrasting outcomes—particularly regarding place identity, memory politics, and cultural sustainability—based on different governance approaches. These case discussions are drawn from policy documents and secondary sources, not field-based ethnography, which we acknowledge as a limitation to be addressed in future research.

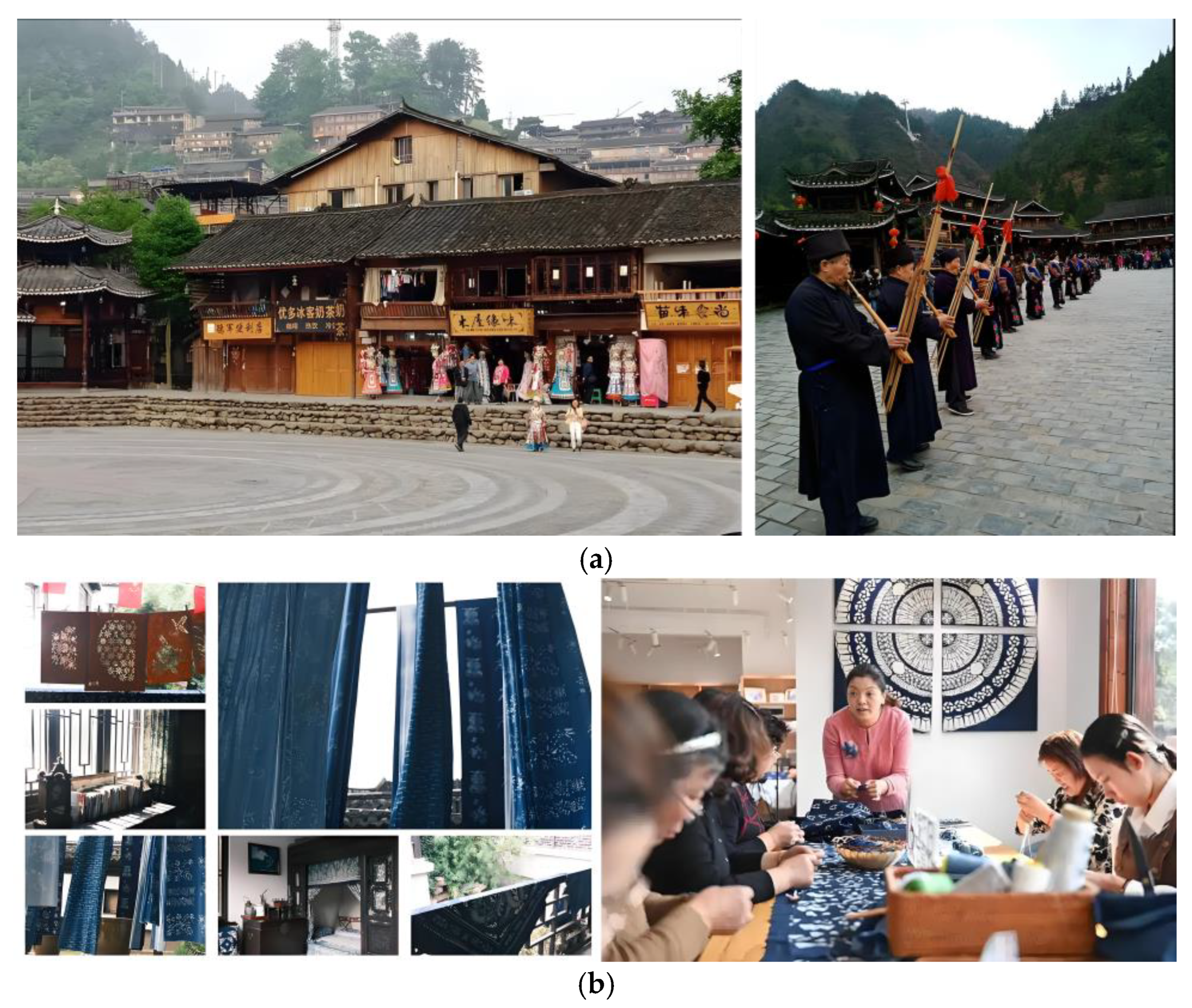

Leishan County in Guizhou offers a clear example of state-led spatialization (

Figure 3a). Designated as a key site for Miao cultural tourism, Leishan has experienced significant transformation. Traditional villages have been restructured with themed streets; sacred spaces reconfigured into performance zones; and festivals rescheduled to match tourism cycles [

68]. While these changes have elevated the visibility of local culture, they have also displaced community-rooted meanings. Planning in Leishan, driven by national tourism agendas, emphasized standardized architecture and curated performances, sidelining local agency. Sacred sites were enclosed within commercial districts, and vernacular interpretations were subsumed under broader branding efforts [

56]. This reflects Oakes’ (2016) concept of the “villagizing” of urban space, where ethnic heritage is reimagined and commodified within a tightly managed tourist landscape [

69].

In contrast, the Jiangnan Ecological Dyeing Revitalization Project in eastern China represents a community-integrated model (

Figure 3b). Here, traditional dyeing practices are reactivated within local spatial routines, not as museum artifacts but as part of everyday cultural life [

63]. Although less formalized, this initiative exemplifies what Oakes (2016) describes as bottom-up spatial production rooted in local values rather than state spectacle [

70]. The project uses modest architectural interventions, community-run workshops, and co-designed signage to embed knowledge in everyday spaces. Seasonal festivals and eco-tourism corridors promote resident participation and link artisanal skills to broader narratives of ecological and cultural identity. Rather than following external mandates, the spatial expression of heritage in Jiangnan emerges from community-led values and practices.

Together, these cases show that ICH policy is not only a regulatory framework but also a spatial force. Its impacts depend on how institutional rationalities intersect with local identity and agency.

Table 2 summarizes these contrasts, highlighting how different models of implementation affect both the cultural landscape and community dynamics. Understanding this interplay is essential for assessing landscape justice and advancing sustainable, place-based heritage governance.

5.4. Implications and Reflections

This study yields insights on two levels. Theoretically, it contributes to research on place-based cultural policy by showing that spatial logic is not merely a tool for implementation but a core component of heritage governance. The historical trajectory of China’s ICH policy demonstrates how intangible heritage is strategically reframed to align with spatial planning, turning cultural elements into instruments of territorial regulation. By applying discursive institutionalism, the study reveals that policy discourse mediates institutional change not through one-way directives, but via a recursive process of ideational adaptation and translation across policy phases. Furthermore, by comparing state-led and community-based spatial practices, the research adds to current discussions on spatial justice—arguing that fair governance involves not only the redistribution of resources but also symbolic recognition and inclusive processes.

Practically, the findings emphasize the need for spatial sensitivity in heritage governance. ICH policies reshape the environments and identities of communities, and effective governance requires mechanisms that support localized participation. Rather than imposing standardized zoning or branding, cultural authorities should create flexible frameworks that allow communities to define and inscribe heritage in ways that reflect local knowledge and evolving needs. The study also highlights the value of institutional reflexivity: both central and local actors must assess how legal, discursive, and financial instruments influence not just cultural preservation, but the everyday spatial realities of heritage bearers. Centering place in both policy design and practice is key to building a more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable heritage governance system.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite offering a historically grounded and multi-dimensional analysis of China’s ICH policy evolution, this study has several limitations. First, it relies mainly on official policy documents and secondary literature. While these sources provide valuable institutional insights, they may overlook informal, contested, or locally divergent practices that fall outside state narratives. The absence of longitudinal ethnographic data also limits the ability to examine how heritage actors engage with and adapt to spatial governance over time. Second, although the study introduces a spatial lens, the treatment of spatial outcomes remains illustrative rather than comprehensive. The cases of Leishan and Jiangnan offer useful contrasts, but a broader comparison across China’s diverse cultural regions was beyond this paper’s scope.

Future research can address these gaps in two main ways. Methodologically, combining ethnographic fieldwork, participatory observation, and spatial data analysis (e.g., GIS, remote sensing) would provide a more detailed understanding of how heritage governance reshapes everyday spatial practices and local identities. Theoretically, further work is needed to connect discursive institutionalism with critical heritage studies and political geography—particularly in exploring how symbolic power, zoning, and cultural recognition interact in place-making. Comparative studies across other countries that have adopted the UNESCO Convention could also clarify how global norms are interpreted and applied within different territorial governance frameworks. Together, these directions can enrich our understanding of ICH policy as both a cultural and spatial endeavor.

Additionally, while this study focuses on the discursive and institutional dimensions of ICH policy, other state-led domains—such as land-use planning, tourism development, and spatial regulation—may exert equal or greater influence on heritage landscapes. Future research should further investigate how ICH governance intersects with these broader policy regimes to develop a more integrated perspective on spatial governance and cultural sustainability in China.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the evolution of China’s ICH governance through the lens of discursive institutionalism, revealing how socialist-era cultural ideologies were gradually restructured into a formalized and spatialized policy regime. The findings show that ICH policy operates not only as a set of institutional tools but also as a spatial strategy—shaping how intangible culture is classified, circulated, and embedded within territorial frameworks.

The comparative cases of Leishan and Jiangnan demonstrate that different modes of implementation lead to distinct spatial outcomes, with significant implications for place identity, community engagement, and cultural sustainability. These contrasts highlight the need for ICH governance to move beyond technical preservation and engage more deeply with the spatial and social conditions in which heritage practices are situated.

Embedding ICH policy within participatory and locally responsive planning systems can strengthen both cultural resilience and spatial justice. Future research should examine how such frameworks develop across diverse regions and governance levels, and how they adapt to shifting political, economic, and cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and X.W.; methodology, J.L. and Y.D.; validation, J.L., X.W. and Y.D.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L. and X.W.; resources, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, X.W.; visualization, J.L. and Y.D.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, J.L. and X.W.; funding acquisition, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 15AH007.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Fu from the National Institute of Cultural Development in Wuhan University, as well as the relevant provincial administrative officials and staff members of intangible cultural heritage for their administrative and material support. These supports have made significant contributions to the successful completion of our research. We also sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive comments. Their thoughtful suggestions greatly helped us improve the clarity, structure, and overall quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICH | Intangible Cultural Heritage |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| IHChina | Intangible Heritage of China |

| DI | Discursive Institutionalism |

| SCC | State Council of China |

| PAA | Policy Arrangement Approach |

| CCCPC | The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China |

| LRO | Literature Research Office |

| CPCEFC | Center for the Protection of Chinese Ethnic and Folk Culture |

| PRC | The People’s Republic of China |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

References

- IHChina. National List of Representative Intangible Cultural Heritage Items. Available online: https://www.ihchina.cn/project.html (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- SC. China Is a Firm Supporter and Active Promoter of the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage: UNESCO Official Highly Praises China’s Success in Intangible Cultural Heritage Nominations. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/19/content_5571163.htm (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Gao, B.; Zhang, J.; Long, B. The social movement of safeguarding intangible cultural heritage and the end of cultural revolutions in China. West. Folk. 2017, 76, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Maags, C. Disseminating the policy narrative of ‘Heritage under threat’in China. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 26, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. From “folk education” to “intangible cultural heritage education”: The path of local practice in China (Cong “minsu jiaoyu” dao “feiyi jiaoyu”—Zhongguo feiyi jiaoyu de bentu shijian zhi lu). Folk. Stud. 2021, 47–58+159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittoun, P. Understanding policy change as a discursive problem. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 2009, 11, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices; Oxford University Press: NewYork, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Belfiore, E. Is it really about the evidence? Argument, persuasion, and the power of ideas in cultural policy. Cult. Trends 2022, 31, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, N.; Tang, L. Intangible cultural heritage protection and local development from a policy perspective (Zhengce shijiao xia de feiwuzhi wenhua yichan baohu yu difang fazhan). Folk. Stud. 2020, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.A. Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2008, 11, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.A. Reconciling ideas and institutions through discursive institutionalism. Ideas Politics Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 1, 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.A. Does discourse matter in the politics of welfare state adjustment? Comp. Political Stud. 2002, 35, 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, B.; van Tatenhove, J. Environmental policy arrangements: A new concept. In Global and European Polity? Impacts for Organisations and Policies; Goverde, H., Ed.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2000; pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- van Tatenhove, J.; Arts, B.; Leroy, P. (Eds.) Political Modernisation and the Environment: The Renewal of Environmental Policy Arrangements; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; ISBN 9401595240. [Google Scholar]

- Veenman, S.; Liefferink, D.; Arts, B. A short history of Dutch forest policy: The ‘de-institutionalisation’of a policy arrangement. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, A.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; van der Duim, R. The battle over the benefits: Analysing two sport hunting policy arrangements in Uganda. Oryx 2018, 52, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stassen, K.R.; Gislason, M.; Leroy, P. Impact of environmental discourses on public health policy arrangements: A comparative study in the UK and Flanders (Belgium). Public Health 2010, 124, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaan, P.; Alons, G.; van Voorst, S. Monitoring and evaluating the CAP: A (post-) exceptionalist policy arrangement? J. Eur. Public Policy 2023, 30, 2715–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterton, E.; Watson, S. Framing theory: Towards a critical imagination in heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailing, L.; Leibenath, M. Political landscapes between manifestations and democracy, identities and power. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, J. The agency of mapping: Speculation, critique and invention. In Mappings; Cosgrove, D., Ed.; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 1999; pp. 213–252. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E.; Watson, S. (Eds.) Heritage and Community Engagement: Collaboration or Contestation? Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J. The cultural values model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, M. Green infrastructure and planning policy: A critical assessment. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J. Networking rurality: Emergent complexity in the countryside. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 1719–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D. Intangible cultural heritage protection: A dilemma for folklore studies (Feiwuzhi wenhua yichan baohu: Minsuxue de liangnan xuanze). Henan Soc. Sci. 2008, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L. The historical evolution of China’s cultural heritage protection policy (Zhongguo wenhua yichan baohu zhengce de lishi yanjin). Heritage 2019, 111–135+320. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B. The spirit of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and China’s practice (“Baohu Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan Gongyue” de jingshen goucheng yu Zhongguo shijian). J. South-Cent. Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 37, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- CCCPC Literature Research Office. Mao Zedong Manuscripts Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China, Vol. 1 (Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong Wengao: Di 1 ce); Central Documents Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- LRO (Ed.) Selected Works on Mao Zedong’s Literary Theories [Mao Zedong Wenyi Lunji]; Central Literature Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Maags, C. Heritage Politics in China: The Power of the Past; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. A review of cultural development in New China (Xin Zhongguo wenhua fazhan licheng huigu). Stud. Contemp. Chin. Hist. 2009, 16, 111–120+251–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture Policy Office (Ed.) Compilation of Current Cultural Administrative Regulations of the People’s Republic of China (1949–1985), Vol. 1 (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Xianxing Wenhua Xingzheng Fagui Huibian, Shang Ce); Cultural Relics Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J. Introduction to Folk Literature [Mingsu Wenxue Gailun]; Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Mittelstaedt, J. Culture for the Masses: Building Grassroots Cultural Infrastructure in China. Mod. China 2024, 50, 607–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnost, A. National Past-Times: Narrative, Representation, and Power in Modern China; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.; Lu, J. A comparison of the history and policies of handicraft culture protection in China and Japan (Zhong-Ri shougongyi wenhua baohu lishi ji zhengce bijiao). Cult. Herit. 2021, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- MacFarquhar, R.; Schoenhals, M. Mao’s Last Revolution; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780674018013. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P. The Chinese Cultural Revolution: A History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780521697866. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro Ortiz, S.; Jimenez de Madariaga, C. The UNESCO convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage: A critical analysis. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2022, 28, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X. Address at the Fourth Congress of Chinese Literature and Art Workers. People’s Daily, 31 October 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. (Ed.) Collected Essays Commemorating the 30th Anniversary of Reform and Opening-Up [Jinian Gaige Kaifang Shanshi Zhounian Lunwenji]; Heilongjiang People’s Publishing House: Harbin, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- An, D.; Yang, L. Chinese folklore since the late 1970s: Achievements, dilemmas, and challenges (1970 niandai mo yilai de Zhongguo minsuxue: Chengjiu, kunjing yu tiaozhan). Folk. Stud. 2012, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Academic History of Chinese Folk Literature in the 20th Century; Henan Literature Publishing House: Henan, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L. The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D. The Chinese practice and experience in protecting intangible cultural heritage (Feiwuzhi wenhua yichan baohu de Zhongguo shijian yu jingyan). Folk. Cult. Forum 2017, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Where We Stand: A Decade of World City Research. In World Cities in a World-System; Knox, P.L., Taylor, P.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, J.; Bo, X. Rethinking the protection policies for intangible cultural heritage inheritors (“Feiyi” chuanchengren baohu zhengce de zai sikao). Southeast Cult. 2018, 6–11+127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture of the PRC. Report on the Implementation of the Convention and on the Status of Elementsinscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity(Periodic Report NO. 00611). Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/state/china-CN?info=periodic-reporting (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/638/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Li, S. Legal Guide to Intangible Cultural Heritage; Culture and Arts Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, T. Heritage as Improvement. Mod. China 2013, 39, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]