1. Introduction

Biocultural adaptation is an ongoing, multigenerational process by which human populations adjust to new environments through intertwined biological and cultural changes [

1], shaped both by ecological shifts and by evolving cultural practices [

2]. Through this study, we gain insight into species interactions and ecosystem dynamics, informing policy for environmental stewardship and deepening our grasp of biocultural diversity and social cohesion.

The conceptual framework was informed by the work of Judith Carney [

3,

4], who documented how African agroecological knowledge persisted despite the violence of the transatlantic slave trade, shaping agri-food systems in the Americas. Similarly, Nazarea [

5] and Ingold [

6] have emphasised the importance of memory, emotion, and perception in navigating unfamiliar landscapes. These perspectives position biocultural adaptation as a valuable lens for examining the intersection of ecological practices and cultural continuity in migratory contexts. In a comparative frame, McCann’s [

7] research on maize in Africa and Jordan-Bychkov’s [

8] landscape ethnography of the Upland South illustrate how migrant communities negotiate new environments through selective incorporation, reproduction, or resistance to local ecological elements.

More specifically, the study of biocultural adaptation strategies plays a pivotal role in the promotion of biodiversity and the development of positive interaction between societies and their environment. Biocultural adaptation can have a positive outcome for the community [

9,

10], but it can also result in the continuation of habitual biocultural practices in the homeland or reinforce homeland practices to the point that migrants scarcely engage with the local flora and fauna [

11]. The rapid loss of biocultural diversity requires greater scholarly attention. Therefore, within environmental studies, the analysis of local ecological knowledge and how it has changed as it has been transferred from one social, biological, and cultural context to another appears crucial. Furthermore, the current phenomenon of human migration provides an ideal subject for investigation and is one of the most critical topics for ethnobotanical research [

12,

13].

As a result of increasing global mobility, people are forced to adapt to new environments, climates, and cultures [

9], which involves learning new behaviours, values, and norms for living in a new cultural context [

14]. Consequently, recognising, documenting, and valuing biocultural adaptation strategies can help bridge cultural and political differences and facilitate transnational cooperation and collaboration [

15,

16,

17].

A potential driver of 19th-century migration in many parts of Europe was the promise of free land in foreign countries, often advertised or perceived as a “paradise” by recruiters and state propaganda campaigns. For example, people from the Baltics migrated to Siberia, the Far East, the Crimea, and the Caucasus, and villages with their own culture were preserved until the beginning of the 21st century. In the 20th century, the study of migration became popular, but the focus was on the study of the old traditions and customs of the migrants rather than their adaptation to the new environment [

18,

19].

As in other European regions, over three million Italians permanently departed their homeland in the final quarter of the 19th century, looking for a “paradise land” where they find a place to live better than in their home country. They mainly migrated to South America, and one-sixth of those migrants were from Veneto, a region in northern Italy [

20]. The migrants from Veneto had to find biocultural strategies to adapt to the Brazilian environment through agricultural practices, which involved clearing land, planting crops, and raising livestock. This significantly impacted the landscape, transforming previously forested areas into farmland and creating a more varied and abundant food supply. The biocultural adaptation strategies of Veneto migrants played a significant role in shaping Brazil’s agricultural and environmental landscape and continue to do so nowadays, since the descendants of these early migrants continue to interact with the natural environment for both work and leisure [

21,

22].

Previous research on migration from Veneto to Brazil began after the end of the Second World War, particularly in the 1970s [

23], with a specific focus on the quantitative dimensions of the migratory phenomenon [

20]. During early historical research, scholars tried to grasp the event’s relevance and what migrants contributed to national histories. Later, following the furrow traced by the studies of several researchers, including Chiara Vangelista [

24] and Angelo Trento [

25], historians favoured an individual, family and gender dimension [

26,

27,

28]. Finally, in the 2000s, scholars managed to bring out the relevance of the topic even outside the fields of study explicitly concerned with the migration phenomenon, shifting their attention to new subjects, such as refugees and displaced persons, and through the elaboration of new theories on mobility [

29,

30]. Although historical research on migration has emerged as a consolidated research topic, over the last fifty years, migration scholars from Veneto to Brazil have mainly focused on two main themes: cultural identity [

31,

32,

33] and linguistic issues [

34,

35,

36].

Recent scholarship has highlighted significant gaps in how migration-related knowledge is generated, transformed, and disseminated. Concurrently, new research underscores the necessity of analysing how migration reshapes human–environment relationships [

37,

38,

39,

40]. In historical research on migration, although scholars recognise the fundamental importance of the relationship between the cultural and environmental factors of migration [

41], little attention is paid to the environmental dimensions of migration [

42,

43,

44]. In a recent study, among other scholars, de Majo and Peruchi Moretto examined Italian migration to southern Brazil with a primary interest in the issues of agriculture and deforestation, but still placing the migrants’ identity question at the centre of their analysis [

45,

46,

47].

Overall, despite the importance of ethnobiological approaches in understanding the adaptation of migrants in South America [

48,

49,

50,

51], there is still no research on the biocultural adaptation strategies implemented by the early Veneto migrants in Brazil, nor about the historical ethnobiology on the environmental perceptions of migrants elicited via their private letters. This line of research connects ethnobiology with land and rural studies. It gives us a new way to look at how migrant communities have historically made sense of new landscapes, negotiated their perceptions of belonging through embodied ecological practices, and helped to change biocultural identities in rural areas where people have moved.

Today, the local Veneto community in Brazil comprises approximately 50,000 people and mainly dates to the period between 1870 and 1924. Although several generations have passed, some descendants of these migrants still speak the local language (or rather, the linguistic variant of Portuguese called Talian or Brazilian Veneto language) and identify themselves as Italian. However, the current Italo-descendants belong to the fourth, fifth, and even sixth generation [

52]. The examination of the biocultural adaptation strategies of migrant networks thus requires an investigation of the historical aspects of migration. Collecting and analysing archival materials are essential to studying the cultural adaptation of first-generation migrants. Consequently, exploring biocultural adaptation from a transnational and interdisciplinary perspective is a significant area of research that can provide valuable insights into the complex and dynamic relationships between people, culture, and environment in often changing and particularly complex contexts.

The research aims explicitly to (1) examine the past voluntary records of Veneto migrants arriving in Brazil; (2) identify the dimensions of biocultural adaptation strategies therein; (3) explore the Veneto settlers’ perceptions of the Brazilian landscape, their agri-food production practices, and their culinary traditions.

Historical Background

The Brazilian government actively encouraged Europeans to settle in southern Brazil from 1875 onwards. Many people came from the Veneto region of northern Italy, among other places. Past research has looked at the social and economic problems these people faced, such as not getting enough help from colonial agents and having trouble buying land. Yet, little is documented about migrants’ initial perceptions and responses upon arriving in Brazil.

The first Italian communities to leave Italy for Brazil were from the northern regions: first were the Lombards, then the people from Trentino, and finally from Veneto, particularly from the provinces of Treviso, Belluno, and Vicenza, who accounted for almost the entire Veneto migratory flow overseas (

Figure 1). Moreover, rural communities from Piedmont, another region in northern Italy, headed to Argentina, reintegrating into a rural context. At the same time, migrants from southern Italy who went to the United States soon became part of the cities. Generally, the preferred destination of Veneto’s farmers was Brazil and, more specifically, the rural areas [

26].

From 1875 onwards, Brazil’s government via its Official Agency for Colonisation and a network of public and private firms regulated the emerging colony market. Their goal was to ease the migration and settlement of farming families onto tracts of virgin forest. Then, the Brazilian government made various plots of land available to the Italian colonists, promising them the redemption or acquisition of the land and the right to citizenship after two years of residence in the colonies by living there and cultivating at least one rural plot. In each colony, each family farmed the land, sowed the seeds, and built their own house. All family members worked: men and children worked in the fields, while women were employed in export cultivation and domestic work [

26].

The general outcome of the mass migration from 1875 to the beginning of the 20th century from Veneto to Brazil concentrated mainly in five regions: São Paulo (800,000 people), Santa Catarina (250,000), Minas Gerais (90,000), Espirito Santo (50,000), and Rio de Janeiro (50,000) [

53]. Brazil has historically been a privileged destination for many Italian migrants [

54], especially in the southern regions [

55,

56,

57]. Most of the colonial settlements were in the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, and Paraná, which were characterised by favourable climatic and cultivation conditions in the area. From a chronological point of view, the migratory phenomenon was reduced in the early 20th century, as the Italian state, with the 1902 so-called Prinetti decree, promulgated a measure that prohibited subsidised emigration by the Italian state starting at the end of the 19th century, primarily when it was facilitated by the support of specific emigration agencies [

58]. Then, at the beginning of the 20th century, especially in the south of Brazil, there was a shift from a subsistence economy to progressive industrialisation and, consequently. the urbanisation of the Brazilian population, which also affected migrants and their descendants from the Veneto region.

Veneto was then one of the poorest regions in Italy [

59], where migration was not a new phenomenon but a constant occurrence in the modern period. Even before the unification of Italy (1861), every year, members of each family tried to provide for their family’s needs by moving from Veneto and looking for jobs in other areas of Italy or migrating to different European countries. Until the mid-19th century, a temporary, seasonal, and individual phenomenon made the northern regions of Italy a kind of transnational society [

60]. More specifically, in the 19th century, people in Veneto had a long migratory tradition of temporary expatriation that represented the most important historical and social factors that impacted the migration of Veneto rural communities to South America [

20]. Italian emigration represented a mass phenomenon at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century [

54].

Generally, the chronological span between the Italian territorial unification that began in 1860 and the 1970s is marked by a relevant mass emigration [

26]. From 1873 to 1895, a profound financial, agricultural, and demographic crisis significantly marked the Italian socio-cultural context. 1870 was the year that marked the first great economic depression in Italy, which arose in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War and was also consistent with an international financial crisis [

61]. The significant spread of disease, the imposition of new taxes, and the European, especially the Italian, agrarian crisis were the leading causes of a precarious and volatile social situation in Italy [

62]. This crisis, especially the demographic excess and the agricultural crisis, affected and weakened small independent agrarian production [

26]. The first wave of Italian migration, directed mainly towards Brazil and Argentina and ending around 1897, was almost exclusively a rural migration, unlike the second wave of migration, which primarily involved the urban strata of society [

63].

From 1870 onwards, the Brazilian government abolished slavery in Rio de Janeiro and throughout Brazil in 1888. At the same time, there was the so-called coffee economic boom [

64]. The need to find new workers to replace the previously enslaved populations and foster the coffee industry gave the impetus to encourage the migration processes. Moreover, Brazil had recently emerged victorious from the war against Paraguay (1865–1870), and it was necessary to ensure that the newly conquered territories were not taken away [

26]. These processes would also have contributed to increasing the Brazilian population, improving the economic situation and counteracting the territorial spread of Brazil’s indigenous communities [

65,

66]. Specifically, the Brazilian government explicitly demanded people from the agricultural sites and a specialised rural labour force, the so-called “contadini millemestieri” (“peasants of a thousand trades”), who were rural workers capable of performing many jobs [

57,

59]. From 1870 onwards, the government of the then-Brazilian empire promoted the colonisation of the state’s southern lands through a polyculture for subsistence, while in the state of São Paulo, the impetus was given for commercial development based on coffee plantations.

The Brazilian authorities thus stimulated the migratory phenomenon through the “fazendeiros”, landowners who gave work to Italian migrants, while the Brazilian government gave plots of land to Italian migrants, which were often forests in mountainous areas, demanding in exchange the cultivation of these lands and a land rent during the first years of the colony’s life. Moreover, Italian emigration agents who propagated overseas migration in Italy organised the journey [

67]. Similarly, at the beginning of the 20th century, German migrants founded their first colony, Nova Friburgo, not far from Rio de Janeiro, and in Rio Grande do Sul, one of the leading destinations of Veneto migrants, Polish migrants founded a new colony [

59].

In general, there was a mass departure from Veneto to Brazil, with the precise intention of moving permanently to overseas territories. Thus, it created a strongly European rural socio-economic structure based on small-scale independent and agricultural production based on polyculture, which later contributed to the urbanisation of a geographical area mainly devoted to livestock farming [

26,

53].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Descriptions of the Origin and Arrival Area of Migrants

Veneto is a region in northeastern Italy that, at the end of the 19th century, was described by the Italian geographer Giovanni Marinelli as “varied and complete” and presented almost all European climates [

68]. The presence of the Adriatic Sea to the east, the mountain chain of the Dolomites to the north, and in the centre was the Po Valley—marked by the presence of many rivers, including the Po, the longest in Italy—contributing to the coexistence of very different ecosystems. In the northern part, the Alpine chain makes summers cool and winters decidedly harsh. The hilly belt between the provinces of Verona, Vicenza, and Padua has a milder climate. In contrast, the Po Valley has a temperate climate, marked by high humidity all year round, with cold winter temperatures and long hot summers. In particular, the climatic and historical conditions of the Alpine city of Belluno made farming more difficult and often aimed at self-consumption, with a consequent widespread presence of wooded areas that, at the end of the 19th century, made up approximately one-third of the Belluno territory [

69,

70]. Even in Vicenza, a city in central Veneto where the first migratory flows from Veneto to Brazil started, a quarter of the territory was wooded. In the case of Treviso and Rovigo, other cities from which many Veneto people migrated to South America, forests covered 10% of the Treviso landscape and less than 1% of the Rovigo landscape at the end of the 19th century, respectively. Overall, the rural landscape of the study area was relatively homogenous during the 19th century, with the sole exception of Belluno. According to the Italian geographer Adriano Balbi, corn and legumes were mainly produced in Belluno, while in Vicenza, Treviso, and Rovigo, “wheat, rice, wine and hay” were abundant [

71].

Southern Brazil, where migrants from the Veneto arrived, is characterised by a subtropical (especially in the State of Paraná) and temperate climate, with the possibility of snowfall in mountainous areas. It is an area characterised by a high degree of morphological diversity, as there are mountainous and hilly areas, plateaus, and plains. The entire area is crossed by numerous rivers and streams (the most important being the Paraná and the Uruguay). At the end of the 19th century, southern Brazil was covered in dense vegetation.

From a geographical point of view, the areas of arrival of Veneto migrants did present geomorphologic, climatic, and hydrographic characteristics that were similar to those of the Veneto of the late 19th century, with a greater presence of forests and a milder climate than in the Veneto region [

26].

2.2. Migrants’ Letters

Throughout the 19th century and much of the 20th, letters remained the preferred means of communication to keep relations between those who migrated and those who remained in Italy, despite the many months taken for the letters to reach their destination [

72]. Letters are a deeply autobiographical genre that grant access to social groups for which other archival sources remain scarce or inaccessible [

29]. Beyond mere communication, letters constitute vital anthropological and historical documents: they capture everyday routines, emotional landscapes, and human–nature interactions. Through these personal narratives, migrants reveal how they interpreted unfamiliar landscapes, adapted their agricultural techniques, and maintained ties to local ecosystems. Moreover, as early as the 19th century, the collection, preservation, and study of the correspondence between migrants and their families and acquaintances in their country of origin began and continues to last until the present day, constituting one of the most important and relevant sources for the study of Italian migration to Brazil [

73,

74,

75]. On the one hand, they were texts that served to motivate or discourage emigration; on the other hand, they allowed Italian institutions to understand and analyse a complex phenomenon of enormous relevance at the time.

For instance, in 1876, the Academy of Agriculture, Commerce, and Arts of Verona developed the first study about migrants from Veneto. Then, there was the Jacini Inquiry (1877–1883) promoted by the homonym politician to investigate the living conditions of people in the rural areas and thus detect how many of them migrated too. In 1885, the Italian Society for Emigration and Colonisation was founded in Naples [

20]. The Italian Geographical Society in 1892 ordered the collection and cataloguing of as many letters as could be obtained, only to lose them and not follow up on this collection [

73]. Finally, some periodicals of the time began to collect and publish the letters that the relatives of those who migrated to Brazil received (

Figure 2).

A relevant exchange of information took place between the migrants and their families of origin, who were still in Italy. The correspondence exchanges between Brazil and the motherland were particularly significant for two reasons. Firstly, Italian migrants had benefitted from a (often rudimentary) form of education in writing and reading. In 1877, the Italian government had made public education of at least three years compulsory [

76]. Although at the end of the 19th century, most Italians remained generally illiterate, it seems that some Italians who migrated to Brazil could write and read, often in their specific way of writing, which was strongly influenced by the regional linguistic variety of Italian [

77]. At the beginning of the 20th century, more than one-third of the Veneto population was illiterate. Still, this percentage was much lower than the national average, which accounted for half of the Italian population over six years of age. Moreover, most of the migrants came from rural areas where, due to contextual factors specific to the Veneto reality, the illiteracy rate was slightly lower (in Treviso and Vicenza) or even much lower (in Belluno) than the respective main cities [

78].

Second, many migrants did not sever their ties with relatives who remained across the ocean, but tried to maintain their connections, giving and asking for information, forwarding requests for materials and tools that were scarce or cost too much in Brazil, sending money, and wishing or, more often, discouraging family members who remained in Italy from coming to Brazil. A strong isolation therefore characterised the geographical context of the Veneto migrants’ arrival: there was no trade network, since the relevant distances between the various settlements made it difficult for trade and there were few passages of complex communications between the settlements [

30]. Therefore, the leading communication exchange was not between the Venetian settlements in Brazil, but between the colonies and Italy. Letters thus constitute the leading resource for identifying themes, characteristics, and socio-environmental dimensions of late-19th-century Venetian migration [

72].

2.3. Sources and Their Analysis

Data for this study were collected via the analysis of the letters sent by Italian migrants to their relatives in Veneto during the first migration period, from 1877 to 1890. Letters consist of three primary sources: There were the letters published in the first (and only) Italian anthology dedicated explicitly to the South American context and migrants from the Veneto region, bringing together a selection of communications among the Veneto communities that emigrated to America [

73]. Then, another body of letters was recently published thanks to the discovery and transcription of the Rech family’s correspondence, which was originally from Belluno [

79]. Finally, a significant resource is contained in the Treviso-based journal “Il Contadino” (“The Farmer”). At the initiative of Treviso magazine contributor Gregorio Gregorj, the fortnightly journal, between 1888 and 1890, published letters that some of the magazine’s readers received from relatives who migrated to Brazil. “The vicissitudes of the peasant world, a silent protagonist, remain the most unknown aspect of social history”, stated Sabbatini and Franzina in 1977 [

26]. Nevertheless, farmers and rural communities were not a silent actor at all [

52,

79,

80]. In public and private archives, many documents were written to, about, and by rural migrants (

Figure 3).

We have 100 private letters written by Veneto migrants during the first wave of migration (1877–1894) as our empirical material. We acquired letters from old records and regional newspapers. Using Microsoft Excel and following the Detailed Use Report (DUR) approach [

81], we created a database where each row represents a different perception of the Brazilian landscape, agri-food production, and culinary practices (see

Tables S1 and S2). In each DUR we logged the following:

Date (year + specific day);

Original and current toponyms (including Brazilian state);

Author’s name and place of origin;

Any Italian–Brazilian agricultural comparisons or substitutions;

Disease references;

Tools mentioned;

Portuguese terms used;

Binomial botanical classification of reported species.

The data were processed through Critical Discourse Analysis and Sentiment Analysis, with each entry documenting the general and specific thematic focus alongside their associated general and specific emotional expressions. We applied sentiment analysis to classify migrants’ expressed perceptions as positive, neutral, or negative [

82]. These two methods were used to examine the people’s responses to the relocation in Brazil and emotions related to the Brazilian environment, agri-food production, and culinary practices. To bolster the precision of the sentiment analysis, we divided emotions into three categories: neutral (score = 0), positive (+1), and negative (−1).

A neutral perception (0 score) is when the description of a migrant is devoid of appreciation or negative considerations, as with Antonio Toffolo, a farmer from Casale sul Sile (Treviso), who said in May 1889 that “quando si va a messa alla sera vanti si fa una pinsa” (“the evening before going to mass we make pinsa”; the pinsa is a savoury leavened dough similar to pizza). In this statement, as in the others with the same score, the author did not express any emotion, merely sticking to the fact described.

Then, we assigned a very positive perception (+1 score) when a migrant, such as Sante Paparoto from Casier, Treviso, stated in January 1889 that in Guabiruba (in the state of Santa Catarina) “noi si ritroviamo alquanto bene per la posizione perche vi è laria sana, laqua buona” (“we are very well here because of the location, healthy air and good water”). This description’s prevailing emotion is positive, showing a full appreciation of the Brazilian place the family moved to. Sometimes, the perception was only partly positive, containing positive aspects, and others were less so. For instance, the priest Don Domenico Munari (originally from Fastro, Belluno) described in October 1877 that in Porto Alegre (Rio Grande Do Sul), “le terre sono fertili sì, ma comperte da selve e foreste vergini del tutto” (“the lands are fertile but covered by forests and virgin forests completely”). Thus, the land added a +1 score and the virgin forest deducted it by −1.

We awarded the lowest score (−1) when the emotional perception of migrants from Veneto was negative, leaving no room for possible neutral or positive sentiments. Giuseppe and Luigia Beraldo, a couple of peasants from the Treviso countryside, described the spread of a smallpox epidemic in February 1889 as follows: “le circostanse che ora si ritroviamo e bruttissime qui in America” (“we find ourselves here in America in awful circumstances”). In this sad description, there was no positive or neutral emotion. Sometimes, the text showed a partly negative emotion or was balanced by at least partly positive considerations and perceptions. Antonio, Luigi, and Felice Taschetto, originally from Oderzo, in the province of Treviso, moved to Santa Maria (Rio Grande do Sul). In a letter sent in 1887 to their relatives who had remained in Italy, they stated that “noialtri semo qua, ma no semo contenti” (“we are here, but we are not happy”).

3. Results and Discussion

The word cloud (

Figure 4) highlights that the recorded letters were focused heavily on themes related to agriculture, food, and the migrants’ experiences in a new environment. Key terms, such as “coffee,” “beans,” and “Italy,” suggest a narrative centred around survival, adaptation, and the contrast between the old and new worlds.

Within the studied sources, we identified seven main categories, each further subdivided into more specific topics.

Figure 5 illustrates the frequency of major topics identified in the corpus, with “environment” and “crops” being the most frequently discussed subjects. We identified seven thematic categories in our corpus: Animal Husbandry, Crops, Dietary pattern, Health, Economy, Environment, and Social life.

The animal husbandry elements, mentioned in 11% of the analysed letters and 14% of DUR, seem to be perceived as an essential topic of letter exchange (

Figure 5). The most important domestic animals are cows and horses (

Figure 6), followed by hens and pigs. The attitude towards animals was almost always positive, as they provided prosperity and food security for the families. From Campo dei bulgari (Caxias do Sul, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul), farmer Giacomo Rech from Seren del Grappa (Belluno) claimed in June 1880 to own “120 galine 2 cavali e 12 porche e tutti mangia sorgo fino che sono stufi” (“one hundred and twenty hens, two horses and twelve pigs and for everyone we feed sorghum in abundance”). Iust as the farmer from Belluno did, the migrants often detailed to their relatives remaining in Italy which animals they owned.

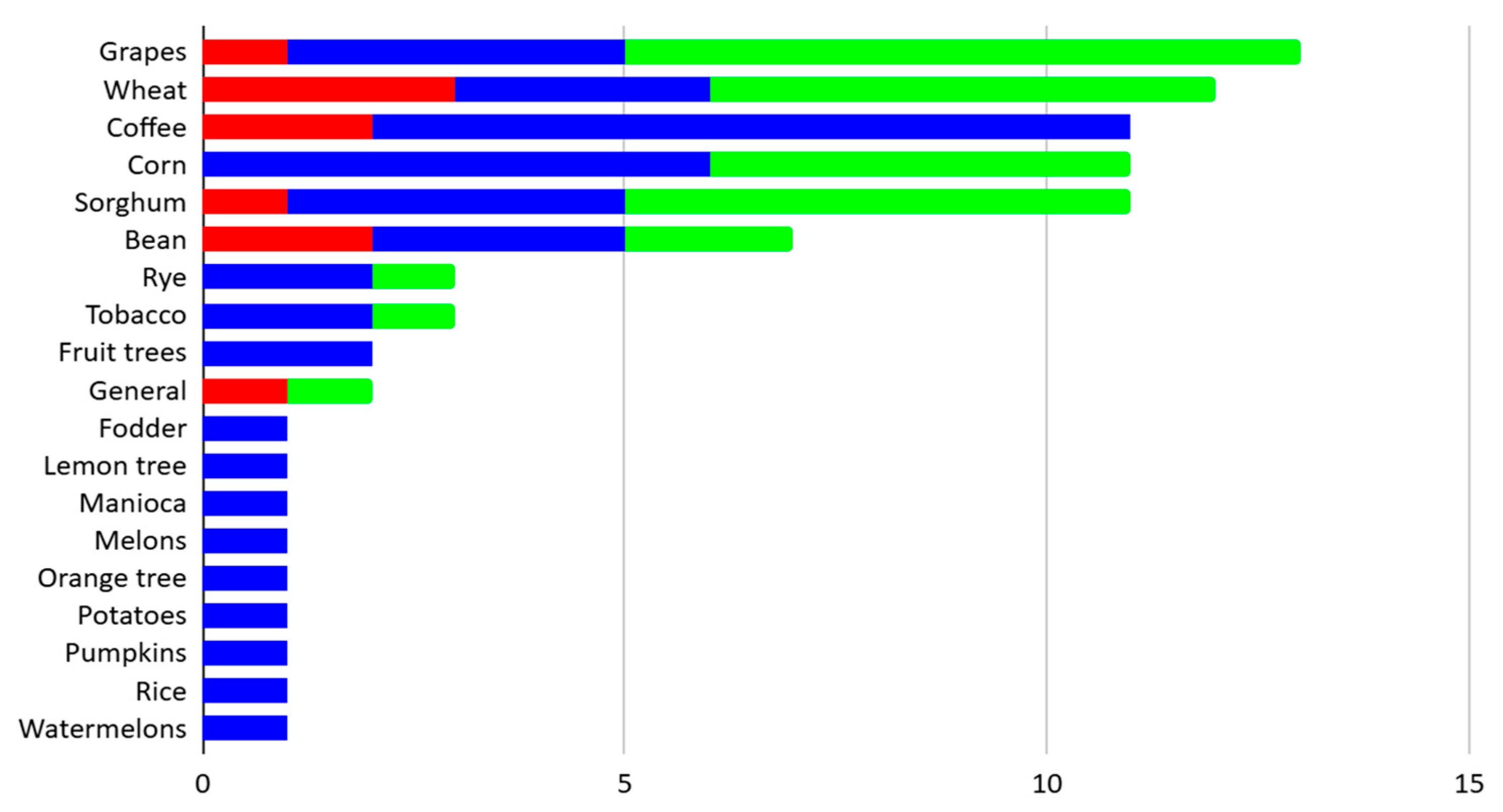

Although 23% of letters and 28% of DUR (

Figure 5) simply list crops without commentary (neutral), a significant subset of the mentioning of crops conveys strong positive or negative sentiments (

Figure 7). We interpreted the category ‘Crops’ in its strictest meaning, which is cultivating the soil, and therefore included all references to the plants that migrants from Veneto cultivated in Brazil. For instance, in February 1889, Giovanni Polese, a farmer originally from San Polo di Piave, a town in the province of Treviso, wrote from São Carlos do Pinhal (now São Carlos, in the state of São Paulo) that “in quest’ano abiamo un bel recolto di biava e fagioli per 3 anni” (“this year we have had a nice harvest of cereals and beans for three years”).

Furthermore, the category of health encompasses all mentions of infirmities in the letters of the Veneto migrants, whether they be general (epidemics) or more specific (fevers) (

Figure 8). An anonymous migrant from Treviso who moved to Ribeirão Preto (in the state of São Paulo) wrote in August 1883 that “alla facienda si prendono dei ‘bissi’ ai piedi, e posso dire che non v’è italiano che io conosca che alla Facienda non abbia avuto male alle gambe o agli occhi” (“at the fazenda there are worms attacking the feet and I can say that there is no Italian I know who has not had leg and eye pain as a result”). Diseases, poisonous animals, and epidemics, among other topics, were some of the issues related to biocultural adaptation that Veneto migrants discussed in the letters they sent to their relatives.

Social Life, the least frequent category (9% of letters, 5% of DUR;

Figure 9), vividly portrays migrants’ loneliness and isolation: “siamo in mezzo ai boschi senza ciesa senza divertimenti” (“we are in the middle of the forests without church without entertainment). Dominating are hunger and misery: “credette che qui è una miseria di quelle più grande, una fame immenza, molto pochi lavori meno ditalia, i viveri con quello che si spende per vivere una settimana qui in America in Italia si vive un mese sensa esagierare. (...) una grande mortorità di bambini e gente, insoma un disastro grandissimo, noi non godiamo salute, qui per il dottore ci vuole dieci Fiorini per visita e poi il medicamento che ordina costa uno sproposito di Fiorini, insoma qui si muore sensa prette sensa dottore come le bestie.” (“Believe me, that here there is a misery of the greatest kind, an immense hunger, very few jobs, less than in Italy, the food with what one spends to live for a week here in America, in Italy one lives for a month without exaggeration. (...) a great mortality of children and people, in short, a great disaster, we do not enjoy health, here for the doctor it costs 10 florins per visit and then the medicine that he orders costs a disproportion of florins, in short, here we die without a priest and without a doctor, like animals”).

The category of environment contains aspects of the more general human–environmental relationship developed by the Venetian communities that moved to Brazil. Therefore, we included in that category four main dimensions: a general reference to the environment (how the Veneto migrants found themselves in the Brazilian territory), what they said about the landscape (air, water, animals, plants, mushrooms, morphology, location, soil); and how they described the climate (rain, sun, storms, temperature, fog, among others). For instance, in March 1889, Giuseppe Manzoni wrote to his relatives in Italy that he was living in S. José do Rio Pardo (now known as São José do Rio Pardo, in the state of São Paulo) and that he had found “terre molto fertili, non ocore coltivazione” (“that the land is very fertile and does not need to be cultivated”) (

Figure 10). This category is vast, appearing in 27% of letters, namely danger, landscape, and weather, with some topics staying out of those dominating themes. Almost one-third of environmental-related reflections concern the dangers awaiting in the environment. At the same time, the landscape description often features an infinite forest, and the weather is also perceived as mainly hostile.

The category of economy (

Figure 11) contains the reflections on the prices (mainly unexpectedly high prices on food). Like many other migrants, Massimiliano Amadio, a farmer who had moved from Treviso to São Paulo, wrote in March 1889: “Si credeva di trovare i generi a buon mercato in vece è tutto all’incontrario: un kg di farina triste vale (…) un litro di fagiuoli pieno di vermi (…) una bottiglia d’olio vale (…) se si vuole del formaggio per metterlo nella minestra non en danno meno di (...) un pomo vale (...) un’arancia che non ha nessun gusto e piccola (...) un limonetto altri (...) due piccole patatine (...) il pane molto caro: le minestre lo stesso ed il riso che è la minestra più a buon mercato, un chilo vale (...) il caffè men male vale al chilo ma non è buono come quello di quella cara Italia; lo zucchero val al chilo (...)” (“One thought one would find the goods cheap, but it is all the other way round: a kilo of sad flour is worth (...) a litre of beans full of worms (...) a bottle of oil is worth (...) if one wants cheese to put in the soup it is worth (...) an apple is worth (...) an orange that has no taste and is small (...) two small potatos (...) bread very expensive: soups the same and rice, which is the cheapest soup, a kilo is worth (...) coffee is worth a kilo but it is not as good as that of that dear Italy; sugar is worth a kilo (...)”). This category also covers the natural economy (payments in meat or grain or wine). “E questo è il contratto che abbiamo: Farina per 6 mes—3 manzi—150 chili di lardo—4 galline per famiglia in tutto 32 galline. Il lavoro è del caffè (….) in framzezzo si potè piantare granoturco e fagiuoli” (“And this is the contract we have: Flour for 6 months—3 steers—150 kilos of lard—4 hens per family in all 32 hens. The work is coffee (....) in between we could plant corn and beans)”.

We considered the plants that the migrated Venetian communities in Brazil explicitly referred to as something to eat as part of the dietary habits category (

Figure 12). Just as the migrants listed the animals they owned, so too did they often describe in their letters what they ate. Consistently, all references to general food, plants (vine and coffee, mainly), or to what the Veneto migrants drank (wine, beer, brandy, cachaça) are part of the dietary habits category. Francesco Costantin, originally from Biadene, in the province of Treviso, and migrated to São Paulo, wrote to his relatives who had remained in Italy in June 1889 that “riguardo alla bevanda, consiste in pura acqua, alto che quelle volte che si va a messa se si tiene qualche lira si beve una bottiglia di birra, e riguardo al vino qui ci basta sentirlo nominare” (“speaking of drinks, we only drink water, sometimes when we go to mass and have some savings we drink a bottle of beer, while wine costs too much”).

Furthermore, the following three patterns of biocultural adaptation emerged from exploring Veneto migrants’ perceptions of the Brazilian landscape, agri-food production, and culinary traditions.

3.1. Perception of the Brazilian Environment

The Brazilian environment constitutes one of the most relevant themes in the descriptions of the human–environmental relationship recorded in the letters sent by Veneto migrants to their relatives who remained in the motherland. At the same time, sentiment analysis showed how the perception of the Brazilian environment was predominantly negative. The only exceptions concerned the healthiness of the air and water, as they were a clear and logical concern for communities that still, at the end of the 19th century, had to deal daily with malaria, a disease already known since Roman times but, in the 19th century, had reached its most significant global expansion, particularly in Italy. The etymology of malaria is derived from the Venetian term “malaere” (“bad air”), which precisely considers air as a possible source of contagion, although the disease is primarily spread through the presence of parasites that live mainly in stagnant water [

83,

84,

85]. Water and air were, therefore, two key elements in the relationship that Veneto migrant communities established with their environment. Moreover, the communities who migrated from Veneto perceived the Brazilian soil and rainfall positively, mainly because it made cultivation, and thus survival, possible.

However, neither the healthiness of the water and air, nor the absence of malaria, could effectively contribute to a positive perception of the Brazilian environment. There were “bissi nei piedi i xe come le formiche in Italia” (“there are as many bissi sticking up as there are ants in Italy”), which caused swelling and even death, and there were also gnats, insects, and worms. Furthermore, diseases were not absent in Brazil, which constitute a smaller but still significant proportion of references in the letters.

Moreover, neither the rain nor the fertile soil could balance a fundamentally negative perception of the Brazilian climate and landscape, so much so that in a letter, Giuseppe and Luigia Beraldo from Treviso described their location as being “in mezzo un deserto” (“in the middle of a desert”), a place where there is nothing, thus hinting at a rather significant form of plant-awareness deprivation. Again, it also appears in the text written by Antonio Toffolo, a farmer from the Treviso countryside who said, “non si vede solo che cielo e boschi” (“one can see nothing but sky and forests”). Thus, the wild environment is viewed with suspicion and distrust and is only appreciated when the absence of vegetation suggests the lack of places where wild animals can find a hiding place. Finally, relief is despised because it made farming more difficult, if not impossible, and thus, the scarcity of plains also becomes a negatively perceived element, particularly concerning agricultural prospects.

3.2. Biocultural Reproduction of the Veneto Agri-Food Model

Our data pertain to first-generation migrants, whose letters often express a desire to replicate Veneto agricultural models instead of testing local Brazilian plant species or agricultural techniques. In this way, the scenario is different from the adaptive paths that Carney found in African diasporic communities, where syncretic farming techniques led to biocultural resilience [

3,

4]. On the other hand, the Veneto case shows a significant early focus on preserving culture and only accepting some types of Brazilian biodiversity.

In the 19th century, agriculture and, consequently, the diet of farmers in the Veneto area was mainly based on the production and consumption of cereals. The most important of these was wheat, which, together with rye, sorghum, and millet, was mainly made into bread—sometimes with the addition of potatoes—and, to a much lesser extent, was consumed as pasta. Potatoes had spread since the 18th century, along with maize, which farmers ate in the form of polenta. In addition to an abundance of vegetables and pulses, especially beans, depending on the area and the season, on the tables of the Veneto peasants, there were also various cheeses and soups, to which they often added pork lard and rice. The wine that the peasants drank in Veneto was a by-product of winemaking, obtained by adding water to the already used marc, as the production of wine was usually intended for sale on the market to cover expenses and debts. From the 18th century onwards, coffee and grappa (alcoholic beverages obtained from the distillation of what remains from the production of wine) gradually spread in Veneto, the consumption of which was, however, strictly dependent on the economic resources of individual families. Meat and fish were generally scarce. Pork was almost always the most common meat among peasant families. Even then, they were still in somewhat limited quantities (around 20 kg per year), and its consumption was often reserved for extraordinary contexts and events. Fish never spread outside the Venetian lagoon area during the 19th century [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91].

The animals reared by migrants from Veneto also reflect the zootechnical practices of the time spread in Italy, supported by the presence of cattle (calf, bull, cow), mainly for dairy production, poultry (chicken and hen), and pigs for meat, and, to a much lesser extent, mules and horses for transport. The absence of sheep (and goats) perfectly reflects the Veneto livestock picture at the end of the 19th century, marked by a significant decline in sheep farming [

92].

For instance, Gottardo Cavallin and Augusta Nasato, a couple of farmers from Treviso who moved to Campinas (São Paulo), wrote in June 1890 that “in quanto a le bestie il costume è come in Italia, buoi vache muli e cavali” (“as for the beasts, the custom is as in Italy, oxen, cows, mules and horses”). Those two farmers thus emphasised that the farming practices and animal breeding in Brazil did not differ from those in use in Italy.

Pasta was a minor presence, although not entirely absent, and rice was mainly used in soups. Moreover, from a gastronomic point of view, the possibility of raising animals directly—without having to sell the products to the landowner, divide the slaughtered pig among many people, or buy the meat—made it possible to positively perceive animals and consume more meat. Moreover, as the period of Venetian migration coincided with Brazil’s economic boom in coffee, this drink also became more accessible. As a matter of fact, the Treviso farmer Giuseppe Turchetto told his family that his brother had told him “che in America si mangia sempre fagiuoli (…) in vece noi mangiamo ogni giorno carne fresca tanto di porco che di manso, pasta e riso, cafè ogni giorno che ne ho più bevuto in due mesi in America che in venti anni in Itaglia” (“that in America we always eat beans (…). Instead, we eat fresh pork and beef every day, pasta and rice, and coffee every day, which I have drunk more in two months in America than in twenty years in Italy.’) Giovanni Polese, from the Treviso countryside, also wrote that his family had not only hens but even “polani da mangiare” (“chickens to eat”).

Moreover, the increase in meat confirms what historical research has already pointed out, such as when, in the absence of game in Brazil, Veneto farmers resorted to the meat of macaques [

26]. The perception of food in Brazil was mainly positive: the variety of food was increasing, especially with regard to the consumption of meat and coffee. Meat, coffee, and the increased variety of food in general became, among others, the main features of 20th-century Italian cuisine. The worldwide spread of Italian recipes was based mainly on how Italians who migrated to the American colonies used to cook, thanks to the letters that migrants sent to relatives who had remained in Italy.

3.3. Biocultural Isolation from Brazilian Landscape and Cultures

Our research shows that the first-wave Veneto migrants tried to duplicate familiar agri-food systems in Brazil, and frequently avoided engagement with the local environment. This is clear from the fact that they prefer to import seeds, tools, and even food; for example, they imported specific pots for cooking polenta. The wilderness was not romanticised or changed to fit people’s needs; it was instead seen as a barrier to work and safety. Several letters clearly perceived wilderness as a source of danger or discomfort. Dense forests were often associated with wild animals, disease, and a lack of security. The expressions suggest that the wild, untamed landscape was often seen not as a resource, but as an obstacle to settlement and well-being. This perspective underscores how early Veneto migrants preferred proximity to cultivated or inhabited areas, which they equated with safety and familiarity.

The third aspect that characterises the adaptation of migrants from Veneto is biocultural isolation from the Brazilian socio-environmental context. There are no references to other local or indigenous Brazilian communities in the letters of the Veneto communities. Likewise, no plants or animal species are named with Brazilian names or references. The only exception is Brazilian brandy, although it is of Portuguese origin from the island of Madeiros, made from sugar cane, cachaça. The Belluno farmer Giacomo Rech wrote that his daughter worked for food, lodging, and “una garafa di cacasa” (“a jug of cachaça”). It was probably the same drink that the priest Don Domenico Munari described without remembering or writing the exact Portuguese name, but stating that in Brazil, there was no wine and migrants “devono (se pur il possono) sostituire una specie d’acquavite estratta dalla canna di zucchero fermentata, di un sapore sgradevolissimo” [“must (if they can) substitute a kind of aquavit extracted from fermented sugar cane, of a most unpleasant taste”]. Migrants from Veneto did not mention any other local food or drink in their letters.

In summary, Veneto migrants’ rural isolation was pivotal in perpetuating the Veneto farming system. Both small-scale independent agricultural production and the subsistence family economy created the ideal context for Veneto traditions to be reproduced in Brazil. Moreover, the negative perception of the Brazilian environment reinforced the socio-cultural isolation and reproduction of rural and food practices in Veneto. The three dimensions that characterise biocultural adaptation are closely interconnected and interdependent. Thus, the adaptation of Veneto migrants was characterised by a biocultural reproduction that was as faithful as possible to the original model of the same rural society and value system had crystallised since the arrival of the first migrants [

26]. Even after many decades, there are still nowadays some gastronomic elements belonging to Veneto culture in Brazilian culinary manifestations, such as the fried polenta included in the churrasco ritual, the co-presence of wine with cachaça, or the “festa da polenta” or “polentaço”, a celebration held in many towns where Veneto migrants arrived [

93,

94] (

Figure 13).

Much of the historical literature has by now clarified some of the main dynamics of the migratory phenomenon of food acculturation. In particular, the migrant’s reaction to the sense of disorientation and nostalgia resulting from expatriation is often addressed through recourse to gastronomic conservatism. At the same time, however, emigration also entailed rather radical changes in food, starting with the journey itself, where the variety of food was far greater than the poor and repetitive eating habits to which the Veneto peasants were accustomed. It was precisely thanks to emigration that the development of Italian cuisine, elaborated on the model of the Italian elite, was possible [

95,

96]. Overall, emigration led the Veneto peasant communities to eat differently, but this was also, above all, made possible by the isolation from the Brazilian socio-environmental context, the relative negative perception, and the reproduction of the Veneto rural model as close as possible to the ideal of the time. This observation aligns with earlier findings that in 19th-century Baltic migration, “old customs” from the home country are continued in the new host country, while the new environment is perceived as hostile [

97].