Excavating Identity: The Significance of Soil Exhibitions for Understanding Place

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Erosion of Place Identity in the Modern Era

2. Theoretical Framework: Integrating Soil Relationality and Exhibition as Knowledge Production

2.1. Soil as Living Community and Relational Entity

2.2. Exhibitions as Laboratories for Knowledge Production

2.3. Synthesis: An Integrated Approach to Soil Exhibitions

- Engage multiple senses to make soil’s invisible qualities and relationships perceptible (applying Puig de la Bellacasa’s “haptic epistemologies”)

- Create spaces for dialogue and community engagement around soil’s role in place identity (drawing on Obrist’s “temporary communities”)

- Represent soil as a living, active participant in place-making rather than as a passive substrate (following Puig de la Bellacasa’s relational ontology)

- Position exhibitions as sites for generating new understandings of soil–human relationships rather than merely displaying established knowledge (applying Obrist’s knowledge production model)

- Foster ethics of care toward soil that recognises interdependence and reciprocity (integrating Puig de la Bellacasa’s care ethics)

2.4. Soil’s Multidimensional Role in Place Identity

2.5. Previous Approaches to Soil Exhibitions

2.6. Exhibitions as Platforms for Knowledge Exchange and Community Engagement

3. Materials and Methods

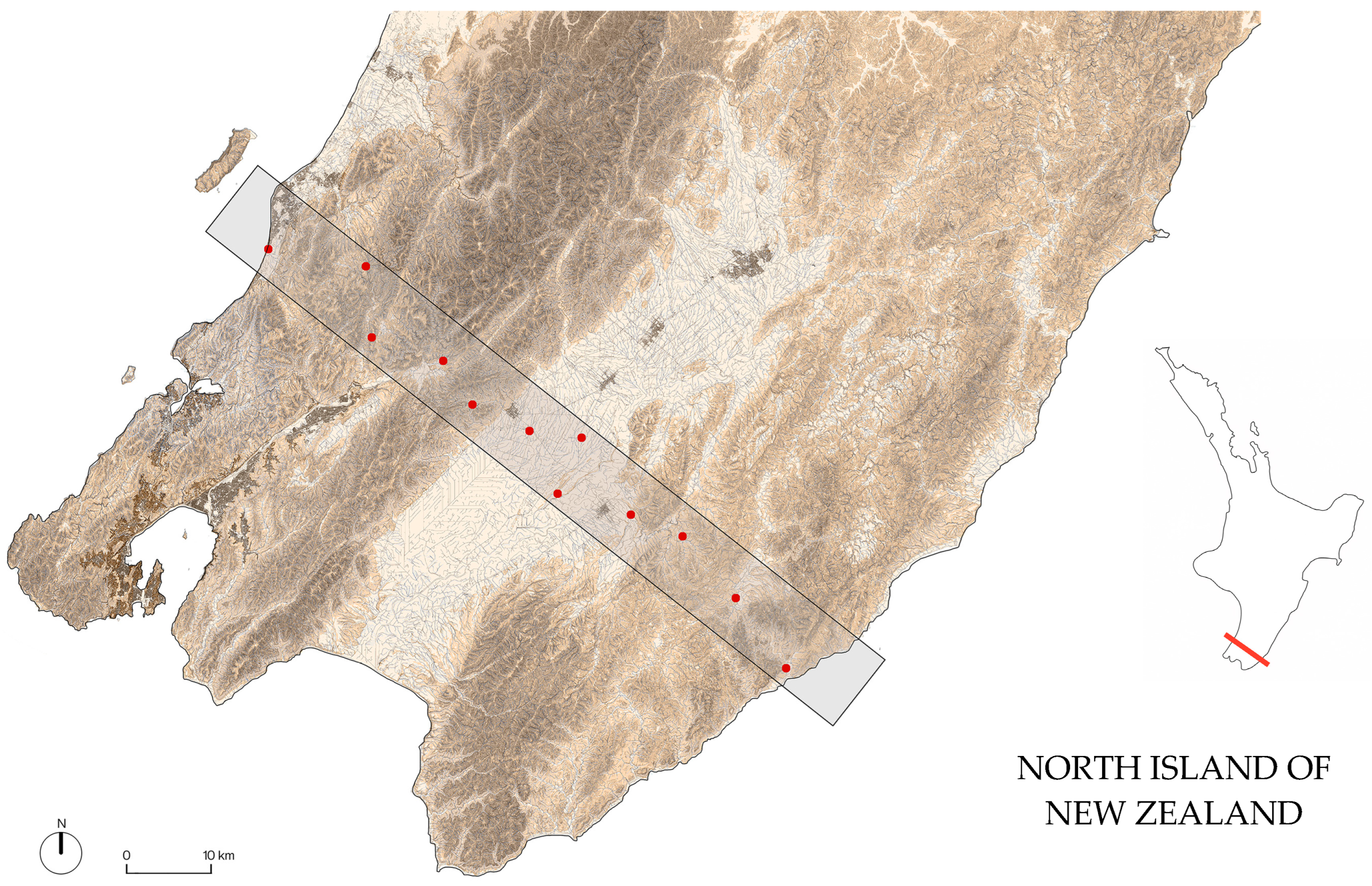

3.1. Soil Sampling and Analysis

- Colour: Assessed using Munsell Colour system under natural light. Challenges in matching subtle hues and the need for dry, powdered samples highlighted the limitations of standardised charts for capturing chromatic richness. A systematic documentation protocol involving photographing samples at three moisture levels was developed to capture colour shifts [59].

3.2. Exhibition Design and Curation

4. Case Study Exhibitions: Material Explorations of Soil and Place

4.1. Window Display: Soils Notation (December 2022–February 2023)

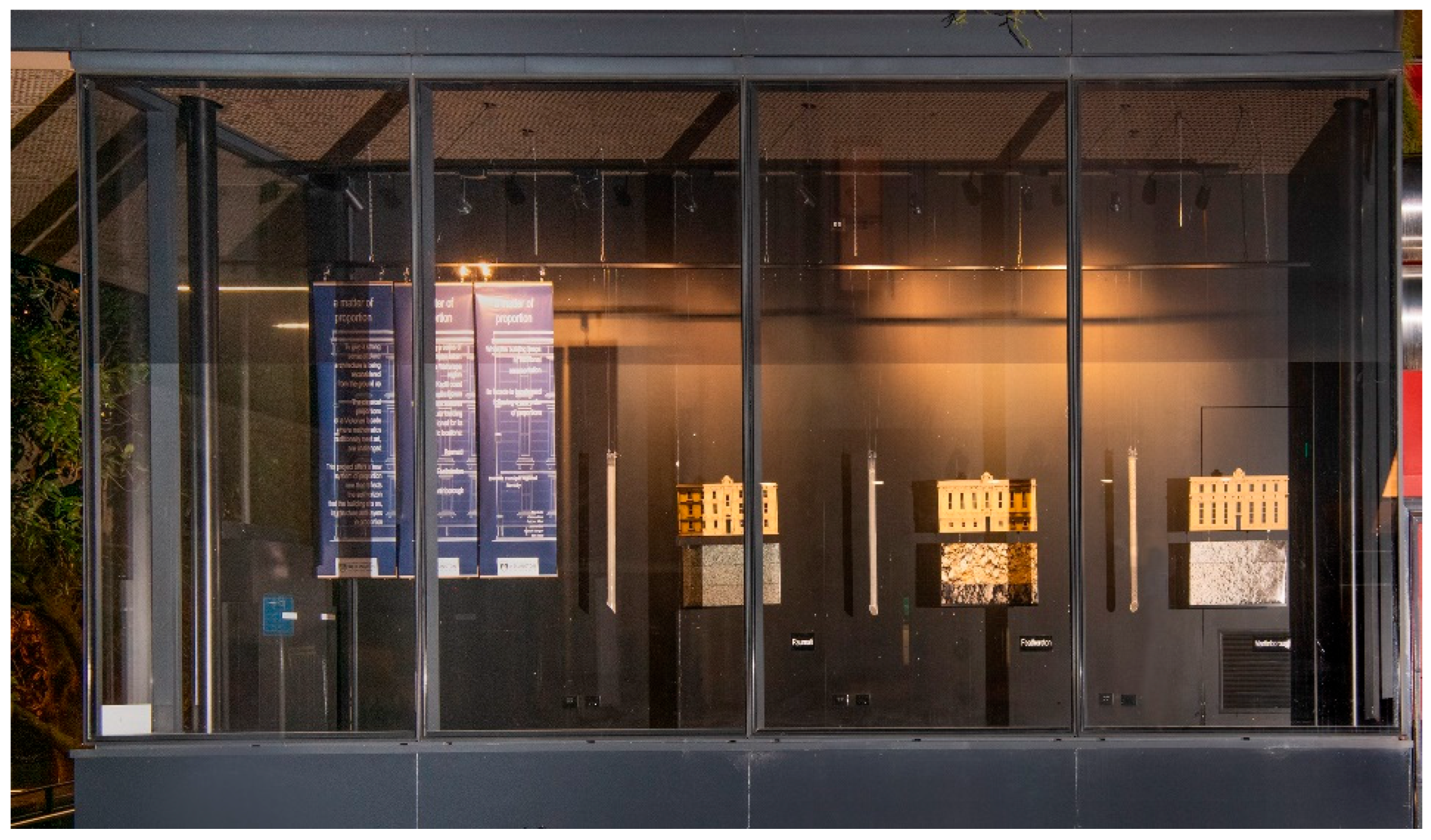

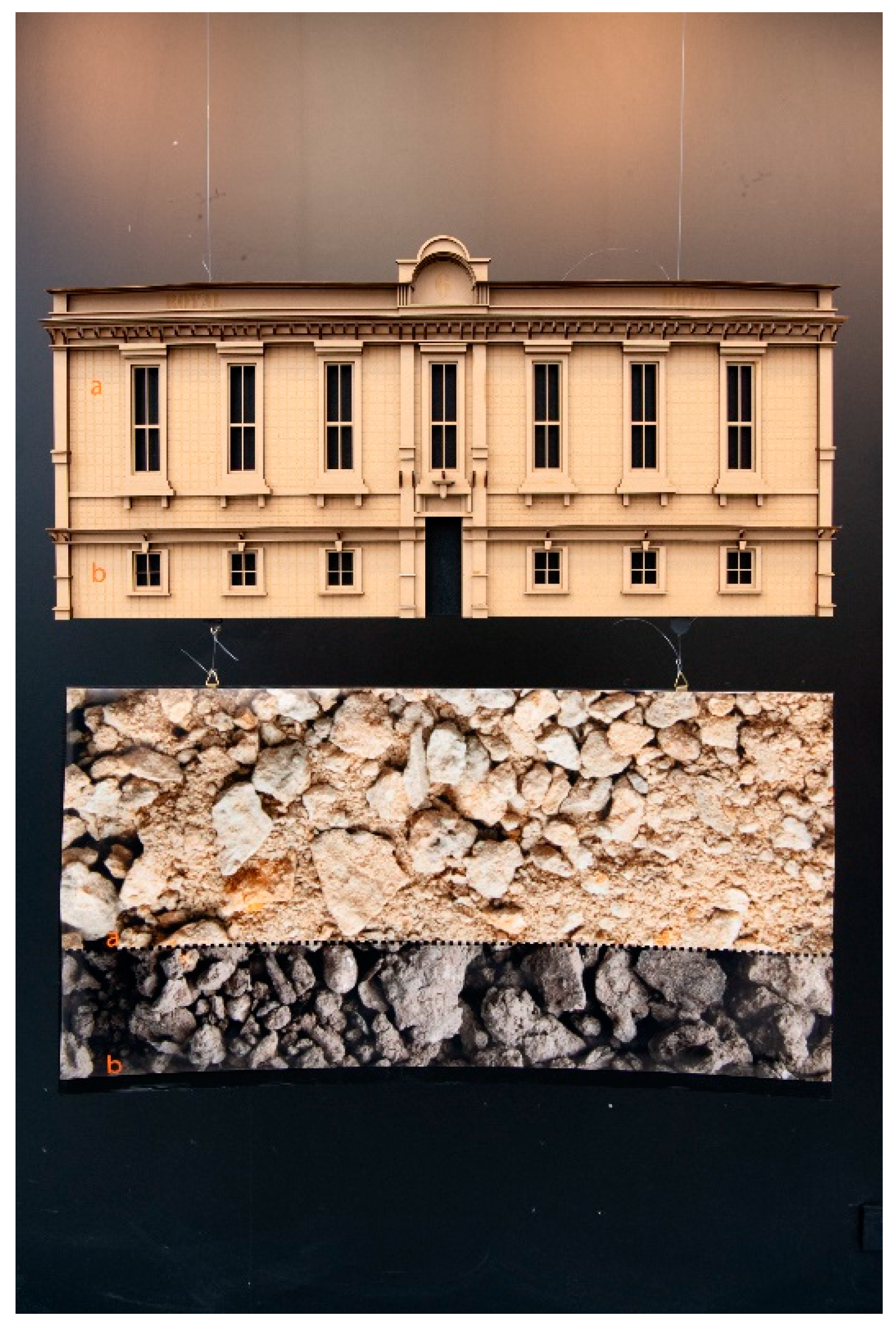

4.2. Window Display: A Matter of Proportion (December 2023–September 2024)

4.3. Lightbox Display: Horizons Revealed (December 2023–November 2024)

4.4. Gallery Exhibition: A Site to Behold (November 2022)

4.5. Exhibition Assessment

5. Discussion

5.1. Soils Sampling and Analysis

5.1.1. Colour Analysis and Visual Communication

5.1.2. Structure Analysis and Three-Dimensional Representation

5.1.3. Texture Analysis and Multisensory Engagement

5.1.4. Horizon Proportions and Architectural Translation

5.2. From Soil Analysis to Exhibition Design and Curation

- Enhanced Visual Literacy: Visitors would develop an increased ability to “read” soil profiles and recognise distinctive regional characteristics.

- Regional Identity Recognition: Participants would form new associations between soil properties and both local and potential architectural traditions.

- Scientific Engagement: Non-specialist audiences would gain insight into pedological processes through aesthetic experience.

5.3. Limitations and Exhibition Comparison

- Window Displays: “Soils Notation” and “A Matter of Proportion” offered high visibility and accessibility to a broad public, effectively communicating a simple message quickly. Their concise nature and potential for strong visual impact were advantageous. However, the limited space restricted the depth of information and opportunities for visitor interaction, and the surrounding environment and reflections from adjacent building lighting can potentially distract from the exhibition’s message.

- Lightbox Display: “Horizons Revealed” benefited from high-quality visuals and a dual focus on aesthetic and scientific aspects, also offering good public accessibility. The limitation of this form of exhibition was its two-dimensional engagement. A QR code placed on the side of the lightbox display provided subsequent information about the research and how one might engage with soil.

- Gallery Exhibition: “A Site to Behold” allowed for the most comprehensive exploration of the topic, incorporating diverse media and providing a richer, multi-sensory curated experience. The controlled gallery environment also allowed for better control over contextual factors. However, gallery exhibitions typically have more limited accessibility and can potentially overwhelm visitors with information if not carefully curated.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. (Eds.) Place Attachment; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-1-4684-8755-8. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A.; Marques, B. Out of Place: Rewriting the Signatures of a Landscape. Spaces Flows Int. J. Urban Extra Urban Stud. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Perkins, D.D.; Brown, G. Place Attachment in a Revitalizing Neighborhood: Individual and Block Levels of Analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction; Blackwell Pub: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-4051-0671-9. [Google Scholar]

- Craul, P.J. Urban Soils: Applications and Practices; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-471-18903-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemnezhad, H.; Heidari, A.A.; Hoseini, P.M. “Sense of Place” and “Place Attachment”. Int. J. Archit. Urban Dev. 2013, 3, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, S.; Farmer, G. Reinterpreting Sustainable Architecture: The Place of Technology. J. Archit. Educ. 2001, 54, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, R. Culture, Imaginary, and Rationality in Regional Economic Development. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2000, 32, 1215–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.J. The Importance of Parent Material in Soil Classification: A Review in a Historical Context. Catena 2019, 182, 104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkeland, P.W.; Birkeland, P.E.G.P. Soils and Geomorphology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-0-19-507886-2. [Google Scholar]

- Minke, G. The Properties of Earth as a Building Material. In Building with Earth; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 19–35. ISBN 978-3-7643-7477-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, Q.-B.; Morel, J.-C.; Tran, V.-H.; Hans, S.; Oggero, M. How to Use In-Situ Soils as Building Materials. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Why Landscapes of the Past Are Important for the Future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene, 1st ed.; Gibson, K., Rose, D.B., Fincher, R., Eds.; Punctum Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-9882340-6-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S. Landscape: Pattern, Perception and Process; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-203-12008-8. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, D.L.; Schifman, L.A.; Shuster, W.D. Widespread Loss of Intermediate Soil Horizons in Urban Landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6751–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, B.; Freeman, C.; Carter, L.; Pedersen Zari, M. Sense of Place and Belonging in Developing Culturally Appropriate Therapeutic Environments: A Review. Societies 2020, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, S.; Basso, K.H. Senses of Place; School of American Research Advanced Seminar Series; Boydell & Brewer, Ltd.: Rochester, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-85255-900-0. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Clayton, S. Introduction to the Special Issue: Place, Identity and Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer-de-Forges, A.C.; Lowe, D.J.; Minasny, B.; Adamo, P.; Amato, M.; Ceddia, M.B.; Dos Anjos, L.H.C.; Chang, S.X.; Chen, S.; Chen, Z.-S.; et al. A Review of the World’s Soil Museums and Exhibitions. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 166, pp. 277–304. ISBN 978-0-12-824587-3. [Google Scholar]

- Arefi, M. Non-place and Placelessness as Narratives of Loss: Rethinking the Notion of Place. J. Urban Des. 1999, 4, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Research in Planning and Design; Pion: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-85086-176-1. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, J.A. Space and Place. In The SAGE Handbook of Geographical Knowledge; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 316–330. ISBN 978-1-4129-1081-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, D. Museum Exhibition: Theory and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-203-03936-6. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, J.; Marques, B.; Martinez Almoyna, C.; Campays, P. Searching for Identity: Finding the Expression of Place under Ground. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latva-Somppi, R. Soil Laboratory: Crafting Experiments in an Exhibition Setting. In Expanding Environmental Awareness in Education Through the Arts; Fredriksen, B.C., Groth, C., Eds.; Landscapes: The Arts, Aesthetics, and Education; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; Volume 33, pp. 213–229. ISBN 978-981-19485-4-1. [Google Scholar]

- Xylander, W.E.R.; Zumkowski-Xylander, H. Increasing Awareness for Soil Biodiversity and Protection the International Touring Exhibition “The Thin Skin of the Earth”. Soil Org. 2018, 90, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worster, D. The Wealth of Nature: Environmental History and the Ecological Imagination; Oxford scholarship online; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-19-509264-6. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler, B.L.; Hamel, P.; McPhearson, T.; Hamann, M.H.; Donahue, M.L.; Meza Prado, K.A.; Arkema, K.K.; Bratman, G.N.; Brauman, K.A.; Finlay, J.C.; et al. Social-Ecological and Technological Factors Moderate the Value of Urban Nature. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.B. Space, Place, and Gender, 6th ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-8166-2617-5. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. Inventing Future Cities; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-0-262-54865-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K.M.; Chen, J.; Kang, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Duarte, F.; Ratti, C. Place Identity: A Generative AI’s Perspective. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig De La Bellacasa, M. Re-Animating Soils: Transforming Human–Soil Affections through Science, Culture and Community. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 67, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrist, H.U. Formulas for Now; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-500-23850-9. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, H.U.; Lamm, A.E.; Sehgal, T.; Friedman, Y. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Curating: But Were Afraid to Ask; Sternberg: New York, NY, USA; Berlin, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-1-933128-25-2. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, H.U.; Bovier, L. A Brief History of Curating; Documents Series, 9. Aufl. JRP Ringier: Zürich, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-905829-55-6. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, H.U. Ways of Curating, 1st American ed.; Faber and Faber: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-86547-819-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Museums and Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-134-18169-8. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, R.R.; Brady Late, N.C.; Weil, R.R. Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0-13-349336-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-134-58566-3. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, D. Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader; Sensory Formations; Berg Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-1-85973-863-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bladholm, S. Soils, Seeds, and Sprouts: Tropical and Temperate; Sharon Bladholm: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022; ISBN 979-8985400908. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.R. Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-520-24870-0. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B.; Weibel, P. Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth; ZKM Center for Art and Media: Karlsruhe, Germany; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-262-04445-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance; Museum meanings; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-415-37935-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wessolek, G.; Toland, A. Exploring the Artistic Dimensions of Soils in the Vadose Zone. Vadose Zone J. 2024, 23, e20308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, M.C.; Marinari, S. Digging in the Dirt: Searching for Effective Tools and Languages to Promote Soil Awareness. Soil Secur. 2024, 16, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. (Ed.) Museums in a Digital Age; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-203-71608-3. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. (Ed.) A Companion to Museum Studies; Blackwell Companions in Cultural Studies, 1., Aufl.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4443-5794-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jenny, H. Factors of Soil Formation: A System of Quantitative Pedology; Dover books on earth sciences; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-486-68128-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schinner, F.; Öhlinger, R.; Kandeler, E.; Margesin, R. Methods in Soil Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-642-60966-4. [Google Scholar]

- Candy, L. Practice Based Research: A Guide; Creativity & Cognition Studios, University of Technology: Sydney, Australia, 2006; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, J. The Reed Field Guide to New Zealand Geology: An Introduction to Rocks, Minerals and Fossils; Reed: Wellington, New Zealand, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7900-0856-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, A.E.; Balks, M.R.; Lowe, D.J. The Soils of Aotearoa New Zealand; World Soils Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-64763-6. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, T.H.; Lilburne, L. Criteria for Defining the Soil Family and Soil Sibling: The Fourth and Fifth Categories of the New Zealand Soil Classification. Landcare Res. Sci. Ser. 2011, 3, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeneberger, P.J.; Wysocki, D.A.; Benham, E.C. Field Book for Describing and Sampling Soils; National Soil Survey Center Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2012; p. 298. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey Staff. Field Book for Describing and Sampling Soils; U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- GLOBE. Soil Characterization Protocol: Field Guide; GLOBE: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Color, M. Munsell Color (Blog). Available online: https://munsell.com (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Phogat, V.; Tomar, V.; Dahiya, R. Soil Physical Properties. Soil Sci. Introd. 2015, 6, 135–171. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, K.T. Soils: Principles, Properties and Management; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-94-007-5663-2. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.A.; Pollio, A.R.; Turk, P.J. Comparison of Munsell Soil Color Charts and the GLOBE Soil Color Book. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013, 77, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Minasny, B.; Roudier, P.; McBratney, A.B. Colour Space Models for Soil Science. Geoderma 2006, 133, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorman, J.J. Understanding Soil Microbes and Nutrient Recycling. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2010, SAG-16, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, T.J. Particle-Size Distribution of Soil and the Perception of Texture. Soil Res. 2003, 41, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exhibition/Project Name | Visibility of Soil Processes | Connection to Sensory Experience | Regional Identity Emphasis | Audience Engagement | Scientific-Artistic Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soils Notation (2022–2023) & A Matter of Proportion (2023–2024) New Zealand | Visual representation through photography and diagrams; translation of soil horizon depths into architectural proportions | Primarily visual; connects soil morphology to built environment proportions | Connects soil horizons to local architectural elements | Accessible to casual passers-by; integrates soil awareness into daily urban experience | Emphasises artistic interpretation of scientific measurements |

| Horizons Revealed (2023–2024) New Zealand | Large-format soil profile photographs with colour and black-and-white presentations | Strong visual emphasis on aesthetic qualities (“soil flowers”) | Places soil profiles directly in public space | High visibility in public spaces | Balances scientific accuracy with aesthetic presentation |

| A Site to Behold (2022) New Zealand | Physical samples, resin casts, photographs, maps, and posters | Multisensory, tactile engagement with soil samples | Connects soil types to local landscapes and cultural practices | Interactive elements encourage direct engagement | Comprehensive scientific information alongside artistic elements |

| Underground: Soils, Seeds, and Sprouts (Bladholm & Notebaert, 2017) Chicago, USA | Focus on ecological functions and agricultural importance | Emphasises universal soil properties | Limited focus on regional identity | Primarily educational | Weighted toward scientific communication |

| Critical Zones Exhibition (Latour & Weibe, 2021) Germany | Focus on political and ecological relationships | Multimedia approach emphasising interconnections | Positions soil within global political systems | Intellectually engaging | Artistic presentation of scientific/philosophical concepts |

| Soil Matters (Latva-Somppi, 2020) Finland | Combines artistic, craft, and scientific methods; includes soil analysis | Multisensory (tactile, visual, participatory) | Strong regional focus (Nordic soils, Venetian landscapes) | High engagement through workshops and live lab work | Strong balance of science and craft practices |

| Soils Project (SFS, TarraWarra Museum of Art and Van Abbemuseum, 2023) Australia and the Netherlands | Explores impacts of farming, mining, colonisation, and land management on soil and cultural heritage. Addresses cultural memory related to specific landscapes. | Primarily visual (photography, installation) and conceptual, focusing on landscape histories and impacts rather than direct soil sensation. | Explicitly connects specific locations (Wurundjeri Country, Australia; Yogyakarta, Indonesia; Eindhoven, Netherlands) exploring their distinct histories, environments, and knowledges. | Collaborative research initiative involving artists, activists, curators, academics. Included webinars, workshops, exhibitions, festival aiming for dialogue and exchange. | Involves artists, activists, and research institutions, exploring agrarian struggles, ecological justice, cultural heritage, land management through artistic and research practices. |

| SOIL: The World at Our Feet (Somerset House, London, January–April 2025) UK | Aims to show ‘life below ground,’ microbial life, mycelium networks. Includes scientific artefacts and micro-photography to make the invisible visible. | Explicitly combines “sensory artworks,” sound installations (microbial life recordings), micro-photography, and digital projections alongside objects. | Features global artists and thinkers addressing universal themes of planetary health. While individual works may have regional roots, the overall focus is not on one region. | Includes events, activities, educational section, opportunities for visitor response (post-it notes), shop, café offers. Aimed to inspire, educate, and promote action. | Explicitly brings together global artists, writers, musicians, and scientists. Combines artworks, historical objects, scientific artefacts, and documentary evidence. Co-curated by artists and curators. |

| Save Land: United for Land (Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, December 2024–June 2025) Germany | Focuses on soil formation, land degradation rates, links to climate change, resource consumption (city supply chains). Presents scientific findings. | Described as “immersive,” using videos, spatial installations, archaeological finds, and artworks to make the topic “emotional and tangible.” | Addresses global issues (G20 Land Initiative) but uses specific examples (German cities, Peruvian artist/maize). Themes allow for regional exploration within a global context. | Aims to raise awareness, encourage action, and foster a “shift in thinking” by making complex scientific information accessible and emotional through art. | Explicitly presents scientific findings together with diverse artistic media (video, installation, art, archaeology). Collaboration between G20 GLI and an art museum. |

| Un/Making Soil Communities (Åsa Ståhl and Kristina Lindström, 2018) Finland | Participatory phytoremediation workshops | Interactive planting and storytelling | Strong regional ties (Sweden, Finland) | Co-creative with locals | Blends design research, ecology, and art |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McIntosh, J.; Marques, B.; Campays, P.; Martinez-Almoyna, C. Excavating Identity: The Significance of Soil Exhibitions for Understanding Place. Land 2025, 14, 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071346

McIntosh J, Marques B, Campays P, Martinez-Almoyna C. Excavating Identity: The Significance of Soil Exhibitions for Understanding Place. Land. 2025; 14(7):1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071346

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcIntosh, Jacqueline, Bruno Marques, Philippe Campays, and Carles Martinez-Almoyna. 2025. "Excavating Identity: The Significance of Soil Exhibitions for Understanding Place" Land 14, no. 7: 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071346

APA StyleMcIntosh, J., Marques, B., Campays, P., & Martinez-Almoyna, C. (2025). Excavating Identity: The Significance of Soil Exhibitions for Understanding Place. Land, 14(7), 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071346