Women’s Preferences and Perspectives on the Use of Parks and Urban Forests: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

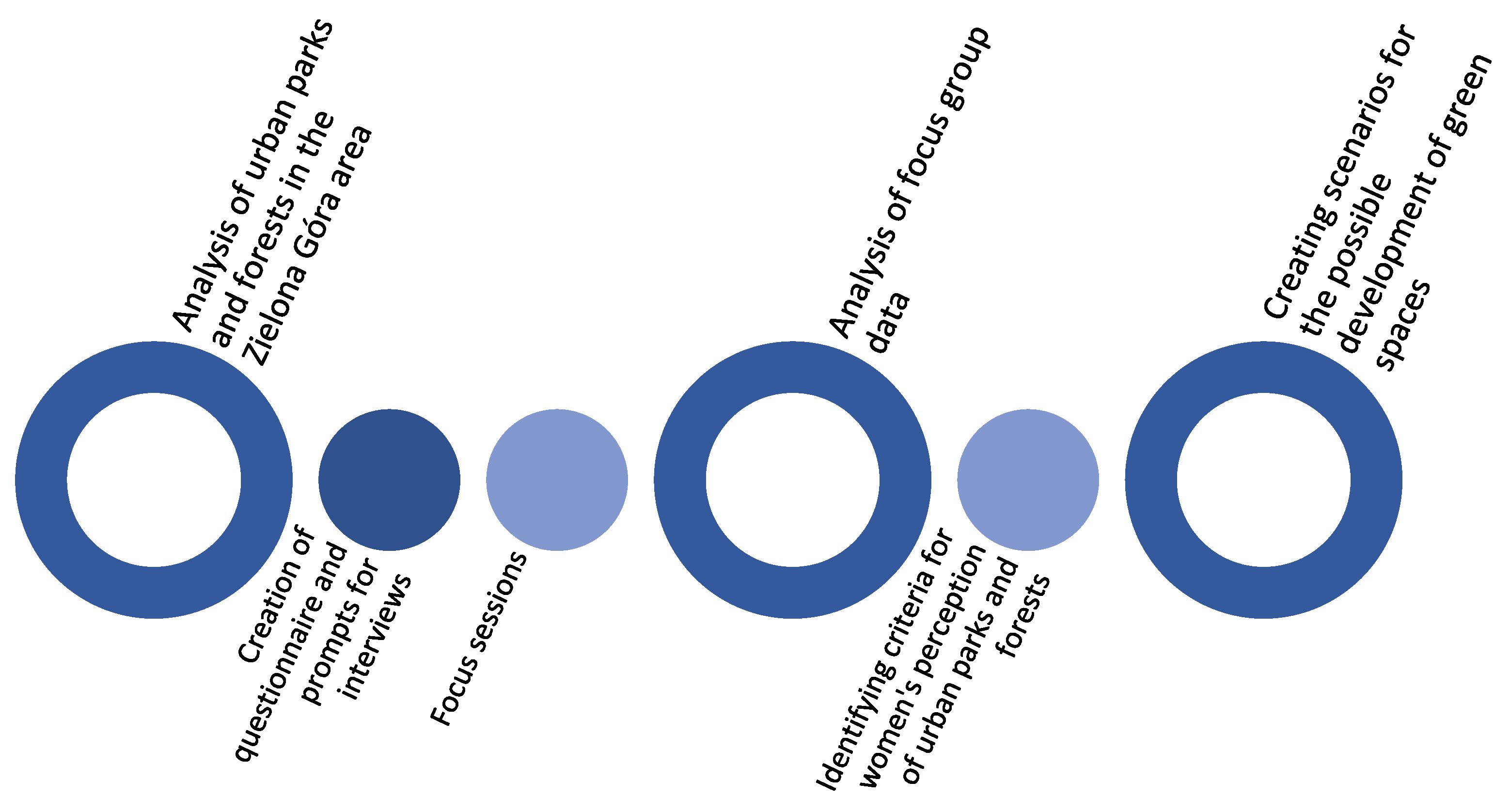

2. Materials and Methods

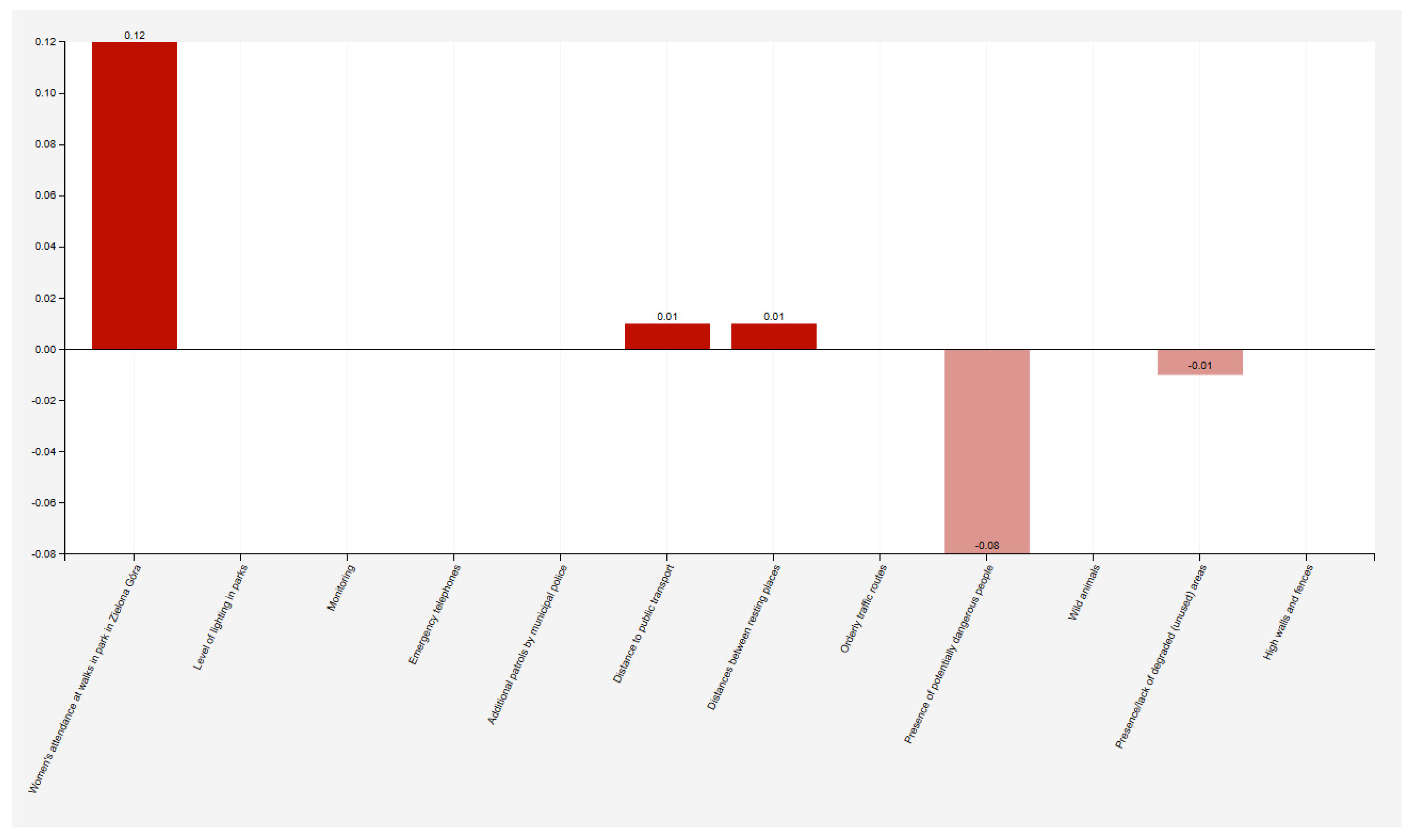

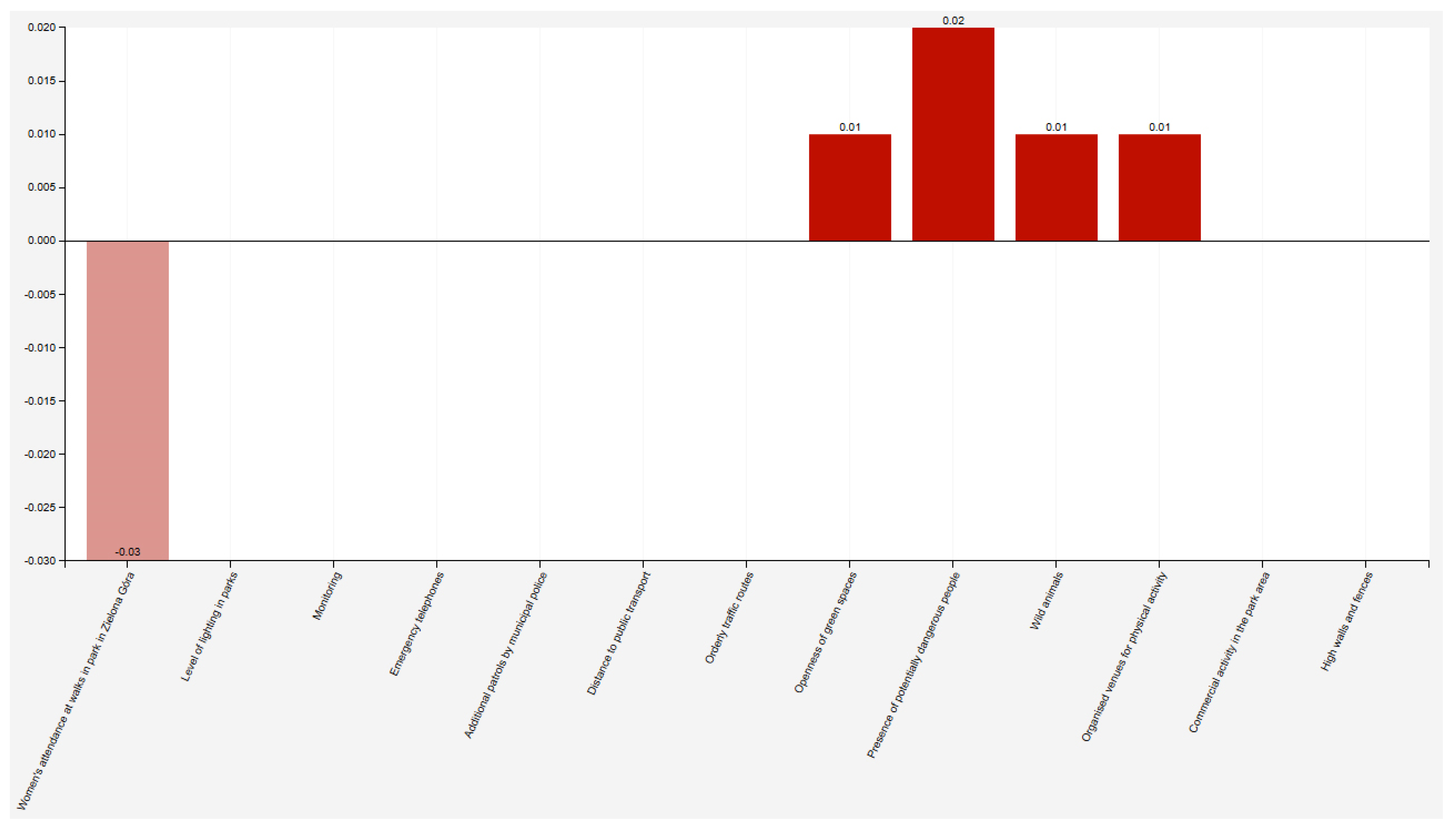

3. Results

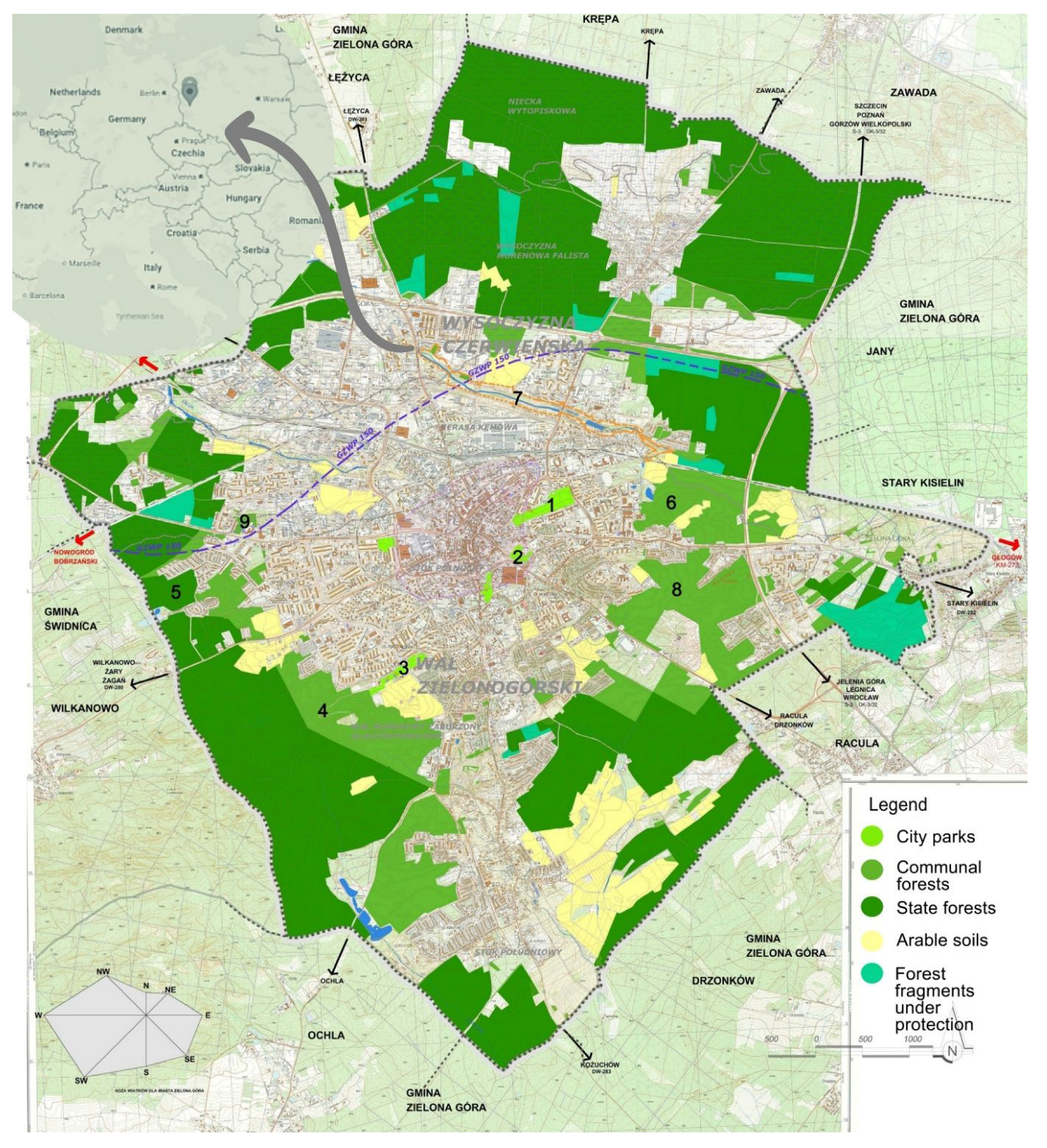

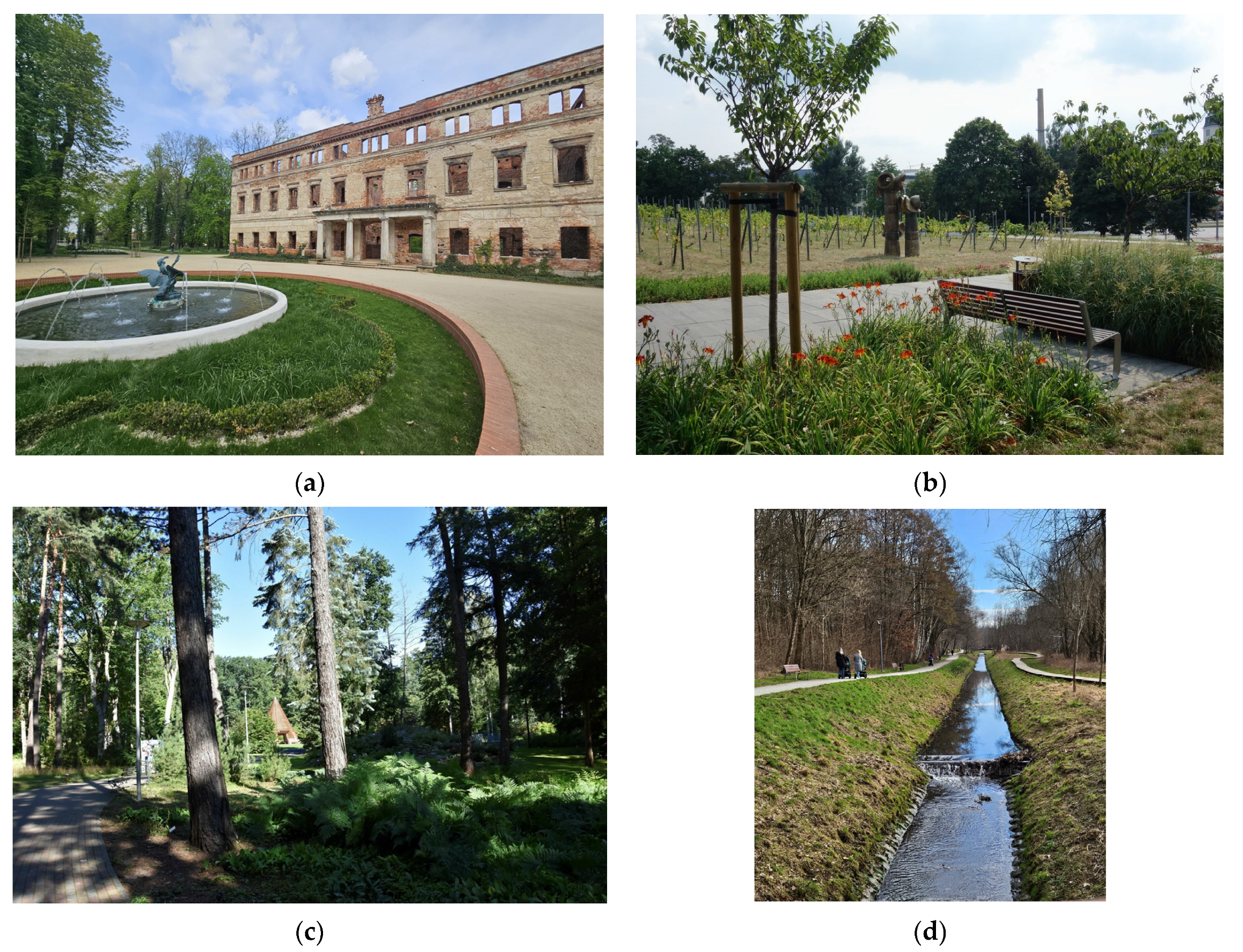

3.1. Analysis of Urban Parks/Forests in Zielona Góra

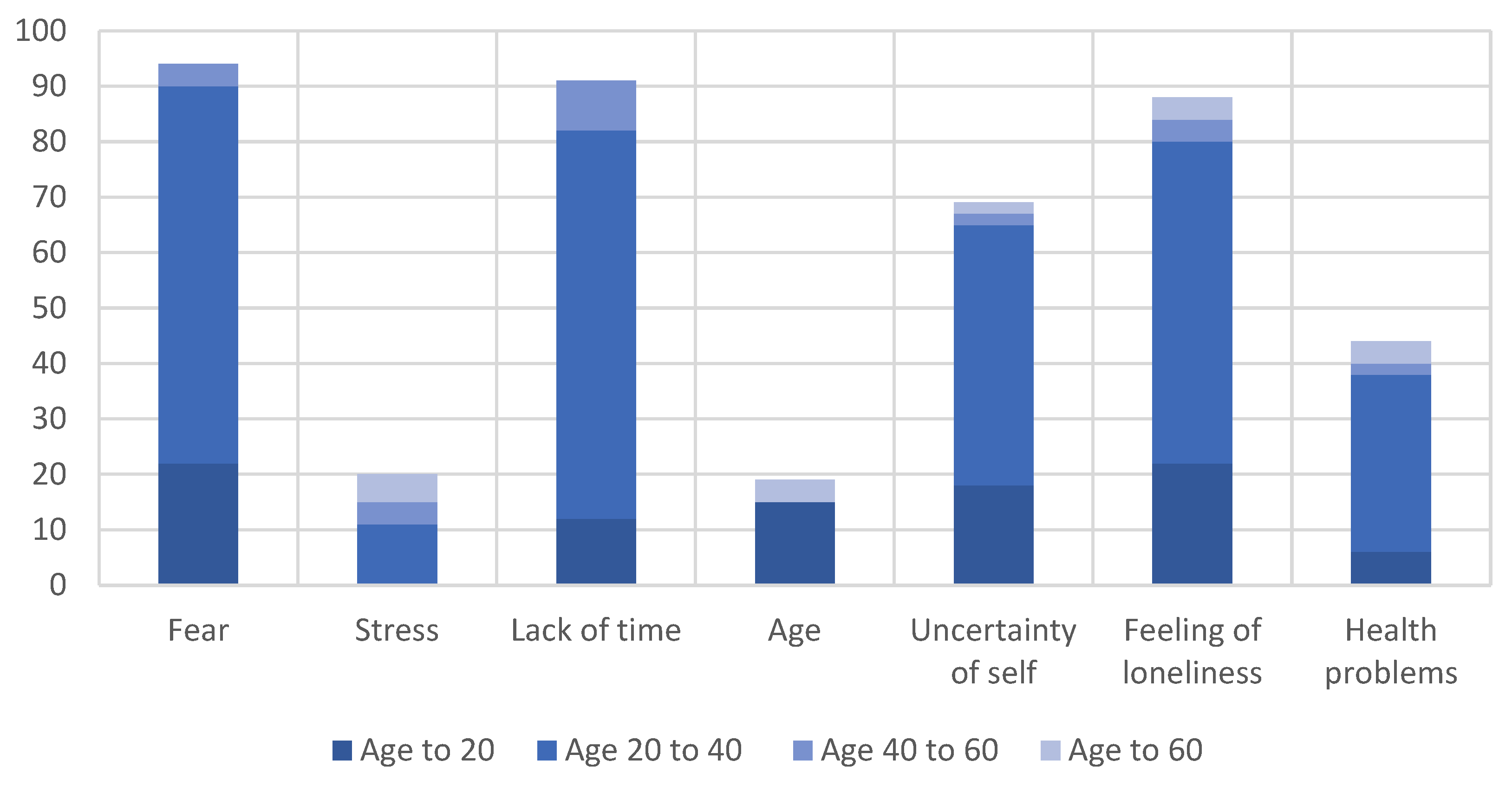

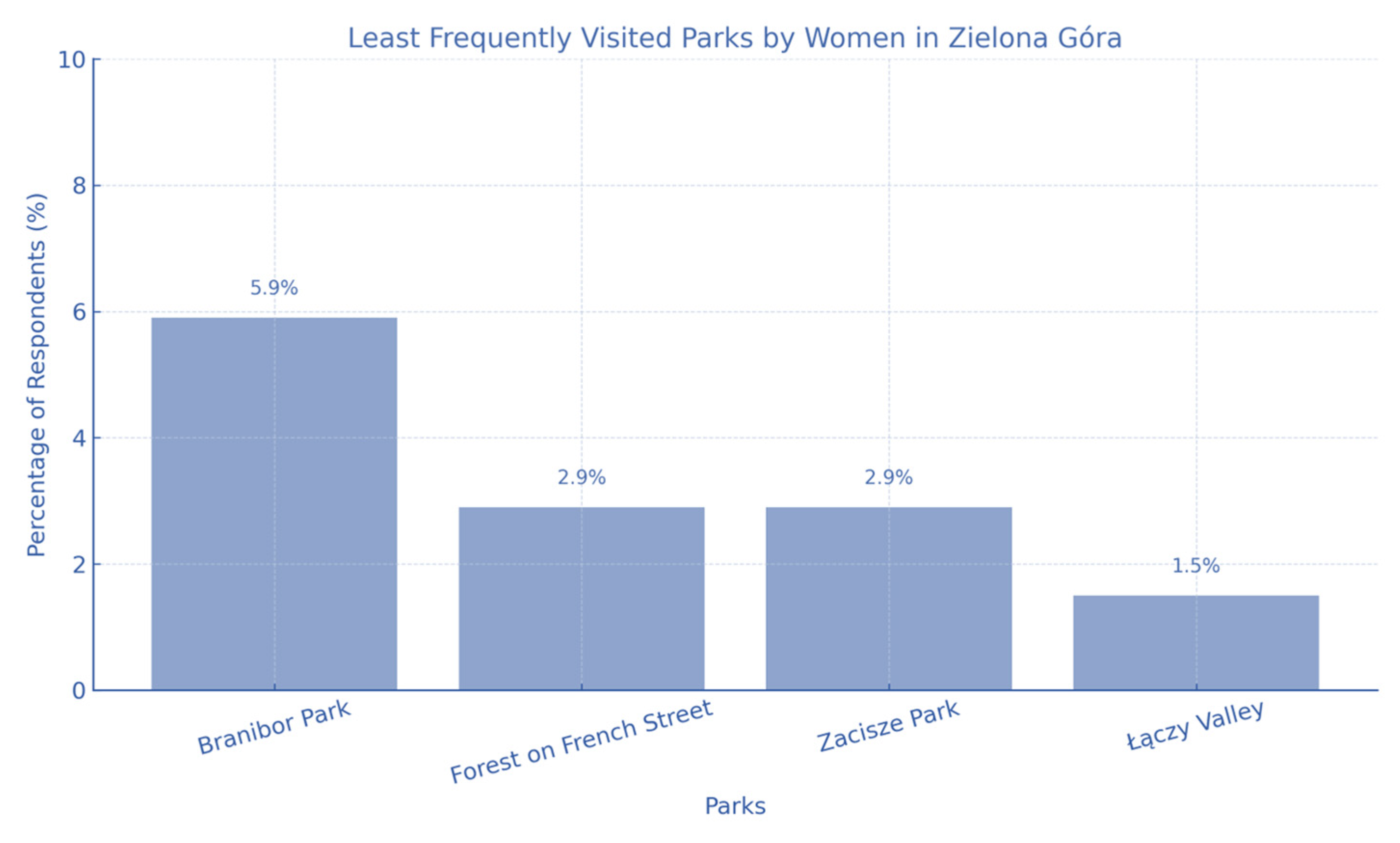

3.2. Analysis of Behavioural Experiences Among Women on the Use of Urban Parks/Forests

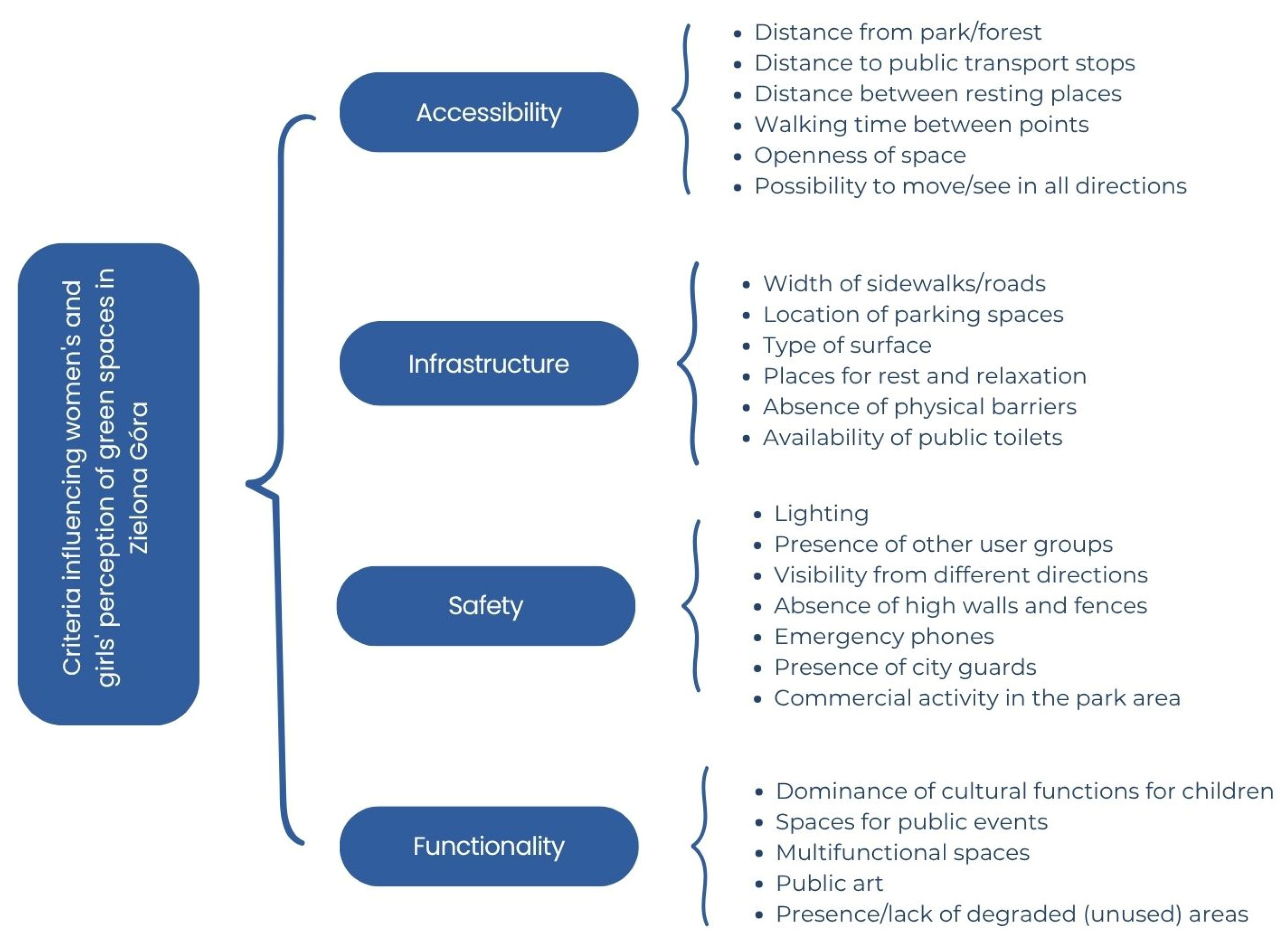

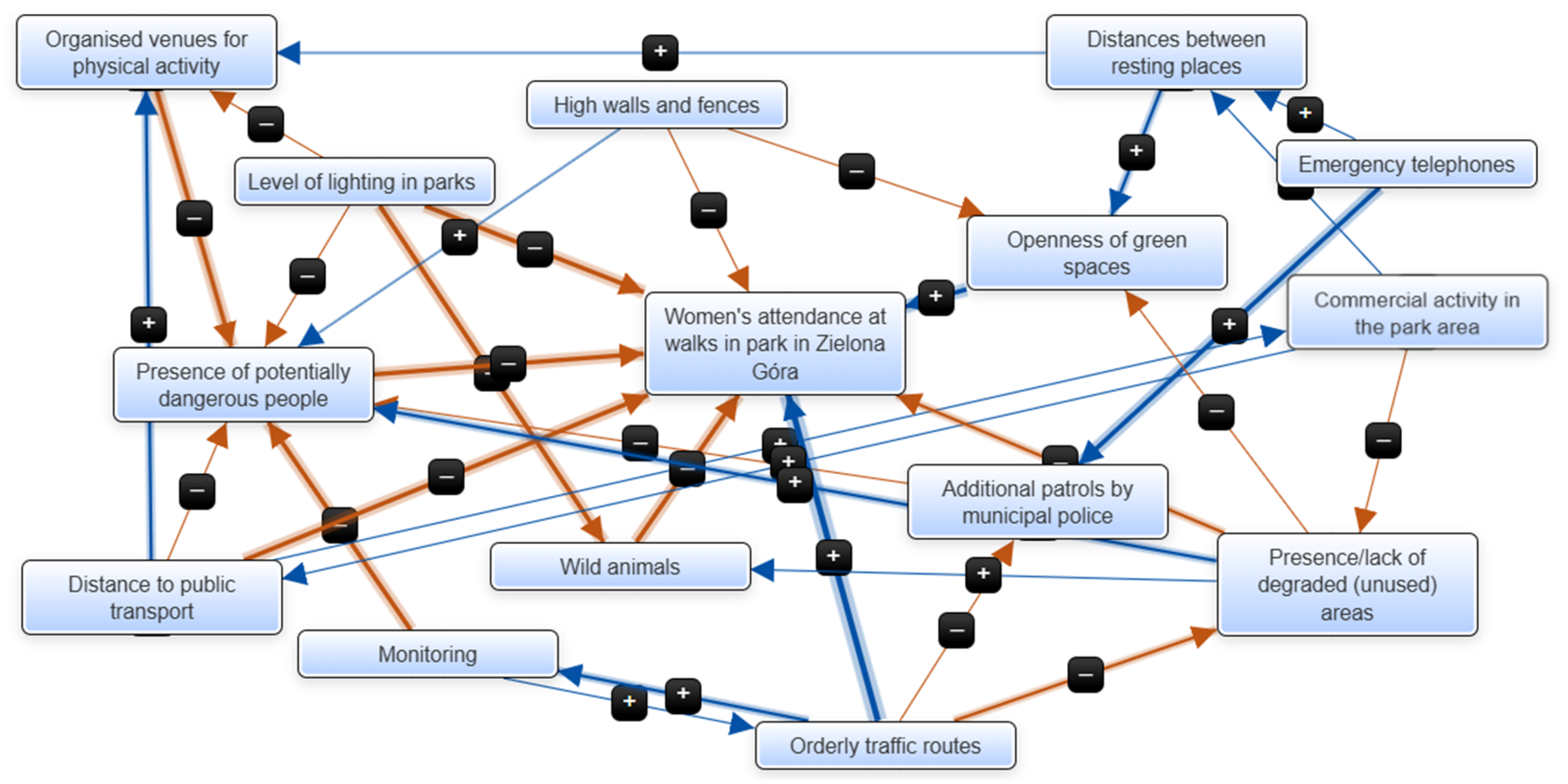

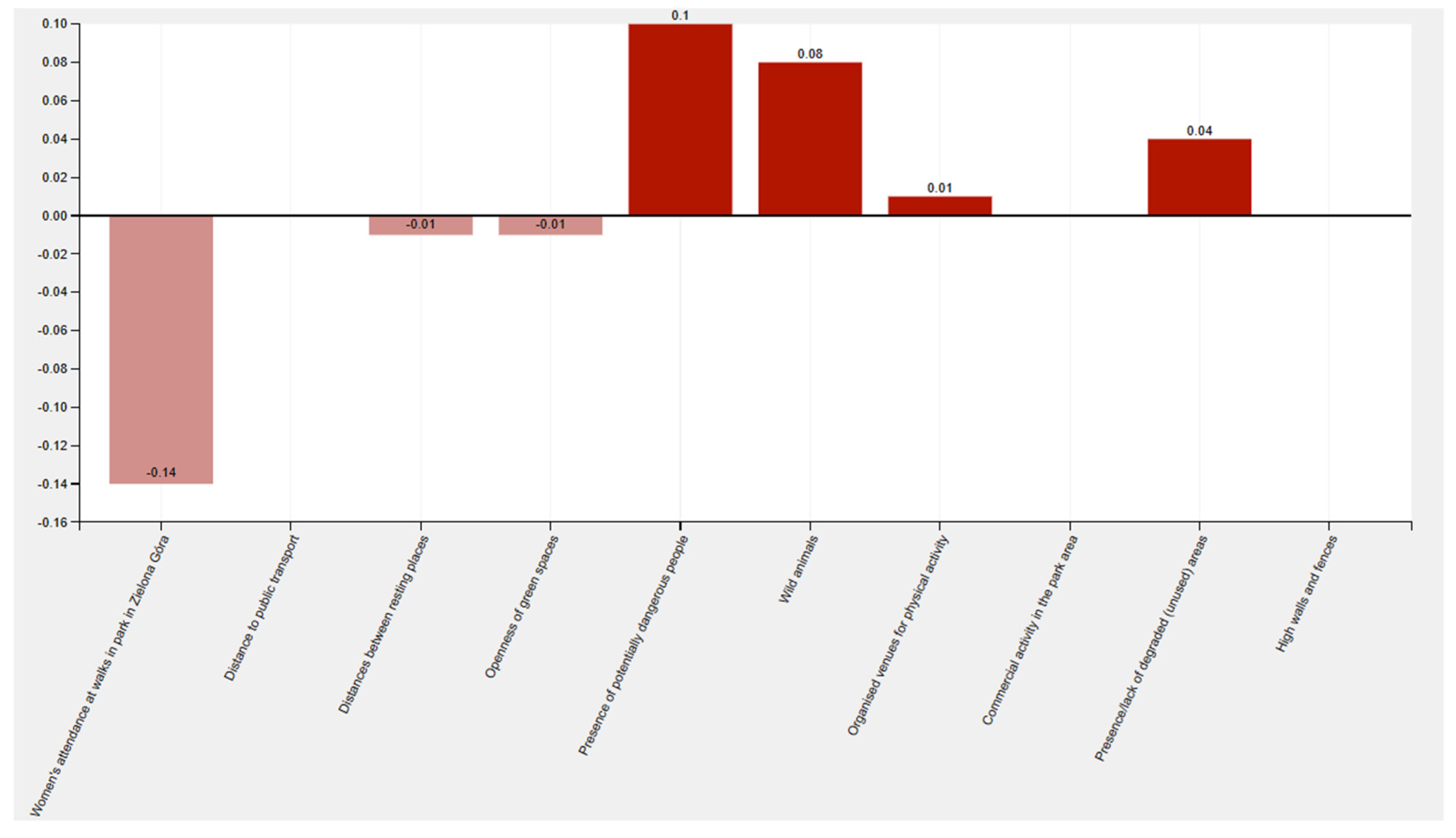

3.3. Making Decisions That Affect the Creation of More Accessible Green Spaces

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olmsted, F. Public Parks and the Extension of Towpaths; Riverside Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1870; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Visual Landscapes and Psychological Well-Being. Landsc. Res. 1979, 4, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelison, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/8672345/Health_Benefits_of_Gardens_in_Hospitals_Roger_S_Ulrich_Ph_D (accessed on 13 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The nature of the view from home: Psychological benefits. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.X.; Ma, X.L.; Huang, W.Z.; Luo, Y.N.; He, C.J.; Zhong, X.M.; Dadvand, P.; Browning, M.H.; Li, L.; Zou, X.G.; et al. Green space and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 301, 118990. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35181451/ (accessed on 5 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachariasz, A.; Jopek, D.; Kochel, L. Heritage and Environment: Greenery as a Climate Change Mitigation Factor in Selected UNESCO Sites in Krakow. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariasz, A.; Porada, K. Water in Krakow’s Gardens, Parks and Areas of Greenery. In Proceedings of the 4th World Multidisciplinary Civil Engineering-Architecture-Urban Planning Symposium (WMCAUS), Prague, Czech Republic, 17–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, J.; Wolch, J. Nature, race, and parks: Past research and future directions for geographic research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 743–765. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1555972/Nature_race_and_parks_past_research_and_future_directions_for_geographic_research (accessed on 9 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.; Carolyn, M.H.; Limb, M. People, parks and the urban green: A study of popular meanings and values for open spaces in the city. Urban Stud. 1988, 25, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblum, W. Racial and cultural groups on the beach. Ethn. Groups 1983, 5, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. About Her City. Available online: https://hercity.org/about (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- McDowell, L.; Bowlby, S.R. Teaching Feminist Geography. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 1983, 7, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinsky, W.; Monk, J.; Hanson, S. Women and Geography: A Review and Prospectus. Progress. Human. Geogr. 1982, 6, 317–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K.A.; Paxson, L. Women and urban public space. Public Places Spaces 1989, 10, 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liz, B. Gender, Class, and Urban Space: Public and Private Space in Contemporary Urban Landscapes, Urban. Geography 1998, 19, 160–185. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, L.; Burton, E.J. Neighbourhoods for life: Designing dementia-friendly outdoor environments. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2006, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K. The ethic of care and women’s experiences of public space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandogana, O.; Ilhan, B.S. Fear of Crime in Public Spaces: From the View of Women Living in Cities. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K. Embassies and Sanctuaries: Women’s Experiences of Race and Fear in Public Space. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1999, 17, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.B. TEN. Out of Place: Gender, Public Places, and Situational Disadvantage; University of California Press: Okland, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, D.; Singh, P. Effect of Design of Public Open Spaces on the Perception of Safety of Women. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2016, 3, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Krenichyn, K. Women and physical activity in an urban park: Enrichment and support through an ethic of care. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.R.; Jangjoo, S. Women’s preferences and urban space: Relationship between built environment and women’s presence in urban public spaces in Iran. Cities 2022, 126, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, A.; Struzik, J. Gender a Bezpieczeństwo—Utopie o Przyjaznym Mieście. In Utopie Kobiet: 100 lat Praw Wyborczych Kobiet (1918–2018); Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2019; pp. 209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gądecki, J. Gra w gender, gra w miasto. Kult. Polityka 2008, 4, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Łapniewska, Z.; Puzon, K. Gender i miasto. In Szlakiem Głosu: Tożsamości Mniejszościowe w Przestrzeni Miasta; Stowarzyszenie Arteria: Gdańsk, Poland, 2016; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, L.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Orsega-Smith, E. An examination of park preferencesand behaviors among urban residents: The role of residential location, race and age. LeisureSciences 2002, 24, 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Population. Population Status and Structure and Natural Movement in Territorial Section in 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-stan-i-struktura-ludnosci-oraz-ruch-naturalny-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2023-r-stan-w-dniu-31-12,6,36.html (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Powierzchnia i Ludność w Przekroju Terytorialnym w 2024 Roku. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/powierzchnia-i-ludnosc-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2024-roku,7,21.html (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- STATYSTYKA. Available online: https://statystyka.policja.pl/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Amendment Adopted by the 59th WMA General Assembly, Seoul, Republic of Korea, October. World Medical Association. Seoul, Republic of Korea. 2008. Available online: https://www.wma.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/DoH-Oct2008.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Kosko, B. Adaptive inference in Fuzzy Knowledge Network. In Readings in Fuzzy Sets fir Intelligent System; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 888–891. [Google Scholar]

- Kosko, B. Fuzzy cognitive maps. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1986, 24, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nápoles, G.; Grau, I.; Concepción, L.; Koutsoviti Koumeri, L.; Papa, J.P. Modeling implicit bias with fuzzy cognitive maps. Neurcomputing 2022, 481, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandr, C. Język wzorców. Miasta, Budynki, Konstrukcja; Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne: Gdańsk, Poland, 2008; p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphere as a Fundamental Concept of a New Aesthetics. Thesis Elev. 1993, 36, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebre, H. Du Rural a l’Urban, Propositions Pour un Nouvel Urbanisme. 2001. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/629323158/LEFEBVRE-Henri-Du-rural-a-l-urbain (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Rigolon, A. A complex landscape of inequity in access to urban parks: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 153, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, R. Women and the elderly in Chicago’s public parks. Leis. Sci. 1994, 16, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sister, C.; Wolch, J.; Wilson, J. Got green? addressing environmental justice in park provision. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravitz-Sela, S.; Shach-Pinsly, D.; Bryt, O.; Plaut, P. Leveraging City Cameras for Human Behavior Analysis in Urban Parks: A Smart City Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadgar, A.; Nyka, L.; Salata, S. Advancing urban flood resilience: A systematic review. Land 2024, 13, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadgar, A.; Luciani, G.; Nyka, L. Spatial allocation of nature-based solutions. Land Use Policy 2025, 150, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badach, J.; Szczepański, J.; Bonenberg, W.; Gębicki, J.; Nyka, L. Developing the urban blue-green infrastructure as a tool for urban air quality management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsec, S.; Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, M.; Żabicka, A.; Gil-Mastalerczyk, J.; Gawlak, A. Human-centered systems thinking in technology-enhanced sustainable and inclusive architectural design. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Number of Female Participants | Average Age (Range) | Recruitment Methods | The Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 71 (60–85) | Recruited directly in parks and urban forests | In-depth interview |

| 2 | 4 | 42 (30–55) | Recruited at the survey authors’ place of work | In-depth interview |

| 3 | 8 | 39 (30–50) | Recruited at respondents’ place of work | In-depth interview/the online questionnaire |

| 4 | 184 | 31 (18–45) | Persons responding to the online questionnaire | The online questionnaire |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Name of Park/Forest | Brook | Pond | Hill | Flower Beds | Decorative Grasses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gęśnik Valley | + | − | − | + | + |

| Łączy Valley | + | − | + | − | − |

| Hermit Valley | + | − | − | − | − |

| Millennium Park | + | − | − | + | + |

| Wine Park | − | − | + | + | + |

| St. Trinity Park | − | − | − | − | − |

| J. Sowiński Park | − | + | − | + | + |

| Piast Park | + | − | − | + | + |

| Poets’ Park | + | − | + | − | − |

| Braniborski Park | − | − | + | − | − |

| Piast Hills | + | + | + | − | − |

| Zacisze Park | − | − | − | − | − |

| Botanical Garden UZ | − | − | − | + | + |

| Zatonie Park | − | − | + | + | + |

| Forest on French Street | − | − | − | − | − |

| A park on the Mazursky estate | + | − | − | + | + |

| Vagmostaw | + | + | − | − | − |

| Meadows by the Silesian Estate | − | − | + | − | − |

| Name of Park/Forest | Paved Paths | Unpaved Paths | Benches | Tables | Playground | Gym | Hiking Paths | Educational Facilities | Cycle Paths | Places to Relax | Café | Fountain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gęśnik Valley | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| Łączy Valley | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hermit Valley | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Millennium Park | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Wine Park | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| St. Trinity Park | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| J. Sowiński Park | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Piast Park | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| Poets’ Park | − | + | +/− | +/− | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Braniborski Park | − | + | +/− | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Piast Hills | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Zacisze Park | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| Botanical Garden UZ | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Zatonie Park | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Forest on French Street | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| A park on the Mazursky estate | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| Vagmostaw | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Meadows by the Silesian Estate | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Forests by the Communal Cemetery | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Open-Ended Response | Category | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Better lighting | Safety/Infrastructure | Frequently mentioned |

| Fencing against wild animals | Safety | Mainly related to forested parks |

| CCTV monitoring | Safety | Mentioned in various locations |

| Public toilets | Infrastructure | Noted especially by respondents with children |

| Well-marked paths | Infrastructure | Related to navigation and accessibility |

| Visibility in space (e.g., transparent shrubs, low vegetation) | Safety/Spatial design | Reflects concerns about isolation |

| Emergency contact points (e.g., police call buttons) | Safety/Technology | Less frequent but clearly articulated |

| Proximity to public transportation stops | Accessibility/Infrastructure | Highlighted by elderly respondents and parents |

| Open-ended response | Category | Remarks |

| Key FCM Variable | Causal Relations in the Model (Influence on Other Variables) | Recommended Actions | Priority Under Limited Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of Safety | Strongly affects women’s presence, use of infrastructure and physical activity | Install lighting; CCTV cameras; Regular patrols by municipal services | High |

| Spatial Legibility | Enhances orientation and autonomy, especially for elderly women | Design coherent pedestrian paths; Avoid “dead zones” | Medium–High |

| Infrastructure Accessibility | Conditions affecting the possibility of physical activity, rest and family use | Add small-scale infrastructure; Children’s playgrounds | Medium |

| Walking Paths | Enhance access, safety, recreation and connectivity between functions | Maintain pathways; Illuminate walking routes; Link to public transport | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skiba, M.A.; Abramiuk, I. Women’s Preferences and Perspectives on the Use of Parks and Urban Forests: A Case Study. Land 2025, 14, 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071345

Skiba MA, Abramiuk I. Women’s Preferences and Perspectives on the Use of Parks and Urban Forests: A Case Study. Land. 2025; 14(7):1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071345

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkiba, Marta Anna, and Inna Abramiuk. 2025. "Women’s Preferences and Perspectives on the Use of Parks and Urban Forests: A Case Study" Land 14, no. 7: 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071345

APA StyleSkiba, M. A., & Abramiuk, I. (2025). Women’s Preferences and Perspectives on the Use of Parks and Urban Forests: A Case Study. Land, 14(7), 1345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071345