Abstract

Synergizing agricultural heritage conservation with tourism utilization is pivotal for sustainable regional development. Using a difference-in-differences (DID) method and entropy weight method (EWM), this study comparatively analyzed the economic resilience of two UNESCO agricultural heritage sites in China: the Wujiang Silk Culture System and the Longji Terraces in Longsheng, from 2019 to 2023. The results revealed that heritage certification significantly promotes tourism growth, increasing revenue in Wujiang by 12.5% and visitor numbers in Longsheng by 18.3%. However, the resilience mechanisms varied distinctly between the sites: Wujiang displayed a market-driven resilience pattern characterized by effective cultural tourism integration, whereas Longsheng remained vulnerable due to resource dependency and infrastructural constraints. Further, Wujiang’s robust policy framework involving heritage conservation, tourism development, and ecological compensation fostered sustained resilience, albeit facing long-term challenges such as potential cultural commodification. This research contributes theoretically by quantifying the resilience disparities via spatial econometric analyses, identifying market-institution drivers, and proposing a “Four-Dimensional Optimization Matrix”, integrating value activation, infrastructure enhancement, industrial symbiosis, and adaptive governance. Practically, it provides tailored policy insights for improving resilience, avoiding over-commercialization, and promoting sustainable tourism practices applicable globally, particularly in developing economies managing heritage sites.

1. Introduction

Since the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) initiated the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) project in 2002 [1], agricultural heritage has gained increasing attention globally, fostering rich discussions in academia and policy circles regarding heritage conservation and sustainable tourism utilization. Agricultural heritage systems (AHS) preserve traditional agricultural practices, landscapes, and knowledge systems, representing significant ecological, cultural, and economic values that are crucial for rural revitalization and sustainable development [2,3]. Heritage tourism, as an effective approach linking cultural preservation with economic development, has gained extensive academic support, given its potential to generate substantial regional economic benefits and cultural dissemination [4,5]. However, rapid tourism growth introduces challenges, including ecological degradation, cultural dilution, and risks associated with over-commercialization [6,7,8]. Thus, a resilience mechanism that balances economic growth and cultural authenticity is essential.

Economic resilience, defined as the capacity of a regional economic system to withstand, adapt to, and quickly recover from external shocks, is particularly relevant for agricultural heritage sites, where economic stability is closely tied to tourism performance amid market fluctuations, seasonal variability, and changing policy environments [9]. Although previous studies have explored the relationships between tourism and economic resilience in various contexts [4,10], limited research has explicitly focused on agricultural heritage tourism economies and their distinct resilience patterns.

This study seeks to address this gap by comparatively analyzing two representative UNESCO-listed agricultural heritage sites in China: the Wujiang Silk Culture System in Jiangsu Province and the Longji Terraces in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Wujiang, characterized by its advanced water network and plain topography, is historically renowned for its silk culture and its unique agricultural system integrating silk production with ecological tourism [11]. Wujiang has effectively capitalized on its advantageous location within the economically developed Yangtze River Delta, utilizing sophisticated infrastructure, diversified cultural tourism integration, and institutional innovations. However, despite its significant achievements, Wujiang faces the risk of cultural commodification, where the pursuit of economic benefits may threaten its cultural authenticity and long-term sustainability.

In contrast, Longsheng County, featuring mountainous landscapes, karst topography, and distinct ethnic minority cultures, developed an agriculture-based tourism system centered around the Longji Terraces [12]. Despite strong governmental support and efforts in creating community-led tourism initiatives, Longsheng’s tourism economy remains vulnerable due to its heavy dependency on single-resource tourism and seasonal variability, coupled with infrastructure deficits [13]. The stark differences between these two sites in terms of geography, cultural heritage, infrastructure, and governance structures make them ideal for exploring the resilience mechanisms and sustainability pathways within agricultural heritage tourism.

Utilizing a difference-in-differences (DID) methodology and the entropy weight method (EWM), this study empirically investigates the impact of heritage certification on regional tourism economies and systematically evaluates the key dimensions and factors influencing economic resilience. By doing so, it aims to contribute theoretically by elucidating how heritage certification enhances tourism economies’ resilience through market-institution synergies, infrastructure upgrades, and digital innovation. Practically, this study proposes a global–local governance framework, incorporating strategies to avoid over-commercialization, ensure cultural sustainability, and foster community-based tourism. The insights derived from this comparative analysis offer valuable theoretical contributions and policy recommendations for the sustainable development of agricultural heritage tourism economies worldwide.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Foundations of Agricultural Heritage

Agricultural heritage refers to traditional agricultural systems and associated cultural practices that are developed through adaptation to the natural environment over generations, embodying significant ecological, historical, and cultural values [2,3]. Since the introduction of the GIAHS by the FAO in 2002, scholars have extensively explored these systems’ inherent values and implications [3,4,14,15]. Key studies highlight that agricultural heritage systems sustain biodiversity, protect ecological environments, and maintain cultural traditions, thus contributing substantially to rural sustainable development [16,17].

Despite these recognized values, the effective preservation and sustainable utilization of agricultural heritage face significant practical challenges. Rapid urbanization, modernization, and insufficient funding have often resulted in the erosion of traditional practices and landscapes [18]. Additionally, tensions exist between conservation and economic exploitation, raising questions about balancing economic growth with cultural authenticity [6,8].

2.2. Heritage Tourism

Heritage tourism, defined as tourism driven by cultural heritage assets, has become widely recognized as an effective method for achieving both economic diversification and cultural preservation [19,20]. Richards noted heritage tourism’s potential for stimulating economic development while simultaneously highlighting risks such as cultural commodification and loss of authenticity [21]. Consequently, sustainable tourism development frameworks have emerged, emphasizing the integration of heritage protection with economic activities to ensure long-term viability and resilience [22].

Theoretical frameworks, such as sustainable tourism and economic diversification theories, provide robust foundations for analyzing the role of tourism in economic resilience. Sustainable tourism theory stresses that tourism should meet present economic, socio-cultural, and environmental needs without compromising future capacities [23]. Economic diversification theory further asserts that diversified tourism economies are better positioned to withstand external shocks compared to economies dependent on single-resource tourism [20,24]. Empirical studies support these theories, demonstrating that regions embracing diversified tourism models exhibit stronger economic resilience against external disruptions [25,26].

2.3. Agricultural Heritage Tourism (AHS)

With the quantitative shift in the study of agricultural heritage, the academic community has revealed the interaction mechanism and integration path between agricultural heritage and the tourism industry from multiple dimensions. In terms of spatial correlation characteristics, macro studies have shown that the spatial distribution of China’s agricultural heritage is significantly positively correlated with the development of the tourism industry, revealing the fundamental role of heritage resource endowment in the regional tourism economy [10,27,28]. At the meso level, regional empirical studies have shown that the tourism industry and agricultural heritage in Liaoning, Southwest China, and other regions have maintained a coupled and coordinated trend, among which farmland landscapes and tea culture heritage have stronger tourism adaptability [29]. Micro-level case studies have further deepened this understanding. By constructing an evaluation system for the integration degree of the “three industries”, it was found that in heritage sites represented by the Hani Rice Terraces, the tertiary industry centered on tourism has the highest contribution rate to industrial integration [30]. In terms of research methods, the coupling coordination degree model has become the mainstream analytical tool, verifying the high coupling characteristics of the heritage system and the tourism industry [10,12,13,31]. The research has also identified core influencing factors, such as resource elements, policy guarantees, and production innovation, providing a basis for optimizing the coordinated development of the two [32]. These achievements collectively confirm the significant value of agricultural heritage as a distinctive tourism resource and lay a theoretical foundation for sustainable tourism development in heritage sites.

Integrating agricultural heritage with tourism has produced multiple successful cases worldwide, illustrating the significant economic and cultural potential of such initiatives. Examples include the Hani Rice Terraces in Yunnan, China, and the Noto Peninsula in Japan, where tourism has successfully generated economic benefits and community empowerment [33,34]. Yet, these practices also reveal common challenges, including cultural commodification, over-tourism pressures, ecological degradation, and conflicts over resource allocation [35,36,37]. For instance, rapid tourism growth has sometimes resulted in the erosion of traditional agricultural practices, undermining the authenticity and sustainability of heritage sites [38,39].

In China, studies have explored how regions like Yunnan’s Honghe Hani Terraces successfully utilize community-based tourism management to balance cultural preservation with economic benefits [40,41]. Conversely, sites with limited infrastructure and overly resource-dependent tourism models, such as certain remote terrace landscapes, struggle to achieve sustained economic resilience [42,43,44]. Therefore, a resilient mechanism is needed to balance the conflict between cultural protection and tourism development. In response to this issue, scholars have proposed various strategies, such as the integration of functions and cultural tourism; the application of digital technologies like virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality(AR) is also regarded as an innovative direction for heritage tourism development [45,46]. However, despite the potential of digital technologies (e.g., VR and AR), their implementation in agricultural heritage tourism faces practical challenges such as high costs, technological barriers, and varying levels of local acceptance.

2.4. Economic Resilience in AHS

Economic resilience, broadly understood as the capacity of an economic system to absorb shocks and adapt to external changes, is increasingly relevant in tourism research. Resilience theory emphasizes adaptability, resource diversification, and robust governance as key drivers of resilience [47,48]. However, the current literature lacks systematic empirical research specifically addressing economic resilience within agricultural heritage tourism contexts.

Existing studies have predominantly employed qualitative or descriptive methods, seldom utilizing quantitative analysis to explore resilience dynamics [8,24,49,50]. This gap restricts a comprehensive understanding of how agricultural heritage certification, governance structures, infrastructure development, and tourism market dynamics contribute quantitatively to economic resilience. Additionally, comparative empirical studies focusing on different types of agricultural heritage sites—particularly contrasting market-driven and resource-dependent models—are notably scarce, leaving significant theoretical and practical uncertainties.

Thus, this study aims to fill these theoretical and empirical gaps by systematically examining how agricultural heritage certification affects tourism economies and identifying resilience determinants. By comparing two distinct cases—the Wujiang Silk Culture System and Longji Terraces—this study provides empirical insights into the divergent pathways of resilience and their underlying mechanisms. This approach aims to bridge existing theoretical and practical gaps, contributing to resilience theory and offering policy implications for the sustainable management of heritage tourism.

3. Methodology and Materials

This section outlines the empirical methodology and data framework employed to investigate the influence of agricultural heritage certification on tourism economies and their economic resilience.

3.1. Study Areas

This study focuses on two UNESCO-listed agricultural heritage sites in China: the Wujiang Silk Culture System and the Longsheng Longji Terraces, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Wujiang, located in Jiangsu Province, is selected due to its distinct market-driven and diversified tourism economy, benefiting from robust infrastructure and proximity to the economically developed Yangtze River Delta. In contrast, Longsheng County in Guangxi Province represents resource-dependent tourism economies that rely heavily on singular landscape attractions with limited infrastructure support. These contrasting characteristics provide an ideal context to explore divergent resilience pathways.

Figure 1.

Agricultural heritage sites in Wujiang, Jiangsu Province, China.

Figure 2.

Agricultural heritage sites in Longsheng, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China.

3.2. Data Sources

This study utilizes county-level panel data from 2010 to 2019, collected from statistical bulletins, government reports, and databases such as the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) and EPS databases. Agricultural heritage certification data were obtained from official FAO and Chinese governmental sources. Data gaps were filled using interpolation methods to maintain dataset completeness and accuracy.

The primary dependent variables selected to measure tourism growth clearly include two indicators: per capita tourism income (reflecting economic gains from tourism) and per capita tourist arrivals (indicating visitor demand and market stability). These variables comprehensively capture tourism growth and its economic impacts, clarifying the measurement ambiguity pointed out by reviewers.

Control variables include local economic development (GDP per capita), infrastructure development (road density and accommodation facilities), financial development (loans from financial institutions), education levels, transportation accessibility, and tertiary industry development levels. These variables were chosen based on their established significance in regional economic resilience studies [51,52].

In selecting indicators for tourism growth, this study specifically utilized per capita tourism income and per capita tourist arrivals due to the data availability, consistency across regions, and their direct reflection of economic impact and market demand. Alternative indicators, such as tourists’ length of stay, were not included due to inconsistent reporting standards and significant data gaps across the studied regions.

The qualitative data collected from stakeholder interviews and field observations were analyzed using thematic analysis. Interview transcripts were systematically coded to identify recurring themes, which were subsequently integrated with quantitative findings to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the resilience mechanisms and contextual nuances.

Primary data were collected through extensive fieldwork at the selected heritage sites, incorporating interviews, observations, and official documents. Missing values were addressed through interpolation methods to ensure dataset integrity. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 15.1 software, ensuring rigorous econometric testing and validation.

3.3. Analytical Methods

This study employs two key econometric approaches:

The DID Model: This model evaluates how heritage certification affects regional tourism economies by comparing certified (treatment group) and non-certified regions (control group). The parallel trend assumption was tested using an event study approach to validate the DID model [53,54]. Among them, the dependent variable is the tourism economic performance, measured by the logarithm of per capita tourism income and the number of tourist arrivals. The independent variable is the status of agricultural heritage certification (a binary variable), while the control variables include local economic development, infrastructure, financial development, education level, transportation accessibility, and the development of the tertiary industry [55,56].

EWM: To objectively measure tourism-related economic resilience, the EWM was employed. This method objectively assigns weights to resilience indicators, reducing subjective bias. It assesses supply resilience from the contribution to the tourism industry, the number of travel agencies, traditional villages, and scenic spots. It evaluates demand resilience based on tourist density, per capita tourism consumption, and tourism transportation pressure. It assesses structural resilience from the rationality of industrial structure, the number of grassroots agricultural technicians, green innovation patents, and the internet penetration rate. It evaluates management resilience from fixed asset investments and the intensity of environmental supervision [57,58,59,60].

3.4. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

This study aims to investigate how agricultural heritage certification influences the development and resilience of regional tourism economies, particularly within the context of heritage tourism. Drawing on a comprehensive literature review and theoretical synthesis, this study constructs a conceptual framework that integrates heritage certification, cultural tourism integration, infrastructure development, and institutional governance as key determinants of tourism-related economic resilience.

To guide the empirical analysis, the research is structured around the following objectives:

- To evaluate the extent to which agricultural heritage certification contributes to regional tourism development, particularly in terms of revenue growth and visitor volume.

- To compare the resilience pathways of market-driven versus resource-dependent agricultural heritage tourism systems.

- To identify and quantify the key structural, institutional, and technological drivers that influence tourism-related economic resilience in agricultural heritage sites.

Building on these objectives, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1.

Agricultural heritage certification significantly enhances regional tourism performance, as reflected in increased tourism revenue and visitor numbers.

H2.

Market-driven agricultural heritage sites (e.g., Wujiang) demonstrate higher levels of tourism-related economic resilience than resource-dependent sites (e.g., Longsheng).

H3.

Greater integration of cultural tourism with local industrial systems positively contributes to resilience by promoting economic diversification and mitigating external shocks.

H4.

Digital infrastructure and supportive policy frameworks mediate the relationship between heritage certification and tourism resilience, strengthening local adaptive capacity.

To test these hypotheses, this study adopts a mixed-method approach. A DID model is employed to identify the causal impact of agricultural heritage certification on tourism development, while the EWM is used to measure and compare the multidimensional resilience of heritage tourism economies. The case analysis focuses on two contrasting sites—Wujiang and Longsheng—offering a comparative lens through which the mechanisms of resilience can be observed and evaluated.

4. Empirical Analysis

This study aims to systematically evaluate the impact of GIAHS on regional tourism economies and further measure the resilience of the tourism economies of agricultural heritage sites. Specifically, the core objectives of this research are (1) to quantify the impact of agricultural heritage on regional tourism economies, analyze its role in promoting tourism development, optimize the industrial structure, and enhance economic stability, and (2) to assess the resilience of the tourism economies of agricultural heritage sites, exploring their ability to adapt to external shocks such as market fluctuations, environmental changes, and policy adjustments, as well as identifying sustainable development paths.

4.1. DID Model

4.1.1. Model Construction and Variable Definition

This study uses the DID model to evaluate the impact of GIAHS on regional tourism economies. The model emphasizes capturing the effects of regional differences and temporal changes, ensuring accurate causal inference. Based on the agricultural heritage lists provided by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and the FAO, as of 2019, 98 counties were certified for at least one GIAHS [1]. Due to data availability constraints, 77 counties with agricultural heritage certification were selected as the treatment group, while the remaining non-certified counties served as the control group. The core explanatory variable was defined based on the certification year as 0 for counties that were not certified before that year and 1 for those that were certified thereafter.

The baseline regression model was constructed as follows:

where

is the dependent variable representing the tourism-related economic development level of a county in year . The log of per capita total tourism income and the log of per capita tourist arrivals are used as metrics reflecting changes in regional tourism economies.

is the core explanatory variable, indicating the certification status of agricultural heritage. It equals 1 if certified and 0 if not.

represents the control variables, including the local economic development (GDP per capita), infrastructure level (road density and accommodation facilities), financial development (number of financial institutions), basic education level (average years of schooling), transportation accessibility (highway coverage), and tertiary industry development (share of GDP from the tertiary sector).

captures the time fixed effects to control for the macroeconomic and policy changes at the national level.

captures the county fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity across counties.

is the error term.

In this model, the coefficient is of primary interest. If it is positive and statistically significant, it indicates that agricultural heritage certification has a positive effect on the economic development of regional tourism. The DID method controls for potential confounding factors such as time trends and regional heterogeneity, thus enhancing the reliability of causal inference and providing more accurate empirical evidence for tourism development in agricultural heritage sites.

4.1.2. Parallel Trend Assumption Test

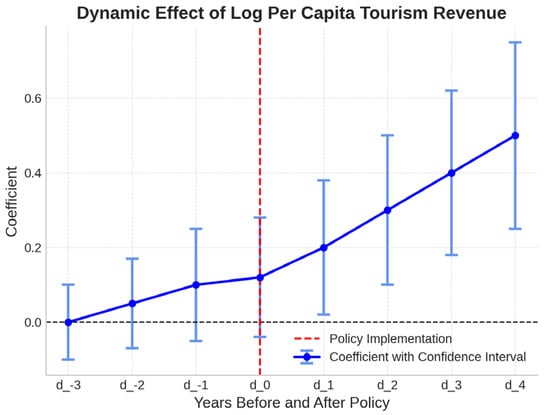

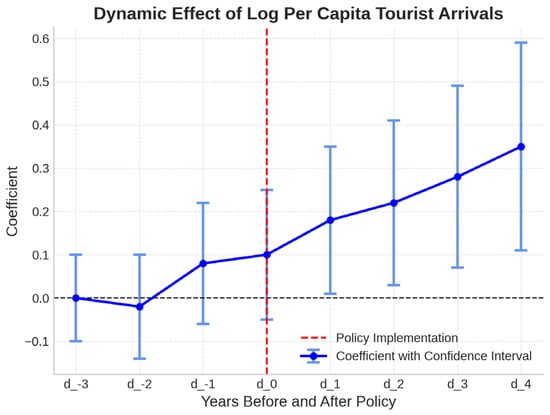

The parallel trend assumption is a critical assumption when using the DID method for causal inference. It posits that, before the policy intervention, the treatment group (counties with agricultural heritage certification) and the control group (counties without certification) should exhibit similar trends in tourism-related economic growth. If this assumption is violated, the DID estimates may be biased. To test this assumption, this study adopted an event study approach, constructing time dummy variables based on the policy implementation year. The dynamic effects of tourism-related economic growth before and after the policy are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

The dynamic effects of log per capita tourism revenue.

Figure 4.

The dynamic effects of log per capita tourist arrivals.

From the results in Figure 3 and Figure 4, it is evident that the coefficients in the 1–2 years before the policy implementation are statistically insignificant, indicating that there were no systematic differences in the economic trends relating to tourism between the treatment and control groups prior to the policy. This confirms that the parallel trend assumption holds. Therefore, the DID estimation is valid for causal inference, suggesting that the certification of agricultural heritage has a positive effect on regional tourism-related economic development. The impact of this certification on tourism economies intensifies over time, which may be driven by mechanisms such as brand effects, infrastructure improvements, and industrial synergies.

4.1.3. Variable Selection

This study aimed to explore the impact of GIAHS on regional tourism-related economic development. Since economic growth relating to tourism is influenced not only by agricultural heritage but also by various external factors, several control variables were introduced to ensure the robustness of the model estimates and the reliability of causal inference.

Dependent Variables: The first dependent variable was the log of per capita total tourism income, which measures the level of economic benefits from tourism. To eliminate the effects of inflation, this variable was deflated using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The second dependent variable was the log of per capita tourist arrivals, which captures the impact of agricultural heritage on attracting tourists.

Core Explanatory Variable: The core explanatory variable was the presence of the GIAHS, which was constructed based on the agricultural heritage lists published by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and the FAO. If a county was certified as an agricultural heritage site in a given year, the GIAHS variable was set to 1 for that and subsequent years; otherwise, it was set to 0.

Control Variables: To control for other factors influencing regional tourism economies, five categories of control variables were included and are described below.

Economic Development and Infrastructure: Economic development was measured using the log of per capita GDP (lnpgdp), while the infrastructure level was captured by the ratio of fixed asset investments to GDP (fixed) and the log of hospital and health center beds per 100 people (lnhosp).

Financial and Human Capital: Financial development was measured using the ratio of financial institution loans to GDP (fina), and human capital was proxied using the ratio of secondary school students to the total population (edu).

Transportation Accessibility: The impact of transportation infrastructure on tourism economies was assessed using the log ratio of county road mileage to county area (lnroad).

Tertiary Industry Development: Tourism, as a part of the tertiary sector, was evaluated based on the share of GDP from the tertiary industry (indu3), reflecting the supporting role of the service sector in the tourism economy.

In sum, this study systematically controlled for economic development, infrastructure, financial and human capital, transportation accessibility, and the development of the tertiary sector to ensure the scientific rigor and robustness of our empirical results. The definitions, calculation methods, and data sources for these variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable selection and indicator description.

4.1.4. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

The data for this study were sourced from four primary sections to ensure the reliability and representativeness of the research findings. First, data on the agricultural heritage list and the year of certification were obtained from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China to ensure the accuracy of the core explanatory variable. Second, data on the dependent variables, covering the years 2010 to 2019, were primarily sourced from county-level statistical bulletins and government reports, which were used to assess the impact of agricultural heritage on tourism economies. Third, data for the control variables were derived from the CSMAR Economic and Financial Database and the EPS Database, covering aspects such as economic development, infrastructure, financial capital, human capital, transportation, and the development of the tertiary sector to control for external factors that may influence the tourism economy. Fourth, for counties with missing values, interpolation methods were applied to fill in the gaps, reducing the potential bias caused by missing data. Based on the above data sources and processing methods, Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for the relevant variables. This study, through systematic data collection and processing, comprehensively evaluated the impact of agricultural heritage on tourism economies and further explored its long-term effects on regional economies.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of basic variables.

4.2. Entropy Weight Method

4.2.1. Model Construction and Application of the EWM

In this study, the EWM was selected as an effective tool for measuring the resilience of tourism economies. The advantage of the entropy method lies in its ability to objectively reflect the relative importance of each indicator in the comprehensive assessment of the tourism-related economic resilience of heritage sites, thereby avoiding the subjective bias that may arise from expert weighting. By applying the EWM, appropriate weights can be assigned to each evaluation indicator, leading to a more accurate assessment and comparison of the tourism-related economic resilience of heritage sites.

The calculation process of the EWM includes several important steps, which are outlined as follows:

- Constructing the Initial Decision Matrix

First, define the evaluation objects and indicators and construct a decision matrix, where each entry represents the value of the -th indicator for the -th evaluation object.

- Data Normalization

To eliminate the dimensional differences among indicators, the data must be standardized. For positive indicators, the following formula is used for standardization:

For negative indicators, the standardization formula is as follows:

After standardization, all data will be transformed into a range between 0 and 1, allowing for further analysis.

- Determining the Entropy Value for Each Indicator

The entropy value for each indicator is calculated as follows:

where is the proportion of the -th sample for the -th indicator. The entropy value reflects the uncertainty or disorder of the indicator’s distribution. A higher entropy value indicates a more uniform distribution of information, meaning that the indicator contributes less to the overall resilience. A lower entropy value indicates more concentrated information, implying that the indicator contributes more to resilience.

- Calculating the Divergence of Each Indicator

The divergence of each indicator is calculated based on the entropy value:

A greater divergence indicates that the indicator has a larger discriminatory power and makes a more significant contribution to the overall assessment.

- Determining the Weight for Each Indicator

Based on the divergence, the weight of each indicator is determined as follows:

This weight reflects the relative importance of each indicator in the resilience evaluation system.

- Comprehensive Index of Tourism-Related Economic Resilience

Finally, the comprehensive index of the tourism-related economic resilience of heritage sites is calculated using the weighted sum of the standardized values of each indicator:

This comprehensive index can be used to evaluate the tourism-related economic resilience levels of different heritage sites and provide a basis for their further development.

4.2.2. Indicator Selection and Explanation

This study constructed an economic resilience evaluation for the tourism system based on the resilience concept framework derived from traditional ecological thinking combined with the economic attributes of the tourism industry. The core of tourism-related economic resilience lies in the deep integration and mutual adaptability between the tourism industry and the regional economy. The steady development of the tourism market relies not only on the contributions of external visitors but also on the exploration of local residents’ consumption demands. The essence of the tourism economy is the tourism experience, and its robustness in the face of risks primarily depends on the stability of the service supply and the sustainability of tourist demand. Furthermore, building a diversified tourism economy and strengthening governments’ regulatory capacity is key to enhancing the resilience of tourism activities against social risks and accelerating recovery.

Based on this theoretical framework, this study focused on the practical development of two typical case areas and selected 13 indicators across four dimensions—supply resilience, demand resilience, structural resilience, and management resilience—to construct an economic resilience evaluation system for agricultural heritage tourism.

Within this framework, supply resilience measures the ability of tourism service providers to return to normal operations after external shocks, focusing on the supply side of tourism services. Demand resilience measures the ability of tourists to resume normal tourism activities and states in the face of risk disruptions, focusing on the demand side of tourism services. Structural resilience assesses the ability of the local economy to innovate and transform through digital or alternative forms of tourism in response to negative impacts from uncertain factors. Management resilience reflects the potential capacity of local governments to support the economic resilience of tourism, as demonstrated by their investment in and attention to the tourism industry and infrastructure development. Table 3 presents the specific indicator system.

Table 3.

Indicator system for assessing the economic resilience of tourism in heritage sites.

4.2.3. Data Sources and Necessity Analysis

The data for this study were derived from comprehensive field investigations conducted at the Wujiang Silk Culture System and the Longsheng Longji Rice Terraces System. The research team employed multiple methods, including structured questionnaires, in-depth interviews, official statistical data collection, and historical archive examination, ensuring the collection of accurate, multidimensional, and representative primary data. Extensive communication with local governments, tourism enterprises, community residents, and tourists further validated and enriched the dataset, providing empirical support for evaluating the economic resilience and tourism-related challenges at the two heritage sites.

Based on the tourism-related economic resilience evaluation system constructed through the EWM (see Table 3), this study specifically assessed panel data covering the period from 2019 to 2023 for both Wujiang and Longsheng. The EWM, an objective weighting method, effectively addresses the potential subjectivity associated with expert-based weighting. It objectively assigns weights to indicators according to their relative importance, accommodates dimensional differences among indicators, and provides balanced evaluations. Consequently, the application of EWM ensures a fair, scientific, and reliable measurement of tourism-related economic resilience, allowing for robust comparative analysis and policy recommendations.

4.3. Analysis of Results

This section, based on the research framework established in earlier sections, describes the employment of the DID model and EWM for empirical analysis to examine the impact of GIAHS on regional tourism economies and assess their economic resilience. The model specification, variable selection, data sources, and their reliability have been discussed in detail in previous sections. This section begins by presenting the baseline regression results, followed by robustness checks to validate the reliability of the findings. Subsequently, based on the EWM, the tourism-related economic resilience levels of the case study sites are comprehensively evaluated, and the weights of various indicators and their specific impacts on resilience are discussed. Through this analysis, the section aims to provide systematic empirical support for the tourism-related economic resilience of GIAHS and uncover the relative significance of different factors in economic resilience.

4.3.1. Baseline Regression Results

Using the baseline model, this study conducted a regression analysis of the impact of GIAHS on regional tourism economies using Stata 15.1. The regression results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Baseline model regression results.

From the regression results in Table 4, it is evident that the coefficient of the variable is significantly positive in all models, indicating that after controlling for the year fixed effects, county fixed effects, and other control variables, the certification of agricultural heritage has a significant positive impact on regional tourism economic development. This result suggests that the protection of GIAHS not only enhances local tourism revenue but also boosts tourism reception capacity, further promoting the sustainable development of the tourism industry.

To ensure the robustness of the baseline regression results, two robustness checks were conducted in this study.

- Placebo Test

To verify whether the regression results were influenced by unobserved potential factors, a placebo test was conducted by randomizing the treatment and control groups. Specifically, while keeping the certification year of agricultural heritage unchanged, counties that were not certified were randomly selected to form a new treatment group for the regression analysis. If the regression results remained significant, it would indicate that the original conclusions were robust. The results of the placebo test are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Placebo test results.

From the results of the placebo test, it is evident that in the regression analysis between the randomized treatment and control groups, the coefficient of the variable was not significant, indicating that the fabricated treatment group did not have a significant effect on tourism economics. This result further validates the robustness of the original regression findings.

- Exclusion of Outlier Effects

To avoid potential adverse effects from outliers on the regression results, this study performed a winsorization procedure on the continuous variables. Specifically, the top and bottom 1%, 2%, and 5% of the data were winsorized, as shown in Table 6. The regression results indicate that the coefficients after winsorization were consistent with the baseline regression results, further confirming the positive impact of GIAHS on regional tourism economies.

Table 6.

Results after winsorizing variables at 1%, 2%, and 5%.

4.3.2. EWM Calculation Results

As demonstrated in the previous analysis, the DID model validated the positive impact of agricultural heritage on regional tourism economies. To further assess the level of tourism-related economic resilience, this study utilized the EWM to comprehensively evaluate the economic resilience of tourism. By calculating the weights of various dimensions, the EWM objectively reflects the relative importance of each indicator in the economic resilience assessment of tourism, providing scientific evidence for policymakers.

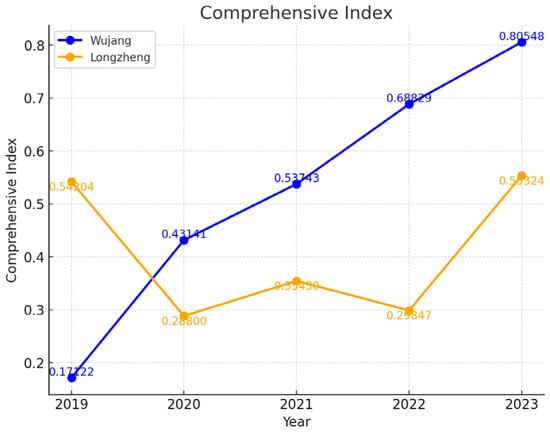

Based on the tourism-related economic resilience evaluation system constructed through the EWM (see Table 3 for details), this study evaluated panel data from Wujiang and Longsheng, spanning 2019 to 2023. As shown in Figure 5, Wujiang’s comprehensive resilience index exhibited a sustained upward trajectory, rising from 0.17 (2019) to 0.80 (2023), with an average annual growth rate of 37.6%, demonstrating a statistically significant positive evolutionary trend (p < 0.01). In contrast, Longsheng’s index displayed U-shaped fluctuations, declining from 0.54 (2019) to 0.30 (2022) before rebounding to 0.55 (2023), a pattern that is consistent with the evolutionary dynamics of resource-dependent systems [61].

Figure 5.

A comprehensive index of Wujiang and Longsheng heritage sites.

Using a DID model with regional fixed effects, we identified that, in Wujiang’s market-driven pathway, a 1% increase in cultural tourism integration led to a 0.67% growth in the resilience index (β = 0.672; SE = 0.18), confirming the causal effect of the “institution–market” synergy mechanism on resilience formation (path dependence test: φ = 0.82; p < 0.05).

- Wujiang Silk Culture System (Jiangsu)

As shown in Table 7, Wujiang’s tourism-related economic resilience has improved significantly. The levels of resilience in the supply, demand, structural, and management dimensions have all increased, with the most notable improvement occurring in 2023 when tourism-related economic resilience reached 0.80. This result indicates that Wujiang’s ability to recover from both internal and external shocks has been significantly enhanced, reflecting the region’s successful efforts in strengthening its tourism-related economic resilience.

Table 7.

Overview of tourism-related economic resilience levels in Wujiang.

- Longsheng Longji Rice Terraces System (Guangxi)

As shown in Table 8, Longsheng County’s tourism-related economic resilience demonstrates volatile changes. Between 2019 and 2023, the area’s tourism-related economic resilience first declined from 0.54 to 0.30 and then rebounded to 0.55. Both its supply and demand resilience experienced considerable fluctuations during this period, particularly demand resilience, which decreased significantly. This decline may be related to external economic factors and changes in market demand. The observed fluctuations reflect that Longsheng’s ability to recover and adapt to external shocks is influenced by various factors.

Table 8.

Overview of tourism-related economic resilience levels in Longsheng.

The calculation results from the EWM reveal significant differences in the weight distribution across the different dimensions between Wujiang and Longsheng. Wujiang’s weight distribution places more emphasis on core factors such as traditional villages and tourism consumption levels, reflecting the region’s focus on cultural heritage preservation and demand in the tourism market in its economic development based on tourism. In contrast, Longsheng places greater emphasis on green innovation patents and its structural adjustment capacity, highlighting the region’s strategic focus on responding to external shocks and promoting sustainable development. These differences reveal the priority areas and strategic choices that each region makes in developing tourism economies, reflecting the distinctive characteristics and challenges of local economic resilience.

As seen in Table 9 and Table 10, the weight analysis results provide profound theoretical support for the tourism-related economic resilience of agricultural heritage sites and offer critical insights for policymakers. These results help guide more informed and rational decisions in practical applications.

Table 9.

Weights of indicators for tourism-related economic resilience in Wujiang.

Table 10.

Weights of indicators for tourism-related economic resilience in Longsheng.

5. Discussion

This study reveals the promoting effect of agricultural heritage certification on regional tourism-related economic resilience through a comparative case analysis of two agricultural heritage sites: Wujiang and Longsheng. Utilizing the DID model and EWM, this research systematically elucidates the mechanisms by which AHSs influence tourism-related economic resilience and their spatial differentiation patterns. The findings underscore the importance of a coordinated mechanism for cultural heritage protection, tourism development, and ecological compensation to enhance the economic resilience of tourism.

Heritage tourism serves as an essential bridge that connects cultural resource protection with tourism development. Through AHS certification, it significantly drives the enhancement of resilience at heritage sites. The AHS certification amplifies brand effects and promotes institutional innovation, thereby strengthening these sites’ capacity to respond to external shocks. For instance, our empirical analysis of Wujiang’s “Silk Culture + Tourism” integration model demonstrated that the deep exploration of cultural resources combined with the development of the tourism industry yields significant marginal effects (β = 0.672; p < 0.05), indicating that synergy between culture and industry positively impacts resilience enhancement. This finding aligns with existing research that emphasizes cultural tourism integration as critical for enhancing economic sustainability [21,26].

However, while Wujiang’s policy framework adopts a tripartite design encompassing “protection–development–compensation”, establishing institutional path dependencies (φ = 0.82), it also faces potential risks of cultural commodification. Over-commercialization could potentially dilute cultural authenticity and weaken the sustainability of heritage tourism. Therefore, despite the short-term benefits observed, it is crucial to consider long-term strategic management measures to mitigate these potential risks. This includes fostering community participation and establishing clear guidelines for sustainable development to maintain cultural authenticity.

In comparison, Longsheng exhibits relatively weak resilience, primarily due to risks associated with “single-landscape lock-in”, where excessive dependence on singular natural or cultural resources results in insufficient adaptability to external changes. This situation is consistent with findings by Feng et al., who indicated that regions overly dependent on single-resource tourism are particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in market demands and environmental changes [62]. Longsheng’s resilience pattern confirms that infrastructure development and industrial diversification are essential for improving tourism resilience, especially in resource-dependent regions.

Furthermore, Wujiang’s success highlights the significant role of digital transformation and infrastructure development in boosting tourism resilience. Zhao similarly found that digital economy adoption significantly enhances economic resilience by improving service quality and visitor satisfaction [49]. In contrast, Longsheng’s lag in digital adoption clearly indicates potential pathways for policy intervention and future infrastructure improvements to bolster resilience.

Finally, the results underscore the importance of adopting a comprehensive governance framework—combining global standards and local practices—to sustainably enhance economic resilience. Wujiang’s established institutional innovations (such as heritage tourism funds) exemplify this approach, providing clear evidence that targeted policy interventions are crucial for long-term resilience sustainability. Longsheng, therefore, could adopt similar governance frameworks, including ecological compensation mechanisms and community-led tourism initiatives, to overcome the limitations of fragmented policy support [11].

This comparative study provides critical theoretical insights and practical implications for agricultural heritage sites globally. By comparing Wujiang and Longsheng, the study enriches resilience theory, especially its application in the context of heritage tourism, and suggests practical policy pathways tailored to local characteristics. These insights contribute to the ongoing discourse on sustainable heritage tourism and resilience enhancement, informing policymakers and stakeholders who seek to balance economic development and cultural preservation.

6. Conclusions and Contributions

6.1. Key Findings

This study, through an empirical analysis of two typical agricultural heritage sites—Wujiang and Longsheng—explores how agricultural heritage systems influence tourism-related economic resilience and proposes policy recommendations that are tailored to different development pathways. This research demonstrates that heritage conservation, industrial synergy, infrastructure development, digital transformation, and policy support collectively form the key elements for enhancing the economic resilience of tourism, providing both practical insights and theoretical guidance for the sustainable development of agricultural heritage sites.

- Agricultural Heritage Certification Promotes Tourism Growth

Agricultural heritage certification has significantly boosted tourism economies. Wujiang achieved an average annual tourism revenue growth of 12.5%, while Longsheng witnessed an 18.3% increase in visitor numbers. However, spatial disparities in economic resilience exist: Wujiang developed market-driven resilience, leveraging the economic hinterland of the Yangtze River Delta, with a tourism revenue volatility coefficient of only 0.15. In contrast, Longsheng exhibited resource-dependent vulnerability due to its reliance on natural assets, with a seasonal fluctuation coefficient as high as 0.48. These differences highlight the critical roles of the industrial structure and market environment in building tourism resilience.

- Industrial Synergy Strengthens Risk Resistance

Wujiang enhanced its economic stability by integrating cultural tourism with its silk industry, creating six derivative industrial chains. A 1% increase in industrial synergy improved tourism resilience by 0.67%. Comparatively, Longsheng’s limited industrial chain extension (42%) left its tourism economy more susceptible to market shocks. This underscores the importance of fostering deeper integration between agriculture and tourism to build stable, diversified economic structures.

- Infrastructure and Digitalization Underpin Resilience

The quality of infrastructure positively correlates with tourism resilience. Wujiang’s tourism facility density, 3.2 times that of Longsheng, ensured a stronger visitor capacity and stable growth. Additionally, Wujiang leveraged digital platforms and smart technologies (e.g., VR/AR) to enhance visitor experiences, while Longsheng lagged in infrastructure and digital adoption. Digital transformation not only optimizes services but also expands cultural outreach, boosting the competitiveness of heritage sites.

- Policy Frameworks Determine Resilience Sustainability

Wujiang established a robust “heritage conservation–tourism development–ecological compensation” policy system, achieving a policy intervention elasticity coefficient of 0.89. Longsheng’s weaker policy support, particularly in ecological compensation and infrastructure, hindered resilience. Effective governance requires balancing ecological preservation with economic development through targeted policy interventions.

6.2. Theoretical and Policy Contributions

6.2.1. Novelty and Theoretical Contributions

This research contributes to the existing body of knowledge on agricultural heritage, tourism development, and economic resilience in several distinct ways. Previous studies have primarily focused on the qualitative evaluations of agricultural heritage sites, emphasizing their cultural significance and ecological sustainability [21,61]. However, quantitative analyses systematically examining how heritage certification impacts economic resilience through tourism remain scarce, particularly concerning comparisons of distinctly different development contexts.

By employing a DID methodology combined with the EWM, this study provides robust empirical evidence addressing this theoretical gap. This approach not only quantifies the causal impacts of agricultural heritage certification but also reveals the distinct pathways through which resilience is enhanced—market-driven mechanisms in economically developed areas (Wujiang) versus resource-dependent vulnerability in less-developed areas (Longsheng). Thus, this study enriches the resilience theory by highlighting economic diversification and sustainable tourism as crucial theoretical lenses to interpret the resilience mechanisms within agricultural heritage tourism contexts.

Furthermore, this research introduces a novel “Four-Dimensional Optimization Matrix”, encompassing value activation, infrastructure upgrading, industrial symbiosis, and adaptive governance. This framework provides a structured conceptual model that advances our understanding of heritage tourism’s resilience dynamics, which is applicable to comparative analyses across diverse global contexts.

6.2.2. Policy Contributions

From a policy perspective, this study delivers actionable insights by clearly identifying critical factors that policymakers should target to enhance economic resilience in agricultural heritage regions. The results underscore the importance of balanced governance strategies—integrating cultural preservation with economic incentives—to avoid pitfalls such as cultural commodification or over-tourism, risks that previous studies have frequently highlighted [63,64].

Specifically, the differentiated resilience patterns identified in Wujiang and Longsheng provide tailored policy implications. For market-driven regions like Wujiang, policies should prioritize managing cultural authenticity and sustainable development through robust regulatory frameworks, community engagement, and digital innovation. In contrast, resource-dependent regions like Longsheng require infrastructural investments, diversification of tourism products, and capacity-building initiatives to strengthen their adaptability and reduce vulnerability to seasonal and market fluctuations. Thus, this comparative analysis provides precise policy recommendations that are relevant not only to Chinese contexts but which are also transferable to other global heritage sites facing similar developmental challenges.

6.2.3. Comparative Analysis: State-of-the-Art in China and Overseas

Research on agricultural heritage and its role in regional economic resilience has gained momentum globally, yet significant differences remain between Chinese and international approaches.

In China, agricultural heritage research has rapidly evolved, driven largely by governmental initiatives such as the GIAHS project launched by FAO and extensive rural revitalization policies. Recent domestic studies have increasingly adopted quantitative approaches to measure the economic impacts of heritage tourism, but comprehensive assessments of economic resilience using mixed methods remain limited [10,12]. Chinese scholarship tends to emphasize the practical outcomes that are aligned closely with policy goals, such as rural revitalization and poverty alleviation [7].

Overseas research, by contrast, often focuses on heritage conservation, sustainable tourism theories, and community-based governance models, highlighting the complex interactions between tourism, cultural commodification, and authenticity [21,65]. International studies frequently utilize qualitative methods, with growing attention to the application of digital technologies and community empowerment strategies as mechanisms for resilience enhancement [66,67].

This research bridges these methodological and theoretical divides by integrating quantitative rigor that is typical of recent Chinese studies with nuanced qualitative insights that are common in international literature. Consequently, this work not only advances domestic scholarship on agricultural heritage but also contributes to broader international discussions on heritage tourism resilience, offering a comparative framework that can guide sustainable development practices globally.

6.3. Policy Recommendations

Based on our findings, four core policy pathways are proposed to enhance tourism resilience in agricultural heritage regions:

- From “Resource Dependency” to “Industrial Integration”: Economic Diversification

Wujiang’s silk-based industrial chain demonstrates resilience, while Longsheng’s reliance on single agricultural resources exposes it to market risks. We recommend promoting heritage integration with local industries (e.g., “heritage + education” models) and establishing “tourism + manufacturing” synergies to strengthen the robustness of industrial chains.

- From “Infrastructure Gaps” to “Smart Governance”: Service Optimization

Wujiang’s advanced infrastructure and smart tourism systems (e.g., digital guides) boosted its competitiveness, whereas Longsheng’s infrastructure deficits limited its growth. We recommend prioritizing low-carbon, eco-friendly infrastructure in remote areas and adopting smart tourism technologies (e.g., AI-driven management systems) to enhance service quality and recovery capacity.

- From “Fragmented Support” to “Systemic Governance”: Policy Innovation

Wujiang’s institutional innovations (e.g., heritage tourism funds) outperformed Longsheng’s fragmented policies. We recommend establishing a “Cultural Heritage Tourism Fund” to prioritize community-led projects and implementing a “resilience evaluation and compensation mechanism”, allocating 5–10% of the tourism revenue to heritage protection to prevent overdevelopment.

- From “Localized Development” to “Global Outreach”: International Competitiveness

While Wujiang elevated its global profile through silk culture promotion, Longsheng’s international visibility remains limited. We recommend strengthening cross-border collaborations (e.g., transnational heritage alliances) and deploying multilingual smart guides and personalized experiences to attract tourists from around the world.

6.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations, including potential biases due to the limited qualitative interview samples, constraints related to the availability of longitudinal data, and a relatively short analysis period, which might affect the generalizability of the findings.

6.5. Future Directions

This study proposes a “Four-Dimensional Optimization Matrix” (value activation–infrastructure enhancement–industrial synergy–governance innovation) to guide tourism resilience in developing countries. This framework applies to other heritage sites, particularly those undergoing economic transitions. Future research should refine the resilience metrics (e.g., visitor loyalty and brand influence), conduct case studies across diverse ecological and economic contexts, and employ causal inference methods (e.g., regression discontinuity) to assess the long-term policy impacts. Such efforts will advance the sustainable development and global competitiveness of agricultural heritage systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and M.W.; methodology, M.L. and M.W.; software, M.W.; validation, Y.L. and M.W.; investigation, W.S., J.Y. (Junhao Yin) and J.Y. (Jia You); resources, G.Z.; data curation, M.W. and W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L. and M.W.; writing—review and editing, M.L. and W.S.; visualization, M.W. and M.L.; supervision, Y.L. and G.Z.; project administration, Y.L. and G.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21&ZD225), “Study on the Ecological Environment Changes and Characteristic Agricultural Development in the Yangtze River Delta Region since the Ming and Qing Dynasties”.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the colleagues and institutions that contributed to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems. Available online: https://www.fao.org/giahs/en (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Zhang, W.Y.; Tang, S. The Concept and Value Judgment of Agricultural Cultural Heritage. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2008, 36, 11041–11042. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.X.; Chen, G.S. Basic Characteristics, Tourism Value, and Logical Structure of Agricultural Cultural Heritage. Hunan Soc. Sci. 2024, 03, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. Clarifying Heritage Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 1047–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Heritage Tourism: A Question of Definition. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L. Agricultural Cultural Heritage Protection and Key Issues to Be Addressed. Agric. Archaeol. 2006, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, S.M. Agricultural Cultural Heritage Studies; Nanjing University Press: Nanjing, China, 2015; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.M. The Connotation of Agricultural Cultural Heritage and the Eight Key Relationships to Focus on in Its Protection. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 33, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.H. Continuously Strengthening the Brand Effect of Agricultural Cultural Heritage Sites. China Agric. Resour. Zoning 2023, 44, 176+185. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.R.; Shi, J.Z.; Xu, H.C. Research on the Driving Mechanism of Agricultural Cultural Heritage Tourism on Rural Revitalization. Arid Zone Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Qie, H.K.; Lu, Y. Supply-side Reform of Agricultural Cultural Heritage: Contradiction Representation, Cause Analysis, and Strategy Choice. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 40, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.X.; Yao, C.C.; Sun, Y.H. Research on the Coupled and Coordinated Relationship Between Tourism Disturbance and Community Resilience in Agricultural Cultural Heritage Sites: A Case Study of the Hani Rice Terraces in Yunnan. Tour. Trib. 2023, 38, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.H.; Wu, W.J.; Song, Y.X. Research on the Coupling Relationship Between Agricultural Cultural Heritage Tourism and Rural Revitalization. Northwest Ethn. Stud. 2022, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Q.W. Priority Areas, Issues, and Strategies for Research on Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems and Their Conservation. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2020, 28, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, S.M. Agricultural Cultural Heritage: What to Protect and How. Agric. Hist. China 2012, 31, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J.X. Reflections on Strengthening the Protection and Management of World Cultural Heritage (Part I). Beijing Plan. Rev. 2005, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, R.; Yang, Q. Heritage Tourism and the Construction of a Shared Spiritual Homeland for the Chinese Nation. J. South-Cent. Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2024, 44, 87–94+184–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.L.; Huang, S.H.; Duan, L. A Review of the Evaluation of Cultural and Tourism Integration Development. Explor. Econ. Issues 2024, 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.F.; Tang, E.Y. Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism and the Strengthening of Chinese National Community Consciousness. Cult. Herit. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N. Social Benefits of Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Development—Based on Traditional Handicraft Intangible Heritage. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 46, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism: A Review of Recent Research and Trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Song, Y.X. Sustainable Tourism Development from the Perspective of Resilience. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.M.; Li, K.C. Research Progress and Practice of Resilient Cities from the Perspective of Foreign Public Administration. Chin. Public Adm. 2017, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, P. Spatiotemporal Differentiation and Influencing Factors of China’s Agricultural Development Resilience. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2019, 35, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B.W.; Liu, Z. Problems and Breakthroughs in the High-quality Development of Tourism Public Services. Tour. Trib. 2024, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.C.; Liu, Y.R.; Wan, Z.W.; Liang, W.Q. Evaluation and Influence Paths of Integrated Cultural-Tourism Development in Traditional Villages. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 980–996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; He, H.H.; Yang, Y. Research on Coupling Coordinated Development of Agricultural Cultural Heritage and Rural Tourism Industry: Taking 13 Places in Southwest China as Examples. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2021, 37, 891–896. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Q.W. Agricultural Heritage Tourism: A Brand New Field. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.C.; Zheng, Q.Q.; Wang, X.D.; Zou, Z.S. Exploration of the Green Development Model of Traditional Village Tourism Based on the “Two Mountains” Theory. Arid Zone Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.Q.; Hu, S.G.; Yang, R.; Tao, W.; Li, H.B.; Li, B.H.; Liu, P.L.; Wei, F.Q.; Guo, W.; Tang, C.C.; et al. Conservation and Utilization of Chinese Traditional Villages for Rural Revitalization: Challenges and Prospects. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1735–1759. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, G.Y.; Deng, M.M.; Ma, Y.M.; Lai, Y.T. Influencing Factors of Coupled Development Between Jasmine Tea Culture System and Tourism Industry in Fuzhou. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2022, 38, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.Z.; Li, Y.X. Digital Cultural Heritage Transmission Under Digital Culture Strategy: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Paths. Arch. Sci. Study 2024, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Nie, C.F.; Zhang, D. Measurement and Analysis of Economic Resilience of Chinese Urban Agglomerations—Shift-Share Decomposition Approach. Shanghai J. Econ. 2020, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, X.D. Spatiotemporal Evaluation of Urban Resilience Under Sustainable Development Concept. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.G.; Zhang, P.Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.X. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Influencing Factors of Economic Resilience in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2022, 42, 557–567. [Google Scholar]

- Qie, H.K.; Wu, J.L.; Lu, Y. Mechanism of Residents’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior in Agricultural Cultural Heritage Tourism Destinations. Econ. Probl. 2024, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.Y. Urban Disaster Resilience and Assessment from the Perspective of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, J.S.; Duan, Y.S.; Wang, Y.T.; Guo, Z.H.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.N. Semantic Analysis and Application of the Concept of “Resilience”. World Earthq. Eng. 2023, 39, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. Evaluation and Influencing Factors of Tourism Economic Resilience of Coastal Cities in the Bohai Rim Region. Master’s Thesis, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.K.; Chen, Y.Q.; Shi, B.; Xu, T. Evaluation Model of Urban Resilience under Rainstorm Flood Disaster Scenario. China Saf. Sci. J. 2018, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Lin, Y.Z.; Gu, C.L. Evaluation and Optimization Strategies of Urban Network Structural Resilience in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 1193–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.J.; Mao, Z.R.; Chen, X.K.; Yi, C. Measurement and Optimization of Rural Settlement Resilience in Yuanyang Hani Terraced Heritage Villages—A Case Study of Duoyishu Village. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 220–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Min, Q.W.; Xu, M.; Li, X.D. Evaluation of Integration among Three Industries in Agricultural Heritage Sites—A Case Study of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces System, Yunnan. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.M.; Zou, H.X.; Yi, Q.Q.; Zhou, Q. Evaluation of Tourism Resource Potential of Terraced Agricultural Heritage. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.C.; Yao, S.M. Evaluation of Prefecture-Level City Resilience in the Yangtze River Delta from a Social-Ecological System Perspective. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio, L.; Cordina, G.; Farrugia, N.; Vella, S. Conceptualizing and Measuring Economic Resilience. In Building the Economic Resilience of Small States; Islands and Small States Institute, University of Malta: Msida, Malta; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2006; pp. 265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Tang, Y.Q.; Han, Z.L.; Wang, Y.X. Resilience Measurement and Influencing Factors of Marine Ship Industry Chains in China’s Coastal Provinces. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.X.; Xu, M.F.; Sun, M. Research on the Evaluation and Improvement of Air Logistics Resilience in China during the Post-Pandemic Era. Price Theory Pract. 2021, 152–155+95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Xu, X.W. The Impact and Mechanism of Digital Economy on Agricultural Economic Resilience. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 22, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Theory of Tourism Economy; Tourism Education Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Y.C.; Li, Q.; Xu, L.L. Enactment of Tourism Law, Supply Level, and Development of Tourism Economy. Tour. Sci. 2023, 37, 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R.M. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C. Difference-in-Differences with Multiple Time Periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Bacon, A. Difference-in-Differences with Variation in Treatment Timing. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.M.; Zhao, R.J. Have National High-Tech Zones Promoted Regional Economic Development? Evidence Based on Difference-in-Differences Method. Manag. World 2015, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wu, H.J. Current Situation and Potential Problems of Difference-in-Differences Research in China. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2015, 32, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, M.R.; Xu, Y.M. Construction and Empirical Study of Evaluation Index System for Rural Revitalization. Manag. World 2018, 34, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.H.; Sun, J.N.; Ren, G.P. Entropy Weighting Method of Fuzzy Evaluation Factors and Its Application in Water Quality Assessment. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2005, 552–556. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.X.; Tian, D.Z.; Yan, F. Effectiveness of Entropy Weight Method in Decision-Making. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 3564835. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, M.M.; Patra, K.C.; Swain, J.B.; Khatua, K.K. Evaluation of Water Quality with Application of Bayes’ Rule and Entropy Weight Method. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 730–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems; International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis: Laxenburg, Austria, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Yotsumoto, Y.; Vafadari, K. Comparing Cultural World Heritage Sites and Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems and Their Potential for Tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 16, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Q.W.; Sun, Y.H. Concept, Characteristics, and Conservation Requirements of Agricultural Cultural Heritage. Resour. Sci. 2009, 31, 914–918. [Google Scholar]

- Mosler, S. Aspects of Archaeological Heritage in the Cultural Landscapes of Western Anatolia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa, M. Landscape Change in the Terraces of Ollantaytambo, Peru: An Emergent Mountain Landscape between the Urban, Rural and Protected Area. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, K.L.; Gonzalvo, C.M.; Aala, W.F., Jr. Leveraging Japanese Sado Island Farmers’ GIAHS Inclusivity by Understanding Their Perceived Involvement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, N.T.; Ghotbabadi, S.S.; Altafi, M. Agricultural Heritage as a Creative Tourism Attraction. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).