Analysis of Strategic Green Infrastructure Planning Guided by Actors’ Perceptions: Insights at the Regional Level in the Netherlands and Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What role do stakeholders play in the strategic planning process in practice, and how does their interaction, influenced by context-specificity, affect decision-making and the final result?

- What are the key factors or conditions that promote effective participation of stakeholders in developing successful strategies and ensuring their implementation?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria for Strategic Planning Case Studies

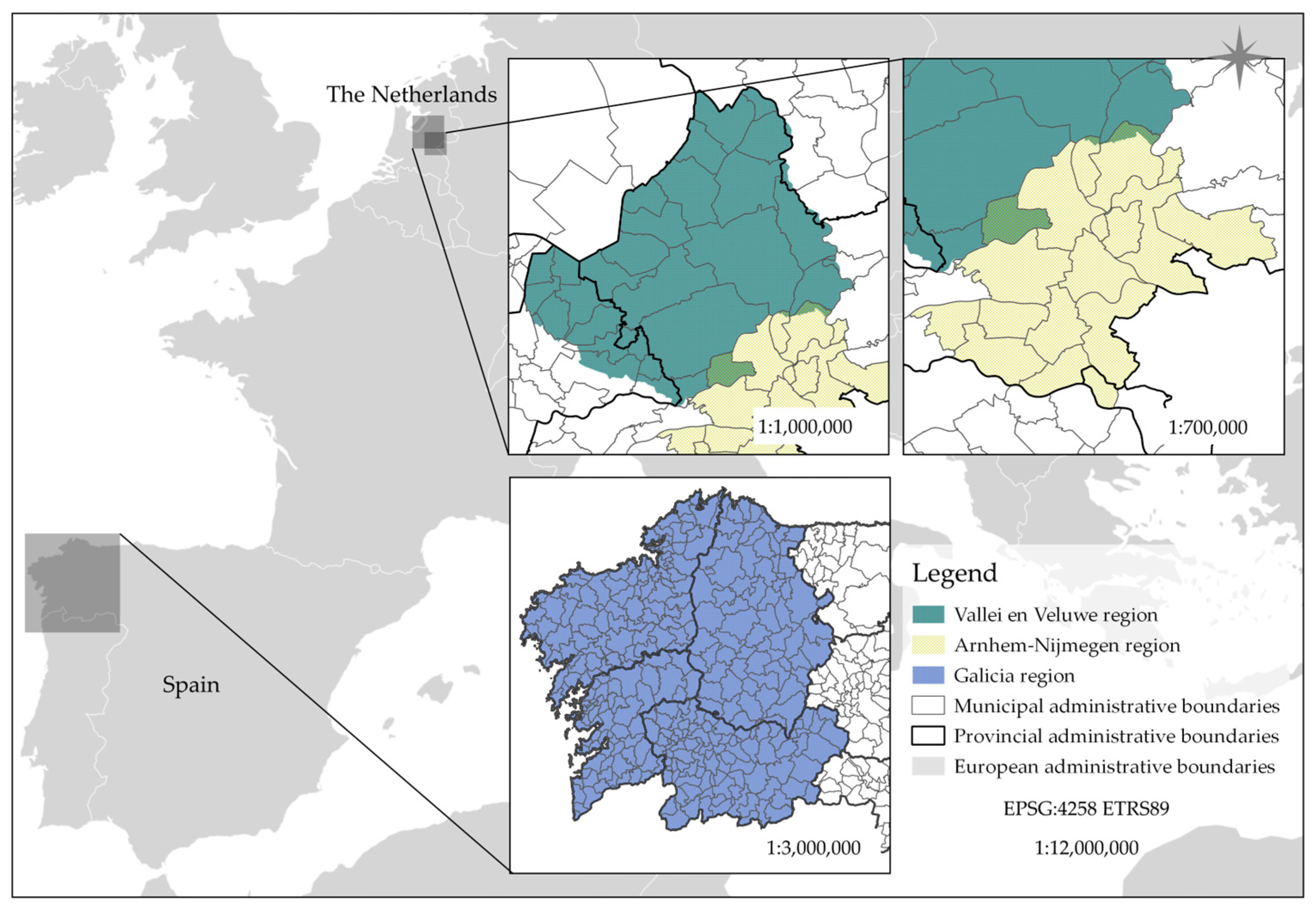

2.2. Case Studies Selected

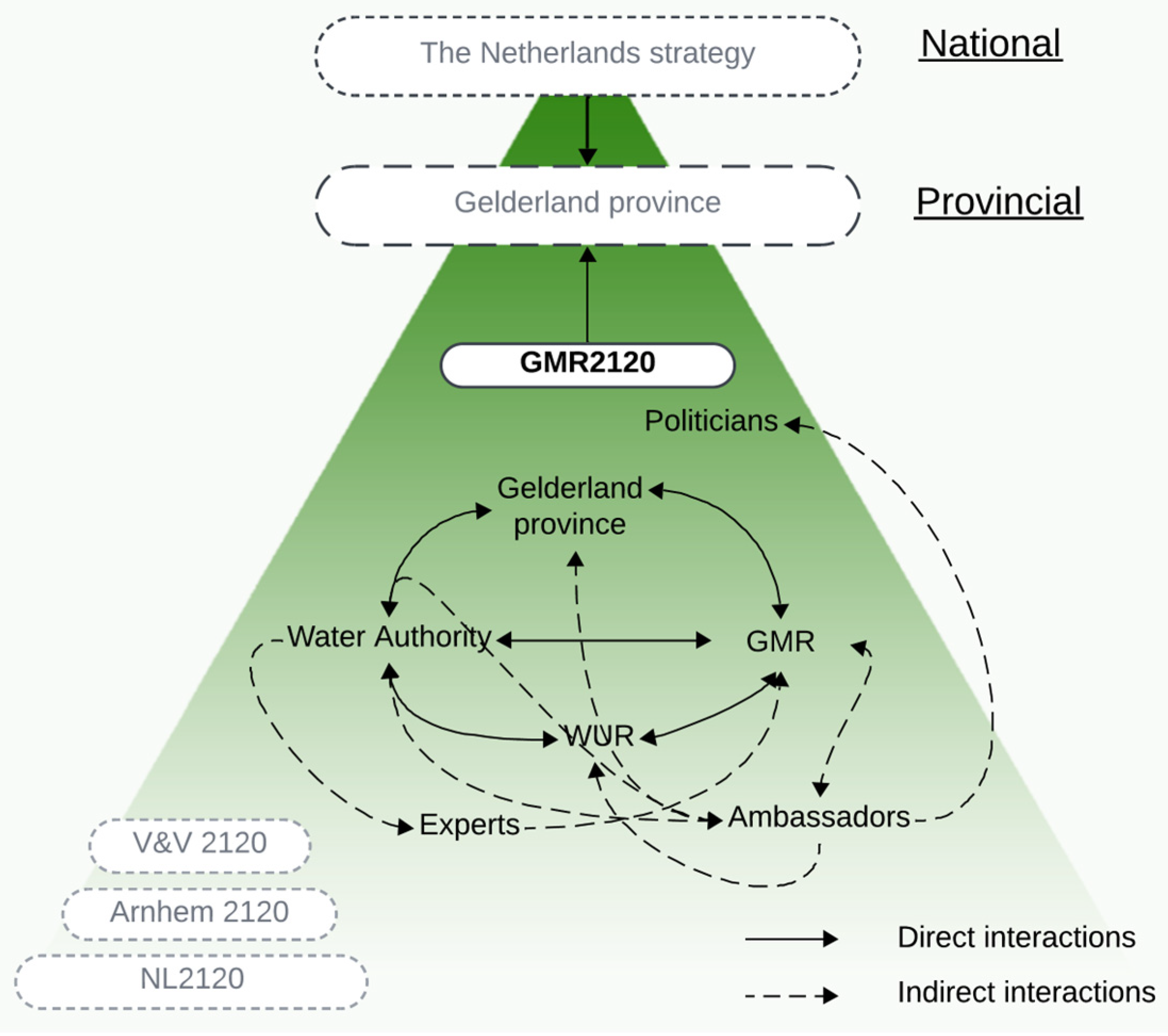

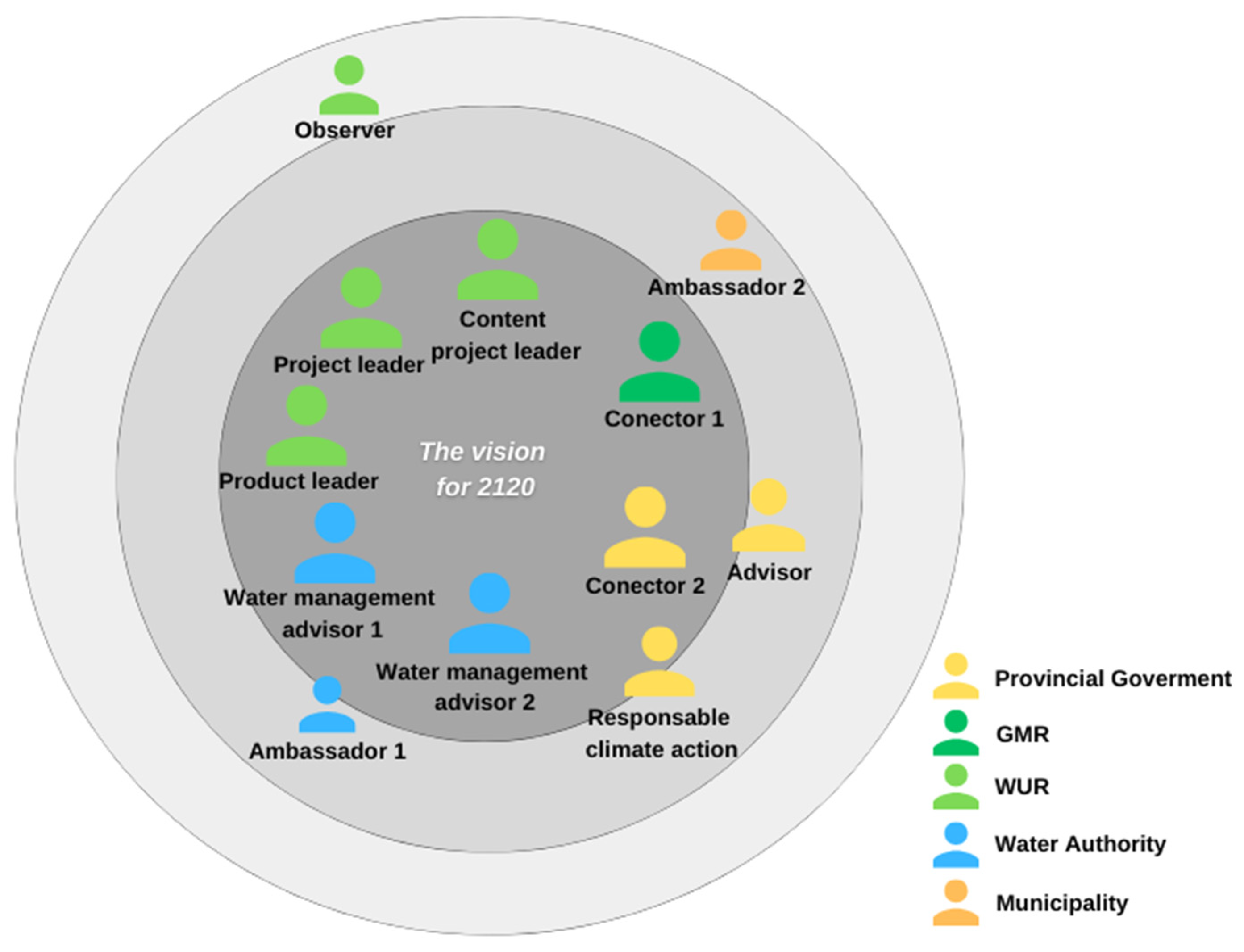

2.2.1. The Vision for 2120

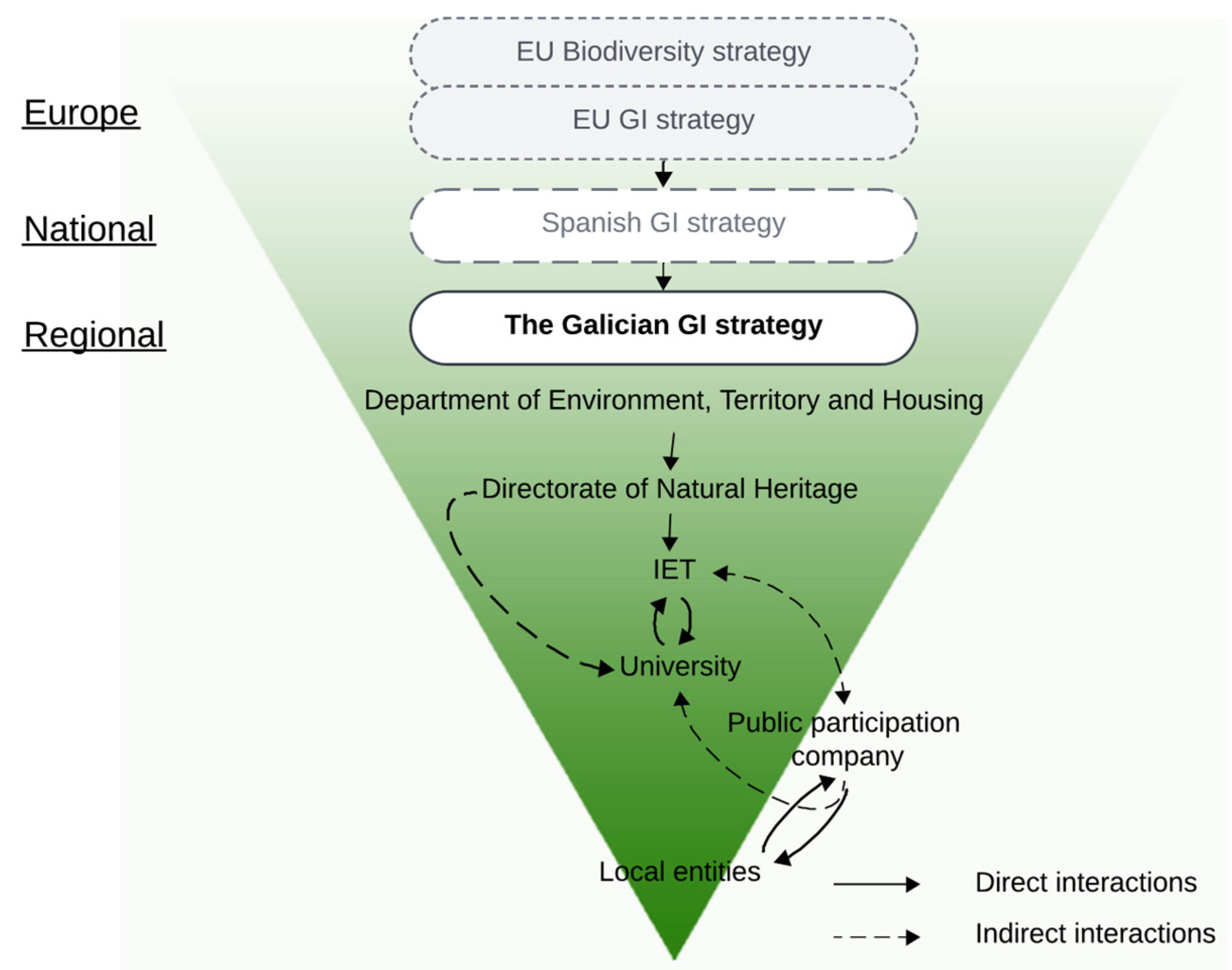

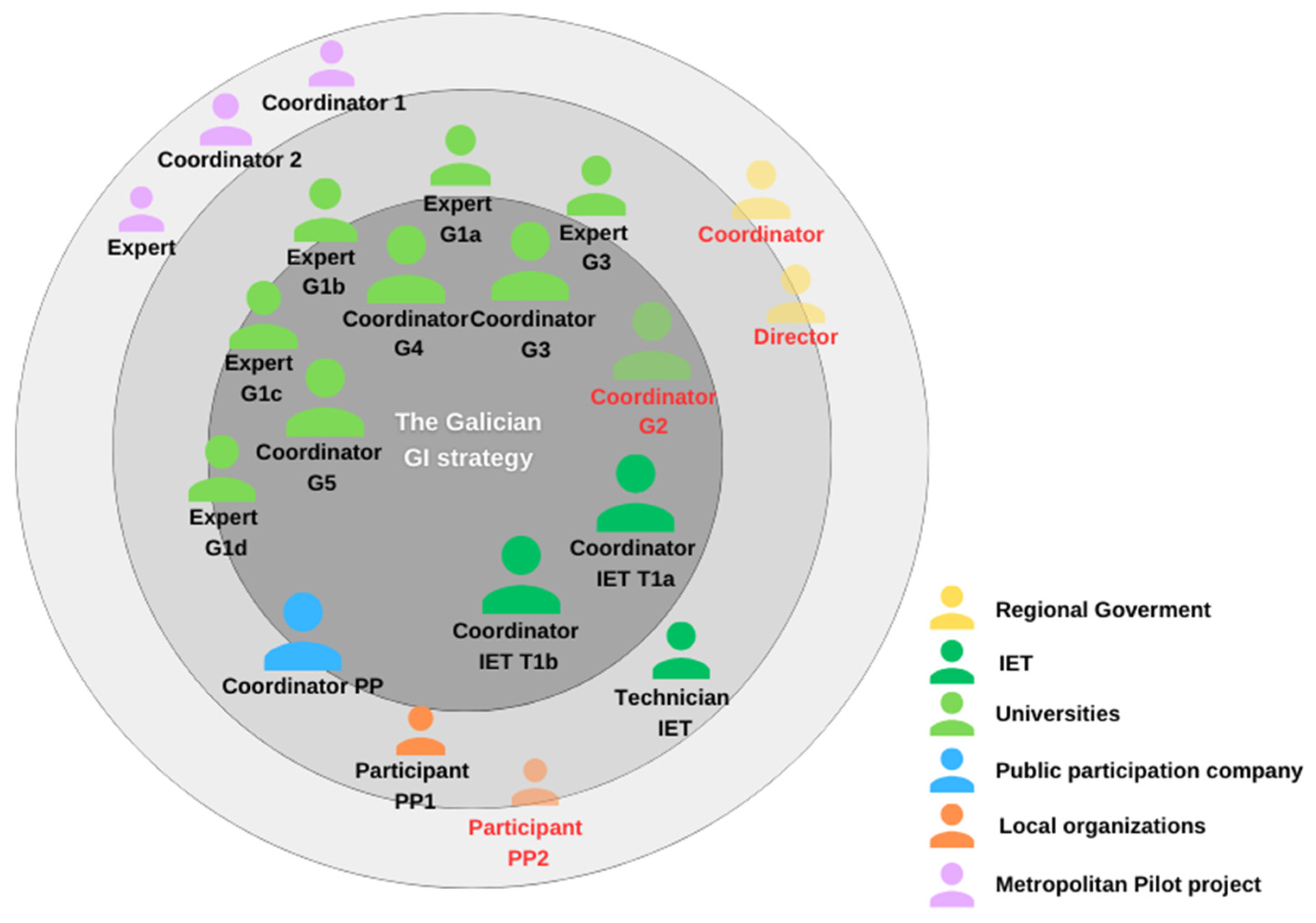

2.2.2. The Galician GI Strategy

2.3. Data Gathering for Qualitative Analysis

- ▪

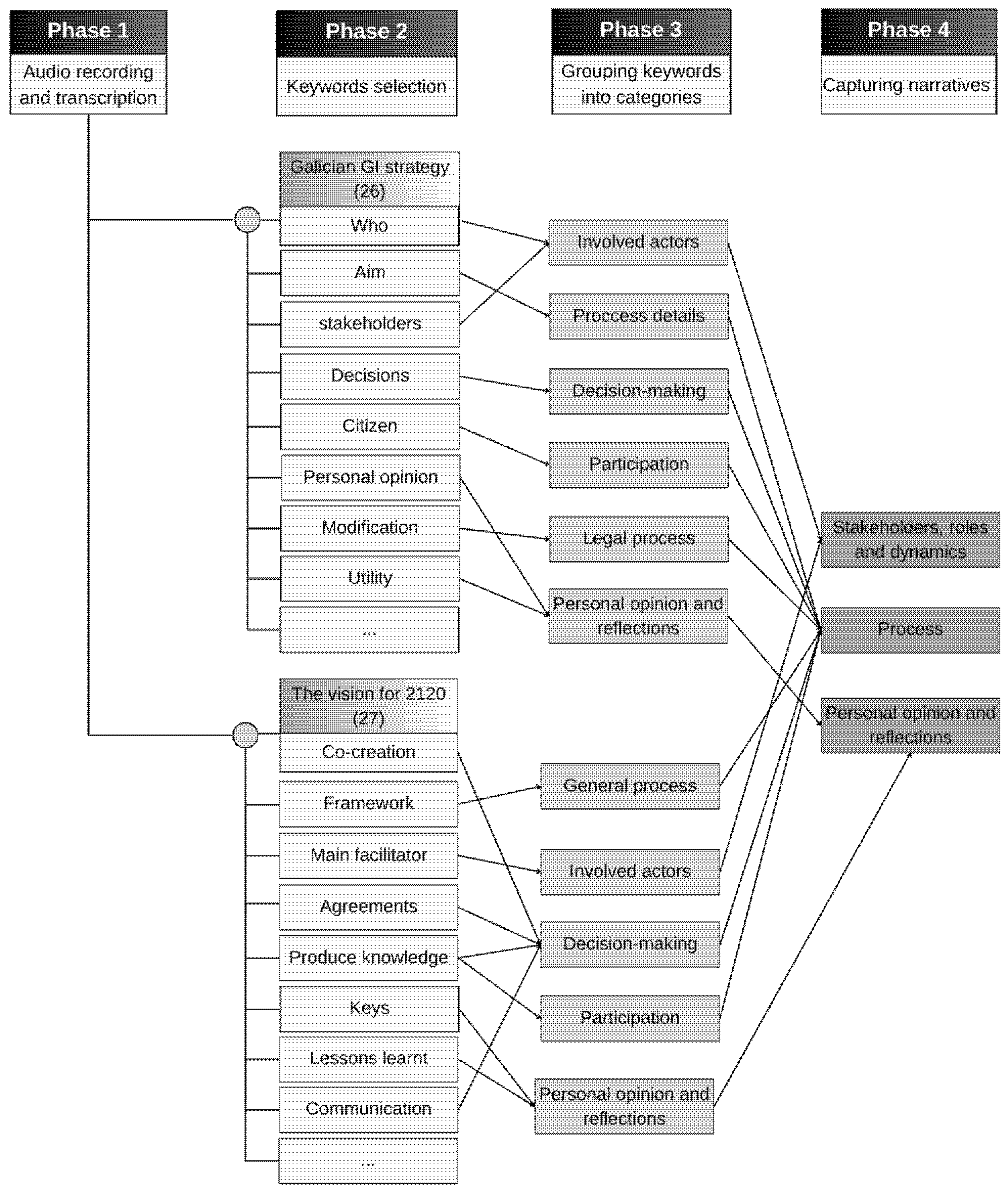

- Phase 1: Audio recording and transcription: Due to the large number of audio recording hours, an AI-based transcription model called Whisper version 20240930 [40] was initially used, followed by a review of the transcripts to enhance their accuracy.

- ▪

- Phase 2: Data was then organized and prepared for data categorization by inductively selecting key terms from the transcripts (26 for the Galician GI strategy and 27 for the Vision for 2120)

- ▪

- Phase 3: These keywords were grouped into categories based on their semantic similarities. For instance, keywords related to process details (e.g., start, framework, aim) were grouped together while terms related to decision-making (e.g., produce knowledge, communication, agreements) formed separate categories. The categories were reviewed and compared between interviews and across two projects to ensure they reflected similar concepts and maintained consistency in the analysis.

- ▪

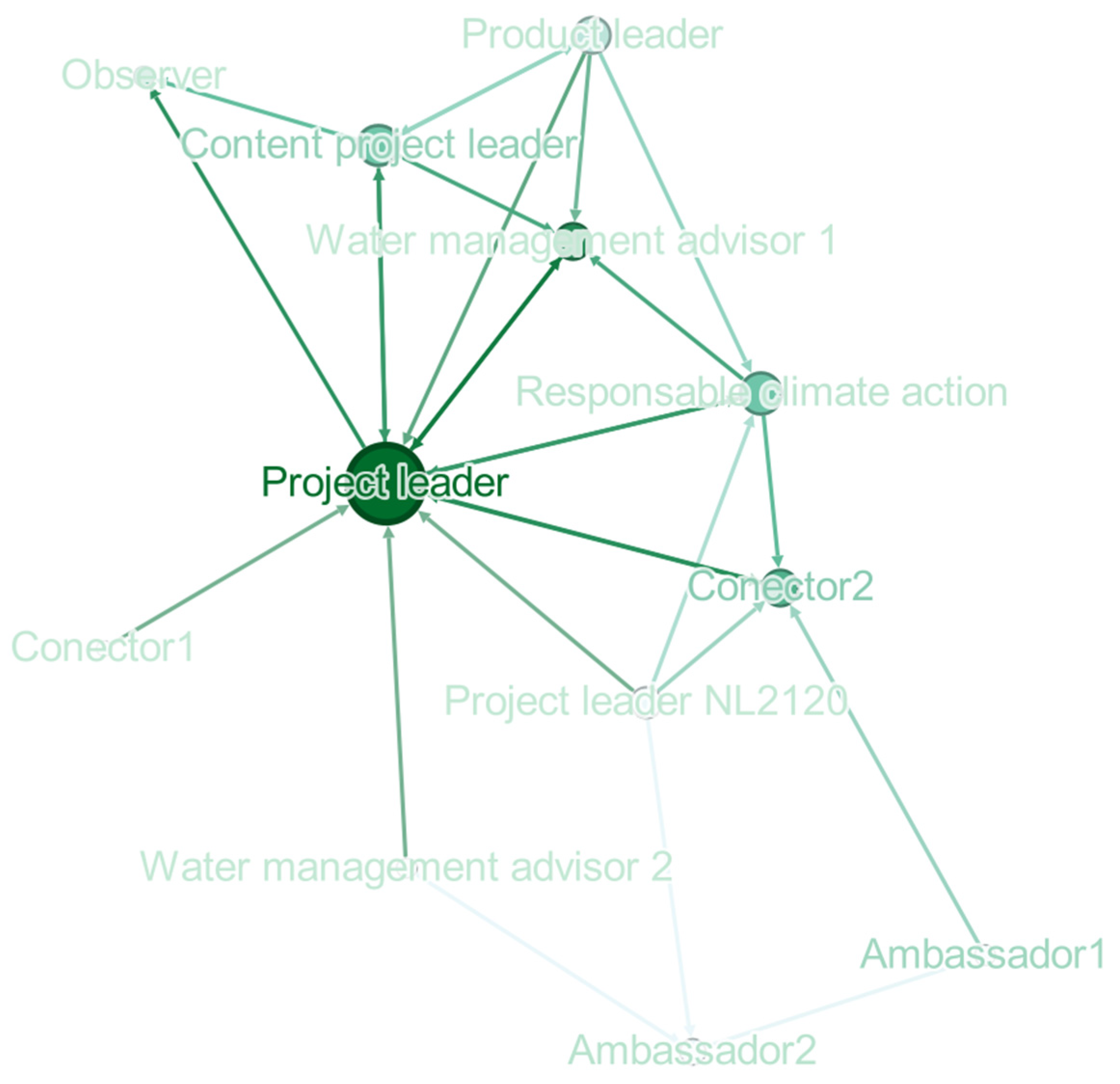

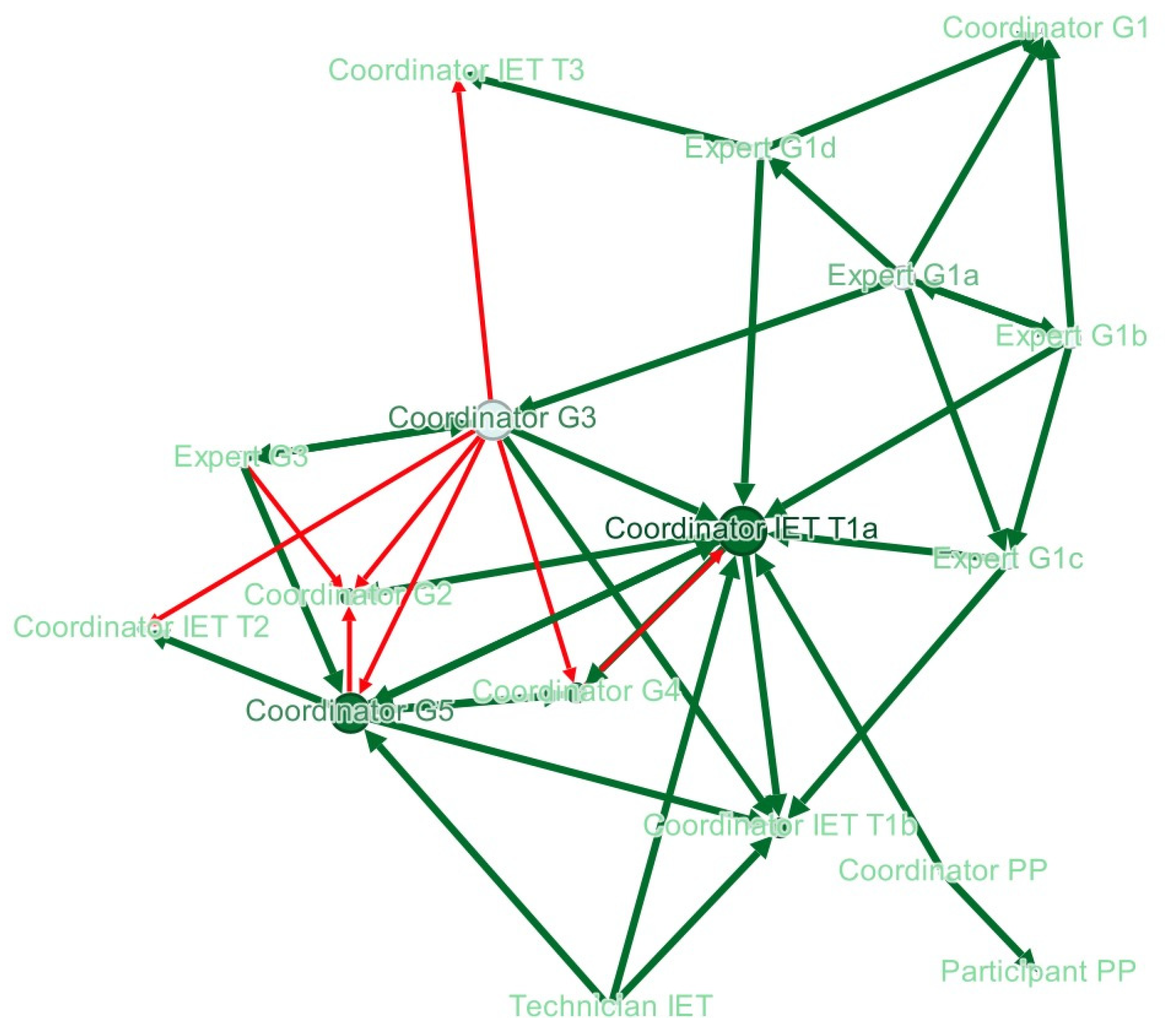

- Phase 4: The primary goal was to describe how the actors interacted during the process using their opinions and perspectives to create a joint narrative that reflects the reality across the different stages and aspects of the process. Therefore, the categories helped condense the information into three main groups or themes, which capture the narratives and contribute to building the Results section of the document while addressing the research questions posed. Additionally, the interconnections between actors in each case study were graphically represented by a basic social network analysis (SNA) (see [41,42]). SNA enables visualization of networks as graphs, in which elements are depicted as nodes (or vertices) and relationships as links (or edges) [43]. In this study, each actor was represented as a node, and any mention of another actor was recorded as a link in the network. As actors could be mentioned by others without reciprocating, the network was modeled as directed, so that links could be unidirectional or bidirectional. Moreover, the degree of connectedness of each node (i.e., the number of connections with other actors) was calculated to estimate each actor’s centrality, distinguishing between in-degree (number of incoming citations) and out-degree (number of outgoing citations). Special attention was given to the sentiments expressed, identifying and distinguishing links where references to other actors were of a negative nature. In addition, other centrality metrics, such as betweenness and eigenvector centrality, were also calculated. Betweenness centrality measures the extent to which an actor connects different segments of the network. Eigenvector centrality estimates the level of connection an actor has with other highly connected actors (i.e., those with higher degrees). For a more comprehensive explanation of centrality and its measures, see [41,43]. All network visualizations and metric calculations were performed using Gephi software, version 0.10 [44].

3. Results

3.1. The Vision for 2120 Process

3.1.1. Setting the Scene for the Vision for 2120

3.1.2. Behind the Scenes of the Vision for 2120

3.2. The Galician GI Strategy Process

3.2.1. Setting the Scene for the Galician GI Strategy

3.2.2. Behind the Scenes of the Galician GI Strategy

4. Discussion

4.1. What Role Do Stakeholders Play in the Strategic Planning Process in Practice, and How Does Their Interaction, Influenced by Context-Specificity, Affect Decision-Making and the Final Result?

4.2. What Are the Key Factors or Conditions That Promote Effective Participation of Stakeholders in Developing Successful Strategies and Ensuring Their Implementation?

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- Promote trustBuilding trust and respect among involved actors is essential for effective collaboration, better engagement, and increased willingness to participate. This requires the creation of safe spaces for interaction, transparency in information sharing, and activities that strengthen interpersonal and inter-institutional relationships, such as trust-building initiatives.

- (b)

- Foster continuous communicationContinuous communication is crucial for improving knowledge exchange and fostering cooperation among stakeholders at all levels. Medium-term presentations, workshops, and dissemination activities throughout the process can contribute to this goal.

- (c)

- Encourage active participation and commitment of stakeholdersTo ensure enthusiasm, partnership, and commitment, it is recommended to establish mechanisms for participation that guarantee real commitment and joint decision-making, such as the use of narrative storylines. Specifically, co-constructed GI narratives that are easily perceived by participants as leading to improvements in their immediate environment and having intergenerational consequences may help secure the engagement of a diverse range of actors.

- (d)

- Enhance collaborative learningIt is essential to make the participation process inclusive in order to create procedural equity and effective results. This helps to foster collaboration and co-creation processes, such as creating networks of individuals, which may be particularly important for concepts like GI that often start without a concrete and shared vision.

- (e)

- Strengthen leadership and coordinationBeing still a novel concept with numerous linkages to different administrative bodies, GI may challenge existing institutional and governance frameworks. Strong and effective leadership should be promoted to coordinate and mobilize stakeholders in a collaborative decision-making process. Additionally, governance structures should be designed to enable efficient coordination between different levels and actors. This fosters creative solutions and strong guidance necessary for navigating complex situations. It is required to set roles from the outset.

- (f)

- Develop a flexible, inclusive, and adaptable decision-making frameworkGiven that conditions and contexts change rapidly, especially for a GI supporting climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, a flexible and adaptable decision-making framework that encourages fruitful debate, creative thinking, and sustainable solutions. It should enable the resolution of complex problems that take into account diverse perspectives and experiences.

- (g)

- Foster the shift towards more flexible and collaborative institutional modelsTo address current challenges, supporting a shift toward more adaptable and collaborative institutional models is critical. This involves reviewing and adjusting existing legal and organizational frameworks to ensure they can accommodate changing realities and foster greater cooperation among stakeholders. This includes fostering collaborative learning at all levels and promoting more participatory and inclusive processes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GI | Green Infrastructure |

| NL2120 | A nature-based future for the Netherlands in 2120 |

| V&V2120 | Vallei en Veluwe vision 2120 |

| GMR2120 | Groene Metropool Regio vision 2120 |

| GMR | Arnhem–Nijmegen Green Metropolitan Region |

| WUR | Wageningen University and Research |

| UDC | University of A Coruña |

| USC | University of Santiago de Compostela |

| IET | Institute of Territorial Studies |

| GT | Grounded Theory |

| SNA | Social Network Analysis |

| TKI | Top Consortia for Knowledge and Innovation |

Appendix A. Interview Questions

| Role |

| What is your role in the project? And the role of your institution? |

| The process |

| Why did it arise, and with what purpose? Who motivated it, and for whom? How was the process? Who is the facilitating agent? How or who made the decisions? Level of formality/instrumentalization of the project Level of integration in the context of planning Level of co-creation and co-creation activities. Lessons Learned from the processes. The easiest and most difficult part of the process or in each of the phases |

| Participation |

| When does the participatory process occur within the overall project? What instruments of participation have been used? Who dialogues and establishes agreements and how? What criteria were established for selecting individuals/groups involved in processes? What criteria tools/methodologies were used to facilitate the exchange of information among participants? (e.g., working sessions, duration, presence or absence of a facilitator, how participants were informed, how their opinions were shared and collected). What techniques were used to generate the necessary knowledge in the process? What types of stakeholders were involved, and what role did they play? How has the stakeholder engagement process been? Activities of engagement carried out through co-creation process. Which actors involved in the process do you consider to be the most relevant and which decisions were influenced by? What are the key difficulties and opportunities that raised from stakeholder engagement? What are the keys factors for the success of a project like this? What types of problems were encountered during the process? |

| Implementation process |

| What happens after the main process? How will it be implemented, and under what legislation or planning instrument…? |

References

- Monteiro, R.; Ferreira, J.; Antunes, P. Green Infrastructure Planning Principles: An Integrated Literature Review. Land 2020, 9, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzas, M.; Hermoso, V.; de-Miguel, S.; Bota, G.; Brotons, L. Designing a network of green infrastructure to enhance the conservation value of protected areas and maintain ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallecillo, S.; Polce, C.; Barbosa, A.; Perpiña Castillo, C.; Vandecasteele, I.; Rusch, G.M.; Maes, J. Spatial alternatives for Green Infrastructure planning across the EU: An ecosystem service perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 174, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, V.; Morán-Ordóñez, A.; Lanzas, M.; Brotons, L. Designing a network of green infrastructure for the EU. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 196, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.M.C.; Wheeler, E. Ecosystems as infrastructure. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 15, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, S.; Arcidiacono, A.; Pogliani, L. Integrating green infrastructure into spatial planning regulations to improve the performance of urban ecosystems. Insights from an Italian case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Building a Green Infrastructure for Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication of the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Our Life Insurance, Our Natural Capital: An EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020; COM(2011) 244 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi Koc, C.; Osmond, P.; Peters, A. Towards a comprehensive green infrastructure typology: A systematic review of approaches, methods and typologies. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsler, A.M.; Meerow, S.; Mell, I.C.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A. A “green” chameleon: Exploring the many disciplinary definitions, goals, and forms of “green infrastructure”. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S. The politics of multifunctional green infrastructure planning in New York City. Cities 2020, 100, 102621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo-Muñiz, A. Advances in Strategic Planning of the Public Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean: Balance and Perspectives. Qual. Issues Insights 21st Century 2013, 2, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós Dasí, J.; Olcina Cantos, J.; Rico Amorós, A.; Rodríguez Navarro, C.; del Romero Renau, L.; Espejo Marín, C.; Vera Rebollo, J.F. Planes Estratégicos Territoriales De Carácter Supramunicipal. Bol. Asoc. Geógrafos Esp. 2005, 39, 117–149. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós Dasí, J. Capítulo 5. Gobernanza para una renovada planificación territorial estraté gica; hacia la innovación socio-territorial. In Planificación Estratégica Territorial: Estudios Metodológicos; Junta de Andalucía, Dirección General de Administración Local: Sevilla, España, 2010; pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, M.; Scott, M.; Collier, M.; Foley, K. Developing green infrastructure ‘thinking’: Devising and applying an interactive group-based methodology for practitioners. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 843–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bally, F.; Coletti, M. Civil society involvement in the governance of green infrastructure: An analysis of policy recommendations from EU-funded projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, M.; Scott, M. Delivering ecosystems services via spatial planning: Reviewing the possibilities and implications of a green infrastructure approach. Town Plan. Rev. 2014, 85, 563–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, A.; Guillén, L.A.; Brukas, V. Regional forest green infrastructure planning and collaborative governance: A case study from southern Sweden. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 160, 103840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissonnette, J.-F.; Dupras, J.; Messier, C.; Lechowicz, M.; Dagenais, D.; Paquette, A.; Jaeger, J.A.G.; Gonzalez, A. Moving forward in implementing green infrastructures: Stakeholder perceptions of opportunities and obstacles in a major North American metropolitan area. Cities 2018, 81, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Lafortezza, R. Urban green infrastructure in Europe: Is greenspace planning and policy compliant? Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Davies, C.; Sanesi, G.; Konijnendijk, C. Green Infrastructure as a tool to support spatial planning in European urban regions. iForest 2013, 6, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I.; Allin, S.; Reimer, M.; Wilker, J. Strategic green infrastructure planning in Germany and the UK: A transnational evaluation of the evolution of urban greening policy and practice. Int. Plan. Stud. 2017, 22, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.C.; Monteiro, R.; Silva, V.R. Planning a Green Infrastructure Network from Theory to Practice: The Case Study of Setúbal, Portugal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bally, F.; Daudigeos, T.; Kohler, Y.; Coletti, M.; Micol, M. Challenges to Green Infrastructure Valorisation and Policies to overcome them. In Shaping a Sustainable Future with Green Infrastructure; Sprint24: Milan, Italy, 2022; pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hersperger, A.M.; Bürgi, M.; Wende, W.; Bacău, S.; Grădinaru, S.R. Does landscape play a role in strategic spatial planning of European urban regions? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 194, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Armeni, C.; Cendra, J.D.; Chaytor, S.; Lock, S.; Maslin, M.; Redgwell, C.; Rydin, Y. Public Participation and Climate Change Infrastructure. J. Environ. Law 2013, 25, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkarthofer, E.; Humer, A.; Mäntysalo, R. Regional planning: An arena of interests, institutions and relations. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granberg, M.; Bosomworth, K.; Moloney, S.; Kristianssen, A.-C.; Fünfgeld, H. Can Regional-Scale Governance and Planning Support Transformative Adaptation? A Study of Two Places. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptist, M.; Van Hattum, T.; Reinhard, S.; Van Buuren, M.; De Rooij, B.; Hu, X.; Van Rooij, S.; Polman, N.; Van Den Burg, S.; Piet, G.; et al. A Nature-Based Future for the Netherlands in 2120; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, W.; Lenzholzer, S.; Voskamp, I.; Struckman, L.; Maagdenberg, G.; Weppelman, I.; Mashhoodi, B.; Dill, S.; Cortesão, J.; De Haas, W.; et al. The City of 2120: All Natural! Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskamp, I.; Timmermans, W.; Roosenschoon, O.; Kranendonk, R.; Van Rooij, S.; Van Hattum, T.; Sterk, M.; Pedroli, B. Long-Term Visioning for Landscape-Based Spatial Planning—Experiences from Two Regional Cases in The Netherlands. Land 2022, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterschap Vallei en Veluwe. 2024. Available online: https://www.vallei-veluwe.nl/kennisapp/kennisapp/waterschap-vallei/ (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Wet Gemeenschappelijke Regelingen (Wgr). 1985. Available online: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0003740/2022-07-01 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Groene Metropoolregio Arnhem-Nijmegen. 2024. Available online: https://www.gmr.nl/actueel/groene-metropoolregio-arnhem-nijmegen-groene-groei-voor-nederland/ (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- INE. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spanish Statistical Office). ‘Nomenclátor, Nomenclátor: Población del Padrón Continuo por Unidad Poblacional’. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177010&menu=resultados&secc=1254736195526&idp=1254734710990#!tabs-1254736195518 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- European Commission. ‘Communication of the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives’, COM/2020/380 Final. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0380 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Valladares, F.; Gil, P.; Forner, A. Bases Científico-Técnicas Para La Estrategia Estatal de Infraestructura Verde y de La Conectividad y Restauración Ecológicas; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2017; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Carrera, R.M. La Investigación Cualitativa A Tr Avés De Entrevistas: Su Análisis Mediante La Teoría Fundamentada. Cuest. Pedagógicas 2014, 23, 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 28492–28518. Available online: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=Xr12kpEP3G (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Bodin, Ö.; Prell, C. (Eds.) Social Networks and Natural Resource Management: Uncovering the Social Fabric of Environmental Governance, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, J.; Schmidt, J.; Werner, A. Using social network analysis to identify key stakeholders in agricultural biodiversity governance and related land-use decisions at regional and local level. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.-L.; Pósfai, M. Network Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. In Proceedings of the Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009; Volume 3, pp. 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskamp, I.; Roosenschoon, O.; Timmermans, W.; Jaarsma, M.; Akkermans, R.; Hofland, S.; Spek, T.; Woolderink, H.; van Moûrik, M.; Vredenbregt, P.; et al. Een Watergestuurde Regio: Vallei en Veluwe in 2120; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/een-watergestuurde-regio-vallei-en-veluwe-in-2120 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Voskamp, I.M.; Spek, T.; Woolderink, H.A.G.; Bolman, A.; Vredenbregt, P.A.; Moûrik, M.C.; Hofland, S.E.; Akkermans, R.; Jaarsma, M.; de Rooij, L.L.; et al. Vallei en Veluwe: Natuurlijk een Gevarieerde Regio: Bodem, Ondergrond en Watersysteem in Kaart; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/vallei-en-veluwe-natuurlijk-een-gevarieerde-regio-bodem-ondergron (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Voskamp, I.M.; Timmermans, W.; Mourik, M.C.; Vredenbregt, P.A.; Woolderink, H.A.G.; van Klaveren, E.S.; Dill, S.N.T.; van Apeldoorn, D.F.; Verstand, D.; van Linge, J.M.; et al. Welkom in de Toekomst!: Groene Metropoolregio Arnhem-Nijmegen: Een Visie Voor 2120; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, Nederland, 2023; Available online: https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/welkom-in-de-toekomst-groene-metropoolregio-arnhem-nijmegen-een-v (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Voskamp, I.; Timmermans, W.; Woolderink, H.; Van Klaveren, S.; Verstand, D. Toekomstverwachtingen en Landschappelijke Kenmerken Als Onderlegger Voor Een Regionale Visie: Onderliggende Analyseresultaten Voor de Toekomstvisie Groene Metropoolregio 2120; Wageningen Environmental Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Galicia, X. LEY 5/2019, de 2 de Agosto, del Patrimonio Natural y de la Biodiversidad de Galicia. 2019. Available online: https://www.xunta.gal/dog/Publicados/2019/20190807/AnuncioC3B0-020819-0001_es.html (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- de Galicia, X. ORDEN de 4 de Octubre de 2024 Por la Que Se Aprueba la Estrategia Gallega de la Infraestructura Verde y de la Conectividad y Restauración Ecológicas. 2025. Available online: https://www.xunta.gal/dog/Publicados/2025/20250210/AnuncioG0760-130125-0009_es.html (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Bryson, J.M.; Edwards, L.H.; Van Slyke, D.M. Getting strategic about strategic planning research. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.J.; Pauw, W.P.; Van Buuren, M.W.; Marfai, M.A. Governance of flood risk management in a time of climate change: The cases of Jakarta and Rotterdam. Environ. Polit. 2013, 22, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trell, E.-M.; Van Geet, M.T. The Governance of Local Urban Climate Adaptation: Towards Participation, Collaboration and Shared Responsibilities. Plan. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangen, S.; Huxham, C. Enacting Leadership for Collaborative Advantage: Dilemmas of Ideology and Pragmatism in the Activities of Partnership Managers. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, S61–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, A. How participation influences the perception of fairness, efficiency and effectiveness in environmental governance: An empirical analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilliers, E.J.; Timmermans, W. The Importance of Creative Participatory Planning in the Public Place-Making Process. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2014, 41, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T. What collaborative planning practices lack and the design cycle can offer: Back to the drawing table. Plan. Theory 2021, 20, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandrita, D.M. Improving Strategic Planning: The Crucial Role of Enhancing Relationships between Management Levels. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vente, J.; Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C.; Valente, S.; Newig, J. How does the context and design of participatory decision making processes affect their outcomes? Evidence from sustainable land management in global drylands. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, M.B. The Role of Stakeholders in Improving Management Practices of Urban Green Infrastructure in Southern Ethiopia. Plan. Pract. Res. 2020, 35, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbakidze, M.; Dawson, L.; Andersson, K.; Axelsson, R.; Angelstam, P.; Stjernquist, I.; Teitelbaum, S.; Schlyter, P.; Thellbro, C. Is spatial planning a collaborative learning process? A case study from a rural–urban gradient in Sweden. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.; Valle, R. ‘La generación de confianza y sus efectos sobre el comportamiento’. In Estableciendo Puentes En Una Economía Global; Escuela Superior de Gestión Comercial y Marketing: Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain, 2008; Volume 1, 29p, ISBN 978-84-7356-556-1. [Google Scholar]

- Camelo-Ordaz, C.; García-Cruz, J.; Sousa-Ginel, E. Antecedents of relationship conflict in top management teams. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2014, 25, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Searle, K.; Butler, A.; Simmons, P.; Watt, A.D.; Jordan, A. The role of trust in the resolution of conservation conflicts. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 195, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, M.; Johnson, L.; Pojani, D. Discretion and the erosion of community trust in planning: Reflections on the post-political. Geogr. Res. 2018, 56, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, C.M. Understanding barriers to green infrastructure policy and stormwater management in the City of Toronto: A shift from grey to green or policy layering and conversion? J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 1377–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.E. Resilience to Surprises through Communicative Planning. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.M.; Newig, J. From Planning to Implementation: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches for Collaborative Watershed Management. Policy Stud. J. 2014, 42, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Carter, C.; Reed, M.R.; Larkham, P.; Adams, D.; Morton, N.; Waters, R.; Collier, D.; Crean, C.; Curzon, R.; et al. Disintegrated development at the rural–urban fringe: Re-connecting spatial planning theory and practice. Prog. Plan. 2013, 83, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, A.; Driessen, P.; Teisman, G.; Van Rijswick, M. Toward legitimate governance strategies for climate adaptation in the Netherlands: Combining insights from a legal, planning, and network perspective. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. Transitions towards adaptive management of water facing climate and global change. Water Resour. Manag. 2006, 21, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetoo, S. Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Climate Governance: The Case of the City of Turku. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. A turning point for planning theory? Overcoming dividing discourses. Plan. Theory 2015, 14, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Rok, A. Co-producing urban sustainability transitions knowledge with community, policy and science. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 29, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Erickson, T.A. Co-production of knowledge–action systems in urban sustainable governance: The KASA approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 37, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balz, V.E. Regional design: Discretionary approaches to regional planning in The Netherlands. Plan. Theory 2018, 17, 332–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.D. Climate, climate change and range boundaries: Climate and range boundaries. Divers. Distrib. 2010, 16, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chan, K.M.A.; et al. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Varela, E.; Fernández-Villar, G.; Diego-Fuentes, A. Transformative Change in Peri-Urban SEPLS and Green Infrastructure Strategies: An Analysis from the Local to the Regional Scales in Galicia (NW Spain). In Fostering Transformative Change for Sustainability in the Context of Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS); Nishi, M., Subramanian, S.M., Gupta, H., Yoshino, M., Takahashi, Y., Miwa, K., Takeda, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Losada-Iglesias, R.; Díaz-Varela, E.R.; Timmermans, W.; Miranda, D. Analysis of Strategic Green Infrastructure Planning Guided by Actors’ Perceptions: Insights at the Regional Level in the Netherlands and Spain. Land 2025, 14, 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040760

Losada-Iglesias R, Díaz-Varela ER, Timmermans W, Miranda D. Analysis of Strategic Green Infrastructure Planning Guided by Actors’ Perceptions: Insights at the Regional Level in the Netherlands and Spain. Land. 2025; 14(4):760. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040760

Chicago/Turabian StyleLosada-Iglesias, Rocío, Emilio R. Díaz-Varela, Wim Timmermans, and David Miranda. 2025. "Analysis of Strategic Green Infrastructure Planning Guided by Actors’ Perceptions: Insights at the Regional Level in the Netherlands and Spain" Land 14, no. 4: 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040760

APA StyleLosada-Iglesias, R., Díaz-Varela, E. R., Timmermans, W., & Miranda, D. (2025). Analysis of Strategic Green Infrastructure Planning Guided by Actors’ Perceptions: Insights at the Regional Level in the Netherlands and Spain. Land, 14(4), 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040760