Abstract

This study utilized data from 300 prefecture-level cities in China, spanning from 2000 to 2020, and employed a difference-in-differences (DID) model to investigate the influence of land development rights on agricultural land prices, alongside the mechanisms underlying this relationship. The primary aim of this research was to analyze the manner in which land development rights affect agricultural land prices through the implementation of policies and market forces. Via empirical analysis, the study elucidated the effects of land development rights on agricultural land prices within China. The key findings include the following: (1) Land development rights positively influence the increase in agricultural land prices. (2) Land development rights significantly narrow the urban–rural income disparity at municipal and county levels, which in turn impacts agricultural land prices. (3) The effect of land development rights on agricultural land prices is negatively moderated by regional economic growth. (4) While land development rights significantly enhance the prices of arable land, their impact on sectors such as agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishing, and food processing remains minimal. (5) In northern regions and economically underdeveloped areas, land development rights substantially boost agricultural land prices, underscoring their role in fostering local economic development and enhancing land use efficiency.

1. Introduction

The optimization of spatial allocation of national land resources is an ongoing endeavor characterized by distinctive developmental features and relevance to contemporary issues. Land development rights encompass the entitlements of land users within a predefined legal framework, to develop, utilize, or transfer land consistent with national or local policies [1]. These rights enable farmers and landowners to participate more dynamically in the land market, enhance the distribution of land resources, and foster effective land utilization. As China progresses in its economic modernization, refining the spatial development pattern through land system reforms emerges as a pivotal strategy. This approach not only bolsters national economic performance but also elevates China’s stature as a major global power. In the context of globalization, optimizing policies and economic structures enhances a nation’s international image, thereby boosting its global competitiveness and influence. This aspect is particularly vital for fostering the sustainable development of rural economies [2].

Internationally, the evolution of land development rights and the formulation of related policies have a rich history, as evidenced by practices in the United States and the Netherlands [3]. In the United States, the Land Act of 1862 and subsequent legislation encouraged farmers and immigrants to acquire land in the Western regions for settlement and agricultural purposes. Concurrently, the Dutch government enforced rigorous land management policies, including land expropriation and the issuance of planning permits, to ensure the rational use of land resources and ecological conservation [4].

In China, the Communist Party and the government have only recently prioritized the regulation of land development rights. In October 2016, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council published the “Opinions on Improving the Method of Separating Ownership, Contractual Rights, and Management Rights of Rural Land”. This policy delineates the ownership, contractual rights, and management rights within the framework of rural land property rights, thereby clarifying the approach to “three rights separation” in rural land development [5]. The “No. 1 Central Document” of 2024 further advocates for a cautious and systematic strategy towards comprehensive land consolidation at the township level. This approach is designed to amalgamate and rejuvenate fragmented and underutilized rural lands while preserving sufficient land for rural infrastructure and industrial advancement. This policy initiative addresses the prevalent issue of fragmented and small-scale landholdings in China, where the average farm size is less than half an acre. This size constraint substantially hinders the adoption of modern agricultural technologies and equipment. In stark contrast, the average farm in the United States covers approximately 400 acres, which facilitates economies of scale and the effective employment of contemporary machinery, often leading to more efficient land utilization. Land transfer mechanisms serve as an effective market-based approach to reallocate land development rights by facilitating the transfer of land contractual management rights or land use rights [6].

“Contractual management rights” are defined as legal entitlements under a contract that permit an entity or individual to manage, utilize, or make decisions concerning the land despite the ownership potentially being held by another party. These rights, typically designated for specific uses such as agriculture or development, can be transferred, leased, or subleased according to the contractual terms, thereby enhancing the optimal use of land resources. Moreover, the role of government approval is pivotal in the process of land use changes. Through rigorous approval procedures, the government ensures that land use conforms to national planning objectives, conserves arable land, maintains ecological balance, and fosters sustainable economic and social development [7]. Particularly in the transition of agricultural land to non-agricultural purposes, an effective government approval mechanism is crucial in preventing unsustainable development and unregulated land expansion. Strict regulatory measures are implemented to oversee and control land development, including explicit guidelines on zoning, land allocation, and land use conversion. These policies are instrumental in limiting speculative activities and ensuring land is allocated for its most efficient and productive uses. Moreover, the implementation of land development rights in China plays a vital role in restricting excessive urban sprawl and preventing uncontrolled land use changes. Governed by both centralized and localized policies, land development rights are essential in curbing speculative practices. These measures not only ensure that land is used productively but also protect against market fluctuations that could lead to unregulated land price inflation or speculative bubbles, thus safeguarding social stability and production in rural areas [8].

In China, the current market for land transfer encounters substantial challenges, which include a disorganized pricing mechanism for agricultural land and a low degree of marketization in transaction processes [8]. These difficulties are exacerbated by an asymmetry of information and inefficiencies in governmental approvals, both of which hinder the optimal allocation and efficient utilization of land resources. In rural areas, where land serves as a critical factor of production, its rational allocation and effective use are increasingly essential for advancing agricultural modernization and addressing the “three rural issues”—agriculture, rural areas, and farmers [9].

Unchecked increases in land prices can foster speculative activities, driven by the anticipation of future price gains [10]. When land prices escalate rapidly due to speculative behavior, investors and other market participants are incentivized primarily to purchase land for capital gains rather than for productive purposes. This speculative demand skews the actual supply–demand equilibrium, treating land more as a financial asset than as a resource for agricultural production. As speculation escalates, the market may become disconnected from the land’s true economic value, resulting in the misallocation of land resources. Consequently, land that could have been utilized for productive agricultural purposes may be left idle or repurposed for non-agricultural uses, thus creating inefficiencies. Moreover, the artificial inflation of land prices complicates the ability of farmers to acquire land at reasonable prices, thereby hindering effective land redistribution. This disruption in the rational circulation of land, caused by speculative actions, distorts the normal flow of land between owners and users, ultimately undermining the efficient allocation of agricultural land and threatening the broader landscape of land utilization in China, including industrial uses.

Between 2000 and 2020, the area designated as agricultural land in China expanded from 5,237,310 km2 to 5,285,081 km2, reflecting an average annual growth rate of 0.91%. Concurrently, since the beginning of the 21st century, the overheated real estate market has fueled urban construction demands, encroaching upon rural land. This encroachment is particularly evident in the substantial conversion of arable land to construction land, a prevalent phenomenon in rural China. From 2002 to 2016, the area of China’s urban built-up regions swelled from 25,972.55 km2 to 54,331.47 km2, representing an annual growth rate of 7.80%. Remarkably, over 80% of this urban expansion was derived from the conversion of rural land. While urban expansion has underpinned the material foundation for economic and social activities, its reliance on expanding urban land has constricted the space available for rural development, thereby exacerbating urban–rural disparities and impeding the realization of shared prosperity within a socialist framework [11]. The implementation of land development rights presents an innovative strategy for resolving the issue of agricultural land being encroached upon by urban development. Market-based land transfers invigorate land circulation and diversification, thereby prompting land management authorities to adapt their utilization strategies with greater flexibility. Landowners can profit from market transactions, while acquirers benefit from scaled production, ultimately fostering a win–win scenario that enhances national spatial planning and socio-economic benefits [12].

In this analysis, the 2015 Central No. 1 Document titled “Opinions on Intensifying Reform and Innovation to Accelerate Agricultural Modernization” offers explicit guidance regarding the standardized transfer of land management rights and the innovation of transfer models and large-scale management strategies [5]. The document stringently prohibits unauthorized alterations in the agricultural use of land, advocating for the infusion of industrial and commercial capital into modern agricultural industries, encompassing farming, processing, distribution, and agricultural social services. This initiative serves as an effective pilot for deepening rural reform, stimulating rural socio-economic development, and enabling the replicable exploration of resource asset management. Transactions involving land development rights present new investment opportunities for external investors, facilitating the efficient allocation and fluid movement of land elements within an open market [1]. Moreover, they promote the scientific and rational utilization of agricultural land, which, as a non-renewable natural resource, supports diverse uses, including agriculture, forestry, livestock, fisheries, and specific regions dedicated to the agri-food industry. The scientific configuration and rational use of these lands are essential for addressing the “three rural issues”—rural poverty, rural education, and rural labor migration—and for advancing agricultural modernization. This study examined the extent to which and mechanisms by which land development rights influence agricultural land prices in China, providing both a theoretical and practical foundation for the effective realization of these rights and the enhanced management of agricultural land prices.

Building on the aforementioned analysis, this study investigated the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices from the perspective of policy mechanisms, utilizing land market transaction data spanning from 2000 to 2020. The research offers valuable theoretical support and practical insights for refining policies on land development rights, enhancing land prices, stabilizing economic structures, and promoting sustainable agricultural development. By delving into the mechanisms through which land development rights affect the agricultural land market, this study contributes to optimizing land resource allocation, fostering a robust land market, and laying the groundwork for formulating more scientifically grounded and rational land management policies. The marginal contributions of this study are as follows: Firstly, the causal relationship between land development rights and land governance has been underexplored. By elucidating this causal link, the study introduces a novel perspective into the theory of land governance, fostering innovation in this domain. Secondly, the study offers unique insights into land asset allocation, analyzing the practical operation of land development rights within China’s unique socio-economic context. Thirdly, by examining the interplay between land transfer and policy guidance, this study expands the research framework on land governance, thereby enriching theories related to land marketization and the effective allocation of land resources.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature Review on Land Development Rights and Related Transactions

Land development rights, which have their origins in the Urban and Rural Planning Law, underwent significant evolution throughout the 20th century [1,3]. The primary impetus for the emergence of land development rights has been the increasing pressure on land demand, driven by urban redevelopment and population expansion [13]. This pressure has necessitated the imposition of limitations on the absolute nature of land ownership, delineated through spatial and surface rights [14]. Essentially, land development rights facilitate the transfer of land use rights, operating as a distinct category of property rights. These rights decouple the land use rights from the rights to income generated from the land. For example, the government in Florida augmented its land resource base via the Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) program. This bifurcation of land property rights has enabled more precise land management and has contributed significantly to local economic development [15].

Furthermore, land development rights encapsulate the characteristics of property, revenue, and equity within the dichotomous urban–rural framework [16]. They delineate the roles and responsibilities of landowners, users, and the state in the processes of land development, utilization, and transfer. Concurrently, these rights provide farmers with mechanisms for land trading and transfer that enhance their economic returns and improve their living conditions. Importantly, land development rights can mitigate excessive urban sprawl into agricultural areas, thus preserving the ecological functions and agricultural productivity of farmland to a certain degree [17].

Research highlights that land development rights serve as both a restrictive and enabling mechanism within land use planning [18]. These rights not only solidify the foundation of rural communities by protecting farmers’ land rights but also foster broader social harmony and stability. Nevertheless, there remains a paucity of research on the spillover effects that precede land development, particularly concerning the housing market [19].

2.2. The Formation and Characteristics of Agricultural Land Prices in China

The primary factors influencing land prices are predominantly reflected in the supply and demand theory, which posits that prices are determined by the balance between these two forces [20]. In this dynamic, farmers, motivated by rising prices of agricultural products, are inclined to increase their supply to capitalize on higher profits. Concurrently, an increase in market demand for these products, indicative of heightened consumer interest, further escalates prices. However, due to the significant impact of governmental policies on land prices in China, land cannot be regarded merely as a traditional commodity [21]. While it exhibits characteristics of a commodity, with prices influenced by supply and demand, policy interventions are crucial to ensure that land prices remain within a specific range. According to the supply and demand theory, the level of land prices is also shaped by its expected or actual returns [22]. Land serves not only as the primary means of production for laborers but also encapsulates real rent and labor inputs. This view, rooted in the equilibrium of the land market, emphasizes three fundamental elements in price formation: land’s scarcity, utility, and market demand [23,24].

Moreover, in comparison to urban land prices, agricultural land is distinguished by its immobility and scarcity. Within the framework of collective land ownership in China, agricultural land prices still demonstrate a degree of passivity [25,26]. Nonetheless, debates persist, primarily concerning the representation of the value of agricultural land prices, including aspects such as collective characteristics, production differences, urban-rural conflicts, and appreciation. Previous studies have shown that agricultural land prices in China exhibit unique collective value-added characteristics influenced by government policies, market demand, regional development, and potential factors [21,27]. However, there remains a paucity of research analyzing the relationship between land development rights and agricultural land prices.

2.3. The Price Linkage Mechanism of Land Development Rights

Land development rights are directly reflected in land prices, and the formation of these prices involves a complex interplay of multiple dimensions and factors. These include the geographical advantages of the location, the unique attributes of the land parcel, dynamics of market demand, and fluctuations in the financial markets [28]. It is important to recognize that traditional methods of determining land prices often deviate from the foundational principles of classical economic theory and do not fully align with the objective laws of socio-economic development [29].

As a result, a distinct pricing mechanism for land development rights has emerged, which substantially relies on mathematical modeling and the application of sophisticated algorithms for price determination [30]. This approach, to some extent, neglects the multifaceted factors, dynamic changes, and complex socio-economic contexts that influence the actual operation of land markets. This oversight represents a critical area for further investigation in this study.

2.4. Conclusion of Literature Review

In summary, extant research has predominantly concentrated on the determinants that influence the relationship between land development rights and agricultural land prices. Nevertheless, the literature that explores the dynamic interplay between these factors remains scarce, particularly concerning empirical investigations on agricultural land. In practical settings, the relationship between land development rights and the pricing of various types of land displays distinct characteristics [31]. This relationship acts as a conduit for land transfers within the framework of rural revitalization and constitutes a vital component for advancing rural economic development and maintaining social stability.

In the context of China’s longstanding dual urban–rural economic structure, both central and local governments frequently regard land as a pivotal instrument for economic regulation and price stabilization, which in turn fosters local economic growth. However, the unchecked expansion of urban territories not only catalyzes economic development but also precipitates the substantial reduction of rural land [32]. Within the ambit of China’s pursuit of high-quality development, the role of land development rights, particularly in terms of land transfers, in mediating the disparities in income between urban and rural areas and the fluctuations in agricultural land prices represents a critical issue that this study aimed to elucidate.

3. Theoretical Analysis

3.1. The Direct Effects of Land Development Rights on Agricultural Land Prices in China

Land is a fundamental source of income for farmers, and land development rights indirectly expand the opportunities for farmers to augment their income. On one hand, land development rights are crucial for land resource planning, employing administrative measures to implement policies that exert a “transfusion” effect. On the other hand, farmers generate income by cultivating land, and they can also capitalize on it through market-based leases or receive rental income via other government-sanctioned mechanisms [31]. Prompted by these dual influences, when previously idle rural land is allocated for construction purposes, the total land stock is altered, yet the proportion of land deemed usable escalates. This adjustment emanates positive signals to the market, enticing a broader array of stakeholders into the rural land market and thus elevating land prices [33].

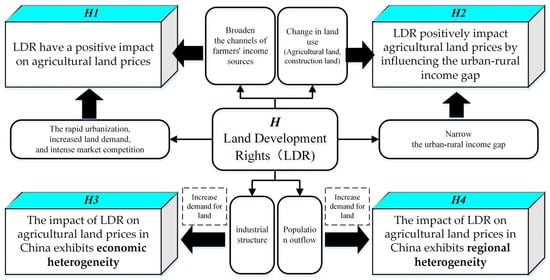

Based on these observations, this study proposes the theoretical hypothesis:

H1.

Land development rights exert a positive influence on agricultural land prices.

3.2. Land Development Rights, Urban–Rural Income Gap, and the Transmission Mechanism of Agricultural Land Prices in China

Alterations in land development rights indirectly impact agricultural land prices by enriching farmers’ channels of income and diminishing the urban–rural income gap [1]. Initially, land development rights enhance both the utility and economic value of land, thereby expanding the avenues for increasing farmers’ income. This augmentation assists in lessening the disparity in income between urban and rural areas, fostering the achievement of shared prosperity. Under these conditions, land initially earmarked for construction is redirected for agricultural utilization [34]. This shift, to a certain degree, elevates the overall price levels in urban land markets, enabling cities to support more economic activities, including developments that yield substantial economic returns and tax revenues. This optimization maximizes the economic and social value of the land. Based on this understanding, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Land development rights positively impact agricultural land prices by increasing the urban–rural income gap.

3.3. Regional Distribution of Agricultural Land Prices in China: Cross-Sectional Effects

The influence of land development rights on agricultural land prices exhibits regional variability contingent upon differing levels of economic development. In regions characterized by advanced economic development, where the land market is more established and land prices comparatively high, the incremental effect of land development rights diminishes [35]. Consequently, in these areas, agricultural land prices are more significantly affected by competition from non-agricultural industries [21]. Conversely, in regions with less economic development, the positive effects of land development rights on agricultural land prices are more marked. Several factors contribute to this phenomenon. Firstly, demographic shifts resulting in population outflow precipitate a labor shortage within the agricultural sector, which in turn increases the liquidity of land and drives up land prices. Secondly, there is an escalation in market expectations as land utilization efficiency remains low; the establishment of development rights fosters enhanced expectations of value addition. Thirdly, the presence of high-quality agricultural resources attracts investments, and the support of local government policies further amplifies land prices. Fourthly, improvements in institutional frameworks, as evidenced by the standardization of land transactions through the establishment of development rights, augment the market value of land. In light of these observations, it becomes evident that the bolstering effect of land development rights on agricultural land prices is more prominent in economically underdeveloped regions. This leads to the formulation of the following hypothesis:

H3.

In regions with lower levels of economic development, the positive impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices in China is more pronounced.

The influence of land development rights on agricultural land prices in China demonstrates notable regional disparities. Initially, considering land supply, demand, and market competition, the northern regions are undergoing rapid urbanization and face intensified competition in the land market. Consequently, there exists a robust demand for transforming agricultural land into non-agricultural uses. This dynamic facilitates a more pronounced transmission of the effects of land development rights to land prices. In contrast, the southern regions, despite experiencing demand for land, benefit from favorable hydrological and climatic conditions that enhance agricultural productivity. This results in a comparatively weaker impetus for land use conversion [36].

Furthermore, from the perspective of population mobility and labor supply, the northern regions exhibit relatively high population density. Recent years, however, have seen significant outmigration of agricultural labor, leading to a reduction in the rigid demand for agricultural land. The implementation of land development rights has augmented expectations for land circulation and redevelopment, thereby elevating land prices [37]. Conversely, the southern regions, characterized by a more robust agricultural industry chain, witness a milder impact on land prices, even amidst labor outmigration.

Additionally, concerning land systems and transaction regulations, the northern regions display more clearly defined collective land ownership and a more mature land market [35]. Therefore, the introduction of development rights more readily captures the value-added effects through market transactions. In contrast, in some southern regions, informal land transfers or unregulated transactions persist, and the market-driven influence of land development rights is relatively attenuated. Based on these observations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

The impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices in China exhibits regional heterogeneity.

Figure 1 delineates the theoretical mechanism by which land development rights affect agricultural land prices in China, serving as the foundation for the subsequent formulation of research hypotheses.

Figure 1.

The logical framework of theoretical analysis and hypotheses.

4. Research Design

4.1. DID Model

This study considers the introduction of the land development rights policy as an exogenous shock event. It employs a difference-in-differences (DID) model to examine the impact of the policy on agricultural land prices in different provinces and municipalities. The provinces and municipalities most affected by the land development rights policy are designated as the experimental group, while other provinces and municipalities are set as the control group. In Model (1), ß1 measures the differences between the experimental and control group samples. ß2 measures the differences within the sample before and after the implementation of land development rights, while ß3 captures the differential changes in agricultural land prices between the experimental and control groups before and after the policy implementation.

To test the effect of land development rights on agricultural land prices, the following two-way fixed effects model was constructed:

In Equation (1), LPi,t represents the agricultural land price; i and t denote the region and year, respectively; Controli,t refers to the control variables; αi and γt represent the individual and time effects, respectively; εi,t is the random disturbance term.

To investigate whether there is a transmission mechanism of urban–rural income disparity in the process of how land development rights affect agricultural land prices and drawing on the study, the following mediation effect model was constructed:

In Equations (2) and (3), URIGi,t represents the mediating variable of urban–rural income disparity, while the other variables maintain the same meaning as in Equation (1). Specifically, if both c3 and c4 are significant, it indicates a partial mediation effect. If c3 is not significant, but c4 is significant, it indicates a full mediation effect.

To test whether the regional development level plays a moderating role in the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices, this study constructed the following model (4):

With model (4), this study focused on the magnitude and significance of ß3. The variable Treated × Time × GDP represents the net effect of land development rights on agricultural land prices.

4.2. Sample Selection and Data Sources

Given the availability of data, this study utilized panel data on land transactions from 300 prefecture-level cities in China for the period 1999–2020. The land price data for each city were sourced from the China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook (1999–2020), while agricultural land data were obtained from the China Land website, with missing values supplemented by the corresponding year’s land yearbook. Control variables such as economic structure (ES), population growth rate (PGR), employment structure (EMPS), land resource endowment (LRE), local education expenditure (LEE), and total retail sales of social consumer goods (SRS) were sourced from the China City Statistical Yearbook (1999–2020). To mitigate the impact of extreme outliers, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The statistical analyses in this study were conducted using Stata 18.0.

4.3. Variable Definitions

4.3.1. Dependent Variable: Agricultural Land Price (LP)

In this study, the term “agricultural land” encompasses cultivated land, forestry land, agricultural services, and the agricultural processing industry. “Land price” refers to the transaction price of land in buying and selling exchanges, representing the actual amount exchanged during the transfer of land ownership. Data on agricultural land prices were sourced from the China Land Market website, with land parcels filtered according to their designated use, retaining data on cultivated land, forestry land, agricultural services, and agricultural processing industry land.

The total land transaction value and land transaction area for each city in a given year were calculated, and the average land transaction price for the city was determined by dividing the total transaction value by the total transaction area.

4.3.2. Key Independent Variable: Land Development Level (Treated × Time)

The 2015 Central Document No. 1 titled “Several Opinions on Accelerating Agricultural Modernization through Reform and Innovation” underscores the critical importance of confirming rural land ownership and reforming the land property rights system [16]. This policy document also emphasizes respecting farmers’ autonomy and willingness in the transfer of land management rights and stringently prohibits any unauthorized alterations to the original agricultural use of the land. Subsequently, in the same year, the General Office of the Communist Party of China and the State Council promulgated the “Opinions on the Pilot Work for Rural Land Expropriation, Collective Business Construction Land Marketization, and Homestead System Reform”, which selected 33 counties (cities) for pilot programs [38]. This 2015 Central Document No. 1 represents a pivotal shift in China’s approach to land policies, particularly concerning the transfer of rural land and the management of land development rights. Unlike the 2008 Chongqing Pilot, which was region-specific, the 2015 policy was implemented nationwide, providing clear directives for future land policies. This nationwide scope not only broadens its applicability but also offers a more comprehensive reflection of the impact of national policies on land development rights. Furthermore, while the 2008 Chongqing Pilot had a localized impact on the land market, its influence was confined to a single region. In stark contrast, the 2015 policy holds greater national relevance, thereby serving as a more suitable foundation for examining the relationship between the transfer of land development rights and land prices. Additionally, the 2015 policy facilitated the accelerated, nationwide implementation of land development rights transfer, leading to more standardized and institutionalized practices. This enhancement in policy implementation allows for a more effective assessment of the policy’s impact compared to the 2008 pilot, which was limited in scope and relevance at the national level. The pilot regions included various districts and counties from major cities such as Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai as well as provinces including Hebei, Shanxi, and Guangdong. Despite the geographical variations, land development rights experienced a uniform policy impact across the country. The consistency in policy mechanisms enables a comprehensive analysis of their overall effect on land prices. To account for heterogeneity, the study incorporated multidimensional control variables, such as provincial and temporal fixed effects, to ensure robust results that accurately capture the core impact of land development rights. In this analysis, municipalities and other cities were treated uniformly to enhance the sample’s representativeness and statistical reliability, thus facilitating a deeper understanding of the widespread impact of land development rights on land prices across different city types. In the designated pilot regions, the variable Treated is assigned a value of 1, whereas in non-pilot regions, it remains 0. This differentiation indicates whether the land in question is affected by the land development rights policy following its implementation. The time variable (Time) is also introduced; it is set to 0 for the years preceding the official proposal of the land policy in December 2015 and to 1 from 2016 onwards, marking the period after the implementation of the land development rights policy.

Based on the intensity of implementation and local economic development levels, provinces with more robust and widespread enforcement of land development rights policies tend to experience a greater impact. This effect is particularly pronounced in regions designated as central or local government pilot areas for land development policy or those that have implemented additional reform measures, such as land circulation, reclamation, and land use conversion. These areas are more advanced in releasing land development rights, advancing land marketization, and revising urban–rural land use policies. Consequently, their land markets are more dynamic, policy interventions more effective, and the impact on land prices more pronounced [23]. In contrast, economically underdeveloped regions with emerging land markets tend to exhibit slower policy implementation. In these locales, the implementation of land development rights is more restricted, resulting in weaker policy effects and less significant influence on land prices [39].

4.3.3. Control Variables

This study incorporates the following control variables:

- (1)

- Economic structure (ES): This variable captures the industrial composition of a region, where different types and structures of industries exert direct or indirect influences on land prices;

- (2)

- Population growth rate (PGR): In agricultural regions, population increases typically heighten the demand for food and agricultural products, subsequently elevating agricultural land prices;

- (3)

- Employment structure (EMPS): A higher proportion of agricultural-related employment in the employment structure tends to increase the demand for agricultural land. Conversely, as the proportion of non-agricultural industries increases, agricultural land may face heightened competition;

- (4)

- Land resource endowment (LRE): Attributes such as soil fertility, climate conditions, and geographical location determine a region’s agricultural production capacity and the market value of its land;

- (5)

- Local education expenditure (LEE): Elevated spending on education can enhance the quality of the local workforce, thereby influencing the labor market structure and agricultural productivity, which indirectly affects the demand for agricultural land;

- (6)

- Total social retail sales (SRS): Higher levels of retail sales typically indicate a prosperous economy and stronger consumer demand within a region, suggesting a higher demand for land, particularly for non-agricultural uses.

4.3.4. Mediating and Moderating Variables

The urban–rural income disparity (URIG) acts as the mediating variable and is measured by the income difference between urban residents and rural villagers. The economic development level (EDL) serves as the moderating variable, where the logarithm of regional gross domestic product (GDP) is utilized. Definitions of these variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definition table.

5. Research Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Univariate Difference Test

The results of the descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 2. The average logarithm of agricultural land prices in China stands at 4.732, ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 11.002. These figures suggest that the general level of agricultural land prices in China is moderate to low. Additionally, the mean value of the interaction term Treated × Time is 0.05, indicating that approximately 5% of the sample is affected by the land development rights policy. This observation implies that China is still in a relatively nascent phase of achieving sustainable development.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

The strategic allocation and transfer of land development rights are pivotal in promoting sustainable development by enhancing resource efficiency and refining the structure of the agricultural industry. This mechanism ensures optimal land use, stimulates economic growth, and reduces waste and inefficiency. In particular, the issuance of land development rights and the enhancement of the land transfer market afford farmers the opportunity to participate in market activities, which in turn boosts their income. This increment in income helps to diminish the income disparity between urban and rural areas, fostering social and economic stability. Consequently, the prudent distribution of land development rights not only propels economic growth but also supports long-term stability and balanced development across urban and rural regions.

5.2. DID Results

Table 3 accounts for the effects of regional heterogeneity and temporal trends by incorporating provincial and year fixed effects, and it employs city-level clustered standard errors. As illustrated in column (1), the implementation of land development rights exerts a statistically significant positive impact on agricultural land prices at the 1% significance level. This increase can be ascribed to the allowance provided by land development rights for landowners or users to alter the land’s usage, emphasizing “increasing tolerance” and adopting a “spatial expansion strategy” as primary methods to realize prospective profit gains. This enhanced potential value attracts more investors and developers to the market, consequently elevating agricultural land prices.

Table 3.

The impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices in China.

Columns (2), (3), and (4) demonstrate that land development rights affect agricultural land prices through the urban–rural income disparity. These rights ensure that land can generate economic benefits when repurposed, and the distribution of land value appreciation between urban and rural areas becomes more equitable.

Farmers, as direct users and beneficiaries, reap substantial gains from land development, thus narrowing the urban–rural income gap. As this disparity diminishes, rural land resources are utilized more effectively. This improved allocation amplifies the scarcity and value of agricultural land, positively influencing agricultural land prices. As indicated in column (5), there is a significant positive correlation between land development rights and agricultural land prices. The acceleration of urbanization and population growth intensifies the demand for construction land. Land development rights facilitate the potential conversion of agricultural land into construction land, thereby satisfying the market’s demand for land. The increased demand naturally drives up agricultural land prices.

Considering the “Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Deep Integration of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Industries” issued by the General Office of the State Council in 2016, which explicitly encourages China to actively explore and promote diversified models of rural industrial integration and to further extend and enhance the agricultural industry chain, it is clear that the scope of agricultural land is not confined solely to farmland for primary crop production. It also encompasses rural construction land for the initial processing of agricultural products and auxiliary lands for production–sales linkages, such as warehousing, logistics, and wholesale markets. In response to this directive, this study reclassified land types following the implementation of land development rights into categories including agricultural land, agroforestry–animal husbandry–fishery services, and agro-processing industries. These categories were subsequently analyzed through group regressions. As demonstrated in columns (6), (7), and (8) of Table 1, land development rights show a significant positive correlation with agricultural land prices, as illustrated in column (6). This finding aligns with those of columns (1) and (2), thereby validating Hypothesis 1 (H1). However, as indicated in columns (7) and (8), land development rights do not significantly impact the prices of land designated for agroforestry–animal husbandry–fishery services or agro-processing industries. A plausible explanation for this observation is that land development rights primarily target shifts in land use demand and intensification based on rational spatial planning, aiming to maximize land use benefits functionally. Specifically, farmland, as a critical input for agricultural production, directly impacts food security for China’s 1.4 billion population.

The enforcement of development rights over farmland directly influences this essential element, as maintaining the “red line” for cultivated land is crucial for sustaining high-quality agricultural development. The transfer of ownership of farmland will inevitably have a significant impact on its market value, affecting not only agricultural product prices but also various prices within the extended agricultural industry chain. The market’s recognition of agricultural product prices directly enhances the practical value of the land and, consequently, its price.

In contrast, land designated for agroforestry–animal husbandry–fishery services and agricultural and sideline food processing is typically classified as rural construction land. This type of land generally has a longer usage duration, and the scale and purpose of fixed investments tend to be more stable, primarily used for the deep processing of agricultural products, forestry, aquatic product processing, and specialty agricultural development such as leisure and service agriculture. Deep processing often involves adding value or enhancing the functionality of primary agricultural products through technical methods or processing techniques. Compared to urban construction land or commercial development land, the land development intensity for agroforestry–animal husbandry–fishery services and agro-processing industries is typically lower. Consequently, the value enhancement from land development rights in the extension of the agricultural industry chain is often concentrated on the improved efficiency of production technology rather than an increase in the intrinsic value of land as a basic input. Thus, the potential for value appreciation in these sectors is relatively limited.

5.3. Robustness Test

5.3.1. Parallel Trend Test

The foundational premise of the difference-in-differences (DID) methodology [40] is predicated on the assumption that, during the pre-policy era (2005–2014), prior to the complete manifestation of the land development rights policy and its effects on the land market, the trends in both the experimental group (pilot cities) and the control group (non-pilot cities) would remain largely consistent. In other words, there should be no significant disparities between the two groups. This research utilized pilot cities designated by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council in 2015 to delineate the experimental and control groups. The study constructed interaction terms between the annual time dummy and the experimental group dummy. These interaction terms served as annual trend variables and were incorporated as explanatory variables in the primary regression model, with agricultural land prices as the dependent variable. The coefficient of the interaction term elucidates the differential effects between the experimental and control groups in 2015. It was anticipated that the coefficients of the annual trend variables prior to policy implementation would not be statistically significant. As indicated by the parallel trend test regression results in Table 4, the regression coefficients for the annual trend variables during 2005–2014 are all statistically insignificant, confirming that the sample groups adhere to the common trend assumption prior [16] to the enactment of the “Land Development Rights” policy.

Table 4.

Parallel trend test results.

5.3.2. Placebo Test

In order to determine that the observed differences between the experimental and control groups are attributable solely to the land development rights policy and not influenced by other uncontrollable factors or temporal variations within the policy framework, this study conducted a placebo test. The study randomly assigned experimental groups from the sample and performed the placebo test 500 times to evaluate the robustness of the findings. The distribution of the t-values for the interaction term Treated × Time demonstrates that the coefficients of the interaction term, representing the impact of the land development rights policy on agricultural land prices, conform to a normal distribution with a mean of zero. This result substantiates the absence of a treatment effect in the randomly constituted experimental groups, aligning with the anticipated outcome of the placebo test.

5.3.3. Propensity Score Matching

To address the potential endogeneity issue arising from sample self-selection, this study employed propensity score matching (PSM) for verification. All control variables were utilized as covariates, and a 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement was implemented using a Logit model to select a control group that is closely comparable to the experimental group, yielding a total of 9531 samples. Subsequently, the study re-estimated the DID using the matched sample.

As depicted in Table 5, the significance and correlation coefficients remained substantially unchanged, confirming that the baseline regression results are robust and consistent with previous findings.

Table 5.

PSM–DID estimation results.

5.3.4. Data Sample Substitution Test

The anticipated implementation date for the proposed policy was December 2014. Adhering to the conventions established by prior policy studies and acknowledging the typical response delay at the provincial level, this study designated 2015 as the policy implementation year. However, it is important to consider that the introduction of a comprehensive policy is generally preceded by substantial research and pilot initiatives, potentially leading to anticipatory effects within the province. It is plausible that the province, foreseeing the policy’s trajectory, might have preemptively adjusted land resource allocation and agricultural land pricing strategies before the formal policy enactment.

Similar considerations apply to pilot cities, which may have experienced an extended adjustment period in terms of policy acceptance or reaction. Consequently, when a policy is introduced, pilot cities may exhibit either immediate or delayed responses, potentially introducing bias into the study’s outcomes.

To enhance the robustness of the research findings, this study excluded data from two years surrounding the policy implementation—specifically 2014 and 2015—to mitigate the effects of lag and anticipation [41]. The regression analysis, as shown in column (1) of Table 6, aligns closely with earlier results.

Table 6.

Data sample substitution test.

6. Heterogeneity Analysis

6.1. Regional GDP-Based Group Regression

GDP serves as an indicator of a region’s overall economic health and influences the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices across regions with varying GDP. The academic community widely acknowledges that provinces ranking in the top ten by GDP are characterized by higher per capita income, well-developed industrial sectors, advanced infrastructure, superior educational standards, and enhanced capabilities in technological innovation [42]. Consequently, provinces including Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Zhejiang, Henan, Sichuan, Hubei, Fujian, Hunan, and Anhui are classified within the high-GDP group, while other provinces fall into the low-GDP category. The regression analyses for these subgroups are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Regional GDP grouped regression.

The findings detailed in the table indicate that the regression coefficient for the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices is significantly positive at the 1% level, particularly in economically less developed regions. This effect is pronounced because, in regions with less developed land use, land resources tend to be allocated inefficiently, leading to underutilization or even idleness. By enabling market mechanisms such as land transfer and use changes, land development rights facilitate the optimization of land resource allocation strategies, thereby improving land use efficiency. As a result, land resources become more rationally allocated and effectively utilized, increasing their scarcity and value, which, in turn, drives up land prices.

6.2. Regional Differences Between the North and South

The southern region of China is defined as the area south of the Qinling–Huaihe Line in eastern China, while the northern region encompasses areas north of this line. Given China’s vast expanse, significant disparities exist in natural conditions and factor market development along this north-to-south vertical axis. These regional discrepancies may influence the efficacy of land development policies. To ascertain whether the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices exhibits regional heterogeneity, the sample was categorized based on this vertical division (north vs. south) for group analysis, as detailed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Regional differences between the north and south.

The findings indicate that the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices varies markedly between the northern and southern regions. Land development rights have a more pronounced effect on increasing agricultural land prices in the northern region, whereas their impact in the southern region is not significant. These results lend support to Hypothesis 3.

7. Conclusions, Policy Recommendations, and Limitations

7.1. Conclusions

This study rigorously investigated the effects of land development rights on agricultural land prices by analyzing transaction data from land markets spanning 300 cities across 31 provinces and municipalities in China over the period from 2000 to 2020. Additionally, it delved into the mediating role of the urban–rural income disparity in this relationship and assessed the moderating influence of regional GDP on the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices.

The principal findings are as follows: Firstly, land development rights have a positive influence on the escalation of agricultural land prices. Secondly, the impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices is substantial, with the urban–rural income gap serving as a partial mediator. Thirdly, regional economic growth acts as a positive moderator in the relationship between land development rights and agricultural land prices. Fourthly, in regions characterized by relatively slower economic development, land development rights markedly enhance agricultural land prices, underscoring their beneficial role in stimulating local economic growth and enhancing land use efficiency. Lastly, further analysis indicates that the influence of land development rights on agricultural land prices is more pronounced in northern regions, whereas in southern regions, this effect is not significant.

7.2. Recommendations

Based on the findings presented in this research, the following recommendations are proposed:

- (1)

- Enhance enforcement and increase transaction activity: It is crucial to strengthen the enforcement of land development rights and increase their transaction activity within the national spatial planning framework. By augmenting the proportion of collective land development rights, optimizing the structure of the land market, and encouraging their application across extensive areas, particularly in agricultural and infrastructure construction land, we can ensure a more dynamic and equitable land market;

- (2)

- Reshape the concept of land development rights and establish a universal framework: This recommendation involves expanding the transaction system of land development rights to include ecological lands such as forests, grasslands, and water bodies. Implementing such reform will likely lead to dual enhancements in economic efficiency and land use effectiveness, thereby supporting economic growth alongside the protection of these vital resources. Concurrently, it is crucial to predefine control conditions for land development rights within national spatial planning. Accurate delineation of the “three zones and three lines” (ecological, agricultural, and urban development spaces) is essential. Such precision ensures the protection of arable and ecological lands by establishing clear boundaries, including ecological protection red lines, permanent basic farmland, and urban development boundaries;

- (3)

- Promote inter-regional resource flow: The movement of land, capital, labor, and other resources between urban and rural areas as well as across different regions should be encouraged. This can be facilitated by creating policies that encourage such flows and establishing funding support platforms that enhance resource reallocation, thereby contributing to rural revitalization and overall economic flexibility;

- (4)

- Address regional economic disparities: Targeted policies should be developed reflecting regional economic conditions. For regions with slower economic development, particularly in the north, support should be intensified for land development rights to foster reasonable increases in agricultural land prices and stimulate local economic growth. Conversely, in the southern regions, focus should be on protecting land resources to prevent excessive development and mitigate price volatility;

- (5)

- Promote sustainable land resource utilization: During the promotion of land development rights transactions, it is imperative to strengthen the oversight of ecological protection to ensure sustainable land use. Policies should be crafted to maintain a balance where increases in agricultural land prices do not adversely affect ecological environments or the agricultural production base;

- (6)

- Utilize market mechanisms for sustainable development: Market mechanisms should be leveraged to advocate for and ensure a smooth and efficient flow of land, capital, human resources, and other production factors between urban and rural areas and across different regions. The goal should be to establish a unified and integrated market for construction land that can inject new vitality into both economic and social development.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This research introduces regional economic growth as a moderating variable and delves into the mechanistic impact of land development rights on agricultural land prices. Through rigorous empirical testing, the study offers conclusions of practical significance. Nevertheless, the study faces several limitations: Firstly, the analysis was confined to provincial-level data, and future research should extend to county-level data to provide a more exhaustive understanding of how land development rights influence agricultural land prices.

Secondly, the research currently addresses only the direct effects of land development rights on agricultural land prices and does not explore the intricate mechanisms and pathways through which these rights are influenced by pertinent policies, such as the “Land Management Law”, the “Rural Land Operation Right Transfer Management Measures”, and the “Guidelines for Urban Renewal Planning and Land Policy (2023 Edition)”. Future studies could examine the repercussions of these policies on the protection of cultivated land and the broader implications of land development rights.

Thirdly, this study is limited to a domestic perspective; future research should broaden its scope to include international and multi-regional analyses of land resource allocation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; Methodology, J.S.; Software, J.S.; Validation, J.S.; Formal analysis, J.S.; Investigation, J.S. and W.D.; Resources, J.S.; Data curation, J.S.; Writing—original draft, J.S.; Writing—review & editing, J.S.; Visualization, J.S.; Supervision, J.S. and W.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Huazhong Agricultural University Key Research Project Cultivation Special grant number [2662023JGPY002].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wen, L.; Chatalova, L.; Butsic, V.; Hu, F.Z.; Zhang, A. Capitalization of land development rights in rural China: A choice experiment on individuals’ preferences in peri-urban Shanghai. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïssaoui, R.; Fabian, F. Globalization, economic development, and corruption: A cross-lagged contingency perspective. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2022, 5, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Fan, Y.; Tang, H.; Liu, K.; Wu, S.; Zhu, G.; Jiang, P.; Guo, W. Research review on land development rights and its implications for China’s national territory spatial planning. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen-Jansen, L. Taking national planning seriously: A challenged planning agenda in the Netherlands. Administration 2016, 64, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X. Three rights separation: China’s proposed rural land rights reform and four types of local trials. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, R.; Lin, Z.; Chunga, J. How land transfer affects agricultural land use efficiency: Evidence from China’s agricultural sector. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lai, S.-K. National Land Use Management in China: An Analytical Framework. J. Urban Manag. 2012, 1, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shan, L.; Guo, Z.; Peng, Y. Cultivated land protection policies in China facing 2030: Dynamic balance system versus basic farmland zoning. Habitat Int. 2017, 69, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Tu, S.; Ge, D.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: Problems and prospects. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, K.; Chen, X. Land speculation by villagers: Territorialities of accumulation and exclusion in peri-urban China. Cities 2021, 119, 103394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Sakai, T. Urban expansion, economic development, and carbon emissions: Trends, patterns, and decoupling in mainland China’s provincial capitals (1985–2020). Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112777. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Bai, X.; Zhang, X.; Reis, S.; Chen, D.; Xu, J.; Gu, B. Urbanization can benefit agricultural production with large-scale farming in China. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, Z. Institutional Diversity of Transferring Land Development Rights in China—Cases from Zhejiang, Hubei, and Sichuan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X. The coupled relationships between land development and land ownership at China’s urban fringe: A structural equation modeling approach. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.S.Y.L. Progress in land science research in 2018 and prospects for 2019: A sub-report on land management. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, D.; Liao, Y. Land property rights and rural enterprise growth: Evidence from land titling reform in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2022, 157, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.D. Fifty years of local growth management in America. Prog. Plan. 2019, 145, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F. Land development right and collective ownership in China. Post-Communist Econ. 2013, 25, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. The Circulation and Market Development of Rural Land Contractual Management Rights; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 215–254. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Jin, L.; Su, Y.; Wu, K. Identifying the determinants of housing prices in China using spatial regression and the geographical detector technique. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 79, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Huang, J. Impacts of agricultural incentive policies on land rental prices: New evidence from China. Food Policy 2021, 104, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Peiser, R.B. Land supply, pricing and local governments’ land hoarding in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2014, 48, 180–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Wu, D.; Nie, X. Will land development time restriction reduce land price? The perspective of American call options. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Liu, T.; Li, W.; Yang, H. The role of agricultural machinery in improving green grain productivity in China: Towards trans-regional operation and low-carbon practices. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Luan, W.; Wang, X.; Jin, X. Land price, government debt, and land-use efficiency in the coastal cities of China under the constraint of land scarcity. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubacek, K.; van den Bergh, C.J.M. Changing concepts of ‘land’ in economic theory: From single to multi-disciplinary approaches. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 56, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Xi, R.; Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, P.; Che, L. Agricultural land management and rural financial development: Coupling and coordinated relationship and temporal-spatial disparities in China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, L.; Gao, Y.; Ling, Y.; Fan, C.; Hou, D.; Shen, T.; Zhou, W. How did industrial land supply respond to transitions in state strategy? An analysis of prefecture-level cities in China from 2007 to 2016. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, J.; Hunjra, A.I.; Zhao, S.; Bouri, E. How does urban land use efficiency improve resource and environment carrying capacity? Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 91, 101760. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Thill, J.-C.; Peiser, R.B. Land pricing and its impact on land use efficiency in post-land-reform China: A case study of Beijing. Cities 2016, 50, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, F.; Feng, S.; Shen, T. Transfer of development rights, farmland preservation, and economic growth: A case study of Chongqing’s land quotas trading program. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104611. [Google Scholar]

- Mahtta, R.; Fragkias, M.; Güneralp, B.; Mahendra, A.; Reba, M.; Wentz, E.A.; Seto, K.C. Urban land expansion: The role of population and economic growth for 300+ cities. npj Urban Sustain. 2022, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Wang, C.; Yan, Y. Identification of conflict and its evolution between land use and land suitability during urban expansion: A case of Guangzhou, China. Ecol. Front. 2024, 44, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Qi, Y. Construction land expansion and cultivated land protection in urbanizing China: Insights from national land surveys, 1996–2006. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Lin, G.C. Placing China’s land marketization: The state, market, and the changing geography of land use in Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P. Trade-offs between environment and livelihoods: Bridging the global land use and food security discussions. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 16, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Zhao, N. Land ownership and the likelihood of land development at the urban fringe: The case of Shenzhen, China. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, P.; Zhang, S. Role of homestead system reform in rural common prosperity. Finance Res. Lett. 2024, 69, 106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. The Structure of Chinese Urban Land Prices: Estimates from Benchmark Land Price Data. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2009, 39, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Sant’anna, P.H.; Bilinski, A.; Poe, J. What’s trending in difference-in-differences? A synthesis of the recent econometrics literature. J. Econ. 2023, 235, 2218–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascari, G.; Beck-Friis, P.; Florio, A.; Gobbi, A. Fiscal foresight and the effects of government spending: It’s all in the monetary-fiscal mix. J. Monetary Econ. 2023, 134, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Liu, Z. Higher education development, technological innovation and industrial structure upgrade. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).