Nonlinear and Spatially Varying Impacts of Natural and Socioeconomic Factors on Multidimensional Human Health: A Geographically Weighted Machine Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Quantifying Multidimensional Human Health

2.3. Selection of Influencing Factors

2.4. Analyzing Influencing Factors of Human Health

2.4.1. Model Selection

2.4.2. Model Interpretation with SHAP

3. Results

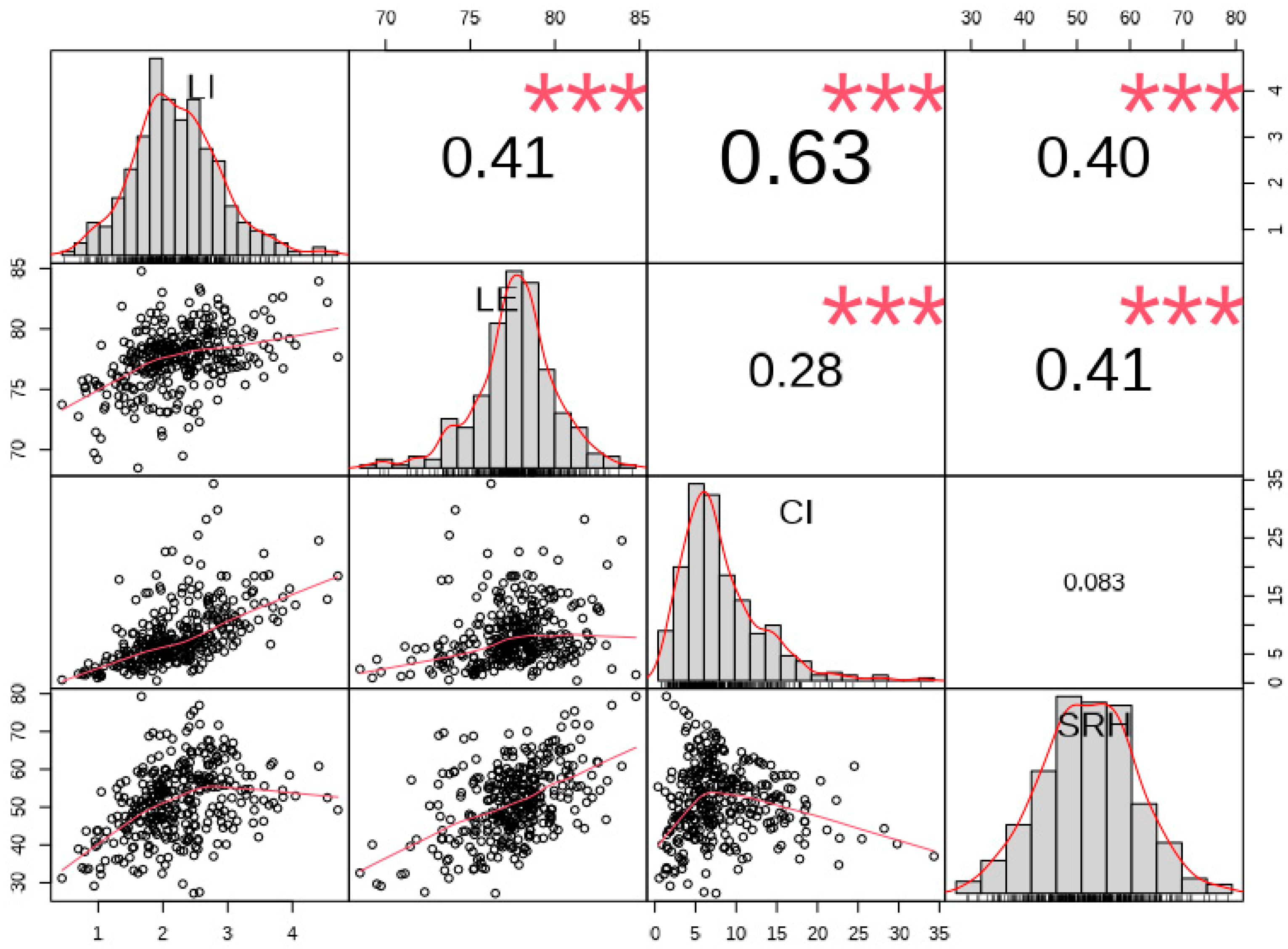

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Multidimensional Human Health

3.2. Model Comparison

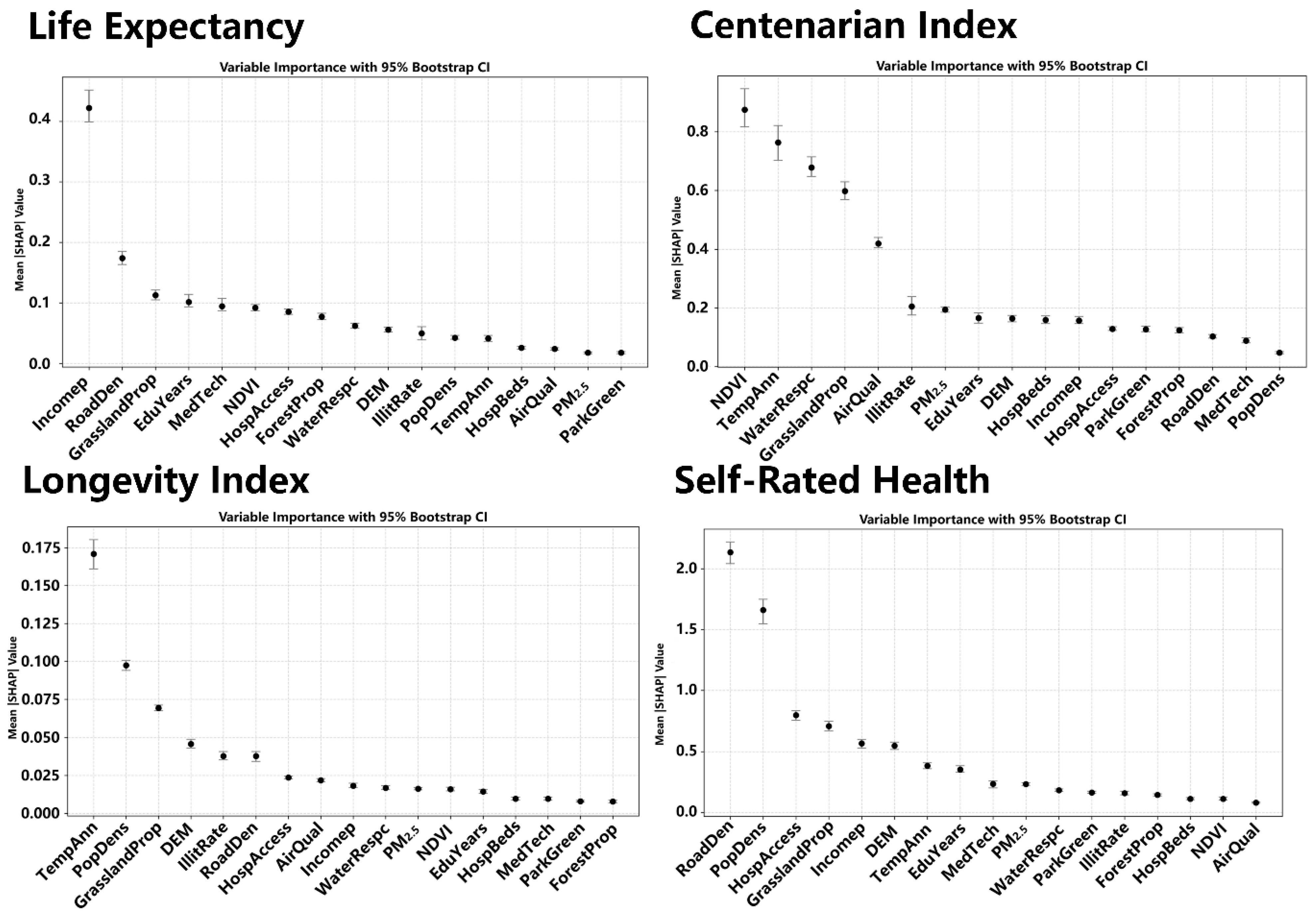

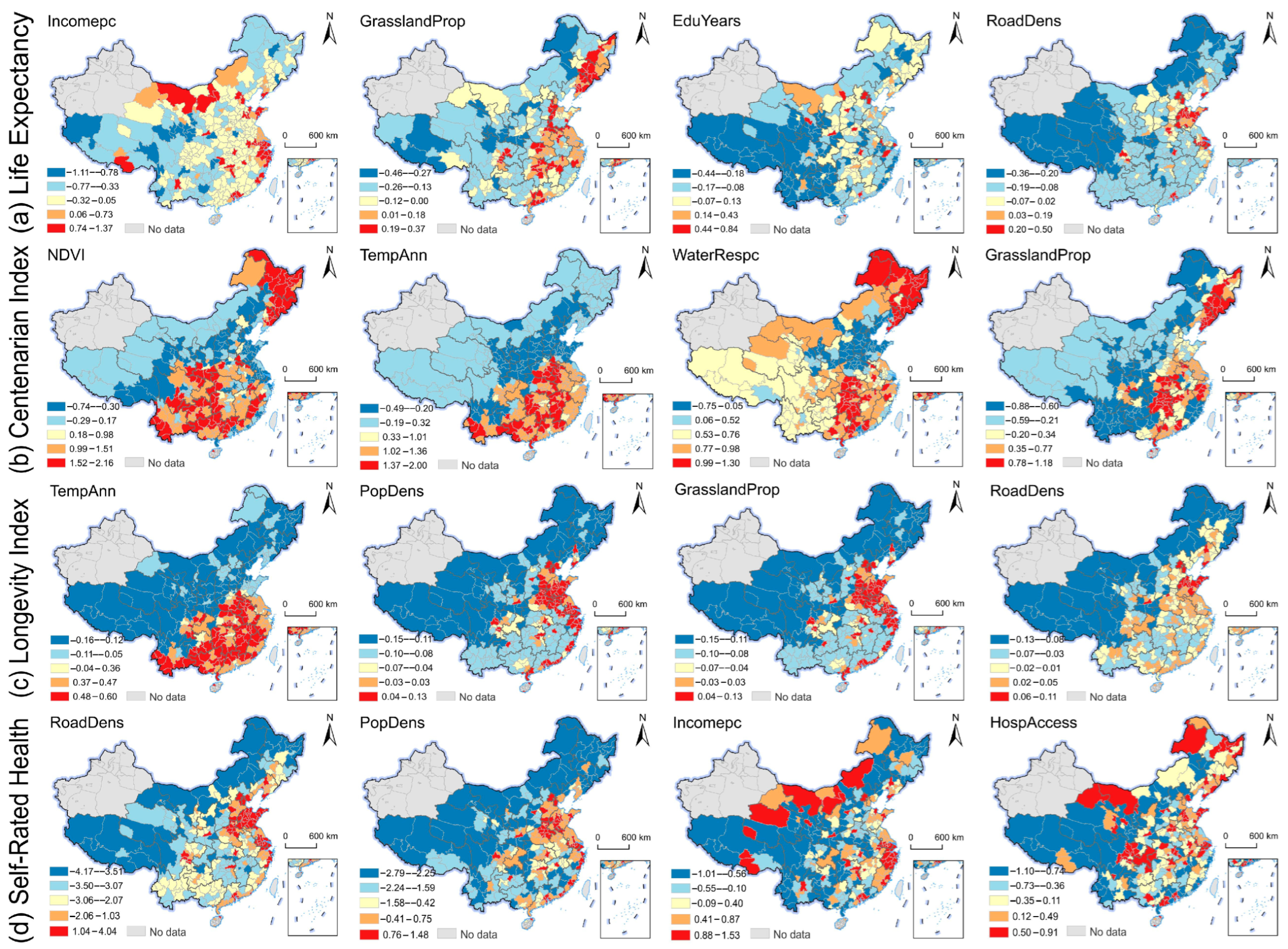

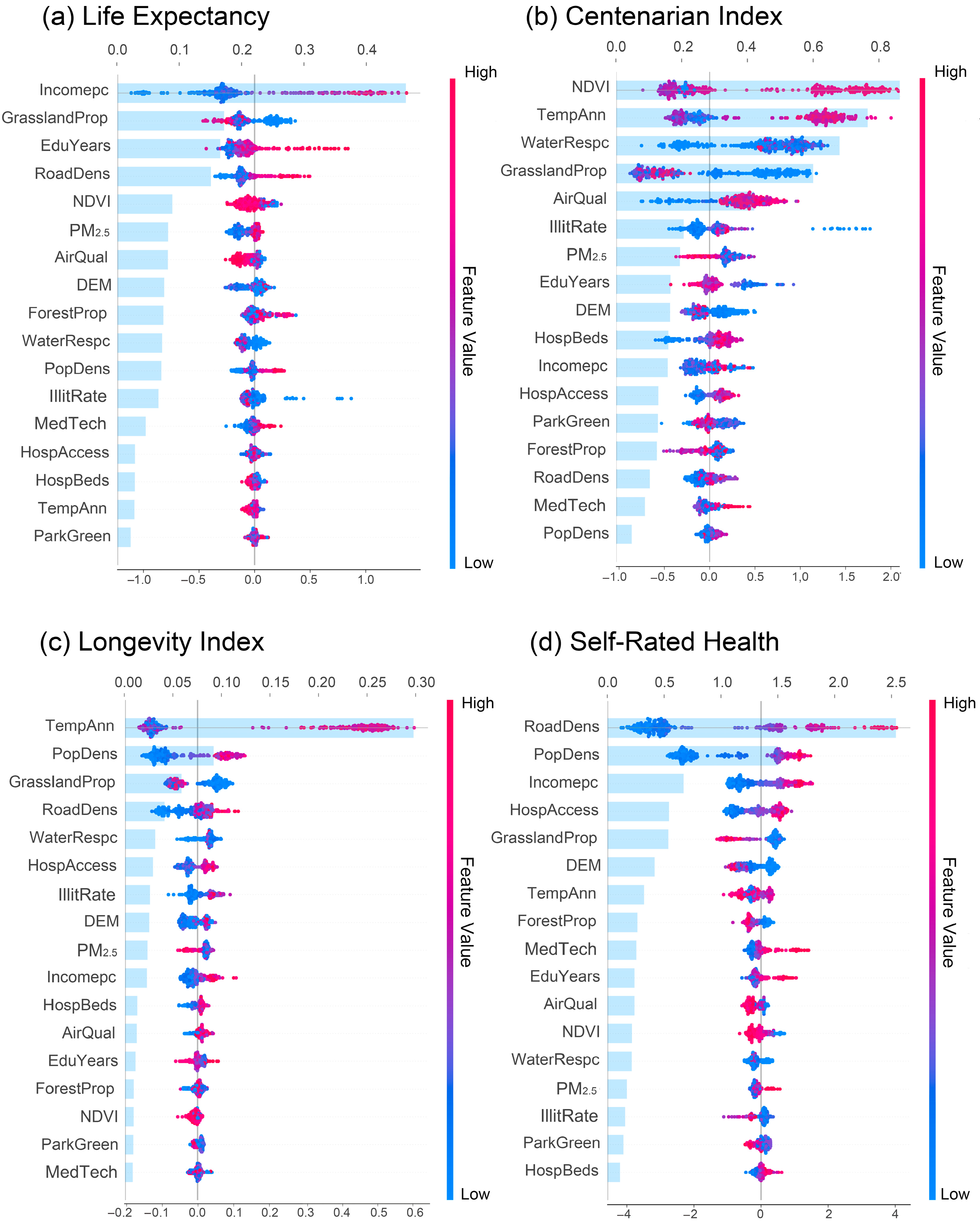

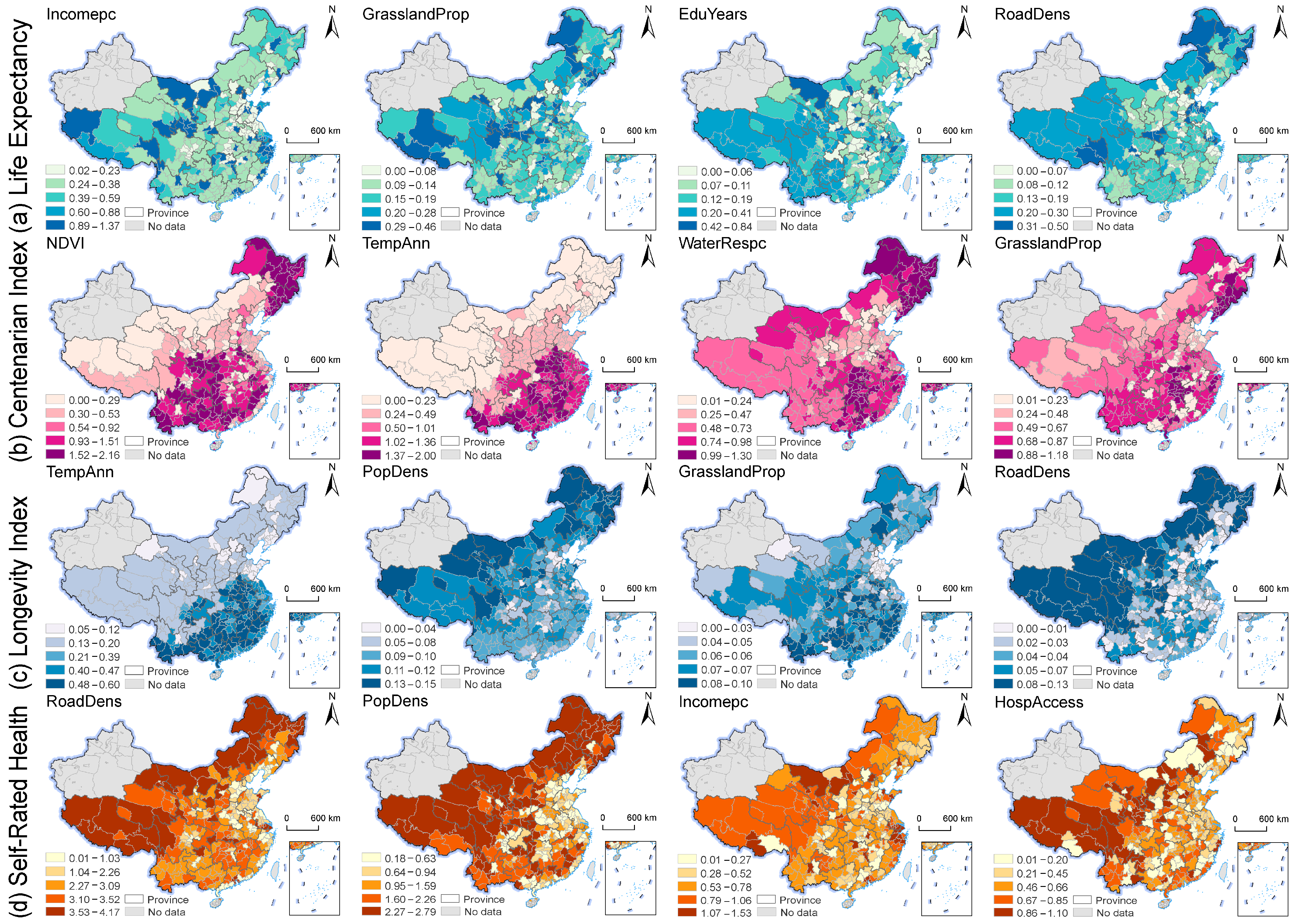

3.3. The Global and Local Dominant Influencing Factors for Multidimensional Human Health

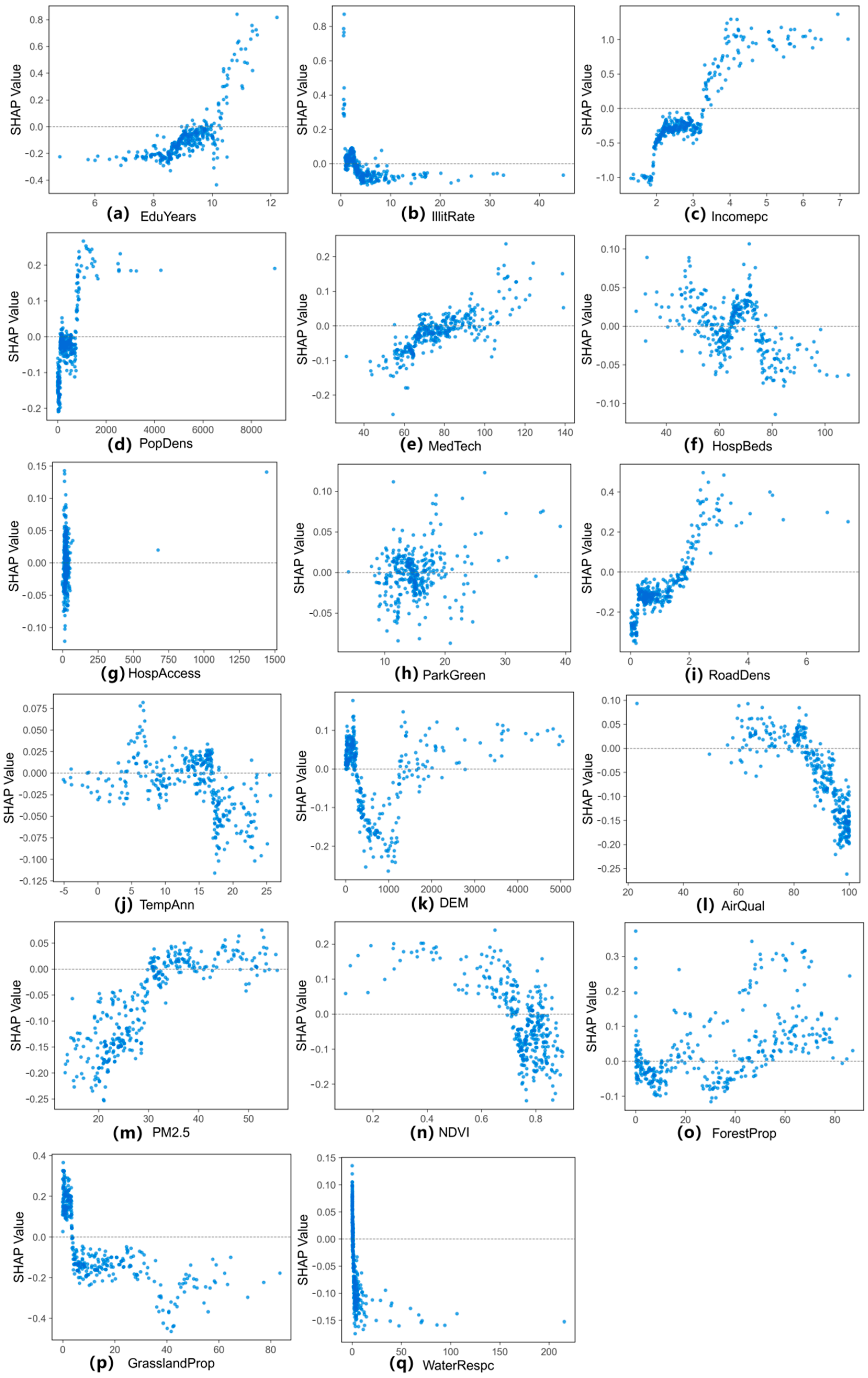

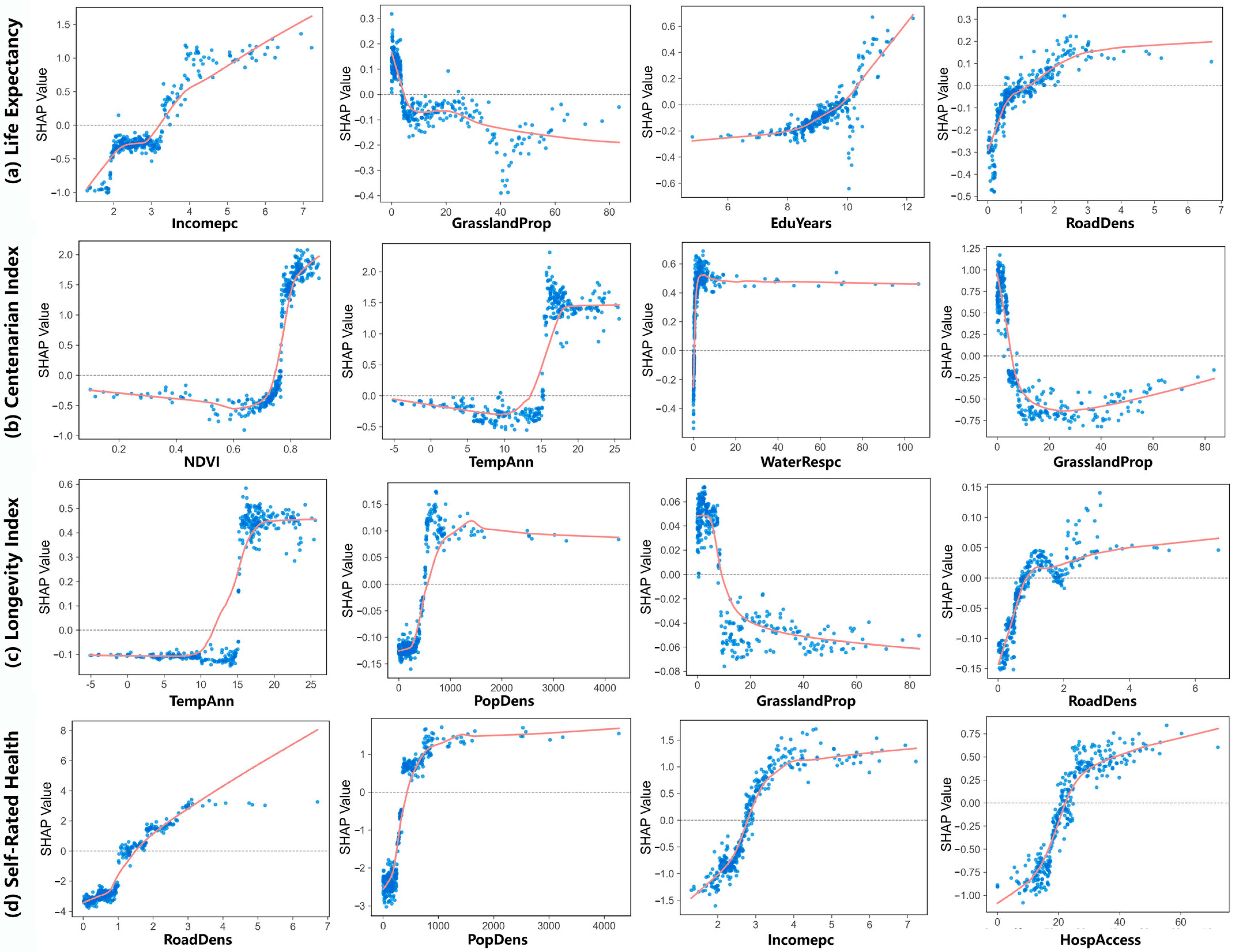

3.4. Nonlinear Effects on Multidimensional Human Health

4. Discussion

4.1. What Are the Major Influencing Factors for Multidimensional Human Health?

4.2. Do Natural and Socioeconomic Determinants Exert Nonlinear Influences on Multidimensional Human Health?

4.3. Implications for Policy Management

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Characteristics | Variables | Definition | Unit | Mean | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human health | Objective health | Life Expectancy | The average survival time of a specific population with the same age in the future based on specific mortality level | Year | 77.53 | China Population Census Yearbook 2020 |

| Centenarian Index | Centenarians per 100,000 inhabitants | Persons/105 population | 8.18 | |||

| Longevity Index | The ratio between the population above 90 years to those above 65 | % | 2.23 | |||

| Subjective health | Self-Rated Health | The percentage of surveyed elderly individuals who rated their own health status as “healthy” | % | 51.44 | ||

| Socio- economic factors | Education | EduYears | Average years of schooling | Year | 9.14 | China Population Census Yearbook 2020 |

| IllitRate | Illiteracy rate | % | 4.60 | |||

| Economy | Incomepc | Per capita disposable income of residents | 104 CNY | 2.95 | Statistical Yearbook and Bulletin | |

| GDPpc | Per capita GDP | 104 CNY | 6.15 | |||

| Population | PopDens | Population density | Persons/km2 | 451.04 | China Population Census Yearbook 2020 | |

| Healthcare | MedTech | Number of medical technical personnel per 10,000 persons | /104 population | 77.19 | Statistical Yearbook and Bulletin | |

| HospBeds | Number of hospital beds per 10,000 persons | /104 population | 65.68 | |||

| HospAccess | Hospital accessibility | - | 29.82 | [36] | ||

| Infrastructure | ParkGreen | Per capita green area of parks | m2/person | 15.28 | China City Statistical Yearbook | |

| RoadDens | Density of roads | km/km2 | 1.10 | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform | ||

| Natural factors | Geographical condition | TempAnn | Annual average temperature | °C | 14.1 | [37,38,39,40,41] |

| HumidAnn | Annual average relative humidity | % | 72.03 | [42] | ||

| PrecAnn | Annual Average Precipitation | mm | 103.16 | [38,39,43] | ||

| Slope | Slope | ° | 5.86 | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform | ||

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model | m | 759.39 | |||

| Environment quality | AirQual | Proportion of days with good air quality during a year | % | 87.56 | Statistical Yearbook and Bulletin | |

| PM2.5 | Annual PM2.5 | μg/m3 | 30.23 | [44,45,46] | ||

| NPP | Net primary productivity | gC/m2 | 589.28 | [47] | ||

| NDVI | Annual Maximum NDVI | - | 0.73 | [48,49] | ||

| Resource supply | FarmlandProp | Farmland proportion | % | 36.38 | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform | |

| ForestProp | Forest proportion | % | 32.55 | |||

| GrasslandProp | Grassland proportion | % | 13.98 | |||

| WaterRespc | Per capita availability of water resources | 103 m3/person | 5.48 | China City Statistical Yearbook |

| Dependent Variables | Bandwidth | N_Estimators | Max_Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longevity Index | 70 | 100 | 9 |

| Life Expectancy | 120 | 100 | 5 |

| Centenarian Index | 70 | 100 | 5 |

| Self-Rated Health | 80 | 100 | 5 |

| Province | Life Expectancy (Years) | Centenarian Index (Persons/ 105 Population) | Longevity Index (%) | Self-Rated Health (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 82.49 | 12.76 | 2.85 | 62.05 |

| Tianjin | 81.30 | 0.39 | 1.91 | 55.37 |

| Hebei | 77.89 | 5.86 | 1.86 | 51.80 |

| Shanxi | 77.70 | 4.40 | 1.84 | 45.47 |

| Inner Mongolia | 77.57 | 9.07 | 1.82 | 44.99 |

| Liaoning | 78.53 | 12.78 | 2.25 | 52.54 |

| Jilin | 78.55 | 10.99 | 2.14 | 43.85 |

| Heilongjiang | 77.43 | 21.83 | 2.18 | 42.72 |

| Shanghai | 82.55 | 13.05 | 3.70 | 61.80 |

| Jiangsu | 79.04 | 9.48 | 2.68 | 60.77 |

| Zhejiang | 80.06 | 5.49 | 2.73 | 64.16 |

| Anhui | 77.82 | 8.05 | 2.42 | 50.40 |

| Fujian | 78.27 | 7.60 | 2.84 | 62.64 |

| Jiangxi | 77.62 | 5.33 | 2.18 | 60.81 |

| Shandong | 79.30 | 7.93 | 2.44 | 58.79 |

| Henan | 77.70 | 9.13 | 2.30 | 56.11 |

| Hubei | 77.62 | 7.30 | 1.76 | 48.42 |

| Hunan | 77.86 | 5.24 | 2.24 | 46.11 |

| Guangdong | 78.89 | 8.95 | 3.20 | 59.08 |

| Guangxi | 78.40 | 14.62 | 3.17 | 51.70 |

| Hainan | 77.91 | 27.45 | 4.21 | 47.34 |

| Chongqing | 78.56 | 7.33 | 2.35 | 59.76 |

| Sichuan | 77.46 | 9.80 | 2.37 | 47.16 |

| Guizhou | 74.99 | 6.68 | 1.81 | 64.45 |

| Yunnan | 74.42 | 3.49 | 2.00 | 52.63 |

| Tibet | 71.84 | 3.92 | 1.76 | 34.28 |

| Shaanxi | 77.04 | 5.72 | 1.48 | 48.45 |

| Gansu | 75.42 | 2.62 | 1.00 | 40.11 |

| Qinghai | 73.90 | 3.54 | 1.70 | 36.81 |

| Ningxia | 76.02 | 1.97 | 1.23 | 41.77 |

References

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Modranka, E.; Suchecka, J. The determinants of population health spatial disparities. Comp. Econ. Res. Cent. East. Eur. 2014, 17, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khedmati Morasae, E.; Derbyshire, D.W.; Amini, P.; Ebrahimi, T. Social determinants of spatial inequalities in COVID-19 outcomes across England: A multiscale geographically weighted regression analysis. SSM-Popul. Health 2024, 25, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, Y.; Chen, B.; Liao, C.; Wu, S.; An, J.; Lin, C.; Gong, P.; Chen, B.; Wei, H.; Xu, B. Inequality in infrastructure access and its association with health disparities. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, 9, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.-L.; Chen, H.-Y.; Xie, Y.-T.; Zhou, G.-L.; Yang, K.-Z.; Huang, H.-J.; Jiang, J.-C.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Wang, L.; Yan, K.; et al. Green spaces and preventable disease and economic burdens in China from 2000 to 2020: A health impact assessment study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 261, 105393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Buerkert, A.; Hoffmann, E.M.; Schlecht, E.; von Cramon-Taubadel, S.; Tscharntke, T. Implications of agricultural transitions and urbanization for ecosystem services. Nature 2014, 515, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fang, X.; Wu, J. How does the local-scale relationship between ecosystem services and human wellbeing vary across broad regions? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Kong, S.; Du, M. The effect of clean heating policy on individual health: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2025, 89, 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Han, H.; Yang, C. Nonlinear relationships and spatial heterogeneity between geographical environment and mental health among middle-aged and older adults in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 127, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazucha, M.J.; Lefohn, A.S. Nonlinearity in human health response to ozone: Experimental laboratory considerations. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 4559–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, D.N.; Goudarzi, G.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Asumadu-Sakyi, A.B.; Fehresti-Sani, M. Long-term effects of outdoor air pollution on mortality and morbidity–prediction using nonlinear autoregressive and artificial neural networks models. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.A.; Green, T.L.; Chapman, A. The Causal Effect of Increasing Area-Level Income on Birth Outcomes and Pregnancy-Related Health: Estimates from the Marcellus Shale Boom Economy. Demography 2024, 61, 2107–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, S.; Kwan, M.-P. A comparative analysis of the impacts of objective versus subjective neighborhood environment on physical, mental, and social health. Health Place 2019, 59, 102170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Luo, L.; Xu, P.; Wang, P. How does social development influence life expectancy? A geographically weighted regression analysis in China. Public Health 2018, 163, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.F.; Ren, F.; Ma, X.Y.; Zhang, H.W.; Xu, W.X.; Jia, P. Explaining the longevity characteristics in China from a geographical perspective: A multi-scale geographically weighted regression analysis. Geospat. Health 2021, 16, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhuo, C.; Yang, F. Spatial pattern evolution of the health level of China’s older adults and its influencing factors from 2010 to 2020. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 3072–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.L.; Yu, H.C.; Lu, Y. Spatial-scale dependent risk factors of heat-related mortality: A multiscale geographically weighted regression analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B.; Wu, J. Spatial heterogeneity of the associations of economic and health care factors with infant mortality in China using geographically weighted regression and spatial clustering. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Ma, W.; Vatsa, P.; Zheng, H. Clean energy use and subjective and objective health outcomes in rural China. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, A.K.D.J.; Migot-Nabias, F.; Zidi, N. Empirical Analysis of Health Assessment Objective and Subjective Methods on the Determinants of Health. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 796937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baji, P.; Bíró, A. Adaptation or recovery after health shocks? Evidence using subjective and objective health measures. Health Econ. 2018, 27, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.-H.; Lee, C.-Y. Subjective and objective health according to the characteristics of older adults: Using data from a national survey of older Koreans. Medicine 2024, 103, e40633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Lei, M.; Wang, S. Spatial heterogeneity of human lifespan in relation to living environment and socio-economic polarization: A case study in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 40567–40584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.; Herrera, D.; Mireku, F.; Barner, K.; Kokkinakis, A.; Dao, H.; Webber, A.; Merida, A.D.; Gallo, T.; Pierobon, M. Geographical Variation in Social Determinants of Female Breast Cancer Mortality Across US Counties. JAMA 2023, 6, e2333618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, B.G.; Li, Y.H.; Li, H.R.; Zhang, F.Y.; Rosenberg, M.; Yang, L.S.; Huang, J.X.; Krafft, T.; Wang, W.Y. A study of air pollutants influencing life expectancy and longevity from spatial perspective in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 487, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Du, M. How digital finance shapes residents’ health: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 87, 102246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.R.; Liu, W.L. Does air pollution affect public health and health inequality? Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grekousis, G.; Feng, Z.; Marakakis, I.; Lu, Y.; Wang, R. Ranking the importance of demographic, socioeconomic, and underlying health factors on US COVID-19 deaths: A geographical random forest approach. Health Place 2022, 74, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wu, J. Space cannot substitute for time in the study of the ecosystem services-human wellbeing relationship. Geogr. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Zhao, H.; Yue, L.; Guo, J.; Cui, Q.; Tang, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhao, P. Attribution analysis of urban social resilience differences under rainstorm disaster impact: Insights from interpretable spatial machine learning framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 118, 106029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georganos, S.; Grippa, T.; Gadiaga, A.N.; Linard, C.; Lennert, M.; Vanhuysse, S.; Mboga, N.; Wolff, E.; Kalogirou, S. Geographical random forests: A spatial extension of the random forest algorithm to address spatial heterogeneity in remote sensing and population modelling. Geocarto Int. 2021, 36, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Li, X.; Wang, R.; Guo, Z.; Dong, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Q. Interpretable spatial machine learning insights into urban sanitation challenges: A case study of human feces distribution in San Francisco. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 113, 105695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Ye, P. National-scale 1-km maps of hospital travel time and hospital accessibility in China. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S. 1-km Monthly Mean Temperature Dataset for China (1901–2023); National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Gang, C.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y. Assessment of climate change trends over the Loess Plateau in China from 1901 to 2100. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 2250–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Wen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ren, J. Spatiotemporal change and trend analysis of potential evapotranspiration over the Loess Plateau of China during 2011–2100. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 233, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Peng, S. Spatiotemporal Trends and Attribution of Drought across China from 1901–2100. Sustainability 2020, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Luo, M.; Zhan, W.; Zhao, Y. A First 1 km High-Resolution Atmospheric Moisture Index Collection over China; National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S. 1-km Monthly Precipitation Dataset for China (1901–2024); National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z. ChinaHighPM2.5: High-Resolution and High-Quality Ground-Level PM2.5 Dataset for China (2000–2023); Zenodo: Meyrin, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Lyapustin, A.; Sun, L.; Peng, Y.; Xue, W.; Su, T.; Cribb, M. Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2.5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: Spatiotemporal variations and policy implications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Cribb, M.; Huang, W.; Xue, W.; Sun, L.; Guo, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Lyapustin, A.; et al. Improved 1 km resolution PM2.5 estimates across China using enhanced space-time extremely randomized trees. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 3273–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, S.; Zhao, M. MOD17A3HGF MODIS/Terra Net Primary Production Gap-Filled Yearly L4 Global 500 m SIN Grid V006. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod17a3hgf-006 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Dong, J.; Zhou, Y.; You, N. A 30 m Annual Maximum NDVI Dataset in China from 2000 to 2020; National Ecosystem Science Data Center: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dong, J.; Xiao, X.; Dai, J.; Wu, C.; Xia, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. Divergent shifts in peak photosynthesis timing of temperate and alpine grasslands in China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 233, 111395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Li, J.H.; Yu, L.S.; Yu, D.; Hou, Z.L. Analysis of the Life expectancy and the impact of diseases. Popul. J. 2018, 40, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEA. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; de Vries, S.; Assmuth, T.; Dick, J.; Hermans, T.; Hertel, O.; Jensen, A.; Jones, L.; Kabisch, S.; Lanki, T. Research challenges for cultural ecosystem services and public health in (peri-) urban environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wu, J. Ecosystem services-human wellbeing relationships vary with spatial scales and indicators: The case of China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 172, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayentin, L.; El Adlouni, S.; Ouarda, T.B.; Gosselin, P.; Doyon, B.; Chebana, F. Spatial variability of climate effects on ischemic heart disease hospitalization rates for the period 1989–2006 in Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robine, J.-M.; Herrmann, F.R.; Arai, Y.; Willcox, D.C.; Gondo, Y.; Hirose, N.; Suzuki, M.; Saito, Y. Exploring the impact of climate on human longevity. Exp. Gerontol. 2012, 47, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Du, M.; Chen, Z. Environmental pollution and socioeconomic health inequality: Evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 95, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Martin, F.; Martin-Lopez, B.; Garcia-Llorente, M.; Aguado, M.; Benayas, J.; Montes, C. Unraveling the Relationships between Ecosystems and Human Wellbeing in Spain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duku, E.; Mattah, P.A.D.; Angnuureng, D.B. Assessment of wetland ecosystem services and human wellbeing nexus in sub-Saharan Africa: Empirical evidence from a socio-ecological landscape of Ghana. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2022, 15, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S.H. Contributions of ecosystem services to human well-being in Puerto Rico. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.M.; Nath, I.; Capon, A.; Hasan, N.; Jaron, D. Health and wellbeing in the changing urban environment: Complex challenges, scientific responses, and the way forward. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Wang, T.; Wu, J.; Wang, L. Nonlinear Associations of the Built Environment with Cycling Frequency among Older Adults in Zhongshan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W. Environmental factors for outdoor jogging in Beijing: Insights from using explainable spatial machine learning and massive trajectory data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 243, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Sanchez-Castillo, M.; Chica-Olmo, M.; Chica-Rivas, M. Machine learning predictive models for mineral prospectivity: An evaluation of neural networks, random forest, regression trees and support vector machines. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, Q. Analysis of China’s Industrial Green Development Efficiency and Driving Factors: Research Based on MGWR. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M.E. Geographically Weighted Regression: A Method for Exploring Spatial Nonstationarity. Geogr. Anal. 1996, 28, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, C.; Yang, X.; Kwan, M.-P.; Zhang, K. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity analysis of air quality in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Ye, Z.; Wu, H. Nonlinear effects of built environment on intermodal transit trips considering spatial heterogeneity. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 90, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.I.; Papadopoulos, P.N. Using SHAP Values and Machine Learning to Understand Trends in the Transient Stability Limit. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 1384–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Extracting spatial effects from machine learning model using local interpretation method: An example of SHAP and XGBoost. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 96, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.C.; Zhang, Q.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Lin, J.L.; Bai, X.M. Use of interpretable machine learning for understanding ecosystem service trade-offs and their driving mechanisms in karst peak-cluster depression basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ge, J.; Wang, S.; Dong, C. Optimizing urban green space configurations for enhanced heat island mitigation: A geographically weighted machine learning approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 119, 106087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B.; Luo, K.L.; Liu, Y.L. Spatio-temporal distribution of human lifespan in China. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kyan, A.; Sato, M.; Ushimaru, A.; Minamoto, T.; Harada, K.; Takakura, M.; Kohsaka, R.; Kiyono, M.; Tsurumi, T.; et al. Association between objective and subjective relatedness to nature and human well-being: Key factors for residents and possible measures for inequality in Japan’s megacities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 261, 105377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulle, R.J.; Pellow, D.N. Environmental Justice: Human Health and Environmental Inequalities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacke, J.; Schüle, S.A.; Köckler, H.; Bolte, G. Mapping Environmental Inequalities Relevant for Health for Informing Urban Planning Interventions—A Case Study in the City of Dortmund, Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer-Lindgren, L.; Kendrick, P.; Kelly, Y.O.; Sylte, D.O.; Schmidt, C.; Blacker, B.F.; Daoud, F.; Abdi, A.A.; Baumann, M.; Mouhanna, F.; et al. Life expectancy by county, race, and ethnicity in the USA, 2000–2019: A systematic analysis of health disparities. Lancet 2022, 400, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, L. Global air quality inequality over 2000–2020. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2025, 130, 103112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, T.; Pan, J.; Qin, X. The intergenerational inequality of health in China. China Econ. Rev. 2014, 31, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lin, X.; Ni, R.; Tian, X.; Gao, X. Economic level and human longevity: Spatial and temporal variations and correlation analysis of per capita GDP and longevity indicators in China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 61, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Li, Y.; Hao, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, W. Public health in China: An environmental and socio-economic perspective. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 129, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.; Pabayo, R.; Hwang, J. An evolution of socioeconomic inequalities in self-rated health in Korea: Evidence from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 1998–2018. SSM-Popul. Health 2024, 26, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullati, S.; Rousseaux, E.; Gabadinho, A.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Burton-Jeangros, C. Factors of change and cumulative factors in self-rated health trajectories: A systematic review. Adv. Life Course Res. 2014, 19, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Grekousis, G.; Huang, Y.; Hua, F.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y. Examining the importance of built and natural environment factors in predicting self-rated health in older adults: An extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Yue, L.; Gu, T.; Tang, J.; Wang, Z. Unraveling the factors behind self-reported trapped incidents in the extraordinary urban flood disaster: A case study of Zhengzhou City, China. Cities 2024, 155, 105444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Yu, G.; Xia, T.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Wei, P.; Long, B.; Lei, M.; Wei, X.; Tang, X.; et al. Spatio-Temporal Variation of Longevity Clusters and the Influence of Social Development Level on Lifespan in a Chinese Longevous Area (1982–2010). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Y. Effects of environmental factors on the longevous people in China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 53, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, B. Considerations on temperature, longevity and aging. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 1626–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, A.E.; Flouris, A.D. Caloric restriction and longevity: Effects of reduced body temperature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Alirzayeva, H.; Koyuncu, S.; Rueber, A.; Noormohammadi, A.; Vilchez, D. Cold temperature extends longevity and prevents disease-related protein aggregation through PA28γ-induced proteasomes. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnolfi, S.U.; Noferi, I.; Petruzzi, E.; Pinzani, P.; Malentacchi, F.; Pazzagli, M.; Antonini, F.M.; Marchionni, N. Centenarians in Tuscany: The role of the environmental factors. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 48, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Housing and Health Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X. State-led regional development strategy and multidimensional health poverty of the residents: Evidence from the China’s great western development program. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2025, 57, 101494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Sen, S.; Zick, Y. Algorithmic Transparency via Quantitative Input Influence: Theory and Experiments with Learning Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 598–617. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, M.; Najmi, A. The many Shapley values for model explanation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtually, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 9269–9278. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Models | R2 | RMSE | MAE | OOB RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Expectancy | OLS | 0.54 | 1.68 | 1.25 | / |

| GWR | 0.62 | 1.53 | 1.16 | / | |

| RF | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 1.85 | |

| GWRF | 0.95 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 1.58 | |

| Centenarian Index | OLS | 0.47 | 3.79 | 2.94 | / |

| GWR | 0.76 | 2.55 | 1.89 | / | |

| RF | 0.94 | 1.23 | 0.89 | 3.47 | |

| GWRF | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 3.04 | |

| Longevity Index | OLS | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.42 | / |

| GWR | 0.79 | 0.32 | 0.25 | / | |

| RF | 0.94 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.43 | |

| GWRF | 0.97 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.39 | |

| Self-Rated Health | OLS | 0.65 | 5.55 | 4.41 | / |

| GWR | 0.82 | 4.06 | 3.25 | / | |

| RF | 0.96 | 1.97 | 1.54 | 5.28 | |

| GWRF | 0.97 | 1.58 | 1.26 | 5.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, H. Nonlinear and Spatially Varying Impacts of Natural and Socioeconomic Factors on Multidimensional Human Health: A Geographically Weighted Machine Learning Approach. Land 2025, 14, 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122324

Liu Y, He Z, Liu L, Wang H. Nonlinear and Spatially Varying Impacts of Natural and Socioeconomic Factors on Multidimensional Human Health: A Geographically Weighted Machine Learning Approach. Land. 2025; 14(12):2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122324

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yilin, Zegui He, Lumeng Liu, and Hong Wang. 2025. "Nonlinear and Spatially Varying Impacts of Natural and Socioeconomic Factors on Multidimensional Human Health: A Geographically Weighted Machine Learning Approach" Land 14, no. 12: 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122324

APA StyleLiu, Y., He, Z., Liu, L., & Wang, H. (2025). Nonlinear and Spatially Varying Impacts of Natural and Socioeconomic Factors on Multidimensional Human Health: A Geographically Weighted Machine Learning Approach. Land, 14(12), 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122324