1. Introduction

The impacts of climate change are unfolding rapidly, even faster than anticipated [

1], making it imperative to mitigate global emissions by at least 50% by 2050 and achieve carbon neutrality by mid-century [

2]. The reduction in emissions is crucial across all sectors, including LULUCF (Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry), which has become a relevant sector, allowing afforestation and reforestation as greenhouse gas (GHG) offsetting activities [

3]. Although afforestation, reforestation, and sustainable land management practices can sequester significant amounts of carbon, deforestation and land-use changes (e.g., forest land to agricultural land) contribute to emissions, making the sector act both as a sink and source of GHGs.

Worldwide, the LULUCF sector, together with the Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use sector (AFOLU), on average, accounted for 13–21% of total anthropogenic GHG emissions in the period 2010–2019 with an emission rate of +5900 ± 4100 Mt CO

2 eq yr

−1 [

4]. In the EU, the total emissions from all sectors, including both AFOLU and non-AFOLU activities, decreased by 36.1% from 5.4 Gt CO

2 eq in 1990 to 3.4 Gt CO

2 eq in 2020. AFOLU activities were associated with an annual average net source of 153.3 Mt CO

2 eq, derived from annual average agriculture emissions of 445.30 Mt CO

2 eq and an annual average removal from LULUCF of −292 Mt CO

2 eq, which was mainly driven by the forestland category [

5].

Agroforestry (AF), as part of the cropland category under the LULUCF sector [

6], has been recognised as a system approach for emission reduction to ameliorate the impacts of climate change through the “Clean Development Mechanism” of the Kyoto Protocol. It not only offers a promising opportunity for enhancing carbon sequestration while maintaining sustainable agricultural productivity but also promotes biodiversity, mitigates soil erosion, and generates income [

7]. Agroforestry is a complex land-management system that optimises the benefits from the biological interactions created when trees and/or shrubs are deliberately combined with crops and/or livestock [

8]. The EU Commission defines AF as “a form of land use system where trees are grown in combination with agriculture and/or livestock on the same land” [

9]. There are several types of AF in Europe, such as silvopastoral, silvoarable, intercropped permanent crops, grazed permanent crops, and kitchen gardens [

10,

11]. Silvopastoral systems are systems where trees are integrated with grazing animals, while silvoarable is the integration of trees with arable crops [

12].

In the context of European agriculture, the high ecological and social value of AF was recognised initially in 2005 at the European Union (EU) level [

13]. AF is supported by the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) across its various reforms and financial periods since 2007 [

7]. In the current period (2021–2027), EU Member States were required to propose interventions to achieve the CAP’s objectives in the form of strategic plans. AF is considered one of the interventions [

14]. Moreover, in the policy framework, AF is supported by the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs). At the EU level, the European Green Deal promotes the achievement of SDGs, stating strategic plans within the CAP should lead to the use of sustainable practices, including AF. The Farm to Fork Strategy and the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 also support the uptake of AF due to its potential to provide multiple benefits for biodiversity, people, and climate [

13].

From a carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation perspective, the integration of trees into agricultural systems makes the total aboveground carbon usually higher than the equivalent agricultural land without trees, and the trees may increase the carbon sequestration in the soil [

15]. Moreover, the presence of trees on agricultural land, in comparison with forest ecosystems, results in less competition from other trees over the growing resources, leading to much faster-growing biomass both above and below the ground [

15,

16,

17]. Thus, agroforestry systems could play a positive role in contributing to reducing GHG emissions and providing renewable energy sources, as well as mitigating soil erosion and improving soil organic carbon content [

18].

At the European level, numerous studies have estimated the extent and spatial distribution of AF [

7,

11,

19,

20] and quantified its carbon sequestration potential [

15]. Using the Corine land cover database, the area of AF was quantified to be around 3.3 million hectares (Mha), mainly found in Spain, Portugal, and Italy [

21]. Other studies suggested a much larger area of at least 10.6 Mha [

21]. Den Herder et al. [

20] used the Land Use/Cover Area Frame Survey (LUCAS) to estimate agroforestry areas in the EU 27 Member States (EU27) region by identifying certain combinations of primary and secondary land cover and/or land management classes. They estimated AF areas to be around 15.4 Mha, which is equivalent to about 3.6% of the EU27 territorial area and 8.8% of the utilised agricultural area (UAA). A more recent study using LUCAS data from 2018 estimated the total area of agroforestry in the EU28 to be approximately 11.4 Mha, equivalent to 6.4% of UAA [

11]. A recent study determining AF areas in EU28, including small woody features, suggested an area of 57.6 Mha, 44.4 Mha, or 77% of which are small woody features agroforestry [

22]. Regarding biomass carbon and soil organic carbon sequestration, Aertsens et al. [

15] stated that agricultural land, including AF in the EU27, has the potential to remove up to 1500 Mt of CO

2 eq annually.

Despite the growing recognition of AF as a land use management system in mitigating GHG emissions, a comprehensive assessment of their net carbon sequestration potentials at the European scale, highlighting the contributions of individual countries, is still relatively limited. According to IPCC guidelines, all parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) report their inventories of the LULUCF sector using the six broad definitions, including AF contribution under the cropland category. However, the contribution of AF is not clear in the current reports submitted to UNFCCC because it is either not taken into account or is considered as part of the cropland category, making it difficult to distinguish its share in emissions and removals, as they seem to have a different emission/removal rate than those subcategories under LULUCF [

23]. Hence, this study aims to quantify the distribution of silvopastoral and silvorable systems across Europe and their carbon sequestration contribution by estimating the potential net carbon removals and emissions. Furthermore, it includes estimations of carbon removals and emissions for three different scenarios of AF introduction in target areas. The present study is limited to silvopastoral and silvoarable systems because no reliable carbon removal data are available for other AF systems.

The main novelty of this article lies in its spatially explicit assessment of the extent, distribution, and climate mitigation potential of silvopastoral and silvoarable agroforestry systems across the EU27, UK, and Switzerland, with a particular focus on the Atlantic, Continental, and Mediterranean biogeographical regions. Unlike previous studies, such as those using the LUCAS dataset [

7,

11,

19,

20], which rely on point-based sampling and extrapolation, the present research employs comprehensive spatial mapping using high-resolution land cover datasets and Copernicus layers to directly quantify the actual areas occupied by these systems, thereby improving the accuracy and detail of agroforestry estimates across landscapes. Additionally, the article distinguishes itself by integrating empirically derived carbon sequestration rates that are specific to bioregions and tree genera, as well as systematically quantifying the associated greenhouse gas emissions from diverse management activities. Furthermore, the paper models three policy-relevant land use change scenarios for expanded agroforestry adoption and evaluates their implications for achieving EU climate and tree planting targets, offering actionable insight for climate and land use policy beyond what has been addressed in the prior literature.

2. Materials and Methods

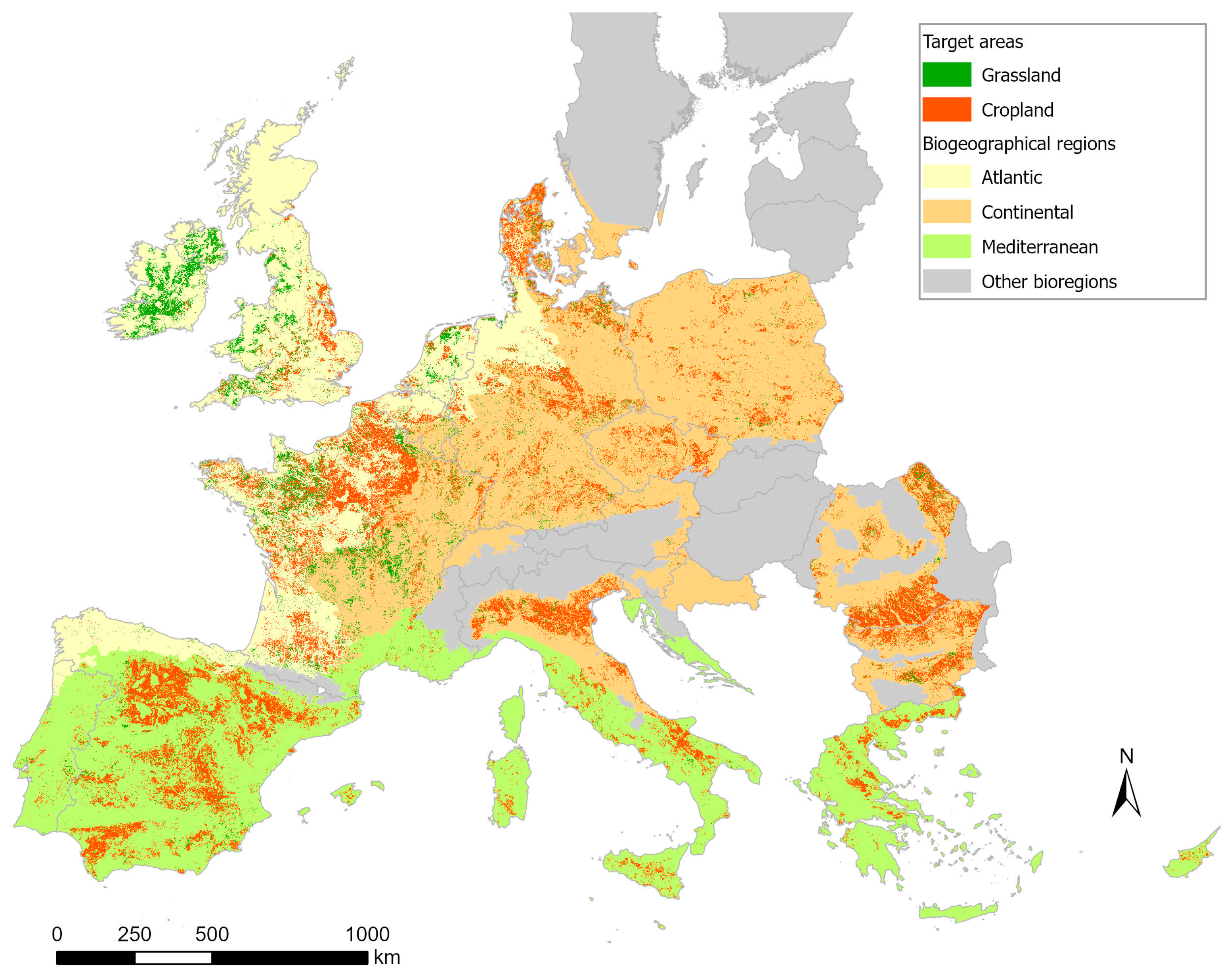

This study was conducted across the 27 Member States of the European Union (EU27), the United Kingdom (UK), and Switzerland (CH), with a specific focus on the Atlantic, Continental, and Mediterranean biogeographical regions (collectively referred to as EU3B) (

Figure 1). These regions account for approximately 68% of the total area of the EU27, UK, and CH. The focus on EU3B is due to the lack of reliable data on the carbon storage potential of AF systems in other biogeographical zones. For reference, see

Table A1 in

Appendix A for biogeographical region coverage per country.

The analysis followed a structured approach consisting of four main steps (

Figure 2): (1) identifying silvopastoral and silvoarable areas within the EU27, UK, and CH, focusing on the Atlantic, Continental, and Mediterranean biogeographical regions; (2) compiling biomass carbon data and emission factors associated with various management practices; (3) estimating greenhouse gas emissions and carbon removals from the identified silvopastoral and silvoarable areas; and (4) simulating land use change scenarios, defining target areas for the introduction of these agroforestry systems to evaluate their potential contribution to emission reductions within the LULUCF sector. This comprehensive methodology resulted in the creation of an inventory of emissions and removals for silvopastoral and silvoarable systems, an assessment of their potential impact on the LULUCF inventory, and the proposal of policy-relevant land use change scenarios. Furthermore, all spatial and geostatistical analyses were conducted using ArcGIS Pro (v3.1.0).

2.1. Identification of Silvopastoral and Silvoarable Systems

Firstly, agricultural areas were identified using the 2018 Land-Use-based Integrated Sustainability Assessment (LUISA) land cover map [

24], an enhanced and refined version of the 2018 Corine Land Cover map [

25], to estimate silvopastoral and silvoarable areas. Silvopastoral systems were defined as the integration of trees with pastures and livestock production, while silvoarable systems were defined as widely spaced trees combined with annual or perennial crops on the same land [

12].

The agricultural land cover classes selected for this analysis included temporary crops (non-irrigated arable land, permanently irrigated arable land, and rice fields), grasslands (pastures and natural grasslands), and heterogeneous agricultural areas (complex cultivation patterns, land principally occupied by agriculture, annual crops associated with permanent crops, and agroforestry). Notably, all areas identified in the land cover map as “annual crops associated with permanent crops” (combination of temporary and permanent crops) and “agroforestry” (silvopastoral systems known as Dehesas/Montados in the southwestern Iberian Peninsula and some areas in Sardinia, Italy) were considered agroforestry.

Secondly, tree cover density (TCD) [

26] was estimated across the entire agricultural area within the study region. These areas were then categorised into two groups: those with 1–10% TCD and those with more than 10% TCD. This classification allowed for a clearer distinction between areas with varying tree densities, while still recognising the ecological importance of both. Agricultural areas with more than 1% TCD were considered either silvopastoral or silvoarable, depending on the association of temporary or permanent crops, pastures, and/or livestock. The 1% threshold was selected to avoid excluding areas with sparse tree cover that are still widely recognised as agroforestry [

11,

19].

Thirdly, small woody features (SWF) [

27], such as hedgerows, riparian buffer strips, and windbreaks, were extracted from silvopastoral and silvoarable areas, as these woody elements represent other agroforestry typologies that are not considered in this study. Therefore, areas with more than 1% of small woody features in temporary crops, permanent crops, pastures, and heterogeneous agricultural classes were excluded.

Subsequently, a boundary cleaning algorithm was then applied to the TCD layer to smooth transitions between zones. This algorithm used mathematical morphology techniques, including dilation and erosion, to refine patch boundaries [

28]. Each pixel was evaluated based on its orthogonal and diagonal neighbours, prioritising pixels with more than 10% TCD over those with 1–10%. This process helped consolidate patches and eliminate isolated pixels with lower landscape relevance.

Finally, pixels within non-irrigated arable land, irrigated arable land, rice fields, and land principally occupied by agriculture were reclassified as silvoarable, based on the presence of temporary crops and TCD above 1%. Similarly, pixels within pastures and natural grasslands were reclassified as silvopastoral, due to the combination of pastureland, tree cover above 1%, and livestock presence. Moreover, the class “agroforestry” was included in the silvopastoral category because of the presence of livestock, trees, and pastures found in Dehesas/Montados systems in the Iberian Peninsula.

2.2. Carbon Inventory for Silvopastoral and Silvoarable Systems

2.2.1. Estimation of Biomass Carbon Removals by Agroforestry Systems

The EURAF carbon framing dataset [

29] was used to quantify the carbon sequestration rates of the selected AF. The dataset includes empirically derived values for tree biomass carbon removal for various tree species used in silvopastoral and silvoarable practices. Only data relevant to the selected bioregions, EU3B, were extracted from the dataset and augmented with carbon removal rates for ash and poplar trees recorded from a long-term experimental trial in the UK. Subsequently, the established default values from the 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines were utilised to compute belowground biomass carbon (BGC) sequestration rates, and an assumption of 25% of belowground to aboveground (AGC) was considered for all regions [

30].

2.2.2. Estimation of Emissions from Silvopastoral and Silvoarable Systems

Data from two long-term experimental AF stations (

Figure 1) representing two out of three bioregions were used to identify the relevant management activities to estimate GHG emissions. One site is located in the Atlantic region (Loughall experimental station, UK) with cool temperate climate [

31], while the other site is located in the Mediterranean region (Majadas experimental station, Spain), characterised by continental Mediterranean climate with mild winters [

32]. The associated emission factor values were obtained from the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories [

6,

30].

2.2.3. Management Activities and Processes with Potential GHG Emissions

There are a number of activities and processes within silvopastoral and silvoarable systems with the potential of releasing GHGs. Management activities included both pre-farm activities (i.e., production and storage of fertilisers, transportation of production inputs) and on-farm activities and processes (i.e., machinery operations, farm management practices such as thinning and pruning, harvesting, and manure application). The following activities and processes were selected, and emissions were estimated: enteric fermentation [

33], thinning and pruning [

34], fertilisation [

35,

36], and harvesting [

6]. The rationale for selecting these factors is primarily based on the availability of data from the experimental stations and their significant contribution.

2.3. Potential Impacts of Silvopastoral and Silvoarable Systems Emissions on the LULUCF Sector

To examine the impact of the estimated emissions and removals of both systems on the LULUCF sector in the study area, emissions and removals data related to the LULUCF sector submitted through national inventory reports and common reporting formats by EU27 member states to UNFCCC [

37] were used. Afterwards, the mean and changes from the baseline were computed to highlight the impact of these systems on the LULUCF sector inventory.

2.4. The Effect of Land Use Change Scenarios on Carbon Accounting

In this analysis, a spatial dataset generated by Gabourel-Landaverde et al. [

38] was used, which identified target areas to introduce agroforestry systems in the EU27, UK, and CH based on environmental pressures within agricultural areas. The study carried out an analysis of environmental pressures, focusing on 14 indicators related to soil, biodiversity, water, and climate change. These pressure indicators, which included variables such as soil erosion, loss of soil organic matter, nitrogen surplus, and temperature change, were sourced from European and national cartographic datasets. Threshold values were established for each indicator to determine sustainability limits. Agricultural areas showing high concentrations of environmental pressures were selected as agroforestry target areas to improve the delivery of ecosystem services in these regions [

38].

Subsequently, AF target areas located within cropland and grassland regions in EU3B were identified and used to estimate their potential for carbon sequestration. Cropland target areas were considered suitable for the introduction of silvoarable systems, which combine temporary crops with trees. Grassland target areas were deemed appropriate for silvopastoral systems, integrating trees, pasture, and grazing. In this context, three scenarios were developed, reflecting different proportions of silvopastoral and silvoarable target areas, corresponding to increases of 10%, 20%, and 30%. The impact of these scenarios on the EU’s LULUCF inventory was then analysed in terms of emissions reductions resulting from the increased AF area.

3. Results

3.1. Area Distribution of Silvopastoral and Silvoarable Systems

The assessment resulted in a total surface area of silvopastoral and silvoarable areas of 9.2 Mha in 2018 across the EU27, UK, and CH, within the selected bioregions EU3B (

Table 1). Silvopastoral systems constitute the largest area, with 6 Mha, accounting for 65.2% of the total agroforestry area. Silvoarable systems occupied 3.2 Mha, equivalent to 34.8% of the total estimation. For reference, biogeographical region coverage per country is presented in

Table A1 in

Appendix A. For country and bioregion-specific silvopastoral and silvoarable areas, see

Table A2 in

Appendix A.

In terms of the spatial distribution of AF in the three biogeographical regions (

Figure 3), silvopastoral systems were most prevalent in the Mediterranean bioregion, where 70.3% of the SP area was identified, particularly in Spain, Portugal, and Italy. This is followed by the Atlantic bioregion, where 7.1% of the SP area was estimated, with the United Kingdom, France, and Ireland reporting the largest areas, and the Continental bioregion (22.7%), with Germany, Romania, and France also demonstrating relatively high proportions. In contrast, silvoarable systems were common in the Continental bioregion (44.3%), particularly in Poland, Germany, and Romania, followed by the Mediterranean bioregion, where 44.4% of the silvoarable systems were present, particularly in Spain, Italy, and Greece. In the Atlantic bioregion, only 11.3% of the identified SA systems were found, with France, Germany, and the United Kingdom showing the largest areas, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

3.2. Potential Carbon Removal Rates

Table 2 summarizes the potential carbon removal rates of silvopastoral and silvoarable systems. For each biogeographical region, it reports the mean aboveground biomass carbon (AGC) and belowground biomass carbon (BGC) associated with each tree genus. A representative mean carbon removal rate, integrating both AGC and BGC, is then computed across all tree genera within each region.

Trees in silvopastoral systems have significant removal rates across all regions. The highest rate is recorded in the Continental bioregion, mainly by poplar trees, which have a rate of 3.21 t C ha−1 yr−1. The contributions from the Atlantic and Mediterranean regions are both via poplar, oak, olive, and conifer trees. On the other hand, trees within silvoarable systems have demonstrated varying sequestration rates, with the highest mean potential observed in the Atlantic bioregion, mainly contributed by poplar trees, with a removal rate of 6.89 t C ha−1 yr−1.

The data in

Table 2 highlight that both systems have substantial carbon removal rates, with notable differences between bioregions and tree genera, which comprise different species in each bioregion. Silvopastoral systems generally show higher carbon storage potential in the Continental bioregion, while silvoarable systems are more effective in the Atlantic bioregion. Among individual tree genera, poplars consistently demonstrate the highest sequestration rate across all bioregions and systems. Considering tree density per unit area and their age, data gathered from silvopastoral systems were associated with higher tree density and older trees, especially in the Mediterranean. This explains the greater carbon removal rates in the silvopastoral systems due to the higher biomass accumulation linked with older and more trees. On the other hand, silvoarable systems, while still contributing to carbon removal, demonstrate a lower rate since they are younger and have a lower tree density.

Total Tree Biomass Carbon Sequestration of AF

Table 3 presents the biomass carbon removal potential of agroforestry systems across the study region. The numbers were obtained by multiplying the tree biomass carbon removal rates (

Table 2) by the corresponding surface areas (

Table 1). As of 2018, trees of the silvopastoral and silvoarable systems together sequestered 81.67 Mt CO

2, with silvopastoral and silvoarable systems contributing by 63.08 and 18.59 Mt CO

2, representing 77.2 and 22.8% of the total sequestration, respectively.

As the Mediterranean bioregion has the largest areas of these systems with higher removal rates, it contributed 51.26 Mt CO2 or 62.76%, followed by the Continental and Atlantic regions. A total of 81.6% or 41.8 Mt CO2 of the Mediterranean region contribution came from trees of silvopastoral systems, while the rest, 18.4% or 9.4 Mt CO2, are sequestered by trees in the silvoarable systems. In terms of the contribution of individual states, Spain is the largest contributor, with 40.95% or 33.4 Mt CO2, followed by Portugal and Germany, with 10% or 8.2 Mt CO2, and 7.97% or 6.5 Mt CO2, respectively. Estonia and Finland have made no contribution due to the fact that the studied bioregions have no presence there.

3.3. Management Activities and the Potential GHG Emission Rates of Agroforestry Systems

On-farm management activities and processes within agroforestry systems were identified as activities with the potential to contribute to GHGs (

Table 4) and are relevant for the estimation of potential emissions of agroforestry systems. The major activities and processes that have the potential to contribute to GHG emissions within agroforestry systems include enteric fermentation, fertilisation and manure applications, tree thinning, grazing, and harvesting. Out of these, animal-related activities or processes such as grazing and enteric fermentation are significant contributors, especially in silvopastoral systems, where they could contribute by 1 and 3.67 t CO

2 eq ha

−1 year

−1, respectively.

Emissions from silvoarable systems are primarily driven by crop harvesting. In silvopastoral systems, grazing is a major source, as nearly all grazed biomass is respired by animals. Additionally, forest management activities like pruning and thinning contribute moderately to silvopastoral emissions, assuming the removed biomass is used for firewood.

Total and Net Emissions/Removals from Silvopastoral and Silvoarable Systems

Figure 4 illustrates the potential emissions from silvopastoral and silvoarable systems for the 15 countries with the highest contributions within the study area. Total emissions are estimated at approximately 49.8 Mt CO

2 eq in 2018, with an average of 5.4 t CO

2 eq ha

−1. Of this total, silvopastoral systems account for 69.7% (34.79 Mt CO

2 eq), while silvoarable areas contribute 30.3% (15.1 Mt CO

2 eq). Italy, Portugal, Spain, France, and Germany are the largest emitters from silvopastoral systems, largely due to the extensive land areas allocated to this type of land use. Notably, Spain alone is responsible for 16.9 Mt CO

2 eq, or 48.5% of emissions from silvopastoral areas, reflecting its widespread adoption of these systems.

Silvoarable areas, on the other hand, show that Spain, Italy, Germany, France, and Poland emerge as the leading emitters, all combined contributing to approximately 60.48% of the total silvoarable areas’ emissions.

Figure 4 demonstrates a general trend where larger states with more land areas of such land use systems tend to have higher emissions from agroforestry systems, particularly from the silvopastoral areas. Nevertheless, the variations in the level of emissions among the states might not only be due to the size of the agroforestry system but also may reflect the differences in the management practices and system efficiencies.

In terms of the net emissions/removals, the overall estimates indicate that there is a significant net removal of GHG, of −31.78 Mt CO

2 eq, 99% is from EU27; primarily attributed to silvopastoral areas, where they contribute by −28.29 Mt CO

2 eq, which play a dominant role in carbon sequestration, accounting for around 89% of the total net emissions (see

Table A3 in the

Appendix A). The remaining portion of the carbon removals of −3.48 Mt CO

2 eq or 11% is contributed by silvoarable systems. Although contributing less to overall net emissions than silvopastoral systems, these systems in countries like Spain and Portugal still have noteworthy carbon sequestration. Additionally, in Spain, Germany, Portugal, and France, their removals outweigh their emissions and thus are the largest contributors to removals, playing a significant role in achieving the overall reductions. However, in the cases of Austria, Bulgaria, and Croatia, the silvoarable areas indicated positive net emissions, highlighting that their removals are less than the emissions. Furthermore, several states have demonstrated substantial contributions when it comes to silvopastoral areas. Spain leads with 43.4% of the total due to its larger areas, followed by Portugal (11.3%), Germany (8.9%), France (7.1%), and Italy (5.1%). However, smaller contributions are attributed to states such as Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Slovenia. Other states, e.g., Estonia, recorded zero net emissions in this land use category, highlighting their lack of contributions.

3.4. Potential Impact on the EU’s LULUCF Carbon Inventory

Figures from the latest submitted NIRs and CRFs showed that in 2020, the EU27 reported a grand total of GHG emissions of approximately 2.7 billion t CO

2 eq yr

−1. Out of that, only around 8% or 0.2 billion comes from both the agriculture and LULUCF (AFOLU) sectors combined. The LULUCF sector alone, which includes six categories, contributes with net removals of around −239.44 Mt t CO

2 eq yr

−1, mainly coming from the forestland category. At the same time, agriculture contributes with net emissions of around 10.9 Mt CO

2 eq yr

1 (

Figure 5). Almost all other categories under LULUCF contribute with emissions rather than removals, including agroforestry systems, which are meant to be reported under the cropland categories. Our estimates indicate that the net removals from silvopastoral and silvoarable AF systems within the studied bioregions of EU27 only represent 13.31% of AFOLU’s net removals or −30.43 out of −228.53 Mt CO

2 eq yr

−1, corresponding to 12.71% of LULUCF’s net removals (assuming that emissions and removals of the studied land use systems already have been included in reports).

3.5. Future Possible Policy Scenarios

Given that the EU has committed to reducing its total emissions by 55% from 1990 levels as well as increasing tree cover by 3 billion trees by 2030, introducing trees within cropland and grassland areas, i.e., by creating agroforestry systems, three scenarios were simulated based on the target agroforestry areas, and subsequently, analyses were carried out.

Figure 6 shows the spatial distribution of target areas within EU3B in cropland and grassland areas, and

Table 5 presents the total surface area of target areas reported for cropland and grassland for the three considered bioregions. Additionally, country coverage of target areas in cropland and grasslands within the three selected bioregions is presented in

Table A4 in the

Appendix A.

When comparing target areas with national and agricultural land, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland, and Bulgaria each account for less than 5% of the total target area. However, in relative terms, these shares represent substantial proportions of their territories. For instance, Denmark contributes only 3.2% of the total target area, yet this corresponds to 37% of its national territory and 60% of its agricultural land, illustrating how smaller countries can hold disproportionately large fractions of target areas. By contrast, in larger countries such as France and Spain, the distribution of target areas is more closely aligned with their overall land and agricultural proportions. France, for example, accounts for 24.7% of the total target area, which amounts to 22.6% of its territory and 51.8% of its agricultural land. In absolute terms, this represents 12.4 million hectares suitable for agroforestry systems, underlining the considerable potential of major agricultural countries.

In general, there are 50.31 Mha of target agroforestry areas within the study area. Out of that, 94% or 47.30 Mha belong to the EU27. Much of that, roughly 81.7% or 38.7 Mha, is in croplands (

Figure 6), while the rest are within grasslands, highlighting the potential to introduce silvopastoral and silvoarable systems in the selected bioregions. In terms of countries, France leads, followed by Spain and Germany, representing 26.3, 21.8, and 10.6% of the total EU27, respectively. Countries such as Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Sweden recorded the lowest percentage of target areas, with less than 1%.

To explore possible land use change scenarios, the impact on the EU’s LULUCF inventory was evaluated for silvopastoral and silvoarable systems implementation across 10%, 20%, and 30% grassland and cropland categories, respectively. If all EU27 member states planted 10% of the identified target silvopastoral and silvorable areas within grassland and cropland categories, respectively, their total net removals would be approximately 47.1 Mt CO

2 eq yr

−1 (assuming removal rates of 2.97 and 2.14 C ha

−1 yr

−1 for silvopastoral and silvoarable systems, respectively), representing an increase of 54.7% (see potential removal in cropland and grasslands for each country in

Table A5 in the

Appendix A). Much of this increase would be made by France, Spain, and Germany, contributing together 58.9% of the total simulated removal. Whereas under 20% and 30% scenarios, they would contribute by 63.76 and 80.43 Mt CO

2 eq yr

−1, respectively; that is, 33.3 and 49.9 Mt CO

2 eq yr

−1 more than the 10% scenario.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of the current extent, spatial distribution, and climate mitigation contributions of silvopastoral and silvoarable systems across the EU27, the UK, and Switzerland, with a focus on the Atlantic, Continental, and Mediterranean (EU3B) biogeographical regions. Highlighting the significant yet often under-recognised role that agroforestry can play within the LULUCF sector, the present research estimates net removals of approximately 31.8 Mt CO2 eq yr−1, a meaningful contribution to the EU’s broader greenhouse gas reduction targets that varies considerably across bioregions and national contexts. The Mediterranean region emerges as a hotspot for both agroforestry surface area and carbon sequestration, reflecting favourable climatic and land use conditions. Moreover, this study includes an assessment of potential future land use change scenarios involving the expansion of silvopastoral and silvoarable areas within grassland and cropland covers, respectively. However, realising this mitigation potential depends on overcoming diverse barriers, ranging from socio-economic and policy constraints to management practices, that influence agroforestry adoption and effectiveness.

4.1. Study Limitations

Some limitations were identified during this study regarding the mapping and quantification of silvopastoral and silvoarable systems, including the lack of comprehensive emission rates that cover all bioregions, incomplete information on the full spectrum of farm management activities, and the somewhat limited representativeness of carbon data for silvopastoral and silvoarable systems within the EU3B region, particularly concerning the diversity of tree species considered.

Mapping silvopastoral and silvoarable areas poses significant challenges when estimating their total extent across Europe. These systems are inherently complex, comprising a variety of tree and crop species alongside diverse farming activities, which are difficult to capture accurately using spatially explicit datasets [

39]. Specifically, silvopastoral systems integrate trees with livestock grazing [

12], making it challenging to spatially allocate grazing activities due to the absence of dedicated datasets. Therefore, this study assumed that all pastures and grasslands associated with tree cover were grazed, which may introduce some uncertainty in estimating the silvopastoral area. Nevertheless, our area estimates align well with those from previous studies based on the LUCAS dataset [

11,

20], lending credibility to our approach. Moreover, the reference year for all spatial data products was 2018, reflecting the latest available Land Cover Map for Europe. Thus, the estimated extents of silvopastoral and silvoarable systems correspond to this reference year, along with their associated carbon inventories. Although this introduces a seven-year temporal gap, the analysis provides the most current comprehensive snapshot achievable with existing spatial datasets. The methodology can be updated and reapplied when newer products become available, enabling assessment of temporal changes and enhancements in accuracy.

The carbon inventory, which estimates gross carbon removals and emissions, was based on previous studies that applied emission factors and IPCC default values derived from experimental trials. While the removal rates used in this study represent all bioregions, the emission rates were restricted to only two: the Atlantic and Mediterranean. As these rates stem from controlled experimental conditions, they may not fully reflect the actual variability of emissions across the diverse silvopastoral and silvoarable landscapes of the EU3B region. Nevertheless, the analysis provides a broad, continental-level overview of greenhouse gas emissions associated with agroforestry systems. This scale is suitable for informing policymakers within the framework of European agricultural policies, as it addresses the Atlantic, Continental, and Mediterranean biogeographical regions, which together account for approximately 68% of the study area. However, this approach does not capture country-specific conditions, owing to both the scope of the study and the limited availability of harmonised data on agroforestry extent, management practices, emission factors, and land use change scenarios. Future research should therefore prioritise the development and integration of more regionally specific emission factors, explicitly capture country-level conditions, and better reflect the heterogeneity of agroforestry systems, including emissions from upstream processes such as fertilizer production and on-farm activities like machinery use.

4.2. Silvopastoral and Silvoarable Areas

The total area under agroforestry in the study region, comprising both silvopastoral and silvoarable systems, was estimated at 9.2 Mha, a figure that is consistent with findings from several other scientific studies. Den Herder et al. [

20] quantified the extent and distribution of agroforestry systems in the EU27 using the 2015 LUCAS dataset, distinguishing among arable agroforestry, livestock agroforestry, and high-value tree agroforestry, and estimated the total agroforestry area to be approximately 15.5 Mha. Importantly, their estimate for arable agroforestry, a category comparable with silvoarable systems, was closely aligned with our estimate, at around 3.2 Mha. More recently, Rubio-Delgado et al. [

11] employed the 2018 LUCAS dataset to estimate the agroforestry area across the EU27 and the UK. Their results indicated an area of about 11.4 Mha, encompassing six classes: grazed permanent crops, inter-cropped permanent crops, silvopastoral, silvoarable, agrosilvopastoral, and kitchen gardens. Within this classification, silvopastoral and silvoarable systems jointly covered approximately 9.3 Mha, which aligns closely with our findings.

Despite the broad agreement on agroforestry extent, there are notable methodological differences between our study and previous research, particularly in how agroforestry areas are identified. Our approach employs spatially explicit products, allowing for direct and precise mapping of the actual areas covered by silvopastoral and silvoarable systems. By contrast, estimates based on the LUCAS dataset rely on extrapolations derived from the number of agroforestry points recorded within a region, which are then multiplied by the region’s total area [

11,

20]. Although the LUCAS method benefits from field-based observations and the ability to document multiple land elements at each point, it lacks detailed quantification of the true surface area occupied by trees, crops, or pastures at those locations. Consequently, spatially explicit mapping, as applied in this study, provides a more accurate and detailed representation of agroforestry distribution and extent across the landscape. This precision is essential for generating reliable land cover data necessary for greenhouse gas inventories and for informing land use and climate mitigation policies [

40].

Furthermore, tree cover density is a crucial factor for classifying agroforestry systems. Given that agroforestry systems are complex and heterogeneous, no universally defined threshold exists for their classification. In a global assessment to quantify the area under agroforestry, Zomer et al. [

41] classified agroforestry areas as those showing 10% or more tree cover density, aligning with the 10% threshold recommended by the FAO for classifying forestry areas [

42]. However, in the European context, agroforestry areas often present values below 10%, as agricultural areas with sparse tree cover are still recognised as agroforestry systems. European studies have employed various thresholds: some use 5% tree cover density to classify agroforestry areas Rolo et al., 2021 [

43], while others apply even lower thresholds of 1% to capture the full spectrum of tree-agricultural integration [

11,

19]. The EURAF organization suggests that agricultural areas with less than 10% tree crown cover represent potential areas for agroforestry expansion, estimating 117.9 million hectares across the EU-27 with this characteristic [

44]. This variability in thresholds reflects the diversity of European agroforestry systems and the need for context-specific classification approaches.

4.3. Carbon Sequestration and Emissions Estimates

The study has also quantified the removals and emissions of the agroforestry systems accurately. The findings indicate that the EU27, UK, and CH, only considering the EU3B area, have an estimated area of 9.2 Mha of silvopastoral and silvoarable areas. Taking into account removal and emission rates of both studied land use systems, which range between 0.78–3.83 t C ha

−1 yr

−1 (molecular mass: 1 t C = 3.67 t of CO

2) and 4.7–5.7 t CO

2 eq ha

−1 yr

−1, respectively (based on a parcel density of around 140 trees per ha), they would sequester up to 81.67 million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year. This means a hectare of silvopastoral and silvoarable systems could sequester approximately 5.1 and 3.1 t CO

2 eq ha

−1 yr

−1, respectively, which aligns with estimates presented by Bertsch-Hoermann et al. [

45]. In terms of removal contributions in relation to agroforestry areas of individual countries, countries such as Italy, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Poland contributed with high a proportion of agroforestry area but with less mitigative effort due to the use of relatively low removal rates and much larger areas of these countries fall within Mediterranean biogeographical region, which has reported lower removals rates for the analysed trees. This is due primarily to low tree densities and younger trees. On the other hand, other states, i.e., Spain, the UK, France, and Belgium, attributed a higher removal proportion than their respective areas. This is the result of higher removal rates, especially within silvopastoral systems. In terms of emissions proportions in relation to the areas, no variation was reported. This is due to the pretty consistent emission rates for both studied land use systems used across the countries and regions. Subsequently, this has resulted in higher net positive removals in relation to the proportion of the area in cases, i.e., Belgium, Ireland, Spain, and the UK.

4.4. Target Areas to Introduce Agroforestry and Potential Impact on LULUCF Inventory

Different land use change scenarios were simulated to assess the potential for increased carbon sequestration through the adoption of agroforestry. Three scenarios were considered, each involving incremental expansions of agroforestry on target areas. In the first scenario, a 10% increase in target areas was assumed. Using estimated carbon removal rates of 2.97 t C ha−1 yr−1 for silvopastoral systems and 2.14 t C ha−1 yr−1 for silvoarable systems, with respective tree densities of approximately 164 and 114 trees ha−1, this scenario would add roughly 600 million trees to grassland and cropland areas. If these trees are planted in 2025 and maintain the same removal rates, the combined effect of new and existing agroforestry systems would result in an estimated carbon sequestration of about 200 Mt CO2 eq yr−1 by 2030, substantially increasing the LULUCF sector’s impact. Under more ambitious scenarios—20% and 30% expansion—agroforestry could contribute approximately 318 and 402 Mt CO2 eq yr−1, respectively, and add between 1.1 and 1.7 billion new trees. These contributions would significantly support achieving the EU 2030 target of planting 3 billion trees and reducing emissions by 55% compared to baseline levels.

Kay et al. [

46] carried out a study identifying priority areas for introducing AF based on various environmental pressure analyses, estimating an area of 13.6 Mha within the four European bioregions: EU3B and Steppic. They stated that, depending on the type of AF, such areas could lead to sequestration of 7.78 to 234.85 Mt CO

2 eq, contributing to 1.4–43.3% of the EU’s agricultural emissions. This aligns with our study findings under the third scenario, which considers around 14 Mha of the target areas. Moreover, our findings are also in line with the technical sequestration estimate of Aertsens et al. [

15], who stated that integrating agroforestry on the potential agricultural areas of 140 Mha in EU27 could sequester up to 1.4 billion t CO

2 eq yr

−1. The area in this study is 126 Mha, more than our study’s third scenario, which is why it resulted in 1.2 billion t CO

2 eq yr

−1 more.

However, it is important to recognise that the widespread adoption of agroforestry across Europe faces multiple barriers and challenges [

47]. From a farmer’s perspective, these obstacles include economic constraints, technical difficulties, and regulatory complexities associated with establishing and maintaining agroforestry systems [

48,

49,

50]. Addressing these barriers will require enhanced policy support that not only facilitates overcoming challenges but also maximizes opportunities to implement agroforestry in regions where environmental and socio-economic conditions are most favourable. Such targeted adoption can help alleviate environmental and social pressures while enhancing the delivery of diverse ecosystem services.

From an economic perspective, several challenges hinder the adoption of agroforestry systems. Key barriers include limited access to funding for establishment and maintenance, underdeveloped markets, and weak value chains for agroforestry products [

14,

51]. Additionally, trade-offs in ecosystem services have been identified that may reduce the competitiveness of agroforestry compared to conventional agriculture [

43,

52]. To address these challenges, payment for ecosystem services has been proposed as a financial mechanism to incentivize landowners to implement and maintain agroforestry practices [

53]. Such schemes enhance the economic viability of agroforestry by compensating for upfront costs and opportunity costs, thus fostering its role as an effective climate change mitigation strategy [

54,

55]. However, successful scaling up also requires attention to social, institutional, and market dimensions to overcome the multifaceted barriers that farmers experience [

14,

47,

48,

50].

5. Conclusions

This study provides a spatially explicit assessment of the current state and climate mitigation potential of silvopastoral and silvoarable agroforestry systems across the EU27, the UK, and Switzerland, with a particular focus on the Atlantic, Continental, and Mediterranean biogeographical regions (EU3B). It reveals that agroforestry covers approximately 9.2 million hectares (Mha), with the Mediterranean region, notably Spain, Portugal, and Italy, dominating both in terms of area (over 60% of the total) and carbon sequestration potential. Silvopastoral systems, especially those with older, denser tree stands, contribute the majority of carbon removals. The estimated net carbon removal by these systems is substantial, at around 81.7 Mt CO2 annually, with Spain alone contributing over 40% of this total, highlighting the role of Mediterranean agroforestry systems.

However, the study also points to significant regional and national variations in both carbon sequestration rates and emissions. While the Mediterranean benefits from favourable climatic conditions and extensive traditional systems like the Dehesa/Montado, other regions, such as the Atlantic and Continental, show lower but still meaningful contributions. Emissions from management activities, primarily grazing, harvesting, and fertilization, are notably higher in countries with large agroforestry areas, yet the overall balance remains strongly positive for climate mitigation. This analysis demonstrates that agroforestry’s net climate benefit is influenced not only by the extent of the area under these systems but also by tree species, age, density, and management practices. Countries with higher removal rates per hectare, such as Spain, the UK, France, and Belgium, achieve greater mitigation relative to their agroforestry area, while others with larger areas but lower removal rates (e.g., Italy, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Poland) see proportionally less benefit.

Furthermore, the study evaluates the potential for scaling up agroforestry by defining target areas to introduce silvopastoral and silvoarable systems in grasslands and cropland, respectively. Scenario analyses suggest that expanding agroforestry to 10%, 20%, or 30% of suitable areas could dramatically increase carbon removals, potentially sequestering up to 200–400 Mt CO2 eq annually by 2030 and supporting the EU’s ambition to plant 3 billion additional trees. Realising this potential, however, requires overcoming substantial barriers, including policy gaps, socio-economic constraints, and the need for improved spatial data and monitoring. The findings underscore agroforestry as a nature-based solution that can significantly enhance the EU’s Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) sector, contributing to both climate targets and broader sustainability goals, provided that supportive policies, incentives, and knowledge-sharing are prioritised in Europe.