Spatial Network Heterogeneity of Land Use Carbon Emissions and Ecosystem Services in Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Framework

3. Data and Methods

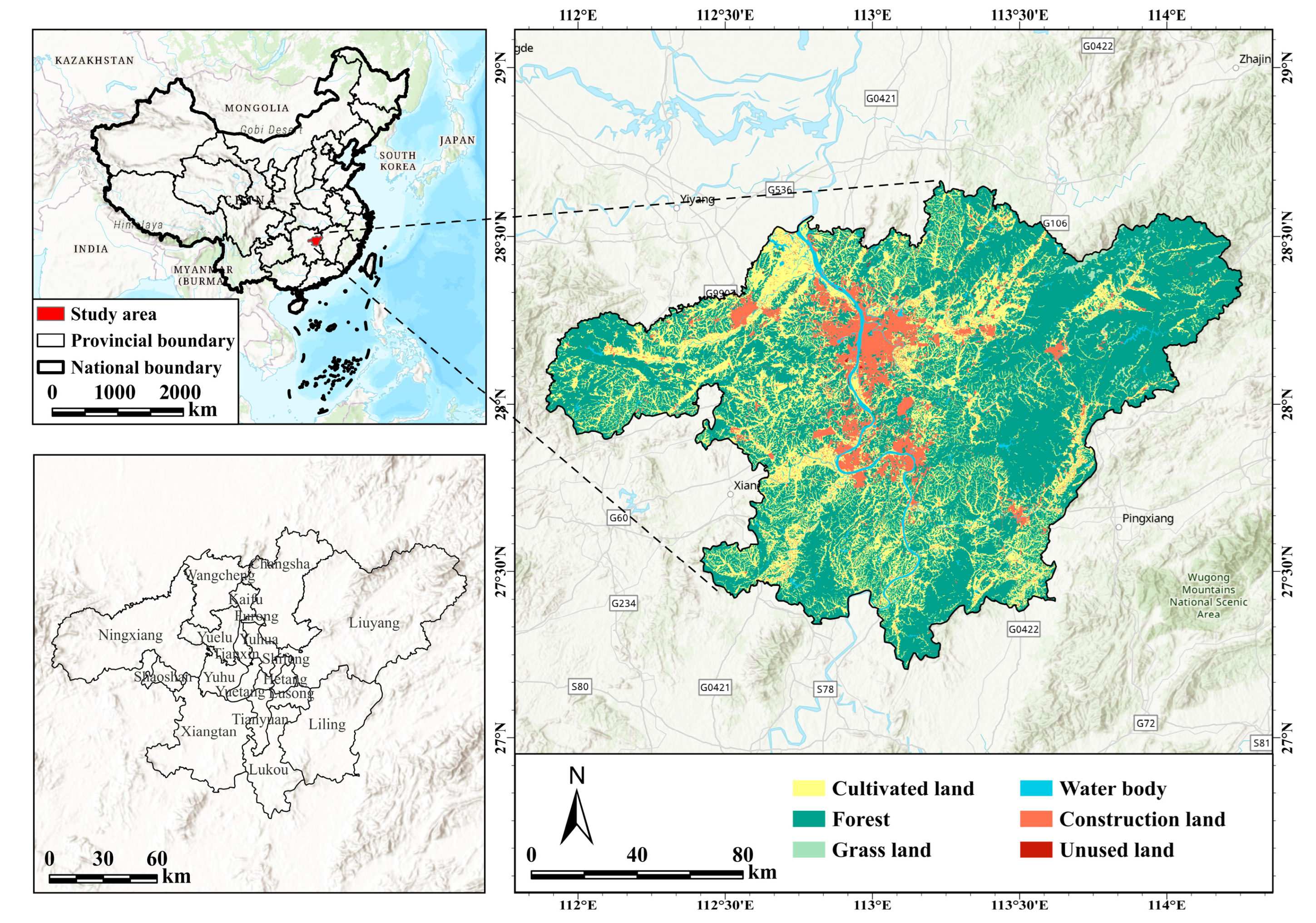

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Research Data

3.3. Research Methods

3.3.1. Carbon Emission Accounting

3.3.2. Ecosystem Service Evaluation

3.3.3. Modified Gravity Model and Spatial Association Matrix

3.3.4. Spatial Association Network Structure Analysis

3.3.5. Spatial Association Network Heterogeneity Analysis

3.3.6. Driving Factor Importance Assessment

4. Results and Analysis

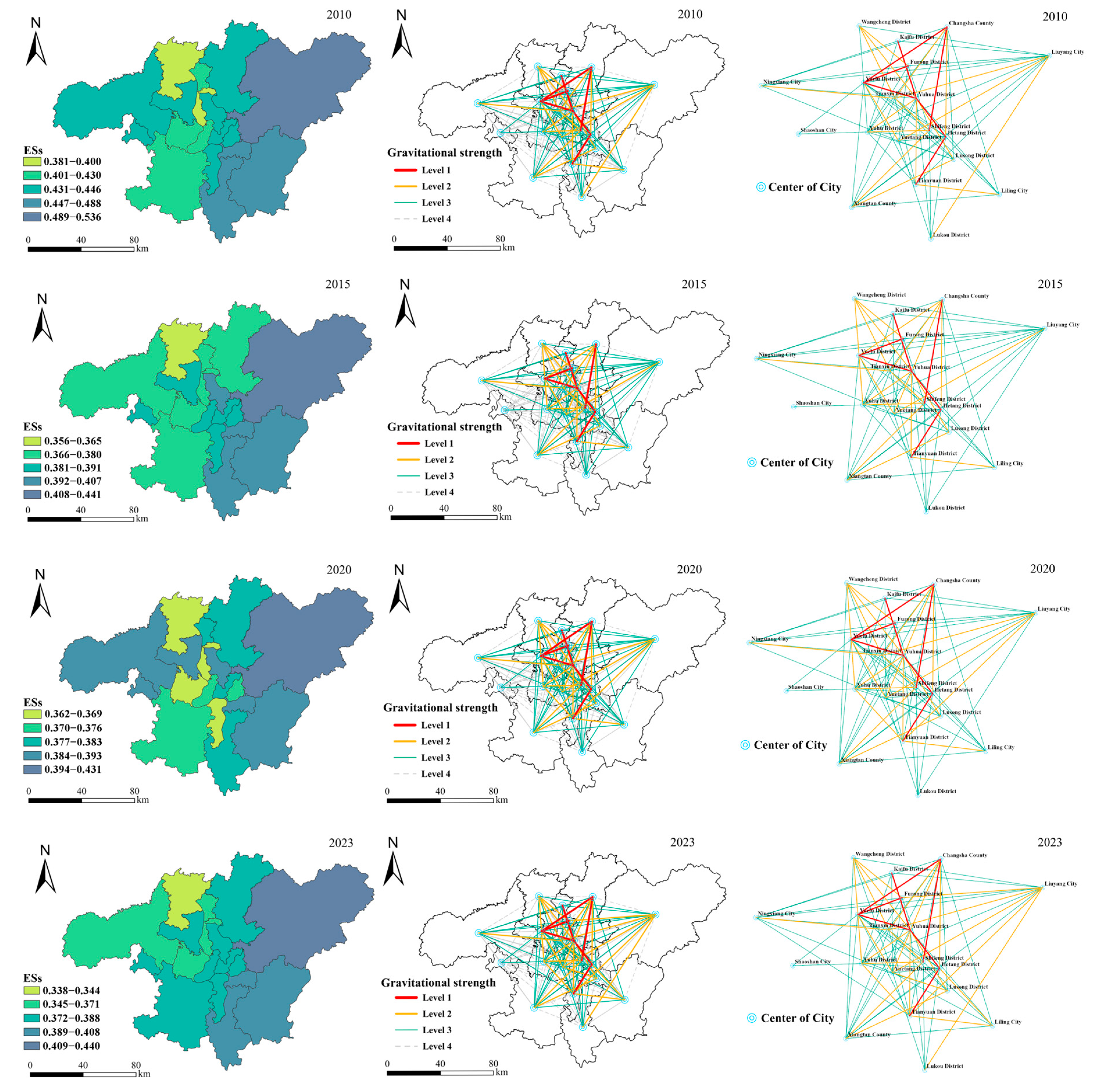

4.1. Overall Spatiotemporal Pattern

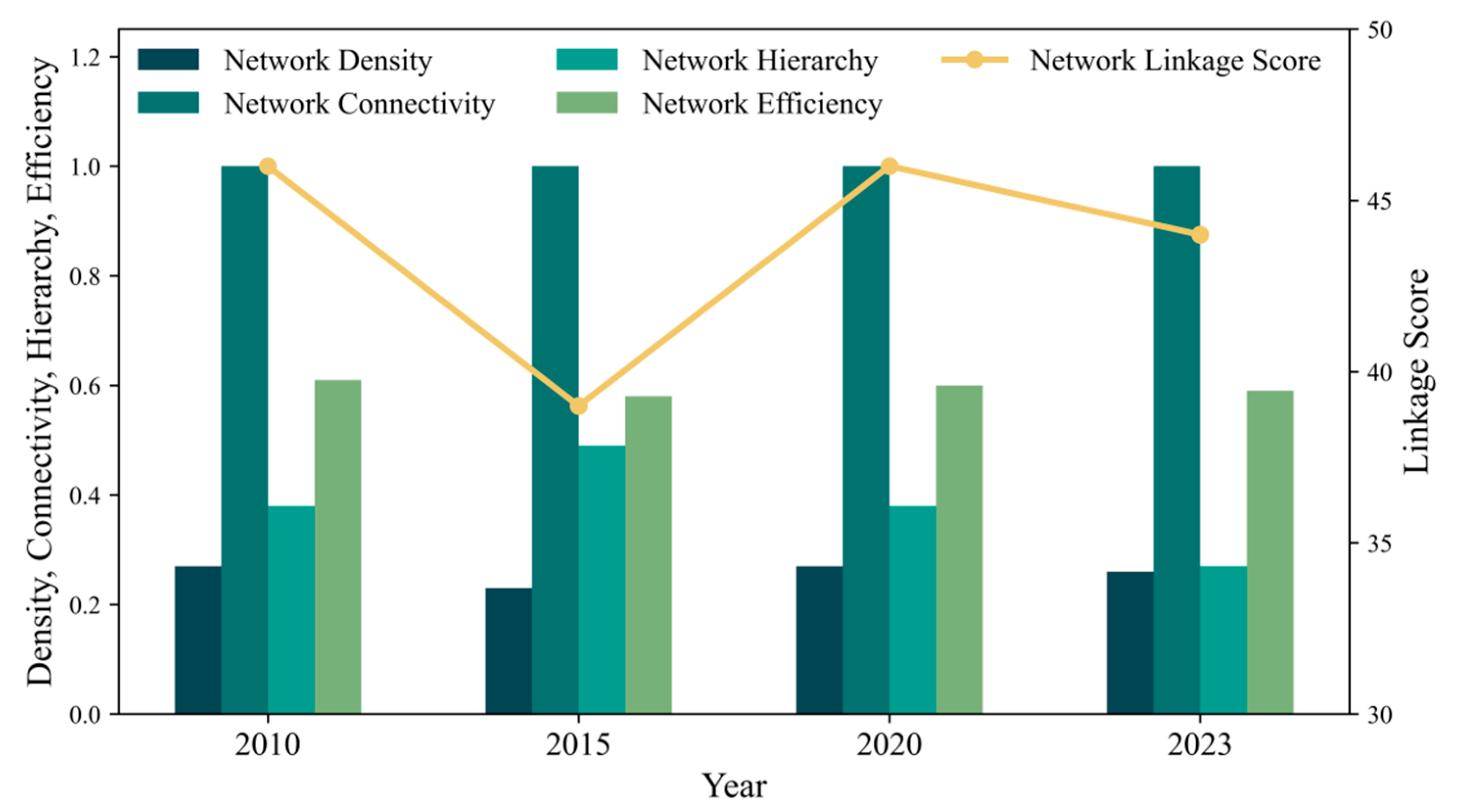

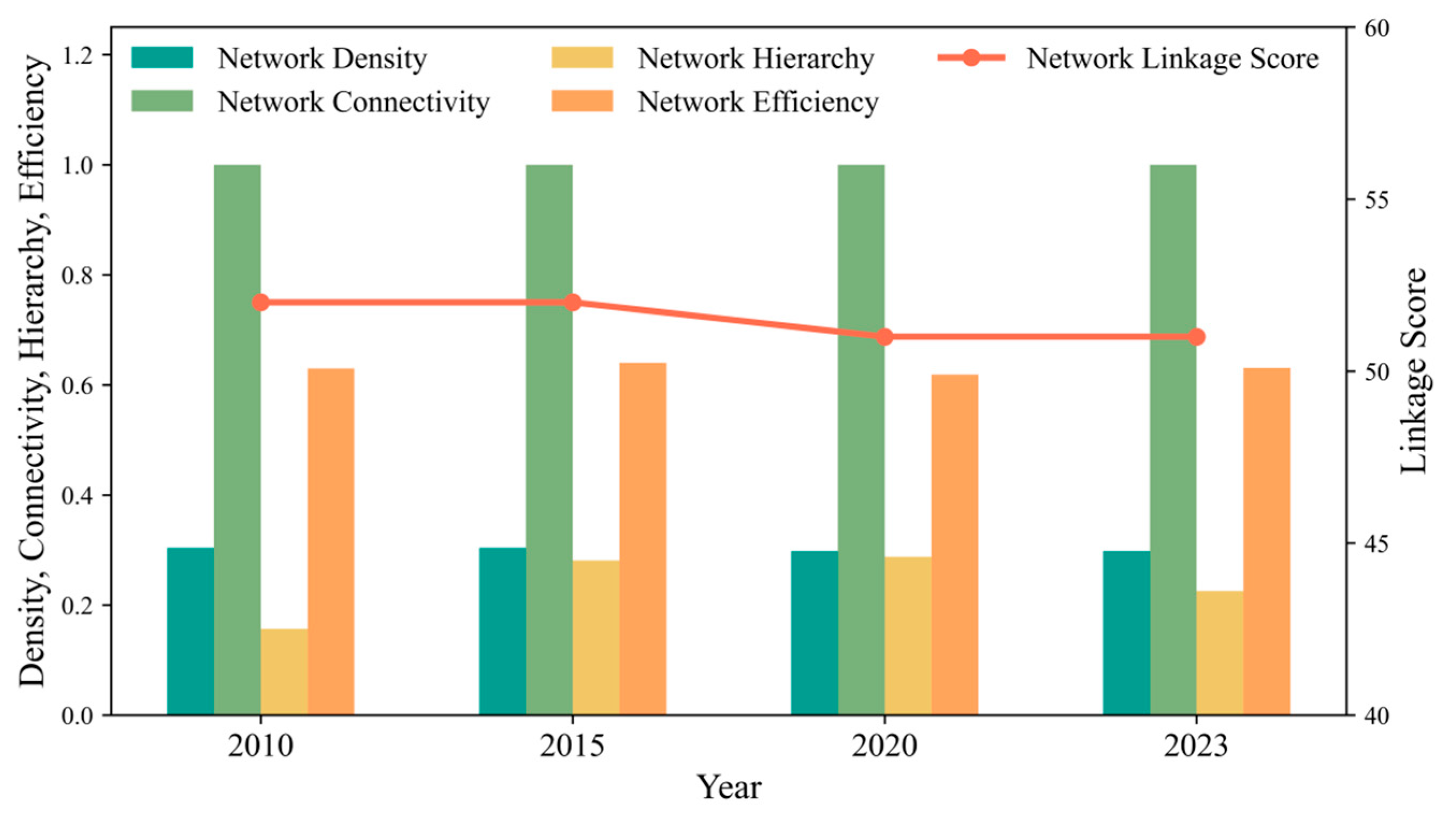

4.2. Analysis of the Overall Characteristics of the Spatial Association Network

4.3. Analysis of Individual Characteristics of the Spatial Association Network

4.3.1. Degree Centrality Analysis

4.3.2. Closeness Centrality Analysis

4.3.3. Betweenness Centrality Analysis

4.4. Analysis of Spatial Association Network Heterogeneity

4.5. Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms of Spatial Association Network Heterogeneity

4.5.1. Indicator Construction

4.5.2. Driving Mechanism Assessment

4.6. Collaborative Path of the Spatial Association Network

4.6.1. Structural Expansion Constraints, Ecological Connectivity Restoration

4.6.2. Accessibility Decentralization, Ecological Resistance Reduction

4.6.3. Channel Depointification, Ecological Substitution Reinforcement

4.6.4. Threshold Constraints, Closed-Loop Evaluation

5. Discussion

5.1. Dual Network Construction and Structural Characteristics

5.2. Network Differentiation Diagnosis

5.3. Ternary Coupling Drive and Synergy

5.4. Comparative Analysis of Regional Dynamics

5.5. Limitations and Outlook

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Xia, J. Effects of land use cover change on carbon emissions and ecosystem services in Chengyu urban agglomeration, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2020, 34, 1197–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, S.; Bai, X.; Luo, G.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, C.; Deng, Y. Global patterns and changes of carbon emissions from land use during 1992–2015. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2021, 7, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Yu, K.; Luo, P. Spatio-temporal relationship between land use carbon emissions and ecosystem service value in Guanzhong, China. Land 2024, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Gao, Z.; Zha, X.; He, D.; Chen, H. The spatial coupling of land use carbon emissions and ecosystem service value and its influence mechanism at county level in China. Acad. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 5, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muga, G.; Tiando, D.S.; Liu, C. Spatial relationship between carbon emissions and ecosystem service value based on land use: A case study of the Yellow River Basin. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, L.; Tong, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Yuan, L.; Xiao, J.; Wu, R.; Bai, L.; et al. Spatial correlations of land-use carbon emissions in the Yangtze River Delta region: A perspective from social network analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Jia, J.; Chen, D.; Liu, S. Evolution of spatial network structure for land-use carbon emissions and carbon balance zoning in Jiangxi Province: A social network analysis perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, Z.; Liu, W. Revealing the spatio-temporal coupling coordination characteristics and influencing factors of carbon emissions from urban use and ecosystem service values in China at the municipal scale. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 13, 1539909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xie, B.; Han, M. Unpacking the sub-regional spatial network of land-use carbon emissions: The case of Sichuan Province in China. Land 2023, 12, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Jin, G. Optimizing spatial patterns of ecosystem services in the Chang-Ji-Tu region (China) through Bayesian Belief Network and multi-scenario land use simulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Dai, X.; Zhou, J.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Lu, H.; Ye, Y.; et al. Evaluating trade-off and synergies of ecosystem services values of a representative resources-based urban ecosystem: A coupled modeling framework applied to Panzhihua City, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, J. Spatial and temporal driving mechanisms of ecosystem service trade-off/synergy in national key urban agglomerations: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cheng, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, J. Deciphering the spatiotemporal trade-offs and synergies between ecosystem services and their socio-ecological drivers in the plain river network area. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1212088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fu, B.; Wu, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, N.; Wu, X. Exploring the interdependencies of ecosystem services and social-ecological factors on the Loess Plateau through network analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 960, 178362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, M. Ecosystem carbon storage considering combined environmental and land-use changes in the future and pathways to carbon neutrality in developed regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.C.; Tian, Y.D.; Zhang, X.X. Spatiotemporal analysis of the relationship between land-use carbon emissions and ecosystem service value in the Chang-Zhu-Tan urban agglomeration. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 37, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Yue, S.; Chen, H. Carbon emission efficiency of China’s industry sectors: From the perspective of embodied carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Peng, S.; Benani, N.; Dong, L.; Li, X.; Liu, R.; Mao, G. An integrated evaluation on China’s provincial carbon peak and carbon neutrality. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, S. The spatial impact of carbon trading on harmonious economic and environmental development: Evidence from China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 6495–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Teng, F.; McLellan, B.C. A critical review on deployment planning and risk analysis of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) toward carbon neutrality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Teng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Ji, X. Simulation of land use and carbon storage evolution in multi-scenario: A case study in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Tao, Y.; Fu, W.; Li, T.; Ren, F.; Li, M. Dynamic simulation of land use/cover change and assessment of forest ecosystem carbon storage under climate change scenarios in Guangdong Province, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Wu, H.; Fan, X.; Jia, H.; Dong, T.; He, P.; Baqa, M.F.; Jiang, P. Trade-offs and synergies of multiple ecosystem services for different land use scenarios in the Yili River Valley, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Wang, A. System dynamics model of Beijing urban public transport carbon emissions based on carbon neutrality target. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 12681–12706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Dong, H.; Lu, C.; Li, W. Carbon emission projection and carbon quota allocation in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region of China under carbon neutrality vision. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.S.; Wang, M.Y.; Liu, C.; Chu, Y.-Q.; Li, C.-L. Research progress on the quantitative evaluation method of urban ecological carrying capacity. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 35, 2925–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, T.; Levasseur, A. System dynamics life cycle-based carbon model for consumption changes in urban metabolism. Ecol. Model. 2022, 473, 110010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, K. Dynamic simulation and projection of land use change using system dynamics model in the Chinese Tianshan mountainous region, Central Asia. Ecol. Model. 2024, 487, 110564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifayatullah, S.; Saqib, Z.; Khan, M.I.; Zaman-ul-Haq, M.; Kucher, D.E.; Ullah, S.; Tariq, A. Equitable urban green space planning for sustainable cities: A GIS-based analysis of spatial disparities and functional strategies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-López, J.E.; Mancini, C. Optimum thresholding using mean and conditional mean squared error. J. Econ. 2019, 208, 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, M.; Li, L.; Ouyang, S.; Wang, N.; La, L.; Liu, C.; Xiao, W. Identifying and analyzing ecosystem service bundles and their socioecological drivers in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Qiu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Sang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, K.; Ma, H.; Xu, Y.; Wan, Q. Land-use changes lead to a decrease in carbon storage in arid region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Kishore Karan, S.; Sardar, P.; Samadder, S.R. Remote sensing-based biomass estimation of dry deciduous tropical forest using machine learning and ensemble analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, E.; Lei, K. Spatial association network of carbon emission performance: Formation mechanism and structural characteristics. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 91, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Gu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, Y. Research on carbon emission efficiency space relations and network structure of the Yellow River Basin City Cluster. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Zhang, X.; Bizimana, A.; Zhou, T.; Liu, J.S.; Meng, X.Z. Achieving China’s carbon neutrality: Predicting driving factors of CO2 emission by artificial neural network. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.D.B.; Ortega, E. Dynamic emergy accounting of water and carbon ecosystem services: A model to simulate the impacts of land-use change. Ecol. Model. 2014, 271, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Wei, X.; Li, Y. Land space optimization of urban-agriculture-ecological functions in the Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan Urban Agglomeration, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 117, 106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.K.; Hemp, A.; Appelhans, T.; Becker, J.N.; Behler, C.; Classen, A.; Detsch, F.; Ensslin, A.; Ferger, S.W.; Frederiksen, S.B.; et al. Climate–land-use interactions shape tropical mountain biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Nature 2019, 568, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Cui, L.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Guo, G.; Zhang, X. Long-Term Effects of Ecological Restoration Projects on Ecosystem Services and Their Spatial Interactions: A Case Study of Hainan Tropical Forest Park in China. Environ. Manag. 2024, 73, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Xia, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, S.; Yang, Z. The carbon emissions related to the land-use changes from 2000 to 2015 in Shenzhen, China: Implication for exploring low-carbon development in megacities. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xie, B.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Xiao, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X. Factors impacting ecological network in Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan urban agglomeration, China—Based on the perspective of functional performance. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xie, Y.; Lei, F.; Cao, L.; Zeng, H. Analysis on spatio-temporal evolution and influencing factors of ecosystem service in the Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan urban agglomeration, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1334458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Xie, W.; Sun, Y. Spatiotemporal pattern evolution and influencing factors of population spatial distribution in Chang-sha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan urban agglomeration, China. J. Reg. Econ. 2024, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungarska, A.; Chakir, R. Projections of climate change impacts on ecosystem services and the role of land use adaptation in France. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 22, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hamid, H.T.; Toubar, M.M.; Zarzoura, F.; El-Alfy, M.A. Ecosystem services based on land use/cover and socio-economic factors in Lake Burullus, a Ramsar Site, Egypt. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 30, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D.R.P.; Sá, J.C.d.M.; Mishra, U.; Furlan, F.J.F.; Ferreira, L.A.; Inagaki, T.M.; Romaniw, J.; Ferreira, A.d.O.; Briedis, C. Soil carbon inventory to quantify the impact of land use change to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and ecosystem services. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243 Pt B, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Soliveres, S.; Penone, C.; Fischer, M.; Ammer, C.; Boch, R.S.; Boeddinghaus, M.; Bonkowski, F.; Buscot, A.M.; Fiore-Donno, K.; et al. Land-use intensity alters networks between biodiversity, ecosystem functions, and services. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 28140–28149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Hu, S.; Wu, S.; Song, J.; Li, H. County-level land use carbon emissions in China: Spatiotemporal patterns and impact factors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Song, F.; Su, F.; Shi, Z.; Song, S. Quantifying the independent contributions of climate and land use change to ecosystem services. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 153, 110411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardaker, A.; Pagella, T.; Rayment, M. Integrated assessment, valuation and mapping of ecosystem services and dis-services from upland land use in Wales. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Song, T.; Zou, X.; Wang, E.; Du, S. Accounting for China’s net carbon emissions and research on the realization path of carbon neutralization based on ecosystem carbon sinks. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; You, C.; Feng, C.C.; Guo, L. Spatial responses of ecosystem services to carbon emission efficiency based on spatial panel models in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, T.; Wang, J.; Fang, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhao, C. Integrating ecosystem services supply, demand and flow in ecological compensation: A case study of carbon sequestration services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydewitz, T.; Pradhan, P.; Landholm, D.M.; Kropp, J.P. Deforestation drivers across the tropics and their impacts on carbon stocks and ecosystem services. Anthr. Sci. 2023, 2, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.L. Revisiting “Additional Carbon”: Tracking atmosphere–ecosystem carbon exchange to establish mitigation and negative emissions from bio-based systems. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 603239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M.; Aalto, T.; Akujärvi, A.; Arslan, A.N.; Bergström, I.; Böttcher, K.; Lahtinen, I.; Mäkelä, A.; Markkanen, T.; Minunno, F.; et al. Ecosystem services related to carbon cycling—Modeling present and future impacts in boreal forests. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tan, X. Assessing the spatiotemporal patterns of ecosystem services (ESs) supply and demand in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 955876. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Yi, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, G.; Sun, D. Spatio-Temporal Coupling of Carbon Efficiency, Carbon Sink, and High-Quality Development in the Greater Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration: Patterns and Influences. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Sub-Data | Year Range | Spatial Resolution | Data Source | Date of Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Use Dataset | Land Use | 2010–2023 | 30 m | Resource and Environmental Science Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn) | 21 May 2025 |

| Auxiliary Geographic Dataset | Precipitation, Temperature, Evapotranspiration | 2010–2023 | 1000 m | National Meteorological Information Center (http://data.cma.cn) | 21 May 2025 |

| DEM, Slope | 2010–2023 | 30 m | Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn) | 28 May 2025 | |

| Soil Data | 2010–2023 | 1000 m | FAO Soils Portal (https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/) | 12 June 2025 | |

| Soil Erosion Factor Data | 2010–2023 | 1000 m | World Data Bank (https://www.scidb.cn) | 12 June 2025 | |

| Root Limitation Depth Data | 2010–2023 | 1000 m | ISRIC World Soil Information Service (https://www.isric.org/) | 12 June 2025 | |

| Panel Dataset | Population, GDP, Urbanization Rate | 2010–2023 | / | Hunan Statistical Yearbook. (http://tij.hunan.gov.cn) | 14 June 2025 |

| Energy Data | 2010–2023 | / | 14 June 2025 |

| Land Use Type | Carbon Emission Coefficient (kg/hm2·a) | Carbon Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivated Land | 0.4971 | Carbon Source |

| Forest Land | −0.5812 | Carbon Sink |

| Grassland | −0.0205 | Carbon Sink |

| Water Bodies | −0.0255 | Carbon Sink |

| Unused Land | −0.0005 | Carbon Sink |

| Energy Type | Coal | Coke | Crude Oil | Gasoline | Kerosene | Diesel | Fuel Oil | Natural Gas | Electricity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Coal Conversion Factor (tce·t−1) | 0.7143 | 0.9714 | 1.4286 | 1.4714 | 1.4714 | 1.4571 | 1.4286 | 1.2143 | 0.4040 |

| Carbon Emission Coefficient (t·tce−1) | 0.7559 | 0.8550 | 0.5857 | 0.5538 | 0.5714 | 0.5921 | 0.6185 | 0.4483 | 0.7935 |

| Service Type | Indicator | Assessment Method | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulating Services | Carbon Storage | InVEST Model—Carbon storage and sequestration module |

In the formula, C represents the annual total carbon storage; Cabove represents aboveground biomass carbon; Cbelow represents belowground biomass carbon; Csoil represents soil carbon; Cdead represents carbon content in dead material. |

| Soil Conservation | InVEST Model—Sediment delivery ratio module |

In the formula, SD represents the annual total soil conservation; RKLS represents potential soil erosion; USLE represents actual soil erosion; R represents rainfall erosivity factor; K represents soil erodibility factor; LS represents slope length and steepness factor; C represents vegetation cover and management factor; P represents soil conservation measure factor. All calculations are based on pixel units. | |

| Provisioning Services | Water Yield | InVEST Model—Annual water yield module |

In the formula, Y(x) represents the total annual water yield for the raster x; AET(x) represents the actual evapotranspiration for the raster x; P(x) represents the annual precipitation for the raster x. All calculations are based on pixel units. |

| Supporting Services | Habitat Quality | InVEST Model—Habitat quality module |

In the formula, Dxj represents the environmental stress index of the grid x in the land use type j; R represents the number of threat factors; Yr represents the number of grids for the threat factors r; wr represents the weight of threat factors r; ry represents the stress value for the raster unit y; irxy represents the influence value of the grid unit y on the land use unit x; βx represents the accessibility level of the threat factors for the raster unit x; Sjr represents the susceptibility of the environmental factor of the land use type j to the stressor r at the grid unit level; Qxj represents the environmental stress index for the land use type j in the grid unit x; Hj represents the environmental suitability index of the land use type j; z represents a unified value; commonly taken as 2.5 in this study; K represents a constant parameter, commonly taken as 0.5 in this study. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the results by varying the values of z and K. The analysis demonstrated that the overall trends and key findings remain consistent across a range of values for z and K, confirming that the results are not overly sensitive to these specific parameter choices. |

| Indicator | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 | |

| DCDI | 0.3944 | 0.5851 | 0.3956 | −0.0682 |

| CCDI | 0.0749 | 0.1021 | 0.0281 | −0.3071 |

| BCDI | 0.1871 | 0.4742 | 0.3429 | −0.3338 |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Unit | Model Variable | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Environment | Temperature | °C | X1 | Affects vegetation carbon absorption and emission intensity, altering network connections. |

| Average Annual Precipitation | mm | X2 | Determines moisture conditions, influencing the supply pattern of ecosystem services. | |

| Evapotranspiration | mm | X3 | Reflects water-heat conditions, constraining differences in carbon sequestration and service supply. | |

| Elevation | m | X4 | Affects land use distribution, causing differences in carbon emissions and service supply. | |

| Slope | ° | X5 | Restricts construction and cultivation, regulating spatial patterns of carbon emissions and services. | |

| Socio-Economic | GDP per capita | ten thousand yuan/person | X6 | Economic level drives carbon emission intensity and affects service demand. |

| Urbanization Rate | % | X7 | Urban expansion increases carbon emissions, disturbing the ecological service network. | |

| Population Density | / | X8 | Population concentration intensifies conflicts between carbon emissions and service supply and demand. | |

| Land Use Structure | Proportion of Arable Land | % | X9 | Determines the spatial pattern of carbon emissions and food supply. |

| Forest Cover | % | X10 | Core carbon sequestration area, enhancing service supply and spatial connectivity. | |

| Proportion of Construction Land | % | X11 | Expansion increases emissions, weakening the balance of ecological services. | |

| Landscape Fragmentation Index | / | X12 | Damages ecological connectivity, increasing network heterogeneity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, F.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M. Spatial Network Heterogeneity of Land Use Carbon Emissions and Ecosystem Services in Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration. Land 2025, 14, 2119. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112119

Liu F, Zhao X, Wang M. Spatial Network Heterogeneity of Land Use Carbon Emissions and Ecosystem Services in Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration. Land. 2025; 14(11):2119. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112119

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Fanmin, Xianchao Zhao, and Mengjie Wang. 2025. "Spatial Network Heterogeneity of Land Use Carbon Emissions and Ecosystem Services in Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration" Land 14, no. 11: 2119. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112119

APA StyleLiu, F., Zhao, X., & Wang, M. (2025). Spatial Network Heterogeneity of Land Use Carbon Emissions and Ecosystem Services in Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration. Land, 14(11), 2119. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112119