Transitional and Post-Mining Land Uses: A Global Review of Regulatory Frameworks, Decision-Making Criteria, and Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- The current legislative framework.

- -

- Alternative land uses.

- -

- Criteria for selecting land uses.

- -

- Decision-making methods for choosing the most appropriate land uses.

3. Selected Legal Regulations from Various National Contexts

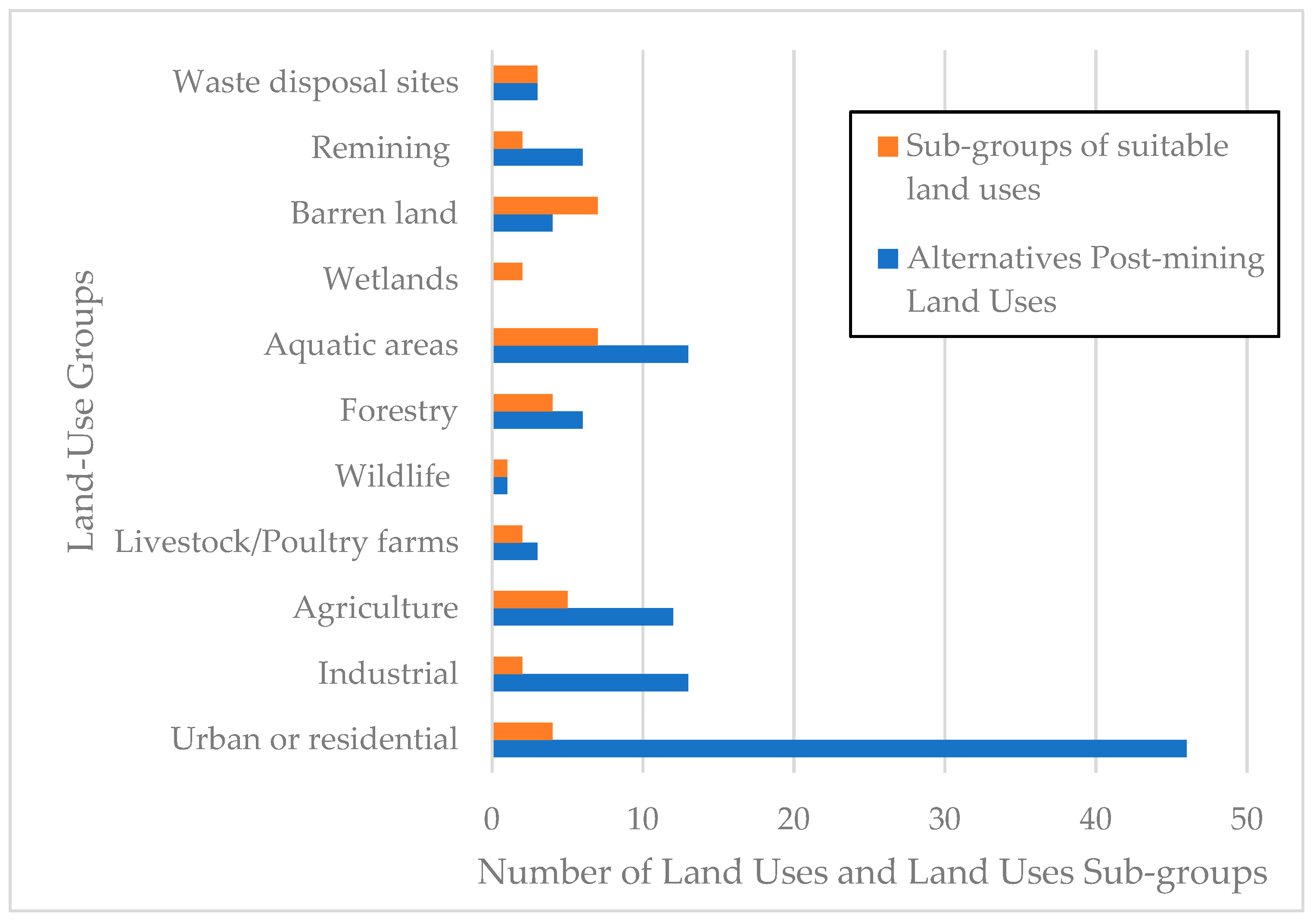

4. Transitional and Post-Closure Land Uses

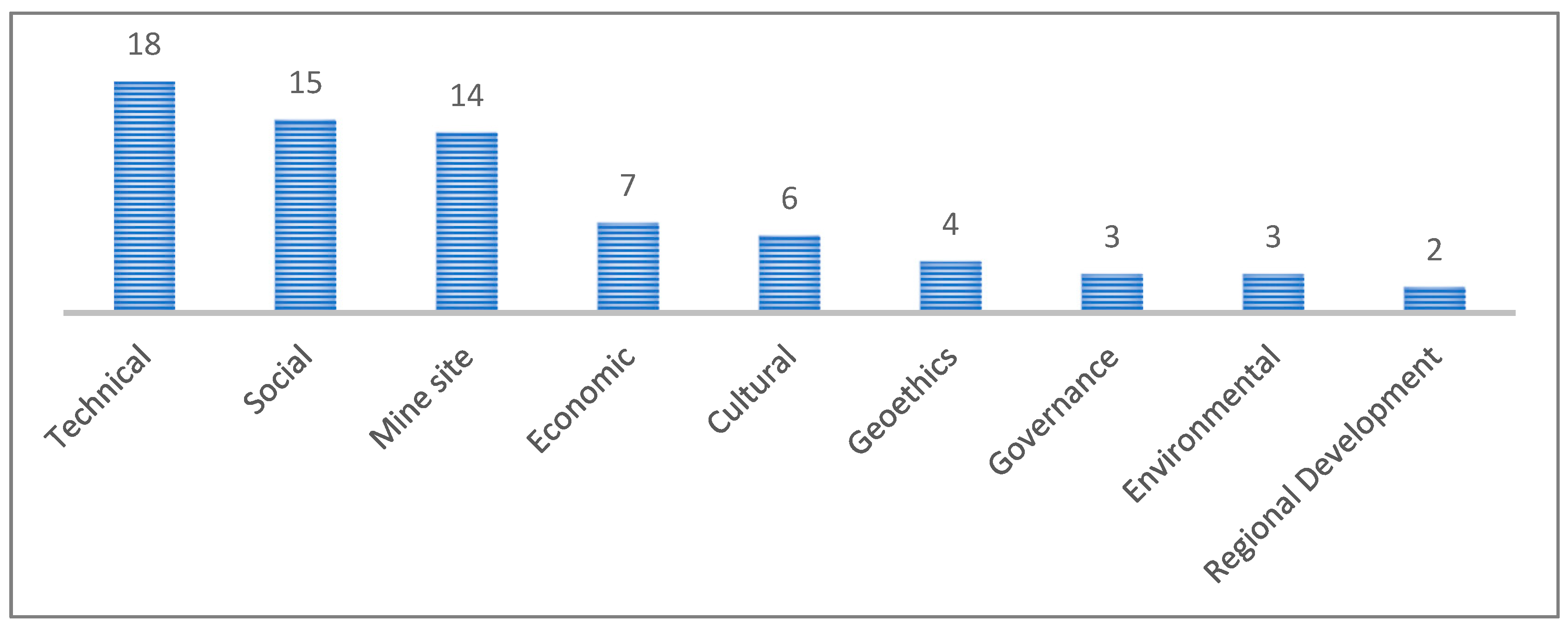

5. Criteria for the Selection of Post-Mining Land Uses

| Criteria | Attributes | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment |

|

| [8,49,78] | |

| Society |

|

| [8,49,79,80,81] | |

| Economy |

|

| [8,49,78,80,81] | |

| Mine site characteristics | Soil: |

| [80,81,82] | |

| Climate: |

|

| ||

| Topography: |

|

| ||

| Culture |

|

| [49] | |

| Technical aspects |

|

| [8,78,80,81] | |

| Governance |

|

| [8,12] | |

| Regional Development |

|

| [78,79] | |

| Geoethics |

|

| [78,79] | |

6. Μulti-Criteria Analysis Methods Applicable in Post-Mining Land-Use Selection

- -

- The nature of results the method is expected to bring, e.g., aiming at grading or ranking alternative solutions;

- -

- The scale of analysis, e.g., intra-enterprise or at a regional or national level;

- -

- The requirements and preferences, e.g., the number of alternatives to compare or judge, scales, acceptance of compensation among criteria, handling of imperfect knowledge, etc.;

- -

- The criteria type (e.g., in terms of data format and weights);

- -

- The practical considerations (e.g., software requirements and associated costs).

7. Synopsis and Discussion

- -

- The regulatory framework is based on environmental impact assessment studies and environmental permits that describe the land rehabilitation works planned to be carried out after mine closure before the beginning of the mine operation. Supervisory authorities are usually stricter with large mining companies. At the same time, large companies have the means to influence developments.

- -

- Mine operations decisively influence land restoration and land-use alternatives. For instance, whether there has been provision for separate excavation and storage of topsoil or whether overburden materials are deposited within the pit or in external dumps are choices that dictate post-mining developments.

- -

- Land restoration projects have commenced long before, and rightly so, decisions to cease operations, and, to some extent, have shaped land use for specific areas.

- -

- The mine land, due to its extensive acreage, represents one of the main assets of the mining enterprise and can be utilized for new business activities. A characteristic example is the installation of photovoltaic parks and energy storage systems in the lignite mines of RWE in Germany [109].

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Surface Mining Market. Available online: https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/surface-mining-market.html (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Hartman, H.L. SME Mining Engineering Handbook; Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration Littleton: Littleton, CO, USA, 1992; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.T.; Mitchell, K.; O’connell, D.W.; Verhoeven, J.; Van Cappellen, P. The legacy of surface mining: Remediation, restoration, reclamation and rehabilitation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harraz, H. Mining Methods: Part I-Surface Mining; Tanta University: Tanta, Egypt, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, D.; Memmott, P.; Reser, J.; Buultjens, J.; Thomson, L.; Barker, T.; O‘Rourke, T.; Chambers, C. Mining and Indigenous tourism in Northern Australia; Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, University of Queensland: Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 2014; pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Finucane, S.; Tarnowy, K. New uses for old infrastructure: 101 things to do with the ‘stuff’next to the hole in the ground. In Proceedings of the Mine Closure 2019: 13th International Conference on Mine Closure, Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Perth, Australia, 3–5 September 2019; pp. 479–496. [Google Scholar]

- H2020 MICA Project. Mine Closure Process (Overview of Different Phases and Actions); Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arratia-Solar, A.; Svobodova, K.; Lèbre, É.; Owen, J.R. Conceptual framework to assist in the decision-making process when planning for post-mining land-uses. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2022, 10, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festin, E.S.; Tigabu, M.; Chileshe, M.; Syampungani, S.; Oden, P. 108-2018-Progresses in restoration of post-mining landscape in Africa. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett; Fourie, A.B.; Tibbett, M. Abandoned Mines—Environmental, Social and Economic Challenges; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpitlaw, D.; Aken, M.; Lodewijks, H.; Viljoen, J. Post-mining rehabilitation, land use and pollution at collieries in South Africa. In Proceedings of the Colloquium: Sustainable Development in the Life of Coal Mining, South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Boksburg, South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy Johannesburg, Boksburg, South Africa, 13 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbread-Abrutat, P.H.; Kendle, A.D.; Coppin, N.J.; Tibbett, M.; Fourie, A.B.; Digby, C. Lessons for the Mining Industry from Non-Mining Landscape Restoration Experiences; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, B.; Baker, D. Mine Reclamation Planning in the Canadian North; Canadian Arctic Resources Committee: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1998; 82p, Available online: https://epub.sub.uni-hamburg.de/epub/volltexte/2010/5121/pdf/NMPWorkingPaper1BowmanandBaker.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2024)ISBN 0-919996-76-0.

- Keenan, J.; Holcombe, S. Mining as a temporary land use: A global stocktake of post-mining transitions and repurposing. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokratidou, A.; Gkouvatsou, E.; Roumpos, C.; Perdiou, A.; Tsagkarakis, G.; Kaimaki, S. Innovative approaches to coal surface mine sites rehabilitation: A case study of Megalopolis lignite fields. In Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium of Continuous Surface Mining, Thessaloniki, Greece, 23–26 September 2018; pp. 437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.; Clark, J. An International Overview of Legal Frameworks for Mine Closure. Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide: Eugene, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatyeva, M.; Yurak, V.; Pustokhina, N. Recultivation of Post-Mining Disturbed Land: Review of Content and Comparative Law and Feasibility Study. Resources 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Environment, Guidelines for Mine Closure Activities and Calculation an Periodic Adjustment of Financial Guarantees; Publications Office: Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2021; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/350770 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- European Commission. Mining Waste. 2024. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/mining-waste_en#related-links (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Cheng, L.; Skousen, J.G. Comparison of international mine reclamation bonding systems with recommendations for China. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2017, 4, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelestukov, V.; Drapezo, R.; Islamov, R. The Problems of Legal Regulation of the Land Reclamation after the Illegal Coal Mining by the “Black Diggers” (the Kemerovo region example). E3S Web Conf. 2020, 174, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verchagina, I.; Kolechkina, I.; Shustova, E. The Experience of Legal Regulation of Reclamation of the Developed Space by the Leading Countries of Coal Mining. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 174, 02012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhiman, R. Criminal Accountability for Mining Entrepreneurs Who Fail to Implement Reclamation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Law and Mining Law, ICTA II-MIL 2023, Pangkalpinang, Indonesia, 21 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Testa, S.M. Mine Reclamation Policy and Regulations of Selected Jurisdictions. In Acid Mine Drainage, Rock Drainage, and Acid Sulfate Soils; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Jurisdiction = Queensland, Australia; Sector = Government; Corporate name = Department of Environment. ‘Mining Rehabilitation Reforms’. 2024. Available online: https://environment.des.qld.gov.au/management/policy-regulation/mining-rehab-reforms (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Pinto, S.R.; Melo, F.; Tabarelli, M.; Padovesi, A.; Mesquita, C.; Scramuzza, C.A.; Castrp, P.; Carrascosa, H.; Calmon, M.; Rodrigues, R.; et al. Governing and delivering a biome-wide restoration initiative: The case of Atlantic Forest restoration pact in Brazil. Forests 2014, 5, 2212–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastauer, M.; Filho, P.W.M.S.; Ramos, S.J.; Caldeira, C.F.; Silva, J.R.; Siqueira, J.O.; Neto, A.E.F. Mine land rehabilitation in Brazil: Goals and techniques in the context of legal requirements. Ambio 2019, 48, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legislative Provisions—Ministère des Ressources Naturelles et des Forêts. Available online: https://mrnf.gouv.qc.ca/en/mines/mining-reclamation/legislative-provisions/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Architecture de Gestion de L’information Législative-Legal Information Management System Irosoft, ‘-Mining Act’. Available online: https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/document/lc/M-13.1?langCont=en (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Guidelines for Preparing Mine Closure Plans in Québec. Ministère des Ressources Naturelles et des Forêts. Available online: https://mrnf.gouv.qc.ca/en/mines/mining-reclamation/guidelines-for-preparing-mine-closure-plans-in-quebec/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Cao, X. Regulating mine land reclamation in developing countries: The case of China. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Hu, Z.; Fu, Y. Zoning of land reclamation in coal mining area and new progresses for the past 10 years. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2014, 1, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabant, S.A.; Montembault-Héveline, B. Reform of French Mineral Law. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 1997, 15, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greek Ministry of Environment, Energy, and Climate Change. National Regulation of Mining and Quarries Works; Ministerial Decision 223, Official Gazette of the Greek Government B 1227 14/06/ 2011; Greek Ministry of Environment, Energy, and Climate Change: Athens, Greece, 2011; p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, M.; Sarkar, S.C. Issues of Sustainable Development in the Mines and Minerals Sector in India. In Minerals and Allied Natural Resources and their Sustainable Development; Springer Geology: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSEP. Policy Analysis: Mine Closure in India—CSE. Available online: https://csep.org/blog/policy-analysis-mine-closure-in-india/ (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Silalahi, R. Liability of Mining Companies on Environmental Impact Issued by Law No 32 Year 2009 on Protection and Management of Environment. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Energy and Mining Law (ICEML 2018), Jakarta, Indonesia, 18–19 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyono, I.; Santiago, F. Post Mining Land Reclamation Reviewed from Government Regulation No 78 Year 2010 about Reclamtion and Post Mining Study Implementation of Reclamation (PT Dian Rana Petro Jasa) on Regency of South Sumatra Province. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Energy and Mining Law (ICEML 2018), Jakarta, Indonesia, 18–19 September 2018; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 136–139. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/iceml-18/25902914 (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Mintarsih, M.; Iskandar, M.; Sukamto, B. Law Enforcement to the Negligent Entrepreneurs in Accomplishing Mining Reclamation in order to be Efficient according to its Function. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Energy and Mining Law (ICEML), Salamanca, Spain, 9–11 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susmiyati, H.R. Legal Construction of Post-Mining Reclamation in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Joint Symposium on Tropical Studies (JSTS-19); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listiyani, N.; Said, M.; Khalid, A. Strengthening Reclamation Obligation through Mining Law Reform: Indonesian Experience. Resources 2023, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.; Mousavi, F.; Poorhashemi, A.; Karimi, D. Mining Law! An Opponent to Natural Resources, Environment, and Sustainable Development. SSRN 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, T.D. Evaluation of forestland use in mining operation activities in Turkey in terms of sustainable natural resources. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrega, A.; Uberman, R.C. Reclamation and revitalization of lands after mining activities: Polish achievements and problems, AGH. J. Min. Geoengin. 2012, 36, 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Juzaszek, E.; Sobczyk, W. Reclamation of Areas Transformed by Mining Activities in the Light of Polish Law. 2021. Available online: https://docs.academia.vn.ua/handle/123456789/584 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Laws & Regulations | Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. Available online: https://www.osmre.gov/laws-and-regulations (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Mborah, C.; Bansah, K.J.; Boateng, M.K. Evaluating alternate post-mining land-uses: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 5, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivinen, S. Sustainable Post-Mining Land Use: Are Closed Metal Mines Abandoned or Re-Used Space? Sustainability 2017, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdiansyah, H.; Utami, M.U.; Haryanto, J.T. Sustainability of post-mining land use and ecotourism. J. Perspekt. Pembiayaan Dan Pembang. Drh. 2018, 6, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpitlaw, D.; Briel, A. Post-mining land use opportunities in developing countries—A review. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2014, 114, 899–903. [Google Scholar]

- Gawor, Ł.; Jankowski, A.T.; Ruman, M. Post-mining dumping grounds as geotourist attractions in the Upper Silesian Coal Basin and the Ruhr District. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2011, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczak, U.; Lorenc, M.W.; Strzałkowski, P. The analysis of the existing terminology related to a post-mining land use: A proposal for new classification. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mert, Y. Contribution to sustainable development: Re-development of post-mining brownfields. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousova, O.; Medvedeva, T.; Aksenova, Z. A botanical gardening facility as a method of reclamation and integration of devastated territories (based on the example of the Eden Project). Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczyńska, E.; Lorenc, M.W. Eden Project-the Cornwall Peninsula peculiarity. Geotourism/Geoturystyka 2012, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Hansen, S. Stearns Quarry, Palmisano Park, Chicago, IL, Case Study’, Nov. 2014. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/case-study-briefs/palmisano-park-stearns-quarry (accessed on 26 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, D.; Duraj, M.; Cheng, X.; Marschalko, M.; Kubáč, J. Selected Black-Coal Mine Waste Dumps in the Ostrava-Karviná Region: An Analysis of Their Potential Use. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 95, 042061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Song, J. Review of photovoltaic and wind power systems utilized in the mining industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, Z.; Nikolić, D. Practical Example Of Solar And Hydro Energy Hybrid System-The Need For A Reversible Power Plant. Zb. Međunar. Konf. O Obnovljivim Izvorima Električne Energ. 2018, 6, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M.; Parameswaran, K. 21st Century Alchemy: Transitioning from Mining to Solar. Processing of the 2017-Sustainable Industrial Processing Summit, Flogen Star Outreach, Cancún, Mexico, 22–26 October 2017; pp. 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Tzelepi, V.; Zeneli, M.; Kourkoumpas, D.-S.; Karampinis, E.; Gypakis, A.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Grammelis, P. Biomass Availability in Europe as an Alternative Fuel for Full Conversion of Lignite Power Plants: A Critical Review. Energies 2020, 13, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, J.D.; Wright, D.G.; Dey, P.K.; Ghosh, S.K.; Davies, P.A. A comparative assessment of waste incinerators in the UK. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2234–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavloudakis, F.; Roumpos, C.; Karlopoulos, E.; Koukouzas, N. Sustainable Rehabilitation of Surface Coal Mining Areas: The Case of Greek Lignite Mines. Energies 2020, 13, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavourides, C.; Pavloudakis, F.; Filios, P. Environmental Protection and Land Reclamation Works in West Macedonia Lignite Centre in North Greece Current Practice and Future Perspectives. In Proceedings of the SWEMP 2002, Cagliari, Italy, 7–10 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, K.; Budi, S.W.; Suryaningtyas, D.; Yudhiman, E. Vegetation development in post-gold mining revegetation area in Minahasa, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2022, 23, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthrof, K.; Bell, R.; Calver, M.C. Establishment of Eucalyptus gomphocephala (Tuart) woodland species in an abandoned limestone quarry: Effects after 12 years. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 15, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, C.D.; Schultze, M.; Vandenberg, J. Realizing Beneficial End Uses from Abandoned Pit Lakes. Minerals 2020, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dino, G.A.; Chiappino, C.; Rossetti, P.; Franchi, A.; Baccioli, G. Extractive waste management: A new territorial and industrial approach in Carrara quarry basin. Ital. J. Eng. Geol. Env. 2017, 2017, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, W.; Ren, H.; Fu, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J. Natural recovery of different areas of a deserted quarry in South China. J. Environ. Sci. China 2008, 20, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łupieżowiec, M.; Rybak, J.; Różański, Z.; Dobrzycki, P.; Jędrzejczyk, W. Design and Construction of Foundations for Industrial Facilities in the Areas of Former Post-Mining Waste Dumps. Energies 2022, 15, 5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maest, A. Remining for Renewable Energy Metals: A Review of Characterization Needs, Resource Estimates, and Potential Environmental Effects. Minerals 2023, 13, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, J.; Garbarino, E.; Orveillon, G.; Saveyn, H.; Mateos Aquilino, V.; Llorens González, T.; García Polonio, F.; Horckmans, L.; D’Hugues, P.; Balomenos, E.; et al. Recovery of Critical and Other Raw Materials from Mining Waste and Iandfills: State of Play on Existing Practices, EUR 29744 EN; Blengini, G.A., Mathieux, F., Mancini, L., Nyberg, M., Viegas, H.M., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; ISBN 978-92-76-03391-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, M.A.; Nwachukwu, M.I. Model of Secure Landfill Using Abandoned Mine Pit—Technical and Economic Imperatives In Poor Developing Nations. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2016, 42, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fadel, M.; Sadek, S.; Chahine, W. Environmental Management of Quarries as Waste Disposal Facilities. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.; Kuras, O.; Meldrum, P.; Ogilvy, R.; Hollands, J. Electrical resistivity tomography applied to geologic, hydrogeologic, and engineering investigations at a former waste-disposal site. Geophysics 2006, 71, B231–B239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Guidelines for Land Use Planning. 1993. From FAO Corporate Document Repository. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/T0715E/t0715e00.htm#Contents (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Morales, F.; de Vries, W.T. Establishment of Land Use Suitability Mapping Criteria Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) with Practitioners and Beneficiaries. Land 2021, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Barbosa, S.; Ammerer, G.; Bruno, A.; Guimerà, J.; Orfanoudakis, I.; Ostręga, A.; Mylona, E.; Hitch, M.; Strydom, J. MCDM Applied to the Evaluation of Transitional and Post-Mining Conditions—An Innovative Perspective Developed through the EIT ReviRIS Project. Mater. Proc. 2021, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.L.; Barbosa, S.; Ammerer, G.; Bruno, A.; Guimerà, J.; Orfanoudakis, I.; Ostręga, A.; Mylona, E.; Strydom, J.; Hitch, M. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for Evaluating Transitional and Post-Mining Options—An Innovative Perspective from the EIT ReviRIS Project. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A.K. Rational selection of post-mining land use. Mining-Gateway to the Future. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual National Meeting of the American Society for Surface Mining and Reclamation, St. Louis, MI, USA, 3–7 June 1998; pp. 522–529. [Google Scholar]

- Amirshenava, S.; Osanloo, M. Strategic planning of post-mining land uses: A semi-quantitative approach based on the SWOT analysis and IE matrix. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirshenava, S.; Osanloo, M. Post-mining land-use planning: An integration of mined land suitability assessment and swot analysis in Chadormalu iron ore mine of Iran. In Proceedings of the 27th International Mining Congress and Exhibition of Turkey (IMCET 2022), Antlya, Turkey, 22–25 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mhlongo, S.E. Evaluating the post-mining land uses of former mine sites for sustainable purposes in South Africa. J. Sustain. Min. 2023, 22, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirshenava, S.; Osanloo, M. Mined land suitability assessment: A semi-quantitative approach based on a new classification of post-mining land uses. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2021, 35, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M. Development of a Decision Support System for Post Mining Land Use on Abandoned Surface Coal Mines in Appalachia. Master’s Thesis, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Masoumi, I.; Naraghi, S.; Rashidinejad, F.; Masoumi, S. Application of fuzzy multi-attribute decision-making to select and to rank the post-mining land-use. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.; Osanloo, M.; Hamidian, H. Selecting post mining land use through analytical hierarchy processing method: Case study in Sungun copper open pit mine of Iran. In Proceedings of the Fifteen International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection (MPES 2006), Torino, Italy, 20–22 September 2006; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanmohammadi, H.; Osanloo, M.; Bazzazi, A.A. Deriving preference order of post-mining land-uses through MLSA framework: Application of an outranking technique. Environ. Geol. 2009, 58, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Xue, L. Risk management for mine closure: A cloud model and hybrid semi-quantitative decision method. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2020, 27, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cınar, N.C.; Ocalır, E.V. A Reclamation Model for Post-Mining Marble Quarries. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2019, 32, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanmohammadi, H.; Osanloo, M.; Rezaei, B.; Bazzazi, A.A. Achieving to some outranking relationships between post mining land uses through mined land suitability analysis. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 5, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, M.; Idrus, A.; Amijaya, D.H.; Subagyo, B. Fuzzy Logic Approach for Post-Mining Land Use Planning: A Case Study on Coal Mine of Pt. Adaro Indonesia-South Kalimantan. Indones. Min. J. 2017, 20, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtavar, E.; Aghayarloo, R.; Yousefi, S.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Renewable energy based mine reclamation strategy: A hybrid fuzzy-based network analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servou, A.; Paraskevis, N.; Roumpos, C.; Pavloudakis, F. A Geospatial Analysis Model for the Selection of Post-Mining Land Uses in Surface Lignite Mines: Application in the Ptolemais Mines, Greece. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivinen, S.; Vartiainen, K.; Kumpula, T. People and Post-Mining Environments: PPGIS Mapping of Landscape Values, Knowledge Needs, and Future Perspectives in Northern Finland. Land 2018, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narrei, S.; Osanloo, M. Post-mining land-use methods optimum ranking, using multi attribute decision techniques with regard to sustainable resources management. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanmohammadi, H.; Osanloo, M.; Bazzazi, A.A. An analytical approach with a reliable logic and a ranking policy for post-mining land-use determination. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenicka, P.; Molnarova, K. Visual Perception of Habitats Adopted for Post-Mining Landscape Rehabilitation. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, S.; Svobodova, K.; Côte, C.; Bolz, P. Regional post-mining land use assessment: An interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder approach. Resour. Policy 2024, 89, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Baffour, F.; Daum, T.; Obeng, E.A.; Birner, R.; Bosch, C. Making Land Rehabilitation Projects Work in Small-Scale Mining Areas: Insights from a Case Study in Ghana. University of Hohenheim. 2023. Available online: https://490c.uni-hohenheim.de/fileadmin/einrichtungen/490c/Publications/WP15-23_Making_land_rehabilitation_projects_work_in_ASM_areas_Insights_from_a_case_study_in_Ghana.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Ahlheim, M.; Frör, O.; Lehr, U.; Wagenhals, G.; Wolf, U. Contingent Valuation of Mining Land Reclamation in East Germany; Citeseer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spanidis, P.-M.; Pavloudakis, F.; Roumpos, C. Introducing the IDEF0 Methodology in the Strategic Planning of Projects for Reclamation and Repurposing of Surface Mines. Mater. Proc. 2021, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Słowiński, R. Questions guiding the choice of a multicriteria decision aiding method. EURO J. Decis. Process. 2013, 1, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Sanders, D. Selection of discrete multiple criteria decision making methods in the presence of risk and uncertainty. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2018, 5, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, P.; Campos, A.R.; Neves-Silva, R. First Look at MCDM: Choosing a Decision Method. Adv. Smart Syst. Res. 2013, 3, 25–30. Available online: http://nimbusvault.net/publications/koala/assr/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Ganatsas, P.; Tsakaldimi, M.; Ioannidis, L.; Strafkou, T. Evaluation of restoration of an asbestos mine, in northern Greece, eight years after restoration works. J. Degrad. Min. Lands Manag. 2021, 8, 2957–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.S.; Kharel, G. Acid mine drainage from coal mining in the United States—An overview. J. Hydrol. 2020, 588, 125061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Review: Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) in Abandoned Coal Mines of Shanxi, China. Water 2021, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RWE. Solar Energy from Our Opencast Mines. 2024. Available online: https://www.rwe.com/en/research-and-development/solar-energy-projects/solar-energy-in-opencast-mines/ (accessed on 6 July 2024).

| Methods | Attributes | Deposits |

|---|---|---|

| Open-pit mining (or open-cast or area mining) | Removal of overburden to create access to the deposit, use of conventional digging and hauling equipment or continuous mining systems, dumping of overburden both inside and outside the mining area. | Large, near-surface deposits of metals, industrial minerals, and coal. |

| Quarrying | Similar to open-pit but with vertical faces and steep slopes. | Dimension stones and aggregates. |

| Strip mining | Long excavations in the direction of the mine face advance, relatively constant overburden thickness. | Horizontally bedded and relatively thin deposits, usually coal. |

| Contour (strip) mining | Progressive excavation of the slope of a hill until the stripping ratio reaches its marginal value. | Deposits located in mountainous areas. |

| Mountaintop removal mining | Removal of the top of a hill, dumping of overburden in waste embankment outside the mining area. | Deposits located in mountainous areas. |

| Land Management Strategies | Targets | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Abandonment | None | “Zero action”, changes in the disturbed land occur only due to slow-evolving natural process |

| Remediation | Soil, water | Physical, chemical, or biological decontamination of soil and water |

| Restoration | Ecosystem | Improvement of degraded areas in order to return the ecosystem to its previous state |

| Reclamation | Land | Development of a new ecosystem, similar to the previous one, which fulfills the same functions |

| Rehabilitation | Land | Application of new land uses that support sustainable environmental and social development |

| Repurposing | Site | Development of alternative uses for pre-existing infrastructure |

| Co-purposing | Site | Coexistence of mining with other activities developed in areas that are no longer used for mining operations |

| Country | Law | References |

|---|---|---|

| Republic of South Africa | Minerals Act (Act 50, 1991); Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (Act 28, 2002) | [11,24] |

| Australia | Mining Act (1978); Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999); Environmental Protection Acts and Regulations of Australian states (e.g., Queensland’s Mineral and Energy Resources (Financial Provisioning) Act (2018)), Strong and Sustainable Resource Communities (SSRC) Act (2017), and Environmental Protection (Rehabilitation Reform) Amendment Regulation (2019) | [16,20,24,25] |

| Brazil | Constitution of Brazil; Decree-Law No. 227/1967; National Environmental Act (Law 6938/1981); Decree No. 9, 406/2018 | [26,27] |

| Canada | Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA, 2012); Provincial Laws and Regulations (e.g., Ontario’s Mining Act, 1990, and Quebec’s Regulation respecting mineral substances other than petroleum, natural gas, and brine, 1988). | [16,20,24,28,29,30] |

| China | Land Administration Law (revised, 1999); Land Management Act (1999); Land Reclamation Regulation No. 592 (2011); Regulation on Compiling Land Reclamation Plan (2011); Implementation Measures on Land Reclamation Regulation (2012); Completion Standards on Land Reclamation Quality (2013). Other legislation of the People’s Republic of China relevant to mine land reclamation: Mineral Resources Law (1986, amended in 1996 and 2009), Environmental Protection Law (revised, 2014); the Coal Law (1996); Water Resources Law (2002); Water and Soil Conservation Law (2010); Forestry Law (2019); Grassland Law (2021) | [16,20,22,31,32] |

| France | Mining Code (Law 94-588, 1994); Environmental Code (1999) | [33] |

| Germany | Federal Mining Act (1982, revised in 2006) | [16,17,24] |

| Greece | Regulation of Mining and Quarrying Works (Ministerial Decision 2223, Official Gazette of the Government 1227-14/06/2011) | [34] |

| India | Mineral Concession Rules (1960); Mineral Conservation and Development Rules (1988); Mine Closure Rules MCDR (2017) | [16,35,36] |

| Indonesia | Indonesian Constitution (Article 33); Law No. 40/2007 on Social and Environmental Responsibility of Companies of Limited Liabilities (Article 74); Law No. 4/2009 on Mineral and Coal Mining (Article 96); Government Regulation No.78/2010 on Post-Mining Reclamation; Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Regulations No. 7/2014 on the Implementation of Reclamation in Mineral and Coal Mining Business Activities | [16,23,37,38,39,40,41] |

| Iran | The Consitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran (Article 45); Mining Act (1938, last amended in 2011); Forests Nationalization Act (1962); Environmental Protection and Improvement Act (1974); Environmental Regulation for Mining Activities 14/2005 | [16,42] |

| Poland | Resolution No. 256 (1961); Resolution No. 301 on the Reclamation and Redevelopment of Land Transformed (1966); Protection of Agricultural and Forest Land Act (1971, revised in 1995); Geological and Mining Law (1994) | [43,44] |

| Turkey | Regulation on the Recovery of Land Degraded as a Result of Mining Activities (2010) | [45] |

| UK | Coal Mines Regulation Act (1908); Mining Industry Act (1920); Coal Act (1938); Τhe Town and Country Planning Act (Scotland, 1947); Coal Industry Act (1949); Mineral Workings Act; Mines and Quarries Act (1969); Opencast Coal Act (1958); Mines Act (North Ireland, 1969); Environmental Protection Act (1990); Coal Industry Act (1994); Environment Act (1995) | [16,17] |

| USA | National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA, 1970); Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA, 1977) | [17,20,22,24,46] |

| Land-Use Classes | Land-Use Sub-Classes | Alternative Post-Mining Land Uses Implemented Globally to Date | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban or residential areas | Residential areas | Single- and multiple-family housing, mobile home parks, or other residential lodgings. | [6,15,48,50,51,52,53,54,55] |

| Commercial uses and services | Retail or trade of goods or services, hotels, motels, stores, restaurants, other commercial establishments, houseboats, churches, military installations, fire training arenas, shopping malls, exhibition centers, open-air shops, cafes, swimming pools, and libraries. | ||

| Public facilities and public use | Temporary homeless shelters, mobile homeless sanitation units, convention centers, mobile citizen service units, citizen service areas, and social service buildings. | ||

| Educational facilities | National monuments, world cultural heritage sites, sports facilities, astronomical observatories, botanical gardens. | ||

| Recreation and sports | Multi-use recreation park, including mountain bike trails, road bike tracks, cross country running tracks, scuba diving centers, ice rinks, concert venues, equestrian trails and picnic facilities, organized camping areas, museums, casinos, ski resorts, golf courses, ski slopes, motorsports, artificial ski centers, paragliding centers, geological natural monuments, zoos, ecotourism centers. | [6,15,25,26,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] | |

| Transportation, utilities, network Infrastructures | Roads, railway lines, water supply networks, wastewater treatment plants. | [6,48,49,50,51,53,56,57] | |

| Industrial areas | Industries, heavy and light manufacturing facilities, production of materials for fabrication and storage of products | Industrial development incubators, industrial facilities, warehouses—logistics, trade centers, brick factories, organic vegetable processing plants. | [6,48,50,51] |

| Energy Production | Wind power plants, wind power systems. | [51,58,59] | |

| Solar Power Plants (SPP) | [15,53,58,59,60] | ||

| Biomass-fired heat and power plants | [15,61] | ||

| WtE (Waste-to-Energy) plants | [14,62] | ||

| Agriculture | Cropland | Barley, wheat, chickpeas | [3,49,63] |

| Energy crops | Sorghum, artichoke | ||

| Other agricultural activities | Orchards, groves, vineyards, nurseries, cocoa trees, greenhouses, and ornamental horticultural areas. | ||

| Recreational and educational activities | Agrotourism, multifunctional farms. | ||

| Livestock farms | Pastureland, rangeland | Herbaceous rangeland, shrub and brush rangeland, clumps of bushes. | [49,50] |

| Poultry farms | Breeding units | [49] | |

| Wildlife | Wildlife shelters | Orangutans, bears, wolves, hares, wild cats, deer, reindeer, coyotes, foxes, opossums, raccoons, etc. | [49,56,64] |

| Wildlife sanctuary | |||

| Forestry/ Forest land | Deciduous forests | Reforested areas (e.g., maple, oak, beech, elm, poplar, birch, eucalyptus), collection of natural forest products (e.g., gum, cork, resins, balsam, kapok, acorns, horse chestnuts, mosses, lichens, mushrooms, herbs). | [3,9,15,20,34,47,52,57,63,65,66] |

| Evergreen forests | Reforested areas (e.g., pine, fir, cypress, cedar), collection of natural forest products (e.g., gum, cork, resins, balsam, kapok, acorns, horse chestnuts, mosses, lichens, mushrooms, herbs). | ||

| Mixed forests | (As the above two sub-groups) | ||

| Plantations and nurseries | Aesthetic plantations, plantations for logging and timber production, nurseries | ||

| Aquatic areas | Water bodies: streams, canals, lakes, reservoirs, bays | Water treatment, water storage, irrigation, fire protection, flood control and water supply, artificial reefs, artificial lakes | [6,11,15,49,57,67] |

| Aquaculture | Nila fish, Mujair fish and others, catfish, goldfish, tilapia, bluegill, largemouth bass, crappie, and channel catfish. | [6,49,56,67] | |

| Recreational and sports | Water bikes, rowing boats, development of nautical activities, diving facilities, marina (ports), organized camping area, | [15,34,48,49] | |

| Energy storage | Hybrid Pumped Hydro Storage, Renewable Energy Source (RES) projects | [59] | |

| Wetlands | Forest wetlands | Wildlife (aquatic and/or amphibian), recreational fishing. | [47,56,67] |

| Non-forest wetlands | Wildlife (aquatic and/or amphibian), recreational fishing. | ||

| Barren land Waste lands | Mine pits | Natural restoration of the environment, spontaneous vegetation of grasses and trees. (Common land uses for all sub-groups) | [9,50,68,69] |

| Overburden dumps | |||

| Dry tailings | |||

| Quarries and gravel pits | |||

| Remining | Raw Material | Co, Zn, Au, other precious metals | [70,71,72] |

| Recovery of secondary material | Tantalum and Niobium | [72] | |

| Waste disposal sites | Landfill sites | Legal landfill, illegal landfill | [20,43,44,45,48,56,64,73,74,75] |

| Waste treatment units | Waste treatment units | [62] | |

| Solid waste management facilities | Construction and demolition waste units Material storage facilities: scrap metal, tires, wooden train track sleepers, conveyor belts Waste material utilization facilities: tire sculpture, building, construction, garden fencing, furniture, auditoriums, horse and cow bedding, windbreaks, animal feeders, industrial yards, geotextile, waste rock facilities | [6,48,64] |

| Methods | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost—Benefit Analysis | [80] | |

| S.W.O.T. | [81,82,83] | |

| IE (Internal–External) Matrix | [81,84] | |

| Boolean Logic and Fuzzy Sets | [85,86] | |

| AHP—Analytic Hierarchy Process | [77,83,85,86,87,88] | |

| IAHP—Improved Analytic Hierarchy Process | [89] | |

| ANP—Analytic Network Process | [90] | |

| ELECTRE—ELimination Et Choix Traduisant la REalit’e | [91] | |

| Fuzzy Logic | [90,92] | |

| FCM—Fuzzy Cognitive Map | [93] | |

| FIS—Fuzzy Inference System | [93] | |

| FANP Fuzzy Analytical Network Process | [93] | |

| GIS—Geographic Information System | [85,88,90,94,95,96] | |

| SMART—Simple Multi-Attribute Ranking Technique | [85] | |

| LP—Linear Programming | [85] | |

| PROMETHEE—Preference Ranking Organization METHod for Enrichment of Evaluations | [88] | |

| TOPSIS—Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution | [79,86,89,97,98] | |

| SAW—Simple Additive Weighting | [99] | |

| Likert Scale | [81,98,99,100,101] | |

| IDEF0 | [102] | |

| SIMUS | [79] | |

| SMARTER | [79] | |

| Hybrid | SIMUS, TOPSIS, SMARTER. | [79] |

| SWOT, IE matrix | [81] | |

| AHP, SWOT | [83] | |

| MSLA, GIS, Fuzzy, Boolean Logic, AHP, SMART, Linear, Integer Programming | [85] | |

| Boolean Logic and Fuzzy Sets | [85,86] | |

| Fuzzy, AHP, TOPSIS | [86] | |

| PROMETHEE, AHP | [88] | |

| IAHP, TOPSIS | [89] | |

| GIS, ANP, MCDM, Fuzzy Logic | [90] | |

| AHP, ELECTRE | [91] | |

| GIS, Fuzzy | [92] | |

| FIS, FANP | [93] | |

| AHP, SAW, TOPSIS, Compromise Programming | [99] | |

| AHP, TOPSIS | [96] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagouni, C.; Pavloudakis, F.; Kapageridis, I.; Yiannakou, A. Transitional and Post-Mining Land Uses: A Global Review of Regulatory Frameworks, Decision-Making Criteria, and Methods. Land 2024, 13, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13071051

Pagouni C, Pavloudakis F, Kapageridis I, Yiannakou A. Transitional and Post-Mining Land Uses: A Global Review of Regulatory Frameworks, Decision-Making Criteria, and Methods. Land. 2024; 13(7):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13071051

Chicago/Turabian StylePagouni, Chrysoula, Francis Pavloudakis, Ioannis Kapageridis, and Athena Yiannakou. 2024. "Transitional and Post-Mining Land Uses: A Global Review of Regulatory Frameworks, Decision-Making Criteria, and Methods" Land 13, no. 7: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13071051

APA StylePagouni, C., Pavloudakis, F., Kapageridis, I., & Yiannakou, A. (2024). Transitional and Post-Mining Land Uses: A Global Review of Regulatory Frameworks, Decision-Making Criteria, and Methods. Land, 13(7), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13071051