Paths and Mechanisms of Rural Transformation Promoted by Rural Collectively Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketization in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Main Stages and Basic Operational Logic of the Reform of RCCCLM

2.1. The Main Stages of the Reform of RCCCLM

2.2. The Basic Operational Logic of RCCCLM

- (1)

- Bottom-line constraints. In the process of RCCCLM, the central government defines three bottom lines, namely “the nature of public ownership of land shall remain unchanged, the red line for cultivated land shall remain unbreaked, and the interests of farmers shall remain undamaged”. RCCCLM shall be carried out under the condition that the ownership of rural construction land belongs to the peasant group. In the process of RCCCLM, relevant rural collectively owned commercial construction land shall conform to the land use plan, and local governments cannot arbitrarily convert cultivated land into rural collectively owned commercial construction land. In addition, considering the property gains brought by RCCCLM, it is crucial to set up a fair and reasonable income distribution mechanism. In distributing the benefits of RCCCLM, a reasonable distribution ratio shall be formed among the country, local governments, village collectives and farmers to ensure that the benefits are fairly distributed among entities at all levels. The three bottom lines of the pilot reform of RCCCLM directly determine the basic value orientation of the RCCCLM policy.

- (2)

- Value pursuit. The RCCCLM policy was originally made to reverse the separate urban–rural construction land market and promote the trading of rural construction land and state-owned construction land in a unified market. Therefore, in implementing the RCCCLM policy, its value targets were set compared with state-owned construction land regarding four aspects: similar land, similar rights, similar price and similar responsibility. “Similar land” means that rural collectively owned commercial construction land should have the same or similar utilization methods as state-owned construction land. “Similar rights” means that rural collectively owned commercial construction land should have the same or similar rights as state-owned construction land, such as the right to disposition and the right to profit. “Similar price” means that RCCCLM requires the establishment of the same or similar price formation mechanism as the transaction of state-owned construction land. However, due to the difference in location, ownership and other factors of urban and rural construction land, it is inevitable that there will be a difference in the market price of urban and rural construction land. “Similar responsibility” means that in the process of RCCCLM, the entities involved need to bear corresponding responsibilities. For example, local governments need to assume responsibility for infrastructure construction and contract supervision of land plots for marketization.

- (3)

- Marketization process. The main processes of the reform of RCCCLM include rural collectives determining land plots for marketization, the township people’s government reviewing marketization matters, assessing the price of land plots for marketization, democratic decision making on marketization matters, formally submitting applications for marketization, organizing approval for marketization, organizing marketization transactions, paying land prices, paying relevant taxes and fees and registering for real estate.

- (4)

- Ultimate goal. Establishing a unified urban-rural construction land market can solve the problem of unbalanced urban and rural development, promote the coordinated development of urban and rural economy, achieve an effective allocation of resources and improve the overall efficiency of the national economy. However, due to the chronic segmentation of the urban and rural construction land market, the market value of rural construction land has not been effectively manifested, which seriously restricts the development of rural communities. The legal permission by national laws for marketization will undoubtedly promote the gradual unification of the market transaction rules of rural collectively owned commercial construction land and state-owned construction land, thus building a unified urban–rural construction land market.

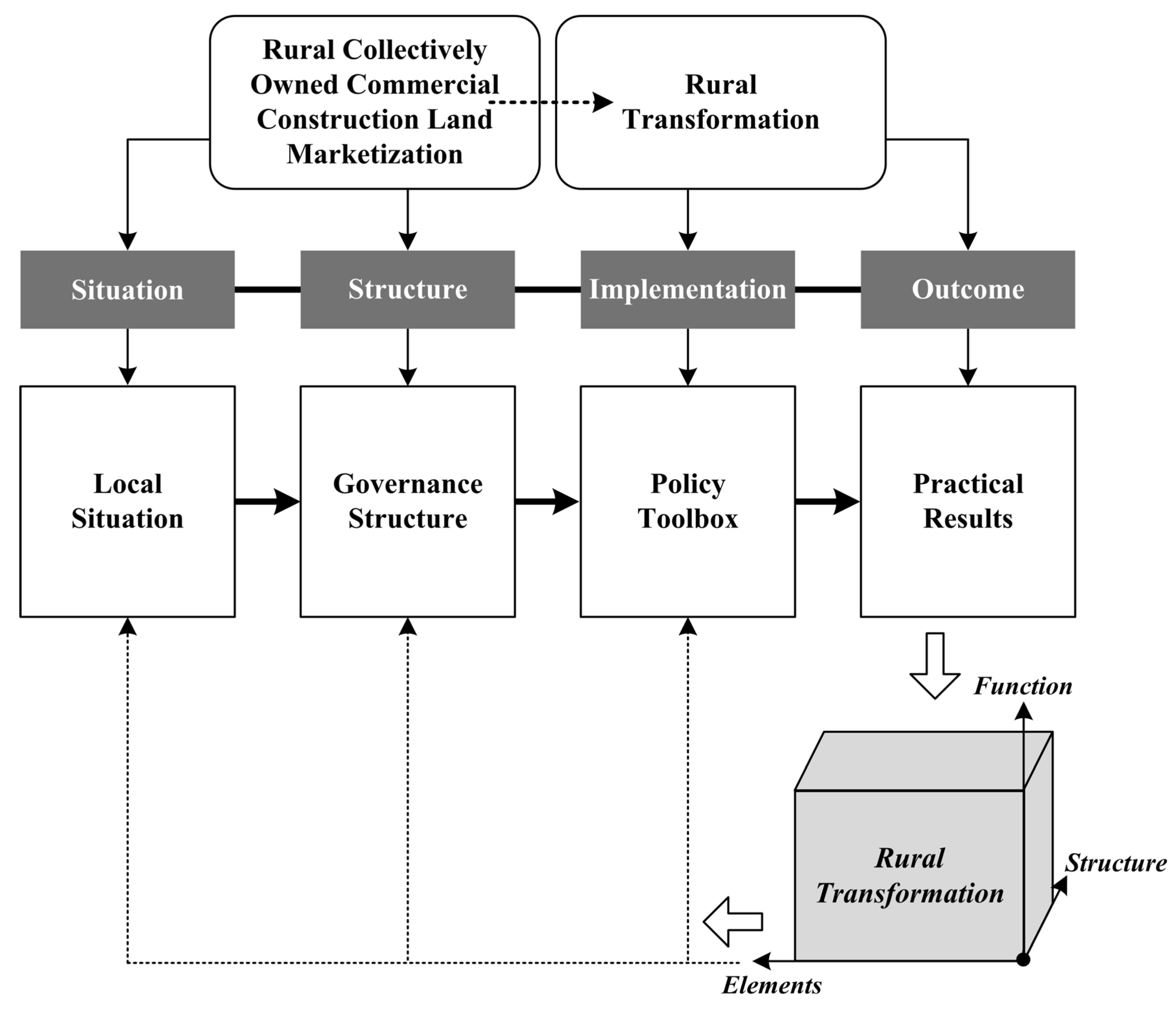

3. Theoretical Framework: Situation-Structure-Implementation-Outcome

3.1. Local Situation

3.2. Governance Structure

3.3. Policy Toolbox

3.4. Practical Results

4. Method, Data Generation and Empirical Cases

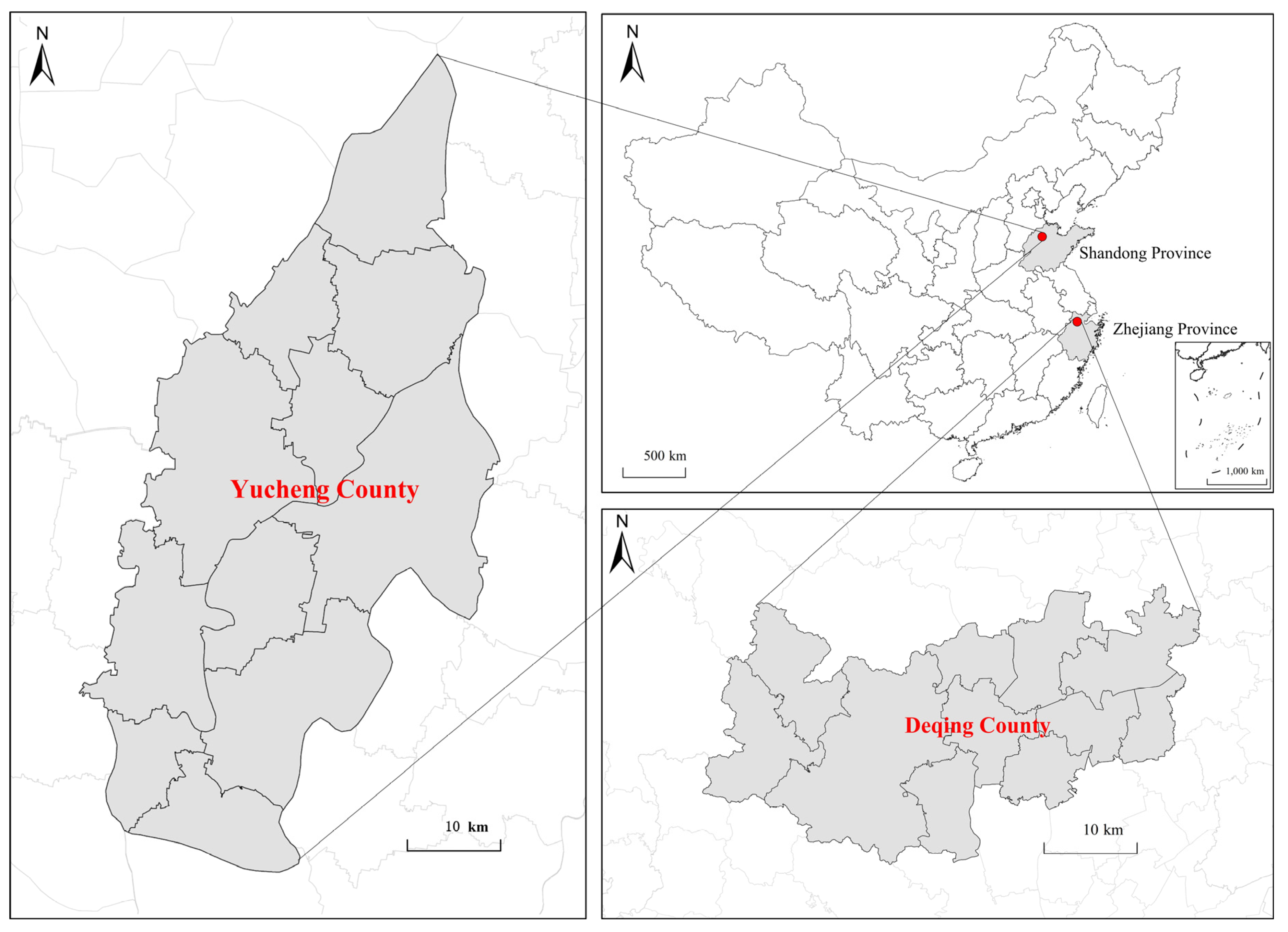

4.1. Case Selection

4.1.1. Being a Pioneer Pilot of RCCCLM

4.1.2. Regional Differences of Cases

4.2. Data and Analysis

- (1)

- In November 2018, September 2019 and April 2023, we conducted three rounds of field research on the reform of RCCCLM in Yucheng County. Under the coordination and arrangement of the Yucheng municipal government body, the present author conducted thematic exchanges with key subjects in the form of individual interviews or group interviews, and interviewed village cadres and villagers on the changes to the village after RCCCLM. The core topic of our research interview was “The path and mechanism of the impact of RCCCLM on rural transformation”. Our interviewees mainly included government officials, farmer collectives and business owners. The content of the interview may vary among different interviewees. Among them, we focused on how government officials formulate and implement policies for RCCCLM. For rural collectives, we focused on the distribution of profits from RCCCLM. For business owners, we focused on promoting the development of rural enterprises through the entry policy of RCCCLM. In addition, our investigation process involved three scales: county, town and village. In terms of a county-level survey, we tracked and investigated, in detail, various institutional arrangements and specific policies in Yucheng throughout the reform cycle. In terms of township-level and village-level surveys, we conducted research and interviews with relevant departments of the people’s governments of Fangsi Town and Lunzhen Town in Yucheng County, and selected Jiaji Village in Fangsi Town and Zhaozhuang New Village in Lunzhen Town for village-subject interviews.

- (2)

- In October 2018 and July 2021, we conducted two rounds of field research on the reform of RCCCLM in Yucheng County, including the Deqing Natural Resources and Planning Bureau, Moganshan People’s Government, Luoshe People’s Government, Xiantan Village and Dongheng Village. Our interviewees in Deqing County also included three types of subjects: government officials, farmer collectives and business owners. Our survey scale for Deqing County was also divided into three scales: county, town and village. Among them, at the county level, we focused on interviewing the Natural Resources Bureau of Deqing County. At the county level, we focused on collecting the policy documents and practices of RCCCLM in Deqing County. At the town level, we focused on conducting interviews with key government officials from the Moganshan Town People’s Government and the Luoshe Town People’s Government. The interview topics for government officials mainly focused on the formulation and implementation of policies for RCCCLM. At the village level, we conducted follow-up research on Xiantan Village in Moganshan Town and Dongheng Village in Luoshe Town and interviewed key market entrants in detail to understand the influencing process of RCCCLM on rural transformation. We conducted interviews with village officials and ordinary villagers on topics such as income distribution and spatial allocation.

4.3. Case Description

4.3.1. Yucheng Mode: The Case of Undertaking Industrial Transfer

4.3.2. Deqing Mode: The Case of Cooperative Operation among Multiple Villages

5. Results

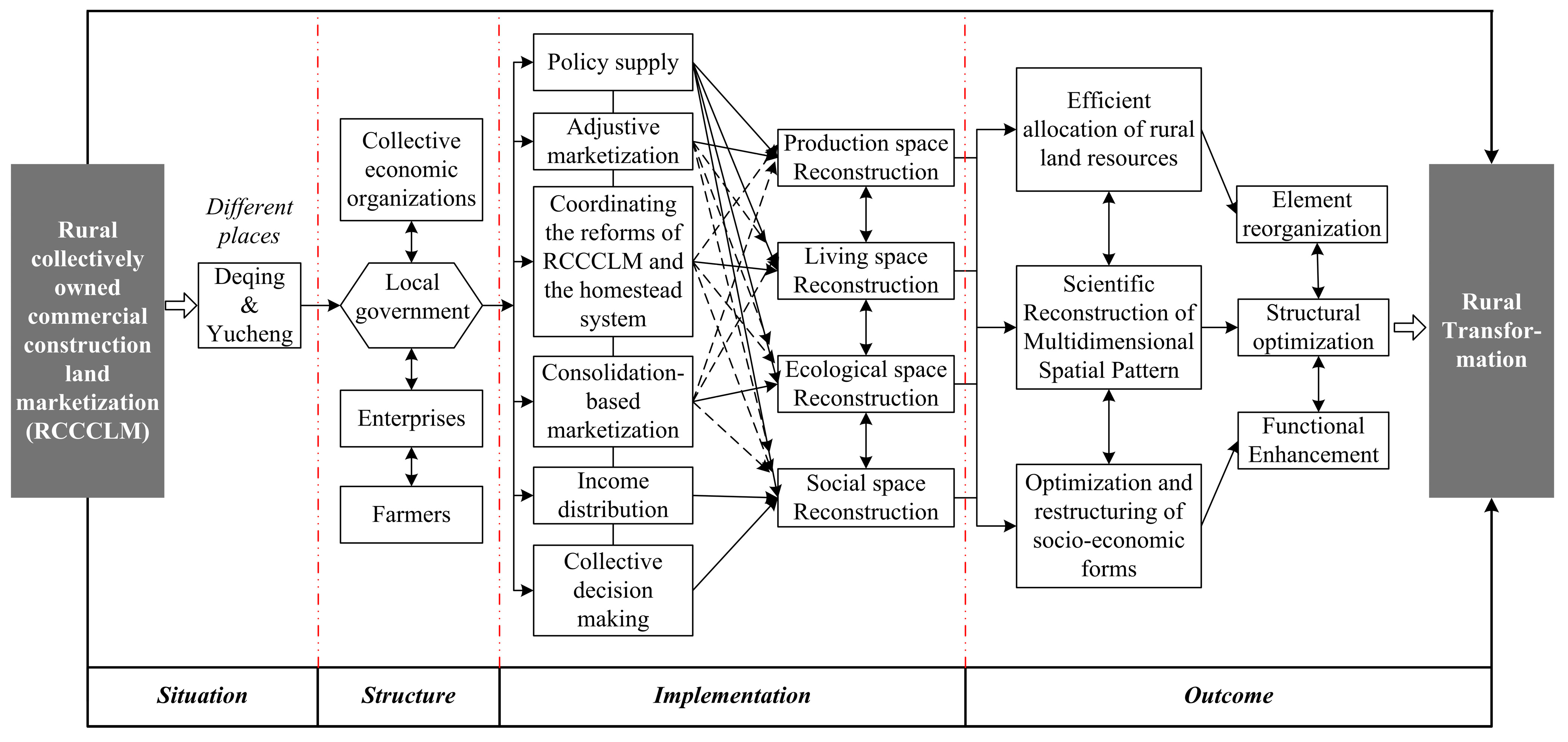

5.1. The Key Path of RCCCLM to Promote Rural Transformation

5.2. The Impact Mechanism of RCCCLM on Rural Transformation

- (1)

- The reform of RCCCLM and the improvement of the policy framework have improved the external policy environment for rural transformation. RCCCLM provides a new channel for the flow of land resources in rural areas as a policy, so that rural collectively owned land can be fully utilized and developed, which will increase the investment fields of the rural economy and promote the inflow and utilization of rural capital. RCCCLM will attract enterprises and capital into rural areas through market-oriented methods and promote rural transformation economically. The introduction of external investment can accelerate the upgrading and innovation of rural industries, improve the structure of rural economy and enhance the quality and efficiency of rural economic growth.

- (2)

- Adjustive marketization ensures the supply of land for industrial parks and promotes the reconstruction of rural production space, which is one of the important elements and means of rural transformation. Rural transformation aims to realize the transformation and upgrading of a rural economy from a traditional agricultural economy to a modern, diversified rural industrial economy, and the reconstruction of rural production space is a necessary means to achieve this goal. On the basis of ensuring the supply of land for rural industrial development, RCCCLM promotes the incorporation of social capital into the rural regional system, as well as the optimization and upgrading of rural industries.

- (3)

- Coordinating the reforms of RCCCLM and the homestead system promotes the reconstruction of living space. Hollow villages, typical of rural decay, are a special form of the degrading evolution of rural regional systems during rural socioeconomic transformation [29]. At present, in order to effectively solve this problem, homestead rectification is generally used in China to deal with the idle land and waste of land resources [30]. RCCCLM, as a policy tool, is often coordinated with the reform of the homestead system, which is conducive to the optimization of the rural living space layout, especially in the plains and the economically backward areas in China.

- (4)

- Consolidation-based marketization promotes rural environmental improvement and ecological space reconstruction. Rural ecological space reconstruction refers to the process of improving the quality of rural ecological environment and the utilization efficiency of ecological resources by adjusting and optimizing the rural land use pattern. Through the rectification of sporadic and scattered rural collectively owned commercial construction land, the re-utilization of land is realized in accordance with the requirements of “identifying land for cultivation, for forestry, and for construction according to reality”. In Yucheng’s reform of RCCCLM, 155.33 ha of rural collectively owned commercial construction land has been reclaimed as agricultural land. In addition, RCCCLM has helped promote the grouping and rectification of rural collectively owned land and reduce the degree of fragmentation of rural land use.

- (5)

- RCCCLM increases collective income and promotes the transformation of farmers’ livelihoods. The RCCCLM revenues can be used to improve rural infrastructure and public services, enhance the quality of life of rural residents and promote rural transformation. In addition, RCCCLM can attract more enterprises to rural areas and participate in the construction of factories, tourist attractions and other industrial projects, which will create a large number of jobs, provide a variety of job options, allow farmers to engage in more non-agricultural industries and achieve career transformation and employment growth.

- (6)

- RCCCLM highlights the dominant role of farmers and improves rural governance capabilities. Farmers’ democratic rights such as the rights to know, to vote and to participate have been well protected by incorporating the RCCCLM matters in village-level democratic management and holding villagers’ meetings to vote on RCCCLM decisions, the determination of the base price and the distribution of the proceeds of the transfer. RCCCLM strengthens the power of rural collective economic organizations to occupy, use, dispose of, benefit and distribute land, and it consolidates the dominant role of rural collective economic organizations in land ownership.

6. Discussion

6.1. The Relationship between RCCCLM and Land Consolidation

6.2. The Function of the RCCCLM in Different Stages of Rural Development

6.3. Policy Implication

6.4. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Woods, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J. Globalization, state intervention, local action and rural locality reconstitution—A case study from rural China. Habitat. Int. 2019, 93, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulickx, M.M.C.; Verburg, P.H.; Stoorvogel, J.J.; Kok, K.; Veldkamp, A. Mapping landscape services: A case study in a multifunctional rural landscape in The Netherlands. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 24, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y. Impact of Rural Tourism Operated by Retiree Farmers on Multifunctionality: Evidence from Chiba, Japan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 13, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Ives, C.D.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y. Modes and practices of rural vitalisation promoted by land consolidation in a rapidly urbanising China: A perspective of multifunctionality. Habitat. Int. 2022, 121, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation boosting poverty alleviation in China: Theory and practice. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Loopmans, M. Land dispossession, rural gentrification and displacement: Blurring the rural-urban boundary in Chengdu, China. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Ren, D. Impact of rural construction land marketization on rural development. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lyu, X.; Zhang, Q. Mechanisms and countermeasures of collective operational building Land entering the market to help promote rural revitalization. Rural Econ. 2022, 11, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, M.; Xu, H. How do Collective Operating Construction Land (COCL) Transactions affect rural residents’ property income? Evidence from rural Deqing County, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, K.; Yang, D. Will Rural Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketization Impact Local Governments’ Interest Distribution? Evidence from Mainland China. Land 2021, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zeng, L.; Chen, Y. Transaction of rural commercial collective-owned construction land increases farmers’ land property income:a case study of Pidu District, Chengdu City. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Conflict in informal rural construction land transfer practices in China: A case of Hubei. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, K.; Hammond, J.; Coleman, A.; Macinnes, J.; Mikelyte, R.; Croke, S.; Billings, J.; Bailey, S.; Allen, P. “Success” in policy piloting: Process, programs, and politics. Public Adm. 2021, 101, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettelt, S.; Williams, L.; Mays, N. National policy piloting as steering at a distance: The perspective of local implementers. Governance 2022, 35, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, S. From Local Experiments to National Policy: The Origins of China’s Distinctive Policy Process. China J. 2008, 59, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, P. Understanding the influence of values in complex systems-based approaches to public policy and management. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 980–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H.C. The Country in the Town: The Role of Real Estate Developers in the Construction of the Meaning of Place. J. Rural Stud. 1989, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielska, A.; Stańczuk-Gałwiaczek, M.; Sobolewska-Mikulska, K.; Mroczkowski, R. Implementation of the smart village concept based on selected spatial patterns–A case study of Mazowieckie Voivodeship in Poland. Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Tan, R.; Wei, X. The Chinese Story of Rural Land System Reform; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila, T.; Weible, C.M.; Olofsson, K.L.; Kagan, J.A.; You, J.; Yordy, J. The structure of environmental governance: How public policies connect and partition California’s oil and gas policy landscape. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 284, 112069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, S.J.; Bonnett, N. Climate change adaptation policy and practice: The role of agents, institutions and systems. Cities 2021, 108, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, W.; Fang, C.; Sun, H.; Lin, J. Actors and network in the marketization of rural collectively-owned commercial construction land (RCOCCL) in China: A pilot case of Langfa, Beijing. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callander, S.; Foarta, D.; Sugaya, T. The Dynamics of a Policy Outcome: Market Response and Bureaucratic Enforcement of a Policy Change. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Lyu, X.; Wang, B. The role of government in rural construction land marketization: Based on the content analysis of contract. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin, J.; Orum, A.; Sjoberg, G. A Case for Case Study; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, Y. Dynamic mechanism and models of regional rural development in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2008, 63, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Li, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J. Evolutionary process and mechanism of population hollowing out in rural villages in the farming-pastoral ecotone of Northern China: A case study of Yanchi County, Ningxia. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Long, H. Impacts of land consolidation on rural human–environment system in typical watershed of the Loess Plateau and implications for rural development policy. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Long, H.; Deng, W. Land consolidation: A comparative research between Europe and China. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, L.; Long, H. Theories and practices of comprehensive land consolidation in promoting multifunctional land use. Habitat. Int. 2023, 142, 102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, C.; Ye, Y. Marketization mechanism, model and path of comprehensive land consolidation and ecological restoration. J. China Agr. Univ. 2023, 28, 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Shen, D.; Gu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. Comprehensive land consolidation and multifunctional cultivated land in metropolis: The analysis based on the “situation-structure-implementation-outcome. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Wu, Y.; Choguill, C. Optimizing the rural comprehensive land consolidation in China based on the multiple roles of the rural collective organization. Habitat. Int. 2023, 132, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J. Comprehensive land consolidation as a development policy for rural vitalisation: Rural In Situ Urbanisation through semi socio-economic restructuring in Huai Town. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y. Basic logic, key issues and main relations of comprehensive land consolidation. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, L. Multifunctional rural development in China: Pattern, process and mechanism. Habitat. Int. 2022, 121, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yu, B.; Wang, M. Rural restruring and transformation: Western experience and its enlightenment to China. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 2833–2845. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Xu, D.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Z. Measuring residents’ perceptions of multifunctional land use in peri-urban areas of three Chinese megacities: Suggestions for governance from a demand perspective. Cities 2022, 126, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Loupa-Ramos, I.; Menezes, H.; Carvalho-Ribeiro, S.; Guiomar, N.; Pinto-Correia, T. Urban population looking for rural landscapes: Different appreciation patterns identified in Southern Europe. Land Use Policy 2016, 53, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, C.; Chen, J. Temporal evolution and spatial differentiation of rural territorial multifunctions and the influencing factors: The case of Jiangsu Province. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2015, 35, 845–851. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Tao, S.; Dai, B. Spatial accessibility of country parks in Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Whalley, J.; Fuzi, A.; Merrell, I.; Chapman, P.; Russell, E. Rural co-working: New network spaces and new opportunities for a smart countryside. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lu, F.; Duan, R.; Chen, L. Policy innovation, path model and guarantee mechanism of land overall planning for the integrated development of rural industries—Case analysis based on Daxing district of Beijing. China Soft. Sci. 2022, S1, 280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.S.; Xu, H. Producing an ideal village: Imagined rurality, tourism and rural gentrification in China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Rural transformation development mechanism and rural revitalization path from the perspective of actor-network: A case study of Dabin Village in the central mountainous area of Hainan Province. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Zhou, G. Evolution process and mechanism of rural gentrification based on actor-network theory: A case study of Panyang River of Bama County, Guangxi. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 77, 869–887. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, D.; Zhou, X.; Xie, S.; Lv, X.; Peng, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B. Paths and Mechanisms of Rural Transformation Promoted by Rural Collectively Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketization in China. Land 2024, 13, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13040416

Shen D, Zhou X, Xie S, Lv X, Peng W, Wang Y, Wang B. Paths and Mechanisms of Rural Transformation Promoted by Rural Collectively Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketization in China. Land. 2024; 13(4):416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13040416

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Duanshuai, Xiaoping Zhou, Shuai Xie, Xiao Lv, Wenlong Peng, Yanan Wang, and Baiyuan Wang. 2024. "Paths and Mechanisms of Rural Transformation Promoted by Rural Collectively Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketization in China" Land 13, no. 4: 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13040416

APA StyleShen, D., Zhou, X., Xie, S., Lv, X., Peng, W., Wang, Y., & Wang, B. (2024). Paths and Mechanisms of Rural Transformation Promoted by Rural Collectively Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketization in China. Land, 13(4), 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13040416