1. Introduction

Water, and its interconnections with land, has become one of the biggest targets of environmental conflicts in the world, and in Brazil in particular [

1], which can take a variety of forms, from growing social differentiation within the city and in the countryside. In terms of water consumption (generally, those who do not have access to it are the poorest and live on the outskirts of large cities and/or in the countryside), conflicts revolve around the prioritization of agricultural or industrial use, construction of new reservoirs or dams, sanitation, and urban supply, as well as large projects to transport water. The privatization of the São Paulo water and sewage service (SABESP) in July 2024 demonstrates how the commodification and extraction of income from nature continue to be central to political and economic disputes in contemporary Brazil [

2].

Such conflicts are accentuated as large water projects, including dams, reservoirs, hydroelectric plants, etc., are undertaken in territories and their effects are distributed unequally among social groups and spatial locations [

3]. The consequences are not given, nor are they neutral, but are socially produced and politically constructed, which are projected within the national and global capitalist logic. Therefore, the problems surrounding large water projects and programs are not only part of the Brazilian reality; on the contrary, “globally, mega-hydraulic projects have become deeply controversial” [

4] (p. 1). This can be observed in different parts of the world, for example, in Canada [

5], in Spain [

6], in India [

7], in Ecuador [

8], in the United Kingdom [

9] and in Brazil [

10].

Although these various projects have different objectives and are implemented in different geographic contexts, they all involve multiple stakeholders and are designed based on a development model narrowly based on economic growth and the privatization of nature, often disregarding the life trajectories of the people affected and other alternative forms of socio-spatial organization [

11]. The Brazilian experience is also highly relevant, since the national government implemented the largest water infrastructure project in the country in the Northeast region, historically marked by fierce conflicts over water and land, in addition to the concentration of water sources on large private properties [

12]. It is crucial to emphasize the profound interconnections between access to water and access to land in the semi-arid inland of the Brazilian Northeast. This is a region with serious levels of poverty and political-economic exclusion, which is a process of marginalization associated with authoritarian policies and the appropriation of land and water by regional elites. The value and the ability to cultivate the land are directly associated with the availability of water, and those who control water control land and politics [

13,

14,

15].

Our focus is on the profound interconnections between access to water and access to land in the São Francisco Valley, which is the most important river basin in the region from an economic, social, and land management perspective. It has been recently the object of an inter-basin transfers project aiming to pump water from the São Francisco River to other Northeast region catchments. The São Francisco is the fourth largest river in the country and in South America, with a length of 2863 kilometres, passing through five states and 521 municipalities. Its river basin has an area of 641,000 square kilometres and is called the river of national integration [

16]. However, despite the appearance of resource availability (water and land, but also hydro-energy), there have been major disputes and conflicts within the river basin and across the Northeast.

The São Francisco River Integration Project (PISF—Projeto de Integração do Rio São Francisco, in Portuguese), implemented since 2007 and currently in its final stages of construction work, aims to transfer (divert) water from the river of the same name and interconnect it with other river basins located in the northern states of Paraíba (PB), Pernambuco (PE), Rio Grande do Norte (RN), and Ceará (CE). This water project is the responsibility of the current Ministry of Regional Development (MDR), formerly the Ministry of National Integration (MIN), and its main objective is to ensure a regular water supply for approximately 12 million inhabitants in the Agreste and Sertão [backland] segments of the aforementioned states [

17]. The project collects water at two points on the São Francisco River, and the water flows along two main axes, east and north, covering 477 kilometres, in addition to several associated axes (these are secondary works, the responsibility of the states), for integration with other basins in the northern Northeast.

A critical alliance was formed in recent years between social organizations, environmental activists, social movements, and peasants against the implementation of PISF [

18,

19]; however, it was not enough to prevent the adoption of the project. The main reason was that technological and engineering knowledge, evolving together with development narratives, power relations, and institutional arrangements, created a strong epistemological barrier that devalued or delegitimized local and ecological knowledge. Grassroots mobilization against the PISF ended up not being sufficient to prevent such a large project from being executed (as discussed by Fox and Sneddon [

20]). In that context, the main contribution of this paper is to reflect on the political ecology of water and land in relation to the long legacy of socio-spatial exclusion and a critical assessment of the recent implementation of the PISF by the Brazilian government. In addition, we critically reflect on the perpetuation of conflicts over water and land for the most vulnerable people, even though the water project has been in operation since 2017.

Construction work on the project began in 2007 and its completion, which was scheduled for December 2018, has been delayed at times and is currently in the final stages. Therefore, it is observed that in territories where water projects are implemented, such as the PISF, severe transformations are caused, producing hydrosocial territories [

21,

22]. In these, water and territory, water flows, and biophysical and sociopolitical properties are intertwined based on socionatural interactions, composing a hydrosocial water cycle. In this sense, this research aims to analyze the territorial implications produced by the new hydrosocial cycle constituted by the implementation of the PISF in the Brazilian Northeast. The emphasis on hydrosocial territories is relevant to critically analyze the socio-spatial configurations of people, institutions, access to land and water, technological flows, and the biophysical environment that revolve around the control of resources by different social groups and the various commitments of the state apparatus.

Although justified by the possibility of water security in the region, the water project resulted in significantly negative issues, including environmental risks, forced resettlement, and disorderly management of watercourses [

23]. As demonstrated below, despite an official discourse of distributing water to the entire population, the project had a technocratic conception and focused on engineering works instead of considering the specific socio-natural conditions and, in particular, the political and agrarian inequalities that have marked the region for centuries. Unfortunately, this is not only a Brazilian reality; in general, the development of large-scale water infrastructure generates profound social and environmental impacts, even more so because the burdens and benefits are distributed unequally among local population groups [

4]. The research advances the understanding of how large water projects, conceived in contexts historically rooted in complex relations, end up resulting in hydrosocial territories that remove water from its sociocultural and ecological functions, instead reproducing water injustices, responsible for the emergence of environmental conflicts. Furthermore, it demonstrates how the governance of common goods, especially water, is directly related to a global geopolitics of capitalism, which defines its forms of access and allocation.

The article is structured in four sections, in addition to this introductory section. In the following section, we discuss the socio-natural and territorial implications of implementing water projects and then present the methodological procedures for conducting the research. In the fourth section, we analyze and discuss the hydrosocial territories fostered by the new hydrosocial cycle resulting from the implementation of the PISF in the Brazilian Northeast, situating the debate historically in addition to presenting characteristics of the water project and its socio-natural implications. In the last section, we present the main conclusions, in particular, the need to understand the deeply politicized basis of land and water allocation, management, and conservation, as well as the insertion of large-scale projects in complex hydrosocial networks formed between the state and the asymmetric segments of society.

2. Socio-Natural and Territorial Implications in the Implementation of a New Hydrosocial Cycle

From the 1980s onward, the mercantile logic of water gained strong momentum and was anchored in broader neoliberalization processes related to the political and economic power essential for capital accumulation. From a capitalism based on industrial production and circulation of goods, a model cantered on rent extraction and financial speculation began to prevail. This transformed social relations and control over water, in addition to reconfiguring water-society relations in ways that further consolidated the economic and political power that sustains them [

4,

24]. This political-institutional trend was reflected in constitutional changes implemented in several Latin American countries [

25], as well as in the development of large water projects, especially in the Global South, implying profound sociotechnical, ecological, territorial, and cultural transformations on different scales [

8].

Water is primarily a political issue [

26,

27], and changes in the forms of management and use need to integrate social, cultural, ecological, and economic aspects. In other words, the hydrological cycle has never been something purely natural but ontologically socio-natural. Increasingly, the involvement of water with other ecological processes and with society is recognized as an integral part of water cycle management, which means the need for an analysis beyond technical and hydrological issues [

28].

Our investigation is based on the understanding that water circulation produces a physical geography and a material landscape, as well as a symbolic and cultural landscape of power, that Erik Swyngedouw systematized as the hydrosocial cycle, which is a theoretical-methodological framework that allows us to understand water not only in its materiality as a water resource but in the relationship between water and society [

26]. Under the influence of authors Karl Marx, Henri Lefebvre, and David Harvey, Swyngedouw deepened the studies of urbanization processes and water configuration carried out in Guayaquil, Ecuador, and proposed the hydrosocial cycle as an approach to think about water flows beyond hydrological cycles. For the author, water circulation is a combined physical and social process, like a hybrid flow, in which nature and society merge inseparably. Swyngedouw’s proposal is based on the conception that “the “world” is a process of perpetual metabolism in which social and natural processes combine in a process of historical-geographical production of socio-nature”, whose interaction “incorporates highly contradictory but inseparable chemical, physical, social, economic, political, and cultural processes” [

26] (p. 28).

It is pertinent to mention that, following Hegelian dialectics, socio-natural production is a hybrid process in which none of the component parts is reducible to the other, but its constitution arises from the multiple dialectical relations resulting from historical and geographical processes through which such relations are formed. In particular, “water is a hybrid element” that captures and incorporates processes that are simultaneously material, discursive, and symbolic [

26] (p. 28) and are intertwined by unequal relations and power struggles. Any “change in the physical presence of water, in institutional arrangements, in the discursive constructions of water, or in the uses to which water is directed, has the potential to shift socioeconomic constellations towards a different set of relations” [

28] (p. 174).

The socio-natural relations intertwined with the water cycle do not occur in a neutral environment, and it is necessary to pay special attention to the power relations, whether material or discursive, economic, political, and/or cultural, through which the processes occur [

29]. It is these power geometries and the social actors (members of the various social and political groups of society) who execute them that, ultimately, shape the flows, defining who will have access to and control of water and who will be excluded [

30].

Hence, water, in addition to having its physical-chemical characteristics, is covered by vast significance in the social, cultural, and religious fields [

7,

31], so that for many people, human and water relationships involve multiple human and non-human actors, all involved in fluid processes in which they interact dynamically [

32,

33]. This reinforces the importance of the hydrosocial perspective, as it deliberately addresses the social and political nature of water [

26,

34,

35].

Different studies [

21,

26,

28,

30,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39] point out how the hydrosocial cycle is a conceptual and analytical tool capable of revealing sociopolitical and economic relations that permeate spatial processes of different orders. These studies highlight particular factors such as historical, technological, and infrastructural circumstances and sociopolitical conditions as fundamental to understanding water flows, access, and distribution in different geographical contexts, for example, in Chile [

34,

37,

39], India [

30], the United States [

40] and Brazil [

41].

Linton and Budds [

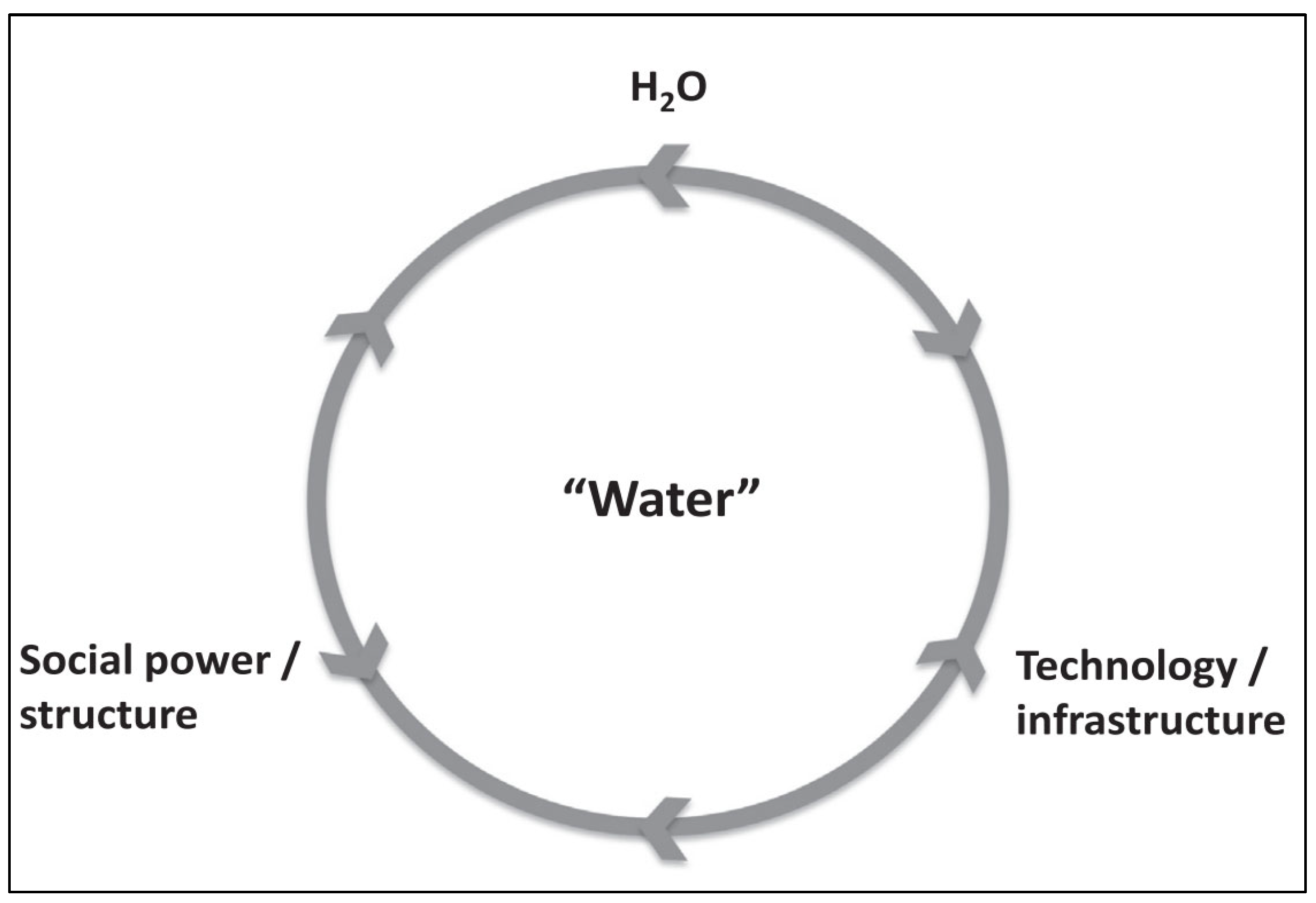

28], in turn, advanced the theoretical discussion and employed a relational-dialectical approach to conceptualizing the hydrosocial cycle as a socio-natural process by which water and society make and remake themselves in space and time. The authors argue that unravelling this historical and geographical process of making and remaking offers analytical insights into the social construction and production of water, the ways in which it is known, and the power relations that are embedded in hydrosocial change. In other words, the cycle “relates a variety of heterogeneous entities, including social power and governance structures, technologies, infrastructure, policies, and water itself” [

28] (p. 176), as can be seen in

Figure 1.

The hydrosocial cycle embodies the essential sociopolitical and socioeconomic processes through which water becomes and reveals itself as socionatural, shaped by social, physical, and technological drivers. Rather than a natural cycle of water flow, the hydrosocial cycle seeks to highlight the historical, political, and social factors that shape the biochemical circulation of water (H

2O) through robust infrastructures, and its flow and management are intertwined with broader structural issues of power and capital accumulation [

42]. This is materialized, for example, through the relationships between hegemonic public and private actors in the implementation of large hydraulic projects and dams in territories [

43].

We draw attention to the distinction that the above political ecology authors make between “H

2O” and “Water”. The biochemical materiality of water is represented by its formula and “represents the idea of the role of water agency in hydrosocial relations”, that is, hydrological processes have their place in the hydrosocial cycle not only as material flows of water but also in the process of social production and organization [

42]. In other words, water is not inert in the process of social production but plays an important role in social formations [

44].

In turn, “Water” can be understood as the result of H

2O and the social production in which it is constituted, named as hydrosocial relations. Therefore, it can be characterized by a “discourse, construction, idea, or particular representation of water” that belongs to any social actor or set of actors, occurring as a moment in the hydrosocial cycle. Therefore, each “Water” incorporates the socio-natural processes by which it is produced [

28] (p. 177). However, although the authors make these reservations, it is pertinent to emphasize that H

2O does not exist at all [

29]. Water or “hydraulic environments are always socio-physical constructions actively and historically produced based on social content and physical-environmental qualities” [

36] (p. 56).

In summary, the authors understand that the hydrosocial cycle is a “dialectical process by which water and society are made and remade as a historical process that relates water and society internally” [

28] (p. 175). Water and society are not related as pre-established entities, nor do they emerge from these relationships as independent entities, but in the sociohistorical process. Therefore, “the hydrosocial cycle reveals the potential to change the constitution of water, involving it in different ways, showing at the same time how this produces changes in social relations” [

42] (p. 116) and also territorial ones [

45].

Therefore, such changes are configured as territorial transformations since water flows through systems that are social, and “collaboration and disputes between public and private agents have a direct impact on the biophysical properties of water and, crucially, on the territory produced from socio-natural interactions” [

46] (p. 127). From this perspective, Strang draws attention to the intertwined relationship between water, land, and territory, in which changes in one element have implications for the others and vice versa, and the processes of commodifying and enclosing land and water are increasingly intense throughout the world [

32].

This intensification of land and water use has several ecological and social implications, such as the destruction of forests and wetlands, devastating the resources needed for subsistence economies; industrialized agriculture pushes populations from rural areas to cities; mining devastates indigenous landscapes ecologically, economically, and cosmologically; and the excessive use of water by productive activities has generated disputes on different scales [

7,

32,

33]. In addition, large water projects can excessively modify the territories and, consequently, the water flows of a given region or country.

The analysis of territorial transformations in the configuration of hydrosocial cycles can reveal the ways in which water circulates, who will or will not have access, as well as the sociopolitical relations involved in this process. This occurs because “territorial policy finds expression in the encounters of diverse actors with divergent spatial and political-geographical interests. Their projections and strategies for constructing territory are in dispute, overlap, and align to strengthen specific claims for water control” [

21] (p. 6). Therefore, the hydrosocial territory is defined as the

[…] materialization of a spatially linked multi-scalar network in which humans, water flows, ecological relations, hydraulic infrastructure, financial means, legal-administrative arrangements, and cultural institutions and practices are interactively defined, aligned, and mobilized […]. The networks of relations that constitute hydrosocial territories can be called “hydrosocial networks” [

21] (p. 2, 4).

Hydrosocial territories are spatial configurations resulting from the interaction of people, institutions, water flows, hydraulic technology, and the biophysical environment that revolve around the control of water, forming what the authors call hydrosocial networks. Thus, hydrosocial territories are simultaneously biophysical and cultural; hydrological and hydraulic; material and political. The networks are intentionally and recursively shaped around the control and use of water. Consequently, they interfere in the way in which hydrosocial relations will be given and, consequently, in the management of river basins, water flows, and systems of access and use of water by different social actors [

21,

22].

The hydrosocial cycle can result in changes and provoke socio-spatial reconfigurations, which typically transform social ties, spaces, and borders experienced by social actors [

21]. This occurs because “the notion of ‘territory’ combines power, space, and identity, expressing the importance of the processes through which people incorporate social meanings into landscapes, locate identity in place, and develop affective connections with their lands” [

32] (p. 317). Therefore, transformations in territories can bring disruption and suffering to the people territorialized in these spaces since the territories are loaded with histories, affective ties, and resistance. This becomes even greater when people are displaced to other territories, the so-called deterritorialization processes [

47,

48].

Such processes are never fixed but highly dynamic, and although the impacts of deterritorialization and the rearrangement of hydrosocial territories may be felt primarily by individuals and organizations at the local level, the processes dynamically interconnect multiple scales [

22]. It is important to remember that these different processes of territorialization and “projections of how these territories, their waters, and people are organized can, in general, empower certain groups of actors while disempowering others and offer arenas for claim-making and contestation” [

22] (p. 117), giving rise to environmental conflicts.

Most territorial and water control struggles are rooted in how water management practices undermine access to, transform, incorporate, and/or reorder existing local forms of collective self-governance and territorial autonomy. Therefore, resistance and political organization are essential to ensure that traditional communities and territories are not disrupted so that rural communities can continually produce their own forms of development. This is particularly important in a context where governments in the region depend on extractivism and the exploitation of indigenous territories [

33].

Unlike conventional definitions, socio-spatial reconfigurations are interpreted here as the production of historical-geographical configurations based on engagements between various social actors and different dynamics of water control, which paves the way for the consolidation of a landscape full of socio-spatial inequalities [

46]. This is possible because “politically speaking, territory is the socio-materially constituted and geographically delineated organization and expression of and for the exercise of political power” [

22] (p. 117). Thus, understanding the hydrosocial territories involved in the hydrosocial cycle can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the social relations and developments that forms of water management and control can produce in society, especially in geographic contexts such as the Brazilian Northeast, historically marked by the concentration of water sources and land conflicts.

3. Research Methodological Procedures

The research followed a qualitative approach and ethnographic design [

49]. This research began with a literature review of the applications of the hydrosocial framework to analyze water-society relations in various sociocultural, political, and economic contexts. The literature reviewed and discussed in the previous section spanned a multitude of spatial, cultural, and political settings, providing a foundation for understanding the applications of the conceptual framework fundamental to the research.

The research was outlined in three different fields of analysis and interpretation, namely: (i) the water project itself, with a focus on observing the new hydrosocial cycle and new hydrosocial territories promoted; (ii) the rural communities directly affected by the project, which were relocated to rural villages located along the PISF; and (iii) institutional actors responsible for the design, regulation, and operation of the water project.

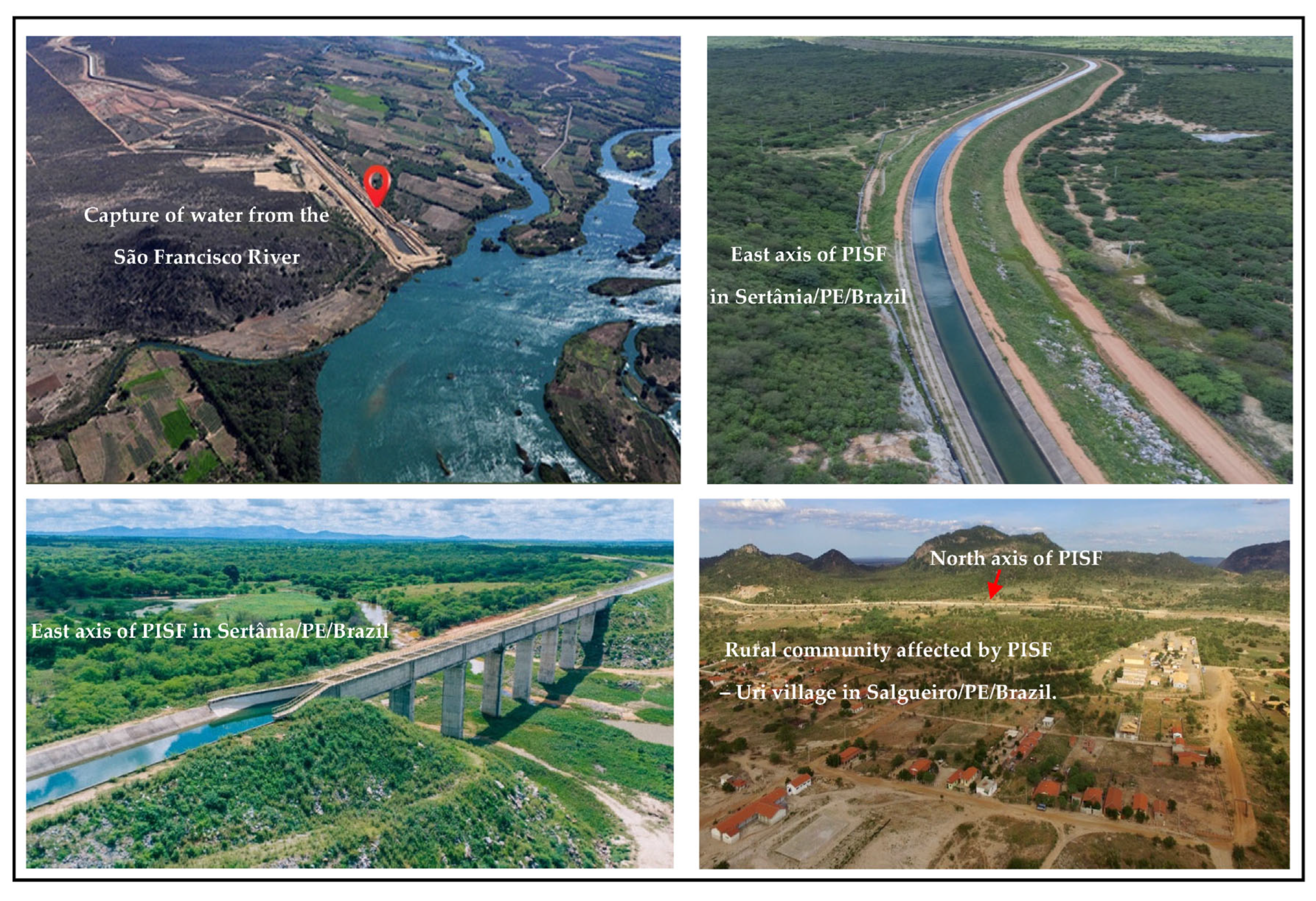

From this perspective, data collection was carried out in four stages. The first took place in January 2018, characterizing the exploratory phase, whose focus was to learn about the water project, starting on the eastern axis in Monteiro (Paraíba) to Custódia (Pernambuco), then the northern axis, starting in Cabrobó (Pernambuco) to Jati (Ceará). These visits were guided by technicians linked to the PISFs entrepreneurial agency, the then Ministry of National Integration. In addition, we visited some rural communities affected by the project and relocated to rural villages located in its surroundings. It is worth noting that this stage did not include any type of more specific data collection instrument, only socialization and fruitful exchanges with some stakeholders, which facilitated the approach for the next stage of the research.

The second stage took place between January and March 2019, with the aim of getting to know and exploring the daily lives of families affected by the water project and reterritorialized in rural villages. This stage involved continuous experience in four of the total of 18 existing rural villages, one located in the municipality of Monteiro, another in Sertânia (east axis), and the other two in Salgueiro (north axis), as shown in

Figure 2. This experience included staying in the homes of some families in the villages, enabling the author to participate in the daily life of the community. This allowed for continuous monitoring of the community’s daily life, characterizing the ethnographic work [

49].

The fieldwork included participation in several meetings of the associations of each community, in addition to oral history interviews [

50] with the families, seeking to learn about the life stories of the affected people, what their lives were like before the project, and to understand historically the process of reterritorialization in the village within the context of the lives of the affected actors, as well as their forms of access to water. In each approach to the families, after the initial greetings and authorization to participate in the research and recording of the semi-structured interview, through signing the informed consent form or recording of acceptance, the interviews began and resulted in 48 interviews conducted. All were recorded with prior authorization from the individuals and in accordance with a clear scientific ethics protocol. The respondents were selected according to location, that is, those who resided in the rural villages surveyed and agreed to participate in the research, gender, age, and income level, in an attempt to capture a diversity of perspectives and opinions.

The third stage, in turn, was carried out in April 2024 with a return to two rural communities visited in the previous stage: the rural village of Lafayette, located in the municipality of Monteiro (Paraíba), and the rural village of Salão, located in the municipality of Sertânia (Pernambuco). The focus of this stage was to socialize the results of the research as well as to update the data in order to understand whether the conflicting reality of access to water had undergone any changes. In addition to the villages mentioned, we visited some families living within a range of up to five kilometres from the PISF. This stage also included semi-structured interviews, resulting in 12 interviews.

The last stage was carried out in May 2024, with semi-structured interviews with institutional actors linked to the federal government located in Brasília (the national capital). Representatives of the Ministry of National Integration and Regional Development (PISFs entrepreneurial body), the National Water and Basic Sanitation Agency (PISFs regulatory body), and the São Francisco and Parnaíba Valleys Development Company—CODEVASF (PISFs operating body) were specifically interviewed in order to understand the nuances of the water project and the management of the new water flows that bathe the northern portion of the Northeast. The selection of these bodies was based on the competence of each one regarding the execution of the work, regulation, and operation of the project, respectively.

In addition to the interviews, several observations were made in the field diary, and, at the end of each day, the events and observations relevant to them were recorded. In addition, photographs and videos were taken in the rural communities with the prior authorization of the people, in addition to a documentary search seeking to collect data on the water project, its management, as well as histories related to the progress of the rural villages after the reterritorialization of the families. It is pertinent to mention that the last two stages of data collection are part of an ongoing research project within the scope of the universal call for proposals of the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Regarding the systematization and transcription of data, we used the NVivo® software (version 13/R1/2020), although at times we opted for manual systematization. The analysis and interpretation of data were carried out through interpretative analysis anchored in the adopted theoretical framework, seeking to identify both what was homogeneous and what differentiated the narratives, in addition to the systematic analysis of the documents and the field diary.

4. Hydrosocial Territories Promoted from the New Hydrosocial Cycle Resulting from the Implementation of PISF in the Brazilian Northeast

Considering that large projects are neither fixed nor neutral, it is essential to understand how the PISF is entangled in the sociopolitical relations around water historically in Northeast Brazil in order to understand how new water flows materialize in the region. First, it is important to mention that the semi-arid climate presents high temperatures, around 30 °C for most of the year, resulting in low air humidity and long periods of drought with scarce and poorly distributed rainfall [

51].

Associated with these climatic characteristics, the region was historically conceived by an oligarchic elite, originating from the colonial period from large sugar plantation estates, associated with an unequal land inheritance [

15]. This elite dominated the political scene and the public machine to such an extent that it determined regional and local politics in order to maintain the power of the bourgeoisie and social contradictions. In this way, the large landowners ruled with practically no regulation that limits their interests and operation [

52]. With the end of the sugar cycle and the focus of the national political elite on developing the region that is now the Southeast, the Northeast began to decline and perpetuate its underdevelopment [

53].

This reality was reflected over time, and periods of severe drought contributed to exacerbating the social vulnerability of families since the main means of survival were subsistence family farming and animal husbandry [

54,

55]. To mitigate the effects of adverse weather events, several projects were implemented and institutions were created (see

Figure 3), such as the Superintendence of Studies and Works Against the Effects of Drought, created in 1906, designed to carry out studies and dam and well drilling services in the region. Later, in 1909, the Inspectorate of Works Against Droughts (IOCS) was created, and in 1945 the National Department of Works Against Droughts (DNOCS) was created, responsible for the construction of several reservoirs on private lands of regional colonels, leaving the population at the mercy of large landowners for water distribution [

54]. For more historical information on the topic, see Santos [

12,

41].

It is important to note that drought periods are not limited to those highlighted in

Figure 2, but are those that resulted in larger social problems, such as the number of deaths, and high migration, and that mobilized some action by the government. Regarding the classification of the measures taken, emergency measures were those that occurred only during drought periods; drought-fighting measures included structural projects implemented, mainly on private land; and finally, those related to coexistence with the semi-arid region, which were social technologies created by the communities themselves to store water [

12]. Therefore, the empirical evidence accumulated about those different periods demonstrates that the lack of access to water was, and still is, treated as a merely technical issue and a matter of physical availability of water; that is, the focus is on the physical scarcity of water and not on the political relations surrounding it. This was the basis for decision-making that defined both the specific agencies for the region and infrastructure projects such as the PISF, demonstrating a reductionist perception of the socio-natural complexity surrounding water in the Northeast.

It is in this sociopolitical context that the São Francisco River transposition project took shape over time. It is a project planned initially in the final period of the imperial government (1822 to 1889) when a commission was created to study practical means of supplying water during droughts, with the construction of a canal connecting the São Francisco River to the Jaguaribe River (Ceará) being one of the proposals. “For a variety of reasons, including technical difficulties, mismanagement, lack of funds, and sheer lack of government interest, most of these proposals could not go beyond the planning stage” [

15] (p. 6). Years later, during the government of João Figueiredo (1979–1985), the transposition was once again pointed out as a solution to the problems of droughts. Later, during the 1990s, it marked a new moment in which the discussion about the project was resumed, but once again it did not receive attention and was shelved. It was only during Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s first term (2003–2006) that PISF returned to the center of the debate and new studies were carried out. Despite several legal obstacles, many controversies, and resistance from social groups opposed to the project, in September 2005, the federal government signed the Commitment Term with representatives of the receiving states (Paraíba, Pernambuco, Ceará, and Rio Grande do Norte), and during the second term (2007–2010), it became a concrete reality [

12].

It can be seen from the above that the plan to interconnect the São Francisco with other river basins was a recurrent promise that various politicians repeated over more than 150 years. It was only with the election of Lula da Silva in 2002 that it became possible to allocate financial resources, technological know-how, and political support. The design of the PISF was conceived during a popular government, originating from Pernambuco (one of the receiving states and, not by coincidence, the birthplace of President Lula) and from the unionist struggle, based on a transformative and regional development rhetoric, with the promise of serving 12 million people [

56]. To this end, according to data from interview 1, the transposition project captures water at two points on the São Francisco River to integrate with other basins in the Northeast through an infrastructure that includes canals, tunnels, and aqueducts, characterizing the new hydrosocial cycle of the PISF with an extension of 477 kilometres of main axes. The project is structured on two axes, the eastern one, with water capture in Floresta (Pernambuco) and continuing to Monteiro (Pernambuco), comprising 217 kilometres, and the northern one, from Cabrobó (Pernambuco) to Cajazeiras (Paraíba), with an extension of 260 kilometres. In addition to the main axes, there are associates capable of distributing the water flows in the territories. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Regional Development, the planned volume of water to be transferred through the various axes is 219 m

3/s (2024 data, subject to further adjustments).

It is clear that the implementation of an undertaking of this magnitude resulted in several socio-natural damages. Interview 2 revealed that several environmental programs were defined to minimize such effects, and especially for the affected and displaced families, the General Coordination of Environmental Programs developed an environmental program that contemplated four forms of reterritorialization, namely: (i) Resettlement in remaining areas of their territory; (ii) Self-resettlement in another rural territory with the compensation received; (iii) Resettlement in urban areas; and (iv) Rural collective resettlement, which consisted of rural villages built throughout the water project. The last option involved 845 families, who were directly affected and were relocated to the eighteen rural villages built along the PISF. However, more families were indirectly affected, but there are no clear statistics about the exact number of families and people impacted.

We draw attention to the hydrosocial territories resulting from the project, favouring the rupture of socio-community relations, changes in environmental dynamics resulting from the process of socio-spatial reorganization of the affected actors, and severe damage that altered their ways of life, often passed down from generation to generation.

For the farmer living in Vila Negreiros, “it was very difficult, and it is difficult. I won’t get used to it very easily [although she has lived in the village for nine years]. What are you going to do now? 32 years of marriage, most of that time spent there. I miss it a lot” (Excerpt from interview: Farmer I, Vila Negreiros, January/2019). Another report presents the difficulties in leaving the territory:

I was very sad when it was time to leave, I was devastated. For many years, the children were all born in that house, and we left everything behind and we had outgrown the house and imagined that we would come to a small house. I left with a heavy heart. I would cry a little bit! I kept crying, I missed it [interviewee gets emotional] (Excerpt from interview: Farmer B, Vila Lafayette, February/2019).

To analyze the territorial implications of the hydrosocial cycle encompassed by the PISF, we used a theoretical framework that allowed us to analyze water not only in its biochemical materiality and hydrological flow but also beyond that, considering that water is manipulated by social actors and institutions, and broader social relations related to water are developed throughout its flows [

39]. Specifically regarding the actors involved in the PISF, data from interview 3 indicate that the Ministry of Integration and Regional Development (MIDR) is the entrepreneurial agency responsible for implementing the project, the National Water Agency is the regulatory agency, and CODEVASF is the federal operator. In addition, the State Secretariats of Water Resources of the four states receiving the water are involved, as are the São Francisco River Basin Committee and the users. The latter are classified into large users, which are the state water companies responsible for collecting, treating, and making water available to the municipalities of each state, and small users, which include rural villages and communities surrounding the PISF.

Therefore, the governance of the project should consider all the actors mentioned above. However, the General Coordinator of Contracts and Budgets (Interview 3) mentioned that only formal institutional actors participate in the project’s Management Board, disregarding popular participation in decision-making regarding the new water flows that flood the northern part of the Northeast, but that its territories remain dry. In this context, it is relevant to mention the asymmetries of power across the various urban and rural groups that characterize the relationships between these various social actors and the concentration of decision-making, which goes against the recommendations of the Brazilian National Water Resources Policy (PNRH) (Law No. 9433, of 8 January 1997). Therefore, the research made it possible to elucidate the political processes and power relations underlying the forms of use and appropriation of water in a region that has historically been characterized by the concentration of sources and decisions around water, such as the Northeast region.

Since water flows through systems and landscapes that are essentially hydrosocial, the research elucidates that the hydrosocial circulation of water in the PISF followed a series of social demands, practices, and discourses of hegemonic public and private actors, shaping the territory. Although the federal government conceived the project with the justification of universalizing access to water, data from this research show, and other studies corroborate, that the conflicts were intense and that economic sectors, mainly agribusiness, are the ones benefiting from the water security resulting from the project [

23,

57,

58]. This occurs because the State, commonly in partnership with the private sector, plays “the most decisive role in the allocation and use of water and, in this process, creates situations and spaces of abundance or scarcity inscribed in the phenomenon of territorialization” [

59] (p. 585), normally favouring hegemonic socioeconomic and political interests. Thus, the State can be considered a meta-organization designed to regulate, monitor, contain, and normalize the strategies and interests of organizations and interest groups [

60].

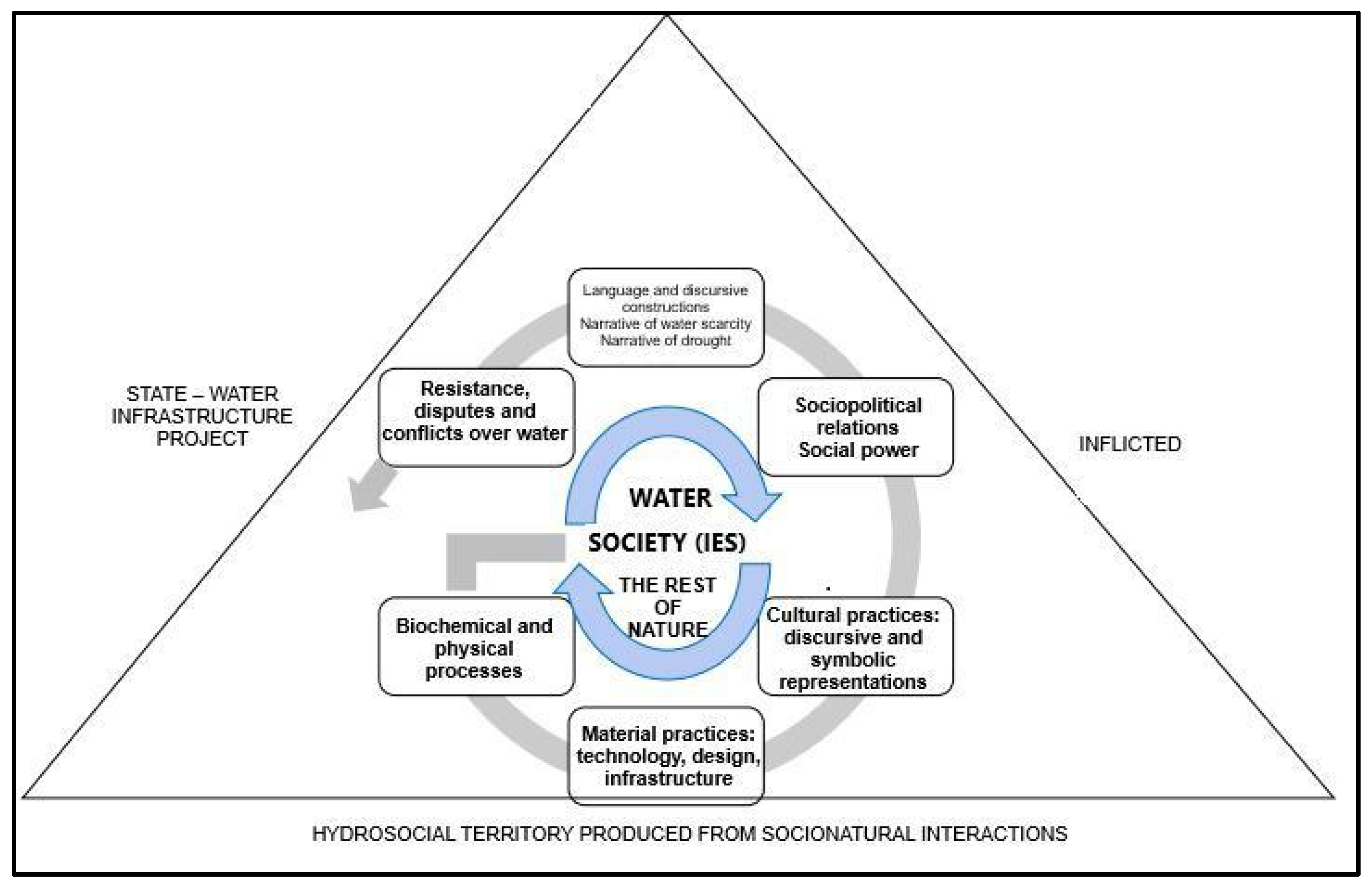

The PISF, therefore, produced direct effects on the biophysical properties of water and, crucially, on the hydrosocial territory produced from socio-natural interactions, as well as on the lives of people living in those territories. In other words, water projects such as the transposition of the São Francisco River materialize new hydrosocial territories (see

Figure 4), defining new rules on space, social relations, infrastructure, and water flows, which directly affect the socio-territorial course of territorialization and result in the affirmation of certain types of territorialities or the condemnation of others, in addition to the intensification of conflicts over water. In this context, paths were opened for water injustice and spaces of contestation to guarantee people’s access to water, especially part of those rural communities that were re-territorialized in rural villages located near the water project. Although the affected community is located in its surroundings, it does not guarantee access to and use of the transposed waters.

The research findings show that the PISF was proposed by a popular government and with transformative rhetoric, but in practice its implementation was subordinated to political conciliation and the power of the large landowners and clientelism of the Northeast. During its design and implementation, it was rarely possible to involve people in the decision-making process. The current situation is one of profound public marginalization, leaving communities unable to deal with the recurring and lived problems of water. In the rare moments when stakeholders can participate in the debate, this is much more at the level of information than at the level of decision-making. As a result, it is not easy to change the existing paternalistic tradition when the population is so accustomed to it. While it is crucial to build societal involvement in the region, it is really difficult to persuade societies suffering from poverty and hunger to consider the long term. The reality of illiteracy and populism is the result, but it also serves to perpetuate poverty and marginalization. Furthermore, financial and political discontinuity during the implementation of official programs fuelled public disappointment and a consequent lack of support.

It is important to emphasize that stakeholder participation does not only mean public consultation or legitimizing previous decisions but should translate into real gains when people are involved from the beginning of the planning process, participating in decisions on priorities for development programs, budget allocation, and project evaluation. Measures should be supported by community-integrated efforts, starting with a clear and precise determination of real and achievable objectives and evolving in a participatory manner throughout global water plans and initiatives. Political will is essential to bring about real change in water management practices since it would never be implemented without broad political support. In the next session, we bring together empirical results and theoretical points to make sense of the disputes and collaboration around land and water in the São Francisco River basin.

5. Analysis and Discussion

In this context, we consider that the PISF hydrosocial cycle was constituted by current relationships entangled in past legacies that ended up defining the paths of new water flows based on reflections of past sociopolitical relationships. Thus, we believe that the research presents important theoretical contributions to the literature on the Hydrosocial Cycle, considering that it is permeated by deep-rooted disputes and conflicts fought by actors who have their territories transformed and, in many cases, their access to water denied, to ensure that other voices matter and that there are other ways of relating to nature and resisting attempts to turn water into a commodity. Political ecology from Latin America has already shown that the processes are quite conflictive and that, despite the asymmetry of power, there is much struggle and resistance. Certainly, it is an important contribution to the literature on the hydrosocial cycle, since little attention is given to the different forms of resistance.

Based on these reflections, we present a new approach to the hydrosocial cycle that is the result of a hybrid socio-natural process, inspired by Swyngedouw [

26] and the perspective of Linton and Budds [

28]. This new approach to the hydrosocial cycle goes beyond the approaches presented so far and sheds light on other important factors, such as the agent responsible for the large water projects, in this case the State, the territorial transformations produced, hydrosocial territories, and the population affected, since, in most cases, the implementation of water projects is accompanied by profound transformations in the ways of life of the people who live there.

Figure 5 illustrates the hydrosocial cycle of the proposed PISF, which is constituted by the intertwining of the biochemical and physical processes of water with material, cultural, and discursive practices, which are permeated by sociopolitical relations, disputes, and conflicts.

Figure 5 illustrates the metabolic cycle of water and its various correlations. It is important to note that the entire debate has water at its core, which is why it is understood here as a socio-natural relationship that mediates between society (with its different social groups with immense inequalities) and the rest of nature. We emphasize that the figure does not intend to exhaust all the possibilities of analytical relationships. This metabolic cycle is disturbed by the implementation of the PISF water project, understood here not only as a physical artifact but as a social relationship in a specific and concrete historical, spatial, geographic, and historical context, capable of transforming the territory and relationships and, in its concrete materiality, defining processes of exclusion and marginalization of the people directly affected.

Considering the affected people as one of the important aspects in the hydrosocial cycle approach becomes fundamental since they are the ones who suffer the most from changes in their ways of life and territories, and, generally, they are the ones who may have their ways of life interrupted and have access to water denied. Having an analysis in light of the affected actors emphasizes the diversity that simultaneously exists in the territories, and this is certainly a clear contribution of this article since most of the literature focuses particularly on the hegemonic structures and discourses that lead to (and result from) territorial reconfiguration (as indicated by Swyngedouw; Boelens [

22]).

All transformations, in turn, produce hydrosocial territories, which integrate space and technical-physical, social, and natural relations. These are new territorial and social configurations resulting from the interaction of the hydraulic project itself, the institutions involved, the affected actors, and the new water flows. The concept of hydrosocial territories is especially suitable for the multidimensional analysis proposed here, as it integrates territorial and socio-natural transformations. Therefore, the physical landscape is represented by the hydrosocial territory constituted by the PISF, which directs water flows to large cities and ends up leaving the communities surrounding the project without access to water, thus perpetuating the historical conflicts over water in the Northeast region of Brazil.

6. Conclusions

The research shows that, although the PISF water project was implemented in the Northeast of Brazil, water allocation and access were not guaranteed for rural communities. Thus, water scarcity is not explained by water flow, but rather water allocation and access are entangled in broader sociopolitical relations, even more so in contexts historically marked by the concentration of water sources and land, such as the region. Thus, the prevailing approach to water scarcity and water supply adopted by the PISF has not changed the underlying social structure, established since the beginning of the 17th century, which is why rural families continue to have dry territories, although the hydrosocial cycle floods their territories.

The most sensitive economic sector has traditionally been subsistence agriculture, and those most affected by droughts are impoverished social groups, who suffer even during small fluctuations in rainfall. Man-made water scarcity acts as an “aggravating agent” that further depletes already marginal rural productivity [

61]. The main economic adversity of developing semiarid regions, such as the São Francisco Valley, is not climate variability, drought, soil erosion, or flooding, but the vulnerability of the population to the effects of these events. Semiaridity undoubtedly poses serious difficulties for human survival, but it is not the fundamental reason for underdevelopment and poverty, as local political leaders usually claim. On the contrary, the main social and structural problem is the situation of serious concentration of wealth, particularly in rural areas.

Consequently, the vast majority of the rural population has no possibility of economic accumulation and simply struggles to survive. The difficulties of a given community to survive during periods of famine and hunger are more related to poor social organization or weak political representation than to physical reasons alone. Despite inclusive rhetoric, government initiatives implemented as part of the PISF did not aim to change the pattern of land distribution and rarely, if ever, reduced vulnerability to drought by providing water security to the majority of the population.

Applying a hydrosocial cycle perspective opens new insights into the interfaces of how large water projects are not neutral but are intertwined with broader sociopolitical issues, so that water access rights and water-related infrastructure need to be constantly contested and renegotiated as water projects fail to guarantee full access.

This article contributes to the knowledge on how large water infrastructure projects result in exclusionary territorial dynamics that result in socio-natural effects for the most vulnerable populations, providing clues for a critical analysis that adheres to SDG-6. In this sense, going beyond our research on the hydrosocial cycle, it is necessary to have a deeper understanding of the specificities and forms of political organization of rural communities in the face of difficulties in accessing water, as well as the institutional forms of governance of the project, considering that it is a project that is close to completion and the federal government is defining its management form. This will allow, on the one hand, to identify how communities develop strategies of action and struggle and, on the other, how institutional actors of governance of the PISF have been shaping and defining the forms of management of the project in order to guarantee a more sustainable management of the water project.