Influencing Factors of Peasant Households’ Willingness to Relocate to Concentrated Residences in Mountainous Areas: Evidence from Rural Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

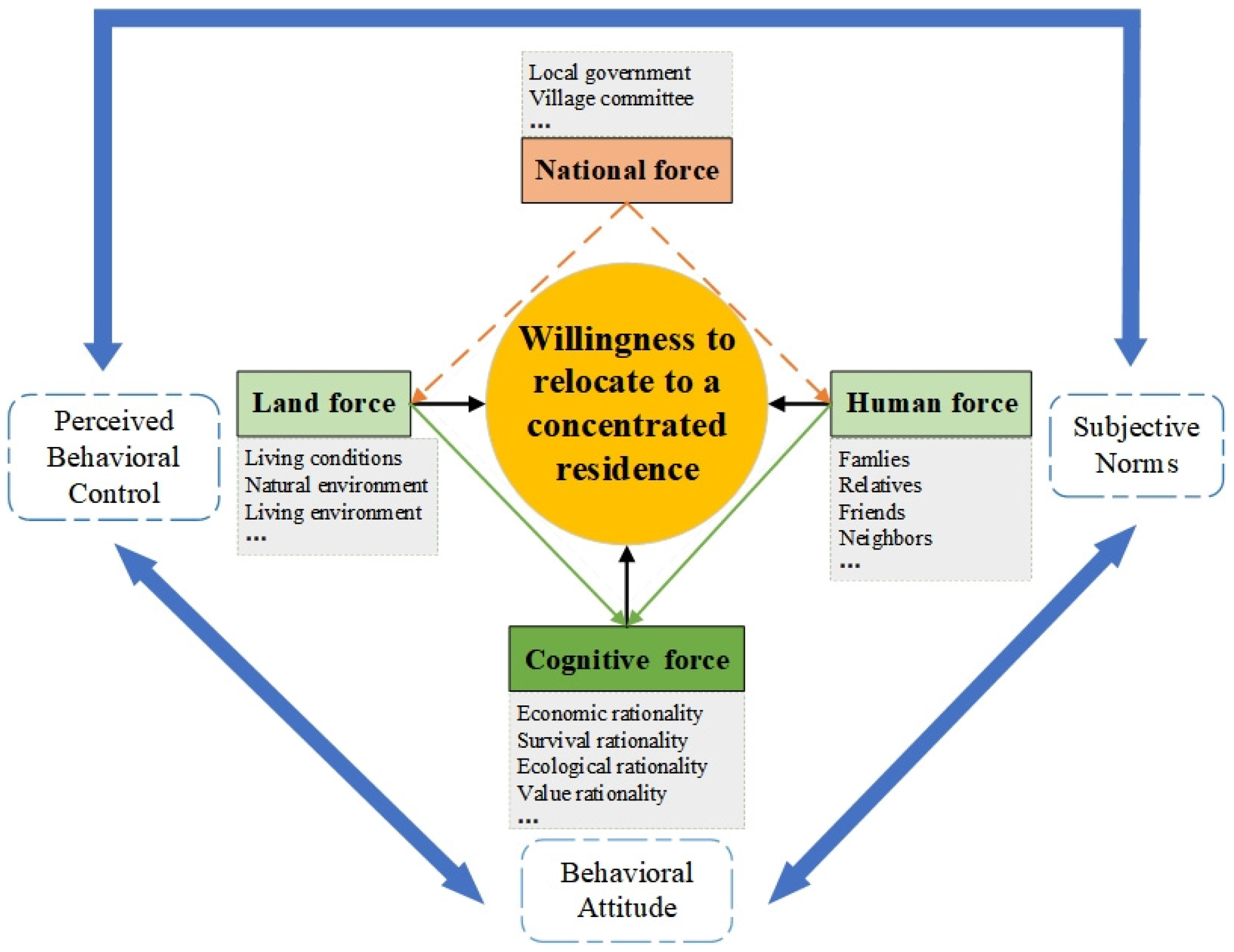

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. The Social Cognitive Theory

2.3. The Policy Process Theory

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Selection of the Model Variables

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Respondents

3.2.2. Selection of Variables

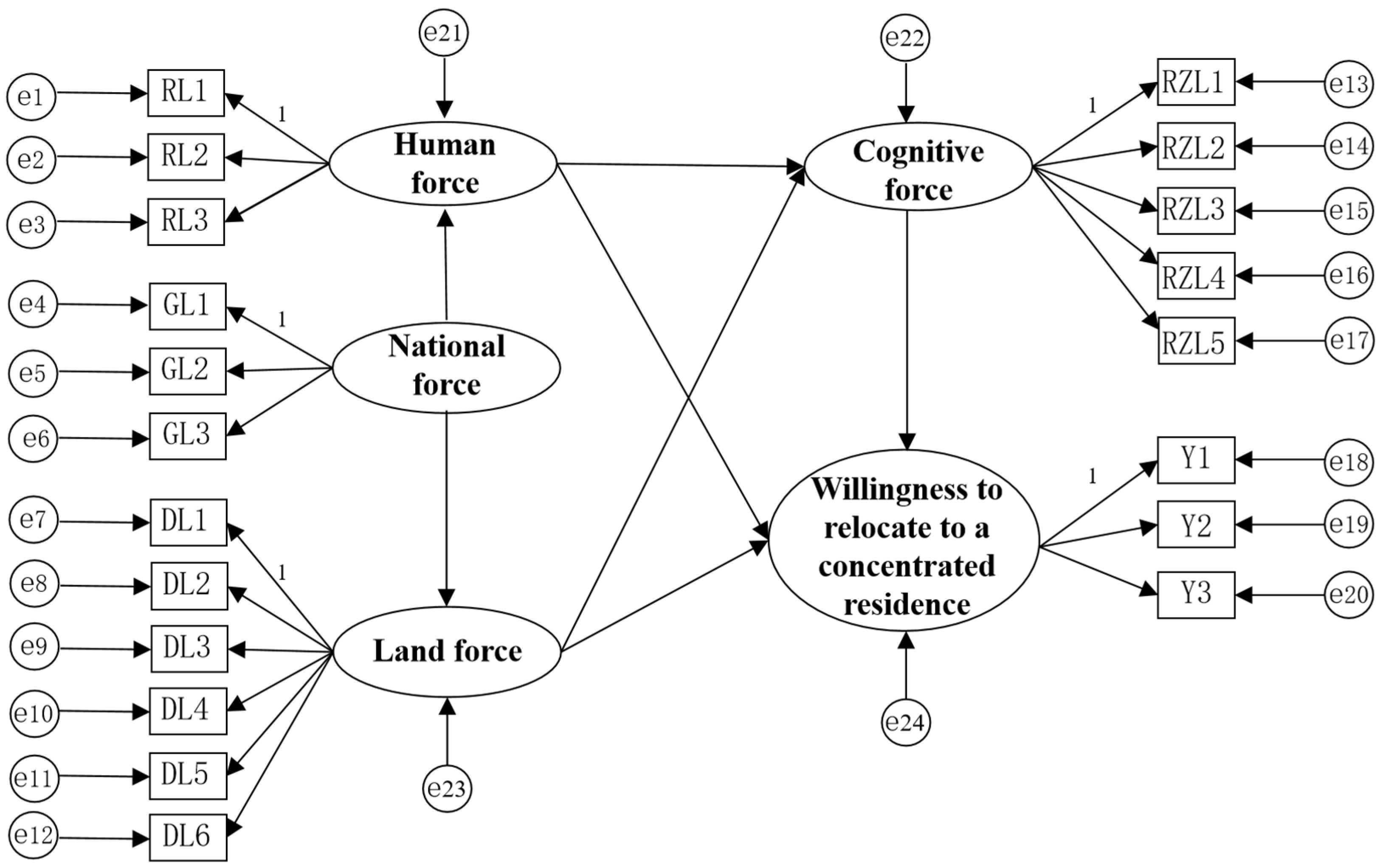

3.3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability

4.2. Fitting and Adaption of Models

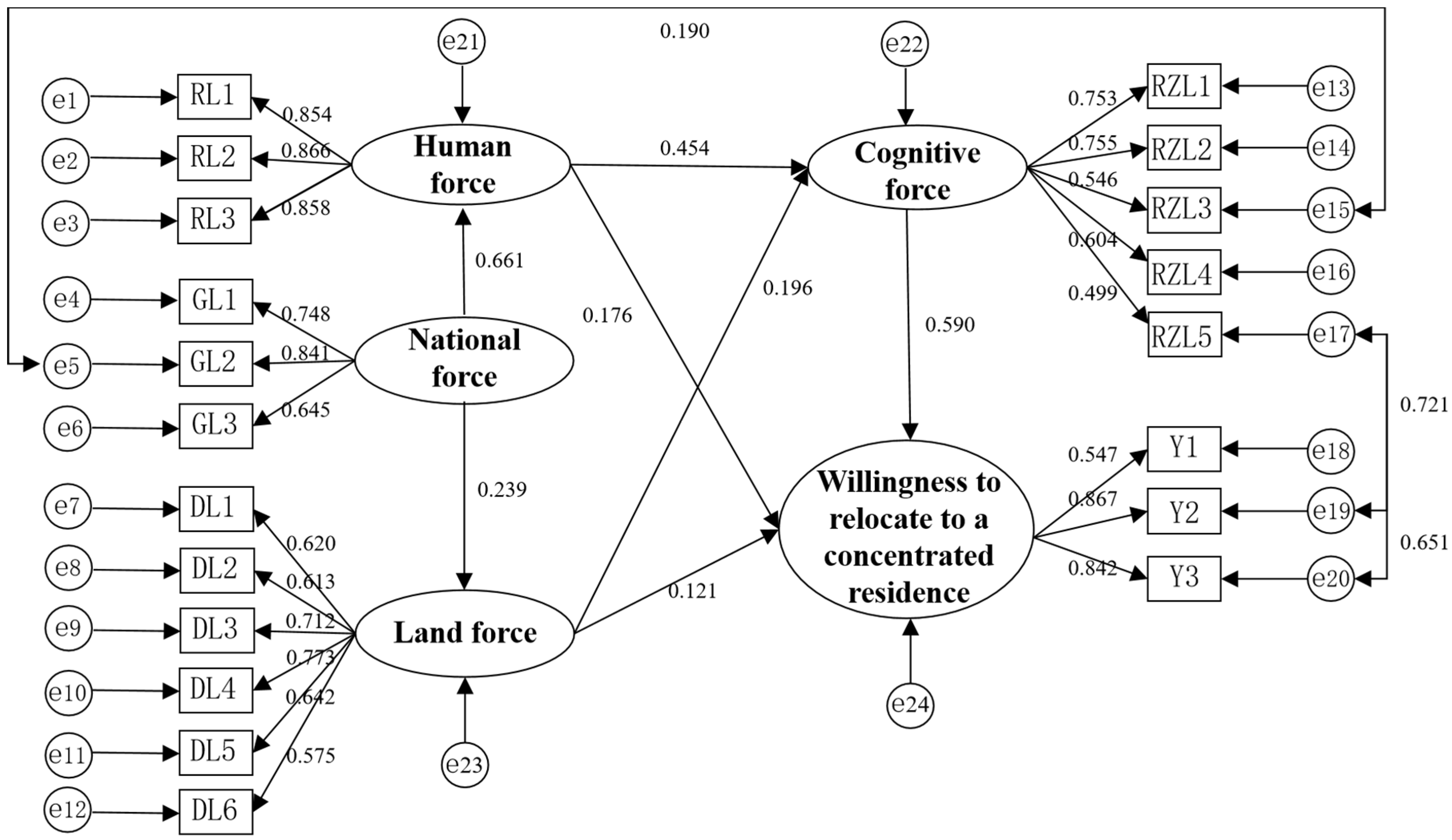

4.3. Modified Model Results

4.3.1. Modified Measurement Model Results

4.3.2. Modified Structural Model Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, L.; Wang, L.; Su, K.; Bi, G.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q. Spatiotemporal characteristics of rural restructuring evolution and driving forces in mountainous and hilly areas. Land 2022, 11, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, F.; Huang, L.; Xue, J.; Xu, Y. Farmers’ risk perception of concentrated rural settlement development after the 5.12 Sichuan Earthquake. Habitat. Int. 2018, 71, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X. Chongqing Village-Type Farmers Concentration Building Mechanism on Study. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen, N.R.; Trivic, Z. Dynamic place attachment in the context of displacement processes: The socio-ecological model. Cities 2024, 148, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Feng, D. Research on spatial restructuring of farmers’ homestead based on the “Point-Line-Surface” characteristics of mountain villages. Land 2023, 12, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Tu, S. Land use transitions: Progress, challenges and prospects. Land 2021, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Guo, Z.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A. An empirical approach for enhancing farmers’ concentrated residence strategies: A case study in Jiangsu Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenburg, E.M.; van de Werfhorst, H.G.; Musterd, S.; Tieskens, K. Consequences of forced residential relocation: Early impacts of urban renewal strategies on forced relocatees’ housing opportunities and socioeconomic outcomes. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruming, K.; Melo Zurita, M.d.L. Care and dispossession: Contradictory practices and outcomes of care in forced public housing relocations. Cities 2020, 98, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, O. Sustainable developmentality: Interrogating the sustainability gaze and the cultivation of mountain subjectivities in the central Indian Himalayas. Geoforum 2021, 127, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Analysis and Measures on Farmers’ Willingness of Collective Living: Taking Nanhu District of Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province for Example. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheteni, P.; Khamfula, Y.; Mah, G. Gender and poverty in South African rural areas. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1586080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukvic, A.; Barnett, S. Drivers of flood-induced relocation among coastal urban residents: Insight from the US east coast. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, R.; Pakravan-Charvadeh, M.R.; Rahimian, M. Multi-level factors influencing climate migration willingness among small-scale farmers. Front. Envrion. Sci. 2024, 12, 1434708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H. Impact of relocation in response to climate change on farmers’ livelihood capital in minority areas: A case study of Yunnan Province. Int. J. Clim. Chang Str. 2023, 15, 790–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüner, B. Two close-to-nature lifestyles, one benefit for the cultural landscape: Comparing lifestyle movers and lifestyle farmers in the remote European Eastern Alps. Mt. Res. Dev. 2023, 43, R1–R11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O.; Budzinski, W.; Kosiorowski, G. The pure effect of social preferences on regional location choices: The evolving dynamics of convergence to a steady state population distribution. J. Reg. Sci. 2019, 59, 883–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hu, S.; Que, T.; Li, H.; Xing, H.; Li, H. Influences of social environment and psychological cognition on individuals’ behavioral intentions to reduce disaster risk in geological hazard-prone areas: An application of social cognitive theory. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 2023, 86, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Impact of different models of relocating coal mining villages on the livelihood resilience of rural households—A case study of Huaibei City, Anhui Province. Land 2023, 12, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Peralta, L.P.; de Roda, A.B.L.; Ángeles Molina-Martínez, M.; Schettini Del Moral, R. Family and community support among older Chilean adults: The importance of heterogeneous social support sources for quality of life. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2018, 61, 584–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Miller, F. Slow, small and shared voluntary relocations: Learning from the experience of migrants living on the urban fringes of Khulna, Bangladesh. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2019, 60, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plys, E. Reasons for relocating to assisted living: The push, the pull, and decision control. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, S638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mızrak, S.; Turan, M. Effect of individual characteristics, risk perception, self-efficacy and social support on willingness to relocate due to floods and landslides. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 1615–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebecchi, A.; Gola, M.; Riva, A.; Capolongo, S. Can housing conditions and features affect well-being? A review through indoor environmental quality aspects and mental health implications. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 160–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. Displaced villagers’ adaptation in concentrated resettlement community: A case study of Nanjing, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. What does the future hold for relocated communities post-disaster? Factors affecting livelihood resilience. Int. J. Disast. Risk Re. 2019, 34, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah Hulio, A.; Varghese, V.; Chikaraishi, M. Analyzing the preferences of flood victims on post flood public houses (PFPH): Application of a hybrid choice model to the floodplains of southern Pakistan. Clim. Risk Manag. 2023, 42, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wu, Q.; Li, X. Impact of labor transfer differences on terraced fields abandonment: Evidence from micro-survey of farmers in the mountainous areas of Hunan, Fujian and Jiangxi. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 1702–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.S.; Price, M.; Gros, K.S.; Ruggiero, K.J. Community support as a moderator of postdisaster mental health symptoms in urban and nonurban communities. Disaster Med. Public 2013, 7, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagi, S.; Javernick-Will, A. Institutional constraints influencing relocation decision making and implementation. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 2019, 33, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Anh, T.; Nong, D.; Leu, S.; To-The, N. Changes in the environment from perspectives of small-scale farmers in remote Vietnam. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S.; Pizam, A.; Wang, Y.; Severt, D.; Oetjen, R. Factors affecting seniors’ decision to relocate to senior living communities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, M.; Cao, S.; Yu, H. Driving forces for the spatial reconstruction of rural settlements in mountainous areas based on Structural Equation Models: A case study in Western China. Land 2021, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y.; Loh, W.W. A structural after measurement approach to structural equation modeling. Psychol. Methods 2022, 29, 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortreux, C.; Safra de Campos, R.; Adger, W.N.; Ghosh, T.; Das, S.; Adams, H.; Hazra, S. Political economy of planned relocation: A model of action and inaction in government responses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 50, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, P.; Mahdi, S.; Mundir, I.; McCaughey, J.; Amalia, C.S.; Jannah, R.; Horton, B. Social capital and community integration in post-disaster relocation settlements after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami in Indonesia. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lü, B.; Chen, R. Evaluating the life satisfaction of peasants in concentrated residential areas of Nanjing, China: A fuzzy approach. Habitat. Int. 2016, 53, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, X. Influence of housing resettlement on the subjective well-being of disaster-forced migrants: An empirical study in Yancheng City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karani, I.; Papada, L.; Kaliampakos, D. Energy poverty signs in mountainous Greek areas: The case of Agrafa. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2022, 41, 1408–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Salotti, G.; Mascadri, G. Conditions for operating in marginal mountain areas: The local farmer’s perspective. Societies 2023, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, S.; Wästfelt, A. The poverty of farmers in a main grain-producing area in Northeast China. Land 2022, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, Y.; Du, G.; Huang, S. Understanding the contradiction between rural poverty and rich cultivated land resources: A case study of Heilongjiang Province in Northeast China. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yin, K.; Pan, L. Study on the change of livelihood capital of poverty alleviation farmers in hilly and mountainous areas of southwest china and its regulation on people’s anxiety. Int. J. Neuropsychoph. 2022, 25, A78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, R.; Gifford, R. Causality in the theory of planned behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 45, 920–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhou, W.; He, J.; Qing, C.; Xu, D. Effects of land transfer on farmer households’ straw resource utilization in rural Western China. Land 2023, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keer, M.; van den Putte, B.; Neijens, P. The role of affect and cognition in health decision making. Brit. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; He, J.; Xu, D. How do peer effects affect the transformation of farmers’ willingness and behavior to adopt biogas? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Pro-environmental behavior on electric vehicle use intention: Integrating value-belief-norm theory and theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hua, Y. Integrating social presence with social learning to promote purchase intention: Based on social cognitive theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 810181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesam, M.; Roshan, G.; Grab, S.W.; Shabahrami, A.R. Comparative assessment of farmers’ perceptions on drought impacts: The case of a coastal lowland versus adjoining mountain foreland region of northern Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 143, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novira, N.; Maxriz, J.; Astuti, A. The socio-economic impact of relocation policy to the communities affected by the mount sinabung eruption: A preliminary study. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 683, 012094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montpetit, M.A.; Nelson, N.A.; Tiberio, S.S. Daily interactions and affect in older adulthood: Family, friends, and perceived support. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, L.E.; Thies, C.G. Leader influence in role selection choices: Fulfilling role theory’s potential for foreign policy analysis. Int. Stud. Rev. 2021, 23, 1424–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle Alverio, G.; Hoagland, S.H.; Coughlan de Perez, E.; Mach, K.J. The role of international organizations in equitable and just planned relocation. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 11, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Xu, D.; Xie, F.; Liu, E.; Liu, S. The influence factors analysis of households’ poverty vulnerability in southwest ethnic areas of China based on the hierarchical linear model: A case study of Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 66, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Petersen, M. Poverty alleviation as an economic problem. Camb. J. Econ. 2019, 43, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lan, Y.; Wang, X. Impact of livelihood capital endowment on poverty alleviation of households under rural land consolidation. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.P.R. A nonparametric approach to understanding poverty in the Philippines: Evidence from the family income and expenditure survey. Poverty Public Policy 2022, 14, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Zhou, W.; He, J.; Xu, D. Land Certification, Adjustment Experience, and Green Production Technology Acceptance of Farmers: Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, S. Effects of natural disasters on livelihood resilience of rural residents in Sichuan. Habitat. Int. 2018, 76, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, M. Analysis of the Spatial Conflicts of the National Land and Its Influencing Factors. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Habibah, U.; Hassan, I.; Iqbal, M.S.; Naintara, N. Household behavior in practicing mental budgeting based on the theory of planned behavior. Financ. Innov. 2018, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Poverty alleviation through land assetization and its implications for rural revitalization in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klärner, A.; Knabe, A. Social networks and coping with poverty in rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 447–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, W.; Peng, L. The coupling mechanism between the suitable space and rural settlements considering the effect of mountain hazards in the upper Minjiang River basin. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 2774–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, S.H. The impact of government policies and regulations on the subjective well-being of farmers in two rural mountain areas of Italy. Agr. Hum. Values 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Gao, W.; Miao, S. A new scale to assist in evaluating architectural proposals on the natural dimension based on psychometrics. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 100, 105037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saris, W.E.; Satorra, A.; van der Veld, W.M. Testing Structural Equation Models or detection of misspecifications? Struct. Equ. Model. 2009, 16, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.J.; Gonzalez, O.; Miočević, M.; MacKinnon, D.P. A note on testing mediated effects in Structural Equation Models: Reconciling past and current research on the performance of the test of joint Significance. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 76, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.; Lascelles, K. Involving and supporting families, friends, and carers during a mental health crisis. Lancet Psychiat. 2024, 11, 586–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junquera, V.; Rubenstein, D.I.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Knaus, F. Structural change in agriculture and farmers’ social contacts: Insights from a Swiss mountain region. Agr. Syst. 2022, 200, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang-Duc, C.; Nguyen-Thu, H.; Nguyen-Anh, T.; Tran-Duc, H.; Nguyen-Thi-Thuy, L.; Do-Hoang, P.; To-The, N.; Vu-Tien, V.; Nguyen-Thi-Lan, H. Governmental support and multidimensional poverty alleviation: Efficiency assessment in rural areas of Vietnam. J. Econ. Inequal. 2024, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardo, W.; van de Ven, G.W.J.; Kanellopoulos, A.; Giller, K.E. Addressing social, psychological and economic barriers helps people out of extreme poverty. Nature, 2022; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lyu, L.; Xu, J. Factors Influencing Rural Households’ Decision-Making Behavior on Residential Relocation: Willingness and Destination. Land 2021, 10, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wen, Y.; Wang, R.; Han, W. Factors influencing rural households’ willingness of centralized residence: Comparing pure and nonpure farming areas in China. Habitat. Int. 2018, 73, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugmas, M.; Ferligoj, A.; Kogovšek, T.; Batagelj, Z. The social support networks of elderly people in Slovenia during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Definition | Mean | SD c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Respondents’ gender (female = 1, male = 0) | 0.316 | 0.466 |

| Ethnicity | Respondents’ ethnicity (Han = 1, Yi = 2, Tibetan = 3, other = 4) | 1.746 | 0.436 |

| Age | Respondents’ age (year) | 47.444 | 15.171 |

| Education | Respondents’ education level (year) | 3.724 | 3.999 |

| Health | Respondents’ health level (1 = very healthy–5 = very unhealthy) | 2.273 | 1182 |

| Occupation | Respondents’ occupation (1 = full-time farming, 2 = part-time farming, 3 = wage labor, 4 = other occupations) | 1.509 | 1.089 |

| Family scale | Total family population in 2019 (person) | 4.624 | 1.747 |

| Elderly people | Household count of individuals aged 64 and older (number of the persons) | 0.615 | 0.787 |

| Children | Household count of children aged under 6 (number of persons) | 0.515 | 0.804 |

| Family labor | Household labor force count within the age range of 16–64 (number of persons) | 1.760 | 1.173 |

| Latent Variables | Observation Variables | Definition | Mean | SD c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land force | Housing quality | DL1: Do you feel that the quality of the housing you live in is not good? a | 3.479 | 1.089 |

| Geological hazards | DL2: Do earthquakes, landslides, mudslides, and other disasters occur frequently where you live? a | 2.800 | 1.211 | |

| Infrastructure conditions | DL3: Do you think the infrastructure in the village is in poor condition? a | 3.217 | 1.07 | |

| Living environment | DL4: Do you think the living environment is poor where you live? a | 3.128 | 1.098 | |

| Land quality | DL5: Do you think the land is infertile and the quality of the arable land is poor? a | 2.926 | 1.043 | |

| Agricultural income | DL6: Do you feel that income from farming is low where you live? a | 3.472 | 1.03 | |

| Human force | Support from relatives and friends | RL1: Do you think your relatives and friends will support you in relocation? a | 3.462 | 0.996 |

| Neighborhood support | RL2: Do you think your neighbors will support you in relocation? a | 3.390 | 1.003 | |

| Family support | RL3: Do you think your family will support you in relocation? a | 3.449 | 1.079 | |

| Cognitive force | Economic rationality 1 | RZL1: Do you think that concentrated residence will improve the standard of living of families? a | 3.699 | 0.807 |

| Economic rationality 2 | RZL2: Do you think that concentrated residence will improve the living conditions of families? a | 3.891 | 0.825 | |

| Ecological rationality | RZL3: Do you think that concentrated residence will be conducive to the efficient use of land? a | 3.560 | 0.957 | |

| Survival rationality | RZL4: Do you feel that concentrated residence will be good for future generations? a | 3.837 | 0.916 | |

| Value rationality | RZL5: Do you think it is a good thing for the government to organize concentrated residence for poverty alleviation? a | 3.474 | 0.979 | |

| National force | Local government support | GL1: Do you feel that your local government supports you in relocation? a | 3.617 | 0.847 |

| Village committee support | GL2: Do you feel that your village committee will support and guide you in your relocation? a | 3.615 | 0.881 | |

| Policy advocacy | GL3: Have you been informed by village cadres about the policy of relocation for poverty alleviation? a | 3.398 | 1.098 | |

| Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | Form of living | Y1: Would you prefer to move to a concentrated residence than to live scattered in the hills? b | 3.457 | 1.039 |

| Choice of living 1 | Y2: Would you like to move to a concentrated residence in the town? b | 2.985 | 1.156 | |

| Choice of living 2 | Y3: Would you like to move to a concentrated residence in the village? b | 2.985 | 1.051 |

| Latent Variables | Observation Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | KMO | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Chi-Square | Degree of Freedom | p Value | ||||

| Land force | DL1, DL2, DL3, DL4, DL5, DL6 | 0.818 | 0.866 | 706.892 | 15 | 0.000 |

| Human force | RL1, RL2, RL3 | 0.893 | 0.749 | 712.814 | 3 | 0.000 |

| Cognitive force | RZL1, RZL2, RZL3, RZL4, RZL5 | 0.743 | 0.787 | 472.674 | 10 | 0.000 |

| National force | GL1, GL2, GL3 | 0.769 | 0.672 | 366.175 | 3 | 0.000 |

| Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | Y1, Y2, Y3 | 0.808 | 0.748 | 698.660 | 3 | 0.000 |

| Overall | 0.871 | 0.848 | 2370.574 | 136 | 0.000 | |

| Factor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Land force | DL1 | 0.685 | 0.118 | 0.086 | −0.020 |

| DL2 | 0.679 | 0.071 | 0.026 | 0.013 | |

| DL3 | 0.774 | −0.047 | 0.055 | 0.029 | |

| DL4 | 0.777 | 0.157 | 0.108 | 0.122 | |

| DL5 | 0.697 | 0.124 | 0.022 | 0.113 | |

| DL6 | 0.693 | −0.184 | 0.028 | 0.016 | |

| Human force | RL1 | 0.087 | 0.78 | 0.193 | 0.339 |

| RL2 | 0.042 | 0.858 | 0.131 | 0.266 | |

| RL3 | 0.051 | 0.837 | 0.231 | 0.242 | |

| Cognitive force | RZL1 | 0.06 | 0.237 | 0.746 | 0.151 |

| RZL2 | 0.132 | 0.103 | 0.832 | −0.048 | |

| RZL3 | −0.065 | 0.089 | 0.669 | 0.147 | |

| RZL4 | 0.101 | 0.063 | 0.706 | 0.128 | |

| RZL5 | 0.311 | 0.348 | 0.429 | −0.302 | |

| National force | GL1 | 0.127 | 0.161 | 0.093 | 0.818 |

| GL2 | 0.079 | 0.284 | 0.119 | 0.806 | |

| GL3 | 0.029 | 0.364 | 0.137 | 0.644 | |

| Cumulative variance contribution rate | 68.136% | ||||

| Evaluation Indices | CMIN/DF | GFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | PGFI | PNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Model | 3.356 | 0.874 | 0.893 | 0.874 | 0.892 | 0.854 | 0.076 | 0.765 | 0.733 |

| Modified model | 2.447 | 0.910 | 0.935 | 0.923 | 0.935 | 0.895 | 0.060 | 0.787 | 0.063 |

| Fit standard | ≤3 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | ≤0.08 | >0.5 | >0.5 |

| Items | NSE | 1 SE | CR | 2 SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL1 | ← | Land force | 1 | 0.620 *** | ||

| DL2 | ← | Land force | 1.1 | 0.111 | 9.909 | 0.613 *** |

| DL3 | ← | Land force | 1.128 | 0.102 | 11.031 | 0.712 *** |

| DL4 | ← | Land force | 1.258 | 0.108 | 11.603 | 0.773 *** |

| DL5 | ← | Land force | 0.993 | 0.097 | 10.262 | 0.642 *** |

| DL6 | ← | Land force | 0.878 | 0.093 | 9.433 | 0.575 *** |

| RL1 | ← | Human force | 1 | 0.854 *** | ||

| RL2 | ← | Human force | 1.022 | 0.048 | 21.183 | 0.866 *** |

| RL3 | ← | Human force | 1.089 | 0.052 | 20.935 | 0.858 *** |

| RZL1 | ← | Cognitive force | 1 | 0.753 *** | ||

| RZL2 | ← | Cognitive force | 1.024 | 0.077 | 13.284 | 0.755 *** |

| RZL3 | ← | Cognitive force | 0.863 | 0.087 | 9.967 | 0.546 *** |

| RZL4 | ← | Cognitive force | 0.91 | 0.083 | 10.937 | 0.604 *** |

| RZL5 | ← | Cognitive force | 0.796 | 0.086 | 9.211 | 0.499 *** |

| GL1 | ← | National force | 1 | 0.748 *** | ||

| GL2 | ← | National force | 1.170 | 0.083 | 14.167 | 0.841 *** |

| GL3 | ← | National force | 1.118 | 0.094 | 11.877 | 0.645 *** |

| Y1 | ← | Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | 1 | 0.547 *** | ||

| Y2 | ← | Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | 3.621 | 0.321 | 11.278 | 0.867 *** |

| Y3 | ← | Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | 3.197 | 0.285 | 11.223 | 0.842 *** |

| Items | NSE | 1 SE | CR | 2 SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | ← | Land force | 0.049 | 0.017 | 2.819 | 0.121 ** |

| Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | ← | Human force | 0.056 | 0.015 | 3.693 | 0.176 *** |

| Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | ← | Cognitive force | 0.263 | 0.035 | 7.565 | 0.590 *** |

| Cognitive force | ← | Human force | 0.324 | 0.042 | 7.758 | 0.454 *** |

| Cognitive force | ← | Land force | 0.176 | 0.052 | 3.394 | 0.196 *** |

| Human force | ← | National force | 0.888 | 0.081 | 10.967 | 0.661 *** |

| Land force | ← | National force | 0.254 | 0.066 | 3.872 | 0.239 *** |

| Variables | Land Force | Human Force | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | |

| Land force | ||||||

| Human force | ||||||

| Cognitive force | 0.176 | 0.176 | 0.324 | 0.324 | ||

| Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.095 | 0.056 | 0.085 | 0.141 |

| Variables | Cognitive Force | National Force | ||||

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | |

| Land force | 0.254 | 0.254 | ||||

| Human force | 0.888 | 0.888 | ||||

| Cognitive force | 0.333 | 0.333 | ||||

| Willingness to relocate to a concentrated residence | 0.263 | 0.263 | 0.150 | 0.150 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, J.; Cao, Q.; Chen, R.; Liu, S.; Lian, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhou, N. Influencing Factors of Peasant Households’ Willingness to Relocate to Concentrated Residences in Mountainous Areas: Evidence from Rural Southwest China. Land 2024, 13, 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101705

Zhong J, Cao Q, Chen R, Liu S, Lian Z, Yu H, Zhou N. Influencing Factors of Peasant Households’ Willingness to Relocate to Concentrated Residences in Mountainous Areas: Evidence from Rural Southwest China. Land. 2024; 13(10):1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101705

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Jia, Qian Cao, Ruiyin Chen, Shaoquan Liu, Zhaoyang Lian, Hui Yu, and Ningchuan Zhou. 2024. "Influencing Factors of Peasant Households’ Willingness to Relocate to Concentrated Residences in Mountainous Areas: Evidence from Rural Southwest China" Land 13, no. 10: 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101705

APA StyleZhong, J., Cao, Q., Chen, R., Liu, S., Lian, Z., Yu, H., & Zhou, N. (2024). Influencing Factors of Peasant Households’ Willingness to Relocate to Concentrated Residences in Mountainous Areas: Evidence from Rural Southwest China. Land, 13(10), 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101705