From Health Risks to Environmental Actions: Research on the Pathway of Guiding Citizens to Participate in Pocket-Park Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

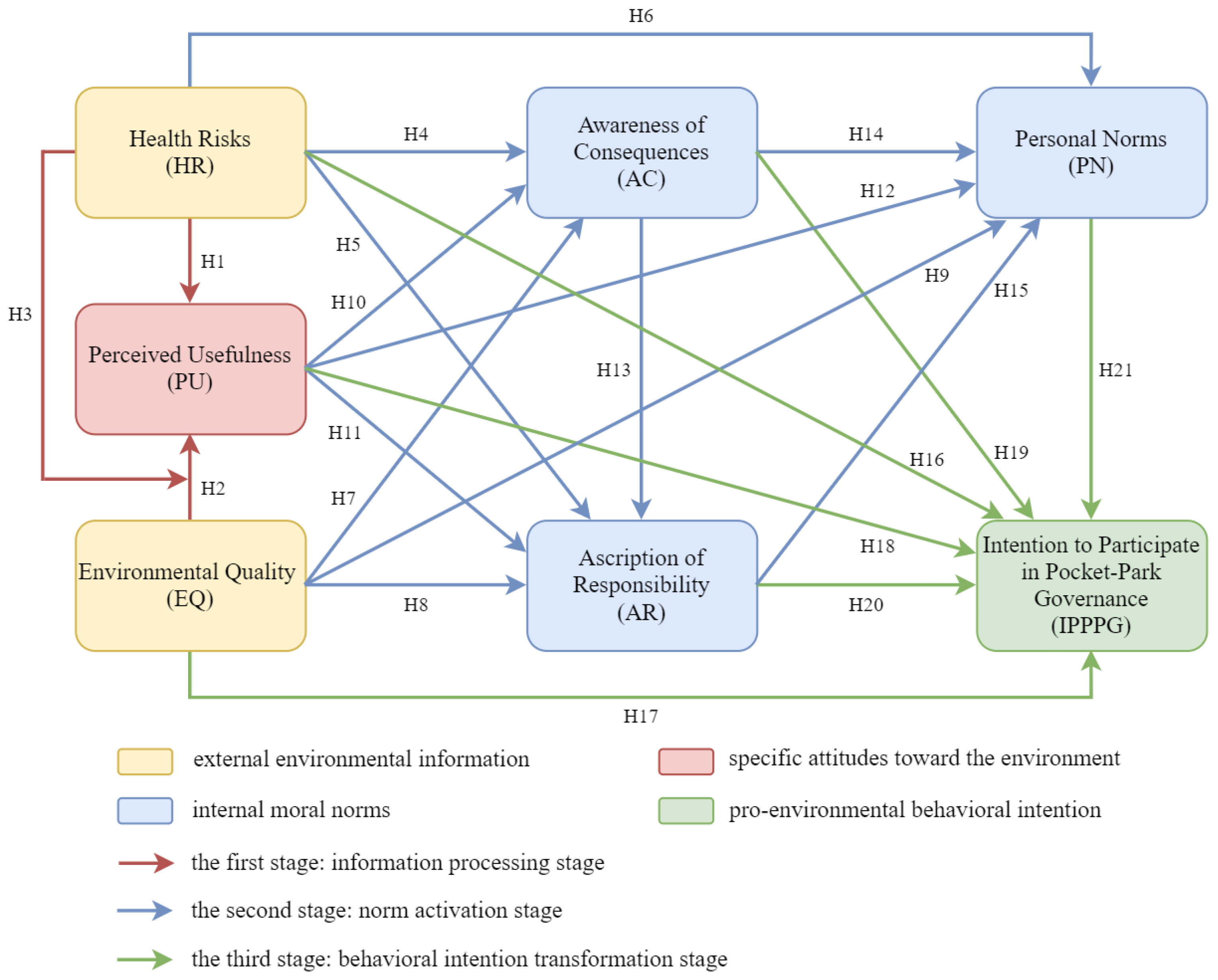

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Norm Activation Model

2.2. Social Information Processing Theory

2.3. The Information-Processing Stage: Influences of Health Risks and Environmental Quality on Perceived Usefulness

2.4. The Norm-Activation Stage: Relationships between External Environmental Information, Attitudes, and Moral Norms

2.4.1. Influences of Health Risks, Environmental Quality, and Perceived Usefulness on Components of the NAM

2.4.2. Relationships among Variables within the NAM

2.5. The Behavioral-Intention-Transformation Stage: Predictors of Intention to Participate in Pocket-Park Governance

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Respondents’ Profile

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health risks | HR1 | Infectious diseases are likely to negatively affect my daily routine/life. | [42,86] |

| HR2 | There is a high risk of contracting diseases. | ||

| HR3 | The consequence of getting infected by diseases is severe. | ||

| HR4 | I am worried I might contract diseases. | ||

| Environmental quality | EQ1 | I think this pocket park is very clean. | [46,62] |

| EQ2 | I think the eco-landscapes of this pocket park are protected pretty well. | ||

| EQ3 | The greening efforts of this pocket park are good. | ||

| EQ4 | I think the air quality of this pocket park is pretty good. | ||

| EQ5 | This pocket park provides sufficient environmental facilities (e.g., garbage bins). | ||

| Perceived usefulness | PU1 | Pocket parks provide usable green spaces during the pandemic. | [62,80] |

| PU2 | Pocket parks provide opportunities to do physical exercise. | ||

| PU3 | Pocket parks provide opportunities for recreation and relaxation. | ||

| PU4 | Using pocket parks helps with physical health and reduces disease risk. | ||

| PU5 | Pocket parks contribute to my quality of life during the pandemic. | ||

| Awareness of consequences | AC1 | Environmentally unfriendly behaviors will damage the environment of pocket parks. | [51,55] |

| AC2 | Environmentally unfriendly behaviors in pocket parks greatly increase the probability of disease transmission. | ||

| AC3 | Environmentally unfriendly behaviors in pocket parks may have negative impacts on physical health. | ||

| AC4 | Environmentally unfriendly behaviors in pocket parks are not conducive to resisting disease risks. | ||

| Ascription of responsibility | AR1 | I feel joint responsibility for environmental harm in pocket parks. | |

| AR2 | I feel jointly responsible for the environmental pollution problems in pocket parks. | ||

| AR3 | I believe that every citizen is partly responsible for the environmental damage of pocket parks. | ||

| AR4 | I feel that every citizen must take responsibility for the environmental pollution of pocket parks. | ||

| Personal norms | PN1 | I feel obliged to protect pocket parks. | [51] |

| PN2 | I would feel guilty about not taking pro-environmental behaviors in pocket parks. | ||

| PN3 | It would be against my moral principles not to take pro-environmental behaviors in pocket parks. | ||

| Intention to participate in pocket-park governance | IPPPG1 | I am willing to take environmental behaviors to maintain the cleanliness of pocket parks. | [26] |

| IPPPG2 | I would certainly think about participating in pocket-park environmental governance. | ||

| IPPPG3 | I think I would like to participate in pocket-park environmental governance. | ||

| IPPPG4 | I will participate in pocket-park environmental governance if I have an opportunity. |

References

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19) (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Ma, F. Assessing Immediate and Lasting Impacts of COVID-19-Induced Isolation on Green Space Usage Patterns. GeoHealth 2024, 8, e2024GH001062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.B.; Chang, C.-C.; Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Gardner, J.; Andersson, E. Nature experience from yards provide an important space for mental health during COVID-19. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2023, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, S.; Browning, M.H.; Rigolon, A.; Helbich, M.; James, P. Nature’s contributions in coping with a pandemic in the 21st century: A narrative review of evidence during COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, V.; Speak, A.; Ugolini, F.; Sanesi, G.; Carrus, G.; Salbitano, F. Attitudes towards urban green during the COVID-19 pandemic via Twitter. Cities 2022, 126, 103707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suligowski, R.; Ciupa, T. Five waves of the COVID-19 pandemic and green–blue spaces in urban and rural areas in Poland. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Tian, Q.; Cui, M.; He, M. A delicacy evaluation method for park walkability considering multidimensional quality heterogeneity. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 112, 103688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Yue, X.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Y. Community Gardens in China: Spatial distribution, patterns, perceived benefits and barriers. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WB. Urban Population (The Percentage of Total Population). 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org.cn/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?end=2022&start=1960&view=chart (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- NBS. China Statistical Yearbook. 2022. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2022/indexch.htm (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report. 2022. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2022 (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D. COVID-19, cities and inequality. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 160, 103059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilnezhad, M.R.; Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L. Attitudes and Behaviors toward the Use of Public and Private Green Space during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iran. Land 2021, 10, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerishnan, P.B.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Maulan, S. Investigating the usability pattern and constraints of pocket parks in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 50, 126647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MHURD. Notice on Promoting the Construction of Pocket Parks. 2022. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zhengce/zhengcefilelib/202208/20220808_767496.html (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Maury-Mora, M.; Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; Varela-Martínez, C. Urban green spaces and stress during COVID-19 lockdown: A case study for the city of Madrid. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoić, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Peng, Z.; Sun, Z. Change of Residents’ Attitudes and Behaviors toward Urban Green Space Pre- and Post- COVID-19 Pandemic. Land 2022, 11, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X. Reexamine the value of urban pocket parks under the impact of the COVID-19. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Qin, H.; Gou, Z. Effects of urban planning indicators on urban heat island: A case study of pocket parks in high-rise high-density environment. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, Z. Cooling effect of the pocket park in the built-up block of a city: A case study in Xi’an, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 23135–23154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Liang, G. Pedestrian-level gust wind flow and comfort around a building array–Influencing assessment on the pocket park. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, M.; Faizi, M.; Ekhlassi, A. Design possibilities of leftover spaces as a pocket park in relation to planting enclosure. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, F.; Pioppi, B.; Pisello, A.L. Pocket parks for human-centered urban climate change resilience: Microclimate field tests and multi-domain comfort analysis through portable sensing techniques and citizens’ science. Energy Build. 2022, 260, 111918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerishnan, P.B.; Maruthaveeran, S. Factors contributing to the usage of pocket parks―A review of the evidence. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Aguilar, F.; Yang, J.; Qin, Y.; Wen, Y. Predicting citizens’ participatory behavior in urban green space governance: Application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Hao, X.; Li, J. Effects of public participation on environmental governance in China: A spatial Durbin econometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 129042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Russo, A. Exploring the role of public participation in delivering inclusive, quality, and resilient green infrastructure for climate adaptation in the UK. Cities 2024, 148, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csomós, G.; Farkas, J.Z.; Szabó, B.; Bertus, Z.; Kovács, Z. Exploring the use and perceptions of inner-city small urban parks: A case study of Budapest, Hungary. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, Q.; Yue, L.; Wu, M.; Huang, R.; Yuen, K.F.; Su, R. A theoretical model for preventing marine litter behaviour: An empirical evidence from Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.B.N.; Vu, B.P.; Huynh, T.T.H.; Vu, D.H. Factors driving plastic-related behaviours: Towards reducing marine plastic waste in Hoi An, Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, R.B.; Terry, C. New social trails made during the pandemic increase fragmentation of an urban protected area. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 108993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansil, D.; Plecak, C.; Taczanowska, K.; Jiricka-Pürrer, A. Experience Them, Love Them, Protect Them—Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed People’s Perception of Urban and Suburban Green Spaces and Their Conservation Targets? Environ. Manag. 2022, 70, 1004–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ma, B.; Wei, S. Same gratitude, different pro-environmental behaviors? Effect of the dual-path influence mechanism of gratitude on pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J.; Goh, E. Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: An integrated structural model approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Moyle, B.D.; Jin, X. Fostering visitors’ pro-environmental behaviour in an urban park. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Dietz, T. Insights from early COVID-19 responses about promoting sustainable action. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nketiah, E.; Song, H.; Cai, X.; Adjei, M.; Obuobi, B.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Cudjoe, D. Predicting citizens’ recycling intention: Incorporating natural bonding and place identity into the extended norm activation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, P.; Assaker, G. COVID-19’s effects on future pro-environmental traveler behavior: An empirical examination using norm activation, economic sacrifices, and risk perception theories. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. The role of pandemic risk communication and perception on pro-environmental travel behavioral intention: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipeolu, A.A.; Ibem, E.O.; Fadamiro, J.A.; Fadairo, G. Factors influencing residents’ attitude towards urban green infrastructure in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 6192–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Jeong, C. Effects of pro-environmental destination image and leisure sports mania on motivation and pro-environmental behavior of visitors to Korea’s national parks. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, J.S.; Che, T. Understanding perceived environment quality in affecting tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviours: A broken windows theory perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, S.; Yu, M.S. Anticipated guilt and anti-littering civic engagement in an extended norm activation model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S. Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K. Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J.; Goh, E. What a load of rubbish! The efficacy of theory of planned behaviour and norm activation model in predicting visitors’ binning behaviour in national parks. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Barry, B. I Know What You Did: The Effects of Interpersonal Deviance on Bystanders. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, C.; Morrison, A.M.; Zhang, K. Fostering resident pro-environmental behavior: The roles of destination image and Confucian culture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Liang, L. Policy implications for promoting the adoption of electric vehicles: Do consumer’s knowledge, perceived risk and financial incentive policy matter? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 117, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaee, M.; Hoseini, S.M.; Malekmohammadi, I. Proposing a socio-psychological model for adopting green building technologies: A case study from Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. The moderating effect of subjective norm in predicting intention to use urban green spaces: A study of Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q. Encouraging the use of urban green space: The mediating role of attitude, perceived usefulness and perceived behavioural control. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A.; Eder, R. The influence of green space on community attachment of urban and suburban residents. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, J.M.E.; Smidts, A. The shape of utility functions and organizational behavior. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ma, W.; Tong, Z. How counterfactual thinking affects willingness to consume green restaurant products: Mediating role of regret and moderating role of COVID-19 risk perception. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretson, J.A.; Burton, S. Highly coupon and sale prone consumers: Benefits beyond price savings. J. Advert. Res. 2003, 43, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebardast, L.; Radaei, M. The influence of global crises on reshaping pro-environmental behavior, case study: The COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 151436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filgueira, T.O.; Castoldi, A.; Santos, L.E.R.; de Amorim, G.J.; de Sousa Fernandes, M.S.; do Nascimento Anastacio, W.d.L.; Campos, E.Z.; Santos, T.M.; Souto, F.O. The relevance of a physical active lifestyle and physical fitness on immune defense: Mitigating disease burden, with focus on COVID-19 consequences. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 587146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassenrath, C.; Diefenbacher, S.; Pfattheicher, S.; Keller, J. The potential and limitations of empathy in changing health-relevant affect, cognition and behaviour. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 33, 255–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Jiang, C.; Meng, L. The Relationship between Environmental Awareness, Habitat Quality, and Community Residents’ Pro-Environmental Behavior—Mediated Effects Model Analysis Based on Social Capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A. How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact urban green spaces? A multi-scale assessment of Jeddah megacity (Saudi Arabia). Urban For. Urban Green 2022, 69, 127493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Pro-environmental behavior on electric vehicle use intention: Integrating value-belief-norm theory and theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva, S.; Chankov, S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on e-Commerce Consumers’ Pro-Environmental Behavior BT—Dynamics in Logistics; Freitag, M., Kinra, A., Kotzab, H., Megow, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 474–485. [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Corral-Frías, N.S.; Frías-Armenta, M.; Lucas, M.Y.; Peña-Torres, E.F. Positive Environments and Precautionary Behaviors During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yan, R.; Song, Y. Analysing the impact of smart city service quality on citizen engagement in a public emergency. Cities 2022, 120, 103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, V.G.; Cotterill, S.; Anderson, J.; Phillipson, C.; Benton, J.S.; French, D.P. “I Would Never Come Here Because I’ve Got My Own Garden”: Older Adults’ Perceptions of Small Urban Green Spaces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhossein, M.; Baker, B.J.; Dousti, M.; Behnam, M.; Tabesh, S. Embarking on the trail of sustainable harmony: Exploring the nexus of visitor environmental engagement, awareness, and destination social responsibility in natural parks. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, L.; Fazio, A.; Pelloni, A. Pro-environmental attitudes, local environmental conditions and recycling behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Predicting residents’ adoption intention for smart waste classification and collection system. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 132399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yung, E.H.K.; Jayantha, W.M.; Chan, E.H.W. Elderly’s intention and use behavior of urban parks: Planned behavior perspective. Habitat Int. 2023, 134, 102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hu, D.; Swanson, S.R.; Su, L.; Chen, X. Destination perceptions, relationship quality, and tourist environmentally responsible behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. The place-based approach to recycling intention: Integrating place attachment into the extended theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MHURD. The Rapid Development of “Pocket Parks” in China. 2022. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/xinwen/gzdt/202208/20220823_767673.html (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Guo, W.; Chen, T.; Wei, Y. Intrinsic need satisfaction, emotional attachment, and value co-creation behaviors of seniors in using modified mobile government. Cities 2023, 141, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Kuang, T.; Yang, D.; Jia, Z.; Li, R.; Wang, L. The higher the cuteness the more it inspires garbage sorting intention? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liu-Lastres, B. Consumers’ dining behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Application of the Protection Motivation Theory and the Safety Signal Framework. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBS. The China Statistical Yearbook (CSY). 2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2023/indexch.htm (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hauff, S.; Hult, G.T.M.; Richter, N.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Pieper, T.M.; Ringle, C.M. The Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Past Practices and Recommendations for Future Applications. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F.J., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lucarelli, C.; Mazzoli, C.; Severini, S. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Examine Pro-Environmental Behavior: The moderating effect of COVID-19 beliefs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, R.; Baldassa, A.; Rossi, R.; Gastaldi, M. Potential long-term effects of COVID-19 on telecommuting and environment: An Italian case-study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 109, 103401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Q. Research on the Impact of Media Credibility on Risk Perception of COVID-19 and the Sustainable Travel Intention of Chinese Residents Based on an Extended TPB Model in the Post-Pandemic Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chen, B.; Long, Q.; Song, Y.; Yang, J. How is the acceptance of new energy vehicles under the recurring COVID-19—A case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. How COVID-19 reshaped quality of life in cities: A synthesis and implications for urban planning. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadiq, M.; Adil, M.; Paul, J. Organic food consumption and contextual factors: An attitude–behavior–context perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 3383–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 347 | 48.26 |

| Female | 372 | 51.74 | |

| Age | 18–24 years old | 153 | 21.28 |

| 25–34 years old | 232 | 32.27 | |

| 35–44 years old | 185 | 25.73 | |

| 45–59 years old | 101 | 14.05 | |

| 60 years old and above | 48 | 6.67 | |

| Education level | Primary school and less | 23 | 3.20 |

| High school | 188 | 26.15 | |

| University | 405 | 56.33 | |

| Master’s degree and above | 103 | 14.32 | |

| Monthly income | Below 2000 RMB | 79 | 10.99 |

| 2001–3000 RMB | 83 | 11.54 | |

| 3001–5000 RMB | 209 | 29.07 | |

| 5001–8000 RMB | 195 | 27.12 | |

| 8000–15,000 RMB | 119 | 16.55 | |

| 15,001 RMB and above | 34 | 4.73 | |

| Average monthly frequency of using pocket parks | Fewer than 3 times | 58 | 8.07 |

| 3–5 times | 171 | 23.78 | |

| 5–10 times | 158 | 21.97 | |

| 10–15 times | 198 | 27.54 | |

| More than 15 times | 134 | 18.64 | |

| Total | 719 | 100.00 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | Cronbach’s α | rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health risks | HR1 | 0.868 | 0.905 | 0.907 | 0.933 | 0.778 |

| HR2 | 0.870 | |||||

| HR3 | 0.832 | |||||

| HR4 | 0.756 | |||||

| Environmental quality | EQ1 | 0.859 | 0.904 | 0.905 | 0.929 | 0.722 |

| EQ2 | 0.840 | |||||

| EQ3 | 0.849 | |||||

| EQ4 | 0.848 | |||||

| EQ5 | 0.853 | |||||

| Perceived usefulness | PU1 | 0.871 | 0.841 | 0.847 | 0.904 | 0.760 |

| PU2 | 0.828 | |||||

| PU3 | 0.860 | |||||

| PU4 | 0.863 | |||||

| PU5 | 0.855 | |||||

| Awareness of consequences | AC1 | 0.852 | 0.853 | 0.867 | 0.900 | 0.694 |

| AC2 | 0.894 | |||||

| AC3 | 0.899 | |||||

| AC4 | 0.883 | |||||

| Ascription of responsibility | AR1 | 0.890 | 0.908 | 0.910 | 0.932 | 0.732 |

| AR2 | 0.881 | |||||

| AR3 | 0.843 | |||||

| AR4 | 0.896 | |||||

| Personal norms | PN1 | 0.894 | 0.901 | 0.904 | 0.931 | 0.770 |

| PN2 | 0.831 | |||||

| PN3 | 0.888 | |||||

| Intention to participate in pocket-park governance | IPPPG1 | 0.892 | 0.903 | 0.904 | 0.932 | 0.775 |

| IPPPG2 | 0.885 | |||||

| IPPPG3 | 0.867 | |||||

| IPPPG4 | 0.876 |

| Constructs | HR | EQ | PU | AC | AR | PN | IPPPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 0.833 | ||||||

| EQ | 0.374 | 0.850 | |||||

| PU | 0.506 | 0.480 | 0.856 | ||||

| AC | 0.484 | 0.417 | 0.447 | 0.882 | |||

| AR | 0.430 | 0.360 | 0.415 | 0.469 | 0.878 | ||

| PN | 0.429 | 0.417 | 0.540 | 0.481 | 0.447 | 0.871 | |

| IPPPG | 0.439 | 0.428 | 0.505 | 0.510 | 0.447 | 0.563 | 0.880 |

| Constructs | HR | EQ | PU | AC | AR | PN | IPPPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | |||||||

| EQ | 0.425 | ||||||

| PU | 0.573 | 0.530 | |||||

| AC | 0.545 | 0.460 | 0.492 | ||||

| AR | 0.483 | 0.396 | 0.456 | 0.518 | |||

| PN | 0.500 | 0.480 | 0.619 | 0.547 | 0.483 | ||

| IPPPG | 0.491 | 0.473 | 0.557 | 0.564 | 0.495 | 0.643 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | β | SE | t-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | HR→PU | 0.380 | 0.042 | 8.964 *** | Supported |

| H2 | EQ→PU | 0.338 | 0.042 | 7.972 *** | Supported |

| H4 | HR→AC | 0.309 | 0.046 | 6.757 *** | Supported |

| H5 | HR→AR | 0.183 | 0.049 | 3.744 *** | Supported |

| H6 | HR→PN | 0.077 | 0.053 | 1.458 | Not supported |

| H7 | EQ→AC | 0.210 | 0.048 | 4.398 *** | Supported |

| H8 | EQ→AR | 0.108 | 0.049 | 2.212 * | Supported |

| H9 | EQ→PN | 0.109 | 0.044 | 2.444 * | Supported |

| H10 | PU→AC | 0.190 | 0.050 | 3.797 *** | Supported |

| H11 | PU→AR | 0.150 | 0.053 | 2.842 ** | Supported |

| H12 | PU→PN | 0.298 | 0.057 | 5.229 *** | Supported |

| H13 | AC→AR | 0.269 | 0.049 | 5.474 *** | Supported |

| H14 | AC→PN | 0.189 | 0.053 | 3.565 *** | Supported |

| H15 | AR→PN | 0.163 | 0.050 | 3.253 ** | Supported |

| H16 | HR→IPPPG | 0.076 | 0.046 | 1.658 | Not supported |

| H17 | EQ→IPPPG | 0.101 | 0.048 | 2.098 * | Supported |

| H18 | PU→IPPPG | 0.141 | 0.059 | 2.377 * | Supported |

| H19 | AC→IPPPG | 0.185 | 0.051 | 3.602 *** | Supported |

| H20 | AR→IPPPG | 0.111 | 0.051 | 2.177 * | Supported |

| H21 | PN→IPPPG | 0.274 | 0.061 | 4.486 *** | Supported |

| Path | Standard Effect | Estimation | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR→PU→AC→PR→PN→IPPPG | Total effect | 0.468 | 0.037 | 0.396 | 0.541 |

| Direct effect | 0.079 | 0.038 | 0.004 | 0.154 | |

| Total indirect effects | 0.389 | 0.042 | 0.312 | 0.477 | |

| EQ→PU→AC→PR→PN→IPPPG | Total effect | 0.458 | 0.036 | 0.387 | 0.529 |

| Direct effect | 0.112 | 0.036 | 0.041 | 0.182 | |

| Total indirect effects | 0.346 | 0.039 | 0.277 | 0.425 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhong, J. From Health Risks to Environmental Actions: Research on the Pathway of Guiding Citizens to Participate in Pocket-Park Governance. Land 2024, 13, 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101612

Zhang J, Li Z, Zhong J. From Health Risks to Environmental Actions: Research on the Pathway of Guiding Citizens to Participate in Pocket-Park Governance. Land. 2024; 13(10):1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101612

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jing, Zhigang Li, and Jialong Zhong. 2024. "From Health Risks to Environmental Actions: Research on the Pathway of Guiding Citizens to Participate in Pocket-Park Governance" Land 13, no. 10: 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101612

APA StyleZhang, J., Li, Z., & Zhong, J. (2024). From Health Risks to Environmental Actions: Research on the Pathway of Guiding Citizens to Participate in Pocket-Park Governance. Land, 13(10), 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101612