Rice Terrace Experience in Japan: An Ode to the Beauty of Seasonality and Nostalgia

Abstract

1. Introduction

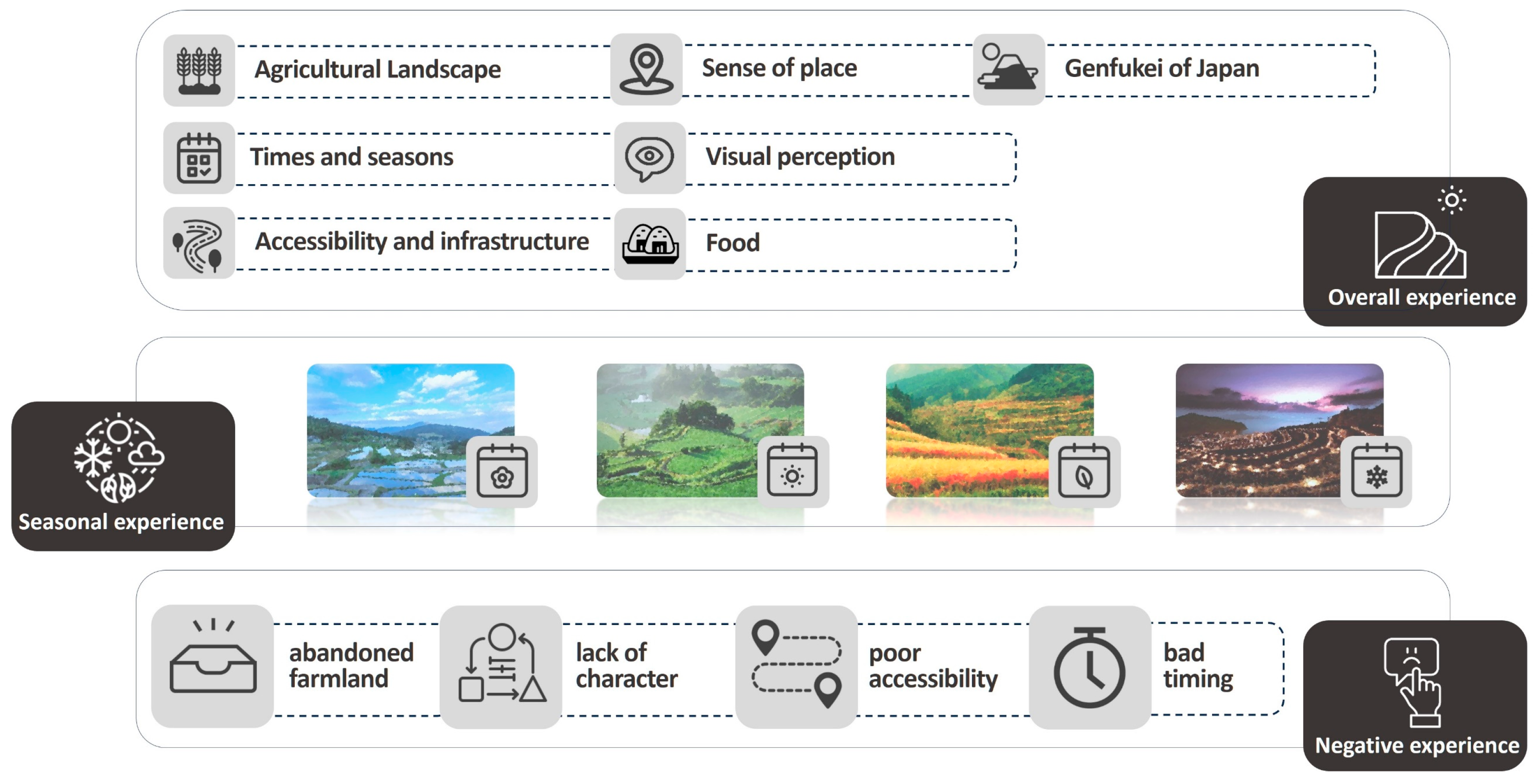

- What is the overall rice terrace experience in Japan?

- What are the key features of the rice terrace experience in different seasons?

- What factors lead to the negative rice terrace experience?

2. Background

2.1. Initiatives and Practices of Rice Terrace Conservation in Japan

2.2. Agricultural Heritage Landscapes and Tourism

2.3. Current Rice Terrace Research in the Tourism Context

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methods, Data, and Materials

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The Overall Rice Terrace Experience

4.3. Seasonal Experience

4.4. Causes of Negative Experiences

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Region | Prefecture | Name | Number of Reviews | Area | Type * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tohoku | Iwate | Yamabuki rice terraces | 32 | 5 ha | c |

| Kanayama rice terraces | 35 | 0.7 ha | b | ||

| Miyagi | Sawajiri rice terraces | 66 | 4.1 ha | c | |

| Yamagata | Owarabi rice terraces | 54 | 13 ha | c | |

| Kunugidaira rice terraces | 78 | 14 ha | c | ||

| Shikamura rice terraces | 132 | 12 ha | c | ||

| Kanto | Tochigi | Ishibatake rice terraces | 71 | 2.4 ha | c |

| Saitama | Terasaka rice terraces | 447 | 5.2 ha | b | |

| Chiba | Ohyama rice terraces | 2059 | 3.2 ha | c | |

| Chubu | Niigata | Gimyo rice terraces | 56 | 1.1 ha | b |

| Hoshitouge rice terraces | 1351 | 30 ha | b | ||

| Iwakubi Shoryu rice terraces | 103 | 16.7 ha | b | ||

| Toyama | Nagasaka rice terraces | 36 | 18.6 ha | c | |

| Ishikawa | Shiroyone Senmaida rice terraces | 5641 | 4 ha | c | |

| Tanada rice terraces | 42 | 20 ha | c | ||

| Fukui | Hibiki rice terraces | 53 | 3 ha | a | |

| Nagano | Inagura rice terraces | 378 | 30 ha | c | |

| Yokone Tanbo rice terraces | 99 | 3 ha | c | ||

| Obasute rice terraces | 185 | 40 ha | c | ||

| Aoni rice terraces | 38 | 4.2 ha | c | ||

| Gifu | Sakaori rice terraces | 277 | 170.5 ha | c | |

| Kamidaida rice terraces | 40 | 5 ha | c | ||

| Shizuoka | Kurumeki rice terraces | 67 | 7.7 ha | c | |

| Shirakashi rice terraces | 30 | 2 ha | b | ||

| Ishibu rice terraces | 152 | 4.2 ha | b | ||

| Aichi | Yotsuya rice terraces | 840 | 3.6 ha | c | |

| Kinki | Mie | Fukano rice terraces | 64 | 35 ha | c |

| Maruyama rice terraces | 216 | 7.2 ha | c | ||

| Sakamoto rice terraces | 53 | 21 ha | a | ||

| Shiga | Hata rice terraces | 78 | 13 ha | c | |

| Kyoto | Sodeshi rice terraces | 86 | 12 ha | c | |

| Osaka | Nagatani rice terraces | 31 | 30 ha | c | |

| Shimoakasaka rice terraces | 320 | 6.1 ha | c | ||

| Hyogo | Bekku rice terraces | 85 | 15.8 ha | b | |

| Isarigami rice terraces | 80 | 10.4 ha | c | ||

| Ueyama rice terraces | 72 | 3.1 ha | c | ||

| Okidani rice terraces | 42 | 23 ha | a | ||

| Nara | Inabuchi rice terraces | 553 | 24.1 ha | c | |

| Wakayama | Nakada rice terraces | 30 | 9 ha | b | |

| Aragijima rice terraces | 92 | 18.8 ha | c | ||

| Chugoku | Shimane | Sannouji rice terraces | 40 | 30 ha | c |

| Okayama | Kitasho rice terraces | 45 | 79 ha | c | |

| Ohaga-Nishi rice terraces | 110 | 49.7 ha | c | ||

| Hiroshima | Ini rice terraces | 338 | 12 ha | c | |

| Yamaguchi | Higashi Ushitobata rice terraces | 344 | 8 ha | c | |

| Kanoji rice terraces | 40 | 3 ha | b | ||

| Shikoku | Tokushima | Kashihara rice terraces | 86 | 5.1 ha | c |

| Kagawa | Nakayama rice terraces | 380 | 11.9 ha | c | |

| Ehime | Kashidani rice terraces | 35 | 3 ha | b | |

| Kochi | Yoshinobu rice terraces | 58 | 125 ha | b | |

| Takasu rice terraces | 32 | 92 ha | b | ||

| Kyushu&Okinawa | Fukuoka | Rokuri rice terraces | 38 | 5 ha | b |

| Hirouchi-Uebaru rice terraces | 126 | 5 ha | c | ||

| Tsuzura rice terraces | 196 | 9.88 ha | c | ||

| Take rice terraces | 102 | 12.5 ha | c | ||

| Saga | Warabino rice terraces | 55 | 59.5 ha | c | |

| Oura rice terraces | 168 | 35.4 ha | c | ||

| Eriyama rice terraces | 133 | 11 ha | c | ||

| Hamanoura rice terraces | 840 | 6.8 ha | c | ||

| Take rice terraces | 73 | 42.6 ha | c | ||

| Nagasaki | Onakao rice terraces | 36 | 8.4 ha | c | |

| Kasuga rice terraces | 120 | 11 ha | b | ||

| Doya rice terraces | 398 | 18.1 ha | c | ||

| Chijiwatake rice terraces | 37 | 23.4 ha | b | ||

| Onigi rice terraces | 247 | 22 ha | c | ||

| Kumamoto | Bansho rice terraces | 111 | 8 ha | c | |

| Ogi rice terraces | 164 | 1 ha | c | ||

| Oita | Uchinari rice terraces | 43 | 41.7 ha | c | |

| Miyazaki | Sakamoto rice terraces | 96 | 9.4 ha | c | |

| Okinawa | Koda rice terraces | 47 | 53 ha | c |

| Season | Concept | Rel. Freq (%) | Strength (%) | Prominence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | water | 19 | 59 | 4.5 |

| planting | 22 | 59 | 4.4 | |

| spring | 5 | 55 | 4.1 | |

| photo | 3 | 44 | 3.3 | |

| early | 7 | 42 | 3.2 | |

| feel | 4 | 37 | 2.8 | |

| people | 4 | 32 | 2.5 | |

| time | 16 | 30 | 2.3 | |

| best | 7 | 30 | 2.3 | |

| scenery | 11 | 30 | 2.3 | |

| Summer | summer | 16 | 66 | 6.2 |

| green | 11 | 50 | 4.7 | |

| sky | 5 | 31 | 3.0 | |

| visit | 15 | 31 | 2.9 | |

| nice | 6 | 28 | 2.7 | |

| best | 8 | 28 | 2.6 | |

| people | 4 | 26 | 2.5 | |

| view | 7 | 25 | 2.3 | |

| planting | 11 | 24 | 2.3 | |

| beautiful | 21 | 24 | 2.2 | |

| Autumn | amaryllis | 15 | 93 | 5.4 |

| cluster | 15 | 93 | 5.4 | |

| harvest | 19 | 69 | 4.0 | |

| golden | 6 | 64 | 3.7 | |

| autumn | 9 | 63 | 3.6 | |

| night | 4 | 54 | 3.1 | |

| wonderful | 5 | 50 | 2.9 | |

| light-up | 7 | 48 | 2.8 | |

| beautiful | 21 | 37 | 2.2 | |

| scenery | 10 | 37 | 2.2 | |

| Winter | winter | 23 | 71 | 12.9 |

| light-up | 14 | 33 | 6.0 | |

| colour | 5 | 22 | 4.1 | |

| night | 5 | 19 | 3.5 | |

| nice | 6 | 15 | 2.7 | |

| spectacular | 3 | 14 | 2.6 | |

| green | 5 | 11 | 2.1 | |

| beautiful | 20 | 11 | 2.1 | |

| best | 6 | 11 | 2.0 | |

| sky | 3 | 10 | 2.0 |

References

- Chen, Q.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z. Evolutionary Overview of Terrace Research Based on Bibliometric Analysis in Web of Science from 1991 to 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Nie, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhu, D. Advantages and Disadvantages of Terracing: A Comprehensive Review. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-K.; Chen, R.-S.; Yang, T.-Y. Application of a Tank Model to Assess the Flood-Control Function of a Terraced Paddy Field. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 59, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Chen, D.; Wang, L.; Daryanto, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, G.; Feng, T. Global Synthesis of the Classifications, Distributions, Benefits and Issues of Terracing. Earth Sci. Rev. 2016, 159, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Oh, C.H. Flora, Life Form Characteristics, and Plan for the Promotion of Biodiversity in South Korea’s Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System, the Traditional Gudeuljang Irrigated Rice Terraces in Cheongsando. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 1212–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J. Landscape Pattern and Sustainability of a 1300-Year-Old Agricultural Landscape in Subtropical Mountain Areas, Southwestern China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 20, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage Centre—World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Tilliger, B.; Rodríguez-Labajos, B.; Bustamante, J.; Settele, J. Disentangling Values in the Interrelations between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Landscape Conservation—A Case Study of the Ifugao Rice Terraces in the Philippines. Land 2015, 4, 888–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongxun, Z.; Qingwen, M.; Wenjun, J.; Moucheng, L. Values and Conservation of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces System as a GIAHS Site. J. Resour. Ecol. 2016, 7, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuma, H.; Bruggeman, A.; Zissimos, A.; Christoforou, I.; Eliades, M.; Zoumides, C. The Effect of Agricultural Abandonment and Mountain Terrace Degradation on Soil Organic Carbon in a Mediterranean Landscape. Catena 2020, 195, 104741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Hou, Y.; Long, Y.; Lei, M.; Guo, Y.; Nie, X.; Li, Z. Divergent Control and Variation in Bacterial and Fungal Necromass Carbon Respond to the Abandonment of Rice Terraces. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estacio, I.; Basu, M.; Sianipar, C.P.M.; Onitsuka, K.; Hoshino, S. Dynamics of Land Cover Transitions and Agricultural Abandonment in a Mountainous Agricultural Landscape: Case of Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippines. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 222, 104394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, M.A.; Herath, S. Quantifying the Role of Traditional Rice Terraces in Regulating Water Resources: Implications for Management and Conservation Efforts. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Calsamiglia, A.; Fortesa, J.; García-Comendador, J.; Lozano Guardiola, E.; García-Orenes, F.; Gago, J.; Estrany, J. The Role of Wildfire on Soil Quality in Abandoned Terraces of Three Mediterranean Micro-Catchments. Catena 2018, 170, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocco, G. Terraces as Traditional Agricultural Landscapes. Stability amidst Change. In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 450–456. ISBN 978-0-323-95133-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lesschen, J.P.; Cammeraat, L.H.; Nieman, T. Erosion and Terrace Failure Due to Agricultural Land Abandonment in a Semi-Arid Environment. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2008, 33, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Y. Relationship, Discourse and Construction: The Power Process and Environmental Impact of the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces as a World Heritage Site. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmik, P. Heritage Tourism: A Bibliometric Review. Anatolia 2021, 32, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, D.R.; Nishikawa, Y. Heritage Tourism in Rural Areas: Challenges for Improving Socio-Economic Impacts. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 15, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuamoud, I.N.; Libbin, J.; Green, J.; ALRousan, R. Factors Affecting the Willingness of Tourists to Visit Cultural Heritage Sites in Jordan. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 9, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Su, X.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Q. Research on Global Cultural Heritage Tourism Based on Bibliometric Analysis. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Marafa, L. Tourism Imaginary and Landscape at Heritage Site: A Case in Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China. Land 2021, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Agricultural Heritage Tourism Development and Heritage Conservation: A Case Study of the Samaba Rice Terraces, Yunnan, China. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, X. Review of Rice–Fish-Farming Systems in China—One of the Globally Important Ingenious Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). Aquaculture 2006, 260, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood Sustainability in a Rural Tourism Destination—Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, N.T.; Ghotbabadi, S.S.; Altafi, M. Agricultural Heritage as a Creative Tourism Attraction. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukamachi, K. Sustainability of Terraced Paddy Fields in Traditional Satoyama Landscapes of Japan. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 202, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, Y.; Fukamachi, K.; Morimoto, Y. Public Perception of the Cultural Value of Satoyama Landscape Types in Japan. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 7, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y. What Is Satoyama? Points for Discussion on Its Future Direction. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 7, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-A.; Minami, H. How Can We Better Understand the Place-Identity of a Regional Community?―A Psychological Approach. EDRA Build. Bridg. Connect. People Res. Des. 2000, 7, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M. An Introduction to the Preservation of Rice Terraces in Japan; Kokon Shoin: Tokyo, Japan, 1999; ISBN 978-4-7722-1346-2. [Google Scholar]

- FAO GIAHS around the World. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. GIAHS. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/giahs/giahsaroundtheworld/en/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Totti. Shiroyone Senmaida Rice Terraces (Wajima, Ishikawa) [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. 2020. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shiroyone_Senmaida_200906.jpg (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Kaneko, S. Iwakubi Shoryu Tanada [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. 2017. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iwakubi_shoryu_tanada.jpg (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- MAFF. About Hilly and Mountainous Areas. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/nousin/tyusan/siharai_seido/s_about/cyusan/ (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- MAFF. Census of Agriculture and Forestry 2005 Volume 7 Survey on Rural Areas and Rural Communities. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00500209&tstat=000001013499&cycle=0&tclass1=000001016977&stat_infid=000001203303&tclass2val=0 (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Qiu, Z.; Chen, B.; Takemoto, K. Conservation of Terraced Paddy Fields Engaged with Multiple Stakeholders: The Case of the Noto GIAHS Site in Japan. Paddy Water Environ. 2014, 12, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motonaka, M. Introduction to Rice Terrace Studies; Dai 1-han; Keiso Shobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; ISBN 978-4-326-99112-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kieninger, P.R.; Yamaji, E.; Penker, M. Urban People as Paddy Farmers: The Japanese Tanada Ownership System Discussed from a European Perspective. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAFF TSUNAGU TANADA Heritage—Passing Hometown Pride to the Future. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/nousin/tanada/sentei.html (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Carneiro, M.; Lima, J.; Silva, A. The Relevance of Landscape in the Rural Tourism Experience: Identifying Important Elements of the Rural Landscape. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jansen-Verbeke, M.; Min, Q.; Cheng, S. Tourism Potential of Agricultural Heritage Systems. Tour. Geogr. 2011, 13, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, T.; Qingwen, M.; Hui, T.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, H.; Fei, L. Progress and Prospects in Tourism Research on Agricultural Heritage Sites. J. Resour. Ecol. 2014, 5, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohafkan, P.; Altieri, M.A. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems: A Legacy for the Future; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koohafkan, P.; Altieri, M.; Initiative, G. A Methodological Framework for the Dynamic Conservation of Agricultural Heritage Systems; Land and Water Division, The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.; Min, Q.; Jiao, W.; Yuan, Z.; Fuller, A.M.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, B. Agricultural Heritage Systems Tourism: Definition, Characteristics and Development Framework. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donert, K.; Light, D. Karl DoneCapitalizing on Location and Heritage: Tourism and Economic Regeneration in Argentière La Bessée, High French Alps. In Proceedings of the Practicing Responsible Tourism: International Case Studies in Tourism Planning, Policy, and Development; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wu, B.; Cai, L. Tourism Development of World Heritage Sites in China: A Geographic Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. The Territoriality Paradigm in Cultural Tourism. Turyzm 2009, 19, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, I. Introducing Citation Topics. Available online: https://clarivate.com/blog/introducing-citation-topics (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Chan, J.H.; Iankova, K.; Zhang, Y.; McDonald, T.; Qi, X. The Role of Self-Gentrification in Sustainable Tourism: Indigenous Entrepreneurship at Honghe Hani Rice Terraces World Heritage Site, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1262–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Min, Q.; Zhang, C.; He, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L.; Tian, M.; Xiong, Y. Traditional Culture as an Important Power for Maintaining Agricultural Landscapes in Cultural Heritage Sites: A Case Study of the Hani Terraces. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 25, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, C. Locally Situated Rights and the ‘Doing’ of Responsibility for Heritage Conservation and Tourism Development at the Cultural Landscape of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Yoshino, H.; Okahashi, J.; Yoshida, M.; Inaba, N. Local Visions of the Landscape: Participatory Photographic Survey of the World Heritage Site, the Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieninger, P.R.; Penker, M.; Yamaji, E. Esthetic and Spiritual Values Motivating Collective Action for the Conservation of Cultural Landscape—A Case Study of Rice Terraces in Japan. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2013, 28, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qiu, Z.; Nakamura, K. Tourist Preferences for Agricultural Landscapes: A Case Study of Terraced Paddy Fields in Noto Peninsula, Japan. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 1880–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N. The Tourist Experience. Conceptual Developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Ryu, K.; Hussain, K. Influence of Experiences on Memories, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: A Study of Creative Tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stienmetz, J.; Kim, J.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Managing the Structure of Tourism Experiences: Foundations for Tourism Design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Stone, P. (Eds.) Contemporary Tourist Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-317-60550-8. [Google Scholar]

- Volo, S. Bloggers’ Reported Tourist Experiences: Their Utility as a Tourism Data Source and Their Effect on Prospective Tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 16, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosangit, C.; Hibbert, S.; McCabe, S. “If I Was Going to Die I Should at Least Be Having Fun”: Travel Blogs, Meaning and Tourist Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. The Dining Experience of Beijing Roast Duck: A Comparative Study of the Chinese and English Online Consumer Reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V. On Netnography: Initial Reflections on Consumer Research Investigations of Cyberculture. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1998, 25, 366. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinets, R.V. The Field behind the Screen: Using Netnography for Marketing Research in Online Communities. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. Sustainability and Indigenous Tourism Insights from Social Media: Worldview Differences, Cultural Friction and Negotiation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Shi, C.; Deng, B. Tourists’ Perceived Attitudes toward the Famous Terraced Agricultural Cultural Heritage Landscape in China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Cruickshank, B.F.; Dehuang, N. Stories Visitors Tell about Italian Cities as Destination Icons. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M.; Ruhanen, L.; Markwell, K. From Netnography to Autonetnography in Tourism Studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, N.J.; Rahinel, R.; Foster, M.K.; Patterson, M. Connecting in Megaclasses: The Netnographic Advantage. J. Mark. Educ. 2007, 29, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. A Netnographic Examination of Constructive Authenticity in Victoria Falls Tourist (Restaurant) Experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Pearce, P.L. Appraising Netnography: Towards Insights about New Markets in the Digital Tourist Era. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiras, A.; Eusébio, C. Perceived Image of Accessible Tourism Destinations: A Data Mining Analysis of Google Maps Reviews. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Neto, V.; Mondo, T.S.; Mundet, L.; Mendes-Filho, L. Service Quality Determinants in Historic Centers: Analysis of User Generated Content from the Perspective of the TOURQUAL Protocol. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Orr, S.A.; Kumar, P.; Grau-Bove, J. Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 on Heritage Sites in the UK Using Social Media Data. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.E.; Humphreys, M.S. Evaluation of Unsupervised Semantic Mapping of Natural Language with Leximancer Concept Mapping. Behav. Res. Methods 2006, 38, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leximancer LexiPortal 5 User Guide (Manual). Available online: https://www.leximancer.com/resources (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Haynes, E.; Garside, R.; Green, J.; Kelly, M.P.; Thomas, J.; Guell, C. Semiautomated Text Analytics for Qualitative Data Synthesis. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Jin, X. What Do Airbnb Users Care about? An Analysis of Online Review Comments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Seo, Y.; Kemper, J. Complaining Practices on Social Media in Tourism: A Value Co-Creation and Co-Destruction Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarathunga, W.H.M.S.; Cheng, L.; Weerathunga, P.R. Transitional Domestic Tourist Gaze in a Post-War Destination: A Case Study of Jaffna, Sri Lanka. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Is It Really Just a Social Construction?: The Contribution of the Physical Environment to Sense of Place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, H.; Fry, G.; Jauhiainen, J.S.; Jones, M.; Sooväli, H. Editorial: Landscape and Seasonality—Seasonal Landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2005, 30, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S. Human Activity in Landscape Seasonality: The Case of Tourism in Crete. Landsc. Res. 2005, 30, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Stoleriu, O.; Lupu, C. Wine Tourism: A Multisensory Experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, F.; Vorobjovas-Pinta, O.; Lewis, C. LGBTIQ + Identities in Tourism and Leisure Research: A Systematic Qualitative Literature Review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1476–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, W. Risk Assessment and Regulation Strategy of Farmland Marginalization: A Case Study of Mengjin County, Henan Province. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 892665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, K. Landscape Needs and Notions: Preferences, Expectations, Leisure Motivation, and the Concept of Landscape from a Cross-Cultural Perspective; Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL: Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 2006; ISBN 3-905621-31-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka, R.; Ito, K.; Miyake, Y.; Uchiyama, Y. Cultural Ecosystem Services from the Afforestation of Rice Terraces and Farmland: Emerging Services as an Alternative to Monoculturalization. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 497, 119481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural Values and Sustainable Forest Management: The Case of Europe. J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, K.; Lerch, D.; Müller, A.-K.; Simons, N.K.; Blüthgen, N.; Harnisch, M. Flower Power in the City: Replacing Roadside Shrubs by Wildflower Meadows Increases Insect Numbers and Reduces Maintenance Costs. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobster, P.H.; Nassauer, J.I.; Daniel, T.C.; Fry, G. The Shared Landscape: What Does Aesthetics Have to Do with Ecology? Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartmann, F.M.; Frick, J.; Kienast, F.; Hunziker, M. Factors Influencing Visual Landscape Quality Perceived by the Public. Results from a National Survey. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 208, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, B.T.; Zasada, I.; Koetse, M.J.; Ungaro, F.; Häfner, K.; Verburg, P.H. A Comparative Approach to Assess the Contribution of Landscape Features to Aesthetic and Recreational Values in Agricultural Landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 17, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C. Whither Scenic Beauty? Visual Landscape Quality Assessment in the 21st Century. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J.; Marques, C.P.; Loureiro, S.M.C. The Dimensions of Rural Tourism Experience: Impacts on Arousal, Memory, and Satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, S.; Rita, P.; Coelho, J. Stripping Customers’ Feedback on Hotels through Data Mining: The Case of Las Vegas Strip. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, J.M.; Hoogendoorn, G. Exploring the Climate Sensitivity of Tourists to South Africa through TripAdvisor Reviews. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2019, 101, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhyoff, G.J.; Wellman, J.D. Seasonality Bias in Landscape Preference Research. Leis. Sci. 1979, 2, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, J. Effects of Seasonality on Visual Aesthetic Preference. Landsc. Res. 2022, 47, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Hendriks, K. Seasonality of Agricultural Landscapes: Reading Time and Place by Colours and Shapes. In Seasonal Landscapes; Palang, H., Sooväli, H., Printsmann, A., Eds.; Landscape Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 7, pp. 103–126. ISBN 978-1-4020-4982-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schüpbach, B.; Junge, X.; Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Walter, T. Seasonality, Diversity and Aesthetic Valuation of Landscape Plots: An Integrative Approach to Assess Landscape Quality on Different Scales. Land Use Policy 2016, 53, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandiffio, A. Parametric Definition of Slow Tourism Itineraries for Experiencing Seasonal Landscapes. Application of Sentinel-2 Imagery to the Rural Paddy-Rice Landscape in Northern Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. A Sense of Place: Place, Culture and Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Sun, Y.; Wall, G.; Min, Q. Agricultural Heritage Conservation, Tourism and Community Livelihood in the Process of Urbanization—Xuanhua Grape Garden, Hebei Province, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Cabeza, M. Rediscovering the Potential of Indigenous Storytelling for Conservation Practice. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukio, Y.; Kazem, V.; Takayuki, K. Tourism Development in Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System Areas in Japan: Making Stories and Experience-Based Products. J. Resour. Ecol. 2023, 14, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for Success in Rural Tourism Development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, Place and Authenticity: Local Food and the Sustainable Tourism Experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.; Laguna, M.; Palacios, A. The Role of Motivation in Visitor Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence in Rural Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Count | Month | Count | Season | Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 3 | Jan | 361 | Spring | 2416 | |

| 2014 | 2 | Feb | 338 | Summer | 2844 | |

| 2015 | 28 | Mar | 380 | Autumn | 2651 | |

| 2016 | 141 | Apr | 591 | Winter | 1087 | |

| 2017 | 524 | May | 1445 | |||

| 2018 | 995 | Jun | 900 | Rating | Count | |

| 2019 | 1612 | Jul | 835 | 5 stars | 3891 | |

| 2020 | 1149 | Aug | 1109 | 4 stars | 3473 | |

| 2021 | 1489 | Sep | 1171 | 3 stars | 1366 | |

| 2022 | 1840 | Oct | 822 | 2 stars | 179 | |

| 2023 | 1215 | Nov | 658 | 1 star | 89 | |

| Dec | 388 | |||||

| Overarching Themes | Focused Codes | Free Codes | Count * | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural landscape, sense of place, and Genfukei | land abandonment and poor maintenance | fallow fields; weeds; poor maintenance | 43 | There were many fields left fallow and full of weeds. |

| inappropriate behaviors | bad manners; illegal dumping; trespassing | 12 | When I walked with my 2-year-old daughter, a local man driving a light truck honked at us for a long time, which was scary and made my daughter cry. | |

| loss of Genfukei | unauthentic landscape; no trace of the past | 13 | There is no trace of the past. | |

| Times and seasons | bad timing | bad time; wrong season | 31 | I did not have a good impression of it, probably because it was the wrong time. |

| right timing without expected scenery | not as expected; disappoint | 25 | There were surprisingly few cluster amaryllis, and I was disappointed. | |

| Visual perception | lack of character | ordinary; nothing special | 35 | There is nothing spectacular. |

| small scale | small; few terraces | 18 | It is so small that you will be disappointed. | |

| artificial traces | trash; not natural | 11 | I cannot take a nice photo with plastic piping and electric fences stuck everywhere. | |

| lack of viewpoints | no viewpoints; bad location | 5 | It would be nice to have a place to take photos with the view of the rice terraces. | |

| Accessibility and facilities | poor road conditions | narrow; dangerous; inconvenient; steep; no signs | 35 | The road is narrow and inconvenient. Road signs also need to be improved. |

| difficulties in parking | small parking lot; no parking space; inconvenient | 13 | The parking lot guidance is the worst. There is still much space for buses, but no space left for passenger cars. | |

| a short length of stay | not much to do; boring; short stay | 8 | It would be better if I could kill 20 min here. | |

| over-tourism | too many people; over-developed | 7 | It has become too touristy and has no taste: a miniature garden or a diorama-like creation. | |

| unreasonable charges | expensive fees; unreasonable charges | 5 | It does not make sense to pay 100 yen per person for every service separately, even for donations. | |

| bad service | food service; shopping service | 5 | I feel uncomfortable with the way the lady at the cafeteria treats me. | |

| lack of infrastructure | toilet; trash bins; lighting; bench | 5 | I wish there was a bench so I could sit and relax. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Furuya, K. Rice Terrace Experience in Japan: An Ode to the Beauty of Seasonality and Nostalgia. Land 2024, 13, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010064

Wang Q, Yang X, Liu X, Furuya K. Rice Terrace Experience in Japan: An Ode to the Beauty of Seasonality and Nostalgia. Land. 2024; 13(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qian, Xiaoqi Yang, Xinyu Liu, and Katsunori Furuya. 2024. "Rice Terrace Experience in Japan: An Ode to the Beauty of Seasonality and Nostalgia" Land 13, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010064

APA StyleWang, Q., Yang, X., Liu, X., & Furuya, K. (2024). Rice Terrace Experience in Japan: An Ode to the Beauty of Seasonality and Nostalgia. Land, 13(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13010064