Collective Resource Management and Labor Quota Systems for Sustainable Natural Resource Management in Semi-Arid Ethiopia

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Design Principles | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Clearly defined user and resource boundaries | Clear boundaries between legitimate CPR users and non-users are present. Clear boundaries that define a resource system and separate it from the larger biophysical environment are present. |

| 2. Congruence of appropriation and provision rules 1 with local conditions | (i) The costs incurred by CPR users are proportional to the benefits they receive via their participation. The rules to determine (i), and (ii) deal with appropriation and provision problems, are congruent with local social and environmental conditions 2. |

| 3. Collective-choice rules | Most individuals affected by appropriation (harvesting from CPRs) and provision (protection of CPRs) rules are authorized to participate in making and modifying their rules. |

| 4. Monitoring users and resources | Monitors, who audit appropriation and provision levels of CPR users and biophysical conditions of the resources, are accountable to the users or are the users themselves. |

| 5. Graduated sanctions | Sanctions for rule violations are initially very low but become stronger if a user repeatedly violates a rule. |

| 6. Conflict-resolution mechanisms | There are rapid and low-cost local arenas to resolve conflicts among users or between users and officials. |

| 7. Minimal recognition of rights by the government (Independence) | CPR users’ rights to make and devise their own rules are recognized and not challenged by external governmental authorities. |

| For resources that are parts of larger systems: | |

| 8. Nested institutionalization | When a CPR is closely connected to a larger social-ecological system, governance activities (e.g., appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution) are organized in multiple nested layers. |

2. History of Natural Resource Management in Ethiopia

2.1. Natural Resource Management in Ethiopia

2.2. Participatory Natural Resource Management in Tigray

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preliminary Survey

3.2. Study Area and Methodology

4. Results

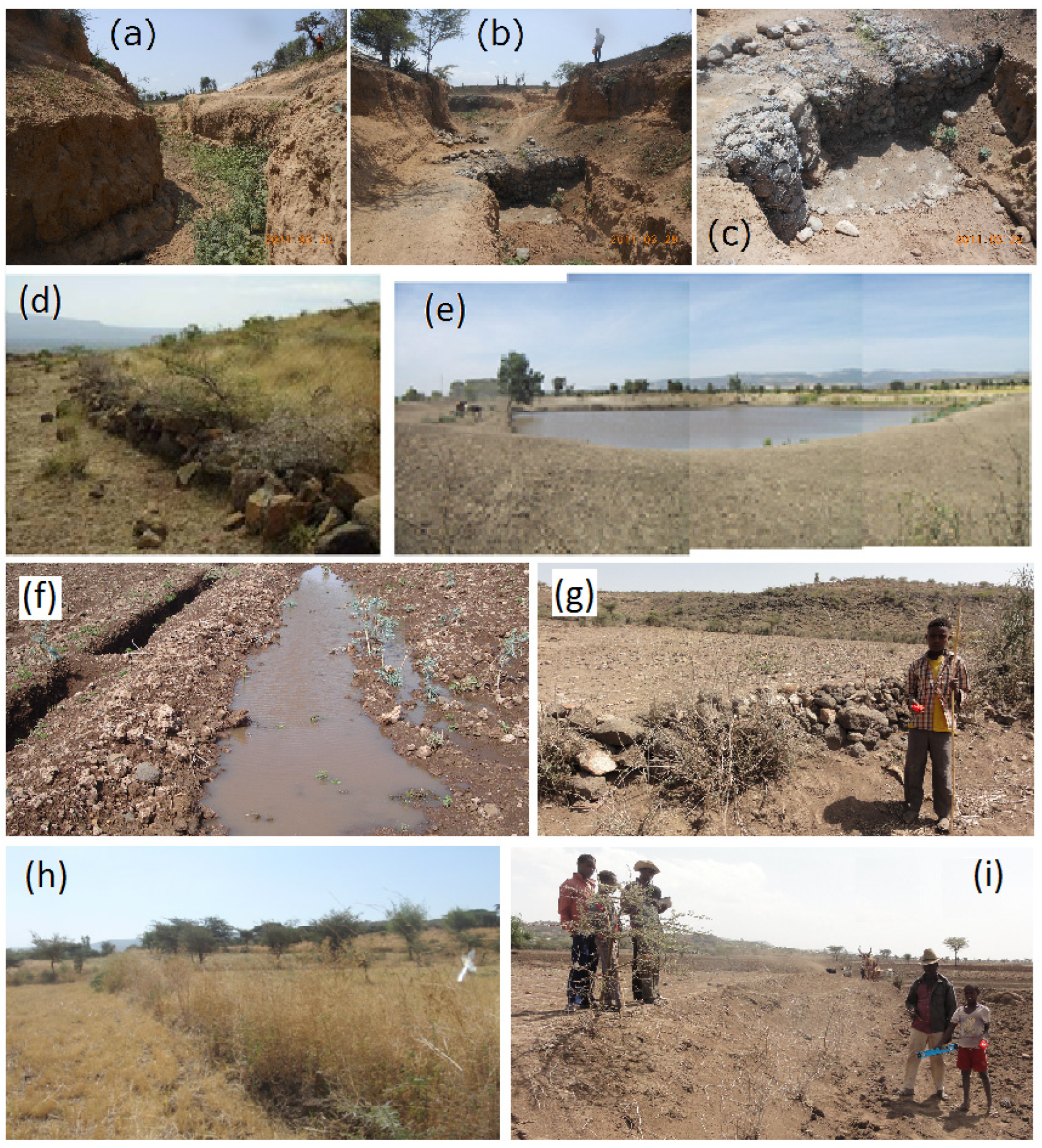

4.1. Natural and Life Resource Management in the Boset District

4.2. Determinants of Natural and Life Resource Management

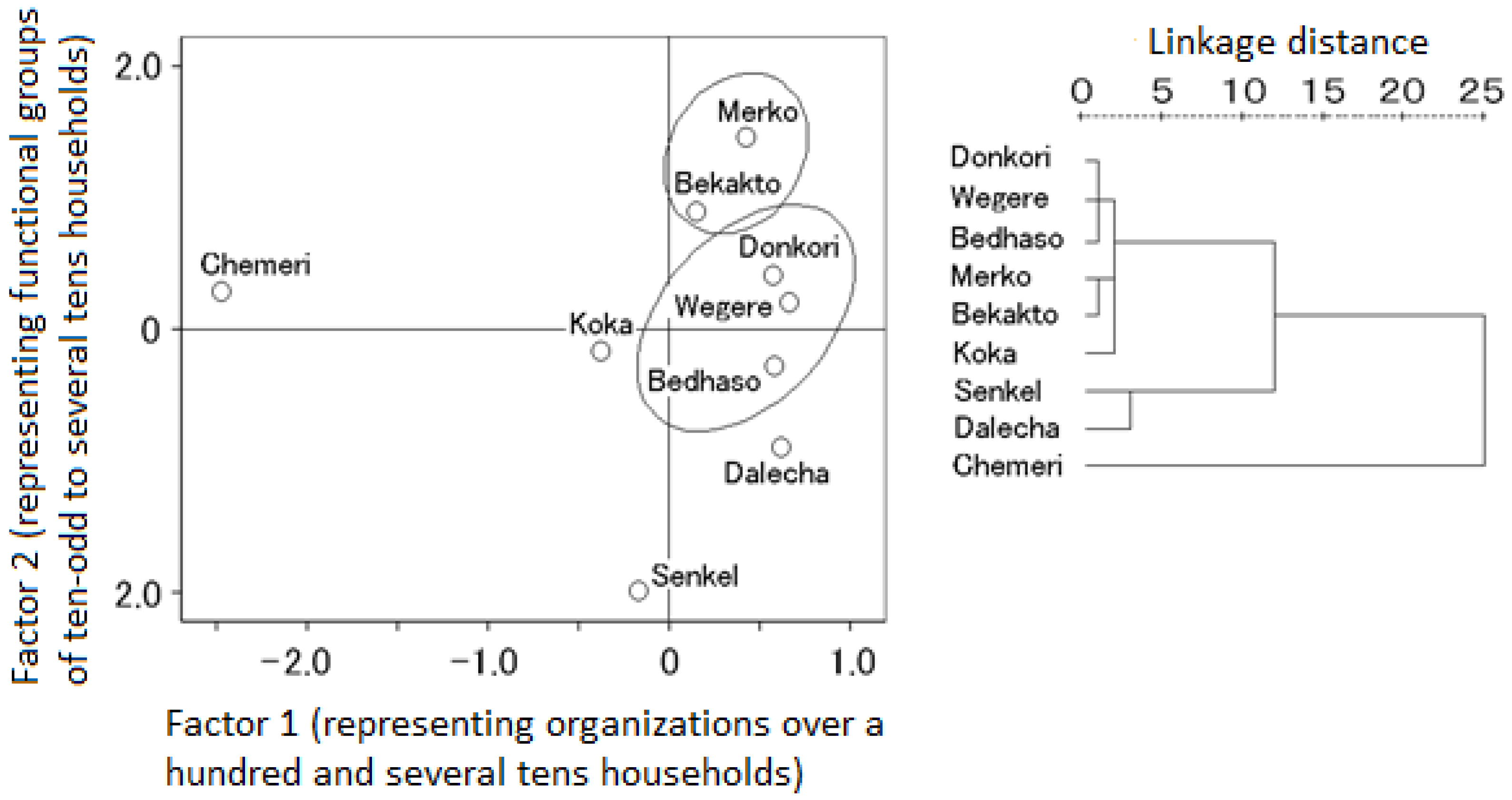

4.2.1. Canonical Discriminant Analysis

4.2.2. Principal Component Analysis

4.3. Village Organizations Controlling Collective Work

4.3.1. Iddir Labor Quota System

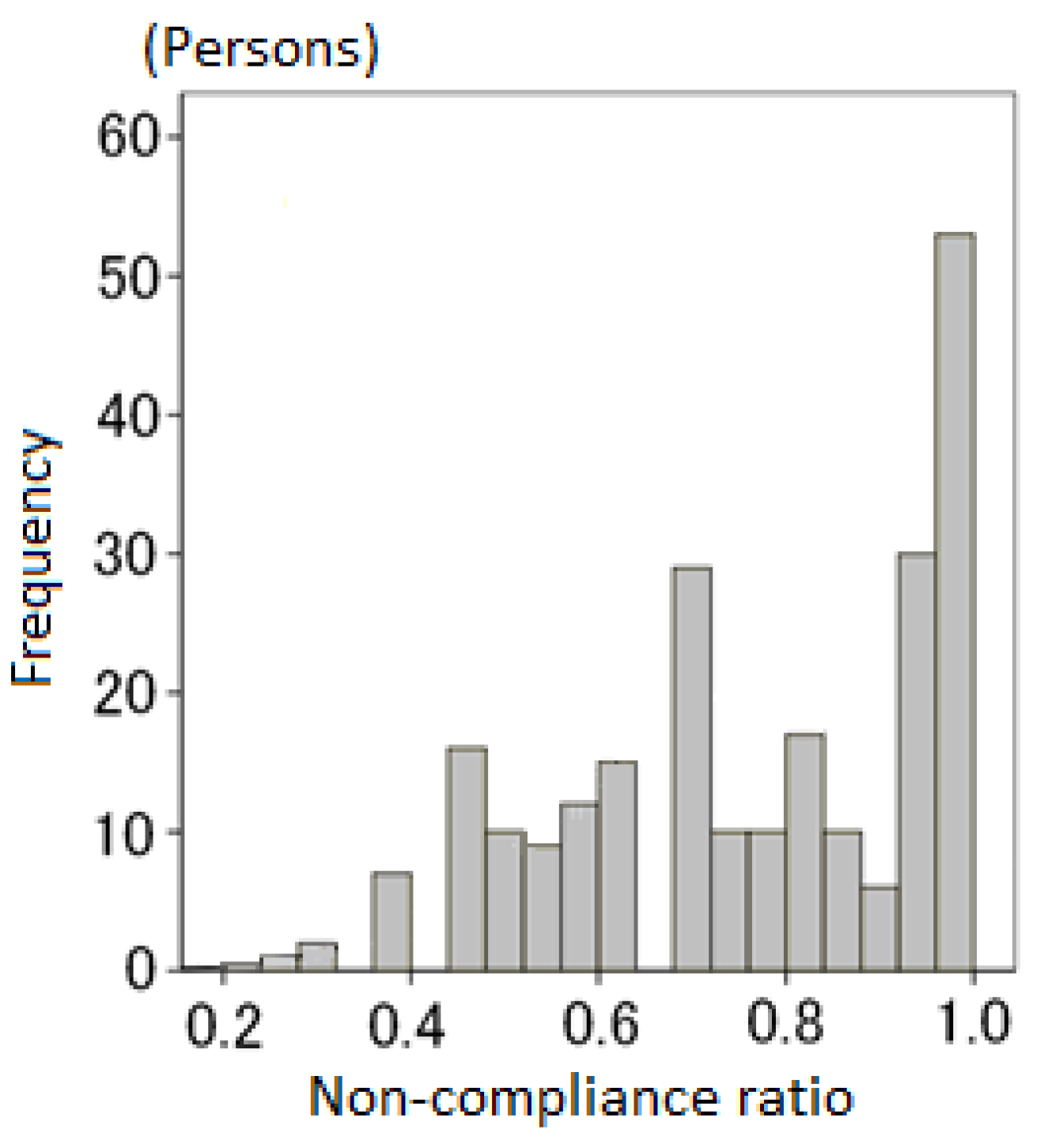

4.3.2. Multiple Regression Analyses and Categorical Principal Component Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Labor Quota System in the Semi-Arid Ethiopian Rift Valley

5.2. Local Administration System in the Semi-Arid Ethiopian Rift Valley

5.3. Institutional Arrangement in Two Semi-Arid Ethiopia Regions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A common-pool resource, that is, a regime before allocating property rights to a group, is a category of goods in which one person’s use subtracts from another’s use (subtractability) and from which it is difficult to exclude potential beneficiaries (excludability) [1,2]. In contrast, common property, used elsewhere in this article, allocates rights to a group, including ownership, management, use, exclusion, and access to a shared resource. |

| 2 | Although it is generally called cash-for-work when cash is supplied in exchange for participation, this study does not distinguish between grain and cash and refers to them both as food-for-work (FFW). |

| 3 | Associated with the recent development of the rural economy, villagers frequently go to towns/cities. Many farmers grow cash crops such as vegetables, and trucks and horse/donkey carts come a mile into the village to carry harvested crops. In the expansion process, gullies break roads, taking a severe toll on villagers’ daily lives. |

| 4 | In Jimma City, 82% of the total household heads who responded to the survey were members of any iddir, and 93% of the iddir members, or 77% of the respondents, were willing to join iddir-based health insurance schemes [37]. |

| 5 | Tesfaye [38] surveyed urban iddirs in Addis Ababa and Adama and quoted two contradictory opinions: ACORD-Ethiopia [43] (p. 9), an international NGO, asserted that iddir leadership is not accountable or transparent in general. In contrast, Aredo [44] (p. 3) has argued that, of all organizations in Ethiopia, iddirs can be said to be the most egalitarian, broad-based, transparent, and accountable, although they are far from ideal. |

| 6 | In the study area, the Boset district (Oromia region), several hamlets (gott, Amharic) constitute an administrative village (kebele). A hamlet in the Tigray and Amhara regions is called a qushet or gott, respectively [46] (p. 33). In the Amhara [47] (p. 134) and Tigray [48] (p. 69) regions and in the Boset district, 3–5 hamlets constitute a village. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | In an Afro-alpine area (Menz district) in the Central Ethiopian Highlands, pioneer fathers of Menz began the indigenous management of the Guassa grass (Festuca abyssinica) area in the seventeenth century [60]. The Guassa areas were periodically exclosed to regenerate grasses by their rules. The rules were enforced with punishment. Under the Irist land rights and the tenure system prevailing in Menz, only people who could trace their descent from the pioneer fathers used the Guassa area [60]. In the semi-arid Ethiopia Rift Valley, swampy lands and hillsides unsuitable for crop cultivation were regarded as communal lands, which landlords managed. In the early days, a hamlet (gott) comprised pioneer settlers and their paternal relatives. Under the Irist system, gott was a unit of communal land use; dwellers of two to three gotts exclusively used one communal land area. In the Boset district, communal lands were opened to tenants; villagers used them without the landlord’s permission [31]. |

| 9 | A survey conducted in the Amhara region in 2000 [65] found that, out of 133 sample household heads, 35–40% of the farmers voluntarily participated in the cropland SWC work. The remainder, over 50%, asserted that they participated simply because the village administration and the development agents (DAs; extension workers) forced them to do so. |

| 10 | The Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) left the decision to distribute communal lands to each village’s (kebele, i.e., PA’s) discretion. The Amhara and Oromia regions still entrusted communal land management to PAs. The Amhara region decided to distribute the land to households in 2003 (see Note 13 for details). The Tigray region took a mixed approach, and part of the less unutilized communal hillsides has been distributed to landless/deprived households since 2011 [66]. |

| 11 | The average number of micro-watershed association members was 7 [69] (p. 10). |

| 12 | From 2011 to 2015, the micro-watershed associations in the three villages constructed hillside SWC (terraces with trenches) and cropland SWC (soil bunds) having a mean length of 6 km. Parts of communal hillsides in two villages were exclosed and reforested every year. However, the survival rates of the seedlings planted were nearly zero, while the grazing areas in the three villages decreased by 54%, and the forest areas increased by 188% between 2009 and 2016. |

| 13 | At this point, there is a contrast between what happened in Tigray and the other regions. Even in other regions, examples of hamlets managing grazing land and natural resources were observed, e.g., communal grazing land management by gotts in Amhara [47]. North and South Wollo zones (Amhara region) are in the semi-arid Highlands. After severe droughts damaged this area in 1984 and 1985, many domestic and international NGOs opened offices and began relief activities in Wollo. To resolve confusion about communal land management in the 1980s, the following trials were undertaken in Wollo [72]. The Amhara regional government indicated it would not entrust communal land management to PAs, which did not show interest in communal hillside management. The regional government would instead assign exclosure and user-rights of communal hillsides to relevant groups or individual households. Two primary opinions were offered. Based on the achievement of the Meket community-based natural resource management project (1996–1998), an international NGO, SOS-Sahel, suggested entrusting the user-rights to the “informal local community (kire; Amhara)”. Kires are indigenous hamlet-level (gott) organizations that manage funeral occasions and make informal insurance arrangements (similar to iddirs in other regions [73]). Participatory land use planning and implementation (PLUPI) was undertaken on a hamlet basis. In the hamlet where a PLUPI was approved, the PA and district agricultural office issued the kire association a certificate to guarantee the user-rights of the resources in the exclosure hillsides. This significantly increased the kire association members’ incentive to conserve the communal hillsides (1% level [74]). SOS-Sahel exclosed 523 ha of hillsides in 50 hamlets from 1996 to 1998 [75]. This was a trial of entrusting the administration to the entrepreneurship farmers’ groups. However, the regional government did not give consent for this trial. The regional governmental officers strongly opposed granting the user-rights to an informal hamlet-level community organization, i.e., a kire association [72,76]. From 1998 to 2001, the Amhara government distributed 9600 ha of communal hillsides to 55,000 households. Of that, however, 857 ha (8% of the distributed communal hillsides) was reforested until 2001. Considering more than half of the distributed hillsides were already reforested during the socialist regime period, the reforestation rate was low. The landless/deprived households were generally interested in croplands but not in hillsides. Thus, they were indifferent to hillside conservation, which was a major factor in the low reforestation rate [72]. |

| 14 | Oniki and Negusse [78] surveyed 113 qushets (hamlets) in five tabias (PAs), southern Tigray, in 2013. All the sample qushets had communal forests, and 44% of the qushets planted trees in communal forests from 2003 to 2012. By enclosure, 67–73% of the surveyed communal forests prohibited grazing by livestock. Most communities hired guards, or people took shifts as guards. The average daily wage for hiring a guard to protect a community forest was 9.9 birrs. The average annual fee collected from qushet members for communal land protection was 19.9 birrs per household. Compared to the average value of Eucalyptus timber (41 birrs per cord) and the average wage for a farm worker (32.6 birrs per day), the cost of a guard was not high [78]. |

| 15 | Kumasi and Asenso-Okyere [80] found that those who mobilized villagers to undertake collective work were the (i) tabia head (or PA head; 41% of the respondents), (ii) development group leader (31%); and (iii) extension workers (28%). The regional government initially established a development group for the diffusion of innovative agricultural technologies; later, TPLF modified it to mobilize villagers into development activities at a hamlet level [81] (p. 13). About 45% of the respondents did not think they faced any challenges participating in compulsory free labor for community work. However, more than half of the respondents mentioned various activities that conflicted with collective work, including domestic work (22%), taking care of livestock (19%), and other business activities (13%). Most respondents (78%) had not observed any form of resistance to compulsory free labor for community work. Conversely, the other 22% felt resistance to participation. These villagers’ complaints and the various problems that occurred were mediated through discussions with the entire community (39%), through the use of group elders in a conflict resolution committee (30%), through the use of the bylaw as a point of reference in a local court (16%), or through the involvement of the PA (15%). |

| 16 | Using a sociometry method [83], Mukai [31] explored the village unit or organization that had a dense interpersonal connection in the Boset district. He asked villagers who had close personal relationships in their daily life, such as (i) agricultural activities and livestock rearing, (ii) labor exchange, (iii) religious affairs, (iv) money transactions, (v) mediation of disputes and conflicts, and (vi) marriages and funerals. He found that most aspects of villagers’ daily lives were concluded within the sphere of hamlets (gotts). Compared to other village and kinship units, e.g., paternal relatives and villages, more power was concentrated in hamlets (gotts), i.e., many villagers in a hamlet commonly recognize the same leader as an influential person in the hamlet [31]. He concluded that hamlets in the Boset district had an affluent social capital similar to that of the Tigray region. |

| 17 | Taking Merko Odalega village as an example (Figure 2), the former Merko village, located in the northern half of Merko Odalega, and the former Odalega village, located in the southern half, merged in 1996. The former Merko village comprises three gotts, Merko, Goro, and Sala. The former Odalega village consists of three gotts, Adao, Warka, and Odalega. Five iddirs in Merko Odalega were established from 1953 to 1988. A household head can be a member of an iddir. A gott is a unit of the members of an iddir; the Merko gott comprises the Merko iddir; the Goro and Sala gotts comprise the Sala iddir; the Adao gott comprises the Adao iddir; the Warka gott comprises the Warka iddir; and the Odalega gott comprises the Odalaga iddir. |

| 18 | The mean annual rainfall is 881 mm (Ejere rainfall station; 1976–2013) in the northern Rift margin area and 874 mm (Welenchiti rainfall station; 1992–2013) in the southern Valley floor area. |

| 19 | The major crops in the mid-altitude moist sub-area and true highland area in the catchments area are wheat, tef, and maize, whereas those in the mid-altitude dry sub-area are sorghum, tef, and maize [86]. |

| 20 | PAs hold regular and emergency meetings in a primary school room, where every PA member can participate and make remarks. Every iddir in Boset holds a regular meeting every other week, where they collect membership fees and have discussions. |

| 21 | During the socialist regime period, farmland was reallocated to PA members twice a year. However, since the socialist regime collapsed, no land has been reallocated in the Boset district. Even after marrying and becoming an independent new household, young men can only hold their lands if their parents admit it. These landless and deprived male household heads aged in their 20s or early 30s and widow household heads, enrolled in youth and women’s associations, respectively, that were acknowledged by the PA [31]. |

| 22 | Of these, two were without any external support: one was by a youth association and the other was by a user group (in Buta Bedhaso; Figure 2), which began the hillside exclosure (20 ha) in 2006 to protect a communal pond and water-harvesting tank from sedimentation of eroded soil. On the third hillside, a natural resource package program began in 2003 supported by UNDP, and hillside exclosure and reforestation continued in 2005 and 2006 with FFW payment. |

| 23 | Low seedling survival rates can be partly attributed to the design failure of the reforestation program. On the hillsides in the Boset district, very weakly developed mineral soils, classified as Leptosols or Regosols, are partially extended. These soils can be found on hard rocks with less than 10 cm soil depth [90], and are unsuitable for tree seedling plantation. Leptosols/Regosols, covering nearly 27% of the Ethiopian landmass, are in upper slope positions [91]. The steep slope and shallow soil depth were the primary factors limiting the suitability of land for reforestation [92]. Any soil having a depth of less than 50 cm is considered unsuitable for most perennial crops, including tree seedlings, while soils having a depth of over 80 cm are preferable [93]. Most Leptosol/Regosol areas are presently grazing lands, and the most suitable vegetation restoration option appears to be a simple exclosure. |

References

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Design Principles of Robust Property Rights Institutions: What Have We Learned? In Property Rights and Land Policies; Ingram, G.K., Hong, Y.H., Eds.; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, KS, USA, 2009; pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, J.; Tollison, R.; Tullock, G. (Eds.) Toward a Theory of Rent Seeking Society; Texas A and M University Press: College Station, TX, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Damania, R.; Hatch, J. Protecting Eden: Markets or Government? Ecol. Econ. 2005, 53, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Vandenreyken, H.; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Deckers, J.; Haile, M.; Salles, C.; Govers, G. Rainfall Erosivity and Variability in the Northern Ethiopian Highlands. J. Hydrol. 2005, 311, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haregeweyn, N.; Tsunekawa, A.; Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Tsubo, M.; Meshesha, D.T.; Schütt, B.; Adgo, E.; Tegegne, F. Soil Erosion and Conservation in Ethiopia: A Review. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2015, 39, 750–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Haile, M.; Deckers, J. Dynamics of Soil Erosion Rates and Controlling Factors in the Northern Ethiopian Highlands: Towards a Sediment Budget. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2007, 33, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaye, L.; Bharti, R. Soil erosion and sediment yield assessment using RUSLE and GIS-based approach in Anjeb watershed, Northwest Ethiopia. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiagbor, G.; Forkuo, E.K.; Laari, P.; Aabeyir, R. Modeling Soil Erosion Using RUSLE and GIS Tools. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 2, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beek, C.L.; Elias, E.; Yihenew, G.S.; Heesmans, H.; Tsegaye, A.; Feyisa, H.; Tolla, M.; Melmuye, M.; Gebremeskel, Y.; Mengist, S. Soil Nutrient Balances under Diverse Agro-Ecological Settings in Ethiopia. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2016, 106, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ittersum, M.K.; Van Bussel, L.G.; Wolf, J.; Grassini, P.; Van Wart, J.; Guilpart, N.; Claessens, L.; De Groot, H.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; et al. Can Sub-Saharan Africa Feed Itself? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14964–14969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.; Frankl, A.; Beeckman, H.; Mesfin, G.; Hendrickx, M.; Guyassa, E.; Nyssen, J. Northern Ethiopian Afro-Alpine Tree Dynamics and Forest-Cover Change since the Early 20th Century. Land Degrad. Dev. 2014, 26, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habte, D.G.; Belliethathan, S.; Ayenew, T. Evaluation of the Status of Land Use/Land Cover Change Using Remote Sensing and GIS in Jewha Watershed, Northeastern Ethiopia. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angassa, A. Effects of Grazing Intensity and Bush Encroachment on Herbaceous Species and Rangeland Condition in Southern Ethiopia. Land Degrad Dev. 2014, 25, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuria, W.; Veldkamp, E.; Corre, M.D.; Mitiku, H. Restoration of Ecosystem Carbon Stocks Following Exclosure Establishment in Communal Grazing Lands in Tigray, Ethiopia. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.; Arnold, G.; Tomás, S.V. A Review of Design Principles for Community-based Natural Resource Management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Eco. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoben, A. Paradigms and Politics: The Cultural Construction of Environmental Policy in Ethiopia. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, K.; Ludi, E. The Performance of Selected Soil and Water Conservation Measures: Case Studies from Ethiopia and Eritrea. Catena 1999, 36, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakew, D.; Carucci, V.; Wendem-Ageňehu, A.; Abebe, Y. (Eds.) Community Based Participatory Watershed Development: A Guideline; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005.

- Gebremedhin, B.; Pender, J.; Tesfay, G. Community Resource Management: The Case of Grazing Lands in Northern Ethiopia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on African Development Archives, Kalamazoo, Michigan, 16–18 August 2001. Paper 49. [Google Scholar]

- Mukai, S.; Billi, P.; Haregeweyn, N.; Hordofa, T. Long-Term Effectiveness of Indigenous and Introduced Soil and Water Conservation Measures in Soil Loss and Slope Gradient Reductions in the Semi-Arid Ethiopian Lowlands. Geoderma 2021, 382, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhussen, T. Conservation-Based Agricultural Development in Ethiopia, Paper Presented at the National Agricultural Policy Workshop; Ministry of Natural Resources Development and Environmental Protection: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1995.

- Roe, D.; Nelson, F.; Sandbrook, C. (Eds.) Community Management of Natural Resources in Africa: Impacts, Experiences and Future Directions, Natural Resource Issues No. 18; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin, B.; Pender, J.; Tesfay, G. Community Natural Resource Management: The Case of Woodlots in Northern Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2003, 8, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, A.; Poesen, J.; Haile, M.; Deckers, J.; Nyssen, J. Quantifying Long-term Changes in Gully Networks and Volumes in Dryland Environments: The Case of Northern Ethiopia. Geomorphology 2013, 201, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Descheemaeker, K.; Haregeweyn, N.; Haile, M.; Moeyersons, J.; Frankl, A.; Govers, G.; Munro, N.; Deckers, J. Effects of region-wide soil and water conservation in semi-arid areas: The case of northern Ethiopia. Zeitschrift für Geomorphol. 2008, 52, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Clymans, W.; Descheemaeker, K.; Poesen, J.; Vandecasteele, I.; Vanmaercke, M.; Zenebe, A.; Van Camp, M.; Haile, M.; Haregeweyn, N.; et al. Impact of Soil and Water Conservation Measures on Catchment Hydrological Response—A Case in North Ethiopia. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deressa, T.; Hassan, R.M.; Ringler, C. Measuring Ethiopian Farmers’ Vulnerability to Climate Change across Regional States; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mukai, S. Gully Erosion Rates and Analysis of Determining Factors: A Case Study from the Semi-Arid Main Ethiopian Rift Valley. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 28, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, S. Structure, Stratification, and Consensus-Building Process in Ethiopian Village. J. Afr. Stud. 2023. accepted (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, S. Assessing Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Campaign-Based Watershed Management: Experiences from Boset District, Ethiopia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girmay, T. Agriculture, Resource Management and Institutions: A Socio-Economic Analysis of Households in Tigray, Ethiopia. PhD. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, A.; Mariam, D.H. The Iddir in Ethiopia: Historical Development, Social Function, and Potential Role in HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control. Northeast Afr. Stud. 2000, 7, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aredo, D. The Iddir: An Informal Insurance Arrangement in Ethiopia. Sav. Dev. 2010, 34, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Exchange rates UK (2023) Ethiopian Birr to US Dollar Spot Exchange Rates for 2013. Available online: https://www.exchangerates.org.uk/ETB-USD-spot-exchange-rates-history-2013.html#:~:text=This%20is%20the%20Ethiopian%20Birr,USD%20on%2029%20Dec%202013 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Shimeles, O.; Jirra, C.H.; Girma, Y. Indigenous Community Insurance as an Alternative Health Care Financing. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2009, 19, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye, S.M. The Role of Civil Society Organizations in Poverty Alleviation, Sustainable Development, and Change: The Cases of Iddirs in Addis Ababa, Akaki, and Nazreth. Master’s Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abegaz, K. The Role of Iddir in Development for City Slum and Frontier Subcities of Addis Ababa: The Case of ACORD Intervention Areas. Master’s Thesis, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dercon, S.; Bold, T.; Weerdt, J.D.; Pankhurst, A. Extending Insurance? Funeral Associations in Ethiopia and Tanzania; OECD Development Centre: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, A. (Ed.) Iddirs: Participation and Development; ACORD Ethiopia: Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi, M. Community-Based Rural Development and the Politics of Redistribution: The Experience of the Gurage Road Construction Organization in Ethiopia. Nilo-Ethiop. Stud. 2008, 12, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Cooperation in Research and Development (ACORD) The Role of Indigenous Organizations in Development; Paper presented at the workshop organized by ESSWA; ACORD: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1998.

- Aredo, D. Iddir: A Look at A Form of Social Capital; ACORD: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Rajkumar, A.S. Achieving Better Service Delivery through Decentralization in Ethiopia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Emmenegger, R.; Keno, S.; Hagmann, T. Decentralization to the Household: Expansion and Limits of State Power in Rural Oromiya. J. East. Afr. 2011, 5, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benin, S.; Pender, J. Collective Action in Community Management of Grazing Lands: The Case of the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förch, W. Community Resilience in Drylands and Implications for Local Development in Tigray, Ethiopia. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fithanegest, G.; Gentilini, U.; Sonali, W.; Arega, Y. Engaging in a Multi-Actor Platform: WFP’s Experience with the Productive Safety Net Programme in Ethiopia. In Revolution: From Food Aid to Food Assistance: Innovations in Overcoming Hunger; Omamo, S.W., Gentilini, U., Standström, S., Eds.; World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2010; pp. 329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Shiferaw, B.; Holden, S.T. Farm-Level Benefits to Investments for Mitigating Land Degradation: Empirical Evidence from Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2001, 6, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, B.; Swinton, S.; Yibabe, T. Effects of Stone Terraces on Crop Yields and Farm Profitability: Results of On-Farm Research in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. J. Soil Water Conser. 1999, 54, 568–573. [Google Scholar]

- Vagen, T.G.; Yibabe, T.; Esser, K. Effects of Stone Terracing on Available Phosphorus and Yields on Highly Eroded Slopes in Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Sustain. Agric. 1999, 15, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, W. Stochastic Dominance Analysis of Soil and Water Conservation in Subsistence Crop Production in the Eastern Ethiopian Highlands: The Case of the Hunde-Lafto Area. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2005, 32, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, B. Informal Survey of Yeju Farming System; Working Paper No. 13; Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1995.

- Wood, A.P. Natural Resource Management and Rural Development in Ethiopia. In Ethiopia: Options for Rural Development; Lovise, S.A., Pausewang, T.K., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 1991; pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, B.; Asafu-Adjaye, J. Returns to Farm-Level Soil Conservation on Tropical Steep Slopes: The Case of the Eritrean Highlands. J. Agric. Econ. 1999, 50, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, B.; Holden, S.T. Soil Erosion and Smallholders’ Conservation Decisions in the Highlands of Ethiopia. World Dev. 1999, 27, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmato, D. Agrarian Reform in Ethiopia; Scandinavian Institute of African Studies: Uppsala, Sweden, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenafi, Z.T.; Leader-Williams, N. Indigenous Common Property Resource Management in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia, Hum. Ecol. 2005, 33, 539–563. [Google Scholar]

- Shibeshi, G.B.; Fuchs, H.; Mansberger, R. Formal and Informal Property Right Systems: The Case of the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. NJSR 2014, 10, 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yigremew, A. Access to Land in Rural Ethiopia: A Desk Review; A Study Report Submitted to Sustainable Land Use Forum: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yami, M.; Christian, V.; Hauser, M. Informal Institutions as Mechanisms to Address Challenges in Communal Grazing Land Management in Tigray, Ethiopia. Int. J. Sustain. 2011, 18, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, N. Maintaining a Fragile Balance: Community Management of Renewable Natural Resources in Tigray, NE Ethiopia. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASC), Bloomington, IN, USA, 31 May–4 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bewket, W.; Sterk, G. Farmers’ Participation in Soil and Water Conservation Activities in the Chemoga Watershed, Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2002, 13, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiningerl, K.; Ali, D.A.; Holden, S.; Zevenbergen, J. Rural Land Certification in Ethiopia: Process, Initial Impact, and Implications for Other African Countries; Policy Research Working Paper 4218; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mengesha, A.K.; Mansberger, R.; Damyanovic, D.; Agegnehu, S.K.; Stoeglehner, G. The Contribution of Land Registration and Certification Program to Implement SDGs: The Case of the Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Land 2023, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANRS-BoEPD. A Report on the Evaluation of the Five Years Agricultural Action Plan in Amhara National Regional State (ANRS); ANRS-BoEPD: Bahir Dar, Ethiopia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DryDEV Development Programme. Ethiopia-Drylands Development Programme: 2015 Annual Report; DryDEV: Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin, B.; Pender, J.; Tesfay, G. Collective Action for Grazing Land Management in Crop-Livestock Mixed Systems in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia. Agric. Syst. 2004, 82, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yami, M.; Mekuria, W.; Hauser, M. The Effectiveness of Village Bylaws in Sustainable Management of Community-Managed Exclosures in Northern Ethiopia. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yibabie, T. Enclosing or ‘Individualising’ the ‘Commons’? The Implementation of Two User-Rights Approaches to ‘Communal’ Areas Management in Post-Derg Northern Ethiopia. In Natural Resource Management in Ethiopia; Pankhurst, A., Ed.; Forum for Social Studies: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2001; pp. 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, A.P. Report of a Research Trip: South Wello and Oromiya Zones of Amhara Region, Ethiopia May 27–June 4, 2001; Institute for Development Research, Addis Ababa University: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Manaye, S.; Kassa, H. Usufruct Rights Certification and Tenure Security: The Case of Communal Forest Lands in Meket District of Northern Ethiopia. J. Agric. Dev. 2010, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Adenew, B.; Abdi, F. Land Registration in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Research Report 3; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, E. The Problem with the Locals: Partnership and Participation in Ethiopia. Dev. Chang. 2002, 33, 587–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, R.; Hirata, M.; Gebremedhin, B.G.; Uchida, S.; Sakai, T.; Koda, K.; Takenaka, K. Impact of Differences in Land Management on Natural Vegetation in Semi-Dry Areas: The Case Study of the Adi Zaboy Watershed in the Kilite Awlaelo District, Eastern Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Environments 2019, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniki, S.; Negusse, G. Communal Land Utilization in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia: Evidence of Transaction Costs. Jpn. J. Rural. Econ. 2015, 17, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haregeweyn, N.; Berhe, A.; Tsunekawa, A.; Tsubo, M.; Meshesha, D.T. Integrated Watershed Management as an Effective Approach to Curb Land Degradation: A Case Study of the Enabered Watershed in Northern Ethiopia. Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumasi, T.C.; Asenso-Okyere, K. Responding to Land Degradation in the Highlands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Segers, K.; Dessein, J.; Hagberg, S.; Develtere, P.; Haile, M.; Deckers, J. Be Like Bees—The Politics of Mobilizing Farmers for Development in Tigray. Ethiopia. Afr. Aff. 2008, 108, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, N.; Woldehanna, T. Managing Watersheds for Resilient Livelihoods in Ethiopia. Development Co-Operation Report 2012: Lessons in Linking Sustainability and Development; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.L. Who Shall Survive? Nervous Mental Disease Pub. Co.: New York, NY, USA; Washington, DC, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Billi, P.; Dramis, F. Geomorphological Investigation on Gully Erosion in the Rift Valley and the Northern Highlands of Ethiopia. Catena 2003, 50, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, T.; Shiferaw, B.; Menkir, A.; Wegary, D.; Kebede, Y.; Tesfaye, K.; Keno, T. Factors that Transformed Maize Productivity in Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, E.; Alfred, D.; Elize, L.M.; Abigail, M.; Admassu, H.; Arthur, M. International Centre for Development Oriented Research in Agriculture (ICRA). Livelihood and Drought Coping Strategies of Farm Households in the Central Rift Valley, Ethiopia: Challenges for Agricultural Research; ICRA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Meloun, M.; Militký, J. Statistical Data Analysis: A Practical Guide; Woodhead Publishing India: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS) Annual Report for the Project “Advanced-Technologies Development for Anti-Desertification and Environment Conservation in Ethiopia”; JIRCAS: Tsukuba, Japan, 2006. (In Japanese)

- FAO. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2006: A Framework for International Classification, Correlation and Communication; World Soil Resources Reports 103; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beyene, S. Introduction. In The Soils of Ethiopia; Beyene, S., Regassa, A., Mishra, B.B., Haile, M., Eds.; World Soils Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kassa, T.; Yemane, W. Evaluation of Land Suitability for Selected Tree Species in the Mesozoic Highlands of Ethiopia. MEJS 2017, 9, 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gool, D.; Tille, P.; Moore, G. Land Evaluation Standards for Land Resource Mapping: Assessing Land Qualities and Determining Land Capability in South-Western Australia; Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development: Perth, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fitsum, H.; Holden, S.T. Incentives for Conservation in Tigray, Ethiopia: Findings from a Household Survey; Centre for Land Tenure Studies Report; Norwegian University of Life Sciences: Ås, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremichael, D.; Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Deckers, J.; Haile, M.; Govers, G.; Moeyersons, J. Effectiveness of Stone Bunds in Controlling Soil Erosion on Cropland in the Tigray Highlands, Northern Ethiopia. Soil Use Manag. 2005, 21, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA) Ethiopia—Population & Housing Census 2007 Report. Oromiya. Part I. Population Size and Characteristics; CSA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010.

| Activities | Village Organization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | Iddir | PA + Iddir | User Group | Y/W Association 2 | Total | |

| Pond (drinking/daily life use) construction | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 0 | 7 (2) | 0 | 13 (7) |

| Pond (drinking/daily life use) maintenance | 1 (1) | 7 (4) | 1 (1) | 16 (4) | 0 | 25 (10) |

| Pond (animal use) maintenance | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Road repair (partially gully treatment) | 10 (8) | 2 (2) | 6 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 20 (14) |

| DTW (drinking/daily life use) construction 3 | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 12 (8) |

| DTW (drinking/daily life use) maintenance 3 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) | 4 (4) |

| Tebo River cleaning and maintenance 4 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| School reforestation | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 4 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) | 10 (7) |

| Church reforestation | 0 | 9 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (5) |

| Cropland SWC (soil/stone bunds) 5 | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Bare land and hillside SWC (bench terrace, etc.) 5 | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (6) |

| Bare land exclosure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Hillside management (exclosure/reforestation) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 9 (5) | 12 (8) |

| Grazing lands management | 7 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (7) |

| Gully treatment and maintenance | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | 0 | 0 | 9 (5) |

| Total | 37 | 30 | 24 | 28 | 15 | 134 |

| Variables | Definition | Descriptive Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 1 | S.D. | Min. | Max. | ||

| Dependent variable: | |||||

| Earthwork | Whether experienced collective earthwork since 1991? (dummy: no 0; yes 1) | 0.62 ns | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Independent variables: | |||||

| Distance | Distance from Welenchiti (km) | 8.90 * | 4.35 | 2.82 | 17.00 |

| Gotts | Hamlet (gott) numbers composing the iddir | 2.3 ** | 1.3 | 1 | 4 |

| IddirsNo | Iddir numbers in the village | 3.1 ** | 1.4 | 1 | 5 |

| Water | Number of communal water sources maintained by the iddir | 0.4 *** | 0.6 | 0 | 2 |

| Variables | Definition | The Means (S.D.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warka | Odalega | ||

| Dependent variable: | |||

| Non-compliance | The ratio of under-contribution to expected labor contribution | 0.72 (0.17) | 0.80 (0.21) |

| Independent variable: | |||

| Iddir | Iddir dummy: Warka 0, Odalega 1 | --- | --- |

| Age | Household (HH) head age | 0.76 (0.05) | 0.78 (0.07) |

| Gender | HH head gender dummy: male 0, female 1 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.5) |

| Education | Years of school education (the HH head) | 1.5 (2.3) | 0.3 (1.1) |

| Non-Agri | Total days in a week HH members working for non-agricultural jobs | 0.3 (1.1) | 0.2 (0.7) |

| Dependent | Dependency ratio (consumer units/producer units) | 3.5 (2.1) | 3.7 (2.5) |

| Female labor | Numbers of female HH members, ≦15 and < 55 | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.7) |

| Male labor | Numbers of male HH members, ≦15 and < 65), including regular agricultural labor | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.1) |

| Land | Cropland holdings (ha) 1 | 3.0 (2.4) | 2.2 (2.1) |

| Livestock | Tropical livestock unit of livestock owned | 3.4 (3.8) | 3.6 (6.9) |

| Cadre | Is the HH head an iddir cadre? (dummy: no 0, yes 1) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.05 (0.22) |

| No FFW (n = 13) | With FFW (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of seedlings planted per reforestation site | 5581 *** | 18467 *** |

| Number of seedlings per hillside area (ha−1) | 619 * | 813 * |

| Participants per reforestation site | 232 *** | 935 *** |

| Participants per hillside area (person ha−1) | 20 ns | 23 ns |

| Number of seedlings planted per participant | 44 *** | 101 *** |

| Working days per reforestation site | 9.1 ns | 8.5 ns |

| Age | Livestock Ownership 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Heads | Dependents | Household Heads | Dependents | |

| Youth association | 29.3 ± 4.6 (n = 98) | 22.5 ± 4.4 (n = 35) | 2.2 ± 1.8 (n = 98) | 5.5 ± 3.1 (n = 35) |

| Women’s association | 45.5 ± 12.0 (n = 16) | 34.3 ± 9.0 (n = 49) | 2.1 ± 2.7 (n = 16) | 5.0 ± 3.0 (n = 49) |

| Merko Odalega | No data | Mean = 2.9 (n = 352) 2 | ||

| Independent Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance | Gotts | IddirsNo | Water | |

| Canonical discriminant function coefficients | 0.159 ** | −0.543 ** | 0.683 ** | 2.358 *** |

| Standardized canonical discriminant function coefficients | 0.70 | −0.66 | 0.99 | 1.18 |

| Collective Maintenance Work | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fencing | Pond Cleaning | Pond Dredging | Canal Maintenance | Hiring Guards | |

| PAs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Iddirs | 8 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| User groups | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Villages | Number of Cases (% of the Total Cases in the Village) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | Iddir | PA + Iddir | User Group | Y/W Association | Total | |

| Senkel Kesel | 1 (4) | 2 (9) | 2 (9) | 12 (71) | 0 | 17 (100) |

| Koka Gifawasen | 3 (30) | 6 (60) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 | 10 (100) |

| Chemeri Jawis | 0 | 7 (29) | 17 (71) | 0 | 0 | 24 (100) |

| Merko Odalega | 6 (33) | 6 (33) | 0 | 0 | 6 (33) | 18 (100) |

| Bekakuto Nume | 4 (31) | 0 | 5 (38) | 0 | 4 (31) | 13 (100) |

| Buta Dalecha | 6 (26) | 4 (21) | 0 | 9 (47) | 1 (5) | 20 (100) |

| Buta Bedhaso | 5 (38) | 2 (15) | 0 | 5 (38) | 1 (8) | 13 (100) |

| Donkori | 6 (67) | 1 (11) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22) | 9 (100) |

| Buta Wegere | 6 (60) | 2 (20) | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 10 (100) |

| Factor | Eigenvalues | % of Variance | Structure Matrix | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | Iddir | User Group | Y/W Asso.2 | |||

| Factor 1 | 2.026 | 50.6 | 0.87 | −0.96 | 0.15 | 0.37 |

| Factor 2 | 1.335 | 33.4 | 0.36 | 0.15 | −0.91 | 0.74 |

| Items | Details |

|---|---|

| Total collective working days in a year (person-day) | (i) 0–5 days: 10 (59%), (ii) 5–10 days: 4 (18%), (iii) 10–15 days: 2 (12%), (iv) more than 20 days: 2 (12%) |

| Penalty for non-compliance households | (i) Force more work: 2 (12%), (ii) let pay them a fine: 13 [1 birr/day: 2 (12%), 5 birr/day: 7 (41%), 10 birr/day: 3 (18%), 20 birr/day: 1 (6%)], (iii) providing no church service: 1 (6%), (iv) no specific penalty: 1 (6%) |

| Number of exemption households | (i) 0–5 households: 11 (65%), (ii) 5–10 households: 5 (29%), (iii) more than 10 households: 1 (6%) |

| How cooperative are villagers? | (i) Very cooperative: 14 (82%), (ii) cooperative: 2 (12%), (iii) not so cooperative: 1 (6%) |

| Independent Variables | The Linear Least Squares | The Two-Limit Tobit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | t-Value | Coefficients | Z-Value | |

| Iddir | 0.0647 *** | 2.45 | 0.0980 *** | 3.15 |

| Age | 0.4076 ** | 2.46 | 0.5384 ** | 2.17 |

| Gender | 0.0374 | 1.37 | 0.0655 * | 1.87 |

| Education | 0.0087 | 1.13 | 0.0136 | 1.43 |

| Non-Agri | −0.0233 * | −2.05 | −0.0331 ** | −2.47 |

| Dependent | −0.0161 ** | −2.19 | −0.0182 ** | −2.03 |

| Female labor | 0.0114 | 0.50 | 0.0041 | 0.14 |

| Male labor | −0.0413 *** | −2.66 | −0.0592 *** | −3.31 |

| Land | −0.0110 * | −1.72 | −0.0152 ** | −1.99 |

| Livestock | 0.0022 | 1.21 | 0.0029 | 1.36 |

| Cadre | −0.1564 *** | −2.80 | −0.1711 *** | −2.78 |

| Factor | Eigenvalues | % of Variance | Structure Matrix (Variables) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Compliance | Iddir | Age | Gender | Education | Non-Agri | Dependent | Female Labor | Male Labor | Land | Livestock | Cadre | |||

| Factor 1 | 3.062 | 25.5 | −0.62 | −0.22 | 0.05 | −0.43 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.33 |

| Factor 2 | 1.806 | 15.0 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.31 | −0.61 | −0.39 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.35 | −0.36 |

| Factor 3 | 1.169 | 9.7 | 0.08 | −0.26 | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.08 | −0.34 | −0.40 | −0.17 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| Factor 4 | 1.067 | 8.9 | −0.00 | 0.71 | 0.16 | −0.20 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.14 | −0.30 | 0.03 | -0.24 | 0.05 | 0.58 |

| Scale of CPR Users 1 | CPRs | User Organizations | Remarks | Design Principles 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | ||||

| Boset (semi-arid Ethiopian Rift Valley) | |||||||||||

| A dozen to tens | Small ponds. Hillside management. Gully treatment and road repair | User group | User groups and Y/W associations usually do/did not have bylaws. Y/W association did not have clear membership rules. | A | B | B | B | B | A | A | C |

| Tens to about two hundred | Bare land exclosure and hillside management | Y/W associations 3 | B | B | B | C | B | C | C | C | |

| Over about two hundred | Large ponds, deep-tube wells, and river watering places. Gully treatment. Church and school reforestation. Small-scale infrastructure | Iddir (gott) | The regional government does not institutionalize governance activities (coordination, monitoring, conflict resolution, etc.) between district–village–hamlet. | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | C |

| Tigray (northern semi-arid Ethiopian Highlands) | |||||||||||

| A dozen to over about two hundred | Water sources. Exclosure forests. Grazing land management. Gully treatment. Small-scale infrastructure | Baito (qushet) | Governance activities are coordinated by the baito administration (district–village–hamlet), which is institutionalized. | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mukai, S. Collective Resource Management and Labor Quota Systems for Sustainable Natural Resource Management in Semi-Arid Ethiopia. Land 2023, 12, 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091702

Mukai S. Collective Resource Management and Labor Quota Systems for Sustainable Natural Resource Management in Semi-Arid Ethiopia. Land. 2023; 12(9):1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091702

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukai, Shiro. 2023. "Collective Resource Management and Labor Quota Systems for Sustainable Natural Resource Management in Semi-Arid Ethiopia" Land 12, no. 9: 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091702

APA StyleMukai, S. (2023). Collective Resource Management and Labor Quota Systems for Sustainable Natural Resource Management in Semi-Arid Ethiopia. Land, 12(9), 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091702