1. Introduction

Urban green spaces (UGS) or green infrastructure, such as greenways, parks, community gardens, living street trees, and nature preserves, offer a wide range of valuable ecosystem services [

1]. Their multiple benefits have led urban planning agendas worldwide to increasingly emphasize the importance of greening as a critical strategy for urban redevelopment, revitalization, and coping with global climate change and health challenges. However, despite UGS benefits, inequalities persist in distributing and accessing these resources, as evidenced by studies on urban environmental justice: high-income, highly educated, and white neighborhoods often have greater access to green space [

2,

3]. More recently, scholars have found that adding green space or other green amenities in previously non-existent communities can result in property value and rent increases that displace locals with newcomers who can afford the increased living expenses [

4]. This form of sociospatial outcome of urban greening is called “green gentrification” [

5,

6].

The concept of “gentrification” was coined by Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe the displacement of working-class individuals by the middle class and the associated transformations in the social character and physical landscape of inner London neighborhoods after World War II [

7]. After the 1980s, gentrification sparked intense academic debates regarding its explanatory theory. Scholars started to expand the concept of gentrification to encompass a much broader range of phenomena, including the upscale restructuring of urban economies, societies, and spaces, going beyond the initial focus solely on the housing market [

8,

9]. In the 1990s, with the onset of third-wave gentrification, large developers began to explore the “rent gap” within larger spatial contexts with the support of the state [

10]. This resulted in the redevelopment and repurposing of various urban areas, including urban peripheries, cultural heritage sites, commercial spaces, waterfront areas, landmark spaces, brownfields, and rural regions, to create residential and consumption spaces tailored to the needs of the middle-class [

11]. This process significantly broadened the analytical scope of the concept of gentrification, giving rise to subtypes and refined research frameworks, such as “new-built gentrification” [

12], “commercial gentrification” [

13], “jiaoyuficaiton” [

14], “tourism gentrification” [

15], and “rural gentrification” [

16].

Nonetheless, studies prior to 2000 predominantly focused on the social, economic, cultural, and spatial dimensions of gentrification, with limited attention given to the “natural” dimensions [

17,

18]. According to Gould, the ignoring of gentrification’s environmental dimensions can be attributed to the iterative and intertwined relationship between gentrification and greening processes, making it challenging to determine the causal direction (i.e., whether gentrification leads to greening or greening leads to gentrification) [

19]. However, in the 21st century, numerous cities in Europe and America have embarked on concrete “greening” initiatives involving large-scale adaptive reuse projects for sustainable development. Examples of such projects include New York’s High Line Park and Atlanta Beltline, which have generated intensive effects on local residential and commercial land use, spurring “super gentrification” [

20]. This confirmation of the independent and direct impact of greening events on gentrification also opened the door for the study of green gentrification.

Green gentrification has emerged as one of the most significant offshoots of classical gentrification theory in the 21st century. Over the past decades, an increasing number of scholars have combined traditional gentrification concepts with environmental and social theories, focusing their research on the role of “greening” as a driving force behind gentrification [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Green gentrification refers to the creation or intensification of urban socio-spatial inequities produced by urban greening agendas and interventions [

5,

19]. It occurs when greening actions such as brownfield cleanup, the installation of new, improved, or remediated urban green space, or the deployment of climate-adaptive green infrastructure take place [

20,

26]. These seemingly laudable municipal strategies may improve an area’s attractiveness while resulting in increased property values, housing prices, and physical and cultural displacement of residents who are unable to adapt to the increased costs of living to relocate—ultimately serving as a gentrifying [

27]. This paradoxical effect has also been identified with several similar terms in the literature, including “ecological gentrification” [

28], “environmental gentrification” [

27], and “eco gentrification” [

29]. Although they employ different terms, all these concepts focus on understanding the impact of greening actions and sustainability narratives on social–ecological urban environments [

30,

31,

32].

Green gentrification is a rapidly developing research field. Currently, research on green gentrification has expanded beyond its original North American context and has been documented in cities worldwide, such as Barcelona [

6], Seoul [

33], Medellín [

34], and Ghent [

35]. The focus of green gentrification analysis has also shifted from significant greening events, such as brownfield cleanup and large-scale green infrastructure, to more diverse forms of greening, including urban greenways, parks [

36], community gardens [

37], street trees [

38], urban agriculture [

39], organic food [

40], green buildings [

41], and eco-density [

42,

43]. As a result, a wealth of research topics and findings have emerged in this field in the past two decades [

19,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Although there have been several insightful reviews on green gentrification, they either focus on the trends and future research directions of the entire field or the methodological trends of green gentrification research [

30,

44,

45]. A less quantitative study has examined the progress made in this rapidly expanding field over the past few years. Therefore, it is necessary to use systematic bibliometric research and knowledge mapping to expand and complement existing work, which will help researchers and decision-makers review past studies and understand the research hotspots for future development.

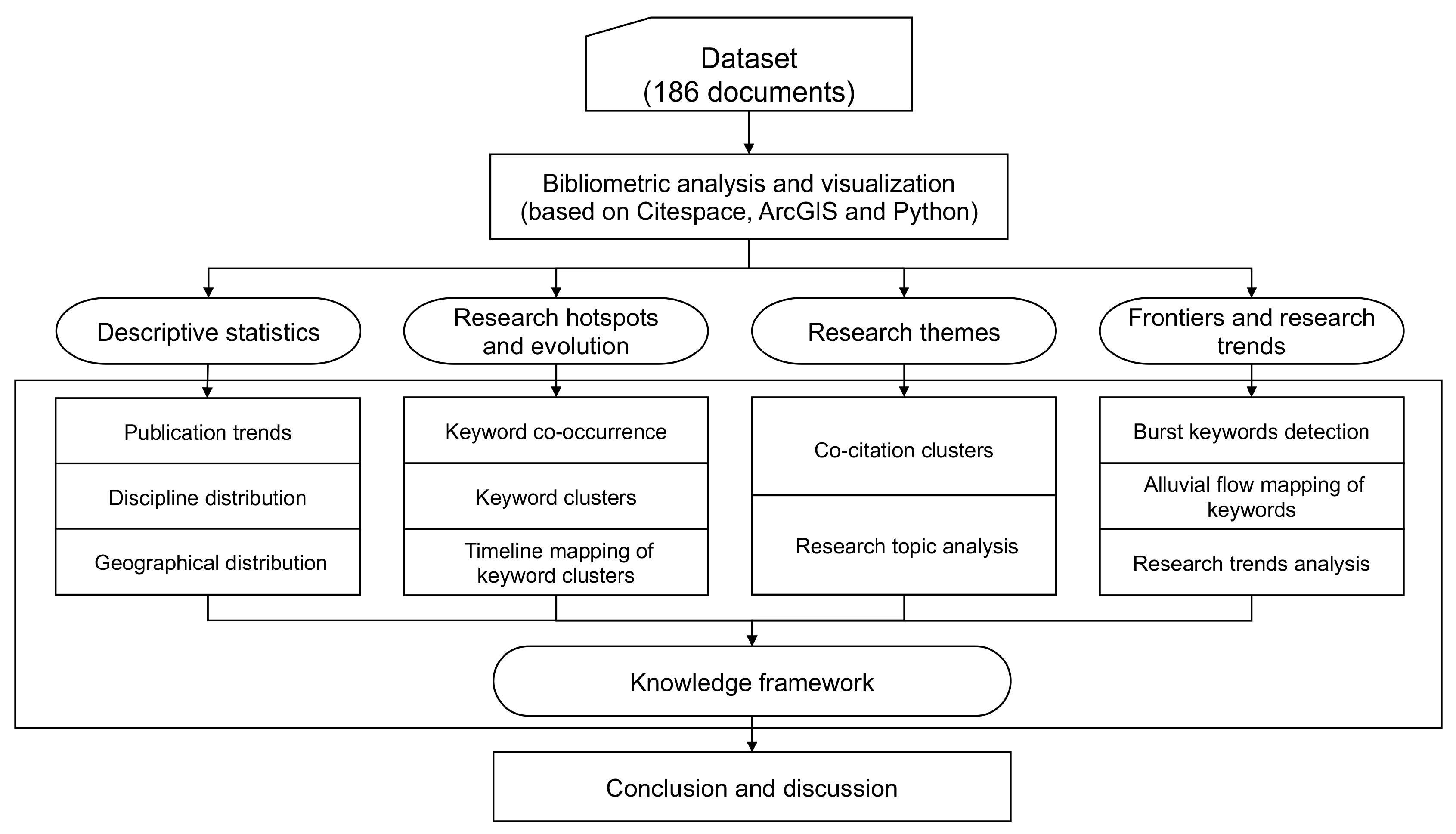

This study aims to provide a comprehensive knowledge base and systematic overview of research on green gentrification. To better comprehend the current state of research and potential future directions, we conducted quantitative analyses of green gentrification studies through bibliometric methods and visualization tools, assessed the fundamental characteristics, mapped knowledge structures to identify crucial topics in green gentrification research, and traced the research hotspots and their evolution process in recent years. Furthermore, we made scientific predictions on the future direction of the field. This study has four primary objectives: (1) to identify the publication trends and distribution of green gentrification studies, including information on countries, disciplines, and contributors involved in this research area; (2) to determine the research hotspots within this field and examine their evolution over time; (3) to provide an in-depth analysis of the main research topics within green gentrification studies; and (4) to detect current research frontiers and potential future research trends in the field of green gentrification.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

The publication trends, distribution of disciplines, and geographic focus in green gentrification research are described as follows.

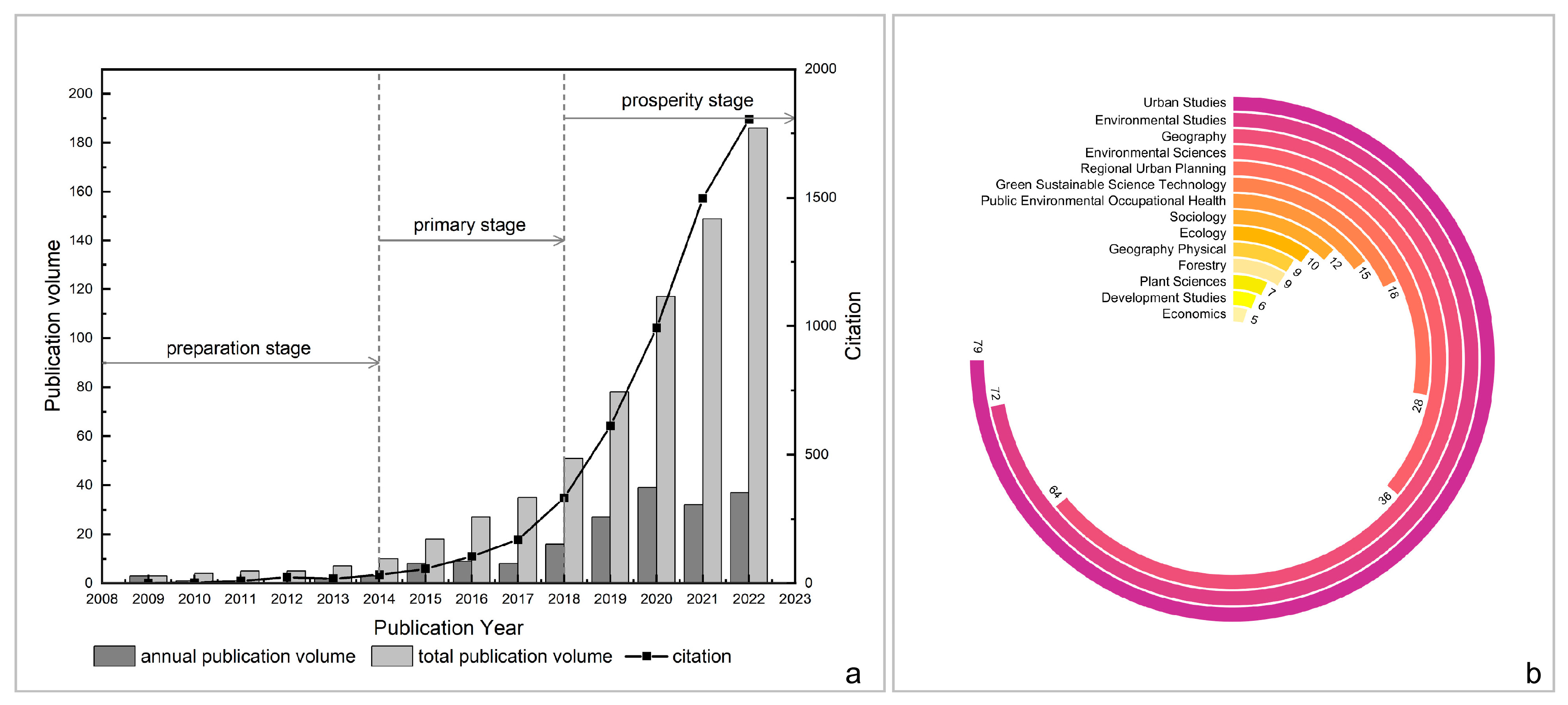

Figure 2a visually illustrates the growth of the green gentrification study area, plotting 186 publications and showing the distribution of articles published per year. The first paper on green gentrification was published in 2009 by Dooling [

28]. Since its inception, research on green gentrification has undergone various transformations, evolving in tandem with trends in urban greening and sustainable urban development. By examining the volume of the literature published in different years, the emergence of crucial keywords (

Figure A2 and

Figure A3), and international policy trends, the evolution of green gentrification research from 2009 to 2022 can be categorized into three distinct stages: preparation, primary, and prosperity.

Between 2009 and 2014, the literature on green gentrification experienced slow growth, with only ten articles published, representing a mere 0.63% of the total articles published in the past 13 years. With the onset of the 21st century, the concept of the “green turn” emerged as a crucial urban concern and a significant policy trend in the post-industrial era, garnering global attention. An intriguing phenomenon observed in North American cities was the conversion of vacant and derelict land (VDL) into urban greenspaces or green amenities, which triggered increasing interest among researchers [

5,

19]. Although these changes have contributed to the formation of the concept of green gentrification, this topic has not been deeply explored, signifying a preparation stage.

Between 2015 and 2018, the concept of green gentrification was established, accompanied by the development of its foundational theories, marking the entry into a primary stage of research. During this period, a total of 68 articles focused on green gentrification were published, accounting for 36.56% of the total articles. In 2015, the United Nations Development Summit adopted the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, which provided a comprehensive framework of goals for urban sustainable development, encompassing economic, social, and environmental aspects. This development sparked a growing interest among researchers in the social–spatial impacts of urban greening practices and led to the rapid development of green gentrification as a significant research topic.

From 2019 to 2022, research on green gentrification experienced explosive growth, with publications accounting for 58.06% of the total articles published. In 2019, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP25) encouraged the implementation of nature-based solutions (NbS), such as parks, lakes, rivers, green belts, and trees, to facilitate the ongoing transformation of cities toward climate adaptation, livability, and sustainable development. The pursuit of social and environmental justice in emerging urban greening practices and narratives has become a crucial focal point for interdisciplinary researchers, planners, and activists [

49]. Many researchers have started empirically exploring the concept of green gentrification in various contexts, leading to a deepening and diversification of research on green gentrification, entering a phase of prosperity.

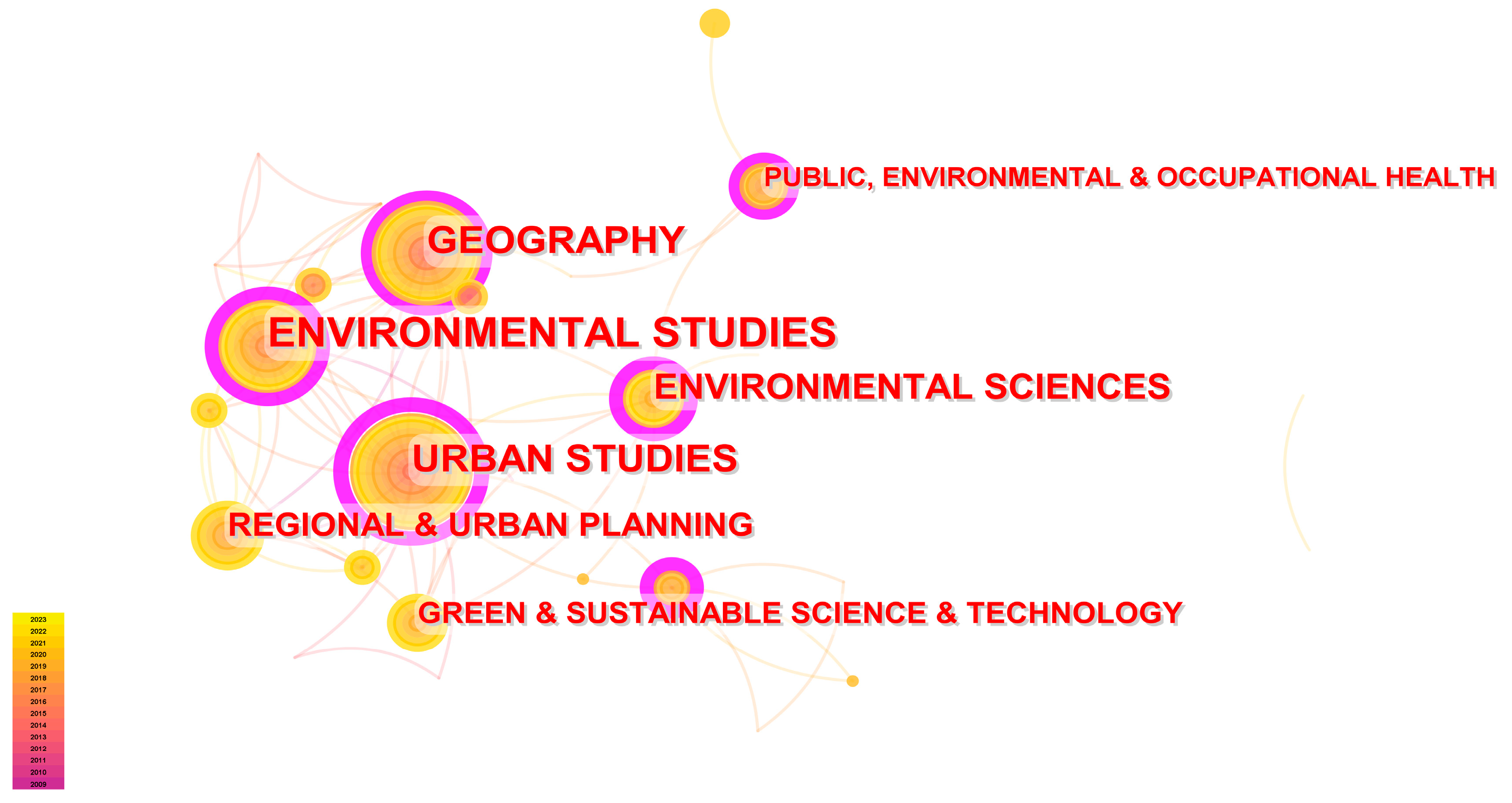

To investigate the scientific domain involved in green gentrification studies, we utilized Web of Science categories and found that the current research literature spans 26 different disciplines, as shown in

Figure 2b.

Figure 3 illustrates the field’s critical disciplines, including urban studies, environmental research, and geography. Although limited publications exist in areas such as sociology, environment and public health, and regional and urban planning, these publications have a high degree of intermediary centrality, serving as a bridge for the flow of knowledge among disciplines. Additionally, the green gentrification research field has extended to ecology and development studies.

Figure A4 illustrates the evolution of basic knowledge in green gentrification research, as shown by the dual-map overlays of journals from 2009 to 2022. Our analysis shows that the development of green gentrification research is sustained by specialized knowledge, mainly in economic and political science and ecology. The trend of crossover and integration of multidisciplinary knowledge is also constantly strengthening.

Figure 4 presents the findings regarding publication countries and the cities where study cases were conducted. Before 2014, all the studies focused on North America. Subsequently, publications highlighting green gentrification in Asia and Europe emerged, albeit in limited numbers. In 2018, the concept gained further popularity, with North America maintaining its dominant position while research in Europe and Asia continued to grow. Additionally, South America, Eurasia, and Australia witnessed the emergence of green gentrification research, indicating a global interest in the phenomenon.

In terms of geographical distribution, North America and Europe are the primary centers of research in the field. The United States leads with 40.3% of the 186 articles in our dataset, which aligns with the country’s long history of environmental justice research. Case studies primarily focus on major cities such as New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Portland, which are known for their sustainability efforts. Spain and the United Kingdom have also made significant contributions, accounting for 13.8% and 5.97% of the total publications, respectively. Barcelona stands out as the most studied city in Europe due to the presence of active research groups focusing on urban green justice. We observed 12 publications from Asian countries, including research conducted in postsocialist nations such as Estonia and Romania. Research on green gentrification in South America, Australia, and Eurasia remains relatively limited, reflecting the ongoing controversy surrounding the concept’s applicability to gentrification in the Global South, particularly within a neoliberal context. Indeed, the suitability of the gentrification framework as a useful lens for analyzing urban restructuring processes outside the Global North has long been a subject of debate among urban researchers [

50,

51,

52]. Recent comparative gentrification studies have emphasized the importance of decentering the production of knowledge as well as encouraging the inclusion of analyses that account for the unique local contexts and backgrounds to understand how gentrification interacts with other processes and discourses that are available in specific localities [

53]. Instead of imposing Euro-centric understandings of gentrification on the Global South, there is a growing recognition of the need to learn from the emergence of “new sharp-edged forms” of gentrification in previously peripheral cities of the Global South [

54,

55].

3.2. Research Hotspots and Evolution Process

Keyword co-occurrence analysis serves as a valuable tool for identifying research hotspots and mapping the research trajectory. By analyzing the frequency, centrality, collaboration, and connections within the dataset, we gain insights into the research on green gentrification.

Figure 5 shows the frequency of keyword occurrences, with 13 keywords appearing at least 15 times in green gentrification research. The top ten co-occurring keywords, ranked in descending order, are city (74), environmental gentrification (55), environmental justice (48), green gentrification (40), gentrification (35), green space (35), health (26), politics (22), ecosystem services (18), and political ecology (17). Notably, although climate change (11), displacement (11), and community (15) do not rank in the top 10, they still hold significant influence and play crucial roles in related studies. Strong correlations and close connections exist among most keywords, highlighting the interrelation of green gentrification with environmental justice, gentrification, and political ecology. Existing research emphasizes the conceptualization and implementation of green gentrification, explicitly focusing on urban green spaces. Additionally, attention is given to aspects such as displacement, neighborhood change, and health impacts.

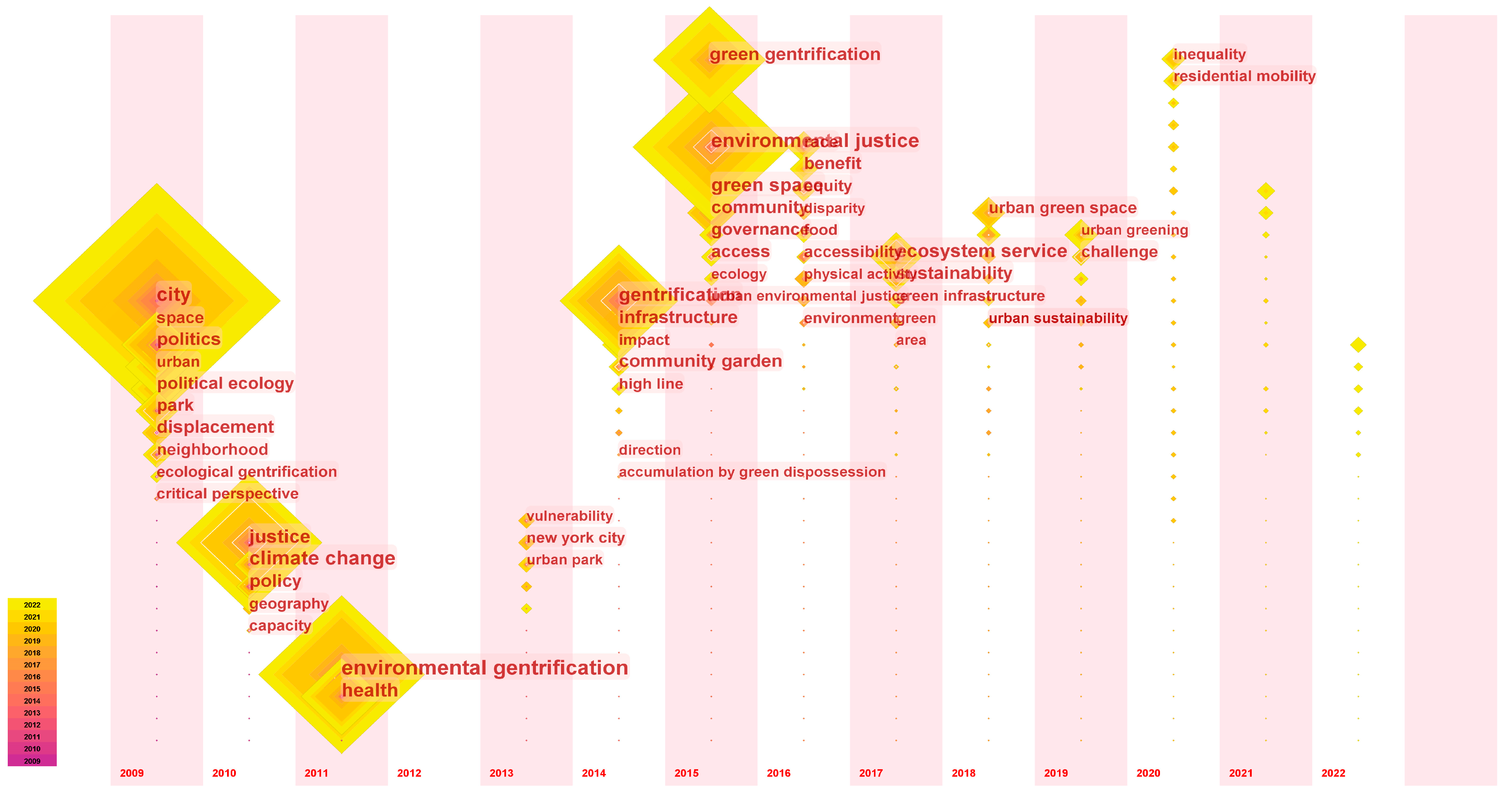

Moreover, we analyze the keywords’ time evolution to identify research hotspots, trace their development trajectories, and detect emerging frontiers.

Figure 6 depicts the timeline of co-occurring keywords in green gentrification research, highlighting the ten clusters identified through the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) algorithm, with most clusters showing a strong interdisciplinary connection. The hotspots in green gentrification-related research can be categorized into three dimensions: theoretical framework (#1 environmental justice, #3 political ecologies, #4 urban sustainability, #8 urban planning), concept implementation (#0 green infrastructure, #2 urban agriculture, #7 urban parks, #5 high line), and performance and effects (#6 social vulnerability, #9 accessibility).

The initial stage, which began in approximately 2009, focused on spatial inequality and displacement, as evident from the keyword nodes. Subsequently, in 2014, keywords related to green gentrification emerged, indicating a shift toward conceptual framework and design implementation. Notable case studies, such as the High Line in New York, reflected a growing interest in practical applications. The period from 2008 to 2014 represented the peak period of high-frequency keywords, with an intensified connection between environmental justice and gentrification keywords, signifying convergence between these fields. As the field progressed, the density of keyword nodes increased, encompassing governance, policy, and health-related aspects. This diversification expanded the field’s scope to examine the broader implications of green gentrification.

In 2018, the emergence of keywords such as accumulation, driving force, and cultural ecosystem services indicated a focus on underlying mechanisms and impacts. From 2018 to 2022, research delved into lifestyle, residential preferences, relocation motives, and consumption concepts as new entry points for green gentrification. Additionally, keywords such as “green stormwater infrastructure” (GSI), “green resilient infrastructure” (GRI), and “NBS” signaled a shift toward more sustainable and climate-friendly forms of greening, expanding the concept of green gentrification beyond traditional vegetation greening. In 2022, keywords such as “concentrated poverty”, “urban renewal”, “community response”, and “adaptive planning” emerged, showcasing a growing interest in the social–spatial effects, critical research, and optimization strategies of green gentrification.

3.3. Critical Themes for Green Gentrification

The comprehensive research analysis on the foundations of green gentrification and the keyword co-occurrence clustering map (refer to

Figure A5) were combined, resulting in 186 articles subjected to a full-text review. We identified five distinct categories of research themes (

Figure 7); a detailed review of 351 references was also conducted for each theme to provide a more comprehensive description.

3.3.1. Conceptualizing Green Gentrification

Clusters #0 and #8, with earlier start times and longer durations, encompass the seminal literature that introduced the terms “green gentrification” and “environmental gentrification” [

5,

27]. These clusters primarily focus on conceptualizing the social–spatial restructuring phenomenon triggered by urban greening and provide a foundation for subsequent research. However, scholars from urban political ecology, urban geography, and urban planning have different perspectives and emphases in defining and interpreting this phenomenon, resulting in the emergence of closely related terms such as ecological gentrification, environmental gentrification, green gentrification, green climate gentrification, and low-carbon gentrification.

For example, the term “ecological gentrification” was coined in the field of urban political ecology in 2009, emphasizing the role of elite environmental awareness and discourse in shaping the unequal distribution of ecological project benefits and viewing gentrification as a consequence of procedural injustice under the concept of “ecological rationality” [

28]. This perspective has extended to spatial transformations closely related to sustainable urban development, leading to terms such as “low-carbon gentrification” [

56] and “climate gentrification” [

57]. On the other hand, the term “environmental gentrification” emerged as environmental justice and shifted its focus from avoiding proximity to hazardous facilities to seeking comfortable environmental amenities. It examines the unintended consequences and hidden costs of environmental justice actions and sustainable policies [

27]. This concept primarily encompasses environmental remediation and restoration projects such as brownfield redevelopment, waterfront redevelopment, abandoned railway conversions, and vacant and derelict land redevelopment, as well as a limited number of environmental amenities such as new parks and greenways. The term “green gentrification” originated from intersectional research on environmental justice and sustainable development [

5], highlighting the social–spatial consequences of vegetation greening, such as parks, greenways, or green infrastructure. It emphasizes the underlying capital, power dynamics, and deprivation inherent in green production under neoliberal development. Over time, this concept has been applied to green buildings, urban agriculture, organic food consumption, and clean energy initiatives, among others.

Figure 8 provides an overview of these relevant terms’ connotations and evolution processes.

3.3.2. Operationalizing Green Gentrification for Local Applicability

Following the emergence of the concept of green gentrification, scholars shifted their focus to examining the locality of this phenomenon and characterizing it (cluster #10). Most researchers employed qualitative approaches, conducting local-level analyses of individual green spaces, particularly emphasizing landmark greenspaces [

58]. To capture the phenomenon of green gentrification, participatory observation [

59], interviews [

60,

61], and questionnaire investigations [

62] were frequently adopted, alongside the analysis of materials such as news media [

63,

64], planning documents [

65], policies, and archives [

66]. These studies aimed to understand different participants’ experiences in the green gentrification process and their post-gentrification perceptions, enabling a comprehensive understanding of this multifaceted phenomenon within specific areas and its impacts on surrounding neighborhoods.

Since 2017, there has been an increase in the use of quantitative approaches to identify green gentrification.

Figure 9 illustrates that most of these studies have focused on analyzing the relationships between socioeconomic and demographic factors and greening interventions represented by distance or buffer areas. Typically, these studies adopt a global-level analysis, encompassing multiple cities or all units of a single city, such as census tracts or blocks. Researchers widely employ spatial econometric methods, such as exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) [

67] and geographically weighted regression (GWR) [

6], as well as time series approaches that explore changes in indicators over time [

6,

21,

37], including the differences-in-differences (DID) approach [

68] and canonical correlation analysis (CCA) [

69], which have been extensively utilized. The quantitative analysis primarily aims to identify the spatial and temporal patterns of green gentrification at a macro scale, advancing our understanding of this phenomenon.

3.3.3. Social–Spatial Effects of Green Gentrification

The literature in clusters #3 and #7 extensively explores the social–spatial impacts of green gentrification, particularly the associated social vulnerabilities and inequalities [

70,

71,

72]. Previous research has identified four key dimensions of social implications resulting from green gentrification dimensions [

30]: capital reinvestment, social upgrading, displacement, and landscape change.

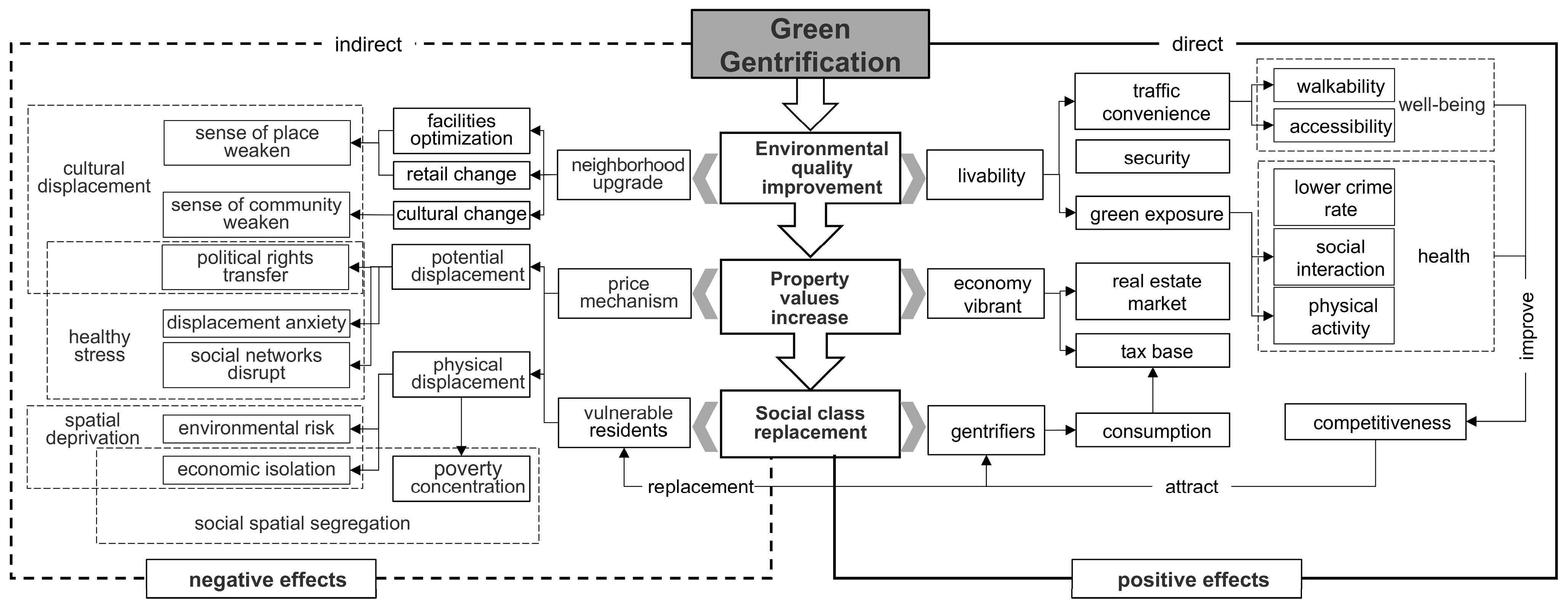

As illustrated in

Figure 10, the escalation of real estate values stands out as the predominant consequence of green gentrification [

68]. Urban greening initiatives significantly enhance environmental comfort and rejuvenate dilapidated areas in older urban regions, low-income neighborhoods, and former industrial zones, thereby giving rise to the phenomenon known as the “rent gap” [

37,

43]. Social upgrading is a well-studied outcome, with research investigating changes in sociodemographic indicators following greening initiatives, such as race, household composition, income, and education [

6,

25]. The findings indicate that social upgrading associated with green gentrification primarily benefits white populations [

73], affluent individuals [

74], and highly educated groups. Conversely, there is a decrease in low-income residents and tenants of informal housing [

57,

75].

Several studies focus on specific social vulnerabilities within certain areas, such as the growing number of nonagricultural workers [

69] and the influx of immigrants from northern countries, as well as the declining population of elderly individuals living alone [

6]. Displacement is considered a central aspect of social injustice in green gentrification. Researchers investigate both the physical factors that contribute to the risk of displacement, such as escalating housing costs and living expenses [

76,

77], and the psychological effects of displacement resulting from social and structural changes, including social exclusion, marginalization, stigmatization, and weakened community bonds [

78,

79]. Landscape changes are less-explored effects, often centered around urban facilities reflecting the consumption preferences of the upper class, such as sustainable transportation, bicycle lanes, LEED-certified buildings, high-end residences, cafes, boutique shops, and organic supermarkets [

36,

77,

80,

81,

82].

3.3.4. Exploring Explanatory Frameworks or Models for Green Gentrification

Cluster #5 and cluster #6 encompass a significant body of literature during a prosperous research period in green gentrification. This literature includes classic works on gentrification theory, such as Smith’s rent gap theory and Ley’s consumption theory, and explanatory frameworks from critical sustainability studies and urban planning, such as growth machines and settler colonialism theory.

The majority of studies view green gentrification as supply-side-led, employing the “green rent” framework to explain how investors (government/developers) utilize greening strategies to create a “rent gap” between potential and realized rents through community reinvestment [

6,

22,

37,

43]. Conversely, a minority of studies explore demand-side-led green gentrification [

37]. This perspective of explanation posits that the affinity and demand for greening among middle-class and upper-class newcomers, along with their political power advantages, facilitate greening processes in communities [

38,

39]. The creation of new green spaces to cater to the initiatives and demands of the middle class also leads to the presence of recognitional and interactional injustices, further exacerbating cultural displacement [

18,

40].

Urban planning theory has been introduced by other scholars, who have developed the “green growth machine” framework to explain how the creation of greenspaces, aimed at promoting growth, operates within the “growth coalition” while excluding vulnerable groups from benefiting from such spaces [

20,

36,

66,

83]. For instance, the “creative class theory” has been utilized to elucidate how cities use greening initiatives to attract the new middle class, composed of creative and technological professionals, potentially leading to social upgrading [

84].

Based on critical sustainable cities theory, some researchers have developed the “urban sustainability fix” concept to explain how greening objectives are integrated into urban planning to promote capital accumulation [

59,

72,

84,

85].

In addition, the concept of the “environmental bourgeoisie” has been introduced by scholars, revealing how the affluent class appropriates ecological improvements to justify gentrification [

86]. Other applied theories include “settler colonial theory” [

82,

87], “queer theory” [

28,

58], and “stigma theory” [

78], highlighting the role of asymmetric power structures in shaping the detrimental consequences of green gentrification.

3.3.5. Strategic Response to Green Gentrification

Cluster #4 comprises the early published literature, primarily consisting of classic works on environmental justice action strategies [

27,

63,

72]. The focus lies on community-led activism against green gentrification, proposing diverse strategies to mitigate its adverse effects and foster socially just green development. These strategies encompass environmental policies and regulations, collective neighborhood actions, and community organizations.

One prominent strategy is the “just green enough” approach, which advocates for a dialog mechanism between long-time residents and gentrifiers, emphasizing democratic negotiation over top-down green space planning processes. Additionally, it promotes the development of green spaces in informal areas such as vacant land, riverbanks, and rooftops or walls, which are less susceptible to gentrification [

63,

88]. Scholars, from an urban planning perspective, focus on enhancing social equity outcomes by configuring and designing small-scale, dispersed green spaces that prioritize accessibility and quality rather than solely focusing on increasing per capita greenspace [

89].

Researchers have also proposed the “community empowerment” strategy, involving grassroots social organizations, nonprofit groups, environmental volunteers, and other entities in greenspace planning, construction, and maintenance processes. This strategy promotes participatory planning centered on communication and dialog [

90,

91]. Furthermore, scholars have suggested additional policy measures, including the development of housing trust funds, provision of affordable housing, rent control, and housing market stabilization [

89]. They also highlight the importance of implementing cooperative management approaches and creating job opportunities for vulnerable groups [

92].

3.4. Advancements and Emerging Directions in Research

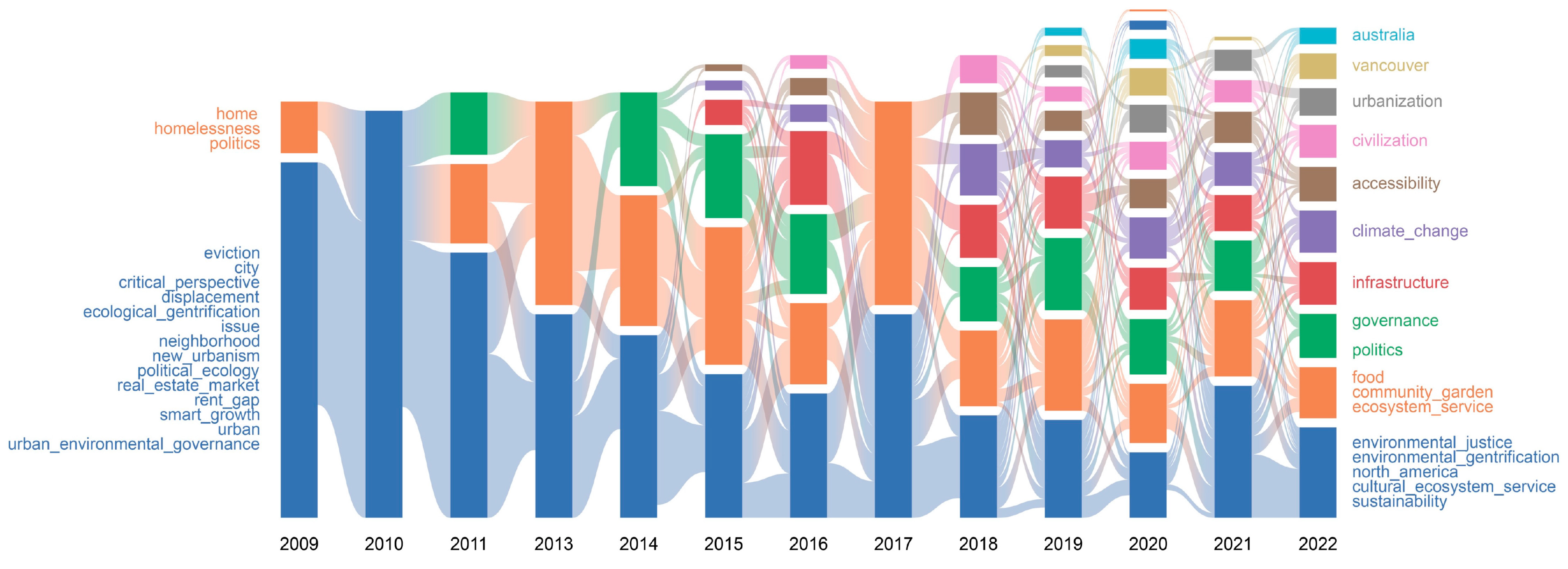

The alluvial diagram, a visualization technique displaying the flow of items such as keywords, publishing journals, and country origins in bibliometrics over time, reveals the evolution of research on green gentrification. The diagram (

Figure 11) shows that from 2009 to 2013, research focused on “displacement”, “justice”, and “politics”, emphasizing the fundamental values of justice and equity in this field. Since 2015, “health” and “vulnerability” have become more frequent, while “impact” remains significant, indicating the growing relevance of the unexpected outcomes of urban greening. In addition, the field has entered an empirical accumulation phase, as reflected in the high frequency of terms such as “infrastructure”, “community garden”, and “ecosystem service”.

Between 2015 and 2018, scholars began to explore the mechanisms of green gentrification from multiple theoretical perspectives, and in 2019 and beyond, research topics in this field became increasingly diverse. The adoption of spatial analysis methods and new theoretical perspectives such as “political ecology”, “growth machine”, and “sustainability fix” gained popularity. Attention to new topics such as “natural outdoor environments”, “urban agriculture”, and “resilient infrastructure” suggests that the applicability of the concept of green gentrification is still expanding (

Figure A5).

Based on previous fundamental research and hotspot evolution analysis, several current research hotspots and frontiers in the field of green gentrification have been identified: (1) Broadening the scope of non-North American case studies: While most research on green gentrification focuses on North American cities, there is growing interest in investigating this phenomenon in non-Western contexts, particularly in cities of the Global South. Examining green gentrification dynamics in diverse social, economic, cultural, political, and environmental contexts will provide a more nuanced understanding and expand the theoretical framework of green gentrification. (2) Advancing interdisciplinary theoretical innovation: The growth of research related to green gentrification has enabled the formation of an interdisciplinary foundation. Future studies will benefit from a cross-disciplinary approach, integrating theories and methods from urban geography, ecological politics, and urban planning. This interdisciplinary trend will lead to innovative theoretical frameworks and a comprehensive understanding of green gentrification’s complex nature. (3) Expanding the analysis of green gentrification characteristics: Research on green gentrification is still rapidly expanding. Future studies will innovate empirical methods to explore green gentrification’s conditions, characteristics, and spatial-temporal dynamics. This includes analyzing the association between different types of greenery and gentrification and incorporating temporal and spatial dimensions into research analysis. (4) Exploring demand-side drivers of green gentrification: While current research primarily focuses on supply-side driven processes of green gentrification, there is a need to explore the mechanisms from the demand-side perspective, particularly when gentrification occurs prior to greening interventions. As highlighted by Baviskar, “upper-class concerns around aesthetics, leisure, safety, and health have come significantly to shape the disposition of urban spaces” [

34]. Therefore, future research should delve deeper into analyzing how the middle-class demand for green spaces shapes green gentrification from the perspective of lifestyles, values, and consumption patterns, as well as investigate how gentrifiers utilize their wealth and political influence to further promote the process of green gentrification. Additionally, it is essential to integrate perspectives on everyday practices, place attachment, and sense of place to understand the micro-processes of this phenomenon and its specific impacts on urban residents to elucidate how green gentrification contributes to displacement. By addressing these research frontiers, scholars can advance our understanding of green gentrification and its implications, contributing to more comprehensive and informed urban sustainability planning and policy development.

4. Discussion

The preceding chapters have described the key characteristics, hot topics, themes, frontiers, and future trends in green gentrification research over the past 15 years. Our research findings strongly support the early insights of several review studies regarding scholarly pathways on green gentrification [

44], the framework and key dimensions of green gentrification [

45], and the methodological trends in green gentrification research [

30]. Moreover, our research has contributed to advancing knowledge in this field by uncovering new discoveries and insights. Through our work, we have identified the existing gaps in green gentrification research, which will guide future investigations and help shape the direction of further inquiry.

Based on our review, urban studies, environmental research, and geography are the key disciplines shaping the advancement of green gentrification research, which aligns with the initial domains highlighted by Anguelovski et al. [

44]. Moreover, our results further reveal that the main sources of professional knowledge supporting green gentrification research stem from the fields of economic and political science and ecology. Additionally, we have identified the characteristics of interdisciplinary integration and knowledge crossing that emerge during the process of green gentrification. Second, consistent with the findings of Pearsall et al. [

75], our study also reveals that the majority of research on green gentrification is centered around cities in the United States and Western Europe. However, our analysis goes a step further and identifies a growing trend of green gentrification spreading from the Global North to the South. Importantly, existing research predominantly focuses on developed capitalist countries, thereby lacking sufficient discussions on cities with diverse political-economic backgrounds (such as post-colonialism, post-socialism, and socialist transformation) and different stages of development (including growth, contraction, and urban recovery). Third, our analysis reveals that current research on green gentrification is predominantly based on case studies, which aligns with the findings of Cucca et al. [

31]. However, our study further highlights that the current case studies primarily concentrate on individual cases, while comparative research across multiple cities and regions is relatively scarce. Fourth, our analysis has also advanced Quinton’s work on the methodology of green gentrification [

30]. In addition to identifying the shift in research methods from early qualitative to quantitative, we also contend that although current case studies predominantly employ quantitative analytical frameworks to assess the magnitude and range of the phenomenon, future research should integrate qualitative methods to comprehensively investigate changes in community culture, political environments, and other intricate aspects. Fifth, in line with the perspectives of Sax and Quinton [

30,

45], our analysis concurs that the mechanisms through which greening leads to gentrification are poorly understood, particularly on the demand side. Considering these limitations, future research on green gentrification should expand to include noncapitalist cities, adopt an interdisciplinary approach, focus on comparative studies, incorporate qualitative research methods, explore demand-side mechanisms, and examine the effects of green gentrification on local communities.

Additionally, compared to previous review studies [

30,

31,

45,

75], this research adopts an innovative approach by integrating quantitative and qualitative analysis, providing a comprehensive examination of the entire history of green gentrification research, as well as constructing a thorough and visualized knowledge body of green gentrification. First, the quantitative analysis in this study visualizes the temporal and spatial variations in green gentrification research, enabling researchers to comprehend the historical progression and geographical diffusion of green gentrification. Second, through quantitative analysis, this study traces changes in research orientations and hotspots, facilitating an understanding of the evolving trends within green gentrification research. Third, the study identifies the thematic distribution of green gentrification research and provides a detailed analysis of the themes, enhancing the understanding of the existing knowledge on green gentrification. The most significant outcome of this research is its ability to identify development trends accurately and scientifically, as well as forecast future research directions, by employing both quantitative and qualitative analysis. Consequently, it provides valuable insights for researchers to determine future research directions.

Although this study provides a basic understanding and appreciation of green gentrification research, it has limitations. The study only utilized data from the Web of Science (WOS) database, which excluded publications in languages other than English. However, research in this area has undoubtedly been carried out in non-English-speaking regions, and excluding such studies limits the scope and generalizability of this analysis. Therefore, future research should expand the scope of multilingual paper searches to include a broader range of studies, which will better summarize and examine current hot topics and research trends related to green gentrification. Such efforts will further our understanding of this complex and nuanced phenomenon and provide a complete reference for scholars engaged in related research.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically reviewed the literature relevant to green gentrification, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of the development and limitations of green gentrification studies and offer theoretical foundations and methodological suggestions for future research in this field. This paper employs a CiteSpace-based bibliometric approach analysis to analyze 186 articles quantitatively and qualitatively from the Web of Science database from 2009 to 2022. The following conclusions are drawn:

A general bibliometric analysis reveals that research in this field has exhibited three major stages: the preparation stage (2009–2014), the primary stage (2015–2018), and the prosperity stage (after 2019). The development of mainstream knowledge on green gentrification has primarily originated from the fields of urban studies, environmental research, and geography. Furthermore, the knowledge base of green gentrification research has expanded over time, indicating a trend toward multidisciplinary integration. The leading research-producing locations are North America and Europe, and studies from South America, Asia, and Australia are increasing in number.

In the knowledge mapping analysis, we significantly identified three research hotspots: the theoretical framework, concept implementation, and character and effects. The latest research hotspots are progressively focusing on the social–spatial effects, mechanisms, and optimization strategies of green gentrification.

In light of the results of both knowledge mapping and qualitative analyses, five key research themes were summarized: conceptualizing green gentrification; operationalizing green gentrification for local applicability; social–spatial effects; exploring explanatory frameworks or models; strategic response to green gentrification; the social–spatial effects of green gentrification; theories and explanation framework of green gentrification; and the responses to green gentrification. Moreover, three current trends were identified, which include quantitative empirical analysis, social–spatial effects, and explanatory frameworks. We predict that future research will focus on the following aspects: broadening the scope of non-North American case studies, advancing interdisciplinary theoretical innovation, expanding the analysis of green gentrification characteristics, and exploring demand-side drivers of green gentrification.