Study on the Impact of Social Capital on Agricultural Land Transfer Decision: Based on 1017 Questionnaires in Hubei Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

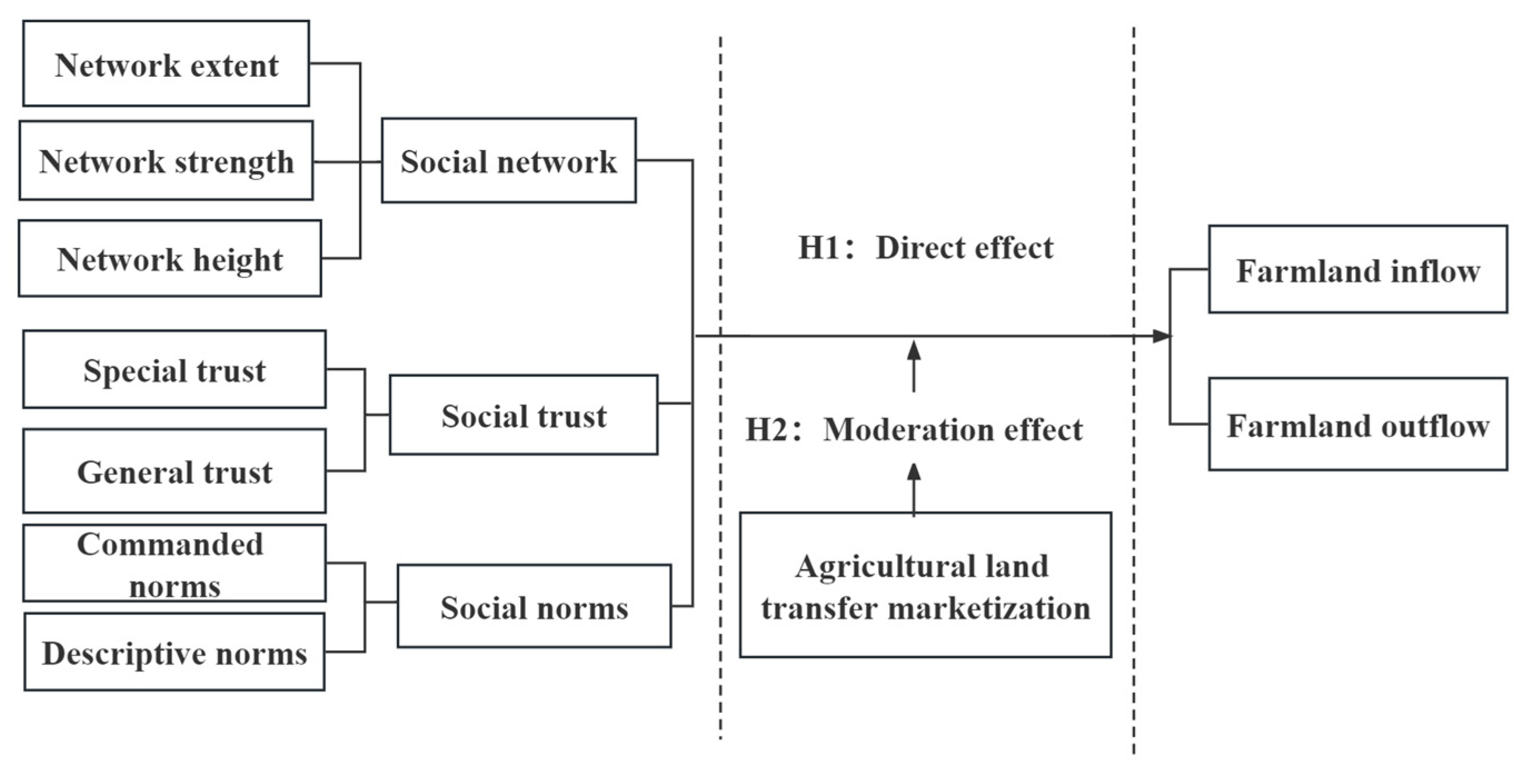

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Impact of Social Capital on Agricultural Land Transfer

2.2. Regulation Effect of Marketization of Agricultural Land Transfer

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Explained Variables

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Adjustment Variable

3.3. Model Construction

3.3.1. Probit Model

3.3.2. SUEST Inspection

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the IMPACT of Social Capital on Agricultural Land Transfer

4.1.1. Analysis of the Impact of Social Capital on the Farmland Transfer-Out

4.1.2. Analysis of the Impact of Social Capital on the Farmland Transfer-In

4.1.3. A Comparative Analysis of Social Capital on Farmland Transfer-In and Farmland Transfer-Out Decisions

4.2. The Moderating Effect of Marketization of Agricultural Land Transfer between Social Capital and Agricultural Land Transfer Decisions

4.2.1. Measurement of the Degree of Marketization of Agricultural Land Transfer and Analysis of the Results

4.2.2. Regression Analysis of the Regulating Effect of Market-based Agricultural Land Transfer

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Subsample Test Method

4.3.2. Model Replacement Method

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S. Land Sales and Rental Markets in Transition: Evidence from Rural Vietnam. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2007, 70, 67–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Carletto, C. Land Fragmentation, Cropland Abandonment, and Land Market Operation in Albania. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2108–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, N.; Ha, L.V.; Klump, R. Property Rights and Consumption Volatility: Evidence from a Land Reform in Vietnam. World Dev. 2013, 71, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Heerink, N.; van Ierland, E.; Shi, X. Land tenure insecurity and rural-urban migration in rural China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2014, 95, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, P.; Luca, M.; Mookherjee, D.; Pino, F. Evolution of land distribution in West Bengal 1967–2004: Role of land reform and demographic changes. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Zhuo, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, G. Exploration of Informal Farmland Leasing Mode: A Case Study of Huang Village in China. Land 2022, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wei, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, X. Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Land Circulation in Mountainous Chongqing in China Based on A Multi-Class Logistic Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boué, C.; Colin, J.-P. Land certification as a substitute or complement to local procedures? Securing rural land transactions in the Malagasy highlands. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, M.; Holden, S.T.; Tilahun, M. Tenants’ land access in the rental market: Evidence from northern Ethiopia. Agric. Econ. 2019, 50, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Sun, D.; Ma, C. The Impact of Farmland Transfers on Agricultural Investment in China: A Perspective of Transaction Cost Economics. China World Econ. 2019, 27, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.T.; Ghebru, H. Land rental market legal restrictions in Northern Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklu, T.; Lemi, A. Factors affecting entry and intensity in informal rental land markets in Southern Ethiopian highlands. Agric. Econ. 2004, 30, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promsopha, G. Land Ownership as Insurance and the Market for Land: A Study in Rural Vietnam. Land Econ. 2015, 91, 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, B.; Yu, L.; Yang, H.; Yin, S. Social capital, land tenure and the adoption of green control techniques by family farms: Evidence from Shandong and Henan Provinces of China. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, G. Does guanxi matter to nonfarm employment? J. Comp. Econ. 2003, 31, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbay, A.G.; Rutten, R.P.J.H.; De Graaf, P.M. Social capital, geographical distance and transaction costs: An empirical analysis of social networks in african rural areas. Rev. Urban Reg. Dev. Stud. 2018, 30, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cai, Z.; Wang, J.; Qin, X. Impacts of risk aversion and social networks on the contract period of land transfer. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2021, 45, 217. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Han, H.; Ying, S. Reputation Effect on Contract Choice and Self-Enforcement: A Case Study of Farmland Transfer in China. Land 2022, 11, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, S.; Ma, X.; Lan, J. Heterogeneity in interventions in village committee and farmland circulation: Intermediary versus regulatory effects. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, N.; Wang, M.; Liu, Z. Farmland Transfer, Scale Management and Economies of Scale Assessment: Evidence from the Main Grain-Producing Shandong Province in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.-h.; Wang, D. Social capital, marketization and rural poverty reduction—Evidence from rural micro survey. J. Guizhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2020, 38, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Poppo, L.; Zenger, T. Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, P.; Cao, M.; Xu, X. Relationships among mental health, social capital and life satisfaction in rural senior older adults: A structural equation model. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H. Structural Social Capital, Household Income and Life Satisfaction: The Evidence from Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong-Province, China. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 17, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Li, E.; Su, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, L. Social Capital, Crop Specialization and Rural Industry Development—Taking the Grape Industry in Ningling County of China as an Example. Land 2022, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, L. Social capital for rural revitalization in China: A critical evaluation on the government’s new countryside programme in Chengdu. Land Use Policy 2019, 91, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, W.; Pang, S. Exploring the Role of Land Transfer and Social Capital in Improving Agricultural Income under the Background of Rural Revitalization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y. Satisfaction principle or efficiency principle? Decision-making behavior of peasant households in China’s rural land market. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasarian, C.; Bourdieu, P.; Nice, R. Sociology in Question. Anthr. Q. 1995, 68, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social networks and status attainment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1999, 25, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.D. Job Search and Network Composition: Implications of the Strength-Of-Weak-Ties Hypothesis. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1992, 57, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Simon and Schuster: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, Y.M.; Jung, C.S. Focusing the mediating role of institutional trust: How does interpersonal trust promote organizational commitment? Soc. Sci. J. 2015, 52, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Heerink, N.; van Ierland, E.; Lang, H.; Shi, X. Decisions by Chinese households regarding renting in arable land—The impact of tenure security perceptions and trust. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H. Impact of Relationship Governance and Third-Party Intervention on Farmland Transfer Rents—Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Land 2022, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Halder, P.; Zhang, X.; Qu, M. Analyzing the deviation between farmers’ Land transfer intention and behavior in China’s impoverished mountainous Area: A Logistic-ISM model approach. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Hou, Y. Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Voluntary Field Water Management Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Projects Based on a Context–Attitude–Behavior Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yu, L.; Yang, H. Influence of a new agricultural technology extension mode on farmers’ technology adoption behavior in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 76, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neef, A.; Benge, L.; Boruff, B.; Pauli, N.; Weber, E.; Varea, R. Climate adaptation strategies in Fiji: The role of social norms and cultural values. World Dev. 2018, 107, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commerçon, F.A.; Zhang, M.; Solomon, J.N. Social norms shape wild bird hunting: A case study from southwest China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 32, e01882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, K.; Schultz, P.W. Social Norms and Pro-Environmental Behaviour. In Environmental Psychology: An Introduction; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Molleman, L.; van Dolder, D. Do descriptive social norms drive peer punishment? Conditional punishment strategies and their impact on cooperation. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2021, 42, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byambaa, M.; Yamada, K. Descriptive social norms and herders’ social insurance participation in Mongolia: A survey experiment. J. Int. Dev. 2022, 35, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; He, Q. Does Land Rent between Acquaintances Deviate from the Reference Point? Evidence from Rural China. China World Econ. 2020, 28, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X. A Study on the Current Agricultural Land Transfer Information Platform. In Proceedings of the 2017 4th International Conference on Machinery, Materials and Computer (MACMC 2017), Xi’an, China, 27–29 November 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, O.M.; De Vries, J.R.; Klerkx, L.; Poortvliet, P.M. Why are cluster farmers adopting more aquaculture technologies and practices? The role of trust and interaction within shrimp farmers’ networks in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Aquaculture 2020, 523, 735181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, Y. Rural households’ willingness to accept compensation for energy utilization of crop straw in China. Energy 2018, 165, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Z.; Kong, F. How to encourage farmers to recycle pesticide packaging wastes: Subsidies VS social norms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H. Explanation of the Phenomenon “Different Prices on the Same Land” in the Farmland Transfer Market—Evidence from China’s Farmland Transfer Market. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataza, R.R.; Doole, G.J.; Kragt, M.E.; Hailu, A. Information acquisition, learning and the adoption of conservation agriculture in Malawi: A discrete-time duration analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 132, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Safa, L.; Damalas, C.A.; Ganjkhanloo, M.M. Drivers of farmers’ intention to use integrated pest management: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, R.; LI, L. Research on Social Capital’s Impact on the Cultivated Land Availability of Peasant Households in China. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 13, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Zheng, S.; Kaabar, M.K.A.; Yue, X.-G. Online or offline? The impact of environmental knowledge acquisition on environmental behavior of Chinese farmers based on social capital perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Hu, F. Study on the Influence of Social Capital on Farmers’ Participation in Rural Domestic Sewage Treatment in Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Z.; Shi, D.J.; Wen, H.X. The influence of relational networks on land transfer behavior and rents: An analysis based on the perspective of strong and weak relational networks. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2020, 7, 106–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.G.; Liu, J.D.; Huo, X.X. The impact of social trust on agricultural land rental market. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 20, 128–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Chen, Q.H. Is there a social interaction effect on farmers’ farmland transfer behavior? China Land Sci. 2020, 34, 44–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Q.; Fahad, S.; Kagatsume, M.; Yu, J. Impact of Off-Farm Employment on Farmland Transfer: Insight on the Mediating Role of Agricultural Production Service Outsourcing. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | Category | Frequency/Person | Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <35 years old | 7 | 0.69 |

| 35~45 years | 43 | 4.23 | |

| 46~55 years | 234 | 23.01 | |

| 56~65 years | 326 | 32.06 | |

| Age 66 and over | 407 | 40.02 | |

| Education level | Never attended school | 299 | 29.40 |

| Primary school | 425 | 41.80 | |

| Junior middle school | 203 | 20.00 | |

| High school | 82 | 8.10 | |

| College and above | 8 | 0.80 | |

| Gender | Male | 631 | 62.00 |

| Female | 386 | 38.00 | |

| Annual household income | Less than 10,000 yuan | 31 | 3.05 |

| 10,000~30,000 yuan | 131 | 12.88 | |

| 30,000~50,000 yuan | 136 | 13.37 | |

| 50,000~80,000 yuan | 198 | 19.47 | |

| 80,000~140,000 yuan | 272 | 26.75 | |

| 140,000~200,000 yuan | 127 | 12.49 | |

| More than 200,000 yuan | 122 | 12.00 |

| Variable Name | Variable Description | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer-out or not | Yes = 1; No = 0 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.571 | 0.494 |

| Transfer-in or not | Yes = 1; No = 0 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.263 | 0.440 |

| Social networks | Calculated value by entropy method | 0.005 | 0.653 | 0.143 | 0.109 |

| Social trust | Calculated value by entropy method | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.604 | 0.201 |

| Social norms | Calculated value by entropy method | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.626 | 0.220 |

| Gender | Male = 1; Female = 0 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.620 | 0.486 |

| Age | The actual age of the interviewee/year | 30.000 | 87.000 | 61.540 | 9.660 |

| Level of education | No schooling = 1; Primary = 2; Junior high school = 3; High school (technical secondary school) = 4; College and above = 5 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 2.090 | 0.938 |

| Area of household contracted land | Household-contracted cultivated land area | 0.000 | 30.000 | 7.1514 | 4.398 |

| Overall quality of cultivated land | Very poor~very good = 1~5 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 3.620 | 0.799 |

| Family size | Family population/unit | 1.000 | 11.000 | 4.100 | 1.608 |

| Number of farmers participating in cooperatives | Number of participating farmers’ cooperatives/unit | 0.000 | 5.000 | 0.260 | 0.557 |

| Landform of the village | Plain = 1; Hill = 2; Mountain = 3 | 1.000 | 3.000 | 1.660 | 0.764 |

| Distance between the village and the nearest town | Distance from rural household to urban government/km | 5.000 | 66.000 | 26.030 | 13.936 |

| Marketization degree of agricultural land transfer | Calculated value by entropy method | 0.326 | 0.980 | 0.453 | 0.240 |

| Transfer-Out or Not | Transfer-In or Not | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Name | (1) Probit | (2) Marginal Effect | (3) Probit | (4) Marginal Effect | (5) Probit | (6) Marginal Effect | (7) Probit | (8) Marginal Effect |

| Social networks | 1.490 ** (2.17) | 0.439 ** (2.19) | 2.861 *** (2.82) | 0.528 *** (2.90) | ||||

| Social network breadth | 0.788 * (1.83) | 0.230 * (1.84) | 0.995 * (1.68) | 0.181 * (1.67) | ||||

| Social network strength | 1.301 ** (2.23) | 0.379 ** (2.25) | 2.248 ** (2.51) | 0.409 ** (2.51) | ||||

| Social network height | 0.033 (0.10) | 0.010 (0.10) | 0.296 (1.36) | 0.054 (1.37) | ||||

| Social trust | 1.563 *** (3.70) | 0.461 *** (3.80) | 2.604 *** (3.69) | 0.480 *** (3.78) | ||||

| Special trust | 1.266 *** (3.21) | 0.369 *** (3.27) | 1.271 ** (2.22) | 0.231 ** (2.25) | ||||

| General trust | 0.391 (1.16) | 0.114 (1.16) | 1.171 ** (2.05) | 0.213 ** (2.09) | ||||

| Social norms | 1.740 *** (5.40) | 0.460 *** (4.65) | 1.688 *** (2.76) | 0.311 *** (2.82) | ||||

| Descriptive specification | 0.652 ** (2.39) | 0.190 ** (2.42) | 0.558 (1.13) | 0.102 (1.12) | ||||

| Imperative specification | 0.987 *** (3.25) | 0.288 *** (3.32) | 1.229 *** (2.93) | 0.224 *** (2.97) | ||||

| Gender | 0.074 (0.73) | 0.022 (0.73) | 0.087 (0.84) | 0.025 (0.84) | 0.109 (0.67) | 0.020 (0.67) | 0.096 (0.57) | 0.017 (0.58) |

| Age | −0.002 (−0.24) | −0.000 (−0.24) | −0.002 (−0.24) | −0.000 (−0.24) | −0.008 (−0.76) | −0.001 (−0.76) | −0.005 (−0.47) | −0.001 (−0.47) |

| Level of education | −0.223 *** (−3.29) | −0.066 *** (−3.35) | −0.250 *** (−3.52) | −0.073 *** (−3.60) | −0.017 (−0.16) | −0.003 (−0.16) | −0.013 (−0.13) | −0.002 (−0.13) |

| Area of household-contracted land | 0.043 *** (3.59) | 0.013 *** (3.68) | 0.046 *** (3.71) | 0.013 *** (3.82) | −0.032 (−1.48) | −0.006 (−1.49) | −0.032 (−1.47) | −0.006 (−1.48) |

| The overall quality of cultivated land | −0.059 (−0.96) | −0.017 (−0.96) | −0.057 (−0.89) | −0.017 (−0.89) | −0.174 * (−1.78) | −0.032 * (−1.79) | −0.148 (−1.20) | −0.027 (−1.22) |

| Family size | −0.082 * (−1.90) | −0.024 * (−1.92) | −0.080 * (−1.84) | −0.023 * (−1.85) | 0.327 *** (4.61) | 0.060 *** (4.84) | 0.332 *** (4.88) | 0.060 *** (5.16) |

| Number of farmers participating in cooperatives | 2.185 *** (7.60) | 0.644 *** (8.22) | 2.199 *** (7.62) | 0.641 *** (8.24) | 2.141 *** (6.14) | 0.395 *** (6.66) | 2.048 *** (4.35) | 0.372 *** (4.99) |

| Number of non-farm employed labor force | 0.165 *** (2.95) | 0.049 *** (3.00) | 0.161 *** (2.86) | 0.047 *** (2.90) | −0.341 *** (−4.00) | −0.063 *** (−4.14) | −0.358 *** (−4.21) | −0.065 *** (−4.43) |

| Landform of the village | −0.034 (−0.46) | −0.010 (−0.46) | −0.043 (−0.58) | −0.013 (−0.59) | 0.169 (1.45) | 0.031 (1.45) | 0.172 (1.35) | 0.031 (1.38) |

| Distance between the village and the nearest town | −0.007 * (−1.71) | −0.002 * (−1.72) | −0.005 (−1.40) | −0.002 (−1.40) | −0.006 (−0.94) | −0.001 (−0.94) | −0.005 (−0.80) | −0.001 (−0.81) |

| The marketization of agricultural land circulation | 0.599 *** (2.73) | 0.175 *** (2.77) | 0.602 *** (2.60) | 0.174 *** (2.63) | 1.05 *** (2.72) | 0.181 *** (2.77) | 1.027 *** (2.61) | 0.175 *** (2.65) |

| Wald chi-square value | 139.810 | 155.170 | 1117.17 | 114.65 | ||||

| p value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Observation value | 1017 | 1017 | 1017 | 1017 | ||||

| Rate of Agricultural Land Transfer | Rate of Paid Transfer of Agricultural Land | Rate of Open Transfer of Agricultural Land | Stability of Agricultural Land Transfer Period | Marketization of the Target of Agricultural Land Transfer | Liberalization of Agricultural Land Transfer Method | Promotion Rate of Agricultural Land Transfer policy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weights | 0.086 | 0.130 | 0.093 | 0.115 | 0.116 | 0.169 | 0.290 |

| Region | Rate of Agricultural Land Transfer | Rate of Paid Transfer of Agricultural Land | Rate of Open Transfer of Agricultural Land | Stability of Agricultural Land Transfer Period | Marketization of the Target of Agricultural Land Transfer | Liberalization of Agricultural Land Transfer Method | Promotion Rate of Agricultural Land Transfer Policy | Degree of Marketization of Agricultural Land Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wuhan | 0.043 | 0.064 | 0.093 | 0.115 | 0.031 | 0.169 | 0.290 | 0.805 |

| Yichang | 0.076 | 0.112 | 0.072 | 0.113 | 0.098 | 0.147 | 0.270 | 0.889 |

| Jingzhou | 0.000 | 0.130 | 0.066 | 0.105 | 0.116 | 0.016 | 0.080 | 0.514 |

| Xiaogan | 0.086 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.087 | 0.298 |

| Jingmen | 0.086 | 0.088 | 0.061 | 0.076 | 0.052 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.376 |

| Enshi | 0.079 | 0.030 | 0.058 | 0.088 | 0.076 | 0.035 | 0.012 | 0.379 |

| Tianmen | 0.071 | 0.042 | 0.037 | 0.024 | 0.058 | 0.124 | 0.000 | 0.357 |

| Explain Variables | Transfer-Out or Not | Transfer-In or Not | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Value Group | High-Value Group | Low-Value Group | High-Value Group | |

| Social networks | 3.511 *** (3.77) | 1.442 * (1.64) | 7.469 *** (5.75) | 3.075 * (1.92) |

| Social trust | 2.584 *** (3.83) | 0.976 (1.58) | 6.047 *** (3.97) | 2.047 * (1.75) |

| Social norms | 1.740 *** (5.40) | 2.391 *** (4.89) | 2.211 * (1.92) | 2.135 ** (1.98) |

| Gender | −0.058 (−0.34) | 0.106 (0.79) | −0.407 (−1.41) | 0.752 ** (2.54) |

| Age | 0.009 (0.92) | −0.005 (−0.65) | −0.014 (−0.77) | −0.002 (−0.14) |

| Level of education | −0.198 * (−1.84) | −0.220 ** (−2.38) | −0.066 (−0.34) | −0.068 (−0.38) |

| Area of household-contracted land | 0.020 (0.99) | 0.062 *** (3.63) | −0.025 (−0.59) | −0.003 (−0.10) |

| The overall quality of cultivated land | −0.062 (−0.59) | −0.126 (−1.55) | −0.266 (−1.57) | −0.142 (−0.86) |

| Family size | −0.098 (−1.30) | −0.106 * (−1.92) | 0.284 ** (2.25) | 0.325 *** (2.73) |

| Number of farmers participating in cooperatives | 2.022 *** (4.64) | 2.492 *** (5.47) | 1.751 *** (3.26) | 2.662 *** (4.32) |

| Number of non-farm employed labor force | 0.098 (1.11) | 0.235 *** (2.91) | −0.430 *** (−2.84) | −0.341 ** (−2.19) |

| Landform of the village | 0.223 ** (2.16) | −0.288 ** (−2.38) | 0.282 (1.56) | −0.081 (−0.36) |

| Distance between the village and the nearest town | −0.010 (−1.57) | −0.003 (−0.44) | −0.002 (−0.18) | −0.005 (−0.43) |

| Wald chi-square value | 105.620 | 230.050 | 170.740 | 150.560 |

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Observation value | 342 | 538 | 252 | 266 |

| Explain Variables | Transfer-Out or Not | SUR | Transfer-In or Not | SUR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Low-Value Group | High-Value Group | Chi2 and p | Low-Value Group | High-Value Group | Chi2 and p | |

| Society Network | 3.511 *** (3.77) | 1.442 * (1.64) | Chi2 = 2.72 p = 0.099 | 7.469 *** (5.75) | 3.075 * (1.92) | Chi2 = 3.85 p = 0.050 |

| Society Trust | 2.584 *** (3.83) | 0.976 (1.58) | Chi2 = 3.21 p = 0.073 | 6.047 *** (3.97) | 2.047 * (1.75) | Chi2 = 6.53 p = 0.011 |

| Society Standard | 1.740 *** (5.40) | 2.391 *** (4.89) | Chi2 = 10 p = 0.002 | 2.211 * (1.92) | 2.135 ** (1.98) | Chi2 = 0 p = 0.955 |

| Observation value | 342 | 538 | 880 | 252 | 266 | 518 |

| Transfer-Out or Not | Transfer-In or Not | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Name | (1) Probit | (2) Marginal Effect | (3) Probit | (4) Marginal Effect | (5) Probit | (6) Marginal Effect | (7) Probit | (8) Marginal Effect |

| Social networks | 2.369 ** (2.81) | 1.033 ** (4.37) | 4.518 *** (4.09) | 0.791 *** (4.54) | ||||

| Social network breadth | 1.654 *** (2.76) | 0.536 *** (2.82) | 1.332 * (1.47) | 0.265 * (1.50) | ||||

| Social network strength | 2.227 *** (2.91) | 0.721 *** (3.01) | 2.589 * (1.82) | 0.515 * (1.86) | ||||

| Social network height | 0.430 (0.95) | 0.139 (0.95) | 0.527 (0.99) | 0.105 (1.00) | ||||

| Social trust | 2.739 *** (4.11) | 0.692 *** (3.65) | 5.957 *** (4.99) | 1.044 *** (5.75) | ||||

| Special trust | 1.157 ** (2.04) | 0.375 ** (2.07) | 1.580 * (1.75) | 0.314 * (1.78) | ||||

| General trust | 0.118 (0.24) | 0.383 (0.24) | 0.537 *** (3.33) | 0.505 *** (3.52) | ||||

| Social norms | 1.997 *** (3.73) | 0.616 *** (4.02) | 2.332 *** (2.59) | 0.409 *** (2.68) | ||||

| Descriptive specification | 1.160 *** (3.04) | 0.376 *** (3.14) | 0.466 (0.62) | 0.093 (0.62) | ||||

| Imperative specification | 1.555 *** (3.58) | 0.504 *** (3.75) | 2.284 *** (3.08) | 0.455 *** (3.26) | ||||

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Wald chi-square value | 93.19 | 101.72 | 119.40 | 95.05 | ||||

| p value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Observation value | 420 | 420 | 261 | 261 | ||||

| Transfer-Out or Not | Transfer-In or Not | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Name | (1) Probit | (2) Marginal Effect | (3) Probit | (4) Marginal Effect | (5) Probit | (6) Marginal Effect | (7) Probit | (8) Marginal Effect |

| Social networks | 1.602 * (1.84) | 0.454 * (1.86) | 3.219 *** (2.60) | 0.616 *** (2.74) | ||||

| Social network breadth | 0.567 (0.97) | 0.191 (0.97) | 0.216 (0.22) | 0.043 (0.22) | ||||

| Social network strength | 1.337 * (1.43) | 0.450 * (1.44) | 2.866 ** (2.15) | 0.568 ** (2.20) | ||||

| Social network height | 0.151 (0.38) | 0.507 (0.38) | 0.189 (0.31) | 0.374 (0.31) | ||||

| Social trust | 2.389 *** (3.86) | 0.678 *** (4.09) | 4.531 *** (4.30) | 0.867 *** (4.86) | ||||

| Special trust | 1.091 ** (2.15) | 0.367 ** (2.19) | 1.796 * (1.76) | 0.356 * (1.79) | ||||

| General trust | 0.666 * (1.58) | 0.224 * (1.59) | 2.372 *** (2.66) | 0.470 *** (2.77) | ||||

| Social norms | 1.208 *** (2.72) | 0.343 *** (2.79) | 2.584 *** (3.36) | 0.495 *** (3.62) | ||||

| Descriptive specification | 1.436 *** (3.49) | 0.483 *** (3.64) | 0.892 (0.93) | 0.177 (0.94) | ||||

| Imperative specification | 0.355 (0.95) | 0.120 (0.95) | 0.363 * (1.74) | 0.270 * (1.77) | ||||

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Wald chi-square value | 156.03 | 148.41 | 130.26 | 127.54 | ||||

| p value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Observation value | 462 | 462 | 252 | 252 | ||||

| Variable Name | Transfer-Out or Not | Transfer-In or Not |

|---|---|---|

| Social networks | 1.937 *** (3.25) | 8.961 *** (5.44) |

| Social trust | 0.513 * (1.65) | 5.755 *** (3.48) |

| Social norms | 1.753 *** (5.25) | 2.918 ** (2.01) |

| Marketization | 1.661 *** (4.95) | 7.640 ** (2.21) |

| Social network * Marketization | −3.549 * (−1.70) | −12.830 *** (−2.95) |

| Social trust * Marketization | −2.700 * (−1.76) | −6.409 * (−1.67) |

| Social norms * Marketization | 2.382 * (1.67) | −1.655 (−0.51) |

| Other variables | Control | Control |

| Wald chi-square value | 334.080 | 311.450 |

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.277 | 0.527 |

| Observation value | 1017 | 1017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhu, Q. Study on the Impact of Social Capital on Agricultural Land Transfer Decision: Based on 1017 Questionnaires in Hubei Province. Land 2023, 12, 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040861

Chen Y, Qin Y, Zhu Q. Study on the Impact of Social Capital on Agricultural Land Transfer Decision: Based on 1017 Questionnaires in Hubei Province. Land. 2023; 12(4):861. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040861

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yinrong, Yanqing Qin, and Qingying Zhu. 2023. "Study on the Impact of Social Capital on Agricultural Land Transfer Decision: Based on 1017 Questionnaires in Hubei Province" Land 12, no. 4: 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040861

APA StyleChen, Y., Qin, Y., & Zhu, Q. (2023). Study on the Impact of Social Capital on Agricultural Land Transfer Decision: Based on 1017 Questionnaires in Hubei Province. Land, 12(4), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040861