Abstract

The main aim of the study was reflecting on performative implications of the urban commons and their relational ability (i.e., inter- and/or intra-actioning) within an inclusive governance model and policy design context through two interpretative keys: Ostrom’s idea of sustainability and the recent hybrid neo-materialist urban and organizational theoretical path grounded within the Metzger–Barad–Latour analyses. Firstly, we focused on defining the theoretical setting, background and selected codes. The resulting scheme was tested with a mixed methodology within the case study of the Lido Pola Commons in Naples, Southern Italy. Empirical analysis benefits from long-lasting research experience on the area and an action-research processes aimed at codesigning a living civic lab. The discussion illustrates the main pivots of the internal/external validation of the case study results, thus contributing to enhancing a participatory policy design by raising awareness regarding social intra/interactions.

1. Introduction

The present paper addresses the commons’ self-organization models and their governance issues by combining different epistemological approaches. The main aim of the study was reflecting on performative implications of the urban commons and their relational ability within an inclusive governance model and policy design context through two interpretative keys: Ostrom’s idea of sustainability and the recent hybrid neo-materialist urban and an organizational theoretical path grounded within the Metzger–Barad–Latour (M–B–L) approach [1,2,3].

To this end, this article explores and discusses the urban commons agency capacity by developing a novel theoretical coding based on the combination of Ostrom’s model and a hybrid neo-materialist-based approach. This latter, mostly conveyed by the seminal Karen Barad articles published between 2003 and 2011, considers the “agential realism” logical process as a new method of scientific interpretation of urban phenomena [3,4,5].

The well-known organizational model of the commons developed by Elinor Ostrom (1990) introduced a concept of relative sustainability. In this framework, she addressed the question of “how to enhance the capabilities of those involved to change the constraining rules of the game to lead to outcomes other than remorseless tragedies” [6] (p. 7). She suggested, in other words, a collective action model in which “a group of principals can organize themselves voluntarily to retain the residual of their own efforts” [6] (p. 25). Her idea was indeed to analyze the organizational and institutional arrangements and thus to define the rules to avoid Hardin’s inner concern summarized within the iconic title of “The tragedy of the commons” [7].

The system of rules provided within the aforementioned governance model structures the social interaction of appropriators of the commons and conditions their ability to discuss, decide on, and monitor self-imposed constraints: “many groups can effectively manage and sustain common resources if they have suitable conditions, such as appropriate rules, good conflict-resolution mechanisms, and well-defined group boundaries” [8] (p. 11).

Considering that shared resources have become a part of everyday urban life, the inherent governance model has been transitioned from natural to urban resources discourse [9,10,11,12,13]. In so doing, it has been implemented within formal and informal practices, as well as in urban planning and management practices [14]. The discourse regarding the intermingling of urban agendas and governance models of the commons has been strongly influenced by Ostrom’s seminal theoretical guidelines [15]. Her positions supported thoroughly the portability of the commons approaches from the natural to the urban environment [16]. Recently, scholars, practitioners, and activists have been revisiting those theoretical guidelines in order to better address issues and opportunities on an urban scale ([17,18,19,20], among others).

In order to investigate this commons conceptual migration in more depth, some studies [21] have suggested reviewing the specific literature to identify the characteristics of urban resources that make them different from natural ones (i.e., subtractability vs. relationality). Following these authors [21], an understanding of the emerging differences could offer important opportunities in dealing with commons’ managerial challenges and in interpreting specific social “intra-actioning,” as defined by Barad.

The main reference for the inherent policy-design theoretical context is the hybridization of an urban planning and regional sustainable development model [1,22,23] with Latour’s ideas about the definition of the urban governance field of action (the “we” of the governance field) [2,24,25,26].

At a policy level, the above two theories could be complemented by the idea of inherent urban, current, and auspicated cultural formulae [27]. Within this range, the two extremes are defined through the main cultural schemas, imagined to be bordered by a “persistent cultural preconception status” and a “post-Anthropocene auspicated “we”.” Between them, the commons are playing a crucial role in the politics of conviviality, urban resilience, and environmental sustainability, as “communing” toward resilience could be the key to sustainable and inclusive urban development [28,29]. It is “not just about learning about how humans and animals cope on their own with living in the city, but rather a program with a transformative ambition of becoming-together. It purports to reassemble both ecologies as urban and cities as ecological through the conceptualization of urban inhabitants as always—already entangled and more-than-human; more-than-animal; more-than-plant…complex assemblages, mutually affecting and affected by their fields of becoming” [22] (p. 120). A sustainable city, as considered in the context of our analysis, should be a place of cohabitation in the face of intense differences [30], and where even more people claim the necessity of a new more-than-human sensibility as well as policies for urban multispecies conviviality [22].

In order to deeply understand the interpretative capacity of both theoretical frameworks (Ostrom and neo-materialist), the authors observed and decoded an urban commons’ experience (governance or assemblages) and its contribution to a sustainable city: the Lido Pola Commons in Naples.

The following text is arranged in three main sections corresponding to the research process, anticipated by the rationale and research protocol. The theoretical setting Section 3 introduces the two epistemological theories and the resulting theoretical coding of the relationships–results commons dynamic. Section 4 is dedicated to the testing phase, in which the researchers collected a case study context description and the narrative of experiencing a codesigning civic lab. The discussion Section 5 illustrates the main pivots of the internal/external validation of the case study results. Finally, the conclusions summarize theoretical and practical evidence, adding some policy implications.

2. Research Protocol

This paper is part of a research process in which an interdisciplinary group of scholars based in Naples within the Institute of Research on Innovation and Services for Development (IRISS) of the National Research Council of Italy (CNR) started reflecting from different perspectives on the experience of commons and the community’s initiatives embedded in urban regeneration processes [31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

By engaging communities and interpreting networks related to different topics emerged the need of filling a gap regarding tools for understanding the overlapping of the growing shared experiences and informal community initiatives with the hierarchical systems of rules embedded in urban planning and governance models [38,39,40]. The debate on evolutionary planning and the need to redefine forms and outcomes of participatory processes within urban regeneration initiatives encourages us to increasingly refine the theoretical horizon and operational toolkit [41]. No less crucial is the need to implement new approaches and procedures for assessing the social impacts of planning choices, so as to include the multiple variables at stake and promote territorial cohesion actions [42,43]. Observing how local tangible and intangible resources have been exploited within spontaneous initiatives in which neighborhood residents share a stake in informal agreements encouraged reflection on performative implications of the urban commons [14,44].

The emerging research gap can be summarized as the need of enhancing conceptualization and defining tools for understanding the commons agency capacity, considering their multidimensional nature and the multiplicity of different experiences included under the umbrella of sharing common resources.

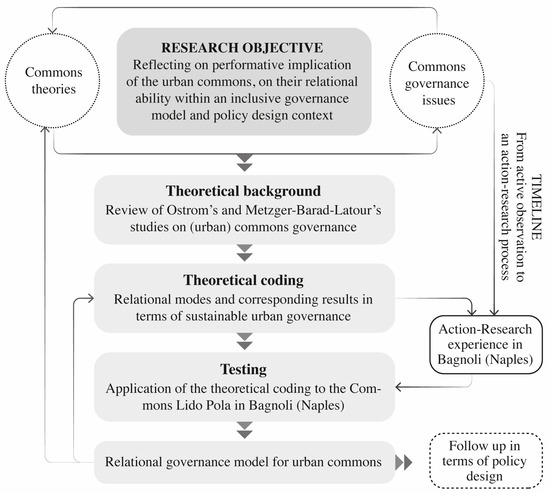

Figure 1 summarizes the research protocol that—in a continuous feedback process—addresses the issues and challenges of commons governance, combining incursions into current experiences and reinterpretations of established theories. Observing the dynamics and contributing to the current debate, the research group focuses on the commons relational ability within an inclusive governance model and policy design context.

Figure 1.

Research protocol (source: authors’ elaboration).

For this purpose, the article explores and discusses the urban commons agency capacity by developing a new theory based on the combination of Ostrom’s model and a hybrid neo-materialist-based approach. The theoretical setting has been designed through two interpretative keys: Ostrom’s idea of sustainability and the recent hybrid neo-materialist urban and organizational theoretical path grounded within the Metzger–Barad–Latour analyses. The resulting theoretical coding has been built extracting the relational modes from the combined theories.

As per the complexity of both the object of the study and the peculiarities of the internal dynamics and external relations of each experience, the research group has chosen to set a testing phase of theoretical coding within a purposefully selected commons experience. The case selection criteria refer to a relationality that addresses internal collaborative forms of the commons community domain and the exploration of relationships with the urban institutional framework and other players in the area.

To do so, the authors have chosen an experience that—in collaboration with a network of researchers and other territorial players—they are conducting on the Lido Pola commons in Naples, southern Italy. The empirical analysis benefits from long-lasting research experience on the area and a more recent action-research process aimed at codesigning a civic living lab (cf. Section 4). The turning point of the experience is the opening of the community to a collaboration with researchers and institutions to participate in funding calls that support civic and educational activities in the community. This process offers the opportunity of understanding the internal/external relational modes for a successful commons experience by applying to the case the theoretical relational coding presented in Section 3.3.

The expected result of the testing phase is the validation of the theoretical coding to be applied in understanding the relational modes as part of a novel dynamic governance model of the commons, thus contributing to enhancing a participatory policy design by raising awareness regarding social intra/interactions.

Each research phase includes a validation step and feedback, and during follow-up it will benefit on the one hand from a return on theories, introducing new elements, and on the other, from a public consensus on the definition of a relational and dynamic governance model of the commons.

3. Theoretical Setting

3.1. Ostrom and the Urban in Making “Regulatory Slippage”

The polycentric governance of common pool resources (CPRs), such as watersheds, fisheries, forests, grazing lands, land tenure and use, wildlife, and village organization [45], has been at the core of Elinor Ostrom’s eminent research contribution since the end of the last century. In Ostrom’s model, CPRs are a resource that appropriators can use, and whilst doing so, they diminish its value. No fish caught or tree felled is available for anyone else any longer. In this way, CPRs have a crucial feature: their substantial subtractability. To contrast Hardin’s ideas about the resources-in-common tragic ends, Ostrom organizes a successful third way of governing the commons based on institutional rules, where commoners would have focused all their efforts on organizing themselves voluntarily better than the Hardin’s herdsman would. While leaving the assumptions of (limited) rationality and self-interest untouched, she worked on the central role of institutional rules. In this, she was driven by the results obtained from a large number of empirical studies.

Following these ideas, the CPR case is well represented by a model in which self-evident resource (object) could be used and exploited by its appropriator (subject). In this form, it has been translated into urban studies for many years. Therefore, from this perspective, Foster was uncritically concerned about urban commons for free riding behaviors [46]. In addition, for this author, there was the crucial role of managerial capabilities in the commons models, but enforced by the word “collaborative”.

In terms of the widespread interest, felt within urban contexts, of privatized public spaces and the gap, Foster saw the reciprocal interest—among government agencies and other stakeholders—in collaborative management of urban commons, recognized as “regulatory slippage”. “[…] the tragedy of the urban commons unfolds during periods of “regulatory slippage” when the level of local government oversight and management of the resource significantly declines, leaving the resource vulnerable to expanded access by competing users and uses. Overuse or unrestrained competition in the use of these resources can quickly lead to congestion, rivalry, and resource degradation. Tales abound in cities across the country of streets, parks, and vacant land that were once thriving urban spaces but have become overrun dirty, prone to criminal activity, and virtually abandoned by most users” [46] (p. 57). Based on these statements, urban commons always work if in cooperation with local authorities. This cooperation (in both the modular forms of bonding or bridging) is the base or the precondition for sustainable commons governance in Ostrom’s inherent meaning.

The loss of effective regulation is what provides incentive for both citizens and governing bodies to find new means of addressing governance. Implications of these ideas about the centrality of cooperation in commons governance are relative to the need to conduct a balancing act so as not to crowd out civic engagement by excessive governmental presence, yet maintaining enough governmental control to avoid pitfalls of collective management, such as lack of accountability [46,47].

3.2. Metzger–Barad–Latour (M–B–L) Discourse about Urban Commons Relationality and Governance

An intense scientific debate about the urban version of Ostrom’s CPRs started since urban theorists began to recall and claim the relational nature of urban resources.

This approach can be traced back: when Ebenezer Howard and Una Stubbs developed the classical contribution of the urban theory represented in Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1902), in which they argued for another way of considering urban resources. What made urban resources (for example, a building) valuable is not in the bricks and mortar, but in the proximity to other buildings and the density of activities and services unfolding between them. Urban resources within this view are depicted by relations and no more considered subtractable in the use. Thus, and contra Ostrom’s and Foster’s subsequent model, commons are a relational phenomenon in cities, and this implies that urban commons do not revolve around the problem of free-riding [21].

Such modes of “collectivity” in the city considered by urban theorists and sociologists (see, for example, Wirth [48] and Simmel [49]) differentiate sources of human characters in the city. Following these authors, it is not only the city that provides stages for its inhabitants; rather, the inhabitants result from the conditions of city life. On the wave of these ideas, Susser and Tonnelat [50] proposed an alternative discussion about urban commons, adopting an important observation: the commons are far from being a resource awaiting deployment—the city constitutes its subjects. In particular, “urban commons are not simply out there, waiting to be exploited; rather, they must first be produced and then constantly reproduced” [51] (p. 12).

By sharing the need to bypass Ostrom’s ontological divide between subject–object, commoner–commons, and human–nonhuman, further analyses on urban commons have claimed that—more than an alternative conceptual solution—there is a substantial need to deconstruct the commons notion. This deconstruction would be driven by the need to recognize that any neat separation of “commons” on one hand and “commoners” on the other involves what philosopher Karen Barad calls an “agentic cut,” and as such, bears with it “an undisavowable ethico-political burden of responsibility to attend to the effects of any such enactment of ordering categories” [1] (p. 22).

Beyond overcoming the classical ontological divide, the new discourse about urban commons, following the neo-materialist Barad’s approach, would have been focused eminently on another kind of causality, no more a linear one in research on new forms of agency, and in finding new positioning for responsibility and accountability issues. Starting from these points would be a new challenge to discuss commons borders, where the problem was no more to know the number of (inevitable) exclusions, but to have knowledge of specific exclusions and responsibility to perpetually contest and rework the boundaries.

Thus, the approach includes both the agential realism of Barad and Latour’s social constructivism where the social practices are generally considered full of meaning and creativity. The shared incipit is about our need to accept Latour’s eminent suggestion to look at the fundamental environmental and social crisis issues in terms of localized actioning [52].

In order to come away from the representationalist idea of reality, Barad’s “agential realism” approach focuses on physics and arguments that deal with diffraction rather than reflection. “A diffractive reading of the insights from feminism, queer theory and science studies, crossing their perspectives, implies thinking about the social and scientific in a revealing way” [4] (p. 803). She therefore proposes an elaboration of the concept of performativity in a materialist, naturalist, and posthuman sense that dutifully recognizes matter as an active part of the world’s becoming in its continuous intra-activity.

To have a theoretical code for intra-activity in our research context, an excursion within scientific studies looking at the entanglement notion from quantum physics could be recommended. Leaving at another work the mission of getting on the specific insights, we can recall that to the early definition of quantum entanglement, introduced by Schrödinger in 1933, a great deal of research was made, since Einstein, and not only, who worked about the two bodies’ spatial distance (cfr. EPR paradox) or about the two bodies’ conjoint measurement and inherent correlations.

To progress the concept in our context, we could see entanglement as a particular kind of connection between two entities in which it is difficult setting borders between the two, where it will be difficult to say where the first finishes and the second begins, as they would be interconnected in the same conceptual space. Thus, in urban commons practices it could correspond to a new relationality through intra-actioning. The already known dimension of interaction (bonding and bridging), captured by relational data that define all the connotations of relationality (geographical distance, number of participants, causes and results), is added to or replaced by the dynamic of intra-action, i.e., of conducting actions together, also physically distant, although in discourse, the process underlying decision-making is structurally altered. In this way, the dynamics of “consensus-based decision-making” that are inherent to the commons community are conveyed into the decision-making process [53,54]. Consensus building through meeting and talking is a complex practice, characterized by long periods of time and constant commitment, which can produce a sense of liberation and fulfilment involving actors both individually and collectively. The latter are invited to expound their own opinions as well as to listen to those of others in a dynamic that, as opposition emerges, pushes for argumentation, the acceptance of disagreement and the coordination of positions that have emerged, even if in conflict with each other. For the purposes of empirical analysis, therefore, the capturing of relationship data becomes in turn a complex process aimed at capturing emerging and informal ties and then at narrating, for example, the construction of decisions as they come about.

3.3. Theoretical Coding

According to both theories, the relational models are the foundation of a successful management of the commons able to overcome the issues of an unlimited extraction of resources, free riding, and revisiting boundaries. Table 1 introduces the foundations of sustainable commons governance highlighted by the analysis of both theories.

Table 1.

Relational modes and corresponding results in terms of sustainable urban governance (source: authors’ elaboration).

The Ostrom approach has been summarized on the first line, extracting the interactions within a micro-situational level of analysis embedded in a broader socioecological system based on direct causal links and feedbacks in terms of relational modes and governance scenarios. The concepts of bonding and bridging are included within the broader topic of social capital. The latter is understood as the structure of relationships among people that foster cooperation and the production of material and symbolic values. The distinction between the two types of relationships can be traced back to Mark Granovetter’s [55] seminal work on embeddedness and the network approach, which is mainly used to access the topic of social capital from an economic perspective. Although there are a number of overlaps between the two concepts, one can refer to bonding as an exclusive, closed type of relationship characterized by strong ties and formed between people who are similar. This type of relationship tends towards isolation and is limited to reinforcing already existing ties, whereas bridging can refer to an inclusive, open type of relationship characterized by weak ties and formed among people with different characteristics. This type of relationship allows one to look outwards by acquiring information and advantages outside the network to which one belongs.

The M–B–L approach, included in the second line, goes beyond the human–nonhuman divide, modeling the tangible and intangible urban dynamics by ecologizing the urban commons. Although a concept ascribed to quantum physics, entanglement has acquired its own authority in the social sciences to explain more profoundly how relationships between two components can work. It starts from the assumption that each of us is entangled with every human and nonhuman with whom we come into contact and with whom we share a meaningful experience. Specifically, the entanglement is a relationship in which the “components,” be they social groups, individuals, places, ideas or discourse, cyborgs, animals, or mechanical devices, are closely linked and intertwined in such a way that they don not forget their own counterpart.

While the first theory emphasizes a relational model of bridging and/or bonding that follows an a priori defined system of cooperation rules, in the neo-materialist approach, the authors agree to focus on a relational model based on entanglement. The latter is mainly rooted in entangling modes, favoring also the emotional relationship between the players, resulting in more inclusivity.

The following table has been designed in order to capture the complexity of human–nonhuman relationships within the urban environment as well as to push forward a renewed vision of the commons for a sustainable collective governance model.

4. Testing Phase

In the framework of this disembodied vision of the commons as relational system, the authors purposely selected a case to be studied in order to test the interpretative synopsis. Antecedent to this choice, there is the direct involvement of members of the research group in the Permanent Citizen Observatory of Urban Commons1. Although there is deep reciprocal knowledge, our observational position with respect to the local commons is, for many reasons, of external third.

The selection criteria have been highlighted in the research protocol (cf. Section 2), including the following requirements: the urban scale, the presence of commons recognized through a system of rules or through the spontaneous commitment of a composite community of social actors, and, finally the opening of a new phase of dialogue with external institutional subjects for accessing funding opportunities and improving the supply of services for the communities involved. According to these premises, the experience of the civic community known under the Lido Pola Commons (Lido Pola Bene Comune) definition has been identified as an analysis framework. The community of Lido Pola has shared with the research group a turning point in their experiences by developing a transformative process inspired by an action-research model [57]. The latter criterion is critical in terms of allowing the identification of an observation framework that is open to dialogue and exchange. The selected case offers the opportunity to test the theoretical coding in order to understand the intermingling among the relational structure and the governance model.

The Lido Pola community established its geographical location in Bagnoli, a beautiful but depleted neighborhood on the west coast of Naples characterized by a long history (1903–1992) of production and withdrawal of a heavy metallurgy plant. This makes the community a potential hinge between environmental and social ecosystems and an ideal place to experiment with an ecosystem for innovation.

The experience is presented in narrative form, starting with a section dedicated to set the context in terms of planning overlapping in the area and in terms of evolutionary process of the community as a whole since its constitution in 2016. The crucial turning point runs from October 2021 to June 2022, when the Lido Pola community, established through an informal (illegal) occupation turned into an urban commons recognized by the local authorities and decided to start submitting applications for public funding. This transition in thinking and the related actions represent a challenge in terms of revisiting the informality, thus maintaining an inclusive and horizontal way of interacting. The survival of the informal community with porous and variable borders, beyond the public funding and an intense social intra-action construction, will reveal a successful outcome in terms of urban sustainability. The expected results of the application of the theoretical coding (Table 1) are the understanding of relational modes experienced within the following experience.

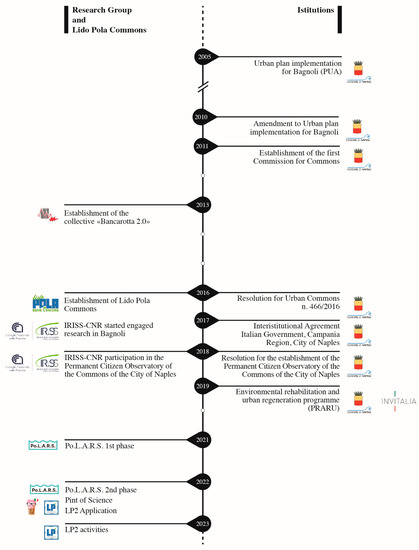

The timeline in Figure 2 illustrates the interaction among the researchers, the study area, and the Lido Pola Commons on the one hand and the main institutional steps of the planning process in the area on the other, in order to better understand the transition from the active observation [58] to the embedded action research [57]. The authors’ positioning with respect to the Lido Pola Commons in Naples is evolutive in itself. It started (2015–2019) as an external third, then (2019–2021) become an institutional bond, and finally (2021–today) it became a kind of entanglement formed by direct and indirect reciprocal participation. The narrative of the research experience in progress in the area aims at identifying and systematizing relational modes within the theoretical coding scheme.

Figure 2.

Research timeline: from active observation to action research in the Bagnoli district, focusing on the Lido Pola Commons establishment and evolution (source: authors’ elaboration).

4.1. Materials and Timing

The area in which Lido Pola is located is characterized by significant environmental, social and economic fragility, with the Bagnoli district at the center of a decades-long demand for regeneration following the process of withdrawal and reconversion of the former industrial area that is still unfinished. The environmental rehabilitation of the brownfield left by the former industrial settlements has been the focus of the public investments and the institutional debate, leaving little room for discussing thoroughly the local demands of regeneration. The geomorphological, environmental, economic, social and cultural characteristics of the area have produced the overlapping of planning tools at different levels and sectors. The area is also included in the Programme for Environmental Restoration and Urban Regeneration (PRARU, 2019) and the former (PUA, 2005) Urban Plan Implementation. A short circuit among planning and decision-making processes accompanied by a lack of (or barely formal) listening campaign of the demands and priorities of the local communities generated mistrust and the need for emancipation, redemption and resistance [32,59]. The incompleteness of the Bagnoli brownfield regeneration and reconversion process, at the center of the city and national political debate, has generated deep fractures in the civic, democratic, social and economic structure of the area. The progressive impoverishment of the area put young people in the position of leaving or being exposed to social risk factors such as school dropouts, poor employment opportunities and the presence of organized crime in various forms.

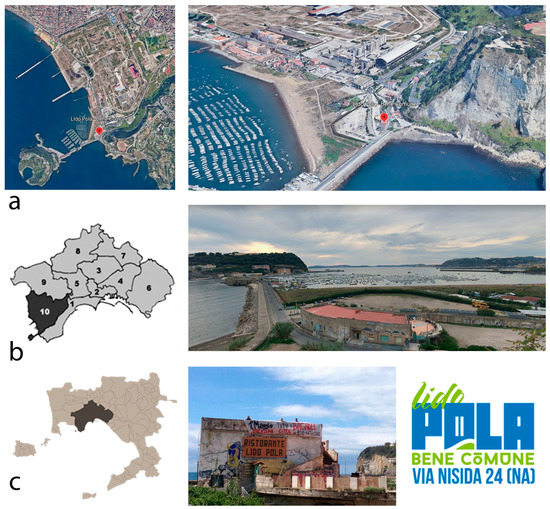

In this framework, the self-established collective Bancarotta 2.0 occupied in May 2013 the Lido Pola building on the Bagnoli waterfront, after more than 20 years of abandonment and progressive degradation. The former restaurant and beach club, active between the 1960s and 1990s, during the period of maximum industrialization of the Flegrean Area (Figure 3), was dilapidated when the community started a process of reappropriation of the abandoned building. The aim of the occupation was to prevent it from being transformed into an affluent tourist location, depriving the local communities of a place for connecting and building capacity, self-awareness and community engagement.

Figure 3.

On the left, the Lido Pola location on the Bagnoli waterfront (a) within the city of Naples (b) and the metropolitan area of Naples (c). On the right, pictures of the Lido Pola building and its surroundings and the visual identity of the commons (source: authors’ elaboration from Google Hearth; Lido Pola Archive).

The original collective evolved into the community of Lido Pola, recognized as an urban common by the city of Naples with Resolution 446/2016, and took on a management and impulse role for local development through asset valorization and territorial animation activities. This formal recognition of the public interest role of community activities within a dilapidated building under the umbrella concept of commons started a unique living laboratory of emancipation and self-organization, thus being designated a district civic facility.

In years of activism, since 2016, the Lido Pola Commons community has developed consolidated experience in activities and processes related to citizen science and the active engagement of citizens in urban transformation processes and environmental issues monitoring (Figure 4). Multiple public science outreach initiatives have been promoted, triggering the debate between researchers and local society on the topics of environmental science, both marine and geological, landscape protection, urban planning, social leadership, waste management, the use of chemicals in agriculture, and many others. The activists of the commons (the commoners), by activating various forms of collaboration with students and professionals from different disciplinary fields, developed several proposals regarding refurbishment and reuse of areas and infrastructures surrounding the main building.

Figure 4.

Some activities developed by the Lido Pola commoners and local communities and demonstrations within the Bagnoli area (source: Lido Pola and Bancarotta 2.0 Archives).

The community also promoted citizen-led environmental monitoring activities, with the aim of implementing a process of collective self-protection involving the inhabitants of the neighborhood.

In line with the activities carried out, the community actively participates in the Popular Observatory for the Reclamation of Bagnoli, a consultative body recognized by the redevelopment public agency Invitalia and engaged in technical analysis and public awareness throughout the process of land reclamation and environmental cleanup in the area.

4.2. The Turning Point: Producing Ecosystemic Urban Commons

The turning point in the Lido Pola Commons experience dates back at the end of 2021, when a researcher in physics (a National Research Council CNR high-level executive and current institute director) shared with the community the dream of establishing a research center on marine sciences and environmental technologies on the seaside, restoring for this purpose the Lido Pola building. With the authors, he proposed to the Lido Pola community a collaboration for the creation of an unusual initiative: apply for funding within the PNRR (National Recovery and Resilience Plan, implementing the Next Generation EU), developing the project of a public–civic lab codesigned experience that would be considered a sui generis urban regeneration process2. The Polo Litoraneo di innovazione per l’Ambiente marino e la Resilienza Sociale—PoLARS project aims to establish an experimental research center in the Lido Pola building. Thus, there are reasons to consider the PoLARS a unique unprecedented experience of partnership between public institutions and urban commons (the whole project’s partners were the institutes IRISS, ISASI, ISMAR, ISPC, INM, INO, and IBBR of the National Research Council (CNR) based in Naples, the university consortium CoNisMA (Science of the Sea), the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV), and the City of Naples; and three social associations—Quadrifoglio Società Cooperativa Sociale, Associazione Caracol and Associazione Jolie Rouge APS, representing the commoners of Lido Pola, and finally the Città della Scienza—Idis Foundation). At the time of writing this article, the project had reached the score for approval, but failed to obtain funding. The PoLARS project, in addition to constituting a scientific research pole, aims to enhance and enrich the abovementioned experience of the commoners of Lido Pola by establishing a constant synergic relationship between them and the researchers from different scientific disciplines, including engineering, architecture, urban planning, economics, marine science and technology, physics, geophysics, volcanology, optics and sensor technology.

The objective pursued is to foster sharing experiences between the research and social actors, in order to put their different skills and knowledge at the service of citizenship, enhancing the collaboration and participation of citizens on environmental issues, public health and the monitoring and management of natural resources, and finally ensuring constant communication and dissemination on a local, metropolitan, regional and national scale.

The initiative is therefore based on the construction of a shared vocabulary that can enable communication and action together. Since October 2021, the PoLARS partners have worked together to prepare the PNRR funding request. The dialogue process, punctuated by interaction events, some internal to the partnership and others open to the local community, began at the stage of building the project team. The sharing of intentions and goals and ways to effectively achieve them was ensured through open and inclusive activities, such as online partnership meetings, interdisciplinary and thematic working groups, survey forms and data collection questionnaires administered online through the city commons network, local community networks and the scientific community.

The collaborative process made use of engagement and co-assessment protocols flowed into the construction of project choices and the identification of social, economic and environmental impacts through the drafting of a cost–benefit analysis based on EU models3.

In the constellation of initiatives generated by the PoLARS intra-action, which can refer to a real process of institutional creativity [60], the experience of Pint of Science Italy 2022 and the launch of a cycle of scientific seminars also fits in. Finally, the community succeeded in obtaining funding within the national competition Creative Living Lab IV Edition, with the submission of another funding application. The project LP2 Lido Pola Permanent Lab” was promoted, this time directly by the community through a social promotion association and with a partnership that retains the majority of the extended community (Lido Pola and CNR researchers). The aims of this project for the most part follow those pursued by PoLARS (i.e., the activation of a participatory planning process for the neighborhood and aimed at urban regeneration initiatives), finally finding concrete implementation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Some activities developed by the Lido Pola commoners together with the researcher group within the project PoLARS, Pint of Science initiative, and LP2 Lido Pola Permanent Lab (source: Ragozino 2022, 2023; Lido Pola archive).

5. Results and Discussion

Prior to the discussion of the evidence, it seems essential to clarify that our idea is not proposing a sort of theoretical hierarchy based on the two models’ interpretative strength. Differences, as known, lie in the ways of classifying crucial commons governance structure and effectiveness. On one side, solutions are in institutional rules produced to overcome resource overuse, while on the other, they (solutions) are declined through adopting a new ecological sensibility, which “simultaneously takes life-engendering entanglements of local and planetary symbiotic mutualism” [1] (p. 39). Accordingly, the major differences between the two theories concerning urban commons governance and the ways of assuming access responsibilities revolve around relational modes.

What emerges from the practical experience, conducted on the relational behavior of a civic community extended by the inclusion of actors/groups pertaining to the world of research (CNR and University), is that different forms of relationality can coexist and play a different role in the construction of urban sustainability, as defined by Hinchliffe and Whatmore in 2017 [22].

From the narrative data reporting the experience of the Lido Pola community and the new experience of “becoming together,” communities (Lido Pola and researchers), through the collaboration activated with the PoLARS Project and then continued (despite the failure of PoLARS funding) with other successful activities and projects, the relational diversity in the ways and results obtained emerges. It will concur, directly or indirectly, to form the governance capacity for urban sustainability.

Confronting the column on the far right dedicated to results in Table 2, there are several elements that can contribute to the construction of a governance for a sustainable city. In particular, among the activities that generate a more aware citizenship about environmental problems and a more inclusive, and therefore closer to an urban sustainability objective, there are the entanglement relations involving the Lido Pola community, the students of the neighborhoods, and the experts, in particular, through the activities carried out together with citizenship (civic desk, self-advocacy/help activities, citizen science or those involving codesign and co-assessment) and in any case reported in lines 1, 3, 4, 7 and 8.

Table 2.

The Lido Pola Commons: relational modes and corresponding results in terms of governance for sustainable city (source: authors’ elaboration).

The intra-action activated between the actors of the project, i.e., between the two communities, that of the scientists and the inhabitants of the Lido Pola Commons, reproduced the aforementioned dynamics of “consensus-based decision-making” (considered entanglements), including the scientific community in the collaborative decision-making process of the commons. The osmosis between social- and hard-science researchers and the community allows a mutual learning process and triggers new opportunities for the valorization of scientific results and knowledge transfer on the one hand and promotes greater social awareness of environmental challenges on the other. In addition, commons activities, which are usually aimed at social inclusion and the monitoring of problems affecting the area, will be enriched in the dialogue with researchers.

The centrality of citizenship in the production and dissemination of expert knowledge becomes the keystone in the formulation of strategic choices for territorial development and in restoring (or generating from the ground up) a constructive dialogue between institutions and territorial communities. The experiments conducted in this “presidium” of open access knowledge will contribute to the formation and transfer of knowledge and capacity building, both with reference to the productive world (patents and start-ups of local initiative) and to the construction of conscious choices by communities (smart communities, energy communities, participatory decision-making processes).

No less important, insofar as they are oriented towards achieving inclusion objectives, are the activities carried out through the formal collaborative relations between the community and the administration, which take the form of maintaining dialogue between the two poles. The numerous meetings between delegated groups of the two parties, as well as the exchange of emails and telephone calls make up the “red line” of this interaction (see lines 2, 5 and 6).

Finally, an interesting implication concerns relational modes and policy design in the urban commons field. As seen, social relationships, under the finite cover of bonding and bridging modes, can be easily recognized and thus regulated, while relationship as entanglement escapes by its nature the same possibility. Thus, it can be included among the indirect policy tools.

At the same time, as emerged from the empirical analysis, it is the relationship through entanglement (intra-actioning) of the most crucial relational mode in guarantee social inclusion and appreciable results. These are expressed in terms of allowing the commons to have a durable life and in also achieving public funding.

6. Conclusions and Follow-Up

This article is a research contribution to the nature of inter- and intra-actioning commons relationships. The main evidence has been presented by a picture of the preconditions for sustainable commons governance, along with the ways that urban social inter- or intra-actioning (i.e., respectively bonding, bridging, and entangling) contribute to it.

Acknowledging the research gap in terms of the lack of methodologies for interpreting urban commons performative issues and implications, we have reconsidered the migration of the commons concept from the natural to the urban context. Starting from the Ostrom-led theoretical framework, the successful experiences developed within the natural environment are less convincing if applied in an urban environment. Foster’s application of Ostrom’s theory encourages an interpretation of urban zoning and spatial planning as a system of rules for institutionalizing the commons [61]. This approach, ruled by the need for institutionalization, has been challenged by the practices developed in different areas as well as by the debate developed in different social arenas [62]. More widely, the taken-for-granted ontological divide between subjects–objects, humans–nonhumans, resources–extractors, and commoners–commons remained substantially unquestioned within the specific commons literature.

In this field, the relationship variable and the ways in which it is managed is explicative. Between the two frameworks, there are the emerging interpretative keys for understanding (and capturing) social relationships. The modes of bonding, bridging (more in the Ostrom–Foster vein), and entangling (from the B-M-L approach), all concur, also if differently, as part of a single evolutionary path towards a common outcome of urban sustainability, opening to informality.

The resulting combined theoretical setting has been tested within the Lido Pola Commons, already included in an action-research process developed by the authors with a network of researchers, social enterprises, associations and institutions, with the aim of promoting sustainable and inclusive urban regeneration in the area. The codesign experience [63,64] the commoners are developing with researchers, communities and institutional players outlines an interesting arena for observation and fieldwork. By stepping aside and observing this practice, we considered it the best option to test the theoretical setting. Not only does the Lido Pola community meets the case selection criteria, but the turning point outlined in Section 4.2 offers useful insight into multidimensional and multilevel relationships.

The testing phase confirmed the rationale for the novel theoretical setting and encouraged us to step ahead in two intertwined directions. At the conceptual level, future development of the work could study the time variable in analyzing urban commons performative implications, by including the phenomenology of intersubjectivity in order to develop an interpretation of multifaceted relationships developed within each commons expression. In this analytical setting, the discourse could imply the diffraction from new M–B–L materialism to Levinas alterity [65]. The latter, following the main self-recognition issue, can give an interesting addition to the analytical tool set “phenomenology of intersubjectivity”.

The main follow-up regards policy design implications about relational differences and their contribution to create urban sustainable-inclusive contexts. More than further discussing the regulatory slippage, it could be fruitful to address the issue of abandonment of public spaces and buildings. In these contexts, where the free-riding threat can be avoided, it is possible to exploit the inner sense of collectivity and the need for regeneration and accessible public spaces as part of the classic omnia sunt communia idea in our cities. The circular research process, in which theories and practices trigger mutual learning, encompasses the themes of social cohesion, urban regeneration, informal economics and the redefinition of the boundaries of public realm.

The next step of the research process is to further explore the relationships among internal and external agents in order to overcome the conflicting dualities of commoner–institution and informality–regulation, in order to seek an adaptive commons governance model.

A deep understanding of the commons’ relational modes under the pressure of an urban transformative process can be the turning point for experimenting with a “dynamic institutionalization” in defining the governance model of these complex and vibrant entities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.V. and G.E.D.V.; data curation, S.R.; investigation, M.P.V., S.R. and G.E.D.V.; methodology, M.P.V., G.E.D.V. and S.R.; resources, S.R.; validation, M.P.V., S.R. and G.E.D.V.; visualization, S.R.; writing—original draft, M.P.V. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, G.E.D.V., M.P.V. and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research process presented in this paper—although not directly funded—has been developed within two projects included in the institutional programming of CNR IRISS: the project “An innovative place-based regeneration approach to balance marginalization and anthropogenic pressure” coordinated by Gabriella Esposito De Vita and its subproject “Place-based approaches to rebalancing anthropogenic pressures on the consolidated city” coordinated by Stefania Ragozino, as well as the project “The Economy of Commons and Collaborative Communities: For an Observatory on Urban Commons” coordinated by M. Patrizia Vittoria. Livia Russo participates in these research activities The authors would like to thank Ivo Rendina, director of the CNR ISASI and promoter of PoLARS, and all the partners in the project consortium for the extensive and fruitful interdisciplinary exchange carried out in the project. Finally, the authors are grateful to the Lido Pola community from which started the idea of “another” kind of relationality carried on within the urban Commons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The Permanent Citizen Observatory of the Commons of the City of Naples is a participatory consultative body, appointed by the Mayor through a public notice aimed at involving people who are competent but also personally active in participatory processes and the commons in Naples and beyond (Available online: https://commonsnapoli.org/en/new-institutions/citizen-observatory/, accessed on 15 January 2023). For more details on the political-institutional nature of the Observatory, see [56]. |

| 2 | This experience is part of a collaborative process that partly led to participation in the Expression of Interest “Ecosystems of Innovation in Southern Italy” (Cohesion Agency, Public Notice—Decree 204/2021). |

| 3 | Available online: https://space-economy.esa.int/article/84/a-closer-look-at-the-european-commissions-guide-to-cost-benefit-analysis-of-investment-projects, accessed on 30 December 2022. |

References

- Metzger, J. The city is not a Menschenpark: Rethinking the tragedy of the urban commons beyond the human/non-human divide. In Urban Commons: Rethinking the City; Borch, C., Kornberger, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 32–56. ISBN 1315780593. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. An Inquiry into Modes of Existence; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 0674728556. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, K. Quantum entanglements and hauntological relations of inheritance: Dis/continuities, spacetime enfoldings, and justice-to-come. Derrida Today 2010, 3, 240–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, K. Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2003, 28, 801–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, K. Nature’s queer performativity. Qui Parle Crit. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 19, 121–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons. The Evolutions of Institutions for Collective Actions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, C.; Ostrom, E. A framework for analyzing the knowledge commons. In Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 41–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; ISBN 0631140484. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The future of the commons. Radic. Hist. Rev. 2011, 109, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 1844678822. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, N.M.; Infranca, J.J. The sharing economy as an urban phenomenon. Yale Law Policy Rev. 2016, 34, 215–279. [Google Scholar]

- Finck, M.; Ranchordás, S. Sharing and the City. Vanderbilt J. Transnatl. Law 2016, 49, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillgren, P.-A.; Seravalli, A.; Agger Eriksen, M. Counter-hegemonic practices; dynamic interplay between agonism, commoning and strategic design. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2016, 9, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. Ostrom in the city: Design principles and practices for the urban commons. In Routledge Handbook of the Study of the Commons; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 235–255. ISBN 1315162784. [Google Scholar]

- Huron, A. Working with strangers in saturated space: Reclaiming and maintaining the urban commons. Antipode 2015, 47, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borch, C.; Kornberger, M. Urban Commons. Rethinking the City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, F.; Gaugliz, C. Make_Shift City: Renegotiating the Urban Commons; Jovis Publisher: Berlin, Germany, 2014; ISBN 3868592237. [Google Scholar]

- Dellenbaugh, M.; Kip, M.; Bieniok, M.; Müller, A.K.; Schwegmann, M. Urban Commons: Moving beyond State and Market; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 154, ISBN 3038214957. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, T.; Rossi, U. Ambivalence of the urban commons. In The Routledge Handbook on Spaces of Urban Politics; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 35–46. ISBN 1315712466. [Google Scholar]

- Kornberger, M.; Borch, C. Introduction: Urban commons. In Urban Commons: Rethinking the City; Borch, C., Kornberger, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 11–31. ISBN 1315780593. [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe, S.; Whatmore, S. Living cities: Towards a politics of conviviality. In Environment: Critical Essay in Human Geography; Anderson, K., Braun, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 555–570. ISBN 1315256355. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, R. The spatialized political ecology of the city: Situated peripheries and the capitalocenic limits of urban affairs. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 42, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0674012895. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Où atterrir?: Comment s’ Orienter en Politique [Where to Land: How to Find Your Way in Politics]; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 2707197815. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone, C.; Marchigiani, E.; Esposito De Vita, G.; Rossi, M. ‘Terrestrial’. La sfida del gioco a tre [The challenge of the three-way game]. Contesti 2021, 1, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, J.; Stoermer, E.F. Global Change Newsletter. Glob. Chang. Newsl. 2018, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, A.; Ghorbani, A.; Herder, P.M. Commoning toward urban resilience: The role of trust, social cohesion, and involvement in a simulated urban commons setting. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 45, 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broto, V.C.; Ortiz, C.; Lipietz, B.; Osuteye, E.; Johnson, C.; Kombe, W.; Mtwangi-Limbumba, T.; Macías, J.C.; Desmaison, B.; Hadny, A. Co-production outcomes for urban equality: Learning from different trajectories of citizens’ involvement in urban change. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German EU Presidency. Territorial Agenda 2030 “A Future for All Places”. 2020. Available online: https://territorialagenda.eu/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Oppido, S.; Ragozino, S.; Micheletti, S.; Esposito De Vita, G. Sharing responsibilities to regenerate publicness and cultural values of marginalised landscapes: Case of Alta Irpinia, Italy. Urbani Izziv 2018, 29, 125–142. Available online: ttps://www.jstor.org/stable/26516366 (accessed on 20 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ragozino, S.; Varriale, A. ‘The City Decides!’ Political Standstill and Social Movements in Post-Industrial Naples. In Public Space Unbound. Urban Emancipation and the Post-Political Condition; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito De Vita, G. How to Reclaim Mafia-Controlled Territory? An Emancipatory Experience in Southern Italy. In Public Space Unbound. Urban Emancipation and the Post-Political Condition; Knierbein, S., Viderman, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vittoria, M.P. Commons and Cities. Which analytical tools to assess the Commons’ contribution to the economic life of the cities? In New Metropolitan Perspectives: Local Knowledge and Innovation Dynamics towards Territory Attractiveness through the Implementation of Horizon/E2020/Agenda2030–Volume 1; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Bevilacqua, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 599–605. [Google Scholar]

- Vittoria, M.P. How much is Community Action Worth to the Local Economy? The Debate between «Instincts and Institutions» in the Process of Formation and Consolidation of Urban Commons in Naples. Riv. Econ. Mezzog. 2020, 34, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito De Vita, G.; Ragozino, S. Civic activation, vulnerable subjects and public space: The case of the park of Rione Traiano in Naples. TRIA Territ. Ric. Insediamenti Ambient. Riv. Internazionale Cult. Urban. 2013, 10, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito De Vita, G.; Trillo, C.; Martinez-Perez, A. Community planning and urban design in contested places. Some insights from Belfast. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlock, A.D. Toward a Revised Theory of Zoning. L. Use Control. Annu. 1972, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen, B.C. Zoning: A reply to the critics. J. L. Use Envtl. L. 1994, 10, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Webster, C. Enclosure of the urban commons. GeoJournal 2006, 66, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydin, Y.; Beauregard, R.; Cremaschi, M.; Lieto, L. Regulation and Planning: Practices, Institutions, Agency; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 1000450627. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F. Conceptualising social impacts. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Daldanise, G.; La Rocca, L.; Panaro, S. Triggering Active Communities for Cultural Creative Cities: The “Hack the City” Play ReCH Mission in the Salerno Historic Centre (Italy). Sustainability 2021, 13, 11877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauppenlehner-Kloyber, E.; Penker, M. Between participation and collective action—From occasional liaisons towards long-term co-management for urban resilience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, C. Mapping the new commons. SSRN e-Library 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R. Collective action and the urban commons. Notre Dame Law Rev. 2011, 87, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, P.; Johansson, M. The uses and abuses of Elinor Ostrom’s concept of commons in urban theorizing. In Proceedings of the European Urban Research Association EURA “Cities without Limits”, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–25 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, L. Urbanism as a Way of Life. Am. J. Sociol. 1938, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. The metropolis and mental life. In On Individuality and Social Forms; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971; pp. 324–339. [Google Scholar]

- Susser, I.; Tonnelat, S. Transformative cities: The three urban commons. Focaal 2013, 2013, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerram, L. The false promise of the commons: Historical fantasies, sexuality and the ‘really-existing’ urban common of modernity. In Urban Commons: Rethinking the City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 57–77. ISBN 1315780593. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Anthropology at the time of the Anthropocene: A personal view of what is to be studied. In The Anthropology of Sustainability; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, C.T.; Rothstein, A. Conflict and Consensus; Food Not Bombs Publishing: Takoma Bay, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tecchio, R. Il metodo del consenso: Un metodo decisionale morbido per gruppi forti [The consensus method: Soft decision-making for strong groups]. In La Rete di Lilliput. Alleanze, Obiettivi, Strategie; Emi: Bologna, Italy, 2001; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micciarelli, G. Hacking the legal. The commons between the governance paradigm and inspiration drawn from the “living history” of collective land use. In Post-Growth Planning: Cities Beyond the Market Economy; Savini, F., Ferreira, A., von Schönfeld, K.C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saija, L. La Ricerca-Azione in Pianificazione Territoriale e Urbanistica [Research-Action in Spatial and Urban Planning]; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9788891710734. [Google Scholar]

- Gaber, J.; Gaber, S.L. Utilizing mixed-method research designs in planning: The case of 14th Street, New York City. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1997, 17, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragozino, S.; Varriale, A.; Esposito De Vita, G. Self-organized practices for complex urban transformation. The case of Bagnoli in Naples, Italy. Tracce Urbane Riv. Ital. Transdiscipl. Stud. Urbani 2018, 3, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.; Recano, L.; Rossi, U. New institutions and the politics of the interstices. Experimenting with a face-to-face democracy in Naples. Urban Stud. 2022, 0, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashwan, P.; Mudaliar, P.; Foster, S.R.; Clement, F. Reimagining and governing the commons in an unequal world: A critical engagement. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seravalli, A.; Hillgren, P.-A.; Agger-Eriksen, M. Co-designing collaborative forms for urban commons: Using the notions of commoning and agonism to navigate the practicalities and political aspects of collaboration. In Proceedings of the The City as a Commons: Reconceiving Urban Space, Common Goods and City Governance, 1st Thematic IASC Conference on Urban Commons, Bologna, Italy, 6–7 November 2015; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bason, C. Discovering Co-Production by Design. In Public and Collaborative: Exploring the Intersection of Design, Social Innovation and Public Policy; DESIS Network Press: Milan, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, P.; Schmidt, S. Enabling urban commons. CoDesign 2017, 13, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinas, E. La signification et le sens. Rev. Métaphysique Morale 1964, 69, 125–156. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).