Are Local Residents Benefiting from the Latest Urbanization Dynamic in China? China’s Characteristic Town Strategy from a Resident Perspective: Evidence from Two Cases in Hangzhou

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CT Development: Key Texts and Literature

3. Methodology

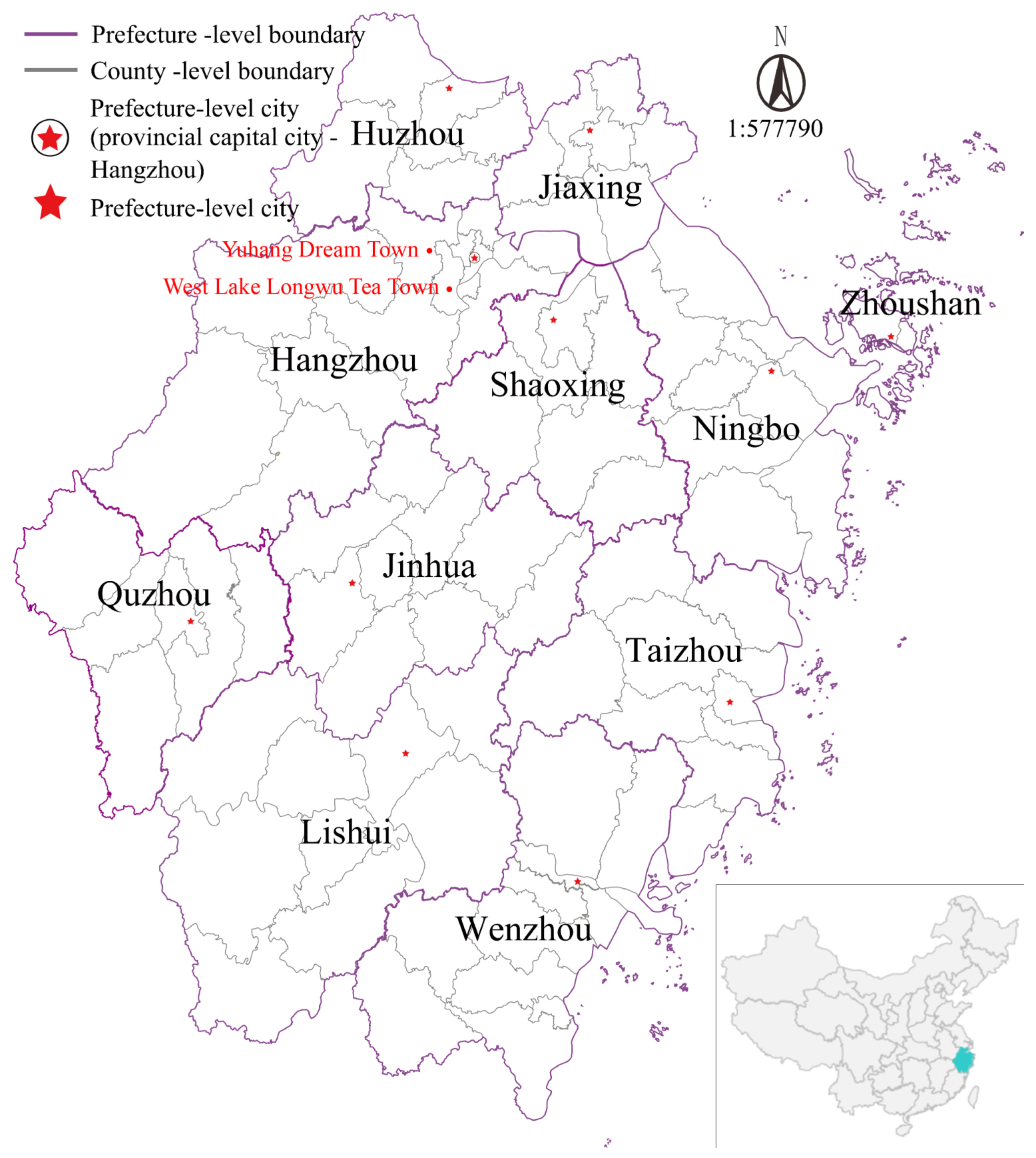

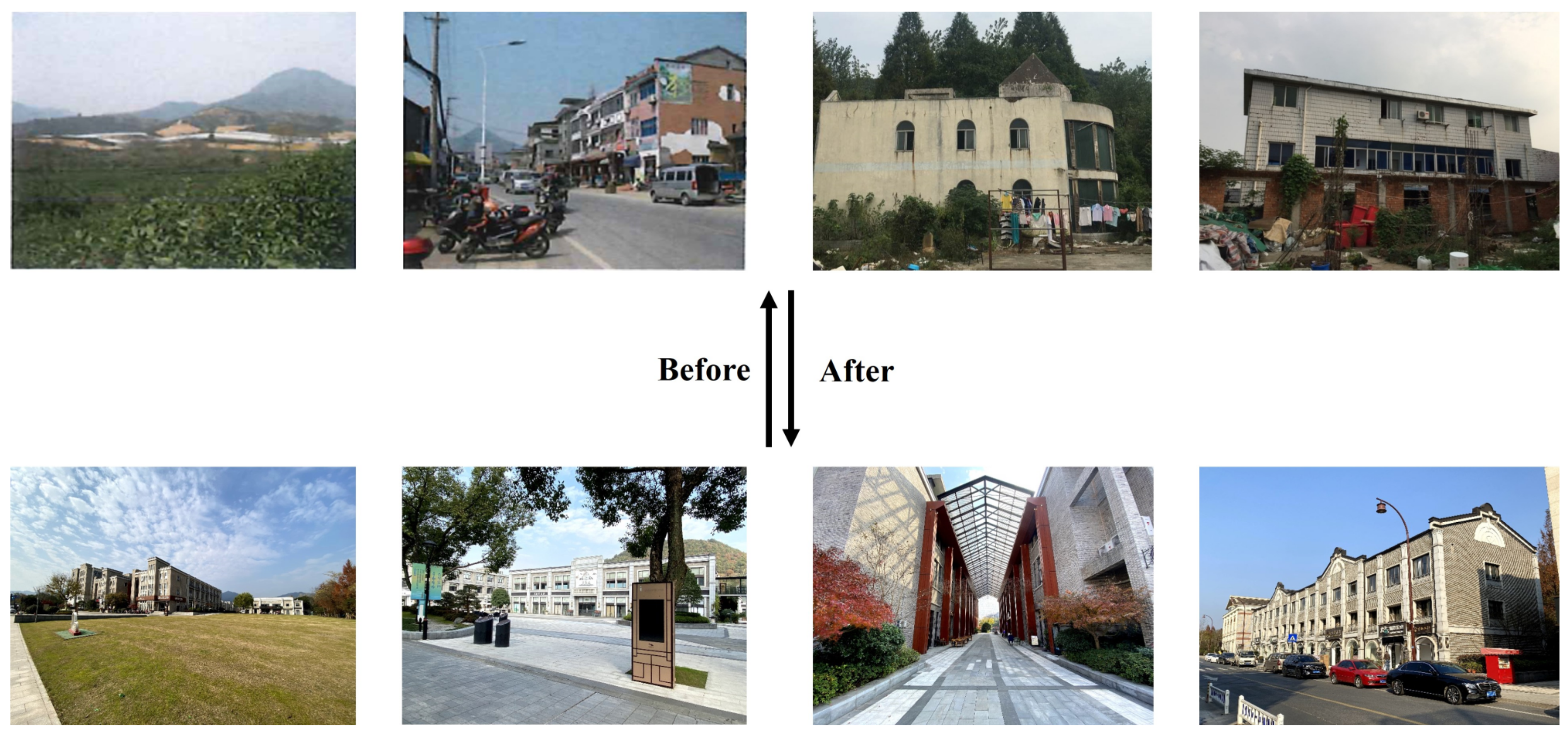

3.1. Research Case

3.2. Data Source and Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

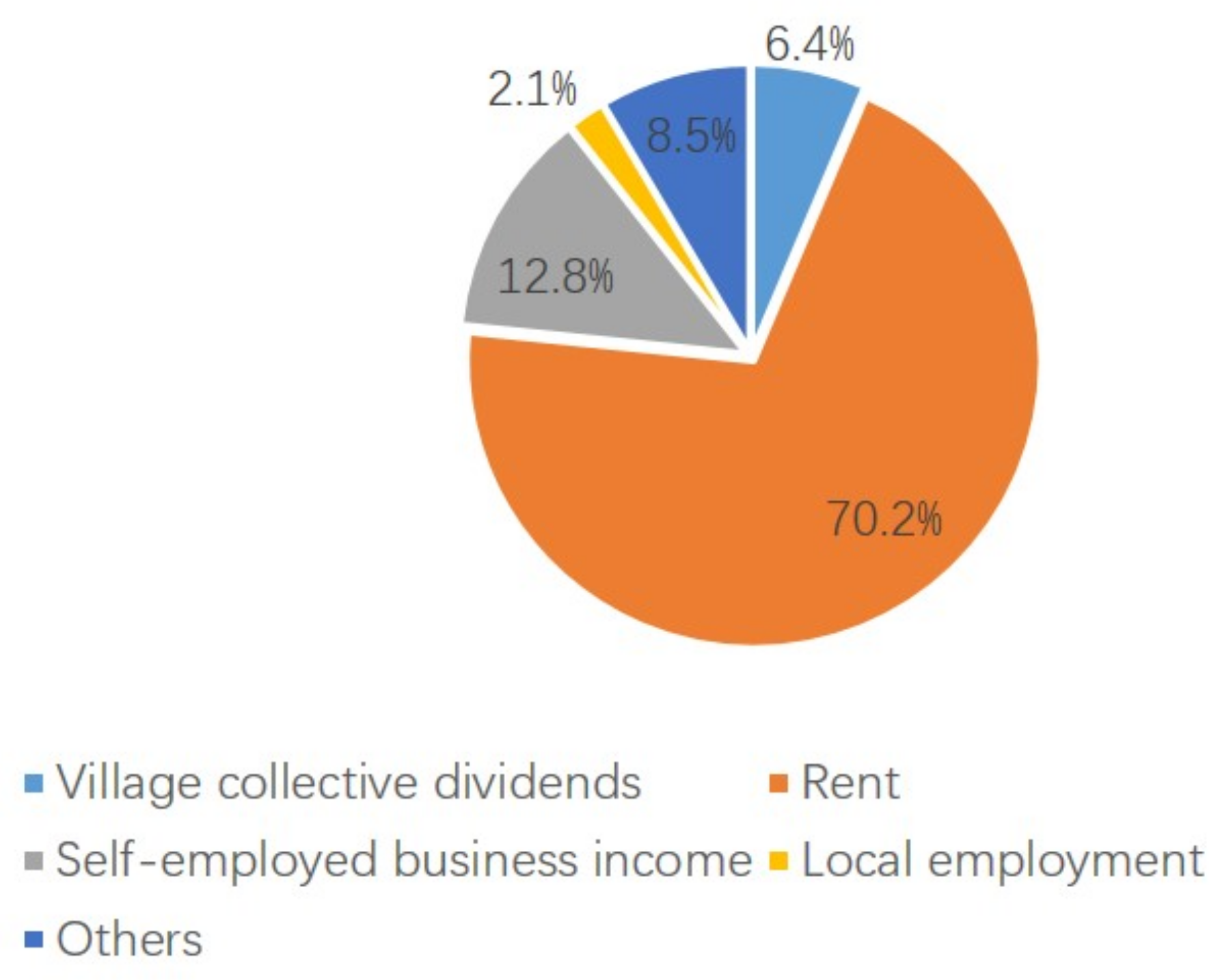

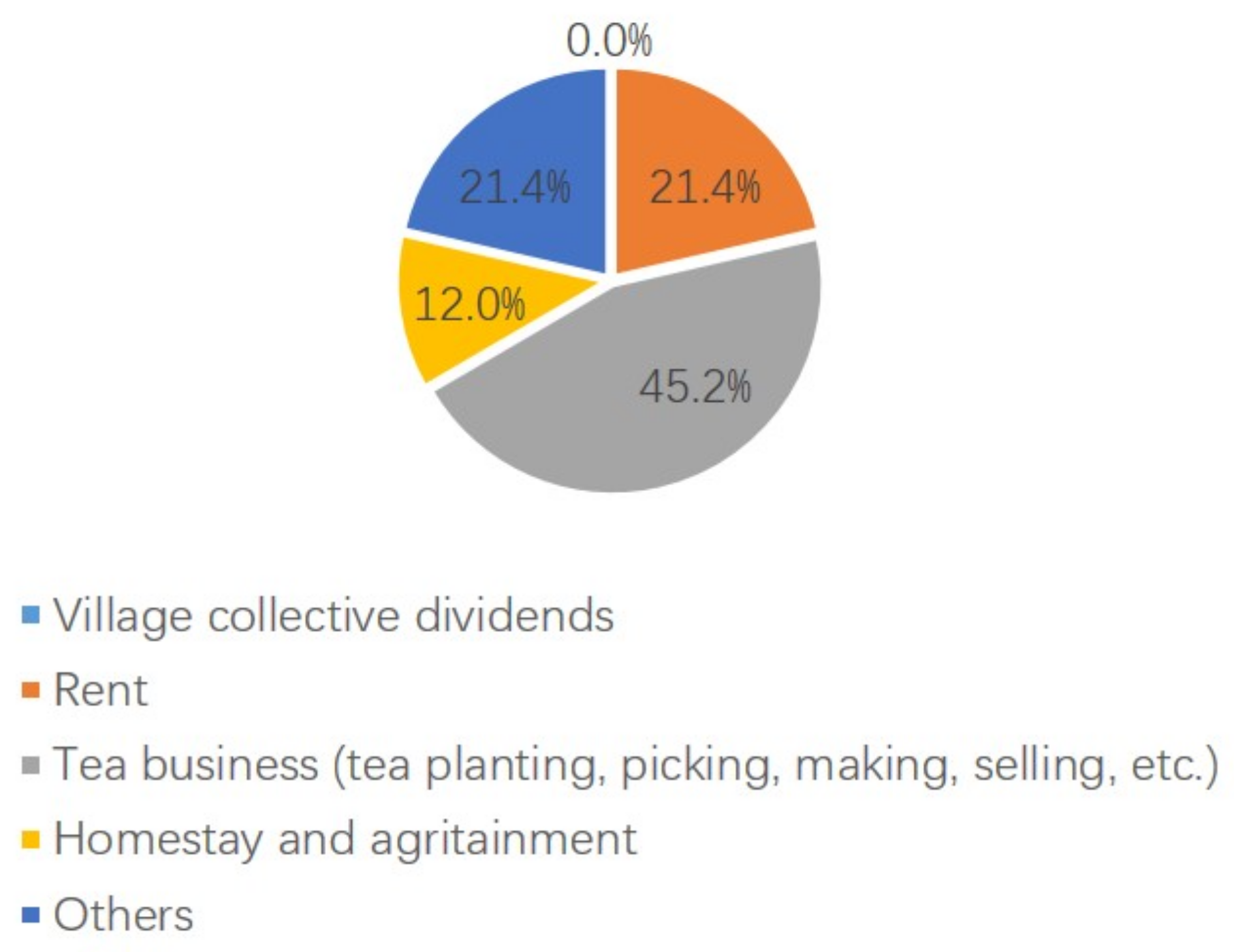

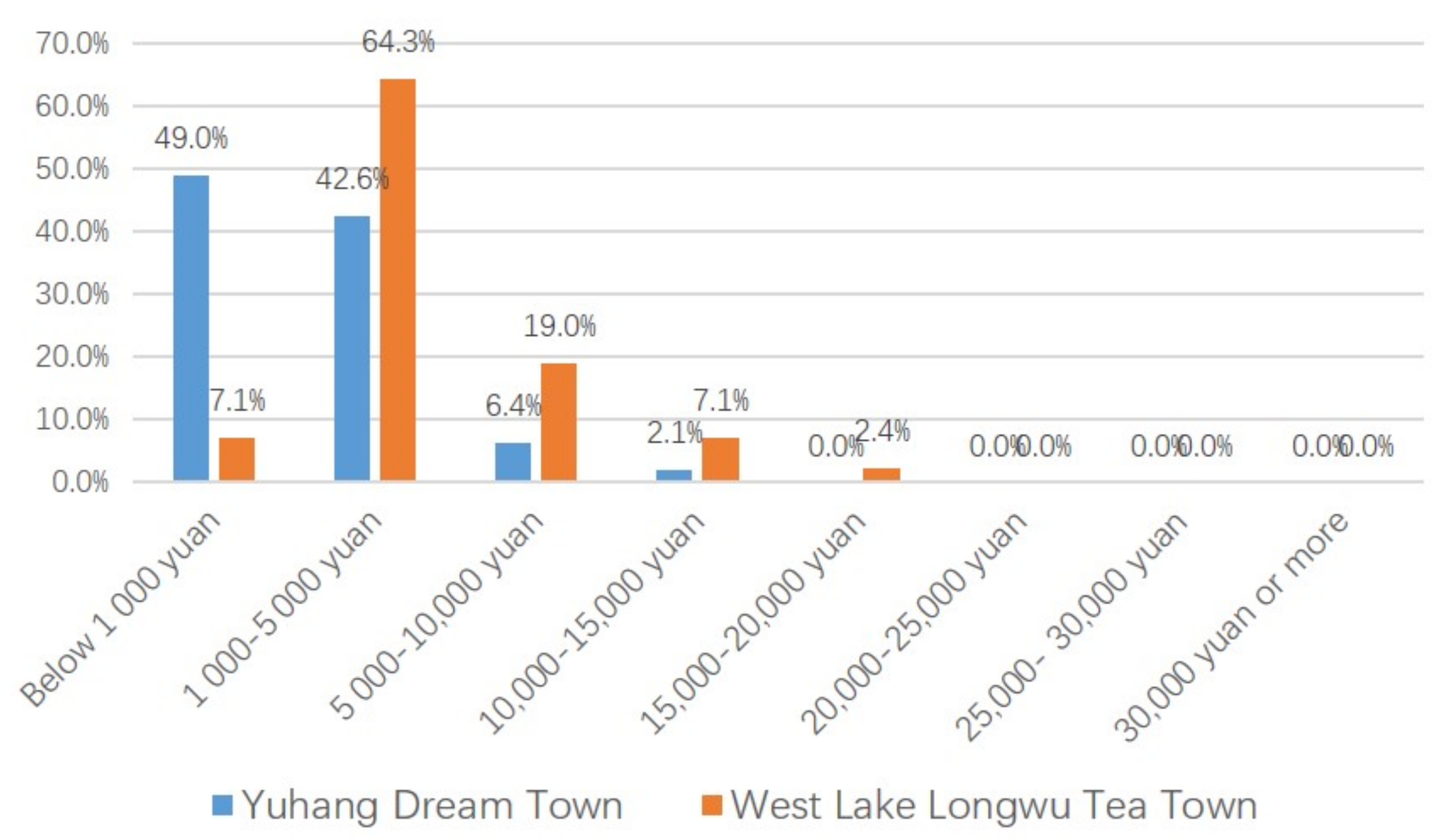

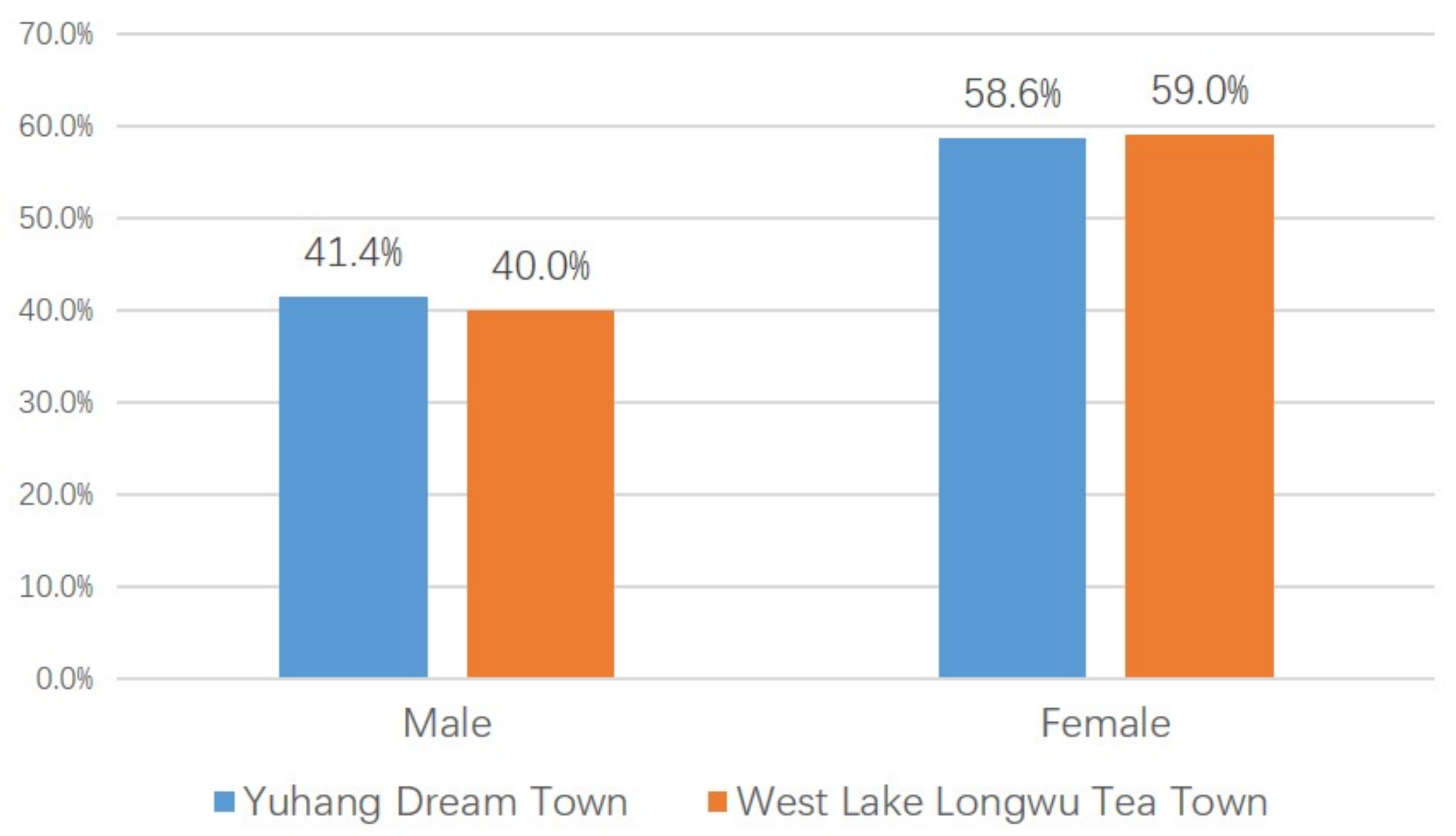

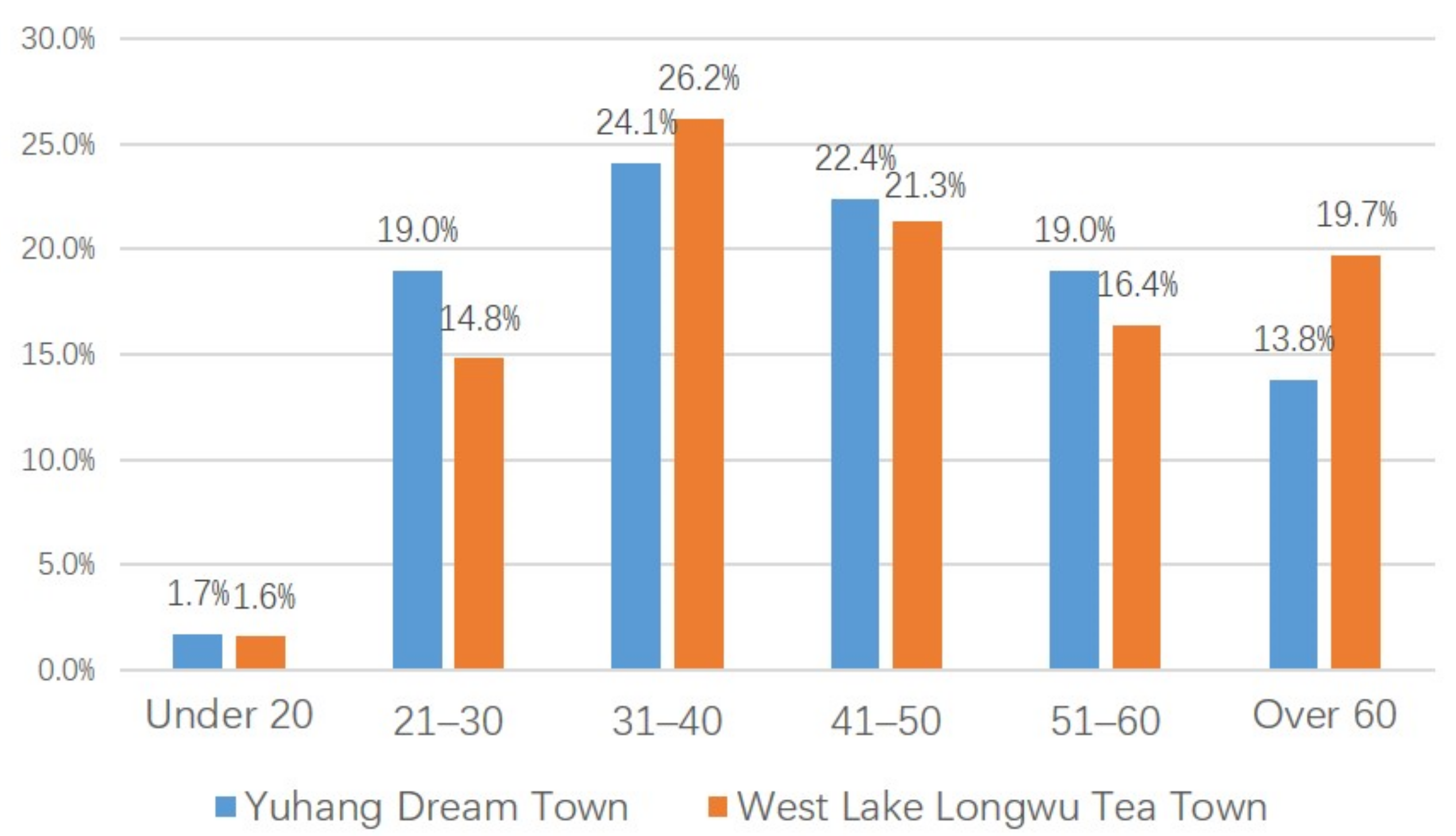

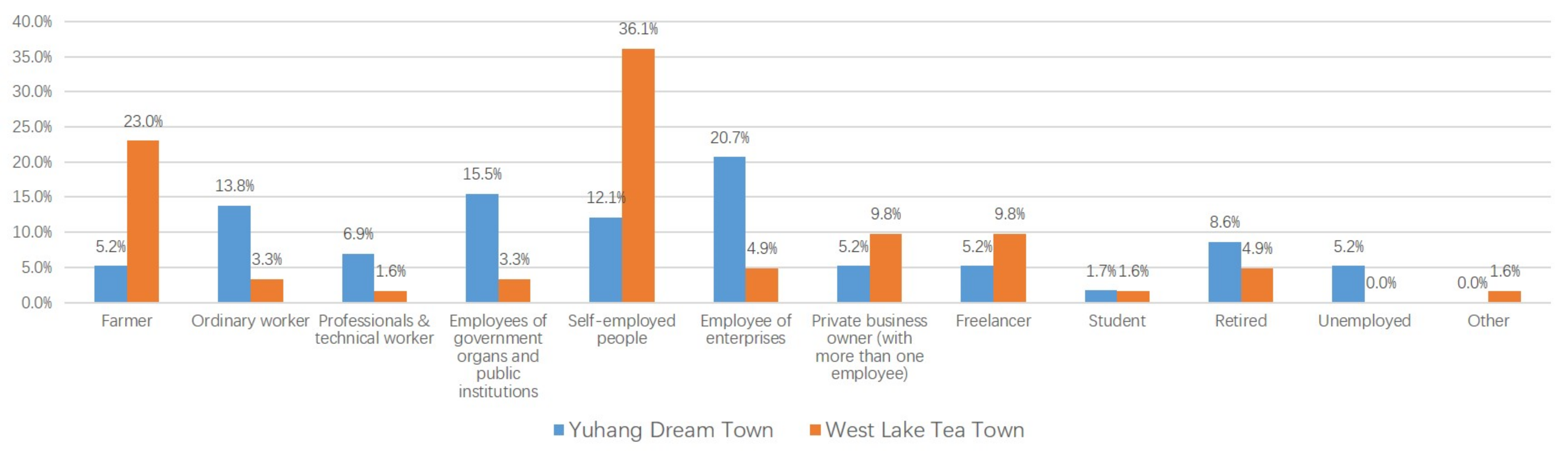

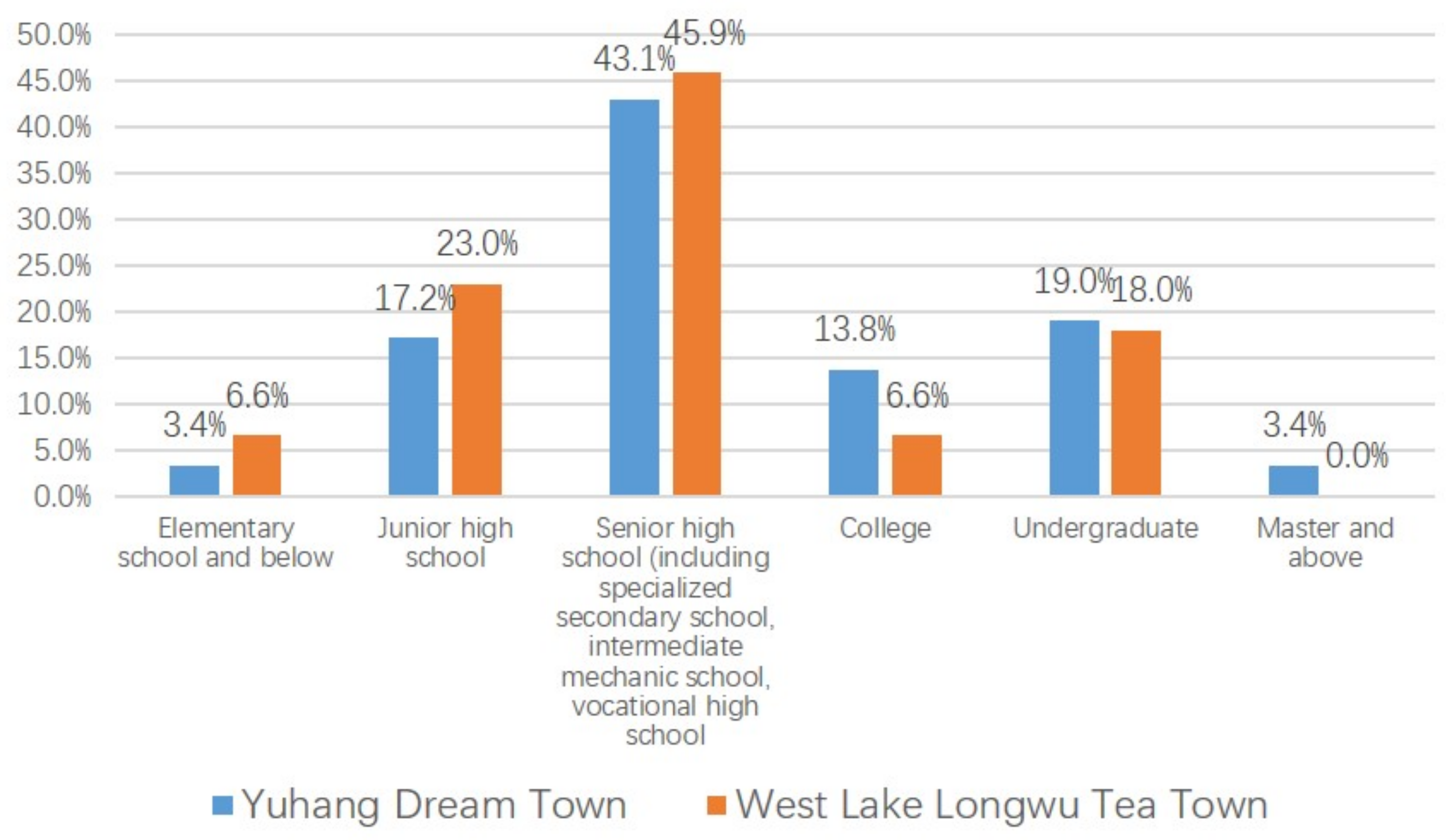

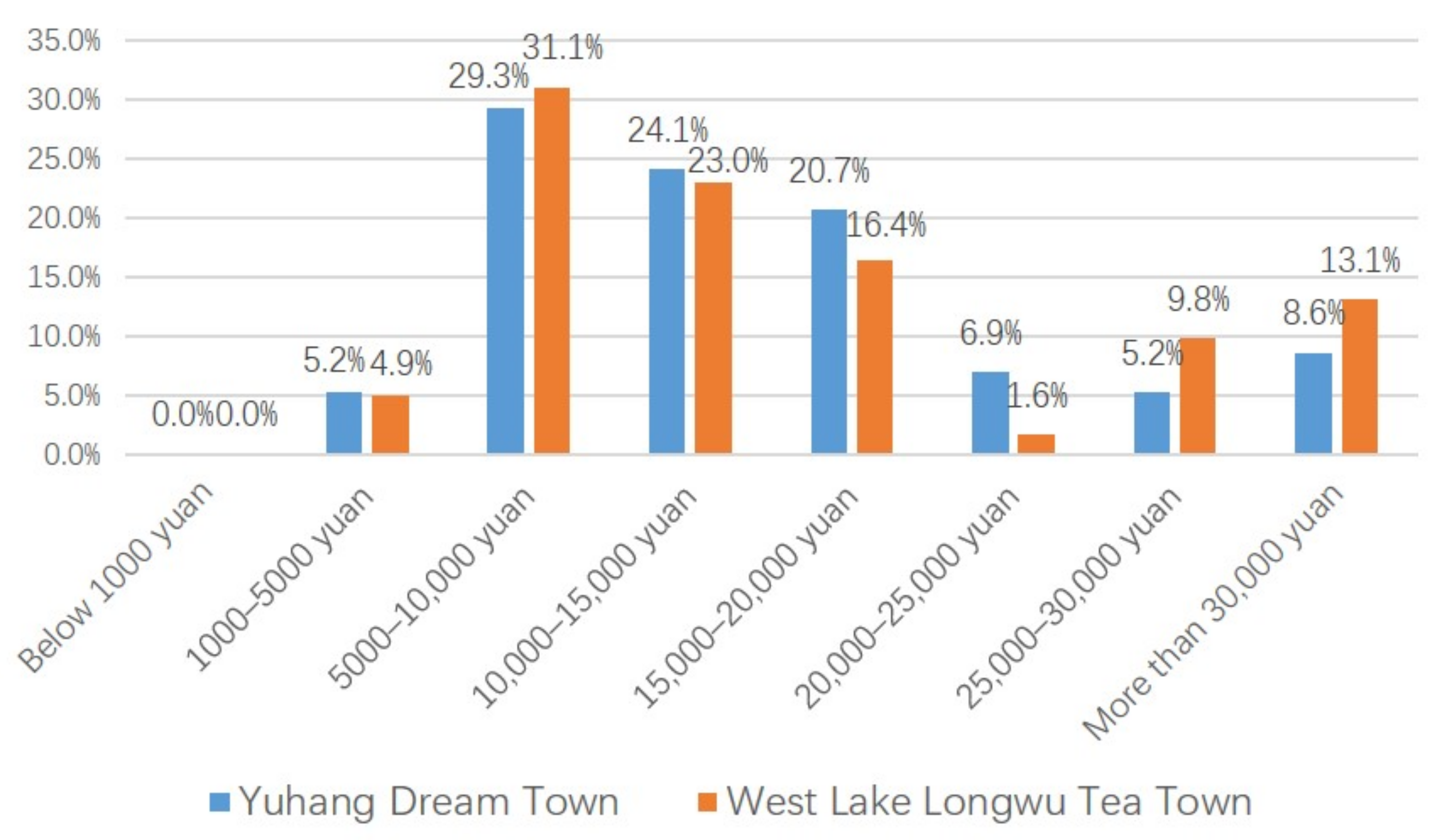

4.1. Basic Socio-Economic Characteristics

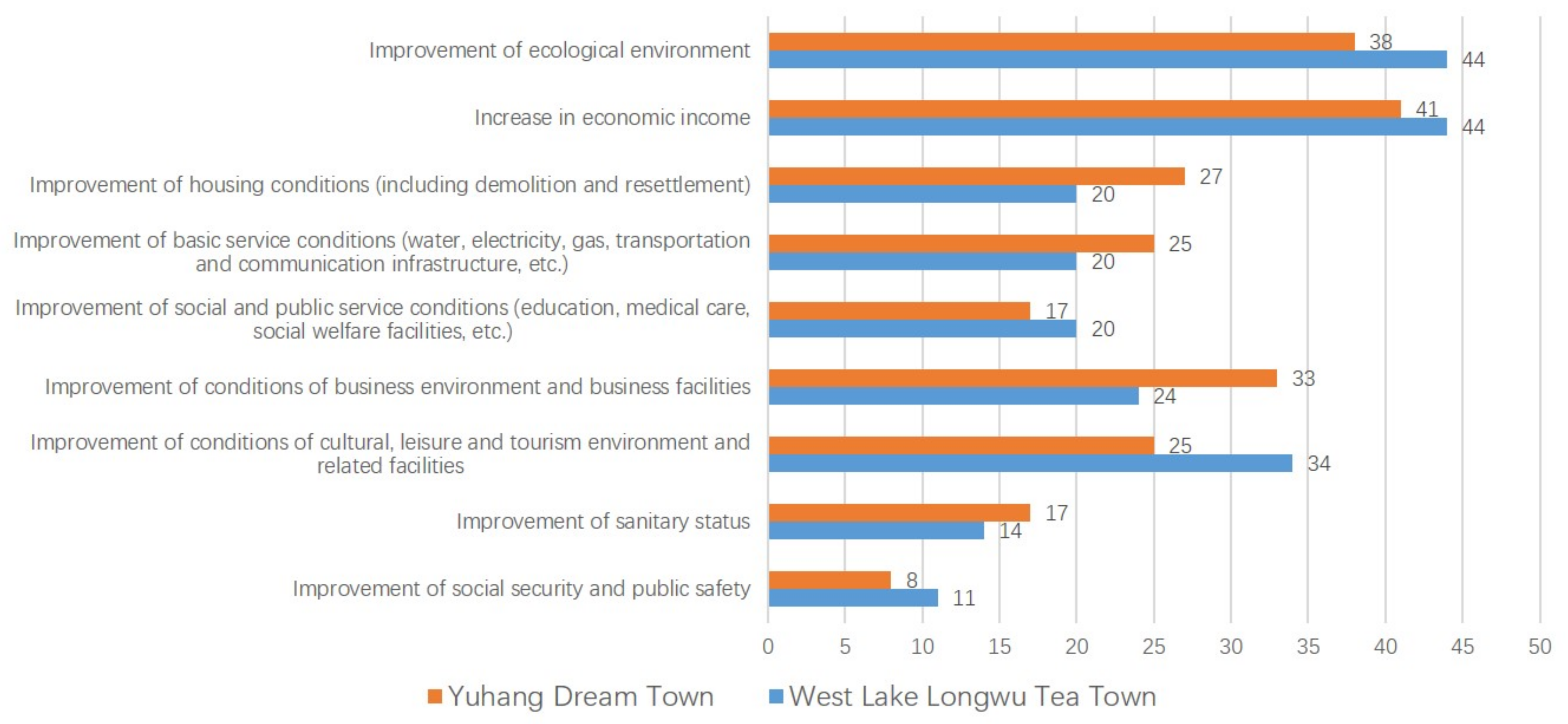

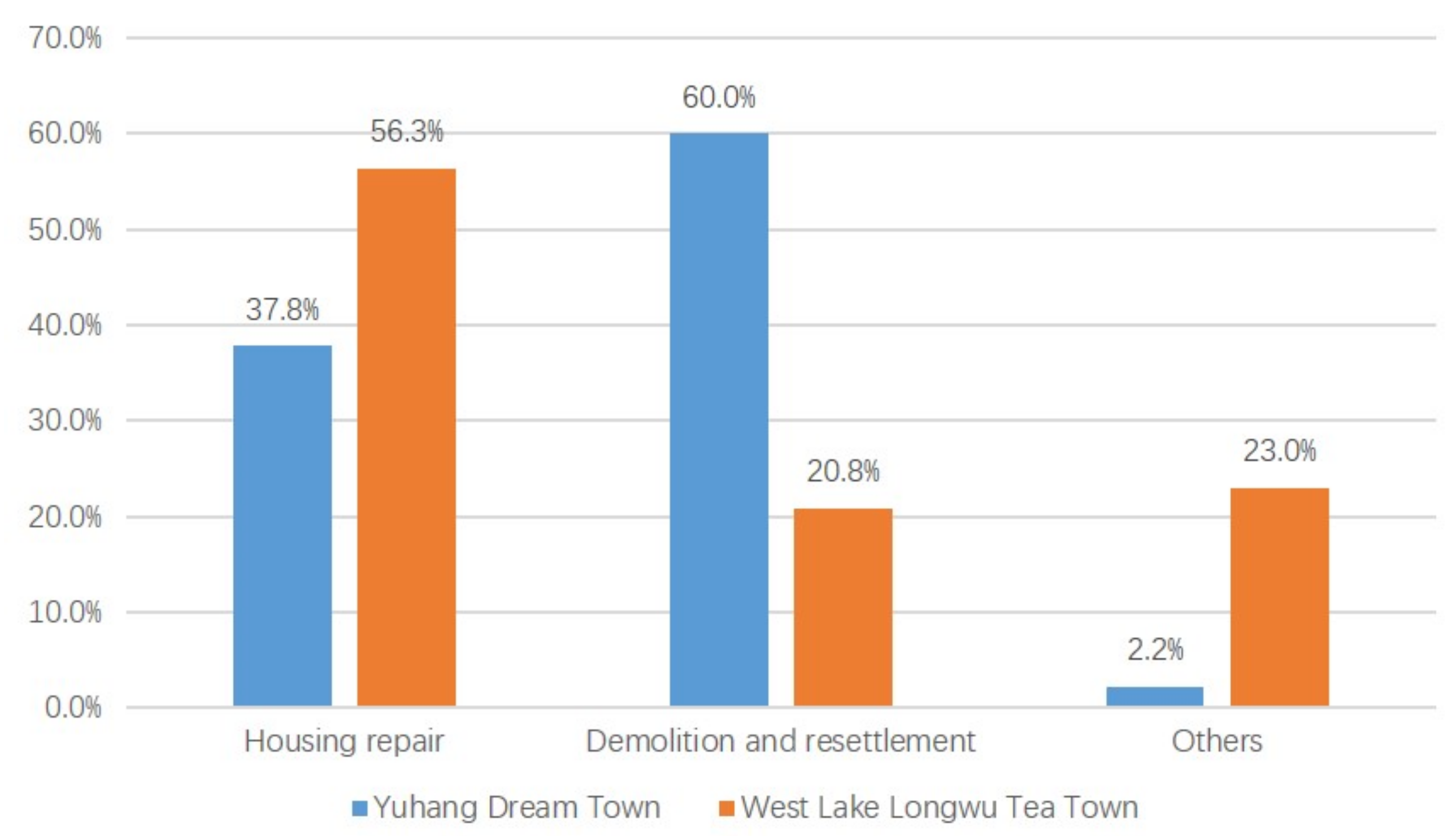

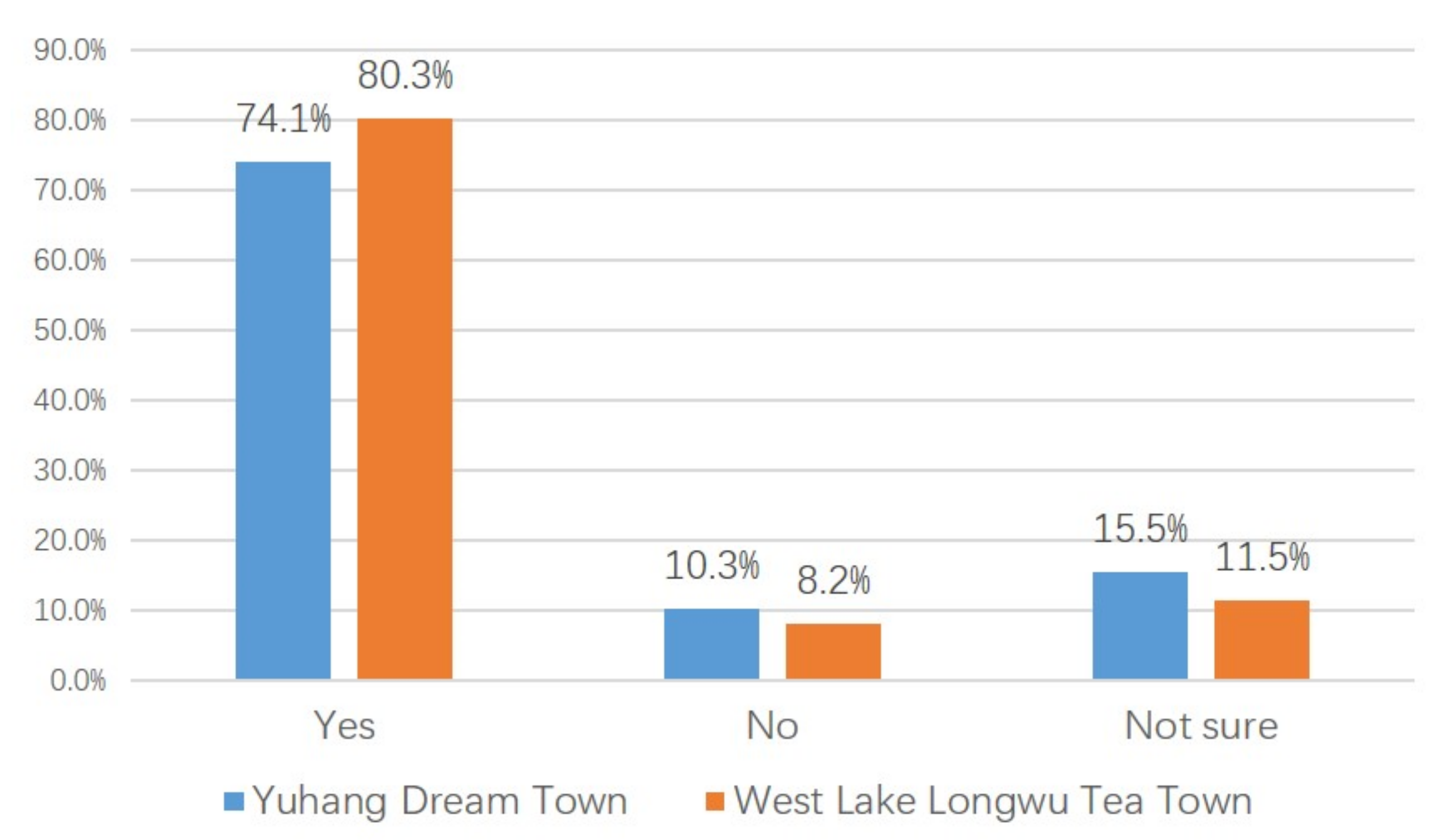

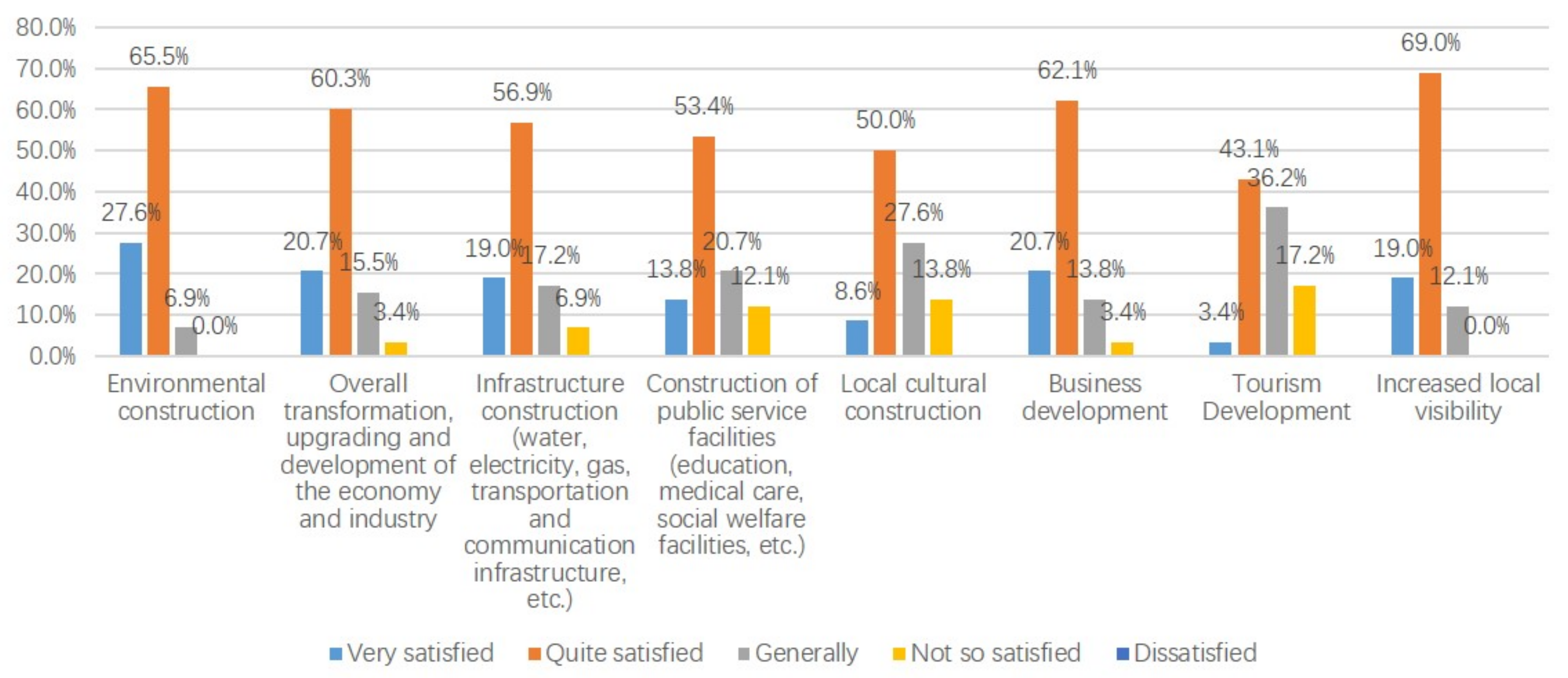

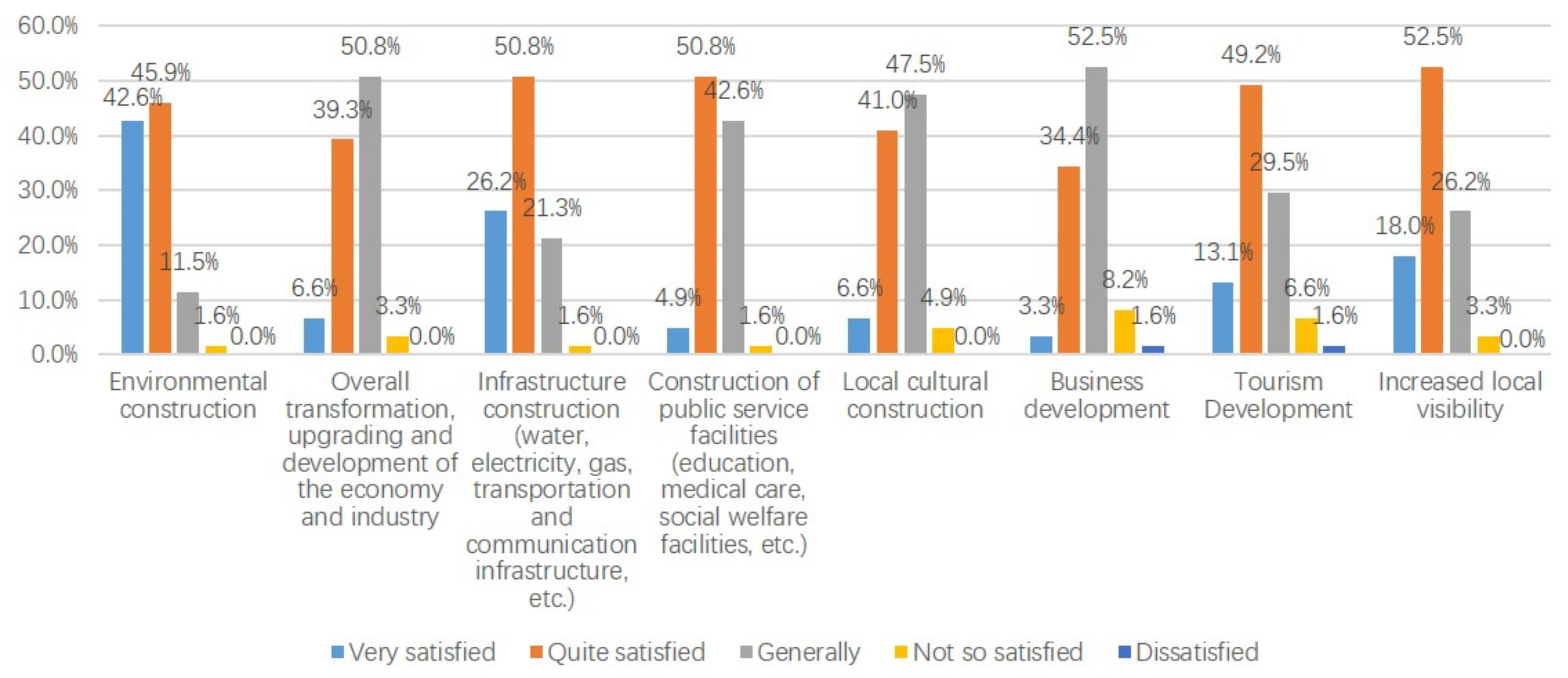

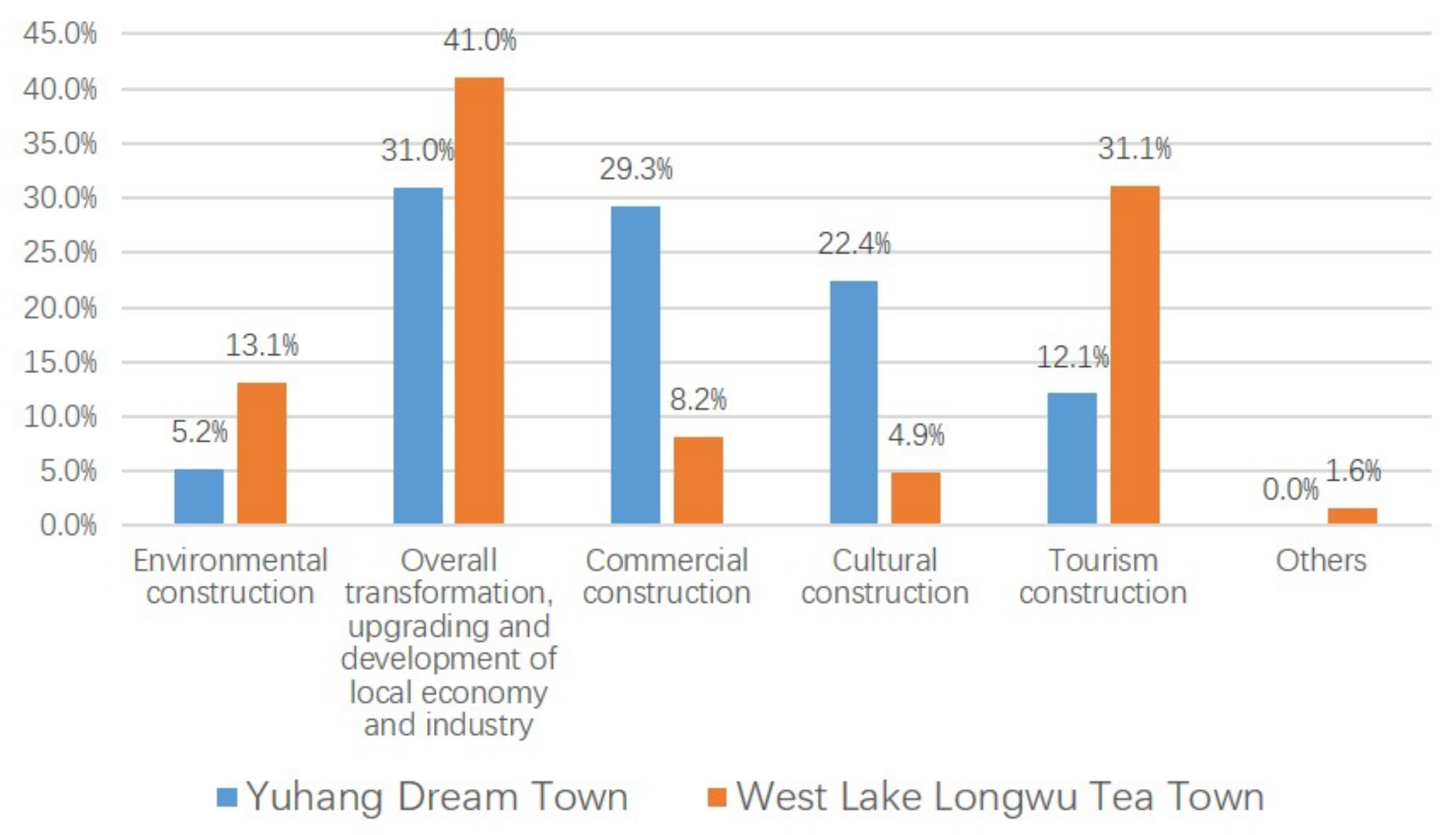

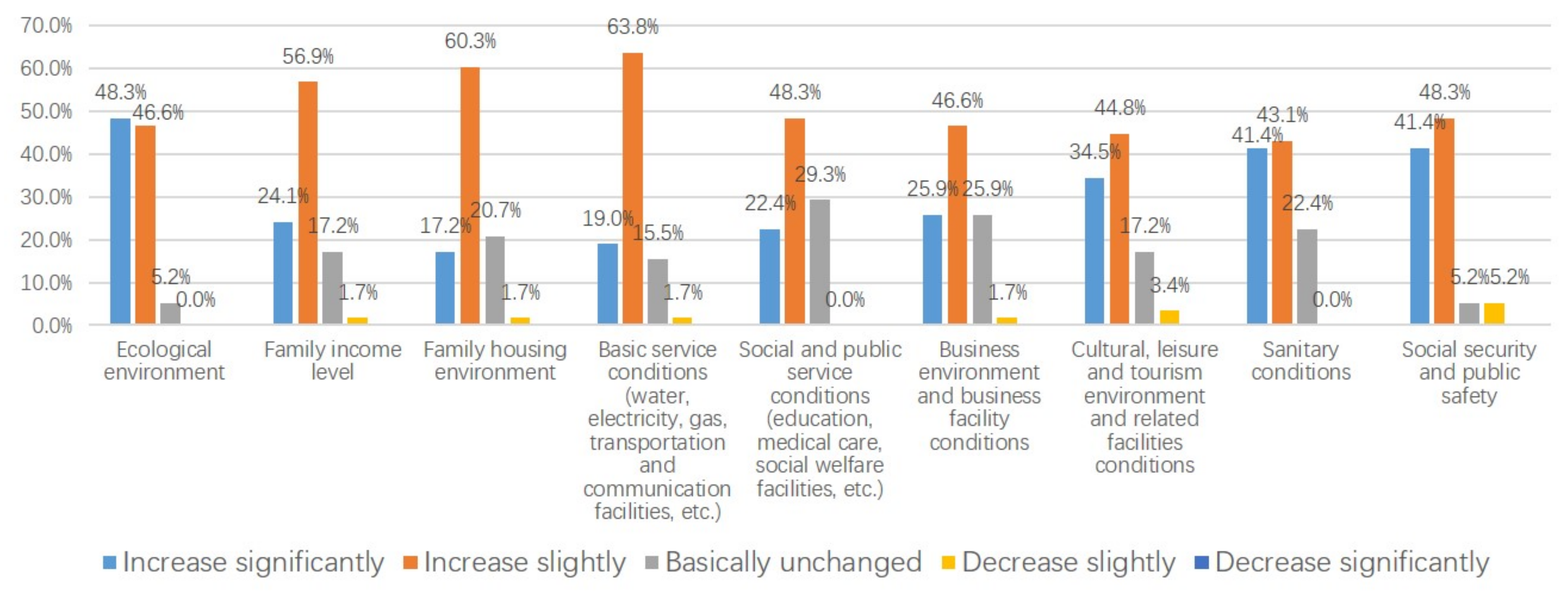

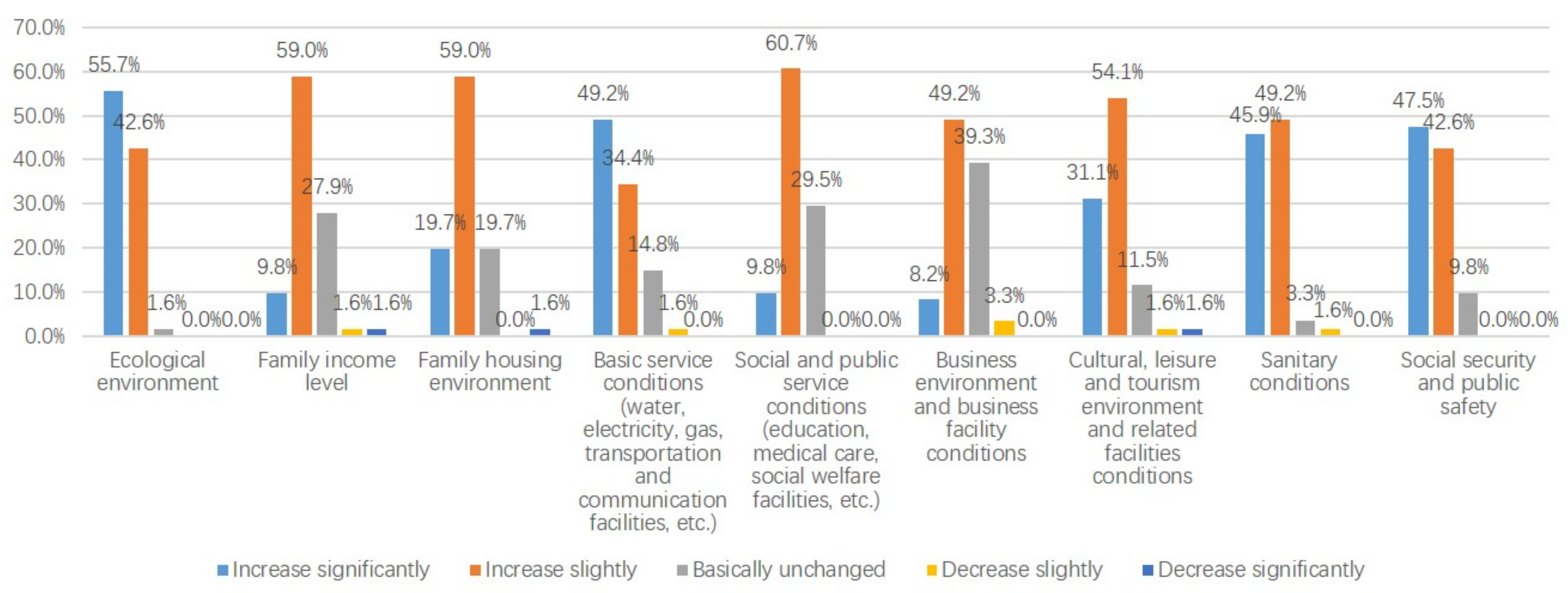

4.2. Living Standards: Overall but Limited Improvement

“I think, for us residents, the most important thing for us to improve our standard of living is, of course, the increase in economic income. This is the most real and fundamental thing. With the increase in income, we can then discuss other things. So when the CT practice started to develop here, I was looking forward to it helping to increase my income.” 1

“We live in such a messy environment. How can the standard of living be good? The environment must be improved. I want fresh air, clean roads, green spaces.” 2

“We need a good business environment and facilities, which can attract popularity, drive the economy and our income.” 3

“I have to admit that the environmental conditions we live in are really much better than before. It is really unbearable to look back on the bad ecological environment here in the past.” 4

“I feel that we have always lacked a sufficient business environment, even after the CT development. Without a good business environment, there will not be enough people willing to come. Especially for people like us who are engaged in our own small businesses, if there are not enough people willing to visit, the increase in income will also be affected.” 3

“After the development of the CT, the cultural and leisure conditions we can enjoy in our lives have improved a lot. Now we have many cultural and leisure facilities to use, not only parks and fitness facilities, but also many cultural venues, such as museums. These things enrich my life.” 5

“I feel that my housing environment has improved, but it’s not very obvious or important. It’s just that the facade of my house has been repaired, which can be said to improve my standard of living, but it’s not really that big of a positive influence” 6

“My house was demolished and relocated to an apartment building. If you want to say whether the housing environment has improved, you can say it has improved. Of course, it can be regarded as an improvement in living standards, but in fact, this itself is not very useful.” 7

“In general, this is definitely beneficial to the improvement of our living standards although it does not have such a big effect and influence on many places. I am looking forward to future developments that will really put things into practice that promote our good life.” 8

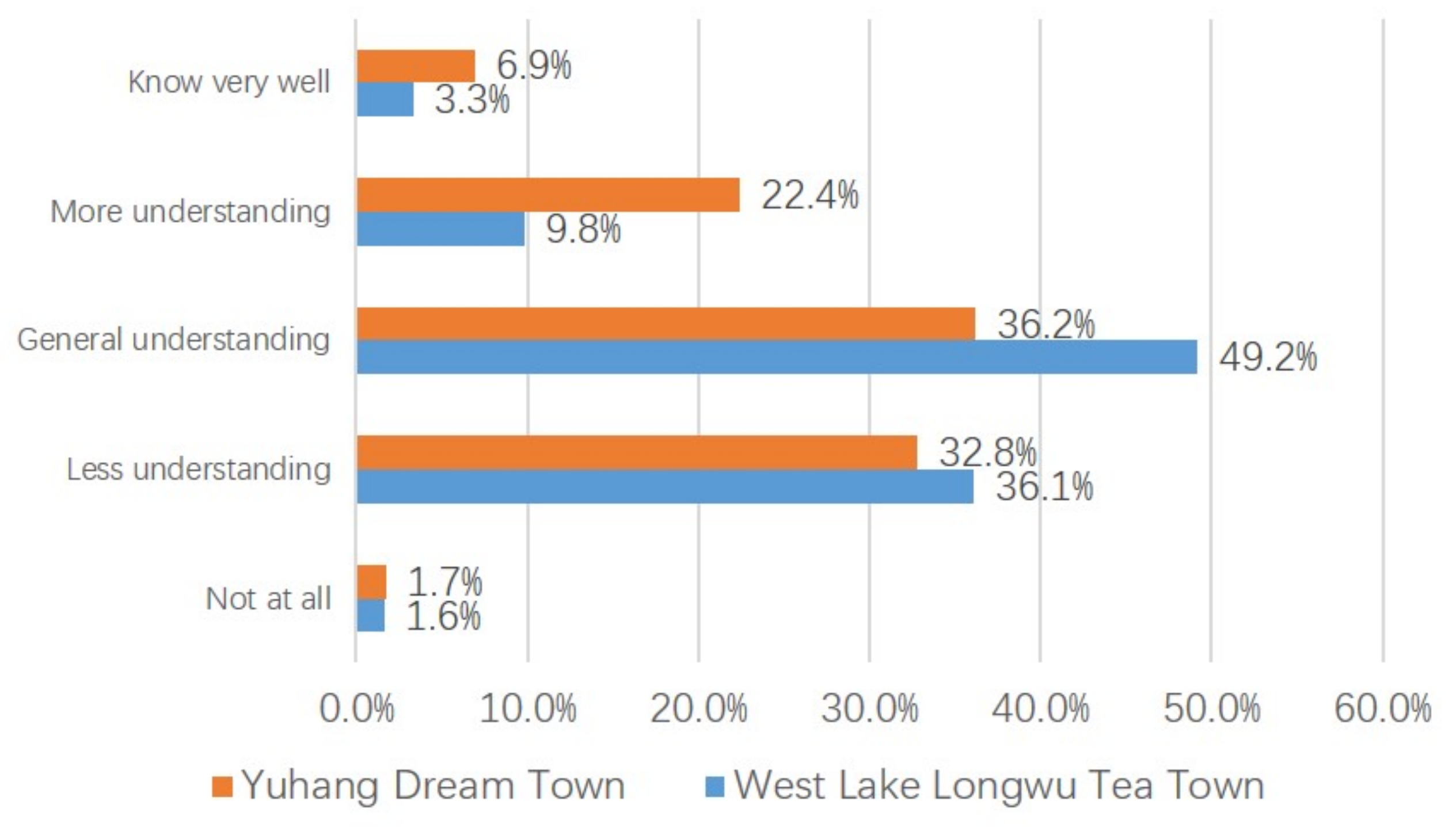

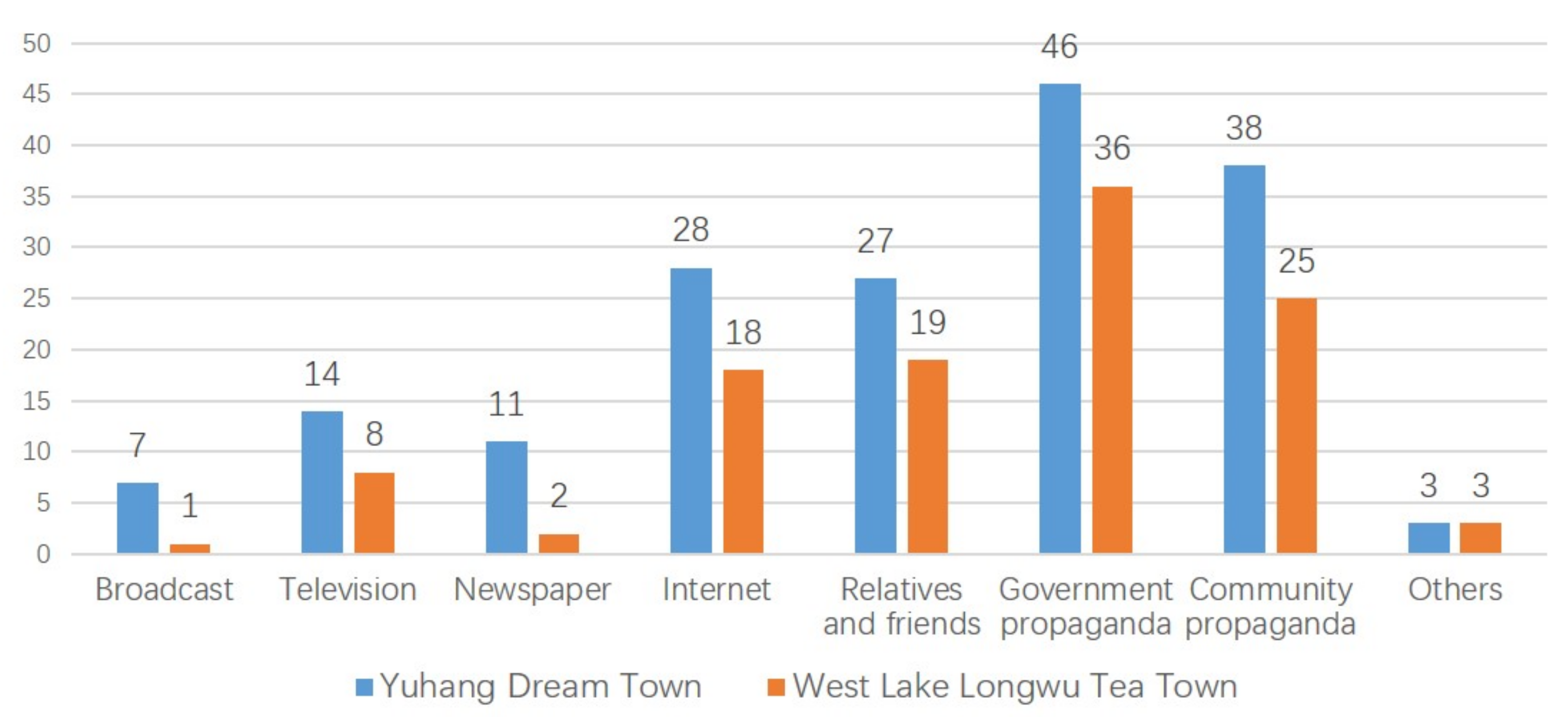

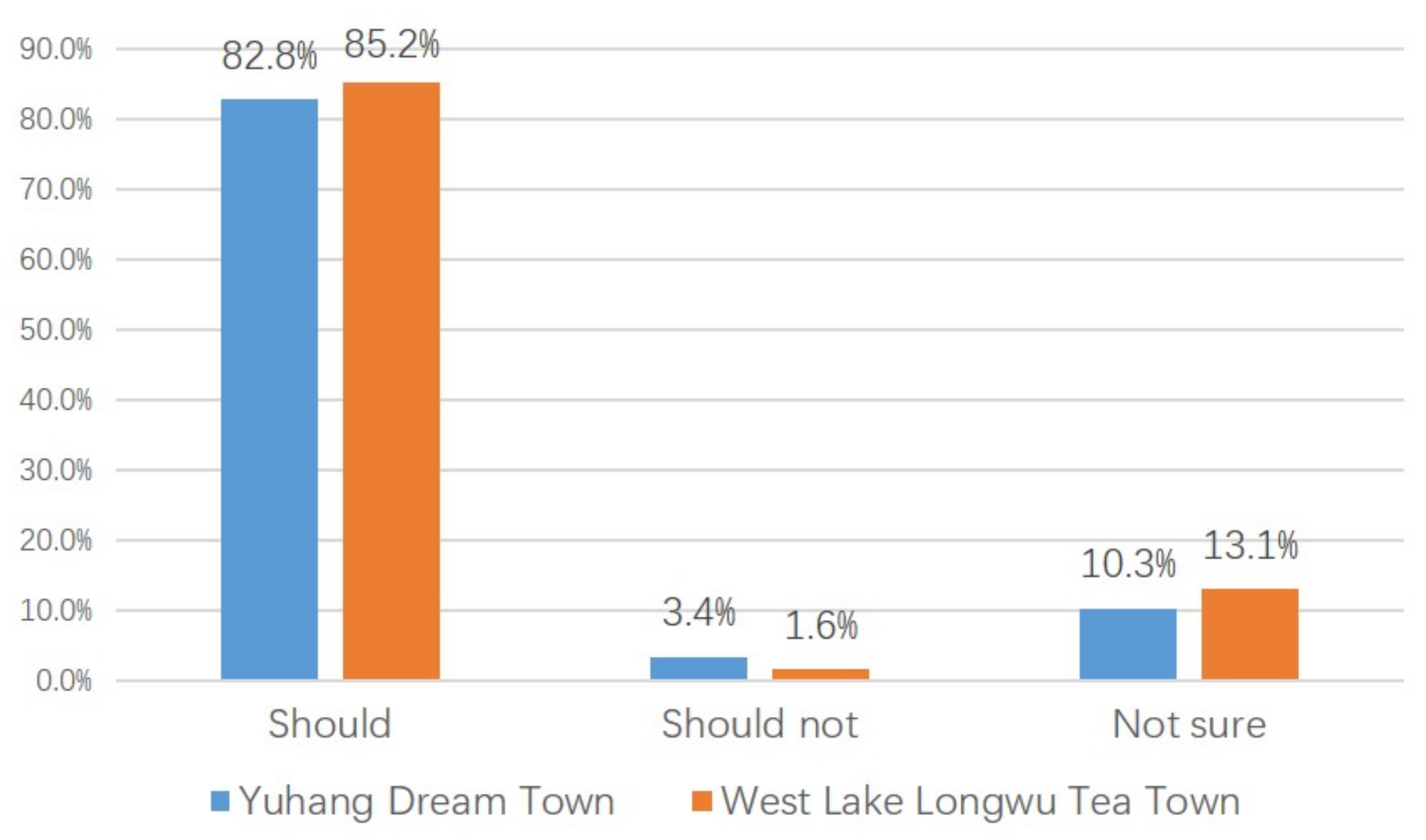

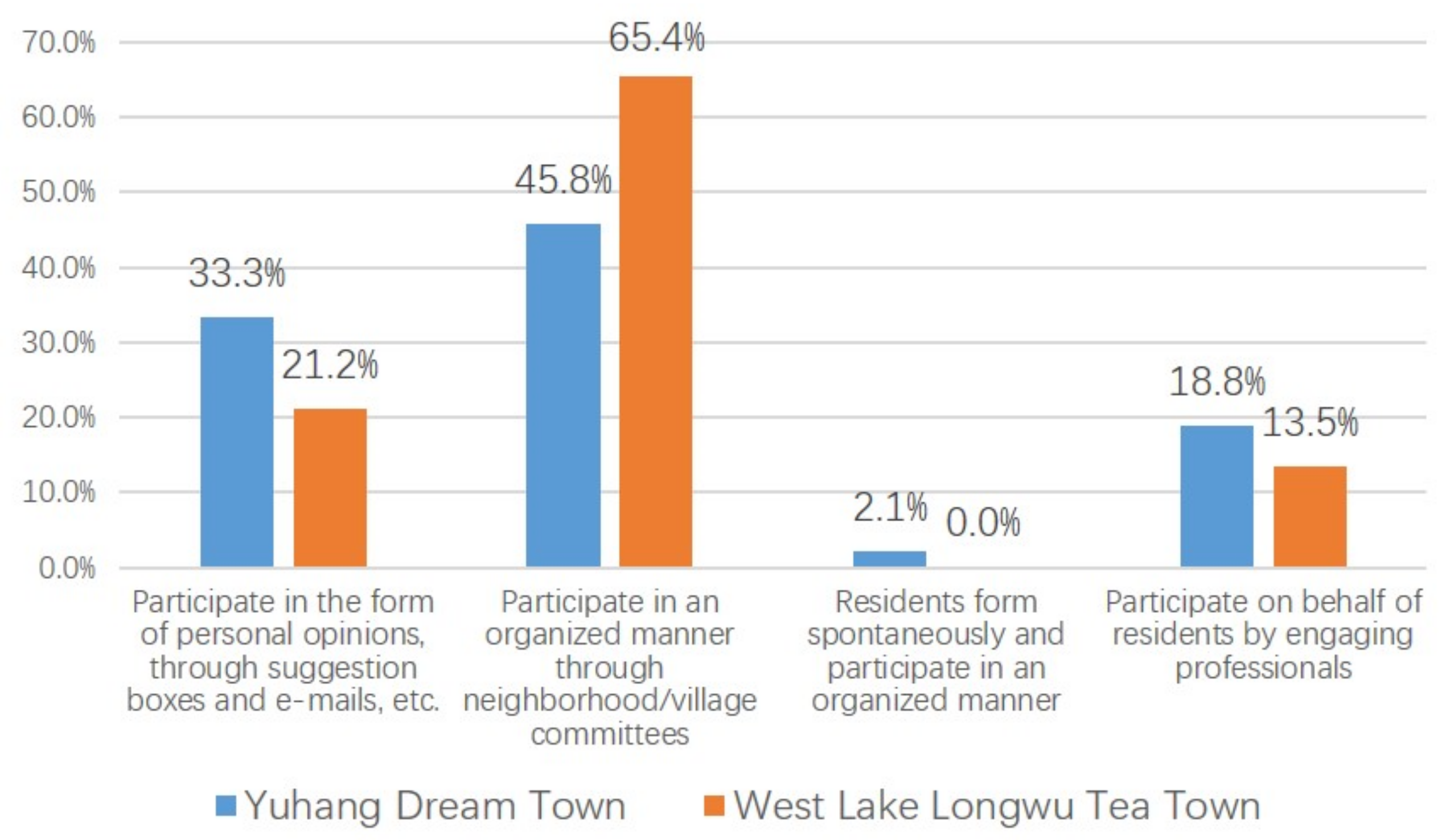

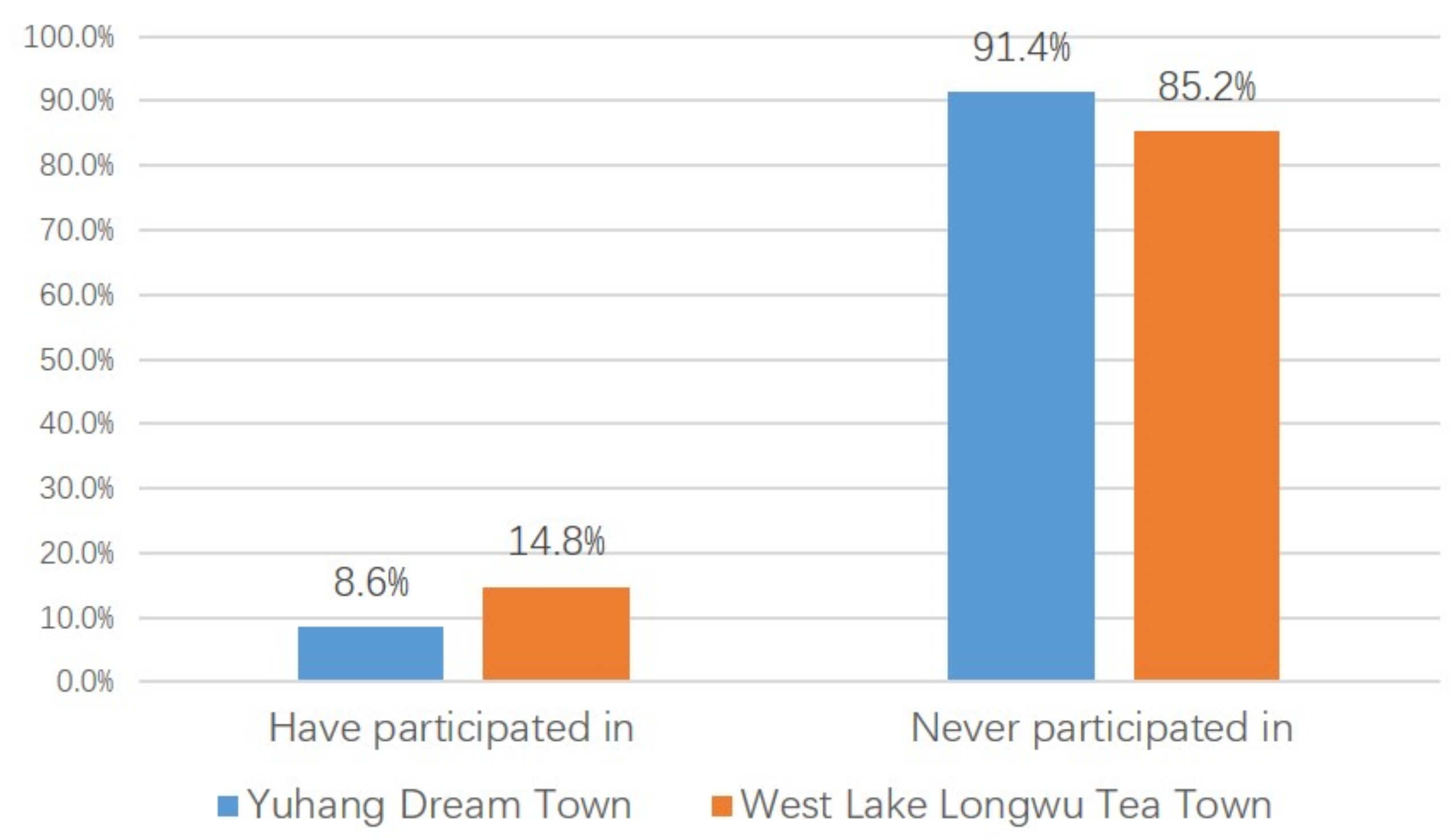

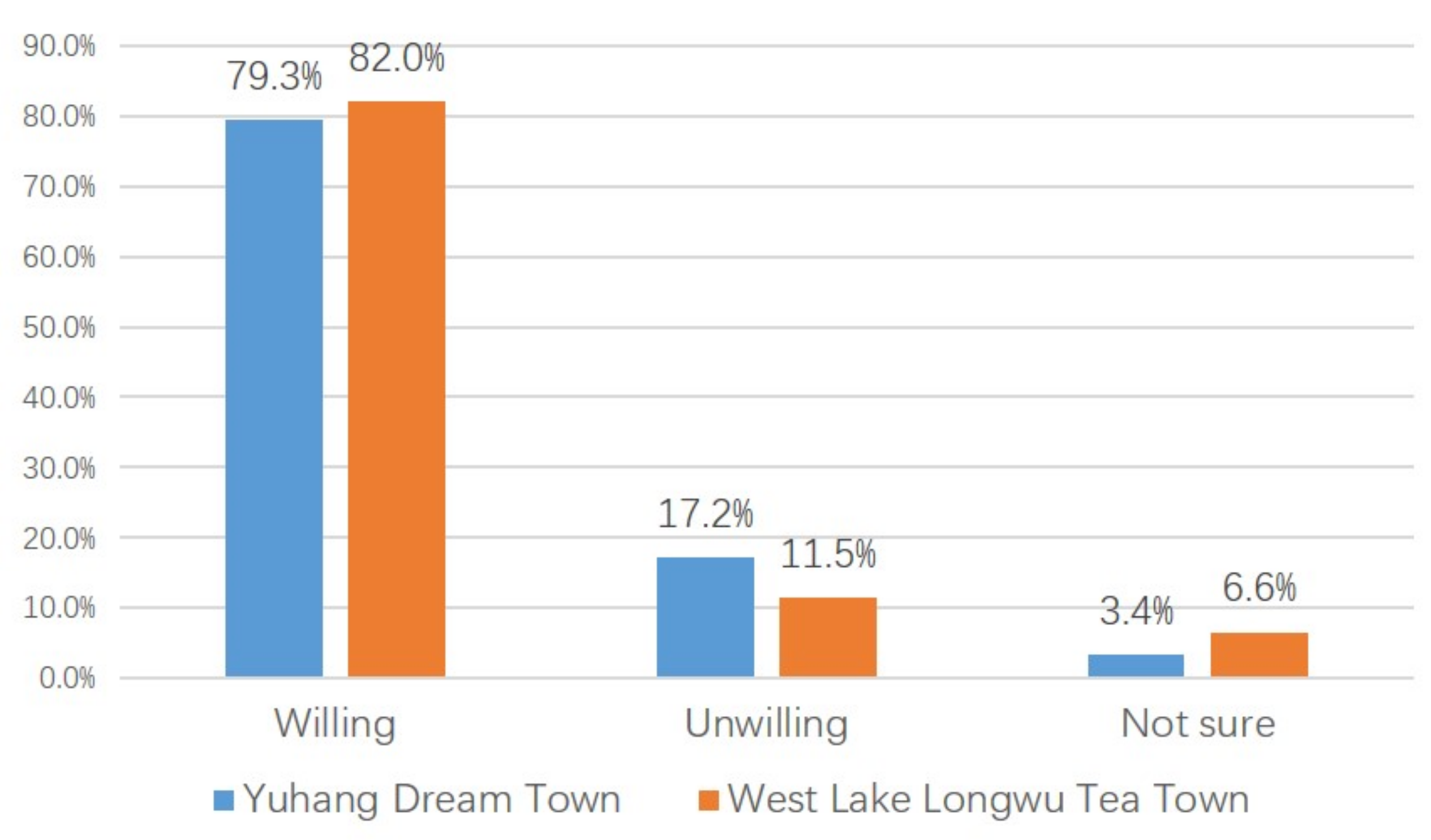

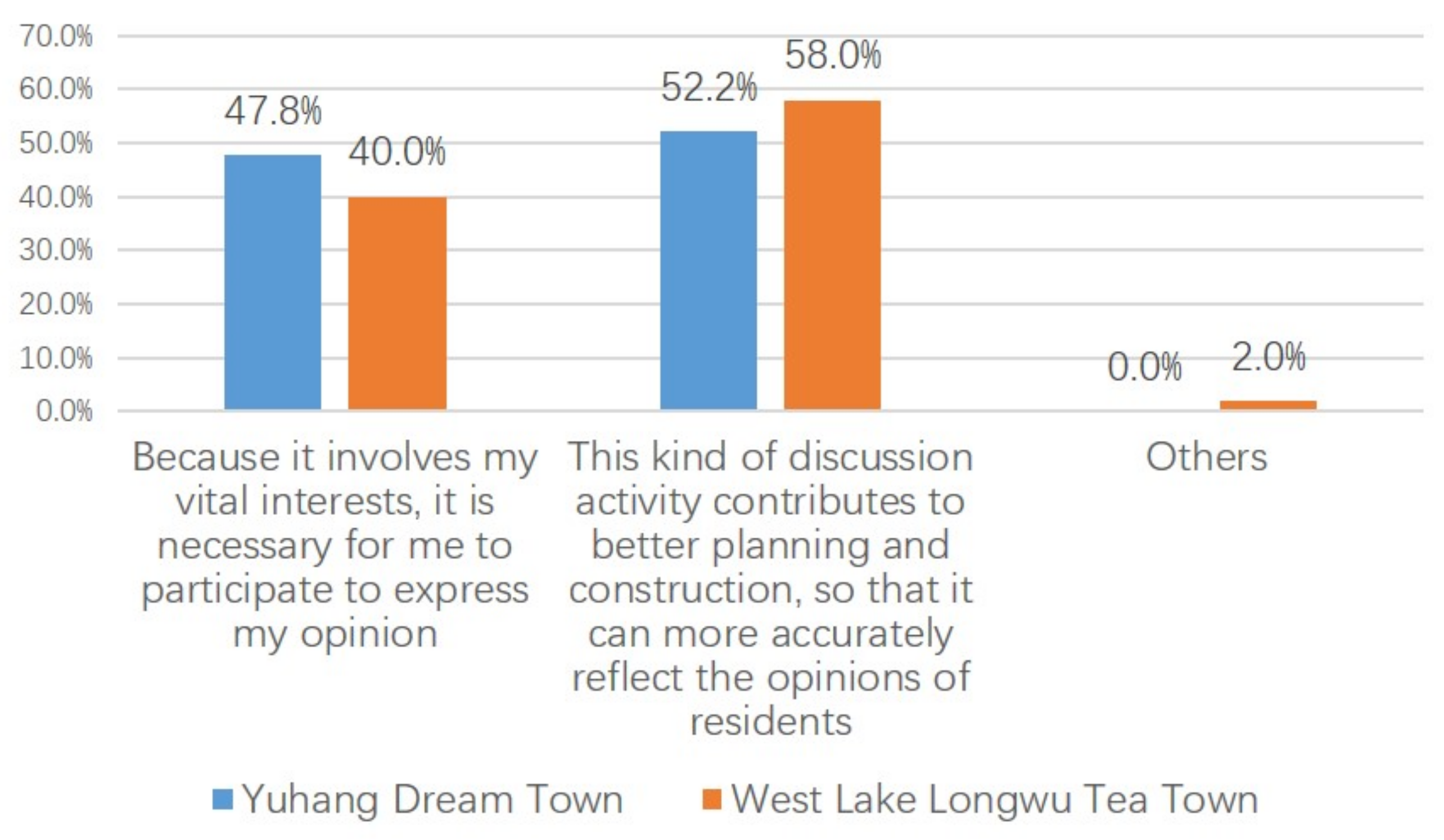

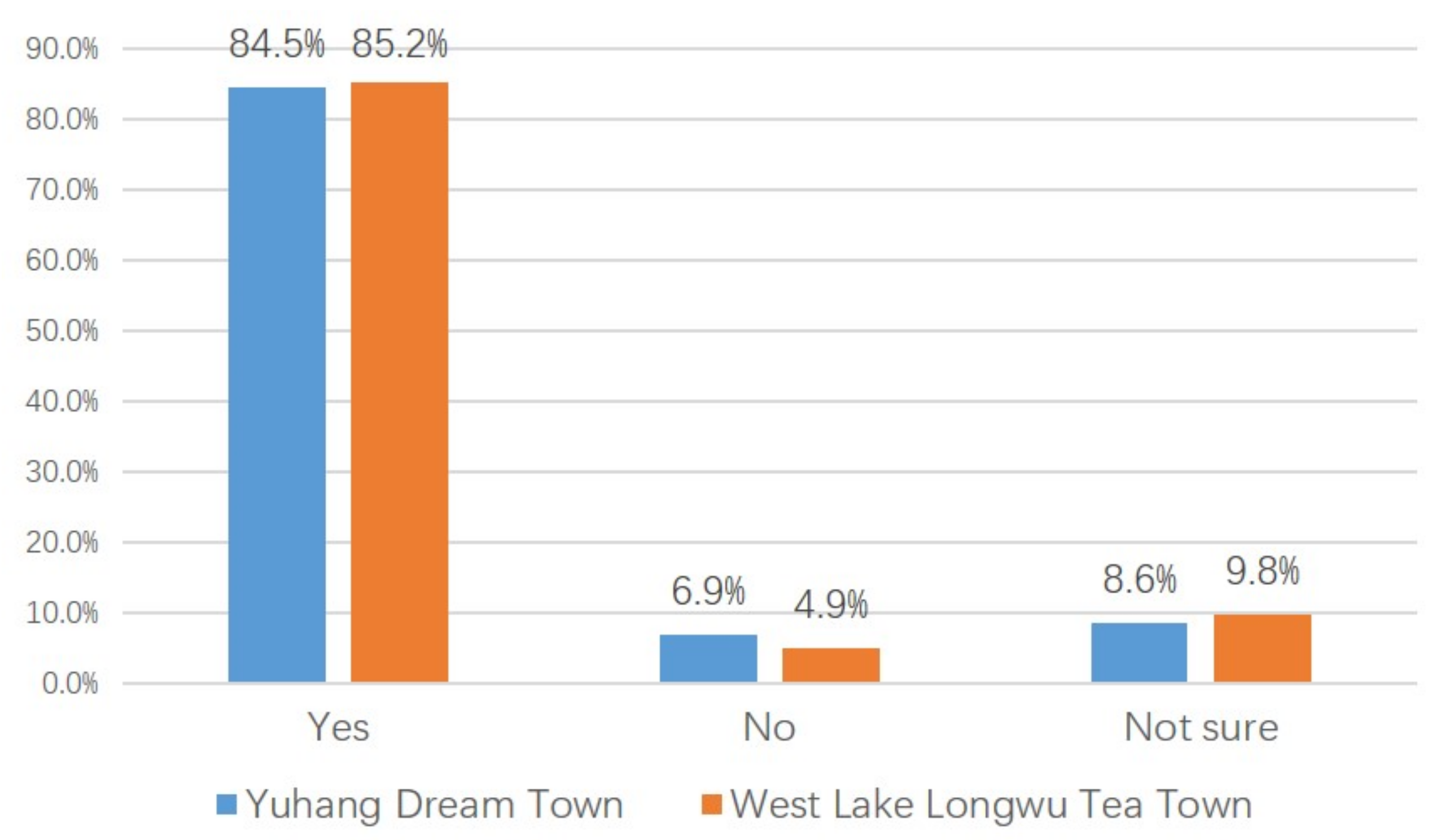

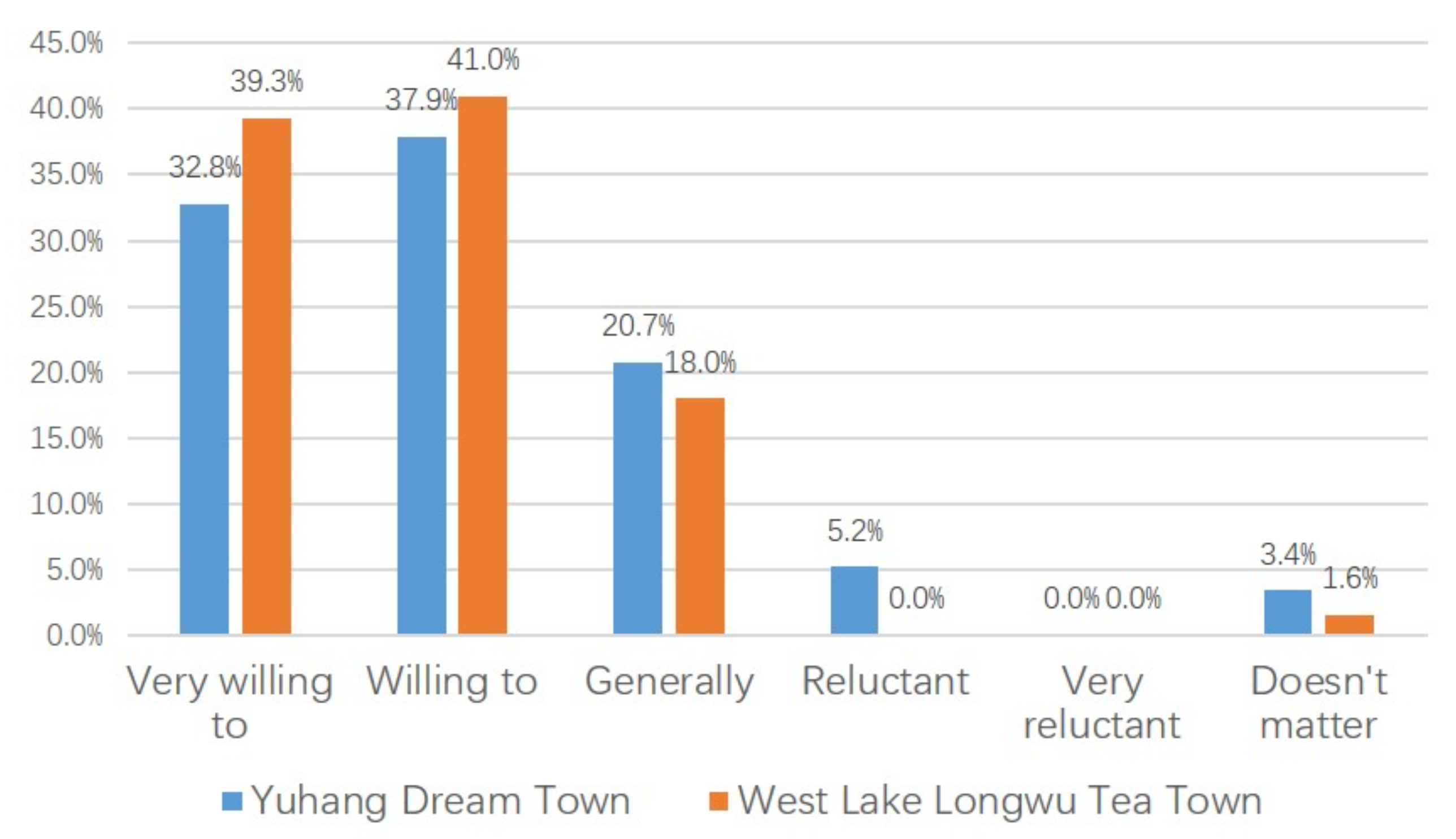

4.3. Public Participation: Very Limited Public Participation despite Positive Residents’ Wishes

“To be honest, we ordinary people have very limited understanding of the development of the local CT. We don’t really know what’s going on here and what to do in the future. In most cases, the government has come to tell us that something needs to be done, and we ordinary people are just passively cooperating.” 9

“Basically, the higher-level governments inform us through the village committee or sub-district office that they need to develop here, and then we will learn about these contents. Or sometimes we know some information ourselves through the Internet, newspapers, and other means. But we basically can’t get more details.” 10

“I hope that the village committee can organize everyone effectively, so that we can know what we should know in time, so as to respond. But now they are basically useless. They are currently only the government’s messenger, and it is difficult to really represent our interests.” 11

“I prefer this anonymous method, so that many things that cannot be said in official occasions can be said, and I don’t have to worry about being known by others.” 12

“I don’t want to participate in such activities, even if such activities really exist. Because I don’t think the opinions and ideas, we express in these events can really get the government’s attention or make them willing to make changes for us.” 3

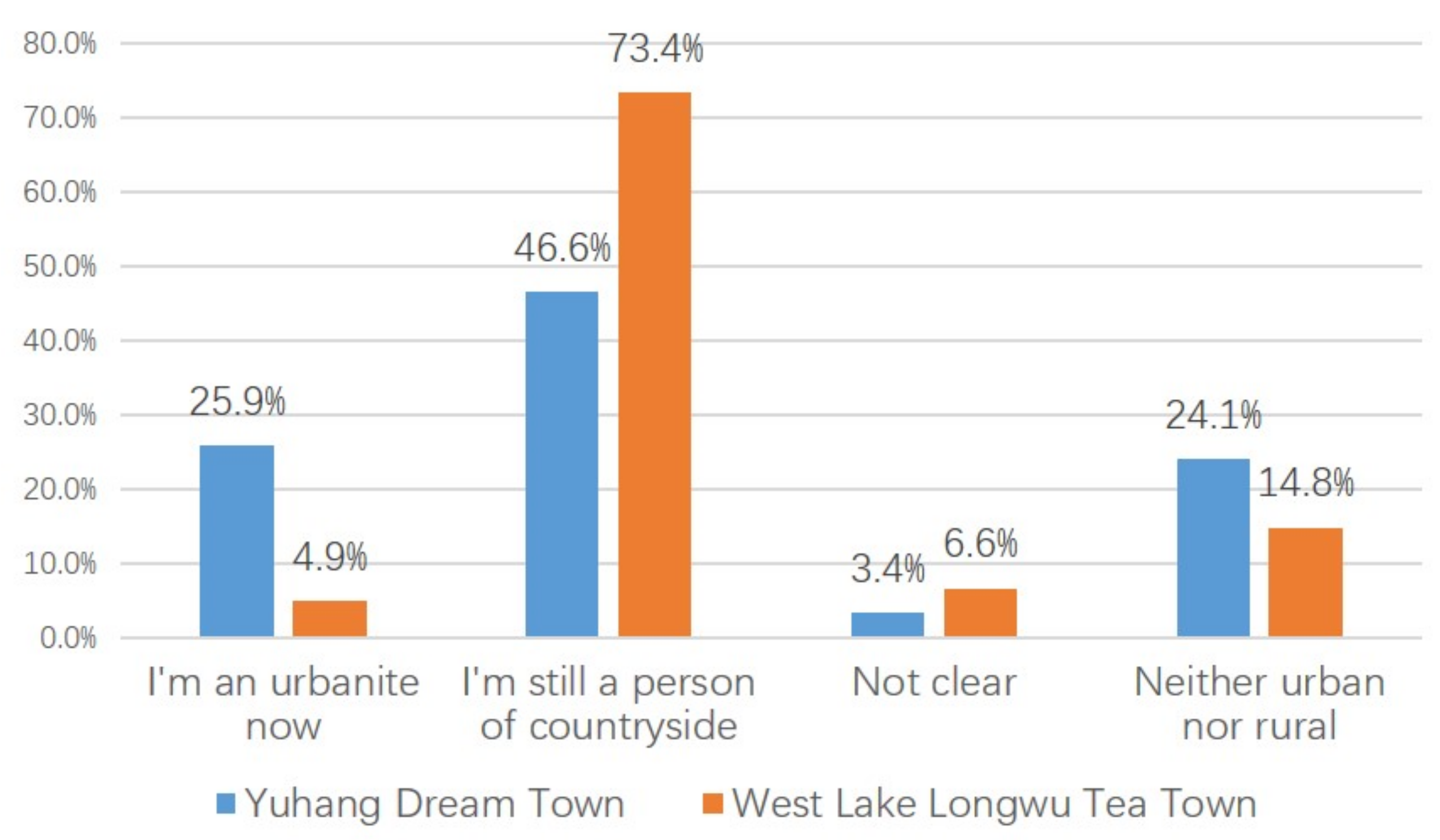

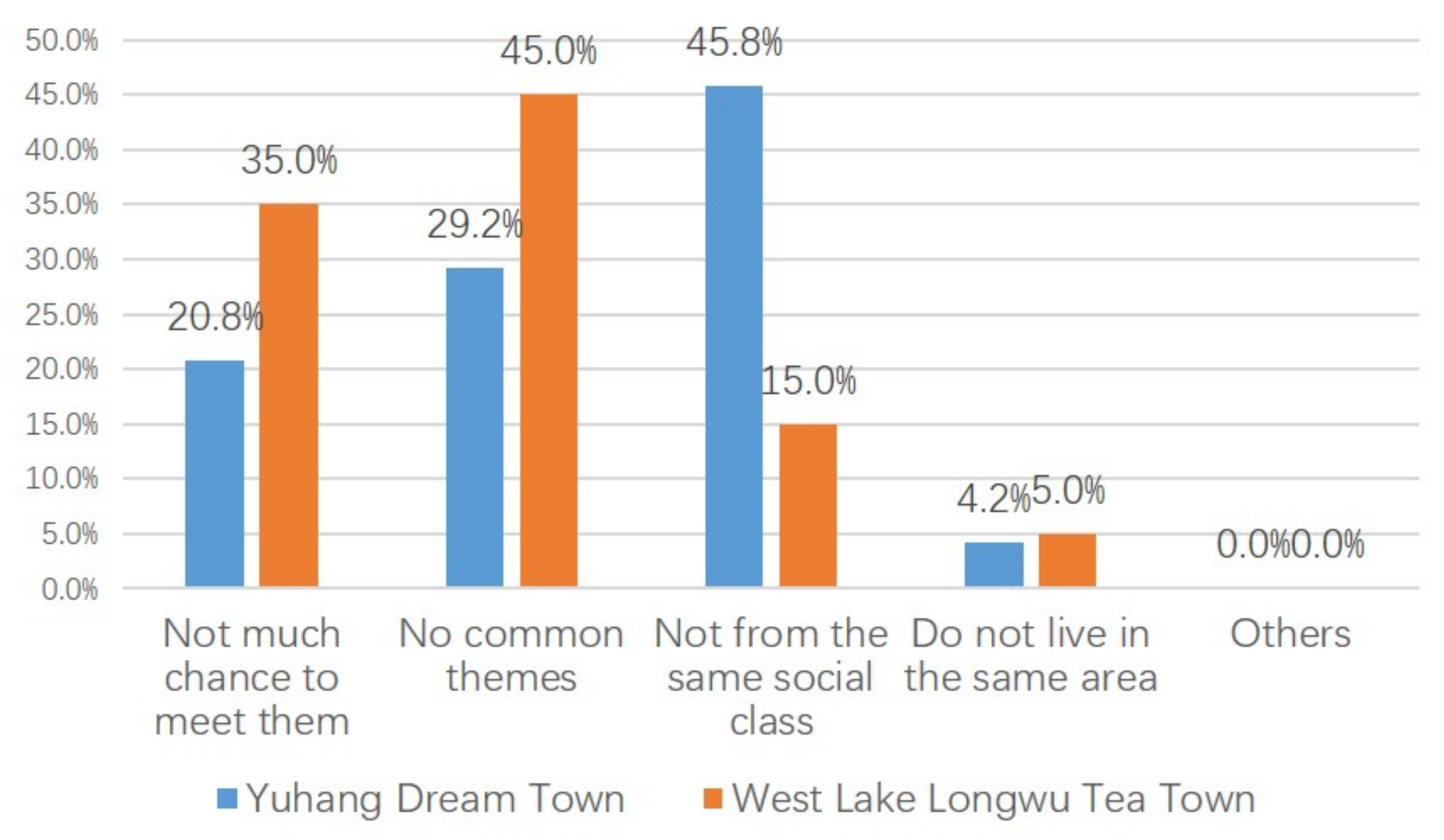

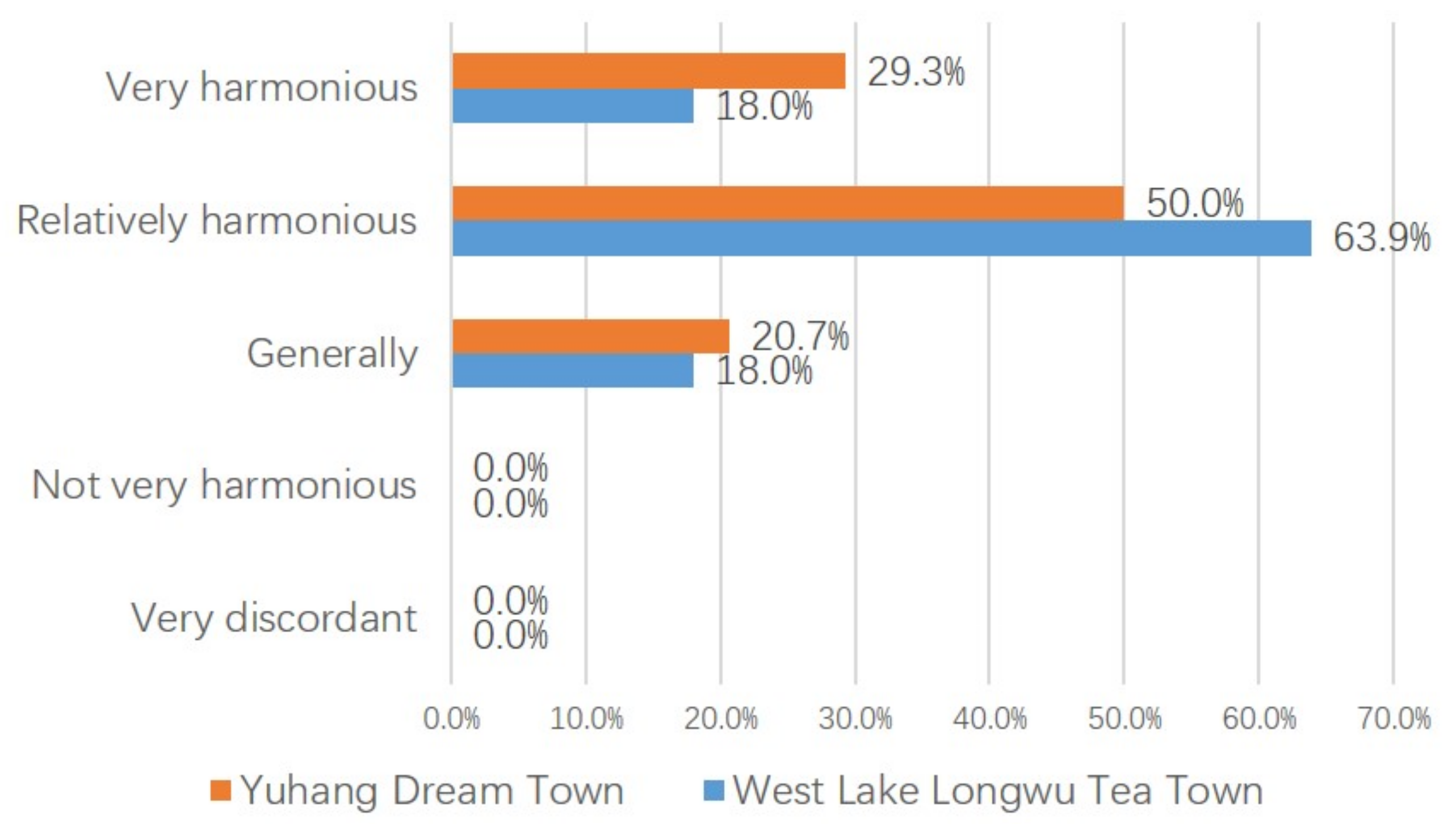

4.4. Self-Perception and Interpersonal Relationships: New Potential Changes and Dynamics

“I don’t know whether I am an urbanite or a person of countryside now because the situation is different. I am no longer a traditional rural person now, but I am not a typical urban person either. I sometimes feel confused and lost now and feel like I don’t belong to either side.” 17

“I don’t think I am a rural person anymore. Look at our current living environment, it is completely different from the previous rural area. I think I am an urban person now, but I just live in a relatively remote area.” 12

“I don’t think there is any so-called friendship between us. Unlike us, they are all highly educated talents, and we are not destined to be on the same level.” 10

“We all live in scattered places here. We don’t often see migrant workers.” 18

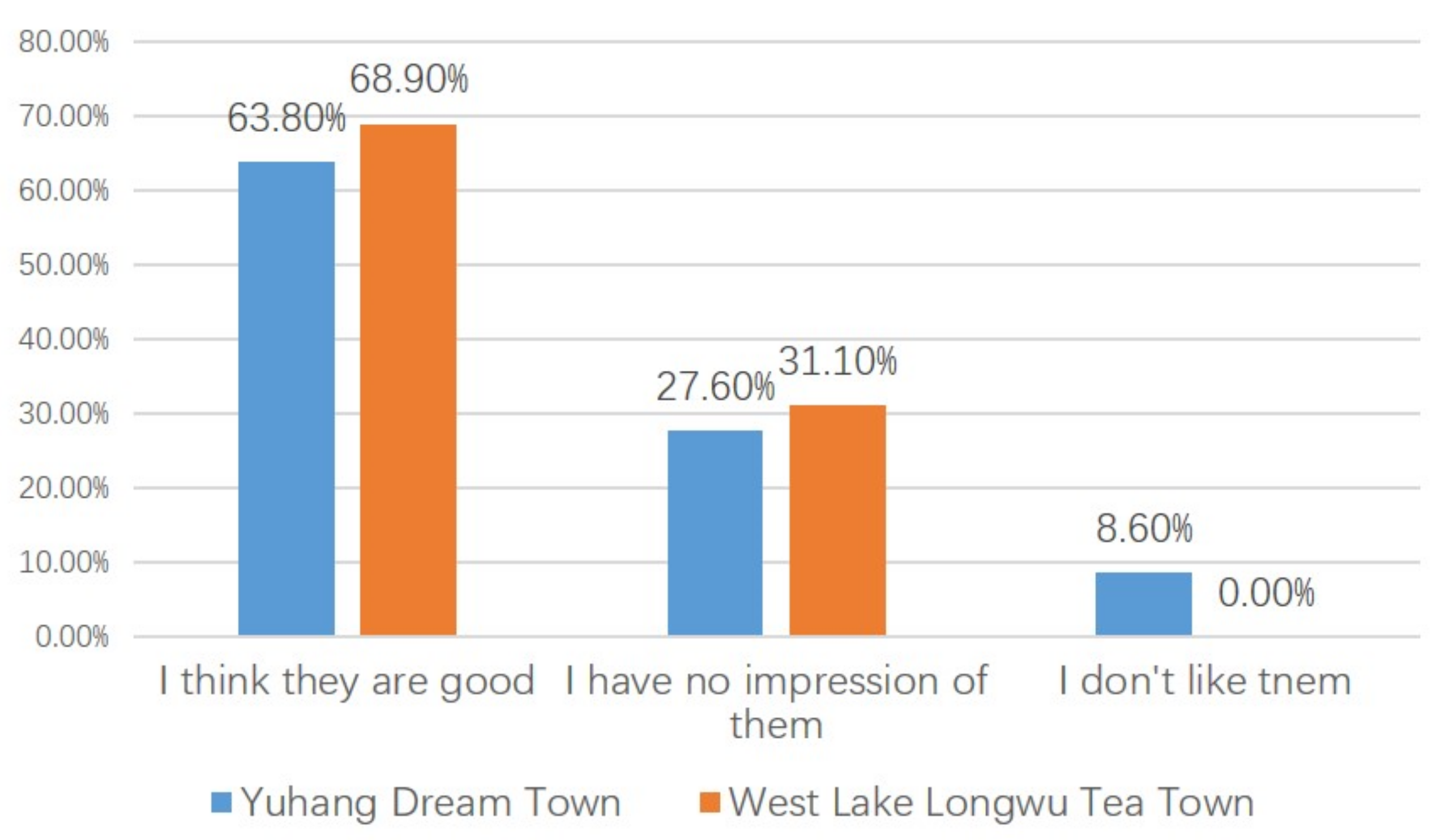

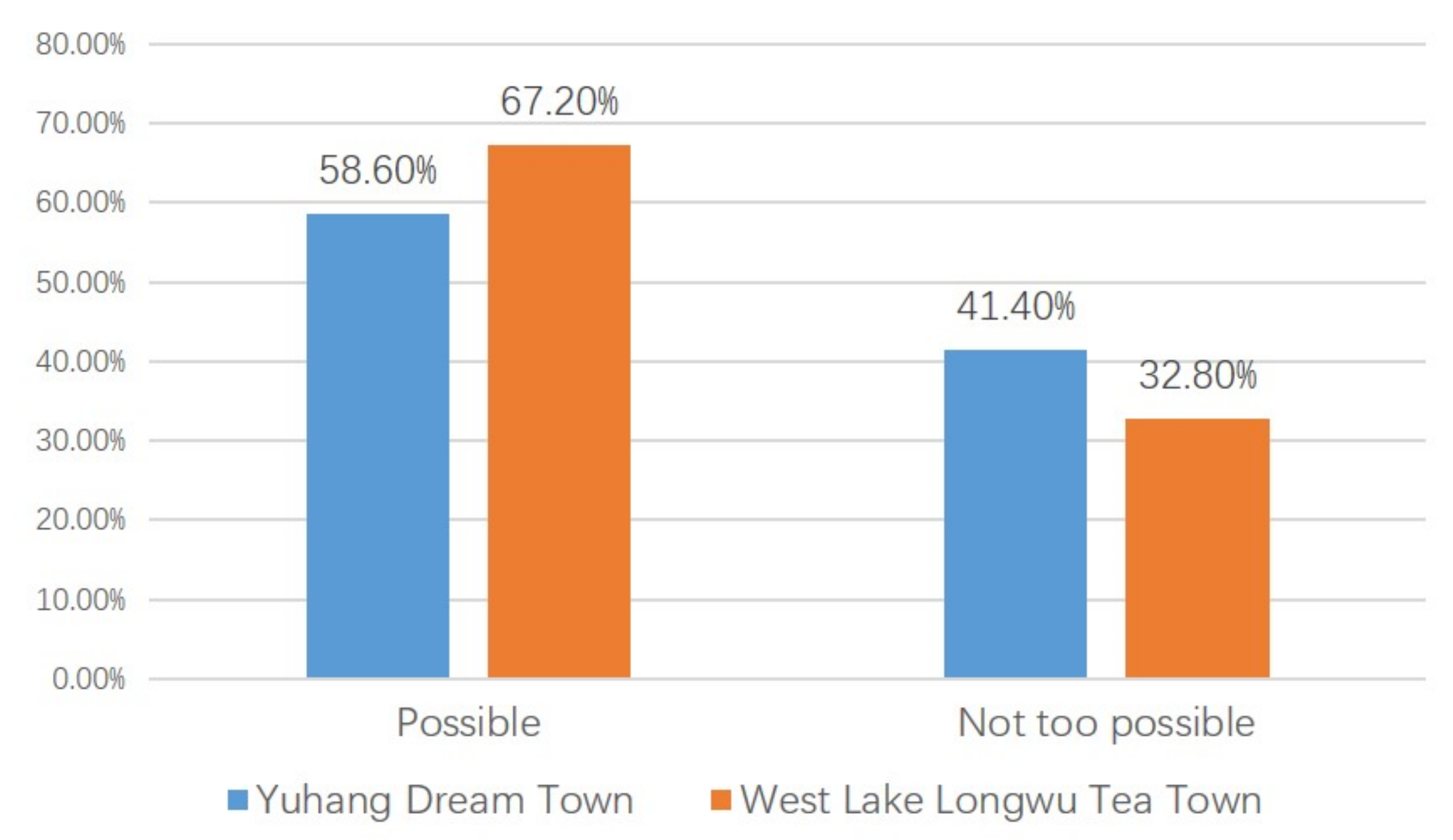

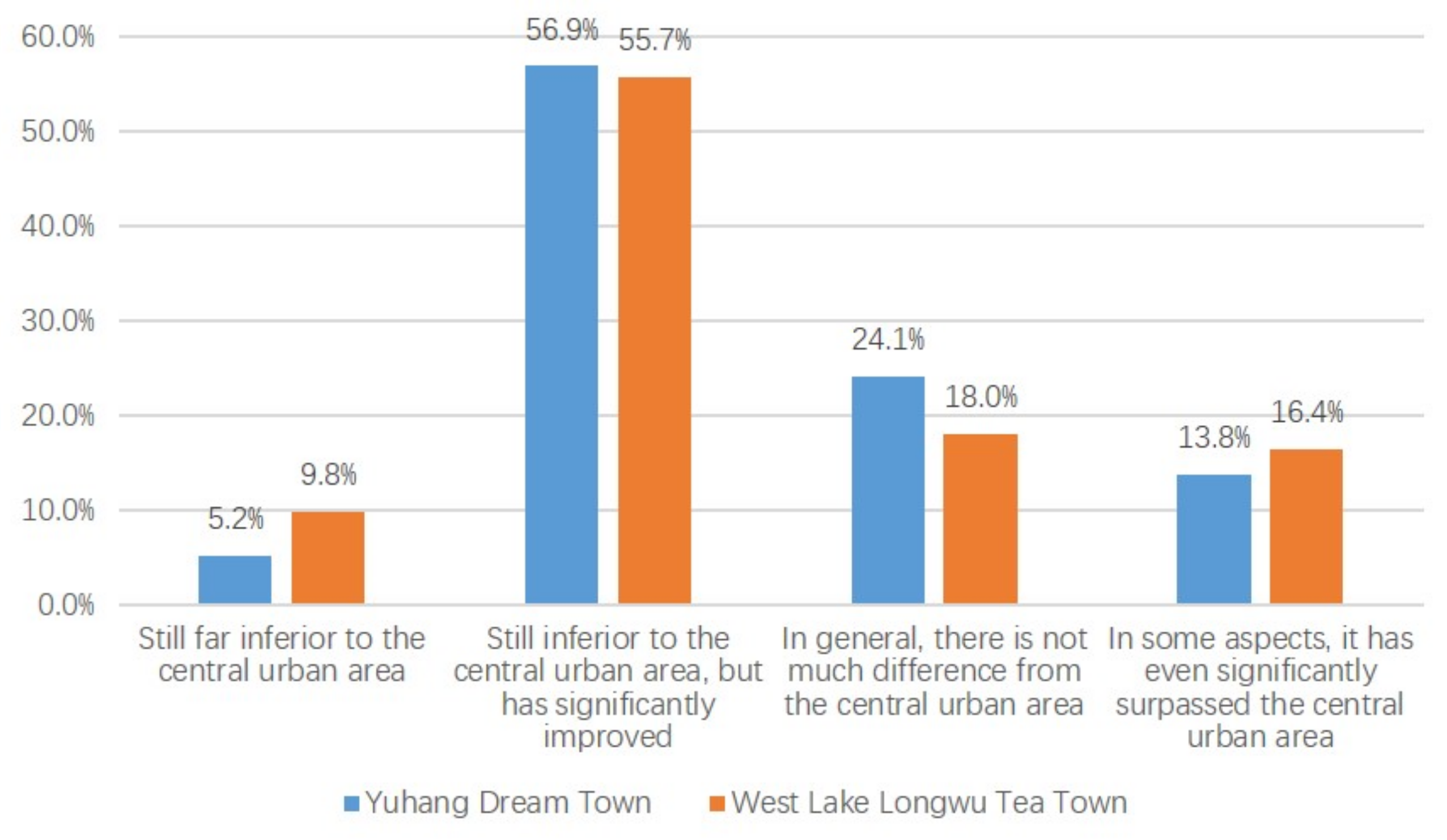

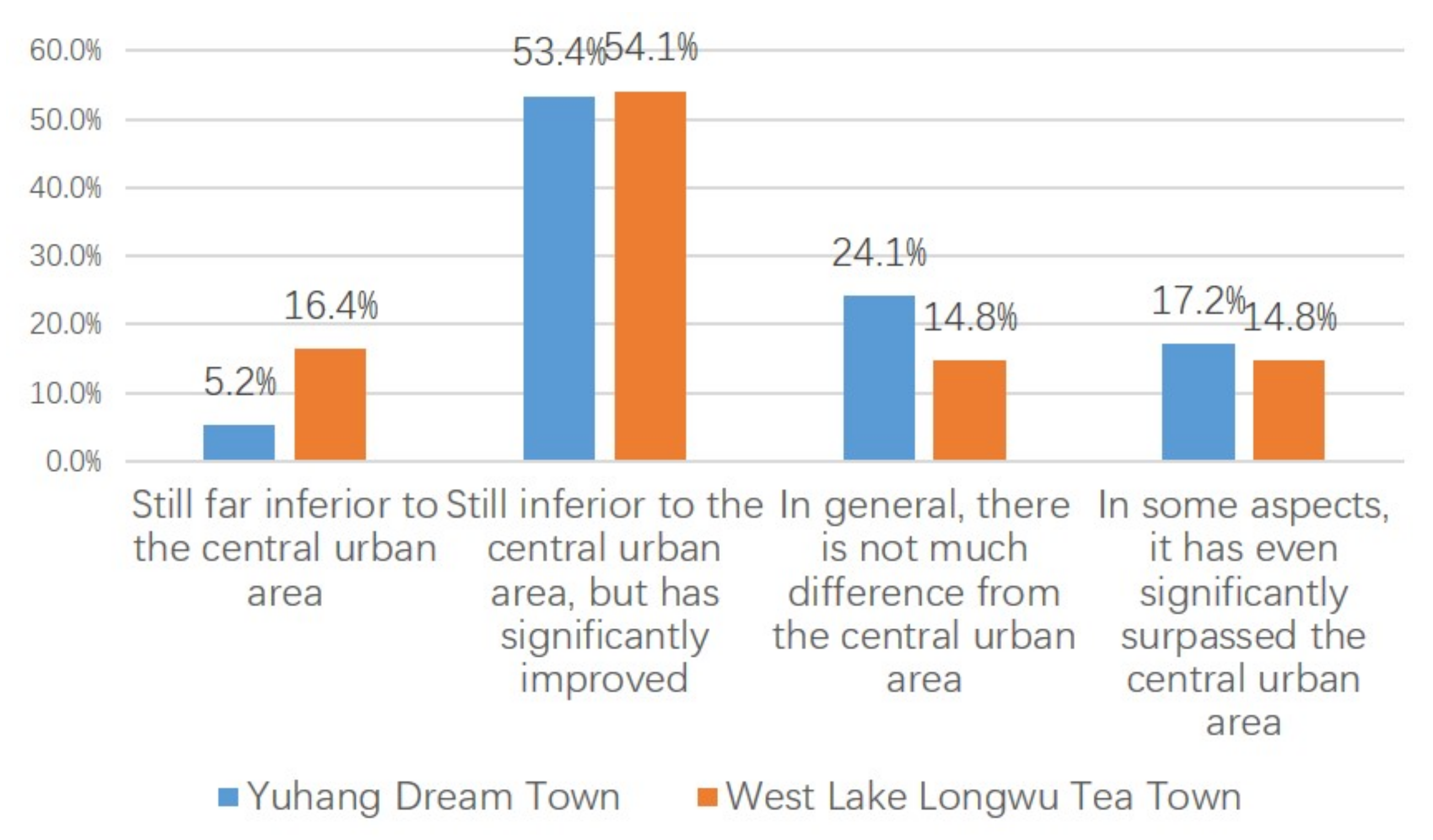

4.5. Overall Assessment of Local Development: Overall Recognition but Obvious Differences

“If you would say the biggest boost to local development, I think the most obvious is definitely the environment and infrastructure. Now these conditions here have been greatly improved, from the ‘low level of the countryside’ to the ‘high level of the city’.” 1

“I think one of the biggest contributions of the CT practice to the local development is to improve our reputation here. For example, when Longwu was mentioned in the past, everyone would confuse it with another place called Longjuwu. Now, as long as when it comes to Longwu, everyone knows that this is a famous tea-related area.” 3

“When we talk about Cangqian now, everyone will think of the well-known entrepreneurial city. Who would have thought that not many years ago, this place was still a barren farmland?” 19

“I think the role of the CT practice in the development of tourism here exists. Tourism development can be said to have developed from nothing. But I am still not very satisfied because I think it could have done more and better.” 19

“Our place has actually made great progress, but compared with the area where YDT is located, it is still closer to traditional rural areas, without enough development degree. Residents have high expectations for the CT practice to drive local development, but the reality will be more difficult. After all, the development foundation here is not as good as that of the area where YDT is located, so the speed of development will definitely be slower and there will be more problems. Therefore, the psychological gap of residents will be relatively large.” 12

“I feel that we should pay attention to the development of commercial facilities here. Now there are many migrant workers here, and a lot of beautiful landscapes have been created. If more commercial conditions can be developed in the next step, more people and investments can be attracted here, making this area more prosperous.” 6

“I think our future development here will undoubtedly need to focus on tourism development. We have good natural and human conditions, and the current development is also improving this content, so why not make good use of these?” 8

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 26 December 2021. R8 |

| 2 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 10 March 2022. R16 |

| 3 | Interview: Resident of the area where West Lake Longwu Tea Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 4 March 2022. R10 |

| 4 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 25 March 2022. R17 |

| 5 | Interview: Resident of the area where West Lake Longwu Tea Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 4 March 2022. R11 |

| 6 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 26 December 2021. R9 |

| 7 | Interview: Resident of the area where West Lake Longwu Tea Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 9 March 2022. R14 |

| 8 | Interview: Resident of the area where West Lake Longwu Tea Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 9 March 2022. R13 |

| 9 | Interview: Resident of the area where West Lake Longwu Tea Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 7 March 2022. R12 |

| 10 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 13 December 2021. R4 |

| 11 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 13 December 2021. R5 |

| 12 | Interview: Resident of the area where West Lake Longwu Tea Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 10 March 2022. R15 |

| 13 | Interview: Deputy Director of Management Committee of Hangzhou West Science and Technology Innovation Corridor, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 15 December 2021. G1 |

| 14 | Interview: Director of Regional Development Office of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 30 December 2021. G4 |

| 15 | Interview: Associate Professor of the Department of Human Geography and Urban and Rural Planning, School of Geography, Nanjing Normal University, 19 April 2022. S3 |

| 16 | Interview: Manager of Investment Department of Hangzhou Zhijiang Operation Management Group Co., Ltd., 2 March 2022. D2 |

| 17 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 13 December 2021. R2 |

| 18 | Interview: Resident of the area where West Lake Longwu Tea Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 13 December 2021. R6 |

| 19 | Interview: Resident of the area where Yuhang Dream Town is located, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, 13 December 2021. R3 |

References

- Seto, K.C.; Fragkias, M.; Güneralp, B.; Reilly, M.K. A Meta-Analysis of Global Urban Land Expansion. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Hamidi, S. Compactness versus Sprawl: A Review of Recent Evidence from the United States. J Plan Lit. 2015, 30, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, S.; Ewing, R. A Longitudinal Study of Changes in Urban Sprawl between 2000 and 2010 in the United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 128, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, E.I.; Schwick, C.; Soukup, T.; Orlitová, E.; Kienast, F.; Jaeger, J.A. Multi-scale Analysis of Urban Sprawl in Europe: Towards a European De-sprawling Strategy. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, M.V.; Hilber, C.A.; Schöni, O. Institutional Settings and Urban Sprawl: Evidence from Europe. J. Hous. Econ. 2018, 42, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama, M.R.; Wyatt, R.; Shaddel, L. A Spatial-temporal Analysis of Urban Growth in Melbourne; Were Local Government Areas Moving Toward Compact or Sprawl from 2001–2016? Appl. Geogr. 2020, 124, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, O.; Blija, D.K.; Ayambire, R.A.; Takyi, S.A.; Mensah, H.; Braimah, I. Global Urban Sprawl Containment Strategies and Their Implications for Rapidly Urbanising Cities in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magidi, J.; Ahmed, F. Assessing Urban Sprawl Using Remote Sensing and Landscape Metrics: A Case Study of City of Tshwane, South Africa (1984–2015). Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2019, 22, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Espindola, G.M.; da Costa Carneiro, E.L.N.; Façanha, A.C. Four Decades of Urban Sprawl and Population Growth in Teresina, Brazil. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 79, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, L.; Baur, R.; Csaplovics, E. Urban Sprawl and Fragmentation in Latin America: A Dynamic Quantification and Characterization of Spatial Patterns. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 115, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniekwe, S.; Igu, N.I. A Geographical Analysis of Urban Sprawl in Abuja, Nigeria. J. Geogr. Res. 2019, 2, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, V.; Pradilla, M.M.S. Identifying the Social Urban Spatial Structure of Vulnerability: Towards Climate Change Equity in Bogotá. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, P.A.; ul Shafiq, M.; Mir, A.A.; Ahmed, P. Urban Sprawl and Its Impact on Landuse/Land Cover Dynamics of Dehradun City, India. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartone, A.; Díaz-Dapena, A.; Langarita, R.; Rubiera-Morollón, F. Where the City Lights Shine? Measuring the Effect of Sprawl on Electricity Consumption in Spain. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A. Dynamics of Urbanization and Its Impact on Urban Ecosystem Services (UESs): A Study of a Medium Size Town of West Bengal, Eastern India. J. Urban Manag. 2019, 8, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P. The Environmental, Social, and Cultural Impacts of Sprawl. Nat. Resour. Environ. 2001, 15, 219–267. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.L.; Wang, S.H.; Budd, W.W. Sprawl in Taipei’s Peri-urban Zone: Responses to Spatial Planning and Implications for Adapting Global Environmental Change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 90, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murungweni, F.M. Effect of Land Use Change on Quality of Urban Wetlands: A Case of Monavale Wetland in Harare. Geoinformatics Geostat. Overv. 2013, s1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Sumari, N.S.; Portnov, A.; Ujoh, F.; Musakwa, W.; Mandela, P.J. Urban Sprawl and Its Impact on Sustainable Urban Development: A Combination of Remote Sensing and Social Media Data. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 24, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.D.; Ewing, R. Urban Expansion, Sprawl and Inequalit. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Rethinking Urban Sprawl: Moving Towards Sustainable Cities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hassel, A. Public policy. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 569–575. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, M.; Liu, Y.; Lieske, S.N.; Chen, T. Public Policy Change and Its Impact on Urban Expansion: An Evaluation of 265 Cities in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidoro, M.; De Lollo, J.A.; Barros, M.V.F. Urban Sprawl and the Challenges for Urban Planning. J. Environ. Prot. 2012, 3, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, B. Measuring Urban Sprawl and Exploring the Role Planning Plays: A Shanghai Case Study. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, K.; Aboelnga, H.T.; Babel, M.S.; Ribbe, L.; Shinde, V.R.; Sharma, D.; Dang, N.M. Urban Water Security: A Comparative Assessment and Policy Analysis of Five Cities in Diverse Developing Countries of Asia. Environ. Dev. 2022, 43, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuuter, T.; Lill, I.; Tupenaite, L. Comparison of Housing Market Sustainability in European Countries based on Multiple Criteria Assessment. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidsma, P.; König, H.; Feng, S.; Bezlepkina, I.; Nesheim, I.; Bonin, M.; Sghaier, M.; Purushothaman, S.; Sieber, S.; van Ittersum, M.K.; et al. Methods and Tools for Integrated Assessment of Land Use Policies on Sustainable Development in Developing Countries. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, W.G.; Urmee, T.; Simsek, Y.; Bahri, P.A.; Anisuzzaman, M. An Assessment of Energy Policy Impacts on Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7 in Indonesia. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 59, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, A.; Seier, G.; Proebstl-Haider, U. Policies Related to Sustainable Tourism–An Assessment and Comparison of European Policies, Frameworks and Plans. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 29, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, M.; Vandyck, T.; Los Santos, L.R.; Tamba, M.; Temursho, U.; Wojtowicz, K. A Comprehensive Socio-economic Assessment of EU Climate Policy Pathways. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 204, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, S. The Impact of Privatization of Public Housing on Housing Affordability in Beijing: An Assessment Using Household Survey Data. Local Econ. 2011, 26, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The Urbanization of Capital; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett, J. The Entrepreneurial State in China: Real Estate and Commerce Departments in Reform Era Tianjin; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. The (Post-) Socialist Entrepreneurial City as a State Project: Shanghai’s Reglobalisation in Question. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1673–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Planning Centrality, Market Instruments: Governing Chinese Urban Transformation Under State Entrepreneurialism. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1383–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. The State Acts Through the Market: ‘State Entrepreneurialism’, Beyond Varieties of Urban Entrepreneurialism. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yeh, A. Decoding Urban Land Governance: State Reconstruction in Contemporary Chinese Cities. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. Land Market Forces and Government’s Role in Sprawl. Cities 2000, 17, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Huang, Y. Uneven Land Reform and Urban Sprawl in China: The Case of Beijing. Prog. Plan. 2004, 61, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Phelps, N.A. From Suburbia to Post-Suburbia in China? Aspects of the Transformation of the Beijing and Shanghai Global City Regions. Built Environ. 2008, 34, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Phelps, N.A. (Post) Suburban Development and State Entrepreneurialism in Beijing’s Outer Suburbs. Environ. Plan A. 2011, 43, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, F. China’s Emerging Neoliberal Urbanism: Perspectives from Urban Redevelopment. Antipode 2009, 41, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B. Residential Redevelopment and the Entrepreneurial Local State: The Implications of Beijing’s Shifting Emphasis on Urban Redevelopment Policies. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 2815–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S.; Uchida, E. Economic Growth and the Expansion of Urban Land in China. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 813–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Su, F.; Liu, M.; Cao, G. Land Leasing and Local Public Finance in China’s Regional Development: Evidence from Prefecture-Level Cities. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2217–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated Restructuring in Rural China Fueled by ‘Increasing vs. Decreasing Balance’ Land-use Policy for Dealing with Hollowed Villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, Y.; Ma, W.; Gao, S. Does Participation in Poverty Alleviation programmes Increase Subjective Well-being? Results from a Survey of Rural Residents in Shanxi, China. Habitat Int. 2021, 118, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. What Constrains Impoverished Rural Regions: A Case Study of Henan Province in Central China. Habitat Int. 2022, 119, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Exploring the Outflow of Population from Poor Areas and its Main Influencing Factors. Habitat Int. 2020, 99, 102161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Meng, Q.; Chen, L.; Bekedam, H.; Evans, T.; Whitehead, M. Tackling the Challenges to Health Equity in China. Lancet 2008, 372, 493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhu, T.T. How Does Air Pollution Affect Urban Innovation Capability? Evidence from 281 Cities in China. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2022, 61, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gu, C.; Wu, F. Urban Poverty in the Transitional Economy: A Case of Nanjing, China. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Land Development, Inequality and Urban Villages in China. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2009, 33, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X. Research Progress and Comment on “Urban Problems”. J. Cap. Univ. Econ. Bus. 2012, 14, 101–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. An International Comparative Study of Urban Problem Management—Reflections on Low Carbon Development in Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zeng, J. The Impact of Urban Characteristics and Residents’ Income on Commuting in China. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2017, 57, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Storper, M. Regions, Globalization, Development. Reg. Stud. 2003, 37, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A. Capitalism and Urbanization in a New Key? The Cognitive-Cultural Dimension. Soc. Forces 2007, 85, 1465–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A. Emerging Cities of the Third Wave. City 2011, 15, 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A. Beyond the Creative City: Cognitive–Cultural Capitalism and the New Urbanism. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Thun, E. The Fight for the Middle: Upgrading, Competition, and Industrial Development in China. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1555–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Government of Zhejiang Province. Guiding Opinions of the People’s Government of Zhejiang Province on Speeding up the Planning and Construction of the Characteristic Town; Government Document; People’s Government of Zhejiang Province: Hangzhou, China, 2015. (In Chinese)

- Zou, Y.; Zhao, W. Searching for a New Dynamic of Industrialization and Urbanization: Anatomy of China’s Characteristic Town Program. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Hui, E.C. Development of Characteristic Towns in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.T.; Phelps, N.A. ‘Featured Town’ Fever: The Anatomy of a Concept and its Elevation to National Policy in China. Habitat Int. 2019, 87, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, W.; Miao, J.T. Think Locally, Act Locally: A Critique of China’s Specialty Town Program in Practice. Geogr. Rev. 2021, 111, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wu, Q.; Xu, W.; Li, Y. Specialty Towns in China: Towards a Typological Policy Approach. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay, D. Diverging Community Responses to State-led Urban Renewal in the Context of Recentralization of Planning Authority: An Analysis of Three Urban Renewal Projects in Turkey. Habitat Int. 2019, 91, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, J.C.; Fox, K.R.; Lawlor, D.A.; Trayers, T. Residents’ Diverse Perspectives of the Impact of Neighbourhood Renewal on Quality of Life and Physical Activity Engagement: Improvements but Unresolved Issues. Health Place 2011, 17, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Jiang, W.; Fertner, C.; Andersen, L.M.; Vejre, H. Understanding the Change in the Social Networks of Residential Groups Affected by Urban Renewal. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 98, 106970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Hall, M.C.M.; Ryan, C. Overtourism, Residents and Iranian Rural Villages: Voices from a Developing Country. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, E.; Elander, I. Sustainability Potential of a Redevelopment Initiative in Swedish Public Housing: The Ambiguous Role of Residents’ Participation and Place Identity. Prog. Plann. 2016, 103, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahler, S.; Harrison, C. ‘Wipe out the Entire Slum Area’: University-led Urban Renewal in Columbia, South Carolina, 1950–1985. J. Hist. Geogr. 2020, 67, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lager, D.; Van Hoven, B.; Huigen, P.P. Dealing with Change in Old Age: Negotiating Working-class Belonging in a Neighbourhood in the Process of Urban Renewal in the Netherlands. Geoforum 2013, 50, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipanah, R.; Malmusi, D.; Muntaner, C.; Borrell, C. An Evaluation of an Urban Renewal Program and Its Effects on Neighborhood Resident’s Overall Wellbeing using Concept Mapping. Health Place 2013, 23, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivarathan, A.; Jørgensen, T.S.H.; Lund, R.; Nygaard, S.S.; Kristiansen, M. ‘They are Breaking us into Pieces’: A Longitudinal Multi-method Study on Urban Regeneration and Place-based Social Relations among Social Housing Residents in Denmark. Health Place 2023, 79, 102965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Gong, X.; Liu, M. Residents’ Behavioral Intention to Participate in Neighborhood Micro-renewal based on an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior: A case study in Shanghai, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 129, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Zhong, W.; Zeng, G.; Wang, S. The Reshaping of Social Relations: Resettled Rural Residents in Zhenjiang, China. Cities 2017, 60, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikargae, M.H.; Woldearegay, A.G.; Skjerdal, T. Assessing the Roles of Stakeholders in Community Projects on Environmental Security and Livelihood of Impoverished Rural Society: A Nongovernmental Organization Implementation Strategy in Focus. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Xia, N.; Ni, W. Critical Success Factors for the Management of Public Participation in Urban Renewal Projects: Perspectives from Governments and the Public in China. J Urban Plan Dev. 2018, 144, 04018026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mohabir, N.; Ma, R.; Wu, L.; Chen, M. Whose Village? Stakeholder Interests in the Urban Renewal of Hubei Old Village in Shenzhen. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Du, J. Towards Sustainable Urban Transition: A Critical Review of Strategies and Policies of Urban Village Renewal in Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Yao, X.; Wen, F. The Urban Regeneration Engine Model: An Analytical Framework and Case Study of the Renewal of Old Communities. Land Use Policy 2022, 108, 105571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Government of Zhejiang Province. Zhejiang Provincial Government Work Report 2015; Government Document; People’s Government of Zhejiang Province: Hangzhou, China, 2015. (In Chinese)

- Bellandi, M.; Lombardi, S. Specialized Markets and Chinese Industrial Clusters: The Experience of Zhejiang Province. China Econ. Rev. 2012, 23, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Lv, X.; Cong, H. The Spatial Distribution of Industries: From “Massive Economic” to Industrial Cluster. In Transition of the Yangtze River Delta; Liu, Z., Liu, X., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.D. Beyond the GPN–New Regionalism Divide in China: Restructuring the Clothing Industry, Remaking the Wenzhou Model. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B 2011, 93, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W. Industrialization-Industrial Agglomeration and Institutional Evolution: Rethinking the Zhejiang Model. Soc. Sci. Front. 2011, 1, 46–53. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2011&filename=SHZX201101009&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=XOIo54Hv8ZnhVENhK9bUDXiYEk_Nod5Sa_pKUUloWg8WiqjEb6cVfPTAq0b18uJ0 (accessed on 17 January 2022). (In Chinese).

- Wei, S.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X. From “made in China” to “innovated in China”: Necessity, Prospect, and Challenges. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Boelens, L.; Hua, C. How Can China Achieve Economic Transition with the Featured Town Concept? A Case Study of Hangzhou from an Evolutionary Perspective. Urban Policy Res. 2020, 38, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Characteristic Town is a Strategic Choice for Zhejiang’s Innovative Development. China Econ. Trade. Her. 2016, 4, 10–13. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2016&filename=ZJMD201604005&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=Rv0yqPkJT-XHxjK0hGFYcBdGlNf6JUVFP2IJ4m7Tj5cOwjujZszyy08L7lxgZBA5 (accessed on 18 January 2022). (In Chinese).

- Ma, L.J. Urban Transformation in China, 1949–2000: A Review and Research Agenda. Environ. Plan A 2002, 34, 1545–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, J.; Yun, J. The Chinese Dream and Zhejiang’s Practice--General Report Volume, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.; Theodore, N. Fast Policy: Experimental Statecraft at the Thresholds of Neoliberalism; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development; National Development and Reform Commission; Ministry of Finance. Notice on Carrying out the Cultivation of the Characteristic Town; Government Document; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, National Development and Reform Commission and Ministry of Finance: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese)

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on the General Office of the State Council forwarded the Opinions on Promoting the Standardized and Healthy Development of Characteristic Towns from the National Development and Reform Commission; Government Document; State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020. (In Chinese)

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Approaches; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of People’s Republic of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2021; Government Document; National Bureau of Statistics of People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- National Bureau of Statistics of People’s Republic of China. The Seventh National Census; Government Document; National Bureau of Statistics of People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

| Categories | Date | Code | Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government officials | 15 December 2021 | G1 | Deputy Director of Management Committee of Hangzhou West Science and Technology Innovation Corridor, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province |

| 22 December 2021 | G2 | Section Chief of Small Town Section, Investment Promotion Bureau, Management Committee of Hangzhou Future Science and Technology City, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 29 December 2021 | G3 | Deputy Director of Urban Construction Management Office of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 30 December 2021 | G4 | Director of Regional Development Office of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 30 December 2021 | G5 | Chief of Beautiful Town Section, Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| Planners and designers | 17 December 2021 | P1 | Planner of Zhejiang South Architectural Design Co., Ltd. |

| 22 December 2021 | P2 | Planner of Planning and Construction Bureau, Management Committee of Hangzhou Future Science and Technology City, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 22 December 2021 | P3 | Planner of Planning and Construction Bureau, Management Committee of Hangzhou Future Science and Technology City, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| Scholars | 14 December 2021 | S1 | Professor of Department of Urban and Rural Planning, School of Design and Architecture, Zhejiang University of Technology |

| 18 December 2021 | S2 | Professor of the Department of Urban and Rural Planning, School of Design and Architecture, and Dean of the School of Design and Architecture, Zhejiang University of Technology | |

| 19 April 2022 | S3 | Associate Professor of the Department of Human Geography and Urban and Rural Planning, School of Geography, Nanjing Normal University | |

| Developers | 10 December 2021 | D1 | Regional Executive General Manager of Bluetown Construction Management Group Co., Ltd. |

| 24 December 2021 | D1 | Regional Executive General Manager of Bluetown Construction Management Group Co., Ltd. | |

| 2 March 2022 | D2 | Manager of Investment Department of Hangzhou Zhijiang Operation Management Group Co., Ltd. | |

| Residents | 9 December 2021 | R1 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province |

| 13 December 2021 | R2 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 13 December 2021 | R3 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 13 December 2021 | R4 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 13 December 2021 | R5 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 13 December 2021 | R6 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 13 December 2021 | R7 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 26 December 2021 | R8 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 26 December 2021 | R9 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 4 March 2022 | R10 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 4 March 2022 | R11 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 7 March 2022 | R12 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 9 March 2022 | R13 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 9 March 2022 | R14 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 10 March 2022 | R15 | Resident of Zhuantang Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 10 March 2022 | R16 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province | |

| 25 March 2022 | R17 | Resident of Cangqian Sub-district, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Kidokoro, T.; Seta, F.; Wang, Z. Are Local Residents Benefiting from the Latest Urbanization Dynamic in China? China’s Characteristic Town Strategy from a Resident Perspective: Evidence from Two Cases in Hangzhou. Land 2023, 12, 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020510

Yang Y, Kidokoro T, Seta F, Wang Z. Are Local Residents Benefiting from the Latest Urbanization Dynamic in China? China’s Characteristic Town Strategy from a Resident Perspective: Evidence from Two Cases in Hangzhou. Land. 2023; 12(2):510. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020510

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yi, Tetsuo Kidokoro, Fumihiko Seta, and Ziyi Wang. 2023. "Are Local Residents Benefiting from the Latest Urbanization Dynamic in China? China’s Characteristic Town Strategy from a Resident Perspective: Evidence from Two Cases in Hangzhou" Land 12, no. 2: 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020510

APA StyleYang, Y., Kidokoro, T., Seta, F., & Wang, Z. (2023). Are Local Residents Benefiting from the Latest Urbanization Dynamic in China? China’s Characteristic Town Strategy from a Resident Perspective: Evidence from Two Cases in Hangzhou. Land, 12(2), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020510