From Urban Challenges to “ClimaEquitable” Opportunities: Enhancing Resilience with Urban Welfare

Abstract

:1. The New Urban Question: Between Socioeconomic and Environmental Challenges

1.1. Programmatic Measures Introduced by the EU

1.2. “Right to the Public City” and Urban Welfare

- Analyzing the indicators used to determine the ranking, distinguishing between socioeconomic and environmental indicators (considering the outlined thematic framework).

- Verifying the existence, within the local urban plans of the analyzed cities, of specific strategies that may have positively influenced the aforementioned indicators.

2. Literature Review

- Land use and transport planning;

- Social services;

- Economic regeneration;

- Integrated transportation;

- Integrated planning of resources for energy, water, food, waste, etc.

2.1. The International Context: The Global Liveability Index (2022)

2.2. The Italian National Context: 33rd Survey on Quality of Life (2022)

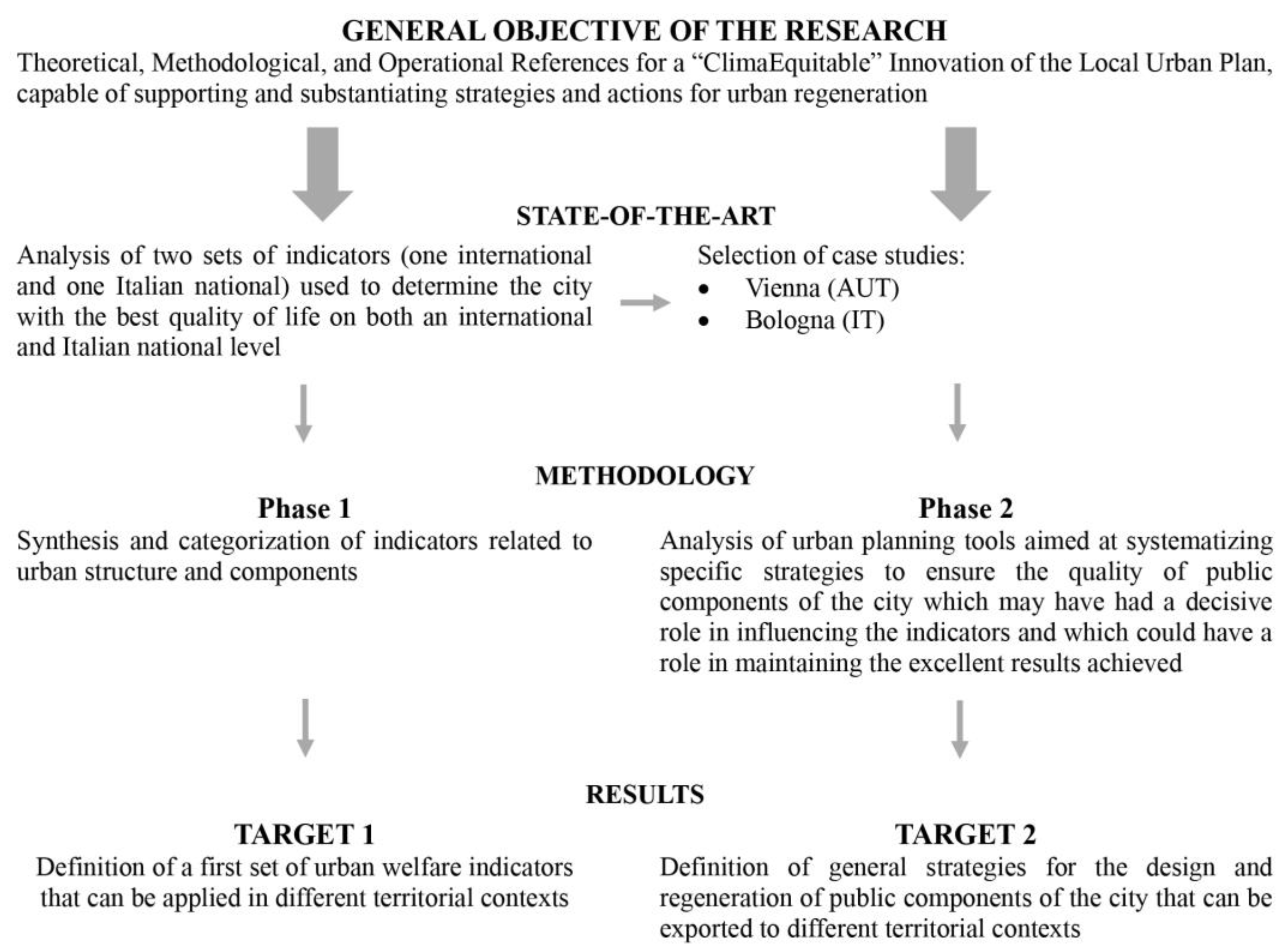

3. Methodology

- Definition of an initial set of urban welfare indicators—exportable to different territorial contexts—to assess the quality of components of the city (primarily public ones) and how they impact the well-being of settled inhabitants.

- Definition of general strategies for the planning, designing, and regenerating of these components, also exportable to different territorial contexts.

- Phase 1|Synthesis and categorization of only the indicators referring to urban structure and components, adapted from the two datasets referenced in Section 2.1 and Section 2.2.

- Phase 2|Analysis of the structure of local plans of the analyzed cities to bring out elements useful for defining strategies for the planning, designing, and regenerating urban components—primarily public ones.

3.1. Phase 1|Synthesis and Categorization of Indicators Related to Urban Structure and Components

3.2. Phase 2|Analysis of the Local Urban Plans of Vienna and Bologna

3.2.1. Vienna–SPTEP 2025

- Housing: great attention is paid to the provision of subsidized housing and social mix.

- Green and open spaces: significant focus on the “undeveloped” space of the city, understood as public space (including the road network) and green areas.

- Mobility: public mobility is understood as the backbone of the city—great attention is paid to green and cycle-pedestrian mobility.

- Vienna: setting the stage, which defines the vision of the Plan.

- Vienna: building the future, which provides general guidelines for the quality of the urban structure.

- Vienna: reaching beyond its borders, in which the terms of urban development are defined from the perspective of a regional metropolis.

- Vienna: networking the city, which outlines the principles related to mobility, social infrastructure, public spaces, and green areas.

3.2.2. Bologna–PUG 2021

- Quality of the environment.

- Quality of life.

- Quality of infrastructure.

- The location of major public interventions, either underway or already included in planning instruments.

- Opportunities and issues.

- Functional and meaningful connections.

4. Results

4.1. Target 1|Urban Welfare Indicators

4.2. Target 2|Strategies for the Planning, Design, and Regeneration of the Urban Components

5. Discussion

- Definition of a preliminary set of urban welfare indicators—exportable to different territorial contexts—to assess the quality of city components (mostly public ones) and how they impact the well-being of settled inhabitants.

- Defining some strategies for the planning, designing, and regenerating of these components, which are also exportable to different territorial contexts.

6. Conclusions

- ISTAT Dataset (2017) prepared for the Commission of Inquiry on the Degradation of Cities and Suburbs [45].

- Dataset prepared by Legambiente and Caritas Italiana for the report “Territori civili. Indicators, maps, and best practices towards integral ecology” (2020) [46].

- Statistical measures for monitoring the SDGs at the regional level [47].

- BES Report (2021) [48].

- Implementation of both urban welfare indicators and strategies through the definition of specific criteria/parameters for the planning, design, and regeneration of urban components with a climate-equitable approach;

- Validation and verification of urban welfare indicators in disadvantaged contexts and the application of criteria to delineate site-specific and climate-equitable urban regeneration interventions.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Quali-quantitative parameters: The “parterre street” and the “common room” | |

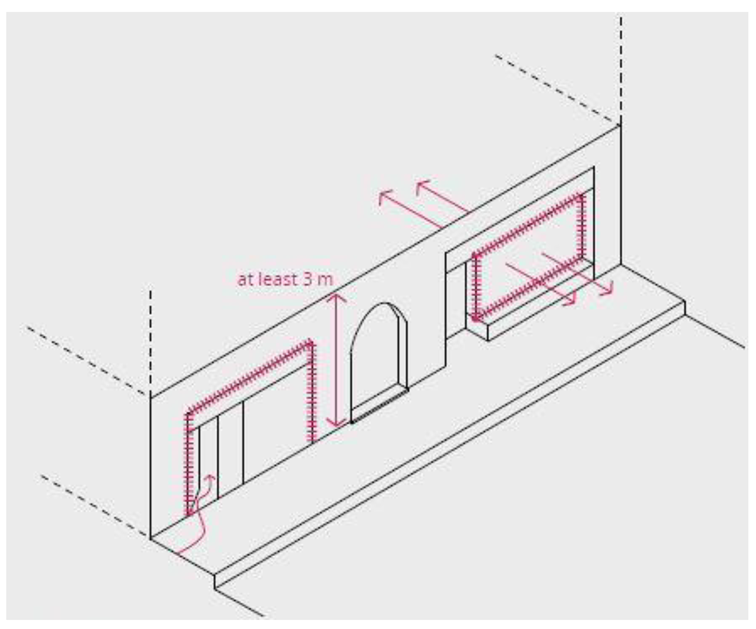

The Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018) highlights two fundamental characteristics that the public and semi-public spaces of Vienna’s historic and consolidated city should incorporate in order to ensure urban quality:

| |

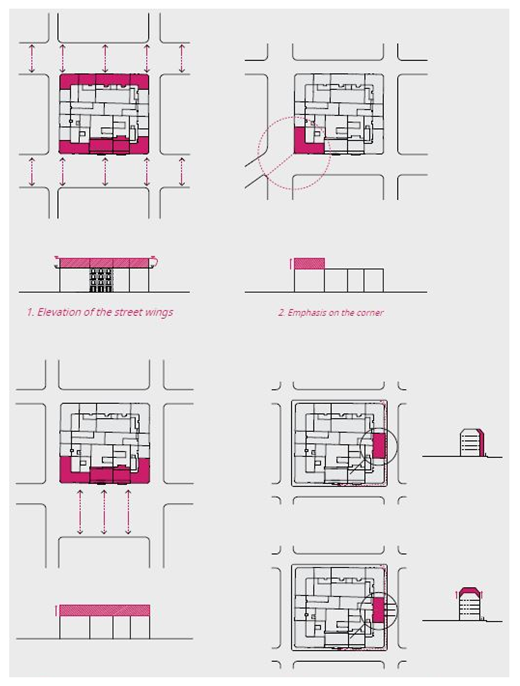

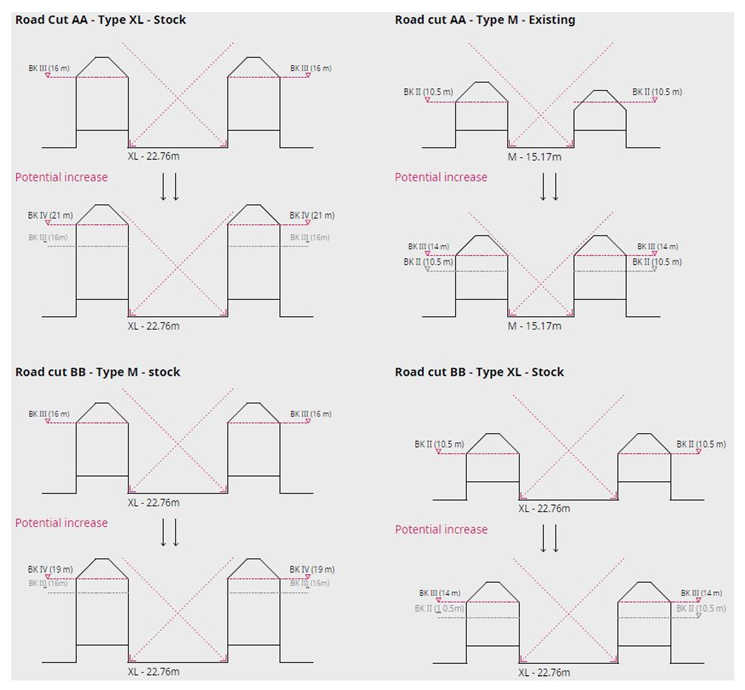

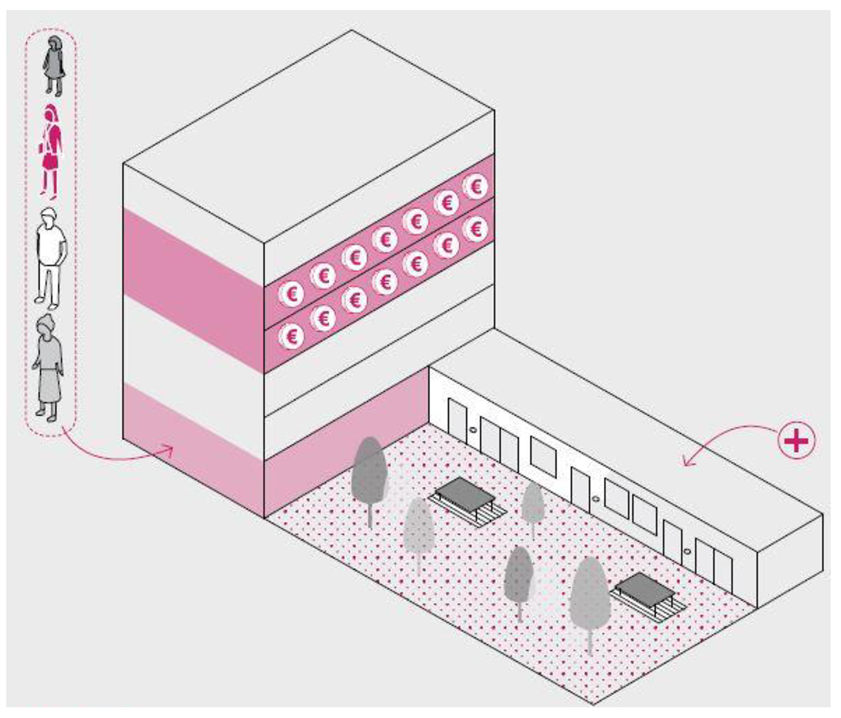

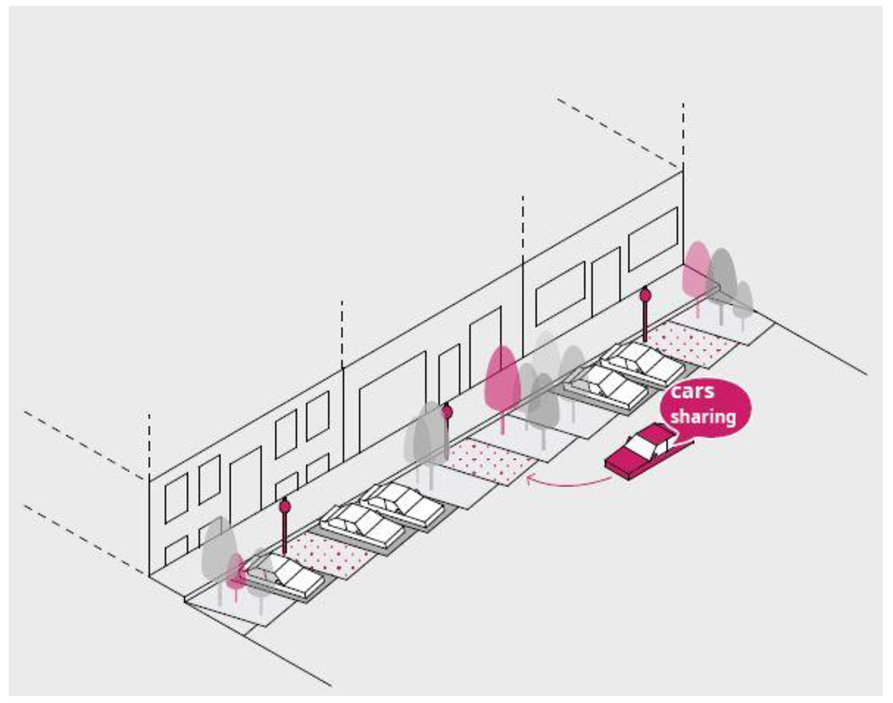

| The “parterre street” | |

| It has been verified that the heights of the buildings comprising a “Superblock” (morphological configuration of the districts in Vienna’s historic and consolidated city) are all equal and not proportionate to the width of the street each one faces. For this reason, the plan provides precise indications regarding the possibility of elevation (Parameter 1) in relation to the width of the streets on which the buildings face, differentiating, in this way, the street fronts proportionally, with particular emphasis on the corners (only those facing squares or public spaces that are intended to be emphasized) (Figure A and B). In the elevation process, the social mix is taken into account, providing for certain housing units and rent control prices (the private sector is encouraged in this practice through volumetric bonuses or through the possibility of changing land use). There is also the possibility of integrating new social housing buildings into the existing fabric (Figure C).Furthermore, in the characterization of high-quality public space, mobility plays a fundamental role (Parameter 2); therefore, STEP 2025, in general, and the Gründerzeit Action Plan in particular, place great emphasis not only on concepts of alternative mobility—such as, for example, car sharing (Figure D)—but also on a hierarchy of flows in urban regeneration interventions, envisioning green and slow mobility within the superblock (woonerf model) and a drivable one between one superblock and another (Figure E). | |

| Parameter 1: Building Upward | |

|  |

| Figure A. Possible building upward in relation to the road width. Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). | Figure B. Indications relating to possible building upward. Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). |

| Description of Figure A: This action allows for the possibility of adding extra floors to the buildings that make up the perimeter of the superblock. The aim is to meet the increasing demand for housing while ensuring urban quality (and thus managing the transformation) and preserving social diversity within the same residential building. The action provides four possibilities for adding extra floors based on the building/public space relationship:

| Description of Figure B: The image provides a detailed description of the possibility of adding extra floors, quantifying it in relation to the width of the street on which the building faces:

|

| Description of Figure C: Due to the increasing demand for housing, there is a growing trend of buying and constructing apartments for investment purposes. This trend negatively impacts the social mix within residential buildings. Therefore, if a building undergoes actions aimed at improving the quality and value of its apartments (such as through increased volume or changes in use), it is suggested that a portion of the apartments be offered at controlled rental prices. The possibility of establishing agreements in this regard with social associations or organizations is also envisaged. Additionally, where possible, there should be provisions for integrating new constructions with dedicated units for socioeconomically vulnerable groups or those in need. Furthermore, for new constructions, a minimum quota of social housing should be considered in relation to the size of the project. |

| Figure C. Social mixitè through the integration of housing at controlled prices in buildings used for private residences and the combination of new social housing structures with buildings used for private residences. Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). | |

| Parameter 2: Mobility | |

|  |

| Figure D. Integration of alternative mobility models in public space. Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). | Figure E. Woonerf. Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). |

| Description of Figure D: Alternative mobility measures (such as car sharing) have a dual benefit: on the one hand, they have a lower impact in terms of pollution, and on the other, they lead to a reduction in parking spaces, allowing for increased space for pedestrians and bike lanes. Encouraging a form of condominium or neighborhood car sharing is also recommended. Furthermore, a reduction in parking spaces is planned, with the number of spaces being reduced based on the number of units per individual building. Exceptions may be made as a form of compensation for the creation of additional quality. | Description of Figure E: The extension of the restricted traffic zone is planned for secondary streets (inside the superblock), where the concept of a “woonerf” can be implemented. |

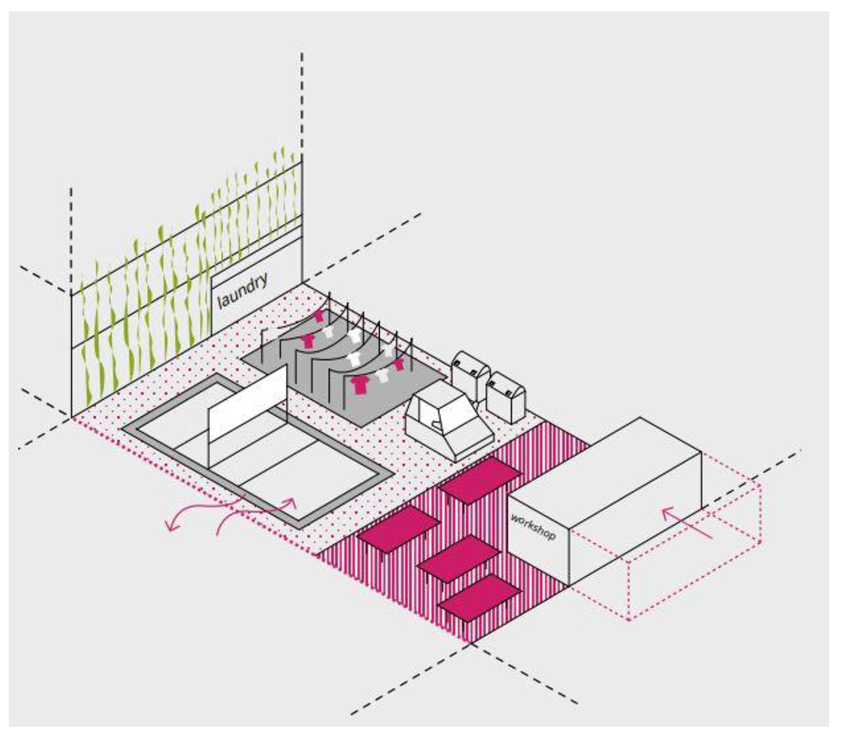

| Public and semi-public space as a “common room” | |

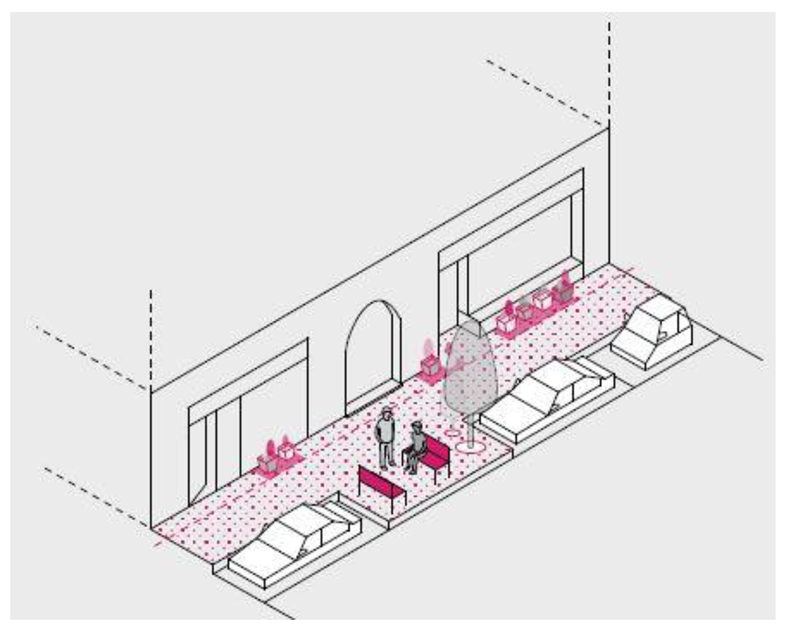

| Another aspect to consider in order to ensure a quality public space is the function of the ground floor of buildings (Figure F). This is considered particularly important because it influences both the space in front (public space) and the inner courtyard of the building block (semi-public space). In this sense, the ground floor of buildings in the Gründerzeit area should accommodate functions related to the building, such as bicycle parking (to free up the backyard) and commercial functions (Parameter 1). Furthermore, the emphasis that the Vienna city administration puts on the role of private individuals in managing the public space in front of their property is particularly relevant. This should include the possibility of a social and shared use of the sidewalk (Figure G). As for the semi-public space (backyard), great importance is attributed to its potential role in social aggregation aimed at strengthening neighborly relations. To this end, Parameter 2 is aimed at avoiding privatization initiatives and encouraging the shared use of spaces (Figure H). | |

| Parameter 1: Social and Shared Use of the Sidewalk | |

|  |

| Figure F. Guidelines for the design and refunctionalization of the ground floor of buildings. Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). | Figure G. Suggestions for the regeneration of public space facing the street (parklet). Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). |

| Description of Figure F: In addition to contributing to the social use of the sidewalk as a common and shared space, the function of the ground floor also plays a fundamental role in the criterion of the “street parterre.” To this end, for new constructions, it will be necessary for the spaces located on the ground floor to have a minimum height of 3 m in order to promote the social use of the spaces, such as playrooms, playgrounds, and commercial functions. Currently, the low heights of these spaces favor secondary uses, such as storage and garages, which do not encourage positive interaction with the public space in front. It is also desirable to provide for a flexible use of the ground floor premises, including through the design of an open structure. | Description of Figure G: The use of the ground floor of buildings is also connected to the management of the public space in front. The Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018) encourages private individuals to take responsibility for the care, maintenance, and animation of the public space, also through initiatives like “Street Life Wien,” which aims to involve and encourage citizens to use the streets and public spaces as a “common room” [51]. |

| Parameter 2: Backyard Function as a Social Gathering Space | |

| Description of Figure H: In order to promote the use of semi-public spaces as a “common room,” the regeneration of these spaces is encouraged by clearing them of bicycles and recycling bins (for example, by allocating some ground floor areas for this purpose) and by promoting common and shared activities such as laundry, workshops, and playgrounds. For new constructions, it is preferable to limit vertical partitions in order to favor spacious and shared areas. |

| Figure H. Suggestions for the regeneration of semi-public space within the building blocks (backyard). Source: Gründerzeit Action Plan (2018). | |

Appendix B

| Objectives | Urban Strategies | Actions | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience and Environment | Promote the regeneration of anthropized soils and counteract soil consumption | Promoting the recovery and improvement of existing building heritage | Urbanized territory |

| Rural territory | |||

| Completing unfinished parts of the city where transformation is not complete | Incomplete city parts | ||

| Promoting interventions for the reuse and urban regeneration of built-up areas and anthropized soils | Historic city | ||

| Planned parts with implementing urban planning tool | |||

| City parts under construction | |||

| Including measures for the de-sealing and de-pavement of soils | Municipal territory | ||

| River areas | |||

| Develop the urban eco network | Protect biodiversity and the main ecosystem services of the hills and plains | Hill rural territory | |

| Plain rural territory | |||

| Strengthen urban green infrastructure | Urbanized territory perimeter | ||

| Building a blue urban infrastructure | Municipal territory | ||

| Bodies of water in major basins | |||

| Active riverbeds and bodies of water in basins | |||

| Maintain natural flows in the riverbed and reduce withdrawals from aquifers | Municipal territory | ||

| Primary non-potable water networks | |||

| Improve the quality of surface waters | Channels to be restored-areas 20 m away | ||

| Minor hydrographic network areas 50 m away | |||

| Covered network areas 100 m away | |||

| Municipal territory | |||

| Prevent and mitigate environmental risks | Contain natural risks | Areas in distress | |

| Areas of possible evolution and influence of distress | |||

| Areas with an inclination for territorial transformation | |||

| Ensure regular drainage of water in the entrances of streams and covered ditches | Inlets of hillside streams and culverted hillside ditches/upstream area | ||

| Inlets of hillside streams and culverted hillside ditches/first 150 m from the upstream area | |||

| Mitigate the urban heat island effect | Areas of microclimatic fragility | ||

| Reduce the population’s exposure to pollution and anthropogenic risks | Municipal territory | ||

| Areas with high noise pollution/areas facing the main infrastructures | |||

| Areas with high noise pollution/areas underlying the nominal routes | |||

| Support the energy transition and circular economy processes | Promote and incentivize various forms of energy efficiency and ensure equitable access to low environmental impact energy services. | Municipal territory | |

| Plan the deployment of energy production facilities from renewable sources by creating local distribution networks. | Municipal territory | ||

| Promote the circular economy of construction and excavation materials. | Municipal territory | ||

| Increase recycling and reduce waste production | Municipal territory | ||

| Collection and reuse centers for urban waste-first 100 m | |||

| Habitability and inclusion | Extend access to the house | Promote the increase and innovation of rental housing supply | Urbanized territory |

| Promote the increase of social housing supply. | Areas where to increase the supply of ERS | ||

| Experiment with new forms of housing. | Municipal territory | ||

| Introduce functional and typological mixes in specialized areas near residential fabrics. | Specialized areas near residential fabrics | ||

| Ensure the creation of a balanced network of quality equipment and services | Promote the redevelopment and establishment of territorial amenities | Areas at risk of social marginality | |

| Municipal territory | |||

| Support a balanced distribution of spaces for culture | Perimeter of the urbanized territory | ||

| Foster local services and commercial activities | Municipal territory | ||

| Perimeter of the urbanized territory | |||

| Promote sustainable urban logistics | Municipal territory | ||

| Perimeter of the urbanized territory | |||

| Redesign spaces and equipment | Make the city universally accessible | Municipal territory | |

| Create open spaces and public buildings of high architectural and environmental quality | Areas at risk of social marginality | ||

| Perimeter of the urbanized territory | |||

| Renew the street space in terms of formal and environmental quality, accessibility, and safety | Municipal territory | ||

| Accessibility to the backbone network of local public transport | |||

| Preserve the characteristics of the historic urban landscape by renewing its role | Preserve the habitability and characteristics of the historic city | Fabrics of the historic city-nucleus of ancient formation | |

| Fabrics of the historic city-garden neighborhoods | |||

| Fabrics of the historic city-compact fabric | |||

| Buildings without particular interest in the fabrics of the historic city (ES) | |||

| Buildings facing Via dell’Indipendenza, Via Ugo Bassi, and Via Rizzoli | |||

| Enhance the specialized fabrics of the historic city | Fabrics of the historic city-specialized | ||

| Ensure the conservation of the architectural and cultural heritage of historical significance | Point elements of interest | ||

| Arcades | |||

| Parks of historical interest | |||

| Historical and urbanistic relevance | |||

| Buildings of cultural and testimonial interest | |||

| Buildings of historical and architectural interest | |||

| Buildings of historical and architectural interest of the Modern era | |||

| Enhance the architecture and cultural and testimonial agglomerates of the Second Half of the Twentieth Century | Agglomerations of cultural and testimonial interest of the Second Twentieth Century | ||

| Buildings of interest and pertinence—buildings of cultural and testimonial interest of the Second Twentieth Century | |||

| Attractiveness and work | Support overall urban reinfrastructure | Reconstruct the unified map of infrastructure networks, nodes, intersections, and managers | Urbanized territory |

| Ensure the improvement of urban infrastructure with urban and building transformation interventions | Perimeter of the urbanized territory | ||

| Promote the distribution and coordination of digital infrastructure | Perimeter of the urbanized territory | ||

| Qualify the role and visibility of the city’s access gates and create a system of mobility centers | Mobility centers and priority areas of metropolitan urban regeneration | ||

| City access gates | |||

| Improve the functionality of the highway-ring road system, mitigating impacts and redeveloping contact areas with the city | Areas affected by the enhancement project within the highway-ring road system | ||

| Highway-ring road system areas 100 m away | |||

| Build the urban tram network | Urbanized territory | ||

| Extend and integrate the backbone of the urban and extra-urban cycling network | Municipal territory | ||

| Promote the widespread establishment of economic activities in conditions of environmental compatibility | Ensure existing businesses have regulatory and procedural flexibility | Urbanized territory | |

| Identify new production needs, directing them toward the reuse and regeneration of urbanized areas | Planned production areas | ||

| Perimeter of urbanized territory | |||

| Promote innovation in planned production areas through the diversification of uses | Planned production areas | ||

| Foster the establishment of innovative companies and the promotion of innovation centers | Areas near innovation centers | ||

| Technopole | |||

| Perimeter of urbanized territory | |||

| Support the qualification of metropolitan hubs integrated into living places inserted in the context | Bologna Guglielmo Marconi Airport: support a development that is mindful of its relationship with the city | Bologna Guglielmo Marconi Airport | |

| Bologna Centrale Railway Station and Bologna Bus Station: integrate access, transit, and parking areas with quality urban functions | Bologna Central Railway Station and Bus Station | ||

| University of Bologna-Alma Mater Studiorum: enhance and connect the campus facilities | Campus of Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna | ||

| Healthcare Centers of Excellence: support the process of adapting facilities to social and environmental changes, improving accessibility conditions | Centers of excellence in healthcare | ||

| Bologna Trade Fair: develop the multifunctionality of the hub, improving access methods at different scales | Bologna Fair | ||

| Renato Dall’Ara Stadium: regenerate the facility and its relationships with the city | Renato Dall’Ara Stadium | ||

| North-East District (CAAB, FICo Eataly World, Meraville, Business Park, University): integrate components and implement new infrastructure for access | Northeast District | ||

| Qualify the relationship between urban territory and extra-urban territory | Promote innovative practices of peri-urban agriculture | Hillside rural territory | |

| Plain rural territory | |||

| Enhance peri-urban parks, improving their usability for tourism | Periurban parks | ||

| Develop networks of safe routes and paths connected to national and European tourist itineraries | Cycling and pedestrian tourist routes | ||

| Hiking trails | |||

| Hillside rural territory | |||

| Plain rural territory |

References

- Castells, M. The Urban Question a Marxist Approach; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Donzelot, J. Quand la Ville se Défait. Quelle Politique Face à la Crise des Banlieues? Points: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mimar, S.; Soriano-Paños, D.; Kirkley, A.; Barbosa, H.; Sadilek, A.; Arenas, A.; Gómez-Gardeñes, J.; Ghoshal, G. Connecting intercity mobility with urban welfare. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indovina, F. Metropoli territoriale e sviluppo economico-sociale. In Economia e Società Regionale; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Indovina, F. Dalla Città Diffusa All’arcipelago Metropolitano; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Indovina, F. La Città diffusa. In La Città Diffusa; Indovina, F., Matassoni, F., Savino, M., Sernini, M., Torres, M., Vettoretto, L., Eds.; Daest-IUAV: Venezia, Italy, 1990; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M.; Rizzo, C. Città Delle Reti; Marsilio: Padova, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Augè, M. Non-Lieux: Introduction à une Anthropologie de la Surmodernité; Seuil: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Francesco, P. Laudato Si’: Enciclica sulla cura della casa Comune; Libreria editrice Vaticana: Città del Vaticano, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, L. Nuova questione urbana e nuovo welfare. Una rete di reti per la costruzione della città pubblica. In Città Pubblica e Nuovo Welfare. Una Rete di Reti Per la Rigenerazione Urbana; Ricci, L., Crupi, F., Iacomoni, A., Mariano, C., Eds.; Urbanistica Dossier: Roma, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, J.; Hildingsson, R.; Garting, L. Sustainable Welfare in Swedish Cities: Challenges of Eco-Social Integration in Urban Sustainability Governance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. Strategy for Sustainability Management in the United Nations System, 2020–2030 Phase II: Towards Leadership in Environmental and Social Sustainability. 2021. Available online: https://unsceb.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/CEB.2021.2.Add_.1-Strategy%20for%20Sustainability%20Management%20in%20the%20United%20Nations.Phase%20II.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- United Nation. A Framework for Advancing Environmental and Social Sustainability in the United Nations System. 2012. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2738sustainabilityfinalweb-.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- United Nation. Framework for Advancing Environmental and Social Sustainability in the UN System. 2016. Available online: https://unemg.org/images/emgdocs/sustainabilitymanagement/Synthesis_report_shortened_June2016.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- COM. Urban Agenda for the EU Pact of Amsterdam. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/urban-development/agenda/pact-of-amsterdam.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- COM. The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- COM. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions a Strong Social Europe for Just Transitions. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:e8c76c67-37a0-11ea-ba6e-01aa75ed71a1.0003.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- COM. Overview of Investment Guidance on the just Transition Fund 2021–2027 per Memeber State. 2020. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2020-02/annex_d_crs_2020_en.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- COM. New European Bauhaus. Beautiful, Sustainable, Together. 2021. Available online: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/system/files/2021-09/COM(2021)_573_EN_ACT.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- ASVIS. Agenda Urbana Per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. 2017. Available online: https://asvis.it/public/asvis/files/AgendaUrbana.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- PNRR. Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza. 2021. Available online: https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Lefebvre, H. Right to the City; Ombre Corte: Verona, Italy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, L. Città pubblica e Nuovo Welfare. Una rete di reti per la Rigenerazione Urbana. Ananke 92 (Torino, Italy) 2021, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Caldarice, O. Urban Welfare in Italy: From Urban Standards to Urban Facilities. In Reconsidering Welfare Policies in Times of Crisis; Caldarice, O., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio, R.; Trusiani, E. Città Salute e Benessere; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Salvo, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.L.; et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M. A health map for the local human habitat. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, L.; Mariano, C.; Marino, M. Well-Being Cities and Territorial Government Tools: Relationships and Interdependencies; LNCE Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Allegato Statistico Per la Commissione Parlamentare di Inchiesta Sulle Condizioni di Sicurezza e Sullo Stato di Degrado Delle Città e Delle Loro Periferie. 2017. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/202052 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Legambiente e Caritas italiana. Territori Civili. Indicatori, Mappe e Buone Pratiche verso L’ecologia Integrale; Edizioni Palumbi: Teramo, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Indicatori SDGs. 2022. Available online: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/istat.istituto.nazionale.di.statistica/viz/SDGs_public_ottobre_2022/SDGs?publish=yes (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Istat. Rapporto BES 2021: Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia. 2021. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/269316 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- EIU. The Global Liveability Index 2022. In Recovery and Hardship; The Economist Group: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sole 24 Ore. 33ª Indagine Sulla Qualità Della Vita. 2022. Available online: https://lab24.ilsole24ore.com/qualita-della-vita/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- STEP 2025. Urban Development Plan Vienna; Vienna City Administration: Vienna, GA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/studien/pdf/b008379b.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Masterplan Gründerzeit. Handlungsempfehlungen zur Qualitätsorientierten. Weiterentwicklung der Gründerzeitlichen Bestandsstadt; Magistrat der Stadt Wien, MA 21—Stadtteilplanung und Flächennutzung. 2018. Available online: https://www.superblock.at/_files/ugd/5bb4e2_10129184b72f4a939212b16ed0598ef8.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- PUG Bologna. Approfondimenti Conoscitivi: Governance; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Approfondimenti Conoscitivi: Mobilità; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Approfondimenti Conoscitivi: Paesaggio; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Approfondimenti Conoscitivi: Patrimonio Abitativo; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Approfondimenti Conoscitivi: Popolazione; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Approfondimenti Conoscitivi: Servizi Alle Persone; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Approfondimenti Conoscitivi: Sistema Economico; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Strategie urbane: Abitabilità e Inclusione; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Strategie urbane: Attrattività e Lavoro; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Strategie urbane: Resilienza e Ambiente; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Strategie urbane: Generale; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PUG Bologna. Leggere il Piano; Comune di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Hu, F.; Wang, B.; Wei, C.; Sun, D.; Wang, S. Relationship between urban landscape structure and land surface temperature: Spatial hierarchy and interaction effects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yuan, B.; Hu, F.; Wei, C.; Dang, X.; Sun, D. Understanding the effects of 2D/3D urban morphology on land surface temperature based on local climate zones. Build. Environ. 2022, 208, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street Life. Available online: https://streetlife.wien/ (accessed on 8 June 2023).

| Characteristics of the Analyzed Indicator Sets | Sets of Analyzed Indicators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISTAT (2017) | “Territori civili” (Legambiente e Caritas Italiana, 2020) | SDGs Measures on a Regional Scale (Istat, 2022) | BES Report 2021 | Global Liveability Index 2022 (EIU) | 33rd Survey on Quality of Life (Sole 24 Ore, 2022) | |

| Scope of Application | Italian national, urban scale | Regional | Regional | National, urban scale | International, urban scale | National, urban scale |

| Structure | Eight reference domains with 27 specific indicators (mainly socioeconomic) | 40 social indicators and 30 environmental indicators, divided into various dimensions | Over 200 indicators defined by the Inter-Agency Expert Group on SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) Indicators | Integrated analysis of economic, social, and environmental phenomena divided into 12 domains | Five main categories with various specific indicators (both socioeconomic and environmental) | Six synthetic indicators are divided into sub-indicators (including both socioeconomic and environmental aspects) |

| Main focus | Exposure to socioeconomic vulnerabilities of the analyzed cities, with specific reference to peripheral areas. | Relationship between fragility and socioeconomic and environmental resources of Italian regions. | Monitoring progress towards Sustainable Development Goals | Evaluation of the well-being, defined as fair and sustainable, of Italian cities | Evaluation of the city with the best quality of life on a global scale. | Evaluation of the city with the best quality of life on a national scale in Italy. |

| Gen. Cat. | Impact U.S. | EIU Indicators | Indicator Typologies | System | S24O Indicators | Indicators | System | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | EN | E.S | S.S | MS.S | SE | EN | E.S | S.S | MS.S | ||||

| Social stability | Perception of public space | Presence of petty crime | ✔ | ✔ | Crime index—total number of crimes reported | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Presence of violent petty crime | ✔ | ✔ | Robberies on public streets | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Sustainable public lighting | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| Perception of fear | ✔ | ✔ | Perception of fear | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Presence of disorders | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Health care | Coverage and quality of healthcare facilities | Availability of private healthcare facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Evaluation of private healthcare facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Availability of public health facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Evaluation of public health facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Instruction | Coverage and quality of school facilities | Availability of private school facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Evaluation of private school facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Availability of public school facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Evaluation of public school facilities | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Culture and free time | Coverage and quality of cultural and leisure venues | Availability of cultural facilities/places | ✔ | ✔ | Availability of restaurants (including mobile catering) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Availability of museum heritage | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Availability of agritourism companies | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Availability of libraries | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Bar availability | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Cultural offer (shows per thousand inhabitants) | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Sport | Coverage and quality of facilities equipped for sports | Availability of sports equipment/facilities | ✔ | ✔ | Availability of gyms, swimming pools, wellness centers and spas | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Environment | Effects of climate change on urban climate | Humidity/temperature | ✔ | ✔ | Consecutive days without rain | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Perception of discomfort about the climate | ✔ | ✔ | Energy consumption | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Air quality | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Green mobility | Motorization rate (cars in circulation per 100 inhabitants) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| Pedestrian areas | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Presence of cycle paths | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Infrastructural accessibility | Mobility infrastructure | Road quality | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Quality of public transport | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| Quality of connections to and from the city | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Building heritage | Public and private residences | Availability of good quality residential accommodation | ✔ | ✔ | Average rental rates | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Average home sales price | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Living space (average surface area calculated on the basis of the average family members) | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Burglaries at home | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| Population density (residents per km2) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Legally resident immigrants | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Urban Welfare Indicators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference System | Reference Category | Impact on the Urban Structure | Indicators | Indicator Typologies | |

| SE | EN | ||||

| Environmental system | Climate change | Effects of climate change on urban climate | Humidity/Temperature | ✔ | |

| Perception of discomfort about the climate | ✔ | ||||

| Consecutive days without rain | ✔ | ||||

| Energy consumption | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Air quality | ✔ | ||||

| Sports and health | Coverage and quality of sports facilities | Availability of sports equipment/facilities | ✔ | ||

| Availability of gyms, swimming pools, wellness centers and spas | ✔ | ||||

| Settlement-morphological system | Social stability | Perception of public space | Presence of petty crime | ✔ | |

| Presence of violent petty crime | ✔ | ||||

| Crime index-total number of crimes reported | ✔ | ||||

| Robberies on public streets | ✔ | ||||

| Perception of fear | ✔ | ||||

| Sustainable public lighting | ✔ | ||||

| Presence of disorders | ✔ | ||||

| Building heritage | Public and private residences | Availability of good quality residential accommodation | ✔ | ||

| Population density (Residents per km2) | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Home burglaries | ✔ | ||||

| Average rental rates | ✔ | ||||

| Average home sales price | ✔ | ||||

| Living space (average surface area based on average family members) | ✔ | ||||

| Legal resident immigrants | ✔ | ||||

| Mobility and service system | Health care | Coverage of healthcare facilities | Availability of private healthcare facilities | ✔ | |

| Availability of public health facilities | ✔ | ||||

| Quality of healthcare facilities | Evaluation of private healthcare facilities | ✔ | |||

| Evaluation of public health structures | ✔ | ||||

| Instruction | Coverage of school facilities | Availability of private school facilities | ✔ | ||

| Availability of public school facilities | ✔ | ||||

| Quality of school facilities | Evaluation of private school facilities | ✔ | |||

| Evaluation of public school facilities | ✔ | ||||

| Culture and free time | Coverage and quality of cultural and leisure venues | Availability of cultural facilities/places | ✔ | ||

| Cultural offer (shows per thousand inhabitants) | ✔ | ||||

| Availability of sports equipment/facilities | ✔ | ||||

| Availability of restaurants (including mobile catering) | ✔ | ||||

| Availability of museum heritage | ✔ | ||||

| Availability of agritourism companies | ✔ | ||||

| Availability of libraries | ✔ | ||||

| Bar availability | ✔ | ||||

| Availability of gyms, swimming pools, wellness centers and spas | ✔ | ||||

| Infrastructural accessibility | Mobility infrastructure | Road quality | ✔ | ||

| Quality of public transport | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Quality of connections to and from the city | ✔ | ||||

| Green mobility | Coverage, quality and use of green mobility infrastructure | Pedestrian areas | ✔ | ||

| Presence of cycle paths | ✔ | ||||

| Motorization rate (Cars in circulation per 100 inhabitants) | ✔ | ||||

| Strategies for Planning, Designing, and Regenerating Urban Components (Predominantly Public) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference System | Reference Category | Impact on the Urban Structure | Strategies | Criteria/Parameter Typologies | |

| SE | EN | ||||

| Environmental system | Climate change | Effects of climate change on urban climate | Promote the recovery and upgrading of existing building heritage | ✔ | |

| Complete the parts of the city where transformation is not yet complete | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Promote reuse and urban regeneration of built areas and anthropized land | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Envision interventions for the unsealing and depavement of soil | ✔ | ||||

| Safeguard biodiversity and the main ecosystem services of hills and plains | ✔ | ||||

| Improve the quality of surface waters | ✔ | ||||

| Maintain natural watercourse flows and reduce withdrawals from groundwater | ✔ | ||||

| Enhance the quality of surface waters | ✔ | ||||

| Ensure the regular flow of water in the mouths of streams and culverts | ✔ | ||||

| Mitigate the urban heat island effect and introduce measures for building climate adaptation | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Reduce the population’s exposure to pollution and anthropogenic risks | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Promote and incentivize various forms of energy efficiency and equitable access to low-impact energy services | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Plan the deployment of energy production plants from renewable sources by creating local distribution networks | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Connection between city and countryside | Promote innovative practices in peri-urban agriculture | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Enhance peri-urban parks, improving their accessibility for tourism | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Develop networks of safe paths and trails connected to national and European tourist routes | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Settlement-morphological system | Social stability | Perception of public space | In case of elevation, ensure it is proportional to the street width | ✔ | |

| Promote practices for regenerating public space along the street (creating parklets) | ✔ | ||||

| Construct open spaces and public buildings with high architectural and environmental quality | ✔ | ||||

| Renew the street space in terms of formal and environmental quality, accessibility, and safety | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Preserve the habitability and characteristics of the historic city | ✔ | ||||

| Enhance the specialized fabrics of the historic city | ✔ | ||||

| Guarantee the conservation of architectural and cultural heritage of historical interest | ✔ | ||||

| Building heritage | Public and private residences | Promote the refunctionalization of the ground floor of buildings | ✔ | ||

| Ensure social diversity through the integration of rent-controlled housing units in buildings designated for private residences and the juxtaposition of new social housing structures with buildings designated for private residences | ✔ | ||||

| In case of elevation, ensure it is proportional to the street width | ✔ | ||||

| Promote the shared use of semi-public spaces in residential buildings (understood as a “common room”) | ✔ | ||||

| Promote the recovery and improvement of existing building heritage | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Complete the parts of the city where transformation is not yet complete | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Promote the increase and innovation of rental housing supply | ✔ | ||||

| Promote the increase of social housing supply | ✔ | ||||

| Experiment with new forms of housing | ✔ | ||||

| Introduce functional and typological mixes in specialized areas near residential fabrics | ✔ | ||||

| Mobility and service system | Culture and free time | Coverage and quality of cultural and leisure venues | Support a balanced spread of spaces for culture | ✔ | |

| Promote local services and commercial activities | ✔ | ||||

| Infrastructural accessibility | Mobility infrastructure | Implement, where possible, a hierarchical mobility system (Woonerf) | ✔ | ||

| Strengthen the rail network | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Green mobility | Coverage, quality, and use of green mobility infrastructure | Integrate alternative mobility models in public spaces (e.g., charging stations for electric cars) | ✔ | ||

| Enhance urban green infrastructure | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Create urban blue infrastructures | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Extend and integrate the main framework of the urban and extra-urban cycling network | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Relations and Interdependencies between Indicators and Criteria/Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators from Table 3 | Strategies from Table 4 | Reference System | Reference Category | Impact on the Urban Structure | Typologies | |

| SE | EN | |||||

| Perception of discomfort about the climate (EIU) and Air Quality (S24O) | Mitigate the urban heat island effect and envision interventions for the unsealing and depavement of soil | Environmental | Climate change | Effects of climate change on urban climate | ✔ | |

| Perception of fear (EIU and S24O) | Renew the street space in terms of formal and environmental quality, accessibility, and safety | Settlement-morphological | Social stability | Perception of public space | ✔ | |

| Road quality (EIU) and Presence of cycle paths (S24O) | Implement, where possible, a hierarchical mobility system (Woonerf) | Mobility | Infrastructural accessibility | Mobility infrastructure | ✔ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marino, M. From Urban Challenges to “ClimaEquitable” Opportunities: Enhancing Resilience with Urban Welfare. Land 2023, 12, 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122157

Marino M. From Urban Challenges to “ClimaEquitable” Opportunities: Enhancing Resilience with Urban Welfare. Land. 2023; 12(12):2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122157

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarino, Marsia. 2023. "From Urban Challenges to “ClimaEquitable” Opportunities: Enhancing Resilience with Urban Welfare" Land 12, no. 12: 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122157

APA StyleMarino, M. (2023). From Urban Challenges to “ClimaEquitable” Opportunities: Enhancing Resilience with Urban Welfare. Land, 12(12), 2157. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122157