The Expression of Illegal Urbanism in the Urban Morphology and Landscape: The Case of the Metropolitan Area of Seville (Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Bibliographic references: These have been used, firstly, to provide conceptual support for the research. In this area, we have searched for works that have analysed the phenomenon of illegal housing in Spain, its characterisation, territorial incidence, and other environmental and landscape effects. Additionally, other works from different spatial contexts have been used, which, although they do not directly address the urban processes that are the object of this research, are related to them in a tangential way. Specifically, research related to informal settlements characteristic of the countries of the global south or those whose object of study are the processes of urban sprawl in its different dimensions have been used.

- Statistical sources: The statistical data used for the tables in Section 3.2 come from the Population and Housing Censuses published by the National Institute of Statistics (INE) for the period from 1996 to 2021. Specifically, we have used the population figures of the different municipalities that make up the study area and contrasted them with the overall numbers for the region. The evolution and dynamism of the real estate market was based on the data on the total principal and non-principal dwellings provided by this source.

- Cartographic sources: These come from the main compendium of geographic information existing in the autonomous community of Andalusia. This is the cartographic project called the “Spatial Reference Data of Andalusia” (DERA), which is free and open-access information that offers the most complete repertoire of information layers, both in vector and raster format, on different subject areas. Those used in this research come from blocks 7 “Urban system” and 13 “Administrative boundaries”.

- Documentary sources: Firstly, only two inventories carried out by the regional administration for the analysis and diagnosis of the phenomenon of illegal housing developed in Andalusia have been handled. The first, completed in 1988 [62], was carried out individually for each of the eight Andalusian provinces; the one used in this study corresponds to Seville. The second, in turn, covers the entire regional territory in a single document and is dated 2003 [63]. Although they are unpublished works, both can be consulted in the archives of the current Department of Development, Territorial Coordination and Housing of the Regional Government of Andalusia. Secondly, to ascertain the current situation of the illegal housing developments identified by these inventories, the urban planning of each of the municipalities in the study area has been consulted.

- Field work: Inherent to the geographic discipline, the degree of spatial integration of each of the illegal housing developments identified in the study area, as well as their landscape effects, has been determined in the field. Other aspects, such as the level of urbanisation and the quality of existing public services in comparison with neighbouring areas developed through planned urban development processes, have also been analysed.

- Conceptual definition and presentation of the study area: Based on the bibliographic analysis, the metropolitan areas of the main Spanish cities have been identified as the areas in which the phenomenon of illegal housing has had a particular incidence. Seville is the main urban agglomeration in the autonomous community of Andalusia and is the fourth largest in the country in terms of demographic size. In addition, its peripheral geographic position, both in relation to Spain as a whole and to the rest of Europe, gives it specific dynamics. The analysis of the internal configuration process, together with the demographic and urban development dynamics as well as the incidence of the phenomenon of illegal housing, have led to the choice of the central sector of the first metropolitan area of the Aljarafe region as the ideal place for its in-depth analysis.

- Characterisation of illegal housing developments: In the first inventory, that of 1988, there is an individualised file for each illegal housing development that contains, among other information, the UTM coordinates with a precision of 1 km from the centroid of the area, as well as a detailed cartography at a scale of 1:10,000. Since there is no vectorised information, it has been necessary to create a database with this information to georeference each illegal housing development. Subsequently, using the orthophotography of the 1980s, contemporary to the preparation of the inventory, as a cartographic base, and having identified each housing development from the point that locates the centroid, we proceeded to digitise each one of them; in total, 25 areas were digitised. For those identified in the 2003 inventory, the georeferenced information was available in vector format and could therefore be entered directly into the geographic information system.

- Urban analysis: Once all the areas had been identified, the urban planning of each municipality was consulted to check how illegal housing developments are considered. According to the regional urban planning regulations in force at the time of the approval of these plans, there are three possibilities: (a) developments classified as urban land (in its two categories of consolidated or unconsolidated); (b) developments classified as land for development; and finally, (c) developments classified as undeveloped land (rural land).

- Identification and definition of typologies: Based on the above information, the results of the field work, and the position of each illegal housing development in relation to both the main urban nucleus of the municipality and the new planned urban developments, three typologies of illegal housing developments were established.

3. Case Study: The Metropolitan Area of Seville

3.1. The Metropolitan Area of Seville

3.2. The Study Area

4. Results

4.1. Illegal Housing Developments in the Metropolitan Area of Seville and Their Integration into the Urban System

4.2. The Morphology of Illegal Housing Developments in the Metropolitan Area of Seville

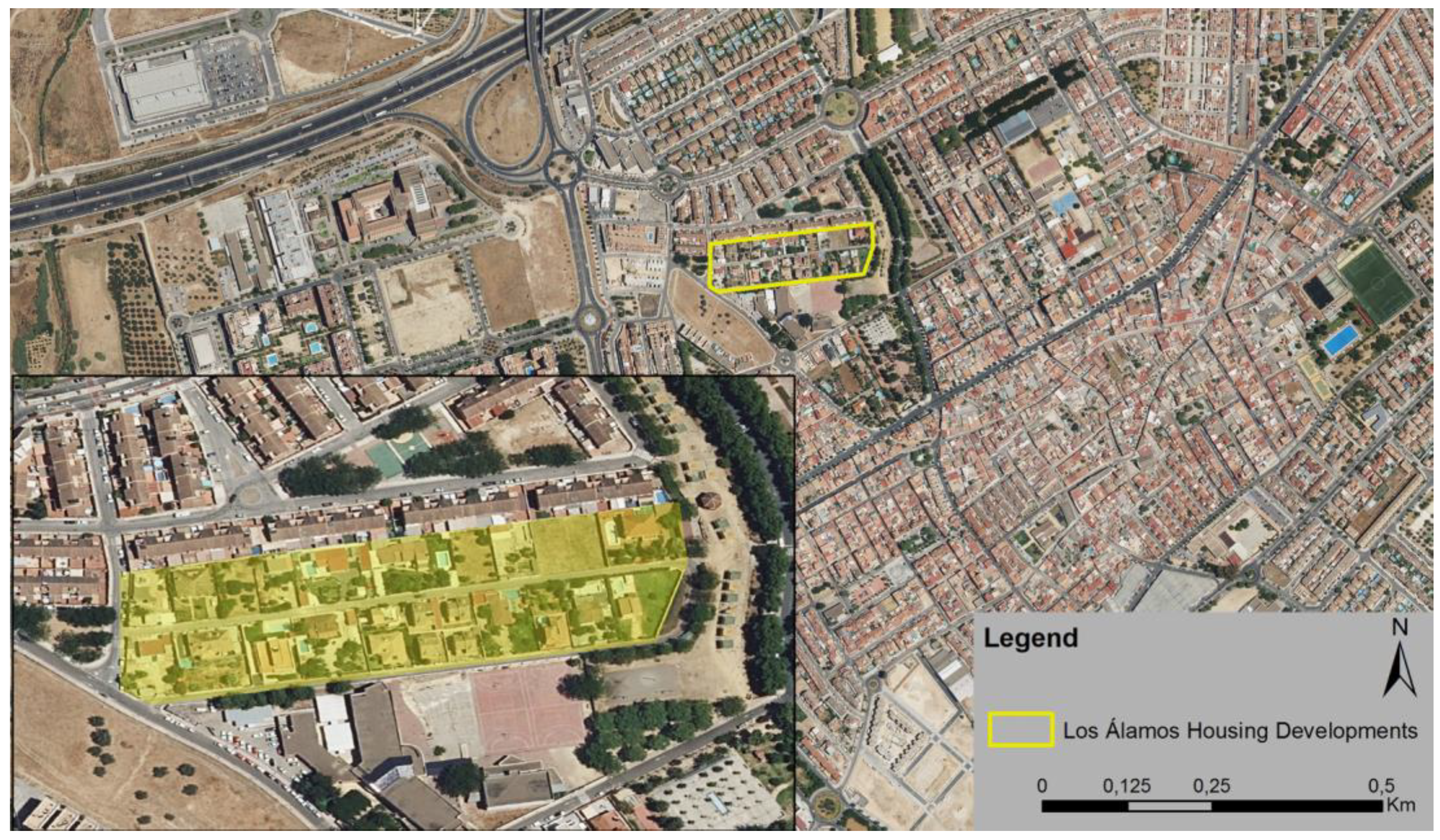

- Type 1: Illegal housing developments integrated into the current urban fabric;

- Type 2: Illegal housing developments partially integrated into the urban fabric under development;

- Type 3: Illegal housing developments disconnected from the urban fabric of the planned city.

4.2.1. Illegal Housing Developments Integrated into the Existing Urban Fabric

4.2.2. Illegal Housing Developments Partially Integrated into the Urban Fabric under Development

4.2.3. Illegal Housing Developments Disconnected from the Urban Fabric of the Planned City

5. Discussion

5.1. Regarding Existing Literature and Other Reference Cases

5.2. Regarding the Attitude of the Competent Authorities in the Field of Town and Country Planning in the Study Area

6. Conclusions

6.1. General Conclusions on the Morphological and Sociopolitical Conditioning Factors Imposed by Illegal Urban Development

6.2. Conclusions Regarding the Integration of Marginal Housing Developments in the Study Area: Eastern Sector of Aljarafe

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matarira, D.; Mutanga, O.; Naidu, M.; Vizzari, M. Object-Based Informal Settlement Mapping in Google Earth Engine Using the Integration of Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Planet Scope Satellite Data. Land 2023, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, M.; Bazoberry, G.; Blanco, C.; Díaz, S.; Fernández, R.; Florian, A.; Quispe, R.G.; González, G.; Landaeta, G.; Manrique, D.; et al. El Camino Posible. Producción Social del Hábitat en América Latina; Ediciones Trilce: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz Flores, E. Producción social de vivienda y hábitat: Bases conceptuales para una política pública. In El Camino Posible. Producción Social del Hábitat en América Latina; Arévalo, M., Bazoberry, G., Blanco, C., Díaz, S., Fernández, R., Florian, A., Quispe, R.G., González, G., Landaeta, G., Manrique, D., et al., Eds.; Ediciones Trilce: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2012; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pradilla Cobos, E. El mito neoliberal de la “informalidad” urbana. In Más Allá de la Informalidad; Craggio, J.L., Pradilla, E., Ruiz, L., Unda, M., Eds.; Research Center: Quito, Ecuador, 1995; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Urbanismo y Desigualdad Social; Siglo Veintiuno de España: Madrid, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Espacios del Capital: Hacia una Geografía Crítica; Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- López-Casado, D. Metodología para el análisis y la caracterización geográfica de la ciudad informal: Urbanizaciones ilegales en el municipio de Córdoba, España. Quid 16 Rev. Del Área De Estud. Urbanos 2022, 17, 99–120. Available online: https://publicaciones.sociales.uba.ar/index.php/quid16/article/view/7107 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Grashoff, U. Comparative Approaches to Informal Housing around the Globe; UCL Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodelli, F.; Tzfadia, E. The Multifaceted Relation between Formal Institutions and the Production of Informal Urban Spaces: An Editorial Introduction. Geogr. Res. Forum 2016, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, R.C.; Piñeira, M.J.; Vives-Miró, S. El proceso urbanizador en España (1990–2014): Una interpretación desde la geografía y la teoría de los circuitos de capital. Scr. Nova Rev. Electron. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 20, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés López, G. Recent Transformations in the Morphology of Spanish Medium-Sized Cities: From the Compact City to the Urban Area. Land 2023, 12, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Casado, D. De urbanización ilegal de fin de semana a barrio precario: Las parcelaciones ilegales en Córdoba. Ciudades 2021, 24, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, K. The Handbook of Urban Morphology; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tellman, B.; Eakin, H.; Turner, B.L. Identifying, projecting, and evaluating informal urban expansion spatial patterns. J. Land Use Sci. 2022, 17, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkiss, F. Cities by Design: The Social Life of Urban Form; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pojani, D. The self-built city: Theorising urban design of informal settlements. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M. Urban Informality: Experiences and Urban Sustainability Transitions in Middle East Cities; Springer: Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodelli, F.; Mazzolini, A. Inverse planning in the cracks of formal land use regulation: The bottom-up regularisation of informal settlements in Maputo, Mozambique. Plan. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zied Abozied, E.; Vialard, A. Reintegrating informal settlements into the Greater Cairo Region of Egypt through the regional highway network. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2020, 7, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch Peña, F.; Sáez, E. Ciudad, vivienda y hábitat en los barrios informales de Latinoamérica. In Proceedings of the Congreso Cudad, Territorio y Paisaje. Una Mirada Multidisciplinar, Madrid, Spain, 5 May 2010–7 May 2010; pp. 105–119. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/8889/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Whitehand, J.W. Recent advances in urban morphology. Urban Stud. 1992, 29, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, S.; Krishnamurthy, S. Neglected? Strengthening the morphological study of informal settlements. Sage Open 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potsiou, C. Policies for formalization of informal development: Recent experience from southeastern Europe. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodelli, F. The Dark Side of Urban Informality in the Global North: Housing Illegality and Organized Crime in Northern Italy. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2019, 43, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calor, I.; Alterman, R. When enforcement fails. Comparative analysis of the legal and planning responses to non-compliant development in two advanced-economy countries. Int. J. Law Built Environ. 2017, 9, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can Iban, M. Lessons from approaches to informal housing and non-compliant development in Turkey: An in-depth policy analysis with a historical framework. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, H. Capitalismo y Morfología Urbana en España; Libros de la Frontera: Barcelona, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Busquets Grau, J. La Urbanización Marginal; Polytechnic University of Catalonia: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- De Solá-Morales Rubió, M. La urbanización marginal y la formación de plusvalía del suelo. Pap. Rev. De Sociol. 1974, 3, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Solá-Morales Rubió, M.; Busquets, J.; Domingo Clota, M.; Font Arellano, A. Notas sobre la marginalidad urbanística. Cuadernos de Arquitectura y Urbanismo 1971, 86, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- López-Casado, D. Un fenómeno urbano enquistado en el cambio de paradigma de la urbanización informal: Parcelaciones ilegales en el municipio de Córdoba. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2021, 90, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Valcárcel, J. Residencias Secundarias y Espacio de Ocio en España. (Secondary Residences and Leisure Space in Spain); University of Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela Rubio, M. La residencia secundaria en la provincia de Madrid: Génesis y estructura espacial. Ciudad. Territorio. Revista de Ciencia Urbana 1976, 2, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Nel-lo i Colóm, O. Estrategias para la contención y gestión de las urbanizaciones de baja densidad en Cataluña. Ciudad. Territorio. Estud. Territ. 2011, 43, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Betrán Abadía, R.; Franco Hernández, Y. Parcelaciones Ilegales de Segunda Residencia: El caso Aragonés; General Council of Aragón, Department of Territorial Planning, Public Works and Transport: Zaragoza, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ezquiaga Domínguez, J.M. Parcelaciones ilegales en suelo no urbanizable: Nuevas formas de consumo del espacio en los márgenes de la ley del suelo. Ciudad. Territorio. Rev. Cienc. Urbana 1983, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- de Jaló;n, G.; Lastra, A.; Sainz, J.L.; Ezquiaga, J.M.; Moya, L. Estudio de las parcelaciones ilegales de la provincia de Valladolid. In Estudio de las Parcelaciones Ilegales de la Provincia de Valladolid; Official Association of Architects of Valladolid: Valladoli, Spain, 1986; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- García-Bellido, J. La cuestión rural. Indagaciones sobre la producción del espacio rústico. Ciudad. Territorio. Estud. Territ. 1986, 9–52. [Google Scholar]

- Herce Vallejo, M. El consumo de espacio en las urbanizaciones de segunda residencia en Cataluña. Ciudad. Territorio. Estud. Territ. 1975, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Burriel de Orueta, E.L. La larga huella en el territorio de las viviendas secundarias ilegales. El ejemplo de Gilet (Valencia). Cuad. Geogr. Univ. València 2019, 107–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górgolas Martín, P. Planeamiento urbanístico y suburbanización irregular en el litoral andaluz: Directrices y recomendaciones para impulsar la integración urbano-territorial de asentamientos. Ciudad. Territ. Estud. Territ. 2018, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Barrado, V. Urbanizaciones Ilegales en Extremadura; La Proliferación de Viviendas en el Suelo No Urbanizable Durante el Período Democrático: Extremadura, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Barrado, V.; Delgado, C.; Campesino, A.-J. Desregulación urbanística del suelo rústico en España: Cantabria y Extremadura como casos de estudio. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2017, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Casado, D. Illegal Parcelling in Cordoba (Spain): The Result of Illegal Urban Planning or Hidden City Development? Dela 2020, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Casado, D. La informalidad como nexo: Producción social del hábitat en ciudades latinoamericanas frente a parcelaciones ilegales en España. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2020, 19, 706–724. [Google Scholar]

- López-Casado, D.; Mulero, A. El fenómeno de las parcelaciones urbanísticas ilegales en Andalucía: Significado general y tratamiento en los planes de ordenación del territorio. Cuad. Geogr. 2021, 60, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Casado, D. Hidden City: The Footprint of Illegal Urbanisation in Spain. In Hidden Geographies; Krevs, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore-Cherry, N.; Kayanan, C.M.; Tomaney, J.; Pike, A. Governing the Metropolis: An International Review of Metropolitanisation, Metropolitan Governance and the Relationship with Sustainable Land Management. Land 2022, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuguitt, G.V.; Heaton, T.B.; Lichter, D.T. Monitoring the metropolitanisation process. Demography 1988, 25, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler, D. Introduction: Metropolitanisation and metropolitan governance. Eur. Political Sci. 2012, 11, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.R. Cycles within the system: Metropolitanisation and internal migration in the US, 1965–90. Urban Stud. 1997, 34, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa Angulo, J. Procesos y estructuras geodemográficas en la metropolitanización: Propuestas de debate sobre algunas cuestiones básicas. In La Población en Clave Territorial. Procesos, Estructuras y Perspectivas de Análisis; De Cos, O., Reques, P., Eds.; Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad: Madrid, Spain, 2012; pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Oriol, N. La tercera fase del proceso de metropolitanización en España. In Los Procesos Urbanos Postfordistas; Artigues, A., Bauzà, A., Blázquez, M., Murray, I., Rullán, O., Eds.; Universidad de las Islas Baleares y Association of Spanish Geographers: Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2007; pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Viñas, C. Los procesos de metropolitanización dispersa: Castro Urdiales (Cantabria) en la región urbana de Bilbao. Bol. Asoc. Geóg. Esp. 2018, 78, 474–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feria Toribio, J. Los procesos metropolitanos en España: Intensificación estructural y nuevos desafíos. Papers 2018, 61, 28–40. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/202405 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Coq Huelva, D. Crecimiento suburbano difuso y sin fin en el Área Metropolitana de Sevilla entre 1980 y 2010. Algunos elementos explicativos. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2012, 16, 387–424. [Google Scholar]

- Feria Toribio, J.M.; Andújar, A. Movilidad residencial metropolitana y crisis inmobiliaria. An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2015, 35, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega González, G. Las áreas metropolitanas andaluzas. Sevilla. In Areas Metropolitanas de España. La Nueva Forma de la Ciudad; Rodríguez, F., Ed.; Universidad de Oviedo, Servicio de Publicaciones: Oviedo, Spain, 2009; pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- García García, A.; Caravaca, I. El Debate sobre los territorios inteligentes: El caso del área metropolitana de Sevilla. EURE 2009, 105, 23–45. Available online: http://www.eure.cl/index.php/eure/article/view/1389 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Recuenco Aguado, L. Frente al “Potaus”: Área Metropolitana y “Plan Subregional de Ordenación del Territorio de la Aglomeración Urbana de Sevilla” (In front of the “Potaus”: Metropolitan Area and “Plan Subregional de Ordenación del Territorio de la Aglomeración Urbana de Sevilla); Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- General Directorate of Urban Planning. Inventario de Parcelaciones Urbanísticas de la Provincia de Sevilla: Análisis y Diagnóstico; Junta of Andalusia, Regional Ministry of Environment and Territory: Seville, Spain, 1989; pp. 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- General Directorate of Territorial Planning and Urban Development. Inventario de Parcelaciones Urbanísticas en Suelo no Urbanizable en Andalucía (Memoria); General Directorate of Territorial Planning and Urban Development. Regional Ministry of Public Works and Transport, Junta of Andalusia, General Directorate of Urban Development: Seville, Spain, 2004; pp. 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Marín de Terán, L. Sevilla: Centro Urbano y Barriadas; Servicio de Publicaciones: Seville, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- González Dorado, A. Sevilla: Centralidad Regional y Organización Interna de su Espacio Urbano (1900–1970); Banco Urquijo Publications Service: Seville, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Decree 267/2009, of June 9, 2009, Approving the Spatial Plan for the Urban Agglomeration of Seville (BOJA No. 132 of 9 July 2009). Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2009/132/59 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Comunidad de Madrid. Urbanizaciones Ilegales. Programa de Actuación; Information and Documentation Center of the Regional Ministry of Land Management, Environment and Housing: Madrid, Spain, 1984; pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Provincial Council of Valencia. Urbanismo y Medio Rural. In Valencia: La vivienda Ilegal de Segunda Residencia; Provincial Council of Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Requena Sánchez, M.D. Organización Espacial y Funcional de la Residencia Secundaria en la Provincia de Sevilla; Universidad de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 1987; Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment and Territorial Planning. Plan de Ordenación del Territorio de la Aglomeración Urbana de Sevilla. (Plan for Territorial Planning for the Urban Agglomeration of Seville.); Junta of Andalusia, Regional Ministry of Environment and Territory: Seville, Spain, 2009; pp. 1–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho Martí, J. Conjuntos residenciales al margen del planeamiento en la periferia de Zaragoza. Geographicalia 1989, 26, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho Martí, J. El Espacio Periurbano de Zaragoza; Zaragoza City Council, Area of Culture and Education, Cultural Action Service: Zaragoza, Spain, 1989; Volumen I y II. [Google Scholar]

- Pie i Ninot, R.; Navarro, F. De los “establiments” a las parcelaciones ilegales. Ciudad. Territorio. Estud. Territ. 1988, 75-1, 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Castilla y León. Plan Regional de Ámbito Sectorial Sobre Parcelaciones Ilegales: Metodología, Inventario y Diagnóstico; Junta de Castilla y León: León, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo de la Fuente, A.F. La pérdida de los valores paisajísticos y ambientales en el término municipal de Osuna por la proliferación de urbanizaciones ilegales. Cuad. Amigos Mus. Osuna 2003, 5, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Fernández, M.C. Estudio de la vivienda irregular en Sevilla: El caso de Marchena. Espac. Tiempo Rev. Cienc. Hum. 2014, 28, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Defensor del Pueblo Andaluz. Las urbanizaciones ilegales en Andalucía. Informe Especial al Parlamento Andaluz; Defensor del Pueblo Andaluz: Sevilla, Spain, 2000; Available online: https://www.defensordelpuebloandaluz.es/sites/default/files/Recomendaciones_urb_ilegales.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Fernández Rivera, F.J. Parcelaciones y Viviendas en Suelo Rústico en Torno a Grandes ejes Viarios. La Accesibilidad del Territorio Como Motor de Urbanización Irregular; Depósito de Investigación de la Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/141379 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Górgolas Martín, P. Sevilla ante el reto metropolitano: Del fracaso institucional a la mercantilización territorial. Astrágalo Cult. Arquit. Ciudad. 2019, 26, 15–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Reina, J.J. Evolución del primer ayuntamiento democrático de la ciudad de Sevilla. Hist. Actual Online 2018, 45, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

| Spatial Scope | 1996 Population | 2022 Population | % Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 7,234,873 | 8,500,187 | 14.89% |

| Seville (provincial) | 1,705,320 | 1,948,393 | 12.48% |

| Seville (central city) | 697,487 | 681,998 | −2.27% |

| Metropolitan area | 1,317,985 | 1,547,640 | 14.84% |

| Municipalities in the study area | 147,917 | 214,117 | 30.92% |

| 1991 Census | 2011 Census | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Dwellings | % Non-Principal Dwellings | No. of Dwellings | % Non-Principal Dwellings | %Variation No. of Dwellings | %Variation Non-Principal Dwellings | |

| Metropolitan area | 438,365 | 22.06% | 686,410 | 19.29% | 57.58% | −2.77% |

| Seville (central city) | 246,036 | 19.93% | 337,225 | 20.40% | 37.06% | 0.47% |

| Study area | 44,391 | 23.61% | 86,015 | 18.24% | 93.77% | −5.37% |

| 1988 Inventory | 2003 1 Inventory | 1988/2003 Inventory Variation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Plots | Total Plots | Municipalities | No. of Plots | Total Plots | Municipalities | No. of Plots | Total Plots | Municipalities | |

| First area | 108 | 2321.91 | 19 | 61 | 897.3 | 10 | −43.52% | −61.36% | −47.37% |

| Second area | 123 | 3525.65 | 16 | 96 | 1118.82 | 12 | −21.95% | −68.27% | −25.00% |

| Totals | 231 | 5847.56 | 35 | 157 | 2016.12 | 22 | −32.03% | −65.52% | −37.14% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Casado, D.; Fernández-Salinas, V. The Expression of Illegal Urbanism in the Urban Morphology and Landscape: The Case of the Metropolitan Area of Seville (Spain). Land 2023, 12, 2108. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122108

López-Casado D, Fernández-Salinas V. The Expression of Illegal Urbanism in the Urban Morphology and Landscape: The Case of the Metropolitan Area of Seville (Spain). Land. 2023; 12(12):2108. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122108

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Casado, David, and Víctor Fernández-Salinas. 2023. "The Expression of Illegal Urbanism in the Urban Morphology and Landscape: The Case of the Metropolitan Area of Seville (Spain)" Land 12, no. 12: 2108. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122108

APA StyleLópez-Casado, D., & Fernández-Salinas, V. (2023). The Expression of Illegal Urbanism in the Urban Morphology and Landscape: The Case of the Metropolitan Area of Seville (Spain). Land, 12(12), 2108. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122108