Abstract

In 2019, residents of the rural district of San Rafael Comac in the municipality of San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, challenged the implementation of the 2018 Municipal Program for Sustainable Urban Development of San Andrés Cholula (MPSUD), a rapacious urban-planning policy that was negatively affecting ancestral communities—pueblos originarios—and their lands and traditions. In 2020, a legal instrument called the writ of amparo was proven effective in ordering the repeal of the MPSUD and demanding an Indigenous consultation, based on the argument of self-recognition of local and Indigenous identity. Such identity would grant them the specific land rights contained in the Mexican Constitution and in international treaties. To explain their Indigenous identity in the writ of amparo, they referred to an established ancient socio-spatial system of organization that functioned beyond administrative boundaries: the Mesoamerican altepetl system. The altepetl, consisting of the union between land and people, is appointed in the writ of amparo as the foundation of their current form of socio-spatial organization. This paper is a land-policy review of the MPSUD and the writ of amparo, with a case-study approach for San Rafael Comac, based on a literature review. The research concludes that Indigenous consultation is a key tool and action for empowerment towards responsible land-management in a context where private urban-development impinges on traditional land uses and customs, and could be beneficial for traditional communities in Mexico and other Latin American countries.

1. Introduction

Human rights are relevant to sustainable development, and land is essential to achieve such rights, as “access to, use of and control over land directly affect the enjoyment of certain economic, social, cultural, political and civil rights [1]”. For this reason, international human rights law recognizes the need to respect the specific human and land rights of Indigenous peoples. Since 2007, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) has been established as a framework and an instrument that is “concerned that Indigenous peoples have suffered from historic injustices as a result of, inter alia, their colonization and dispossession of their lands, territories and resources, thus preventing them from exercising, in particular, their right to development in accordance with their own needs and interests” [1]. However, international frameworks (such as covenants, conventions, customary international law, resolutions, declarations, recommendations and guidelines [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]) still need to be transferred to local policies that respond to the contextual legal framework, for them to be operative. According to Gilbert and Begbie-Clench, “Indigenous peoples are generally subjected to complex legal processes, which usually impose an onerous burden on the Indigenous plaintiffs to prove their right” [9], including the ‘burden of proof’ to demonstrate their historical, continuous and traditional usage and attachment to land.

The Mexican Constitution [10] in Article 2 recognizes Indigenous peoples’ traditional ways of social, cultural, political and economic organization, and decrees their right to manage their habitat and preserve their land. In the same line, Article 27 establishes that laws must protect the integrity of Indigenous lands. In the State of Puebla, local community groups in San Andrés Cholula from both the urban core and the peri-urban fringe have enforced their recognition as pueblos originarios (a term that could be roughly translated as first peoples, as will be furtherly explained), based on Article 2 of the Mexican Constitution. Article 2 establishes the primary criteria to determine such identity as self-awareness of indigeneity. The distinction, beyond an ethnical recognition tool, links a person or a group of people to an Indigenous community acknowledged by the Mexican State, due to cultural, historical, political, linguistic, and other types of connections [11].

Yet, Cholula’s urban-growth pressure has led to the gentrification of San Andrés’s urban core (cabecera municipal) and a great number of hectares of rural lands, displacing local communities through “silent expulsions”; a rooting to their territory and ancient socio-spatial forms of organization have raised Indigenous self-awareness as a group of inhabitants. In this sense, as Sierra [12] suggests, contemporary Indigenous identities are usually political. Beyond the search for an abstract identity, they seek self-determination and autonomy on the use of local resources, and they question the imposed political and cultural supremacy through legal instruments and statements. This quest led to the definition of pueblos originarios as ancestral communities, usually in the form of an Indigenous group bonded to a native language and/or cultural heritage. However, in the case study of San Rafael Comac, a rural town located in the municipality of San Andrés Cholula, the villagers identified as pueblos originario due to their connection with Cholula’s historical territory, rather than through ethnic matters. Nevertheless, the singularity of San Rafael Comac lies in the mixture of cultural groups, which enabled a particular socio-spatial and bio-cultural relationship with the land, and that must be preserved.

According to San Rafael Comac’s pueblos originarios discourse, their relationship with the land has followed the altepetl socio-spatial structure since pre-Hispanic times. Such socio-spatial organization has been regarded as the basis for Mesoamerican human settlements that encompasses land, people and cosmogony [13]. Nowadays, they interpret altepetl as the system that once established their socio-religious and socio-political form of organization. However, the urban lexicon does not recognize altepetl as a formal organization, even if it prompts a sense of territorial awareness in the context of predatory urban-development practices. The issue first emerged during the 1990s, when neoliberal trends and globalization processes promoted a land reform that opened up the ejido and communal lands to the free market, which triggered massive expropriations and urbanizations in peri-urban areas [4]. In such urban-development euphoria, the municipality of San Andrés Cholula was part of an ambitious urban plan targeted to develop a new economic-, services- and residential-sector across different municipalities (San Pedro Cholula, San Andrés Cholula, Puebla, and Cuautlancingo). For its implementation, it was necessary to expropriate more than 1000 hectares of ejido and agricultural land [13].

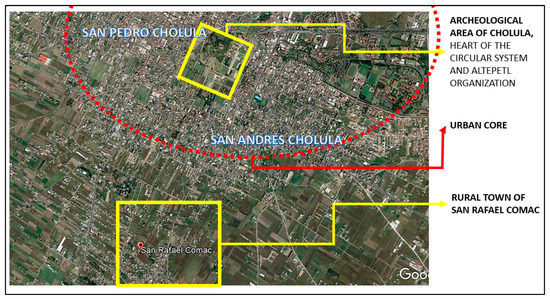

In the municipality of San Andrés Cholula, the urban anarchy from the last 20 years has grown to such a level, that rural and peri-urban communities began to fight to protect their access to water resources and their rights to the land. In the eyes of the locals, the urban plan “has mainly addressed the interests of real-estate investors in a non-transparent process that eluded customary and rural actors” [14]. As a result, “San Andrés has been subject to constant conflicts linked to displacement, expropriation, touristic exploitation, social and urban exclusion, and disputes over land rights” [14]. The turning point was when the small rural community of San Rafael Comac (Figure 1) was granted in 2020 a writ of amparo, which repealed the 2018 Municipal Program for Sustainable Urban Development of San Andrés Cholula (MPSUD). The 2018 MPSUD was formulated without Indigenous consultation, threatening the ways of life of the local community—recognized as pueblo originario—in terms of land-use change and land taxation.

Figure 1.

Territorial location of San Andrés Cholula and San Rafael Comac. Source: Google Earth (2017).

San Rafael Comac is an exemplary case in Mexico. due to the following: firstly, because although traditionally most legal demands of Indigenous groups aim at environmental protection, this one focused on urban planning. Second, because the legal system favored the local rural community, demanding its inclusion in the planning and decision-making processes, and commanding the creation of a new urban-development plan and a land-management program for San Andrés Cholula that would incorporate the constitutional right of Indigenous consultation. Third, because according to the pueblos originarios’ narrative, local socio-spatial organization is based on the ancient altepetl system, the foundation of native bio-cultural identity. Fourth, because the rural community fought not only for bio-cultural protection, but also for their rights as pueblo originario to be consulted about land-management processes. These facts enable other rural and peri-urban communities who have self-identified as pueblos originarios, to fight for their land rights and secure land-tenure.

Therefore, based on the case study of San Rafael Comac in San Andrés Cholula, four essential questions arise in this theoretical discussion: (1) How should the recognition of pueblos originarios be understood, beyond ethnicity, in order to safeguard locals’ land rights and culture? (2) What is the role of ancient-but-active socio-spatial structures such as altepetl in the enforcement of land rights? (3) Is the writ of amparo an effective instrument towards inclusive land management? (4) To what extent are municipal authorities accountable for the advancement of inclusive land-management practices?

To answer these questions, this study is divided into the following sections, beginning with Section 2 pointing out by what means certain rural communities in San Andrés Cholula have fought for their legal recognition as pueblos originarios. In addition, it presents an application of the writ of amparo as a remedy against planning instruments that disregard traditional land-uses, as well as an exploration of altepetl as the foundation of community-based instruments to exercise native communities’ land rights. Section 3 presents an overview of the case study, its historical approach to land management, and the spatial and legal implications of such an approach. Section 4 is an overview of the legal framework for land management in Mexico. In Section 5, we critically assess the land-management tools on the socio-spatial organization of the case study, based on four statements. Finally, we conclude that the writ of amparo is a powerful legal instrument for preserving fundamental rights over the land, seeking for community participation in land-planning processes where traditional land-uses prevail. However, for the writ of amparo to be successful, a strong socio-spatial organization—justified in this case by Comac’s pueblos originarios, with the altepetl system as its origin—as well as holding the municipal authorities accountable, are key. Together, legal instruments, an empowered community, and responsible public authorities can enable horizontal land-management.

2. Theoretical Discussion

2.1. Problem Statement: Awareness and Recognition of Indigenous Identities: The Legal Basis for Inclusive Development

Article 2 of the Mexican Constitution [10] points out the multicultural character of the Mexican nation originally grounded in its Indigenous peoples. Multiculturalist modifications of most Latin American constitutions that took place between the 1980s and the 1990s are, according to Jacobsen, “generally thought of as advancements” and signs of “a radical break with colonial legacy and former unjust policies” [15] (pp. 178–179). Early nineteenth-century Mexican Indigenista narratives supported imaginaries of national identity in “newly founded nation-states that would distinguish them from Europe and create a national historical counterbalance to increasing industrialization and modernization” [15]. In the early twentieth century, official Indigenismo policies attributed “the revolution to Indigenous groups [as] a founding ideological basis for post-revolutionary government” (p. 18); nevertheless, Indigenous people were assimilated through “education and economic and social development” [5]. Multiculturalist policies were, therefore, recognition policies established as a way to (insufficiently) even out a political debt to Indigenous peoples who were systematically acculturated and the subject of discrimination, segregation and epistemicide, as stated by Boaventura de Sousa Santos [16], and who were beginning to demand their political right to self-determination, as occurred in 1992 with the National Zapatist Army of Liberation in southern Mexico.

Thus, the Mexican Constitution [10] states that one of the definitions of multiculturalism is “based originally on its Indigenous peoples”. Both terms, “Indigenous peoples”, and “Indigenous communities”, are herein defined as follows, in Table 1:

Table 1.

Definition of Indigenous peoples and communities based on the Mexican Constitution. Elaborated by Guízar-Villalvazo, M. (2022).

On the one hand, the legal definition of pueblos originarios roots them in a remote past, petrifying their cultural and political forms of organization. On the other hand, it enables self-recognition as the only requirement for the identity construction process. Both aspects turn Indigenous distinctiveness into a passionate theoretical debate.

Article 2 sets out the fundamental rights applicable to Indigenous peoples that all Federal and State laws shall look after. The first right is the indispensable self-awareness of indigeneity, as “the fundamental criterion to determine to whom the provisions on Indigenous people apply” [10]. The second right consists of the right to self-determination and autonomy. Both lead, among other abilities, to deciding how their internal forms of coexistence shall be, as well as their social, economic, political, and cultural forms of organization; to preserve their cultural and identity elements; to “maintain and improve their environment and lands” [10]. In addition, Article 2 enables them to have “preferential use of the natural resources of the sites inhabited by their Indigenous communities”, with certain exceptions specifically determined in the Constitution.

The main mechanism through which Indigenous peoples’ rights are guaranteed, according to the Constitution, consists of the establishment of institutions and public policies jointly designed and operated with the State. In addition, fraction IX of Article 2 specifies that Indigenous consultation is mandatory “to prepare the National Development Plan, the State plans and the local plans”, as well as the incorporation of their recommendations and proposals into the planning instruments.

Derived from the above-mentioned points, Article 2 of the Mexican Constitution states that:

- Indigeneity is recognized as a fundamental element within the national social structure.

- The only requirement to regard a person or a collectivity as Indigenous consists in their self-adscription to an ethnic group (strictly speaking, there is no need to validate Indigenous identity through any other medium).

- The rights to self-determination and autonomy allow the continuity of Indigenous communities’ forms of organization.

- Indigenous subjectivities may be built upon structures settled a long time ago (such as altepetl) in order to preserve resources, land, and culture; in such cases, ethnicity becomes a secondary matter. In addition, such prerogatives entitle them to preserve their culture and identities, as well as their land and natural resources.

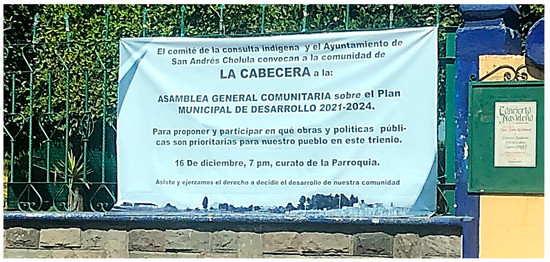

- Indigenous peoples’ rights shall be secured through institutions and public policies, with the latter designed a priori in an inclusive manner through Indigenous consultations. (See Figure 2, where the church of San Juan Aquiahuac is used as a space to invite the community to discuss the new urban-development plan, invited by the Indigenous consultation committee).

Figure 2. The general assembly call a consultation for the new municipal development plan of San Andrés Cholula. Billboard located in the church of San Juan Aquiahuac. Source: Guizar-Villalvazo, M. (2021).

Figure 2. The general assembly call a consultation for the new municipal development plan of San Andrés Cholula. Billboard located in the church of San Juan Aquiahuac. Source: Guizar-Villalvazo, M. (2021).

2.2. The Amparo Procedure

Weak-governance regions such as Latin America are prone “to the traditional insufficiencies of the general judicial means for granting effective protection to constitutional rights. This prompted the development of amparo action for the protection of human rights” [17] (p. 11).

The writ of amparo was set out first in the 1857 Mexican Constitution, and adopted later by other Latin American nations. The writ of amparo, meaning “appeal for shelter or protection”, originated in Mexico, and has served as a model for other judicatures of the Spanish-speaking world, and thus has no equivalent in British or American Law. However, it is included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) as Article 8 [5]. In any case, the writ of amparo entails different procedures in other countries.

The writ of amparo has its origins in Mexico in the first half of the 19th Century, in the fight against land-tenure changes and expropriation that had hampered Mexican rural and Indigenous communities since the 19th Century, mainly as a result of the colonial tenure system based on private property that disregarded the Mesoamerican communal tenure. The primary amparo trials were pushed by rural communities against hacendados or landlords that disposed locals’ land and forced Indigenous communities to work under conditions of slavery [18].

The fight for a fair and communal land-tenure system subsisted after colonization. In fact, large-scale land grabbing and expropriations were still carried out after the Mexican War of Independence and the Mexican Revolution, even until today. Thus, in a country with a weak rule of law, injustices, pillage, and spoliation are still the norm, and property developers and the government use them to overpower pueblos originarios that still conserve their own socio-spatial organizational system and customs.

Hence the need for the writ of amparo as a legal instrument that, besides granting the protection of human rights, encompasses five other purposes: (1) the protection of personal freedom, equivalent to the writ of habeas corpus in other nations; (2) the examination of the constitutionality of laws; (3) the examination of the constitutionality and legality of judicial decisions; (4) the administrative acts of the procedure; and (5) to protect agrarian rights [19] (pp. 83–84). The writ of amparo is a rightful resource against the violation of constitutional rights, which may be appealed to in Federal courts [10] (Article 103).

2.3. Contextualization: Altepetl as the Discursive Foundation of the Pueblos Originarios in San Andrés Cholula Socio-Spatial Organization

The main argument that the pueblos originarios offer in the writ of amparo to explain their indigeneity (or their character of first peoples in San Andrés Cholula), consists in their socio-spatial organization inherited from the ancient Mesoamerican altepetl. Such system is at the same time the foundation for the current sistema de cargos, both of which shall be further explained.

Cosmogony and spiritual beliefs defined the relationship between land and people in the ancient Mesoamerican civilization [20]. Accordingly, the socio-spatial organization of the altepetl (“water-mountain” in the Nahuatl language) is a metaphor of the interaction of the people with their environment. Fernández-Christlieb [21] describe altepetl as an “organized community whose members were tied to the land by a customary law and who have interaction with the environment”. Cholula’s history of human settlements, which extends beyond 3000 years, makes it stand out as an exemplary case for Fernández-Christlieb to depict in altepetl interactions [19,22].

In this sense, Cholula portrays the three attributes of altepet: (1) altepetl as a community—a well-organized society ruled by a local hierarchy of citizens; (2) altepetl as law—customary law with a rotation system of collective tasks and leaderships, based on its neighborhoods and rural towns; (3) altepetl as land— a socio-spatial recognition of the territory, established on a “mountain full of water”, with its provision of vital resources such as water, seeds, animals, and raw materials [19].

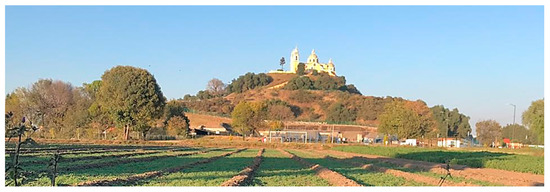

In short, pyramids were erected in carefully selected locations within human settlements as the physical manifestation of altepetl: a landscape and architectural ideal of sacred mountains that is the basis of the local rotational socio-religious political system [22,23]. The system changed with the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in 1519, who did not grasp the complexity of altepetl and the civilizations they encountered. As a result, some features persisted, but other were intersected by new land regulations and laws. For instance, Franciscan missionaries translated altepetl as pueblos, although the newly introduced private property and boundaries between urban and rural communities representative of pueblos contradicted the essential altepetl communal structure (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Great Pyramid of Cholula “Tlachihualtépetl”, topped by the Sanctuary of la Virgen de los Remedios, and surrounded by the few remaining pre-Hispanic agricultural fields. Source: Schumacher M. (2019).

For the new rulers, the rotating administrative system of altepetl, beyond the distribution of tasks among neighbors and their local leaders, was useful for the local organization of the main neighborhoods or barrios of Cholula, for them to comply with religious and social purposes. The rotation system, called Sistema de cargos or mayordomías, is a hierarchical and circular system for the annual administration of the Catholic temples on behalf of the citizens [21]. However, the circular system goes beyond the religious implications; “although the mayor is the maximum authority of the municipality, mayordomías represent the vertical socio-spatial organization that link municipal authorities with the communities and their local representatives, and they act as engaged stakeholders that guard the interests of the community they represent” [15]. In the case of San Andrés Cholula, the modern interpretation of altepetl empowers the mayordomías in each barrio.

One example of how Catholic temples acquire the role of socio-spatial operators beyond their religious functions is when the Parish of San Andrés Cholula concentrates in its spaces the participatory planning activities of the community. Figure 2 shows the announcement of a public assembly by the City Hall and the Indigenous Consultation Committee, to discuss the new municipal development plan, displayed at the church of San Juan Aquiahuac. In these assemblies, mayordomías are invited to participate actively, together with local inhabitants. Such events enable the churches to be at the core of community activities in barrios. For instance, the Indigenous consultation that took place in the San Andrés’ parish on 16 December 2021, was the setting for a group of circa 100 villagers to discuss specific issues and concerns with representatives of the new municipal government, in order to include them in the design of the municipal development plan.

One of the core issues addressed was the decrease in property taxes to the pueblos originarios enabling them to access a regularized land-tenure, without which they are under permanent threat of land loss. The relevance of this event is that it marks the beginning of the practice of Indigenous consultations in San Andrés Cholula.

3. Methods and Background

This paper is a literature review of specific legal instruments and land policies that impact pueblos originarios and their autonomy, with a case-study approach of San Rafael Comac. The policy review included the 2018 Municipal Plan for Sustainable Urban Development (MPSUD), the 2016 General Law of Human Settlements, Territorial Planning and Urban Development (GLHS), the 1988 General Law for Ecological Equilibrium and Environmental Protection (GLEEEP), the Law of Territorial Management and Urban Development (LTMUD), and the Municipal Program of Ecological Land Management (MPELM).

3.1. Case Study: Land-Management and Urban Planning Challenges in San Andrés Cholula

Struggles regarding land development and rights are not a recent issue in the Cholula region. According to scholars such as McCafferty [22,24] and Anamaria Ashwell [25,26,27], there are historical records on conflicts, migrations, and displacements of various pre-Hispanic cultures. However, the most significant land losses in San Andrés Cholula in recent times date back to the early 1990s, because of a series of expropriations carried out by the state government to create the Atlixcayotl Territorial Reserve—an area that was urbanized, gentrified and modernized in the consecutive years. These massive expropriations of rural land were a precedent recorded in the memory of local people, raising awakening attitudes of resistance and distrust when modern public-policies were introduced, and were often identified as threats to their land and traditions. Such projects often exclude, discriminate, expel and/or displace the locals, while usually benefiting large industries. However, the locals have not been entirely passive, regarding these events. Specific groups have sought after legal strategies to preserve their land. One of them is the self-recognition of pueblos originarios, which confers specific rights on local peoples to manage their land.

In the case study of San Andrés Cholula, land is not managed responsibly; the public policy instrument that currently regulates urban land management is the Municipal Program for Sustainable Urban Development Program [28] (hereafter MPSUD). Following the title of the planning tool in question, sustainable urban development is the general objective that draws in ecological, economic, territorial, and urban-mobility policies. Hence, land management in San Andrés Cholula is designed following economic and ecological purposes, as well as urban-development strategies, specifically through the definition of land uses in order to manage urban growth [28]. Moreover, the 2018 MPSUD was intended to contemplate a planning horizon up to the year 2050, where some of the main aims to be fulfilled were the improvement of the local administration’s competitiveness, as well as those of the infrastructure for housing public-services and of the productive activities over an orderly territory [16]. The issuance of the 2018 MPSUD was based on the argument that the precedent planning instruments [16,29,30] were not able to face the requirements of a dynamic and growing urbanization within a metropolitan context. The public policy instrument remarked on the divergence of its own objectives from the objectionable performance of previous public administrations. In this sense, it asserted that both the city of Puebla and the growth of its metropolitan area was enhanced by the profitability of investments, notwithstanding the consequential pauperization of a large social sector and the socio-spatial segregation of lower-income social classes, environmental destruction, and an unrestricted land-market. Its specific aims consisted of: (a) moving towards a more compact and orderly city; (b) occupying empty urban lots, instead of peripheral urban expansion on agricultural land; (c) encouraging a compatible mix of land uses to achieve an environmentally sustainable space, as well as enhancing mobility; (d) increasing the efficiency of the city and the reduction of infrastructure costs [28].

Consequently, although the 2018 MPSUD tried to achieve municipal development, social equitability, economic competitiveness, and ecological balance, through land-use policies [28], the local people, especially pueblos originarios, have claimed to be excluded from the urban-planning decision-making, as land-use policies have become prejudicial to their interests. In addition, there are several documented cases in the region of land loss by pueblos originarios that state that the 2018 MPSUD has enabled real estate agencies to conduct predatory practices such as coerced sales, expropriations and arrest warrants [31]. To be heard, the pueblos originarios have brought human-rights matters into the discussion, especially those concerning Indigenous identity [32].

Municipalities also have land-management prerogatives, which should make them accountable for their urban development. In the case of San Andrés Cholula, urban growth has particularly occurred over expropriated rural land as a part of the neoliberal urban-planning trends that introduced communal lands to the free market [33]. Even when subject to laws of the highest hierarchy related to sustainability, economic interests may be the underlying guidelines that shape public policies that determine where, when, and how a municipality would extend. Therefore, the development of San Andrés Cholula —backed by both the legal system and the current public policies—is related to and enhanced by a growing real-estate industry. In addition to physical manifestations shown elsewhere, statistical data evidence shows that San Andrés Cholula has nearly quadrupled since 1990, reaching 154,448 inhabitants in 2020 [34].

Simultaneously, the construction and real estate sectors in Puebla have strengthened at least in the past two decades, as observed in a study carried out in 2016 by the National Statistics and Geography Institute (INEGI). The study evidenced that the real estate industry had an average annual growth of 3% between 2003 and 2014, and that it represented 14% of Puebla’s GDP in 2014, just behind the most important sectors in the state, the commerce and manufacturing industries. The construction industry has also grown almost 3% annually, and represented around 6% of GDP in 2014 [34].

Notwithstanding urban growth, sustainable urban-planning has not been consistently achieved, and regulatory instruments persistently become ineffective. That is the case of the 2018 MPSUD, abrogated in October 2020 by the municipal council after the writ of amparo resolved that it transgressed specific fundamental constitutional rights. The municipal council documented [35] in a memorandum corresponding to the extraordinary meeting where the revocation took place, that such decision was led by at least two factors. The first one is related to contradictory dispositions that derived from rejections by the Secretary for Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT, by its acronym in Spanish), to grant permits and land-use authorizations because they were not adhering to the law. The second was connected to socio-political controversies, which included strong criticisms on behalf of communities rooted in San Andrés long before its vertiginous growth, claiming that their needs were not met. Such social groups had expressed their nonconformities; moreover, they had recourse to the amparo trial as a legal strategy to defend their rights and to be considered in the decision-making processes.

The 2018 MPSUD was part of the 2014–2018 Municipal Development Plan from the right-wing ruling party, Partido Acción Nacional (PAN). It was issued on October 4, just before the 2014–2018 PAN’s administration concluded on 14 October 2018, taken over by the new administration of the national-populist party Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (MORENA). Because of time pressures, there was not enough time for it to be signed off by the Public Registry of Property and Commerce, a mandatory condition for it to be fully applicable. Notwithstanding this pending task, the 2018 MPSUD began to be applied. Even though it posed a critique to previous predatory practices and presented a discourse that highlighted the introduction of more inclusive land-management policies, the modification of land use is evidence that it still privileged the real estate industry, who had operated through pressure and intimidation, according to the villagers [31].

3.2. Local Resistance and Demand of Land-Rights Recognition

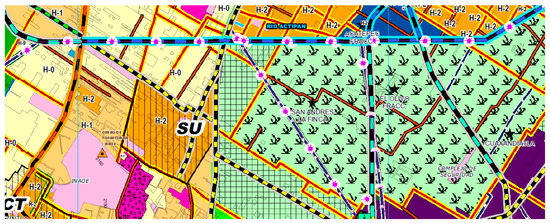

In 2019, a group of villagers of San Rafael Comac contested the 2018 MPSUD, declaring that the Indigenous population was not consulted in its formulation process. After a legal battle, the writ of amparo was awarded in February 2020, in favor of the villagers against the application of the 2018 MPSUD in San Andrés Cholula. It recognized the violation of the right to carry out a prior Indigenous consultation, as the 2018 MPSUD potentially had a “significant impact” on the community. The writ of amparo enunciates a series of situations where “significant impact” on customs and traditions of an Indigenous community may occur [2]: (a) loss of traditional land; (b) eviction from land; (c) resettlement; (d) exhaustion of resources; (e) destruction and contamination of the environment; (f) social and community disorganization; (g) and negative health and nutritional impacts, among others. According to the writ, the 2018 MPSUD foresaw changes that would have a significant impact on the customs and traditions of the villagers of San Rafael Comac, such as (Figure 4): (a) the expansion of streets and roads, crossing properties, homes and other relevant buildings for the community, such as churches; (b) the construction of gated communities, including skyscrapers, which would affect the traditional landscape and would lead to the depletion of natural resources to the detriment of the community organization, health and subsistence; (c) the modification of land uses from agricultural to residential, constituting an economic burden for the villagers due to increasing taxes that make agricultural activities unsustainable [35,36].

Figure 4.

Land uses and densities in San Rafael Comac, Source: MPSUD (2018).

In this sense, the 2018 MPSUD [17] only recognized San Luis Tehuiloyocan, another rural district, as an exclusively rural-agricultural area, and characterized San Rafael Comac as an urban sub-center, marking it out as a cultural-tourism spot. Arguing demographic growth in San Andrés Cholula (projected to be 277,000 inhabitants by the year 2050, according to the 2018 MPSUD) the program appointed the number of developable hectares per junta auxiliar as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Developable land in San Andrés Cholula up to the year 2050. Source: MPSUD (2018).

These initiatives were considered a threat to the villagers and to their right to define the scope of “development” of the land they have traditionally inhabited. The legal process ended with the writ of amparo, where the Indigenous identity of the demanders was recognized, based on Article 2 from the Mexican Constitution, and following an anthropological expert’s opinion that the writ sustained their self-awareness.

The amparo commanded the municipal authorities to leave the 2018 MPSUD unsubstantiated and to issue a new municipal program that would guarantee that the pueblos originarios were to be consulted prior to its issuance, as “Indigenous consultation must be previous, culturally appropriate, informed, carried out in good faith and not coerced” [11].

Although the municipal authorities contested the writ of amparo on 25 February 2020, the corresponding Collegiate Circuit Court dismissed such appeal for review in March 2020, and its compliance was required once it was deemed final judgment on 17 September 2020. Hence, the writ was fundamental to the repeal of the 2018 MPSUD by the municipal council on 13 October 2020. The writ of amparo is thus a land-management tool worth highlighting.

Following this, a series of workshops to incorporate the villagers’ view of San Andres Cholula into the planning processes of a brand new MPSUD took place during 2020 and 2021. For the time being, no new MPSUD has been issued, and the currently applicable program is the outdated version of 2008. In addition, a new government is now in charge and must undertake the pending tasks, which might imply starting over and dismissing whichever advance there was. Delays might be causing even more harm, due to urban-development anarchy: while outdated policies rule, San Andrés Cholula becomes a perfect target for land developers’ predatory practices.

Soon after a new municipal president and council took over the administration of the municipality (in mid-October 2021), a group of villagers from the urban core and other peri-urban districts of Cholula demanded continuity of the work that started the previous year. On the one hand, they expressed the feeling of having been mocked by the previous municipal administration, which failed in its commitment to design—through inclusive processes—and to propose the new MPSUD, in order to prevent real estate companies from seizing the land [37]. On the other hand, the incoming municipal president has recently expressed an intention to issue two different MPSUDs: one for the historical urban core, and another for the cosmopolitan Angelópolis district, as traditions and identities in both areas should be respected [38]. What will happen in relation to the pending public-policy instruments is still unclear. Both land management and the new MPSUD are unaccomplished governmental triennial policies evidencing the failure of the administrations of being able to materialize them, converting them into debating arguments for political adversaries.

4. Literature Review: Legal Framework

Land Management Overview in Mexico

In Mexico, Articles 27, 73, and 115 [10] set out the Constitutional principles for land management. Article 27 establishes that the original ownership of all land and water in the national territory belong to the Nation (the State), which has created private property and has thus transferred ownership rights to individuals. Nevertheless, it is the Nation that has the power to regulate the use of natural resources and to “achieve a balanced development of the country and to improve the living conditions of rural and urban population” [39]. For this reason, the State shall issue measures.

“To put in order human settlements and to define adequate provisions, reserves and use of land, water and forest. Such measures shall seek construction of infrastructure; planning and regulation of the new settlements and their maintenance, improvement and growth; preservation and restoration of environmental balance; division of large rural estates; collective exploitation and organization of the farming cooperatives; development of the small rural property; stimulation of agriculture, livestock farming, forestry and other economic activities in rural communities; and to avoid destruction of natural resources and damages against property to the detriment of society” [39].

In addition, Article 27 commands the law’s obligation to protect the lands of Indigenous groups, and to protect ejido and communal lands.

Article 73 specifies that the General Congress of the United Mexican State (hereafter Congress of the Union) is the authority with the ability to legislate human settlements matters; that is to say, mandatory laws for Constitutional Article 27. Two laws of interest in this regard are the General Law of Human Settlements, Territorial Planning and Urban Development (hereafter GLHS), issued in 2016, and the General Law for Ecological Equilibrium and Environmental Protection (hereafter GLEEEP), issued in 1988.

Modern spatial planning in Mexico was first introduced in 1976, when the first General Law for Human Settlements [40] was implemented. At that time, the law focused on urban development and the regulation of informal settlements, and thus the territorial view for spatial planning was not considered. Due to emerging environmental awareness, this law was complemented in 1988 with the creation of the GLEEEP [41].

For the first time, land management was introduced as a tool for large-scale peri-urban and ecological management in Mexico. Salazar Izquierdo and Verdinelli [30] describe in Table 3 two important instruments that were developed: first, ecological land management (ELM), as an environmental policy to regulate land use and productive activities to improve the sustainability of natural resources [41,42]. Second, land planning (LP), meaning the land-management policy that integrates a socioeconomic strategy and articulates sectorial policies related to sustainable spatial-planning and development [26].

Table 3.

Land-management features in Mexico. Source: adapted from Salazar Izquierdo and Verdinelli [43].

According to the GLEEEP (Article 20bis 4) the objectives of the ELM are: (I) to determine the physical, biotic and socio-economic attributes of the different zones, in order to be able to elaborate diagnoses of the ecological conditions of their local activities; (II) to regulate land use outside urban settlements for preservation, restoration and sustainable management; and (III) to establish ecological regulation criteria for the environmental protection, preservation, restoration and sustainable development of human settlements, as a complement to urban-development plans.

Azuela [44] stresses that one legal loophole in ELM during the 80s was the lack of a legal foundation for land-use regulations. Thus, in 1996, when the general law was updated, the ELM had a regulatory status over land property. Azuela described equally important aspects of this legal modification: first, municipal authorities are accountable for local land management. It is noticeable that, since the amendment of the GLEEEP, the ELM instrument has been more popular and useful for rural communities and ejidos than for municipalities. Second, Azuela recognized that this modification created confusion between the purposes of urban planning and environmental planning. This condition was the result of a social demand promoted by environmental activists and organizations who believed urban planning was not compatible with environmental protection. For Azuela, the solution to this controversy was unique, because the GLEEEP created two types of territorial planning for rural and urban areas: urban plans are mandatory for urban settlements, and ELM is mandatory for the rest of the municipal territories [44].

To complement this, Salazar Izquierdo and Verdinelli [43] point out that LP remains at regional and national levels, and is not mandatory, while ELM can be regulated and implemented on a municipal scale. This is a key issue, because there is neither articulation nor integration among the different urban-development and ecological-land-management programs. However, communitarian ecological land management (CETM) is an instrument not entirely regulated, but successfully implemented. This method considers the integral participation of local stakeholders in developing consensus on land management issues. In this regard, CETM experiences are the most fruitful ones in land management, and thus the responsibility for implementation and regulation relies on rural communities. Meanwhile, municipal accountability in CETM stays in a legal grey-zone.

Constitutional Article 115 [10] specifies that the political and administrative organization of Mexico as a federal state is based on its division into municipalities. Each municipality is governed by a municipal council which has the power to organize the municipal public administration, and to regulate public procedures and services. These include (a) potable water, drainage and sewerage systems; (b) street lighting; (c) garbage disposal; (d) municipal markets; (e) cemeteries; (f) slaughterhouses; (g) streets, parks and gardens; (h) public security, and (i) others determined by state legislatures, and the management of their assets, which may include the yields generated by their properties, taxes and other revenues authorized by the state legislatures. Moreover, municipal councils have the constitutional power to plan, approve and handle urban development. In this sense, some of the responsibilities of the municipal authorities are to manage land-use development, to participate in the regularization of urban land-tenure, and to grant construction permits, etcetera. These duties are further established at federal level in the GLHS and at state level in the Law of Territorial Management and Urban Development (hereafter LTMUD) for the State of Puebla [33].

5. Results & Discussion

5.1. Statement 1: Self-Recognition of Indigenous Identity Has Enabled the Rural Population in San Andrés Cholula to Be Accountable forFurther Urban Development Planning Processes

This is a paradigmatic milestone in Puebla, and possibly in Mexico, notwithstanding the relevance of the real estate industry in the region, whose interests were crashed with the amparo sentence, after a decade of uncontrolled urban development, unsustainable land-use changes, and the expedition of corrupt construction-licenses.

Indigenous participation in land-management issues had happened before in the state of Puebla, specifically in 2009, in Cuetzalan del Progreso, where indigenous communities were involved in the design of the local ecological land-management program [20]. However, the experience of San Andrés Cholula in 2019 sets a precedent for the Indigenous population to be involved in the urban-development planning processes, even after selling off a municipality with a major urban spot immersed in neoliberal dynamics [33], in this case the metropolitan area of the city of Puebla.

Indigenous consultations applied to further decisions might not be the only and most-effective democratic tools that incorporate all the rural population’s needs, but it is the first and most immediate step for advancement in that direction. Additionally, Indigenous consultation and ecological land-management programs are the few legal instruments that local communities have at hand to protect their territory and environment.

Thus, in San Andrés Cholula, the rise of awareness among pueblos originarios is remarkable in three aspects: (1) the valorization of regional bio-cultural values; (2) the recognition of Indigenous land-rights against predatory urban-development practices; and (3) the pursuit of more sustainable and congruent urban-development practices in Cholula.

5.2. Statement 2: Altepetl Socio-Spatial Organization Is a Foundation for Inclusive Land Management

Cholula’s sistema de cargos (inherited from the ancient altepetl) is articulated through eight barrios and six juntas auxiliares for San Andrés Cholula (see Table 4), each with its own Catholic temple as a nodal points for socio-territorial order.

Table 4.

Cholula’s altepetl and territorial organization. Source: elaborated by the authors.

In the last 10 years, the barrios of San Andrés Cholula became progressively more proactive in socio-political matters, meaning that the mayordomías enable the use of the parishes and churches as spaces for community meetings, assemblies, and even social protests. As mayordomías are understood to be moral, ideological, and administrative authorities empowered by religious and civic symbols [14], neighbors actually assemble when the mayordomos ring the church-bell to call for a meeting, as in ancient times.

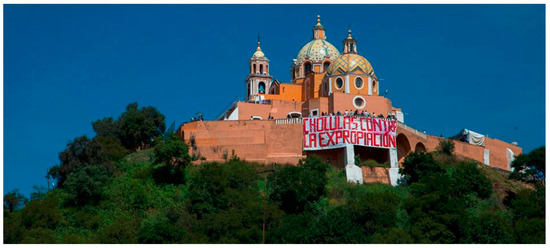

In 2014, the Great Pyramid of Cholula was used as a billboard to protest against land expropriations of 42 ancestral agricultural plots for their conversion into a public space with private areas, under the motto “Cholula against expropriation” (Figure 5). This experience evidences the fact that the altepetl structure is key to empowering the community in terms of embodying religious belief, a sense of community, and inherited tradition, to uplift the defense of ancestral territories and land uses.

Figure 5.

The Sanctuary of la Virgen de los Remedios over the Great Pyramid used as a billboard for social protest against expropriation. Source: Círculo de Defensa Cholula (2014).

On the other hand, the modern urban development of Angelópolis, despite being a former rural territory of San Andrés Cholula, does not have the circular system nor socio-spatial structure of altepetl. In this context, the rural land of the districts of San Antonio Cacalotepec, San Bernardino Tlaxcalancingo, San Francisco Acatepec and San Rafael Comac have been vulnerable to the predatory practices of the real-estate sector. Globalization and market trends are transforming San Andrés Cholula into a gentrified territory taken over by gated communities and shopping areas with new incomers that have no bonds with the ancient Cholula.

5.3. Statement 3: Indigenous Consultation Is a Legal Tool towards Inclusive Land Management

Karl [11] defines a spectrum of stakeholder engagement for participatory policy reform in achieving inclusive land management. The degrees of stakeholder participation range from contribution to information sharing, consultation, cooperation and consensus, decision-making, partnership and empowerment. Hence, consultation is not the expected final outcome of the participatory process, as decisions are still made by outsiders, and Indigenous communities have no assurance that their input will be used at this degree of participation. Nevertheless, consultation is an imperative action to empower Indigenous communities.

Moreover, in Mexico, Indigenous consultation is a constitutional right, set to ensure inclusive development planning and land-management processes. When violations to such a constitutional right occur, the amparo trial is an applicable legal procedure. This was the case for the inhabitants of San Rafael Comac, in San Andrés Cholula, whose Indigenous identity built upon a long history of socio-territorial tradition based on altepetl were acknowledged in the writ of amparo, with the main aim of preserving their resources, land, and culture, beyond any pursue of ethnical recognition. Thus, this was evidence that the formulation of the 2018 MPSUD violated their constitutional right to be consulted, and transgressed their right to preserve their land [11].

Indigenous consultation, according to Convention No. 169 of the International Labor Organization [45], “arises as a general obligation under the Convention, whenever legislative or administrative measures affect them directly”. It should take place “prior to exploration or exploitation of mineral and sub-surface resources”; “prior to relocation, which should take place only with the free and informed consent”; “when considering alienation or transmission of Indigenous peoples’ lands outside their own communities”; “on the organization and operation of special vocational training programs”; and “on literacy and educational programs and measures”.

The main principles that guide Indigenous consultation are: (1) good faith during the processes; (2) consultation must be carried out prior to planning; (3) participation must be with free will; (4) there must be access to sufficient information; (5) the consultation must be respectful concerning the Indigenous peoples’ culture and identity; (6) it must recognize that Indigenous peoples must be able to set their own conditions and requirements, based on their own conception of development when proposing alternative solutions; (7) it must be respectful of the way they generate consensus; (8) respectful of the way they develop their arguments and of the importance of their symbols; (9) respectful of the temporality of their own decision-making processes; (10) and local consent must be obtained from free, prior, and informed sources [32].

This is in line with the elements for promoting inclusive land management according to the Cities Alliance [46], including: the adoption of a participatory approach that emphasizes social interaction, learning and dialogue; building partnerships among different stakeholders; the use of methodologies that consider social and cultural norms; tailoring methodologies for vulnerable groups; and advancing towards securing tenure. Moreover, according to the International Labor Organization [45], even though Indigenous peoples have the same rights as other citizens, certain government measures may affect them directly, given that “the collective nature of Indigenous peoples’ rights and the need to safeguard their cultures and livelihoods are among the reasons why governments should adopt special measures for their consultation and participation in decision-making”.

5.4. Statement 4: Municipal Authorities Are Responsible for Integrating Indigenous Consultation into Urban Development Plans and Local Land Management

A means to advance towards inclusive land management is to work in line with the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (VGGT). The VGGT assert that states should “acknowledge that land, fisheries and forests have social, cultural, spiritual, economic, environmental and political value to Indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems”; “provide appropriate recognition and protection of the legitimate tenure rights of Indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems”; as well as “protect, promote and implement human rights, including as appropriate from the International Labor Organization Convention (No 169) concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” [45].

Beyond international, non-binding guidelines, the Mexican legal framework holds municipalities responsible and accountable for the inclusive formulation of land-management instruments. Land management laws GLHS (federal) and LTMUD (state) highlight the municipalities’ obligation to formulate, approve, administrate and execute municipal urban-development plans or programs, as well as to evaluate their compliance (Article 11, fraction I and Article 6, fraction I, respectively). Urban development and land-use plans or programs are mandatory for authorities and individuals (Article 10, LTMUD). The enforceability of urban-development plans or programs is responsibility of the federal, state and municipal authorities (Article 43, GLHS). To evaluate and review current urban-development programs, the Secretariat of Environment, Sustainable Development and Territorial Organization in the State of Puebla must integrate an evaluation system that helps to verify the effectiveness of the policies and the actions carried out (Article 58, LTMUD).

In addition, municipalities must create public consultation mechanisms to formulate, modify and evaluate municipal urban-development plans or programs, (Article 11, fraction XXII, GLHS). According to both federal and state laws, the authorities have the obligation to stimulate social participation when actions and constructions are executed, including those in Indigenous communities (Article 93, fraction IV and Article 178, fraction IV, respectively). This last obligation is connected to the constitutional requirement of Indigenous consultation regarding development plans. Accordingly, municipal governments compelled by the law to formulate and execute land-management plans or programs, specifically MPSUD and the Municipal Program of Ecological Land Management (MPELM) of San Andrés Cholula must undertake the constitutional obligation to ensure and carry out Indigenous consultation, which must be prior and informed.

In March 2020, soon after legal recognition of their Indigenous identity as built upon an old socio-territorial organization to preserve their resources, land, and culture was documented in the writ of amparo, the pueblos originarios in San Andrés Cholula formalized a protocol for Indigenous consultation whose objectives were: (1) to guarantee local community awareness of the possible effects of the MPSUD, MPELM and the Mobility Municipal Plan (MMP); (2) to ensure public authorities’ awareness and inclusion of solutions regarding the Indigenous peoples’ needs; (3) to analyze and include Indigenous peoples’ proposals; and (4) to obtain consent from the Indigenous peoples in relation to the final versions of the programs. Such protocol was signed by the then Secretary of Urban Development and by representatives of each pueblo originario in San Andrés Cholula.

The actions, legal norms and regulations described in this research manifest the obligation of Indigenous consultation that the municipality of San Andrés Cholula must comply with when municipal development plans and programs are to be formulated, now that pueblos originarios have been recognized by the local peoples and enforced by the writ of amparo. With respect to land-management matters, the issuing of not only a new MPSUD, but also a MPELM, which is still inexistent, is urgent. In both cases, the new municipal government will undertake the task; it should happen with enough clarity and real motivation to include local actors, and should not be based on good will, but on a constitutional mandate that the pueblos originarios have cleverly brought to the debate, in order to defend their land.

6. Conclusions

This paper aimed to explore the legal instruments to protect traditional communities in Mexico from urban-planning policies that prioritize the economic interests of a reduced group of stakeholders (real-estate investors and the tourist industry), at the expense of the exploitation of the material and intangible heritage of the local community. To do so, we conducted a review of the national and local legal-framework and policies, with a case study approach for San Andrés Cholula, based on a literature review.

We proceed to give answer to the research questions. (1) Regarding the understanding of pueblos originarios beyond ethnicity, in order to safeguard locals’ land rights and culture, San Andrés Cholula, that has a heterogeneous population, establishes a precedent for legal resistance by a community self-declared as a pueblo originario. This recognition enabled them to defend their land rights, whose origins they attribute to an ancient socio-territorial organizational system: the altepetl. The meaning of the pueblo originario category provides a valuable tool for communities such as San Andrés Cholula to make use of legal tools such as the writ of amparo in order to exercise their land rights. Until now, municipal development policies focused on revenue through taxation and construction permits, rather than land conflicts resolution. As a result, rural communities tend to be subject to land depredation—inflicted by irresponsible municipal authorities—and forced to sell their land to the best real-estate dealer. However, the case of San Andrés Cholula marks an important turning point in the advancement towards inclusive land-management policies.

(2) Regarding the founding role of ancient socio-spatial structures such as altepetl in the enforcement of land rights, the multidimensional (economic, social, political, environmental, cultural and religious) aspects of land are found in the pueblos originarios’ explanations regarding their origin being tied to the altepetl socio-spatial organization of San Andrés Cholula. Its unique territorial identity, based on beliefs (cosmogony), people (biocultural and socioeconomic aspects), and land (socio-spatial aspects) is still active, due to its deep Mesoamerican roots. In Cholula, mayordomías represent the highest hierarchy of each barrio, in which the community leaders will go beyond their religious duties to fight land injustices through the power given to them as the guardians of civic religious symbols (e.g., the Sanctuary of la Virgen de los Remedios on the Great Pyramid of Cholula). Mayordomías have been key in raising awareness and providing a space for the local community to gather, discuss and exercise their land rights. Such empowerment of ejidatarios, peasants and farmers based on the altepetl socio-spatial organization, has led them to question municipal authorities’ decisions on urban and economic growth. The case of San Rafael Comac in San Andrés Cholula was a cutting-edge case in terms of making use of the writ of amparo to demand an Indigenous consultation based on the constitutional right of Indigenous people, pueblos originarios, to be considered and heard in the planning and decision-making processes related to new urban-development plans. The exemplary case, in which strong legal tools such as the writ of amparo and Indigenous consultation endow inclusive management in peri-rural areas, was possible due to the existence of a robust and resilient socio-spatial organization inherited and enabled by the altepetl system.

Regarding the effectiveness of the writ of amparo as an instrument to advance towards inclusive land management, the amparo procedure is one of the few Mexican legal tools that guarantees the protection of human rights in a country with a historically weak legal framework. For many Indigenous communities, the writ of amparo stands out as the only way to protect natural resources and vulnerable natural areas against predatory urban-development practices. This was the case of San Rafael Comac, where locals, through an interpretation of the pueblo originario category and the use of the writ of amparo, were able to demand an Indigenous consultation as a strategy to reformulate the MPSUD and protect their land rights. As the writ of amparo was granted, the government is now held accountable for the protection of the San Rafael Comac community, and is responsible for their inclusion into the planning processes. This specific case demonstrates that the writ of amparo is an effective tool to work towards inclusive land management, environmental protection, and responsible governance of tenure in Latin America.

Finally, regarding the accountability of the municipal authorities for the advancement of inclusive land-tenure practices, the Mexican legal framework does not yet conceive environmental, spatial, rural and urban planning as areas for which municipal authorities are accountable. However, international voluntary guidelines do rely on the government as a guardian of the responsible governance of tenure and inclusive land-management practices that safeguard the land rights of Indigenous communities and other groups. In practice, local communities and rural towns find that ELM and LP are useful planning instruments against predatory urban-development practices. Furthermore, federal and state laws oblige local municipal authorities to comply with their constitutional duty regarding Indigenous consultation prior to the design of land-management plans and programs. In addition, as shown in the case of San Rafael Comac, the interpretation of an original identity to exercise the right to Indigenous consultations expands beyond strict ethnic criteria. This has been proven to be a valuable opportunity for rural and peri-urban communities to demonstrate their socio-cultural unicity and defend their rights.

Despite the undeniable advances in terms of the recognition and exercise of the land rights of multi-ethnical cultures, inclusive land management is still a pending issue in Mexico. Current regulations stress that Indigenous consultations should engage Indigenous peoples in decision-making processes on their own terms; however, the outcome of the reformulation of the MPSUD and the MPELM is unclear at this point. Although appropriate legal actions have been taken, and significant advancements in awareness raising and capacity building have been made by the pueblos originarios’ committee members through workshops and campaigns, the main goals regarding the defense of their land rights have not yet materialized in land-management programs.

Yet, the litigation process of the pueblos originarios in San Andrés Cholula based on the writ of amparo endowed by the traditional socio-spatial structures demonstrates that, even under a dominant post-colonial legal system, participatory approaches are key to achieving the recognition and exercising of the land rights of the vulnerable population. This experience corroborates the fact that when the state fails to protect and recognize land rights and self-determination, awareness and participation can contribute to the legal empowerment of Indigenous communities, beyond ethnicities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., M.G.V., A.K.K. and P.D.-D.; methodology, M.S., M.G.V.; validation, A.K.K., and P.D.-D.; formal analysis, M.S. and M.G.V.; investigation, M.S., M.G.V. and A.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and M.G.V.; writing—review and editing, M.S., M.G.V., A.K.K. and P.D.-D.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this research was funded by the Decanatura de Investigación y Posgrado of Universidad de las Américas Puebla.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the funding and academic support from the Decanatura de Investigación y Posgrado from Universidad de las Américas Puebla, especially to the Martín Alejandro Serrano Meneses, Israel Cedillo Lazcano, María del Rosario Rodríguez (MSc.) and Gabriela Solis (MSc.). We would like to thanks as well to the committee of Indigenous consultation for all the information provided and for their continuous engagement in the protection of San Andrés Cholula’s land rights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Tetra Tech. Effective Engagement with Indigenous Peoples: USAID Democracy, Human Rights, and governance sector guidance document. United States Agency for International Development. July 2020. Available online: https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2020_USAID_Effective-Engagement-with-Indigenous-Peoples-USAID-Sustainable-Landscapes-Sector-Guidance-Document.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- UNHU. Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights. In Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action; United Nations: Vienna, Austria, 1993; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/FactSheet16rev.1en.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Henckaerts, J.M.; Doswald-Beck, L. Customary International Humanitarian Law, 2009th ed.; International Committee of the Red Cross, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- UN and General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; United Nations: Paris, France, 1948; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights2 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- UN. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. June 1992. Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/background_publications_htmlpdf/application/pdf/conveng.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- General Assembly. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. In General Assembly Resolution 2106 (XX); General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. December 1966. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Gilbert Ben, J.B.-C. ‘Mapping for Rights’: Indigenous Peoples, Litigation and Legal Empowerment. Erasmus Law Rev. 2018, 1, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de la Unión, H. Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos; 25 Legislatura Cámara de Diputados: Mexico City, Mexico, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- de la Federación, P.J. Versión Pública de la Sentencia de Amparo Indirecto 1490/2019; Juzgado Segundo de Distrito en Materia de Amparo Civil, Administrativa y de Trabajo y Juicios Federales en el Estado de Puebla: San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, M.T. Esencialismo y autonomía: Paradojas de las reivindicaciones indígenas. Alteridades 1997, 7, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, M.; Durán-Díaz, P.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Gutiérrez-Juárez, E.; González-Rivas, D.A. Evolution and collapse of ejidos in Mexico-To what extent is communal land used for urban development? Land 2019, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Díaz, P.; Morales, E.R.; Schumacher, M. Using urban literacy to strengthen land governance and women’s empowerment in peri-urban communities of San Andrés Cholula, Mexico. In Land Governance and Gender: The Tenure-Gender Nexus in Land Management and Land Policy; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2021; pp. 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C. Tourism and Indigenous Heritage in Latin America, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Santos, B. Descolonizar el Saber, Reinventar el Poder, 2010th ed.; Ediciones Trilce: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Carías, R. Constitutional Protection of Human Rights in Latin America; Cambridge University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Jacob, E. Las Comunidades de Michoacán y el Juicio de Amparo como Defensa de sus Recursos Naturales, Durante el Porfiriato; Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo: Morelia, Mexico, 2015; Available online: http://bibliotecavirtual.dgb.umich.mx:8083/xmlui/bitstream/handle/DGB_UMICH/690/FDCS-M-2015-2301.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Durán-Díaz, P.; Armenta-Ramírez, A.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M. Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico. Land 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, G.G. Altepetl: Cholula’s Great Pyramid as ‘Water-Mountain’. In Flowing through Time: Exploring Archaeology through Humans and Their Aquatic Environment; Steinbrenner, A.L., Cripps, B., Georgopulos, M., Carr, J., Eds.; University of Calgary Press: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2008; pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Christlieb, F. Landschaft, pueblo and altepetl: A consideration of landscape in sixteenth-century Central Mexico. J. Cult. Geogr. 2015, 32, 331–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescano, E. El Altépetl. Fractal 2006, XI, 11–50. Available online: https://www.mxfractal.org/F42Florescano.htm (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Corona-Jiménez, O. Organización Cívico-Religiosa: La Mayordomía del Circular de la Virgen de los Remedios. Realizada por el Barrio Tradicional de Jesús Nazareno Taltempán, en el Municipio de San Pedro Cholula; Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla: Puebla, Mexico, 2014; Available online: https://repositorioinstitucional.buap.mx/handle/20.500.12371/6954 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- McCafferty, G.G. Mountain of heaven, mountain of earth: The Great Pyramid of Cholula as sacred landscape. In Landscape and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 279–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell. Cholula: Su herencia en una red de agujeros. Elementos Ciencia y Cultura 2004, 11, 3–11. Available online: https://elementos.buap.mx/directus/storage/uploads/00000002632.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Ashwell. Cholula: La Ciudad Sagrada en la Modernidad; Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades “Alfonso Vélez Pliego”: Puebla, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell; O’Leary, J. Cholula, la Ciudad Sagrada; Volkswagen de México: Puebla, Mexico, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- H. Ayuntamiento San Andrés Cholula. Programa Municipal de Desarrollo Urbano Sustentable de San Andrés Choolula; H. Ayuntamiento San Andrés Cholula, Secretaría de Desarrollo Rural Sustentabilidad y Ordenamiento Territorial: Cholula, Mexico, 2018; Available online: https://sach.gob.mx/files/transparencia/marco_normativo/Plan%20Municipal%20de%20Desarrollo%20Urbano%20Version%20Completa.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Gobierno del Estado de Puebla. Modificación Parcial al Programa Subregional de Desarrollo Urbano para los municipios de Cuautlancingo, Puebla, San Andrés Cholula y San Pedro Cholula. Puebla. 2011. Available online: https://ti.implanpuebla.gob.mx/CartaUrbanaDigital/docs/p_subregional_desarrollo_urb.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Secretaría de Finanzas y Administración. Actualización del Programa Regional de Desarrollo, Región Angelópolis 2011-2017; Gobierno del Estado de Puebla: Puebla, Mexico, 2011; Available online: http://planeader.puebla.gob.mx/pdf/programas/estatales/regionales/IN.54.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Núñez, E. Grupo Proyecta va por la Expansión de Lomas de Angelópolis en los cerros de La Sombra y El Tenayo; Opositores Acusan Intimidación de la Inmobiliaria. La Jornada de Oriente, Puebla. 2021. Available online: https://www.lajornadadeoriente.com.mx/puebla/grupo-proyecta-lomas-de-angelopolis-cerros/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- INPI. Consulta a los Pueblos Indígenas. 2018. Available online: http://www.inpi.gob.mx/transparencia/gobmxinpi/participacion/documentos/consulta_pueblos_indigenas.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Juárez, E.G.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M.; Villalvazo, M.G.; Meza, E.G.; Durán-Díaz, P. Neoliberal Urban Development vs. Rural Communities: Land Management Challenges in San Andrés Cholula, Mexico. Land 2022, 11, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Panorama Sociodemográfico de Puebla. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020; INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento Constitucional del Municipio de San Andrés Cholula, P.H. Sesión Extraordinaria de Cabildo Celebrada el día 13 de octubre del 2020. Available online: https://sach.gob.mx/files/transparencia/actas_cabildo/2020/octubre/ACTA_S_EXTRA_13_10_2020.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Ayuntamiento San Andrés Cholula, H. Sesión Extraordinaria de Cabildo 28 de octubre de 2020. Acta de cabildo. 2020. Available online: https://sach.gob.mx/files/transparencia/actas_cabildo/2020/octubre/ACTA_S_EXTRA_13_10_2020.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Velázquez León, L. Exigen a Tlatehui, Continuidad en Programa de Desarrollo Urbano. Síntesis, Puebla. 2021. Available online: https://sintesis.com.mx/puebla/2021/10/12/exigen-tlatehui-continuidad/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Balcázar Placeres, C. San Andrés Cholula Tendrá dos Planes de Desarrollo Urbano, Revela Tlatehui. Ángulo 7. 2021. Available online: https://www.angulo7.com.mx/2021/10/18/san-andres-cholula-tendra-2-planes-de-desarrollo-tlatehui/ (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- IIJ UNAM. Political Constitution of the United Mexican States (English Translation); Institutio de Investigaciones Jurídicas UNAM. 2015. Available online: https://www2.juridicas.unam.mx/constitucion-reordenada-consolidada/en/vigente (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- de Diputados. Ley General de Asentamientos Humanos, Ordenamiento Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano. H. Congreso de la Unión. 2015. Available online: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGAHOTDU_140519.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- H. Congreso de la Unión. Ley General de Equilibrio Ecológico y Protección al Medio Ambiente. 1988. Available online: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/148_180121.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- SEMARNAT. Qué es un Ordenamiento Ecológico del Territorio? 2016. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/articulos/que-es-un-ordenamiento-ecologico-del-territorio (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Salazar, M.T.S.; Izquierdo, J.M.C.; Verdinelli, G.B. La política de ordenamiento territorial en México: De la teoría a la práctica. Reflexiones sobre sus avances y retos a futuro. In La Política de Ordenamiento Territorial en México: De la Teoría a la Práctica; Instituto Nacional de Ecología: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013; pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Azuela. El ordenamiento territorial en la legislación mexicana. In Legislación, Normatividad y Enseñanza; Sánchez-Salazar, C.I., Bocco, G.V., Eds.; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013; Available online: http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones2/libros/699/ordenamiento.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Labour Organization. Procedures for Consultations with Indigenous Peoples. Experiences from Norway. Geneva. 2016. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---gender/documents/publication/wcms_534668.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Cities Alliance. Promoting Inclusive Land Management: Key Elements. Promoting Inclusive Land Management: Key Elements. 2018. Available online: https://www.citiesalliance.org/resources/multimedia/infographics/promoting-inclusive-land-management-key-elements (accessed on 16 November 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).