Small Cultural Forests: Landscape Role and Ecosystem Services in a Japanese Cultural Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- evaluate the current landscape role and monitor the landscape changes affecting igune and other small woods in the last 20 years;

- (2)

- assess the related ESs through a literature analysis of papers referring to the same study area;

- (3)

- demonstrate that the iconic features of a cultural landscape can still have multiple roles and offer ESs to the local population, even after centuries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Multitemporal and Spatial Analyses

2.2.2. Literature Analysis

3. Results

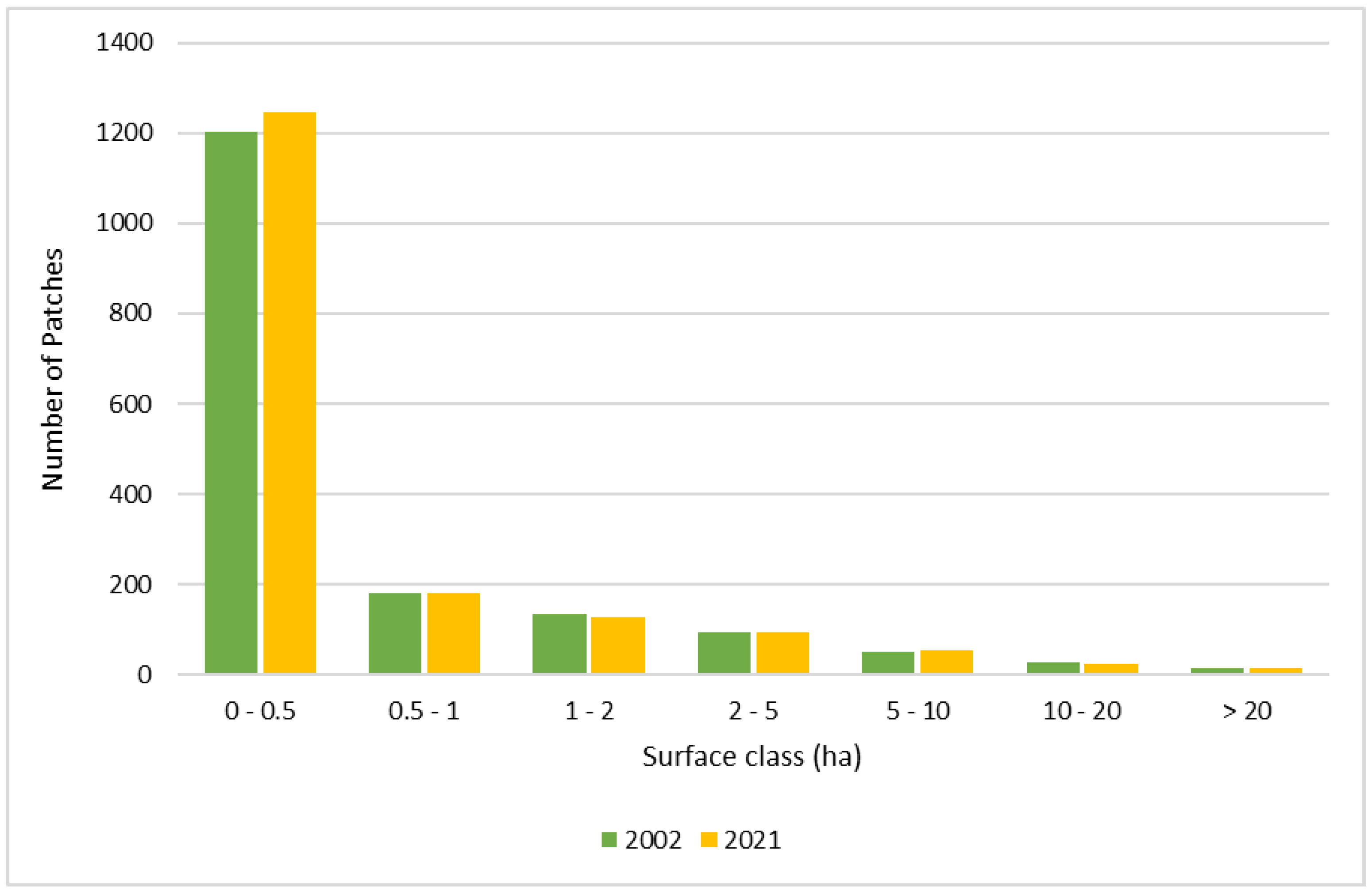

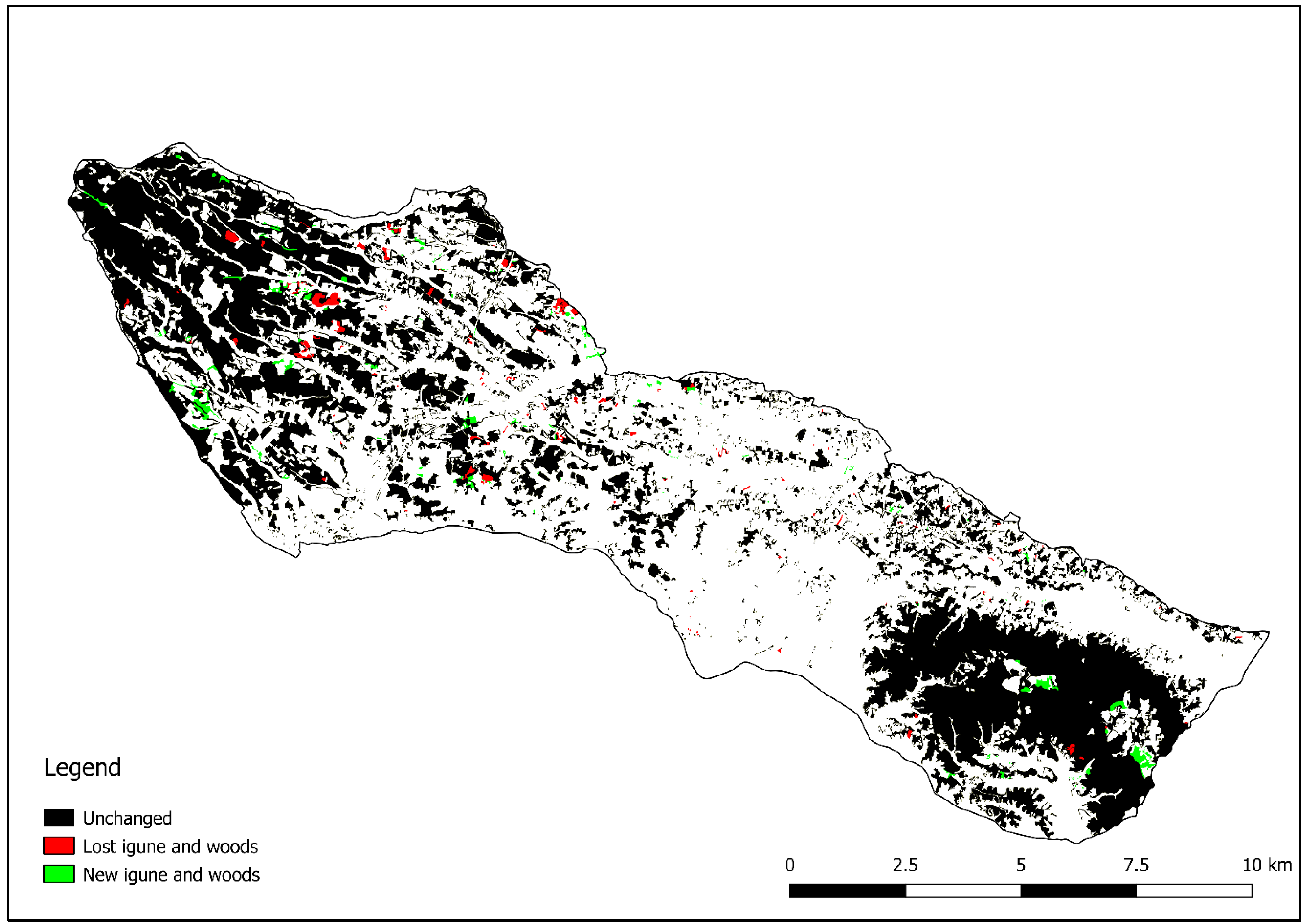

3.1. Identification and Mapping of Igune and Other Small Woods

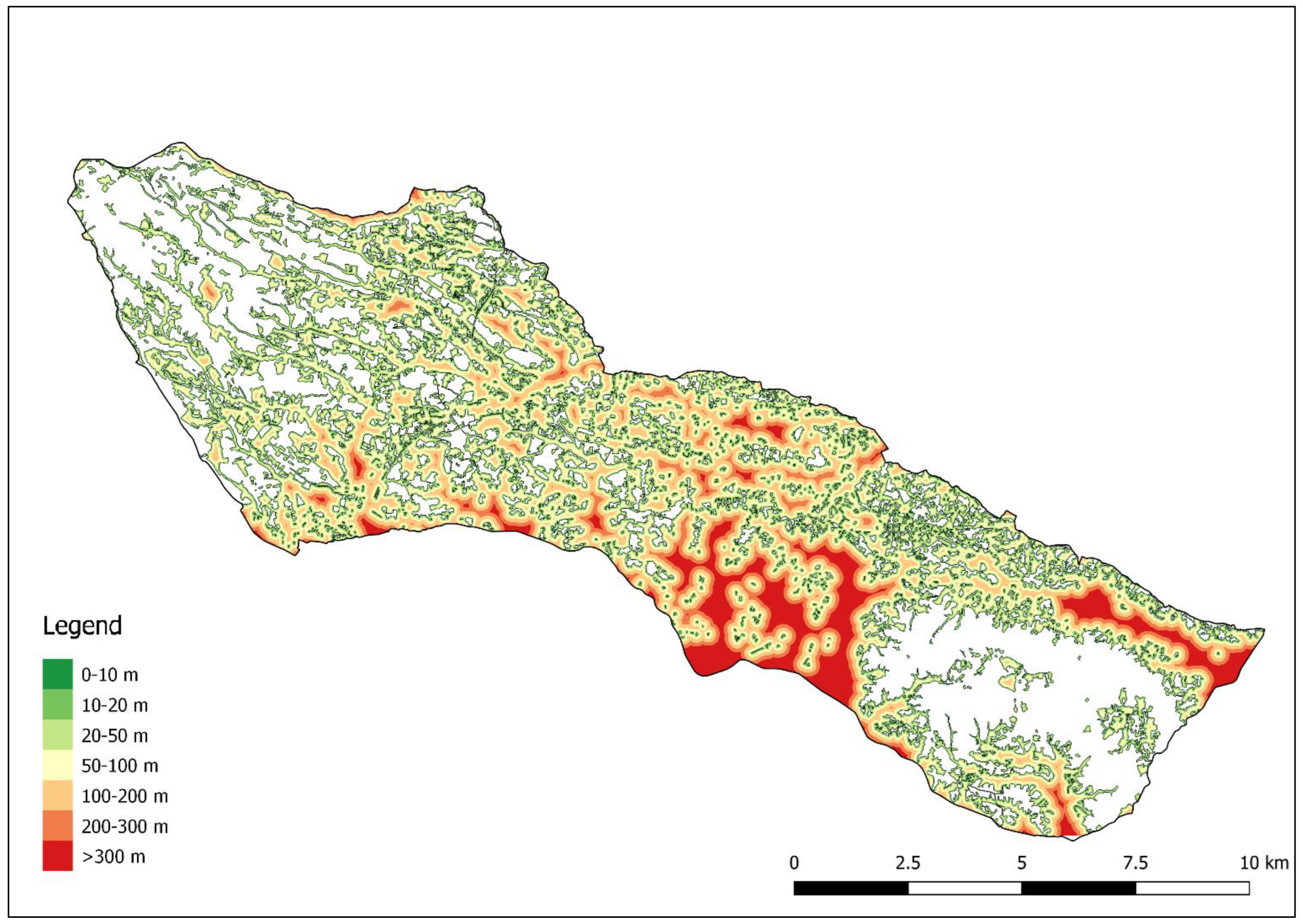

3.2. Proximity Analysis

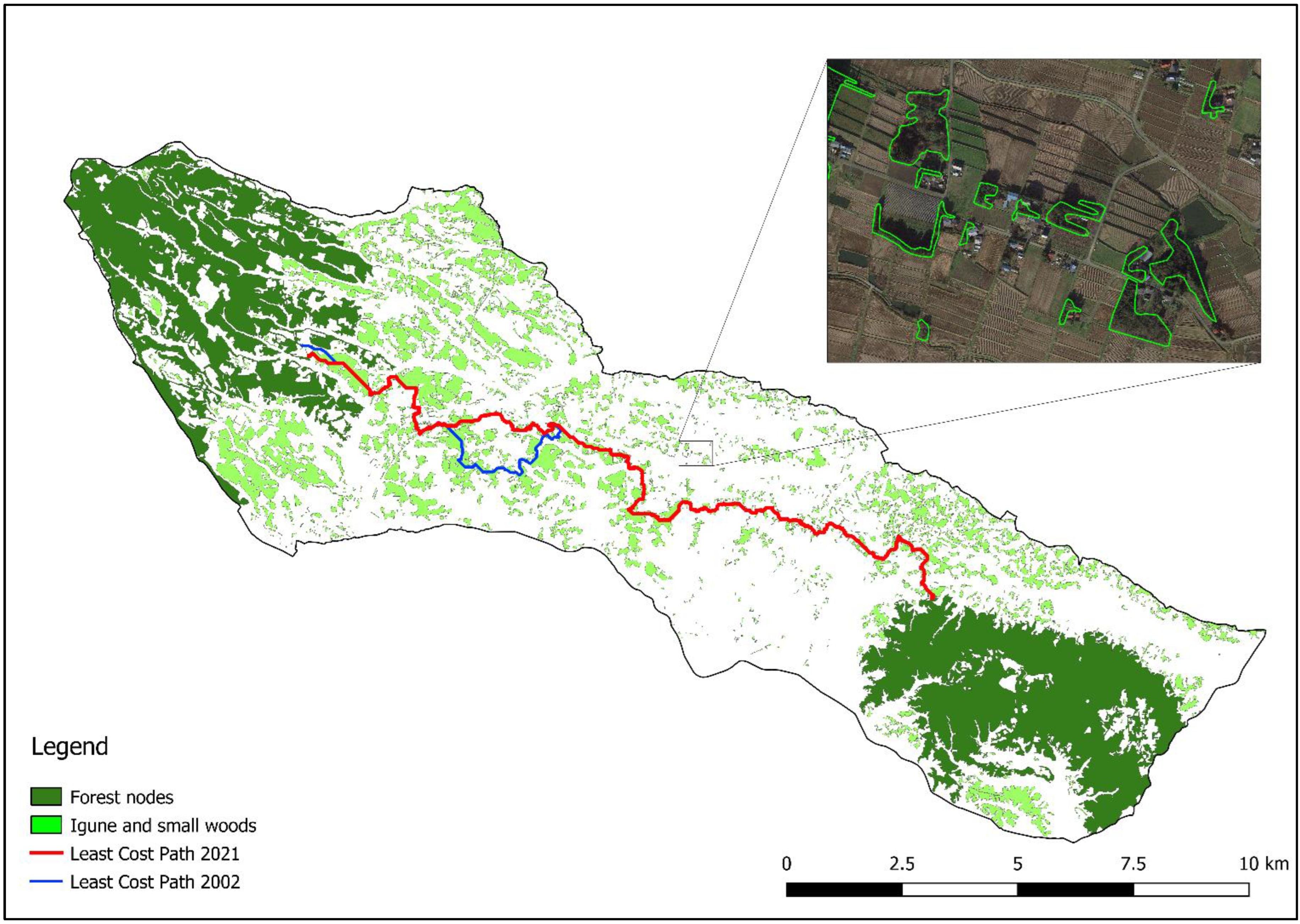

3.3. Least-Cost Path Analysis

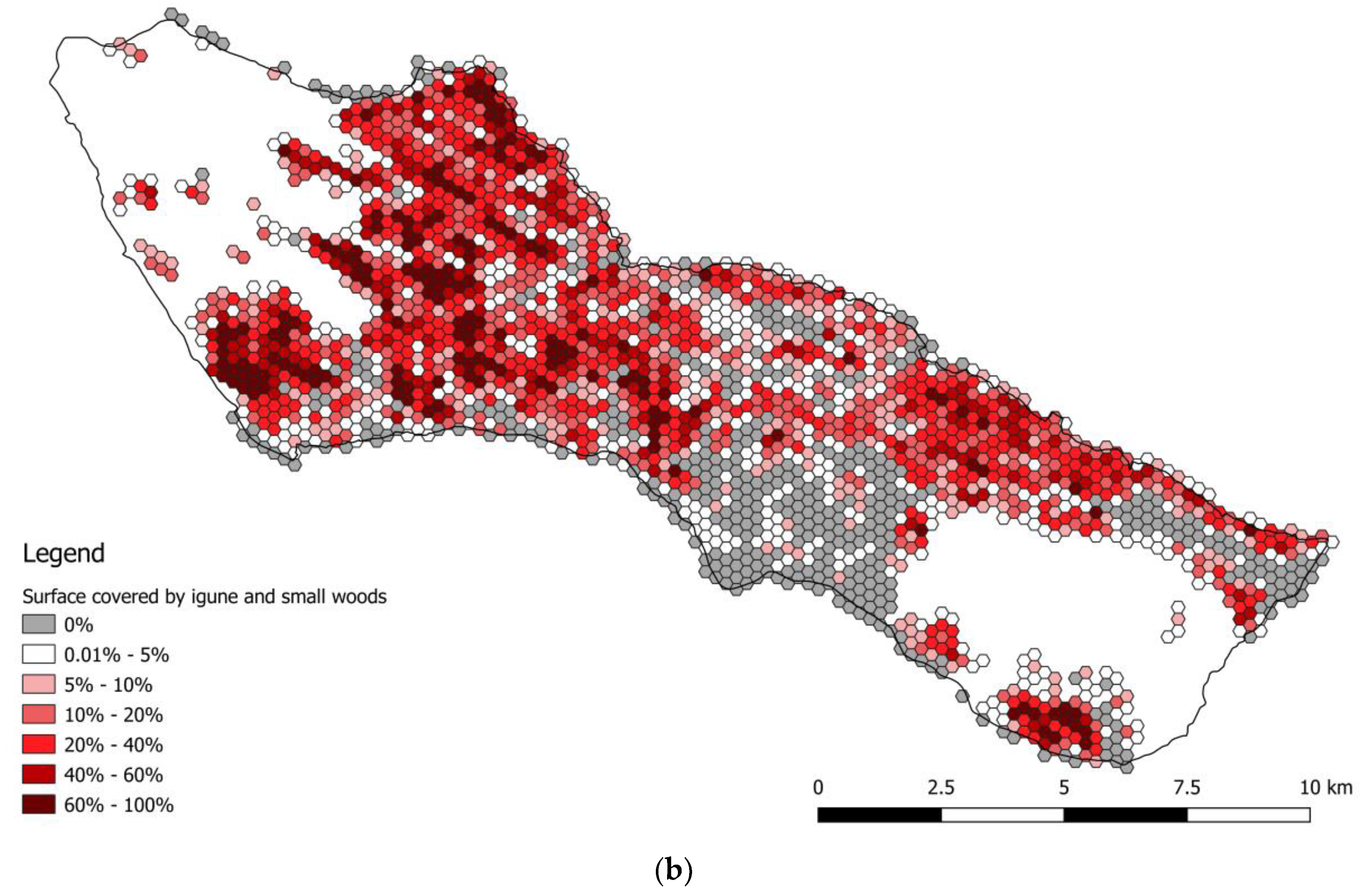

3.4. Density Analysis

3.5. Literature Analysis

4. Discussion

| Ecosystem Services | 1. Provisioning services | 1.1 Food and livelihood—including fruits and wild foods |

| 1.2 Timber and fuelwoods | ||

| 1.4 Ingredients for traditional medicine | ||

| 2. Regulating services | 2.1 Climate regulation (local) | |

| 2.2 Plant disease and pest regulation—igune offer suitable habitat for rice pests’ natural predators. | ||

| 2.3 Wind protection—the main traditional role of the igune allow secondary production protected by the north wind. | ||

| 2.4 Ecological role—igune act as both biodiversity hotspot and stepping stones, connecting two forest nodes. | ||

| 3. Cultural services | 3.1 Traditional landscape and aesthetic value | |

| 3.2 Traditional knowledge systems, cultural heritage and sense of place—shrines and cemetery often lays near igune. |

5. Conclusions

- Landscape: igune and other small woods still deeply characterize the local cultural landscape (satoyama), which otherwise would be merely an intensive agricultural landscape, like many others in plain areas.

- Ecological network: igune and other small woods act as stepping stones connecting large forest patches.

- Biodiversity hotspots: a particularly high number of trees and shrubs species can be found inside igune and other small woods, but igune also represent key habitats for spiders, frogs, and other rice pests’ natural predators that contribute to the agroecosystem balance.

- Wind protection: the original role of igune is still important in the area to allow secondary production of vegetables near the farmhouses to integrate the local population diet.

- Wood and non-wood forest products: igune and other small woods provide multiple products to local farmers, including timber, firewood, fruits, ingredients for traditional medicine, and food.

- Cultural role: small shrines are often located within igune, demonstrating their strict connection with the local culture.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sauer, C. The Morphology of Landscape. University of California Publications in Geography. In Land and Life: A Selection from the Writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1925; Volume 2.2. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. The European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000.

- Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe (MCPFE). In State of Europe’s Forests 2003; MCPFE Liaison Unit: Vienna, Austria, 2003.

- Agnoletti, M.; Anderson, S.; Johann, E. Guidelines for the Implementation of Social and Cultural Values in Sustainable Forest Management: A Scientific Contribution to the Implementation of MCPFE–Vienna Resolution 3; IUFRO Occasional Paper 19; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; CBD Secretariat (SCBD). UNESCO–CBD Joint Program between Biological and Cultural Diversity; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010.

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggering, H.; Müller, K.; Werner, A.; Helming, K. The Concept of Multifunctionality in Sustainable Land Development. In Sustainable Development of Multifunctional Landscapes; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Chen, B.; Takemoto, K. Conservation of terraced paddy fields engaged with multiple stakeholders: The case of the Noto GIAHS site in Japan. Paddy Water Environ. 2014, 12, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Masumoto, T.; Matsui, H.; Kato, T.; Sato, Y. Prospects for multifunctionality of paddy rice cultivation in Japan and other countries in monsoon Asia. Paddy Water Environ. 2006, 4, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohafkan, P.; Altieri, M.A. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems: A Legacy for the Future; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, P.S. Globally Important Ingenious Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS): An Eco-Cultural Landscape Perspective; GIAHS Background Document; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Bertani, R.; Agnoletti, M. A review of the role of forests and agroforestry systems in the FAO Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) programme. Forests 2020, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M.; Urbanization. Our World Data. 2018. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Holt-Giménez, E. Can We Feed the World without Destroying It? John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. Study Progress of Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (IAHS): A Literature Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Nakashizuka, T.; Oguro, M. Environmental factors affecting the composition and diversity of the avian community in igune, a traditional agricultural landscape in northern Japan. J. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 41, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hidalgo, P.J.; Hernández, H.; Sánchez-Almendro, A.J.; López-Tirado, J.; Vessella, F.; Porras, R. Fragmentation and Connectivity of Island Forests in Agricultural Mediterranean Environments: A Comparative Study between the Guadalquivir Valley (Spain) and the Apulia Region (Italy). Forests 2021, 12, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noss, R.F. Landscape Connectivity: Different Functions at Different Scales. In Landscape Linkages and Biodiversity; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- With, K.A.; Gardner, R.H.; Turner, M.G. Landscape connectivity and population distributions in heterogeneous environments. Oikos 1997, 78, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.D.; Fahrig, L.; Henein, K.; Merriam, G. Connectivity is a vital element of landscape structure. Oikos 1993, 68, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, F.F.; De Carvalho, D.; Rhodes, J.; Archibald, C.L.; Rezende, V.L.; Van den Berg, E. Small Landscape Elements Double Connectivity in Highly Fragmented Areas of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiang, D.C.F.; Morris, A.; Bell, M.; Gibbins, C.N.; Azhar, B.; Lechner, A.M. Ecological connectivity in fragmented agricultural landscapes and the importance of scattered trees and small patches. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Landscape modification and habitat fragmentation: A synthesis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007, 16, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, D.; Ryan, S.J.; Beier, P.; Cushman, S.A.; Dieffenbach, F.; Epps, C.W.; Gerber, L.; Hartter, J.; Jenness, J.; Kintsch, J.; et al. The role of landscape connectivity in planning and implementing conservation and restoration priorities. Issues Ecol. 2012, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tischendorf, L.; Fahrig, L. On the usage and measurement of landscape connectivity. Oikos 2000, 90, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural values and sustainable forest management: The case of Europe. J. For. Res. 2015, 20, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Piras, F.; Venturi, M.; Santoro, A. Cultural values and forest dynamics: The Italian forests in the last 150 years. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 503, 119655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrotta, J.A.; Agnoletti, M. Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge and Climate Change. In Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2012; pp. 491–533. [Google Scholar]

- Parrotta, J.A.; Fui, H.L.; Jinlong, L.; Ramakrishnan, P.S.; Youn, Y.C. Traditional forest-related knowledge and sustainable forest management in Asia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1987–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marentes, M.A.H.; Venturi, M.; Scaramuzzi, S.; Focacci, M.; Santoro, A. Traditional forest-related knowledge and agrobiodiversity preservation. The case of the chagras in the Indigenous Reserve of Monochoa (Colombia). Biodivers. Conserv. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Census Data. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/japan/miyagi/ (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Osaki Region Committee for the Promotion of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems. Osaki Kōdo’s Traditional Water Management System for Sustainable Paddy Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/CA3168EN/ca3168en.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- McCarigal, K.; Cushman, S.A.; Neel, M.C.; Ene, E. FRAGSTATS: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Categorical Maps, version 3.0; University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McCarigal, K.; Marks, B.J. FRAGSTATS: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Quantifying Landscape Structure; General Technical Report PNW-GTR-351; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Adamczyk, J.; Tiede, D. ZonalMetrics—A Python toolbox for zonal landscape structure analysis. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 99, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, M.; Piras, F.; Corrieri, F.; Fiore, B.; Santoro, A.; Agnoletti, M. Assessment of Tuscany Landscape Structure According to the Regional Landscape Plan Partition. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullin, A.S.; Stewart, G.B. Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, S. Review of methodology of quantitative reviews using meta-analysis in ecology. J. Anim. Ecol. 2002, 71, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Salisbury, J.G.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Maindonald, J.; Douglas, R. Can methods applied in medicine be used to summarize and disseminate conservation research? Environ. Conserv. 2004, 31, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washitani, I. Traditional sustainable ecosystem ‘SATOYAMA’ and biodiversity crisis in Japan: Conservation ecological perspective. Global Environ. Res. 2001, 5, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Sakai, S.; Takahashi, T. Factors maintaining species diversity in satoyama, a traditional agricultural landscape of Japan. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1930–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, H.; Primack, R.B. Participatory conservation approaches for satoyama, the traditional forest and agricultural landscape of Japan. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2003, 32, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Hotes, S.; Ichinose, T.; Doko, T.; Wolters, V. Hotspots of Agricultural Ecosystem Services and Farmland Biodiversity Overlap with Areas at Risk of Land Abandonment in Japan. Land 2021, 10, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Hirano, T. Breeding records and nesting habitats of the Japanese lesser sparrowhawk Accipiter gularis in residential area of Tochigi prefecture Honshu Japan. Jpn. J. Ornithol. 1990, 39, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Osawa, S.; Katsuno, T. The distribution of frogs on paddies locating different landforms in alluvial fan area. J. Rural. Plan. Assoc. 2001, 19, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Osawa, S.; Nanaumi, E. The characteristics of the premises forests, known as Igune, and the damage caused by recent tsunamis to the forests around the Okuma district, Watari town, in the central region of the Sendai plains. J. Jpn. Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 78, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hirabuki, Y.; Fukuda, A. Farmstead groves and traditional Lifestyle. 1. Development process of two environmental educational programs based on local area field trail results. Proc. Miyagi Univ. Educ. 2006, 9, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Koganezawa, T.; Kitagawa, N.; Kato, Y. Environmental education and Igune school. Proc. Miyagi Univ. Educ. 2002, 4, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibai, N.; Fukamachi, K.; Oku, H.; Shibata, S. Residents’ perception and measures for conservation of homestead woodlands in the Tonami Plain, Japan. J. Jpn. Inst. Landsc. Arch. 2018, 81, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Syrbe, R.U.; Walz, U. Spatial indicators for the assessment of ecosystem services: Providing, benefiting and connecting areas and landscape metrics. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 21, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrbe, R.U.; Bastian, O.; Röder, M.; James, P. A framework for monitoring landscape functions: The Saxon Academy Landscape Monitoring Approach (SALMA), exemplified by soil investigations in the Kleine Spree floodplain (Saxony, Germany). Landscape 2007, 79, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A.; Blaschke, T.; Haase, D.; Herzog, F.; Syrbe, R.U.; Tischendorf, L.; Walz, U. Understanding and quantifying landscape structure–A review on relevant process characteristics, data models and landscape metrics. Ecol. Model. 2015, 295, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, A.B.; Ahern, J. Applying landscape ecological concepts and metrics in sustainable landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, F.; Lausch, A. Supplementing land-use statistics with landscape metrics: Some methodological considerations. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2001, 72, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenar, J.B.; Bolowich, A.; Elliot, T.; Geneletti, D.; Sonnemann, G.; Rugani, B. Assessing habitat loss, fragmentation and ecological connectivity in Luxembourg to support spatial planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, C.M.; Rocha, J. Evaluating Dominant Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Predicting Future Scenario in a Rural Region Using a Memoryless Stochastic Method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Emanueli, F.; Corrieri, F.; Venturi, M.; Santoro, A. Monitoring Traditional Rural Landscapes. The Case of Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, Å.; Miller, D. Analysing the relationship between indicators of landscape complexity and preference. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2011, 38, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GCTE. Focus 4: Global Change and Ecological Complexity, Draft 5, dated 22 March 1996. In Ecological Studies; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, F. Modelling indicators and indices of landscape complexity: An approach using GIS. Ecol. Indic. 2002, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, Å.; Hagerhall, C.; Sang, N. Analysing visual landscape complexity: Theory and application. Landsc. Res. 2010, 35, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, A.E.; Kedron, P. Landscape metrics: Past progress and future directions. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2017, 2, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plexida, S.G.; Sfougaris, A.I.; Ispikoudis, I.P.; Papanastasis, V.P. Selecting landscape metrics as indicators of spatial heterogeneity—A comparison among Greek landscapes. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 26, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, F.; Lausch, A. Prospects and limitations of the application of landscape metrics for landscape monitoring. In Heterogeneity in Landscape Ecology: Pattern and Scale, Proceedings of the 8th Annual Conference of the International Association of Landscape Ecology, Bristol, UK, 6–8 September 1999; Maudsley, M., Marshall, J., Eds.; IALE: Scotland, UK, 1999; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2000; Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- de Foresta, H.; Somarriba, E.; Temu, A.; Boulanger, D.; Feuilly, H.; Gauthier, M.; Taylor, D. Towards the Assessment of Trees Outside Forests: A Thematic Report Prepared in the Framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guariguata, M.R.; Ostertag, R. Neotropical secondary forest succession: Changes in structural and functional characteristics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 148, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, R.T. What is secondary forest? J. Trop. Ecol. 1994, 10, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoate, C.; Boatman, N.; Borralho, R.; Carvalhob, C.R.; de Snoo, G.R.; Eden, P. Ecological impacts of arable intensification in Europe. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 63, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanAcker, M.C.; Little, E.A.; Molaei, G.; Bajwa, W.I.; Diuk-Wasser, M.A. Enhancement of risk for lyme disease by landscape connectivity, New York, New York, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minor, E.S.; Tessel, S.M.; Engelhardt, K.A.; Lookingbill, T.R. The role of landscape connectivity in assembling exotic plant communities: A network analysis. Ecology 2009, 90, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Shang, H.; Cheng, J. Landscape connectivity shapes the spread pattern of the rice water weevil: A case study from Zhejiang, China. Environ. Manag. 2011, 47, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board, M.A. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; New Island: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Symbol | Formula | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patches | NP | Total number of patches. | ||

| Mean Patch Size | MPS | MPS = ai/ni ai = area of the i land use class in hectares; ni = number of the i land use patches. | Average area of a patch of a particular class. | [34] |

| Patch Density | PD | PD = Ni/A * 100 Ni = total number of patches of the i class; A = total surface of the study area in hectares. | Number of patches of a particular class calculated on the total surface of the study area excluding the forest nodes (standardized per 100 ha). | [35] |

| Landscape Shape Index | LSI | LSI = pi/(2 * √(π*ai)) pi = perimeter of the patch i in meters; ai = area of the patch i in hectares. | Derived from the Edge Density, it evaluates the degree of fragmentation through segmentation of edge. LSI increases without limit as the patch becomes more disaggregated. | [35] |

| Year | Total surface | NP | MPS | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2115.6 | 1703 | 1.24 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.64 |

| 2021 | 2075.5 | 1737 | 1.19 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.60 |

| Year | Total Length (m) | Length Inside Igune and Small Woods (%) | Length Outside Igune and Small Woods (%) | Number of Igune and Small Woods Crossed by LCP | Maximum Length of LCP Segments Falling Outside Igune and Small Woods (m) | Average Length of LCP Segments Falling Outside Igune and Small Woods (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 23,647 | 91.1% | 8.9% | 73 | 92 | 28 |

| 2021 | 21,918 | 90.3% | 9.7% | 75 | 88 | 28 |

| Igune and Other Small Woods Patch Count Per Hexagon | Number of Hexagons 2002 | Number of Hexagons 2021 | Igune and Other Small Woods Surface Per Hexagon | Number of Hexagons 2002 | Number of Hexagons 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 430 | 423 | 0% | 433 | 427 |

| 1 | 680 | 662 | 0.1–10% | 646 | 652 |

| 2 | 482 | 489 | 10–20% | 332 | 335 |

| 3 | 289 | 283 | 20–30% | 249 | 247 |

| 4 | 184 | 186 | 30–40% | 180 | 174 |

| 5 | 87 | 95 | 40–50% | 116 | 107 |

| 6 | 38 | 36 | 50–60% | 82 | 87 |

| 7 | 10 | 12 | 60–70% | 78 | 77 |

| 8 | 6 | 6 | 70–80% | 41 | 38 |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 80–90% | 26 | 26 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 90–100% | 25 | 24 |

| Total | 2208 | 2194 | Total | 2208 | 2194 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piras, F.; Fiore, B.; Santoro, A. Small Cultural Forests: Landscape Role and Ecosystem Services in a Japanese Cultural Landscape. Land 2022, 11, 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091494

Piras F, Fiore B, Santoro A. Small Cultural Forests: Landscape Role and Ecosystem Services in a Japanese Cultural Landscape. Land. 2022; 11(9):1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091494

Chicago/Turabian StylePiras, Francesco, Beatrice Fiore, and Antonio Santoro. 2022. "Small Cultural Forests: Landscape Role and Ecosystem Services in a Japanese Cultural Landscape" Land 11, no. 9: 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091494

APA StylePiras, F., Fiore, B., & Santoro, A. (2022). Small Cultural Forests: Landscape Role and Ecosystem Services in a Japanese Cultural Landscape. Land, 11(9), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091494