What Is Farmers’ Level of Satisfaction under China’s Policy of Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketisation?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

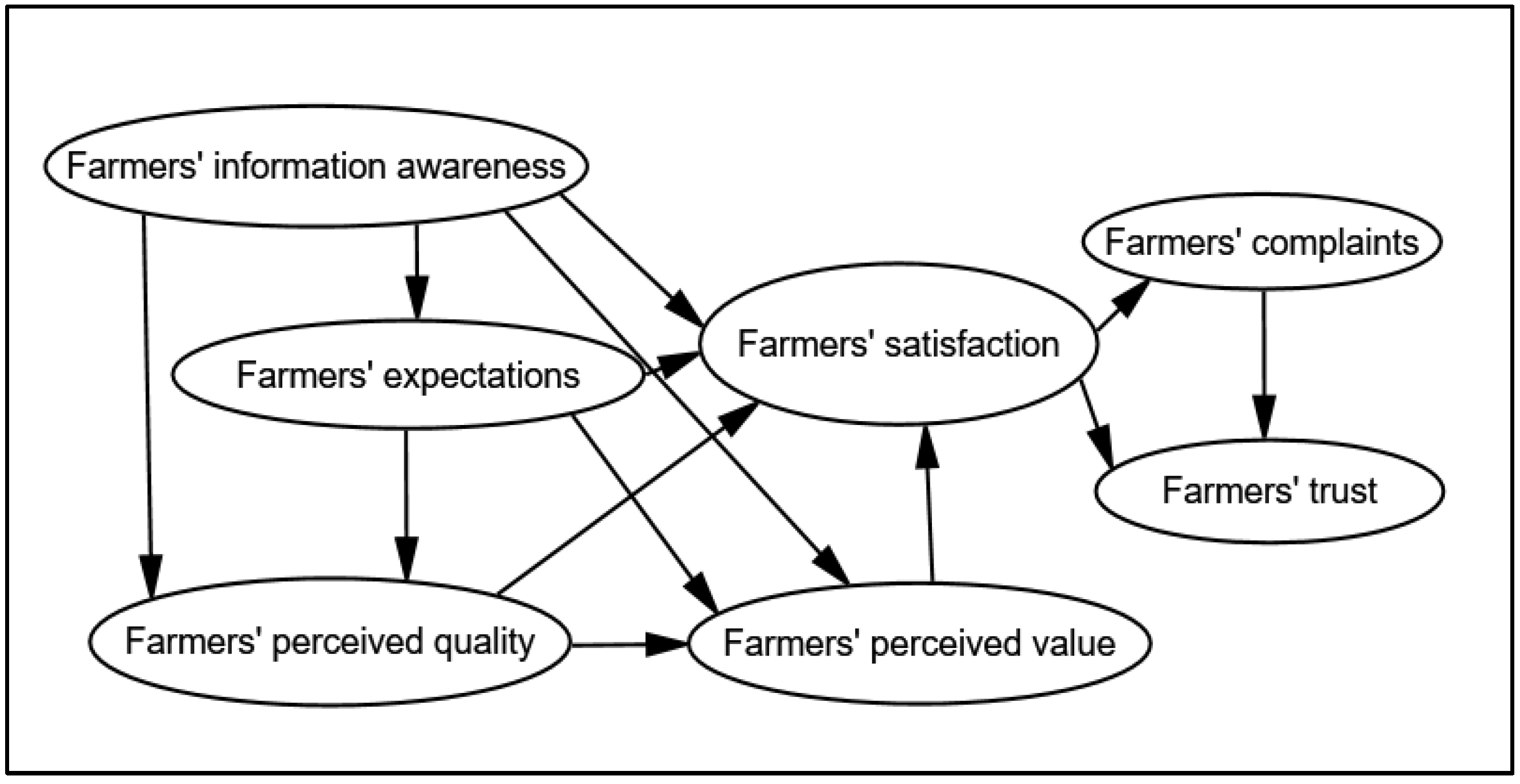

2. Theoretical Model and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Theoretical Model

2.2. Model Construction and Research Hypotheses

- (1)

- Farmers’ information awareness

- (2)

- Farmers’ expectations

- (3)

- Farmers’ perceived quality

- (4)

- Farmers’ perceived value

- (5)

- Farmers’ complaints and farmers’ trust

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Route

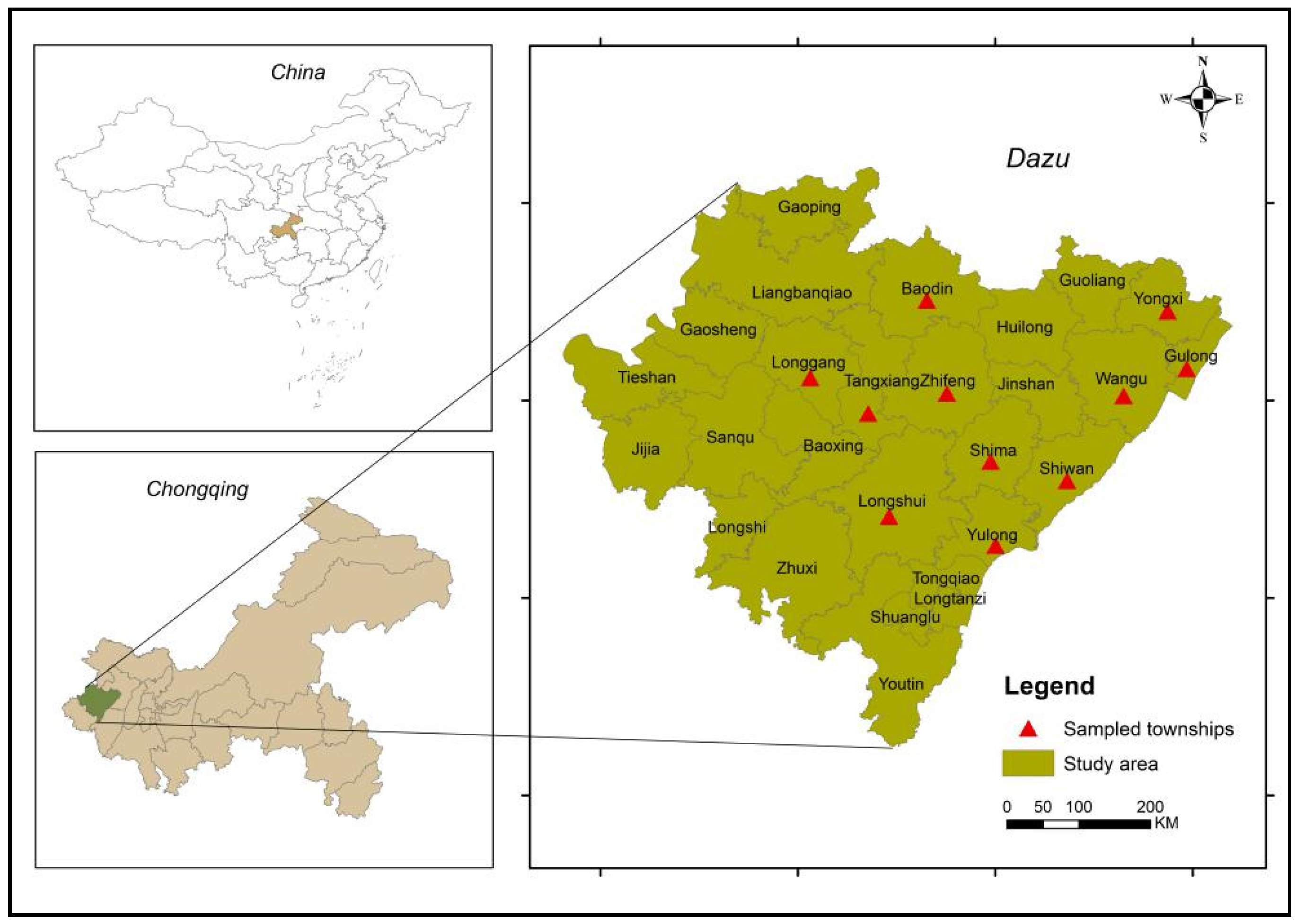

3.2. Study Area

3.3. Data Collection and Sampling

4. Research Results and Analysis

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Analysis of the Reliability and Validity of the Data

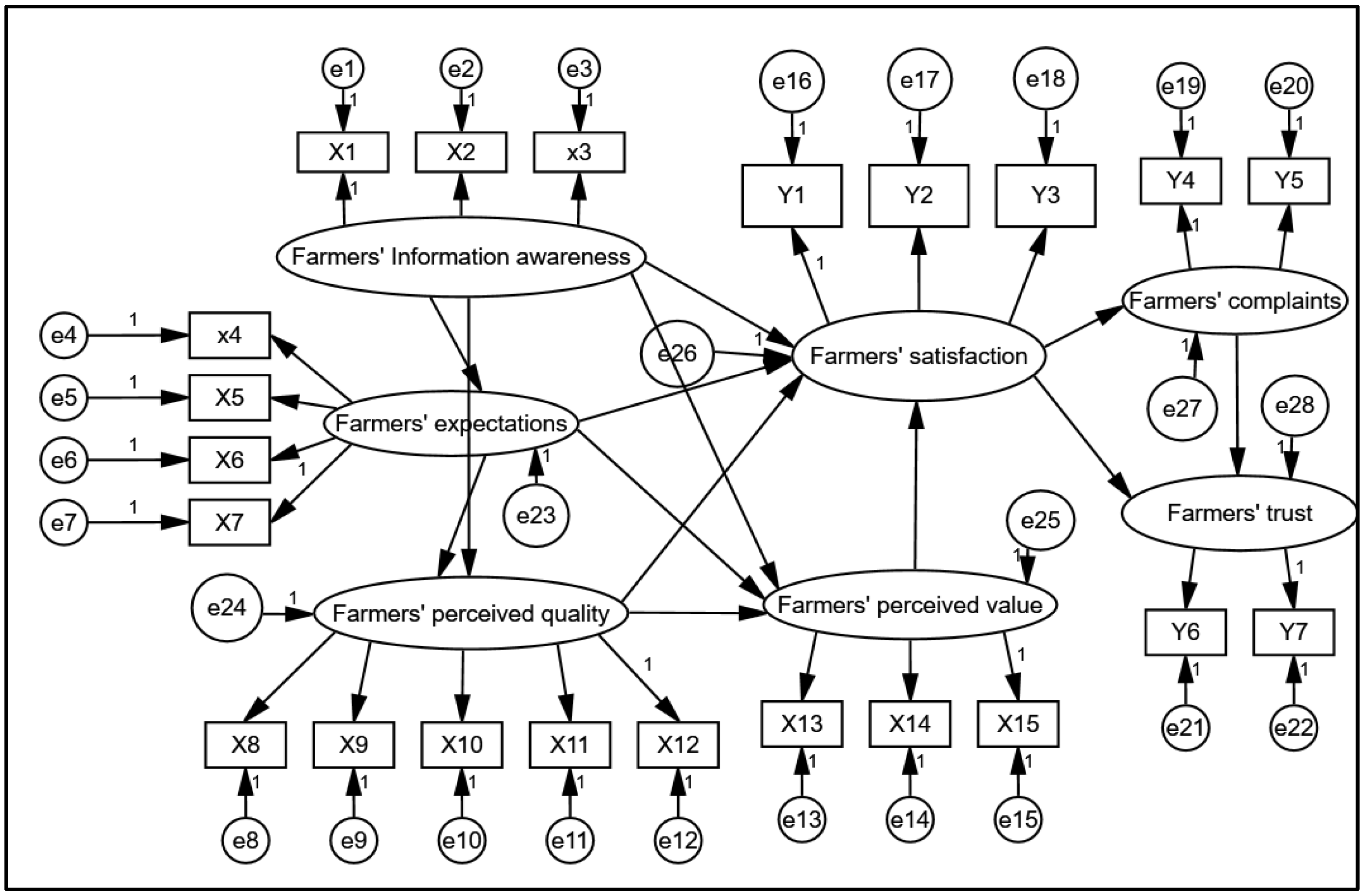

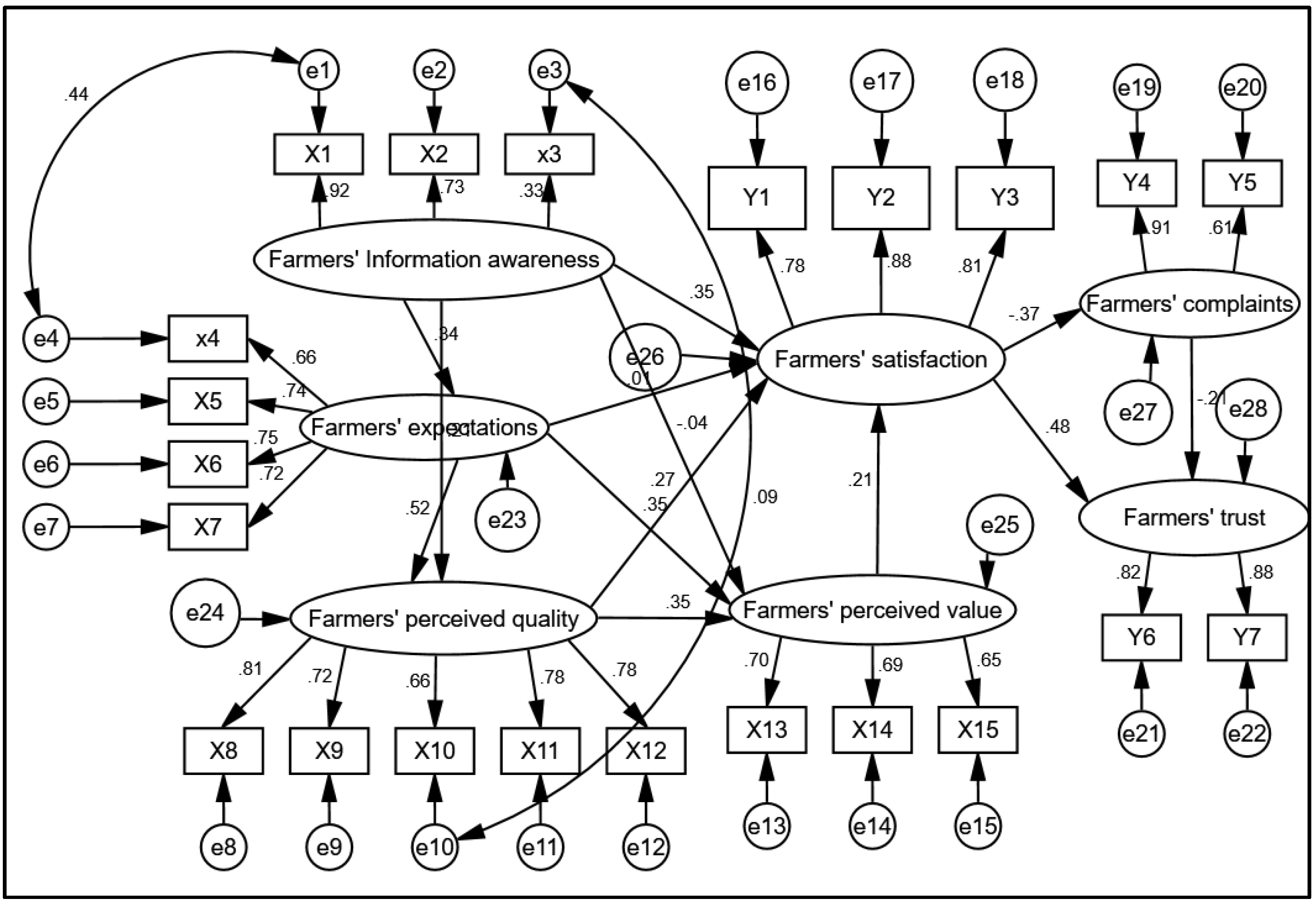

4.3. Research Based on the Structural Equation Model

4.3.1. Evaluation of the Overall Suitability of the Structured Equation Model

4.3.2. Analysis of the Empirical Results of Testing the Research Hypothesis

- (1)

- Farmers’ information awareness and farmers’ satisfaction

- (2)

- Farmers’ perceived quality and farmers’ satisfaction

- (3)

- Farmers’ perceived value and farmers’ satisfaction

- (4)

- Farmers’ satisfaction, farmers’ complaints, and farmers’ trust.

5. Discussion and Recommendation

5.1. Farmers’ Satisfaction Situation

5.2. Policy Improvement Recommendations

5.3. Research Limitations and Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoggart, K.; Paniagua, A. What Rural Restructuring? J. Rural Stud. 2001, 1, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, K.; Yang, D. Will Rural Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketization Impact Local Governments’ Interest Distribution? Evidence from Mainland China. Land 2021, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. Analysis on the Maintenance of Farmers’ Principal Position in the Implementation of Rural Revitalization Strategy in the New Era. J. Hubei Univ. 2019, 6, 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Yang, Y. Research on the Causes and Solution of Land Inefficient Utilization. Sci. Technol. Ind. 2014, 11, 122–126, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Batterbury, S.; Ndi, F. Land Grabbing in Africa. In Handbook of African Development; Binns, J.A., Lynch, K., Nel, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 573–582. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberger, L.; Hall, D.; Vandergeest, P. What happened when the land grab came to Southeast Asia? J. Peasant. Stud. 2017, 4, 697–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pittock, J.; Daniell, K.A. China: A New Trajectory Prioritizing Rural Rather Than Urban Development? Land 2021, 10, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, R.N. An Experimental Study of Customer Effort, Expectation, and Satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 3, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q. The Construction and Evaluation on Satisfaction Index Model for Public Employment Service about the Employees Rate—Based on the Result of Questionnaires about City H. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P. Study of Customer Satisfaction of Food Takeaway in O2O Mode. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y. Satisfaction Evaluation and Influencing Factors of Rural Residents’ Participation in Rural Tourism Projects—A Case Study of Shenyang Rice Dream Space Scenic Spot. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Sun, D.; Yan, J. Farmers’ Participation, Procedural Justice and Satisfaction Degree of Land Acquisition: An Empirical Study Based on the “Thousand Students, Hundred Villages” Survey in 2019. China Land Sci. 2021, 3, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.; Yang, J.; Chen, W. Research of Life Satisfaction Measurement and Influencing Factors of Landless Peasants: A Case Study of Xianlin Village in Nanjing. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2018, 7, 1625–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Lu, T.; Yan, S. Study on the Procedural Rights Guarantee and Farmers’ Satisfaction in the Process of Land Acquisition: Based on the Investigation of 30 Villages,6 Cities in Liaoning Province. China Land Sci. 2016, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C. The Influence of Farmland Confirmation Policy on Farmers’ Subjective Well-being—Empirical Analysis Based on CLDS Data. World Surv. Res. 2019, 9, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. An Analysis of Farmers’ Income Increase Effect through Targeted Poverty Alleviation Policies. J. Lanzhou Univ. 2018, 5, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Huang, B. Satisfaction Assessment and Impact Factors Research on China Agricultural Support Policies: Based on the Field Investigation and Sampling Survey. J. Xiangtan Univ. 2017, 1, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R. A Study on the Factors Affecting Farmers’ Satisfaction in New Rural Cooperative Medical System and Its Optimization: A Case Analysis of L City. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2019, 1, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Chang, X. Empirical analysis of leisure agriculture tourists’ satisfaction—Based on survey data in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2014, 4, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, S. Farmer’s satisfaction with compensation policy for avian influenza: A structural equation modelling study in Zhongwei city, Ningxia. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. 2017, 1, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C. Exploration and Evaluation of Collective Operating Construction Land System: An Analysis Based on the First Batch of Pilot Projects. Chin. Rural Econ. 2021, 11, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Legal approach and rule design for the transfer of collective commercial construction land into the market. Dongyue Trib. 2019, 10, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Feng, Y.; Yu, S. On Optimization of Land Income Distribution in Transaction of Rural Commercial Collective-owned Construction Land: A Case Study of the Reform Pilot in Beiliu City. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2021, 2, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, Z. Research on the income distribution mechanism of collective-owned commercial construction land entering the market based on the balance of interests. Rural Econ. 2019, 10, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhou, R. On the Mechanism for Advancing Rural Collectively-Owned Construction Land and State-owned Land Equally into the Market—A Case Study in Liuyang City of Hunan Province. Huxiang Forum 2018, 2, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, Q. Research on the problems and countermeasures of collective-owned commercial commercial construction land entering the market—Taking Chengdu as an example of the national comprehensive urban and rural comprehensive reform pilot area. Rural Econ. 2020, 3, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog, K.G. Analysis of Covariance Structures; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, D.E. The Identification Problem for Structural Equation Models with Unmeasured Variables. Struct. Equ. Models Soc. Sci. 1973, 3, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W. Sustainable Strengthening Strategy for PC Bridges Based on Theory of Planned Behavior and Multi-Attribute Utility. Doctoral Dissertation, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Gan, C.; Ren, L.; Chen, Y. Analysis on influencing factors of farming households’ willingness to land conversion under the distributed cognition theory:an empirical evaluation of Wuhan Urban Circle by SEM. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 9, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Cui, X.; Ji, S. Evaluating Migrant Workers’ Satisfaction of Public Services with a Structural Equation Model. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 2017, 5, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, B.E. American Customer Satisfaction Index: Methodology Report; National Quality Research Center; University of Michigan Business School: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1995; Volume 48, pp. 109–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Fang, Z. An Analysis of Common Research Models of Customer Satisfaction and their Strengths and Weaknesses. J. Guizhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2002, 6, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Jiang, L. Social Status, Opinion of Government Role and Satisfaction on Public Services—SEM Analysis Based on CGSS2013 Survey. Soft Sci. 2017, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American Customer Satisfaction Index: Nature, Purpose, and Findings. J. Mark. 1996, 4, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Research on the Interest Pattern of Collective Management Construction Land Marketization under the Guidance of the Government—Taking Daxing District of Beijing as An Example. Master’s Thesis, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 2, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Q. Study on Land Acquisition Satisfaction of Landless Farmers—Taking Quanzhou City as An Example. Master’s Dissertation, Huaqiao University, Quanzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, T.; Lægreid, P. Trust in Government: The Relative Importance of Service Satisfaction, Political Factors and Demography. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2005, 4, 487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Huang, B. Analysis on the Reliability and Validity of Questionnaire. Stat. Inf. Trib. 2005, 6, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Deng, W. Factors of Service Quality for Urban Rail Transit Based on Structural Equation Modeling. J. Transp. Eng. Inf. 2019, 2, 58–64, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Structural Equation Modeling—Operation and Application of AMOS; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; 10694(000). [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 3, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ma, B.; Zhao, L. The Impact of Different Forms of Customer Participation on Enterprise Green Service Innovation. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2022, 7, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, N. The Influencing Outcomes of Job Engagement: An Interpretation from the Social Exchange Theory. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 5, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, L. Consumer Community Cognition, Brand Loyalty, and Behaviour Intentions within Online Publishing Communities: An Empirical Study of Epubit in China. Learn. Publ. 2021, 2, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J. Practice and Reflections on Market Entry of Collective Management Land for Construction in the Context of Rural Revitalization—Taking Dazu District of Chongqing City as an Example. Rural Econ. Sci.-Technol. 2022, 11, 13–15, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Han, Y.; Guo, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, W. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Farmer’s Willingness to Adopt Soil Testing and Formula Fertilization Technology Based on SEM. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2019, 9, 2119–2129. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X. The Perfection of the System of Land Related Tax Under The Background of Collective Operational Construction Land Entering the Land Market. Wuhan Univ. J. 2020, 4, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, Y. Policy Logic and Legal Response of Collective Construction Land Entering the Scope of Urban Construction Land. Stud. Law Bus. 2021, 4, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X. On the Legitimacy of the Ownership Division in the Reform of Collectively Owned Buildable Land Entering the Market. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. 2021, 2, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, D.; Lv, X.; Wang, B. The Role of Government in Rural Construction Land Marketization: Based on the Content Analysis of Contracts. China Land Sci. 2019, 4, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, A.; Yang, S. The Marketilization of Commercial Collective Construction Land and the Game between Local Government and Village Collectives. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2015, 1, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, B.; Liang, L. Farmers’ cognition and willingness to the marketization of the rural collective operating construction land in Henan Province. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2017, 10, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Peng Q Study on the Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Behavioral Intention in Urban Afforestation Project: Taking Beijing Plain Afforestation Project as an Example. Issues For. Econ. 2019, 2, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

| Potential Variables | Observed Variables | Variable Values | Kurtosis | Skewness | Means | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ information awareness | Dissemination of information on policies related to land marketisation (X1) | 1 = “very poor”, 2 = “poor”, 3 = “average”, 4 = “fairly good”, 5 = “very good” | 0.346 | −0.550 | 2.88 | 0.996 |

| Transparency of information disclosure (X2) | 1 = “very opaque”, 2 = “not very transparent”, 3 = “average”, 4 = “fairly transparent”, 5 = “very transparent” | 0.054 | −0.961 | 3.13 | 1.158 | |

| Participation in voting in the land marketisation (X3) | Yes, No | 0.126 | −2.007 | 0.47 | 0.500 | |

| Farmers’ expectations | Expectations of living standards after land marketisation (X4) | 1 = “significantly lower”, 2 = “somewhat lower”, 3 = “the same as before”, 4 = “somewhat improved”, 5 = “significantly improved” | −0.124 | 0.553 | 3.13 | 0.826 |

| Expectations of the amount of compensation to be obtained after land marketisation (X5) | 1 = “very low”, 2 = “relatively low”, 3 = “average”, 4 = “relatively high”, 5 = “very high” | 0.193 | −0.069 | 2.93 | 0.751 | |

| Expectations of employment help after land marketisation (X6) | 1 = “very dissatisfied”, 2 = “not very satisfied”, 3 = “average”, 4 = “Somewhat satisfied”, 5 = “Very satisfied” | −0.492 | 0.554 | 2.98 | 0.695 | |

| Expectations of medical insurance and social insurance subsidy after entry market (X7) | 1 = “very dissatisfied”, 2 = “not very satisfied”, 3 = “average”, 4 = “more satisfied”, 5 = “very satisfied” | −0.239 | 0.495 | 2.84 | 0.770 | |

| Farmers’ perceived quality | Satisfaction with the amount of benefits distributed after market entry (X8) | 1 = “very dissatisfied”, 2 = “not very satisfied”, 3 = “average”, 4 = “more satisfied”, 5 = “very satisfied” | 0.379 | −0.103 | 3.02 | 0.746 |

| Fairness of distribution of earnings (X9) | 1 = “not fair”, 2 = “not very fair”, 3 = “fair”, 4 = “fairer”, 5 = “very fair” | 0.161 | −0.288 | 3.23 | 0.829 | |

| Procedural fairness and legality of land marketisation (X10) | 1 = “not fair”, 2 = “not very fair”, 3 = “fair”, 4 = “quite fair “, 5 = “very fair” | 0.431 | −0.347 | 3.12 | 0.937 | |

| Increase in access to employment after land marketisation (X11) | 1 = “none at all”, 2 = “not much”, 3 = “fair”, 4 = “some increase”, 5 = “considerable increase” | −0.255 | −0.125 | 2.89 | 0.843 | |

| Medical insurance and social insurance subsidy after land marketisation (X12) | 1 = “very dissatisfied”, 2 = “not very satisfied”, 3 = “neutral”, 4 = “quite satisfied”, 5 = “very satisfied” | 0.159 | 0.115 | 2.98 | 0.815 | |

| Farmers’ perceived value | Change in living standards (X13) | 1 = “much worse”, 2 = “somewhat worse”, 3 = “no change”, 4 = “somewhat better”, 5 = “much better” | 0.480 | 0.913 | 3.27 | 0.701 |

| Change in income level (X14) | 1 = “much worse”, 2 = “somewhat worse”, 3 = “no change”, 4 = “somewhat better”, 5 = “much better” | −0.176 | 1.674 | 3.05 | 0.525 | |

| Change in living environment (X15) | 1 = “much worse”, 2 = “somewhat worse “, 3 = “no change”, 4 = “somewhat better”, 5 = “much better” | −0.353 | 1.212 | 2.99 | 0.657 | |

| Farmers’ satisfaction | Satisfaction compared with expectations (Y1) | 1 = “very dissatisfied”, 2 = “not very satisfied”, 3 = “average”, 4 = “quite satisfied”, 5 = “very satisfied” | 0.173 | −0.297 | 3.04 | 0.985 |

| Satisfaction compared with ideal satisfaction (Y2) | 1 = “very dissatisfied”, 2 = “not very satisfied”, 3 = “neutral”, 4 = “quite satisfied”, 5 = “very satisfied” | 0.120 | −0.832 | 3.14 | 1.059 | |

| Overall satisfaction (Y3) | 1 = “very dissatisfied”, 2 = “not very satisfied”, 3 = “neutral”, 4 = “quite satisfied”, 5 = “very satisfied” | 0.080 | −0.848 | 3.27 | 1.099 | |

| Farmers’ complaints | Likelihood of negative publicity about land marketisation (Y4) | 1 = “not likely”, 2 = “probably unlikely”, 3 = “uncertain”, 4 = “probably likely”, 5 = “very likely” | 0.392 | −0.341 | 2.47 | 1.006 |

| Entry policy deficiencies (Y5) | 1 = “no deficiencies”, 2 = “not too serious”, 3 = “uncertain”, 4 = “quite serious”, 5 = “very serious” | 0.315 | −0.781 | 2.63 | 1.085 | |

| Farmers’ trust | Confidence that future land marketisation will go smoothly (Y5) | 1 = “no confidence”, 2 = “hardly any confidence “, 3 = “uncertain”, 4 = “some confidence”, 5 = “complete confidence” | −0.173 | −1.108 | 3.54 | 1.103 |

| Level of support for government policy on land marketisation (Y6) | 1 = “none”, 2 = “hardly any”, 3 = “uncertain”, 4 = “quite high “, 5 = “high” | −0.041 | −1.075 | 3.39 | 1.098 |

| Category | Breakdown | Sample Statistics | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 80 | 45.2% |

| Female | 97 | 54.8% | |

| Age | Under 25 years of age | 2 | 1.1% |

| Age 26–40 | 14 | 7.9% | |

| Age 40–60 | 63 | 35.6% | |

| Over 60 years old | 98 | 55.4% | |

| Educational attainment | No education | 67 | 37.9% |

| Primary school | 63 | 35.6% | |

| Lower secondary | 31 | 17.5% | |

| High school/junior college | 9 | 5.1% | |

| College/Bachelor’s degree and above | 7 | 4.0% | |

| Are you a village official? | Yes | 36 | 20.3% |

| No | 141 | 79.7% | |

| Main source of income | Working in agriculture | 78 | 44.1% |

| Main source of income combining farming with other non-agricultural work | 58 | 32.8% | |

| Non-agricultural farming | 41 | 23.2% | |

| Annual household income | Less than 10,000 RMB | 59 | 33.3% |

| 10–40,000 RMB | 77 | 43.5% | |

| 40,000–70,000 RMB | 30 | 16.9% | |

| 70,000–100,000 RMB | 8 | 4.5% | |

| Over RMB 100,000 | 3 | 1.7% |

| Item | Number of Items | α Confidence Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ information awareness | 2 | 0.807 |

| Farmers’ expectations | 4 | 0.807 |

| Farmers’ perceived quality | 5 | 0.864 |

| Farmers’ perceived value | 3 | 0.716 |

| Farmers’ satisfaction | 3 | 0.863 |

| Farmers’ trust | 2 | 0.714 |

| Farmers’ complaints | 2 | 0.838 |

| KMO Sampling Adequacy Measure | 0.826 | |

|---|---|---|

| Approximate chi-square (χ2) | 1784.053 | |

| Bartlett’ssphericity test | Bartlett’s sphericity test Degrees of freedom (df) | 231 |

| Significance P | 0.000 |

| Score | Initial Eigenvalue | Extraction of Load Sums of Squares | Sum of Squared Rotating Loads | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Percentage Variance | Cumulative % | Total | Percen-Tage Variance | Cumula-Tive % | Total | Percentage Variance | Cumu-Lative % | |

| 1 | 7.027 | 31.942 | 31.942 | 7.027 | 31.942 | 31.942 | 3.371 | 15.324 | 15.324 |

| 2 | 2.008 | 9.128 | 41.070 | 2.008 | 9.128 | 41.070 | 2.602 | 11.828 | 27.153 |

| 3 | 1.807 | 8.213 | 49.283 | 1.807 | 8.213 | 49.283 | 2.457 | 11.167 | 38.320 |

| 4 | 1.507 | 6.852 | 56.135 | 1.507 | 6.852 | 56.135 | 1.987 | 9.033 | 47.353 |

| 5 | 1.287 | 5.849 | 61.984 | 1.287 | 5.849 | 61.984 | 1.917 | 8.715 | 56.068 |

| 6 | 1.210 | 5.501 | 67.485 | 1.210 | 5.501 | 67.485 | 1.766 | 8.026 | 64.094 |

| 7 | 0.900 | 4.092 | 71.577 | 0.900 | 4.092 | 71.577 | 1.646 | 7.482 | 71.577 |

| Potential Variables | Observed Variables | Factor Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ information awareness | X1 | 0.906 | 0.728 | 0.501 |

| X2 | 0.749 | |||

| X3 | 0.348 | |||

| Farmers’ expectations | X4 | 0.728 | 0.812 | 0.520 |

| X5 | 0.759 | |||

| X6 | 0.725 | |||

| X7 | 0.670 | |||

| Farmers’ perceived quality | X8 | 0.783 | 0.868 | 0.570 |

| X9 | 0.670 | |||

| X10 | 0.721 | |||

| X11 | 0.672 | |||

| X12 | 0.684 | |||

| Farmers’ perceived value | X13 | 0.692 | 0.724 | 0.466 |

| X14 | 0.879 | |||

| X15 | 0.633 | |||

| Farmers’ satisfaction | Y1 | 0.865 | 0.734 | 0.587 |

| Y2 | 0.833 | |||

| Y3 | 0.779 | |||

| Farmers’ complaints | Y4 | 0.878 | 0.838 | 0.721 |

| Y5 | 0.814 | |||

| Farmers’ trust | Y6 | 0.781 | 0.864 | 0.680 |

| Y7 | 0.812 |

| Evaluation Indicators | X2/df | RMSEA | NFI | CFI | IFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference standards | <3 | <0.08 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 |

| Before amendment | 1.754 | 0.065 | 0.806 | 0.904 | 0.906 | 0.886 |

| Indicator values for this model | 1.548 | 0.056 | 0.939 | 0.935 | 0.936 | 0.923 |

| Model adaptation judgement | Ideal | Ideal | Approach | Ideal | Ideal | Ideal |

| Assumptions | Estimate | CR | p | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Farmers’ information awareness positively influences farmers’ expectations. | 0.344 | 3.664 | *** | Supported |

| H1b: Farmers’ information awareness has a positive impact on farmers’ perceived value. | −0.035 | −0.381 | 0.703 | Not supported |

| H1c: Household information awareness has a positive impact on farm household perceived quality. | 0.209 | 2.523 | * | Supported |

| H1d: Farmers’ information awareness positively influences farmers’ satisfaction. | 0.345 | 3.836 | *** | Supported |

| H2a: Farmers’ expectations positively influence perceived quality. | 0.519 | 5.401 | *** | Supported |

| H2b: Farmers expect a positive impact on perceived value. | 0.348 | 2.83 | * | Supported |

| H2c: Farmers’ expectations positively influence farmers’ satisfaction. | 0.013 | 0.119 | 0.906 | Not supported |

| H3a: Farmers’ perceived quality positively influences farmers’ perceived value. | 0.352 | 2.893 | * | Support |

| H3b: Farmers’ perceived quality positively influences farmers’ satisfaction. | 0.271 | 2.493 | * | Supported |

| H4a: Farmers’ perceived value positively influences farmers’ satisfaction. | 0.205 | 1.847 | * | Supported |

| H5a: Farmers’ satisfaction has a negative impact on farmers’ complaints. | −0.365 | −4.206 | *** | Supported |

| H5b: Farmers’ satisfaction positively influences farmers’ trust. | 0.477 | 5.233 | *** | Supported |

| H5c: Farmers’ complaints have a negative impact on farmers’ trust. | −0.213 | −2.154 | * | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Wang, H. What Is Farmers’ Level of Satisfaction under China’s Policy of Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketisation? Land 2022, 11, 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081335

Liu J, Wang H. What Is Farmers’ Level of Satisfaction under China’s Policy of Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketisation? Land. 2022; 11(8):1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081335

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiali, and Hengwei Wang. 2022. "What Is Farmers’ Level of Satisfaction under China’s Policy of Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketisation?" Land 11, no. 8: 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081335

APA StyleLiu, J., & Wang, H. (2022). What Is Farmers’ Level of Satisfaction under China’s Policy of Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketisation? Land, 11(8), 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081335