Exploring the Determinants of Residents’ Behavior towards Participating in the Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal of China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

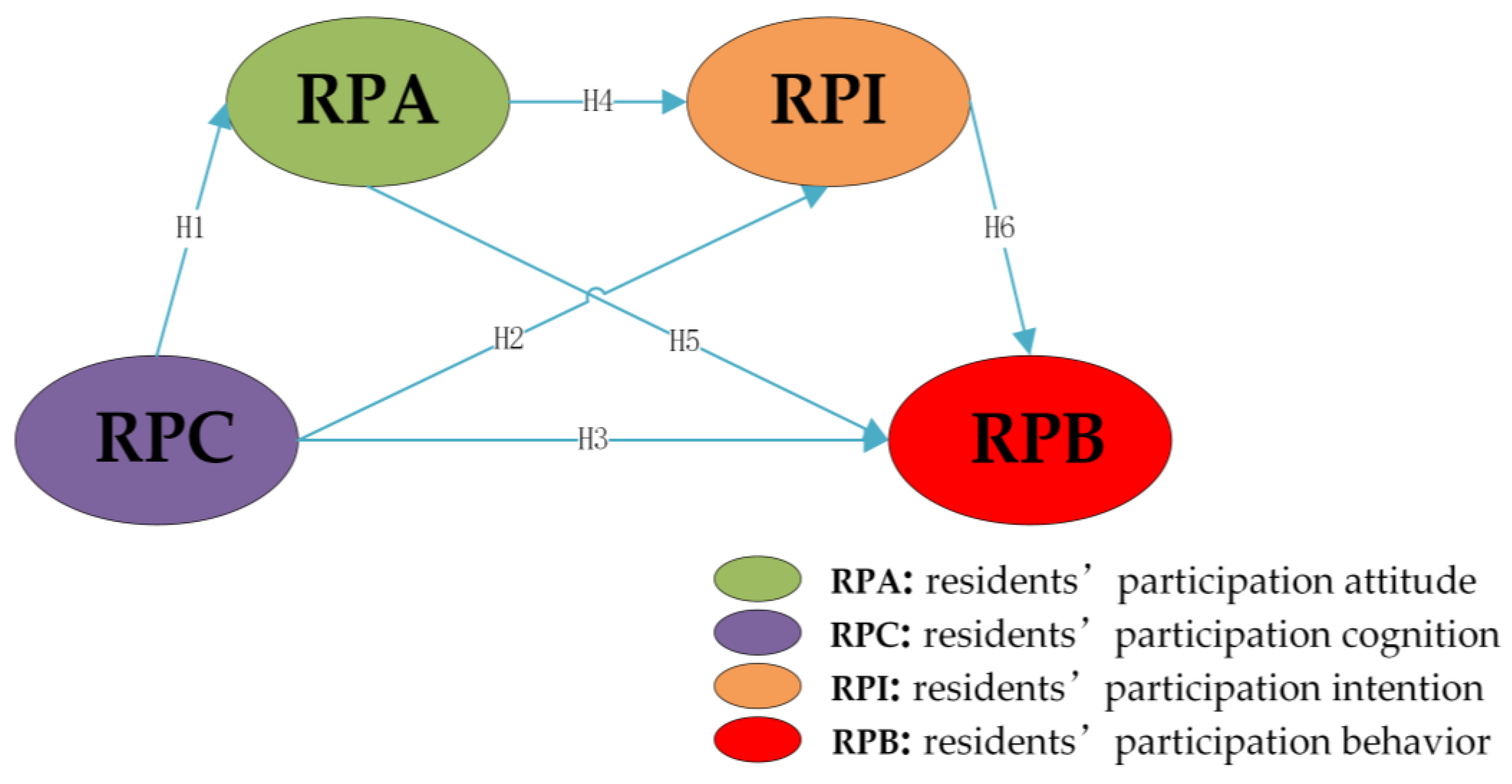

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

2.2. Hypotheses Based on the Extended TPB

- (1)

- Residents’ participation cognition (RPC)

- (2)

- Residents’ participation attitude (RPA)

- (3)

- Residents’ participation intention (RPI)

3. Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

- (a)

- A succinct explanation of the SOCR and the purpose of this investigation;

- (b)

- Respondents’ demographic and socioeconomic information, including gender, age, education, length of residence, living status, employment, tenant, and income;

- (c)

- The determinants of respondents’ participation behavior, including the RPC (‘understanding techniques used in the SOCR’—RPC1, ‘knowing benefits of the SOCR’—RPC2, ‘providing channels for participation’—RPC3, ‘knowing ways of participation’—RPC4, ‘understanding the importance of participation’—RPC5, ‘mastering related knowledge’—RPC6, ‘believing others will do’—RPC7, ‘believing others hope we will do’—RPC8; 8 questions measured with a 5-point scale), the RPA (‘supporting the SOCR’—RPA1, ‘concerning about the progress’—RPA2, ‘knowing the importance of the SOCR’—RPA3, ‘suggesting to increase channels’—RPA4; 4 questions measured with a 5-point scale), and the RPI (‘willing to participate in decision-making’—RPI1, ‘willing to promote the SOCR’—RPI2, ‘willing to pay extra fees’—RPI3, ‘willing to devote more time and effort’—RPI4; 4 questions measured with a 5-point scale) in the SOCR. Answers were given on 5-point scales from 1 = low to 5 = high.

- (d)

- Respondents’ participation behavior, including respondents’ participation behavior in the decision-making phase, construction phase, and maintenance phase of the SOCR projects (the three items were chosen according to the research of Gu et al. [18], and three questions measured with a 5-point scale were adopted in the questionnaire).

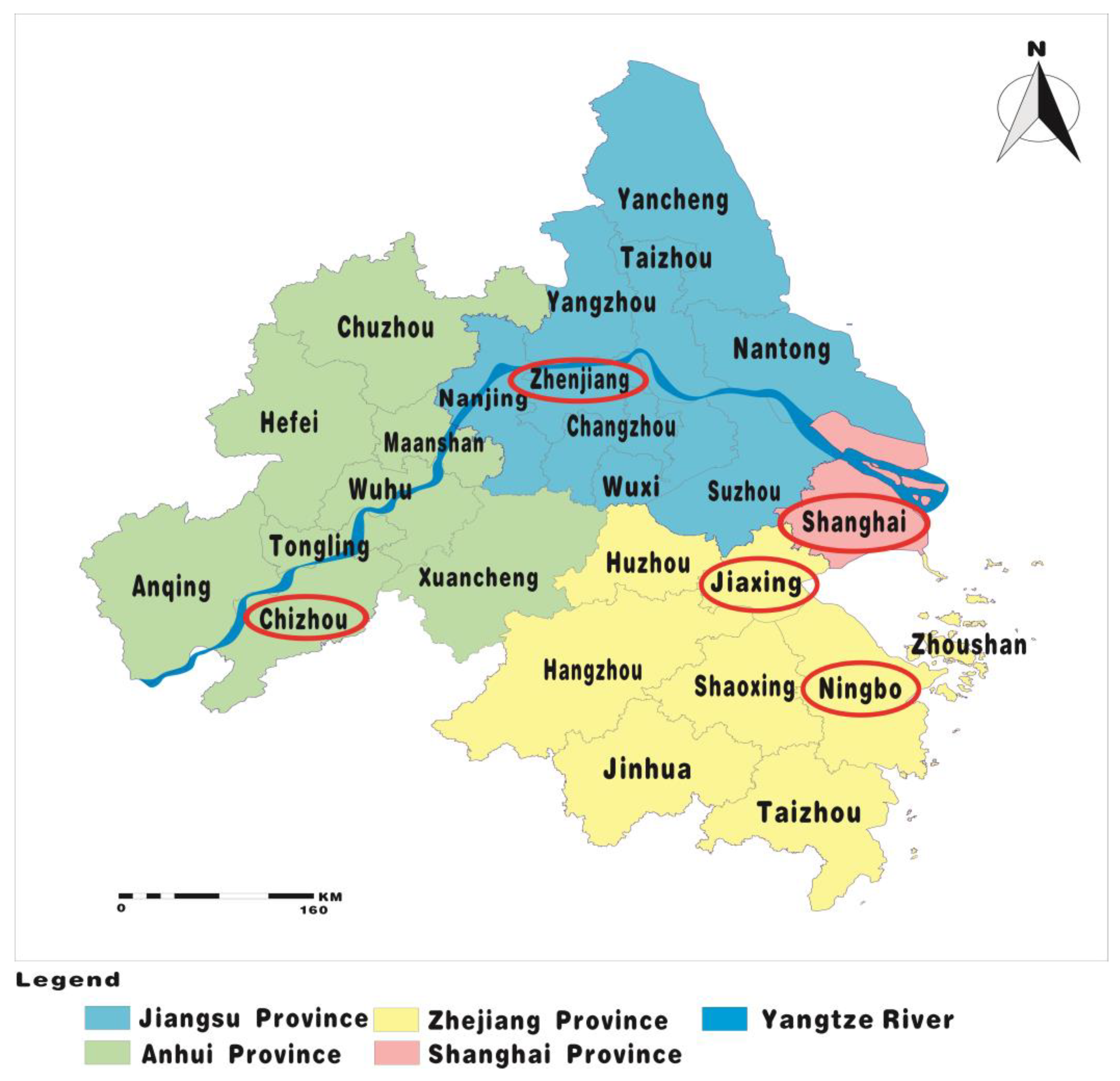

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

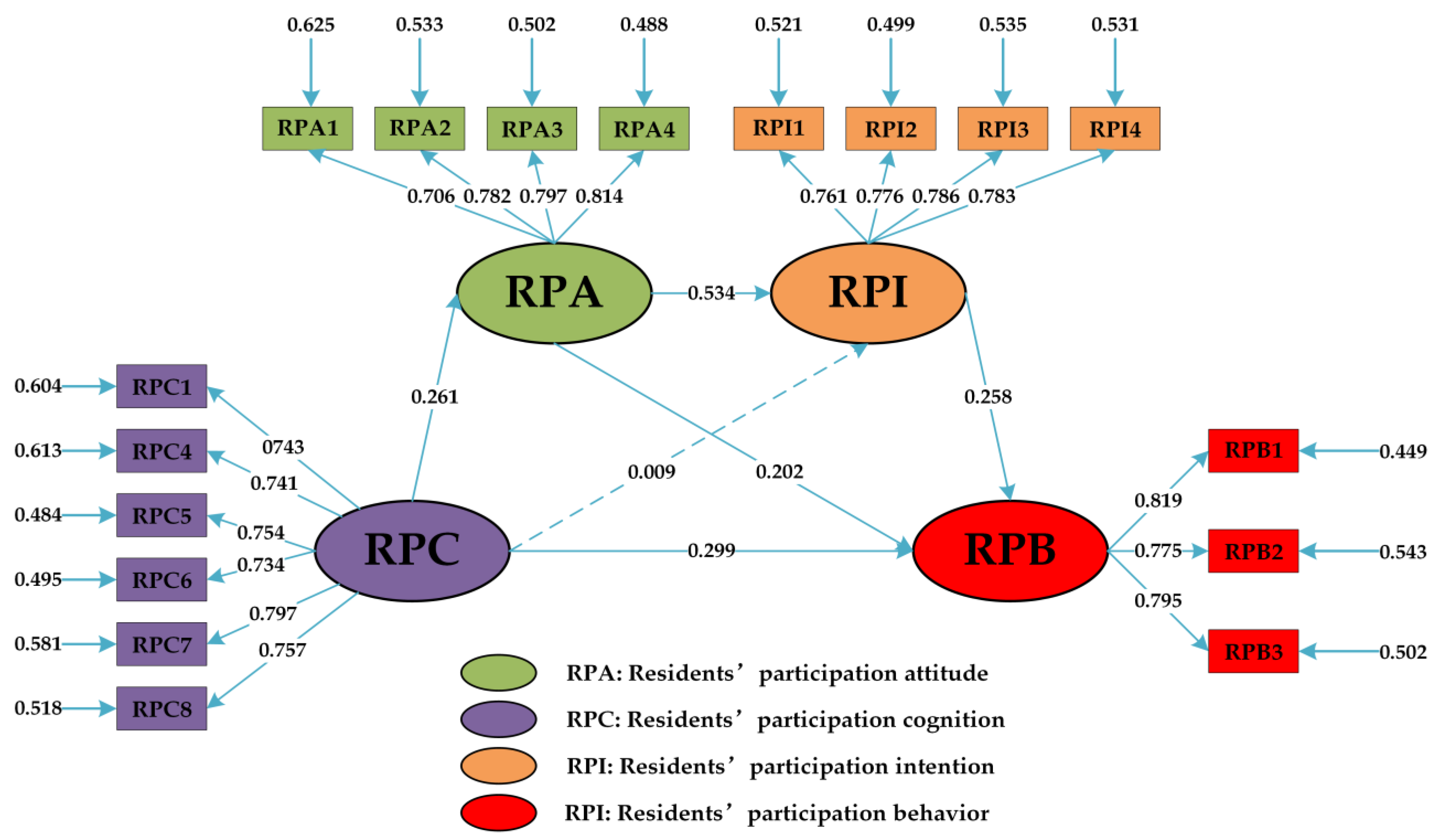

4. Results

4.1. Reliability Testing

4.2. Validity Testing

4.3. Mean Value of Latent Variables and Ranking of Related Observed Indicators

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of the Observed Variables

5.2. Direct Paths for Affecting the RPB

5.3. Indirect Paths for Affecting the RPB

5.4. Limitations

6. Practical Implications

- (1)

- Strengthening the residents’ participation cognition in the SOCR projects. First, regular publicity of the SOCR can enable residents to fully understand the practical changes brought about by such projects so as to gradually improve their participation cognition. In the publicity process of the SOCR project, community management departments, neighborhood committees, and community service centers are encouraged to provide more education and training opportunities for residents so that they can thoroughly understand the construction of their sponge city and regard their participation in renewal activities as their obligations. Second, considering the characteristics of later maintenance of sponge facilities, the residents could be provided with the necessary facilities maintenance guidance to improve their ability to participate in these projects as well as enhance their cognition of participating in public affairs. Finally, communication platforms in old communities could build a bridge between community residents and the public sector [55]. Therefore, it is suggested to establish a feasible communication platform and host regular community dialogue meetings, such as community forums and community roundtables. Through continuous communication between all stakeholders in the community, it would be possible for residents to keep an in-depth understanding of the SOCR projects. In this case, their cognition of participation could be improved.

- (2)

- Enhancing the residents’ participation attitude towards the SOCR projects. First, defining the obligations and responsibilities of all participants in the life cycle of the SOCR project, especially emphasizing the participation obligations of residents, could help residents understand that it is their duty to participate in the SOCR so as to fundamentally improve their participation attitude. Second, residents could be cultivated with a sense of community belonging so that they can emotionally endorse the SOCR and consciously participate in the renewal projects. It is proposed that the community environment could be improved by increasing investment in infrastructure to meet the diverse needs of residents and increase the level of residents’ satisfaction with the community. Moreover, community committees can provide opportunities to enhance mutual understanding and trust by organizing regular community activities. Finally, learning from the multi-party cooperation system established in the rainwater management project of Australia [57], residents should be given more rights to engage in the SOCR cooperation system composed of government, local enterprise, community organizations, and residents.

- (3)

- Improving the residents’ willingness to participate in the SOCR projects. On the one hand, material incentives are the most direct way to activate enthusiasm for residents’ participation. It is suggested to propose targeted incentive measures to meet the specific needs of residents for the SOCR project, such as, for example, providing more activity spaces and parking spaces to address residents’ demand for community space. Furthermore, by learning from the experience of rainwater utilization in Kronsberg of Germany, the rainwater collected by sponge facilities could be used for free for residents to wash their cars or water plants. Ulteriorly, subsidies are suggested to be provided for residents who participate in the opinion exchange meetings on the SOCR in the long term. On the other hand, channels that facilitate residents’ participation could be provided by the government. The ‘unintentional participation’ of residents in the SOCR project is usually caused by the fact that residents do not know the channels of participation. In the rainstorm management project of the United States, the government uses e-mail as a common way of communication, while Australia uses telephone consultation [58,59]. Learning from this case, it is suggested that more convenient online communication methods could be developed, such as online complaint portals, online discussion boards, and online forums.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Indicators | Items | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPC | Understanding techniques used in the SOCR (RPC1) | I understand the low-impact development technology commonly used in the SOCR. | [33,60,61,62,63] |

| Knowing the benefits of the SOCR (RPC2) | I think the SOCR brings many benefits, such as improving the quality of life. | ||

| Providing channels for participation (RPC3) | Community or government departments will provide relevant channels for me to participate in the SOCR. | ||

| Knowing ways of participation (RPC4) | I know how to participate in governance in the SOCR. | ||

| Understanding the importance of participation (RPC5) | My participation is essential for the SOCR, such as reducing conflict in the implementation of projects. | ||

| Mastering related knowledge (RPC6) | If I participate in the decision-making, implementation, and maintenance of the SOCR, I can master related knowledge. | ||

| Believing others will do (RPC7) | Family, friends, and neighbors who are important to me will participate in the SOCR. | ||

| Believing others hope we will do (RPC8) | Family, friends, and neighbors who are important to me hope I can participate in the SOCR. | ||

| RPA | Supporting the SOCR (RPA1) | I support the SOCR in the community. | [33,64,65] |

| Concern regarding the progress (RPA2) | I am concerned about the progress of the SOCR in our community. | ||

| Knowing the importance of the SOCR (RPA3) | I think it is of great significance to implement the SOCR. | ||

| Suggesting increasing channels (RPA4) | I think the government should provide channels for the residents to actively participate in the SOCR. | ||

| RPI | Willing to participate in the SOCR (RPI1) | If relevant government departments provide opportunities, I am willing to participate in the whole process of the SOCR, such as participating in the preliminary consultation meeting. | [36,38,61,65] |

| Willing to promote the SOCR (RPI2) | I am willing to publicize the benefits of the SOCR to others and encourage others to participate. | ||

| Willing to pay extra fees (RPI3) | To reduce the problem of waterlogging in the community, I am willing to pay extra fees for the SOCR. | ||

| Willing to devote more time and effort (RPI4) | In order to reduce the problem of waterlogging in the community, I am willing to devote more time and effort to participating in issues related to the SOCR. | ||

| RPB | Participating in the decision-making stage (RPB1) | I participate in the decision-making stage of the SOCR, such as proposing the SOCR plan to related policymakers. | [18,36] |

| Participating in the implementation stage (RPB2) | I participate in the implementation stage of the SOCR, such as collaborating with the construction crew. | ||

| Participating in the maintenance stage (RPB3) | I participate in the maintenance stage of the SOCR, such as regularly cleaning the garbage in the rainwater garden and protecting our rainwater bucket. |

| Variables | Items | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 56.25 |

| Female | 43.75 | |

| Education level | Doctor | 37.50 |

| Master | 46.88 | |

| Others | 15.63 | |

| Working experiences | More than 5 years | 25.00 |

| 3 to 5 years | 28.13 | |

| 1 to 3 years | 37.50 | |

| Less than 1 year | 12.50 | |

| Professional title grade | High professional title | 21.88 |

| Associate professional title | 34.38 | |

| Intermediate professional title | 25.00 | |

| Junior professional title | 12.50 | |

| Others | 6.24 | |

| Profession | College teachers | 37.50 |

| Government staff | 25.00 | |

| Enterprise managers | 28.13 | |

| Others | 9.38 |

| Variables | Indicators | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Standardized Factor Loading | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents’ participation cognition | RPC1 | 0.894 | 0.889 | 0.743 *** | 0.572 |

| RPC2 | 0.597 *** (deleted) | ||||

| RPC3 | 0.588 *** (deleted) | ||||

| RPC4 | 0.741 *** | ||||

| RPC5 | 0.754 *** | ||||

| RPC6 | 0.734 *** | ||||

| RPC7 | 0.797 *** | ||||

| RPC8 | 0.757 *** | ||||

| Residents’ participation attitude | RPA1 | 0.857 | 0.858 | 0.706 *** | 0.602 |

| RPA2 | 0.782 *** | ||||

| RPA3 | 0.797 *** | ||||

| RPA4 | 0.814 *** | ||||

| Residents’ participation intention | RPI1 | 0.858 | 0.859 | 0.761 *** | 0.603 |

| RPI2 | 0.776 *** | ||||

| RPI3 | 0.786 *** | ||||

| RPI4 | 0.783 *** | ||||

| Residents’ participation behavior | RPB1 | 0.839 | 0.839 | 0.819 *** | 0.635 |

| RPB2 | 0.775 *** | ||||

| RPB3 | 0.795 *** |

| Fit Indices | Suggested Value | Measured Value |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | < 3, the model has a reduced fitting degree; , the model needs to be modified [47]. | 2.412 |

| GFI | If >0.90, the data are ideal [47]. | 0.988 |

| AGFI | If >0.90, the data are ideal [47]. | 0.969 |

| RMSEA | If <0.05, the data is ideal; If <0.08, the data are acceptable [47]. | 0.029 |

| NFI | If >0.90, the data is ideal; If >0.80, the data are acceptable [47]. | 0.980 |

| TLI(NNFI) | If >0.90, the data are ideal [36]. | 0.986 |

| CFI | If >0.90, the data are ideal [45]. | 0.988 |

| AVE | RPC | RPA | RPI | RPB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPC | 0.572 | 0.756 | |||

| RPA | 0.602 | 0.263 ** | 0.776 | ||

| RPI | 0.603 | 0.152 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.777 | |

| RPB | 0.635 | 0.369 ** | 0.418 ** | 0.411 ** | 0.797 |

References

- Pradhananga, A.K.; Davenport, M.A. Community Attachment, Beliefs and Residents’ Civic Engagement in Stormwater Management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Big Data to See the 30-Year Evolution of Floods in China. Available online: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/484864623 (accessed on 4 June 2022). (In Chinese).

- Zhou, Q.; Quitzau, M.-B.; Hoffmann, B.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K. Towards Adaptive Urban Water Management: Up-Scaling Local Projects. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Constr. 2013, 2, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lin, M.; Li, C. Analysis of the Effects of the River Network Structure and Urbanization on Waterlogging in High-Density Urban Areas-A Case Study of the Pudong New Area in Shanghai. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dietz, M.E. Low Impact Development Practices: A Review of Current Research and Recommendations for Future Directions. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2007, 186, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, A.M.; Tapper, N.J.; Beringer, J.; Loughnan, M.; Demuzere, M. Watering Our Cities: The Capacity for Water Sensitive Urban Design to Support Urban Cooling and Improve Human Thermal Comfort in the Australian Context. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2013, 37, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q. A Review of Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems Considering the Climate Change and Urbanization Impacts. Water 2014, 6, 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.S.; Lu, X.X. Sustainable Urban Stormwater Management in the Tropics: An Evaluation of Singapore’s ABC Waters Program. J. Hydrol. 2016, 538, 842–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, L.; Ren, M.; Li, C.; Wang, H. Sponge City Construction in China: A Survey of the Challenges and Opportunities. Water 2017, 9, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Technology Carries Dreams, Innovation Changes the Future––Sponge City. Available online: https://www.cas.cn/kx/kpwz/201703/t20170303_4592127.shtml (accessed on 26 May 2022). (In Chinese).

- China’s ‘Sponge Cities’ Aim to Re-Use 70% of Rainwater–Here’s How. Available online: https://chinadialogue.net/en/cities/10063-china-s-sponge-cities-aim-to-re-use-7-of-rainwater-here-s-how-2/ (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Promote the Construction of “Sponge City” and Help Transform Old Communities. Available online: http://paper.xinmin.cn/html/home/2022-02-23/08/14160.html (accessed on 22 May 2022). (In Chinese).

- Futian, Shenzhen: Old Communities Can Also Become “Sponges”. Available online: http://sz.people.com.cn/n2/2021/1111/c202846-35000184.html (accessed on 22 May 2022). (In Chinese).

- Gu, T.; Li, D.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y. Does Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal Lead to a Satisfying Life for Residents? An Investigation in Zhenjiang, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 90, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Residents “Like” Sponge Reconstruction of Old Residential Areas. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/243956541_99957777 (accessed on 2 July 2022). (In Chinese).

- Sponge Transformation Is Implemented in the Old Community: The Community Is No Longer Flooded, and the Living Environment Is Improved. Available online: https://www.cuwa.org.cn/haimianchengshi4/1339.html (accessed on 2 July 2022). (In Chinese).

- The Ground “Will Drink Water”! “Sponge-Style” Renewal of the Old Communities “Not Afraid of Waterlogging”. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1735518326968013307&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 19 July 2022). (In Chinese).

- Gu, T.; Li, D.; Feng, H.; Huang, G. Identifying and Classifying Resident’s Behavioral Engagement in Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal of China: A Case Study of The Yangtze River Delta. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Constr. 2019, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 40 Year Old Community Needs to Be Transformed and Upgraded, but the Residents Jointly Oppose It. Available online: https://k.sina.com.cn/article_1880087643_700fdc5b01900qzgm.html (accessed on 27 April 2022). (In Chinese).

- The Community Pays Close Attention to the “Extra Staff Supervision” of the Obligation to Carry Out the Transformation of “Sponge City”. Available online: http://www.jsw.com.cn/zjnews/2015-11/03/content3473393.htm (accessed on 13 May 2022). (In Chinese).

- Wright, T.J.; Liu, Y.; Carroll, N.J.; Ahiablame, L.M.; Engel, B.A. Retrofitting LID Practices into Existing Neighborhoods: Is It Worth It? Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shafique, M.; Kim, R. Retrofitting the Low Impact Development Practices into Developed Urban Areas Including Barriers and Potential Solution. Open Geosci. 2017, 9, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai, L.; van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Keessen, A.M. Governance of the Sponge City Programme in China with Wuhan as a Case Study. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2018, 34, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.G.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Environmental Science: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting Green Product Consumption Using Theory of Planned Behavior and Reasoned Action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Explain People’s Energy Savings and Carbon Reduction Behavioral Intentions to Mitigate Climate Change in Taiwan–Moral Obligation Matters. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremers, S.P.J.; de Bruijn, G.-J.; Visscher, T.L.S.; van Mechelen, W.; de Vries, N.K.; Brug, J. Environmental Influences on Energy Balance-Related Behaviors: A Dual-Process View. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhu, Q. Mismatches in Suppliers’ and Demanders’ Cognition, Willingness and Behavior with Respect to Ecological Protection of Cultivated Land: Evidence from Caidian District, Wuhan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Warner, L.A.; Lamm, A.J.; Rumble, J.N.; Martin, E.T.; Cantrell, R. Classifying Residents Who Use Landscape Irrigation: Implications for Encouraging Water Conservation Behavior. Environ. Manag. 2016, 58, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, A.J.; Fielding, K.S.; Newton, F.J. Community Knowledge about Water: Who Has Better Knowledge and Is This Associated with Water-Related Behaviors and Support for Water-Related Policies? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.T.; Sun, M.X.; Song, B.M. Public Perceptions of and Willingness to Pay for Sponge City Initiatives in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, H. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Individual’s Energy Saving Behavior in Workplaces. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Z.G.; Khan, K. Effect of Cognitive Variables and Emotional Variables on Urban Residents’ Recycled Water Reuse Behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon, S.J. Investigating Beliefs, Attitudes, and Intentions Regarding Green Restaurant Patronage: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior with Moderating Effects of Gender and Age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floress, K.; García de Jalón, S.; Church, S.P.; Babin, N.; Ulrich-Schad, J.D.; Prokopy, L.S. Toward a Theory of Farmer Conservation Attitudes: Dual Interests and Willingness to Take Action to Protect Water Quality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Tondeur, J. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM): A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Explaining Teachers’ Adoption of Digital Technology in Education. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Searching for New Directions for Energy Policy: Testing Three Causal Models of Risk Perception, Attitude, and Behavior in Nuclear Energy Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibah, U.; Hassan, I.; Iqbal, M.S. Naintara Household Behavior in Practicing Mental Budgeting Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Financ. Innov. 2018, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.v.; Morgan, D.W. DETERMINING SAMPLE SIZE FOR RESEARCH ACTIVITIES. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsuddin, M.F.; Karim, J.; Salim, A.A. The Outcomes of Health Education Programme on Stress Level among the Caregivers of Post Total Knee Replacement Surgery. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 571027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.N.; Chen, W.P.; Cundy, A.B.; Chang, A.C.; Jiao, W.T. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Public Perception in Contaminated Site Management: Simulation by Structural Equation Modeling at Four Sites in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 210, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Shan, J.; Zhang, W. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Residents’ Coping Behaviors for Reducing the Health Risks Posed by Haze Pollution. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 2122–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballangrud, R.; Husebø, S.E.; Hall-Lord, M.L. Cross-Cultural Validation and Psychometric Testing of the Norwegian Version of the TeamSTEPPS® Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Research on the Path of Residents’ Willingness to Upgrade by Installing Elevators in Old Residential Quarters Based on Safety Precautions. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.G. Understanding Web-Based Learning Continuance Intention: The Role of Subjective Task Value. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, A.; Lado, A.A.; Chen, I.J. Inter-Organizational Communication as a Relational Competency: Antecedents and Performance Outcomes in Collaborative Buyer-Supplier Relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shen, Q.G.; Drew, D.S.; Ho, M. Critical Success Factors for Stakeholder Management: Construction Practitioners’ Perspectives. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ree, M.J. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling Using SPSS and AMOS. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarannum, F.; Kansal, A.; Sharma, P. Understanding Public Perception, Knowledge and Behaviour for Water Quality Management of the River Yamuna in India. Water Policy 2018, 20, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Ng; James Wang; Kelwin Wang Enhancing Public Engagement in a Fast-Paced Project Environment. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Civ. Eng. 2016, 169, 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Research on Residents’ Participation in Urban Communities Construction and Countermeasures––A Case Study of H District in Jiangxi Province. Available online: http://fzmzw.jxfz.gov.cn/art/2019/2/21/art_4138_1908969.html (accessed on 9 July 2022). (In Chinese)

- Li, R.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Zheng, B.; Liu, H. Factors Affecting Smart Community Service Adoption Intention: Affective Community Commitment and Motivation Theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 1324–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, N.; Esfandiyari Bayat, S.; Bijani, M.; Hayati, D.; Viira, A.-H.; Tanaskovik, V.; Kurban, A.; Azadi, H. Understanding Farmers’ Intention towards the Management and Conservation of Wetlands. Land 2021, 10, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, K.; Kay, E. The Opportunities and Challenges of Implementing ‘Water Sensitive Urban Design’: Lessons from Stormwater Management in Victoria, Australia. In Global Issues in Water Policy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 15, pp. 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.J.; Lindsay, J.; Fielding, K.S.; Smith, L.D.G. Fostering Water Sensitive Citizenship-Community Profiles of Engagement in Water-Related Issues. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, N.; Klotz, L. Role of Community Participation for Green Stormwater Infrastructure Development. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suh, D.H.; Khachatryan, H.; Rihn, A.; Dukes, M. Relating Knowledge and Perceptions of Sustainable Water Management to Preferences for Smart Irrigation Technology. Sustainability 2017, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, R.; Chen, M.; Jin, H.; Bao, Z.; Yan, H.; Yang, F. Understanding Perceptions of Plant Landscaping in LID: Seeking a Sustainable Design and Management Strategy. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2017, 3, 05017003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Ecological Behavior’s Dependency on Different Forms of Knowledge. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 52, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Cuerva, L.; Berglund, E.Z.; Binder, A.R. Public Perceptions of Water Shortages, Conservation Behaviors, and Support for Water Reuse in the U.S. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 113, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Hayati, D.; Hochrainer-Stigler, S.; Zamani, G.H. Understanding Farmers’ Intention and Behavior Regarding Water Conservation in the Middle-East and North Africa: A Case Study in Iran. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 135, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Items | Percentage (%) | Variables | Items | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47.37 | Living alone or not | Yes | 58.06 |

| Female | 52.63 | No | 41.94 | ||

| Age | under 20 | 7.97 | Rent or not | Yes | 71.27 |

| 20–34 | 44.42 | No | 28.73 | ||

| 35–49 | 25.29 | Working condition | Unemployment | 12.37 | |

| 50–64 | 16.11 | In employment | 80.99 | ||

| 65 and over | 6.22 | Retire | 6.64 | ||

| Education level | Primary school or below | 5.07 | Monthly income | Less than ¥2000 | 10.26 |

| Junior high school | 29.87 | ¥2000–¥3999 | 20.40 | ||

| High school | 27.76 | ¥4000–¥5999 | 25.05 | ||

| Junior college | 19.67 | ¥6000–¥8000 | 25.47 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 17.62 | More than ¥7999 | 18.83 | ||

| Length of residence | Less than or equal to 1 year | 31.93 | Location | Shanghai | 23.60 |

| 2 to 5 years | 43.21 | Ningbo | 18.65 | ||

| 6 to 10 years | 20.76 | Jiaxing | 18.47 | ||

| More than 10 years | 4.10 | Zhenjiang | 18.83 | ||

| Chizhou | 20.46 |

| Dimensions | Indicators | Rank | Mean Value of Observed Indicators | Mean Value of Latent Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents’ participation cognition | RPC1 | 4 | 3.82 | 3.83 |

| RPC4 | 1 | 3.90 | ||

| RPC5 | 6 | 3.70 | ||

| RPC6 | 3 | 3.84 | ||

| RPC7 | 5 | 3.81 | ||

| RPC8 | 2 | 3.89 | ||

| Residents’ participation attitude | RPA1 | 4 | 3.26 | 3.46 |

| RPA2 | 2 | 3.52 | ||

| RPA3 | 3 | 3.48 | ||

| RPA4 | 1 | 3.57 | ||

| Residents’ participation intention | RPI1 | 4 | 3.49 | 3.56 |

| RPI2 | 3 | 3.53 | ||

| RPI3 | 1 | 3.61 | ||

| RPI4 | 2 | 3.60 | ||

| Residents’ participation behavior | RPB1 | 2 | 3.83 | 3.79 |

| RPB2 | 3 | 3.66 | ||

| RPB3 | 1 | 3.88 |

| Hypothesis | Path Relationship | Standardized Coefficient | Unstandardized Coefficient | Standard Error | T Value | p Value | Hypothesis Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | RPA ← RPC | 0.261 | 0.261 | 0.028 | 9.171 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | RPI ← RPC | 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.028 | 0.355 | 0.723 | Not supported |

| H3 | RPB ← RPC | 0.299 | 0.363 | 0.033 | 11.061 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | RPI ← RPA | 0.534 | 0.575 | 0.034 | 16.788 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | RPB ← RPA | 0.202 | 0.245 | 0.04 | 6.105 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | RPB ← RPI | 0.258 | 0.291 | 0.037 | 7.969 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Indirect Effect | Mackinnon PRODCLIN2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95%CI | ||||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| H4a | RPC → RPA → RPI (Path1) | 0.139 | 0.1133 | 0.1898 |

| H5a | RPC → RPA → RPB (Path2) | 0.052 | 0.0671 | 0.1262 |

| H6a | RPC → RPI → RPB (Path3) | ---- | −0.0119 | 0.0206 |

| H6b | RPA → RPI → RPB (Path4) | 0.137 | 0.1173 | 0.2230 |

| H6c | RPC → RPA → RPI → RPB (Path5) | 0.092 | 0.0618 | 0.1237 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, T.; Hao, E.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Exploring the Determinants of Residents’ Behavior towards Participating in the Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal of China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Land 2022, 11, 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081160

Gu T, Hao E, Ma L, Liu X, Wang L. Exploring the Determinants of Residents’ Behavior towards Participating in the Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal of China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Land. 2022; 11(8):1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081160

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Tiantian, Enyang Hao, Lan Ma, Xu Liu, and Linxiu Wang. 2022. "Exploring the Determinants of Residents’ Behavior towards Participating in the Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal of China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior" Land 11, no. 8: 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081160

APA StyleGu, T., Hao, E., Ma, L., Liu, X., & Wang, L. (2022). Exploring the Determinants of Residents’ Behavior towards Participating in the Sponge-Style Old Community Renewal of China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Land, 11(8), 1160. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081160