1. Introduction

The 1985 earthquake compelled migratory movement from Mexico City to surrounding mid-size cities triggering changes in their socio-economic structure and causing spatial expansion of their territories. One of these urban areas was the metropolitan area of Puebla, with its 38 municipalities, a sleepy colonial city that in previous decades had had quite a stagnant urban development. However, Puebla City’s economic growth had begun a couple of decades before, in the 1960s, with the textile industry and the foundation of the Volkswagen assembly plant. In the 1990s this compact and small city began a rapid transformation into a cosmopolitan multi-functional area looking forward to the new development opportunities of the 21st century.

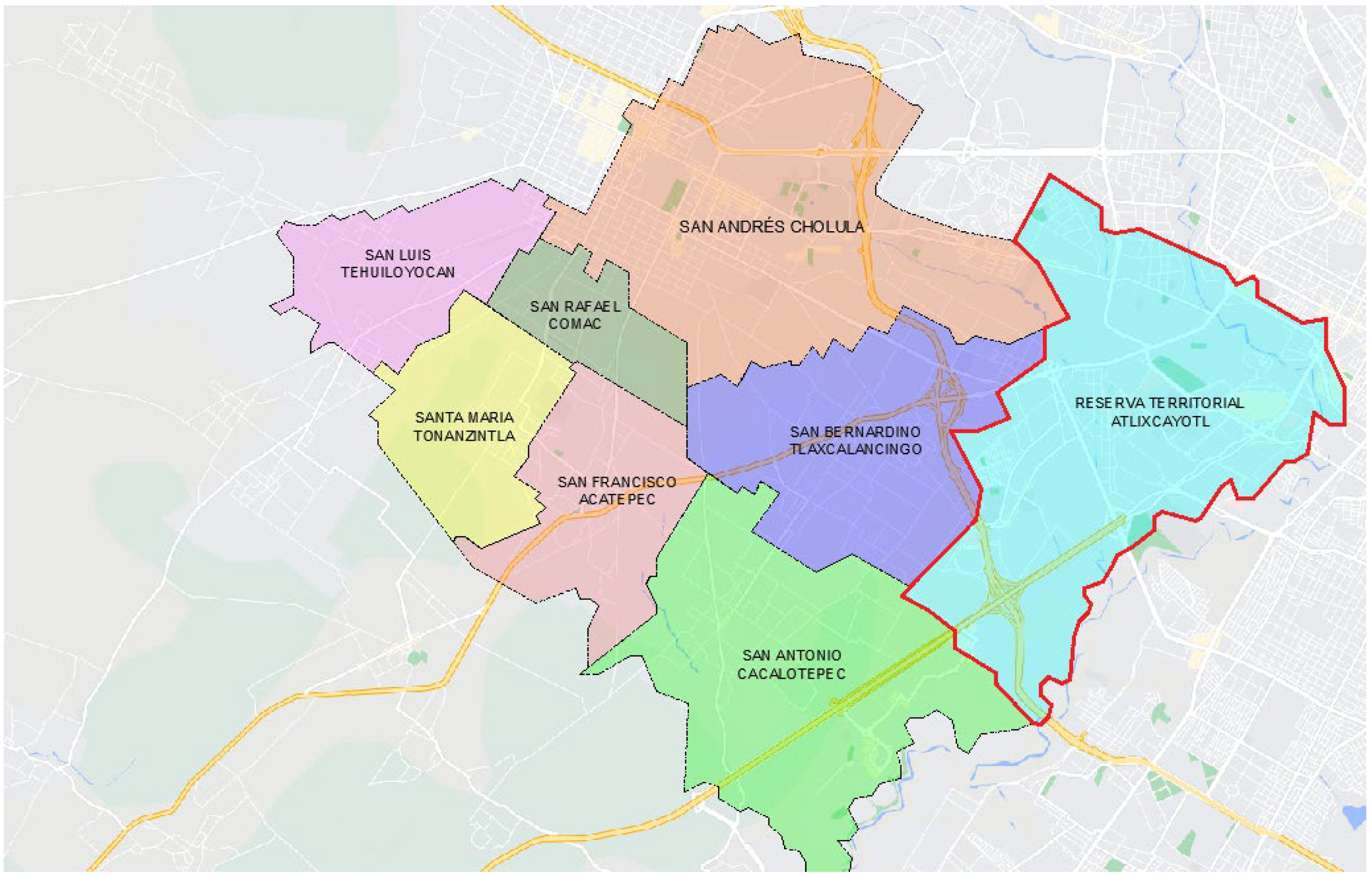

In this context, the neighboring historical and dual city of Cholula, shaped by the municipalities of San Pedro and San Andrés Cholula, also started to change its rural façade to that of an important educational, economic, touristic and residential node. At this point, Cholulas now represented an attractive opportunity to the local authorities and investors, to achieve international recognition for the Puebla metropolitan area, as its rural land offered an invaluable resource for the creation of a “New Puebla” on its territory. Thus began extensive land consumption for urban purposes, and the abandonment of agricultural activities and productive soil to be substituted by massive gated communities, residential and office towers, shopping malls and entertainment centers.

In the decade of 1990, when neoliberal trends promoted a land reform that opened the ejido, one of the forms of land tenure in México [

1], and communal lands to the free market, triggering massive expropriation and urbanization in the peri-urban areas, especially in Cholula lands. In this urban development euphoria, the municipality of San Andrés Cholula was integrated into an ambitious urban plan that intentioned to develop a new economic, services and residential sector between different municipalities (San Pedro Cholula, San Andrés Cholula, Puebla and Cuautlancingo). This “modernization” plan was one of the few that was actually implemented in Mexico, and in order to launch it, it was necessary to expropriate more than 1000 hectares of ejido and agricultural land for its purposes, as described later on.

Today, the contemporary extension of Puebla on Cholula territory has meant urban planning of a new and modern city located on the 1988 expropriated rural land. This Angelópolis Plus-plan of 1993 perceived the economic potential of this area, now called “Atlixcayotl Territorial Reservation”, triggering a legal struggle for some years, between the two municipalities in federal courthouses, over the ownership of these potentially lucrative areas and of the right to enjoy the economic benefits produced by them. Today, residential areas are extending along the expropriated Cholula lands, despite the legal disputes produced by the expropriation and land invasion by the real estate business, supported by the neoliberal public policy of the state. The extending “new urbanism” and “urban modelling” inspired by Southeast Asian examples, distinguish their elitist land use, creating isolated urban “bubbles” or “micro states”, disconnected from and ignoring their location on the Cholula lands. The result has been, in García Vázquez’s words, that the two municipal territories have been “liquated” [

2] as it is no longer possible to distinguish where Puebla ends and Cholula begins. The real estate development here, with its desire to create a imaginary of a piece of a cosmopolitan global city, is devouring the lands of those who are economically and legally weaker, who cannot defend themselves in front of the dominating political and economic forces.

Thirty years later, the neoliberal transformations began and some important resistances are emerging in San Andrés Cholula related to land management and right to the land, struggling against the state-supported real estate business appropriating the communal lands. This resistance denounces the evident absence of the state in promoting good urban governance on the peripheries, the result of which, in municipalities such as San Andrés Cholula, is a more segregated and less integrated urban structure and territory, considering its socioeconomic sectors. Here, urban zoning is the dominant planning method with which real estate developers drive urban growth. Thus, this paper tackles the problematics of neoliberal urban planning strategies, in which real estate developers have been the driving force.

3. Method

3.1. Case Study and Digital Tools

This work is carried out by applying a case study as a research method. The intention is to use the territory of Cholula to analyze the logic and processes of neoliberal urbanism in an area that is still in the process of conversion from rural to urban land. It is intended to find the manifestations of these processes and their consequences. Likewise, it is intended to highlight the effects that this development model has in terms of landscape and the physical–morphological dimension of the territory, and its effects at the socio-cultural level, and even in the symbolic sphere. Digital technology tools are used.

In the first instance, current legislation and available planning documents were reviewed. Field visits were also undertaken to survey the territory and photographs were taken to show the current state of the landscape and the manifestations of neoliberal urbanism that have been emerging recently. These features are identified by the characteristics highlighted in the theory framework. The field work also included both formal and informal encounters with the current inhabitants of the area and their representatives: leaders of neighborhoods and civil associations. In addition, municipality authorities were consulted. The mentioned encounters were useful in terms of broadening the project’s vision of the socio-cultural, economic and territorial characteristics, and particularities of the territory and the changes happening in it. In addition to this, and using the theoretical framework developed, criterion for the analysis of the study areas were established. In this sense, the integration of 3D modeling tools were chosen in order to work and show the results of this analysis. It was discovered that 3D modelling is a useful tool for the research and mapping of the current territorial situations. It helps to evidence the morphological changes in the urban structure and land occupation.

The use of digital tools, accompanied by field work, allowed the mapping of the effects of the physical manifestations caused by the neoliberal urbanism model, such as changes and in the urban density and scale, and emerging contrasts between the new urban cores and the traditional rural community lands. In this respect, this work intends to serve as a framework to develop a methodology to map and analyze information. It aims to be able to create a sequence of images of changes along the neoliberal process of land management and urban planning in Cholula.

3.2. Digital Modeling of Neoliberal Urban Development

Urban modeling is a concept that has been developed since the 1970’s, with the introduction of computers in design. In 1976, Michael Batty defined urban modeling as “computer-based simulations used for testing theories about spatial location and interaction between land uses and related activities” [

22]. Several examples and studies have been developed in the last 20 years, applying urban modeling. Vanegas’s work [

23] shows an overview of the methods covering computer graphics and related fields of urban modeling with information available on the internet in order to observe the appearance and the behavior of dense urban spaces. Another example presented by Brian, ref. [

24] explores new theories and technologies of digital modeling to create an interactive three-dimensional drawing situated in the history of urban theory, design and final representation. Similarly, ref. [

25] Hamilton presents how to develop an urban model to accommodate data sets to different aspects of city planning.

In this work, a first phase is developed, as mentioned by Vanegas [

23], the 3D modeling tools have been used for evidencing the fractured structure of the urban territory of Cholula, taking as an example the area between the San Rafael Comac community, the San Andrés Cholula municipality center—

cabecera municipal—and the Atlixcayotl Territorial Reservation, where one of the modern Angelópolis urban centers—Sonata area—has been developing, elaborated using different open access digital platforms. The process has consisted of four stages of data capture: 1. The architectural and urban geometry of the study area has been modeled based on the OpenStreetMap platform, using the Esri World Imagery and Opentopomap background. In this stage, basic parameters of the typology of the buildings such as measurements and area, are captured; 2. The data of heights and number of floors of the buildings has been obtained using the Google Earth Pro platform and subsequently, these parameters are captured in OpenStreeMap; 3. The data of utilization of each of the buildings has been obtained from Google Maps and verified with field visits, allowing the corroboration of the data obtained from the digital platforms with the reality on site; and 4. The capture of the data is visualized in a 3D model using the CadMapper platforms and the Urbano add-on for Grasshopper of Rhinoceros 7, allowing the observation of the urban image and the use of each of the buildings in the studied area.

The second phase, similar to that proposed by Hamilton [

25], is part of future work, where using another digital platform such as Microsoft Planetary Computer, and tools such as digital satellite photos, will allow the analysis of urban areas through spatial metrics, data processing, mapping strategies and advanced visualizations.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Urban Modeling in Cholula’s Territorial Development and Image

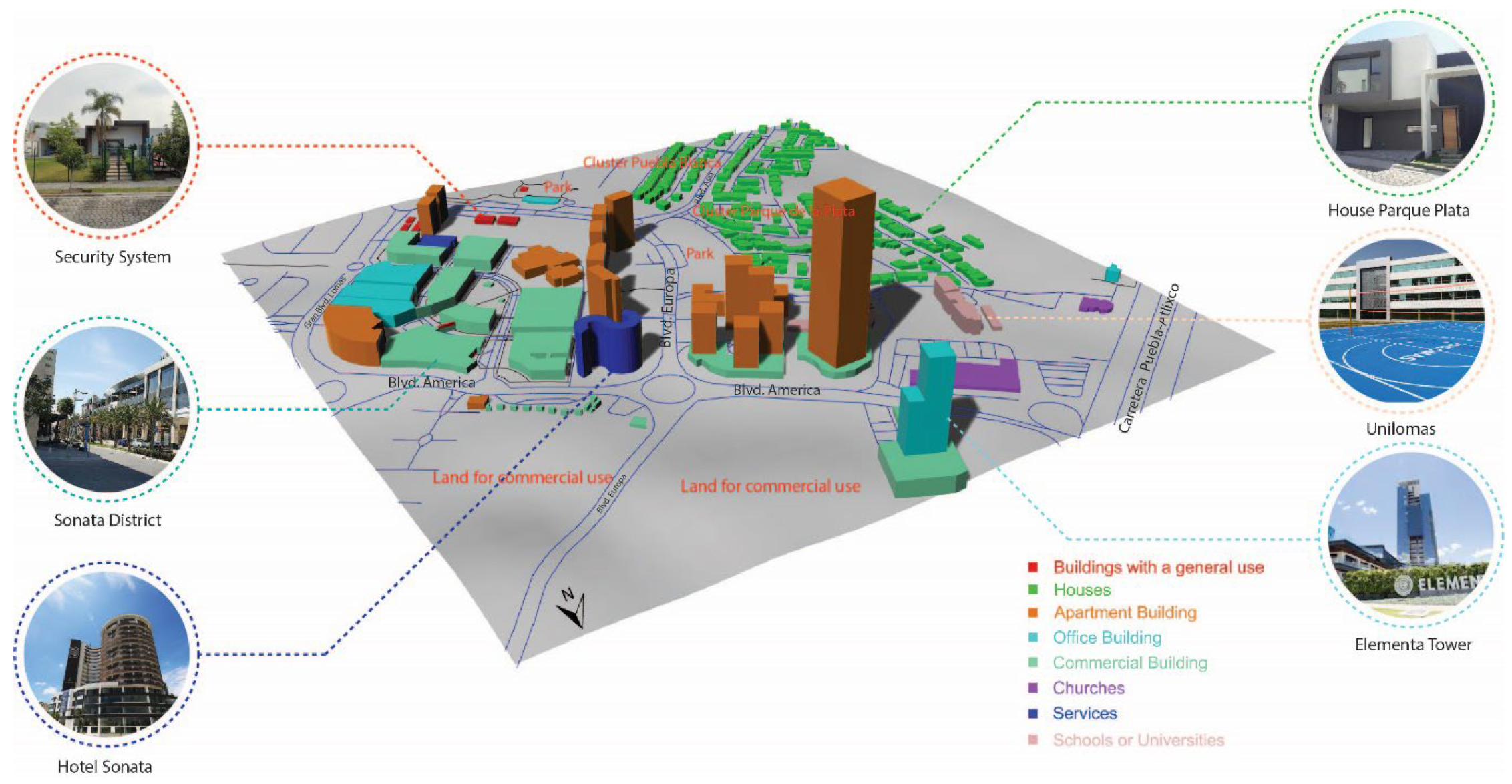

Using digital modeling,

Figure 3 shows how the private land use has been expanding in recent years on the outskirts of the rural community of San Rafael Comac, neighboring the Angelópolis Territorial Reservation. There has been no control over the intended use of the land; everything has been built, from private residential areas, appearing in the image in green, to industrial warehouses. The absence of all-covering urban planning is clearly observable in the lack of basic urban services such as the inexistence of potable water networks or sewer systems, as well as in the street net that is not designed and built for truck traffic, in the case of the warehouses and industrial buildings. What we can also observe here is the invasion of agricultural land by small islands of buildings separated by large tracts of land (the galaxy-like structure mentioned by García Vázquez [

2,

20]). The gradual occupation of rural land by the real estate business is gradually displacing the original people of the area as, in their own words, the property taxes for land ownership, due to territorial transformation described above, are getting too expensive for them, obliging them to sell their land.

With the arrival and growth of real estate business in the Angelópolis Territorial Reservation, the predatory use of land for real estate business stands out, highlighting the Sonata District next to the previously mentioned rural community areas. In the district, on a small portion of land of 1 km

2 (

Figure 4), there are diverse land uses, with commercial and residential use prevailing. Currently, the remaining plots of land around Sonata are being developed, mainly by the construction of commercial centers, highlighting the Downtown shopping center proposal with its planned 25,000 m

2 of commercial units.

In terms of the urban image of the Sonata District, the new constructions are mainly identical two-story houses built in series in private residential areas and gated communities, and exclusive apartment buildings, malls and other commercial services, as seen in

Figure 4.

As the model clearly shows, the new urban structure consists of land uses characteristic for dense contemporary urban centers and their corresponding architectural scaling. Here, the use of land is maximized, concentrating multiple uses in a quite reduced area of land, having in mind the optimum results from the point of view of the real estate business. These dense urban concentrations, such as Sonata District, not only invade agricultural lands but also negatively impact the local water resources, affecting the remaining agricultural production. The lack of water, on the other hand, has also been triggering the erosion of the surrounding lands.

4.2. Consequences of the Implementation of Neoliberal Logics in the Study Area

In the study area, the logics of a banal urbanization, almost empty of situational meaning can be observed. The following are some of the identifiable elements in this regard: gated communities, street closures, privatization of public space, isolation through control filters, and surveillance cameras evidencing exclusive land uses. All these elements promoted by the neoliberal city production model fracture the territory, not only from the physical–morphological dimension, but above all, and more dramatically, considering the socio-cultural and socio-economic dimension. As the principle, urban life is subject to this separation of the private sphere from what could be defined as public life. Many of the dynamics that are promoted from this configuration of the territory are translated into dynamics in which any contact with public space is excluded and relegated, in some cases, to an infrastructural function of mobility.

This has also caused a homogenization of the “landscape”: the streets are reduced to accesses to private properties with a false sense of security (

Figure 5), and, in the best cases, interspersed with anodyne commercial squares where the main activity is consumption. Beyond this, in this context, any trace of identity of the territory is eliminated, even in symbolic terms. We should start with the understanding that we are in a territory of rural vocation in the process of reconversion with ancestral logics of production and management of resources, and a neighborhood organization responding to traditional issues. “These processes have determined a progressive emptying of the attributes of the geographical landscape in general and of the urban landscape in particular. To illustrate this, it is enough to recall the progressive specialization of territories dedicated to the production of landscapes especially designed for the media and visual consumption of metropolitan populations: the natural landscape, the historical urban landscape or the port urban landscape would be three very clear examples.” [

16].

There is the risk of the emergence of a non-existent territoriality, a landscape independent of place. In this sense, the production of this new territory is unlinked and disarticulated from the place. There is no trace of something locally meaningful telling us where we are. This is not only serious in terms of the physical construction of the environment, but above all, in symbolic terms. Thus, private bubbles are generated with the main goal of isolating themselves from their immediate context for reasons that go through false sensations of security, but also due to questions of representation and aspirational issues that deny the place and seek generic environments with homogeneous spaces.

In any case, the observable result of this neoliberal production model of the territory depends mostly on the management and administration of the land. Taking advantage of the available planning instruments that are adapted to an urban modelling framework has very little to do with sustainable issues in relation to the place, its character and its symbolic dimension. In this sense, these do not consider the socio-cultural dynamics that could promote socio-spatial justice [

17,

26], which should be an a priori concept for intervention in this type of territory, considering not only the contextual features of the area, but enhancing the possibility to balance the land in terms of opportunities and rights, as well as the notion of nature and other forms of life.

Without denying that urban growth or development is inevitable, it is necessary to create sensible and inclusive land management instruments to adequately regulate the development of territories such as Cholula, in the framework of social justice [

26].

5. Discussion

5.1. Statement 1: Neoliberal Urban Development Is the Dominant Logic in the Urban Development of the Area between the San Andrés Cholula Municipality Center and the Atlixcayotl Territorial Reservation

There are several manifestations related to the commodification of land and urban image observed in the urban development: (1) The city and the land are seen as a tradable goods, (2) The urban development and the public policy related to it are informed by economic interests, and (3) The land use and urban image are established to satisfy the commercial needs of the commodification of the territory.

Regarding this first statement, and after studying international examples of urban development related to globalization and the “worlding of cities”, we can observe the same kind of tendencies as in the cities of Southeast Asia, in which the land has been converted into merchandise and traded as such. What is also observable in San Andrés Cholula and its Atlixcayotl Territorial Reservation area is that the urban image, perceived as contemporary and “worldly”, gives the land an added value that makes it more commodifiable. For a middle-size city of a developing country, such as Puebla, and its political and economic leaders to be included in the category of global cities is a tempting idea. Being global means to be able to attract fresh economic flows and international investment, as well as new, economically, socially and professionally competitive inhabitants. Thus, the city itself and its urban image work as an attractor and a good promotor nationally and internationally to reach those focus groups and businesses that are wanted to establish themselves in the area.

5.2. Statement 2: Neoliberal Urban Development Promotes Predatory Land Use Development and Peri-Urban Anarchy in San Andrés Cholula

The neoliberal urban planning has triggered changes in the possession of land, triggered by: (1) Expropriation of private and communal agricultural lands to be commodified, (2) The elevated property taxation obliging local rural habitants sell their lands and move elsewhere, (3) The real estate business, sheltered by the public policy favoring it, is appropriating growing extensions of Cholula territory to use for its own commercial purposes, and (4) New, densely urbanized and constructed areas are severely affecting the local underground water supply, affecting the ecological balance and agriculture.

The territory of the municipality of the city of Puebla has no free land left to extend to. Thus, the “New Puebla” had to be created beyond the existing urban limits, triggering the first expropriations in 1988 of the communal agricultural lands of San Andrés Cholula, beyond the Atoyac river. Meanwhile the urban development has accelerated in this area, more expropriations have been carried out, creating resistance between the original Cholula communities and the Puebla state authorities. On the other hand, commodification of the land by the real estate business has elevated the value of the land, and with it, the property taxes, making them unaffordable for the local rural population depending on income from traditional agriculture. Thus, the most vulnerable groups of the local population have had to sell their properties and move elsewhere, severely affecting the socio-cultural structure and identity of San Andrés Cholula’s rural communities. Besides the mentioned effects, the ecological deterioration of the land and landscape are menacing the basic food security of the local population who depend mainly on traditional agriculture and who have also been an essential part of the territory’s identity for centuries.

5.3. Statement 3: Neoliberal Urban Development Has Triggered a Territorial Fracture of San Andrés Cholula, Characterized by Socio-Territorial Inclusion and Exclusion

The urban development in San Andrés Cholula divides the urban territory into two categories: (1) That of the traditional use of communal lands for agricultural purposes, related to local meanings, religious rites and the community’s socio-territorial organization, as the basis for the local cultural identity and food security, (2) The Angelópolis Territorial Reservation area, comprised of the land, the city, the public space and the architecture, is a consumer good related to social status and a fashionable lifestyle, and (3) The socio-territorial tensions between the two categories are triggering frictions between the original habitants and newcomers who have been sheltered many times by the municipality and state administration.

The socio-cultural and socio-territorial structure of San Andrés Cholula is based on a millenary tradition with its roots deep in pre-columbine times. It has been a system that, throughout the centuries, has given a framework for the community identity, values and daily life. It is a structure that still today unites the community members. The land has an important role in this system and in the local identity, the meaning of which goes far beyond its economic value; the land is connected with the cultural roots of the local community. Thus, there is a collision between this local conception of the land and that of the municipal, state administration and real estate business focused on the economic value of the land and speculation. When the latter is applied to urban planning, friction appears, as local communities are defending their right to their ancestral lands.

This also prevents the communities from having the right to accomplish an urban development that promotes their own interests and embraces their right to the city [

27]. In that sense, the land is seen only as a means of production in terms of economic value, as previously discussed.

5.4. Statement 4: In Situations Such as That of San Andrés Cholula, the Local Communities and Their Participation in the Land Management and Planning Processes Can Be Empowered by Effective Negotiations between Different Stakeholders, Taking Advantage of the Protection the Mexican Constitution Gives to Traditional Communities

As Wong-González [

28] points out, (1) territorial development has a multidimensional and multifunctional nature that crosses several planning areas such as economic, technical, social, physical, political, environmental and spatial ones. Thus, (2) as the author mentions, urban territories are privileged spaces where land management, ecological land management and socio-territorial questions can be integrated, but (3) adequate municipality and state mechanisms are needed to integrate all the stakeholders to effective and inclusive negotiations.

The San Andrés Cholula of today, is certainly of a multidimensional character, in which ancestral socio-cultural and socio-territorial organization has its encounter with contemporary land management and political interests, informed by globalization and neoliberal economic ideals and in which traditional ways of life are face-to-face with contemporary lifestyles. Recently, being aware of the complexity of an inclusive planning task the municipality administrations is facing now, the authorities seem to have a political interest to integrate different local stakeholders into the process through the establishment of the Municipal Council for the Urban Development and Housing, in order to work on a new sustainable and inclusive urban development plan. The municipality administration is proposing the organization of public consultation among the inhabitants of the local rural communities in order to give visibility to their demands and preoccupations regarding land management. On the other hand, representants of the real estate industry are also invited to participate in the process, as well as the local associations of architects, urbanists and engineers, and universities and researchers. Hopefully this initiative could have equitable results in order to create an effective planning tool to defend the local inhabitants’ rights to the land and to control real estate predatory land use practices. This has a negative impact, not only on the morphological dimension, but on social diversity and inclusion, in what Ascher proposes as accessibility [

29]

6. Conclusions

Research work carried out in San Andrés Cholula demonstrates that the Atlixcayotl Territorial Reservation area, as the planned extension of the city of Puebla, has been rearticulated and reassembled since 1993, in the framework of neoliberal public policy represented by the Angelópolis Plus-plan, triggered by economic and political interest related to globalization and the commodification of land. Thus, finding similarities between the development of the Atlixcayotl Territorial Reservation and that of globalizing cities in Southeast Asia mentioned by Ong [

9], the land management here has also been highly speculative through the construction of urban imagnaries considered desirable and attractive to draw the attention of certain groups of economic actors and the real estate industry. The tool for the creation of this imagery has been the “urban modelling” strategy inspired by successful foreign examples, such as Singapore, and having as the goal constructing an idea of a “world-class” urban environment, but curiously, not inside the urban borders of the city of Puebla but on the territory of the neighboring rural municipality of San Andrés Cholula. Clear enough, the Angelópolis Plus-plan initiated a series of legal disputes between local communities, the municipality and state authorities, and the real estate business, over the rights to the land, and even through legal repression of resistance and expropriation. Thus, as Goldman points out [

10], the logic of land speculation became the central part of the new political rationality, giving framework to the collisions between the rights of the local communities and the public planning policy of government authorities.

The present study also observed the development dynamics in the polygon limited by one of the rural communities of San Andrés Cholula, San Rafael Comac, and the Sonata District of the Angelópolis Territorial Reservation, as examples of the urban transformation in the whole region, triggered by the commodification of land. Having the opportunity to be in touch with the local population of the zone gave substance to the research statements mentioned above by considering people’s demands for a more sustainable and inclusive urban planning. Thus, the questions presented in the introduction of this article can be answered: (1) The neoliberal urban development in the Puebla–Cholula region was initially triggered by a public policy that intentioned to catapult Puebla as a Latin American node in the network of global cities and through this, stimulate the emergence of a new urban economy in the framework of creative economy as a transformative power. (2) As physical and territorial manifestations of the neoliberal development in the area, we can highlight the real estate business as the driving force in the urban planning, interpreting the land as a consumer good. On the other hand, the urban image of the Atlixcayotl Territorial Reservation is an example of “urban modelling”, through which the imagery of a “world city” was intentioned to be created: sculptural office and residential towers, gleaming cultural centers and exclusive gated communities repeat the models seen in other global cities all over the world. (3) For San Andrés Cholula, effective and inclusive land management is essential, as we are talking about a millenary community with its socio-cultural and socio-territorial mechanisms and organization with deep historical roots that have permitted it to survive through time. The land and land use are part of the community identity, and as such, are not commodifiable. Thus, in whichever planning process, the local population should be heard and their demands considered beyond economic or political interests. (4) The intensified real estate business activity in the zone, high property taxes, voluntary or forced displacement of the original population, decrease in water resources affecting the agricultural activities, local ecological disbalance and constant fracturing of the Cholula territory into disconnected pieces has triggered the community awareness about the urgency of active participation in the municipality decision-making processes regarding land management. Finally, (5) public consultation among the local population and the participation of community representatives in the decision-making processes are necessary to guarantee the equilibrium between the community and economic and political interests. This can also contribute to the idea of the management of the symbolism of the land [

30]. It is important to remember that the Mexican Constitution protects the rights of communities considered as “original”, giving them a valuable legal tool to defend their land and their culture. Thus, through the combination of these different mechanisms, the urban development of territories, such as that of San Andrés Cholula, could achieve a more balanced, inclusive and sustainable character.