Post-Coal Fantasies: An Actor-Network Theory-Inspired Critique of Post-Coal Development Strategies in the Jiu Valley, Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

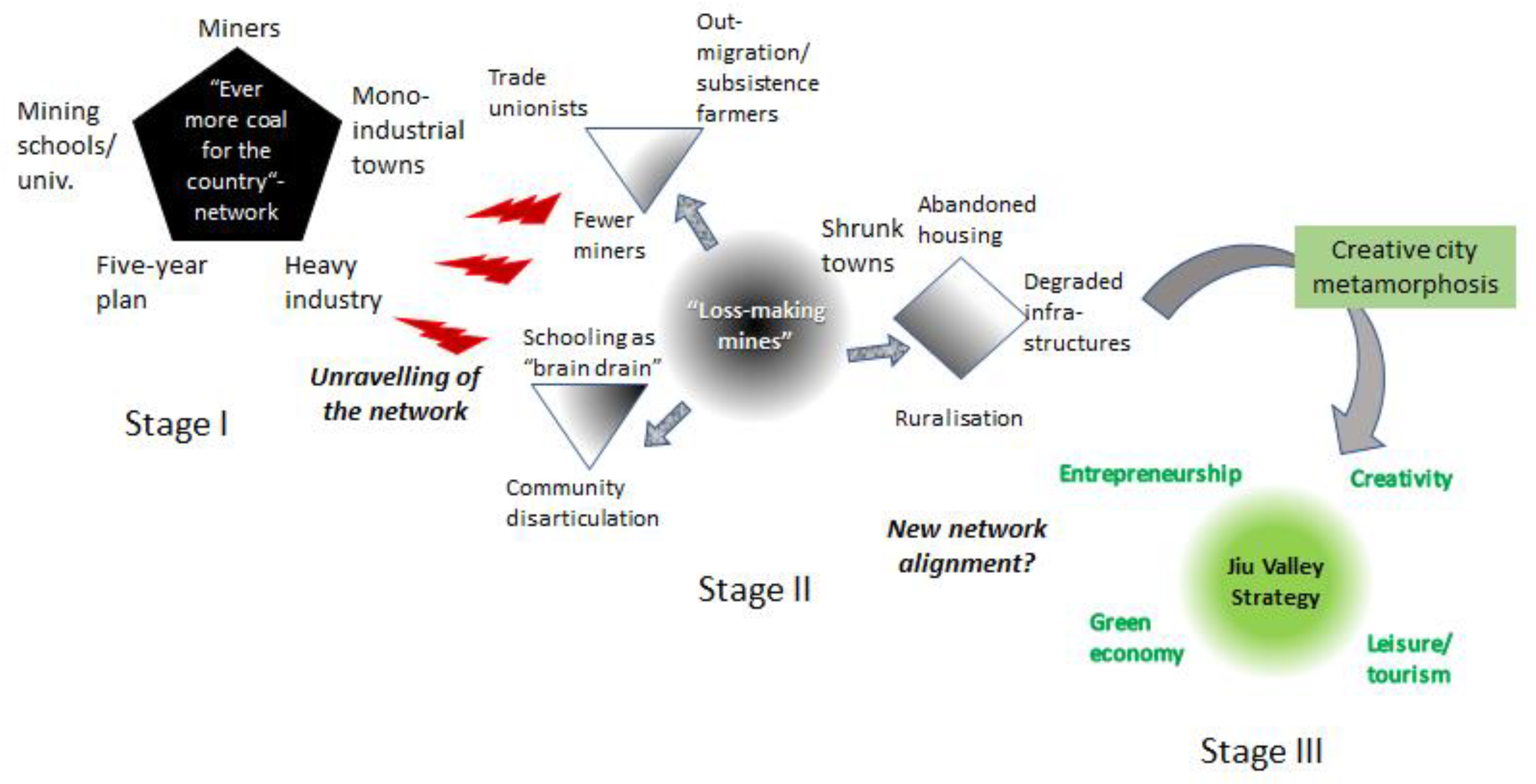

2. Theoretical Background: Stages of Actor (Mis)Alignment

3. Methodology and Case Description

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Network Alignment during the Planned Economy

“In Romania’s Jiu Valley, the state had long taken a paternal role with the miners, providing them free housing, electricity, heat, water and highly subsidized food in order to assure the promise of upward mobility.”[27] (p. 432)

4.2. The Network Unravels: The Violent Misalignments of the 1990s and Beyond

- The shrinking of the working class and migration to rural areas, a phenomenon typical of pre-capitalist societies;

- Insecurity, unemployment, underemployment, and lack of employment opportunities;

- The deterioration of the standard of living and the loss of the working class prestige for (heavy) industrial workers;

- Degradation of the housing stock;

- Degradation of urban infrastructure;

- Reduced access to education and health services.

4.3. Towards a New Alignment? The Jiu Valley Strategy and the Challenge of a Just Transition

- Improving the quality of life and creating a healthy and sustainable environment for future generations.

- Economic diversification, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

- Sustainable use of local specificity.

- Accessibility, mobility, and connectivity.

5. Conclusions

“The encouragement to develop extractive industries is often coupled with the advice to avoid developing an excessive dependency on a single economic sector. [However] the very regions and nations having the greatest need to hear such advice may also have the lowest realistic ability to respond to it.”[69] (p. 305)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, J. Just transitions for the miners: Labor environmentalism in the Ruhr and Appalachian coalfields. New Political Sci. 2017, 39, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocheci, R.M.; Ianos, I.; Sarbu, C.N.; Sorensen, A.; Saghin, I.; Secareanu, G. Assessing environmental fragility in a mining area for specific spatial planning purposes. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2019, 27, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Harrahill, K.; Douglas, O. Framework development for ‘just transition’ in coal producing jurisdictions. Energy Policy 2019, 134, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafry, T.; Watson, E.; Mattar, S.D.; Mikulewicz, M. Just Transitions and Structural Change in Coal Regions: Central and Eastern Europe; Glasgow Caledonian University: Glasgow, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Americo, A.; Billingham, C. The New Social Contract: A Just Transition; Foundation for European Progressive Studies: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Popp, R. A Just Transition of European Coal Regions Assessing Stakeholder Positions Towards the Transition Away from Coal. In E3G Briefing Paper; E3G: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, N.; Brunsting, V.; Wood, D.; Adler, J.; Amin, A.L.; Baines, C. Investing in a Just Transition: Why Investors Need to Integrate a Social Dimension into Their Climate Strategies and How They Could Take Action. 2018. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Robins-et-al_Investing-in-a-Just-Transition.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Weller, S.A. Just transition? Strategic framing and the challenges facing coal dependent communities. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Spiegel, S. Coal, Climate Justice, and the Cultural Politics of Energy Transition. Glob. Environ. Politics 2019, 19, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.; Martiskainen, M.; Hook, A.; Baker, L. Decarbonization and its discontents: A critical energy justice perspective on four low-carbon transitions. Clim. Chang. 2019, 155, 581–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Callon, M. Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 32, 196–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M. The Sociology of an ActorNetwork: The Case of the Electric Vehicle. In Mapping the Dynamics of Science and Technology: Sociology of Science in the Real World; Callon, M., Rip, A., Law, J., Eds.; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Callon, M.; Law, J. After the individual in society: Lessons on collectivity from science, technology and society. Can. J. Sociol./Cah. Can. De Sociol. 1997, 22, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, L.S. Translation alignment: Actor-network theory, resistance, and the power dynamics of alliance in New Caledonia. Antipode 2012, 44, 806–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. Expulsions. Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy; Harvard University Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mocanu, D. Marș forțat pe Valea Plângerii [Forced march in the valley of tears]. Rev. Univers Strateg. 2020, 11, 292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Cobârzan, B. Environmental Rehabilitation of Closed Mines. A Chase Study on Romania. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2008, 4, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- ProTv. România, te Iubesc: Înapoi în Mine [“Romania, My Love: Back to the Mines”]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZsWHJwBxCag (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Jiu Valley Strategy (JVS). Strategia de Dezvoltare Economică, Socială și de Mediu a Văii Jiului (2022–2030) [The Strategy for the Economic, Social and Environmental Development of the Jiu Valley (2022–2030)]. Available online: https://mfe.gov.ro/hg-strategia-valea-jiului/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Wang, X.; Lo, K. Just transition: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life; Basic Books: North Melbourne, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class–Revisited: Revised and Expanded; Basic Books (AZ): New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 1989, 71, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M. Techno-economic networks and irreversibility. Sociol. Rev. 1990, 38, 132–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Weng, D.; Liu, H. Decoding Rural Space Reconstruction Using an Actor-Network Methodological Approach: A Case Study from the Yangtze River Delta, China. Land 2021, 10, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M. Struggles and negotiations to define what is problematic and what is not. In The Social Process of Scientific Investigation; Knorr, K., Krohn, R., Whitley, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980; pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Turnock, D. The pattern of industrialization in Romania. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1970, 60, 540–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J. The spaces of actor-network theory. Geoforum 1998, 29, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J. After ANT: Complexity, naming and topology. Sociol. Rev. 1999, 47, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Societatea Națională de Închideri Mine Valea Jiului [The Jiu Valley National Mine Closure Society]. Mineritul în Valea Jiului—Repere Istorice [Mining in the Jiu Valley—Key Moments]. Available online: http://www.snimvj.ro/istoric.aspx (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Faur, F.; Marchiș, D.; Nistor, C. Evolution of the Coal Mining Sector in Jiu Valley in Terms of Sustainable Development and Current Socio-Economic Implications. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 49, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Digi24. Minele din Valea Jiului au Ajuns la o Producție de Circa 1.000 de Tone de Cărbune pe zi [Jiu Valley Mines Reached a Production of about 1.000 Tons of Coal per Day]. 2022. Available online: https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/economie/energie/minele-din-valea-jiului-si-au-revenit-si-produc-circa-1-000-de-tone-de-carbune-pe-zi-1867199 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Burlacu, R.; Suditu, B.; Gaftea, V. Just Transition in Hunedoara. Economic Diversification in a Fair and Sustainable Way. Available online: https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/just-transition-hunedoara.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Chiribuca, D. The impact of economic restructuring in mono-industrial areas: Strategies and alternatives for the labor reconversion of the formerly redundant in the Jiu Valley, Romania. Studia Univ. Babes-Bolyai-Sociol. 1999, 46, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- LaBelle, M.C.; Bucată, R.; Stojilovska, A. Radical energy justice: A Green Deal for Romanian coal miners? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, J. Planning the City of Socialist Man. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1962, 28, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasti, V. Un deceniu de transformări sociale [A decade of social transformations]. In Un Deceniu de Tranziție. Situaţia Copilului şi a Familiei în România [A Decade of Transition. The Situation of the Child and Family in Romania]; Mihăilescu, I., Ed.; UNICEF: Putrajaya, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kideckel, D.A. The socialist transformation of agriculture in a Romanian commune, 1945-62. Am. Ethnol. 1982, 9, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgescu, B. România si Europa. Acumularea Decalajelor Economice (1500–2010) [Romania and Europe. The Accumulation of Economic gaps (1500–2010)]; Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jigoria-Oprea, L.; Popa, N. Industrial brownfields: An unsolved problem in post-socialist cities. A comparison between two mono industrial cities: Reşiţa (Romania) and Pančevo (Serbia). Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 2719–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelenyi, I. Urban development and regional management in Eastern Europe. Theory Soc. 1981, 10, 169–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdery, K. What was Socialism, and What Comes Next? Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu, I.P. Shrinking cities in Romania: Former mining cities in Valea Jiului. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănică, A.; Istrate, M.; Tudora, D. (N) ever Becoming Urban? The Crisis of Romania’s Small Towns. In Peripheralization; Fischer-Tahir, A., Naumann, M., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich Lehmann, S.; Ruble, B.A. From ‘Soviet’ to ‘European’ Yaroslavl: Changing neighbourhood structure in post-Soviet Russian cities. Urban Stud. 1997, 34, 1085–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorova, E. Reinventing a Russian Mono-Industrial Town: From a Socialist ‘Town of MINERS’ to a Post-Socialist ‘Border Town’; Itä-Suomen yliopisto: Joensuu, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kideckel, D.A. Coal Power: Class, Fetishism, Memory, and Disjuncture in Romania’s Jiu Valley and Appalachian West Virginia. Anuac 2018, 7, 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tsantis, A.; Pepper, R. Romania-Industrialization of an Agrarian Economy under Socialist Planning; The World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Vasi, I.B. The Fist of the Working Class: The Social Movements of Jiu Valley Miners in Post-Socialist Romania. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2004, 18, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R. Shock and subjectivity in the age of globalization: Marginalization, exclusion, and the problem of resistance. Anthropol. Theory 2007, 7, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, C. Ruling Ideas: How Global Neoliberalism Goes Local; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Larionescu, M.; Rughiniş, C.; Rădulescu, S.M. Cu Ochii Minerului: Reforma Mineritului in Romania:(Evaluari Sociologice si Studii de caz) [with Miner’s Eyes. Mining Sector Reform in Romania (Sociological Evaluations and Case Studies)]; Gnosis: București, Romania, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kideckel, D. Miners and wives in Romania’s Jiu Valley: Perspectives on postsocialist class, gender, and social change. Identities Glob. Stud. Cult. Power 2004, 11, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscă, M.; Trifan, E. Participarea Femeilor în Procesul de Tranziție Justă. Analiza Condițiilor Sociale și de Muncă ale Femeilor din Valea Jiului [Women’s Participation in the Just Transition Process. The Analysis of Women’s Social and Working Conditions in the Jiu Valley]; Hecate: București, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Țoc, S.; Guțu, D. Migration and Elderly Care Work in Italy: Three Stories of Romanian and Moldovan Care Workers. Cent. East. Eur. Migr. Rev. 2021, 10, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Crăciun, M.; Grecu, M.; Stan, R. Lumea văii. Unitatea Minei, Diversitatea Minerilor. [The World of the Valley. The Unity of the Mine, the Diversity of the Miners]; Paidea: Bucharest, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu, I.P.; Dascălu, D.; Sucală, C. An activist perspective on industrial heritage in Petrila, a Romanian mining city. Public Hist. 2017, 39, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Creșterea și Contracția Orașelor din România: O Analiză Spațială [Growth and Contraction of Romanian Cities: A Spatial Analysis]. Available online: https://www.mdlpa.ro/userfiles/sipoca711/anexe_livrabil1_2.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Ministry for Development, Public Works and Administration. Strategia de Dezvoltare Teritorială a României [Romania’s Territorial Development Strategy]. 2016. Available online: https://www.mdlpa.ro/pages/sdtr (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Krzysztofik, R.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Kłosowski, F. Between Industrialism and Postindustrialism—the Case of Small Towns in a Large Urban Region: The Katowice Conurbation, Poland. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Germuska, P. Between Theory and Practice: Planning Socialist Cities in Hungary. In Urban Machinery: Inside Modern European Cities; Hard, M., Misa, T., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, R.; Šerý, O.; Alexandrescu, F.; Malý, J.; Mulíček, O. The establishment of inter-municipal cooperation: The case of a polycentric post-socialist region. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Dan. J. Geogr. 2020, 120, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Competition Council. Un Deceniu de Dezvoltare Regională în România. Studiu Privind Impactul Ajutoarelor de Stat Acordate în Zonele Defavorizate [A Decade of Regional Development in Romania. Study on the Impact of State Aid in Disadvantaged areas], 2010. Available online: http://www.ajutordestat.ro/documente/Brosura%20DRMCAS-Final%206Dec_662ro.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- ILO. Guidelines for a Just Transition towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan, J. Fantasy City: Pleasure and Profit in the Postmodern Metropolis; Routledge: England, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Borén, T.; Young, C. Conceptual export and theory mobilities: Exploring the reception and development of the “creative city thesis” in the post-socialist urban realm. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2016, 57, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrescu, F.; Osman, R.; Klusáček, P.; Malý, J. Taming the genius loci? Contesting post-socialist creative industries in the case of Brno’s former prison. Cities 2020, 98, 102578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenburg, W.R. Addictive economies: Extractive industries and vulnerable localities in a changing world economy. Rural. Sociol. 1992, 57, 305–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

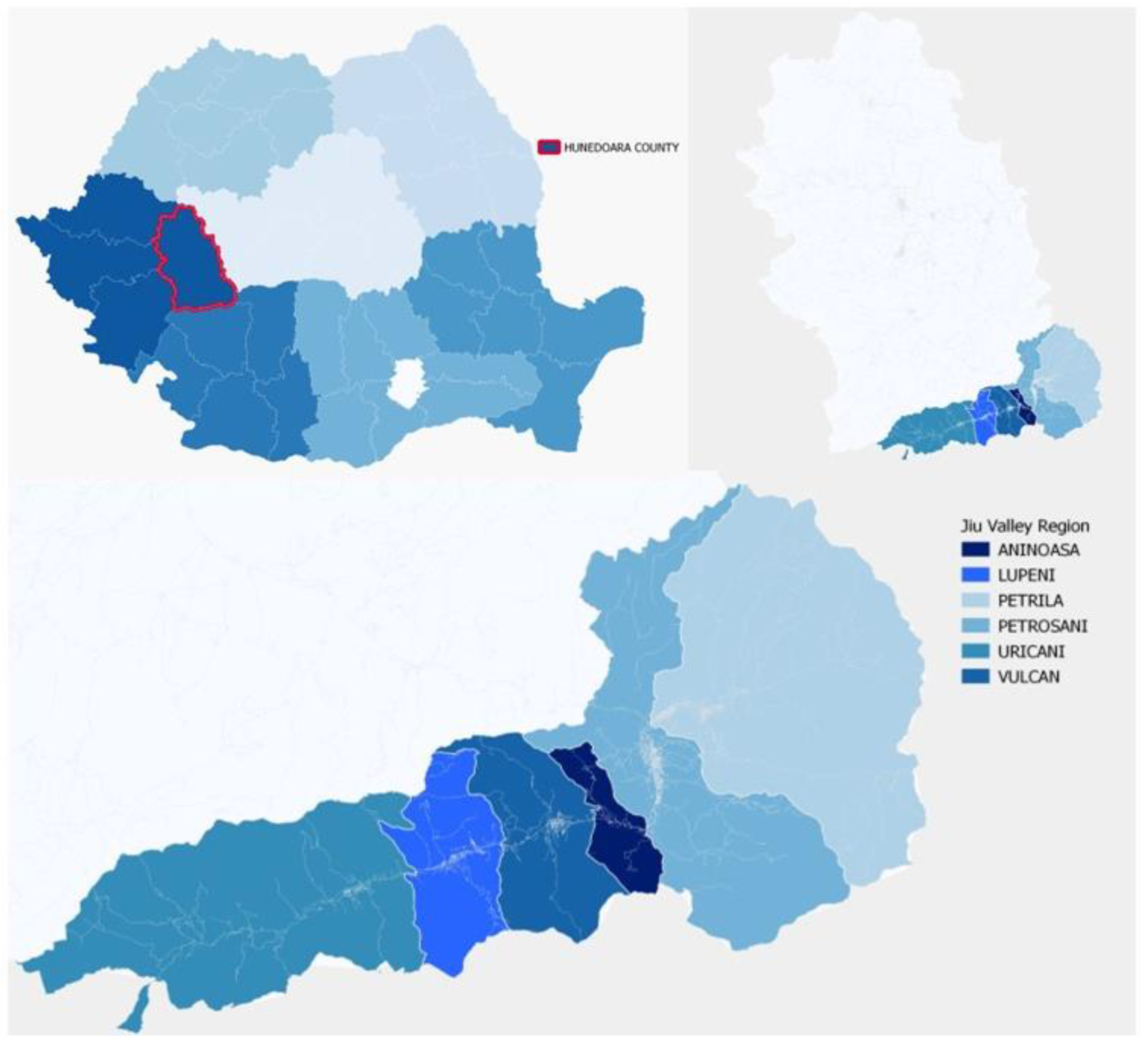

| City | Population | % of Jiu Valey Total |

|---|---|---|

| Petroșani | 40,319 | 31% |

| Vulcan | 27,274 | 21% |

| Lupeni | 25,375 | 19% |

| Petrila | 23,627 | 18% |

| Uricani | 9196 | 7% |

| Aninoasa | 4458 | 3% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Țoc, S.; Alexandrescu, F.M. Post-Coal Fantasies: An Actor-Network Theory-Inspired Critique of Post-Coal Development Strategies in the Jiu Valley, Romania. Land 2022, 11, 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11071022

Țoc S, Alexandrescu FM. Post-Coal Fantasies: An Actor-Network Theory-Inspired Critique of Post-Coal Development Strategies in the Jiu Valley, Romania. Land. 2022; 11(7):1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11071022

Chicago/Turabian StyleȚoc, Sebastian, and Filip Mihai Alexandrescu. 2022. "Post-Coal Fantasies: An Actor-Network Theory-Inspired Critique of Post-Coal Development Strategies in the Jiu Valley, Romania" Land 11, no. 7: 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11071022

APA StyleȚoc, S., & Alexandrescu, F. M. (2022). Post-Coal Fantasies: An Actor-Network Theory-Inspired Critique of Post-Coal Development Strategies in the Jiu Valley, Romania. Land, 11(7), 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11071022